The Aftermath: The Expiration of New START and What It Means For Us All

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

On February 5th, Axios reported that following overnight negotiations between the two sides, there remains a possibility for the two countries to continue observing the central limits after the Treaty’s expiry, although it did not state whether such an arrangement would include verification, and also noted that it had not been agreed to by either President.

If the two sides cannot reach an agreement, we face a world of heightened nuclear competition fueled by worst-case planning and nuclear expansion, fewer transparency mechanisms, and deepening mistrust among nations with the world’s most powerful weapons. Addressing these challenges in the new nuclear era will require creative and nontraditional approaches to risk reduction and arms control.

How did we get here?

Even if the two sides manage to negotiate a last-minute band-aid arrangement, the fact that we have no long-term arms control solution ready to take New START’s place is the culmination of years of breakdown in diplomacy and arms control efforts. New START entered into force on February 5th, 2011, with a 10-year duration and the option to extend it for five additional years. Leading up to the treaty’s original expiration date in 2021, there was serious concern that the United States and Russia would not come to an agreement on extension. For the first three years of his first administration, President Donald Trump engaged in few constructive arms control discussions with Russia. Then, in the final months of 2020, he proposed a short-term extension contingent on Russia agreeing to new verification measures and a warhead freeze, which Russia rejected. At the 11th hour, just two weeks after his inauguration, President Joe Biden agreed to a full five-year extension of the treaty with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The shaky status of New START further deteriorated in early 2023 when Putin announced that Russia was “suspending” its participation in the treaty, stipulating that resumption would require the United States to end its support for Ukraine, and that arms control talks would also have to involve France and the United Kingdom. As part of its suspension, Russia halted its exchanges of data, notifications, and telemetry information, and the United States subsequently followed suit with reciprocal countermeasures.

It is important to note that although the United States found Russia’s actions to constitute noncompliance with the treaty’s requirements, successive State Department reports following Russia’s suspension assessed that “Russia did not engage in any large-scale activity above the Treaty limits.” The 2024 compliance report, however, stated that “Russia was probably close to the deployed warhead limit during much of the year and may have exceeded the deployed warhead limit by a small number during portions of 2024.”

Ultimately, over years of growing tensions and mistrust between the two countries, the United States and Russia have barely managed to see New START through to its expiration, much less engage in talks for a new treaty to take its place. In September 2025, the Kremlin stated that “Russia is prepared to continue observing the treaty’s central quantitative restrictions for one year after February 5, 2026,” without verification. President Trump told a reporter that the proposal “sounds like a good idea to me,” but apparently did not respond to the proposal before the treaty’s deadline expired.

In addition to the worsening U.S.-Russia relationship, funding cuts at the U.S. Department of State, the Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation office at the NNSA, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence mean less investment in and capacity for executing a follow-on agreement, even if the political environment allowed for it.

What could this mean for nuclear forces?

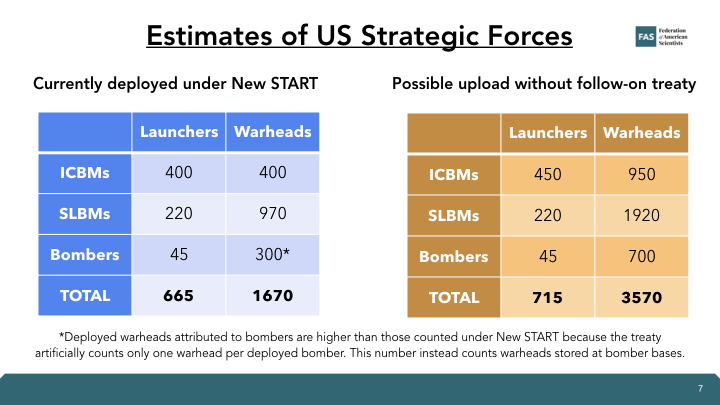

New START placed limits on the number of strategic nuclear weapons that each country could possess and deploy: each side could deploy up to 1,550 warheads and 700 launchers, and could possess up to 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers. Incorporating a limit on non-deployed launchers was intended to prevent either country from “breaking out” or quickly expanding deployed numbers beyond the treaty limits.

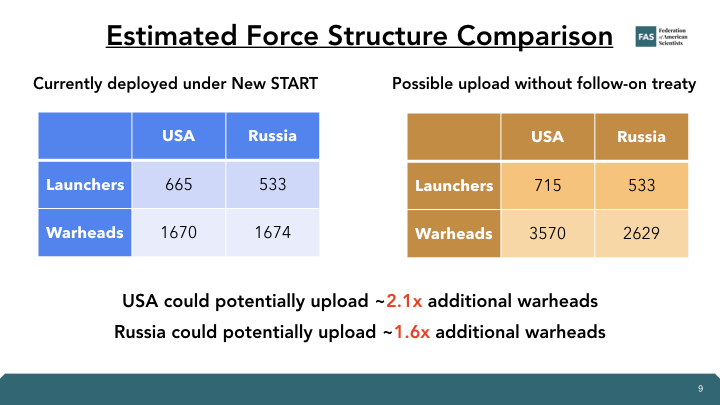

Over the past 15 years, the treaty restraints and respective modernization plans resulted in significant force reductions in Russia and the United States. Both countries have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that neither will exceed the force levels currently dictated by New START. In the absence of an official agreement following New START’s expiration, however, both countries will likely default to mutual distrust and worst-case thinking about how their arsenals will grow in the future. This is a serious concern, considering both countries possess significant warhead upload capacity that would allow them to increase their deployed nuclear forces relatively quickly.

This kind of thinking has already been displayed by members of the House Armed Services Committee who, in 2023, called Biden’s agreement to extend New START “naive” and argued that Russia “cannot be trusted,” saying “if these agreements cannot be enforced, then they do nothing to enhance U.S. security, and serve only to undermine it.” Defense hawks in Congress and outside argued instead for upgrades and expansions to the U.S. nuclear force; the bipartisan Congressional Commission on the U.S. Strategic Posture in late-2023 recommended a broad range of options to expand the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The Biden administration also appeared to lay the groundwork for potential options to expand its deployed nuclear force following the end of New START: in June 2024, Pranay Vaddi, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Arms Control, Disarmament, and Nonproliferation at the National Security Council, stated that “Absent a change in the trajectory of adversary arsenals, we may reach a point in the coming years where an increase from current deployed numbers is required. And we need to be fully prepared to execute if the President makes that decision—if he makes that decision.” The Biden administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy published in 2024, however, did not direct an increase of U.S. deployed nuclear forces, effectively leaving that decision to the Trump administration.

If the United States decided to increase its deployed strategic forces, there are measures it could take to rapidly upload reserve warheads, while other options will take more time. For example, all 400 deployed U.S. ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, but about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that could be uploaded to carry three warheads each if necessary. An additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos could also be reloaded with missiles, though this process would likely take several years. With these potential additions in mind, the U.S. ICBM force could possibly double from 400 warheads to up to a maximum of 800 warheads. In any case, executing such an upload across the entirety of the ICBM force would require significant resources, manpower, and time—none of which the United States has in excess, given existing constraints on its already-delayed nuclear modernization program.

Increasing the warhead loading on U.S. ballistic missile submarines could be done faster than uploading the ICBM force. Each missile on the submarines currently carries an average of four or five warheads, a number that can be increased to eight. Doing so could theoretically add 800 to 900 warheads to the submarine force, but loading each missiles with the maximum number of warheads onto each missile (and by extension, each submarine) would dramatically limit the submarine force’s targeting flexibility, as war planners will not want to lock themselves into a situation in which submarine crews would be forced to fire the maximum number of warheads, rather than having a range of more limited options at their disposal. As a result, executing an upload across the submarine force could more realistically result in an increase of approximately 400 to 500 additional warheads. Doing so would take many months, given that each ballistic missile submarine would have to return to port on a rotating schedule in order to load the additional warheads. In addition, the United States has the option to reopen the four launch tubes on each ballistic missile submarine that had been converted to non-nuclear status for New START compliance, and the July 2025 “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” provided $62 million for conversion activities to take place after March 1st, 2026; however, doing so would need to overcome significant internal opposition and would likely take several months, if not years, to complete.

The quickest way for the United States to increase deployed nuclear warheads would be to load nuclear cruise missiles and bombs onto its long-range B-2 and B-52 bombers. The bombers were taken off alert and their nuclear weapons placed in storage in 1992, but hundreds of the weapons are stored at the bomber bases and could be loaded within days or weeks; additional weapons could be brought in from central storage depots. Up to 800 nuclear weapons are estimated to be available for the bombers. Yet loading live nuclear weapons onto bombers would significantly increase the vulnerability of the weapons to accidents and terrorist attacks.

