Nuclear Exercises Amidst Ukrainian Crisis: Time For Cooler Heads

A Russian Tu-95MS long-range bomber drops an AS-15 Kent nuclear-capable cruise missiles from its bomb bay on May 8th. Six AS-15s were dropped from the bomb bay that day as part of a Russian nuclear strike exercise.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Less than a week after Russia carried out a nuclear strike exercise, the United States has begun its own annual nuclear strike exercise.

The exercises conducted by the world’s two largest nuclear-armed states come in the midst of the Ukraine crisis, as NATO and Russia appear to slide back down into a tit-for-tat posturing not seen since the Cold War.

Military posturing in Russia and NATO threaten to worsen the crisis and return Europe to an “us-and-them” adversarial relationship.

One good thing: the crisis so far has demonstrated the uselessness of the U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

Different Styles, Different Messages

Vladimir Putin’s televised commanding of the nuclear strike exercise – flanked by the presidents of Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the Russian National Defense Command Center – made one thing very clear: Putin wanted to showcase his nuclear might to the world. Russian military news media showed the huge displays in the Command Center with the launch positions and impact areas of long-range nuclear missiles launched from a road-mobile launchers and ballistic missile submarines.

A map in the National Defense Command Center shows the launch points and impact areas of nuclear missiles launched across Russia. Click to see larger version.

Other displays and images on the Russian Internet showed AS-15 Kent (Kh-55) nuclear cruise missiles launched from a Tu-95 “Bear” bomber (six missiles were launched), short-range ballistic missiles, and air-defense and ballistic missile defense interceptors reportedly repelled a “massive rocket nuclear strike” launched against Russia by “a hypothetical opponent.”

Of course everything was said to work just perfectly but there is no way to known how well the Russian forces performed, how realistic the exercise was designed to be, or what was different compared with previous exercises. Russia conducts these exercises each year and Russian military planners love to launch a lot of rockets very quickly with lots of smoke and noise (it looks impressive on television). But the exercise looked more like a one-day snap intended to showcase test launching of offensive and defensive forces rather than a significant new development.

The STRATCOM announcement of the Global Lightning exercise was, in contrast, much more timid, so far limited to a single press release. Mindful of the problematic timing, the press release said the timing was “unrelated to real-world events” and that the exercise has been planned for more than a year. But some new stories nonetheless linked the two events.

The STRATCOM press release didn’t say much about the exercise scenario or what forces would be involved. Only bombers – whose operations are highly visible and would probably be noticed anyway – were mentioned: 10 B-52 and up to six B-2 bombers. But SSBNs and ICBMs also participate in Global Lightning (although not with live test launches as in the Russian exercise) as well as refueling tankers and command and control units.

As its main annual strategic nuclear command post/field training exercise, STRATCOM uses Global Lightning to verify the readiness and effectiveness of U.S. nuclear forces and practice strike scenarios from OPLAN 8010-12 and other war plans against potential adversaries. Last updated in June 2012, OPLAN 8010-12 is being adjusted to incorporate decisions from the Obama administration’s June 2013 nuclear weapons employment strategy.

Although STRATCOM has only mentioned bombers participating in the Global Lightning 14 exercise, SSBNs and ICBMs also participate. This picture shows a V-22 Osprey delivering supplies to USS Louisiana (SSBN-424) during operations in the Pacific in 2012.

The previous Global Lightning exercise was held in 2012 (Global Lightning 2013 was canceled due to budget cuts) and is normally accompanied or followed by other nuclear-related exercises such as Global Thunder, Vigilant Shield, and Terminal Fury. In addition to strategic nuclear planning, STRATCOM supports regional nuclear targeting as well. The 2012 Global Lightning exercise supported Pacific Command’s Terminal Fury exercise in the Pacific and included several crisis and time-sensitive strike scenarios against extremely difficult target sets never seen before in Terminal Fury.

Back to Us and Them

One can read a lot into the exercises, if one really wants to. And some commentators have suggested that the exercises were deliberately intended as reminders to “the other side” of the Ukrainian crisis about the horrific military destructive power each side possesses.

I don’t think the Russian exercise or the U.S. Global Lightning exercise are directly linked to the Ukrainian crisis; they were planned long in advance. Nuclear weapons – and fortunately so – seem completely out of proportion to the circumstances of the situation in Ukraine.

Nonetheless, they do matter in the overall east-west sparing and the fact that the national leadership of Russia and the United States authorized these nuclear exercises at this particular time is a cause for concern. It is the first time nuclear forces have been rattled during the Ukrainian crisis. And because they are nuclear, the exercises add important weight to a pattern of increasingly militaristic behaviors on both sides.

Russia’s invasion of Crimea – bizarrely coinciding with Russia celebrating its defeat of a different invasion of the Soviet Union 73 years ago – to prevent loosing its Black Sea fleet area to an increasingly westerly looking Ukraine, and NATO responding by beefing up its military posture in Eastern Europe far from Ukraine to demonstrate “that NATO is prepared to meet and deter any threat to our alliance” – even though there are no signs of an increased Russian military threat against NATO territory in general – ought to have caused political leaders on both sides to delay the nuclear exercises to avoid fueling crisis sentiments and military posturing any further.

Instead, both sides now seem determined to stick to their guns and overturn the budding partnership and trust that had emerged after the Cold War. In doing so, the danger is, of course, that the military institutions on both sides are allowed to dominate the official responses to the crisis and deepen it rather than de-escalating and resolving it. No doubt, military hawks and defense contractors on both sides see an opportunity to use the Ukrainian crisis to get the defense budgets and weapons they have wanted for years but been unable to get because of budget cuts and the absence of a significant military “threat.”

A French Mirage follows a Russian Tu-22M3 Backfire bomber over the Baltic Sea in June 2013. Three months earlier, two Russian Tu-22M3s escorted by four Su-27 Flanker fighters simulated a nuclear attack on two targets in Sweden.

Russia has already announced plans to add 30 warships to the Black Sea Fleet and widen deployment of navy and air forces to four additional bases in Crimea.

The Russian air force has resumed long-range training flights with nuclear aircraft and often violates the air space of other countries. In March 2013, two Tu-22M3 backfire bombers reportedly simulated a nuclear strike against two targets in Sweden (although the aircraft did not violate Swedish air space at that time).

It is almost inevitable that increased NATO deployments and defense budgets in eastern member countries will trigger Russian military counter-steps closer to NATO borders. One of the first tell signs will be the Zapad exercise later this fall.

For its part, NATO has already deployed ships, aircraft, and troops to Eastern European countries and is considering how to further change its defense planning to respond with “air, land and sea ’reassurances’” to “a different paradigm, a different rule set” (translation: Russia is now an official military threat), according to NATO’s military commander General Philip Breedlove and “position those ‘reassurances’ across the breadth of our exposure: north, center, and south.”

NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen echoed Breedlove’s defense vision during a visit to Estonia on May 1st, saying the Ukrainian crisis had triggered a NATO response where “aircraft and ships from across the Alliance are reinforcing the security from the Baltic to the Black Sea.”

Breedlove and Rasmussen paint a military response that appears to go beyond the Ukrainian crisis itself and involve a broad reinforcement of NATO’s eastern areas. Breedlove got NATO approval for the initial deployments and exercises seen in recent weeks, but the defense ministers meeting in Brussels in June likely will prepare more fundamental changes to NATO military posture for approval at the NATO Summit in Wales in September.

General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen and other NATO officials describe a broad military reinforcement across NATO in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel says requires NATO countries to increase their defense budgets.

Among other aspects, those changes will probably involve modifying NATO’s General Intelligence Estimate (MC 161) and NATO Ministerial Guidance to explicitly identify Russia, once again, as a potential threat. Doing so will open the door for more specific Article 5 contingency plans for the defense of eastern European NATO countries.

In reality, the military responses to the Ukraine crisis include many efforts that have been underway within NATO since 2008. The Baltic States and Poland have been urging NATO to draw up contingency plans for the defense of Eastern Europe against Russian incursions or military attack. Two obstacles worked against this: declining defense budgets (who’s going to pay for it?) and a reluctance to officially declare Russia to be a military threat to NATO. The latter obstacle is now gone and U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel’s is now publicly using the Ukraine crisis to ask NATO countries to increase their defense budgets.

After a decade of depleting its declining resources on an costly, open-ended war in Afghanistan that it cannot win, the Ukrainian crisis seems to have given NATO a sense of new purpose: a return to its core mission of defending NATO territory. “Russia’s actions in Ukraine have made NATO’s value abundantly clear,” Hagel said earlier this month, “and I know from my frequent conversations with NATO defense ministers that they do not need any convincing on this point.”

But one of the biggest obstacles to increasing defense budgets, Hagel said, “has been a sense that the end of the Cold War ushered in the ‘end of history’ – an end to insecurity, at least in Europe and the end [of] aggression by nation states. But Russia’s action in Ukraine shatter that myth and usher in bracing new realities,” he concluded, and “over the long term, we should expect Russia to test our alliance’s purpose, stamina, and commitment.”

In other words, it’s back to us and them.

