The Blackouts During the Texas Heatwave Were Preventable. Here’s Why.

On Monday, July 9, nearly 3 million homes and businesses in Texas were suddenly without power in the aftermath of Hurricane Beryl. Today, four days later, over 1 million Texans are entering a fourth day powerless. The acting governor, Dan Patrick, said in a statement that restoring power will be a “multi-day restoration event.” As people wait for this catastrophic grid failure to be remedied, much of southeast Texas, which includes Houston, is enduring dangerous, extreme heat with no air conditioning amid an ongoing heatwave.

Extreme Heat is the “Top Weather Killer”

As our team at FAS has explained, prolonged exposure to extreme heat increases the risk of developing potentially fatal heat-related illnesses, such as heat stroke, where the human body reaches dangerously high internal temperatures. If a person cannot cool down, especially when the nights bring no relief from the heat, this high core temperature can result in organ failure, cognitive damage, and death. Extreme heat is often termed the “top weather killer,” as it’s responsible for 2,300 official deaths a year and 10,000 attributed via excess deaths analysis. With at least 10 lives already lost in Texas amidst this catastrophic tragedy, excess heat and power losses are further compounding vulnerabilities, making the situation more dire.

Policy Changes Can Save Lives

These losses of life and power outages are preventable, and it is the job of the federal government to ensure this. Our team at FAS has previously called for attention to the soaring energy demands and unprecedented heat waves that have placed the U.S. on the brink of widespread grid failure across multiple states, potentially jeopardizing millions of lives. In the face of widespread blackouts, restoring power across America is a complex, intricate process requiring seamless collaboration among various agencies, levels of government, and power providers amid constraints extending beyond just the loss of electricity. There is also a need for transparent protocols for safeguarding critical medical services and frameworks to prioritize regions for power restoration, ensuring equitable treatment for low-income and socially vulnerable communities affected by grid failure events.

As a proactive federal measure, there needs to be a mandate for the implementation of an Executive Order or an interagency Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) mandating the expansion of public health and emergency response planning for widespread grid failure under extreme heat. This urgently needed action would help mitigate the worst impacts of future grid failures under extreme heat, safeguarding lives, the economy, and national security as the U.S. moves toward a more sustainable, stable, and reliable electric grid system.Therefore, given the gravity of these high-risk, increasingly probable scenarios facing the United States, it is imperative for the federal government to take a leadership role in assessing and directing planning and readiness capabilities to respond to this evolving disaster.

Building a Whole-of-Government Strategy to Address Extreme Heat

Comprehensive recommendations from +85 experts to enable a heat-resilient nation

From August 2023 to March 2024, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) talked with +85 experts to source 20 high-demand opportunity areas for ready policy innovation and 65 policy ideas. In response, FAS recruited 33 authors to work on +18 policy memos through our Extreme Heat Policy Sprint from January 2024 to April 2024, generating an additional +100 policy recommendations to address extreme heat. Our experts’ full recommendations can be found here. In total, FAS has collected +165 recommendations for 34 offices and/or agencies. Key opportunity areas are described below and link out to a set of featured recommendations. Find the 165 policy ideas developed through expert engagement here.

America is rapidly barreling towards its next hottest summer on record. While we wait for a national strategy, states, counties, and cities around the country have taken up the charge of addressing extreme heat in their communities and are experimenting on the fly. California has announced $200 million to build resilience centers that protect communities from extreme heat and has created an all-of-government action plan to address extreme heat. Arizona, New Jersey, and Maryland are all actively developing extreme heat action plans of their own. Miami-Dade County considered passing some of the strictest workplace heat rules (although the measure ultimately failed). Additionally, New York City and Los Angeles have driven cool roof adoption through funding programs and local ordinances, which can reduce energy demands, improve indoor comfort, and potentially lower local outside air temperatures.

While state and local governments can make significant advances, national extreme heat resilience requires a “whole of government” federal approach, as it intersects health, energy, housing, homeland and national security, international relations, and many more policy domains. The federal government plays a critical role in scaling up heat resilience interventions through research and development, regulations, standards, guidance, funding sources, and other policy levers. But what are the transformational policy opportunities for action?

Sourcing Opportunities and Ideas for Policy Innovation

During Fall 2023, FAS engaged +85 experts in conversations around federal policies needed to address extreme heat. Our stakeholders included: 22 academic researchers, 33 non-profit organization leaders, 12 city and state government employees, 3 private company leaders, 2 current or former Congressional staffers, 3 National Labs leaders, and 10 current or former federal government employees. Our conversations were guided by the following four questions:

- What work are you currently doing to address extreme heat?

- What do you see as some of the opportunity areas to address extreme heat?

- What are the existing challenges to managing and responding to extreme heat?

- What actions should the federal government take to address extreme heat?

Our conversations with experts sourced 20 high-demand opportunity areas for policy innovation and 65 policy ideas. To go deeper, FAS recruited 33 authors to work on +18 policy memos through our Extreme Heat Policy Sprint, generating an additional +100 policy recommendations to address extreme heat’s impacts and build community resilience. Our policy memos from the Extreme Heat Policy Sprint, published in April 2024, provide a more comprehensive dive into many of the key policy opportunities articulated in this report. Overall, FAS’ work scoping the policy landscape, understanding the needs of key actors, identifying demand signals, and responding to these demands has generated +165 policy recommendations for 34 offices and/or agencies.

Opportunities for Extreme Heat Policy Innovation

The following 20 “opportunity areas” are not exhaustive, yet can serve as inspiration for the building blocks of a future strategic initiative.

Facilitate Government-Wide Coordination

The first opportunity is an overarching call to action: the need for a government-wide extreme heat strategic initiative. This can build upon the National Integrated Health Health Information System’s (NIHHIS) National Heat Strategy, set to release this year. This strategy would define the problems to solve, create targets and galvanizing goals, set and assign priorities for federal agencies, review available resources for financial assistance, assess regulatory and rulemaking authority where applicable, highlight legislative action, and include evaluation metrics and timeline for review, adjustment, and renewal of programs. In creating this strategy, one interviewee recommended there should be a comprehensive review of “heat exposure settings” and federal actors that can safeguard Americans in these settings: homes, workplaces, schools and childcare facilities, transit, senior living facilities, correctional facilities, and outdoor public spaces. Through scoping potential regulations, standards, guidelines, planning processes, research agendas, and financial assistance, the federal government will then be prepared to support its intergovernmental actors and communities.

Infrastructure And The Built Environment

Accelerate Resilient Cooling Technologies, Building Codes, and Urban Infrastructure

On average, Americans spend 90% of their time indoors, making the built environment a critical site for heat exposure mitigation. To keep cool, especially in places of the U.S. not used to extreme heat, buildings are increasingly reliant on mechanical cooling interventions. While a life-saving necessity, air conditioning (AC) consumes significant amounts of electricity, putting high demands on aging grid infrastructure during the hottest days. Excess heat from air conditioners can lead to higher outdoor temperatures and even more AC demand. Finally, ACs are useless interventions if there’s no power, an increasing risk due to growing energy poverty and grid failure. In these scenarios, our current construction is likely to widely “fail” in its ability to cool residents.

Resilient cooling strategies, like high-energy efficiency cooling systems, demand/response systems, and passive cooling interventions, need policy actions to rapidly scale for a warming world. For example, cool roofs, walls, and surfaces can keep buildings cool and less reliant on mechanical cooling, but are often not considered a part of weatherization audits and upgrades. District cooling, such as through networked geothermal, can keep entire neighborhoods cool while relying on little electricity, but is still in the demonstration project phase in the United States. Heat pumps are also still out of reach for many Americans, making it essential to design technologies that work for different housing types (i.e. affordable housing construction). Initiatives like the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Affordable Home Energy Shot can bring these technologies into reach for millions of Americans, but only if it is given sufficient financial resources. DOE’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations and State and Community Energy Programs FY25 budget request to strengthen heat resilience in disadvantaged communities through energy solutions could be a step towards realizing innovative heat technologies. Further, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program can further incentivize low-power and resilient cooling technologies — if rebates are designed that take advantage of these technologies.

