New START 2017: Russia Decreasing, US Increasing Deployed Warheads

By Hans M. Kristensen

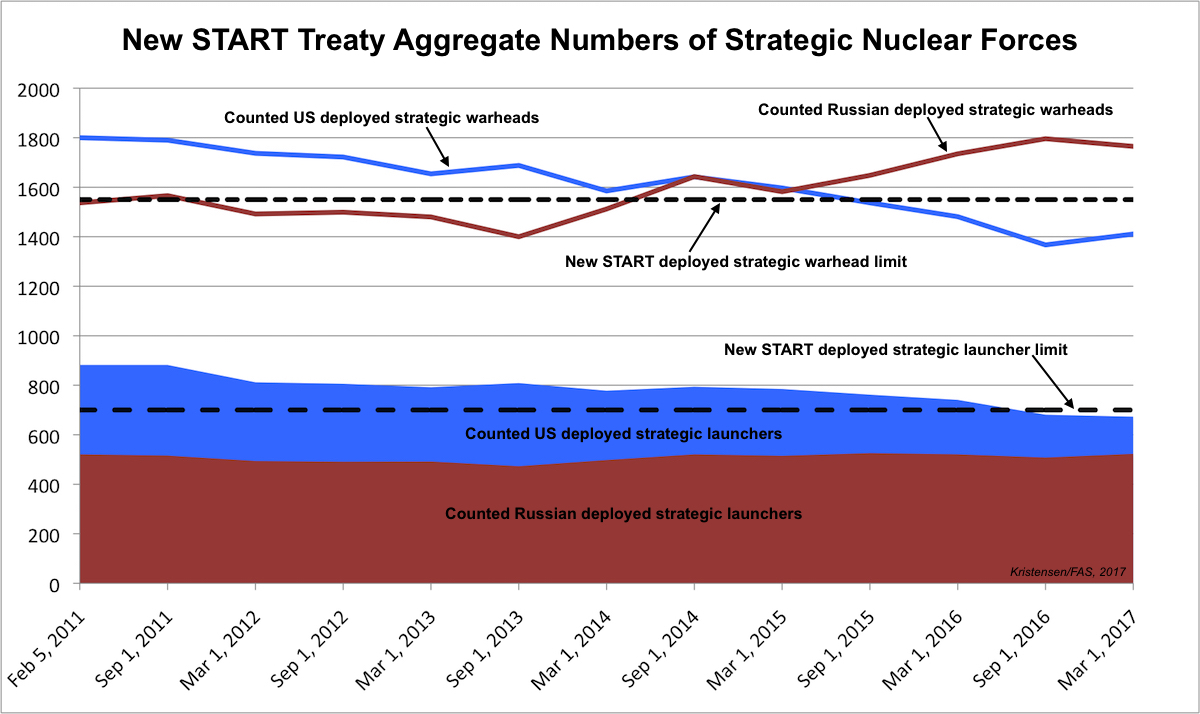

The latest set of New START aggregate data released by the US State Department shows that Russia is decreasing its number of deployed strategic warheads while the United States is increasing the number of warheads it deploys on its strategic forces.

The Russian reduction, which was counted as of March 1, 2017, is a welcoming development following its near-continuous increase of deployed strategic warheads compared with 2013. Bus as I previously concluded, the increase was a fluctuation caused by introduction of new launchers, particularly the Borei-class SSBN.

The US increase, similarly, does not represent a buildup – a mischaracterization used by some to describe the earlier Russian increase – but a fluctuation caused by the force loading on the Ohio-class SSBNs.

Strategic Warheads

The data shows that Russia as of March 1, 2017 deployed 1,765 strategic warheads, down by 31 warheads compared with October 2016. That means Russia is counted as deploying 228 strategic warheads more than when New START went into force in February 2011. It will have to offload an additional 215 warheads before February 2018 to meet the treaty limit. That will not be a problem.

The number of Russian warheads counted by the New START treaty is only a small portion of its total inventory of warheads. We estimate that Russia has a military stockpile of 4,300 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 7,000 warheads.

The United States was counted as deploying 1,411 strategic warheads as of March 1, 2017, an increase of 44 warheads compared with the 1,367 strategic deployed warheads counted in October 2016. The United States is currently below the treaty limit and can add another 139 warheads before the treaty enters into effect in February 2018.

The number of US warheads counted by the New START treaty is only a small portion of its total inventory of warheads. We estimate that the United States has a military stockpile of 4,000 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 6,800 warheads.

Strategic Launchers

The New START data shows that Russia as of March 1, 2017 deployed 523 strategic launchers, an increase of 15 launchers compared with October 2016. That means Russia has two (2) more launched deployed today than when New START entered into force in February 2011.

Russia could hypothetically increase its force structure by another 177 launchers over the next ten months and still be in compliance with New START. But its current nuclear modernization program is not capable of doing so.

Under the treaty, Russia is allowed to have a total of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. The data shows that it currently has 816, only 16 above the treaty limit. That means Russia overall has scrapped 49 total launchers (deployed and non-deployed) since New START was signed in February 2011.

The United States is counted as deploying 673 strategic launchers as of March 1, 2017, a decrease of eight (8) launchers compared with October 2016. That means the United States has reduced its force structure by 209 deployed strategic launchers since February 2011.

The US reduction has been achieved by stripping essentially all excess bombers of nuclear equipment, reducing the ICBM force to roughly 400, and making significant progress on reducing the number of launch tubes on each SSBN from 24 to 20.

The United States is below the limit for strategic launchers and could hypothetically add another 27 launchers, a capability it currently has. Overall, the United States has scrapped 304 total launchers (deployed and non-deployed) since the treaty entered into force in February 2011, most of which were so-called phantom launchers that were retired but still contained equipment that made them accountable under the treaty.

The United States currently is counted as having 820 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. It will need to destroy another 20 to be in compliance with New START by February 2018.

Conclusions and Outlook

Both Russia and the United States are on track to meet the limits of the New START treaty by February 2018. The latest aggregate data shows that Russia is again reducing its deployed strategic warheads and both countries are already below the treaty’s limit for deployed strategic launchers.

In a notorious phone call between Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Donald Trump, the Russian president reportedly raised the possibility of extending the New START treaty by another five years beyond 2021. But Trump apparently brushed aside the offer saying New START was a bad deal. After the call, Trump said the United States had “fallen behind on nuclear weapons capacity.”

In reality, the United States has not fallen behind but has 150 strategic launchers more than Russia. The New START treaty is not a “bad deal” but an essential tool to provide transparency of strategic nuclear forces and keeping a lid on the size of the arsenals. Russia and the United States should move forward without hesitation to extend the treaty by another five years.

Additional resources:

- New START Aggregate Data (as of March 1, 2017)

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Warhead “Super-Fuze” Increases Targeting Capability Of US SSBN Force

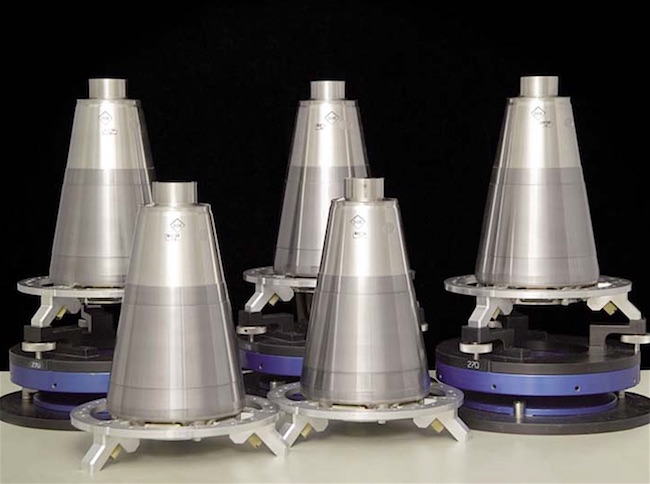

The MC7400 AF&F unit on the new W76-1/Mk4A warhead contains a super-fuze that dramatically increases its hard target kill capability. Image: Sandia National Laboratories

By Hans M. Kristensen

Under the cover of an otherwise legitimate life-extension of the W76 warhead, the Navy has quietly added a new super-fuze to the warhead that dramatically increases the ability of the Navy to destroy hard targets in Russia and other adversaries.

In a new article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists Matthew McKinzie from NRDC, Theodore A. Postol from MIT, and I describe the impact of the super-fuze on the targeting capability of the US SSBN force and how it might effect strategic stability.

The new super-fuze dramatically increases the capability of the W76 warhead to destroy hard targets, such as Russian ICBM silos.

We estimate that the super-fuze capability is now operational on all nuclear warheads deployed on the Navy’s Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines. The new fuze has also been installed on warheads on British SSBN.

“As a consequence, the US submarine force today is much more capable than it was previously against hardened targets such as Russian ICBM silos. A decade ago, only about 20 percent of US submarine warheads had hard-target kill capability; today they all do.”

The new article builds on previous work by Ted Postol and myself but with new analysis explaining how the super-fuze works.

In the article we conclude that the SSBN force, rather than simply being a stable retaliatory capability, with the new super-fuze increasingly will be seen as a front-line, first-strike weapon that is likely to further fuel trigger-happy, worst-case planning in other nuclear-armed states.

Read full article here: Hans M. Kristensen, Matthew McKinzie, Theodore A. Postol, “How US nuclear force modernization is undermining strategic stability: The burst-height compensating super-fuze,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, March 1, 2017.

Previous writings about the super-fuze:

- Theodore A. Postol, “How the Obama Administration Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” The Nation, December 10, 2014.

- Hans M. Kristensen, “British Submarines to Receive Upgraded US Nuclear Warhead,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, April 1, 2011.

- Hans M. Kristensen, “Administration Increases Submarine Nuclear Warhead Production Plan,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, August 30, 2007.

- Hans M. Kristensen, “Small Fuze – Big Effect,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, March 14, 2017.

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

In Reuters Interview President Trump Flunks Nuclear 101

President Donald Trump in an interview with Reuters today demonstrated an astounding lack of knowledge about basic nuclear weapons issues.

According to Reuters Trump said he wanted to build up the US nuclear arsenal to ensure it is at the “top of the pack.” He said the United States has “fallen behind on nuclear weapons capacity.”

