Enhancing US Power Grid by using AI to Accelerate Permitting

The increased demand for power in the United States is driven by new technologies such as artificial intelligence, data analytics, and other computationally intensive activities that utilize ever faster and power-hungry processors. The federal government’s desire to reshore critical manufacturing industries and shift the economy from service to goods production will, if successful, drive energy demands even higher.

Many of the projects that would deliver the energy to meet rising demand are in the interconnection queue, waiting to be built. There is more power in the queue than on the grid today. The average wait time in the interconnection queue is five years and growing, primarily due to permitting timelines. In addition, many projects are cancelled due to the prohibitive cost of interconnection.

We have identified six opportunities where Artificial Intelligence (AI) has the potential to speed the permitting process.

- AI can be used to speed decision-making by regulators through rapidly analyzing environmental regulations and past decisions.

- AI can be used to identify generation sites that are more likely to receive permits.

- AI can be used to create a database of state and federal regulations to bring all requirements in one place.

- AI can be used in conjunction with the database of state regulations to automate the application process and create visibility of permit status for stakeholders.

- AI can be used to automate and accelerate interconnection studies.

- AI can be used to develop a set of model regulations for local jurisdictions to adapt and adopt.

Challenge and Opportunity

There are currently over 11,000 power generation and consumption projects in the interconnection queue, waiting to connect to the United States power grid. As a result, on average, projects must wait five years for approval, up from three years in 2010.

Historically, a large percentage of projects in the queue, averaging approximately 70%, have been withdrawn due to a variety of factors, including economic viability and permitting challenges. About one-third of wind and solar applications submitted from 2019 to 2024 were cancelled, and about half of these applications faced delays of 6 months or more. For example, the Calico Solar Project in the California Mojave Desert, with a capacity of 850 megawatts, was cancelled due to lengthy multi-year permitting and re-approvals for design changes. Increasing queue wait time is likely to increase the number of projects cancelled and delay those that are viable.

The U.S. grid added 20.2 gigawatts of utility-scale generating capacity in the first half of 2024, a 21% increase over the first half of 2023. However, this is still less power than is likely to be needed to meet increasing power demands in the U.S. Nor does it account for the retirement of generation capacity, which was 5.1 gigawatts in the first half of 2024. In addition to replacing aging energy infrastructure as it is taken offline, this new power is critically needed to address rising energy demands in the U.S. Data centers alone are increasing power usage dramatically, from 1.9% of U.S. energy consumption in 2018 to 4.4% in 2023, and with an expected consumption of at least 6.7% in 2028.

If we want to achieve the Administration’s vision of restoring U.S. domestic manufacturing capacity, a great deal of generation capacity not currently forecast will also need to be added to the grid very rapidly, far faster than indicated by the current pace of interconnections. The primary challenge that slows most power from getting onto the grid is permitting. A secondary challenge that frequently causes projects to be delayed or cancelled is interconnection costs.

Projects frequently face significant permitting challenges. Projects not only need to obtain permits to operate the generation site but must also obtain permits to move power to the point where it connects to the existing grid. Geographically remote projects may require new transmission lines that cover many miles and cross multiple jurisdictions. Even projects relatively close to the existing grid may require multiple permits to connect to the grid.

In addition, poor site selection has resulted in the cancellation of several high-profile renewable installation projects. The Battle Born Solar Project, valued at $1 billion with a 850 megawatt capacity, was cancelled after community concern that the solar farm would impact tourism and archaeological sites in the Mormon Mesa in Nevada. Another project, a 150 megawatt solar facility proposed for Culpeper County, Virginia, was denied permits for interfering with the historic site of a Civil War battle. Similarly, a geothermal plant in Nevada had to be scaled back to less than a third of its original plan after it was found to be in the only known habitat of the endangered Dixie Valley toad. While community outrage over renewable energy installations is not always avoidable, mostly due to complaints about construction impacts and misinformation, better site selection could save developers time and money by avoiding locations that encroach on historical sites, local attractions, or endangered species‘ habitats.