Thermal resilience of buildings must also be considered, for both day-to-day operations and emergency blackout scenarios. DOE can work with stakeholders to create “cool” building standards and metrics with human health and safety in mind, and integrate them into building codes like ASHREI 189.1 and 90 series. These codes are “win-wins” for building designers, creating buildings that consume far less electricity while keeping inhabitants safe from the heat. DOE can assist in conducting more demonstration projects for building strategies that ensure indoor survivability in everyday and extreme conditions.

Intervention efficacy and applicability are still evolving for extreme heat resilience interventions at the community scale, such as cool pavements, urban greening, shading, ventilation corridors, and development regulations (i.e. solar orientation). Individual interventions and their interactions need more evidence of their costs and benefits, potential tradeoffs and maladaptations. The National Institutes of Standards and Technology works on building and urban planning standards for other natural hazards, such as their National Windstorm Impact Reduction Program (NWIRP) and their Community Resilience program, and could serve as a “technology test-bed” for heat resilience practices and advance our understanding of their effectiveness as well as how to measure and account for benefits and costs. This could be done in partnership with the National Science Foundation, which has been dedicating funding for use-inspired research and technology development for climate resilience.

Finally, the U.S. government is the largest landlord in the nation. As the General Services Administration is rapidly decarbonizing its buildings, it can also be a test site for new technologies, building designs, planning, and resilience metrics development and analysis.

Adapt Transportation to the Heat

Public transportation is a site of high exposure to extreme heat. While the Department of Transportation’s Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-saving Transportation (PROTECT) grants are for “surface transportation resilience,” multiple of our local and regional government interviewees expressed difficulty successfully applying to these grants for “cooling” infrastructure, like water fountains, shade, and air-conditioned bus shelters. DOT should make extreme heat resilience explicit in its eligibility requirements as well as review the benefit-cost analysis (BCA) formula and how it might disadvantage cool infrastructure.

Asphalt and concrete roadways contribute to the urban heat island effect and hotter weather makes asphalt in particular more vulnerable to cracking. DOT should leverage its research and development (R&D) capabilities to develop and deploy reflective and cool materials as a part of transportation infrastructure improvements. Finally, DOT should also consider the levers available to incentivize cool surfaces and cool materials as a part of transportation construction.

Create More Heat-Resilient Schools for Sustained Learning

Higher temperatures combined with minimal to no air conditioning in older school buildings have led to an increase in the number of “heat days”, or school closures due to dangerous temperatures. Pulling children out of the classroom not only negatively impacts them, but also puts increasing strain on families that rely on schools as childcare. Even when school is in session, many students are attempting to learn in classrooms exceeding 80°F, a temperature threshold where studies have repeatedly shown that students struggle to learn and fall short of true academic performance. This is because heat reduces cognitive function and ability to concentrate – both essential to learning. Learning loss from rising heat will only compound the learning losses from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Environmental Protection Agency predicts that the total lost future income attributable to heat-related learning losses may reach $6.9 billion at 2°C (a threshold we are well on the way to meeting) and $13.4 billion at 4°C. Schools need guidance on how to deal with the heat crisis currently at hand, while being supported as they plan necessary climate adaptations needed for a hotter world.

At a minimum, schools can be encouraged to formalize plans for school heat preparedness to protect both the health of students and safeguard their learning. No federal heat safety recommendations yet exist and thus will need to be created by the Department of Education (Ed), EPA, FEMA, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and others. Title I Grants, in alignment with Justice40, could then assist schools in adapting to climate change that includes researched guidance on ways to cool students indoors, outdoors, and through behavioral management. Further, school system leaders need a better system to track how schools are currently experiencing extreme heat and what strategies could be employed to respond to heat exposure (closing schools, informed behavioral interventions to manage heat exposure, green infrastructure to build resilience, etc). Federal involvement is essential for creating this tool. Finally, to address the root causes of excessive classroom heat, schools will need to transform their infrastructure through HVAC investments and improvements, greening, playground material changes and shading. HVAC costs alone are expected to be $40 billion for all U.S. schools that need infrastructure improvements. While Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) tax credits are available for updating HVAC systems, many low-wealth schools will not be able to finance the gap between the credit coverage and the true cost and will need additional financial assistance.

Make Housing and Eviction Policy More Climate-Aware and Resilient

Most of the U.S. lacks minimum cooling requirements for buildings and existence of a cooling device within the property. Adoption of the latest building energy codes, despite their previously described limitations, can still be a cost-saving and life-saving advancement according to research by the DOE. For new properties, the Federal Housing Finance Agency could require that they adhere to the latest energy codes to receive a mortgage from Government Sponsored Enterprises, which is already under consideration by Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) for their mortgage products. For older construction, there could be requirements for adequate cooling to exist in the property at the point of sale.

For all property types, weatherization audits, through the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) and Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), can be expanded to consider heat resilience and cooling efficiency of the property and then identify upgrades such as more efficient HVAC, building envelope improvements, cool roofs, cool walls, shade, and other infrastructure. If cooling the entire property is unfeasible or costly, homeowners could benefit from creating “Climate Safe Rooms” which are guaranteed to be safe during a heat wave. DOE and HUD could collaborate to demonstrate climate safe rooms in affordable housing, where many residents lack access to consistent cooling.

Some housing types are more risky than others. People living in manufactured homes in Arizona were 6 to 8 times more likely to die indoors due to extreme heat. This is because of poorly functioning or completely defunct cooling systems and/or inability to pay electric bills. Manufactured home park landlords can also set a variety of rules for homeowners, including banning cooling devices like window ACs and shade systems. While states like Arizona have now passed laws making these bans illegal, there is a need for a nationwide policy for secure access to cooling. HUD does not regulate manufactured homes parks, but does finance the parks through Section 207 mortgages and could stipulate park owners must guarantee resident safety. Finally, HUD could also update the Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards to allow for HVAC and other cooling regulations in local building codes to apply to manufactured homes, as they do for other forms of housing, as well as require homes perform to a certain level of cooling under high heat conditions.

Renter’s are another highly vulnerable population. Most states do not require landlords to provide cooling devices to tenants or keep housing below risky temperatures. HUD for example does not require cooling devices in public housing, although regulations exist for heating. HUD could implement similar guarantees of a “right to cool”. Evictions in the summer months are also on the rise, due to rising rents compounded with rising energy costs, putting people out in the deadly heat. Keeping people in housing should be of the utmost importance, yet implementation remains fractured across the nation. Eviction moratoriums at a national level have been challenged by the Supreme Court, which overturned the CDC’s COVID-19 moratorium.

Address Communities’ Needs for Long-Term Infrastructure Funding Support

Heat vulnerability mapping has advanced significantly in the past few years. Federal programs like the NIHHIS’s Urban Heat Island Mapping Campaigns have mapped +60 communities in the United States that have guided city policy. The Census’ new product, Community Resilience Estimates (CRE) for Heat, assesses vulnerability at the level of individuals and households. Finally, researchers and non-profit organizations have been developing tools that can assess risk and also aid in individual or local decision-making, such as the Climate Health and Risk Tool and Heat FactorⓇ.

Advancements in our understanding of heat’s impacts and potential interventions have not translated to sustained resources to support transformative infrastructure development. As one interviewee put it “communities that have mapped their urban heat islands are still waiting on funding opportunities to build relevant infrastructure projects”. Federal grants for mitigation and resilience may or may not consider heat resilience projects “cost-effective” and aligned with grant-making objectives, leading to rejection.

FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grants (HMGP), made available only after a federally-declared disaster, can only be used for extreme heat in specific circumstances and recommends that cost-effective heat mitigation projects will also “reduce risks of other hazards”. Another example, FEMA’s BRIC grant has rejected cooling centers, HVAC upgrades, and weatherization activities, all strategies with some benefit to preventing morbidity and mortality. Green infrastructure projects, with co-benefits such as flood mitigation, have been more successful, often because the BCA is based on the property-damaging hazard, flooding. Only one FEMA BRIC project has been funded with heat as the main hazard, an urban greening project in Portland, Oregon. This unknown regarding grant success can lead to communities not applying with a heat-focused project, when time could be better spent securing grants for other community priorities. FEMA’s announcement that it will fund net-zero projects, including passive heating and cooling, through its HMGP and BRIC programs and Public Assistance could shift the paradigm, yet communities will likely need more guidance and technical assistance to execute these projects.