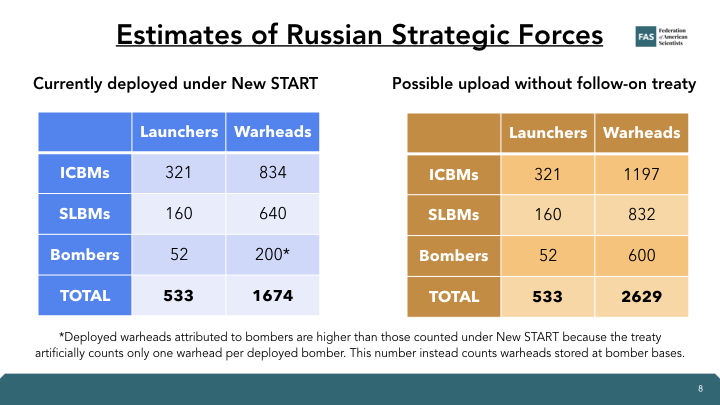

Russia also has a significant warhead upload capacity, particularly for its ICBMs, but is subject to similar constraints as the United States. Several of Russia’s existing ICBMs are thought to have been downloaded to a smaller number of warheads than their maximum capacities in order to meet the New START force limits. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase by approximately 400 warheads.

Warheads on missiles onboard some of Russia’s SSBNs are also thought to have been reduced to a lower number to meet New START limits. Without treaty limitations, the number of deployed warheads could potentially be increased by 200-300 warheads, perhaps more in the future, although this number could be tempered by a desire for increased targeting flexibility, in a similar manner to the United States.

While also uncertain, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons, similarly to the United States.

Ultimately, if both countries chose to upload their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals could nearly double in size. While a maximum upload is highly unlikely, it is possible we will see immediate measures taken to upload certain systems, followed by gradual increases in other areas over the next few years. While defense hawks in Russia and the United States claim that more nuclear weapons are needed for national security, doing so would inevitably result in each country being targeted by hundreds of additional nuclear weapons.

Moreover, without the transparency and predictability that resulted from the verification regime and regular data exchanges stipulated under New START, nuclear uncertainty—and potentially confusion and misunderstandings—will increase. Russian and U.S. planners will rely more on worst-case scenarios in their nuclear programs, and both countries are likely to invest more in what they perceive will demonstrate resolve and increase their overall security, including nonstrategic nuclear forces, conventional forces, cyber and AI capabilities, and missile defense. These moves could also trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states, possibly leading to an increase in their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. China has already decided to increase its nuclear arsenal to better be able to counter what it perceives is a growing threat from other military powers; Beijing rejects numerical limits on its nuclear arsenal and increasing U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenal will make it harder to change its mind.

Re-imagining the future: The end of fully “compartmentalized” arms control?

The future of arms control is certainly not dead, but it is likely entering a new era. For decades, the United States and Russia pursued arms control negotiations in isolation from other security issues, emphasizing that the unique destructiveness of nuclear weapons requires that the topic be segregated. Although such negotiations were never completely disentangled from politics or other geopolitical events—as demonstrated, for example, by the refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify SALT II after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—this approach was largely successful as a framework for arms control during and immediately after the Cold War.

This fully compartmentalized approach, however, is likely no longer an option in a post-New START world. Russia has made it clear through both its actions—particularly its suspension of its treaty obligations primarily due to U.S. support for Ukraine—and its rhetoric that it will no longer engage in arms control negotiations absent a broader reboot of U.S.-Russia relations. And officials in the United States increasingly argue that bilateral nuclear limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals do not take into account the growing Chinese nuclear arsenal.

On February 3rd, Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov stated that in order to engage in strategic stability dialogue, “We need far-reaching shifts, changes for the better in the US approach to relations with us as a whole.” On numerous prior occasions, he had critiqued the United States’ approach to arms control: in 2023, he told TASS that Moscow cannot “discuss arms control issues in the mode of so-called compartmentalization, which means singling out from the whole range of issues some pressing ones which are of interest to the United States, and pushing to oblivion or taking off the table other points that are theoretically as important to Russia as those of interest to the Americans.”

It would appear that China thinks about arms control in a similar way. In 2024, China suspended strategic stability talks with the United States in response to U.S. arms sales to Taiwan and increased trade restrictions on China. A spokesperson from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized that in order to bring China to the table, the United States “must respect China’s core interests and create [the] necessary conditions for dialogue and exchange.” On February 5th, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian reiterated that “China’s nuclear strength is by no means at the same level with that of the U.S. or Russia. Thus, China will not take part in nuclear disarmament negotiations for the time-being.” Even if it were possible to change China’s opposition to numerical limits on nuclear forces and join the arms control process, it is not clear what the United States would actually be willing to limit or give up in return for Chinese concessions. One such possibility would be the more ambitious and fantastical elements of Golden Dome, as a multi-layered, space-based missile shield is fundamentally incompatible with the idea of accepted mutual vulnerability.

Re-imagining the future: verification without on-site inspections?

Traditional nuclear arms control, including New START, relies on the availability of on-site inspections to verify compliance. Absent a significant shift in geopolitical relations, however, it is implausible to imagine some combination of American, Russian, or Chinese inspectors roaming around each other’s territories anytime in the near future. As a result, the next generation of arms control agreements faces a clear challenge: how can countries verify that the other remains in compliance when the political reality prohibits on-site inspections?

Traditionally, countries have used “National Technical Means”—a term used to describe classified means of data collection, such as remote sensing and telemetry intelligence—to verify compliance with arms control agreements. NTMs are used as a complement to other sources of verification, including on-site inspections, data exchanges and notifications, and the exchange of telemetric information. Despite on-site inspections and formal data exchange being preferable, NTMs can be very capable; for example, the U.S. assessment that Russia might briefly have exceeded the New START warhead limit was based on NTMs, not on-site verification.

Given the political implausibility of on-site inspections forming part of a future verification regime, one of the authors has recently co-authored a report with Igor Morić from Princeton’s Science & Global Security Program on the possibility of a future arms control arrangement based around “Cooperative Technical Means.” Under such an arrangement, it could be possible for states to use national or commercial remote sensing tools to monitor each other’s nuclear capabilities, verify the numbers of fixed and mobile ICBM and SLBM launchers, as well as track the number and location of their heavy bombers. For a more detailed explanation, the full report can be accessed here.

What Now?

As Axios’ reporting indicates, everything could change in a day, for better or for worse. Countries could take unilateral measures to either exercise restraint or refuse cooperation. Specifically, it is important that each side refrain from significant increases in its nuclear arsenal regardless of whether a new arrangement is concluded; such steps will almost inevitably increase the competition dynamic that would result in an arms race.

It is also imperative that the United States and Russia commit to engaging in arms control as a means of reducing the risk of nuclear use, whether intentional or by accident or misinterpretation. The United States, in particular, should reinvest in and reprioritize diplomacy and nonproliferation to prepare for and signal an intention to re-engage in arms control dialogues.

While new technology and creative approaches offer potential solutions to issues plaguing past arms control arrangements, progress will still require political will and motivation from both sides.

Here at FAS, we will continue to track the nuclear force status and modernization programs across the nine nuclear-armed states, paying close attention to cost and schedule overruns that relentlessly plague many of these efforts. In an era where nuclear transparency and access to reliable, public information are declining, we believe our work is more critical now than ever before.

Additional work from us on this topic:

- After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

- If Arms Control Collapses, US and Russian Strategic Nuclear Arsenals Could Double In Size

- Inspections Without Inspectors: A Path Forward for Nuclear Arms Control Verification with “Cooperative Technical Means”

- The Long View: Strategic Arms Control After the New START Treaty

- 2025 Russia Nuclear Notebook

- 2025 United States Nuclear Notebook

- For all Nuclear Notebooks, see here

The Nuclear Information Project is currently supported with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

The Pentagon’s (Slimmed Down) 2025 China Military Power Report

On Tuesday, December 23rd, the Department of Defense released its annual congressionally-mandated report on China’s military developments, also known as the “China Military Power Report,” or “CMPR.” The report is typically a valuable injection of information into the open source landscape, and represents a useful barometer for how the Pentagon assesses both the intentions and capabilities of its nuclear-armed competitor.

This year’s report, and particularly the nuclear section, is noticeably slimmed down relative to previous years; however, this is because the format of the report has changed to focus on newer information, rather than repeating and reaffirming older assessments. As a result, this year’s report includes no mention of China’s ballistic missile submarines and their associated missiles, and includes only cursory mention of China’s air-based nuclear capabilities. It also excludes analyses of several types of land-based missiles entirely. However, this does not reflect changed assessments on the part of the Pentagon, but rather a lack of new information to report. Going forward, this means that analysts will need to read multiple years of CMPR reports in order to ensure that they are accessing the complete range of available information.