Building up the US nuclear arsenal would be an unnecessary, unaffordable, and counterproductive move. It is unnecessary because the US military already has more nuclear weapons than it needs to meet US national and international security commitments. It would be unaffordable because the Pentagon will have problems paying for the nuclear modernization program initiated by the Obama administration. And it is counterproductive because it would further fuel nuclear buildups in other nuclear weapon states.

The claim that the US has “fallen behind on its nuclear weapons capacity” is also wrong; the US has the nuclear weapons capability it needs to meet its national and international security commitments. All nuclear-armed states have different nuclear weapons capacities depending on their individual needs. Nuclear planning is not a race but a strategy.

In terms of capacity, the United States is already at the “top of the pack” with highly capable nuclear forces that are backed up by overwhelming conventional forces. See here how the US nuclear arsenal compares with other nuclear-armed states.

Trump also called the New START Treaty “a one-sided deal” and a “bad deal.” Once again he is wrong. The treaty has equal limits for both the United States and Russia: by February 2018, neither side can have more than 1,550 warheads on 700 deployed launchers and no more than 800 total deployed and non-deployed launchers.

Next month the new bi-annual aggregate data set will be published; the previous one from September 2016 showed Russia with 1,796 warheads on 508 launchers compared with the United States with 1,367 warheads on 681 launchers.

Some people got very excited about that saying the larger number of Russian deployed warheads somehow gave Russia an advantage and showed they didn’t intend to comply with the treaty. Warheads can be moved on and off launchers relatively quickly; the important number is the number of launchers where the US was counted with 173 more than Russia.

Indeed, according to the Pentagon and Intelligence Community, Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty…” (Emphasis added.)

But nitpicking about numbers misses the bigger point: the New START treaty was signed with overwhelming support from the US military, Congress, former officials, and experts because the treaty caps the nuclear forces of both countries and continues an important on-site verification system and data exchange.

President Trump may have been briefed by the Pentagon on his role in the nuclear war plan. But his latest interview with Reuters shows that he urgently needs to be briefed on the status of US nuclear forces, other nuclear-armed states, and the basics of the arms control treaties the United States has signed. But that briefing needs to be done outside the White House bubble and include bi-partisan and independent input. Otherwise all indication are that President Trump will be extraordinarily poorly equipped to make informed decisions about the nuclear policy.

Additional resources:

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

In Reuters Interview President Trump Flunks Nuclear 101

President Donald Trump in an interview with Reuters today demonstrated an astounding lack of knowledge about basic nuclear weapons issues.

According to Reuters Trump said he wanted to build up the US nuclear arsenal to ensure it is at the “top of the pack.” He said the United States has “fallen behind on nuclear weapons capacity.”

Building up the US nuclear arsenal would be an unnecessary, unaffordable, and counterproductive move. It is unnecessary because the US military already has more nuclear weapons than it needs to meet US national and international security commitments. It would be unaffordable because the Pentagon will have problems paying for the nuclear modernization program initiated by the Obama administration. And it is counterproductive because it would further fuel nuclear buildups in other nuclear weapon states.

The claim that the US has “fallen behind on its nuclear weapons capacity” is also wrong; the US has the nuclear weapons capability it needs to meet its national and international security commitments. All nuclear-armed states have different nuclear weapons capacities depending on their individual needs. Nuclear planning is not a race but a strategy.

In terms of capacity, the United States is already at the “top of the pack” with highly capable nuclear forces that are backed up by overwhelming conventional forces. See here how the US nuclear arsenal compares with other nuclear-armed states.

Trump also called the New START Treaty “a one-sided deal” and a “bad deal.” Once again he is wrong. The treaty has equal limits for both the United States and Russia: by February 2018, neither side can have more than 1,550 warheads on 700 deployed launchers and no more than 800 total deployed and non-deployed launchers.

Next month the new bi-annual aggregate data set will be published; the previous one from September 2016 showed Russia with 1,796 warheads on 508 launchers compared with the United States with 1,367 warheads on 681 launchers.

Some people got very excited about that saying the larger number of Russian deployed warheads somehow gave Russia an advantage and showed they didn’t intend to comply with the treaty. Warheads can be moved on and off launchers relatively quickly; the important number is the number of launchers where the US was counted with 173 more than Russia.

Indeed, according to the Pentagon and Intelligence Community, Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty…” (Emphasis added.)

But nitpicking about numbers misses the bigger point: the New START treaty was signed with overwhelming support from the US military, Congress, former officials, and experts because the treaty caps the nuclear forces of both countries and continues an important on-site verification system and data exchange.

President Trump may have been briefed by the Pentagon on his role in the nuclear war plan. But his latest interview with Reuters shows that he urgently needs to be briefed on the status of US nuclear forces, other nuclear-armed states, and the basics of the arms control treaties the United States has signed. But that briefing needs to be done outside the White House bubble and include bi-partisan and independent input. Otherwise all indication are that President Trump will be extraordinarily poorly equipped to make informed decisions about the nuclear policy.

Additional resources:

This publication was made possible by a grant from Carnegie Corporation of New York and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Obama Administration Announces Unilateral Nuclear Weapon Cuts

By Hans M. Kristensen

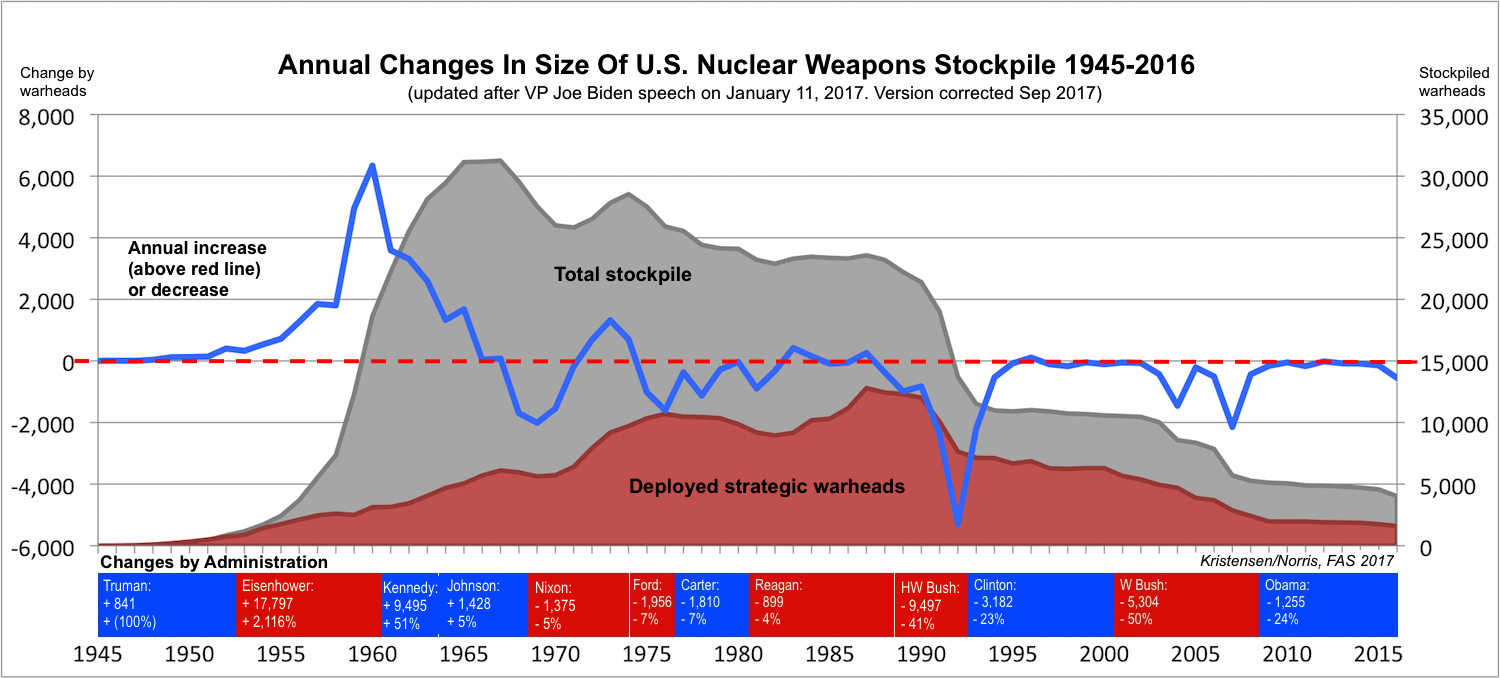

The Obama administration has unilaterally cut the number of nuclear weapons in the Pentagon’s nuclear weapons stockpile to 4,018 warheads, a reduction of 553 warheads since September 2015.

The reduction was disclosed by Vice President Joe Biden during a speech at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace earlier today.

This means that the Obama administration during its two terms has reduced the US nuclear weapons stockpile by 1,255 weapons compared with the size at the end of the George W. Bush administration – a number greater than the estimated number of warheads in the arsenals of Britain, China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, and Pakistan combined.