To invest in resilience to the growing risk of heat, policymakers will need to create a dedicated and reliable funding resource. Federal stakeholders can look to the states for models. California’s Integrated Climate Adaptation and Resiliency Program’s Extreme Heat and Community Resilience grants are currently slated to allocate $118 million to 20-40 communities for planning and implementation grants over three rounds. To start, FEMA could replicate this program, similar to its specific programs for wildfires, providing $50,000 to $5 million to a wide range of heat resilience projects, and make it eligible for joint funding through BRIC. DOE’s $105 million FY25 budget request for a program for planning, development, and demonstration of community-scale solutions to mitigate extreme heat in low-income communities is a step in the right direction. If funded, the program would benefit from coordinating with FEMA’s BRIC program on high-impact solutions.

Workforce Safety And Development

Set Indoor and Outdoor Temperature Standards and Workplace Protections to Protect Human Health

Our understanding of when heat becomes risky to human health and impacts daily governance is still in development. Our interviewees shared that there is not yet consensus or agreement on the lower threshold for 1) when outdoor and indoor temperatures risks begin and 2) at what level of continued exposure should there be cause for action, such as implementing breaks for workers or deploying rapid emergency cooling to residents. For workplaces, guidelines will come soon: the Occupational Health and Safety Administration (OSHA) is set to release their heat standard for indoor and outdoor workers by the end of 2024, which will advance heat safety for workers across the country. For all other settings (such as residential settings and schools), the jury is still out on a valid threshold and a regulatory mechanism to establish it.

Enforcement of standards is necessary for realizing their full potential. In preparation for a workplace heat standard, interviewees recommended the Department of Labor create an advanced Hazard Alert System for Heat (using an evolved data standard discussed in a later section) in order to better pinpoint regulatory enforcement. Small businesses will also need help to be prepared for compliance with the new standard. DOL and the Small Businesses Administration should consider setting up a navigator program for resourcing energy-efficient, worker-centric cooling strategies, leveraging IRA funds where applicable.

Build the Extreme Heat Resilience Workforce

Extreme heat is not just a challenge to worker health, it’s also a challenge to workforce ability and capacity. As heat becomes a threat to the entire nation, many fields are needing to rapidly adapt to entirely new knowledge bases. For example, much of the health workforce, doctors, nurses, public health workers, receive little to no education on climate change and climate’s health impacts. Programs are beginning to crop up, such as Harvard’s C-Change Program, yet will need support to scale. With the federal government being the nation’s largest single source funder of graduate medical education, there are many levers at their disposal to develop, incentivize, and even require climate and health education. The U.S. Public Health Commissioned Corps is another program that could mobilize a climate-aware health workforce, placing professionals with a deep awareness of climate change’s impact on health in local communities.

The weatherization and decarbonization workforce must also be made aware and ready for heat’s growing impacts and emerging strategies to build building and community-scale resilience. While promising strategies exist for heat mitigation, such as cool walls and roofs, these interventions are largely not considered during weatherization audits and energy efficiency audits. Tax credits that have been created by the IRA/BIL could be used for interventions for passive or low-energy cooling, yet a lack of clarity prevents their uptake and implementation. For example, EPA’s EnergyStar program used to certify roofing products before the program sunsetted in 2022. Stakeholders at DOE and EPA should consider their role in workforce readiness for extreme heat, collaborating with third party entities to build awareness about these promising strategies.

Navigating all of the benefits of the IRA and BIL is challenging for resource-strapped communities and households. Program navigators for weatherization assistance and resilience could be an incredible asset to low-resource communities, and leverage IRA resources for technical assistance as well as the newly created American Climate Corps.

Finally, the federal government workforce is being stretched thin by the sheer number of new mandates in IRA and BIL. To meet the moment, agencies have used flexible hiring mechanisms like the Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPAs) and for some offices its BIL and IRA connected Direct Hire Authority to make those critical talent decisions and staff their agencies. DOE, for example, has exceeded its goals – hiring over 1000 new employees to date. But not all agencies and offices have access to the Direct Hire Authority – and it’s set to expire anywhere between 2025 (for IRA) and 2027 (for BIL). Congress should be encouraged to expand this authority, extend it beyond 2025 and 2027 respectively, and remove the limit on the number of staff allowed. Further, agencies should be encouraged to use other flexible hiring mechanisms like IPAs and other termed positions. The federal government should have the talent needed to meet its current mandates and be prepared to solve problems like extreme heat.

Public Health, Preparedness, And Health Security

Build Healthcare System Preparedness

Years of underinvestment in preparedness have impacted U.S. health infrastructure’s surveillance, data collection, and workforce capacity to respond to emerging climate threats like extreme heat. The Administration for Strategic Planning and Response’s Hospital Preparedness Program, which prepares healthcare systems for emergencies, has had its budget reduced by 67% from FY 2002-FY2022, considering inflation. Further, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has seen a 20% budget reduction from FY 2002-2022. The CDC’s Climate Ready States and Cities Initiative can only support nine states, one city, and one county, despite 40 jurisdictions having applied. The Trust for America’s Health (TFAH) found increasing funding from $10 million to $110 million is required to support all states, and improve climate surveillance. The TFAH also found that an additional $75 million is needed to extend the CDC’s National Environmental Public Health Tracking Program, a program that tracks threats and plans interventions, to every state. Finally, the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity, the sole office within Health and Human Services solely dedicated to the intersection of climate and health, has yet to receive direct appropriations to support its work.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) and the Healthcare Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) provide critical investments to healthcare facilities, operations, care provision, and the medical workforce, yet have no publicly available programs dedicated to building climate resilience in the face of rising temperatures. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA), the largest integrated healthcare system in the U.S., includes responding to heat wave exposure in its agency Climate Action Plan and has made commitments to developing biosurveillance systems that incorporate external data on air quality, temperature, heat index, and weather as well as upgrading medical center infrastructure. This is critical as 62% of VHA medical centers are exposed to extreme heat and the VHA sees a rise in heat-related illness in the Veteran population. Given its sheer size, systems changes like this made by the VHA can drive real change in healthcare practice.

To build resilience to extreme heat within healthcare systems, our interviews and literature review highlighted that these three actions are most critical: 1) increasing surveillance and tracking of heat-related illness through improvements to medical diagnosis and coding practices and technological systems (i.e. EHRs); 2) leveraging healthcare financing for preventative treatments (i.e. cooling devices), incentives for climate-change preparedness, accurate coding and treatment, and quality care delivery (CQIs), and requirements for accreditation and reimbursements; and 3) fostering capacity-building through grants, technical assistance, planning support and guidance, and emergency preparedness.

Design Activation Thresholds for Public Health, Medical, and Emergency Responses

Despite the fact that extreme heat events have overwhelmed local capacity and triggered local disaster declarations, heat is not explicitly required in healthcare preparedness efforts authorized under the Pandemics and All Hazards Preparedness Act (PAHPA), insufficiently included or not included at all in local and state hazard mitigation plans required by FEMA, and there has yet to be a federal disaster declaration for heat. This all inhibits the deployment of federal resources to mitigation, planning, and response that states and local jurisdictions rely on for other hazards. Our interviewees recommended that there needs to be better “activation thresholds” for heat i.e. markers that the hazard has reached a level of impact that needs additional capacity and resources. Most thresholds set right now just rely on high-temperatures, not the risk factors that exacerbate the impacts of heat. Data inputs into these locally-relevant thresholds can include wet-bulb globe temperature (which accounts for humidity), heat stress risk, level of acclimatization, nighttime temperatures, building conditions and cooling device uptake, work situations, other compounding health risks like wildfire smoke, and other factors. These activation thresholds should also be designed around the most heat-vulnerable populations, such as children, the elderly, pregnant people, and those with comorbidities.