It is difficult to dismiss Eastern European jitters about Russia – after all, they were occupied by the Soviet Union and joined NATO specifically to get the security guarantee so never to be occupied again. And Russia’s unlawful annexation of Crimea has completely shattered its former status as a European partner.

But the big question is whether NATO responding to Ukraine by beefing up its military inadvertently plays into the hands of Russian hardliners and will serve to deepen rather than easing military competition in Europe.

Why the Putin regime would respond favorably to NATO increasing its military posture in Eastern Europe is not clear. Yet it seems inconceivable that NATO could chose not to do so; after all, providing military protection is the core purpose of the Alliance.

At the same time, the more they two sides posture to demonstrate their resolve or unity, the harder it will be for them to de-escalate the crisis and rebuild the trust. Remember, we’ve been down that road and it took us six decades to get out.

Rather, it seems more likely that beefing up military forces and operations will reaffirm, in the eyes of Russian policy makers and military planners, what they have already decided; that NATO is a threat that is trying to encroach Russia who therefore must protect its borders and secure a sphere of influence as a buffer. Georgy Bovt’s recent analysis in Moscow Times of the Russian mindset is worthwhile reading.

The Irrelevance of Tactical Nuclear Weapons

So what does all of that mean for nuclear weapon in Europe? Remember, they’re supposed to reassure the NATO allies!

I hear many say that the Ukrainian crisis makes it very difficult to imagine a reduction, much less a withdrawal, of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe. Some people have even argued that the Ukrainian crisis could have been avoided if Ukraine had kept the nuclear weapons the Soviet Union left behind when it crumbled in 1991 (the argument ignores that Ukraine didn’t have the keys to use the weapons and would have been isolated as a nuclear rogue if it had not handed them over).

Only two years ago, NATO rejected calls for a withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe based on the argument that the deployment continues to serve an important role as a symbol of the U.S. security commitment to Europe and because eastern European NATO countries wanted the weapons in Europe to be assured about their protection against Russia. The May 2012 Defense and Deterrence Posture Review (DDPR), implementing the Strategic Concept from 2010, reaffirmed status quo by concluding “that the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.”

A B61 nuclear bomb trainer is loaded onto an F-16 somewhere in Europe, probably at Aviano Air Base in Italy. Some Eastern European NATO allies argue that the nuclear weapons provide important reassurance, but request deployment additional non-nuclear assets to deter Russia.

Yet here we are, only two years later, where the nuclear weapons have proven absolutely useless in reassuring the allies in the most serious crisis since the Cold War. Indeed, it is hard to think of a stronger reaffirmation of the impotence and irrelevance of tactical nuclear weapons to Europe’s security challenges than NATO’s decision to deploy conventional forces and beef up conventional contingency planning and defense budgets in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea.

Put in another way, if the U.S. nuclear deployment was adequate for an effective deterrence and defense posture, why is it now inadequate to assure the allies?

In fact, one can argue with some validity that spending hundreds of millions of dollars on maintaining U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe after the end of the Cold War has done very little for NATO security, except wasting resources on a nuclear capability that is useless rather than spending the money on conventional capabilities that can be used. It is about fake versus real assurances.

The deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe seems to be for academic and doctrinal discourses rather than for real security. In the real world they don’t seem to matter much and seem downright useless for the kinds of security challenges facing NATO countries today. But try telling that to current and former officials who have been spending the past five years lobbying and educating Eastern NATO governments on why the weapons should stay.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Resolving the Crisis in Ukraine: International Crisis Group’s Recommendations

As readers of the FAS Strategic Security Blog know, we have been concerned about the potential of the crisis in Ukraine to escalate, further worsening U.S.-Russian relations and possibly resulting in armed conflict involving NATO and Russia. As the May 25th presidential election in Ukraine is fast approaching, this post draws attention to advice and recommendations from the International Crisis Group, a highly respected non-governmental organization. Here’s the announcement of the major findings from the group’s newest report Ukraine: Running out of Time.

[As an organization comprising thousands of members with differing views, FAS headquarters reminds readers that this and other posts do not represent the position of FAS as an organization. Instead, these posts provide a platform for reasoned discourse and exchange of ideas. Constructive comments are welcomed.]

“Ukraine needs a government of national unity that reaches out to its own people and tackles the country’s long overdue reforms; both Russia and Western powers should back a vision for the country as a bridge between East and West, not a geopolitical battleground.”

The report “offers recommendations to rebuild and reform the country and reverse the geopolitical standoff it has provoked. The Kyiv government has been unable to assert itself or communicate coherently and appears to have lost control of parts of the country to separatists, emboldened if not backed by Russia. To prevent further escalation, Ukraine needs strong international assistance and the commitment of all sides to a solution through dialogue, not force.

The report’s major findings and recommendations are:

- Although conditions for the election are far from ideal, it must take place as planned and nationwide. The vote is needed to produce a new leader with a popular mandate to steer the country through a process of national reconciliation and economic reform. All presidential candidates should, before the polls, commit to establish a broad-based government of national unity; the new president’s first priority must be to form such a government.

- Ukrainian leaders should reach out immediately to the south and east and explain plans for local self-government and minority rights; they should also declare that they do not desire NATO membership.

- Ukraine’s damage goes far beyond separatism. It is the fruit of decades of mismanagement and corruption across security organs and most other arms of government. Far-reaching reform of the security sector and measures to strengthen the rule of law are crucial.

- Russia should declare unqualified support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity and withdraw all troops from the borders, as well as any paramilitaries who have infiltrated from Crimea or elsewhere. It should persuade Russian speakers in the south and east to end their occupations of government buildings and attacks on local security apparatuses and disband their militias.

- The U.S. and EU need to convey a consistent and measured message, recognizing – even if not accepting – Moscow’s take on the crisis’s origins. This message should comprise political support for Kyiv to conduct elections; political, financial and expert support for a national unity government to carry out stabilization measures; measures to make Ukraine viable for investors; further sanctions to bite deeper into Russia’s economy if it does not change course; and quiet high-level talks with Moscow aimed at resolving the crisis.

- Both Moscow and Western powers should emphasize that the present situation can only be resolved by diplomatic means; express support for a post-election government of national unity; take all possible measures to avoid geopolitical confrontation; and insulate other mutual concerns from divisions over Ukraine.

‘On the ground in Ukraine today, Russia has immediate advantages of escalation,’ says Paul Quinn-Judge, Europe and Central Asia Program Director. ‘Over time, the West likely has the economic and soft-power edge. A successful, democratic Ukraine – integrated economically in the West but outside military alliances, and remaining a close cultural, linguistic and trading partner of Russia – would benefit all.’”

Preventing Ukraine From Spiraling Out of Control

The crisis in Ukraine continues to simmer, but thankfully has not yet boiled over. Here are some of the developments since I last wrote on this topic, followed by some thoughts on what is needed to minimize the risk of the conflict spiraling out of control.

Former Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma assessed the situation as follows:

Russia does not recognize the legitimacy of the current government in Kyiv and will not negotiate with it. Ukraine has no chance there. Ukraine could have taken concrete steps in this direction in the beginning but we didn’t do that. For instance, a delegation of lawmakers could have gone to Moscow [to bring Russia into the process.] …

To analyze Russia’s actions, you have to try to understand Putin’s point of view. Russia has always feared having NATO right under Moscow’s nose. … Putin never trusted Ukraine, especially its government. He always assumed that one day someone would come to power in Ukraine that would ignore the Russian-Ukrainian friendship, and Ukraine would join the European Union and NATO. …

I don’t see any candidate [for the Ukrainian presidency] who enjoys enough popularity to unite Ukraine. …The future leadership should include representatives of all regions in order to unite the country. If it consists of only half of Ukraine, there will consequences in the other half of the country.

Prof. Keith Darden of American University wrote in Foreign Affairs:

A pro-European, pro-NATO government ruling a regionally divided country – and one that is quite vulnerable to Russian military intervention – is a recipe for instability, not for European integration. Simply pushing forward with EU association and NATO integration without pushing the government in Kiev to address its illegitimacy problems through means other than arrest is not much of a strategy. It’s not even much of a gamble, as it is almost certain to fail. One way or another, power in Ukraine needs to be spread out. …

The most obvious way to do that is through some form of constitutional change. Call it what you want: decentralization, federalization, regionalization. … Kiev needs to transfer some very substantial powers, including those over education, language, law, and taxation, to the regions. … The Russian plan to federalize Ukraine, which, in reality, is a plan to turn Ukraine into a weak confederation where the central government is largely ceremonial, is a step too far. … [But] As long as Ukraine retains its highly centralized winner-take-all political system, and one regional faction sits in Kiev with the backing of either Russia or the West, Ukraine is going to be unstable. With a little bit of constitutional accommodation, though, the divided house just might stand.

The interim Ukrainian government (or junta in Moscow’s view) has repeatedly attempted to use military force to evict pro-Russian demonstrators (or terrorists in Kiev’s view) from government buildings in the eastern part of Ukraine. These efforts have had limited success, with some Ukrainian units surrendering or defecting to the pro-Russian side. This may lead (or already have led) Kiev to consider using some of Ukraine’s more virulently anti-Russian elements (e.g., the Pravy (Right) Sektor and the Svoboda Party) since they can be counted on not to avoid bloodshed.

