Save Lives by Making Smoke Tracking a Core Part of Wildland Fire Management

Toxic smoke from wildland fire spreads far beyond fire-prone areas, killing many times more people than the flames themselves and disrupting the lives of tens of millions of people nationwide. Data infrastructure critical for identifying and minimizing these smoke-related hazards is largely absent from our wildland fire management toolbox.

Congress and executive branch agencies can and should act to better leverage existing smoke data in the context of wildland fire management and to fill crucial data infrastructure gaps. Such actions will enable smoke management to become a core part of wildland fire management strategy, thereby saving lives.

Challenge and Opportunity

The 2023 National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy Addendum describes a vision for the future: “To safely and effectively extinguish fire, when needed; use fire where allowable; manage our natural resources; and collectively, learn to live with wildland fire.” Significant research conducted since the publication of the original Strategy in 2014 indicates that wildfire smoke impacts people across the United States, causing thousands of deaths and billions of dollars of economic losses annually.

Smoke impacts exceed their corresponding flame impacts and span far greater areas coast to coast. However, wildfire strategy and funding largely focus on flames and their impacts. Smoke mitigation and management should be a high priority for federal agencies considering the 1:1 ratio of economic impacts and 1:30 ratio of fire to smoke deaths.

Some smoke data is already collected, but these datasets can be made more actionable for health considerations and better integrated with other fire-impact data to mitigate risks and save more lives.

Smoke tracking

Several federal programs exist to track wildfire smoke nationwide, but there are gaps in their utility as actionable intelligence for health. For example, the recent “smoke wave” on the East Coast highlighted some of the difficulties with public warning systems.

Existing wildfire-smoke monitoring and forecast programs include:

- The Fire and Smoke Map, collaboratively managed by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the US Forest Service, which displays real-time air-quality data but is limited to locations with sensors;

- The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Hazard Mapping System Fire and Smoke Product, which evaluates total-atmosphere smoke, but lacks ground-level estimates of what people would breathe; and

- The Interagency Wildland Fire Air Quality Response Program (IWFAQRP) and the experimental U.S. Forest Service (USFS) BlueSky Daily Runs, which integrate external data to make forecasts, but lack location-specific data for all potentially impacted locations.

The EPA also publishes retrospective smoke emissions totals in the National Emissions Inventory (NEI), but these lack specificity on the downwind locations impacted by the smoke that would be needed to be used for health considerations.

Existing data are excellent, but scientists using the data combine them in non-standardized ways, making interoperability of results difficult. New nationwide authoritative smoke-data tools need to be created—likely by linking existing data and existing methods—and integrated into core wildland fire strategy to save lives.

Smoke health impacts

There is no single, authoritative accounting of wildfire smoke impacts on human health for the public or policymakers to use. Four key gaps in smoke and health infrastructure may explain why such an accounting doesn’t yet exist.

- The U.S. lacks a standardized method for quantifying the health impacts of wildfire smoke, especially mortality, despite recent research progress in this area.

- The lack of a national smoke concentration dataset hinders national studies of smoke-health impacts because different studies take different approaches.

- Access to mortality data through the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS), managed by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), is slow and difficult for the scientists who seek to use mortality data in epidemiological studies of wildfire smoke.

- Gaps remain in understanding the relative harm of wildfire smoke, which can contain aerosolized hazardous compounds from burned infrastructure, compared to the general air pollution (e.g., from cars and factories) that is often used as analog in health research.

Addressing these gaps together will enable official wildfire-smoke-attributable death tolls to be publicized and used by decision-makers.

Integration of wildfire smoke into wildland fire management strategy

Interagency collaborations currently set wildland fire management strategy. Three key groups with a mission to facilitate interagency collaboration are the National Interagency Fire Center (NIFC), the National Wildfire Coordinating Group (NWCG), and the Wildland Fire Leadership Council (WFLC). NIFC maintains datasets on wildfire impacts, including basic summary statistics like acres burned, but smoke data are not included in these datasets. Furthermore, while NWCG does have 1 of its 17 committees dedicated to smoke, and has collaborations that include NOAA (who oversees smoke tracking in the Hazard Mapping System), none of the major wildfire collaborations include agencies with expertise in measuring the impacts of smoke, such as the EPA or Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Finally, WFLC has added calls for furthering community smoke-readiness in the recent 2023 National Cohesive Wildland Fire Management Strategy Addendum, but greater emphasis on smoke is still needed. Better integration of smoke data, smoke-health data, and smoke-expert agencies will enable better consideration of smoke as part of national wildland fire management strategy.

Plan of Action

To make smoke management a core and actionable part of wildland fire management strategy, thereby saving lives, several interrelated actions should be taken.

