The Aftermath: The Expiration of New START and What It Means For Us All

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

On February 5th, Axios reported that following overnight negotiations between the two sides, there remains a possibility for the two countries to continue observing the central limits after the Treaty’s expiry, although it did not state whether such an arrangement would include verification, and also noted that it had not been agreed to by either President.

If the two sides cannot reach an agreement, we face a world of heightened nuclear competition fueled by worst-case planning and nuclear expansion, fewer transparency mechanisms, and deepening mistrust among nations with the world’s most powerful weapons. Addressing these challenges in the new nuclear era will require creative and nontraditional approaches to risk reduction and arms control.

How did we get here?

Even if the two sides manage to negotiate a last-minute band-aid arrangement, the fact that we have no long-term arms control solution ready to take New START’s place is the culmination of years of breakdown in diplomacy and arms control efforts. New START entered into force on February 5th, 2011, with a 10-year duration and the option to extend it for five additional years. Leading up to the treaty’s original expiration date in 2021, there was serious concern that the United States and Russia would not come to an agreement on extension. For the first three years of his first administration, President Donald Trump engaged in few constructive arms control discussions with Russia. Then, in the final months of 2020, he proposed a short-term extension contingent on Russia agreeing to new verification measures and a warhead freeze, which Russia rejected. At the 11th hour, just two weeks after his inauguration, President Joe Biden agreed to a full five-year extension of the treaty with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The shaky status of New START further deteriorated in early 2023 when Putin announced that Russia was “suspending” its participation in the treaty, stipulating that resumption would require the United States to end its support for Ukraine, and that arms control talks would also have to involve France and the United Kingdom. As part of its suspension, Russia halted its exchanges of data, notifications, and telemetry information, and the United States subsequently followed suit with reciprocal countermeasures.

It is important to note that although the United States found Russia’s actions to constitute noncompliance with the treaty’s requirements, successive State Department reports following Russia’s suspension assessed that “Russia did not engage in any large-scale activity above the Treaty limits.” The 2024 compliance report, however, stated that “Russia was probably close to the deployed warhead limit during much of the year and may have exceeded the deployed warhead limit by a small number during portions of 2024.”

Ultimately, over years of growing tensions and mistrust between the two countries, the United States and Russia have barely managed to see New START through to its expiration, much less engage in talks for a new treaty to take its place. In September 2025, the Kremlin stated that “Russia is prepared to continue observing the treaty’s central quantitative restrictions for one year after February 5, 2026,” without verification. President Trump told a reporter that the proposal “sounds like a good idea to me,” but apparently did not respond to the proposal before the treaty’s deadline expired.

In addition to the worsening U.S.-Russia relationship, funding cuts at the U.S. Department of State, the Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation office at the NNSA, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence mean less investment in and capacity for executing a follow-on agreement, even if the political environment allowed for it.

What could this mean for nuclear forces?

New START placed limits on the number of strategic nuclear weapons that each country could possess and deploy: each side could deploy up to 1,550 warheads and 700 launchers, and could possess up to 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers. Incorporating a limit on non-deployed launchers was intended to prevent either country from “breaking out” or quickly expanding deployed numbers beyond the treaty limits.

Over the past 15 years, the treaty restraints and respective modernization plans resulted in significant force reductions in Russia and the United States. Both countries have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that neither will exceed the force levels currently dictated by New START. In the absence of an official agreement following New START’s expiration, however, both countries will likely default to mutual distrust and worst-case thinking about how their arsenals will grow in the future. This is a serious concern, considering both countries possess significant warhead upload capacity that would allow them to increase their deployed nuclear forces relatively quickly.

This kind of thinking has already been displayed by members of the House Armed Services Committee who, in 2023, called Biden’s agreement to extend New START “naive” and argued that Russia “cannot be trusted,” saying “if these agreements cannot be enforced, then they do nothing to enhance U.S. security, and serve only to undermine it.” Defense hawks in Congress and outside argued instead for upgrades and expansions to the U.S. nuclear force; the bipartisan Congressional Commission on the U.S. Strategic Posture in late-2023 recommended a broad range of options to expand the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The Biden administration also appeared to lay the groundwork for potential options to expand its deployed nuclear force following the end of New START: in June 2024, Pranay Vaddi, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Arms Control, Disarmament, and Nonproliferation at the National Security Council, stated that “Absent a change in the trajectory of adversary arsenals, we may reach a point in the coming years where an increase from current deployed numbers is required. And we need to be fully prepared to execute if the President makes that decision—if he makes that decision.” The Biden administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy published in 2024, however, did not direct an increase of U.S. deployed nuclear forces, effectively leaving that decision to the Trump administration.

If the United States decided to increase its deployed strategic forces, there are measures it could take to rapidly upload reserve warheads, while other options will take more time. For example, all 400 deployed U.S. ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, but about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that could be uploaded to carry three warheads each if necessary. An additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos could also be reloaded with missiles, though this process would likely take several years. With these potential additions in mind, the U.S. ICBM force could possibly double from 400 warheads to up to a maximum of 800 warheads. In any case, executing such an upload across the entirety of the ICBM force would require significant resources, manpower, and time—none of which the United States has in excess, given existing constraints on its already-delayed nuclear modernization program.

Increasing the warhead loading on U.S. ballistic missile submarines could be done faster than uploading the ICBM force. Each missile on the submarines currently carries an average of four or five warheads, a number that can be increased to eight. Doing so could theoretically add 800 to 900 warheads to the submarine force, but loading each missiles with the maximum number of warheads onto each missile (and by extension, each submarine) would dramatically limit the submarine force’s targeting flexibility, as war planners will not want to lock themselves into a situation in which submarine crews would be forced to fire the maximum number of warheads, rather than having a range of more limited options at their disposal. As a result, executing an upload across the submarine force could more realistically result in an increase of approximately 400 to 500 additional warheads. Doing so would take many months, given that each ballistic missile submarine would have to return to port on a rotating schedule in order to load the additional warheads. In addition, the United States has the option to reopen the four launch tubes on each ballistic missile submarine that had been converted to non-nuclear status for New START compliance, and the July 2025 “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” provided $62 million for conversion activities to take place after March 1st, 2026; however, doing so would need to overcome significant internal opposition and would likely take several months, if not years, to complete.

The quickest way for the United States to increase deployed nuclear warheads would be to load nuclear cruise missiles and bombs onto its long-range B-2 and B-52 bombers. The bombers were taken off alert and their nuclear weapons placed in storage in 1992, but hundreds of the weapons are stored at the bomber bases and could be loaded within days or weeks; additional weapons could be brought in from central storage depots. Up to 800 nuclear weapons are estimated to be available for the bombers. Yet loading live nuclear weapons onto bombers would significantly increase the vulnerability of the weapons to accidents and terrorist attacks.

Russia also has a significant warhead upload capacity, particularly for its ICBMs, but is subject to similar constraints as the United States. Several of Russia’s existing ICBMs are thought to have been downloaded to a smaller number of warheads than their maximum capacities in order to meet the New START force limits. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase by approximately 400 warheads.

Warheads on missiles onboard some of Russia’s SSBNs are also thought to have been reduced to a lower number to meet New START limits. Without treaty limitations, the number of deployed warheads could potentially be increased by 200-300 warheads, perhaps more in the future, although this number could be tempered by a desire for increased targeting flexibility, in a similar manner to the United States.

While also uncertain, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons, similarly to the United States.

Ultimately, if both countries chose to upload their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals could nearly double in size. While a maximum upload is highly unlikely, it is possible we will see immediate measures taken to upload certain systems, followed by gradual increases in other areas over the next few years. While defense hawks in Russia and the United States claim that more nuclear weapons are needed for national security, doing so would inevitably result in each country being targeted by hundreds of additional nuclear weapons.

Moreover, without the transparency and predictability that resulted from the verification regime and regular data exchanges stipulated under New START, nuclear uncertainty—and potentially confusion and misunderstandings—will increase. Russian and U.S. planners will rely more on worst-case scenarios in their nuclear programs, and both countries are likely to invest more in what they perceive will demonstrate resolve and increase their overall security, including nonstrategic nuclear forces, conventional forces, cyber and AI capabilities, and missile defense. These moves could also trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states, possibly leading to an increase in their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. China has already decided to increase its nuclear arsenal to better be able to counter what it perceives is a growing threat from other military powers; Beijing rejects numerical limits on its nuclear arsenal and increasing U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenal will make it harder to change its mind.

Re-imagining the future: The end of fully “compartmentalized” arms control?

The future of arms control is certainly not dead, but it is likely entering a new era. For decades, the United States and Russia pursued arms control negotiations in isolation from other security issues, emphasizing that the unique destructiveness of nuclear weapons requires that the topic be segregated. Although such negotiations were never completely disentangled from politics or other geopolitical events—as demonstrated, for example, by the refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify SALT II after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—this approach was largely successful as a framework for arms control during and immediately after the Cold War.

This fully compartmentalized approach, however, is likely no longer an option in a post-New START world. Russia has made it clear through both its actions—particularly its suspension of its treaty obligations primarily due to U.S. support for Ukraine—and its rhetoric that it will no longer engage in arms control negotiations absent a broader reboot of U.S.-Russia relations. And officials in the United States increasingly argue that bilateral nuclear limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals do not take into account the growing Chinese nuclear arsenal.

On February 3rd, Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov stated that in order to engage in strategic stability dialogue, “We need far-reaching shifts, changes for the better in the US approach to relations with us as a whole.” On numerous prior occasions, he had critiqued the United States’ approach to arms control: in 2023, he told TASS that Moscow cannot “discuss arms control issues in the mode of so-called compartmentalization, which means singling out from the whole range of issues some pressing ones which are of interest to the United States, and pushing to oblivion or taking off the table other points that are theoretically as important to Russia as those of interest to the Americans.”

