Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

Federation of American Scientists Researchers Contribute Nuclear Weapons Expertise to International SIPRI Yearbook, Out Today

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) launches its annual assessment of the state of armaments, disarmament and international security

Washington, D.C. – June 16, 2025 – Nuclear weapons researchers at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) contributed to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s annual Yearbook, released today. Key findings of SIPRI Yearbook 2025 are that a dangerous new nuclear arms race is emerging at a time when arms control regimes are severely weakened.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “Instead, we see a clear trend of growing nuclear arsenals, sharpened nuclear rhetoric and the abandonment of arms control agreements.”

World’s nuclear arsenals being enlarged and upgraded

Nearly all of the nine nuclear-armed states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and Israel—continued intensive nuclear modernization programmes in 2024, upgrading existing weapons and adding newer versions.

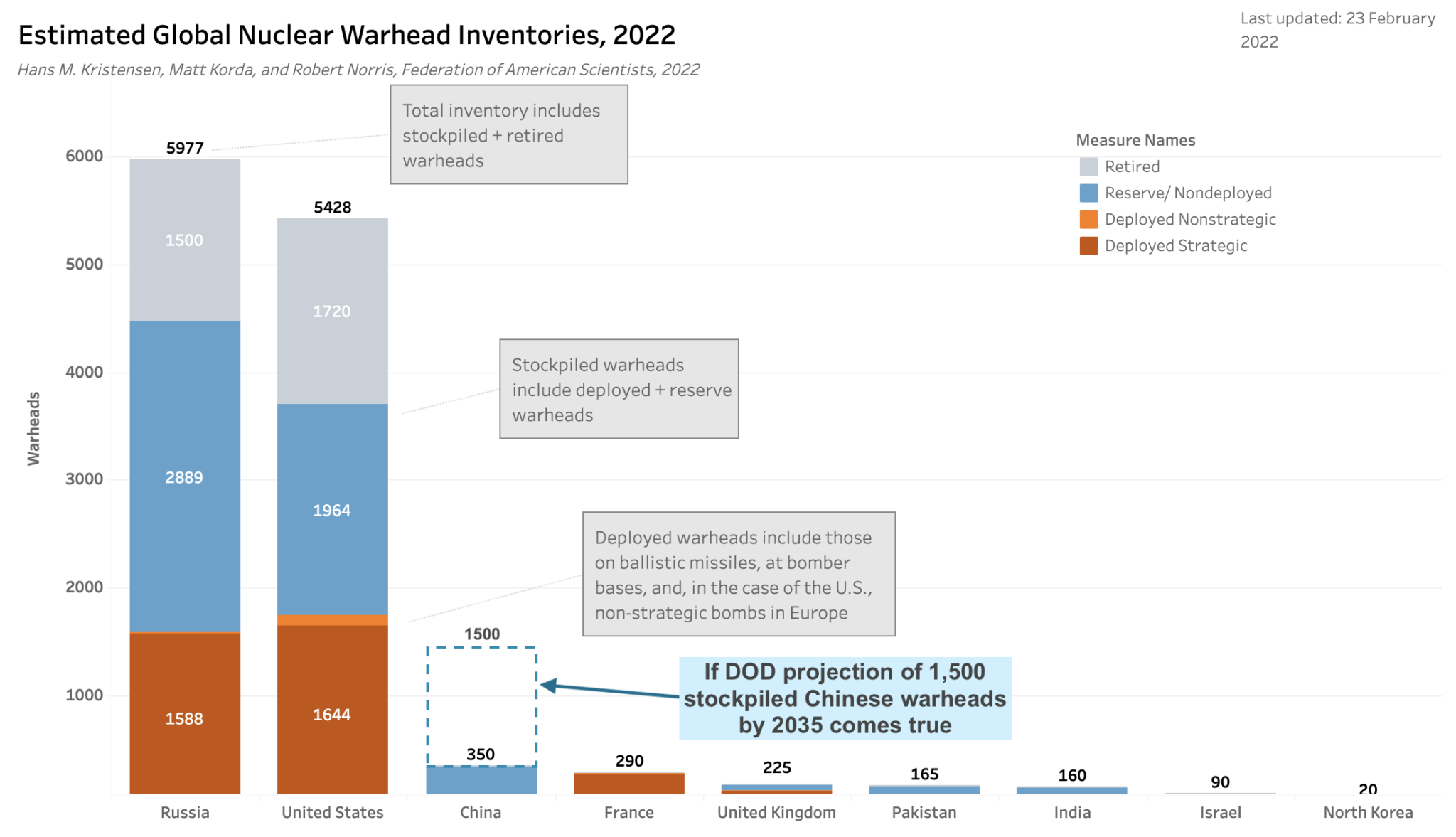

Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,241 warheads in January 2025, about 9614 were in military stockpiles for potential use (see the table below). An estimated 3912 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft and the rest were in central storage. Around 2100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the USA, but China may now keep some warheads on missiles during peacetime.

Since the end of the cold war, the gradual dismantlement of retired warheads by Russia and the USA has normally outstripped the deployment of new warheads, resulting in an overall year-on year decrease in the global inventory of nuclear weapons. This trend is likely to be reversed in the coming years, as the pace of dismantlement is slowing, while the deployment of new nuclear weapons is accelerating.

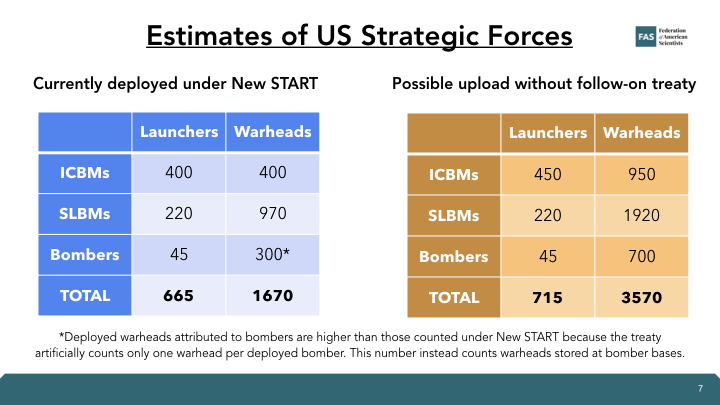

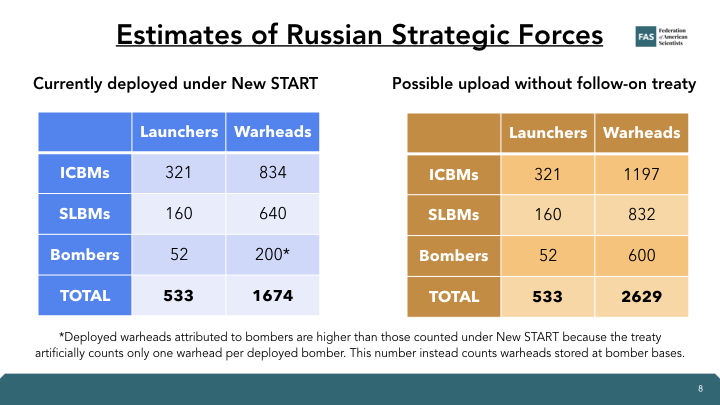

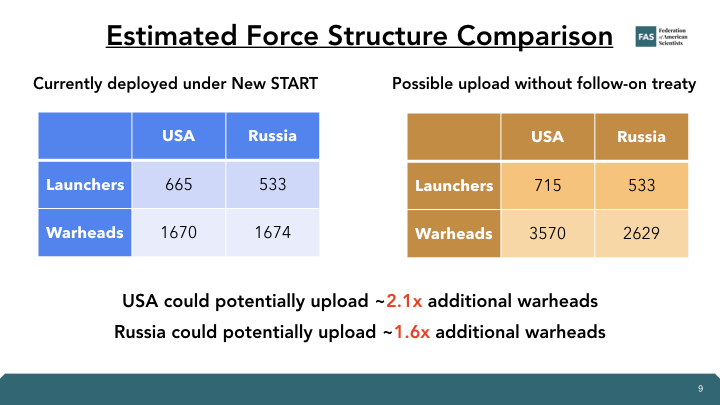

Russia and the USA together possess around 90 per cent of all nuclear weapons. The sizes of their respective military stockpiles (i.e. useable warheads) seem to have stayed relatively stable in 2024 but both states are implementing extensive modernization programmes that could increase the size and diversity of their arsenals in the future. If no new agreement is reached to cap their stockpiles, the number of warheads they deploy on strategic missiles seems likely to increase after the bilateral 2010 Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START) expires in February 2026.

The USA’s comprehensive nuclear modernization programme is progressing but in 2024 faced planning and funding challenges that could delay and significantly increase the cost of the new strategic arsenal. Moreover, the addition of new non-strategic nuclear weapons to the US arsenal will place further stress on the modernization programme.

Russia’s nuclear modernization programme is also facing challenges that in 2024 included a test failure and the further delay of the new Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and slower than expected upgrades of other systems. Furthermore, an increase in Russia’s non-strategic nuclear warheads predicted by the USA in 2020 has so far not materialized.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Federation of American Scientists Releases Latest United States Edition of Nuclear Notebook

Washington, D.C. – January 13, 2025 – Today, the Federation of American Scientists released “United States Nuclear Weapons, 2025”—its estimate and analysis of the U.S. nuclear weapons arsenal. The annual report, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, estimates that the United States maintains a stockpile of approximately 3,700 warheads, about 1,700 of which are deployed.

Under several successive presidential administrations, the United States has pursued an ambitious nuclear modernization program, including upgrades to each leg of its nuclear arsenal. Under the Biden administration, however, the debate has shifted to begin assessing ways that the United States could potentially increase the number of nuclear weapons that could be deployed on its current launchers by uploading more warheads.

Despite mounting cost overruns and program delays in its nuclear modernization efforts, the incoming Trump administration has signaled it may pursue additional nuclear weapons programs and further expand the role that these weapons play in U.S. military strategy, based in part on the recommendations of the 2023 Strategic Posture Commission.

Nuclear Signaling

In recent years, the United States sought to use its nuclear arsenal to signal both its resolve and capability to adversary nations—an effort likely to continue and grow in the coming years. Past efforts at nuclear signaling include increased nuclear-armed bomber exercises, updating nuclear strike plans, nuclear submarine visits to foreign ports, and participation in NATO’s annual Steadfast Noon nuclear exercise. In addition, the Biden administration announced that its new nuclear employment guidance determined “it may be necessary to adapt current U.S. force capability, posture, composition, or size,” and directed the Pentagon “to continuously evaluate whether adjustments should be made.” This language effectively leaves it to the incoming Trump administration to decide whether to expand the U.S. arsenal in response to China’s buildup (read a detailed FAS analysis by Adam Mount and Hans Kristensen here).

Modernization and Nuclear Infrastructure

Nuclear modernization continues for all three legs of the nuclear triad. For the ground-based leg, the new ICBM reentry vehicle––the Mk21A––is expected to enter the Engineering and Manufacturing development phase in FY25. It will be integrated into the Sentinel ICBM and carry the new W87-1 warheads currently under development. The Sentinel ICBM program continues to run over-budget as all 450 launch centers must be renovated to accommodate the new missile, and new command and control facilities, launch centers, training sites, and curriculum for USAF personnel must be created. For the sea leg, the first Columbia-class ballistic missile submarine (SSBN)––the USS District of Columbia––passed its 50 percent construction completion metric in August 2024, and the USS Wisconsin passed 14 percent in September. The new SSBNs will include a reactor that, unlike the Ohio class SSBNs, will not require refueling for the entirety of its lifecycle. The program faces delays and is projected to cost five times more than the Navy’s estimates For the air leg, the Air Force is developing a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) known as the AGM-181 LRSO, as well as the B-21 Raider and new gravity bombs, including the B61-12 and B61-13.

Throughout 2024, infrastructure upgrades at various U.S. ICBM bases were visible. This includes a new Weapons Generation Facility at Malmstrom Air Force Base and a Missile-Handling and Storage Facility and Transporter Storage Facility at F.E. Warren Air Force Base, as well as test silos at Vandenberg Space Force Base.

Finally, in addition to these ongoing upgrades, the United States is also considering developing a new non-strategic nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), which was proposed during the first Trump administration. Despite the Biden administration’s attempt to cancel the program, Congress has forced the administration to establish the SLCM-N as a program of record. The SLCM-N was originally expected to use the W80–4 warhead that is being developed for the LRSO; however, this is currently being renegotiated. The warhead and delivery platform are expected to be finalized in early 2025.

The Nuclear Notebook is published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and freely available here.

This latest issue follows the release of the 2024 UK Nuclear Notebook. The next issue will focus on China. Additional analysis of global nuclear forces can be found at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

ABOUT THE NUCLEAR NOTEBOOK

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is an effort by the Nuclear Information Project team published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The joint publication began in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenals and the role of nuclear weapons in national security.

The Federation of American Scientists’ work on nuclear transparency would not be possible without generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Longview Philanthropy, the Jubitz Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More at fas.org

Pursuing A Missile Pre-Launch Notification Agreement with China as a Risk Reduction Measure

While attempts at dialogue and military-to-military communication with China regarding its growing nuclear arsenal have increased, the United States has so far been unable to establish permanent lines of communication on nuclear weapons issues, let alone reach a substantive bilateral arms control agreement with China. Given the simmering tensions between the United States and China, lack of communication can be dangerous. Miscommunication or miscalculation between the two nuclear powers – especially during a crisis – could lead to escalation and increased risk of nuclear weapons use.

