Soil and Water: Why We Need Conservation Agriculture

On May 1, 2023, a devastating dust storm – the result of severe wind erosion – propelled soil across highway I-55, causing numerous accidents, injuries, and loss of life. The factors that led to this erosion event were excessive tillage, exposed soils, and windy conditions. In response, the Journal of Soil and Water Conservation published an article proposing a “Soil Health Act,” to improve conservation agriculture policy.

Most erosion is a direct result of human activities, such as leaving the soil bare for extended periods and excessive tillage in agricultural fields. Extreme weather events exacerbate soil erosion, with large wind erosion events damaging crops and causing air pollution in nearby communities. Water erosion can strip productive topsoil from cropland, reducing crop productivity and depositing sediment in water bodies. The Fifth National Climate Assessment further confirms that extreme weather is on the rise.

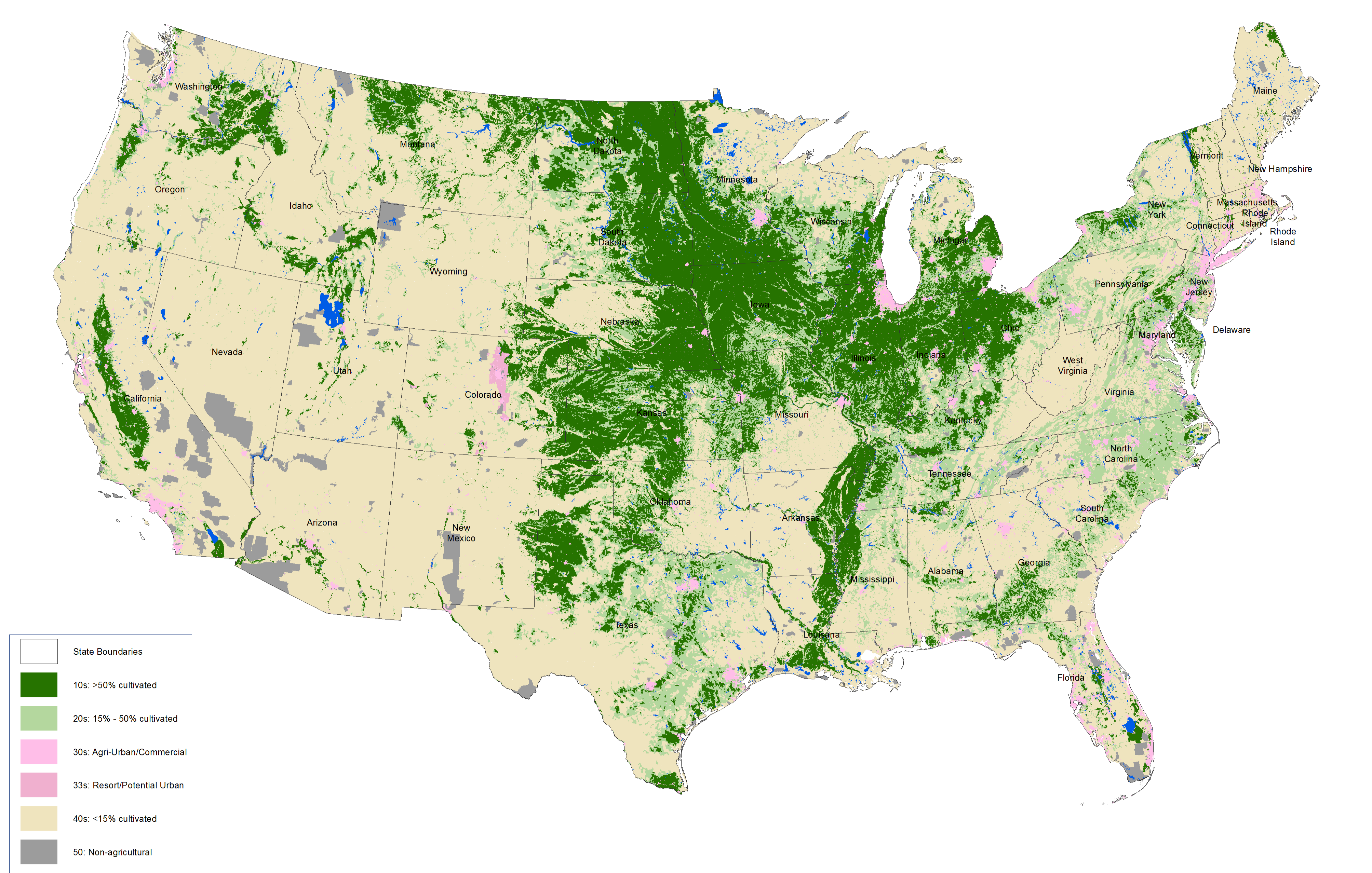

The United States boasts some of the most productive soils globally, particularly in the Midwest region, known as the corn belt. This vast expanse of farmland, which drains into the Mississippi River and eventually reaches the Gulf of Mexico, is a crucial part of our country’s agricultural landscape. However, this network of soil and water, while offering significant benefits, also poses significant challenges if not properly cared for.

Map of U.S. major agriculture cropland areas in dark green. These regions also have highly productive soils. The Midwest soils of Iowa, southern Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, southern Wisconsin, and Ohio are globally significant breadbasket soils. (Source: National Agricultural Statistics Service, 2017).

Wind erosion in the left photo is active in many regions of the country, leading to poor soil conditions for agricultural production. Water erosion takes productive topsoil and applied fertilizers and chemical products used off cropland as it heads toward streams. (Source: Jodie McVane (left) and Rodale Institute (right))

Fertilizers, herbicides, pesticides, and other products can enter water sources through two primary pathways: soil and chemical losses. Chemical losses can contaminate groundwater by moving down through the soil profile. Contaminated groundwater flows into private and public water supply wells , with many wells having high nitrate levels from commercial fertilizers and animal applications of manure. Nitrates can pose health risks to infants, cause toxic anemia, and how red blood cells deliver oxygen to the cells and tissues. In adults, reproductive health issues and certain cancers are also possible. And it’s not just nitrates: Atrazine, a common chemical used to control weeds, is found in many drinking wells across the U.S.