Russia sees the West as exercising a blatant double standard in that it warned Yanukovych not to use military force against the Maidan demonstrators who eventually brought down his government, yet approves the use of similar force against pro-Russian demonstrators. Of course, Russia itself is not immune to holding double standards, but that makes things doubly dangerous. If both sides in a conflict mistakenly believe they are in the right, they then expect the other (“wrong”) side to back down. When both sides have thousands of nuclear weapons, the risk is clearly heightened.

Conditions almost boiled over last Friday (May 2) when pro- and anti-Russian gangs clashed in a bloody riot in Odessa and dozens of pro-Russian demonstrators were burned alive in a fire. According to the New York TImes:

What followed were hours of bloody street clashes involving bats, pistols and firebombs. … The pro-Russians, outnumbered by the Ukrainians, fell back … [and] sought refuge in the trade union building.

Yanus Milteynus, a 42-year-old construction worker and pro-Russian activist, said he watched from the roof as the pro-Ukrainian crowd threw firebombs into the building’s lower windows, while those inside feared being beaten to death by the crowd if they tried to flee. …

The conflict is hardening hearts on both sides. As the building burned, Ukrainian activists sang the Ukrainian national anthem, witnesses on both sides said. They also hurled a new taunt: “Colorado” for the Colorado potato beetle, striped red and black like the pro-Russian ribbons. Those outside chanted “burn Colorado, burn,” witnesses said. Swastikalike symbols were spray painted on the building, along with graffiti reading “Galician SS,” though it was unclear when it had appeared, or who had painted it.

It should be noted that anti-Russian reports allege that the fire was started by the pro-Russian group when they threw Molotov cocktails down from the upper floors. It is impossible at this point in time to say which version is true, and that cautionary note applies to almost all reports.

Harvard’s Prof. Graham Allison summarized the nuclear risk well in a recent article in The National Interest:

The thought that what we are now witnessing in Ukraine could trigger a cascade of actions and reactions that end in war will strike most readers as fanciful. Fortunately, it is. But we should not forget that in May 1914, the possibility that the assassination of an Archduke could produce a world war seemed almost inconceivable. History teaches that unlikely, even unimaginable events do happen.

Given that less than six years elapsed between the Georgian War and this current crisis, each with the potential to lead to armed conflict between US and Russian forces or nuclear threats, even a small probability for each event to escalate can result in an unacceptable cumulative risk.

Adding to the risk, British Foreign Minister William Hague just told Georgia that its bid to join NATO enjoys his “very clear support.” Such promises appear to have played a role both in emboldening Georgia to fire the first shots in its 2008 war with Russia and in Russia’s outsized reaction. While the promise was made to Georgia, it seems clearly linked to the situation in Ukraine.

To reduce the risk of the Ukrainian crisis spiraling out of control, both the West and Russia should stop viewing the conflict as a football game in which there is a winner and a loser. Instead, we need to start being more concerned with creating a situation in which all the people of Ukraine can live reasonable lives, without fear of subjugation or physical harm.

Russian ICBM Force Modernization: Arms Control Please!

By Hans M. Kristensen

In our Nuclear Notebook on Russian nuclear forces from March this year, Robert S. Norris and I described the significant upgrade that’s underway in Russia’s force of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs).

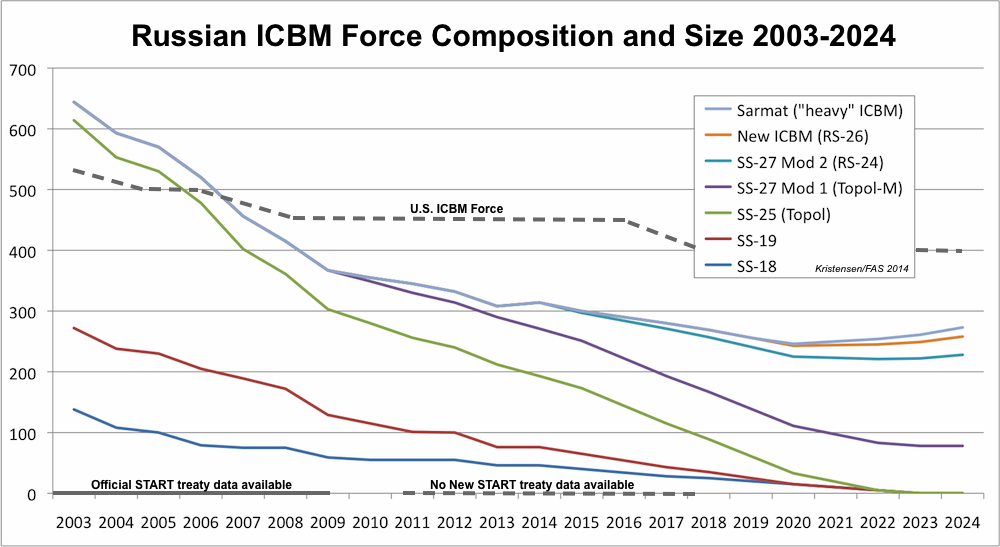

Over the next decade, all Soviet-era ICBMs will be retired and replaced with a smaller force consisting of mainly five variants of one missile: the SS-27.

After more than a decade-and-a-half of introduction, the number of SS-27s now makes up a third of the ICBM force. By 2016, SS-27s will make up more than half of the force, and by 2024 all the Soviet-era ICBMs will be gone.

The new force will be smaller and carry fewer nuclear warheads than the old, but a greater portion of the remaining warheads will be on missiles carried on mobile launchers.

The big unknowns are just how many SS-27s Russia plans to produce and deploy, and how many new (RS-26 and Sarmat “heavy”) ICBMs will be introduced. Without the new systems or increased production of the old, Russia’s ICBM force would probably level out just below 250 missiles by 2024. In comparison, the U.S. Air Force plans to retain 400 ICBMs.

This disparity and the existence of a large U.S. reserve of extra warheads that can be “uploaded” onto deployed missiles to increase the arsenal if necessary drive top-heavy ICBM planning in the Russian military which seeks to maximize the number of warheads on each missile to compensate for the disparity and keep some degree of overall parity with the United States.

This dilemma suggests the importance of reaching a new agreement to reduce the number deployed strategic warheads and missiles. A reduction of “up to one-third” of the current force, as recently endorsed by the new U.S. nuclear employment strategy, would be a win for both Russia and the United States. It would allow both countries to trim excess nuclear capacity and save billions of dollars in the process.

Phased Deployment

Introduction of the SS-27 has come in two phases. The first phase, which last from 1997 to 2013, involved deployed the single-warhead type (SS-27 Mod 1; Topol-M) in silos and on road-mobile launchers. The silo-based version was deployed first, replacing SS-19s in the 60th Missile Division at the Tatishchevo missile field outside Saratov. The deployment was completed in 2013 (see picture below) after 60 SS-27 Mod 1 missiles had been lowered into former SS-19 silos at a slow pace of less than 4 missile in average per year.

An SS-27 Mod 1 (Topol-M) is lowered into a former SS-19 silo at the Tatishchevo missile field outside Saratov.

In 2006, deployment of the first road-mobile SS-27 Mod 1 began with the 54th Guards Missile Division at Teykovo northeast of Moscow. The deployment was completed in 2010 with 18 missiles in two regiments.

With completion of the SS-27 Mod 1 deployment of 78 missiles, efforts have since shifted to deployment of a MIRVed version of the SS-27, known as SS-27 Mod 2, or RS-24 Yars in Russia. It is essentially the same missile as the Mod 1 version except the payload “bus” has been modified to carry multiple independently targetable warheads (MIRV). Each missile is thought to be able to carry up to 4 warheads, although there is uncertainty about what the maximum capacity is (but it is not 10 warheads, as often claimed in Russian news media).

The first road-mobile SS-27 Mod 2s were deployed at Teykovo in 2010, alongside the SS-27 Mod 1s already deployed there. For the foreseeable future, all new Russian ICBM deployments will be of MIRVed versions of the SS-27, although a “new ICBM” and a “heavy ICBM” are also being developed.

In 2012, preparations began for introduction of SS-27 Mod 2 at three additional missile divisions. At the 28th Missile Guards Division at Kozelsk southwest of Moscow, conversion of former SS-19 silos (see picture below) to carry the SS-27 Mod 2 is underway with deployed of the first regiment (10 missiles) scheduled this year. How many missiles will be deployed at Kozelsk is unclear. The missile field originally included 60 SS-19 silos but half have been demolished so perhaps the plan is for three regiments with 30 SS-27 Mod 2 missiles. After silo-based RS-24s are installed at Kozelsk, deployment will follow at the 13th Missile Division at Dombarovsky, replacing the SS-18s currently deployed there.

A former SS-19 ICBM silo at Kozelsk is being upgraded to receive the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24 Yars) ICBM. Deployment begins this year.

In addition to Kozelsk, preparations are also underway to upgrade three road-mobile SS-25 garrisons to the SS-27 Mod 2. At this point, this includes the 51st Missile Guards Division at Irkutsk, the 39th Guards Missile Division at Novosibirsk, and the 42nd Missile Division at Nizhniy Tagil.