In addition, this year’s CMPR did not include any mention of China’s September 2025 Victory Day parade––which featured multiple new weapon systems––as the parade took place too recently; it will very likely be analyzed in next year’s report. The maps of missile base and brigade locations also appear to be out of date: the information is listed as “current as of 04/01/2024.”

While this year’s report did not include any earth-shattering headlines with regards to China’s nuclear forces, it provides additional context and useful perspectives on various events that took place over the past 12 months.

Stockpile growth

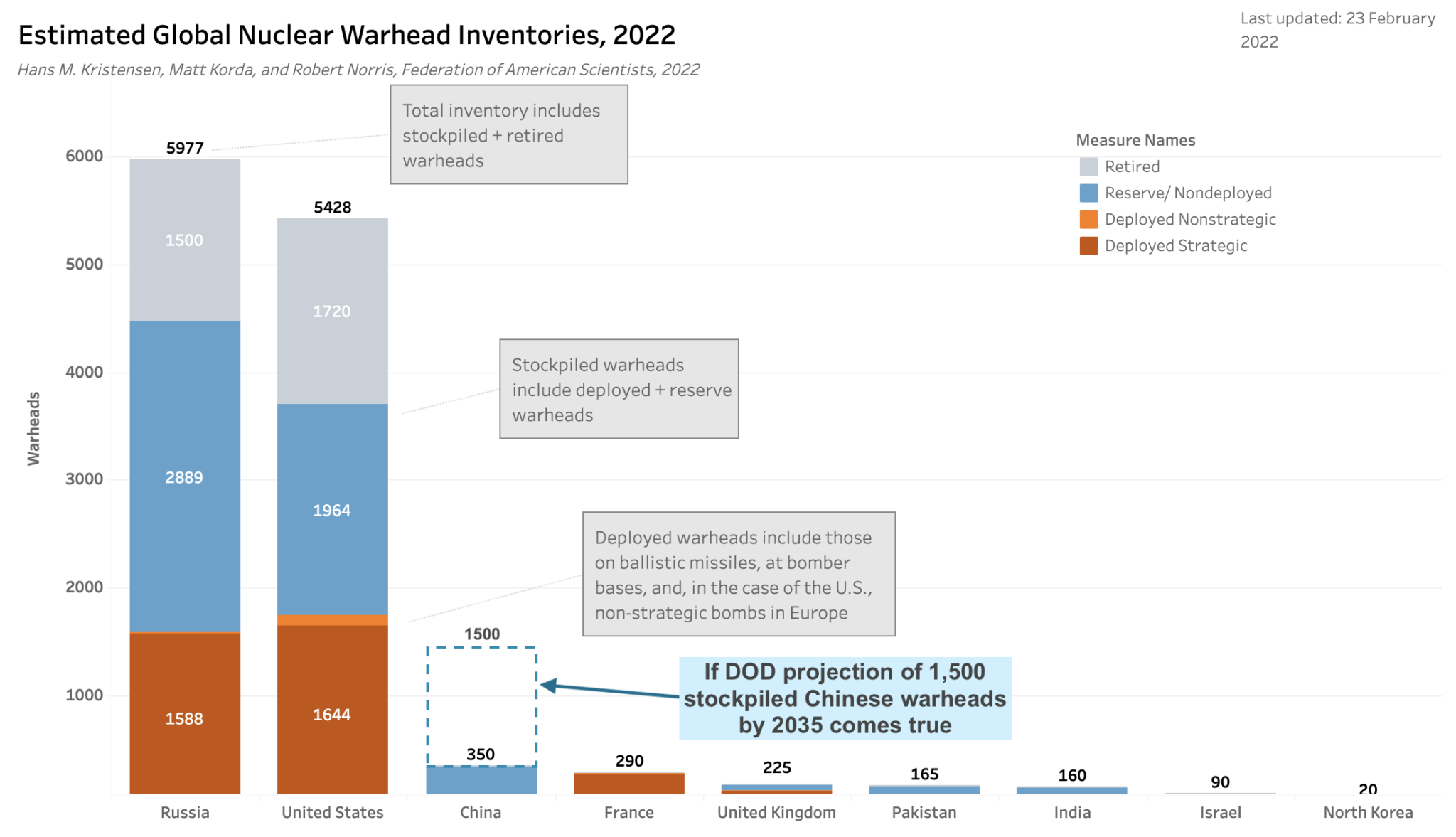

The CMPR states that China’s nuclear stockpile “remained in the low 600s through 2024, reflecting a slower rate of production when compared to previous years.” However, it reaffirmed previous years’ assessments that China “remains on track to have over 1,000 warheads by 2030.” China’s nuclear expansion over the past five years is now making this projection increasingly plausible, although even if it came to pass, China would still maintain several thousand warheads fewer than either the United States or Russia. Previous CMPRs had assessed that if China’s modernization pace continued, it would likely field a stockpile of about 1,500 warheads by 2035; however, this assessment has not been included in the CMPR since the 2022 iteration.