When soil erodes it takes nitrates, atrazine, and other contaminants away from land surfaces and into surface waterways, leading to water quality problems and soil sediment pollution. Many land managers try to avoid creating runoff, but agricultural practices leaving soils exposed with no plant residues and erosive storms make this a common occurrence. Soil erosion impacts can also be experienced as sedimentation and murky waters in recreational water bodies, roads covered with mud, and dirty snow covered with wind-blown soils, all of which affect everyday life and are undesirable for fish and plants. The lack of soil protection during the non-crop growing season in the U.S. has caused soil erosion and degradation of precious resources, diminishing the ability to grow food, fiber, and wood and provide clean water. Thus, erosion affects long-term production and economic viability for farms.

Protecting Our Soils Through Conservation Agriculture

Fortunately, we can find solutions through conservation agriculture–a system of farming practices, which includes cover crops and reduced tillage, that protects soil and prevents both soil and chemical losses. Growing plants year-round can address soil loss by keeping the soil covered with plants known as cover crops like corn, soybean, and cotton. Others, like grasses, legumes, and forbs can be grown for seasonal cover. Reduced tillage from cover crops can be beneficial in several different ways:

They control erosion, build healthy soils, and improve water quality. Cover crops planted during these periods can scavenge unused fertilizers from the previous crop and prevent nutrients from reaching surface and groundwater systems. Reducing tillage or switching to no-till cropping systems can also increase soil structure and aid in water infiltration, helping water get into the soil instead of running off.

When soils have many soil organisms with a favorable habitat, they can break down chemical pollutants effectively before reaching groundwater. Cover crops can also play a vital role in absorbing nitrates or other contaminants. Studies have shown that cover crops can reduce nitrates by 48% before they reach subsurface waters. Reduced tillage can provide habitats for these organisms by reducing soil disturbance.

Cover crops capture sunlight and use plants’ photosynthetic processes to capture carbon in plant shoots and root systems. Much carbon is stored in our soils through plant roots. When the plants die, their roots remain in the soil, keeping the carbon sequestered. Excessive tillage breaks soil structure and releases carbon. Reduced tillage and no-till cropping systems allow soils to better maintain their carbon content.

