The Pentagon’s Annual Report on Chinese Military

[Updated August 21, 2018] The Pentagon’s annual report to Congress on China’s military and security developments has finally been published, several months later than previous volumes. Normally it takes about one month after the report is generated to be published. This year it took three times that long.

The report covers many aspects of Chinese military developments. In this article I’ll briefly review the nuclear weapons related aspects of the report.

Overall, nuclear developments are not what stand out in this report. Although there are important nuclear developments, the Pentagon’s primary concern is clearly about China’s conventional forces.

Nuclear Policy and Strategy

The DOD report repeats the conclusion from previous reports that China has not, despite writings by some PLA officers (and occasional speculations by outside analysts), changed its nuclear policy but retains a no-first-use (NFU) policy and a pledge not to use nuclear weapons against any non-nuclear weapon state or in nuclear-weapon-free zones. That would, strictly speaking, include Japan, even though it hosts large numbers of U.S. forces.

The NFU policy, DOD says, has “contributed to the construction of [underground facilities] for the country’s nuclear forces, which plan to survive an initial nuclear strike.” Stimulants for the tunneling efforts were the 1991 Gulf War and 1999 Kosovo war, which made the Chinese realize how vulnerable their forces would be in a war with the United States.

Nor does the report indicate China has yet mated nuclear warheads to its missiles or placed nuclear forces on alert under normal circumstances. The report repeats the assessment from last that “China is enhancing peacetime readiness levels for these nuclear forces to ensure responsiveness.” That responsiveness is thought to ensure the force can disperse and go on alert if necessary.

The report mentions unidentified PLA writings expressing the value of a “launch on warning” nuclear posture, but it does not say China has adopted such a posture. A launch on warning posture would require high readiness of nuclear forces to be able to launch as soon as a warning of an incoming nuclear attack was received. China already has a “ready the forces on warning” posture that involves gradually raising the readiness level in response to growing tension in a crisis.

In U.S. military terminology, “launch on warning” is a higher readiness level than “launch under attack” because it would involve being able to launch upon detection that an attack was imminent but before incoming missiles had been detected. “Launch under attack,” in contrast, would require the force to be able to launch before incoming warheads hit U.S. launchers. The DOD report says the PLA writings highlight the “launch on warning” posture would be consistent with China’s no-first-use policy, which would imply it is more compatible with a “launch under attack” posture.

The DOD report also continues to describe China’s work on MIRV, the capability to equip missile with multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles. Rather than a sign of an emerging counterforce strategy, however, DOD states that the purpose of the Chinese MIRV program is to “ensure the viability of its strategic deterrent in the face of continued advances in U.S. and, to a lesser extent, Russian strategic ISR, precision strike, and missile defense capabilities.”

Indeed, the counterproductive effects of U.S. ballistic missile defenses on Chinese offensive force developments is clearly spelled out in the report: “The PLA is developing a range of technologies China perceives are necessary to counter U.S. and other countries’ ballistic missile defense systems, including MaRV, MIRVs, decoys, chaff, jamming, thermal shielding, and hypersonic glide vehicles.”

The growing inventory of ICBMs and SSBNs means that China has to improve nuclear command and control of these systems for them to be effective. It is unknown if Chinese SSBNs have yet sailed on a deterrent patrol (we assume not), much less with nuclear warheads onboard (we also assume not). But the growing and increasingly mobile ICBM force is carrying out extensive combat patrol exercises that place new demands on the nuclear command and control system.

A unique feature of the Chinese missile force is the mixing of nuclear and conventional versions of the same missiles (DF-21 and DF-26 have both nuclear and conventional roles). For China, this is a means to provide the leadership with non-nuclear strike options without having to resort to nuclear use. For China’s potential adversaries, it is a dangerous and destabilizing practice that risks causing confusion about the character of missile attacks and potentially trigger mistaken nuclear escalation in a conflict.

China has, like other nuclear-armed states, lowered the yield of its nuclear warheads as ballistic missiles became more accurate. The current warhead used on the DF-31/A ICBMs is thought to be ten times less powerful than the multi-megaton warhead developed for the DF-5. Moreover, as China seeks to ensure the survivability of its warheads against missile defense systems, it is likely to continue to try to reduce the weight and size of its warheads to maximize penetration aids on the missiles.

The DOD report mentions a “defense industry publication has also discussed the development of a new low-yield nuclear weapon,” but does not provide any details about the publication or what it said. The classified version apparently has more details.

The Land-Based Missile Force

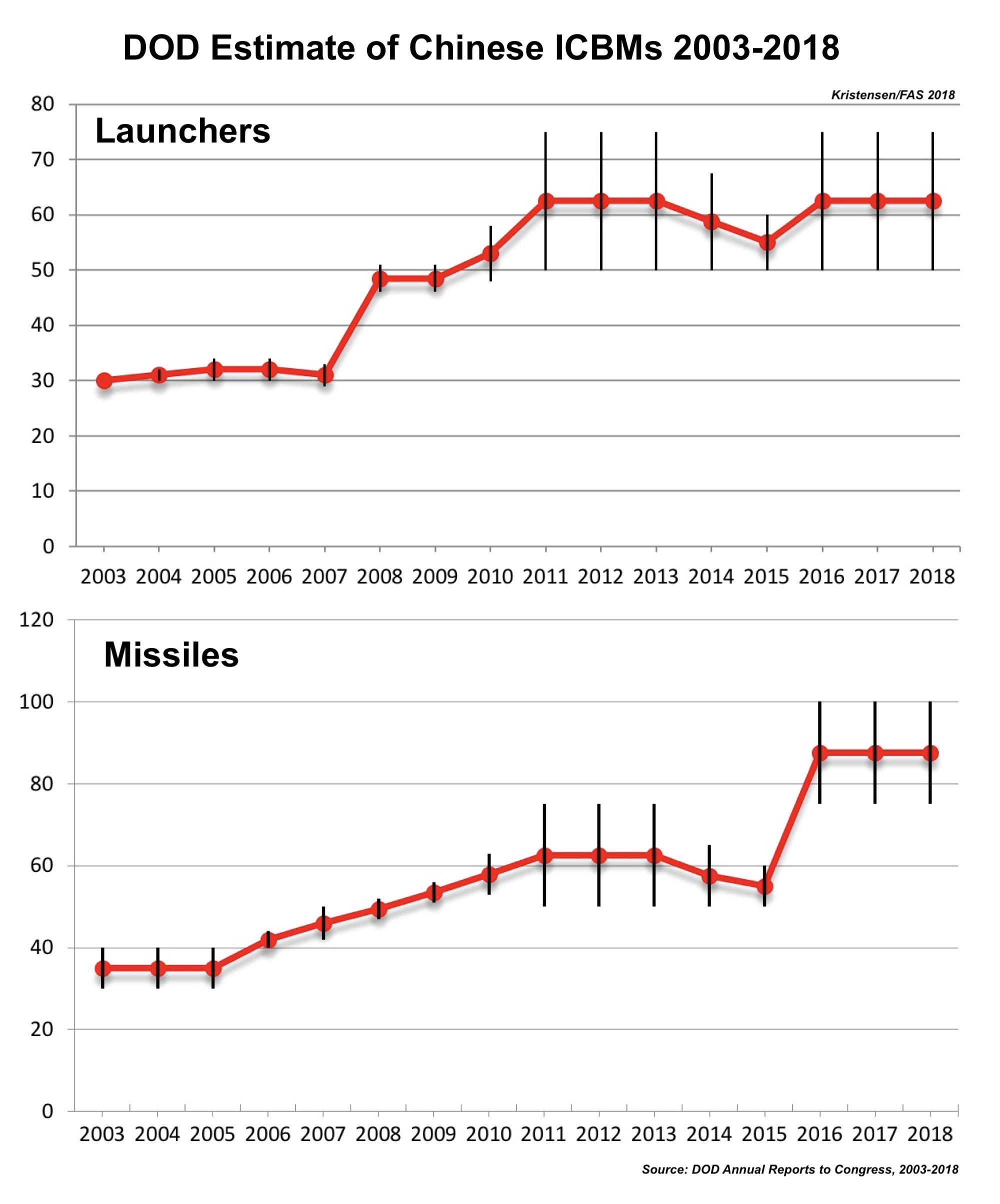

The overall number of Chinese ICBM launchers reported by DOD has remained stable since 2011: 50-75. One type (DF-4) has reload capability, so the number of available missiles is a little higher: 75-100 missiles. That number has also remained stable for the past three years. Indeed, other than the arrival of the DF-26 IRBM force, the total Chinese rocket forces estimate is identical to that of presented in the 2017 report.

This indicates that the DF-31A force is not continuing to increase, that the DF-31AG has not yet been operationally deployed (or is replacing older DF-31s on a one-for-one basis), and that the DF-41 is still in development more than 20 years after it was first listed in the annual DOD report.