Preparation started at Novosibirsk in 2012, where two of four garrisons are under conversion. One of these (Novosibirsk 4; see further description below) is nearly complete. Conversion started at Irkutsk in 2012 with dismantling of SS-25 garages at one of the three remaining garrisons. At Tagil, SS-27 Mod 2 introduction is underway at two of three remaining SS-25 garrisons. In December 2013, the first SS-27 Mod 2 regiment at Novosibirsk (9 launchers) and one partially equipped (6 launchers) regiment at Tagil were put on “experimental combat duty.”

The remaining SS-25 divisions – the 7th Guards Missile Division at Vypolsovo, the 14th Missile Division at Yoshkar-Ola, and the 35th Missile Division at Barnaul – have not been mentioned for SS-27 Mod 2 upgrade and seem destined for retirement. One of the three garrisons at Yoshkar-Ola has been inactivated.

Below follows a more detailed description of the upgrade to SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) underway at Novosibirsk.

SS-27 Upgrade at Novosibirsk

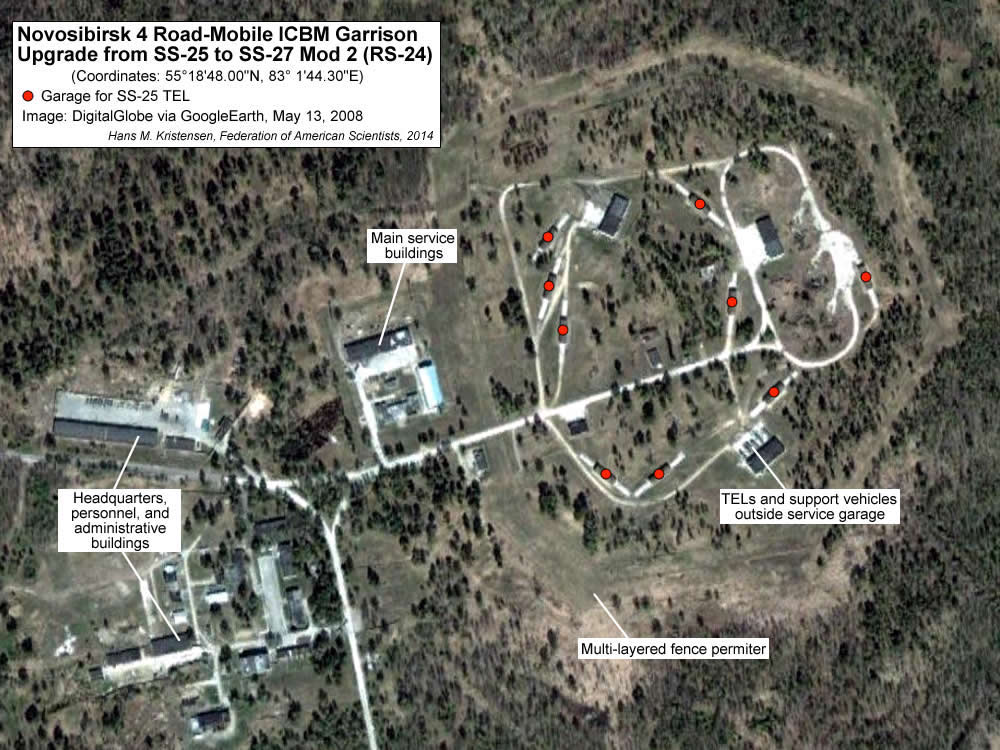

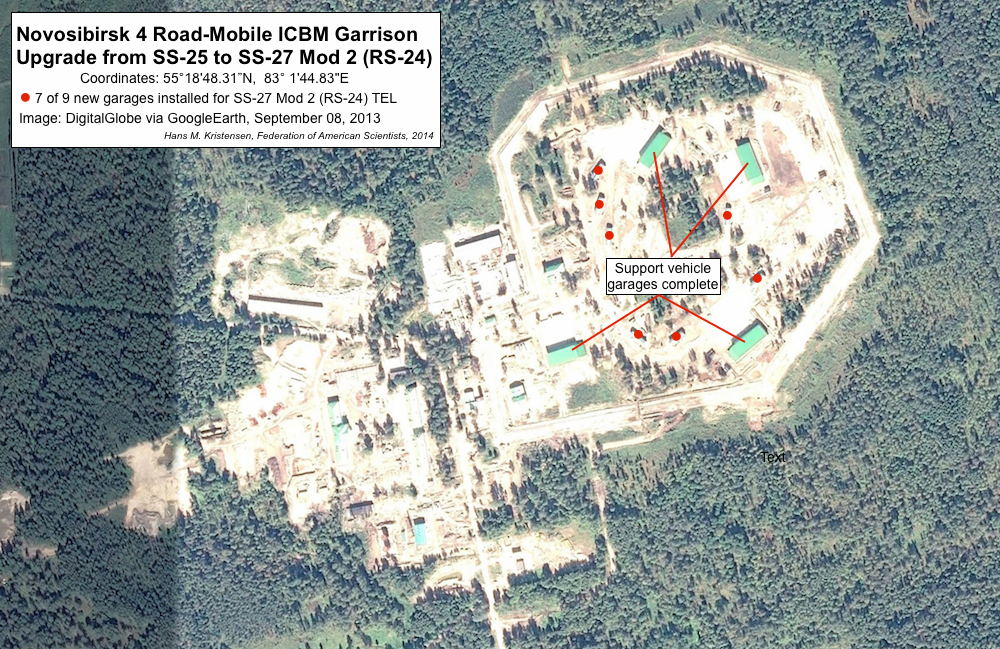

As mentioned above, the 39th Guards Missile Division at Novosibirsk is being upgraded from the solid-fuel road-mobile single-warhead SS-25 ICBM to the solid-fuel road-mobile MIRVed SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24). A series of unique satellite images provided by Digital Globe to Google Earth show the upgrade of one of four garrisons (Novosibirsk 4) between 2008 and 2013.

The first image from May 2008 (see below) shows the garrison with all nine garages for SS-25 road-mobile launchers (TELs) clearly visible inside the multi-layered fence perimeter. Several TELs and support vehicles are parked outside one of three service buildings.

The second image from June 2012 (see below) shows that all nine TEL garages have been dismantled and the roof is missing on the three service vehicle buildings. Two new service buildings are under construction just outside the fence perimeter and several buildings have been demolished in preparation for new administrative and technical buildings.

The third image, taken in February 2013, shows the fence perimeter at the southwest corner of the garrison has been extended westward to include the new service buildings. This extension is similar to the change that was made at Teykovo when two garrisons were equipped with the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24). The image indicates that support vehicle garages inside the fence perimeter are almost done, and that administrative and technical buildings outside the perimeter have been added.

The fourth image (see below), from September 2013, shows installation of new TEL garages for the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) launchers well underway, with seven of eventually nine garages visible. The green roofs of the four large service vehicle garages are clearly visible, as are the new administrative and technical building outside the fence perimeter.

The Future ICBM Force

Predicting the size and composition of the Russian ICBM force structure into the future comes with a fair amount of uncertainty because Russia doesn’t release official data on its nuclear forces, because U.S. intelligence agencies no longer publish detailed information on Russian nuclear forces, and because Russian aggregate data under the New START treaty is not made public (unlike during the previous START treaty). Nonetheless, based on previous history, scattered officials statements, and news media reports, it is possible to make a rough projection of how the Russian ICBM might evolve over the next decade (see graph below).

This shows that the size of the Russian ICBM force dropped below the size of the U.S. ICBM force in 2007 mainly due to the rapid reduction of the SS-25 ICBM. By the early 2020s, according to recent announcements by Russian military officials, all SS-18, SS-19, and SS-25 ICBMs will be gone. Development of a new ICBM – apparently yet another version of the SS-27 – known in Russia as the RS-26 is underway for possible introduction in 2015. And a new liquid-fuel “heavy” ICBM known in Russia as the Sarmat, and nicknamed “Son of Satan” because it apparently is intended as a replacement for the SS-18 (which was code-named Satan by the United States and NATO) is said to be scheduled for introduction around 2020.

This development would leave a Russian ICBM force structure based on five modifications of the solid-fuel SS-27 (silo- and mobile-based SS-27 Mod 1; silo- and mobile-based SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24); and the RS-26) and the liquid-fuel Sarmat with a large payload – either MIRV or some advanced payload to evade missile defense systems. Although the future force will be smaller, a greater portion of it will be MIRVed – up from approximately 36 percent today to roughly 70 percent by 2024. This increasingly top-heavy ICBM force is bad for U.S-Russian strategic stability.

I hope I’m mistaken about the possible increase in the Russian ICBM force after 2020. In fact, it seems more likely that the Russian economy will not be able to support the production and deployment of “over 400 modern land and sea-based inter-continental ballistic missiles” that President Putin promised in 2012. But if I’m not mistaken, then it would be an immensely important development. Not that I think it would matter that much militarily in the foreseeable future or necessarily signal a new arms race. But it would be a significant break with the trend we have seen in Russian nuclear forces since the end of the Cold War, and it would create serious problems for the stability of the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime. It is important that the Russian government provides more transparency about its nuclear force structure plans and demonstrate that it is not planning to increase its ICBM force shortly after the New START treaty expires in 2018.