Increased transmission of viral pathogens and pathogen spread is also a growing risk of overall hotter average temperatures that needs more attention. Increased pathogen surveillance and correlation with existing climate conditions would greatly enable U.S. pandemic and endemic disease surveillance. Finally, no program to date at the Biomedical Advanced Development and Research Authority has focused on creating climate-aware medical countermeasures and the 2022-2026 strategic plan includes no mention of climate change.

Reduce Energy Burdens, Utility Insecurity, and Grid Insecurity

As temperatures rise, so do energy bills. Americans are facing an ever-growing burden of energy debt. 16% (20.9 million people) of U.S. households find themselves behind on their energy bills, increasing the risk of utility shut-offs due to non-payment. The Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) exists to relieve energy burdens, yet was designed primarily for heating assistance. Thus, the LIHEAP formulas advantage states with historically frigid climates. Further, most states use their LIHEAP budgets for heating first, leaving what remains for cooling assistance (or just don’t offer cooling assistance at all). As a result, nationally from 2001-2019, only 5% of energy assistance went to cooling. Finally, the LIHEAP program is massively oversubscribed, and can only service a portion of needy families. To adapt to a hotter world, LIHEAP’s budgets must increase and allocation formulas will need to be made more “cooling”-aware and equitable for hot-weather states. The FY25 presidential budget keeps LIHEAP’s funding levels at $4.1 billion, while also proposing expanding eligible activities that will draw on available resources. The National Energy Assistance Directors Association recent analysis found that this funding level could cut ~1.5 million families from the program and cut program benefits like cooling.

Another key issue is that 31 states have no policy preventing energy shut-offs during excessive heat events and even the states that have policies vary widely in their cut-off points. These cut-off policies are all set at the state level, and there is still an ongoing need to identify best practices that save lives. While the Public Utility Regulatory Policies Act of 1978 (PURPA) prohibits electric utilities from shutting off home electricity for overdue bills when doing so would be dangerous for someone’s health, it does not have explicit protections for extreme weather (hot/cold). Reforms to PURPA could be considered that require utilities to have moratoriums on energy shut-offs during extreme heat seasons.

Finally, grid resilience will become even more essential in a hotter climate. Power outages and blackouts during extreme heat events are deadly. If a blackout were to occur in Phoenix, Arizona during the summer, nearly 900,000 people would need immediate medical attention. Rising use of AC itself is a risk factor for blackouts due to increases in energy demand. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), a regulatory organization that works to reduce risks to power grid infrastructure, issued a dire warning that two-thirds of the U.S. are facing reliability challenges because of heatwaves. Ensuring grids are ready for the climate to come should be top priority for DOE, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). Given the risks to human health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should work with public health organizations to prepare for blackouts and grid failure events.

Address Critical Needs of Confined Populations Facing Heat

Confined populations, whether because of their medical status or legal status, are vulnerable to extreme heat indoors. Long-term care facilities are required by law to keep properties within 71-81℉. Yet, long-term care facilities are reporting challenges actually meeting resident’s needs in a disaster, such as a power outage, calling for a need for more coordination with CMS.

Incarcerated populations on the other hand are not guaranteed any cooling, even as summers become more brutal. This directly leads to an increase in deaths, 45% of U.S. detention facilities saw spikes in deaths on hazardous heat days from 1982 to 2020. Despite this lack of sufficient cooling being “cruel and unusual” punishment, there has been no public activity to date from the Department of Justice to secure cooling infrastructure for federal prisons or work with state prisons to expand cooling infrastructure. The National Institute of Corrections does recommend ASHRAE 55 Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy to corrections institutions, though this metric needs to be updated for our evolving understanding of extreme heat’s risks to human health.

Food Security And Multi Hazard Resilience

Anticipate and Prevent Supply Chain Disruptions

Hotter temperatures are changing the landscape of American and global food production. 70% of global agriculture is expected to be affected by heat stress by 2045. Recent heat waves have already killed crops and livestock en masse, leading to lower yields and even shortages for certain products – like olive oil, potatoes, coffee, rice, and fruits. Rising heat is also poised to reshape local and state economies that rely on their changing climatic capabilities to produce certain crops. Oranges, a $5 billion dollar industry for Florida, are struggling in the heat which stresses the trees and provides fertile ground for pathogens. As a result, Florida is facing its worst citrus yield since the Great Depression. A decrease in winter chill is another growing risk, as many perennial crops have adapted to certain amounts of accumulated winter chill to develop and bloom. Winter-time heat is shaking up plants’ biological clocks, decreasing quality and yield. Overall, extreme heat is impacting American household bottom lines in the short-term and long-term through heat-exacerbated earning losses and spiking food prices.

Ensuring ongoing access to critical commodity and specialty agricultural products in a future of higher temperatures is a national security priority. Resilience of products to extreme heat could be included as a future requirement in the Federal Supplier Climate Risks and Resilience Rule that governs Federal Acquisition Regulations. Further, FAS’ work scoping the federal landscape has shown there are few federal research and development programs, financial assistance opportunities, and incentives for heat resilience, and our interviewees concurred with that assessment. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) can prepare farmers for future climate risks and hotter temperatures, ensuring consistent food production and reducing the losses and needed economic pay-outs from the USDA through crop insurance and disaster assistance. The USDA can accelerate advances in biotechnology and genetic engineering to improve heat resilience of agricultural products while also encouraging practices like shade, effective water management, and soil regeneration that build system-wide resilience. As Congress continues to consider reauthorizations and appropriations for the Farm Bill, they should consider fully funding the Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority to advance resilient agriculture R&D while also increasing funding to the USDA Climate Hubs to support roll-out of heat resilient practices.

Connect Drought Resilience and Heat Resilience Strategies

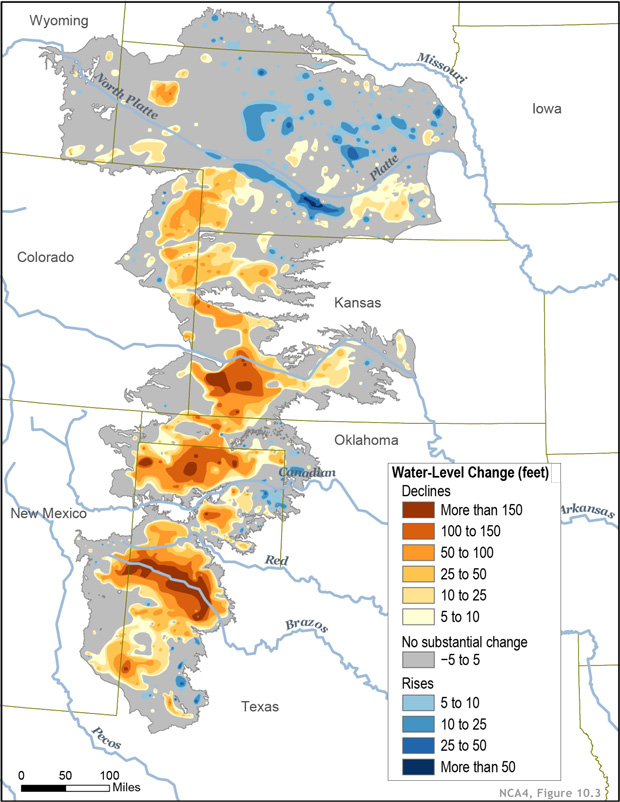

Hotter winters have literal downstream consequences. Warming is shrinking the snowpack that feeds rivers, leading to further groundwater reliance, straining aquifers to the brink of complete collapse. Warmer temperatures also leads to more surface water evaporating, thus leaving less to seep through the ground to replenish overstressed aquifers. Rising temperatures also mean that plants need more water, as they evapotranspirate at greater rates to keep their internal temperatures in-check. All of these factors compound the growing risk of drought facing American communities. Drought, now made worse by high heat conditions, accounts for a significant portion of annual agricultural losses. 80% of 2023 emergency disaster designations declared by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) were for drought and/or excessive heat. Secure access to water is an escalating catastrophe, and to address it requires a national strategy that accounts for future hotter temperatures and how they will put strain on water accounts necessary to sustain agricultural production and human habitation.