Projects have also historically faced cost challenges as utilities and grid operators could charge the full cost of new operating capacity to each project, even when several pending projects could utilize the same new operating assets. On July 28, 2023, FERC issued a final rule with a compliance date of March 21, 2024, that requires transmission providers to consider all projects in the queue and determine how operating assets would be shared when calculating the cost of connecting a project to the grid. However, the process for calculating costs can be cumbersome when many projects are involved.

On April 15th, 2025, the Trump Administration issued a Presidential Memorandum titled “Updating Permitting Technology for the 21st Century.” This memo directs executive departments and agencies to take full advantage of technology for environmental review and permitting processes and creates a permitting innovation center. While it is unclear how much authority the PIC will have, it demonstrates the Administration’s focus in this area and may serve as a change agent in the future. There is an opportunity to use AI to improve both the speed and the cost of connecting new projects to the grid. Below are recommendations to capitalize on this opportunity.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. Funding for PNNL to expand the PolicyAI NEPA model to streamline environmental permitting processes beyond the federal level.

In 2023, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) was tasked by DOE with developing a PermitAI prototype to help regulators understand the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) regulations and speed up project environmental reviews. PNNL data scientists created an AI-searchable database of federal impact environmental statements, composed primarily of information that was not readily available to regulators before. The database contains textual data extracted from documents across 2,917 different projects stored as 3.6 million tokens from the GPT-2 tokenizer. Tokens are the units in which text is broken down for natural language processing AI models. The entire dataset is currently publicly available via HuggingFace. The database is then used for generative-AI searching that can quickly find documents and summarize relevant results as a Large Language Model (LLM). While the development of this database is still preliminary and efficiency metrics have not yet been published, based on complaints from those involved in permitting about the complexity of the process and the lack of guidelines, this approach should be a model for tools that could be developed and provided to state and local regulators to assist with permitting reviews.

In 2021, PNNL created a similar process, without using AI, for NEPA permitting for small-to medium-sized nuclear reactors, which simplified the process and reduced the environmental review time from three to six years to between six and twenty-four months. Using AI has the potential to reduce the process exponentially for renewables permitting. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) has also studied using LLMs to expedite the processing of policy data from legal documents and found the results to support the expansion of LLMs for policy database analysis, primarily when compared to the current use of manual effort.

State and local jurisdictions can use the “Updating Permitting Technology” Presidential Memorandum as guidance to support the intersection between state and local permitting efforts. The PNNL database of federal NEPA materials, trained on past NEPA cases, would be provided by PNNL to state jurisdictions as a service, through a process similar to that used by EPA to ensure that state jurisdictions do not need to independently develop data collection solutions. Ideally, the initial data analysis model would be trained to be specific to each participating state and continually updated with new material to create a seamless regulatory experience.

Since PNNL has already built a NEPA model and this work is being expanded to a multi-lab effort that includes NREL, Argonne and others The House Energy and Water development committee could appropriate additional funding to the Office of Policy (OP) or EERE (Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy) to enable the labs to expand the model and make it available to state and local regulatory agencies to integrate it into their permitting processes. States could develop models specific to their ordinances with the backbone of PNNL’s PermitAI. This effort could be expedited through engagement with the Environmental Council of the States (ECOS).

A shared database of NEPA information would reduce time spent reviewing backlogs of data from environmental review documents. State and local jurisdictions would more efficiently identify relevant information and precedent, and speed decision-making while reducing costs. An LLM tool also has the benefit of answering specific questions asked by the user. An example would be answering a question about issues that have arisen for similar projects in the same area.

Recommendation 2. Appropriate funding to expand AI site selection tools and support state and local pilots to improve permitting outcomes and reduce project cancellations.

AI could be used to identify sites that are suitable for energy generation, with different models eventually trained for utility-scale solar siting, onshore and offshore wind siting, and geothermal power plant siting. Key concerns affecting the permitting process include the loss of arable land, impacts on wildlife, and community responses, like opposition based on land use disagreements. Better site selection identifies these issues before they appear during the permitting process.