DOD’s reporting shows that the number of Chinese ICBM launchers has roughly doubled since 2003, while the number of missile available for those launchers has more than doubled. The numbers of missiles show a mysterious increase in 2016 from just over 40 to more than 80 (see table below). The increase is curious because it does not follow the number of launchers but suddenly jumps even though there was no corresponding increase in launchers that year.

The DF-4 is thought to have reloads but that system has been deployed since the 1980s. There is considerable uncertainty in the number of launchers (some years 25). The increase coincides with the deployment of the MIRVed DF-5Bs, so a potential explanation might be that there are two full sets of DF-5 versions. But it should be underscored that it is unknown if this is the reason.

The old liquid-fuel DF-4 (CSS-3) ICBM is still listed as operational, even though the relocatable missile will probably be replaced by more survivable road-mobile missiles in the near future. The DF-4 appears to be retained in a roll-out-to-launch posture.

The old, but updated, liquid-fuel, silo-based DF-5 ICBM is still listed in two version: the single-warhead DF-5A and the MIRVed DF-5B. This missile was first deployed in the early-1980s and is based in 20 silos in the eastern part of central China. There is no mentioning of a rumored C version.

The DF-31 and DF-31A are the most modern operational ICBMs in the Chinese inventory. First fielded in 2006 and 2007, respectively, deployment of the DF-31 appears to have stalled and DF-31A is operational in perhaps three brigades. Each missile can carry a single warhead. The DF-31AG is mentioned for the first time as an enhanced DF-31 with improved launcher maneuverability and survivability but may not yet be fully operational.

The long-awaited DF-41 ICBM remains in development and is listed by DOD as MIRV-capable. The report states that China is “considering additional launch options” for the DF-41, including rail-mobile and silo-basing. In silo-based version it would likely replace the DF-5.

The medium- and intermediate-range nuclear missile force is made up of three types: the new DF-26 IRBM, which is dual-capable and able to conduct conventional (both land-attack and anti-ship) and nuclear precision attacks; and two versions of the DF-21: DF-21A and DF-21E. The DF-21 A (SSC-5 Mod 2) has been deployed since the late-1990s. The DF-21E (note: the E designation is not official but assumed) is known as the SSC-5 Mod 6 and was first reported in 2016. The DF-21 also exists in two conventional versions: DF-21C and DF-21D (anti-ship).

The dual-capable DF-26, first fielded in 2016, is capable of conducting “nuclear precision strikes against ground targets.” There appears to be one or two DF-26 brigades.

The role of the new Strategic Support Force is listed as intended to “centralize the military’s space, cyber, and EW [Early Warning] missions. These would probably support the rocket force.

The Submarine Force

The DOD report says that China still operates four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs (all based at Hainan), each of which can carry up to 12 JL-2 SLBMs. At least one more Jin-SSBN is said to be under construction. Construction of a new SSBN (Type 096) may begin in the mid-2020s with a new SLBM (JL-3). DOD speculates that Type 094 and Type 096 SSBNs might end up operating concurrently, which, if accurate, could increase the size of the total SSBN fleet.

China also operates five Shang-class (Type 093/A) nuclear-powered attack submarines, with a sixth under construction. The Shang has now completely replaced the old Han-class (Type 092). DOD anticipates that a modified Shang (Type 093B) equipped with land-attack cruise missiles may begin building in the early-2020s. [Note: while many public sources call the two existing Shang versions Type 093A and Type 093B, the DOD report calls them Type 093 and Type 093A. The Type 093B is listed as a future type that until 2016 was called Type 095.]

Overall, China operates 56 submarines, of which 47 are diesel-electric. The report projects this force may increase to 69-78 submarines by 2020, a significant increase in only two years.

There is no mentioning in the DOD report of the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile listed in the Nuclear Posture Review fact sheet from February 2018.

The Bomber Force

One of the most interesting nuclear developments in the DOD report is the assessment that “the PLAAF has newly been re-assigned a nuclear mission.” This contrasts with last year’s report, which stated the “PLAAF does not currently have a nuclear mission.” The “re-assignment” indicates that the bombers previous had a nuclear mission. We have estimated that a small number of bombers had a dormant nuclear capability for gravity bombs as indicated by their extensive role in the nuclear weapons testing program and China’s display of nuclear bombs in military museums.

The DOD report states that the H-6 and the future stealth bomber could both be nuclear-capable. The future bomber, according to the DOD report, could potentially be operational within the next ten years.

The report repeats the estimate made by the U.S. Intelligence Community from the past two years that China is upgrading its aircraft with two new air-launched ballistic missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.

The DOD report does not mention the nuclear air-launched cruise missile listed the Nuclear Posture Review fact sheet from February 2018.

Additional Background:

Review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

Click on image to download copy of report. Note: NASIC later published a corrected version, available here

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB has updated and published its periodic Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. The new report updates the previous version from 2013.

At a time when public government intelligence resources are being curtailed, the NASIC report provides a rare and invaluable official resource for monitoring and analyzing the status of ballistic and cruise missiles around the world.

Having said that, the report obviously comes with the caveat that it does not include descriptions of US, British, French, and most Israeli ballistic and cruise missile forces. As such, the report portrays the international “threat” situation as entirely one-sided as if the US and its allies were innocent bystanders, so it will undoubtedly provide welcoming fuel for those who argue for increasing US defense spending and buying new weapons.

Also, the NASIC report is not a top-level intelligence report that has been sanctioned by the Director of National Intelligence. As such, it represents the assessment of NASIC rather than necessarily the coordinated and combined conclusion of the US Intelligence Community.

Nonetheless, it’s a unique and useful report that everyone who follows international security and ballistic and cruise missile developments should consult.

Overall, the NASIC report concludes: “The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in ballistic missile capabilities to include accuracy, post-boost maneuverability, and combat effectiveness.” During the same period, “there has been a significant increase in worldwide ballistic missile testing.” The countries developing ballistic and cruise missile systems view them “as cost-effective weapons and symbols of national power” that “present an asymmetric threat to US forces” and many of the missiles “are armed with weapons of mass destruction.” At the same time, “numerous types of ballistic and cruise missiles have achieved dramatic improvements in accuracy that allow them to be used effectively with conventional warheads.”

Some of the more noteworthy individual findings of the new report include:

- Russia’s nuclear modernization is, despite claims by some, not a “buildup” but the size of the Russian ICBM force will continue to decline.

- The Russian RS-26 “short” SS-27 ICBM is still categorized as an ICBM (as in the 2013 report) despite claims by some that it’s an INF weapon.

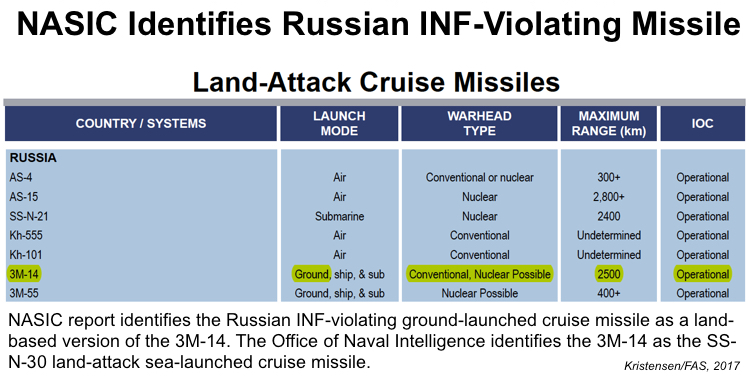

- The report is the first US official document to publicly identify the ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty: 3M-14. The weapon is assessed to “possibly” have a nuclear option. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

- The Russian SS-N-26 (Oniks or Onix) anti-ship cruise missile that is currently replacing several Soviet-era cruise missiles “possibly” has a nuclear option.

- The range of the dual-capable SS-26 (Islander) SRBM is listed as 350 km (217 miles) rather than the 500-700 km (310-435 miles) often claimed in the public debate.