It would appear that China thinks about arms control in a similar way. In 2024, China suspended strategic stability talks with the United States in response to U.S. arms sales to Taiwan and increased trade restrictions on China. A spokesperson from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized that in order to bring China to the table, the United States “must respect China’s core interests and create [the] necessary conditions for dialogue and exchange.” On February 5th, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian reiterated that “China’s nuclear strength is by no means at the same level with that of the U.S. or Russia. Thus, China will not take part in nuclear disarmament negotiations for the time-being.” Even if it were possible to change China’s opposition to numerical limits on nuclear forces and join the arms control process, it is not clear what the United States would actually be willing to limit or give up in return for Chinese concessions. One such possibility would be the more ambitious and fantastical elements of Golden Dome, as a multi-layered, space-based missile shield is fundamentally incompatible with the idea of accepted mutual vulnerability.

Re-imagining the future: verification without on-site inspections?

Traditional nuclear arms control, including New START, relies on the availability of on-site inspections to verify compliance. Absent a significant shift in geopolitical relations, however, it is implausible to imagine some combination of American, Russian, or Chinese inspectors roaming around each other’s territories anytime in the near future. As a result, the next generation of arms control agreements faces a clear challenge: how can countries verify that the other remains in compliance when the political reality prohibits on-site inspections?

Traditionally, countries have used “National Technical Means”—a term used to describe classified means of data collection, such as remote sensing and telemetry intelligence—to verify compliance with arms control agreements. NTMs are used as a complement to other sources of verification, including on-site inspections, data exchanges and notifications, and the exchange of telemetric information. Despite on-site inspections and formal data exchange being preferable, NTMs can be very capable; for example, the U.S. assessment that Russia might briefly have exceeded the New START warhead limit was based on NTMs, not on-site verification.

Given the political implausibility of on-site inspections forming part of a future verification regime, one of the authors has recently co-authored a report with Igor Morić from Princeton’s Science & Global Security Program on the possibility of a future arms control arrangement based around “Cooperative Technical Means.” Under such an arrangement, it could be possible for states to use national or commercial remote sensing tools to monitor each other’s nuclear capabilities, verify the numbers of fixed and mobile ICBM and SLBM launchers, as well as track the number and location of their heavy bombers. For a more detailed explanation, the full report can be accessed here.

What Now?

As Axios’ reporting indicates, everything could change in a day, for better or for worse. Countries could take unilateral measures to either exercise restraint or refuse cooperation. Specifically, it is important that each side refrain from significant increases in its nuclear arsenal regardless of whether a new arrangement is concluded; such steps will almost inevitably increase the competition dynamic that would result in an arms race.

It is also imperative that the United States and Russia commit to engaging in arms control as a means of reducing the risk of nuclear use, whether intentional or by accident or misinterpretation. The United States, in particular, should reinvest in and reprioritize diplomacy and nonproliferation to prepare for and signal an intention to re-engage in arms control dialogues.

While new technology and creative approaches offer potential solutions to issues plaguing past arms control arrangements, progress will still require political will and motivation from both sides.

Here at FAS, we will continue to track the nuclear force status and modernization programs across the nine nuclear-armed states, paying close attention to cost and schedule overruns that relentlessly plague many of these efforts. In an era where nuclear transparency and access to reliable, public information are declining, we believe our work is more critical now than ever before.

Additional work from us on this topic:

- After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

- If Arms Control Collapses, US and Russian Strategic Nuclear Arsenals Could Double In Size

- Inspections Without Inspectors: A Path Forward for Nuclear Arms Control Verification with “Cooperative Technical Means”

- The Long View: Strategic Arms Control After the New START Treaty

- 2025 Russia Nuclear Notebook

- 2025 United States Nuclear Notebook

- For all Nuclear Notebooks, see here

The Nuclear Information Project is currently supported with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

Federation of American Scientists Researchers Contribute Nuclear Weapons Expertise to International SIPRI Yearbook, Out Today

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) launches its annual assessment of the state of armaments, disarmament and international security

Washington, D.C. – June 16, 2025 – Nuclear weapons researchers at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) contributed to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s annual Yearbook, released today. Key findings of SIPRI Yearbook 2025 are that a dangerous new nuclear arms race is emerging at a time when arms control regimes are severely weakened.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “Instead, we see a clear trend of growing nuclear arsenals, sharpened nuclear rhetoric and the abandonment of arms control agreements.”

World’s nuclear arsenals being enlarged and upgraded

Nearly all of the nine nuclear-armed states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and Israel—continued intensive nuclear modernization programmes in 2024, upgrading existing weapons and adding newer versions.

Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,241 warheads in January 2025, about 9614 were in military stockpiles for potential use (see the table below). An estimated 3912 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft and the rest were in central storage. Around 2100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the USA, but China may now keep some warheads on missiles during peacetime.

Since the end of the cold war, the gradual dismantlement of retired warheads by Russia and the USA has normally outstripped the deployment of new warheads, resulting in an overall year-on year decrease in the global inventory of nuclear weapons. This trend is likely to be reversed in the coming years, as the pace of dismantlement is slowing, while the deployment of new nuclear weapons is accelerating.

Russia and the USA together possess around 90 per cent of all nuclear weapons. The sizes of their respective military stockpiles (i.e. useable warheads) seem to have stayed relatively stable in 2024 but both states are implementing extensive modernization programmes that could increase the size and diversity of their arsenals in the future. If no new agreement is reached to cap their stockpiles, the number of warheads they deploy on strategic missiles seems likely to increase after the bilateral 2010 Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START) expires in February 2026.

The USA’s comprehensive nuclear modernization programme is progressing but in 2024 faced planning and funding challenges that could delay and significantly increase the cost of the new strategic arsenal. Moreover, the addition of new non-strategic nuclear weapons to the US arsenal will place further stress on the modernization programme.

Russia’s nuclear modernization programme is also facing challenges that in 2024 included a test failure and the further delay of the new Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and slower than expected upgrades of other systems. Furthermore, an increase in Russia’s non-strategic nuclear warheads predicted by the USA in 2020 has so far not materialized.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons 2025 Federation of American Scientists Unveils Comprehensive Analysis of Russia’s Nuclear Arsenal

Washington, D.C. – May 6, 2025 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) today released “Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons 2025,” its authoritative annual survey of Russia’s nuclear weapons arsenal. The FAS Nuclear Notebook is considered the most reliable public source for information on global nuclear arsenals for all nine nuclear-armed states. FAS has played a critical role for almost 80 years to increase transparency and accountability over the world’s nuclear arsenals and to support policies that reduce the numbers and risks of their use.

This year’s report, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and by Taylor & Francis and available in full here, discusses the following takeaways:

- Russia currently maintains nearly 5,460 nuclear warheads, with an estimated 1,718 deployed. This represents a slight decrease in total warheads from previous years but still positions Russia as the world’s largest nuclear power alongside the United States.

- Russia continues to modernize its nuclear triad, replacing Soviet-era weapons with newer types, but modernization of ICBMs and strategic bombers has been slow. The country’s efforts to develop the advanced Sarmat (RS-28 or SS-29) ICBM and the next-generation strategic bomber, PAK DA, have faced delays and setbacks.

- The submarine-based nuclear force continues its modernization with Borei-class submarines replacing older types. A portion of Russian ballistic missile submarines are at sea at any given time on strategic deterrent patrols. Significant nuclear warhead and missile storage upgrades are underway at the Pacific and Northern fleet bases.