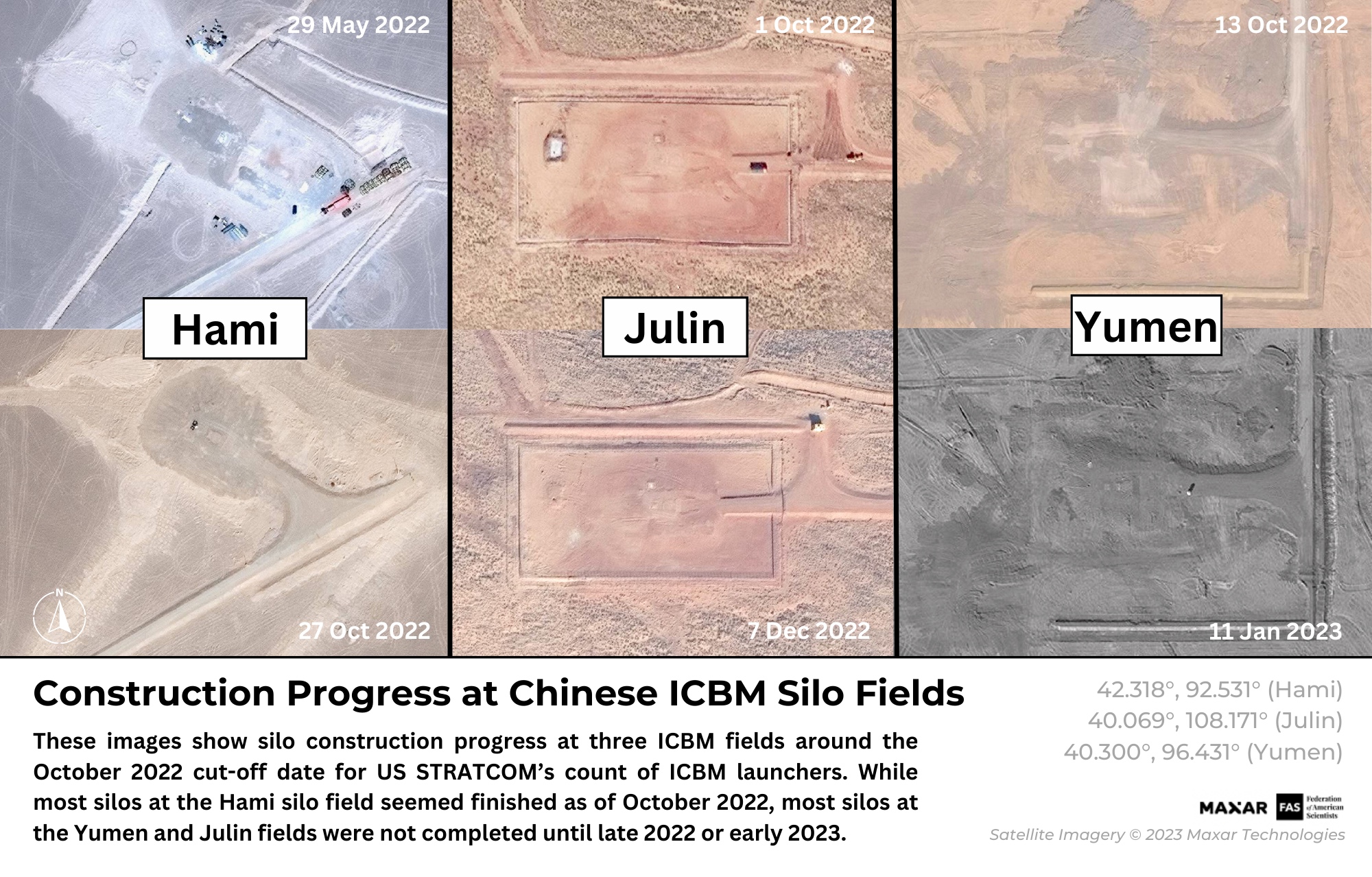

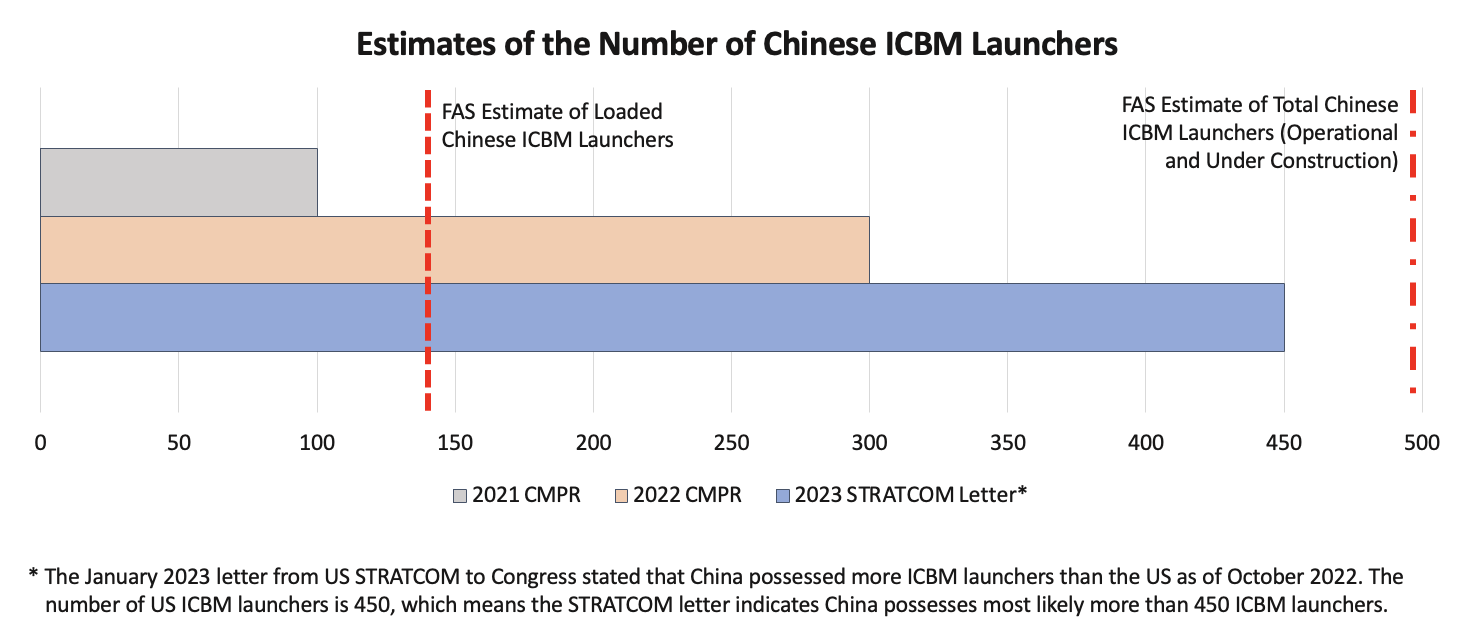

The dramatic expansion of China’s stockpile is primarily being prompted by the large-scale development and modernization of China’s next-generation intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) forces. In 2021, multiple non-governmental organizations (including our team at the Federation of American Scientists) publicly revealed the existence of three new ICBM silo fields capable of hosting up to 320 launchers for solid-propellant DF-31 class ICBMs. China is also more than doubling its number of silos for its liquid-fuel DF-5 class ICBMs, which the Pentagon assessed in its 2024 CMPR will likely yield about 50 modernized silos. Many of these missile types will be capable of carrying multiple warheads.

While the previous year’s CMPR indicated that China “has loaded at least some ICBMs into these silos,” the 2025 edition offers a valuable update: that China has now “likely loaded more than 100 solid-propellant ICBM missile silos at its three silo fields with DF-31 class ICBMs.” Our team continues to regularly monitor developments at the three silo fields using commercial satellite imagery and has not yet found sufficient evidence to corroborate this assessment; however, it is possible that the Pentagon’s assessment is primarily derived from other sources of intelligence, including human (HUMINT) and/or signals intelligence (SIGINT).

If China plans to continue its nuclear expansion, it will likely require additional fissile material, as China does not currently have the ability to produce large quantities of plutonium. The Pentagon assesses that China’s ongoing construction and planned commissioning of two new CFR-600 sodium-cooled fast breeder reactors at Xiapu “will reestablish China’s ability to produce weapons-grade plutonium.” However, the 2025 CMPR assesses that the first unit “is probably still undergoing testing,” and that “the second reactor unit is still under construction.” It is possible that this information is now out of date, as recent commercial satellite imagery now suggests that the first reactor unit may be operational.

Low-yield warheads

Previous editions of the CMPR had indicated that China was “probably” seeking low-yield warheads for escalation control during periods of small-scale nuclear crisis and/or conflict; however, the 2025 iteration is the first to offer an estimated yield value for such weapons, of “below 10 kilotons.” A recent technical history by Hui Zhang offers highly valuable data points for historical Chinese nuclear weapons tests, and suggests that China likely has the ability to produce smaller, low-yield warheads. Additionally, recent open-source reporting by Renny Babiarz with Open Nuclear Network (ONN) and researchers from the Verification Research Training and Information Center (VERTIC) found that China has been overhauling and expanding its warhead component manufacturing capabilities. Coupled with the expansion of the Lop Nur test site, this could indicate plans to upgrade China’s existing warheads, improve its ability to build more, or both.

The CMPR notes that the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) and the air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) carried by the H-6N bomber “are both highly precise theater weapons that would be well suited for delivering a low-yield nuclear weapon.” While the DF-26 had previously been identified as a likely carrier for a low-yield warhead, this is the first time that the H-6N’s ALBM has also been listed as a potential carrier.

Missile designations

It is often a complex endeavor to try and match China’s own missile designations to the names that are given to various systems by the Pentagon. This year’s CMPR, however, provides valuable confirmations for some of these missile designations. In particular, it confirms that both the DF-31A and DF-31AG ICBM are known to the Pentagon as CSS-10 Mod 2, which aligns with our understanding that both systems carry the same missile. It also strongly hints at the alignment between the CSS-18 and the DF-26 IRBM, as well as the CSS-10 Mod 3 and the DF-31B ICBM––a missile that was confirmed in the 2025 CMPR as the same missile that was launched from Hainan Island into the Pacific Ocean in September 2024 for the first time since 1980. This was the first mention of the DF-31B in the CMPR since the 2022 edition, and the first time that the missile’s existence under that designation has been confirmed.

The acknowledgement of the DF-31B’s existence coincides with the recent reveal of a likely silo-based version of the same missile during China’s September 2025 military parade. During that event, China unveiled a vehicle carrying a canister with the designation “DF-31BJ;” it is possible that the vehicle was a missile loader and the “J” likely indicates a silo basing mode, as the Chinese character “井” or “jing” means “well” and is used by the PLA to describe silos. We can therefore assume that the DF-31B ICBM has both a mobile and a silo basing mode, with the latter adding the J suffix to its designation.

Doctrinal shifts, arms control, and early warning

Beyond tweaks to China’s force posture and nuclear stockpile, the CMPR also offers some additional details with regards to its assessment of China’s nuclear doctrine. In particular, it expands on its previous assessments of China’s pursuit of an “early warning counterstrike (EWCS) capability,” which it calls “similar to launch on warning (LOW), where warning of a missile strike enables a counterstrike launch before an enemy first strike can detonate.” For the first time, the CMPR offers details into the capabilities of China’s early warning systems, stating that “China’s early warning infrared satellites [Tongxun Jishu Shiyan (TJS), also known as Huoyan-1] can reportedly detect an incoming ICBM within 90 seconds of launch with an early warning alert sent to a command center within three to four minutes.”

It also notes that China’s ground-based, large phased-array radars “probably can corroborate incoming missile alerts first detected by the TJS/Huoyan-1 and provide additional data, with the flow of early warning information probably enabling a command authority to launch a counterstrike before inbound detonation.” If this is accurate, it would appear that China is developing an early warning capability that functions in a similar manner to those of the United States and Russia, which rely on dual phenomenology to confirm the validity of incoming attacks before authorizing retaliatory launches.

The report also notes that “Beijing continues to demonstrate no appetite for pursuing […] more comprehensive arms control discussions,” including those related to a potential US-China bilateral missile launch notification mechanism.