Stockpile Reductions In Context

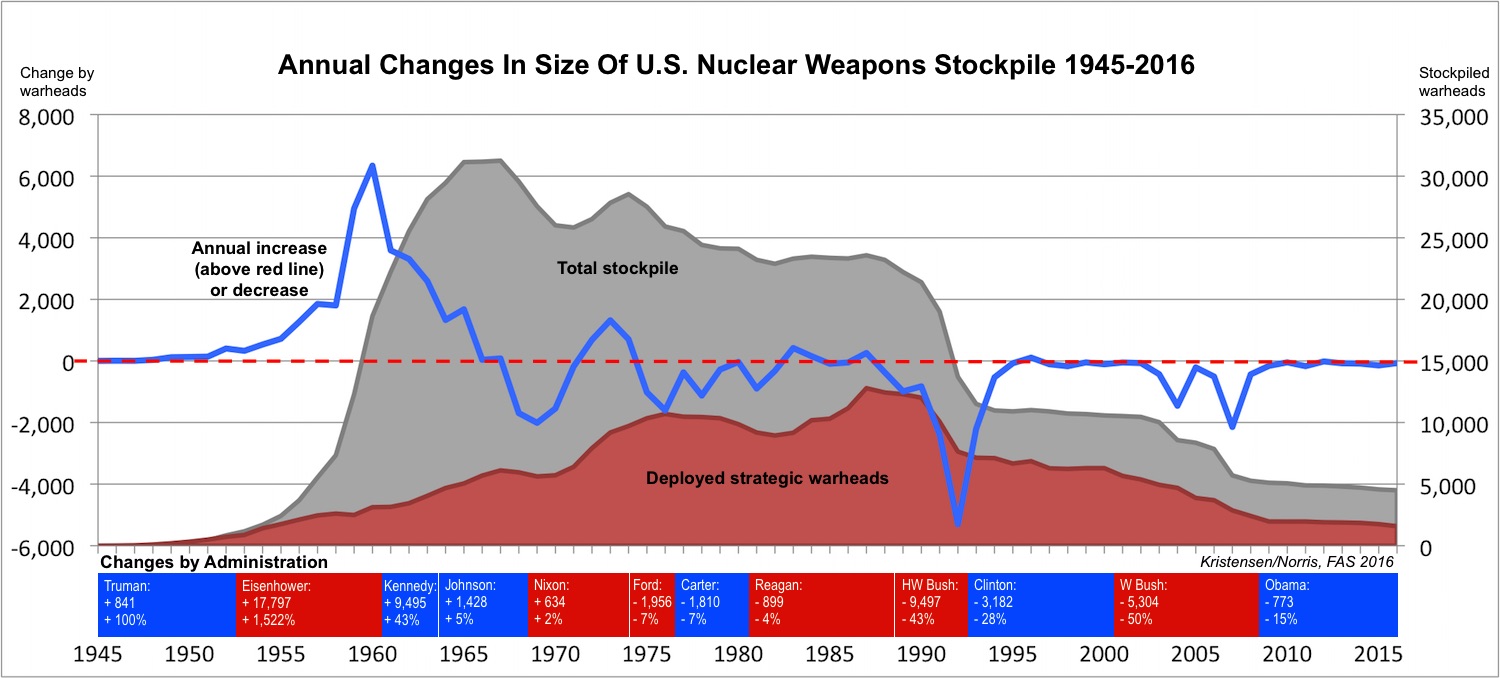

The Obama administration’s additional unilateral cut shows up as a small dip on the graph of US nuclear weapons stockpile changes since 1945 (see figure below; graph corrected Sep 2017).

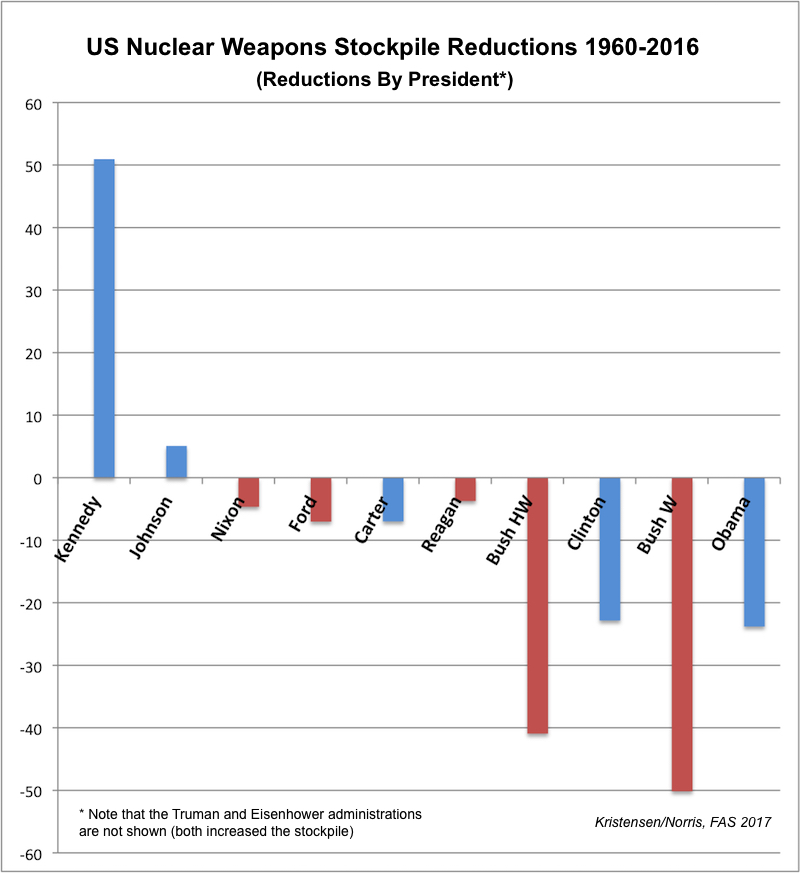

Even so, the Obama administration still holds the position of being the administration that has cut the least warheads from the stockpile compared with other post-Cold War presidencies.

Part of the reason for this is that the overall size of the stockpile today is much smaller than two decades ago, so one would expect new warhead cuts to also be smaller. But this is only partially true because the George W. Bush administration cut significantly more warheads from the stockpile than the Clinton administration.

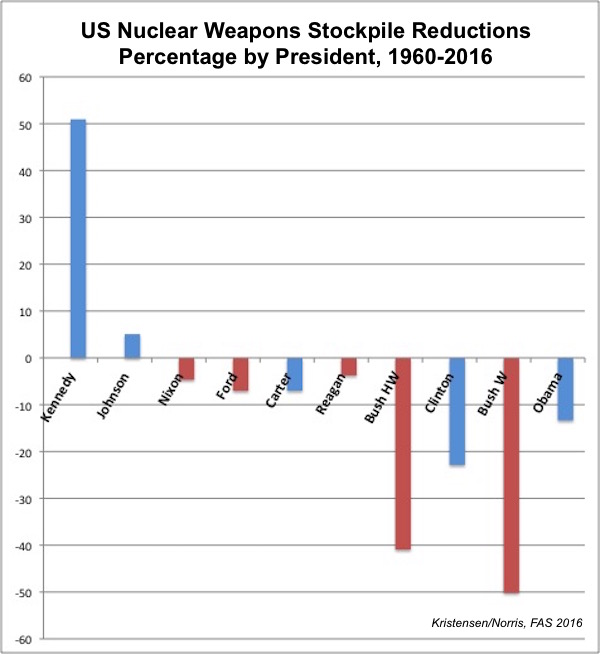

In fact, it is still the case that Republican presidents in the post-Cold War period have cut many more warheads from the stockpile than have Democratic presidents: 14,801 versus 4,437.

Even so, the latest cut means that the Obama administration has managed to surpass (barely) the Clinton administration in terms of how much it reduced the stockpile (24 percent versus 23 percent) (see figure below).

Reducing the Hedge

The administration has not disclosed what types of warheads were cut from the stockpile or what part of it they were taken from. We estimate that the warheads were taken from the inactive reserve of non-deployed warheads that are stored to provide a “hedge” against technical failure of a warhead type or to respond to geopolitical surprises.

The 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy determined that the hedge was too big and that it was only necessary to hedge against technical warhead failure. That hedge would also serve as a geopolitical hedge. As a result, several hundred hedge warheads were no longer needed.

So the 553 cut warheads probably include excess W76, B61, and B83 warheads that were scheduled to be retired anyway as a result of changes to the nuclear war plans and the ongoing warhead life-extension programs. [Update 011317: In addition to excess W76s, the cut might also include the W84 warhead that previously armed the Ground Launch Cruise Missile. The W84 was retired once but brought back into the stockpile as a potential warhead candidate for the LRSO. But after the W80 was selected as the LRSO warhead, the W84 might have met its doom (House conservatives tried to prohibit dismantlement of the W84 in the FY2017 defense bill but the effort didn’t survive the final cut). Yet there were fewer than 400 W84s produced, so the 553 cut (“almost 500 warheads for dismantlement on top of those previously scheduled for retirement”) would have to include other warhead types as well. Those could potentially also include excess W78 ICBM warheads. Any potential B61s would likely be minimal because they await production of the B61-12.]

The Growing Dismantlement Queue

The cut adds significantly to the large inventory of retired (but still intact) warheads that are awaiting dismantlement. Secretary of State John Kerry announced in April 2015 that the retirement queue included some 2,500 warheads. Vice President Biden announced that the number has since grown to about 2,800 warheads.

Biden also announced that the Obama administration during its eight years in office had dismantled 2,226 warheads. That indicates that about 250 warheads were dismantled in the last year.

The administration has promised that all the warheads that were retired prior to 2009 will be dismantled by 2021 (in reality some warheads already dismantled were retired after 2009). But with the average rate of about 278 warheads dismantled per year during the Obama administration, it will take until 2026 to dismantle the current backlog of retired warheads.

Political and Strategic Implications

The Obama administration must be congratulated on taking additional steps to unilaterally reduce the US nuclear weapons stockpile and improve its nuclear arms reduction legacy.

This will help the US position at the Preparatory Conference for the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) later this spring and will increase pressure on the other nuclear-weapons states party to the treaty (Russia, China, France, and Britain) to also take new initiatives – even without formal arms negotiations.

The Obama administration also deserves praise for continuing to provide transparency of the US nuclear arsenal. Not only has it disclosed the history of the US nuclear stockpile and provided annual updates. It has also disclosed its warhead dismantlement history and declared how many retired warheads remain in the dismantlement queue. And it has declassified other chapters of the US nuclear history, including the number of nuclear weapons deployed at sea during the Cold War.

This transparency helps facilitate a debate about the history and future of nuclear weapons that is based on facts rather than rumors. Moreover, it helps increase the incentive for other nuclear-armed states to also be more transparent. If Britain and France were also to disclose their nuclear stockpile and dismantlement histories, the three Western nuclear powers would have a significantly stronger position from which to urge Russia and other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals.

At home, the Obama administration’s announcement about the additional nuclear cuts helps shine the light on the Trump administration and what its nuclear policies will be. Some will decry the Obama administration’s unilateral cut as weakening US military strength, but that would be wrong for several reasons.

First, the Obama administration has started a nuclear weapons modernization program that makes the George W. Bush administration pale in comparison.

Second, the cut reflects US military requirements. The Pentagon has long stated that even after the New START treaty is implemented next year, the United States will still have up to one-third more nuclear warheads deployed than is needed to meet US national and international commitments.

Russia currently has a nuclear weapons stockpile of nearly 4,500 warheads but is also reducing its nuclear arsenal (despite a temporary increase in deployed warheads counted under New START). While some commentators are obsessed with US-Russian nuclear parity, the Pentagon seems less interested in numbers and more interested in quality and in 2012 concluded:

The “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.”

Instead, the Trump administration should continue the broad outline of the Obama administration’s nuclear policy of gradually but responsibly reducing the numbers and reliance on nuclear weapons while actively seeking to persuade other nuclear-armed states to follow the example.