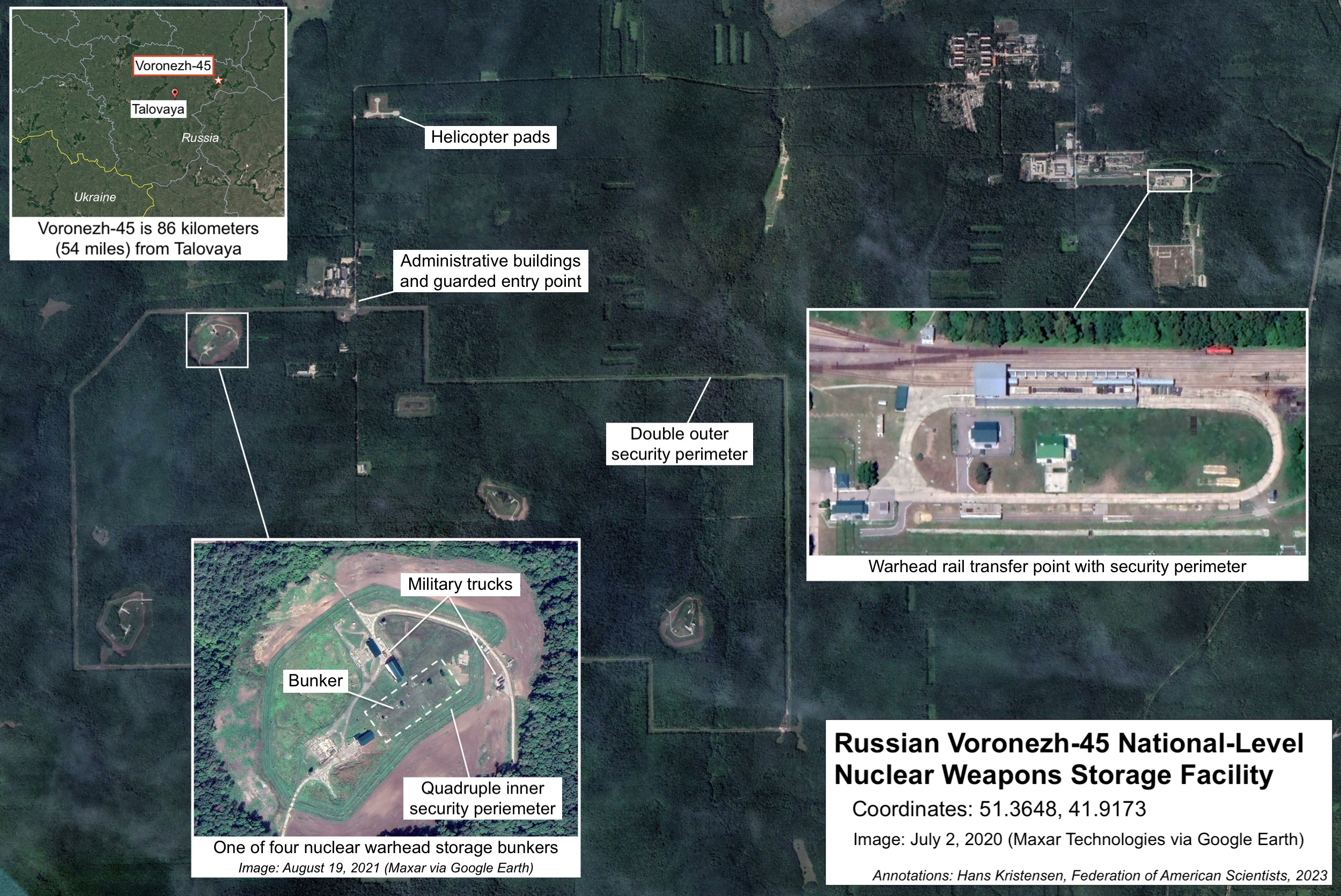

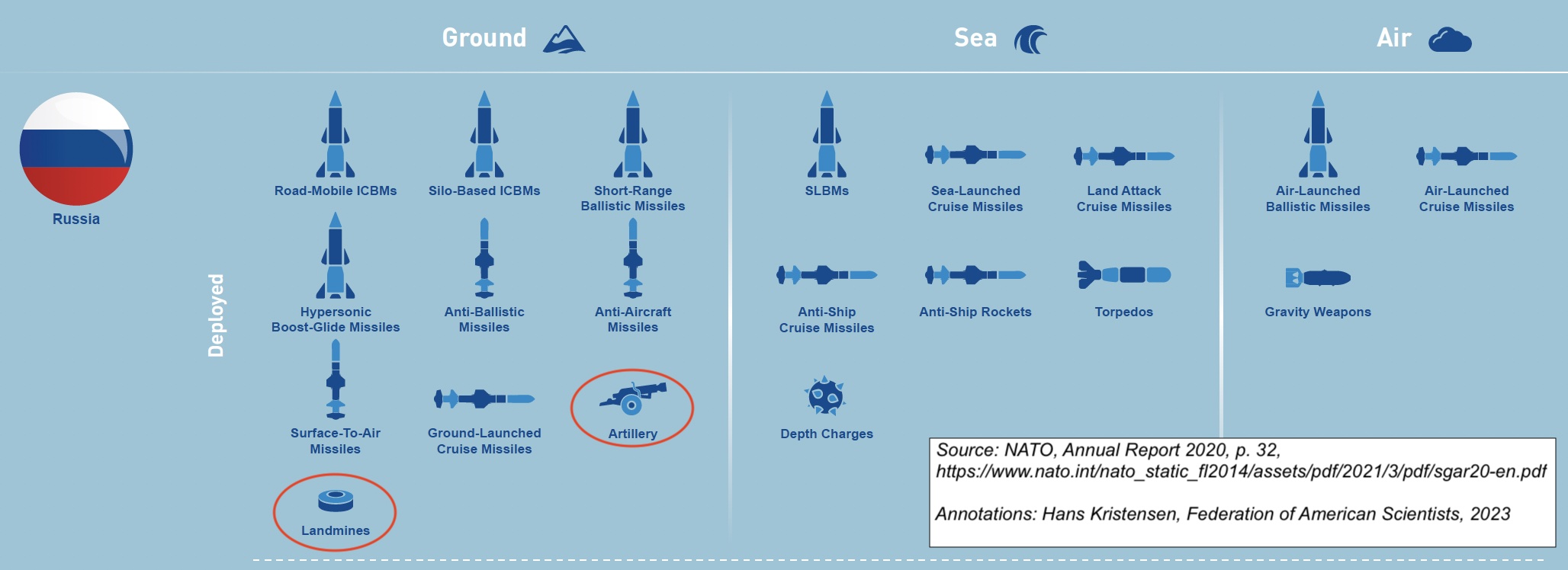

- Russia continues modernizing and emphasizing its nonstrategic nuclear forces. This includes land- and sea-based dual-capable missiles and tactical aircraft. Despite modernization of launchers, the number of warheads assigned to those launchers has remained relatively stable. Russia held several high-profile exercises with its nonstrategic forces in 2024, and the authors describe upgrades to a suspected nuclear storage depot in Belarus.

- Russia has maintained its policy of nuclear deterrence, emphasizing the strategic importance of its nuclear arsenal in its military doctrine. Updates to public policy documents describe a broader range of scenarios for potential use of nuclear weapons but it is unknown to what extent this is reflected in changes to military plans.

FAS Nuclear Experts and Previous Issues of Nuclear Notebook

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The first Nuclear Notebook was published in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the first U.S. nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenal and their role.

This latest issue on Russia’s nuclear weapons comes after the release of Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Weapons 2025 and will be followed in June by Nuclear Notebook: French Nuclear Weapons 2025. More research available at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

The Federation of American Scientists’ work on nuclear transparency would not be possible without generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Depot In Belarus Shows New Upgrades Possibly For Russian Nuclear Warhead Storage

A military depot in central Belarus has recently been upgraded with additional security perimeters and an access point that indicate it could be intended for housing Russian nuclear warheads for Belarus’ Russia-supplied Iskander missile launchers.

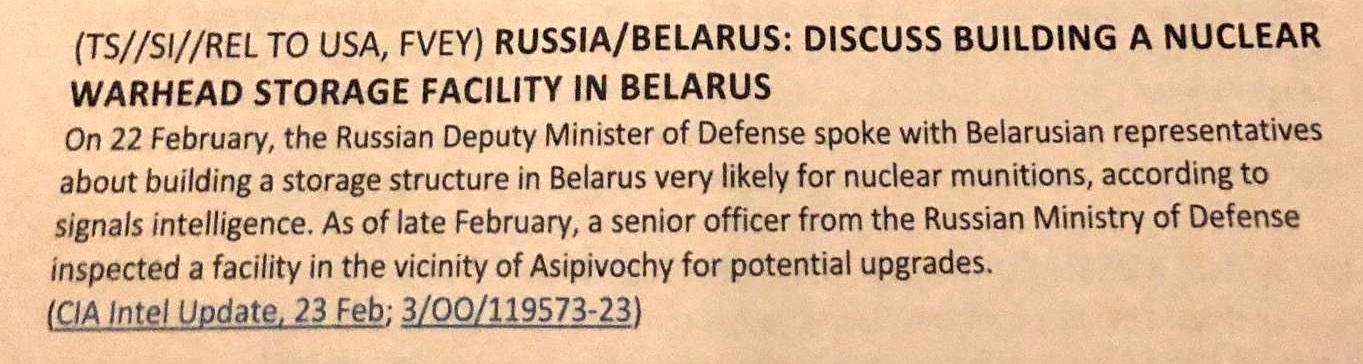

The upgraded enclosure is located inside an existing military depot east of the town of Ashipovichy. Leaked documents on Discord indicated that in February 2023, the CIA reported that “a senior officer from the Russian Ministry of Defense inspected a facility in the vicinity of Asipivochy [sic] for potential upgrades” to serve as “a nuclear warhead storage facility in Belarus” (see excerpt of CIA leaked report below).

This part of a leaked CIA document reported Russian inspection of Asipovichy for potential nuclear warhead storage.

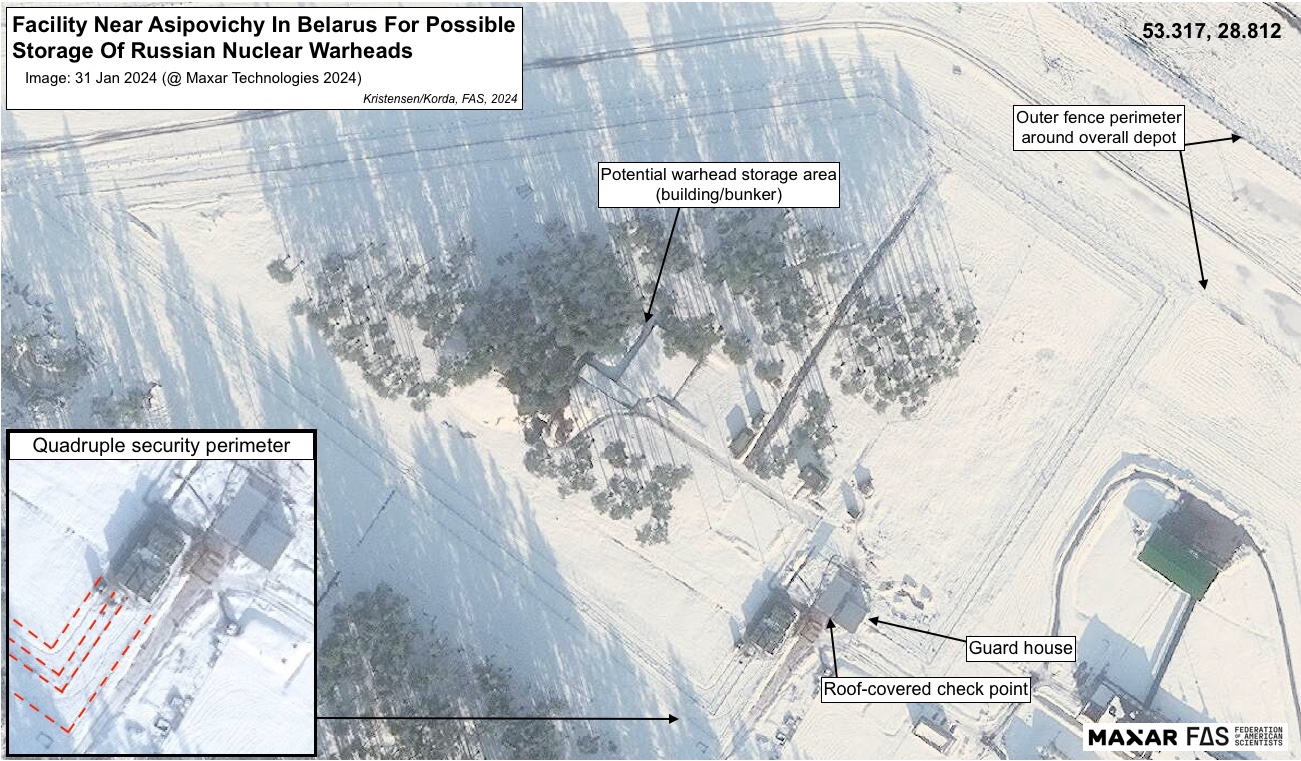

A satellite image provided by Maxar Technologies shows that part of the depot near Asipovichy has since been upgraded with a quadruple-fence security perimeter and a roof-covered guarded access point (see image below).