To enhance decision tools individuals and jurisdictions can use to protect public health, Congress should take action to:

- Issue smoke wave alerts nationwide. Fund the National Weather Service (NWS) to develop and issue smoke wave alerts to communities via the Wireless Emergency Alerts (WEA) system, which is designed for extreme weather alerting. The NWS currently distributes smoke messages defined by state agencies through lower-level alert pathways, but should use the WEA system to increase how many people receive the alerts. Furthermore, a national program, rather than current state-level decisions, would ensure continuity nationwide so all communities have timely warning of potentially deadly smoke disasters. Alerts should follow best practices for alerting to concisely deliver information to a maximum audience, while avoiding alert fatigue.

- Create a nationwide smoke concentration dataset. Fund NOAA and/or EPA to create a data inventory of ground-level smoke PM2.5 concentrations by integrating air-monitor data and satellite data, using existing methods as needed. The proposed data stream would provide standardized estimates of smoke concentrations nationwide, and would be a critical precursor for estimating smoke mortality as well as the extent to which smoke is contributing to poor air quality in communities. This action would be enhanced by data from recommendation 4 (below).

- Create a smoke mortality dataset. Fund the CDC and/or EPA to create a nationwide data inventory of excess morbidity and mortality attributed to smoke from wildland fires. An additional enhancement would be to track the smoke health impacts contributed by each source wildfire. Findings should be disseminated in NIFC wildfire impact summaries. This action would be enhanced by data from recommendations 4-5 and research from recommendations 6-8 (below).

The decision-making tools in recommendations 1-3 can be created today based on existing data streams. They should be further enhanced as follows in recommendations 4-10:

To better track locations and concentrations of wildfire smoke, Congress should take action to:

- Install more air-quality sensors. Fund the EPA, which currently monitors ground-level air pollutants and co-oversees the Fire and Smoke Map with the USFS, to establish smoke-monitoring stations in each census tract across the U.S and in other locations as needed to provide all communities with real-time data on wildfire-smoke exposure.

- Create a smoke impact dashboard. The current EPA Fire and Smoke Map shows near-real-time data from regulatory-grade air monitors, commercial-grade air sensors, and satellite data of smoke plumes. An upgraded dashboard would combine that map with data from recommendations 1-3 to give current and historic information about ground-level air quality, the fraction of pollutants due to wildfire smoke, and the expected health impacts. It would also include short-term forecast data, which would be greatly improved with additional modeling capability to incorporate fire behavior and complex terrain.

To better track health impacts of wildfire smoke, Congress should take action to:

- Improve researcher access to mortality data. Specifically, direct the CDC to increase epidemiologist access to the National Vital Statistics System. This data system contains the best mortality data for the U.S., so enhancing access will enhance the scientific community’s ability to study the health impacts of wildfire smoke (recommendations 6-8).

- Establish wildfire-health research centers. Specifically, fund the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to establish flagship wildfire-smoke health-research centers to research the health effects of wildfire smoke. Results-dissemination pathways should include through the NIFC to reach a broad wildfire policy audience.

- Enhanced health-impact-analysis tools. Direct EPA to evaluate the available epidemiological literature to adopt standardized wildfire-specific concentration-response functions for use in estimating health impacts in their BenMAP-CE tool. Non-wildfire functions are currently used even in the research literature, despite potentially underestimating the health impacts of wildfire smoke.

To enhance wildland fire strategy by including smoke impacts, Congress should take action to:

- Hire interagency staff. Specifically, fund EPA and CDC to place staff at the main NIFC office and join the NIFC collaboration. This will facilitate collaboration between smoke-expert agencies with agencies focused on other aspects of wildfire.

Support landscape management research. Specifically, direct the USFS, CDC, and EPA to continue researching the public health impacts of different landscape management strategies (e.g., prescribed burns of different frequencies compared to full suppression). Significant existing research, including from the EPA, has investigated these links but still more is needed to better inform policy. Needed research will continue to link different landscape management strategies to probable smoke outputs in different regions, and link the smoke outputs to health impacts. Understanding the whole chain of linkages is crucial to landscape management decisions at the core of a resilient wildland fire management strategy.