AI can access data from a range of sources, including satellite imagery from Google Earth, commercially available lidar studies, and local media screening to identify locations with the least number of potential barriers or identify and mitigate barriers for sites that have been selected. Unlike action one, which involves answering questions by pulling from large databases using LLMs, this would primarily utilize machine learning algorithms that process past and current data to identify patterns and predict outcomes, like energy generation potential. Examples of datasets these tools can use are the free, publicly available products created by the Innovative Data Energy Applications (IDEA) group in NREL’s Strategic Energy Analysis Center (SEAC), including the national solar radiation database and the wind resource database. The national solar radiation database visualizes the amount of solar energy potential at a given time and predicts future availability of solar energy for a given location in the dataset, which covers the entirety of the United States.

The wind resource database is a collection of modeled wind resource estimates for locations within the United States. In addition, Argonne National Lab has developed the GEM tool to support the NEPA reviews for transmission projects. A few start-ups have synthesized a variety of datasets like these and created their databases for information like terrain and slope to create site-selection decision-making tools. AI analysis of local news and landmarks important to local communities to identify locations that are likely to oppose renewable installations is particularly important since community opposition is often what kills renewable generation projects that have made it into the permitting process.

The House Committee for Energy and Water Development could appropriate funds to DOE’s Grid Deployment Office which could collaborate with EERE, FECM (Fossil Energy and Carbon Management), NE (Nuclear Energy) and OE (Office of Electricity) to further expand the technology specific models as well as to expand Argonne’s GEM tool. GDO could also provide grant funding to state and local government permitting authorities to pilot AI-powered site selection tools created by start-ups or other organizations. Local jurisdictions, in turn, could encourage use by developers.

Better site selection would speed permitting processes and reduce the number of cancelled projects, as well as wasted time and money by developers.

Recommendation 3. Funding for DOE labs to develop an AI-based permitting database, starting with a state-level pilot, to streamline permit site identification and application for large-scale energy projects.

Use AI to identify all of the non-environmental federal, state, and local permits required for generation projects. A pilot project, focused on one generation type, such as solar, should be launched in a state that is positioned for central coordination. New York may be the best candidate, as the Office of Renewable Energy Siting and Electric Transmission has exclusive jurisdiction over on-shore renewable energy projects of at least 25 megawatts.

A second option could be Illinois, which has statewide standards for utility-scale solar and wind facilities where local governments cannot adopt more restrictive ordinances. This would require the development of a database of regulations and the ability to query that database to provide a detailed list of required permits for each project by jurisdiction, the relevant application process, and forms. The House Energy and Water Development Committee could direct funds to EERE to support PNNL, NREL, Argonne, and other DOE labs to develop this database. Ideally, this tool would be integrated with tools developed by local jurisdictions to automate their individual permitting process.

State-level regulatory coordination would speed the approval of projects contained within a single state, as well as improve coordination between states.

Recommendation 4. Appropriate funds for DOE to develop a state-level AI permitting application to streamline renewable energy permit approvals and improve transparency.

Use AI as a tool to complete the permitting process. While it would be nearly impossible to create a national permitting tool, it would be realistic to create a tool that could be used to manage developers’ permitting processes at the state level.

NREL developed a permitting tool with funding from the DOE Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO) for residential rooftop solar permitting. The tool, SolarAPP+, automates plan review, permit approval, and project tracking. As of the end of 2023, it had saved more than 33,000 hours of permitting staff time for more than 32,800 projects. However, permitting for rooftop solar is less complex than permitting for utility-scale solar sites or wind farms because of less need for environmental reviews, wildlife endangerment reviews, or community feedback. Using the AI frameworks developed by PNNL mentioned in recommendation one and leveraging the development work completed by NREL could create tools similar to SolarAPP+ for large-scale renewable installations and have similar results in projects approved and time saved. An application that may meet this need is currently under development at NREL.