Corruption

The CMPR focuses quite a bit on China’s ongoing measures to combat corruption, which has led to the removal of dozens of senior officials from their posts across the PLA Air Force, Navy, and Rocket Force. The report notes that “[c]orruption in defense procurement has contributed to observed instances of capability shortfalls, such as malfunctioning lids installed on missile silos”––a story which Bloomberg first reported in January 2024. The report notes that “these investigations very likely risk short term disruptions in the operational effectiveness of the PLA.”

Missiles and delivery systems

The 2025 report included a detail that in December 2024, “the PLA launched several ICBMs in quick succession from a training center into Western China.” Contrary to the launch from Hainan Island, there was very little public reporting about this salvo launch.

The CMPR also indicates an estimated growth in China’s ICBM and IRBM launchers by 50 each, although it is unclear whether these numbers include both finished launchers as well as those still under construction.

The following graph indicates the growth of China’s launchers and missiles, as assessed by the Pentagon, over the past 20 years. It is important to note that many of these missiles, including China’s short- and medium-range ballistic missiles and its ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCMs), are not nuclear-capable.

Our 2025 overview of China’s nuclear arsenal can be freely accessed here.

The Nuclear Information Project is currently supported with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

Inspections Without Inspectors: A Path Forward for Nuclear Arms Control Verification with “Cooperative Technical Means”

The 2010 New START Treaty, the last bilateral agreement limiting deployments of U.S. and Russian strategic arsenals, will expire in February 2026 with no option for renewal. This will usher in an era of unconstrained nuclear competition for the first time since 1972, allowing the United States and Russia to upload hundreds of additional warheads onto their deployed arsenals if they made a political decision to do so. The removal of both the verifiable limits on nuclear weapons, as well as the agreed and proven mechanisms of information sharing about each country’s nuclear arsenal, will increase mistrust, lead to nuclear military planning based on worst case scenarios, and potentially accelerate a global nuclear arms race amid a worsening geopolitical environment.

Traditional nuclear arms control, including New START, relies on the availability of on-site inspections to verify compliance. However, Russia has suspended its participation in New START and opposes intrusive inspections, while political conditions make negotiating an equally robust successor treaty improbable in the near term.

The proposal: verifiable nuclear arms control without on-site inspections

This report outlines a framework relying on “Cooperative Technical Means” (CTM) for effective arms control verification based on remote sensing, avoiding on-site inspections but maintaining a level of transparency that allows for immediate detection of changes in nuclear posture or a significant build-up above agreed limits. This approach builds on Cold War precedents—particularly SALT II, which relied largely on national technical means (NTM)—while leveraging modern Earth-observation satellites whose capabilities have significantly advanced in recent years.

The proposed interim agreement would:

- Preserve New START’s central limits on launchers and warheads.

- Resume notifications and data exchanges.

- Uphold the principle of non-interference with national technical means of verification.

- Incorporate a set of cooperative measures to expose systems for satellite verification, making possible remote monitoring and counting of nuclear delivery vehicles and nuclear weapons.

Such a regime could either be a formal, legally-binding treaty or an informal political arrangement. A non-binding arrangement may also encourage the participation of other nuclear states willing to freeze the production and deployment of new nuclear weapons, including China, the United Kingdom, France, India, and Pakistan.

How would it work?

Significant increases in both the quality and quantity of state-owned and commercial observation satellites now allow global monitoring of missile silo fields, weapons storage sites, air bases, and ports at high resolutions, in different bands, and at actionable frequencies of observation. These developments make it possible to:

- Count strategic launchers. Missile silos, mobile launchers garrisoned in bases, submarines in ports, and heavy bombers at air bases are all observable by electro-optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensors. Large-scale silo construction is now nearly impossible to conceal.

- Assess deployment status. Cooperative measures—such as opening silo doors for satellite passes—could verify whether launchers contain missiles. AI-assisted SAR and EO imagery could detect, classify and count nuclear bombers. Unique markings or alphanumeric codes placed on mobile launchers and bombers could facilitate counting and identification from space.

- Estimate deployed warheads. New START counts every nuclear bomber as carrying a single warhead. A similar counting rule could be established for other delivery vehicles. Otherwise, exposing missiles’ re-entry vehicles (RV) during coordinated satellite overpasses could allow for the counting of warheads remotely. While this could not confirm if the displayed RVs are nuclear or decoys, it would set verifiable upper limits.

- Address non-strategic and non-deployed weapons. Novel SAR observation techniques can help detect undisclosed activity and traffic around storage facilities, ensuring weapons are not secretly moved in or out.

Why this matters

Arms control is a crucial tool for managing nuclear risks. The proposed remote-sensing verification regime could help maintain transparency, facilitate communication, and provide predictability between the United States and Russia beyond 2026, reducing the danger of nuclear arms racing without needing to tackle the politically sensitive issue of on-site inspections.

No past or present arms control regime is perfect and completely safe against cheating. An agreement fully relying on observation satellites would not fully eliminate uncertainty, but it would be relatively easier to negotiate than one with on-site inspections, and it would increasingly raise the costs of deception, providing visibility into major nuclear developments and leaving a pathway to more comprehensive arms control once it becomes politically viable in the future.

Federation of American Scientists Researchers Contribute Nuclear Weapons Expertise to International SIPRI Yearbook, Out Today

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) launches its annual assessment of the state of armaments, disarmament and international security

Washington, D.C. – June 16, 2025 – Nuclear weapons researchers at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) contributed to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s annual Yearbook, released today. Key findings of SIPRI Yearbook 2025 are that a dangerous new nuclear arms race is emerging at a time when arms control regimes are severely weakened.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “Instead, we see a clear trend of growing nuclear arsenals, sharpened nuclear rhetoric and the abandonment of arms control agreements.”

World’s nuclear arsenals being enlarged and upgraded

Nearly all of the nine nuclear-armed states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and Israel—continued intensive nuclear modernization programmes in 2024, upgrading existing weapons and adding newer versions.

Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,241 warheads in January 2025, about 9614 were in military stockpiles for potential use (see the table below). An estimated 3912 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft and the rest were in central storage. Around 2100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the USA, but China may now keep some warheads on missiles during peacetime.

Since the end of the cold war, the gradual dismantlement of retired warheads by Russia and the USA has normally outstripped the deployment of new warheads, resulting in an overall year-on year decrease in the global inventory of nuclear weapons. This trend is likely to be reversed in the coming years, as the pace of dismantlement is slowing, while the deployment of new nuclear weapons is accelerating.

Russia and the USA together possess around 90 per cent of all nuclear weapons. The sizes of their respective military stockpiles (i.e. useable warheads) seem to have stayed relatively stable in 2024 but both states are implementing extensive modernization programmes that could increase the size and diversity of their arsenals in the future. If no new agreement is reached to cap their stockpiles, the number of warheads they deploy on strategic missiles seems likely to increase after the bilateral 2010 Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START) expires in February 2026.

The USA’s comprehensive nuclear modernization programme is progressing but in 2024 faced planning and funding challenges that could delay and significantly increase the cost of the new strategic arsenal. Moreover, the addition of new non-strategic nuclear weapons to the US arsenal will place further stress on the modernization programme.

Russia’s nuclear modernization programme is also facing challenges that in 2024 included a test failure and the further delay of the new Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and slower than expected upgrades of other systems. Furthermore, an increase in Russia’s non-strategic nuclear warheads predicted by the USA in 2020 has so far not materialized.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Costs for U.S. Nuclear Weapon Programs Continue to Spiral Out of Control

In 2014, my colleagues at the Monterey Institute for International Studies and I authored a study called The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad. This report laid out comprehensively, for the first time, that the recently launched US nuclear modernization program–including building new nuclear-armed submarines, bombers, and long-range missiles as well as new nuclear weapons–would likely cost over $1 trillion during its 30-year time scale. Until then, no one had even an estimate for how much these programs would cost over their lifetimes. At the time, my co-authors and I were criticized by advocates for the nuclear modernization program as alarmist and accused of actively seeking to inflate estimates to undermine political support for these programs. Overall, proponents argued that these programs were necessary and that the cost was a mere fraction of the Pentagon’s overall budget, historically low when compared to the nuclear modernization of the 1970s and 1980s. What was originally described merely as a bow wave of costs has become a tsunami.

On April 25, the Congressional Budget Office released its latest estimate that costs of maintaining the current nuclear arsenal and modernizing the entire program would cost nearly $1 trillion over the next 10 years alone. As was once said, there are lies, damn lies, and statistics. This is not an argument about statistics but about absolute numbers. By any measure, $1 trillion is an enormous amount of money to spend in 10 years, and any other U.S. Government or private effort on this scale would receive intense scrutiny and attention–in fact, the Sentinel ICBM modernization most recently triggered a critical breach of the Nunn McCurdy act in 2024. Moreover, if the nuclear budget is going to average 10% from the estimated $1 trillion annual defense budget for the next decade, the nuclear program is now eating the defense budget alive.