Additional Information:

- United States nuclear forces, 2017 [Note: this publication was researched before the 2017 stockpile announcement.]

- Global Overview: Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Will Trump Be Another Republican Nuclear Weapons Disarmer?

By Hans M. Kristensen

Republicans love nuclear weapons reductions, as long as they’re not proposed by a Democratic president.

That is the lesson from decades of US nuclear weapons and arms control management.

If that trend continues, then we can expect the new Donald Trump administration to reduce the US nuclear weapons arsenal more than the Obama administration did.

What? I know, it sounds strange but the record is very clear: During the post-Cold War era, Republication administrations have – by far – reduced the US nuclear weapons stockpile more than Democratic administrations (see graph below).

Even if we don’t count numbers of weapons (because arsenals have gotten smaller) but only look at by how much the nuclear stockpile was reduced, the history is clear: Republican presidents disarm more than Democrats (see graph below).

It’s somewhat of a mystery. Because Democratic presidents are generally seen to be more likely to propose nuclear weapons reductions. President Obama did so repeatedly. But when Democratic presidents have proposed reductions, the Republican opposition has normally objected forcefully. Yet Republican lawmakers won’t oppose reductions if they are proporsed by a Republican president.

Conversely, Democratic lawmakers will not opposed Republican reductions and nor will they oppose reductions proposed by a Democratic president.

As a result, if the Republicans control both the White House and Congress, as they do now after the 2016 election, the chance of significant reductions of nuclear weapons seems more likely.

Whether Donald Trump will continue the Republication tradition remains to be seen. US-Russian relations are different today than when the Bush administrations did their reductions. But both countries have far more nuclear weapons than they need for national security. And Trump would be strangely out of tune with long-held Republican policy and practice if he does not order a substantial reduction of the US nuclear weapons stockpile.

Perhaps he should use that legacy to try to reach an agreement with Russia to continue to reduce US and Russia nuclear arsenals to the benefit of both countries.

Further reading: Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows Russian Warhead Increase Before Expected Decrease

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest set of so-called New START treaty aggregate data published by the U.S. State Department shows that Russia is continuing to increase the number of nuclear warheads it deploys on its declining inventory of strategic launchers.

Russia now has 259 warheads more deployed than when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Rather than a nuclear build-up, however, the increase is a temporary fluctuation cause by introduction of new types of launchers that will be followed by retirement of older launchers before 2018. Russia’s compliance with the treaty is not in doubt.

In all other categories, the data shows that Russia and the United States continue to reduce the overall size of their strategic nuclear forces.

Strategic Warheads

The aggregate data shows that Russia has continued to increase its deployed strategic warheads since 2013 when it reached its lowest level of 1,400 warheads. Russian strategic launchers now carry 396 warheads more.

Overall, Russia has increase its deployed strategic warheads by 259 warheads since New START entered into force in 2011. Although it looks bad, it has no negative implications for strategic stability.

The Russian warhead increase is probably a temporary anomaly caused primarily by the fielding of additional new Borei-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The third boat of the class deployed to its new base on the Kamchatka Peninsula last month, joining another Borei SSBN that transferred to the Pacific in 2015.

The United States, in contrast, has continued to decrease its deployed strategic warheads. It dipped below the treaty limit in September 2015 but has continued to decrease its deployed warheads to 1,367 deployed strategic warheads

Overall, the United States has decreased its deployed strategic warheads by 433 since New START entered into force in February 2011.

As a result, the disparity in Russian and U.S. deployed strategic warheads is now greater than at any previous time since New START entered into force in 2011: 429 warheads.

It’s important to remind that the counted deployed strategic warheads only represent a portion of the two countries total warhead inventories; we estimate Russia and the United States each have roughly 4,500 warheads in their military stockpiles. The New START treaty only limits how many strategic weapons can be deployed but has no direct effect on the size of the total nuclear stockpiles.

The Russian increase in deployed strategic warheads is temporary due to fielding of several new Borei-class ballistic missile submarines. This picture shows the Vladimir Monomakh arriving at the submarine base near Petropavlovsk on September 27, 2016.

Strategic Launchers

The aggregate data shows that both Russia and the United States continue to reduce their strategic launchers.

Russia has been below the treaty limit of 700 deployed strategic launchers since New START entered into force in 2011. Even so, it continues to reduce its strategic launchers. Thirteen deployed launchers have been removed since March 2016 and Russia overall now has 13 launchers fewer than in 2011.

Russia will have to dismantle another 47 launchers to meet the limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers by February 2018. Those launchers will likely come from retirement of the remaining Delta III SSBNs, retirement of additional Soviet-era ICBMs, and destruction of empty excess ICBM silos.

The United States is not also for the first time below the limit for deployed strategic launchers. The latest data lists 681 launchers deployed, a reduction of 60 compared with March 2016. The reduction reflects the ongoing work to denuclearize excess B-52H bombers, deactivate four excess launch tubes on each SSBN, and remove ICBMs from 50 excess silos.

The United States still has a considerable advantage in deployed strategic launchers: 681 versus Russia’s 508. But the disparity of 173 launchers is smaller than it was six months ago. The United States will need to dismantle another 48 launchers to meet the treaty’s limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers by February 2018.

Strategic Context

The ongoing implementation of the New START treaty is one of the only remaining bright spots on the otherwise tense and deteriorating relationship between Russia and the United States. Despite the current increase of Russian deployed strategic warheads, which is temporary and will be followed by retirement of older systems in the next few years that will reduce the count, Russian compliance with the treaty by 2018 is not in doubt. And both countries continue to reduce their deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers.

In fact, the temporary warhead increase seems to be of little concern to U.S. military planners. DOD concluded in 2012 that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty…”

Equally important are the ongoing onsite inspections and notifications between the United States and Russia. The two countries have each carried out 103 inspections and exchanged 11,817 notifications since the treaty entered into force in 2011. These activities are increasingly important confidence-building measures.

Yet the modest reductions under the treaty must also be seen in the context of the extensive nuclear weapons modernization programs underway in both countries. Although these programs do not constitute a buildup of the overall nuclear arsenal, they are very comprehensive and reaffirm the determination by both Russia and the United States to retain large offensive nuclear arsenals at high levels of operational readiness.

Although those forces are significantly smaller than the arsenals that existed during the Cold War, they are nonetheless significantly larger than the arsenals of any other nuclear-armed state.

Moreover, New START contains no sub-limits, which enables both sides to take advantage of loopholes. Whereas the now-abandoned START II treaty banned multiple warheads (MIRV) on ICBMs, the New START treaty has no such limits, which enables Russia to incorporate MIRV on its new ICBMs and the United States to store hundreds of non-deployed warheads for re-MIRVing of its ICBMs. Russia is developing a new “heavy” ICBM with MIRV and the next U.S. ICBM (GBSD) will be capable of carrying MIRV as well.

Similarly, the “fake” bomber count of attributing only one deployed strategic weapon per bomber despite its capacity to carry many more has caused both sides to retain large inventories of non-deployed weapons to retain a quick upload capability with many hundreds of long-range nuclear cruise missiles. And both sides are developing new nuclear-armed cruise missiles.

How the two countries justify such large arsenals is somewhat of a mystery but seem to be mainly determined by the size of the other side’s arsenal. According to the U.S. State Department, the New START “limits are based on the rigorous analysis conducted by Department of Defense planners in support of the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review.”

Yet a recent GAO analysis of the 2010 NPR force structure found that “DOD officials were unable to provide us documentation of the NPR’s analysis of strategic force structure options that were considered.” Instead, STRATCOM, the Air Force and the Navy conducted their own analysis of options, which were discussed at senior-level meetings but not documented.

Both sides can easily reduce their nuclear forces further and increase security, reduce insecurity, and save money while doing so. Possible steps include: a five-year extension of the New START Treaty, lowering the limits of the existing treaty by one-third while maintaining the inspection regime, and taking unilateral steps to reduce the nuclear weapons modernization programs.

Additional information:

- Status of world nuclear forces

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces 2016

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russia nuclear forces 2016

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Increasing Nuclear Bomber Operations

CBS’s 60 Minutes program Risk of Nuclear Attack Rises described that Russia may be lowering the threshold for when it would use nuclear weapons, and showed how U.S. nuclear bombers have started flying missions they haven’t flown since the Cold War: Over the North Pole and deep into Northern Europe to send a warning to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The program follows last week’s program The New Cold War where viewers were shown unprecedented footage from STRATCOM’s command center at Omaha Air Base in Nebraska.

Producer Mary Welch and correspondent David Martin have produced a fascinating and vital piece of investigative journalism showing disturbing new developments in the nuclear relationship between Russia and the United States.

They were generous enough to consult me and include me in the program to discuss the increasing Cold War and dangerous military posturing.

Nuclear Bomber Operations Context

Just a few years ago, U.S. nuclear bombers didn’t spend much time in Europe. They were focused on operations in the Middle East, Western Pacific, and Indian Ocean. Despite several years of souring relations and mounting evidence that the “reset” with Russia had failed or certainly not taken off, NATO couldn’t make itself say in public that Russia gradually was becoming an adversary once again.

Whatever hesitation was left changed in March 2014 when Vladimir Putin sent his troops to invade Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The act followed years of Russian efforts to coerce the Baltic States, growing and increasingly aggressive military operations around European countries, and explicit nuclear threats against NATO countries getting involved in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

Granted, NATO may not have been a benign neighbor, with massive expansion eastward of new members all the way up to the Russian border, and a consistent tendency to ignore or dismiss Russian concerns about its security interests.

But whatever else Putin might have thought he would gain from his acts, they have awoken NATO from its detour in Afghanistan and refocused the Alliance on its traditional mission: defense of NATO territory against Russian aggression. As a result, Putin will now get more NATO troops along his western and southern borders, larger and more focused military exercises more frequently in the Baltic Sea and Black Sea, increasing or refocused defense spending in NATO, and a revitalization of a near-slumbering nuclear mission in Europe.

Six years ago the United States was this close to pulling its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons out of Europe. Only an engrained NATO nuclear bureaucracy aided by the Obama administration’s lack of leadership prevented the withdrawal of the weapons. Russia has complained about them for years but now it seems very unlikely that the modernization of the F-35A with the B61-12 guided bomb can be stopped. The weapons might even get a more explicit role against Russia, although this is still a controversial issue for some NATO members.