Regardless, there is an increasing need for Russia and the United States to make more progress on nuclear arms control. Notwithstanding its important verification regime, the New START treaty was too modest to impress anyone (it has no real effect on Russian nuclear forces and it is so modest that the United States plans to keep emptied ICBM silos instead of destroying them). A good start would be a new arms control agreement with “up to one-third” fewer deployed strategic warheads and launchers than permitted by the New START Treaty, as recently endorsed by the U.S. Nuclear Employment Strategy. Such an agreement would force Russia to reduce the warhead loading on its ICBMs and force the United States to reduce its large ICBM force.

It is also important that the United States and Russia revisit the MIRV-ban. The START II treaty, which was signed but not ratified and later abandoned by Vladimir Putin and George W. Bush in 2002, included a ban on MIRVed ICBMs. Apart from reducing the warheads the two nuclear superpowers would be able to launch agains each other, a MIRV ban would also serve the vital role of discouraging other nuclear-armed states from deploying multiple warheads on their ballistic missiles in the future, which could otherwise significantly increase their nuclear arsenals and result in regional arms races.

Trying to pursue new reductions in excessive and expensive nuclear forces and avoid counterproductive modernization programs is perhaps even more important now given the souring relations caused by the crisis in Ukraine. Don’t forget: even at the height of the Cold War it was possible – in fact essential – to reach nuclear arms control agreements.

Additional background: Russian Nuclear Forces, 2014 | Russian SSBN Fleet

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Modernization Briefings at the NPT Conference in New York

By Hans M. Kristensen

Last week I was in New York to brief two panels at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (phew).

The first panel was on “Current Status of Rebuilding and Modernizing the United States Warheads and Nuclear Weapons Complex,” an NGO side event organized on May 1st by the Alliance for Nuclear Accountability and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). While describing the U.S. programs, I got permission from the organizers to cover the modernization programs of all the nuclear-armed states. Quite a mouthful but it puts the U.S. efforts better in context and shows that nuclear weapon modernization is global challenge for the NPT.

The second panel was on “The Future of the B61: Perspectives From the United States and Europe.” This GNO side event was organized by the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation on May 2nd. In my briefing I focused on providing factual information about the status and details of the B61 life-extension program, which more than a simple life-extension will produce the first guided, standoff nuclear bomb in the U.S. inventory, and significantly enhance NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

The two NGO side events were two of dozens organized by NGOs, in addition to the more official side events organized by governments and international organizations.

The 2014 PREPCOM is also the event where the United States last week disclosed that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has only shrunk by 309 warheads since 2009, far less than what many people had anticipated given Barack Obama’s speeches about “dramatic” and “bold” reductions and promises to “put an end to Cold War thinking.”

Yet in disclosing the size and history of its nuclear weapons stockpile and how many nuclear warheads have been dismantled each year, the United States has done something that no other nuclear-armed state has ever done, but all of them should do. Without such transparency, modernizations create mistrust, rumors, exaggerations, and worst-case planning that fuel larger-than-necessary defense spending and undermine everyone’s security.

For the 185 non-nuclear weapon states that have signed on to the NPT and renounced nuclear weapons in return of the promise made by the five nuclear-weapons states party to the treaty (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, and the United States) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to the cessation of the nuclear arms race at early date and to nuclear disarmament,” endless modernization of the nuclear forces by those same five nuclear weapons-states obviously calls into question their intension to fulfill the promise they made 45 years ago. Some of the nuclear modernizations underway are officially described as intended to operate into the 2080s – further into the future than the NPT and the nuclear era have lasted so far.

Download two briefings listed above: briefing 1 | briefing 2

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Obama Administration Decision Weakens New START Implementation

At the same time the Air Force is destroying 50 silos at Malmstrom AFB (above) and another 50 at F.E Warren AFB emptied by the Bush administration, the Obama administration has decided to retain 50 silos scheduled to be emptied under the New START treaty.

By Hans M. Kristensen

After four years of internal deliberations, the U.S. Air Force has decided to empty 50 Minuteman III ICBMs from 50 of the nation’s 450 ICBM silos. Instead of destroying the empty silos, however, they will be kept “warm” to allow reloading the missiles in the future if necessary.

The decision to retain the silos rather than destroy them is in sharp contrast to the destruction of 100 empty silos currently underway at Malmstrom AFB and F.E. Warren AFB. Those silos were emptied of Minuteman and MX ICBMs in 2005-2008 by the Bush administration and are scheduled to be destroyed by 2016.

A New Development

The Obama administration’s decision to retain the silos 50 silos “reduced” under the New START treaty instead of destroying them is a disappointing new development that threatens to weaken New START treaty implementation and the administration’s arms reduction profile. And it appears to be a new development.

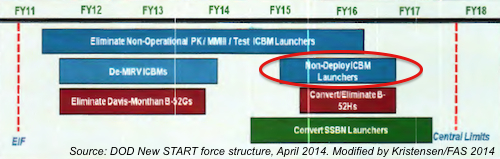

A chart in a DOD’s unclassified report to Congress shows that the plan to retain the 50 non-operational ICBM launchers is different than the treaty implementation efforts so far, which have been designed to “eliminate” non-operational launchers.

The plan to retain non-deployed ICBM launchers is different than other aspects of the U.S. New START implementation plan

Indeed, a senior defense official told the Associated Press that the Pentagon had never before structured its ICBM force with a substantial number of missiles in standby status.

Reducing Force Structure Flexibility

The decision to retain the 50 empty silos is also puzzling because it reduces U.S. flexibility to maintain the remaining nuclear forces under the New START limit. The treaty stipulates that the United States and Russia each can only have 700 deployed launchers and 100 non-deployed launchers. But the 50 empty silos will count against the total limit, essentially eating up half of the 100 non-deployed launcher limit and reducing the number of spaces available for missiles and bombers in overhaul.

If, for example, two SSBNs (with 40 missiles), two ICBMs, and eight bombers were undergoing maintenance at the same time, no additional launchers could be removed from deployed status for maintenance unless the deployed force was reduced below 700 launchers. This is not inconceivable. In September 2013, for example, 76 SLBM launchers and 21 B-2A/B-52H bombers (a total of 97 launchers) were counted as non-deployed.

Why the administration would accept such constraints on the flexibility of the U.S. nuclear force posture simply to satisfy the demands of the so-called ICBM caucus in Congress is baffling.

The Reductions

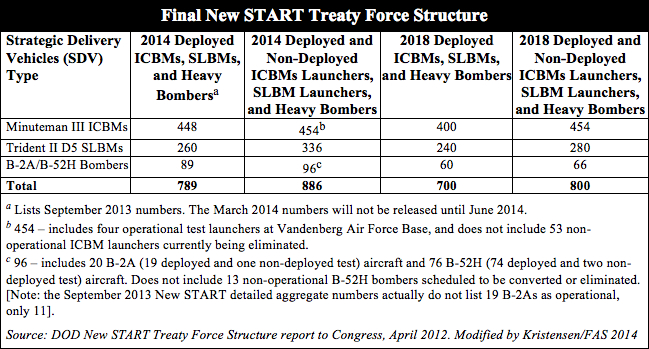

With the DOD New START force structure decision, the future force is now set. The DOD report includes the table below (note: a column with the 2014 deployed launchers has been added to improve comparison), which is also reproduced in a fact sheet (with some corrections and additional information about bombers):

Other than the decision to retain, rather than dismantle, the excess 50 ICBM silos, there are no real surprises. The reductions in actual nuclear forces are very modest. Moreover, the June 2013 Nuclear Weapons Employment Strategy of the United States, which is intended to look beyond 2018, ordered no additional force structure reductions below the New START limits, yet determined that the United States could meet its national and international obligations with up to one-third fewer deployed weapons (1,100 warheads on 470 launchers).

Strategic Implications

What would be the scenario in which the United States would have to redeploy missiles in the extra 50 “warm” silos that the administration has decided to retain? Notwithstanding the crisis in Ukraine, it is hard to envision one.

The 50 Minuteman III missiles from the silos will be stored at Hill Air Force Base for potential reloading into the “warm” silos or eventually to be used as flight test assets. What scenario would necessitate redeploying the missiles?

Image credit: @Paul Shambroom/Institute

Unlike the United States, Russia is already well below the New START limit and currently has about 140 ICBMs in silos and another 170 on mobile launchers for a total force of a little over 300 missiles. Despite Russian deployment of new missiles, this ICBM force is likely to drop well below 300 by the early 2020s.

Moreover, the Pentagon determined in 2012 that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty” (emphasis added).

To compensate for the ICBM launcher imbalance and maintain some degree of overall parity with the U.S. arsenal, Russia is deploying more warheads on each of its ICBMs.

This top-heavy posture is bad for strategic stability. It is in the U.S. national security interest to reduce this disparity to increase strategic stability between the world’s two largest nuclear powers. The decision to retain excess ICBM silos instead of destroying them contributes to a Russian misperception that the United States is intent on retaining a strategic advantage and a breakout capability from the New START treaty to quickly increase its deployed nuclear forces if necessary.