In an effort to prevent this, the next U.S. presidential administration should pursue a Missile Pre-Launch Notification Agreement with China. The agreement should include a commitment by each party to notify the other ahead of all strategic ballistic missile launches. Similar agreements currently exist between the United States and Russia and between China and Russia. One between the United States and China would be a significant confidence-building measure for reducing the risk of nuclear weapons use and establishing a foundation for future arms control negotiations.

Challenge and Opportunity

Between states with fragile relations, missile launches may be seen as provocative. In the absence of proper communication, a surprise missile test launch in the heat of a tense crisis could trigger overreaction and escalate tensions. Early warning systems are made to detect incoming missiles, but experts estimate that the US early-warning system would have just two minutes to determine if the attack is real or serious enough to advise the president on a possible nuclear counterattack. For example, when the Soviet Union test-launched four submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) in 1980, the US early warning system projected that one of the missiles appeared to be headed toward the United States, resulting in an emergency threat assessment conference of US officials.

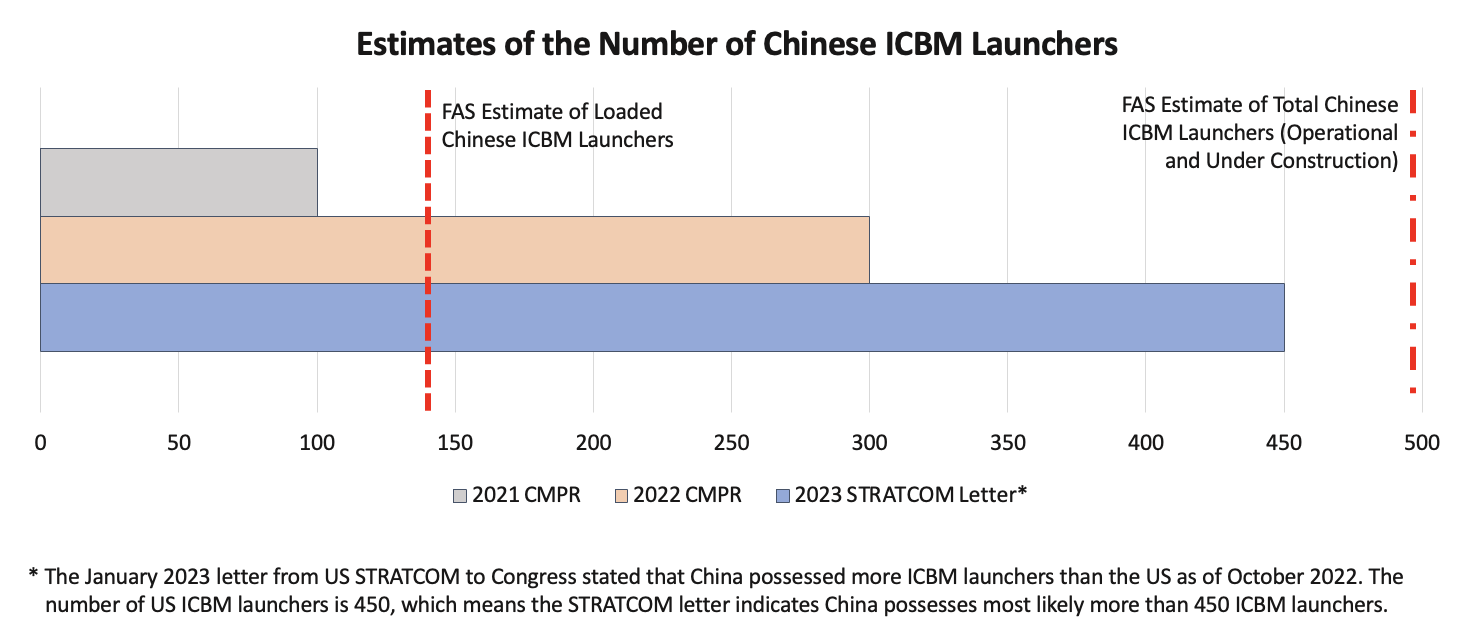

Establishing regular communications is increasingly important as China grows its nuclear arsenal of quick-launching ballistic missiles, with the Pentagon estimating that China’s arsenal may reach 1,000 warheads by 2030. This is creating increasing concern about China’s intentions for how it might use nuclear weapons. In reaction, some US officials are signaling that it may be necessary for the United States to field new nuclear weapons systems or increase the number of deployed warheads. Defense hawks even advocate curtailing diplomatic communication with China, arguing that talks would allow China leverage and insight into US nuclear thinking.

With tensions and aggressive rhetoric on the rise, the next administration needs to prioritize and reaffirm the necessity of regular communication with China on military and nuclear weapons issues to reduce the risk of misunderstandings and conflict and mitigate the chance of accidental escalation and miscalculation.

The opportunity for negotiating an agreement with China exists despite heightened tensions. Although still inadequate, military-to-military communications between China and the United States have improved since a breakdown in 2022 following Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan, to which China responded with military exercises, missile tests, and sanctions on the island.

On November 6, 2023, Chinese Director-General of the Department of Arms Control Sun Xiaobo and US Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability Mallory Stewart discussed nonproliferation and nuclear transparency during the first US-China arms control talk in five years. Days later, Presidents Biden and Xi decided to resume military-to-military conversations and encouraged a follow-up arms control talk. A high-level China-US defense policy talk at the Pentagon in early January 2024 followed this summit. Most recently, Presidents Biden and Xi agreed in Lima, Peru that humans, not artificial intelligence, should have control over the decision to launch nuclear weapons. These meetings show promising signs of improved dialogue, but the United States’ continual emphasis on China as a competitor and China’s recent cancelation of arms control talks with the United States over Taiwan continue to undermine progress.

Policy Models

A Missile Pre-Launch Notification Agreement between China and the United States should include a commitment to provide at least 24 hours of advanced notice of all strategic ballistic missile tests including the planned launch and impact locations. The agreement would build on historical models of risk reduction measures between other states. For example, at the 1988 Moscow Summit, the United States and the Soviet Union signed the Agreement on Notifications of Launches of Ballistic Missiles to notify each other of the planned date, launch area, and area of impact no less than 24 hours in advance of any intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) or submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) launches. These notifications were communicated through established Nuclear Risk Reduction Centers. The Strategic Arms Reduction Talks (START), signed in 1991, followed up on the notification agreement by including an agreement to provide more information, such as telemetry broadcast frequencies, in addition to the planned launch date and the launch and reentry area.

The two countries expanded on this agreement through the Memorandum of Agreement on the Establishment of a Joint Center for the Exchange of Data from Early Warning Systems and Notifications of Missile Launches (also known as JDEC MOA) and the Memorandum of Understanding on Notifications of Missile Launches (PLNS MOU). The purpose of these agreements, signed in 2000, was to prevent a nuclear attack based on a false early warning system notification, and the agreements were carried forward into the New START treaty that entered into force in 2011.

While Russia has suspended its participation in the New START treaty and increased its threatening rhetoric around the potential use of nuclear weapons in its war in Ukraine, the Russian Foreign Ministry said that Russia would continue to provide notification of ballistic missile launches to the United States. This demonstrates the value of communication amid tensions and conventional conflict to prevent misunderstanding.

In 2009, Russia and China signed a pre-launch notification agreement, marking China’s first bilateral arms control agreement. This agreement was extended in 2020 for another 10 years and covers launches of ballistic missiles with ranges over 2,000 km that are in the direction of the other country. The United States and China have no such arrangement. However, China did notify the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and the Japanese Coast Guard 24 hours before an ICBM launch into the Pacific Ocean on September 25, 2024. This launch appeared to be the first test into the Pacific China has conducted in over thirty years, and the gesture of notifying the United States beforehand was, according to a Pentagon spokesperson, “a step in the right direction to reducing the risks of misperception and miscalculation.” With this notification, the groundwork and precedent for dialogue on a missile pre-launch notification agreement has been laid.

Plan of Action

Create and present a draft agreement

The next administration should direct the State Department Bureau of Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability to draft a proposal for a missile pre-launch notification agreement requiring mutual pre-launch notifications for missile launches with ranges of 2,000 km or more, as well as the sharing of launch and impact locations.

The US Assistant Secretary of State for Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability should present the draft proposal to China’s Director-General of the Department of Arms Control of the Foreign Ministry.

Invite President Xi Jinping to participate in talks

The administration should propose a neutral site in the Asian-Pacific region, possibly in Hanoi, Vietnam, for a meeting between the US president and President Xi Jinping to emphasize the shared goal of trade security and discuss a missile test launch agreement. The meeting should include other high-level military commanders, including the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Secretary of Defense, as well as their relevant Chinese counterparts.

Continue notifying China of all US missile test launches

The next administration should continue the precedent set by China in September 2024 to voluntarily provide advance notification of all ballistic missile test launches even in the absence of a negotiated agreement, like was done in the November 2024 Minuteman launch, and even if done unilaterally going forward. Such action would improve the prospect for reaching a negotiated agreement by demonstrating good faith and commitment to conflict mitigation.

Raise the topic of missile launch notifications in P5 meetings

China has since assumed the rotating position of Chair of the P5, which could be a useful forum for considering new proposals for risk reduction measures among all nuclear states. After direct engagement with China on an agreement, China may have an interest in working with the United States to lead a multilateral agreement, as China would have more control over the language, international recognition for nuclear risk reduction, and improved security amid global nuclear modernization.

The next administration should direct The Special Representative of the President for Nuclear Nonproliferation under the Bureau of International Security and Nonproliferation to raise the topic of missile launch notifications and a potential launch notification agreement during the P5 process meeting ahead of the 2025 Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT) preparatory conference.

In order to work constructively with China on reducing the risk of nuclear use, a pre-launch notification agreement should, for now, be decoupled from any other arms control measures that would propose limiting China’s nuclear weapons stockpile or any launch capabilities. While comprehensive arms control may be an ultimate goal, linking the two at the outset would complicate talks significantly and likely prevent an agreement from coming to fruition; the United States should start with small steps to foster trust between the two nations and deepen regular military-to-military communication.

Pursuing and negotiating a Missile Pre-Launch Notification Agreement with China will emphasize common objectives and help prevent escalation by miscommunication.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

United States Discloses Nuclear Warhead Numbers; Restores Nuclear Transparency

Note: The initial NNSA release showed an incorrect graph that did not accurately depict the size of the stockpile for the period 2012-2023. The corrected graph is shown above.

[UPDATED VERSION] The Federation of American Scientists applauds the United States for declassifying the number of nuclear warheads in its military stockpile and the number of retired and dismantled warheads. The decision is consistent with America’s stated commitment to nuclear transparency, and FAS calls on all other nuclear states to follow this important precedent.

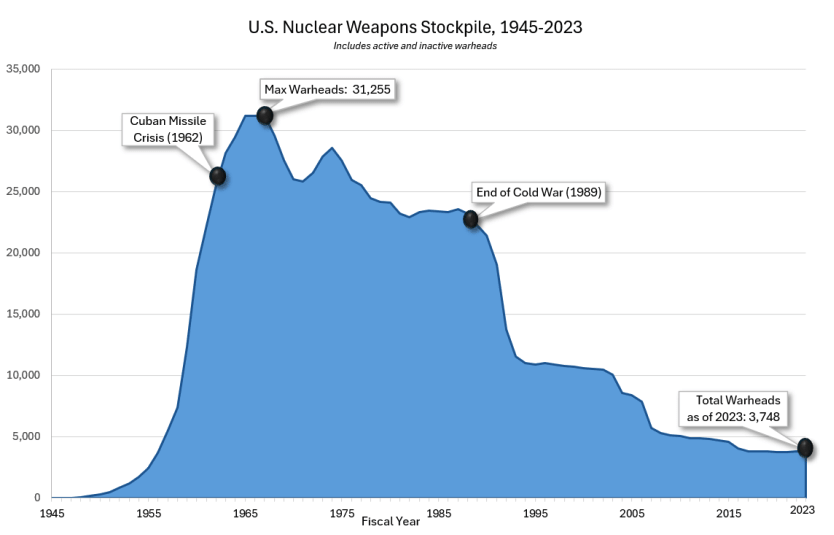

The information published on the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) web site today shows that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile as of September 2023 included 3,748 nuclear warheads, only 40 warheads off FAS’ estimate of 3,708 warheads.

The information also shows that the United States last year dismantled only 69 retired nuclear warheads, the lowest number since 1994.

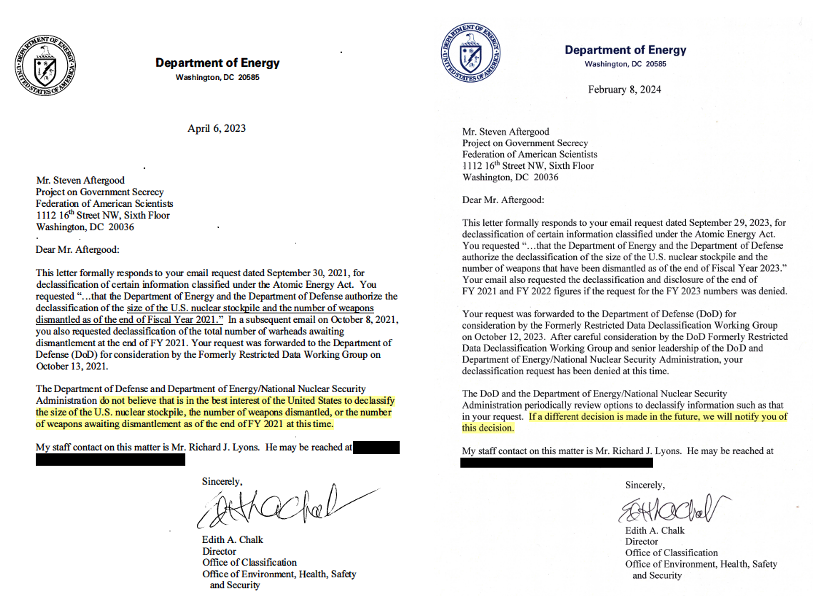

FAS has previously requested that the United States release the size of the US nuclear arsenal for FY2021, FY2022, and FY2023, but those requests were denied. FAS believes the information was wrongly withheld and that today’s declassification decision vindicates our belief that stockpile disclosures do not negatively affect U.S. security but should be provided to the public.