But the U.S. military would much prefer to base the nuclear portion of its extended deterrence mission in Europe on strategic bombers rather than the short-range fighter-bombers forward deployed there. The non-strategic nuclear weapons are far too controversial and vulnerable to the myriads of political views in the host countries. Strategic bombers are free of such constraints.

A New STRATCOM-EUCOM Link

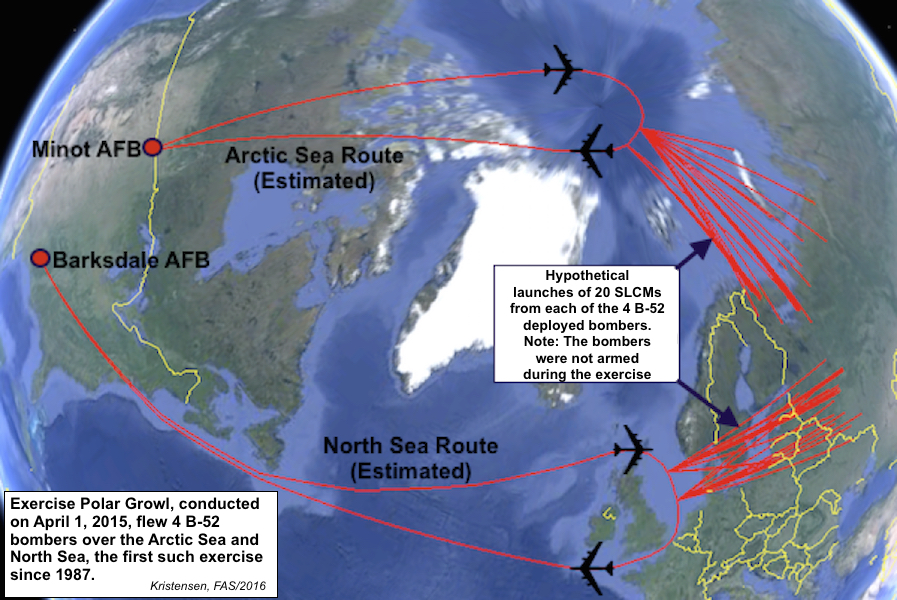

Therefore, even before NATO at the Warsaw Summit this summer decided to reinvigorate its commitment to nuclear deterrence, former U.S. European Command (EUCOM) commander General Philip Breedlove told Congress in February 2015, EUCOM had already “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence [BAAD] missions to NATO regional exercises” as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve to deter Russia.

Less than two months later, on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers took of from their bases in the United States and flew across the North Pole and North Sea in a simulated strike exercise against Russia. The bombers proceeded all the way to their potential launch points for air-launched cruise missiles before they returned to the United States. Such an exercise had not been conducted since the late-1980s against the Soviet Union. Combined, the four bombers could have delivered 80 long-range nuclear cruise missiles with a combined explosive power of 800 Hiroshima bombs.

During Exercise Polar Growl on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers flew along two routes into the Arctic and North Sea regions that appeared to simulate long-range strikes against Russia. The four bombers were capable of launching up to 80 nuclear air-launched cruise missiles with a combined explosive power equivalent to 800 Hiroshima bombs. All routes are approximate.

Despite its strategic implications, Polar Growl also had a distinctive regional – even limited – objective because of the crisis in Europe. Planning for such regional deterrence scenarios have taken on a new importance during the past couple of decades and they have become central to current planning because it is in such regional scenarios that the United States believes it is most likely that nuclear weapons could actually be used.

“The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, in 2014 predicted only a few weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, “and continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.”

Two weeks after the bombers returned from Polar Growl, Robert Scher, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities, told Congress: “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts.” This includes “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

Nuclear Conventional Integration

Much of this increased planning involves conventional weapons such as the new long-range conventional JASSM-ER cruise missile, but the planning also involves nuclear. In fact, conventional and nuclear appear to be integrating in a way they have done before. This effort was described recently by Brian McKeon, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, during the annual STRATCOM Deterrence Symposium:

In the Department of Defense we’re working to effectively integrate conventional and nuclear planning and operations. Integration is not new but we’re renewing our focus on it because of recent developments and how we see potential adversaries preparing for conflict. This is an area where the focus in Omaha has really led the way and I want to commend Admiral Haney and STRATCOM for being able to shift planning so quickly toward this approach and thinking though conflict. No one wants to think about using nuclear weapons and we all know the principle role of nuclear weapons is to deter their use by others. But as we’ve seen, out adversaries may not hold the same view.

Let me be clear that when I say integration I do not mean to say we have lowered the threshold for nuclear use or would turn to nuclear weapons sooner in a conventional campaign. As we stated in the Nuclear Posture Review, the United States will “only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.” The NPR also emphasized the importance of reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, a requirement that has been advanced in our planning consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance, including with non-nuclear strike options.

What I mean by integration is synchronizing our thinking across all domains in a way that maximizes the credibility and flexibility of our deterrent through all phases of conflict and responds appropriately to asymmetrical escalation. For too long, crossing the nuclear threshold was through to move a nuclear conflict out of the conventional dimension and wholly into the nuclear realm. Potential adversaries are exploring ways to cross this threshold with low-yield nuclear weapons to test out resolve, capabilities, and Allied cohesion. We must demonstrate that such a strategy cannot succeed so that it is never attempted. To that end we’re planning and exercising our non-nuclear operations conscious of how they might influence an adversary’s decision to go nuclear.

We also plan for the possibility of ongoing U.S. and Allied operations in a nuclear environment and working to strengthen resiliency of conventional operations to nuclear attack. By making sure our forces are capable of continuing the fight following a limited nuclear use we preserve flexibility for the president. And by explicitly preparing for the implication of an adversary’s limited nuclear use and providing credible options for the President, we strengthen our deterrent and reduce the risk of employment in the first instance.

Regional nuclear scenarios no longer primarily involve planning against what the Bush administration called “rogue states” such as North Korea and Iran, but increasingly focus on near-peer adversaries (China) and peer adversaries (Russia). “We are working as part of the NATO alliance very carefully both on the conventional side as well as meeting as part of the NPG [Nuclear Planning Group] looking at what NATO should be doing in response to the Russian violation of the INF Treaty,” Scher explained.

STRATCOM last updated the strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) in 2012 and is currently about to publish an updated version that incorporates the changes caused by the Obama administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy from 2013.

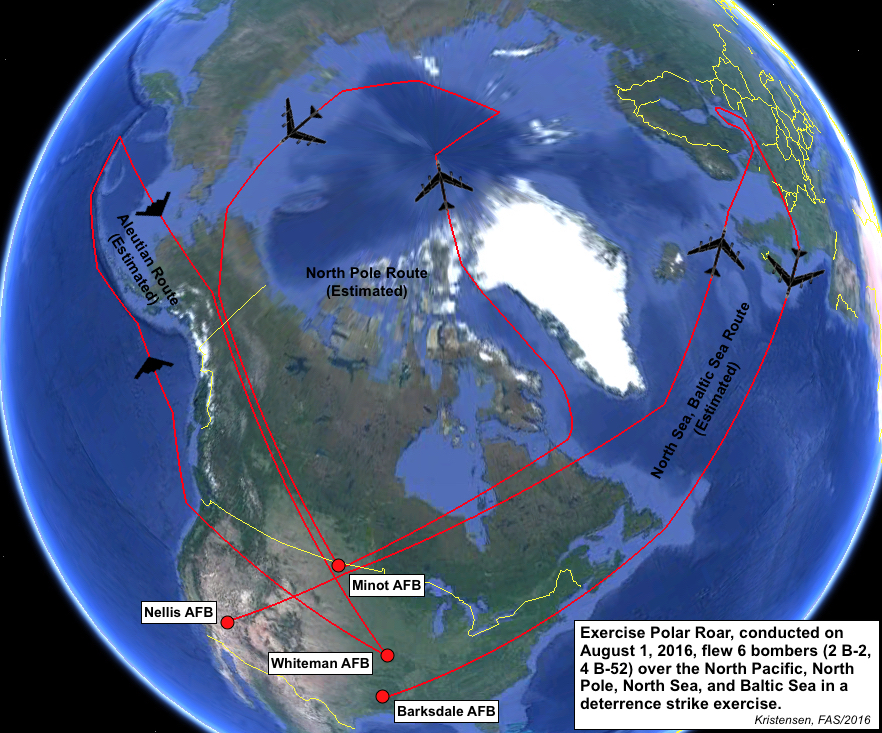

Two months ago, a little over a year after Polar Growl, another bomber strike exercise was launched. This time six bombers (4 B-52s and 2 B-2s) flew closer to Russia and simultaneously over the Arctic Sea, North Sea, Baltic Sea, and North Pacific Ocean. The six Polar Roar sorties required refueling support from 24 KC-135 tankers as well as E4-B Advanced Airborne Command Post and E-6B TACAMO nuclear command and control aircraft.

The routes (see below) were eerily similar to the Chrome Dome airborne alert routes that were flown by nuclear-armed bombers in the 1960s against the Soviet Union.

Exercise Polar Roar on August 1, 2016, followed Exercise Polar Growl from 2015 but involved more bombers, both nuclear-capable and conventional-only, and flew closer to Russia and deep into the Baltic Sea. Polar Roar also included B-2 stealth bombers in the North Pacific. All routes are approximate.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Navy Builds Underground Nuclear Weapons Storage Facility; Seattle Busses Carry Warning

Seattle busses warn of largest nuclear weapons base. Click image to see full size.

