Early next year the Obama administration, with eager backing from hardliners in Congress, is expected to commit the U.S. taxpayers to a bill of $20 billion to $30 billion for a new nuclear weapon the United States doesn’t need: the Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) air-launched cruise missile.

The new nuclear cruise missile will not be able to threaten targets that cannot be threatened with other existing nuclear weapons. And the Air Force is fielding thousands of new conventional cruise missiles that provide all the standoff capability needed to keep bombers out of harms way, shoot holes in enemy air-defenses, and destroy fixed and mobile soft, medium and hard targets with high accuracy – the same missions defense officials say the LRSO is needed for.

But cool-headed thinking about defense needs and priorities has flown out the window. Instead the Obama administration appears to have been seduced (or sedated) by an army of lobbyists from the defense industry, nuclear laboratories, the Air Force, U.S. Strategic Command, defense hawks in Congressional committees, and academic Cold Warriors, who all have financial, institutional, career, or political interests in getting approval of the new nuclear cruise missile.

LRSO proponents argue for the new nuclear cruise missile as if we were back in the late-1970s when there were no long-range, highly accurate conventional cruise missiles. But that situation has changed so dramatically over the past three decades that advanced conventional weapons have now eroded the need for a nuclear cruise missile.

That reality presents President Obama with a unique opportunity: because the new nuclear cruise missile is redundant for deterrence and unnecessary for warfighting requirements, it is the first opportunity for the administration to do what the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review, 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review, and 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy all called for: use advanced conventional weapons to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy.

Muddled Mission Claims

Defense officials have made a wide range of claims for why a new nuclear cruise missile is needed, ranging from tactical use against air-defense systems, rapid re-alerting, generic deterrence, escalation-control, to we-need-a-new-one-because-we-have-an-old-one. In a letter to the Senate Appropriations Committee in 2014, Nuclear Weapons Council chairman Frank Kendall provided one of the most authoritative – and interesting – justifications. After reminding the lawmakers that DOD “has an established military requirement for a nuclear capable stand-off cruise missile for the bomber leg of the U.S. Triad,” Kendall further explained:

Nuclear capable bombers with effective stand-off weapons assure our allies and provide a unique and important dimension of U.S. nuclear deterrence in the face of increasingly sophisticated adversary air defenses. The bomber’s stand-off capability with a modern cruise missile will provide a credible capability to penetrate advanced air defenses with multiple weapons attacking from multiple azimuths. Beyond deterrence, an LRSO-armed bomber force provides the President with uniquely flexible options in an extreme crisis, particularly the ability to signal intent and control escalation, long-standing core elements of U.S. nuclear strategy.

Nuclear Weapons Chair Frank Kendall says the LRSO is needed for deterrence and warfighting missions

The “Beyond deterrence” wording is interesting because it suggests that what precedes it is about deterrence and what follows it is not. It essentially says that flying around with bombers with nuclear cruise missiles that can shoot through air-defense systems will deter adversaries (and assure Allies), but if it doesn’t then firing all those nuclear cruise missiles will give the President lots of options to blow things up. And that should calm things down.

But this is where the LRSO mission gets muddled. Because although nuclear cruise missiles could potentially penetrate those air-defenses, so can conventional cruise missiles to hold at risk the same targets. And because it would be much harder for the President to authorize use of nuclear cruise missiles, he would in reality have considerably fewer options with the LRSO than with conventional cruise missiles.

The “options” that Kendall referred to are essentially just different ways to blow up facilities that U.S. planners have decided are important to the adversary. Yet LRSO provides no “unique” capability to blow up a target that cannot be done by existing or planned conventional long-range cruise missiles or, to the limited extent a nuclear warhead is needed to do the job, by other nuclear weapons such as ICBMs, SLBMs, or gravity bombs.