Heat and dry weather/drought also combine to make prime conditions for megawildfires. The smoke then generated by these fires compounds the health impacts of extreme heat, with research showing that concurrent effects of heat and smoke drive up the number of hospitalizations and deaths. More funding from Congress is needed to improve wildfire forecasting and threat intelligence in the era of compounding hazards.

Planning And Response

Reform the Benefit-Costs Analysis

Benefit cost analysis (BCA) is a critical tool for guiding infrastructure investments, and yet is not set up to account for the benefits of heat mitigation investments. When the focus of the BCA is mitigating property damage and loss of life, it will discount impact’s that go beyond those damages such as economic losses, learning losses, wage losses, and healthcare costs. Research will likely be needed to generate the pre-calculated benefits of heat mitigation infrastructure, such as avoiding heat illness, death, and wage losses and preventing widespread power failures (a growing risk). Further, strategies that enhance an equitable response, articulated in the recent update to the Office of Management and Budget’s Circular A-4, need to be quantified. This could include response efforts that protect the most vulnerable populations to extreme heat, such as checking in on heat sensitive households identified by the CRE for Heat. Developing these metrics will take time, and should be done in partnership with agencies like the DOE, EPA, and CDC. Finally, FEMA’s BCA is often based on a single hazard, the one with the highest BCA ratio, making it more challenging to work on multi-hazard resilience. FEMA should develop BCA methods that allow for accounting of an infrastructure investment for community resilience to many hazards (like resilience hubs).

Create the “Plan” for How the Federal Emergency Management Agency and Others Should Respond to an Extreme Heat Disaster

Extreme heat’s extended duration, from a few days to several months, poses a significant challenge to existing disaster policy’s focus on acute events that damage property. An acute focus on infrastructure damages by FEMA has been an insurmountable barrier to all past attempts to declare extreme heat as a disaster and receive federal disaster assistance. Because in theory, FEMA can reimburse state and local governments for any disaster response effort that exceeds local resources, including heat waves. Our interviewees acknowledged that federal recognition that heat waves are disasters will only come with extending the definition of what a disaster is.

New governance models will need to be created for climate and health hazards like extreme heat, focusing on an adaptation forward, people-centered disaster response approach given the outsized impact of heat hazards on human health and economic productivity. Such a shift will challenge the federal government’s existing authorities authorized under national disaster law, the Stafford Act, which at this current moment does not consider “human damages” beyond loss of life. Thus, we do not see how existing infrastructure fails to provide critical function during these heat hazard events, such as secure learning, secure workplaces, secure municipal operations, secure healthcare delivery, and resultantly strains or exceeds local resources to respond. By quantifying more of these damages, there will then be an existing incentive to design responses that address current impacts and plan for and mitigate future impacts.

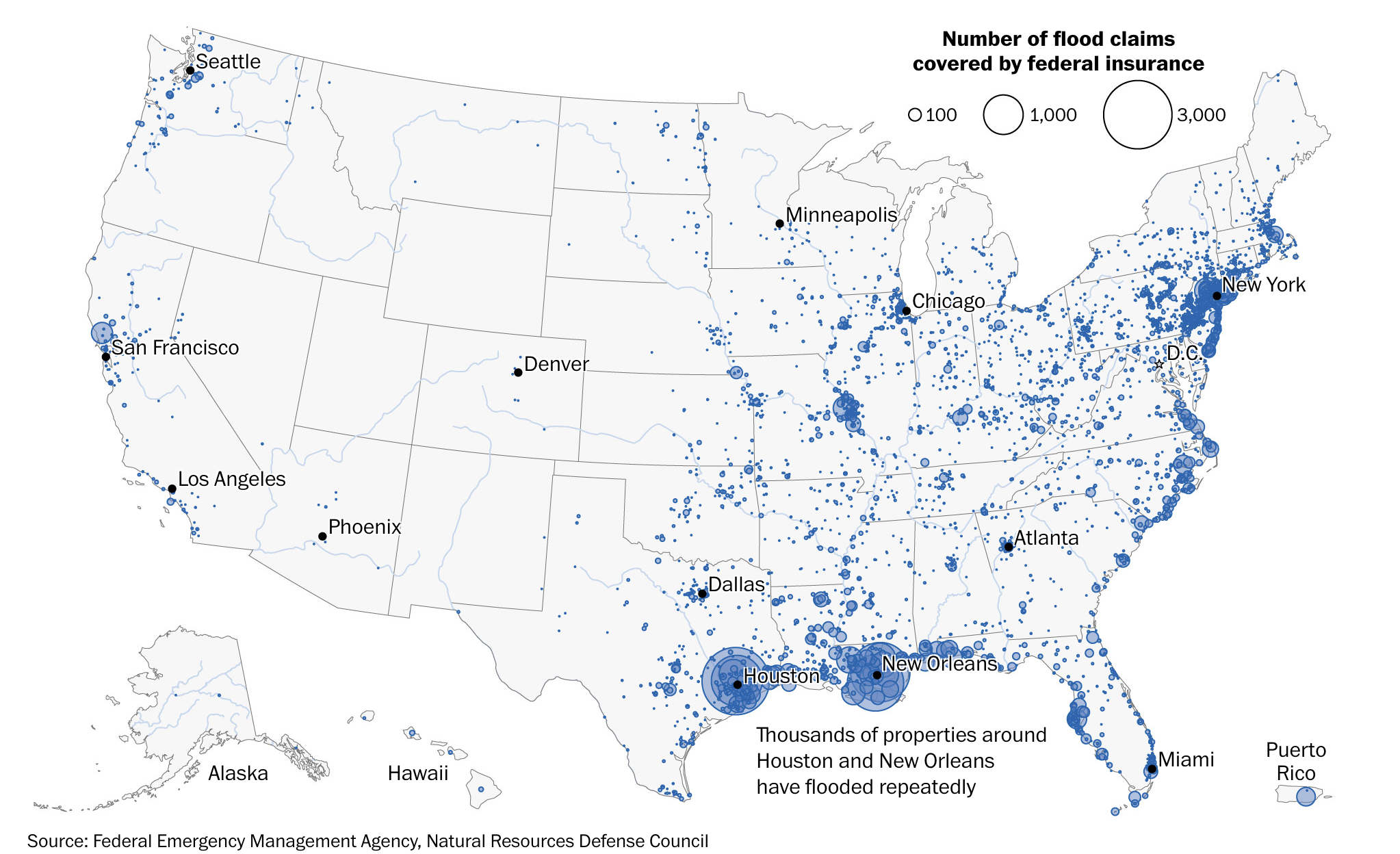

Finally, there are highly-risky heat disasters that we need to be executing planning scenarios for, specifically an extended power outage in a city under high-heat conditions. A power outage during the summer in Phoenix would send 800,000 people to the emergency room, which would very likely overwhelm local resources and those of all surrounding jurisdictions. There is a need for a power outage during an extended heat wave to be an included planning scenario for emergency management exercises lead by state and local governments. FEMA should produce a comprehensive list of everything a city needs to be prepared for a catastrophic power outage.

Spur Insurance and Financing Innovation

While insurance is the countries’ largest industry, few insurance products and services exist in the U.S. to cover the losses from extreme heat. The U.S. Department of the Treasury recently acknowledged this lack of comprehensive insurance for extreme heat’s impacts in its comprehensive report on how climate change worsens household finances. Heat insurance for individuals could manifest in a variety of ways: security from utility cost spikes during extreme weather events, real-estate assessment and scoring for future heat-risk, “worker safety” coverage to protect wages during extremely hot days where it might be unsafe to work, protections for household items/resources lost due an extended blackout or power outage, and full coverage for healthcare expenses caused by or exacerbated by heat waves. California is currently leading the country on thinking through the role of the insurance industry in mitigating extreme heat’s impacts, and should be a model to watch by federal stakeholders to see what can be scaled and replicated across the nation.