Upgrades to Asipovichy depot now shows quadruple security perimeter.

Satellite images show that construction began at the facility around the time of the reported visit by the senior Russian official. The upgrades have progressed slowly, with the initial construction of a double-layer security perimeter. That would be insufficient for storage of nuclear warheads. In October 2023 construction of a new perimeter began inside the existing security perimeter, and the Maxar image from late-January 2024 shows what appears to be a total of four security perimeters. The construction of the added perimeters shows significant digging for what could potentially be cables and various sensors. Trees within the new inner perimeter have also been cleared by approximately 20 meters away from the fencing.

If so, these upgrades would more closely resemble the level of physical protection that Russian authorities would require for storage of nuclear weapons.

Russian and Belarusian statements over the past two years have repeatedly claimed that nuclear weapons had been brought to Belarus, but we had previously not seen clear evidence that facilities had been readied for that purpose.

Earlier today, under the headline “Russian Nuclear Weapons Are Now In Belarus,” Foreign Policy reported that “Western officials,” including the Lithuanian defense minister, “confirmed the news of the deployment.” The article says that “a senior Lithuanian diplomat and other Western officials indicated to Foreign Policy that Russia had built specific storage facilities and railway systems in Belarus to potentially house a nuclear arsenal.”

It remains unclear if the confirmations referred to nuclear-capable launchers or the actual warheads for those launchers. But the upgrade at the Asipovichy depot shows security features that potentially could match upgrades required for nuclear warhead storage at the same facility that the Russian defense official apparently inspected one year ago.

If nuclear warheads have indeed been moved to Belarus, it does not give Russia a significant military advantage in eastern Europe. Russia already maintains modernized nuclear storage facilities in Kaliningrad and has long had the ability to target NATO countries with nuclear weapons. Instead, the deployment appears designed to unnerve NATO’s eastern-most member states and highlight Russia’s status as a nuclear power.

Additional background information:

• Nuclear Weapons Sharing, 2023

• Belarus “Nuclear-Capable” Iskanders Get A New Garage

• Russian Nuclear Weapons Deployment Plans In Belarus: Is There Visual Confirmation?

• Russian Nuclear Weapons In Belarus? A CNS Roundtable Discussion

• Video Indicates That Lida Air Base Might Get Russian “Nuclear Sharing” Mission In Belarus

• Geo-Location of Russian-Supplied Iskander Launchers Training at Osipovichi i Belarus

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Details of Russia’s nuclear modernization are inconsistent with warnings of vast nuclear expansion

While many are rightly concerned about Russia’s development and fielding of new nuclear-capable systems, a few key points about Russia’s nuclear modernization provide critical context into Moscow’s threat perceptions and strategic priorities and suggest that fears of a substantial Russian nuclear increase or change in the strategic environment might be overblown.

First, Russia’s nuclear force modernization is driven mainly by the need to replace older Soviet-era systems that are aging out. Just like every nuclear-armed state, the goal of Russia’s modernization campaign is to ensure that its forces are ready to operate in today’s environment and to support existing deterrence and strategic requirements. The initiation of these modernization programs does not necessarily depend on the adoption of a new nuclear strategy and posture but simply on when the systems were first fielded decades ago. The percentage of newer Russian nuclear systems compared to Soviet-era systems has long been an important public metric for Putin, who announced last month that 95% of Russian strategic systems had been modernized.

Second, Russia sees U.S. missile defense capabilities as a real future risk. Because of this, we see Russia developing certain capabilities that are specifically designed to challenge U.S. missile defenses. For instance, Russia reportedly plans to replace its silo-based Topol-M intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) by 2030 with a new “Yars-M” ICBM variant that is under development. Compared to the single-warhead Topol-M ICBM, the Yars-M system will apparently carry multiple warheads with individual propulsion systems in a parallel staging configuration, which would theoretically allow for greater survivability against missile defenses given that warhead separation would take place at an earlier stage in flight. It would also potentially allow Russia to field more warheads compared with the Topol-M system.

Additionally, we also see Russia developing hypersonic missiles that are designed to evade U.S. missile defense systems. Russia deployed upgraded SS-19 Mod 4s with its new Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) and is also rumored to be developing new HGVs that can be fitted atop modified ICBMs. Russia is also developing a new Kh-95 hypersonic air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) and has frequently touted the “hypersonic” nature of the Kinzhal long-range, air-launched ballistic missile that can be launched from specially modified MiG-31Ks. These developments, however, are not a strategic game-changer. A ‘hypersonic’ weapon broadly means anything that travels above Mach 5, which already includes existing ICBMs. While hypersonic cruise missiles and hypersonic glide vehicles are more difficult to intercept, the United States is already developing new missile defense interceptors specifically designed to counter these capabilities, and Russia’s war in Ukraine has also proven that ‘hypersonic’ missiles such as the Kinzhal are capable of being shot down in a real-world scenario.

Notably, many of Russia’s modernization programs have also been facing serious setbacks. From the Sarmat ICBM to the Burevestnik intercontinental-range nuclear-powered, ground-launched, nuclear-armed cruise missile to the Poseidon nuclear-powered, long-range, nuclear-armed torpedo to the modernized Tu-160M bombers, many different systems are undergoing modernization programs simultaneously. On top of additional sanctions, supply chain deficiencies, and technical challenges, the concurrent development and modernization of several systems is causing significant delays to planned deployment schedules.

Russia’s modernization plans seem focused on maintaining parity with the United States and cultivating prestige, especially in the midst of its lack of success in Ukraine. Indeed, some of Russia’s new nuclear systems under development appear to mirror new U.S. systems, but their development is lagging in comparison. For example, while the United States’ new strategic bomber under development–the B-21 Raider–has completed two confirmed test flights and entered low-rate initial production, Russia’s PAK DA bomber, also taking on a flying wing design, has been marred by delays. A full prototype has yet to be completed, despite research and development starting several years before the Raider.