So what’s missing from the LRSO mission justification is why it would matter to an adversary that the United States would not blow up his facilities with nuclear cruise missiles but instead with conventional cruise missiles or other nuclear weapons. And why would it matter so much that the adversary would conclude: “Aha, the United States does not have a nuclear cruise missile, only thousands of very accurate conventional cruise missiles, hundreds of long-range ballistic missiles with thousands of nuclear warheads, and five dozen stealthy bombers with B61-12 guided nuclear bombs that can and will damage my forces or destroy my country. Now is my chance to attack!”

Some defense leaders confuse the need for the nuclear LRSO with broader defense requirements, as illustrated by this statement reportedly made by STRATCOM commander Adm. Haney at the Army & Navy Club in 2014.

A favorite phrase for defense officials these days is that nuclear weapons, including a new air-launched cruise missile, are needed to “convince adversaries they cannot escalate their way out of a failed conflict, and that restraint is a better option.” The scenario behind this statement is that an aggressor, for example Russia attacking a NATO country with conventional forces, is pushed back by superior U.S. conventional forces and therefore considers escalating to limited use of nuclear weapons to defeat U.S. forces or compel the United States to cease its counterattack on Russian forces.

Unless the United States has flexible regional nuclear forces such as the LRSO that can be used in a limited fashion similar to the aggressor’s escalation, so the thinking goes, the United States might be self-deterred from using more powerful strategic weapons in response, incapable of responding “in kind,” and thus fail to de-escalate the conflict on terms favorable to the United States and its Allies. Therefore, some analysts have begun to argue (here and here), the United States needs to develop nuclear weapons that have lower yields and appear more useable for limited scenarios.

The argument has an appealing logic – the same dangerous logic that fueled the Cold War for four decades. It carries with it the potential of worsening the very situation it purports to counter by increasing reliance on nuclear weapons and further stimulating development of regional nuclear warfighting scenarios. While promising to reduce the risk of nuclear use, the result would likely be the opposite.

It also ignores that existing U.S. nuclear forces already have considerable regional flexibility, yield variations, and are getting even better. And it glosses over the fact that U.S. military planners over the past three decades, while fully aware of modernizations in nuclear adversaries and a significant disparity with Russian non-strategic nuclear forces, nonetheless have continued to unilaterally eliminate all land- and sea-based non-strategic nuclear forces that used to serve many of the missions the advocates now say require more regionally tailored nuclear weapons.

Some senior defense officials have also started linking the LRSO justification to recent Russian behavior. Brian McKeon, the Pentagon’s principal deputy defense under secretary for policy, told Congress earlier this month that the Pentagon is “investing in technologies that will be most relevant to Russia’s provocations,” including “the long-range bomber, the new long-range standoff cruise missile…”

Last Time The Air Force Wanted A New Nuclear Cruise Missile…

Such advocacy for the LRSO is like playing a recording from the 1970s when defense officials were urging Congress to pay for nuclear cruise missiles. Back then the justifications were the same: provide bombers with standoff capability, shoot holes in air-defense systems, and provide the President with flexible regional options to hold targets at risk that are important to the adversary. And just as today, many of the justification were not essential or exaggerated.

With a range of more than 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles), the Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM; AGM-86B) was seen as the answer to protecting bombers by holding targets at risk from well beyond the reach of Soviet advanced air-defense systems. After the first test flights in 1979, the ALCM became operational in December 1982 and more than 1,700 ALCMs were produced between 1980 and 1986. But a need for a long-range cruise missile that could actually be used in the real world soon resulted in conversion of hundreds of the ALCMs to conventional CALCMs (AGM-86C) that have since been used in half a dozen wars.

Billions were spent on the nuclear Advanced Cruise Missile for capabilities that had little operational significance. The weapon was retired in 2008.

No sooner had the ALCM entered service before the Air Force started saying the more capable Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM; AGM-129A) was needed: Soviet advanced air-defense systems expected in the 1990s would be able to destroy the ALCMs and the bombers carrying them. Sounds familiar? The initial plan was to produce 2,000 ACMs but the program was cut back to 460 missiles that were produced between 1990 and 1993.