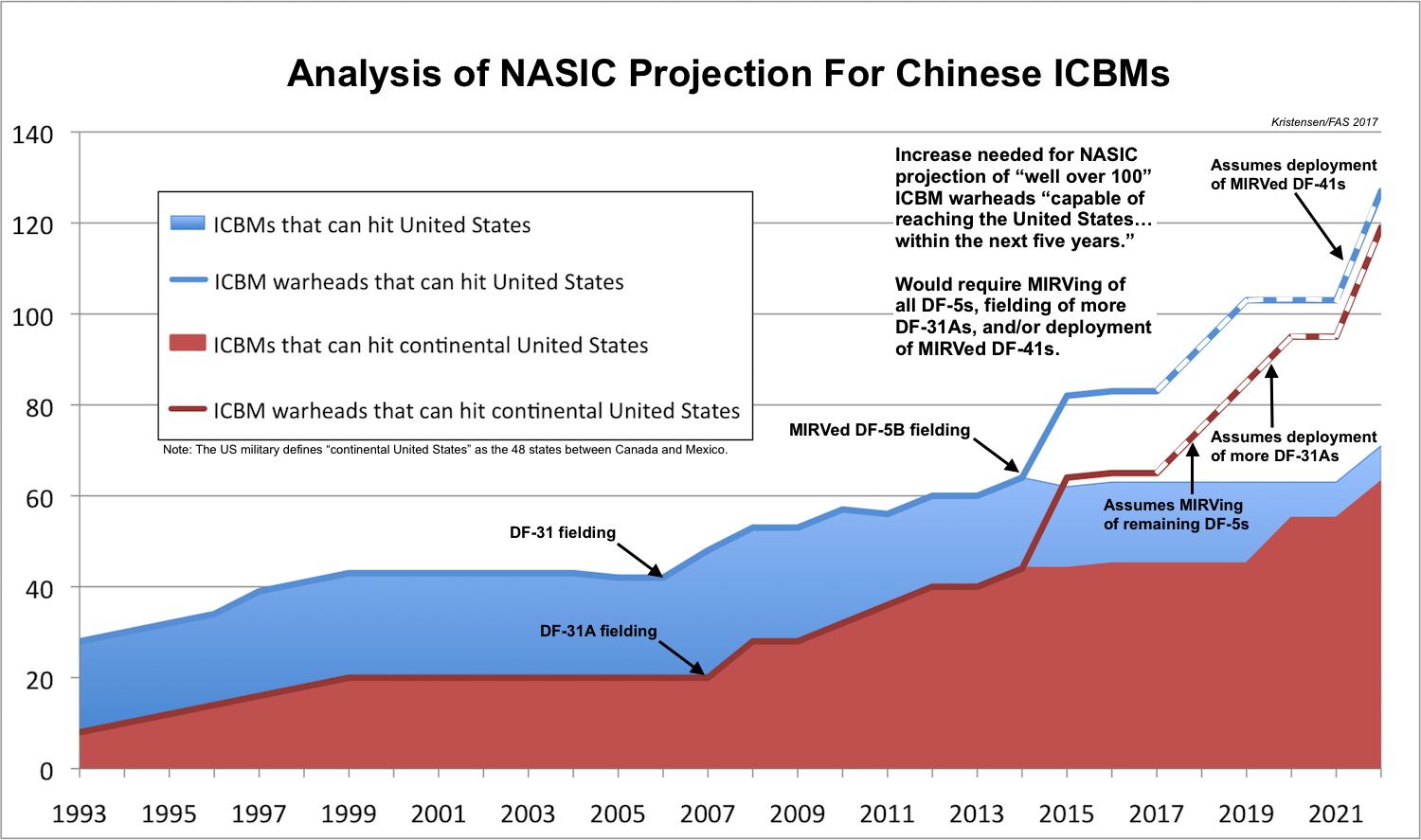

- The number of Chinese warheads capable of reaching the United States could increase to well over 100 in the next five years, six years sooner than predicted in the 2013 report. (The count includes warheads that can only reach Alaska and Hawaii, not necessarily all of continental United States.)

- Deployment of the Chinese DF-31/DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled.

- China’s long-awaited DF-41 ICBM will “possibly” be capable of carrying multiple warheads but is not yet deployed.

- Two Chinese medium-range ballistic missile types (DF-3A and DF-21 Mod 1) have been retired.

- The Chinese ground-launched DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is no longer listed as “conventional or nuclear” but only as “conventional.”

- None of North Korea’s ICBMs are listed as deployed.

Below I go into more details about the individual nuclear-armed states:

Russia

Russia is now more than halfway through its modernization, a generational upgrade that began in the mid/late-1990s and will be completed in the mid-2020s. This includes a complete replacement of the ICBM force (but at lower numbers), transition to a new class of strategic submarines, upgrades of existing bombers, replacement of all dual-capable SRBM units, and replacement of most Soviet-era naval cruise missiles with fewer types.

The NASIC report states that “Russian in September 2014 surpassed the United States in deployed warheads capable of reaching the United States,” referring to the aggregate number reported under the New START treaty. The report does not mention, however, that Russia since 2016 has begun to reduce its deployed strategic warheads and is expected meet the treaty limit in 2018.

ICBMs: Contrary to many erroneous claims in the public debate (see here and here) about a Russia nuclear “build-up,” the NASIC report concludes that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints…” This conclusion fits the assessment Norris and I have made for years that Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces but not increasing the size of the arsenal.

The report counts about 330 ICBM launchers (silos and TELs), significantly fewer than the 400 claimed by the Russian military. The actual number of deployed missiles is probably a little lower because several SS-19 and SS-25 units are in the process of being dismantled.

The development continues of the heavy Sarmat (RS-28), which looks very similar to the existing SS-18. The lighter SS-27 known as RS-26 (Rubezh or Yars-M) appears to have been delayed and still in development. Despite claims by some in the public debate that the RS-26 is a violation of the INF treaty, the NASIC report lists the missile with an ICBM range of 5,500+ km (3,417+ miles), the same as listed in the 2013 version. NASIC says the RS-26, which is designated SS-X-28 by the US Intelligence Community, has “at least 2” stages and multiple warheads.

Overall, “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs,” according to NASIC, another assessment that fits our estimate from the Nuclear Notebook. The NASIC report states that “most” of those missiles “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order.” (In comparison, essentially all US ICBMs are maintained on alert: see here for global alert status.)

SLBMs: The Russian navy is in the early phase of a transition from the Soviet-era Delta-class SSBNs to the new Borei-class SSBN. NASIC lists the Bulava (SS-N-32) SLBM as operational on three Boreis (five more are under construction). The report also lists a Typhoon-class SSBN as “not yet deployed” with the Bulava (the same wording as in the 2013 report), but this is thought to refer to the single Typhoon that has been used for test launches of the Bulava and not imply that the submarine is being readied for operational deployment with the missile.

While the new Borei SSBNs are being built, the six Delta-IVs are being upgrade with modifications to the SS-N-23 SLBM. The report also lists 96 SS-N-18 launchers, corresponding to 6 Delta-III SSBNs. But that appears to include 3-4 SSBNs that have been retired (but not yet dismantled). Only 2 Delta-IIIs appear to be operational, with a third in overhaul, and all are scheduled to be replaced by Borei-class SSBNs in the near future.

Cruise Missiles: The report lists five land-attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability, three of which are Soviet-era weapons. The two new missiles that “possibly” have nuclear capability include the mysterious ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty. The US first accused Russia of treaty violation in 2014 but has refused to name the missile, yet the NASIC report gives it a name: 3M-14. The weapon exists in both “ground, ship & sub” versions and is credited with “conventional, nuclear possible” warhead capability. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

Ground- and sea-based versions of the 3M-14 have different designations. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) identifies the naval 3M-14 as the SS-N-30 land-attack missile, which is part of the larger Kalibr family of missiles that include:

- The 3M-14 (SS-N-30) land-attack cruise missile (the nuclear version might be called SS-N-30A; Pavel Podvig reported back in 2014 that he was told about an 8-meter 3M-14S missile “where ‘S’ apparently stands for ‘strategic’, meaning long-range and possibly nuclear”);

- The 3M-54 (SS-N-27, Sizzler) anti-ship cruise missile;

- The 91R anti-submarine missile.

The US Intelligence Community uses a different designation for the GLCM version, which different sources say is called the SSC-8, and other officials privately say is a modification of the SSC-7 missile used on the Iskander-K. (For public discussion about the confusing names and designations, see here, here, and here.)

The range has been the subject of much speculation, including some as much as 5,472 km (3,400 miles). But the NASIC report sets the range as 2,500 km (1,553 miles), which is more than was reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense in 2015 but close to the range of the old SS-N-21 SLCM.

The “conventional, nuclear possible” description connotes some uncertainty about whether the 3M-14 has a nuclear warhead option. But President Vladimir Putin has publicly stated that it does, and General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command (EUCOM), told Congress in March that the ground-launched version is “a conventional/nuclear dual-capable system.”

ONI predicts that Kalibr-type missiles (remember: Kalibr can refer to land-attack, anti-ship, and/or anti-submarine versions) will be deployed on all larger new surface vessels and submarines and backfitted onto upgraded existing major ships and submarines. But when Russian officials say a ship or submarine will be equipped with the Kalibr, that can potentially refer to one or more of the above missile versions. Of those that receive the land-attack version, for example, presumably only some will be assigned the “nuclear possible” version. For a ship to get nuclear capability is not enough to simply load the missile; it has to be equipped with special launch control equipment, have special personnel onboard, and undergo special nuclear training and certification to be assigned nuclear weapons. That is expensive and an extra operational burden that probably means the nuclear version is only assigned to some of the Kalibr-equipped vessels. The previous nuclear land-attack SLCM (SS-N-21) is only assigned to frontline attack submarines, which will most likely also received the nuclear SS-N-30. It remains to be seen if the nuclear version will also go on major surface combatants such as the nuclear-propelled attack submarines.

The NASIC report also identifies the 3M-55 (P-800 Oniks (Onyx), or SS-N-26 Strobile) cruise missile with “nuclear possible” capability. This weapon also exists in “ground, ships & sub” versions, and ONI states that the SS-N-26 is replacing older SS-N-7, -9, -12, and -19 anti-ship cruise missiles in the fleet. All of those were also dual-capable.