With today’s announcement, the Biden Administration has restored the nuclear stockpile transparency that was created by the Obama administration, halted by the Trump administration, revived by Biden administration in its first year, but then halted again for the past three years.

While applauding the U.S. disclosure, FAS also urged other nuclear-armed states to disclose their stockpile numbers and warheads dismantled. Excessive nuclear secrecy creates mistrust, fuels worst-case planning, and enables hardliners and misinformers to exaggerate nuclear threats.

What The Nuclear Numbers Show

The declassified stockpile numbers show that the United States maintained a total of 3,748 warheads in its military stockpile as of September 2023. The military stockpile includes both active and inactive warheads in the custody of the Department of Defense. The information also discloses weapons numbers for the previous two years, numbers that the U.S. government had previously declined to release.

Although there have minor fluctuations, the numbers show that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has remained relative stable for the past seven years. The fluctuations during that period do not reflect decision to increase or decrease the stockpile but are the result of warheads movements in and out of the stockpile as part of the warhead life-extension and maintenance work.

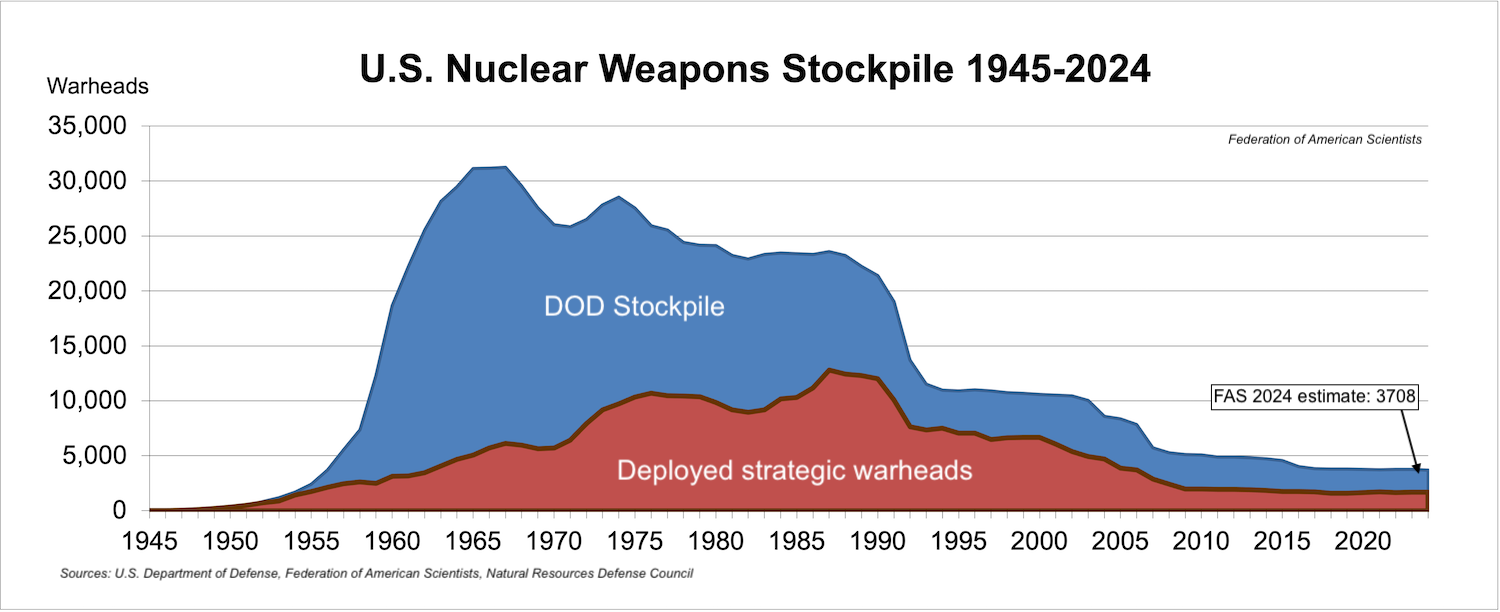

Although the warhead numbers today are much lower than during the Cold War and there have been reductions since 2000, the reduction since 2007 has been relatively modest. Although the New Start treaty has had some indirect effect on the stockpile size due to reduced requirement, the biggest reductions since 2007 have be caused by changes in presidential guidance, strategy, and modernization programs. The initial chart released by NNSA did not accurately show the 1,133-warhead drop during the period 2012-2023. NNSA later corrected the chart (see top of article). The chart below shows the number of warheads in the stockpile compared with the number of warheads deployed on strategic launchers over the years.

This graph shows the size of the U.S. nuclear stockpile over the years plus the portion of those warheads deployed on strategic launchers. The stockpile number for 2024 and the strategic launcher warheads are FAS estimates.

The information also shows that the United States last year dismantled only 69 retired nuclear warheads. That is the lowest number of warheads dismantled in a year since 1994. The total number of retired nuclear warheads dismantled 1994-2023 is 12,088. Retired warheads awaiting dismantlement are not in the DOD stockpile but in the DOE stockpile.

The information disclosed also reveals that there are currently another approximately 2,000 retired warheads in storage awaiting dismantlement. This number is higher than our most recent estimate (1,336) because of the surprisingly low number of warheads dismantled in recent years. Because dismantlement appears to be a lower priority, the number of retired weapons awaiting dismantlement today (~2,000) is only 500 weapons lower than the inventory was in 2015 (~2,500).

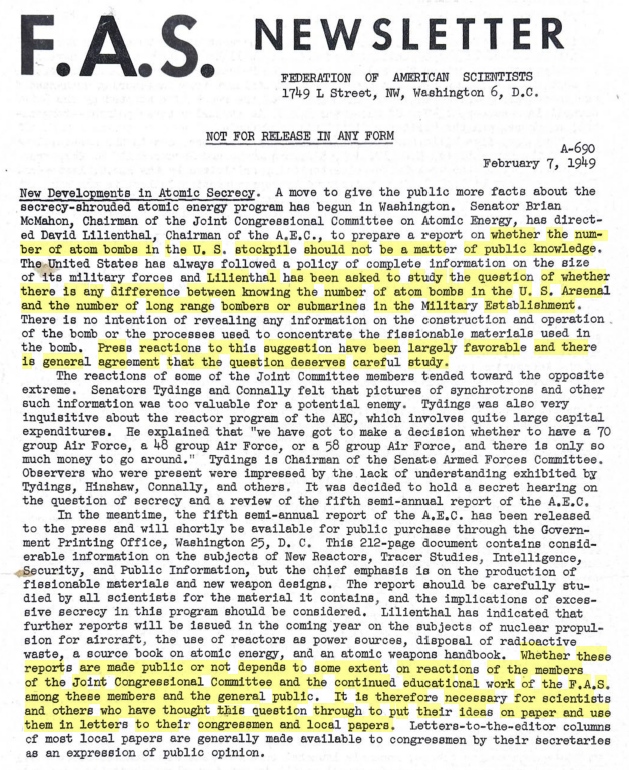

FAS’ Work For Nuclear Transparency

The Federation of American Scientists has worked since its creation to increase responsible transparency on nuclear weapons issues; in fact, the nuclear scientists that built the bomb created the “Federation of Atomic Scientists” to enable some degree of transparency to discuss the implications of nuclear weapons (see FAS newsletter from 1949). There are of course legitimate nuclear secrets that must remain so, but nuclear stockpile numbers are not among them.

This FAS newsletter from 1949 describes the debate and FAS effort in support of transparency of the US weapons stockpile.

One part of FAS’ efforts, spearheaded by Steve Aftergood who for many years directed the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, has been to report on the government’s discussions about what needs to be classified and repeatedly request declassification of unnecessary secrets such as the stockpile numbers. This work yielded stockpile declassifications in some years (2012-2018, 2021) while in other years (2019-2020 and 2022-2024) FAS’ declassified requests were initially denied. Most recently, in February 2024, an FAS declassification request for the stockpile numbers as of 2023 was denied, although the letter added: “If a different decision is made in the future, we will notify you of this decision” (see rejection letters). Given these denials, FAS in March 2024 sent a letter to President Biden outlining the important reasons for declassifying the numbers.

The new disclosure of the stockpile numbers suggests that denial of earlier FAS declassification requests in 2023 and 2024 may not have been justified and that future years’ numbers should not be classified.

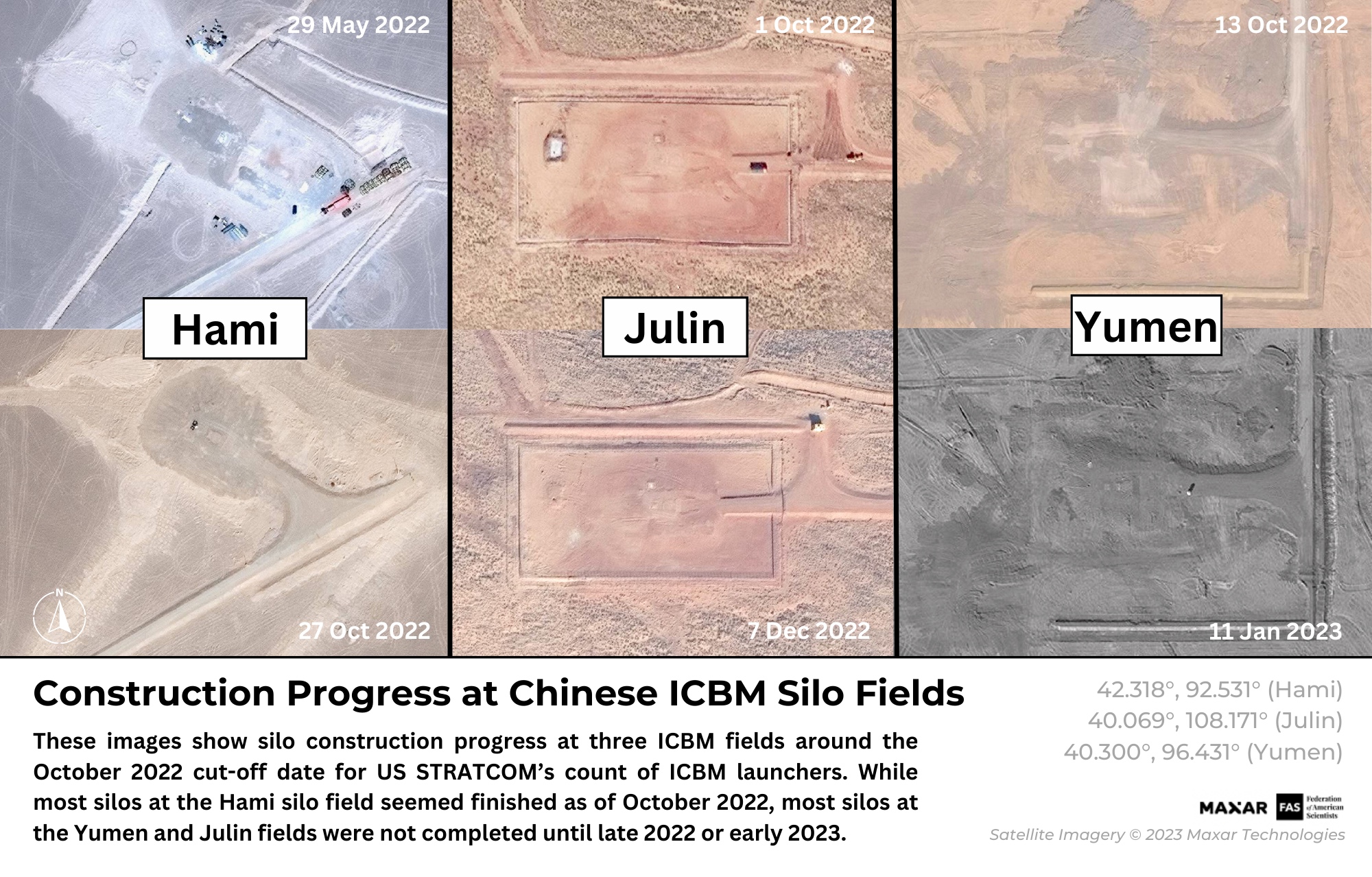

The other part of FAS’ efforts has been the Nuclear Information Project, which works to analyze, estimate, and publish information about the U.S. nuclear arsenal. In 2011, when the Obama administration first declassified the history of the stockpile, the FAS estimate was only 13 warheads off from the official number of 5,112 warheads. The Project also works to increase transparency of the other nuclear-armed states by providing the public with estimates of their nuclear arsenals. The project described the structures that enabled Matt Korda on our team and others to discover the large missile silo fields China was building, and NATO officials say our data is “the best for open source information that doesn’t come from any one nation.”

Why Nuclear Transparency Is Important

FAS has since its founding years worked for maximum responsible disclosure of nuclear weapons information in the interest of international security and democratic values. In a letter to President Biden in March 2024 we outlined those interests.

After denials in 2023 and February 2024 of FAS declassification requests, FAS in March sent President Biden a letter outlining why the denials were wrong. Click here to download full version of letter.