The administration can and should change its decision and destroy the ICBM silos that are emptied under New START.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Show Russian Increase, US Decrease Of Deployed Warheads

By Hans M. Kristensen

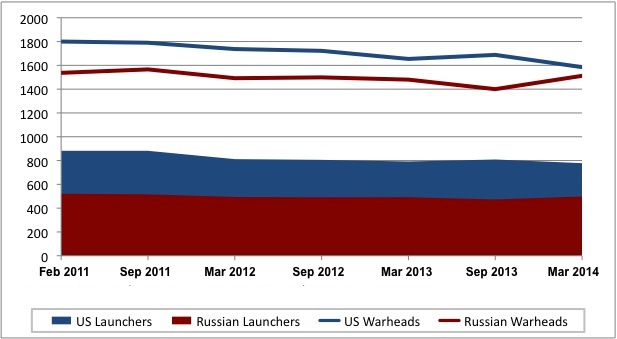

The latest aggregate data released by the US State Department for the New START treaty show that Russia has increased its counted deployed strategic nuclear forces over the past six months.

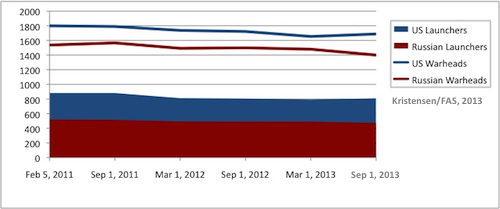

The data show that Russia increased its deployed launchers by 25 from 473 to 498, and the warheads attributed to those launchers increased by 112 from 1,400 to 1,512 compared with the previous count in September 2013.

During the same period, the United States decreased its number of deployed launchers by 31 from 809 to 778, and the warheads attributed to those launchers decreased by 103 from 1,688 to 1,585.

The increase of the Russian count does not indicate that its in increasing its strategic nuclear forces but reflects fluctuations in the number of launchers and their attributed warheads at the time of the count. At the time of the previous data release in September 2013, the United States appeared to have increased its forces. But that was also an anomaly reflecting temporary fluctuations in the deployed force.

Both countries are slowly reducing their strategic nuclear weapons to meet the New START treaty limit by 2018 of no more than 1,550 strategic warheads on 700 deployed launchers. Russia has been below the treaty warhead limit since 2012 and was below the launcher limit even before the treaty was signed. The United States has yet to reduce below the treaty limit.

Since the treaty was signed in 2010, the United States has reduced its counted strategic forces by 104 deployed launchers and 215 warheads; Russia has reduced its counted force by 23 launchers and 25 warheads. The reductions are modest compared with the two countries total inventories of nuclear warheads: Approximately 4,650 stockpiled warheads for the United States (with another 2,700 awaiting dismantlement) and 4,300 stockpiled warheads for Russia (with another 3,500 awaiting dismantlement).

Details of the Russian increase and US decrease are yet unclear because neither country reveals the details of the changes at the time of the release of the aggregate data. In about six months, the United States will publish a declassified overview of its forces; Russia does not publish a detailed overview of its strategic forces.

For analysis of the previous New START data, see: /blogs/security/2013/10/newstartsep2013/

Detailed nuclear force overviews are available here: Russia | United States

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Ukraine: The Value of Risk Analysis in Foreseeing Crises

The quantitative risk analysis approach to nuclear deterrence not only allows a more objective estimate of how much risk we face, but also highlights otherwise unforeseen ways to reduce that risk. The current crisis in Ukraine provides a good example.

Last Fall, I met Daniel Altman, a Ph.D. candidate at MIT, who is visiting Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation (CISAC) this academic year. When I told him of my interest in risk analysis of nuclear deterrence, he said that I should pay attention to what might happen in Sevastopol in 2017, something that had been totally off my radar screen.

Sevastopol is home to Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, and along with the rest of the Crimea, was part of Russia until 1954, when Khrushchev arbitrarily “gave” it to the Ukraine. With Russia and Ukraine both parts of the Soviet Union, such a transfer of territory seemed to make no real difference. But, when the USSR broke up in 1991, a good case can be made that the Crimea, with its largely Russian population, should have been returned to Russia.

That did not happen, and with Sevastopol now part of an independent Ukraine, Russia had to negotiate a lease on what, for centuries, had been its own naval base. That lease runs out in 2017. Back in 2008, when she was Prime Minister of a somewhat Russo-phobic Ukrainian government, Yulia Tymoshenko ruled out any extension of the lease. If that were to happen, the ethnic Russians in the Crimea, and especially those in Sevastopol – many of whom depend on the Black Sea Fleet for employment – would likely petition to be reincorporated back into Russia. This would be likely to create an extremely dangerous crisis, since Russia would see this as righting an historical mistake, while the West would see it as Russia stealing part of the Ukraine.

The potential for such a crisis was reduced in 2010, when the more Russian-friendly government of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych extended the lease on Sevastopol for 25 years. But even before the current crisis, there was a risk that a new, Russo-phobic government could come to power and annul the lease extension. Now that Yanukovych has been deposed and anti-Russian Ukrainian elements are part of the interim government, that is an even greater concern.

Given Altman’s alerting me to the risk of “Sevastopol 2017,” I was less surprised, but more concerned than most Americans when the current crisis developed in Ukraine. My concern escalated yesterday (Saturday, March 1, 2014) when Putin requested and received authorization “in connection with the extraordinary situation that has developed in Ukraine … to use the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation on the territory of Ukraine until the social and political situation in that country is normalised.” The resultant actions by Russian troops are seen as an invasion by some elements of the interim Ukrainian government.

Ronald Reagan’s former ambassador to Moscow, Jack Matlock, has a more nuanced take on the situation, starting with a February 8 article which argues that whichever side (Russia or the EU) wins the economic tug of war over Ukraine would lose:

So what if President Yanukovych had signed the EC association agreement? The money available from the IMF would not have staved off bankruptcy very long and would have required unpopular austerity measures … The upshot would be that, most likely, in a year to 18 months, and maybe even sooner, most Ukrainians would blame the EU and the West for their misery.

And if the Russian promise of a loan and cheap gas is renewed to some Ukrainian government, that too would do nothing to promote the reform and modernization the Ukrainian government and economy desperately need. … Ukrainians, even those in the East, would begin to blame Russia for their misery. “If only we had signed that EU association agreement…!”

In sum, I believe it has been a very big strategic mistake – by Russia, by the EU and most of all by the U.S. – to convert Ukrainian political and economic reform into an East-West struggle. … In both the short and long run only an approach that does not appear to threaten Russia is going to work.

Ambassador Matlock posted another article yesterday (Saturday, March 1), which elaborated (emphasis added):

If I were Ukrainian I would echo the immortal words of the late Walt Kelly’s Pogo: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” The fact is, Ukraine is a state but not yet a nation. … The current territory of the Ukrainian state was assembled, not by Ukrainians themselves but by outsiders … To think of it as a traditional or primordial whole is absurd.

… there is no way Ukraine will ever be a prosperous, healthy, or united country unless it has a friendly (or, at the very least, non-antagonistic) relationship with Russia [yet that is the kind of government the West seems intent on installing.] …

So far, Ukrainian nationalists in the west have been willing to concede none of these conditions [needed for stability], and the United States has, by its policies, either encouraged or condoned attitudes and policies that have made them anathema to Moscow. …

Obama’s “warning” to Putin was ill-advised. Whatever slim hope that Moscow might avoid overt military intervention in Ukraine disappeared when Obama in effect threw down a gauntlet and challenged him. This was not just a mistake of political judgment—it was a failure to understand human psychology—unless, of course, he actually wanted a Russian intervention, which is hard for me to believe. …

Ukraine is already shattered de facto, with different groups in command of the various provinces. If there is any hope of putting it together again, there must be cooperation of all parties in forming a coalition at least minimally acceptable to Russia and the Russian-speaking Ukrainian citizens in the East and South.

Ambassador Matlock added another post today (Sunday, March 2) which is also well worth reading, and I’ll end with a few additional thoughts of my own:

Last October and again last November, I quoted Russian international relations expert, Fyodor Lukyanov, as warning that America’s penchant for regime change “will lead to such destabilization that will overwhelm all, including Russia.”

It’s hard for most Americans to see how our helping to overthrow regimes in Iraq, Libya, and the Arab world could produce fears that we also are bent on regime change in a nation as powerful as Russia. But what’s happening in Ukraine brings that fear into sharper focus.

As corrupt and unpopular as Yanukovych was, he was the elected president, and the current interim government can be viewed as the result of mob rule. It doesn’t take 51% of a population to overthrow a government, and some of the groups which overthrew Yanukovych appear to have anti-Russian, anti-Semitic, and possibly even Fascist elements.

It does not seem unreasonable to me for Putin to fear that, if an economic or other crisis were to produce large-scale protests against him, the US would again support regime change. How would we have responded if the Soviet Union had sent support to the Watts rioters in 1965?

It also needs to be recognized that, while Russia’s interests in Ukraine are primarily geopolitical, it also has some legitimate human rights concerns. Under the earlier Ukrainian government, Russian language films imported into Ukraine had to be dubbed into Ukrainian and subtitles added for ethnic Russians. To understand how this felt to them, imagine how we would feel if we were barred by law from watching Hollywood movies in their original English language versions, and instead forced to watch them dubbed into French, with English subtitles.