It is interesting that the NASIC report describes the SS-N-26 as a land-attack missile given its primary role as an anti-ship missile and coastal defense missile. The ground-launched version might be the SSC-5 Stooge that is used in the new Bastion-P coastal-defense missile system that is replacing the Soviet-era SSC-1B missile in fleet base areas such as Kaliningrad. The ship-based version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the nuclear-propelled Kirov-class cruisers and Kuznetsov-class aircraft carrier. Presumably it will also replace the SS-N-12 on the Slava-class cruisers and SS-N-9 on smaller corvettes. The submarine version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the Oscar-class nuclear-propelled attack submarine.

NASIC lists the new conventional Kh-101 ALCM but does not mention the nuclear version known as Kh-102 ALCM that has been under development for some time. The Kh-102 is described in the recent DIA report on Russian Military Power.

Short-range ballistic missiles: Russia is replacing the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) missile with the SS-26 (Iskander-M), a process that is expected to be completed in the early-2020s. The range of the SS-26 is often said in the public debate to be the 500-700 km (310-435 miles), but the NASIC report lists the range as 350 km (217 miles), up from 300 km (186 miles) reported in the 2013 version.

That range change is interesting because 300 km is also the upper range of the new category of close-range ballistic missiles. So as a result of that new range category, the SS-26 is now counted in a different category than the SS-21 it is replacing.

China

The NASIC report projects the “number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100 within the next 5 years.” Four years ago, NASIC projected the “well over 100” warhead number might be reached “within the next 15 years,” so in effect the projection has been shortened by 6 years from 2028 to 2022.

One of the reasons for this shortening is probably the addition of MIRV to the DF-5 ICBM force (the MIRVed version is know as DF-5B). All other Chinese missiles only have one warhead each (although the warheads are widely assumed not to be mated with the missiles under normal circumstances). It is unclear, however, why the timeline has been shortened.

The US military defines the “United States” to include “the land area, internal waters, territorial sea, and airspace of the United States, including a. United States territories; and b. Other areas over which the United States Government has complete jurisdiction and control or has exclusive authority or defense responsibility.”

So for NASIC’s projection for the next five years to come true, China would need to take several drastic steps. First, it would have to MIRV all of its DF-5s (about half are currently MIRVed). That would still not provide enough warheads, so it would also have to deploy significantly more DF-31As and/or new MIRVed DF-41s (see graph below). Deployment of the DF-31A is progressing very slowly, so NASIC’s projection probably relies mainly on the assumption that the DF-41 will be deployed soon in adequate numbers. Whether China will do so remains to be seen.

China currently has about 80 ICBM warheads (for 60 ICBMs) that can hit the United States. Of these, about 60 warheads can hit the continental United States (not including Alaska). That’s a doubling of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States (including Guam) over the past 25 years – and a tripling of the number of warheads that can hit the continental United States. The NASIC report does not define what “well over 100” means, but if it’s in the range of 120, and NASIC’s projection actually came true, then it would mean China by the early-2020s would have increased the number of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States threefold since the early 1990s. That a significant increase but obviously but must be seen the context of the much greater number of US warheads that can hit China.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report describes the long and gradual upgrade of the Chinese ballistic missile force. The most significant new development is the fielding of the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with 16+ launchers. The missile was first displayed at the 2015 military parade, which showed 16 launchers – potentially the same 16 listed in the report. NASIC sets the DF-26 range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles), 1,000 km less than the 2017 DOD report.

China does not appear to have converted all of its DF-5 ICBMs to MIRV. The report lists both the single-warhead DF-5A and the multiple-warhead DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3) in “about 20” silos. Unlike the A-version, the B-version has a Post-Boost Vehicle, a technical detail not disclosed in the 2013 report. A rumor about a DF-5C version with 10 MIRVs is not confirmed by the report.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Deployment of the new generation of road-mobile ICBMs known as DF-31 and DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled; the number of launchers listed in the new report is the same as in the 2013 report: 5-10 DF-31s and “more than 15” DF-31As.

Yet the description of the DF-31A program sounds like deployment is still in progress: “The longer range CSS-10 Mod 2 will allow targeting of most of the continental United States” (emphasis added).

For the first time, the report includes a graphic illustration of the DF-31 and DF-31A side by side, which shows the longer-range DF-31A to be little shorter but with a less pointy nosecone and a wider third stage (see image).

The long-awaited (and somewhat mysterious) DF-41 ICBM is still not deployed. NASIC says the DF-41 is “possibly capable of carrying MIRV,” a less certain determination than the 2017 DOD report, which called the missile “MIRV capable.” The report lists the DF-41 with three stages and a Post-Boost Vehicle, details not provided in the previous report.

One of the two nuclear versions of the DF-21 MRBM appears to have been retired. NASIC only lists one: CSS-5 Mod 2. In total, the report lists “fewer than 50” launchers for the nuclear version of the DF-21, which is the same number it listed in the 2013 report (see here for description of one of the DF-21 launch units. But that was also the number listed back then for the older nuclear DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1). The nuclear MRBM force has probably not been cut in half over the past four years, so perhaps the previous estimate of fewer than 50 launchers was intended to include both versions. The NASIC report does not mention the CSS-5 Mod 6 that was mentioned in the DOD’s annual report from 2016.

Sea-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report lists a total of 48 JL-2 SLBM launchers, corresponding to the number of launch tubes on the four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs based at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. That does not necessarily mean, however, that the missiles are therefore fully operational or deployed on the submarines under normal circumstances. They might, but it is yet unclear how China operates its SSBN fleet (for a description of the SSBN fleet, see here).

The 2017 report no longer lists the Xia-class (Type 092) SSBN or the JL-1 SLBM, indicating that China’s first (and not very successful) sea-based nuclear capability has been retired from service.

Cruise Missiles: The new report removes the “conventional or nuclear” designation from the DH-10 (CJ-10) ground-launched land-attack cruise missile. The possible nuclear option for the DH-10 was listed in the previous three NASIC reports (2006, 2009, and 2013). The DH-10 brigades are organized under the PLA Rocket Force that operates both nuclear and conventional missiles.

A US Air Force Global Strike Command document in 2013 listed another cruise missile, the air-launched DH-20 (CJ-20), with a nuclear option. NASIC has never attributed nuclear capability to that weapon and the Office of the Secretary of Defense stated recently that the Chinese Air Force “does not currently have a nuclear mission.”

At the same time, the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently told Congress that China was upgrading is cruise missiles further, including “with two, new air-launched ballistic [cruise] missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.”

Pakistan

The NASIC report surprisingly does not list Pakistan’s Babur GLCM as operational.

The NASIC report states that “Pakistan continues to improve the readiness and capabilities of its Army Strategic Force Command and individual strategic missile groups through training exercises that include live missile firings.” While all nuclear-armed states do that, the implication probably is that Pakistan is increasing the reaction time of its nuclear missiles, particularly the short-range weapons.

The report states that the Shaheen-2 MRBM has been test-launched “seven times since 2004.” While that fits the public record, NASIC doesn’t mention that the Shaheen-2 for some reason has not been test launched since 2014, which potentially could indicate technical problems.

The Abdali SRBM now has a range of 200 km (up from 180 km in the 2013 report). It is now designated as close-range ballistic missile instead of a short-range ballistic missile.

NASIC describes the Ababeel MRBM, which was first test-launch in January 2017, as as “MIRVed” missile. Although this echoes the announcement made by the Pakistani military at the time, the designation “the MIRVed Abadeel” sounds very confident given the limited flight history and the technological challenges associated with developing reliable MIRV systems.

Neither the Ra’ad ALCM nor the Babur GLCM is listed as deployed, which is surprising especially for the Babur after 13 flight tests. Babur launchers have been fitting out at the National Development Complex for years and are visible at some army garrisons. Nor does NASIC mention the Babur-2 or Babur-3 (naval version) versions that have been test-flown and announced by the Pakistani military.

India

It is a surprise that the NASIC report only lists “fewer than 10” Agni-2 MRBM launchers. This is the same number as in 2013, which indicates there is still only one operational missile group equipped with the Agni-2 seven years after the Indian government first declared it deployed. The slow introduction might indicate technical problems, or that India is instead focused on fielding the longer-range Agni-3 IRBM that NASIC says is now deployed with “fewer than 10” launchers.

Neither the Agni-4 nor Agni-5 IRBMs are listed as deployed, even though the Indian government says the Agni-4 has been “inducted” into the armed forces and has reported three army “user trial” test launches. NASIC says India is developing the Agni-6 ICBM with a range of 6,000 km (3,728 miles).

For India’s emerging SSBN fleet, the NASIC report lists the short-range K-15 SLBM as deployed, which is a surprise given that the Arihant SSBN is not yet considered fully operational. The submarine has been undergoing sea-trials for several years and was rumored to have conducted its first submerged K-15 test launch in November 2016. But a few more are probably needed before the missile can be considered operational. The K-4 SLBM is in development and NASIC sets the range at 3,500 km (2,175 miles).