First, responsible transparency of the nuclear arsenal serves U.S. security interests by supporting deterrence and reassurance missions with factual information about U.S. capabilities. Equally important, transparency of stockpile and dismantlement numbers demonstrate that the United States is not secretly building up its arsenal but is dismantling retired warheads instead of keeping them in reserve. This can help limit mistrust and worst-case scenario planning that can fuel arms races.

Second, the United States has for years advocated and promoted nuclear transparency internationally. Part of its criticism of Russia and China is their lack of disclosure of basic information about their nuclear arsenals, such as stockpile numbers. U.S. diplomats have correctly advocated for years about the importance of nuclear transparency, but their efforts are undermined if stockpile and dismantlement numbers are kept secret because it enables other nuclear-armed states to dismiss the United States as hypocritical.

Third, nuclear transparency is important for the debate in the United States (and other Allied democracies) about the status and future of the nuclear arsenal and strategy and how the government is performing. Opponents of declassifying nuclear stockpile numbers tend to misunderstand the issue by claiming that disclosure gives adversaries a military advantage or that the United States should not disclose stockpile numbers unless the adversaries do so as well. But nuclear transparency is not a zero-sum issue but central to the democratic process by enabling informed citizens to monitor, debate, and influence government policies. Although the U.S. disclosure is not dependent on other nuclear-armed states releasing their stockpile numbers, Allied countries such as France and the United Kingdom should follow the U.S. example, as should Russia and China and the other nuclear-armed states.

Acknowledgement: Mackenzie Knight, Jon Wolfsthal, and Matt Korda provided invaluable edits.

More information on the FAS Nuclear Information Project page.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Nuclear Experts from the Federation of American Scientists Contribute to SIPRI Yearbook 2024

FAS’s Nuclear Information Project estimates that the combined global inventory of nuclear warheads is approximately 12,120

Washington, DC – June 17, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists’ nuclear weapons researchers Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda with the Nuclear Information Project write in the new SIPRI Yearbook, released today, that the world’s nuclear arsenals are on the rise, and massive modernization programs are underway.

“China is expanding its nuclear arsenal faster than any other country,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “But in nearly all of the nuclear-armed states, there are either plans or a significant push to increase nuclear forces.”

“We are entering a new period in the post-Cold War era as nuclear stockpiles increase and nuclear transparency decreases. It is, therefore, extremely important for independent researchers to inject factual data into the debate,” says Matt Korda, Associate Researcher in the SIPRI Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Senior Research Fellow at FAS.

Kristensen and Korda are leading researchers on the global stockpile of nuclear weapons. Along with their colleagues Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight, the Nuclear Information Project team at FAS produces the Nuclear Notebook, a bi-monthly report published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists detailing current estimates of nuclear weapon stockpiles. This work plays an increasingly important role as government transparency about nuclear forces continues to decline around the globe. Ongoing reports, archives, and other materials are available at fas.org.

The first edition of the SIPRI Yearbook was released in 1969, with the aim of producing “a factual and balanced account of a controversial subject-the arms race and attempts to stop it.” Interested parties may download excerpts from the latest Yearbook in several languages here, or purchase the report in full.

Read a summary of SIPRI findings by FAS Nuclear Information Project researcher Eliana Johns here.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Construction Of New Nuclear Weapons Facility At Barksdale AFB

Satellite images show that the Navy has begun construction of a new nuclear weapons storage and handling facility at Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana. The construction of this facility is part of a larger effort by the U.S. Air Force to expand the number of strategic bomber bases that can store nuclear weapons.

The Weapons Generation Facility (WGF), once complete, will reinstate the capability to store nuclear weapons at Barksdale AFB, home to the 2nd Bomb Wing with B-52H bombers. The capability was lost approximately 20 years ago when the Air Force decided to consolidate storage of nuclear air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM) to Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota.

Image from US Air Force of inside ALCM maintenance facility at Barksdale AFB in 2013. The insignia on the wall shows a mushroom cloud and slogan reading “We put the FIRE in FIREPOWER.”

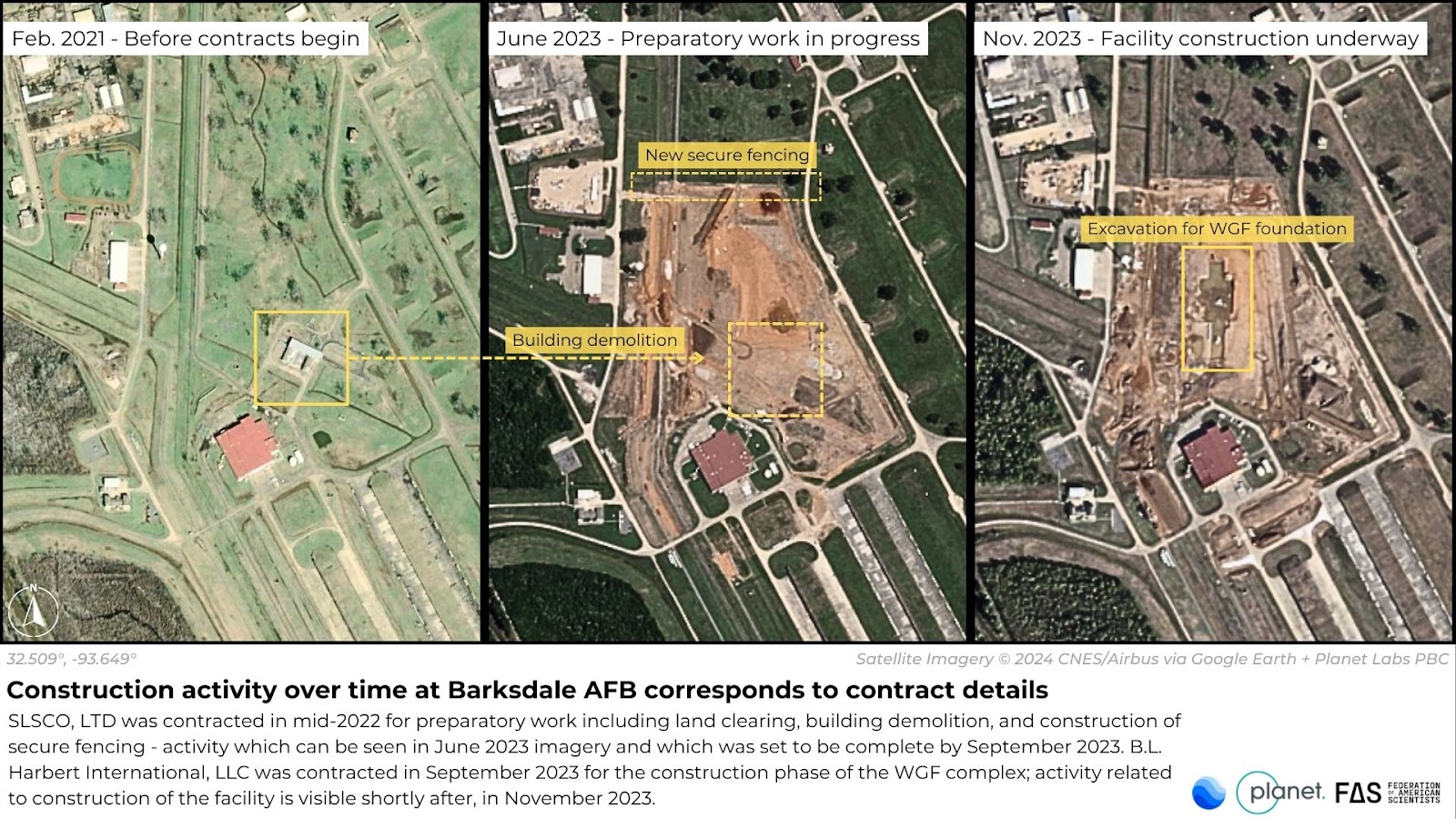

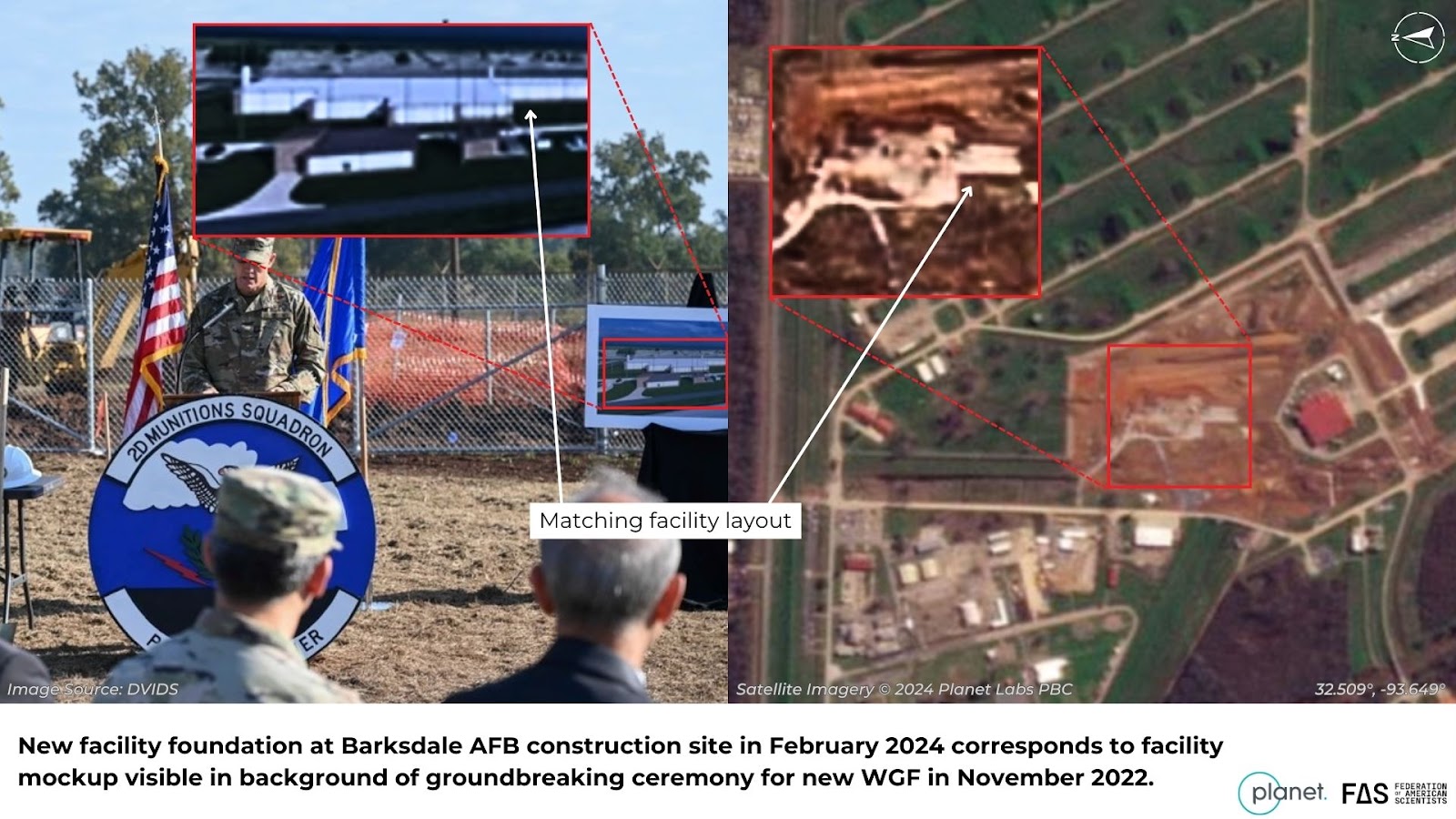

Our assessment that the new construction visible on satellite imagery is of the planned nuclear weapons storage and handling facility is bolstered by several open sources. A draft environmental assessment from 2017 reveals the Air Force’s plans to construct a WGF (at the time referred to as Weapons Storage and Maintenance Facilities [WSF]) at Barksdale AFB, the construction is occurring within the double-fence perimeter that housed Barksdale’s past nuclear weapons storage capability, and the construction area corresponds to the approximate size of the new complex detailed in publicly-available contract documents. Additionally, contract timelines and details correspond to activity at the site (See Figure 1), and the building foundation visible from satellite imagery corresponds to digital mockups of the facility seen in the background of photos from the WGF groundbreaking ceremony shared by DVIDS (See Figure 2).

Construction activity over time at Barksdale AFB corresponds to contract details

SLSCO, LTD was contracted in mid-2022 for preparatory work including land clearing, building demolition, and construction of secure fencing – activity which can be seen in June 2023 imagery and which was set to be complete by September 2023. B.L Harbert International, LLC was contracted in September 2023 for the construction phase of the WGF complex; activity related to construction of the facility is visible shortly after, in November 2023.

New facility foundation at Barksdale AFB construction site in February 2024 corresponds to facility mockup visible in background of groundbreaking ceremony for new WF in November 2022.

Work on the site began in mid-2022 with a $33 million contract to SLSCO, LTD to carry out site preparation via clearing, drainage, building demolition, utilities demolition and relocation, construction of secure fencing, and roadway construction, among other preparatory tasks.

Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC) awarded a $210.2 million fixed-price contract to Alabama company B.L. Harbert International, LLC in September 2023 to construct the 28-acre complex, which will include the main building, an approximately 300,000 square foot WGF; an entry control facility; security facility; fire pump building; diesel generator building; weather shelter; and multiple towers for security.