The Air Force described the ACM as a “subsonic, low-observable air-to-surface strategic nuclear missile with significant range, accuracy, and survivability improvements over the ALCM.” And the missile had specifically been “designed to evade air and ground-based defenses in order to strike heavily defended, hardened targets at any location within an enemy’s territory.” A fact sheet on the Air Force’s web site still describes the unique capabilities:

When the threat is deep and heavily defended, the AGM-129A delivers the proven effectiveness of a cruise missile enhanced by stealth technology. Launched in quantities against enemy targets, the ACM’s difficulty to detect, flight characteristics and range result in high probability that enemy targets will be eliminated.

The AGM-129A’s external shape is optimized for low observables characteristics and includes forward swept wings and control surfaces, a flush air intake and a flat exhaust. These, combined with radar-absorbing material and several other features, result in a missile that is virtually impossible to detect on radar.

The AGM-129A offers improved flexibility in target selection over other cruise missiles. Missiles are guided using a combination of inertial navigation and terrain contour matching enhanced with highly accurate speed updates provided by a laser Doppler velocimeter. These, combined with small size, low-altitude flight capability and a highly efficient fuel control system, give the United States a lethal deterrent capability well into the 21st century.

Yet only 17 months after the ACM first become operational in January 1991, a classified GAO review concluded that “the range requirement for [the] ACM offers only a small improvement over the older ALCM and that the accuracy improvement offered does not appear to have real operational significance.”

Even so, ACM production continued for another year and the Air Force kept the missile in the arsenal for another decade-and-a-half. Finally, in 2008, after more than $6 billion spent on developing, producing, and deploying the missile, the ACM was unilaterally retired by the Bush administration. Although not until after a dramatic breakdown of Air Force nuclear command and control in August 2007 resulted in six ACMs with warheads installed being flown on a B-52 across the United States without the Air Force knowing about it.

It is somewhat ironic that after the ACM was retired, the Air Force official who was given the ceremonial honor to crush the last of the unneeded missiles was none other than Brig. Gen. Garrett Harencak, then commander of the Nuclear Weapons Center at Kirtland AFB. The following year Harencak was promoted to Maj. Gen. and Assistant Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration (A-10) at the Pentagon where he became a staunch and sometimes bombastic advocate for the LRSO. Harencak has since been “promoted” to commander of the Air Force Recruiting Service in Texas.

The last Advanced Cruise Missile is destroyed by Brig. Gen. Jarrett Harencak in 2012, then commander of the Nuclear Weapons Center at Kirtland AFB, before he became a primary Air Force advocate for the LRSO.

JASSM-ER: Deterrence Without “N”

The ALCM and ACM were acquired in a different age. LRSO advocates appear to argue for the weapon as if they were still back in the 1970s when the military didn’t have long-range conventional cruise missiles.

Today it does and those conventional weapons are getting so effective, so numerous, and so widely deployed that they can hold at risk the same targets and fulfill the same targeting missions that advocates say the LRSO is needed for. Moreover, the conventional missiles can do the mission without radioactive fallout or the political consequences from nuclear use that would limit any President’s options.