The House Energy and Water Development Committee should appropriate funds for DOE to create an application through PNNL and NREL that would utilize the NREL SolarAPP+ framework that could be implemented by states to streamline the permitting application process. This would be especially helpful for complex projects that cross multiple jurisdictions. In addition, Congress, through appropriation by the House Energy and Water Development Committee to DOE’s Grid Deployment Office, could establish a grant program to support state and local level implementation of this permitting tool. This tool could include a dashboard to improve permitting transparency, one of the items required by the Presidential Memorandum on Updating Permitting Technology.

Developers are frequently unclear about what permits are required, especially for complex multi-jurisdiction projects. The AI tool would reduce the time a developer spends identifying permits and would support smaller developers who don’t have permitting consultants or prior experience. An integrated electronic permitting solution would reduce the complexity of applying for and approving permits. With a state-wide system, state and local regulators would only need to add their requirements and location-specific requirements and forms into a state-maintained system. Finally, an integrated system with a dashboard could increase status visibility and help resolve issues more quickly. These tools together would allow developers to make realistic budgets and time frames for projects to allocate resources and prioritize projects that have the greatest chance of being approved.

Recommendation 5. Direct FERC to require RTOs to evaluate and possibly implement AI tools to automate interconnection analysis processes.

Use AI tools to reduce the complexity of publishing and analyzing the mandated maps and assigning costs to projects. While FERC has mandated that grid operators consider all projects coming onto the grid when setting interconnection pricing, as well as considering project readiness rather than time in queue for project completion, the requirements are complex to implement.

A number of private sector companies have begun developing tools to model interconnections. Pearl Street has used its model to reproduce a complex and lengthy interconnection cluster study in ten days, and PJM recently announced a collaboration with Google to develop an analysis capability. Given the private sector efforts in this space, the public interest would be best served by FERC requiring RTOs to evaluate and implement, if suitable, an automated tool to speed their analysis process.

Automating parts of interconnection studies would allow developers to quickly understand the real cost of a new generation project, allowing them to quickly evaluate feasibility. It would create more cost certainty for projects and would also help identify locations where planned projects have the potential to reduce interconnection costs, attracting still more projects to share new interconnections. Conversely, the capability would also quickly identify when new projects in an area would exceed expected grid capacity and increase the costs for all projects. Ultimately, the automation would lead to more capacity on the grid faster and at a lower cost as developers optimize their investments.

Recommendation 6. Provide funding to DOE to extend the use of NREL’s AI-compiled permitting data to develop and model local regulations. The results could be used to promote standardization through national stakeholder groups.

As noted earlier, one of the biggest challenges in permitting is the complexity of varying and sometimes conflicting local regulations that a project must comply with. Several years ago, NREL, in support of the DOE Office of Policy, spent 1500 staff hours to manually compile what was believed to be a complete list of local energy permitting ordinances across the country. In 2024, NREL used an LLM to compile the same information with a 90% success rate in a fraction of the time.

The House Energy and Water Development Committee should direct DOE to fund the continued development of the NREL permitting database and evaluate that information with an LLM to develop a set of model regulations that could be promoted to encourage standardization. Adoption of those regulations could be encouraged by policymakers and external organizations through engagement with the National Governors Association, the National Association of Counties, the United States Conference of Mayors, and other relevant stakeholders.

Local jurisdictions often adopt regulations based on a limited understanding of best practices and appropriate standards. A set of model regulations would guide local jurisdictions and reduce complexity for developers.

Conclusion

As demand on the electrical grid grows, the need to speed up the availability of new generation capacity on the grid becomes increasingly urgent. The deployment of new generation capacity is slowed by challenges related to site selection, environmental reviews, permitting, and interconnection costs and wait times. While much of the increasing demand for energy in the United States can be attributed to AI, it can also be a powerful tool to help the nation meet that demand.

The six recommendations for AI to speed up the process of bringing new power to the grid that have been identified in this memo address all of those concerns. AI can be used to assist with site selection, analyze environmental regulations, help both regulators and the regulated community understand requirements, develop better regulations, streamline permitting processes, and reduce the time required for interconnection studies.