The facility, expected to be completed by January 2026, will house the new nuclear Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) cruise missiles for delivery by B-52H Stratofortress heavy bombers at the base. With the LRSO expected to achieve initial operational capability in 2030, it is possible that the Barksdale WGF will house the nuclear ALCM until it is replaced by the LRSO. The WGF at Barksdale AFB will only be used to store nuclear cruise missiles, because the B-52H bombers are no longer assigned nuclear gravity bombs.

A B-52H Stratofortress with weapons display at Barksdale AFB, showing 20 (unarmed) nuclear ALCMs on pylons and rotary launcher. Source: United States Air Force

The Weapons Generation Facilities are a new type of facility replacing the Cold War-era Weapons Storage Areas (WSA) in order to consolidate weapons storage, maintenance, and training into one building. Barksdale AFB will become the second base to receive a WGF; construction of the first is well underway at F. E. Warren AFB in Wyoming for ICBM warheads. The Air Force also plans to construct WGFs at Ellsworth AFB in South Dakota, Whiteman AFB in Missouri, and Dyess AFB in Texas for the future B-21 bomber mission.

When completed, the number of U.S. heavy bomber bases with nuclear weapons storage capability will have increased from two today (Minot AFB and Whiteman AFB) to five.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Strategic Posture Commission Report Calls for Broad Nuclear Buildup

On October 12th, the Strategic Posture Commission released its long-awaited report on U.S. nuclear policy and strategic stability. The 12-member Commission was hand-picked by Congress in 2022 to conduct a threat assessment, consider alterations to U.S. force posture, and provide recommendations.

In contrast to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the Congressionally-mandated Strategic Posture Commission report is a full-throated embrace of a U.S. nuclear build-up.

It includes recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase its number of deployed warheads, as well as increasing its production of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warhead production capacity. It also calls for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal.

The only thing that appears to have prevented the Commission from recommending an immediate increase of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile is that the weapons production complex currently does not have the capacity to do so.

The Commission’s embrace of a U.S. nuclear buildup ignores the consequences of a likely arms race with Russia and China (in fact, the Commission doesn’t even consider this or suggest other steps than a buildup to try to address the problem). If the United States responds to the Chinese buildup by increasing its own deployed warheads and launchers, Russia would most likely respond by increasing its deployed warheads and launchers. That would increase the nuclear threat against the United States and its allies. China, who has already decided that it needs more nuclear weapons to stand up to the existing U.S. force level (and those of Russia and India), might well respond to the U.S and Russian increases by increasing its own arsenal even further. That would put the United States back to where it started, feeling insufficient and facing increased nuclear threats.

Framing and context

The Commission’s report is generally framed around the prospect of Russian and Chinese strategic military cooperation against the United States. The Commission cautions against “dismissing the possibility of opportunistic or simultaneous two-peer aggression because it may seem improbable,” and notes that “not addressing it in U.S. strategy and strategic posture, could have the perverse effect of making such aggression more likely.” The Commission does not acknowledge, however, that building up new capabilities to address this highly remote possibility would likely kick the arms race into an even higher gear.

The report acknowledges that Russia and China are in the midst of large-scale modernization programs, and in the case of China, significant increases to its nuclear stockpile. This accords with our own assessments of both countries’ nuclear programs. However, the report’s authors suggest that these changes fundamentally call into question the United States’ assured retaliatory capabilities, and state that “the current U.S. strategic posture will be insufficient to achieve the objectives of U.S. defense strategy in the future….”

The Commission appears to base this conclusion, as well as its nuclear strategy and force structure recommendations, squarely on numerically-focused counterforce thinking: if China increases its posture by fielding more weapons, that automatically means the United States needs more weapons to “[a]ddress the larger number of targets….” However, the survivability of the US ballistic missile submarines should insulate the United States against needing to subscribe to this kind of thinking.

In 2012, a joint DOD/DNI report acknowledged that because of the US submarine force, Russia would not achieve any military advantage against the United States by significantly increasing the size of its deployed nuclear forces. In that 2012 study, both departments concluded that the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” [Emphasis added.] Why would this logic not apply to China as well? Although China’s nuclear arsenal is undoubtedly growing, why would it fundamentally alter the nature of the United States’ assured retaliatory capability while the United States is confident in the survivability of its SSBNs?

In this context, it is worth reiterating the words of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at the U.S. Strategic Command Change of Command Ceremony: “We all understand that nuclear deterrence isn’t just a numbers game. In fact, that sort of thinking can spur a dangerous arms race…deterrence has never been just about the numbers, the weapons, or the platforms.”

Force structure

Although the report says the Commission “avoided making specific force structure recommendations” in order to “leave specific material solution decisions to the Executive Branch and Congress,” the list of “identified capabilities beyond the existing program of record (POR) that will be needed” leaves little doubt about what the Commission believes those force structure decisions should be.

Strategic posture alterations

The Commission concludes that the United States “must act now to pursue additional measures and programs…beyond the planned modernization of strategic delivery vehicles and warheads may include either or both qualitative and quantitative adjustments in the U.S. strategic posture.”

Specifically, the Commission recommends that the United States should pursue the following modifications to its strategic nuclear force posture “with urgency:” [our context and commentary added below]

- Prepare to upload some or all of the nation’s hedge warheads; [these warheads are currently in storage; increasing deployed warheads above 1,550 is prohibited by the New START treaty (which expires in early-2026) and would likely cause Russia to also increase its deployed warheads.]

- Plan to deploy the Sentinel ICBM in a MIRVed configuration; [the Sentinel appears to be capable of carrying two MIRV but current plan calls for each missile to be deployed with just a single warhead]

- Increase the planned number of deployed Long-Range Standoff Weapons; [the Air Force currently has just over 500 ALCMs and plans to build 1,087 LRSOs (including test-flight missiles), each of which costs approximately $13 million]

- Increase the planned number of B-21 bombers and the tankers an expanded force would require; [the Air Force has said that it plans to purchase at least 100 B-21s]

- Increase the planned production of Columbia SSBNs and their Trident ballistic missile systems, and accelerate development and deployment of D5LE2; [the Navy currently plans to build 12 Columbia-class SSBNs and an increase would not happen until after the 12th SSBN is completed in the 2040s]

- Pursue the feasibility of fielding some portion of the future ICBM force in a road mobile configuration; [historically, any efforts to deploy road-mobile ICBMs in the United States have been unsuccessful]

- Accelerate efforts to develop advanced countermeasures to adversary IAMD; and

- Initiate planning and preparations for a portion of the future bomber fleet to be on continuous alert status, in time for the B-21 Full Operational Capability (FOC) date.” [Bombers currently regularly practice loading nuclear weapons as part of rapid-takeoff exercises. Returning bombers to alert would revert the decision by President H.W. Bush in 1991 to take bombers off alert. In 2021, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration stated that keeping the bomber fleet on continuous alert would exhaust the force and could not be done indefinitely]

Nonstrategic posture alterations

The Commission appears to want the United States to bolster its non-strategic nuclear forces in Europe, and begin to deploy non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific theater: “Additional U.S. theater nuclear capabilities will be necessary in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific regions to deter adversary nuclear use and offset local conventional superiority. These additional theater capabilities will need to be deployable, survivable, and variable in their available yield options.” Although the Commission does not explicitly recommend fielding either ground-launched theater nuclear capabilities or a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile for the Navy, it seems clear that these capabilities would be part of the Commission’s logic.

The United States used to deploy large numbers of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific region during the Cold War, but those weapons were withdrawn in the early 1990s and later dismantled as U.S. military planning shifted to rely more on advanced conventional weapons for limited theater options. Despite the removal of certain types of theater nuclear weapons after the Cold War, today the President maintains a wide range of nuclear response options designed to deter Russian and Chinese limited nuclear use in both regions––including capabilities with low or variable yields. In addition to ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-capable bombers operating in both regions, the U.S. Air Force has non-strategic B61 nuclear bombs for dual-capable aircraft that are intended for operations in both regions if it becomes necessary. The Navy now also has a low-yield warhead on its SSBNs––the W76-2––that was fielded specifically to provide the President with more options to deter limited scenarios in those regions. It is unclear why these existing options, as well as several additional capabilities already under development––including the incoming Long-Range Stand-Off Weapon––would be insufficient for maintaining regional deterrence.

The Commission specifically recommends that the United States should “urgently” modify its nuclear posture to “[p]rovide the President a range of militarily effective nuclear response options to deter or counter Russian or Chinese limited nuclear use in theater.” Although current plans already provide the President with such options, the Commission “recommends the following U.S. theater nuclear force posture modifications:

Develop and deploy theater nuclear delivery systems that have some or all of the following attributes: [our context and commentary added below]

- Forward-deployed or deployable in the European and Asia-Pacific theaters [The United States already has dual-capable fighters and B61 bombs earmarked for operations in the Asia-Pacific theaters, backed up by bombers with long-range cruise missiles];

- Survivable against preemptive attack without force generation day-to-day;

- A range of explosive yield options, including low yield [US nuclear forces earmarked for regional options already have a wide range of low-yield options];

- Capable of penetrating advanced IAMD with high confidence [F-35A dual-capable aircraft, the B-21 bomber, and air-launched cruise missiles are already being developed with enhanced penetration capabilities]; and

- Operationally relevant weapon delivery timeline (promptness) [the US recently fielded the W76-2 warhead on SSBNs to provide prompt theater capability in limited scenarios and is developing new prompt conventional missiles].”

Unlike U.S. low-yield theater nuclear weapons, the Commission warns that China’s development of “theater-range low-yield weapons may reduce China’s threshold for using nuclear weapons.” Presumably, the same would be true for the United States threshold if it followed the Commission’s recommendation to increase deployed (or deployable) non-strategic nuclear weapons with low-yield capabilities in the Indo-Pacific theater.

Strategy

Overall, the Commission suggests that current U.S. nuclear strategy is basically sound, but just needs to be backed up with additional weapons and industrial capacity. However, by not including recommendations to modify presidential nuclear employment guidance –– or even considering such an adjustment, which could reshape U.S. force posture to allow for decreased emphasis on counterforce targeting –– the Commission has limited its own flexibility to recommend any options other than simply adding more weapons.

Three scholars recently proposed a revised nuclear strategy that they concluded would reduce weapons requirements yet still be sufficient to adequately deter Russia and China. The central premise of reducing the counterforce focus is similar to a study that we published in 2009. In contrast, the Commission appears to have assumed an unchanged nuclear strategy and instead focused intensely on weapons and numbers.

The Commission report does not explain how it gets to the specific nuclear arms additions it says are needed. It only provides generic descriptions of nuclear strategy and lists of Chinese and Russian increases. The reason this translates into a recommendation to increase the US nuclear arsenal appears to be that the list of target categories that the Commission believes need to be targeted is very broad: “this means holding at risk key elements of their leadership, the security structure maintaining the leadership in power, their nuclear and conventional forces, and their war supporting industry.”

This numerical focus also ignores years of adjustments made to nuclear planning intended to avoid excessive nuclear force levels and increase flexibility. When asked in 2017 whether the US needed new nuclear capabilities for limited scenarios, then STRATCOM commander General John Hyten responded:

“[W]e actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, …I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the President on to give him options on what he would want to do… So I’m very comfortable today with the flexibility of our response options… And the reason I was surprised when I got to STRATCOM about the flexibility, is because the last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive, and that’s all there. We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing.”

While advocating integrated deterrence and a “whole of government” approach, the Commission nonetheless sets up an artificial dichotomy between conventional and nuclear capabilities: “The objectives of U.S. strategy must include effective deterrence and defeat of simultaneous Russian and Chinese aggression in Europe and Asia using conventional forces. If the United States and its Allies and partners do not field sufficient conventional forces to achieve this objective, U.S. strategy would need to be altered to increase reliance on nuclear weapons to deter or counter opportunistic or collaborative aggression in the other theater.”

Arms control

The Commission recommends subjugating nuclear arms control to the nuclear build-up: “The Commission recommends that a strategy to address the two-nuclear-peer threat environment be a prerequisite for developing U.S. nuclear arms control limits for the 2027-2035 timeframe. The Commission recommends that once a strategy and its related force requirements are established, the U.S. government determine whether and how nuclear arms control limits continue to enhance U.S. security.”

Put another way, this constitutes a recommendation to participate in an arms race, and then figure out how to control those same arms later.

The Commission report does acknowledge the importance of arms control, and notes that “[t]he ideal scenario for the United States would be a trilateral agreement that could effectively verify and limit all Russian, Chinese, and U.S. nuclear warheads and delivery systems, while retaining sufficient U.S. nuclear forces to meet security objectives and hedge against potential violations of the agreement.” (p.85) However, the prospect of this “ideal scenario” coming true would become increasingly unlikely if the United States significantly built up its nuclear forces as the Commission recommends.

Capacity and budget

The Commission recommends an overhaul and expansion of the nuclear weapons design and production capacity. That includes full funding of all NNSA recapitalization efforts, including pit production plans, even though the Government Accountability Office has warned that the program faces serious challenges and budget uncertainties. The Commission appears to brush aside concerns about the proposed pit production program.

Overall, the report does not seem to acknowledge any limits to defense spending. Amid all of the Commission’s recommendations to increase the number of strategic and tactical nuclear systems, there is almost no mention of cost in the entire report. Fulfilling all of these recommendations would require a significant amount of money, and that money would have to come from somewhere.

For example, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that developing the SLCM-N alone would cost an estimated $10 billion until 2030, not to mention another $7 billion for other tactical nuclear weapons and delivery systems. The amount of money it would take to field new systems, in addition to addressing other vital concerns such as IAMD, means funding would necessarily be cut from other budget priorities.

The true costs of these systems are not only the significant funds spent to acquire them, but also the fact that prioritizing these systems necessarily means deprioritizing other domestic or foreign policy initiatives that could do more to increase US security.