There is a danger of Russia subjugating Ukraine, but there also is a history of Ukraine subjugating its own Russian minority. A solution is needed which recognizes the legitimate rights of all residents of Ukraine, and right now my nation is not supporting that approach. I hope it will recognize and correct its mistake. That would shorten the suffering of Ukrainian residents of all ethnicities and reduce the risk of a Russian-American crisis – as well as its attendant nuclear risk.

A Credible Radioactive Threat to the Sochi Olympics?

With the Sochi Olympics set to start on February 6th there has been an escalating concern about security threats to the Games. There are hunts for female suicide bombers (“black widows”), video threats from militant groups, etc., all of which have triggered a massive Russian security response, including statements by President Putin insuring the safety of the Games.

Many of the security concerns are raised by the proximity of Sochi to Chechnya and relate to the threats expressed by Chechen leader Doku Umarov who exhorted Islamic militants to disrupt the Olympics.

In the past weeks the region has seen Islamic militants claims that they carried out two recent suicide bombings in Volgorad which tragically killed 34 people and injured scores of others. Volgograd is about 425 miles from Sochi and although the media stresses the proximity it is a considerable distance.

Making the Cut: Reducing the SSBN Force

The Navy plans to buy 12 SSBNs, more than it needs or can afford.

By Hans M. Kristensen

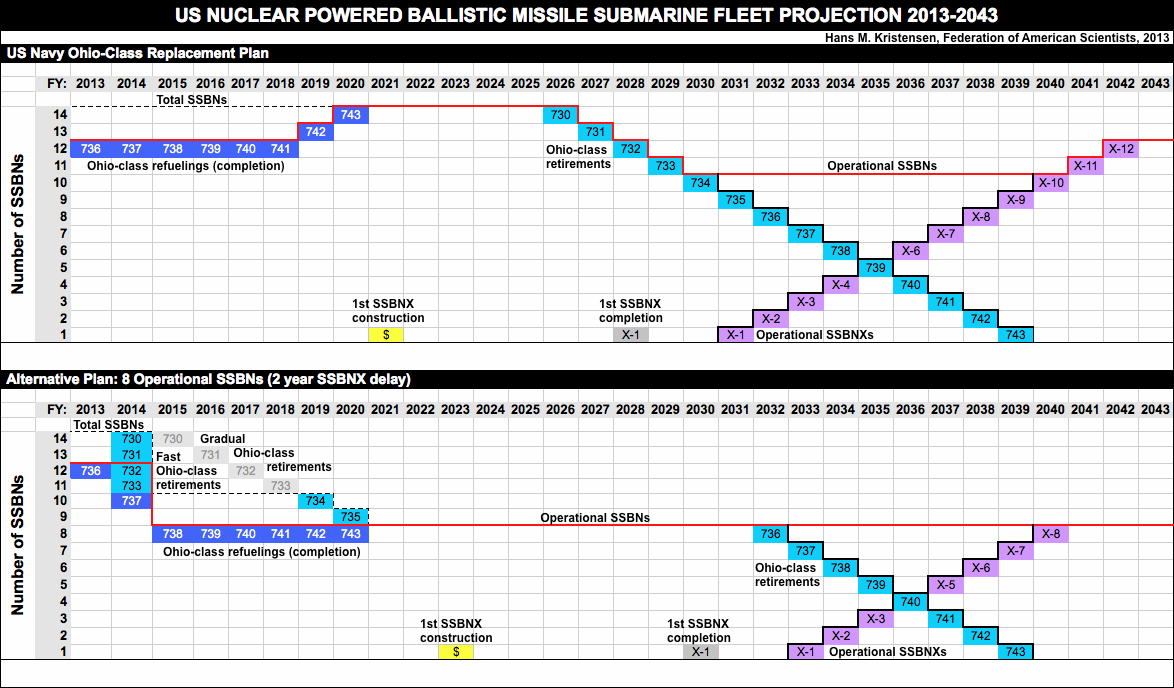

A new Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report – Options For Reducing the Deficit: 2014-2023 – proposes reducing the Navy’s fleet of Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines from the 14 boats today to 8 in 2020. That would save $11 billion in 2015-2023, and another $30 billion during the 2030s from buying four fewer Ohio replacement submarines.

The Navy has already drawn its line in the sand, insisting that the current force level of 14 SSBNs is needed until 2026 and that the next-generation SSBN class must include 12 boats.

But the Navy can’t afford that, nor can the United States, and the Obama administration’s new nuclear weapons employment guidance – issued with STRATCOM’s blessing – indicates that the United States could, in fact, reduce the SSBN fleet to eight boats. Here is how.

New START Treaty Force Level

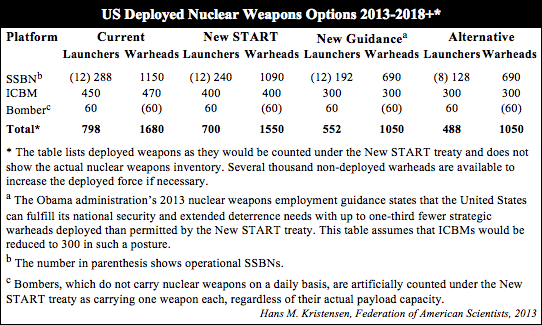

Under the New START treaty the United States plans to deploy 640 ballistic missiles loaded with 1490 warheads (1,550 warheads minus the 60 weapons artificially attributed to bombers that don’t carry nuclear weapons on a daily basis). Of that, the SSBN fleet will account for 240 missiles and 1090 warheads (see table below).

The analysis for the new guidance – formally known as Presidential Policy Decision 24 – determined that the United State could safely reduce its deployed nuclear weapons by up to one-third below the New START level. But even though the current posture therefore is bloated and significantly in excess of what’s needed to ensure the security of the United States and its allies and partners, the military plans to retain the New START force structure until Russia agrees to the reductions in a new treaty.

Yet Russia is already well below the New START treaty force level (-227 launchers and -150 warheads); the United States currently deploys 336 launchers more than Russia (!). Moreover, the Russian missile force is expected to decline even further from 428 to around 400 missiles by the early 2020s – even without a new treaty. Unlike U.S. missiles, however, the Russian missiles don’t have extra warhead spaces; they’re loaded to capacity to keep some degree of treaty parity with the United States.

Making The Cut

The table above includes two future force structure options: a New Guidance option based on the “up to one-third” cut in deployed strategic forces recommended by the Obama administration’s new nuclear weapons employment guidance; and an “Alternative” posture reduced to eight SSBNs as proposed by CBO.

Under the New Guidance posture, the SSBN fleet would carry 690 warheads, a reduction of 400 warheads below what’s planned under the New START treaty. The 192 SLBMs (assuming 16 per next-generation SSBN) would have nearly 850 extra warhead spaces (upload capacity), more than enough to increase the deployed warhead level back to today’s posture if necessary, and more than enough to hedge against a hypothetical failure of the entire ICBM force. In fact, the New Guidance posture would enable the SSBN force to carry almost all the warheads allowed under the New START treaty.

Under the Alternative posture, the SSBN fleet would also carry 690 warheads but there would be 64 fewer SLBMs. Those SLBMs would have “only” 334 extra warhead spaces, but still enough to hedge against a hypothetical failure of the ICBM force. In fact, the SLBMs would have enough capacity to carry almost the entire deployed warhead level recommended by the new employment guidance.

The Navy’s SSBN force structure plan will begin retiring the Ohio-class SSBNs in 2026 at a rate of one per year until the last boat is retired in 2039. The first next-generation ballistic missile submarine (currently known as SSBNX) is scheduled to begin construction in 2021, be completed in 2028, and sail on its first deterrent patrol in 2031. Additional SSBNXs will be added at a rate of one boat per year until the fleet reaches 12 by 2042 (see figure below).

The Navy’s schedule creates three fluctuations in the SSBN fleet. The first occurs in 2019-2020 where the number of operational SSBNs will increase from 12 to 14 as a result of the two newest boats (USS Wyoming (SSBN-742) and USS Louisiana (SSBN-743)) completing their mid-life reactor refueling overhauls. That is in excess of national security needs so at that time the Navy will probably retire the two oldest boats (USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) and USS Alabama (SSBN-731)) eight years early to keep the fleet at 12 operational SSBNs (this doesn’t show in the Navy’s plan).

The second fluctuation in the Navy’s schedule occurs in 2027-2030 when the number of operational SSBNs will drop to 10 as a result of the retirement of the first four Ohio-class SSBNs and the decision in 2012 to delay the first SSBNX by two years. As it turns out, that doesn’t matter because no more than 10 SSBNs are normally deployed anyway.

The third fluctuation in the Navy’s schedule occurs in 2041-2042 when the number of operational SSBNXs increases from 10 to 12 as the last two boats join the fleet. This is an odd development because there obviously is no reason to increase the fleet to 12 SSBNXs in the 2040s if the Navy has been doing just fine with 10 boats in the 2030s. This also suggests that the fleet could in fact be reduced to 12 boats today of which 10 would be operational. To do that the Navy could retire two SSBNs immediately and two more in 2019-2020 when the last refueling overhauls have are completed.