For those who may doubt whether oversight is necessary, one only needs to look at one of the more visible elements of the nuclear modernization program–the effort to replace the Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic missile program. When we did our original estimate in 2014, there was no estimate for the cost of replacing the MMIII. We noted that past efforts to build comparable long-range missile systems were complex, expensive, and prone to large cost overruns. The example we cited was the “Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle, which involved the purchase of 150 space launch vehicles based on existing technologies. Originally slated to cost $30 billion, program costs now exceed $70 billion.”

The sole recommendation of this 2014 report was that the USG and Department of Defense in particular needs to create a stand alone nuclear budget to understand the complex nature of these programs and their costs, and keep them on budget and under control. While we did not push the recommendation in the report, we strongly suggested overall that the program was unlikely to meet schedule and cost milestones because it was going to put the constrained U.S. defense industrial capacity under stress and it would be better to stagger these complex multi-decade and multi-billion dollar programs.Ten years later, this recommendation is still needed.

To push these programs through and dismiss alternatives, the military and defense contractors and defense hawks in Congress argued the sky was falling, that Russia and China were modernizing, that nuclear war would be more expensive, so there was no margin for error or delay to consider alternatives. Ironically, the mismanagement of the modernization program now threatens to produce the very delay they were warning against.

In all of these areas, our report was not only rebuffed by advocates for the nuclear modernization program, but our recommendations were ignored. And over time, the consequences of plowing ahead with these programs despite predicted problems have come to pass. The MMIII replacement program, now dubbed Sentinel, was originally estimated to cost $62 billion. That program is now slated to cost $126 billion in the next 10 years alone, and over $140 billion in total. Those costs can also be expected to keep rising due to ongoing delays in the program. This program bypassed the normal programmatic reviews and procurement milestones, and was rushed to a single source contract during President Trump’s first term, with predictably bad results. It now seems likely that the Air Force will have to extend the life of the MMIII missile through 2050–something supporters of the new ICBM have argued would be impossible in both 2021 and 2023.

There is still no comprehensive budget from DOD laying out their costs or predicting the full cost of implementing the current U.S. nuclear weapons modernization program. This is akin to agreeing to buying a house without knowing the sales price, the mortgage rate, or the monthly payment. Yes, you need to live somewhere, but in an era where critical U.S. programs for defense, science, climate, health and international programs and even nuclear weapons security and safety are being cut, it is nonsensical that these programs continue without adequate oversight and knowledge of their true costs.

Whether the U.S. can afford these programs is a reasonable question. Knowing how much these new systems will cost, it is appropriate to ask: if the Pentagon can not produce even a budget on costs, how can they be expected to oversee and deliver what their advocates claim are critical national security programs? The inadequate oversight, cost management and even basic program accountability will result, as we predicted in 2014, “disarmament by default”, an unsustainable and dangerous way to manage U.S. national security.

Federation of American Scientists Releases Latest United States Edition of Nuclear Notebook

Washington, D.C. – January 13, 2025 – Today, the Federation of American Scientists released “United States Nuclear Weapons, 2025”—its estimate and analysis of the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal. The annual report, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, estimates that the United States maintains a stockpile of approximately 3,700 warheads, about 1,700 of which are deployed.

Under several successive presidential administrations, the United States has pursued an ambitious nuclear modernization program, including upgrades to each leg of its nuclear arsenal. Under the Biden administration, however, the debate has shifted to begin assessing ways that the United States could potentially increase the number of nuclear weapons that could be deployed on its current launchers by uploading more warheads.

Despite mounting cost overruns and program delays in its nuclear modernization efforts, the incoming Trump administration has signaled it may pursue additional nuclear weapons programs and further expand the role that these weapons play in U.S. military strategy, based in part on the recommendations of the 2023 Strategic Posture Commission.

Nuclear Signaling

In recent years, the United States sought to use its nuclear arsenal to signal both its resolve and capability to adversary nations—an effort likely to continue and grow in the coming years. Past efforts at nuclear signaling include increased nuclear-armed bomber exercises, updating nuclear strike plans, nuclear submarine visits to foreign ports, and participation in NATO’s annual Steadfast Noon nuclear exercise. In addition, the Biden administration announced that its new nuclear employment guidance determined “it may be necessary to adapt current U.S. force capability, posture, composition, or size,” and directed the Pentagon “to continuously evaluate whether adjustments should be made.” This language effectively leaves it to the incoming Trump administration to decide whether to expand the U.S. arsenal in response to China’s buildup (read a detailed FAS analysis by Adam Mount and Hans Kristensen here).

Modernization and Nuclear Infrastructure

Nuclear modernization continues for all three legs of the nuclear triad. For the ground-based leg, the new ICBM reentry vehicle––the Mk21A––is expected to enter the Engineering and Manufacturing development phase in FY25. It will be integrated into the Sentinel ICBM and carry the new W87-1 warheads currently under development. The Sentinel ICBM program continues to run over-budget as all 450 launch centers must be renovated to accommodate the new missile, and new command and control facilities, launch centers, training sites, and curriculum for USAF personnel must be created. For the sea leg, the first Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN)––the USS District of Columbia––passed its 50 percent construction completion metric in August 2024, and the USS Wisconsin passed 14 percent in September. The new SSBNs will include a reactor that, unlike the Ohio class SSBNs, will not require refueling for the entirety of its lifecycle. The program faces delays and is projected to cost five times more than the Navy’s estimates For the air leg, the Air Force is developing a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) known as the AGM-181 LRSO, as well as the B-21 Raider and new gravity bombs, including the B61-12 and B61-13.

Throughout 2024, infrastructure upgrades at various U.S. ICBM bases were visible. This includes a new Weapons Generation Facility at Malmstrom Air Force Base and a Missile-Handling and Storage Facility and Transporter Storage Facility at F.E. Warren Air Force Base, as well as test silos at Vandenberg Space Force Base.

Finally, in addition to these ongoing upgrades, the United States is also considering developing a new non-strategic nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), which was proposed during the first Trump administration. Despite the Biden administration’s attempt to cancel the program, Congress has forced the administration to establish the SLCM-N as a program of record. The SLCM-N was originally expected to use the W80–4 warhead that is being developed for the LRSO; however, this is currently being renegotiated. The warhead and delivery platform are expected to be finalized in early 2025.

The Nuclear Notebook is published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and freely available here.

This latest issue follows the release of the 2024 UK Nuclear Notebook. The next issue will focus on China. Additional analysis of global nuclear forces can be found at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

ABOUT THE NUCLEAR NOTEBOOK

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is an effort by the Nuclear Information Project team published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The joint publication began in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenals and the role of nuclear weapons in national security.

The Federation of American Scientists’ work on nuclear transparency would not be possible without generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Longview Philanthropy, the Jubitz Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More at fas.org

Nuclear Experts from the Federation of American Scientists Contribute to SIPRI Yearbook 2024

FAS’s Nuclear Information Project estimates that the combined global inventory of nuclear warheads is approximately 12,120

Washington, DC – June 17, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists’ nuclear weapons researchers Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda with the Nuclear Information Project write in the new SIPRI Yearbook, released today, that the world’s nuclear arsenals are on the rise, and massive modernization programs are underway.

“China is expanding its nuclear arsenal faster than any other country,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “But in nearly all of the nuclear-armed states, there are either plans or a significant push to increase nuclear forces.”

“We are entering a new period in the post-Cold War era as nuclear stockpiles increase and nuclear transparency decreases. It is, therefore, extremely important for independent researchers to inject factual data into the debate,” says Matt Korda, Associate Researcher in the SIPRI Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Senior Research Fellow at FAS.

Kristensen and Korda are leading researchers on the global stockpile of nuclear weapons. Along with their colleagues Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight, the Nuclear Information Project team at FAS produces the Nuclear Notebook, a bi-monthly report published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists detailing current estimates of nuclear weapon stockpiles. This work plays an increasingly important role as government transparency about nuclear forces continues to decline around the globe. Ongoing reports, archives, and other materials are available at fas.org.

The first edition of the SIPRI Yearbook was released in 1969, with the aim of producing “a factual and balanced account of a controversial subject-the arms race and attempts to stop it.” Interested parties may download excerpts from the latest Yearbook in several languages here, or purchase the report in full.