Implications for U.S. Nuclear Posture

The Strategic Posture Commission report is, in effect, a congressionally-mandated rebuttal to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, which many in Congress have critiqued for not being hawkish enough. The report does not describe in detail its methodology for how it arrives at its force buildup recommendations, and includes several claims and assumptions about nuclear strategy that have been critiqued and called into question by recent scholarship. In some respects, it reads more like an industry report than a Congressionally-mandated study.

While the timing of the report means that it is unlikely to have a significant impact on this year’s budget cycle, it will certainly play a critical role in justifying increases to the nuclear budget for years to come.

From our perspective, the recommendations included in the Commission report are likely to exacerbate the arms race, further constrict the window for engaging with Russia and China on arms control, and redirect funding away from more proximate priorities. At the very least, before embarking on this overambitious wish list the United States must address any outstanding recommendations from the Government Accountability Office to fix its planning and budgeting processes, otherwise it risks overloading the assembly line even more.

In addition, the United States could consider how modified presidential employment guidance might enable a posture that relies on fewer nuclear weapons, and adjust accordingly.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

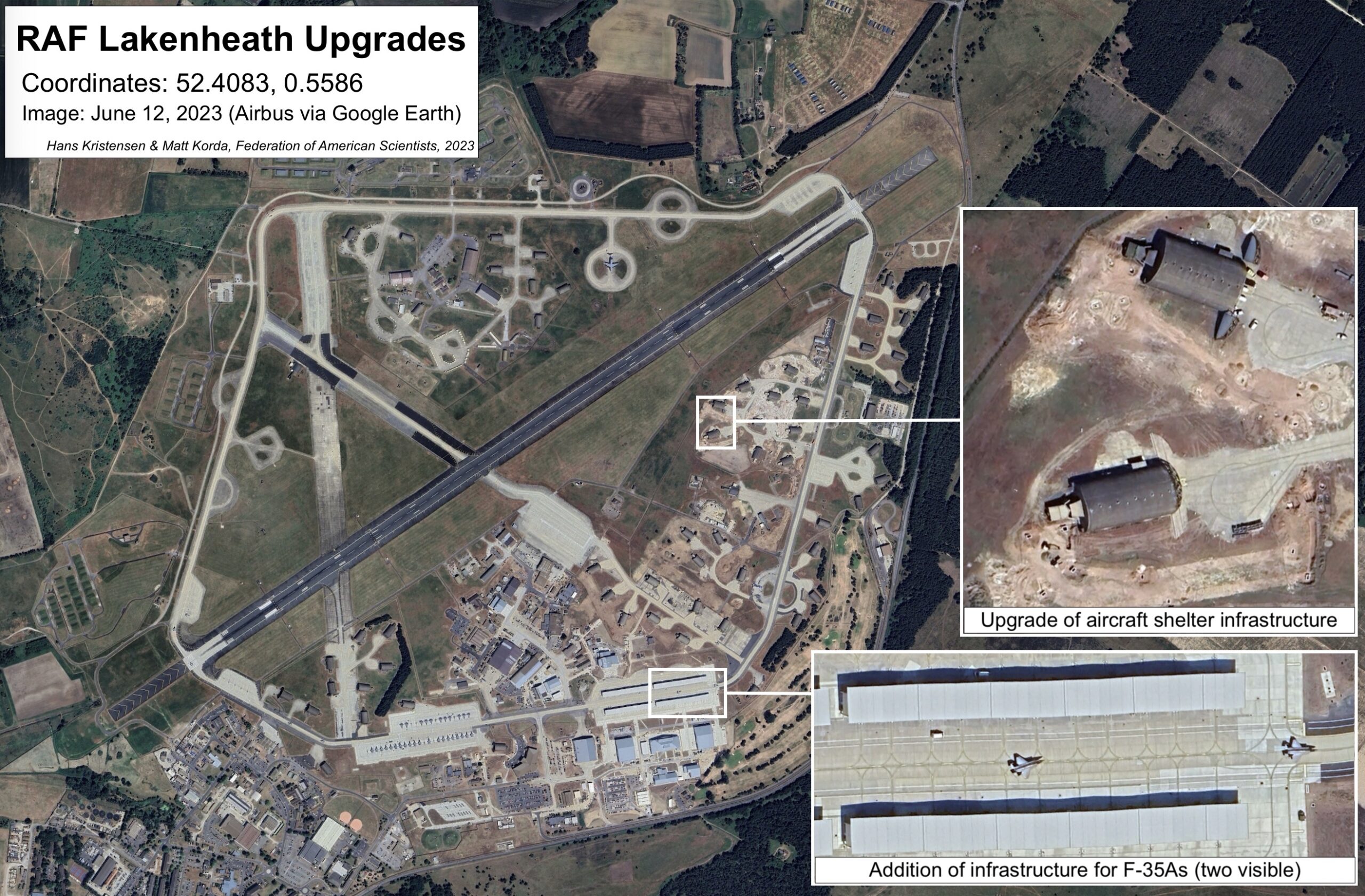

Increasing Evidence that the US Air Force’s Nuclear Mission May Be Returning to UK Soil

Significant modernization is underway at RAF Lakenheath for F-35A aircraft, a planned “surety dormitory,” and other infrastructure indicating that the nuclear weapons mission may be returning after a hiatus of 15 years.

New U.S. Air Force budgetary documents strongly imply that the United States Air Force is in the process of re-establishing its nuclear weapons mission on UK soil.

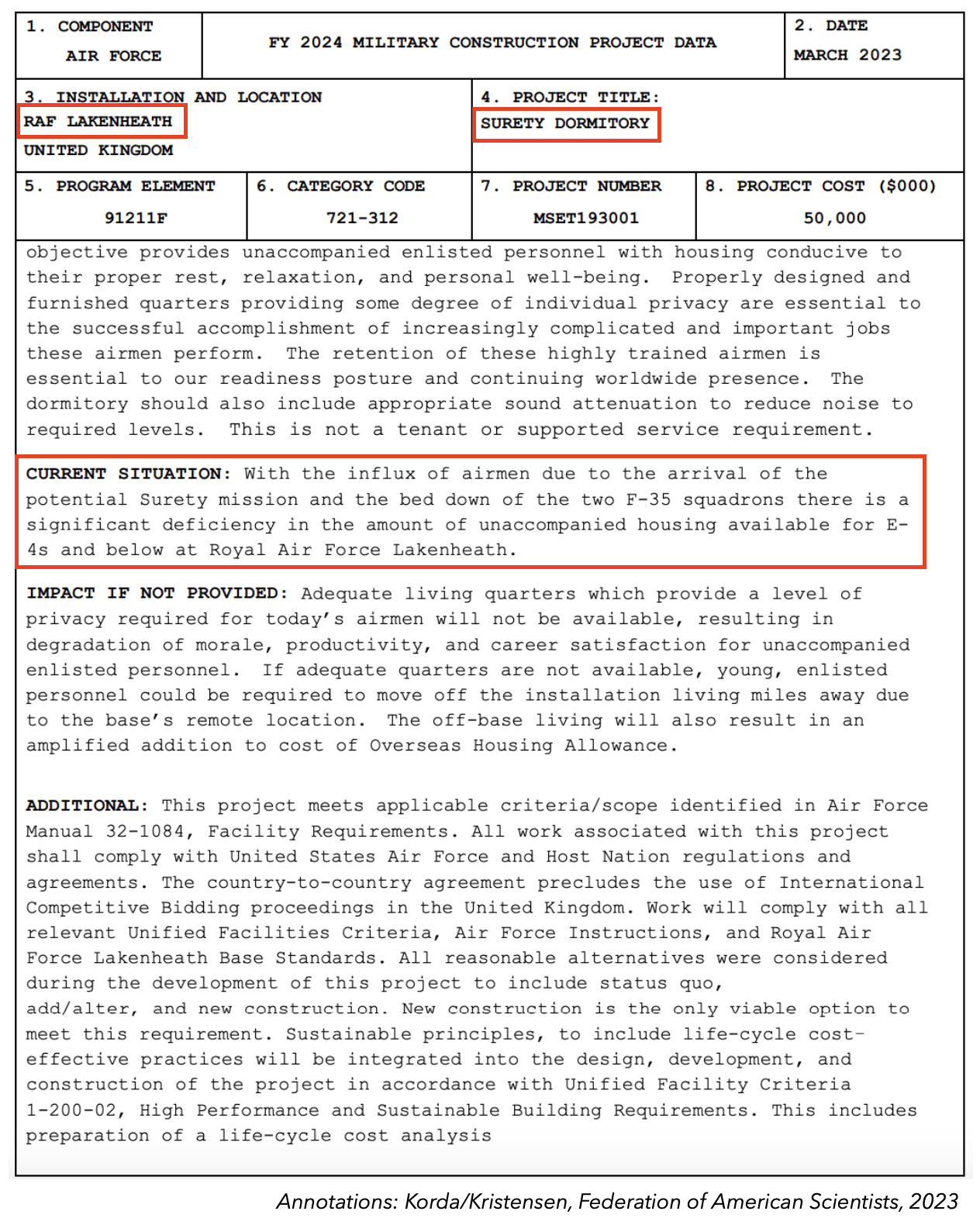

The Air Force’s FY 2024 budgetary justification package, dated March 2023, notes the planned construction of a “surety dormitory” at RAF Lakenheath, approximately 100 kilometers northeast of London. The “surety dormitory” was also briefly mentioned in the Department of Defense’s testimony to Congress in March 2023, but with no accompanying explanation. “Surety” is a term commonly used within the Department of Defense and Department of Energy to refer to the capability to keep nuclear weapons safe, secure, and under positive control.

The justification documents note the new requirement to “Construct a 144-bed dormitory to house the increase in enlisted personnel as the result of the potential Surety Mission” [emphasis added]. To justify the new construction, the documents note, “With the influx of airmen due to the arrival of the potential Surety mission and the bed down of the two F-35 squadrons there is a significant deficiency in the amount of unaccompanied housing available for E4s and below at Royal Air Force Lakenheath” [emphasis added].

The U.S. Air Force’s FY 2024 budgetary justification package describes the proposed construction of a “surety dormitory” at RAF Lakenheath.

Construction of the facility is scheduled to begin in June 2024 and end in February 2026.

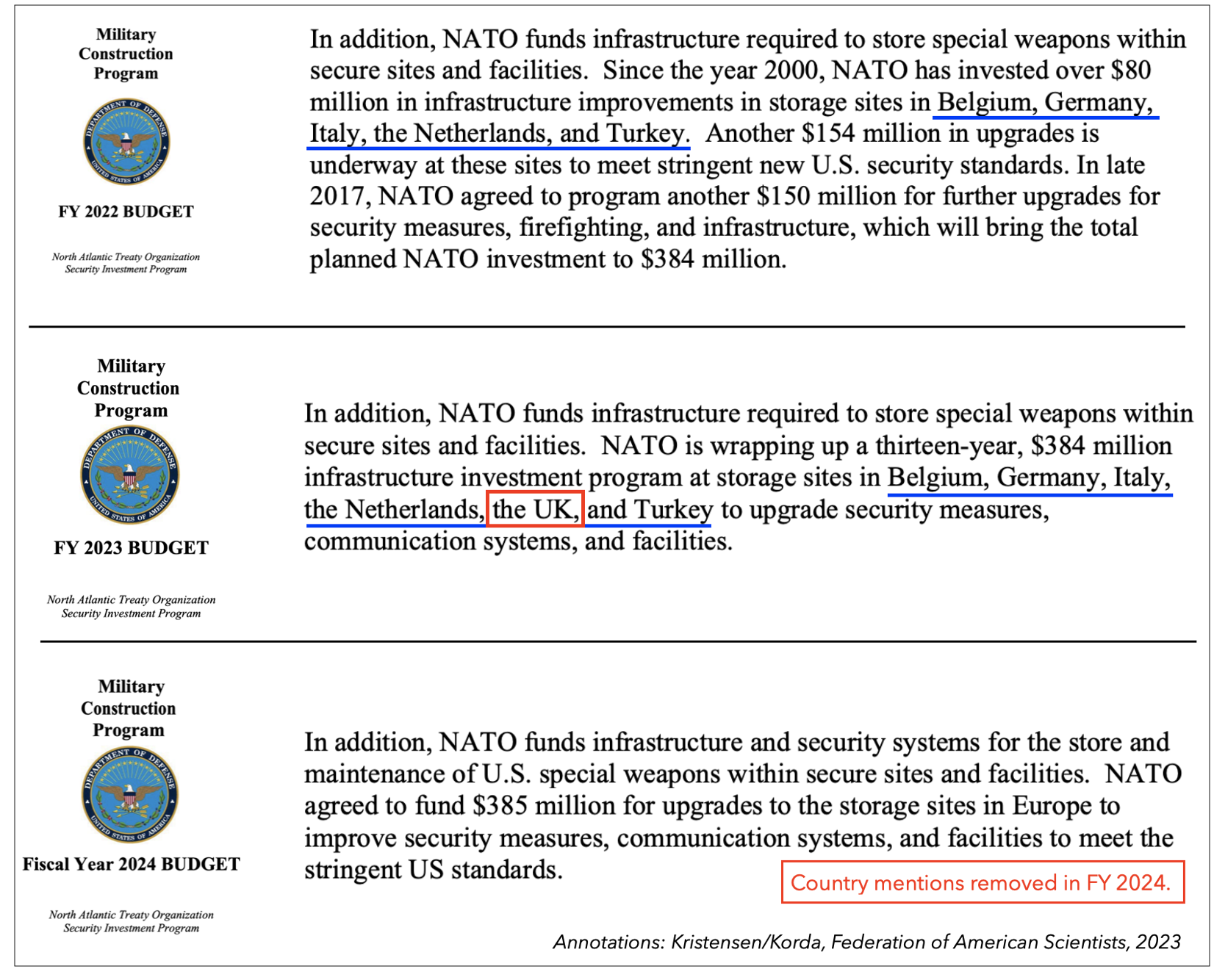

We previously documented the UK’s addition to the Department of Defense’s FY2023 budgetary documentation for the NATO Security Investment Program, in which it was written that “NATO is wrapping up a thirteen-year, $384 million infrastructure investment program at storage sites in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, and Turkey to upgrade security measures, communication systems, and facilities” [emphasis added]. An explicit mention of the UK had not been included in the previous year’s budgetary documents, and it was removed in this year’s documents after we reported on its inclusion the previous year.