Further, it is important that investments made today are resilient for the climate conditions of tomorrow. The Office of Management and Budget’s November 2023 memo on climate-smart infrastructure, currently being implemented, provides technical guidance on how federal financial assistance programs can and should be invested in climate resilience. A yet unexplored financial lever for climate resilience identified in our interviews is federally-backed municipal bonds. Climate change is undermining this once stable investment, as cities and local governments struggle to pay back interest due to the rising costs of addressing hazards. The municipal bond market could price climate risk when deciding on interest payments, and give beneficial rates to jurisdictions that have done a full analysis of their risks and made steps towards resilience.

Finally, there is a need to update assessments of heat risk that are used to make insurance and financial decisions. Recent research by the DOE has found that the FEMA NRI property damage data appear to be deficient and underestimate damages when compared to published values for recent U.S. extreme temperature events. To start, FEMA should consider including metrics in its NRI that characterize the building stock (i.e. by adherence to certain building codes) and its thermal comfort levels (even with cooling devices) as well as thermal resilience.

Incorporate Future Climate Projections into Planning at All Levels

Recent research has shown that cities and counties are barreling toward temperature thresholds at which it would be dangerous to operate municipal services, affecting the operations of daily life. Yet little of this future risk is accounted for in the various planning activities (for public health, emergency preparedness, grid security, transportation, urban design, etc) done by local and state governments. Our interviewees expressed that because many plans are based on historical and current risk data, there is little anticipation of the future impacts of hotter temperatures when making current planning choices.

One example stood out around nature-based solutions (NBS): while NBS has received over a billion dollars in federal funding and is argued as an approach to mitigate extreme heat’s impacts – planners are not always considering whether the trees planted today will survive effectively in 20-30 years of warming. Reporting has shown that Southern Nevada is at risk of losing many of its shade trees due to inadequate species selection, as the trees that once thrived in this climate exceed their zones of heat tolerance.

Changes are being made to some federally-required planning processes to require assessment of future risk. FEMA’s National Mitigation Planning Program now requires state and local governments to plan for future risks caused by climate change, land use, and population change to receive emergency disaster funds and mitigation funding. While extreme heat is a noteworthy future risk, it is not explicitly required in the new guidelines. As of April 2023, only half of U.S. states had a section dedicated to extreme heat in their Hazard Mitigation Plans.

Climate.gov, operated by NOAA, was a recommended starting place for a library of future climate files that can be brought into planning processes and resilience analysis. Technical assistance and decision-making tools that support planners in making predictive analyses based on future extreme temperature conditions can help inform the effective design of resilient transportation systems, infrastructure investments, public health activities, and grids, and ensure accurate estimations of investment cost effectiveness over the measure lifetime.

Data And Indices

Set Standards for Data Collection and Analysis

While official CDC-reported deaths from heat, approximately 1670 in 2022, exceed those from any other natural hazard, experts widely agree this number is an undercount. True mortality is likely at a rate of 10,000 deaths a year from extreme heat under current climate conditions. Many factors compound this systematic undercount: hospitals often do not consider extreme heat in their hazard preparedness plans, there’s a lack of awareness around ICD-10 coding for heat illness, death attribution exacerbated/caused by heat is often attributed to other causes. Retraining the healthcare workforce and modernizing death counting for climate change will take time, our interviewees acknowledged. Thus, decision makers need better data and surveillance systems now to address this growing public health crisis. Excess deaths analysis could provide a proxy data point for the true number of heat deaths, and has already been employed by California to assess the impact of past heat waves. The CDC has utilized excess death methods in tracking the COVID-19 pandemic, and could apply this analysis to “climate killers” like extreme heat to inform healthcare system planning ahead of Summer 2024 (such as forecasting tools like HeatRisk). It will be critical to set a standard methodology in order to compare heat’s impacts in different communities across the United States. True mortality is also essential to enhancing the benefit-cost analysis for heat mitigation and resilience.

Our conversations also highlighted the data gaps that exist around counting worker injuries and deaths due to extreme heat. For work-related heat-health impacts, injuries or deaths are often only counted if there’s a hospital admission that is a required report, heat-exacerbated injuries (i.e. falls) aren’t often counted as heat-related, and harms off the job (i.e. long-term kidney impacts) go unnoticed. Studies estimate that California alone saw 20,000 heat injuries a year, while The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) reports only 3400 injuries a year nationally. DOL could track how overall workplace injuries correlate with temperature to develop a methodology that would yield much more accurate numbers around true heat impacts.

Finally, anticipating the full risks of heat due to factors like existing infrastructure, social vulnerability, and levels of community resilience, remains a work in progress. For example, FEMA’s National Risk Index (which informs environmental justice tools like the Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool and the Community Disaster Resilience Zones program) has notable limitations due to its reliance on previous weather data and narrow focus on mortality reduction, leading to underestimates of damages when compared to published values for recent U.S. extreme temperature events. There is a big opportunity to develop a standard data set for extreme heat risks and vulnerabilities in current and future anticipated climate conditions. This data set can then produce high-quality and relevant tools for community decision making (like FEMA’s Flood Maps) and inform federal screening tools and funding decisions.

Create Regulatory Oversight Infrastructure for Extreme Heat

There are only a few regulatory levers currently in place or in the regulatory pipeline to protect Americans from the growing heat and build more heat resilient communities. These include the temperature standards for senior living facilities set by CMS and OSHA’s upcoming heat standard. There are many more common settings: homes, schools and childcare facilities, transit, correctional facilities, and outdoor public spaces where regulations are needed. There will also need to be expanded enforcement of the regulations, including better monitoring of temperatures outdoors and indoors. HUD, EPA, and NOAA should work to identify expansion opportunities to indoor and outdoor air temperature monitoring, seeking additional funding from Congress where needed

Future regulations for mitigating extreme heat exposure can be conceptualized in the following three ways: technology standards, the required presence of a cooling and/or thermal-regulating technology, behavioral guidelines and expectations, required actions to avert overexposure, and performance standards, requirements that heat exposure cannot cross a certain threshold. These potential regulations will need to be conceptualized, reviewed, and implemented by several federal agencies, as authority for different aspects of heat exposure is fragmented across the federal government. Some examples of regulatory levers identified through our interviews (and introduced in previous sections) include:

- HUD could have standards for building performance that includes thermal comfort and safety, for its properties, backed-mortgages, and public housing it supports, as well as requirements for reducing building waste heat.

- DOE could expand its performance assessment and certification of energy efficiency products to those that also enhance thermal comfort and resilience.

- FEMA could require individuals, local governments, and state governments to do mitigation planning for extreme heat, and make resources then available to build community-scale thermal resilience.

- DOT could implement requirements for infrastructure projects to not increase urban areas UHI effects.

- EPA could further its analysis of the compounding effects of hot air and air pollution, and consider hotter air temperatures (such as those in UHIs) a risk to guaranteeing clean air.

- The Administration for Strategic Planning and Response (ASPR) could require hospital planning for surges in heat illness during heat waves to receive Hospital Preparedness Program funding.

Conclusion

Extreme heat, both acute and chronic, is a growing threat to American livelihoods, affecting household incomes, students’ learning, worker safety, food security, and health and wellbeing. While the policy landscape for addressing heat is nascent, this report offers recommendations for near and long term solutions that policymakers can consider. Complimentary to FAS’ Extreme Heat Policy Sprint, we hope this report can be a toolkit for potential realistic actions.

22 Organizations Urge Department of Education to Protect Students from Extreme Heat at Schools

Twenty-two organizations and 29 individuals from across 12 states sent a letter calling on the U.S. Department of Education to take urgent action to protect students from the dangers of extreme heat on school campuses

WASHINGTON — With meteorologists predicting a potentially record-breaking hot summer ahead, a coalition of 22 organizations from across 12 states is urgently calling on the Department of Education to use its national platform and coordinating capabilities to help schools prepare for and respond to extreme heat. In a coalition letter sent today, spearheaded by the Federation of American Scientists and UndauntedK12, the groups recommend streamlining funding, enhancing research and data, and integrating heat resilience throughout education policies.