Read a summary of SIPRI findings by FAS Nuclear Information Project researcher Eliana Johns here.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

TPNW2MSP: Overview and Key Takeaways

The 2nd Meeting of States Parties (MSP) to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) took place at United Nations Headquarters in New York City from November 27 through December 1. Participants in the Meeting included 59 member nations, 35 observer states, around 700 civil society registrants, members of the scientific community, and representatives of communities affected by nuclear weapons.

The Meeting culminated in agreement by states parties on a joint declaration and package of decisions. Arguably, the most significant outcome of the 2nd MSP was the consensus joint declaration challenging long-held assumptions of nuclear deterrence theory and affirming the security risks it poses.

What’s happened since the first MSP

The first Meeting of States Parties to the TPNW occurred in Vienna, Austria in June 2022, where states parties adopted the Vienna Action Plan. That plan listed 50 actions for States Parties to implement the TPNW and goal of global nuclear disarmament and created three working groups on disarmament verification; victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation and assistance; and universalisation. The Vienna Plan additionally created thematic focal points for gender and complementarity of the TPNW with other fora like the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The working groups each met several times during the intersessional period.

The first MSP also created a Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) of 15 experts to study and provide scientific and technical expertise on a variety of issues related to nuclear weapons. The SAG is the first international scientific body formally created by a multilateral treaty process to promote nuclear disarmament. The group met nine times during the intersessional period to prepare its report to the second MSP, and its final report drew heavily upon research conducted by independent open-source analysts, including the Federation of American Scientists.

Several states have joined or taken action toward joining the treaty during the intersessional period. The Bahamas, Barbados, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Haiti, and Sierra Leone signed the treaty; the Dominican Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Malawi ratified the treaty; Sri Lanka acceded to the treaty; and Indonesia, the fourth largest country in the world by population, recently enacted the TPNW into law within its parliament and is expected to soon complete ratification.

Nearly half of NPT states parties have now signed the TPNW, reflecting growing unacceptance of the lack of progress on nuclear weapons states’ Article VI disarmament obligations.

Noteworthy happenings during 2MSP

The 2nd Meeting of States Parties included a large number of national and other statements and reports. The proceedings notably included moving testimony from nuclear-affected communities, active participation and presentation of research by civil society, a report from the Scientific Advisory Group, notable observer state attendance, and statements from a group of parliamentarians from around the world and the financial community.

Impacted communities

One of the most important features of the TPNW is its focus on impacted communities. Participants and attendees included victims of nuclear testing in Kazakhstan, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Australia, and French Polynesia; Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) from Hiroshima and Nagasaki; downwinders from the U.S. Southwest; and communities impacted by uranium mining.

Benetick Kabua Maddison, Executive Director of the Marshallese Education Initiative, delivered a joint statement to the Meeting on behalf of 26 affected community organizations and supported by 45 allied organizations that provided testimony of the harm of nuclear weapons and called for land remediation and universalization of the treaty.

Scientific Advisory Group

In addition to numerous civil society research presentations and statements throughout the week, the Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) presented its Report on the Status and Developments Regarding Nuclear Weapons to the Meeting. This presentation marked the first formal participation of the SAG in the proceedings of the TPNW following its formation.

SAG co-chairs Dr. Zia Mian and Dr. Patricia Lewis introduced the report to the MSP. The report, heavily citing the work of FAS’s Nuclear Information Project, included an overview of the global status of nuclear stockpiles, nuclear modernization, nuclear risks, humanitarian consequences, and disarmament verification. Additionally, the SAG recommended a global scientific study sponsored by the UN on the effects and consequences of nuclear war.

Observer states

Unsurprisingly, none of the nuclear-armed states attended, but several U.S. treaty allies – Australia, Belgium, Germany, and Norway – attended the MSP as observers. Two of the observers (Belgium and Germany) are part of the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons in times of war.

The delegate from Norway made a statement in support of NATO as a nuclear alliance: “Norway stands fully behind NATO’s nuclear deterrence and posture, including the established nuclear sharing arrangements.” According to some analysts, this may be the first time Norway has explicitly supported U.S. nuclear weapons deployments in Europe in a multilateral disarmament forum. This continues a trend of increased support of NATO nuclear missions by Norway since the end of the Cold War, which has recently included participating in joint exercises with US B-52 bombers and a US B-2 bomber landing in Norway for the first time.

The German delegation similarly supported NATO’s nuclear mission in its statement to the Meeting while criticizing Russia’s announcement of nuclear weapons deployments to Belarus. The representative stated that “confronted with an openly aggressive Russia, the importance of nuclear deterrence has increased for many states, including for my country.”

Three observer states to the first MSP were notably absent from the second: The Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden. The Netherlands is the only NATO member to participate in the initial negotiations of the TPNW. Despite this, the Netherlands has consistently voted against UNGA resolutions welcoming the adoption of the TPNW, and, after the first MSP, the Dutch Foreign Ministry reported that continued observation of TPNW proceedings “is not useful.”

Finland voted against the UNGA resolution on the TPNW for the first time in 2022 and chose not to observe the 2nd MSP, possibly due to its recent NATO membership. Sweden similarly voted against the resolution for the first time in 2022 and was absent from the 2nd MSP. These actions by Sweden could be related to its bid for NATO membership and its brand new Defense Cooperation Agreement with the U.S.

Points of tension

Although states parties came to agreement on a final declaration and package of decisions (with the MSP even closing around two hours earlier than scheduled on the final day), there were some points of disagreement and division throughout the week.

One primary disagreement was on nuclear sharing – particularly how strongly the final declaration should condemn it. European states parties pushed back on forceful language to prevent their regional allies and the U.S. from being implicated in the condemnation that they wanted centered on Russia’s nuclear deployments to Belarus. The final joint declaration avoided mention of specific sharing arrangements and simply included a condemnation of and call to cease all such arrangements.

In a similar vein, some states like South Africa wanted to include strong language on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) that would condemn both Russia’s recent de-ratification and the fact that the U.S. has never ratified the CTBT. U.S. allies at the Meeting, however, wanted language focusing solely on Russia’s actions. Ultimately, neither country was identified by name in the joint declaration; instead, states parties made a broad call for all countries to sign and ratify the CTBT and promote its entry into force.

Unique participants

Alongside states parties, observer states, and civil society groups, the TPNW 2MSP included participation from a diverse, global group of parliamentarians as well as representatives from the financial community.

A delegation of 23 parliamentarians from 14 different countries, including US Rep. Jim McGovern (D-MA), delivered a statement to the Meeting urging governments (in some cases their own) to join the treaty.

The financial community provided a statement to the MSP on behalf of over 90 investors to promote collaboration between states parties and the financial community to divest from the nuclear weapons industry.

Results of the MSP: Final declaration and decisions

The Meeting of States Parties closed on Friday, December 1st around 4:30 PM after consensus agreement on a joint declaration and package of decisions.

Through the joint declaration, states presented their consensus view that nuclear risks are growing due to the actions of nuclear weapons states: “Nuclear risks are being exacerbated in particular by the continued and increasing salience of and emphasis on nuclear weapons in military postures and doctrines, coupled with the on-going qualitative modernization and quantitative increases in nuclear arsenals, and the heightening of tensions.”

States parties additionally declared the catastrophic humanitarian effects of nuclear weapons as the central impetus for pursuing and achieving global nuclear disarmament, spotlighting the human and environmental costs to argue that “the only guarantee against the use of nuclear weapons is their complete elimination and the legally binding assurance that they will never be developed again.” States jointly rejected any normalization of nuclear rhetoric and identified nuclear threats and deterrence as security risks, declaring:

“The threat of inflicting mass destruction runs counter to the legitimate security interests of humanity as a whole. This is a dangerous, misguided and unacceptable approach to security… Far from preserving peace and security, nuclear weapons are used as instruments of policy, linked to coercion, intimidation and heightening of tensions. The renewed advocacy, insistence on and attempts to justify nuclear deterrence as a legitimate security doctrine gives false credence to the value of nuclear weapons for national security and dangerously increases the risk of horizontal and vertical nuclear proliferation… The perpetuation and implementation of nuclear deterrence in military and security concepts, doctrines and policies not only erodes and contradicts nonproliferation, but also obstructs progress towards nuclear disarmament.”

On nuclear sharing, states parties called on all states with nuclear arrangements, including extended nuclear security guarantees, to cease all such arrangements and join the TPNW. They also reaffirmed the complementarity between the TPNW and the NPT and called out the lack of progress nuclear weapons states have made toward their NPT Article VI obligations on disarmament.

The package of decisions included an agreement by states parties to collaborate in challenging false narratives of nuclear deterrence by engaging in and promoting scientific work on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. This collaboration includes the establishment of a consultative process on security concerns of states to advance arguments against nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence.