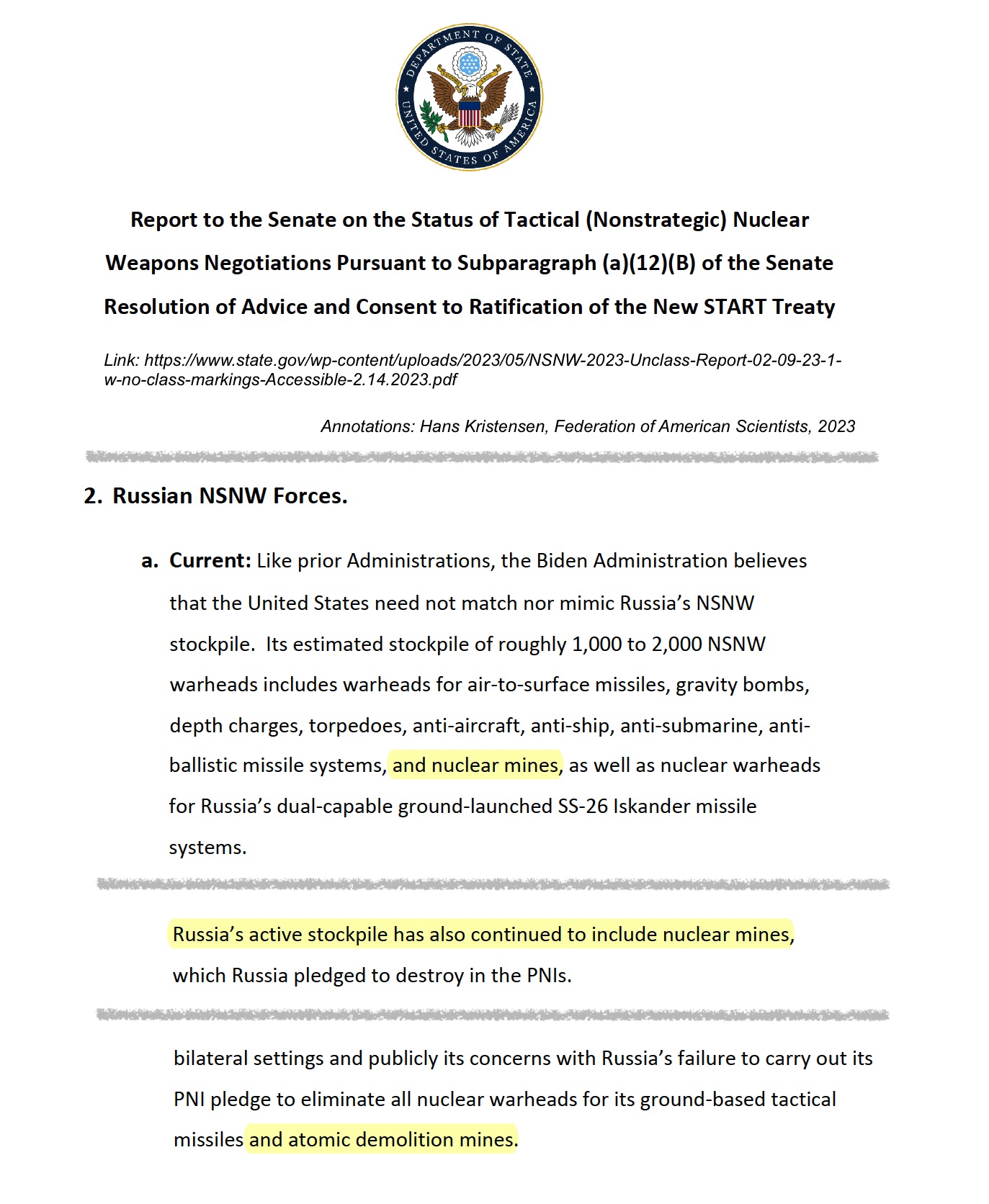

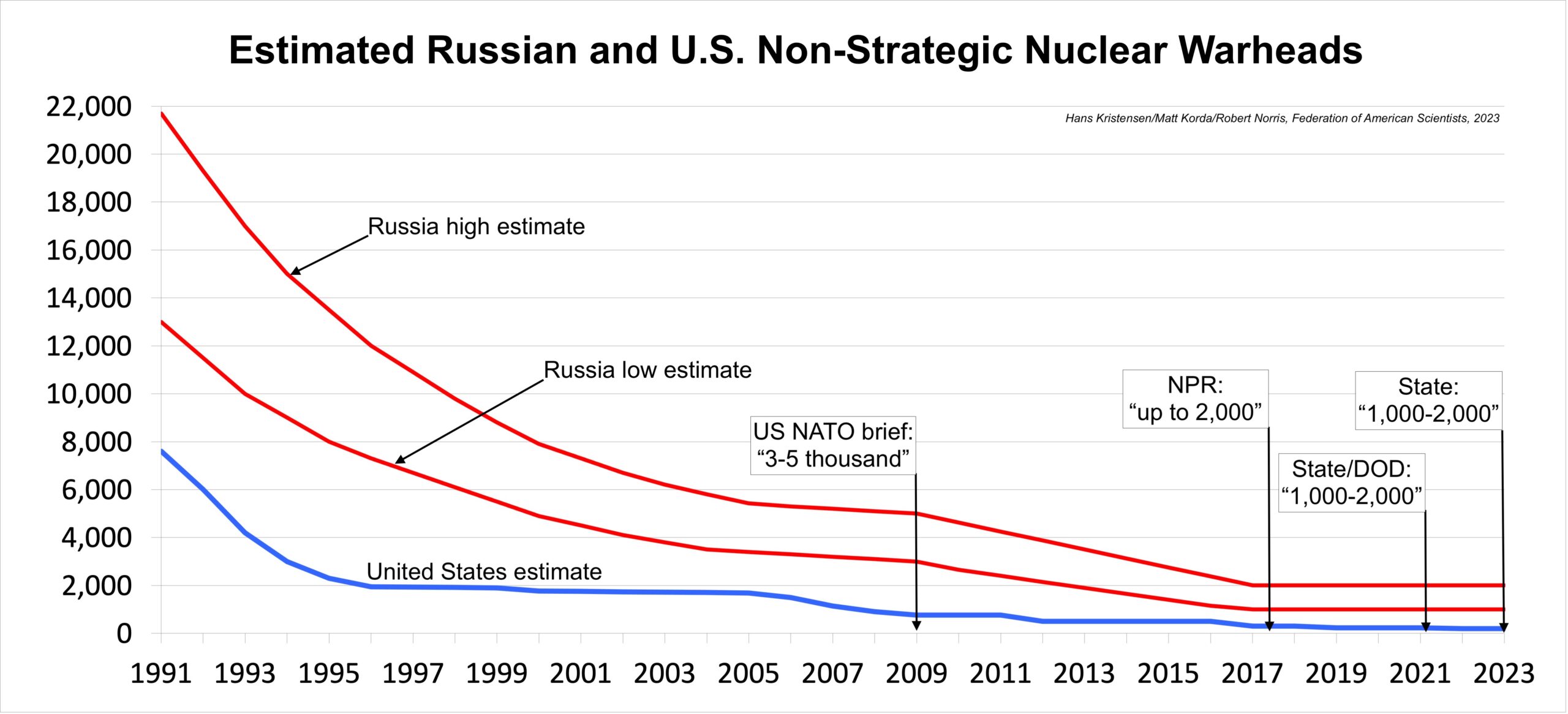

The threat from Russia’s tactical nuclear arsenal also appears to have been overblown. The U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency’s 2021 Worldwide Threat Assessment and the State Department’s 2023 New START implementation report stated that Russia likely possesses 1,000-2,000 tactical nuclear warheads, though the State Department estimate included retired warheads awaiting dismantlement. In 2022, some officials warned that Russia’s tactical nuclear arsenal could double by 2030. Despite these warnings, our team has observed no evidence of such an increase and have instead lowered our estimate to approximately 1,558 nonstrategic nuclear warheads. There is little authoritative public information available to support the rumors of a massive Russian increase of tactical nuclear weapons.

Despite all these developments, Russia’s current and planned force structure does not fundamentally ‘rock the boat.’ Russia’s nuclear modernization won’t change the fact that Russia still has fewer strategic launchers than the United States. Russia may be modernizing and developing new nuclear-capable systems, but it is not significantly building up its nuclear forces: Russia is replacing Soviet-era missiles with newer types on a less-than-one-for-one basis, we do not observe an increase in the number of warheads assigned for delivery by tactical forces, and we don’t see any changes in force posture on the ground. Russia’s claimed deployment of tactical nuclear weapons to Belarus is likely meant to primarily discourage the United States and NATO from further intervention in the war in Ukraine. Because of the existing presence of Russian dual-capable forces and nuclear weapons storage in the Kaliningrad region, the presence of tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus does not change the strategic environment and likely reflects a contingency plan rather than a permanent deployment.

Despite Putin’s nuclear threats during the war in Ukraine, and despite alarmist reports to the contrary, there has been no significant change in Russia’s nuclear strategy, which has largely remained relatively consistent for decades. Russia has frequently used nuclear threats in the past to try to affect geopolitics, including in regard to NATO expansion, western aid to Ukraine, and the deployment of U.S. missile defenses in Europe in 2008; however, there is no public indication that these signals necessarily portend a lowering of Russia’s nuclear threshold.

None of this is to say that Russian nuclear modernization and development is not a problem or cause for concern; Russia’s modernization of its nuclear forces, in addition to threats of nuclear action against other nations, creates ambiguity and concern surrounding Russia’s long-term intentions. Overinflation of the threat, however, will lead to miscalculation, calls for unnecessary increases to the U.S. nuclear force structure, and resistance to much-needed arms control efforts. We must be wary of letting worst-case scenario thinking push us into a dangerous arms race and unstable security situation, particularly when global tensions are so high and the United States is already planning to spend over $1 trillion on nuclear weapons programs over the next 30 years.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Nuclear Notebook: Russian nuclear forces, 2024

The Federation of American Scientists has released its annual estimate of the size and makeup of Russia’s nuclear forces. The total number of nuclear warheads are now estimated to include 4,380 stockpiled warheads for operational forces, as well as an additional 1,200 retired warheads awaiting dismantlement, for a total inventory of 5,580 warheads.

Despite modernization of Russian nuclear forces and warnings about an increase of especially shorter-range non-strategic warheads, we do not yet see such an increase as far as open sources indicate. For now, the number of non-strategic warheads appears to be relatively stable with slight fluctuations. Although our new estimate of this category is lower than last year, that is not because of an actual decrease in the force level but because we have finetuned assumptions about the number of warheads assigned to Russian non-strategic nuclear forces. Our new estimate of roughly 1,558 non-strategic warheads is well within the range of 1,000-2,000 warheads estimated by the U.S. Intelligence Community for the past several years.

While Russia’s nuclear statements and threatening rhetoric are of great concern, Russia’s nuclear arsenal and operations have changed little since our 2023 estimates beyond the ongoing modernization. In the future, however, the number of warheads assigned to Russian strategic forces may increase as single-warhead missiles are replaced with missiles equipped with multiple warheads. If the New START treaty is not replaced with a new agreement, both Russia and the United States could potentially increase the number of deployed warheads.

Also in the Nuclear Notebook: Russian nuclear forces, 2024, is our latest analysis on Russian force modernization and strategy:

- Russian nuclear force modernization, intended to replace Soviet-era missiles, aircrafts, and submarines with new systems, continues at a steady pace.

- Modernization of road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missiles is essentially complete with focus shifting to modernizing silo-based missiles.

- New strategic and non-strategic submarines continue to replace Soviet-era models but with enhanced nuclear weapon systems.

- Upgrades and some reproduction of Soviet-era strategic bombers continue with new long-range cruise missiles.

- News leaks seem to indicate that Russia might be developing a nuclear-armed anti-satellite weapon which, if deployed in the future, would violate the Outer Space Treaty.

- Upgrades of nuclear weapons storage facilities are underway at several bases to accommodate the weapons for modernized forces.

- Because Russian conventional forces have been significantly depleted and their effectiveness questioned by the war in Ukraine, nuclear forces will likely be seen as important to compensate for that weakness.

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, is widely considered the most accurate public source for information on global nuclear arsenals for all nine nuclear-armed states.

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

For Heaven’s Sake: Why Would Russia Want to Nuke Space?

It can be more than a little scary to look into the mind of a dangerous dictator like Vladimir Putin. But as Russia has several thousand nuclear weapons, managing stability and avoiding nuclear war requires that America try to understand what is happening with both the mind of the country’s leader and capabilities of its military. Deterrence is about understanding how our actions influence that of others, and vice versa. Thus, it remains essential to consider what Russia (and other adversaries) is pursuing in terms of possible contingencies, and interpret changes in military and strategic capabilities.

So when news broke in February that Russia was reportedly building some nuclear connected anti-satellite weapon, a lot of people started scratching their heads. First, because of the manner in which the news was leaked. Congressman Mike Turner seemed to get ahead of both the process and the intelligence itself, and created a bit of a panic by demanding full and immediate declassification of all information about the system. It now seems this was alarmist, and perhaps motivated by other political factors. Leaks seemed to indicate that Russia might be planning to launch a nuclear-powered anti-satellite directed energy weapon into space. U.S. officials are reportedly telling allies Russia could launch the system into space within the next year. Details became a little clearer, thanks to a public briefing by White House Advisor Adm. John Kirby. Kirby confirmed that the planned system was still in development, and President Biden later said it was not clear if and when the system would be deployed. Importantly, Kirby also stated that the system, if deployed, would violate the Outer Space Treaty of 1967. That phrase made clear that the Russian program involved placing a nuclear weapon in outer space, since deploying nuclear weapons in space is the main and only specific constraint contained in the OST.

What Can Putin Be Thinking?

We can speculate that the Russian program would involve deploying a nuclear device in orbit, presumably with some maneuvering capability so that it can be detonated to disable satellites. A nuclear explosion in space would create a series of devastating effects, including an electromagnetic pulse, and longer-lasting radiation that would circle the earth and dramatically compromise satellite communications world-wide. Some hardened assets might survive, but other unshielded military and almost all non-shielded commercial satellites would be potentially vulnerable. The global economic and communications system could be shut down or destroyed for years, and some orbits made hazardous – if not unusable – for an extended period due to space debris.