As for cruise missiles, it is helpful that the report continue to list the Bramos as conventional, which might help discredit rumors about nuclear capability.

North Korea

Finally, of the nuclear-armed states, NASIC provides interesting information about North Korea’s missile programs. None of the North Korean ICBMs are listed as deployed.

The report states there are now “fewer than 50” launchers for the Hwasong-10 (Musudan) IRBM. NASIC sets the range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles) instead of the 4,000 km (2,485 miles) sometimes seen in the public debate.

Likewise, while many public sources set the range of the mobile ICBMs (KN-08 and KN-14) as 8,000 km (4,970 miles) – some even longer, sufficient to reach parts of the United States, the NASIC report lists a more modest range estimate of 5,500+ km (3,418 miles), the lower end of the ICBM range.

Additional Information:

- Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2017 [Note: A corrected NASIC report was published in June 2017.]

- Previous versions of this NASIC report: 2006, 2009, 2013

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US-China Scientific Cooperation “Mutually Beneficial”

The US and China have successfully carried out a wide range of cooperative science and technology projects in recent years, the State Department told Congress last year in a newly released report.

Joint programs between government agencies on topics ranging from pest control to elephant conservation to clean energy evidently worked to the benefit of both countries.

“Science and technology engagement with the United States continues to be highly valued by the Chinese government,” the report said.

At the same time, “Cooperative activities also accelerated scientific progress in the United States and provided significant direct benefit to a range of U.S. technical agencies.”

The 2016 biennial report to Congress, released last week under the Freedom of Information Act, describes programs that were ongoing in 2014-2015.

See Implementation of Agreement between the United States and China on Science and Technology, report to Congress, US Department of State, April 2016.

The Pentagon’s 2017 Report On Chinese Military Affairs

The Pentagon report says China is “developing a strategic bomber that officials expect to have a nuclear mission.” The Internet is full of artistic fantasies of what it might look like.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s latest annual report to Congress on Chinese military and security developments describes a nuclear force that is similar to previous years but with a couple of important new developments in the pipeline.

The most sensational nuclear news in the report is the conclusion that China is developing a new strategic nuclear bomber to replace the aging (but upgraded) H-6.

The report also portrays the Chinese ICBM force as a little bigger than it really is because the report lists missiles rather than launchers. But once adjusted for that, the report shows the same overall nuclear missile force as in 2016, with two new land-based missiles under development (DF-26 and DF-41) but not yet operational.

The SSBN force is described as the same four boats but with “others” under construction. The report is a bit hasty to declare China now has a survivable sea-based deterrent, a condition that will require a few more steps.

Finally, the report concludes that Chinese nuclear strategy and doctrine, despite a domestic debate about scope and role, are unchanged from previous years.

Nuclear Bombers?

The Pentagon report states unequivocally that the Chinese Air Force “does not currently have a nuclear mission.” Yet bombers delivered nuclear gravity bombs in at least 12 of China’s nuclear test explosions between 1965 and 1979, so China probably has some dormant air-delivered nuclear capability.

But the report goes further by stating that China now “is developing a strategic bomber that officials expect to have a nuclear mission.”

In making this affirmative conclusion, the report refers to several sources. First, a 2016 statement by PLAAF commander Ma Xiaotian that China was “developing a next generation, long-range strike bomber” to replace the H-6 bombers. Second, the “nuclear” role is attributed to unidentified “observers” and speculations that “past PLA writings” about the need for a “stealth strategic bomber” suggests “aspirations to field a strategic bomber with a nuclear delivery capability.“

Although the Pentagon report says the Chinese Air Force does not currently have a nuclear mission, China has developed and tested nuclear gravity bombs. Mock-ups of the first fission bomb (left) and first thermonuclear bomb are on display in Beijing.

A U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing in 2013 attributed nuclear capability to the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile that is now operational with the H-6K bomber. And in May 2017, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency told Congress that China is “upgrading its aircraft…with two, new air-launched [ballistic cruise] missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.”

Whether a nuclear strategic bomber emerges sometime in the mid-2020s remains to be seen. If so, it would change China’s nuclear posture into a formal Triad of air-, land- and sea-based nuclear capabilities, similar to U.S. and Russian strategic arsenals.

The ICBM Force

The most mysterious nuclear number in the Pentagon report is this: “75-100 ICBMs.”

According to the report, “China’s nuclear arsenal currently consists of approximately 75-100 ICBMs, including the silo-based CSS-4 Mod 2 (DF-5A) and Mod 3(DF-5B); the solid-fueled, road-mobile CSS-10 Mod 1 and Mod 2 (DF-31 and DF-31A); and the more-limited-range CSS-3 (DF-4).”

The “75-100 ICBMs” estimate was also made in the 2016 report, but in the 2015 and earlier reports, the estimate was: “China’s ICBM arsenal currently consists of 50-60 ICBMs” of the same five types. For the “75-100 ICBM” estimate to be true, China would have had to add 15-40 ICBMs between 2015 and 2016, which probably did not happen.

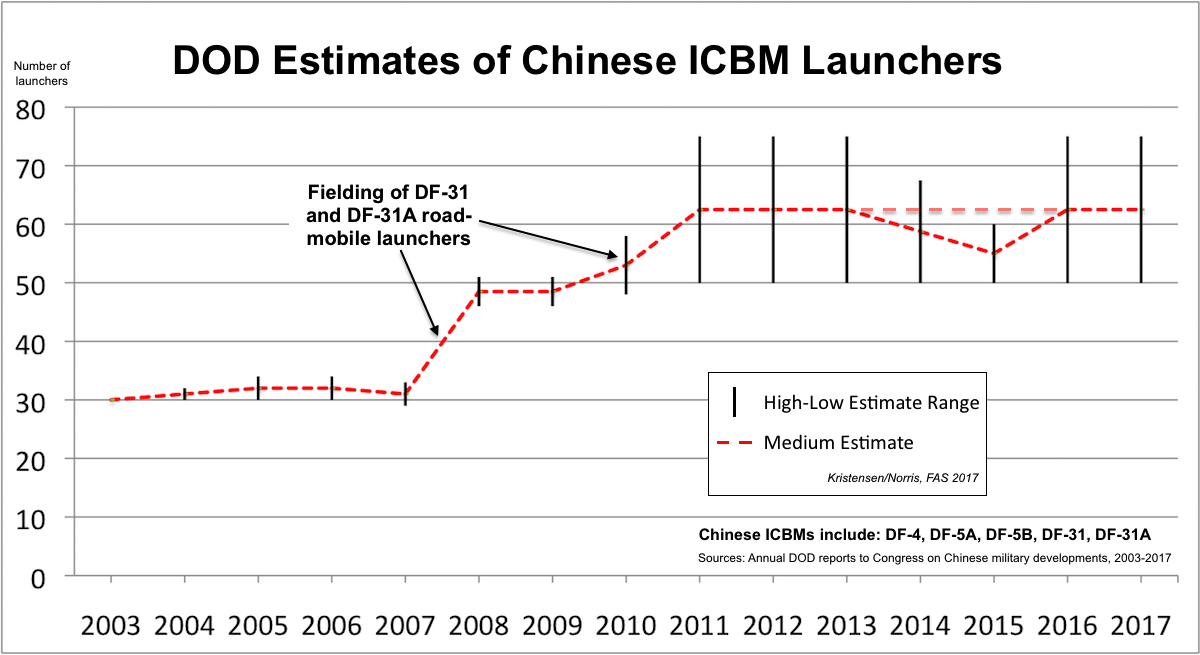

The confusion appears to be caused by a change in terminology: the “75-100” is the number of missiles available for the ICBM launchers, some of which have reloads. There are only 50-75 ICBM launchers, the same number listed in the previous six reports. In fact, the ICBM force structure appears to have been relatively stable since 2011.

The 2017 report lists the same number of Chinese ICBM launchers as the previous six years. Click on image to view full size.

Of those 50-75 ICBM launchers, only about 45 (DF-5 and DF-31A) can target the continental United States.

Development continues of the road-mobile DF-41 ICBM, which the report says is “MIRV capable” like the existing silo-based DF-5B. The rumored DF-5C that some news media reported earlier this year is not mentioned in the Pentagon report, even though the Chinese Ministry of Defense appeared to acknowledge the existence of a DF-5C version in a response to the rumors.

Other Land-Base Nuclear Missiles

The report states that China in 2016 began fielding the new road-mobile, dual-capable, intermediate-range DF-26. The missile is not included in the total missile force overview, however, indicating that it is not yet operational. The maximum range is estimated at 4,000 km (2,485 miles), which means it could potentially target Guam from eastern China (similar to the current DF-4 and DF-31).

The DF-26 IRBM is “fielding” but the Pentagon report does not yet include it in the total missile count.