States also agreed to engage in discussions on establishing an international trust fund for victim assistance and environmental remediation. Lack of progress and vague phrasing on such a trust fund is likely due to disagreements on whether or not non-states parties to the TPNW should be able to contribute to the fund. Some states fear non-states parties could use their contributions to the trust fund to avoid strong pressure to join the treaty.

Next steps for the intersessional period

The Third Meeting of States Parties to the treaty will take place in 2025 from March 3 to 7, again in New York.

During the intersessional period, the informal working groups established by the Vienna Action Plan will continue to meet, and focused discussions will take place in order to present a report to the third MSP on the feasibility and guidelines for an international trust fund.

States parties and signatories will engage in an intersessional consultative process along with the Scientific Advisory Group, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), and others with the aim of providing a report to the third MSP containing arguments and recommendations to promote a counternarrative to nuclear deterrence rhetoric.

Strategic Posture Commission Report Calls for Broad Nuclear Buildup

On October 12th, the Strategic Posture Commission released its long-awaited report on U.S. nuclear policy and strategic stability. The 12-member Commission was hand-picked by Congress in 2022 to conduct a threat assessment, consider alterations to U.S. force posture, and provide recommendations.

In contrast to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the Congressionally-mandated Strategic Posture Commission report is a full-throated embrace of a U.S. nuclear build-up.

It includes recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase its number of deployed warheads, as well as increasing its production of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warhead production capacity. It also calls for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal.

The only thing that appears to have prevented the Commission from recommending an immediate increase of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile is that the weapons production complex currently does not have the capacity to do so.

The Commission’s embrace of a U.S. nuclear buildup ignores the consequences of a likely arms race with Russia and China (in fact, the Commission doesn’t even consider this or suggest other steps than a buildup to try to address the problem). If the United States responds to the Chinese buildup by increasing its own deployed warheads and launchers, Russia would most likely respond by increasing its deployed warheads and launchers. That would increase the nuclear threat against the United States and its allies. China, who has already decided that it needs more nuclear weapons to stand up to the existing U.S. force level (and those of Russia and India), might well respond to the U.S and Russian increases by increasing its own arsenal even further. That would put the United States back to where it started, feeling insufficient and facing increased nuclear threats.

Framing and context

The Commission’s report is generally framed around the prospect of Russian and Chinese strategic military cooperation against the United States. The Commission cautions against “dismissing the possibility of opportunistic or simultaneous two-peer aggression because it may seem improbable,” and notes that “not addressing it in U.S. strategy and strategic posture, could have the perverse effect of making such aggression more likely.” The Commission does not acknowledge, however, that building up new capabilities to address this highly remote possibility would likely kick the arms race into an even higher gear.

The report acknowledges that Russia and China are in the midst of large-scale modernization programs, and in the case of China, significant increases to its nuclear stockpile. This accords with our own assessments of both countries’ nuclear programs. However, the report’s authors suggest that these changes fundamentally call into question the United States’ assured retaliatory capabilities, and state that “the current U.S. strategic posture will be insufficient to achieve the objectives of U.S. defense strategy in the future….”

The Commission appears to base this conclusion, as well as its nuclear strategy and force structure recommendations, squarely on numerically-focused counterforce thinking: if China increases its posture by fielding more weapons, that automatically means the United States needs more weapons to “[a]ddress the larger number of targets….” However, the survivability of the US ballistic missile submarines should insulate the United States against needing to subscribe to this kind of thinking.

In 2012, a joint DOD/DNI report acknowledged that because of the US submarine force, Russia would not achieve any military advantage against the United States by significantly increasing the size of its deployed nuclear forces. In that 2012 study, both departments concluded that the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” [Emphasis added.] Why would this logic not apply to China as well? Although China’s nuclear arsenal is undoubtedly growing, why would it fundamentally alter the nature of the United States’ assured retaliatory capability while the United States is confident in the survivability of its SSBNs?

In this context, it is worth reiterating the words of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at the U.S. Strategic Command Change of Command Ceremony: “We all understand that nuclear deterrence isn’t just a numbers game. In fact, that sort of thinking can spur a dangerous arms race…deterrence has never been just about the numbers, the weapons, or the platforms.”

Force structure

Although the report says the Commission “avoided making specific force structure recommendations” in order to “leave specific material solution decisions to the Executive Branch and Congress,” the list of “identified capabilities beyond the existing program of record (POR) that will be needed” leaves little doubt about what the Commission believes those force structure decisions should be.

Strategic posture alterations

The Commission concludes that the United States “must act now to pursue additional measures and programs…beyond the planned modernization of strategic delivery vehicles and warheads may include either or both qualitative and quantitative adjustments in the U.S. strategic posture.”

Specifically, the Commission recommends that the United States should pursue the following modifications to its strategic nuclear force posture “with urgency:” [our context and commentary added below]

- Prepare to upload some or all of the nation’s hedge warheads; [these warheads are currently in storage; increasing deployed warheads above 1,550 is prohibited by the New START treaty (which expires in early-2026) and would likely cause Russia to also increase its deployed warheads.]

- Plan to deploy the Sentinel ICBM in a MIRVed configuration; [the Sentinel appears to be capable of carrying two MIRV but current plan calls for each missile to be deployed with just a single warhead]

- Increase the planned number of deployed Long-Range Standoff Weapons; [the Air Force currently has just over 500 ALCMs and plans to build 1,087 LRSOs (including test-flight missiles), each of which costs approximately $13 million]

- Increase the planned number of B-21 bombers and the tankers an expanded force would require; [the Air Force has said that it plans to purchase at least 100 B-21s]

- Increase the planned production of Columbia SSBNs and their Trident ballistic missile systems, and accelerate development and deployment of D5LE2; [the Navy currently plans to build 12 Columbia-class SSBNs and an increase would not happen until after the 12th SSBN is completed in the 2040s]

- Pursue the feasibility of fielding some portion of the future ICBM force in a road mobile configuration; [historically, any efforts to deploy road-mobile ICBMs in the United States have been unsuccessful]

- Accelerate efforts to develop advanced countermeasures to adversary IAMD; and

- Initiate planning and preparations for a portion of the future bomber fleet to be on continuous alert status, in time for the B-21 Full Operational Capability (FOC) date.” [Bombers currently regularly practice loading nuclear weapons as part of rapid-takeoff exercises. Returning bombers to alert would revert the decision by President H.W. Bush in 1991 to take bombers off alert. In 2021, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration stated that keeping the bomber fleet on continuous alert would exhaust the force and could not be done indefinitely]

Nonstrategic posture alterations

The Commission appears to want the United States to bolster its non-strategic nuclear forces in Europe, and begin to deploy non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific theater: “Additional U.S. theater nuclear capabilities will be necessary in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific regions to deter adversary nuclear use and offset local conventional superiority. These additional theater capabilities will need to be deployable, survivable, and variable in their available yield options.” Although the Commission does not explicitly recommend fielding either ground-launched theater nuclear capabilities or a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile for the Navy, it seems clear that these capabilities would be part of the Commission’s logic.

The United States used to deploy large numbers of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific region during the Cold War, but those weapons were withdrawn in the early 1990s and later dismantled as U.S. military planning shifted to rely more on advanced conventional weapons for limited theater options. Despite the removal of certain types of theater nuclear weapons after the Cold War, today the President maintains a wide range of nuclear response options designed to deter Russian and Chinese limited nuclear use in both regions––including capabilities with low or variable yields. In addition to ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-capable bombers operating in both regions, the U.S. Air Force has non-strategic B61 nuclear bombs for dual-capable aircraft that are intended for operations in both regions if it becomes necessary. The Navy now also has a low-yield warhead on its SSBNs––the W76-2––that was fielded specifically to provide the President with more options to deter limited scenarios in those regions. It is unclear why these existing options, as well as several additional capabilities already under development––including the incoming Long-Range Stand-Off Weapon––would be insufficient for maintaining regional deterrence.

The Commission specifically recommends that the United States should “urgently” modify its nuclear posture to “[p]rovide the President a range of militarily effective nuclear response options to deter or counter Russian or Chinese limited nuclear use in theater.” Although current plans already provide the President with such options, the Commission “recommends the following U.S. theater nuclear force posture modifications:

Develop and deploy theater nuclear delivery systems that have some or all of the following attributes: [our context and commentary added below]

- Forward-deployed or deployable in the European and Asia-Pacific theaters [The United States already has dual-capable fighters and B61 bombs earmarked for operations in the Asia-Pacific theaters, backed up by bombers with long-range cruise missiles];

- Survivable against preemptive attack without force generation day-to-day;

- A range of explosive yield options, including low yield [US nuclear forces earmarked for regional options already have a wide range of low-yield options];