The removal of country names from the Pentagon’s latest list of nuclear base upgrades is yet another example of the United States reducing the nuclear transparency of its own nuclear posture while criticizing nuclear secrecy in other nuclear-armed countries.

The removal of country names from the Pentagon’s Military Construction Program budget request follows the denial of a recent FAS declassification request of previously available nuclear warhead numbers. These decisions contradict and undermine the Biden administration’s appeal for nuclear transparency in other nuclear-armed states.

The past two years of budgetary evidence strongly suggests that the United States is taking steps to re-establish its nuclear mission on UK soil. The United States has not stored nuclear weapons in the United Kingdom for the past 15 years, since we reported in 2008 that nuclear weapons had been withdrawn from RAF Lakenheath.

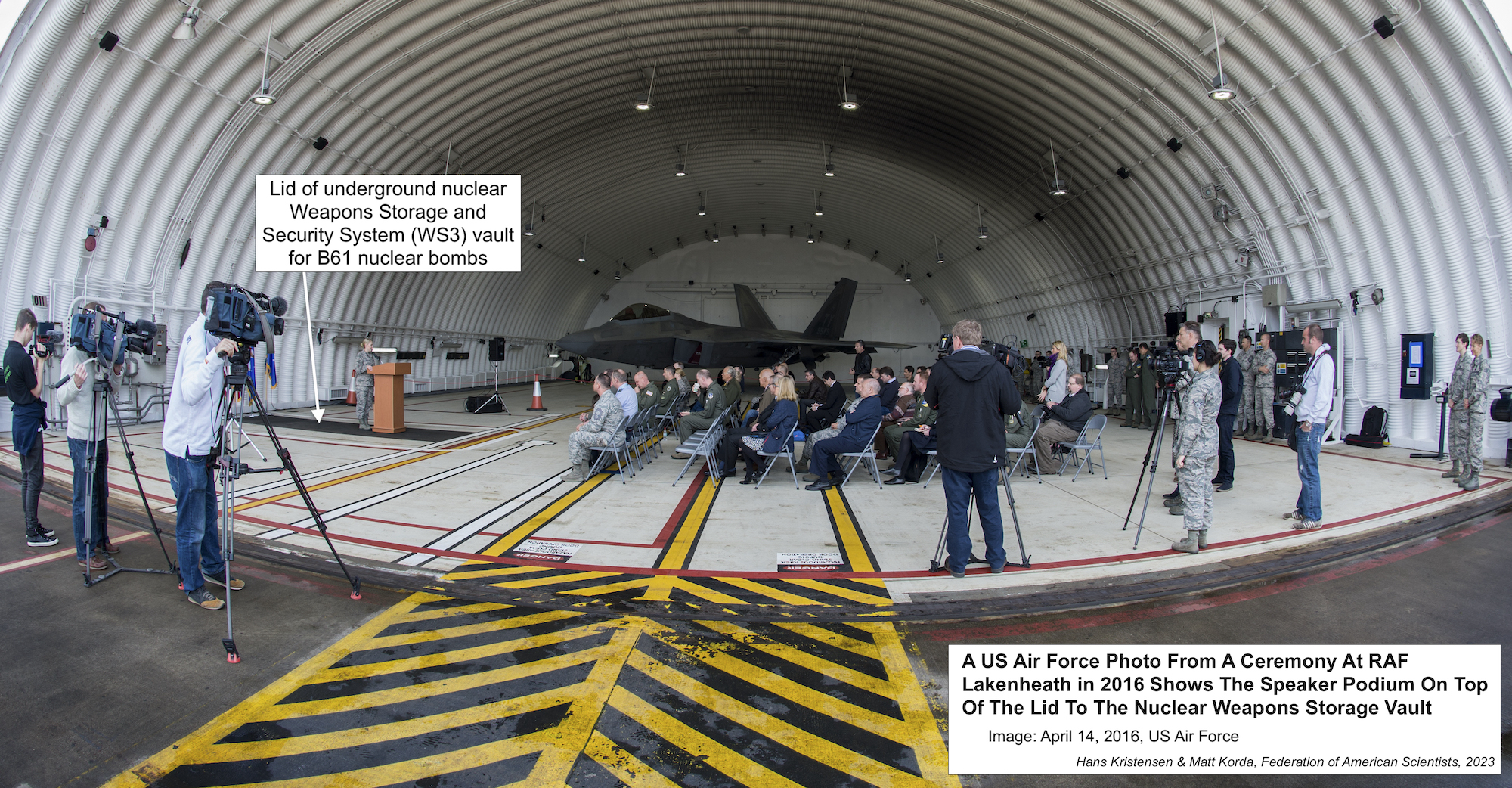

The Weapons Storage and Security Systems (known as WS3) at RAF Lakenheath are contained within Protective Aircraft Shelters; the WS3s include an elevator-drive vault that can be lowered into the concrete floor, as well as the associated command, control, and communications software needed to unlock the weapons. A total of 33 WS3 vaults were installed at RAF Lakenheath in the 1990s, each of which can hold up to four B61 bombs, for a maximum capacity of 132 warheads. Whenever nuclear weapons have been withdrawn from European air bases in the past, their vaults have been put into “caretaker” status, but as Harold Smith, the former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs stated at the time, these vaults were “mothballed in such a way that if we chose to go back into those bases we can do it.”

A total of 33 underground nuclear weapons storage vaults in aircraft shelters at RAF Lakenheath were mothballed, but documents indicate that they may be reactivated soon.

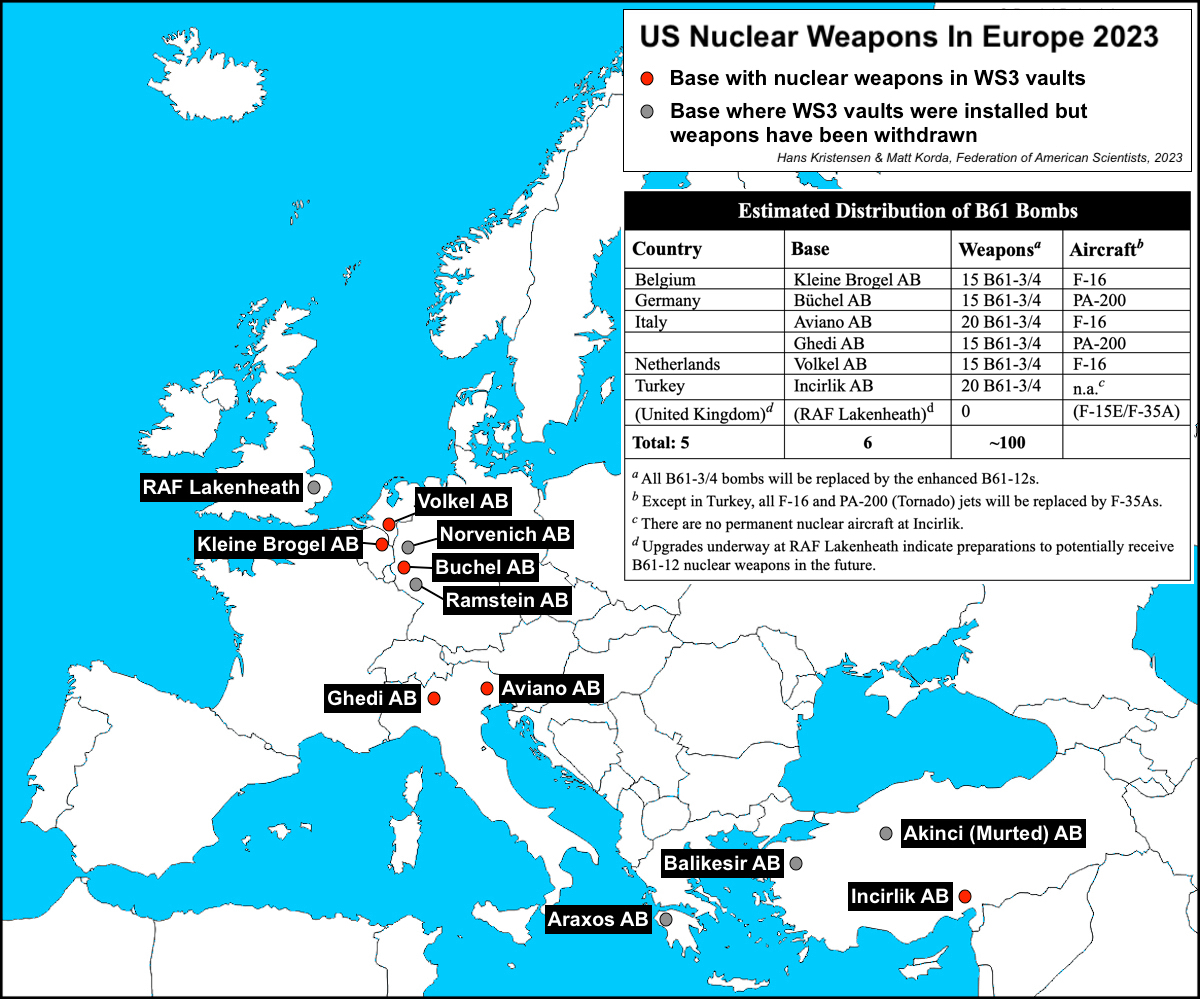

The nuclear-related upgrades to RAF Lakenheath are taking place as the new 495th Fighter Squadron (hosted at RAF Lakenheath) prepares to become the first U.S. Air Force squadron in Europe to be equipped with the nuclear-capable F-35A Lightning II. The upgrades coincide with the long-planned delivery of the new B61-12 gravity bombs to Europe, which will replace the approximately 100 legacy B61-3s and -4s currently estimated to be deployed in Europe.

There are an estimated 100 B61 nuclear bombs deployed at six bases in five European countries, with preparations underway at RAF Lakenheath to potentially receive nuclear weapons as well.

In December 2021, in response to a media question about potentially stationing nuclear weapons in Poland, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg announced that “we have no plans of stationing any nuclear weapons in any other countries than we already have…” However, it is difficult to square his statement with the planned “arrival of the potential Surety mission” at RAF Lakenheath, as well as the addition of the base to the list of sites receiving nuclear upgrades.

One possible explanation is that the United States is currently preparing the infrastructure at RAF Lakenheath to allow the base to potentially receive nuclear weapons in the future or in the midst of a crisis, without necessarily having already decided to permanently station them there or increase the number of weapons currently stored in Europe. The budget language of a “potential Surety mission” indicates that a formal deployment decision has not yet been made.

This would be consistent with construction at other known nuclear storage bases across Europe, where new upgrades are taking place that are designed to facilitate the rapid movement of weapons on- and off-base to increase operational flexibility. In the midst of a genuine nuclear crisis with Russia, for example, a portion of U.S. nuclear weapons could be redistributed from more vulnerable eastern bases to RAF Lakenheath.

Background information:

Lakenheath Air Base Added To Nuclear Weapons Storage Site Upgrades

NATO Steadfast Noon Exercise and Nuclear Modernization in Europe

The C-17A Has Been Cleared To Transport B61-12 Nuclear Bomb To Europe

FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear weapons, 2023

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Was There a U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accident At a Dutch Air Base? [no, it was training, see update below]

Did the U.S. Air Force suffer a nuclear weapons accident at Volkel Air Base?

Did the U.S. Air Force suffer a nuclear weapons accident at an airbase in Europe a few years back? [Update: After USAFE and LANL initially declined to comment on the picture, a Pentagon spokesperson later clarified that the image is not of an actual nuclear weapons accident but of a training exercise, as cautioned in the second paragraph below. The spokesperson declined to comment on the main conclusion of this article, however, that the image appears to be from inside an aircraft shelter at Volkel Air Base.]