Who would do such a thing? Well, the Soviet Union and the United States considered a lot of dangerous nuclear ideas during the Cold War, including detonating nuclear weapons in outer space to blind an adversary’s space assets. The U.S. had a program in the 1960s called Casaba Howitzer, which would use nuclear explosions to drive energy beams to attack space assets. Both states tested nuclear weapons at high altitudes and considered using nuclear weapons in space. So the idea is not new. It was just rejected as reckless and dangerous for a variety of good reasons. Making space unusable is one. Leaving nuclear weapons in orbit – unprotected and out of positive human control and potentially liable to uncontrolled reentry – are two more.

So why would Russia return to this really dangerous idea now? There are at least three explanations that have some credibility (and possibly more as some of my colleagues have pointed out).

Explanation 1: Go After American Power Asymmetrically

The first plausible explanation is that in the 2000s, as Russia’s conventional military was weak and being rehabilitated, Vladimir Putin threw a lot of money at the Russia nuclear complex to come up with programs that could undermine America’s advantages. This funding led to a number of very unorthodox nuclear programs including the now famous Poseidon long-range, underwater nuclear-armed torpedo and the Skyfall, a nuclear-powered, nuclear-tipped cruise missile that can fly for days and attack its targets from unexpected angles. Both of these programs were conceived of decades ago, but did not get fully funded or deployed during the Cold War. When the USSR collapsed, these programs all withered. Both novel systems have found new support under Putin, who has touted them in multiple speeches.

The as-yet unnamed nuclear-armed satellite killer (How about Starburst for a name?) could be another such device, brought back to life from the Soviet archives to go after American power asymmetrically. As America relies heavily on space for military operations, countering it could make it easier for Russia to go toe to toe with the west in a conflict. It could be that this program was mothballed when the USSR collapsed but rehabilitated when new money was available, and details were only available recently in the later stages of development. Thus, it should not be assumed that there is a clear use strategy or specific scenario in mind behind the weapon. Both Moscow and Washington (and now some speculate China as well with its own nuclear expansion) have long histories of pursuing nuclear programs because they could, and then figuring out how to use them later.

Explanation 2: Nuclear “Insurance Policies”

A second motive is less benign than just technical and financial opportunity, and would involve Russia explicitly seeking programs and capabilities that could go after American nuclear control capabilities in a crisis to prevent America from attacking Russia first. This could be considered consistent with Russia’s stated but dangerously provocative “escalate to de-escalate strategy.” Russia’s fear is also likely behind the Poseidon and Skyfall, since both of these systems are more fittingly thought of as retaliatory, and not first strike weapons. Neither move fast enough to disarm the U.S. and are mainly good for firing after an attack. Thus, many in Russia likely consider them nuclear insurance policies; if Washington ever decided to pursue a disarming first strike made up of American conventional and nuclear assets, and backed by U.S. missile defenses (known in Russia as the splendid strike threat) enough Russian nuclear weapons would survive to destroy America, keeping deterrence intact. It is hard, and actually morally offensive, to have sympathy for Vladimir Putin, but there is a long history of fear as a motive and a sense of encirclement that permeates his regime. Thus, many of these nuclear programs – including the new nuclear armed space system – could be seen in this light. If this is an explanation for other novel nuclear systems, then it could also be part of the motive for the new space/nuclear option.

Explanation 3: Put America’s Technical Advantages at Risk

The third motive is one that probably resonates with most observers of Putin’s long and brutal time in office, marked by political assassinations and repression at home and multiple wars abroad. This possible motive is one where Putin is investing in capabilities that could cripple America in a run up to a direct conflict with Moscow. Being able to detonate a nuclear weapon in space and damage, if not destroy America’s extensive constellations of military satellites could be seen by Russia as both useful and even necessary to prepare for a possible conflict with the west and America. Its threatened use could be used to try and force America to back down in a crisis, or even used preemptively as a prelude to a major military move by Putin against NATO or America itself. As a weapon of aggression, a space-based device could put America’s considerable technical advantages at risk, thus explaining why some have expressed concern about America’s urgent need to upgrade its command and control systems and improve its resilience in space launch and satellite systems. Interestingly, in the move and counter-move process of deterrence and warfare, America’s investment in smaller, resilient constellations of satellites may have increased Russia’s interest in systems that can disable large numbers of assets as opposed to direct assent, kinetic anti-satellite weapons.

So why is Russia pursuing such a program? The bottom line is we don’t really know. Despite spending $50 billion a year on nuclear weapons, $900 billion on defense broadly, and $70 billion on intelligence, we don’t have as much insight into Russia’s nuclear doctrine or Putin’s inner thinking as we might want. All three of the motives laid out above are plausible; it’s also possible that a combination of the three are driving the Russian leader. We may never know.

Still, an important question remains regarding what the U.S. should do in response. Legally and morally, the U.S. and its allies should call out any such illegal and dangerous effort for what it is – madness. Detonating a nuclear weapon in space would not only damage U.S. assets but those of all countries, including Russia (China, India etc). It would set back the use of space for multiple purposes – peaceful and otherwise – by decades.

The Russia space program puts even greater emphasis on the need for America to insulate its space assets, diversify its systems to deal with space attacks, and develop more resilient space capabilities including through rapid relaunch abilities. In a conflict, demonstrating that the U.S. can quickly launch and replace critical space-based assets may be one way to deter Russia from ever using such a crazy and dangerous device. If doing so provides no material advantage, the need or urge to use it goes way down. Such resiliency requires considerable investment and U.S. leaders should also be mindful of an overreliance on private space launch capabilities, which while important cannot replace the Government’s own ability to protect American assets.

However this resiliency is developed – it will be expensive. But consider the money the U.S. is investing in redundant and arguably unnecessary nuclear overkill – including the new nuclear land based intercontinental ballistic missile that has now ballooned from an estimated $62B in 2015 to over $130 billion, a number which may still be climbing. Perhaps redirecting some of that nuclear funding to more urgent and useful priorities would be a better investment.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Upgrades to Russia’s Nuclear-Capable Submarine Fleet

[With updated graphic] Russia is in the midst of a decades-long nuclear force modernization program intended to replace Soviet-era missiles, aircraft, and submarines with new systems. As part of this project, Russia’s Navy is currently modernizing its nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) fleet and building new nuclear-powered guided missile submarines (SSGNs), along with other non-strategic nuclear-capable naval systems. The final delivery of these new strategic and non-strategic submarines to the Northern and Pacific fleets is expected to be complete by the early 2030s. FAS has tracked the progress of these developments as well as the upgrades to the supporting naval infrastructure, including submarine piers, missile loading piers, and new nuclear warhead storage facilities.

Putin commissions new nuclear-capable submarines

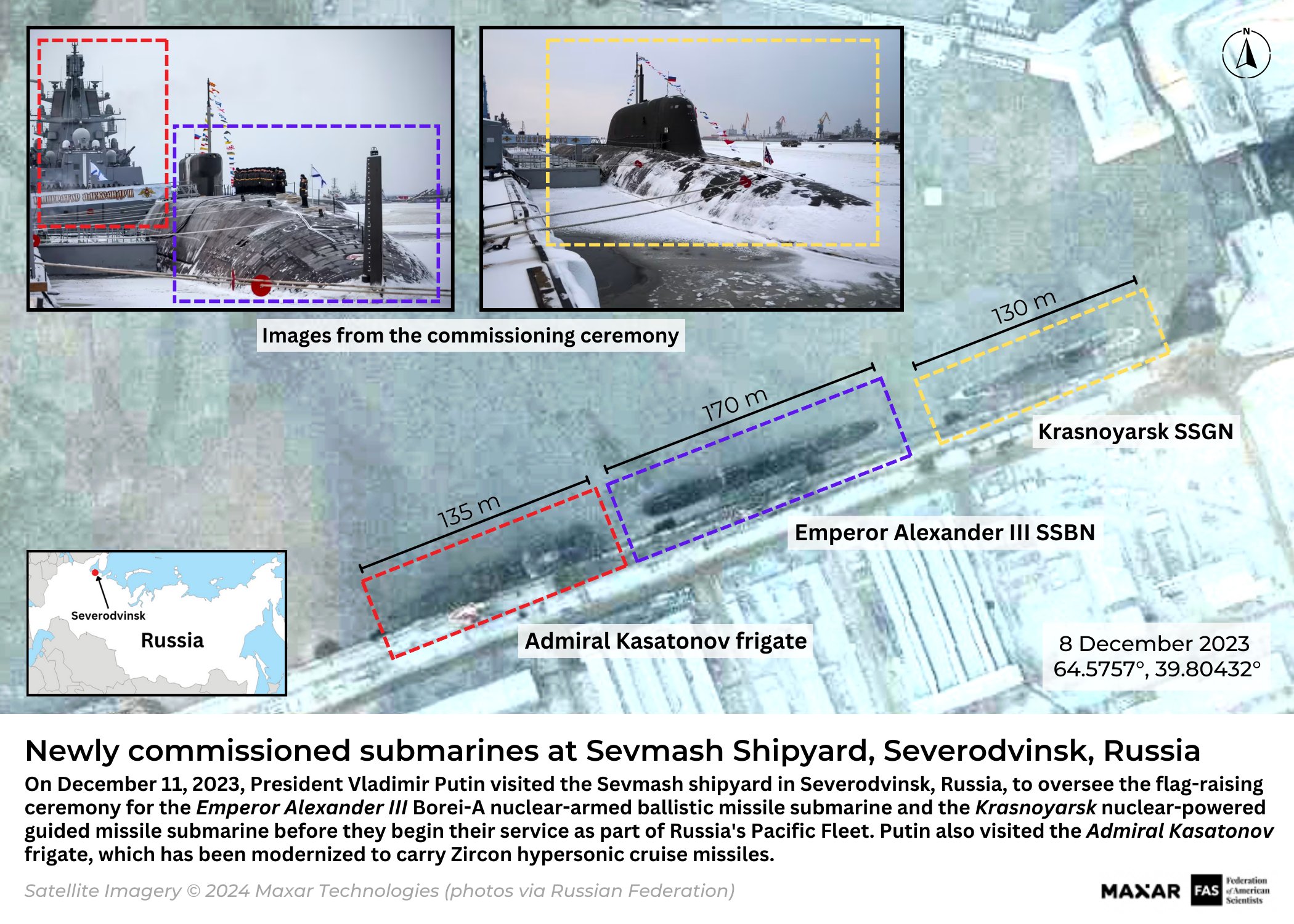

On 11 December 2023, Russian President Vladimir Putin traveled to the Sevmash shipyard in Severodvinsk to attend the flag-raising ceremony for two new nuclear-capable submarines. Putin’s trip to Severodvinsk came days after he declared his intention to seek another six-year presidential term.