Diverse cover crop species can be mixed, which leads to the diversification of plant roots and above-ground biomass. Furthermore, diversity above ground also means diversity below ground for soil organisms. Grasses can also be utilized alone to effectively suppress weeds and protect against erosion. Cover crops can capture carbon and increase carbon storage in soils, so planting cover crops yearly is important. (Source: Jodie McVane)

Federal and State Government Incentives to Expand Conservation Agricultural Practices

Overall, cover crop use is low in the United States and varies depending on established social norms, soils, climate, primary crops, outreach programs, and conservation technical assistance. According to the USDA Economic Research Service, cover crop use increased from 3.4% of U.S. cropland in 2012 to 5.1% in 2017. The increase is positive, but millions of cropland acres can still benefit from applying cover crops and reduced tillage. While the use of conservation agriculture is an individual land manager’s choice and overall cover crop remains low, the USDA report notes that there has been some progress and positive trends. Continued incentives from both federal and state governments will be crucial to encourage wide adoption of conservation agricultural practices.

Many USDA programs provide cost-sharing incentives to farmers who voluntarily encourage using cover crops, reducing tillage, planting grasslands, and diversifying crop rotations. The Farm Bill provides funding to assist farmers through the USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS) programs, such as the Environmental Quality Incentive Program (EQIP) and the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP). In addition to the Farm Bill, the Inflation Reduction Act provided additional funds to USDA-NRCS through these same programs to promote Climate Smart Agriculture and Forestry Mitigation activities. The Inflation Reduction Act makes nearly $20 billion additional dollars available over five years for these programs. Current federal policy allows these programs to fund conservation practices for 3-5 years on a typical farm. Some states are also leading in incentivizing land managers to apply cover crops. States providing monetary incentives include Maryland, Iowa, Missouri, Indiana, Ohio, and Virginia.

A mix of cover crops of grasses and broadleaves in the fall after a corn crop in the Midwest. (left photo) A cereal ryegrass cover crop holds the soil in place with fibrous root systems and protects the soil surface from water or wind erosion while suppressing weeds. (right photo) (Source: Jodie McVane)

Current Gaps and Proposed Policies

We will need lasting policies and sustainable funding to ensure the long-term adoption of conservation agricultural practices. Current voluntary conservation programs only provide funding for a 5-year period, which does not guarantee that farmers will permanently transition to conservation agriculture practices.

The federal government should incentivize the adoption of soil health practices and conservation agriculture widely across the United States in three ways:

Fund organizations that can provide educational events for farmers, consultants, policy groups, and consumers. These organizations are valuable and promote farmer-led education and peer-to-peer mentoring. Farmers enjoy learning from other farmers along with research experts.

Reward farmers who adopt conservation agriculture systems by providing long-term payments for continued use of conservation practices. Farmers who adopt these practices would benefit from their ecosystem services, such as building soil carbon, improving water quality, maintaining stable soil structure, and increasing water infiltration, which could significantly impact the health of our cropland acres.

Provide a reduction-based premium discount in the Federal Crop Insurance program for agricultural commodity producers that use risk-reduction farming practices, including cover crops. A discount on the insurance premium can have a lasting effect and provide a continued financial incentive to perform conservation on farms.

Soil is the foundation of our national health, providing food, homes, fibers, and the structural foundations for everyday life. Soils filter water for clean drinking, safe fishing, and other recreational activities, enabling our farms, factories, homes, schools, universities, and state and federal governments to access clean water; the widespread adoption of conservation agricultural practices to protect soils is key to ensuring food security for current and future generations in the United States. Healthy soils can protect not only our national treasure but also our national security and ability to care for our citizens.

As President Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “The nation that destroys its soil destroys itself.” Imagine driving around the country and seeing continuous vegetation growing, protecting soils, capturing carbon, and protecting our water resources. It would be a different landscape in our nation and, over the years, could improve the culture of agriculture.

The Federation of American Scientists values diversity of thought and believes that a range of perspectives — informed by evidence — is essential for discourse on scientific and societal issues. Contributors allow us to foster a broader and more inclusive conversation. We encourage constructive discussion around the topics we care about.

Global episodes of extreme heat intensify water shortages caused by extended drought and overpumping. Creating actionable solutions to the challenges of a warming planet requires cooperation across all water consumers.

The federal government should create a Reduce, Repurpose, Recharge Initiative (RRRI): a voluntary program designed to keep farmers engaged in groundwater conservation in the Ogallala Aquifer.

The Biden Administration should announce its intention to achieve net-zero soil loss by 2050. Here’s how they can do it.

The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) should prioritize funding water projects for local governments that would expand the production of new housing in their service areas if given the water resources to do so.