“The heat we’re experiencing today will only get worse. Our nation’s classrooms and campuses were not built to withstand this heat, and students are paying the price when we do not invest in adequate protections. Addressing extreme heat is essential to the Department of Education’s mission of equitable access to healthy, safe, sustainable, 21st century learning environments” says Grace Wickerson, Health Equity Policy Manager at the Federation of American Scientists, who recently authored a policy memo on addressing heat in schools.

Many schools across the country – especially in communities of color – have aging infrastructure that is unfit for the heat. This infrastructure gap exposes millions of students to temperatures where it’s impossible to learn and unhealthy even to exist. Despite the rapidly growing threat of extreme heat fueled by climate change, no national guidance, research and data programs, or dedicated funding source exists to support U.S. schools in adapting to the heat.

“Many of our nation’s school campuses were designed for a different era – they are simply not equipped to keep children safe and learning with the increasing number of 90 and 100 degree days we are now experiencing due to climate change. Our coalition letter outlines common sense steps the Department of Education can take right now to move the needle on this issue, which is particularly pressing in schools serving communities of color. All students deserve access to healthy and climate-resilient classrooms,” said Jonathan Klein, co-founder and CEO of UndauntedK12.

The coalition’s recommendations include:

- Publish guidance on school heat readiness, heat planning best practices, model programs and artifacts, and strategies to build resilience (such as nature-based solutions) in partnership with the Environmental Protection Agency, Federal Emergency Management Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, NIHHIS, and subject-area expert partners.

- Join the Extreme Heat Interagency Working Group led by the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS).

- Use ED’s platform to encourage states to direct funding resources for schools to implement targeted heat mitigation and increase awareness of existing funds (i.e. from the Inflation Reduction Act and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law) that can be leveraged for heat resilience. Further Ed and the IRS should work together to understand the financing gap between tax credits coverage and true cost for HVAC upgrades in America’s schools.

- Direct research and development funding through the National Center for Educational Statistics and Institute for Education Sciences toward establishing regionally-relevant indoor temperature standards for schools to guide decision making based on rigorous assessments of impacts on children’s health and learning.

- Adapt existing federal mapping tools, like the NCES’ American Community Survey Education Tabulation Maps and NIHHIS’ Extreme Heat Vulnerability Mapping Tool, to provide school district-relevant information on heat and other climate hazards. As an example, NCES just did a School Pulse Panel on school infrastructure and could in future iterations collect data on HVAC coverage and capacity to complete upgrades.

- Evaluate existing priorities and regulatory authority to identify ways that ED can incorporate heat readiness into programs and gaps that would require new statutory authority.

The Federation of American Scientists and UndauntedK12 and our partner organizations welcome the opportunity to meet with the Department of Education to discuss these recommendations and to provide support in developing much needed guidance as we enter another season of unprecedented heat.

###

About UndauntedK12

UndauntedK12 is a nonprofit organization with a mission to support America’s K-12 public schools to make an equitable transition to zero carbon emissions while preparing youth to build a sustainable future in a rapidly changing climate.

About Federation of American Scientists

FAS envisions a world where cutting-edge science, technology, ideas and talent are deployed to solve the biggest challenges of our time. We embed science, technology, innovation, and experience into government and public discourse in order to build a healthy, safe, prosperous and equitable society.

Heat Hazards and Migrant Rights: Protecting Agricultural Workers in a Changing Climate

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Urgent Heat Risks: Climate change is leading to more frequent and intense heat waves, increasing the urgency for comprehensive heat safety regulations for agricultural workers.

- Vulnerable Migrant Workers: Migrant workers face heightened risks due to low wages, inadequate healthcare, and precarious working conditions. Fear of retaliation and deportation often prevents them from reporting violations.

- Economic Impact: Lack of heat safety measures endangers workers & results in significant economic costs, including lost productivity. Employers who fail to implement heat safety measures face high costs to their businesses, while investing in worker safety can yield substantial economic benefits.

- Regulatory Progress & Challenges: OSHA is developing federal heat safety regulations, with states like California and Oregon setting effective precedents. As efforts advance, the focus must shift to ensure equitable protection, particularly vulnerable groups like migrant laborers. Inclusive engagement and tailored implementation strategies are crucial to bridge gaps and create effective protections.

- Community & Stakeholder Engagement: True progress in regulation requires the active involvement of all stakeholders, including workers, employers, advocacy groups and industry leaders. Transitioning to more inclusive & direct engagement methods are essential for comprehensive worker protection.

KEY FACTS

- Farmworkers are 20x more likely to die from heat than other workers

- Heat exposure is responsible for as many as 2,000 worker fatalities in the U.S. each year

- Up to 170,000 workers in the U.S. are injured in heat stress related accidents annually. There is a 1% increase in workplace injuries for every increase of 1° Celsius

- The failure of employers to implement simple heat safety measures costs the U.S. economy nearly $100 billion every year

In 2008, Maria Isabel Vasquez Jimenez, a 17-year-old pregnant farmworker, tragically died from heatstroke while working in the vineyards of California. Despite laboring for more than nine hours in the sweltering heat, Maria was denied access to shade and adequate water breaks. Management never called 911 and instructed her fiancé to lie about the events. To this day, her death underscores the dire need for robust protections for those who endure extreme conditions to feed our nation.

This heartbreaking incident is not isolated. With the United States shattering over a thousand temperature records last year, the crisis of heat-related illnesses in the agricultural sector is intensifying. Rising global temperatures are making heat waves more frequent and severe, posing a significant threat to farmworkers who are essential to our food supply. While progress is being made towards comprehensive heat safety regulations, we must now focus on ensuring these protections are equitably implemented to safeguard all farmworkers from the intensifying threats of climate change, especially vulnerable groups like migrants. As individual stories shed light on the real-life tragedies of neglecting climate resilience, broader climate trends reveal a significant rise in these risks, affecting agricultural workers nationwide.

Climate change & agriculture

Rising Temperatures

Climate change poses significant challenges to global agricultural systems, threatening food security, livelihoods, and the overall sustainability of farming practices. Among the various climate-related hazards, rising temperatures stand out as a primary concern for agricultural productivity and worker health and safety. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) reports that the average temperature in the United States has increased by 1.8°F over the past century, with the most significant increases occurring in the last few decades. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, global average temperatures have been steadily increasing due to the accumulation of greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere, primarily from human activities such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation. This warming trend is expected to continue, critically impacting agricultural operations worldwide. The Union of Concerned Scientists predicts that by mid-century, the average number of days with a heat index above 100°F in the United States will more than double, severely impacting agricultural productivity and worker health. As the climate continues to change, the direct threats to those who supply our food become increasingly severe, particularly for farmworkers exposed to the elements.

Threats to Farmworkers

In agriculture, rising temperatures worsen challenges like water scarcity, soil degradation, and pest infestations, and introduce new risks like heat stress for farmworkers. As temperatures rise, heatwaves become more frequent, intense, and prolonged, posing serious threats to the health and well-being of agricultural workers who perform physically demanding tasks outdoors. Heat stress can lead to heat-related illnesses such as heat exhaustion and heatstroke, which can be life-threatening if not properly managed. Prolonged exposure to high temperatures can impair cognitive function, reduce productivity, and increase the risk of accidents and injuries in the workplace. According to the Public Citizen, from 2000 to 2010, as many as 2,000 workers died each year from heat-related causes in the United States, while farmworkers are 20 times more likely to die from heat-related illnesses than other workers.

Given the critical role of agricultural workers in food production and supply chains, protecting their health and safety in the face of escalating heat risks is critical. Comprehensive heat safety standards and regulations are essential to mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change on farmworkers and ensure the sustainability and resilience of agricultural operations. By implementing comprehensive heat safety measures such as heat acclimatization guidelines, shade access, and regular rest breaks, agricultural employers can minimize the risk of heat-related illnesses and injuries. Effective heat standard implementation requires collaboration among policymakers, industry stakeholders, and worker advocacy groups to address climate change challenges and protect agricultural workers. Beyond the direct effects of heat, farmworkers also face compounded environmental hazards that further jeopardize their health and safety.