At the shipyard, Putin oversaw the raising of the Russian Navy’s flag on the newly completed Borei-A Emperor Alexander III (K-554) SSBN and the Yasen-M Krasnoyarsk (K-571) SSGN. Putin also visited the Admiral Kasatonov frigate of Russia’s Northern Fleet, which was recently modernized to carry four Zircon hypersonic cruise missiles. A Maxar Technologies satellite captured preparations for the ceremony at Sevmash three days before Putin’s arrival.

On December 11, 2023, President Vladimir Putin visited the Sevmash shipyard in Severodvinsk, Russia, to oversee the flag-raising ceremony for the Emperor Alexander III Borei-A nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarine and the Krasnoyarsk nuclear-powered guided missile submarine before they begin their service as part of Russia’s Pacific Fleet. Putin also visited the Admiral Kasatonov frigate, which has been modernized to carry Zircon hypersonic cruise missiles.

Unlike many other nuclear–armed states, it is not unusual for Putin to oversee ceremonies or drills relating to Russia’s nuclear forces. He regularly attends flag-raising ceremonies of other nuclear-powered submarines and nuclear force exercises as a signal of strength and confidence in Russian nuclear capabilities. In fact, Kremlin Spokesman Dmitry Peskov stated before a February 2022 strategic deterrence force drill that “such drills and training launches, naturally, can’t be held without the head of state,” referring to Putin’s observance of the exercise.

TOP LEFT: Putin views a strategic command post exercise in the Barents Sea in 2004. TOP RIGHT: Putin and President Belarus Lukashenko observe a February 2022 strategic deterrence forces exercise. BOTTOM LEFT: Putin attends a ceremony in December 2022 to raise the flag on the Generalissimus Suvorov SSBN and launch the Emperor Aleksandr III SSBN. BOTTOM RIGHT: Putin observes the frigate Admiral Kasatonov during the December 2023 commissioning ceremony of the Emperor Aleksandr III ballistic missile submarine and the Krasnoyarsk guided missile submarine.

While it is common for Putin to observe Russian nuclear force exercises and activities, this practice is not as customary in other nuclear-armed states. Leaders of other states will occasionally attend ceremonies or military parades that feature nuclear-capable weapons as a sign of power, but aside from in North Korea, heads of state do not regularly oversee nuclear weapons testing, exercises, and other related activities in person. Putin’s practice of uniquely observing these nuclear force drills or the commissioning of strategic weapons is presumably intended to signal the centrality of Russia’s nuclear weapons in its military doctrine.

Russian submarine fleet modernization

Submarines play a key role in Russia’s deterrence strategy, given that their stealth and survivability provide an important second-strike capability. The recent commissioning of new nuclear-powered submarines into the Pacific Fleet is a part of a larger modernization campaign as Russia’s older submarines begin to reach the ends of their service lives.

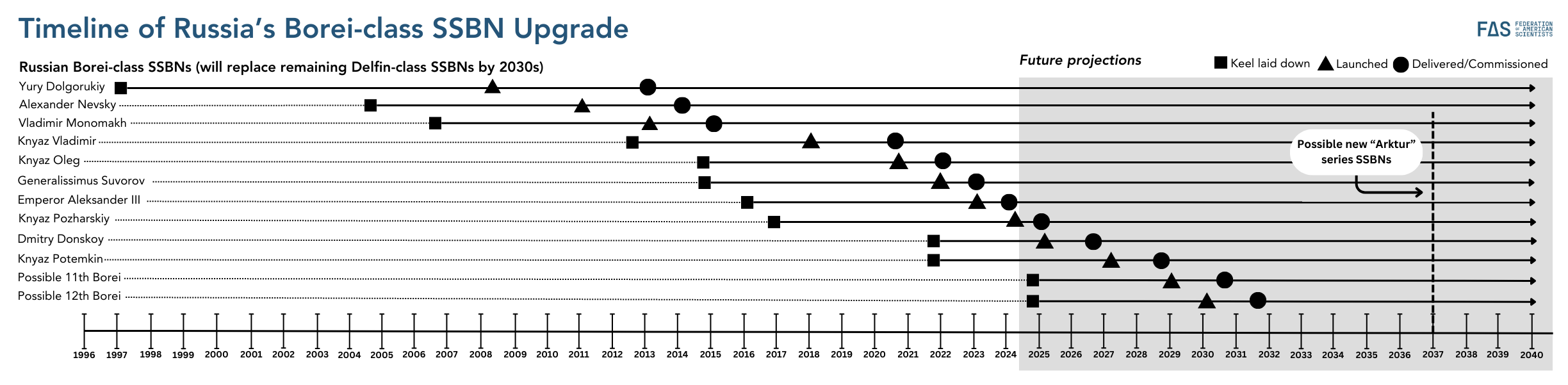

The Russian Navy currently operates two classes of SSBNs: five Delta IV (Project 667BRDM Delfin) and eight Borei (Project 955/A), five of which are the improved Borei-A (Project 955A) variant. The Emperor Alexander III––the submarine that Putin observed in December––is the seventh Borei-class submarine to enter service and the fourth of the upgraded Borei-A type. The Emperor Alexander III will be based with the Pacific Fleet located in the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Two additional Borei-A SSBNs are currently under construction, and two more are thought to be in the planning stages. Eventually, it is expected that six Borei SSBNs will be assigned to the Northern Fleet based in the Kola Peninsula, and six will be assigned to the Pacific Fleet. The new generation of Borei SSBNs will replace the Soviet-era Delta IV submarines, which are scheduled to be decommissioned throughout the late-2020s and early-2030s.

Each Borei submarine is capable of carrying 16 Bulava (SS-N-32) submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), which can carry up to six warheads each. However, it is likely that each missile has been downloaded to four warheads to comply with the New START limit on deployed strategic warheads. Although President Putin “suspended” Russia’s participation in New START in February 2023, Russian officials subsequently stated that Russia would continue to abide by the treaty’s central limits; if so, these SLBMs presumably still carry a reduced number of warheads. This limit falls away when the New START treaty expires in February 2026 unless it is replaced with a new agreement.

A possible next generation Russian strategic nuclear submarines concept – known as “Arktur” or “Arcturus” – was unveiled at the “Army 2022” International Military-Technical Forum and could potentially start replacing the Borei-class submarines sometime after 2037. Notably, an industry official said the Arktur-class will be smaller than the current Borei-class and have a reduced number of ballistic missiles. The design concept appears to allow the submarine to also carry other weapons as well as an unmanned underwater vehicle, which would imply a multi-mission role. New SSBN variants will also likely be equipped with reactor technology that extends the amount of time required between refueling, which will significantly shorten midlife maintenance operations and allow for more submarines to be on patrol at the same point in time.

In addition to strategic SSBNs, the Russian Navy operates sea-based nonstrategic nuclear weapons, including land-attack cruise missiles, anti-ship cruise missiles, torpedoes, and more, which can be launched from naval systems such as aircraft carriers, cruisers, frigates, corvettes, naval aircraft, and guided missile submarines such as the Krasnoyarsk––the other submarine that Putin observed in December.

The Russian Navy is also building submarines specially configured to carry a new nuclear-powered, long-range, nuclear-armed torpedo called Poseidon. The first of these submarines—Project 09852 Belgorod (K-329)—was delivered to the Russian Navy in July 2022 and reportedly will be capable of carrying up to six Poseidon torpedoes. The second submarine—Project 09851 Khabarovsk—is in the final stages of construction at the Sevmash Shipyard and will also reportedly carry up to six Poseidon torpedoes. One more specially configured submarine is planned to be delivered to the Russian Navy by 2027, for a total of at least three Poseidon-capable submarines.

Upgrades to Pacific Fleet infrastructure

A new division of specially configured submarines will reportedly be stationed with the Pacific fleet by the end of 2025. To support this expansion, as well as the additions of the Krasnoyarsk, Emperor Alexander III, and eventually more Borei submarines, infrastructure at the Pacific Fleet naval base in Kamchatka is undergoing significant renovations. In the past several years, Russia has added additional storage at the missile and warhead depots and begun construction of a new pier. These projects can be seen from satellite imagery captured by Planet Labs PBC.

The Rybachiy submarine base and warhead storage site at Kamchatka are being upgraded to support new Borei SSBNs as well as two new specially fitted submarines capable of carrying the long-range, nuclear-armed Poseidon torpedo.

While upgrades to the existing warhead storage facilities at the Rybachiy submarine base in Kamchatka began sometime after August 2013, construction of a new underground warhead storage facility began in early 2020 and is ongoing. The existing storage facility was built to accommodate warheads for now-decommissioned Delta III submarines, but those missiles could only carry three warheads on each missile. Since the new Borei SSBNs will be able to carry up to six warheads on each of its 16 SLBMs, the new facilities are likely meant for the Pacific Fleet to accommodate additional warheads as Russia completes the modernization of the submarine fleet in the coming years.

This new storage addition is also particularly interesting because of its unique design – the facility has a different layout than existing Russian naval warhead storage facilities in the Pacific and Northern Fleets and seems to be designed similarly to what the U.S. Navy has built for its Pacific SSBN fleet.