To reduce the SSBN fleet to eight boats as proposed by CBO, the Navy would retire the six oldest Ohio-class SSBNs at a rate of one per year in 2015-2020. At that point the last Ohio-class reactor refueling will have been completed, making all remaining SSBNs operationally available. A quicker schedule would be to retire four SSBNs in 2014 and the next two in 2019-2020. That would bring the fleet to eight operational boats immediately instead of over seven years and allow procurement of the first SSBNX to be delayed another two years (see figure above).

Reducing to eight SSBNs would obviously necessitate changes in the operations of the SSBN force. The Navy’s 12 operational SSBNs conduct 28 deterrent patrols per year, or an average of 2.3 patrols per submarine. The annual number of patrols has decline significantly over the past decade, indicating that the Navy is operating more SSBNs than it needs. Each patrol lasts on average 70 days and occasionally over 100 days. To retain the current patrol level with only eight SSBNs, each boat would have to conduct 3.5 patrols per year. Between 1988 and 2005, each SSBN did conduct that many patrols per year, so it is technically possible.

Moreover, of the 10 or so SSBNs that are at sea at any given time, about half (4-5) are thought to be on “hard alert” in pre-designated patrol areas, within required range of their targets, and ready to launch their missiles 15 minutes after receiving a launch order. A fleet of eight operational SSBNs could probably maintain six boats at sea at any given time, of which perhaps 3-4 boats could be on alert.

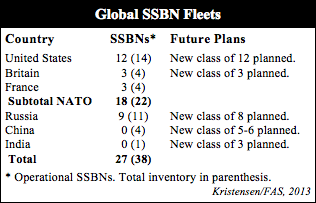

Finally, reducing the SSBN fleet to eight boats seems reasonable because no other country currently plans to operate more than eight SSBNs (see table). The United States today operates more SSBNs than any other country. And NATO’s three nuclear weapon states currently operate a total of 22 SSBNs, twice as many as Russia. China and India are also building SSBNs but they’re far less capable and not yet operational.

Finally, reducing the SSBN fleet to eight boats seems reasonable because no other country currently plans to operate more than eight SSBNs (see table). The United States today operates more SSBNs than any other country. And NATO’s three nuclear weapon states currently operate a total of 22 SSBNs, twice as many as Russia. China and India are also building SSBNs but they’re far less capable and not yet operational.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Navy could and should reduce its SSBN fleet from 14 to eight boats as proposed by CBO. Doing so would shed excess capacity, help prepare the nuclear force level recommended by the new nuclear weapons employment policy, better match the force levels of other countries, and save billions of dollars. There are several reasons why this is possible:

First, the decision to go to 10 operational SSBNs in the 2030s suggests that the Navy is currently operating too many SSBNs and could immediately retire the two oldest Ohio-class SSBNs.

Second, the decision to build a new SSBN fleet with 144 fewer SLBM launch tubes than the current SSBN fleet is a blatant admission that the current force is significantly in excess of national security needs.

Third, the acknowledgement in November 2011 by former STRATCOM commander Gen. Robert Kehler that the reduction of 144 missile tubes “did not assume any specific changes to targeting or employment guidance” suggests there’s a significant over-capacity in the current SSBN fleet.

Fourth, it is highly unlikely that presidential nuclear guidance three decades from now – when the planned 12-boat SSBNX fleet becomes operational – will not have further reduced the nuclear arsenal and operational requirement significantly.

Fifth, reducing the SSBN fleet now would allow significant additional cost savings: $11 billion in 2015-2023 (and $30 billion more in the 2030s) from reduced ship building according to CBO; completing the W76-1 production earlier with 500 fewer warheads; $7 billion from reducing production of the life-extended Trident missile (D5LE) by 112 missiles; operational savings from retiring six Ohio-class SSBNs early; and by reducing the warhead production capacity requirement for the expensive Uranium Production Facility and Chemistry and Metallurgy Research facilities.

Sixth, reducing the SSBN fleet would help reduce the growing disparity between U.S. and Russian strategic missiles. This destabilizing trend keeps Russia in a worst-case planning mindset suspicious of U.S. intensions, drives large warhead loadings on each Russian missile, and wastes billions of dollars and rubles on maintaining larger-than-needed strategic nuclear force postures.

Change is always hard, but a reduction of the SSBN fleet would be a win for all.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows Russia Reducing, US Increasing Nuclear Forces

By Hans M. Kristensen

While arms control opponents in Congress have been busy criticizing the Obama administration’s proposal to reduce nuclear forces further, the latest data from the New START Treaty shows that Russia has reduced its deployed strategic nuclear forces while the United States has increased its force over the past six months.

Yes, you read that right. Over the past six months, the U.S. deployed strategic nuclear forces counted under the New START Treaty have increased by 34 warheads and 17 launchers.

It is the first time since the treaty entered into effect in February 2011 that the United States has been increasing its deployed forces during a six-month counting period.

We will have to wait a few months for the full aggregate data set to be declassified to see the details of what has happened. But it probably reflects fluctuations mainly in the number of missiles onboard ballistic missile submarines at the time of the count.

Slooow Implementation

The increase in counted deployed forces does not mean that the United States has begun to build up is nuclear forces; it’s an anomaly. But it helps illustrate how slow the U.S. implementation of the treaty has been so far.

Two and a half years into the New START Treaty, the United States has still not begun reducing its operational nuclear forces. Instead, it has worked on reducing so-called phantom weapons that have been retired from the nuclear mission but are still counted under the treaty.

For reasons that are unclear (but probably have to do with opposition in Congress), the administration has chosen to reduce its operational nuclear forces later rather than sooner. Not until 2015-2016 is the navy scheduled to reduce the number of missiles on its submarines. The air force still hasn’t been told where and when to reduce the ICBM force or which of its B-52 bombers will be denuclearized.

Moreover, even though the navy has already decided to reduce the missile tubes on its submarine force by more than 30 percent from 280 in 2016 to 192 on its next-generation ballistic missile submarine, it plans to continue to operate the larger force into the 2030s even though it is in excess of targeting and employment guidance.

Destabilizing Disparity

But even when the reductions finally get underway, the New START Treaty data illustrates an enduring problem: the growing disparity between U.S. and Russian strategic nuclear forces. The United States now is counted with 336 deployed nuclear launchers more than Russia.

Russia is already 227 deployed missiles and bombers below the 700 limit established by the treaty for 2018, and might well drop by another 40 by then to about 430 deployed strategic launchers. The United States plans to keep the full 700 launchers.

Put in another way: unless the United States significantly reduces its ICBM force beyond the 400 or so planned under the New START Treaty, and unless Russia significantly increases deployment of new missiles beyond what it is currently doing, the United States could end up having nearly as many launchers in the ICBM-leg of its Triad as Russia will have in its entire Triad.

Strange Bedfellows

For most people this might not matter much and even sound a little Cold War’ish. But for military planners who have to entertain potential worst-case threat scenarios, the growing missile-warhead disparity between the two countries is of increasing concern.

For the rest of us, it should be of concern too, because the disparity can complicate arms reductions and be used to justify retaining excessively large expensive nuclear force structures.

For the Russian military-industrial complex, the disparity is good for business. It helps them argue for budgets and missiles to keep up with the United States. But since Russia is retiring its old Soviet-era missiles and can’t build enough new missiles to keep some degree of parity with the United States, it instead maximizes the number of warheads it deploys on each new missile.

As a result, the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces has begun a program to deploy modified SS-27 ICBMs with multiple warheads (the modified SS-27 is known in Russia as RS-24 or Yars) with six missile divisions over the next decade and a half (more about that in a later blog). And a new “heavy” ICBM with up to ten warheads per missile is said to be under development.

So in a truly bizarre twist, U.S. lawmakers and others opposing additional nuclear reductions by the Obama administration could end up help providing the excuse for the very Russia nuclear modernization they warn against.

Granted, the Putin government may not be the easiest to deal with these days. But that only makes it more important to continue with initiatives that can take some of the wind out of the Russian military’s modernization plans. Slow implementation of the New START Treaty and retention of a large nuclear force structure certainly won’t help.

See also blog on previous New START data.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

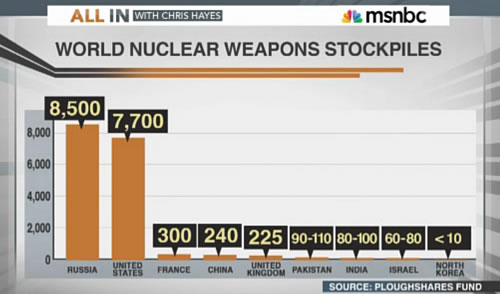

MSNBC On Nuclear Weapons Reduction Efforts

By Hans M. Kristensen

MSNBC used FAS data on the world nuke arsenals in an interview with Ploughshares Fund president Joe Cirincione about how deteriorating US-Russian relations might affect efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals.

The updated weapons estimates on the FAS web site are here.

Detailed profiles of each nuclear weapon state are published as Nuclear Notebooks in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Support our work to produce high-quality estimates of world nuclear forces: Donate here.