Compounded Hazards

While the focus of this discussion is on heat safety regulations, it’s important to recognize that these regulations intersect with broader environmental and health challenges faced by agricultural workers. High temperatures often coincide with wildfire seasons, leading to increased exposure to wildfire smoke. This overlap amplifies health risks like respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, disproportionately affecting workers with vulnerable conditions. Effective protection against these compounded hazards requires coordination among policymakers and industry leaders. Comprehensive standards and holistic safety measures are crucial to mitigate the risks associated with heat and to address the broader spectrum of environmental pollutants. While environmental hazards are a significant concern, the specific vulnerabilities of migrant workers introduce additional layers of risk and complexity.

Challenges faced by migrant workers

Recognizing these challenges is only the first step; next, we must assess how current protections measure up and where they fall short in safeguarding these vulnerable populations.

Understanding the Vulnerabilities

Migrant agricultural workers face socioeconomic, legal, and environmental challenges that increase their vulnerability to heat hazards. Economically, many migrant workers endure low wages and lack access to adequate healthcare, which complicates their ability to cope with and recover from heat-related illnesses. A study by the National Center for Farmworker Health found that 85% of migrant workers earn less than the federal poverty level, making it difficult for them to access necessary medical care. Legally, the fragile status of many migrant workers, including those on temporary visas or without documentation, exacerbates their vulnerability. These workers often hesitate to report violations or seek help due to fear of retaliation, job loss, or deportation.

Harsh Working Conditions

Additionally, migrant workers frequently labor in conditions that provide minimal protection against the elements. Excessive heat exposure is compounded by inadequate access to water, shade, and breaks, making outdoor work particularly dangerous during heatwaves. Furthermore, many migrant workers return after work to substandard housing that lacks essential cooling or ventilation, preventing effective recovery from daily heat exposure and exacerbating dehydration and heat-related health risks. According to the National Center for Farmworker Health, about 40% of migrant farmworkers in the United States live in homes without air conditioning.

Barriers to Protection

The barriers to effective heat protection for migrant workers are extensive and complex, which may prevent them from accessing crucial protections and resources, including:

Language Diversity. The migrant worker community is incredibly diverse, encompassing individuals from various cultural and linguistic backgrounds. In the U.S. agricultural sector, over 50% of workers report limited English proficiency. This diversity may present a significant challenge to understand their rights and the safety measures available to them. Even when regulations and protections are in place, the communication of these policies often fails to reach non-English speaking workers effectively, leading to misunderstandings that can prevent them from advocating for their safety and well-being. The National Agricultural Workers Survey reports that 77% of farmworkers in the United States are foreign-born, with 68% primarily speaking Spanish, highlighting the language barriers that complicate effective communication of safety regulations.

Vulnerable Visas & Immigration Status. Visa statuses and undocumented immigration also play a critical role in the vulnerability of migrant workers. Workers holding temporary visas, such as H-2A visas, often face precarious employment conditions because these visas tie them to specific employers, limiting their ability to assert their rights without fear of retaliation. Undocumented workers are particularly susceptible to exploitation and abuse by employers who may use their immigration status as leverage. Fear of deportation and legal repercussions further discourages reporting workplace incidents, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation and vulnerability.

Undocumented workers are particularly susceptible to exploitation and abuse by employers who may use their immigration status as leverage

Farmworker Housing. Farmworker housing often lacks proper cooling or ventilation, increasing heat exposure risks during off-work hours. Many agricultural workers live in substandard housing characterized by overcrowding, poor insulation, and inadequate access to air conditioning or ventilation systems. Poor living conditions worsen heat-related illnesses, particularly during extreme weather. Limited access to cooling amenities after long hours of outdoor labor exacerbates heat stress and heightens the health risks associated with heat exposure.

Recognizing these challenges is only the first step; next, we must assess how current protections measure up and where they fall short in safeguarding these vulnerable populations.

Review of existing protections

Federal Efforts

Currently, there is no overarching federal mandate specifically addressing heat exposure, leaving significant gaps in worker protection, especially for vulnerable populations like migrant workers. However, the federal government has taken several critical steps to address heat safety in the interim. OSHA has moved beyond relying solely on the General Duty Clause, launching a National Emphasis Program that prioritizes inspections on high-heat days and increases outreach in vulnerable industries. The Biden administration’s Heat Hazard Alert in July 2023 further emphasized employers’ responsibilities, while the initiation of a federal heat standard through OSHA’s rulemaking process signals a commitment to sweeping, nationwide protections.

These efforts reflect progress but it’s crucial that these federal efforts evolve to address the unique challenges faced by workers, ensuring that no one is left behind in the implementation of heat safety measures. The true test of these regulations will be their ability to safeguard those most at risk, bridging gaps in protection and creating a more resilient workforce in the face of rising temperatures.

State-Level Protections

At the state level, the scenario is mixed, with states like California, Washington, and Oregon having implemented their own heat safety regulations, which provide a model for other states and potentially for federal standards. Oregon’s regulations, for instance, require employers to provide drinking water, access to shade, and adequate rest periods during high heat conditions. These measures are designed not just to respond to the immediate needs of workers but also to educate them on the risks of heat exposure and the importance of self-care in high temperatures. When Oregon implemented stricter heat safety standards, it saw a significant reduction in heat-related illnesses reported among agricultural workers. By requiring more frequent breaks, adequate hydration, and access to shade, Oregon’s regulations demonstrate how well-designed policies can decrease the incidence of heat stress and related medical emergencies. California has also taken a comprehensive approach with its Heat Illness Prevention Program, which extends protections to both outdoor and indoor workers, reflecting the broad scope of heat hazards. This program is noted for its requirements, including training programs that educate workers on preventing heat illness, emergency response strategies, and the necessity of acclimatization.

Legislative Challenges & Need for Unified Approach

Conversely, legislative actions in states like Florida and Texas represent a significant challenge to advancements in occupational heat safety. For example, Florida’s HB 433, recently signed into law, expressly prohibits local governments from enacting regulations that would mandate workplace protections against heat exposure. This legislation stalls progress and endangers workers by blocking local standards tailored to the state’s specific needs.

The contradiction between states pushing for more stringent protections and those opposing regulatory measures illustrates a fragmented approach that could undermine worker safety nationwide. Without a federal standard, the protection a worker receives is largely dependent on state policies, which may not adequately address the specific risks associated with heat exposure in increasingly hot climates. This patchwork of regulations underscores the importance of a unified federal standard that could provide consistent and enforceable protections across all states, ensuring that no worker, regardless of geographical location, is left vulnerable to the dangers of heat exposure.

With an understanding of the gaps in current heat safety regulations, the next crucial step is fostering effective stakeholder engagement to drive meaningful changes.

Engaging Stakeholders: Beyond Public Comment

While progress has been made in recognizing the need for heat safety regulations, we must now focus on ensuring equitable representation in the policy-making process. Traditional engagement methods have often fallen short in capturing the voices of those most impacted by these policies, particularly vulnerable groups like migrant agricultural workers. Regulatory agencies must rethink their strategies to include more direct and inclusive approaches, empowering workers to contribute meaningfully to policies that directly affect their safety and well-being.

Challenges in Traditional Engagement

The traditional approaches to stakeholder engagement, particularly in regulatory settings, often rely heavily on formal mechanisms like public comment periods. While these methods are structured to gather feedback, they frequently fall short of engaging those most impacted by the policies—namely, the workers themselves. Many workers, especially in labor-intensive sectors like agriculture, may not have the time, resources, or knowledge to participate in these processes. Relying on online submissions or weekday meetings during work hours can exclude many workers whose insights are crucial for shaping effective regulations. A survey conducted by the Migrant Clinicians Network found that fewer than 10% of migrant workers had participated in any form of public comment or feedback process related to workplace safety.

The complexities of these workers’ lives—ranging from language barriers to fear of retaliation—mean that conventional engagement strategies may not effectively reach or address their concerns. This gap highlights a critical need for regulatory bodies to rethink and expand their engagement strategies to include more direct and inclusive methods.