Construction of a new underground warhead storage facility at Russia’s Rybachiy Submarine base began in early 2020. This new facility has a different layout and has a larger storage capacity than existing Russian naval warhead storage facilities. The new design is also similar to what the U.S. Navy has built for its Pacific SSBN fleet with rows of long storage bays connected to technical and administrative facilities that are accessible via vehicle access ramps.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Upgrade Underway for Russian Silos to Receive New Sarmat ICBM

New satellite imagery shows that preparations to deploy Russia’s new RS-28 Sarmat (SS-29) intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) are well underway.

However, the imagery also indicates that President Putin’s claims of deployment “in the near future” may be too optimistic. It is potentially possible that one or two missiles could be deployed early, but major construction is still ongoing at many of the silos in the first regiment and has not yet begun at all of them, and the completion of construction at all eventual Sarmat regiments may be over a decade away.

The Sarmat––which was originally scheduled to enter service between 2018 and 2020 and will replace Russia’s aging RS-20V Voevoda (SS-18) ICBM––had been subject to significant manufacturing, production, and testing delays. In January 2022, the “War Bolts” Telegram channel reported that flight tests for Sarmat had been postponed due to problems with the missile’s command module. Following Sarmat’s eventual first test flight on 20 April 2022, Putin announced that the new ICBM would enter combat duty by the end of the year. As of October 2023, however, only one additional Sarmat flight test had reportedly taken place (in February 2023) and, according to US officials, likely ended in failure.

Despite the lack of successful tests, in November 2022 the General Director of the Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau––responsible for the design of Sarmat––claimed that the missile had already entered serial production. On 1 September 2023, Roscosmos Chief Yury Borisov announced that Sarmat had “assumed combat alert posture,” although this was likely premature: on 5 October 2023, President Putin noted during his speech at the Valdai Club that some “administrative and bureaucratic procedures” still needed to be carried out before Sarmat could be placed on combat duty, and on 7 October 2023, the Russian Ministry of Defence noted on Telegram that the “final stages” of construction and installation were still underway at the first launch facilities and associated command post.

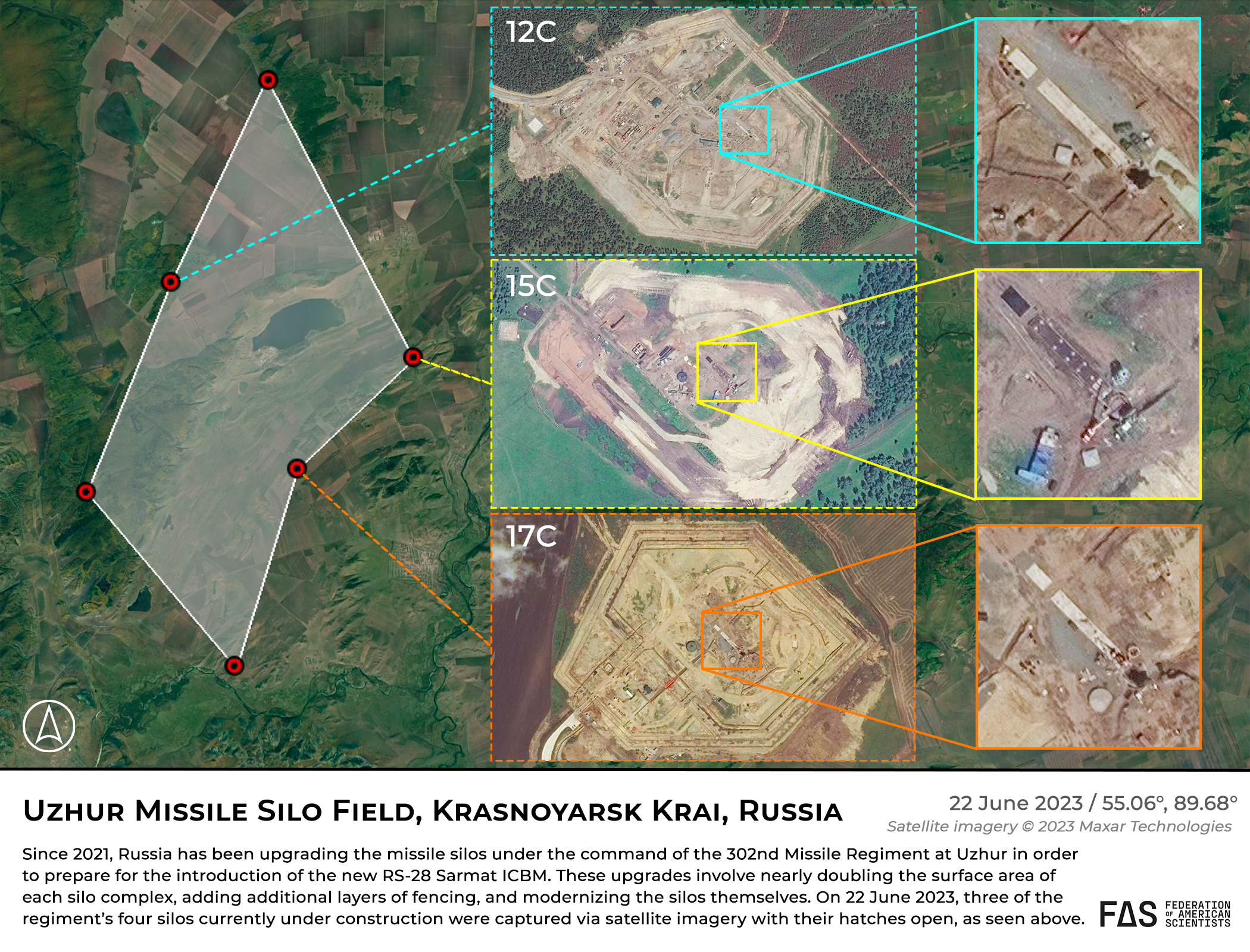

New satellite imagery indicates construction is well underway at the first regiment of the 62nd Missile Division near Uzhur in south Siberia. It is expected that a total of 46 Sarmat missiles will eventually be deployed with seven regiments (six missiles per regiment, plus one 10-missile regiment) in two divisions at Uzhur and Dombarovsky.

The first missile regiment undergoing its upgrade to Sarmat is the 302nd Missile Regiment and consists of six silos. Major construction continues at the launch control center and its accompanying silo (12C) and three other silos (13C, 15C, and 17C). The two remaining silos (16C and 18C) have only received minor upgrades and will take many months to complete if scheduled for the same comprehensive upgrade as the other silos.

Silos 12C and 17C:

The first two silos to begin their upgrades were Silos 12C (55.1144°, 89.6344°) and 17C (55.0347°, 89.7286°), which began their upgrades in the spring and summer of 2021, respectively. Over the past two years, the perimeters at both sites were removed, reshaped, and expanded with additional layers of fencing. The surface area of both silos has nearly doubled in size: Silo 12C has been expanded from approximately 0.228 square kilometers to 0.427 square kilometers, and the area of Silo 17C has been expanded from approximately 0.082 square kilometers to 0.136 square kilometers.

As of mid-September, construction appeared to be nearly complete inside the inner silo areas at both sites. The launch control center at Silo 12C has been upgraded to a newer LCC design that can also be seen at other Russian ICBM complexes, including the SS-27 Mod 1 “Topol-M” silo field near Tatishchevo, the SS-27 Mod 2 “Yars” silo field near Kozelsk, and the SS-19 Mod 4 “Avangard” silo field near Dombarovsky. In addition, Silo 12C boasts a new gun turret placement and expanded administrative area, although this outer area is not yet complete.

Notably, the immediate area surrounding Silo 17C has been subject to significant wildfire damage in the past. In 2017, a wildfire burned through all three sets of perimeter fencing and damaged the inner road leading to the silo hatch. In May 2021, another wildfire again burned through the three layers of fencing and appeared to damage an administrative building near the hatch.

Silos 13C and 15C:

Silos 13C (55.2008°, 89.7061°) and 17C (55.0822°, 89.8155°) began their upgrades in late-2022, nearly 1.5 years after construction on the first two silos began. As of mid-October 2023, significant construction at both sites was still underway, including underground and inside the silos themselves. Trees have been removed at both sites to make space for the expanded perimeter fences. While the new perimeters at both sites have been marked out, the multiple layers of fencing have not yet been completed. New gun turrets at both sites now appear to be in place.

Use the Planet Labs PBC interactive slider to compare before/after images.

Silos 16C and 18C:

As of mid-September 2023, full-site construction at Silos 16C (55.0247º, 89.5711º) and 18C (54.9501º, 89.6833º) had not yet begun, although some silo maintenance work has been visible since mid-2021, possibly in preparation for the full-site construction.

Open silos

It is notable that satellites have managed to capture images of all four silos currently under construction with their hatches open; on more than one occasion, multiple different silos could be seen with their hatches open on the same day, and in some cases hatches have stayed open for days at a time. This suggests that operations to upgrade the silos themselves and preparations to deploy Sarmat ICBMs inside them––as touted by high-ranking Russian officials––are well underway.

Additional information:

• Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Strategic Posture Commission Report Calls for Broad Nuclear Buildup

On October 12th, the Strategic Posture Commission released its long-awaited report on U.S. nuclear policy and strategic stability. The 12-member Commission was hand-picked by Congress in 2022 to conduct a threat assessment, consider alterations to U.S. force posture, and provide recommendations.

In contrast to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the Congressionally-mandated Strategic Posture Commission report is a full-throated embrace of a U.S. nuclear build-up.

It includes recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase its number of deployed warheads, as well as increasing its production of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warhead production capacity. It also calls for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal.

The only thing that appears to have prevented the Commission from recommending an immediate increase of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile is that the weapons production complex currently does not have the capacity to do so.

The Commission’s embrace of a U.S. nuclear buildup ignores the consequences of a likely arms race with Russia and China (in fact, the Commission doesn’t even consider this or suggest other steps than a buildup to try to address the problem). If the United States responds to the Chinese buildup by increasing its own deployed warheads and launchers, Russia would most likely respond by increasing its deployed warheads and launchers. That would increase the nuclear threat against the United States and its allies. China, who has already decided that it needs more nuclear weapons to stand up to the existing U.S. force level (and those of Russia and India), might well respond to the U.S and Russian increases by increasing its own arsenal even further. That would put the United States back to where it started, feeling insufficient and facing increased nuclear threats.

Framing and context