The road-mobile DF-26 will complement the existing force of DF-21 medium-range missiles, of which two versions are nuclear-capable, in China’s regional deterrence mission. And the DF-26 will probably replace the old liquid-fueled DF-4. The other old liquid-fueled missile, the DF-3A, now appears to have been retired.

The SSBN Force

The Pentagon report lists four Jin-class (Type-024) SSBNs as commissioned and “others under construction.” All Jin SSBNs are homeported at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. The report declares that “China’s JIN SSBNs, which are equipped to carry up to 12 CSS-N-14 (JL-2) SLBMs, are the country survivable sea-based nuclear deterrent.”

One of the four Jin-class SSBNs based at Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island flashes nine of twelve SLBM tubes. Image: DigitalGlobe via GoogleEarth, April 17, 2016.

There are probably several caveats buried in that assessment. First, “survivable” requires that the SSBNs, once deployed at sea, can hide and avoid detection by US and allied anti-submarine warfare capabilities. Jin SSBNs apparently are rather noisy. Second, is the JL-2 operational on the SSBNs? Do they deploy with the missiles, train with them, and do they practice deterrent patrols and launch procedures?

The operational status is unclear from the report, which instead describes an effort to develop “more sophisticated C2 systems and processes” for “future SSBN deterrence patrols…” Rather, the Jin SSBNs appear to be a work in progress.

One indication the Jin-class might not constitute a “survivable” capability is that development of a replacement has already started. The future SSBN, which the Pentagon report says might begin construction in the early-2020s, reportedly will be equipped with a new SLBM known as JL-3. The new missile will probably have longer range than the current JL-2, which is insufficient to target the continental United Stated from Chinese waters.

Once China develops an operational aircraft carrier battle group, the report predicts, it would also be able to protect nuclear ballistic missile submarines stationed on Hainan Island. China has already built a carrier pier at the Yulin Naval Base on Hainan Island (see image below). Like so many other things, such a carrier battle group mission would depend on a number of things, not least how survivable it will be and how effective its anti-submarine capability will be.

The Liaoning docked at the carrier pier at Yulin Naval Base on Hainan Island. Image: DigitalGlobe via GoogleEarth, December 3, 2013.

Additional information:

- Pentagon Annual Report To Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces 2016

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2016

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

China’s nuclear forces are limited compared with those of Russia and the United States. Nonetheless, its arsenal is slowly increasing both in numbers of warheads and delivery vehicles.

In our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, we estimate that China has a stockpile of about 260 nuclear warheads for delivery by a growing diversity of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles and bombers.

Changes over the past year include fielding of the new dual-capable DF-26 road-mobile intermediate-rage ballistic missile, the reported fielding of a new nuclear version (Mod 6) of the DF-21 road-mobile medium-range ballistic missile, more flight-tests of the long-rumored DF-41 road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missile, and the slow readying of the Jin-class (Type 094) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines.

China is also modernizing its aging fleet of H-6 bombers, some of which may have a secondary nuclear role.

Although China is still thought to be fielding more DF-31A launchers, the overall number of ICBM launchers has not increased since 2011 but remained at 50-75 launchers. The oldest of these, the liquid-fuel DF-4, apparently has an extra load of missiles but is thought to be close to retirement. None of the new ICBMs are thought to have reloads.

ICBM Exercises and Force Level

Chinese television showed PLARF (PLA Rocket Force) videos of several exercises in late-2015 and early-2016 that included DF-4, DF-21 and DF-31 launchers.

One video showed what was said to be a Rocket Force exercise in northeast China in early 2016 that included a DF-31 launcher. The characteristic outline of the launch site made it possible for us (and many others) to identify the location as a launch unit site of the 816 Brigade at Tonghua in the Jilin province (see image below). The 816 Brigade is thought to be equipped with the DF-21 so the DF-31 exercise probably involved a launch unit on an extended deployment from another brigade.

A DF-31 or DF-31A launcher in exercise on launch pad near Tonghua in northeast China in early-2016. Image: CCTV13.

Although the liquid-fuel DF-4 ICBM is old and very slow as a retaliatory weapon, the single remaining brigade near Lingbao continued to conduct launch exercises in late-2015 and early-2016. One of these involved a roll-out-to-launch exercise from a missile garage of the 801 Brigade near Lingbao in Henan province (see image below). The DF-4 will likely be phased out in the near future.

A DF-4 launch unit near Lingbao held a roll-out-to-launch exercise in late-2015. Image: PLARF via CCTV-13.

Overall the number of Chinese ICBM launchers has been growing slowly since the mid-2000s. The DF-31 and its longer-range version DF-31A have been slowly fielding since 2006 and 2007, respectively, although the DF-31 seems to have stalled after less than 10 launchers. The DF-31A may still be fielding but not much. Since the mid-2000s, the introduction of these two systems has doubled the size of the Chinese ICBM force from around 30 to around 60. The force has been stable since 2011 (see image below).

Chinese ICBM launchers doubled between 2006 and 2011 but have remained steady since. Click to view full size.

There have also been several unconfirmed reports of a new DF-41 ICBM being test-launched, sometimes from rail cars. The Pentagon first predicted fielding of the long-rumored DF-41 in the late-1990s but then dropped references to the weapon system until two years ago when it stated that the missile might be capable of carrying MIRV warheads. Since then several photos of an eight-axel launcher have appeared on the Internet with unconfirmed claims that they showed the DF-41.

Once the DF-41 finally deploys, it will likely result in the retirement of the DF-4 and potentially also the liquid-fuel silo-based DF-5A/B, some of which have recently been equipped to carry MIRV.

DOD projections for the number of Chinese ICBM warheads that could threaten the United States have fluctuated over the years, generally promising too much too soon. Moreover, the projections have been inconsistent about whether they concerned warheads that could reach any part of the United States or just the continental United States. With the addition of MIRV to the DF-5B and potentially also on the future DF-41, the projections could potentially reach approximately 100 warheads in the foreseeable future (see graph below).

US agency projections for Chinese ICBM warheads have promised too much too soon. But with Chinese MIRVing of some ICBMs, the projections could potentially come true. Click to view full size.

IRBM/MRBM Developments

China is also boosting its force of medium- and inter-medium-range ballistic missiles for regional deterrence missions. The most important new development is the introduction of the new DF-26, an intermediate-range dual-capable road-mobile ballistic missile. Sixteen launchers were shown during the 2015 military parade but the system is probably still in its early stages of introduction.

The focus on missiles for regional deterrence missions is particularly clear in the fielding of several conventional versions of the solid-fuel DF-21 MRBM (DF-21C or CSS-5 Mod 4, and DF-21D or CSS-5 Mod 5). But the 2016 DOD report on Chinese military development also reports deployment of a new nuclear version of the DF-21, designated CSS-5 Mod 6. China already operates two older nuclear versions of the DF-21 (DF-21 or CSS-5 Mod 1, and DF-21A or CSS-5 Mod 2). It is unclear if the new Mod 6 version will be deployed alongside the two older versions or if it is intended to replace them.

More than 25 years after the DF-21 first began replacing the liquid-fuel DF-3A medium-range ballistic missile, the transition seems to be complete and the DF-3A finally retired. One of the bases where the transition has been visible is the 810 Brigade launch site near Dengshahe in the Liaoning province of northeast China. Commercial satellite images show the transition from DF-3A in 2003 to the DF-21 in 2014. A satellite image from April 2016 shows three DF-21 launchers positioned on the launch pads along with support vehicles (see image below).

The SSBN Fleet

China’s attempt to build an SSBN fleet has so far resulted in four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs entering service. The US Navy says all four are based at the Longpo naval base on Hainan Island, although commercial satellite images have so far only shown three SSBNs at the base simultaneously.

The big question, which has generated lots of Internet rumors and news media articles, is whether the Jin fleet has yet conducted a deterrence patrol with nuclear-tipped JL-2 missiles onboard. We find that highly unlikely given the Chinese leadership’s reluctance to hand out nuclear weapons to the military services in peacetime. It is possible that one or more of the Jin subs have sailed on long voyages far from Chinese waters, but we haven’t seen credible sources reporting actual nuclear deterrent patrols yet.

Another area of speculation is how China will operate its SSBN fleet once it becomes fully operational. Most reports bluntly state that the Jin fleet will provide China with a secure second-strike capability. But that is an overstatement, given the technological, operational, and geographic challenges the Jin fleet faces. The Jin subs are as noisy [/blogs/security/2009/11/subnoise/] as submarines built by the Soviet Union back in the 1970s, the Chinese navy has almost no experience in operating nuclear-armed submarines, and the limited range of the JL-2 requires the submarine to sail far into dangerous waters to be able to hit targets in the United States.

ONI stated in 2015 [http://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/China_Media/2015_PLA_NAVY_PUB_Print.pdf?ver=2015-12-02-081247-687] that, once deployed, the Jin/JL-2 weapon system “will provide China with a capability to strike targets on the continental United States.” But that’s an overstatement. To reach targets on the continental United States, a Jin SSBN with JL-2 SLBMs would have to sail at least 3,600 kilometers (2,200 miles) from its base on Hainan Island into the Pacific Ocean just to be able to target Seattle (see image). Alaska and Guam could be hit from Chinese waters but Hawaii could not. Moreover, to target Washington, DC, a Jin SSBN would have to sail halfway across the Pacific Ocean.