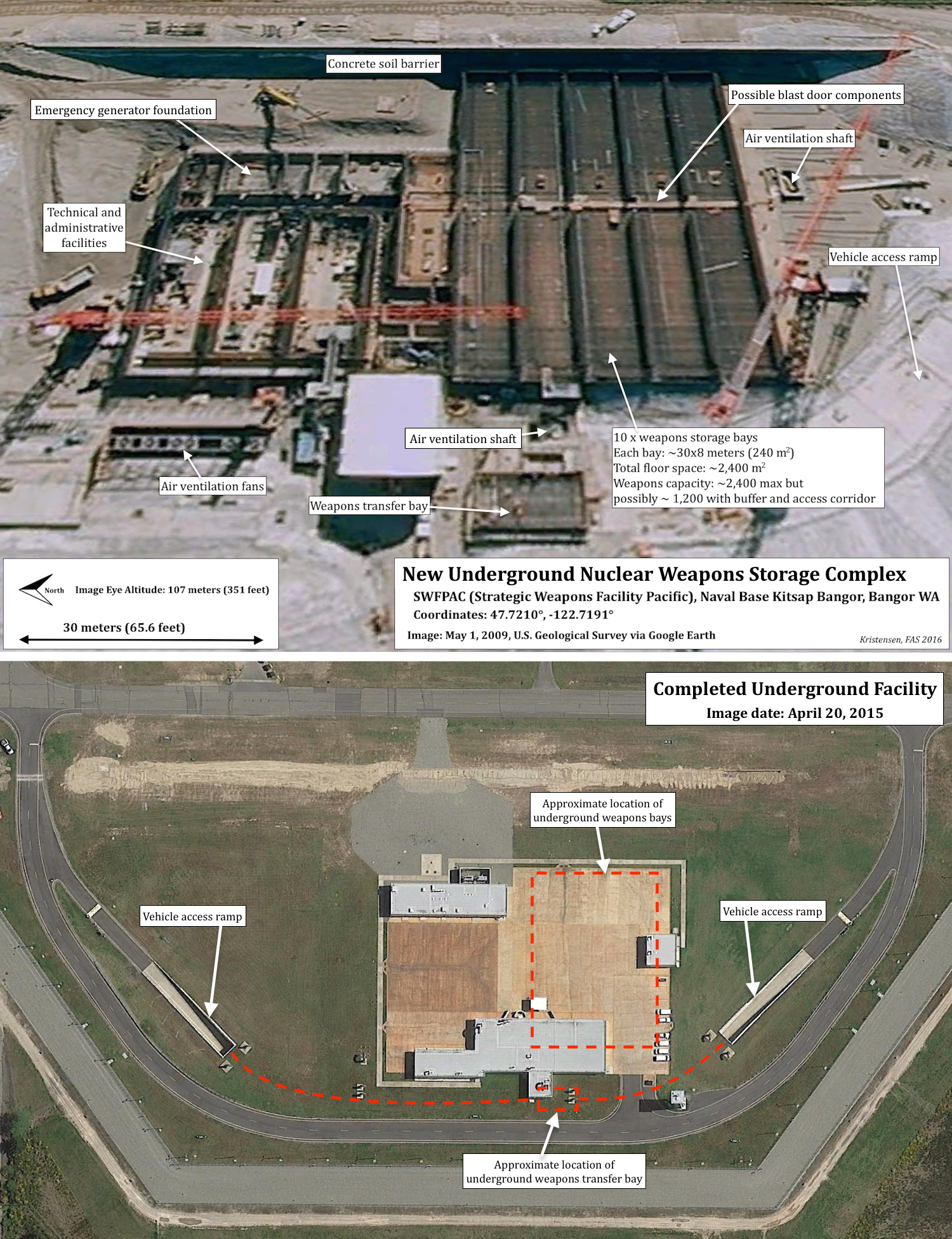

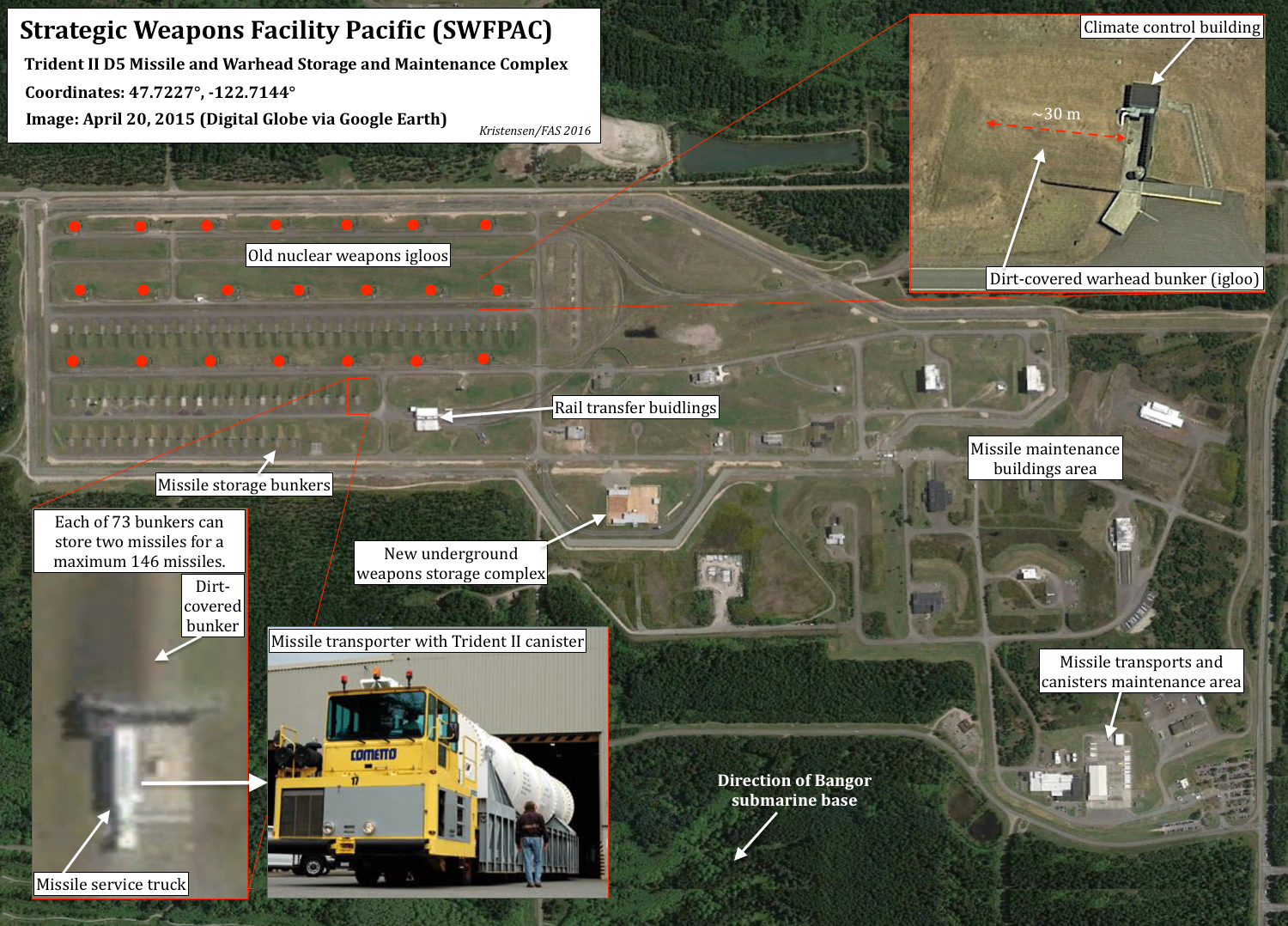

The US Navy has quietly built a new $294 million underground nuclear weapons storage complex at the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC), a high-security base in Washington that stores and maintains the Trident II ballistic missiles and their nuclear warheads for the strategic submarine fleet operating in the Pacific Ocean.

The SWFPAC and the eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) homeported at the adjacent Bangor Submarine Base are located only 20 miles (32 kilometers) from downtown Seattle. The SWFPAC and submarines are thought to store more than 1,300 nuclear warheads with a combined explosive power equivalent to more than 14,000 Hiroshima bombs.

A similar base with six SSBNs is located at Kings Bay in Georgia on the US east coast, which houses the SWFLANT (Strategic Weapons Facility Atlantic) that appears to have a dirt-covered warhead storage facility instead of the underground complex built at SWFPAC. Of the 14 SSBNs in the US strategic submarine fleet, 12 are considered operational with 288 ballistic missiles capable of carrying 2,300 warheads. Normally 8-10 SSBNs are loaded with missiles carrying approximately 1,000 warheads.

To bring public attention to the close proximity of the largest operational nuclear stockpile in the United States, the local peace group Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action has bought advertisement space on 14 transit buses. The busses will carry the posters for the next eight weeks. FAS is honored to have assisted the group with information for its campaign.

The Limited Area Protection and Storage Complex

Although the new underground storage complex is not a secret – its existence has been reported in public navy documents since 2003 – it has largely escaped public attention until now.

The new complex is officially known as the Limited Area Protection and Storage Complex (LAPSC), or navy construction Project Number P973A. The complex was originally estimated to cost $110 million but ended up costing nearly $294 million.

The US Navy describes the complex as “a reinforced concrete, underground, multi-level re-entry body processing and storage facility” with “hardened floors, and hardened load-bearing walls and roof.” Glen Milner at the Ground Zero Center helped locate some of the budget documents. Other construction details provided by the navy further describe the complex as:

A 16,000-m2 [180,000 square feet] multi-level, underground, hardened, blast-resistant, reinforced concrete structure, with approximate dimensions of 110 meters long by 82 meters wide. Two tunnels (approximately 122 meters long, 6 meters wide, and 6 meters tall) will provide heavy vehicle access to and from the LAPSC. An aboveground portion of the facility will provide administrative and utility support spaces. Special features of the facility include: power-operated physical security and blast-resistant doors, TEMPEST shielded rooms, seven (7) overhead bridge cranes (2 ton capacity), three (3) elevators, lightning protection system, grounding system, liquid waste collection/retention system, emergency air purge system, fire protection systems, and multiple HVAC systems. This project will also provide a new 1000 kW emergency generator (enclosed within a new hardened, reinforced concrete structure), two security guard towers, lightning protection, utilities, and other site improvements. The existing Limited Area perimeter fence, security zone, and patrol roads will be expanded to encompass the new LAPSC.

The underground complex is similar to the general design of the large underground nuclear weapons storage facility Kirtland AFB in New Mexico, known as Kirtland Underground Munitions Storage Complex (KUMSC) – except KUMSC appears to be four times bigger than the SWFPAC complex. It appears to include 10 weapons storage bays (each 30 x 8 meters; 98 x 26 feet) where nuclear W76 and W88 warheads in their containers will be stored when they’re not deployed on submarines (see image analysis below).

New underground nuclear weapons storage site at Naval Base Kitsap. Click to view full size.

The primary building contractor, Ammann & Whitney, describes the unique blast doors and gas-tight features intended to ensure the safe storage and handling of the nuclear weapons:

The structures are reinforced concrete containment structures designed to withstand both interior and exterior explosions. All exterior penetrations and blast doors are gas-tight. There are a total of 24 blast doors; 12 are located in the above ground structures and 12 in the buried structure. All 12 doors in the above ground structures are subject to exterior blast loads while seven are subject to additional internal gas loads. Of the 12 doors in the buried structure, six doors are subject to blast loads from both sides, the remaining six are subject to blast loads from one side only but three must be gas-tight. Penetrations from the buried structure are blast resistant and gas-tight.