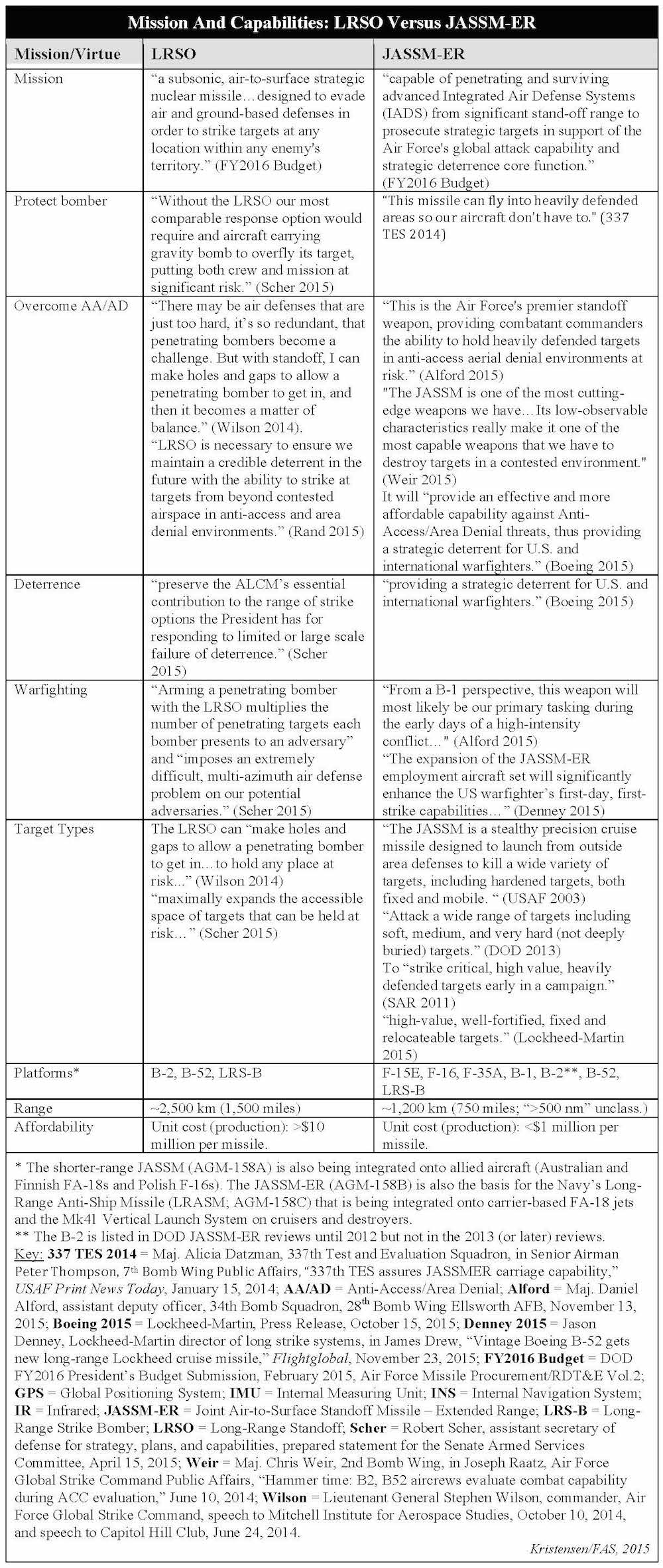

Curiously, defense officials use very similar descriptions when they describe the missions and virtues of the nuclear LRSO and the new conventional long-range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM-ER; AGM-158B). In many cases one could swap the names and you wouldn’t know the difference. The LRSO seems to offer no unique or essential capabilities that the JASSM-ER cannot provide:

2015 LRSO Mission Capabilities

The Pentagon describes the JASSM as a next-generation cruise missile “enabling the United States Air Force (USAF) to destroy the enemy’s war-sustaining capabilities from outside its area air defenses. It is precise, lethal, survivable, flexible, and adverse-weather capable.” Armed with a 1000-pound class, hardened, penetrating warhead with a robust blast fragmentation capability, the JASSM’s “inherent accuracy” (3 meters or less using the Imaging Infrared seeker and less than 13 meters with GPS/INS guidance only) “reduces the number of weapons and sorties required to destroy a target.”

The concept of operations (CONOPS) for JASSM states “employment will occur primarily in the early stages of conflict before air superiority is established, and in the later stages of conflict against high value targets remaining heavily defended. JASSM can also be employed in those cases where, due to rules of engagement/political constraints, high value, point targets must be attacked from international airspace. JASSM may be employed independently or the missile may be used as part of a composite package.”

Full-scale production of the JASSM-ER was authorized in 2014 and the weapon is already deployed on B-1 bombers, each of which can carry 24 missiles – more than the maximum number of ALCMs carried on a B-52H. Over the next decade JASSM-ER will be integrated on nearly all primary strategic and tactical aircraft – including the B-52H. Operational units equipped with the missile will, according to DOD, employ the JASSM-ER against high-value or highly defended targets from outside the lethal range of many threats in order to:

- Destroy targets with minimal risk to flight crews and support air dominance in the theater;

- Strike a variety of targets greater than 500 miles away;

- Execute missions using automated preplanning or manual pre-launch retargeting planning;

- Attack a wide range of targets including soft, medium, and very hard (not deeply buried) targets.