Despite claims by many, including the US Navy, the JL-2 SLBM does not have sufficient range to target the continental United States.

We have analyzed the Chinese SSBN fleet for the past decade and frequently pointed out the tendency to overstate or exaggerate the capability of the Jin-class SSBNs and their missiles. The Jin-class fleet seems more like a work in progress that is intended to build technology and operational experience for the next generation SSBN: the Type 096.

Background: Chinese nuclear forces, 2016 (FAS Nuclear Notebook)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pentagon Report And Chinese Nuclear Forces

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s latest annual report on Chinese military developments mainly deals with non-nuclear issues, but it also contains important new information about developments in China’s nuclear forces. This includes:

- The size of China’s ICBM force has been relatively stable over the past five years

- China has deployed a new version of a medium-range ballistic missile

- A new intermediate-range ballistic missile is not yet deployed

- China’s SSBN fleet has yet to conduct its first deterrent patrol

- The possibility of nuclear capability for Chinese bombers

- Changes (or not) to Chinese nuclear policy

ICBM Developments

The future development of China’s ICBM force has been the subject of much speculation and projections over the years. Despite important new developments, this year’s report describes the size of the ICBM force as consistent with the force level reported over the past five years: around 60 launchers. Fielding of the DF-31 appears to have stalled and the data suggests that fielding of the DF-31A has been modest: so far about 20-30 launchers, enough for perhaps 4-5 brigades (see graph).

In 2012, the DOD report predicted that by 2015, “China will also field additional road-mobile DF-31A” launchers. But that doesn’t seem to have happened. Instead, the ICBM launcher force has remained relatively stable since 2011.

The number of I CBM launchers reported by the annual DOD reports over the past 13 years has fluctuated considerably, from around 30 in 2003 to 50 to 60-plus launchers in 2008 and later years. The uncertainty has been greatest in 2011-2013 and 2016 with a plus/minus of 25 launchers. That’s a significant uncertainty of approximately 40 percent in recent years versus around 10 percent in earlier years. But it seems clear that the Chinese ICBM forces is so far not continuing to grow.

CBM launchers reported by the annual DOD reports over the past 13 years has fluctuated considerably, from around 30 in 2003 to 50 to 60-plus launchers in 2008 and later years. The uncertainty has been greatest in 2011-2013 and 2016 with a plus/minus of 25 launchers. That’s a significant uncertainty of approximately 40 percent in recent years versus around 10 percent in earlier years. But it seems clear that the Chinese ICBM forces is so far not continuing to grow.

While the number of launchers has been relatively stable, the DOD report shows a mysterious increase of missiles for those launchers: 75-100 missiles for 50-75 launchers. This is inconsistent with previous DOD reports, which have either listed the same number of launchers and missiles, or a slightly higher number of missiles because of a reload capability of the old DF-4 (see table).

It is unclear why the 2016 report suddenly increases the number of missiles to 25 more than the number of launchers. Neither the DF-5 nor the DF-31/31A ICBMs are thought to have reloads. Past DOD reports that included missile estimates always listed one reload for the DF-4, not any other system. With only about 10 DF-4 launchers left in the arsenal, the number of extra missiles in 2016 should probably be 10, not 25 (the 25 would fit better if there were two reloads for the DF-4). As far as I can tell, here is what the Chinese ICBM force looks like:

Despite many rumors in the public debate that China has developed or is developing rail-based versions of its ICBMs, there is no mentioning in the DOD report of any rail-based system. Here is out latest overview of Chinese nuclear forces. An update will be published in July.

DF-26 Nuclear Precision Strike?

China’s newest nuclear-capable missile, the DF-26 (DOD provides no CSS designation for the new missile) that was unveiled during the September 2015 parade in Beijing, appears not to have been deployed with missile units yet.

Sixteen six-axel launchers were displayed during the parade and described as the official commentator as nuclear-capable. The missile is not yet deployed. Image: PLA.

The DOD report states that the DF-26, if it uses the same guidance for the nuclear and the conventional payloads, “would give China its first nuclear precision strike capability against theater targets.”

This statement indicates that DOD does not believe that any of China’s other nuclear-capable missiles have precision strike capability.

A New DF-21 Version?

The DOD report also lists a new version of the nuclear medium-range DF-21 missile but provides no details. The new version is called DF-21 Mod 6, or CSS-5 Mod 6 as it is listed in the report.

The DOD report says China has deployed a new version of the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile. Here a DF-21 takes part in a nuclear strike exercise in 2015. Image: PLA via CCTV-13.

The previous report from 2015 stated that the ICBM force was complemented by the “road-mobile, solid-fueled CSS-5 (DF-21) MRBM for regional deterrence missions.” The 2016 report, however, states that the ICBM force “is complemented by road-mobile, solid-fueled CSS-5 Mod 6 (DF-21) MRBM for regional deterrence missions,” the first time the Mod 6 designation has been used.

DOD does not provide any details about what the Mod 6 version is and to what extent it affects the status of the two original nuclear versions (Mod 1 and Mod 2). The original versions are getting old, so one possibility might be that the Mod 6 version is intended to replace them. But it is unclear what the status is.

DF-21 holds a special status in the history of Chinese forces because it was the first real mobile solid-fuel missile that replaced the old and more cumbersome liquid-fuel missiles. The Mod 1 was first fielded in the late-1980s although deployment didn’t really get underway until 1992. The Mod 2 was “not yet deployed” in 1998, according to NASIC, but both versions were listed as deployed by 2000. That was also the case in 2013, which suggest that the two versions might not be that different (perhaps range is the only difference), or that they are different but both retained for specific missions.

There is a lot of confusion about the different versions of the DF-21 in the public debate where many authors re-use secondary sources instead of relying on the original reference material. The most common mistake is to refer to the DF-21C conventional land-attack version as the CSS-5 Mod 3 and the DF-21D anti-ship version as the CSS-5 Mod 4. Over the years, DOD and the U.S. Intelligence Community have reported the following versions of the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile:

DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1): nuclear

DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2): nuclear

DF-21C (CSS-5 Mod 4): conventional land-attack

DF-21D (CSS-5 Mod 5): conventional anti-ship

DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 6): nuclear (new)

It is not clear what happened to DF-21B and/or CSS-5 Mod 3. In any case, the DF-21 has now completely replaced the old liquid-fuel DF-3As that dominated the Chinese regional nuclear deterrence posture since the early-1970s. The last brigade to convert to DF-21 possibly was the 810 Brigade at Dengshahe in Liaoning province.

About That Credible Sea-Based Deterrent

It seems that various news media reports and official statement continue to exaggerate or preempt the operational capability of the Chinese submarine force. Many have said the new Jin-class SSBNs had begun conducting deterrent patrols, but the DOE report seems to indicate that the subs (or rather, their missiles) are not yet fully operational.

In February 2015, for example, the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Vice Admiral Joseph Mulloy, reportedly told Congress that one SSBN had gone on a 95-day patrol. Later, STRATCOM Commander Admiral Cecil Haney said SSBNs had been at sea but that he didn’t know if they had nukes on board but had to assume they did.

In contrary to these statements, the DOD report states the Jin-class SSBN “will eventually carry” the JL-2 SLBM (apparently it doesn’t yet do so) and that “China will probably conduct its first SSBN nuclear deterrence patrol sometime in 2016.” So apparently not yet.

This “not quite yet” assessment was supported by the Defense Intelligence Agency saying “the PLA Navy deployed the JIN-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine in 2015, which, when armed with the JL-2 SLBM, provides Beijing its first sea-based nuclear deterrent.” (Emphasis added.)

So one or more SSBNs might have sailed on some kind of deployment, but not necessarily with nuclear weapons onboard. All four operational Jin SSBNs are based at Longpo (Yulin) Submarine Base on Hainan Island, along with two Shang-class nuclear-powered attack submarines. A fifth Jin SSBN is under construction.

The DOD report also seems to debunk a rumor that China is building up to five additional Jin-class SSBNs. The head of US Pacific Command in 2015 told Congress that in addition to the submarines already launched, “up to five more may enter service by the end of the decade.” That seems to have been a fluke. The DOD report says a fifth Jin is under construction after which China will probably move on to a next-generation SSBN (Type 096) armed with a new missile (JL-3).

Nuclear Bombers?

The DOD report for the first time raises the issue of a potential nuclear role for the bombers. It does so by referencing various Chinese writings but without presenting a clear U.S. Intelligence Community conclusion about such a capability:

A thermonuclear bomb is dropped from an H-6 bomber in June 1967.