Design of the complex began in 2002, construction in 2007, and by 2009 the excavation and main outlines were clearly visible on satellite images. The complex was completed in 2012. Construction required enormous amounts of concrete. Over an 18-month period between December 2008 and mid-2010, for example, two hundred cement trucks entered the base every two weeks.

Nuclear weapon at SWFPAC were previously stored in above-ground earth-covered bunkers, or igloos, from where they were transported to two above-ground handling facilities for maintenance or for loading onto Trident II sea-launched ballistic missiles for deployment on operational SSBNs.

But the navy has concluded that a “single underground protected structure provides the most robust protection for fulfilling this mission against all threats.” With the completion of the underground complex, the old surface facilities (2 handling buildings and 21 igloos) will be demolished (see site outline above).

The US Navy plans to operate nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines at Naval Base Kitsap at least through 2080.

Over the next could couple of years the navy will “convert” four of the 24 missile launch tubes on each SSBN. The conversion will remove the capability to launch missiles from the four tubes, which no longer count under the New START treaty. The 384 excess warheads associated with the 24 missiles will likely be dismantled, leaving roughly 1,000 warheads at SWFPAC.

In the longer term (in the 2030s), the US Navy will transition to a new fleet of 12 SSBNs that will replace the current 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Each of the new submarines will only carry 16 missiles, a reduction of an additional four tubes from the 20 left on the New START compatible SSBNs. Assuming seven of the 12 new SSBNs will be based at Bangor, that will leave 112 missiles with an estimated 896 warheads at SWFPAC and Bangor submarine base, or a reduction of about one-third of the warheads currently stored there.

Despite these expected reductions, the Naval Base Kitsap complex (the SWFPAC and Bangor submarine base) will remain the largest and most important nuclear weapons base in the United States for the foreseeable future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Flawed Pentagon Nuclear Cruise Missile Advocacy

The Pentagon is using flawed arguments to sell a nuclear cruise missile to President Obama?

By Hans M. Kristensen

In its quest to secure Congressional approval for a new nuclear cruise missile, the Pentagon is putting words in the mouth of President Barack Obama and spinning and overstating requirements and virtues of the weapon.

Last month, DOD circulated an anonymous letter to members of Congress after it learned that Senator Dianne Fenstein (D-CA) was planning an amendment to the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act to put limits on funding and work on the new Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) nuclear air-launched cruise missile. The letter not surprisingly opposes the limits but contains a list of amazingly poor justifications for the new weapon.

The letter follows another letter in March from Under Secretary of Defense Frank Kendall to Senator John McCain that contains false claims about official documents endorsing the LRSO, as well a vague and concerning statements about the mission and purpose of the weapon.

The two letters raise serious questions about DOD’s justifications for the LRSO and Congress’ oversight of the program.

About That Strategy…

The DOD letter circulated to Congress in May presents surprisingly poor arguments in defense of the LRSO. In response to Senator Feinstein asking the Pentagon to show “the types of targets the LRSO is needed to destroy that cannot also be destroyed by existing U.S. nuclear and conventional weapons, “ DOD spins off into an off-topic, incoherent, and vague defense for retaining different nuclear capabilities in the arsenal:

Using the ability to destroy the target as the sole metric would also fail to address the dependence of effective deterrence on possessing credible options for responding to adversary attacks. A strategy of relying on large-scale or high-yield response options is credible and effective for deterring large-scale nuclear attack, particularly against the U.S. homeland, but it is less credible in the context of limited adversary use against an ally or U.S. forces operating abroad. Maintaining a credible ability to respond to a limited as well as large-scale nuclear attack against the United States or our allies strengthens our ability to deter such attacks from ever taking place.

But Feinstein’s draft amendment doesn’t say that destruction of the target is or should be “the sole metric” for deterrence. Even so, the bottom line for an effective nuclear deterrent is the credible capability to hold at risk the targets that an adversary values most. One can try to do that in many different ways, of course, but the DOD letter’s portrayal of an either-or choice between “large-scale or high-yield response options” against large attacks or limited-scale and lower-yield response options to limited adversary attacks is obviously a strawman argument because no one – certainly not Feinstein’s draft resolution – is arguing that the United States should eliminate its large inventory of lower-yield gravity bombs on heavy bombers and dual-capable fighter bombers. The US nuclear arsenal would still be able to provide limited and lower-yield options if the LRSO were canceled.

Next the DOD May letter tries to paint the LRSO decision as a choice between nuclear and non-nuclear weapons:

We do not and should not think of nuclear weapons as just another tool for destroying a target. The President’s guidance directs that [sic] DoD to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through non-nuclear strike options, but also recognizes the unique contribution of nuclear weapons to our overall deterrence strategy. For example, the President might require a nuclear response to a nuclear attack in order to restore deterrence and prevent further attacks, even if a conventional weapon could also destroy the target.

This is another strawman argument because Feinstein’s draft amendment does not call for the elimination of all nuclear weapons or gravity bombs on heavy bombers and dual-capable fighter-bombers. Those weapons would of course still provide limited escalation-control options if the LRSO were canceled. Not to mention what non-nuclear cruise missiles could accomplish.

Next the DOD May letter gets into the obscure issue of “hedging” where multiple warhead types are used to provide backup against possible failure of one of them. I won’t go into a detailed analysis of hedging (Union of Concerned Scientists has a good report here) but critique the claims made in the DOD letter:

Requiring that only one warhead type is suitable for a given target also misses the LRSO’s critical role in providing the ability to hedge against significant geopolitical or technical issues. An effective bomber force with standoff capability can be put on alert in response to a serious technical problem in another leg of the Triad, or if the nature of the threat changes suddenly. Reliance on a single warhead type would threaten the stability of our deterrence posture, and would have changed the approach required for negotiating the New START Treaty with Russia.

The Feinstein draft amendment does not argue “that only one warhead is suitable for a given target” but asks for clarity about what the LRSO targets are that cannot also be destroyed by other existing nuclear or conventional weapons. That’s a reasonable question when someone is asking you to pay for a weapon that might cost $20 to $30 billion dollars over its lifetime.

But an effective bomber force does not require the LRSO to hedge. A force that includes 20 B-2 and 100 B-21 stealthy bombers (60 of them equipped with nearly 500 B61-12 gravity bombs) would still provide a considerable hedging capability against a serious technical problem in another leg of the Triad. Under the New START Treaty force structure the ICBMs are planned to deploy 400 warheads and the SLBMs 1,090 warheads.

However, the bomber hedging argument is weak. Under the Pentagon’s so-called 3+2 warhead plan (which is actually a 6+2 warhead plan according to a 2015 JASONs study), billions of dollars will be spent on building six new warhead types for the two ballistic missile legs partially to hedge against warhead failures on each other. So if the two ballistic legs are already designed to hedge each other, why are bomber weapons needed to hedge them as well? It sounds more like the Pentagon is using the hedge argument as a way to get the LRSO.

It is also amazing to see DOD bluntly advocating that the “bomber force with standoff capability can be put on alert… if the nature of the threat changes suddenly.” The bombers were taken off alert in 1991 and the Pentagon strongly argues against the dangers of rapidly increasing the alert level of nuclear forces.

The Kendall letter from March also defends the LRSO because it gives the Pentagon the ability to rapidly increase the number of deployed warheads significantly on its strategic launchers. He does so by bluntly describing it as a means to exploit the fake bomber weapon counting rule (one bomber one bomb no matter what they can actually carry) of the New START Treaty to essentially break out from the treaty limit without formally violating it:

Additionally, cruise missiles provide added leverage to the U.S. nuclear deterrent under the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. The accounting rules for nuclear weapons carried on aircraft are such that the aircraft only counts as one weapon, even if the aircraft carries multiple cruise missiles.

It is disappointing to see a DOD official justifying the LRSO as a means to take advantage of a loophole in the treaty to increase the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons above 1,550 warheads. Not least because the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy determined that the Pentagon, even when the New START Treaty is implemented in 2018, will still have up to one-third more nuclear weapons deployed than are needed to meet US national and international security commitments.

Finally, the DOD May letter also takes issue with the Feinstein draft resolution demand to certify that the sole objective of the LRSO is to deter nuclear attack. This would be inconsistent with the Administration’s nuclear weapons policy and the President’s guidance on nuclear employment, DOD says. Even though the NPR and guidance both affirmed that “the fundamental purpose of all U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack,” they also determined that a sole-purpose nuclear policy can not be adopted yet because there “remains a narrow range of contingencies in which U.S. nuclear weapons may still play a role in deterring a conventional or CBW attack against the United States or its allies and partners.”

The public DOD report on the 2013 guidance does not mention the “role in deterring a conventional or CBW attack” that the NPR specifies. And there are rumors that the guidance removed the requirement to plan nuclear missions against chemical weapons attacks. If so, that would leave only biological and conventional attacks other than nuclear attacks as a role for US nuclear weapons. Deterring biological attacks is thought to remain a mission because of the widespread human casualties such weapons can cause. And conventional might for example refer to a devastating North Korean conventional attack against Seoul or a Russian conventional attack against Eastern European NATO allies. But it is unclear and such attacks would in any case almost certainly be more likely to trigger non-nuclear responses; why would the US escalate to nuclear use if no one else has?

It is curious why Senator Feinstein chose the wording “sole objective” given that the NPR and guidance both clearly rejected a “sole purpose of nuclear weapons” for now (although the policy is to “work to establish conditions under which such a policy could be safely adopted”). She must have known that it would be easily rejected.

But it is also possible that what she was really after was a way to limit the almost tactical warfighting mission of the LRSO that numerous officials have widely described in public statements. Only a week after Kendall sent his LRSO letter to Senator McCain, Senator Feinstein said during a hearing:

The so-called improvements to this weapon seemed to be designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war. I find that a shocking concept. I think this is really unthinkable, especially when we hold conventional weapons superiority, which can meet adversaries’ efforts to escalate a conflict. (Emphasis added.)

The two DOD letters seem to confirm Senator Feinstein’s worst fears. The Kendall letter speaks of “flexible options across the full range of threat scenarios” with “multi-axis” attacks, and the DOD May letter talks about using “lower-yield” options in limited regional scenarios “even if a conventional weapon could also destroy the target.”