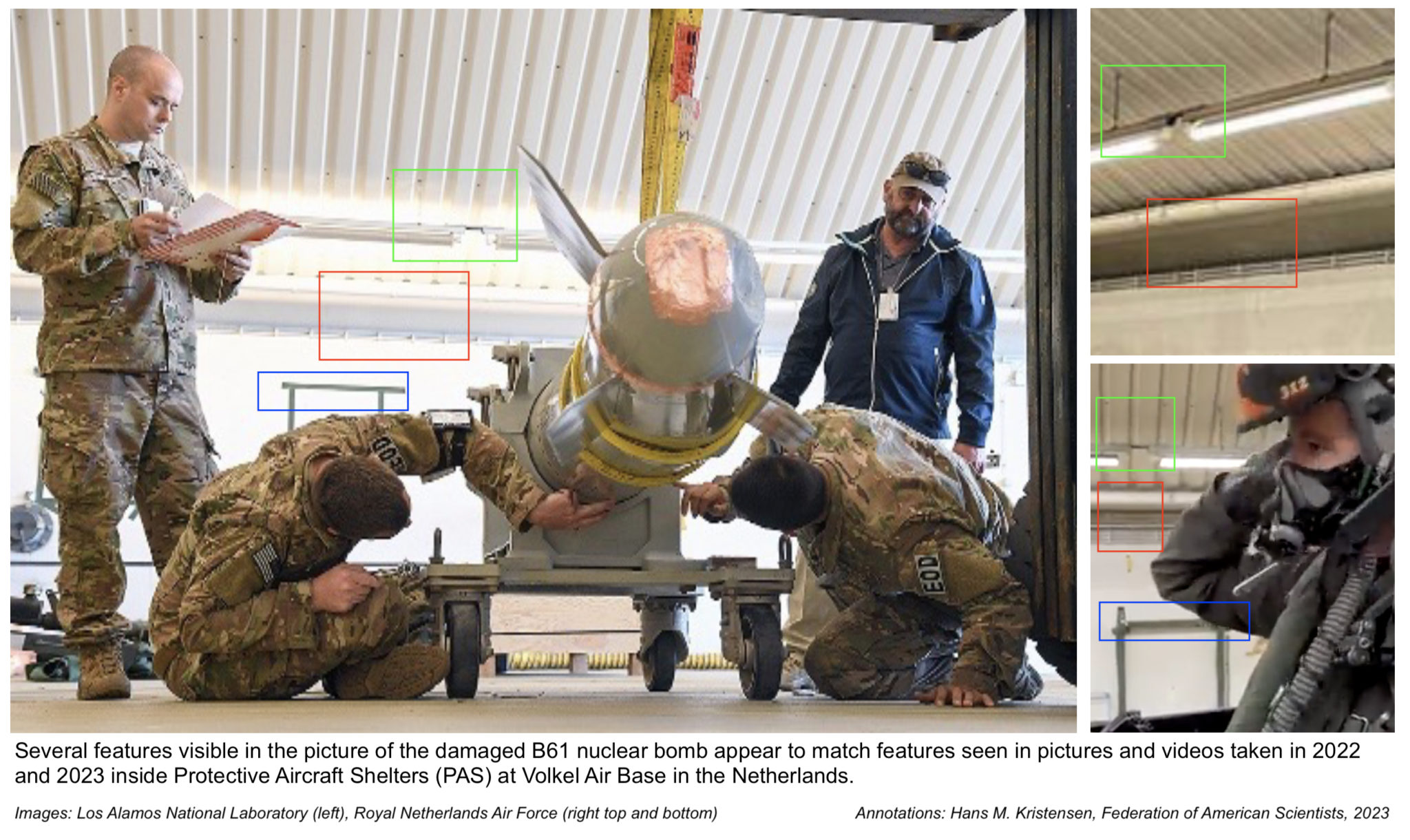

A photo in a Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) student briefing from 2022 shows four people inspecting what appears to be a damaged B61 nuclear bomb. The document does not identify where the photo was taken or when, but it appears to be from inside a Protective Aircraft Shelter (PAS) at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands.

It must be emphasized up front that there is no official confirmation that the image was taken at Volkel Air Base, that the bent B61 shape is a real weapon (versus a trainer), or that the damage was the result of an accident (versus a training simulation).

If the image is indeed from a nuclear weapons accident, it would constitute the first publicly known case of a recent nuclear weapons accident at an airbase in Europe.

Most people would describe a nuclear bomb getting bent as an accident, but U.S. Air Force terminology would likely categorize it as a Bent Spear incident, which is defined as “evident damage to a nuclear weapon or nuclear component that requires major rework, replacement, or examination or re-certification by the Department of Energy.” The U.S. Air Force reserves “accident” for events that involve the destruction or loss of a weapon.

It is not a secret that the U.S. Air Force deploys nuclear weapons in Europe, but it is a secret where they are deployed. Volkel Air Base has stored B61s for decades. I and others have provided ample documentation for this and two former Dutch prime ministers and a defense minister in 2013 even acknowledged the presence of the weapons. Volkel Air Base is one of six air bases in Europe where the U.S. Air Force currently deploys an estimated 100 B61 nuclear bombs in total.

The United States is modernizing its air-delivered nuclear arsenal including in Europe and Volkel and the other air bases in Europe are scheduled to receive the new B61-12 nuclear bomb in the near future.

Image Description

What does the image itself show? It appears to show a damaged B61 nuclear bomb shape strapped to a four-wheel trolly. The rear of the bomb curves significantly to the left and one of four tail fins is missing. There is also pink tape covering possible damage to the rear of the tail. The image first (to my knowledge) appeared in a Los Alamos National Laboratory student briefing published last year that among other topics described the mission of the Accident Response Group (ARG) to provide “world-wide support to the Department of Defense (DoD) in resolving incidents and accidents involving nuclear weapons or components in DoD custody at the time of the event.”

The personnel in the image also tell a story. The two individuals on the floor who appear to be inspecting the exterior damage on the weapon have shoulder pads with the letters EOD, indicating they probably are Explosive Ordnance Disposal personnel. According to the U.S. Air Force, “EOD members apply classified techniques and special procedures to lessen or totally remove the hazards created by the presence of unexploded ordnance. This includes conventional military ordnance, criminal and terrorist homemade items, and chemical, biological and nuclear weapons.”

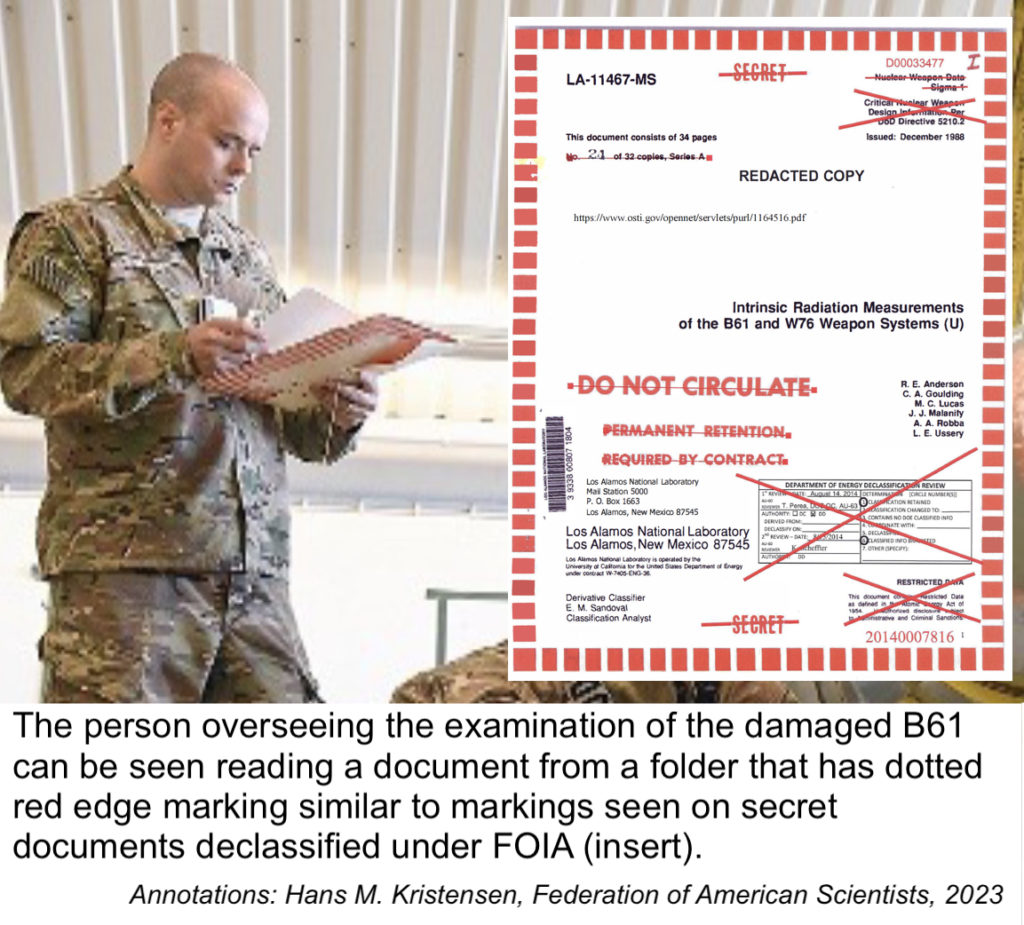

The person to the left overseeing the operation appears to be holding a folder with red dotted color markings that are similar to color patterns seen on classified documents that have been declassified and released under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) (see image to the right). The civilian to the right is possibly from one of the nuclear weapons laboratories. Los Alamos and Sandia both produced components to the B61 bomb.

What caused the damage to the B61 shape is unknown, but it appears to have been a significant force. It could potentially have been hit by a vehicle or bent out of shape by the weapons elevator of the underground storage vault.

Photo Geolocation

There is nothing in the photo itself or the document in which it was published that identify the location, the weapon, when it happened, or what happened. I have searched for the photo in search engines but nothing comes up. However, other photos taken inside Protective Aircraft Shelters (PASs) at Volkel Air Base show features that appear to match those seen in the accident photo.

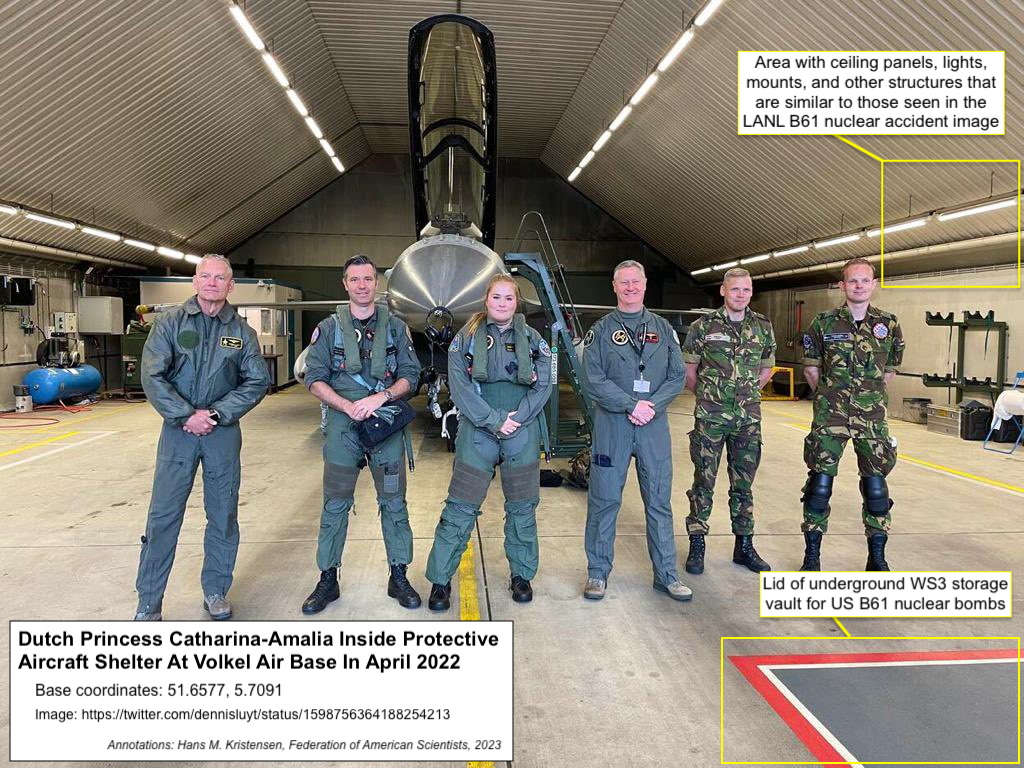

One of those photos is from April 2022 (the same month the Los Alamos briefing was published), when Dutch princess Catharina-Amalia visited Volkel Air Base and was taken on a flight in one of the F-16s. The Dutch Air Force commander highlighted the visit in a tweet that includes several photos, including one from inside an aircraft shelter. The photo shows the princess with Dutch air force officials including what appear to be the head of the Dutch air force and the commander of the nuclear-tasked 312th squadron at Volkel, an F-16 fighter-bomber, and part of the lid of an underground Weapons Storage System (WS3) vault built to store B61 nuclear bombs (see image below).

The 312th Squadron is part of the Dutch Air Force’s 1st Wing and is equipped with F-16 fighter-bombers with U.S.-supplied hardware and software that make them capable of delivering B61 nuclear bombs that the U.S. Air Force stores in vaults built underneath 11 of the shelters at the base. Dutch pilots receive training to deliver the weapons and the unit is inspected and certified by U.S. and NATO agencies to ensure that they have the skills to employ the bombs if necessary. In peacetime, the bombs are controlled by personnel from the U.S. Air Force’s 703rd Munition Support Squadron (MUNSS) at the base. If the U.S. military recommended using the weapons – and the U.S. president agreed and authorized use, the U.K. Prime Minister agreed as well, and NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) approved – then the weapon would be loaded onto a Dutch F-16 and the strike carried out by a Dutch pilot. Such an operation was rehearsed by the Steadfast Noon exercise in October last year.

One of these pilots (presumably), the commander of the 312th squadron, appeared in a Dutch Air Force video published in February on the one-year anniversary of the (second) Russian invasion of Ukraine. In the video, the commander climbs into the F-16 and puts on his helmet. At first a visor cover can be seen showing an orange-yellow mushroom cloud illustrating a nuclear explosion. However, when the video cuts and the commander turns to face the camera, the nuclear mushroom cloud cover is gone, presumably to avoid sending the wrong message to Russia (see below). The nuclear mushroom visor cover was also seen during the NATO Steadfast Noon exercise at Volkel AB in 2011.