“In 2015, China also continued to develop long-range bombers, including some Chinese military analysts have described as “capable of performing strategic deterrence”—a mission reportedly assigned to the PLA Air Force in 2012. There have also been Chinese publications indicating China intends to build a long-range “strategic” stealth bomber. These media reports and Chinese writings suggest China might eventually develop a nuclear bomber capability. If it does, China would develop a “triad” of nuclear delivery systems dispersed across land, sea, and air—a posture considered since the Cold War to improve survivability and strategic deterrence.”

Chinese bombers are normally not considered to have an active nuclear role and the “strategic deterrence” mission assigned to PLAA in 2012 could potentially also reflect the introduction of conventional land-attack cruise missiles on the modified H-6K bomber. Yet a US Air Force Global Strike command briefing in 2013 listed the new CJ-20 air-launched land-attack cruise missile carried by the H-6K as nuclear-capable.

And China in the past certainly developed the capability to deliver nuclear weapons from bombers. Between 1965 and 1979, bombers delivered the nuclear weapon for at least 12 of China’s nuclear test explosions. These tests involved both fission and thermonuclear weapons with yields ranging from 5-10 kilotons, a few hundred kilotons, to 2-4 megatons. The bombs were delivered by H-6 bombers (still in service and being modernized), H-5 bombers (retired), and Q-5 fighter-bombers (nearly all retired).

The Military Museum in Beijing apparently has on display models of at least two nuclear bomb designs: a fission bomb and a hydrogen bomb. This video shows what is said to be China’s first test of a thermonuclear bomb, delivered by an H-6 bomber in June 1967.

Two nuclear bomb models are displayed in Beijing, the first fission bomb (left) and the first thermonuclear bomb (right). The marking on the thermonuclear bomb H639-23 is similar to those on the bomb used in the nuclear test on June 17, 1967: H639-6. Image: news.cn

Nuclear Policy and Strategy

Finally, the DOD report also summarizes the US understanding of Chinese nuclear policy and strategy.

The first is that the PLA has deployed new command, control, and communications capabilities to its nuclear forces to improve control of multiple units in the field. “Through the use of improved communications links,” DOD concludes, “ICBM units now have better access to battlefield information and uninterrupted communications connecting all command echelons. Unit commanders are able to issue orders to multiple subordinates at once, instead of serially, via voice commands.”

This is intended to improve control of the units but also to enhance their combat effectiveness in a crisis situation. To that end the DOD report mentions recent press accounts that China “may be enhancing peacetime readiness for nuclear forces to ensure responsiveness.” Part of this debate reflects a report by Gregory Kulacki citing Chinese military documents and statements that the nuclear forces may move towards a “launch-on-warning” posture to be able to launch missiles before they can be destroyed.

Despite these problematic developments, the DOD report concludes that there are no signs that China’s no-first-use policy and negative security assurance have been changed.

In other words, while Chinese nuclear policy itself does not appear to have changed, the way China deploys and operates its nuclear forces appears to be evolving significantly.

Additional resources:

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

FAS Engagement With China

“Supporting and expanding on Frank von Hippel’s cogent and exciting narrative of some of the great accomplishments of the Federation of American Scientists, I detail below two endeavors, at least one of which may have had far-reaching impact. The first was the initiative of FAS Director (and later President) Jeremy J. Stone who, in 1971, wrote the president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences to introduce FAS and to begin some kind of dialogue…”

Nuclear Transparency and the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

I was reading through the latest Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and wondering what I should pick to critique the Obama administration’s nuclear policy.

After all, there are plenty of issues that deserve to be addressed, including:

– Why NNSA continues to overspend and over-commit and create a spending bow wave in 2021-2026 in excess of the President’s budget in exactly the same time period that excessive Air Force and Navy modernization programs are expected to put the greatest pressure on defense spending?

– Why a smaller and smaller nuclear weapons stockpile with fewer warhead types appears to be getting more and more expensive to maintain?

– Why each warhead life-extension program is getting ever more ambitious and expensive with no apparent end in sight?

– And why a policy of reductions, no new nuclear weapons, no pursuit of new military missions or new capabilities for nuclear weapons, restraint, a pledge to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and the goal of disarmament, instead became a blueprint for nuclear overreach with record funding, across-the-board modernizations, unprecedented warhead modifications, increasing weapons accuracy and effectiveness, reaffirmation of a Triad and non-strategic nuclear weapons, continuation of counterforce strategy, reaffirmation of the importance and salience of nuclear weapons, and an open-ended commitment to retain nuclear weapons further into the future than they have existed so far?

What About The Other Nuclear-Armed States?

Despite the contradictions and flaws of the administration’s nuclear policy, however, imagine if the other nuclear-armed states also published summaries of their nuclear weapons plans. Some do disclose a little, but they could do much more. For others, however, the thought of disclosing any information about the size and composition of their nuclear arsenal seems so alien that it is almost inconceivable.

Yet that is actually one of the reasons why it is necessary to continue to work for greater (or sufficient) transparency in nuclear forces. Some nuclear-armed states believe their security depends on complete or near-compete nuclear secrecy. And, of course, some nuclear information must be protected from disclosure. But the problem with excessive secrecy is that it tends to fuel uncertainty, rumors, suspicion, exaggerations, mistrust, and worst-case assumptions in other nuclear-armed states – reactions that cause them to shape their own nuclear forces and strategies in ways that undermine security for all.

Nuclear-armed states must find a balance between legitimate secrecy and transparency. This can take a long time and it may not necessarily be the same from country to country. The United States also used to keep much more nuclear information secret and there are many institutions that will always resist public access. But maximum responsible disclosure, it turns out, is not only necessary for a healthy public debate about nuclear policy, it is also necessary to communicate to allies and adversaries what that policy is about – and, equally important, to dispel rumors and misunderstandings about what the policy is not.

Nuclear transparency is not just about pleasing the arms controllers – it is important for national security.

So here are some thoughts about what other nuclear-armed states should (or could) disclose about their nuclear arsenals – not to disclose everything but to improve communication about the role of nuclear weapons and avoid misunderstandings and counterproductive surprises:

Russia should publish:

Russia should publish:

– Full New START aggregate data numbers (these numbers are already shared with the United States, that publishes its own numbers)

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Number of history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has made statements about percentage reductions since 1991 but not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of which nuclear forces are nuclear-capable (has made some statements about strategic forces but not shorter-range forces)

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces (has made occasional statements about modernizations but no detailed plan)

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

China should publish:

China should publish:

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (stated in 2004 that it possessed the smallest arsenal of the nuclear weapon states but has not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of its nuclear-capable forces

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

France should publish:

France should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has disclosed the size of its nuclear stockpile in 2008 and 2015 (300 weapons), but not the history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has declared dismantlement of some types but not history)

(France has disclosed its overall force structure and some nuclear budget information is published each year.)

Britain should publish:

Britain should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has declared some approximate historic numbers, declared the approximate size in 2010 (no more than 225), and has declared plan for mid-2020s (no more than 180), but has not disclosed history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has announced dismantlement of systems but not numbers or history)

(Britain has published information about the size of its nuclear force structure and part of its nuclear budget.)

Pakistan should publish:

Pakistan should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

India should publish:

India should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

Israel should publish:

Israel should publish:

…or should it? Unlike other nuclear-armed states, Israel has not publicly confirmed it has a nuclear arsenal and has said it will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Some argue Israel should not confirm or declare anything because of fear it would trigger nuclear arms programs in other Middle Eastern countries.

On the other hand, the existence of the Israeli nuclear arsenal is well known to other countries as has been documented by declassified government documents in the United States. Official confirmation would be politically sensitive but not in itself change national security in the region. Moreover, the secrecy fuels speculations, exaggerations, accusations, and worst-case planning. And it is hard to see how the future of nuclear weapons in the Middle East can be addressed and resolved without some degree of official disclosure.

North Korea should publish:

North Korea should publish:

Well, obviously this nuclear-armed state is a little different (to put it mildly) because its blustering nuclear threats and statements – and the nature of its leadership itself – make it difficult to trust any official information. Perhaps this is a case where it would be more valuable to hear more about what foreign intelligence agencies know about North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. Yet official disclosure could potentially serve an important role as part of a future de-tension agreement with North Korea.

Additional information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces with links to more information about individual nuclear-armed states.

“Nuclear Weapons Base Visits: Accident and Incident Exercises as Confidence-Building Measures,” briefing to Workshop on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Practice, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 27-28 March 2014.

“Nuclear Warhead Stockpiles and Transparency” (with Robert Norris), in Global Fissile Material Report 2013, International Panel on Fissile Materials, October 2013, pp. 50-58.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Questions About The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

During a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing on March 16, Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), the ranking member of the committee, said that U.S. Strategic Command had failed to convince her that the United States needs to develop a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile; the LRSO (Long-Range Standoff missile).

“I recently met with Admiral Haney, the head of Strategic Command regarding the new nuclear cruise missile and its refurbished warhead. I came away unconvinced of the need for this weapon. The so-called improvements to this weapon seemed to be designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war. I find that a shocking concept. I think this is really unthinkable, especially when we hold conventional weapons superiority, which can meet adversaries’ efforts to escalate a conflict.”