About Those Claims…

The Kendall letter, first published by Union of Concerned Scientists, makes numerous claims about official documents endorsing the LRSO. But when you check the documents, it turns out that they don’t explicitly endorse the weapon. Some don’t even mention it.

For example, Kendall claims that the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review “committed to maintaining a viable standoff nuclear deterrent for the air leg of the Triad…” But the NPR made no such commitment. The pubic version of the NPR only stated that “the Air Force will conduct an assessment of alternatives to inform decisions in FY 2012 about whether and (if so) how to replace the current air-launched cruise missile (ALCM)…” (Emphasis added). Contrary to Kendall’s claim, there is no explicit commitment in the public NPR to a nuclear cruise missile capability beyond the lifespan of the current ALCM.

Kendall also claims that the 2014 Nuclear Enterprise Review “committed to maintaining a viable standoff nuclear deterrent for the air leg of the Triad…” But that is also wrong. The public version of the document does not mention a cruise missile replacement at all but instead acknowledges “a moderate public attack on the need for the cruise missile carrying B-52 force…”

In terms of how the LRSO aligns with US nuclear employment strategy, the Kendall letter also explains that the DOD report Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, to which President Obama provided the foreword, “reaffirmed the need for U.S. forces to project power and hold at risk any target at any location on the globe, to include anti-access and area denial environments.”

That may be so but neither the DOD report nor President Obama’s foreword mention a requirement for a nuclear cruise missile with one word. Instead, here is what the report says:

Project Power Despite Anti-Access/Area Denial Challenges. In order to credibly deter potential adversaries and to prevent them from achieving their objectives, the United States must maintain its ability to project power in areas in which our access and freedom to operate are challenged… Accordingly, the U.S. military will invest as required to ensure its ability to operate effectively in anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) environments. This will include implementing the Joint Operational Access Concept, sustaining our undersea capabilities, developing a new stealth bomber, improving missile defenses, and continuing efforts to enhance the resiliency and effectiveness of critical space-based capabilities.

On the same issue, President Obama’s foreword states:

As we end today’s wars and reshape our Armed Forces, we will ensure that our military is agile, flexible, and ready for the full range of contingencies. In particular, we will continue to invest in the capabilities critical to future success, including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; counterterrorism; countering weapons of mass destruction; operating in anti-access environments; and prevailing in all domains, including cyber.

Neither the DOD report nor Obama’s foreword makes any explicit commitment to a new nuclear cruise missile. Yet Kendall nonetheless uses them both to argue for one.

Humanitarian Crocodile Tears

The DOD May letter contains some really interesting statements about nuclear weapons and international law and collateral damage. The letter argues that not acquiring the LRSO would be “inconsistent with Administration policy and Presidential guidance” because the June 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance “directs that all plans must apply the principles of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian populations and civilian objects.”

According to the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy report DOD sent to Congress in June 2013, the guidance “makes clear that all plans must also be consistent with the fundamental principles of the Law of Armed Conflict. Accordingly, plans will, for example, apply the principles of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian populations and civilian objects. The United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or civilian objects.”

This has been US policy for several decades but it is great that it was included in the new guidance. And it is even better if it actually restrains nuclear strike planning. But the authors of the DOD May letter forget to mention that even if the Obama administration were to cancel the LRSO, the Pentagon still plans to retain nearly 500 nuclear gravity bomb with lower yields for delivery by heavy bombers and dual-capable fighter-bombers. Retiring the ALCM or canceling the LRSO would not be incompatible with the guidance.

Yet the May letter illustrates how the new guidance is already being used by nuclear advocates in a twisted effort to use concern about civilian casualties in war as an argument against retiring existing nuclear weapons and to justify acquisition of new nuclear weapons that are more accurate with better lower-yield options to reduce radioactive fallout from nuclear attacks. The LRSO is one example; the B61-12 gravity bomb is another. As STRATCOM commander Gen. Robert Kehler told Congress in 2013 shortly after the guidance was published, “…we are trying to pursue weapons that actually are reducing in yield because we’re concerned about maintaining weapons that would have less collateral effect if the President ever had to use them.” (Emphasis added.)

“Electing to retire a lower-yield option because a higher-yield weapon can also destroy the target would be inconsistent with this principle and direction,” the DOD May letter concludes.

What makes this newfound “humanitarian” concern of the nuclear planners particularly hypocritical is that they don’t use the same guidance to conclude that the thousands of high-yield nuclear warheads on ICBMs and SLBMs therefore would be equally “inconsistent with Administration policy and Presidential guidance.”

Apparently, limiting damage to civilians is only worth it if you can get a better weapon in return.

Conclusions and Recommendations

It is the responsibility of the Pentagon to advocate for nuclear forces but this should also require it to have clear and valid justifications for why it needs them. The March letter from DOD’s Frank Kendall and the anonymous DOD letter from May arguing for why the Congress should approve and pay for the LRSO clearly fall short of that standard. Instead, they are full of false claims, spin, and vague and overstated assertions about its mission.

The scary part of this is that a majority in Congress appears to have accepted these poor justifications for the LRSO. The majority leadership in the Senate Armed Services Committee recently rejected an amendment by Senator Edward Markey to delay funding for the LRSO to allow Congress to better study the justifications. The rejection made use of many of the same false claims, spin, and vague overstatements that the DOD letters contain.

The DOD May letter rejecting Senator Feinstein’s draft amendment insisted that the LRSO Assessment of Alternative provided to Congress in 2014 “does not and should not address why we have an airborne standoff leg of the Triad,” and that the AoA therefore “only examined technical options to meet an air-based stand-off strategy in a cost and mission-effective manner.”

But then, in the next sentence, DOD essentially told the lawmakers that unless they approved more money for the LRSO program to advance it further, they cannot be told what the cost will be.

This is tantamount to blackmailing and wrong because several officials privately have said that they have already seen preliminary briefings on estimated life-cycle costs for both the LRSO missile and W80-4 warhead.

Providing false claims, spin, and vague overstatements about the requirements and mission of the LRSO is bad enough. But unless President Obama during his remaining time in office decides to cancel the LRSO program, it could end up costing the taxpayers $20-$30 billion over the lifetime of the weapon for a nuclear weapon the United States doesn’t need.

Further reading about the LRSO:

- Questions About The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

- Forget LRSO; JASSM-ER Can Do The Job

- LRSO: The Nuclear Cruise Mission

- W80-1 Warhead Selected For New Nuclear Cruise Missile

- B-2 Stealth Bomber To Carry New Nuclear Cruise Missile

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Briefing to Arms Control Association Annual Meeting

Yesterday I gave a talk at the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting: Global Nuclear Challenges and Solutions for the Next U.S. President. A full-day and well-attended event that included speeches by many important people, including Ben Rhodes, who is Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications in the Obama administration.

My presentation was on the panel “Examining the U.S. Nuclear Spending Binge,” which included Mark Cancian from CSIS, Amy Woolf from CRS, and Andrew Weber, the former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. I was asked to speak about the enhancement of nuclear weapons that happens during the nuclear modernization programs and life-extension programs and the implications these improvement might have for strategic stability.

My briefing described enhancement of military capabilities of the B61-12 nuclear bomb, the new air-launched cruise missile (LRSO), and the W76-1 warhead on the Trident submarines. The briefing slides are available here:

Nuclear Modernization, Enhanced Military Capabilities, and Strategic Stability.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Nuclear Stockpile Numbers Published Enroute To Hiroshima

The mushroom cloud rises over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, as the city is destroyed by the first nuclear weapon ever used in war.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Shortly before President Barack Obama is scheduled to arrive for his historic visit to Hiroshima, the first of two Japanese cities destroyed by U.S. nuclear bombs in 1945, the Pentagon has declassified and published updated numbers for the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile and warhead dismantlements.

Those numbers show that the Obama administration has reduced the U.S. stockpile less than any other post-Cold War administration, and that the number of warheads dismantled in 2015 was lowest since President Obama took office.

The declassification puts a shadow over the Hiroshima visit by reminding everyone about the considerable challenges that remain in reducing excessive nuclear arsenals – not to mention the daunting goal of eliminating nuclear weapons altogether.

Obama’s Stockpile Reductions

The declassified data shows that the stockpile as of September 2015 included 4,571 warheads. That means the Obama administration so far has reduced the stockpile by 702 warheads (or 13 percent) compared with the last count of the Bush administration.

Although 702 warheads is no small number (other than Russia, no other nuclear-armed state has more than 300 warheads), the reduction constitutes the smallest reduction of the stockpile achieved by any previous post-Cold War administration (see table).

The declassified 2015 number is about 100 warheads lower than the number we estimated in our latest Nuclear Notebook. The reason for the difference is that the number of warheads retired in 2014-2015 turned out to be higher than the average retirement in the previous three-year period. The increase probably reflects a quicker than anticipated retirement of excess warheads for the navy’s Trident missiles.

It can be deceiving to assess stockpile reduction performance by only comparing numbers of warheads. After all, there are significantly fewer warheads left in the stockpile today compared with 1991 (in fact, 14,437 warheads fewer!) so why wouldn’t the Obama administration be retiring fewer warheads than previous post-Cold War administrations?

To overcome that bias we also compare the reductions in terms of the percentage the stockpile size changed during the various administrations. But even so, the Obama administration’s performance comes in significantly below that of all other post-Cold War administrations (see table).

Obama’s Dismantlements

The declassified numbers also show that the Obama administration last year only dismantled 109 retired warheads. This is the lowest number of warheads dismantled in any year President Obama has been in office. And it appears to be the lowest number dismantled by the United States in one year since at least 1970.

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) says the poor performance in 2015 was due to “safety reviews, unusually high lightning events, and a worker strike at Pantex.”

But the decrease cannot be explained simply as disturbances. Although 2015 was unusually low, the Obama administration’s dismantlement record clearly shows a trendline of fewer and fewer warheads dismantled (see table).

Nuclear warhead dismantlement has decreased during the Obama administration. Click to view full size

There are currently roughly 2,300 retired warheads awaiting dismantlement, most of which were retired prior to 2009. NNSA says it plans to “increase weapons dismantlement by 20 percent starting in FY 2018” to be able to complete dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 before the end of September 2021.

With the Obama administration’s average of about 280 warheads dismantled per year, it will take at least until 2024 before the total current backlog is dismantled. The several hundred additional warheads that will be retired before then will take several additional years to dismantle.