The new long-range JASSM-ER standoff cruise missile is already operational on the B-1 bombers (seen here in 2014 drop-test) and will be added to nearly all bombers and fighter-bombers. A sea-based version will also have land-attack capabilities. A shorter-range version (AGM-158A) is being sold to European and Pacific allies.

Says Kenneth Brandy, the JASSM-ER test director at the 337th Test and Evaluation Squadron: “While other long range weapons may have the capability of reaching targets within the same range, they are not as survivable as the low observable JASSM-ER…The stealth design of the missile allows it to survive through high-threat, well-defended enemy airspace. The B-1’s effectiveness is increased because high-priority targets deeper into heavily defended areas are now vulnerable.”

Indeed, the JASSM-ER is “specifically designed to penetrate air defense systems,” according to the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The JASSM-ER is already now being integrated into STRATCOM’s global strike exercises alongside nuclear weapons. During the Global Lightning exercise in May 2014, for example, B-52s at Barksdale AFB loaded JASSM-ER (see below). And in September 2015, two JASSM-ER equipped B-1 bomb wings were transferred from Air Combat Command (ACC) to Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC) control to operate more closely alongside the nuclear B-2 and B-52H bombers in long-range strike operations.

A JASSM-ER is loaded onto the wing pylon of a B-52H bomber at Barksdale AFB during STRATCOM’s Global Lightning exercise in May 2014.

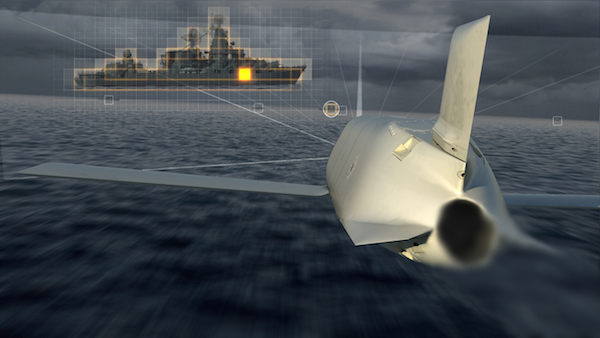

As if the Air Force’s JASSM-ER were not enough, the missile is also being converted into a naval long-range anti-ship cruise missile known as LRASM (Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile; AGM-158C) that in addition to sinking ships will also have land-attack capabilities. The LRASM will be launched from the Mk41 Vertical Launch System on cruisers and destroyers and is also being integrated onto B-1 bombers and carrier-based FA-18 aircraft.

In case anyone doubts who the target is, this Lockheed-Martin illustration shows the LRASM honing in on a Russian Slava-class cruiser.

A Clear Pledge To Reduce Nuclear Role

The considerable standoff targeting capabilities offered by the JASSM-ER and LRASM, as well as the Navy’s existing Tactical Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile, and the enhanced deterrence capability they provide fit well with U.S. policy to use advanced conventional weapons to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons in regional scenarios.

The intent to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons has been clearly stated in key defense planning documents issued by the administration over the past five years: the February 2012 Ballistic Missile Defense Review, the February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review, the April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, and the June 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy.

According to the February 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review Report, “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

The February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review explained further that “new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent…make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (Emphasis added.)

The April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report added more texture by stating that, while nuclear weapons are still as important, “fundamental changes in the international security environment in recent years – including the growth of unrivaled U.S. conventional military capabilities, major improvements in missile defenses, and the easing of Cold War rivalries – enable us to fulfill those objectives at significantly lower nuclear force levels and with reduced reliance on nuclear weapons. Therefore, without jeopardizing our traditional deterrence and reassurance goals, we are now able to shape our nuclear weapons policies and force structure in ways that will better enable us to meet today’s most pressing security challenges.” (Emphasis added.)