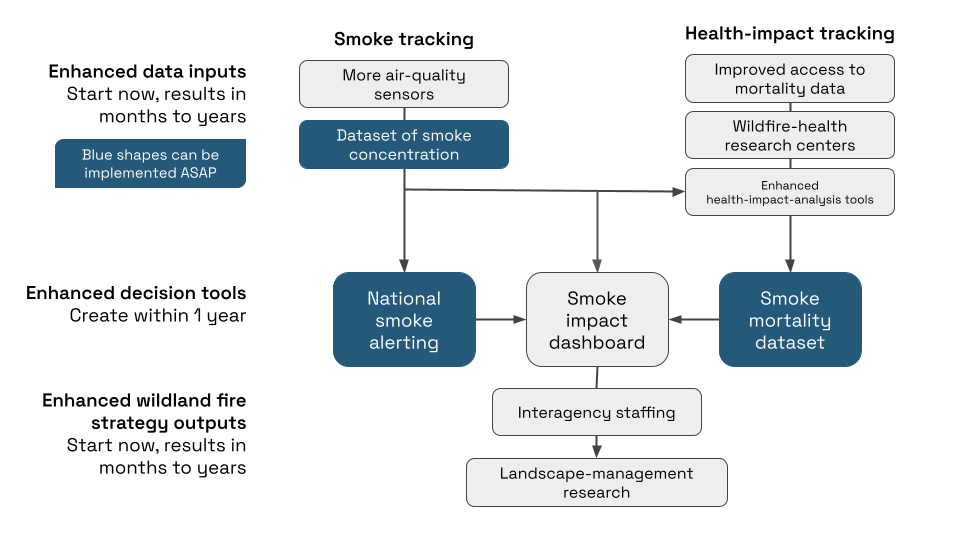

Diagram with arrows showing data flow from top to bottom, between the proposed infrastructure, with each shape representing one recommendation. Data flows from the data inputs (top boxes) to actionable tools for decision-making (circles), and finally on to pathways for integrating smoke into wildland fire management strategy (bottom boxes). The three blue shapes are recommendations that can be implemented immediately.

Cost estimates

This proposal is estimated to have a first-year cost of approximately $273 million, and future annual cost of $38 million once equipment is purchased. The total cost of the first year represents less than 4% of current annual wildfire spending (subsequent years would be 0.5% of annual spending), and it would lay the foundation to potentially save thousands of lives each year. Assumptions behind this estimate can be found in the FAQ.

Conclusion

In the U.S., more and more people are being exposed to wildfire smoke—27 times more people are experiencing extreme smoke days than a decade ago. The suggested programs are needed to improve the national technical ability to increase smoke-related safety, thereby saving lives and reducing smoke-related public health costs.

Recommendations 1-3 can be completed within approximately 6-12 months because they rely on existing technology. Recommendation 4 requires building physical infrastructure, so it should take 6 months to initiate and several years to complete. Recommendation 5 requires building digital infrastructure from existing tools, so it can be initiated immediately but relies on data from recommendations 2-3 to finalize. Recommendation 6 will require one year of personnel time to complete program review necessary for making changes, then will require ongoing support. Recommendation 7 establishes research centers, which will take 2 years to solicit and select proposals, then 5 years of funding after. Recommendation 8 requires a literature review and can be completed in 1 year. Recommendations 9-10 are ongoing projects that can start within the first year but then will require ongoing support to succeed.

The latest estimates indicate that thousands of people die across the United States each year due to wildfire smoke. However, there is no consistent ongoing tracking of smoke-attributable deaths and no centralized authoritative tallies.

Many deaths occur during the wildfire itself—wildfire smoke contains small particles (less than 2.5 microns, called PM2.5) that immediately increase the risk of stroke and heart attack. Additional deaths can occur after the fire, due to longer-term complications, much in the same way that smoking increases mortality.

Wildfires and wildfire smoke occur across the country, so deaths attributable to these causes do too. Recent research indicates that there are high numbers of deaths attributable to wildfire smoke on the West Coast, but also in Texas and New York, due to long-distance transportation of smoke and the high populations in those states.

One-time costs for recommendations 2, 3, and 8 were estimated in terms of person-years of effort and are additive with their annual costs in the first year. Recommendations 2-3 require a large team to create the initial datasets and then smaller teams to maintain, while recommendation 8 requires only an initial literature review and no maintenance. One person-year is estimated at $150,000 per year, including fringe benefits.

One-time costs for recommendation 4 were calculated in terms of air-quality monitor costs, with one commercial grade sensor ($400) for each of the 84,414 census tracts in the U.S., one sensor comparable to regulatory grade (estimated at $40,000) for each of the 5% most smoke-impacted census tracts, and 15% overhead costs for siting and installation.

Annual costs for recommendations 1-3, 5-6, and 9-10 were estimated in terms of person-years of effort because salary is the main consumable for these projects. One person-year is estimated at $150,000 per year, including fringe benefits.

Annual costs for recommendation 4 were estimated by assuming that 10% of sensors would need replacement per year. These funds can be passed on to jurisdictions, following current maintenance practice of air-quality monitors.

Annual costs for recommendation 7 is for four NIH Research Core Centers (P30 grant type) at their maximum amount of $2.5 million, each, per year.

In an environment where fire seasons are turning to fire years, and summer skies across North America are filled with wildfire smoke from as far away as another coast, the need for scientifically accurate wildland fire policy has never been greater. Over the past several months, COMPASS Science Communication has been working in collaboration with […]

The U.S. response to wildland fire can be better informed by science, evidence, and Indigenous perspectives.

The Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission called for input from diverse stakeholders and FAS, along with partners Conservation X Labs (CXL), COMPASS, and the California Council on Science and Technology (CCST), answered the call. Recruiting participants from academia, the private sector, national labs, and other nonprofits, the Wildland Fire Policy Accelerator produced 24 ideas […]

Over the past two years, the federal government has invested unprecedented amounts of funding in wildfire suppression, hazardous fuels reduction, community preparedness, and restoration through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). Together, the IIJA and IRA provide $24 billion in funding for wildfire issues, distributed over 40 different programs and administered […]