Most recently, in June 2013, the Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United State “narrows U.S. nuclear strategy to focus on only those objectives and missions that are necessary for deterrence in the 21st century,” and in doing so, “takes further steps toward reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our security strategy.” The guidance directs the Department of Defense “to strengthen non-nuclear capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks,” and specifically “to conduct deliberate planning for non-nuclear strike options to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options, and to propose possible means to make these objectives and effects achievable.” (Emphasis added.)

The Employment Strategy emphasizes that, “Although they are not a substitute for nuclear weapons, planning for non-nuclear strike options is a central part of reducing the role of nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added.)

The pledge to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons has not risen from a naive unilateral nuclear disarmament gesture but as a consequence of decades of revolutionary advancement of conventional weapons. Those non-nuclear strike capabilities have increased even further since the NPR and the employment guidance were published and will increase even more in the decades ahead as the JASSM-ER and LRASM are integrated onto more and more platforms.

Conclusions and Recommendations

President Obama is facing a crucial decision: whether to approve or cancel the Air Force’s new Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) nuclear air-launched cruise missile. The decision will be his last chance as president to demonstrate that the United States is serious about reducing the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons in its defense strategy.

The President’s decision will also have to take into consideration whether the administration is serious about the pledge it made in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report, that “Life Extension Programs (LEPs)…will not…provide for new military capabilities.” The LRSO will most certainly have new military capabilities compared with the ALCM it is intended to replace.

In their arguments for why the President should approve the LRSO, proponents have so far not presented a single mission that cannot be performed by advanced conventional weapons or other nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal.

Indeed, a review of many dozens of official statements, documents, a news media articles revealed that proponents argue for the LRSO as if they were back in the late-1970s arguing for the ALCM at a time when conventional long-range cruise missiles did not exist. As a result, LRSO proponents confuse the need for a standoff capability with the need for a nuclear standoff capability.

Yet in the more than three decades that have passed since the ALCM was approved, a revolution in non-nuclear military technology has produced a wide range of conventional weapons and strategic effects capabilities that can now do many of the targeting missions that nuclear weapons previously served. Indeed, the Navy and Army have already retired all their non-strategic nuclear weapons and today rely on conventional weapons for those missions.

Now it’s the Air Force’s turn; advanced conventional cruise missiles can now serve the role that nuclear air-launched cruise missiles used to serve: hold at risk heavily defended strategic and tactical targets at a range far beyond the reach of modern and anticipated air-defense systems. The Navy already has its Tactical Tomahawk widely deployed on ships and submarines, and now the Air Force is following with deployment of thousands of long-range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM-ER) on bombers and fighter-bombers. The conventional missiles will in fact provide the President with more (and better) options than he has with a nuclear air-launched cruise missile; it will be a more credible deterrent.

This reality seems to not exist for LRSO advocates who argue from a point of doctrine instead of strategy. And for some the obsession with getting the nuclear cruise missile appears to have become more important than the mission itself. STRATCOM commander Adm. Cecil Haney reportedly argued recently that getting the LRSO “is just as important as having a future bomber.” It is perhaps understandable that a defense contractor can get too greedy but defense officials need to get their priorities straight.

The President needs to cut through the LRSO sales pitch and do what the NPR and employment guidance call for: reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons by canceling the LRSO and instead focus bomber standoff strike capabilities on conventional cruise missiles. Doing so will neither unilaterally disarm the United States, undermine the nuclear Triad, nor abandon the Allies.

Now is your chance Mr. President – otherwise what was all the talk about reducing the role of nuclear weapons for?

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country.

Nearly one year after the Pentagon certified the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program to continue after it incurred critical cost and schedule overruns, the new nuclear missile could once again be in trouble.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end”

Without information, without factual information, you can’t act. You can’t relate to the world you live in. And so it’s super important for us to be able to monitor what’s happening around the world, analyze the material, and translate it into something that different audiences can understand.