This memo is part of our AI & Energy Policy Sprint, a policy project to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Read more about the Policy Sprint and check out the other memos here.

The combined generating capacity of the projects awaiting approval is about 1,900 gigawatts, excluding ERCOT and NYISO which do not report this data. In comparison, the generating capacity of the U.S. grid as of Q4 2023 was 1,189 gigawatts. Even if the current high cancellation rate of 70% is maintained, the queue will yield an approximately 50% increase in the amount of power available on the grid through a $600B investment in US energy infrastructure.

FERC’s five-year growth forecast through 2029 predicts an increased demand for 128 gigawatts of power. In that context, the net addition of 15.1 gigawatts of power in the first half of 2024 suggests an increase of 150 gigawatts of power and little excess capacity over the five-year horizon. This forecast is predicated on the assumption that the power added to the grid does not decline, retirements do not increase, and the load forecast does not increase. All these estimates are being applied to a system where supply and demand are already so closely matched that FERC predicted supply shortages in several regions in the summer of 2024.

Construction delays and cost overruns can be an issue, but this is more frequently a factor in large projects such as nuclear and large oil and gas facilities, and is rarely a factor for wind and solar which are factory built and modular.

While the current administration has declared a National Energy Emergency to expedite approvals for energy projects, the order excludes wind, solar, and batteries, which make up 90% of the power presently in the interconnection queue as well as mirroring the mix of capacity recently added to the grid. Therefore, the expedited permitting processes required by the administration only applies to 10% of the queue, composed of 7% natural gas and 3% that includes nuclear, oil, coal, hydrogen, and pumped hydro. Since solar, wind, and batteries are unlikely to be granted similar permitting relief, and relying on as-yet unplanned fossil fuel projects to bring more energy to the grid is not realistic, other methods must be undertaken to speed new power to the grid.

Federation of American Scientists and Environmental Policy Innovation Center Unveil Permitting Tech and Talent Policy Recommendations to Support Deployment of Crucial Energy, Environmental, and Infrastructure Projects

Technology and talent recommendations will speed permitting required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

Washington, D.C. – February 5, 2025 – To facilitate faster implementation on our Nation’s biggest projects, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), a non-partisan, nonprofit science think tank dedicated to developing evidence-based policies to address national threats, today released permitting policy recommendations to improve talent and technology in the federal permitting process. These recommendations will address the sometimes years-long bottlenecks that prevent implementation of crucial projects, from energy to transportation.

“Inefficient permitting processes continue to impede accelerated deployment of energy, infrastructure, and restoration projects in the U.S ,” says Daniel Correa, CEO of FAS. “Even as so much of the debate in Washington, DC focuses on legislative fixes, our findings suggest that it all comes down to getting implementation right. And getting these details right is what will help ensure that speed and efficiency do not come at the costs of core ecosystem services and environmental benefits.” Though permitting regulations and processes are currently in flux, government entities should strategically leverage talent and technology to build and implement a more efficient, effective process.

Modernized Technology and Highly Skilled Talent

For the last 18 months, FAS has been studying how agencies use technology and talent in permitting processes required by the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). For the talent portion of the project, FAS partnered with the Permitting Council to understand bottlenecks to federal hiring for permitting roles and recommend solutions.

“We identified a series of challenges hindering the development of talent capacity and stymieing the hiring process, synthesized insights from civil servants, and are making recommendations to address these bottlenecks,” says Erica Goldman, Director of the Day One Project and Policy Entrepreneurship at FAS.

She continues: “Through our technology work in partnership with the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC), we’ve highlighted pockets of innovation, talked to stakeholders working to streamline NEPA processes, and made evidence-based recommendations for improved technology practices in government. This work has substantiated our hypothesis that technology has untapped potential to improve the efficiency and utility of NEPA processes and data.”

Parallel Permitting Challenges

Great technology doesn’t build itself. Solutions to the technology and talent challenges that plague permitting will fall short of their potential if they are not developed together. Great technology products come from great talent. In turn, great talent can be unleashed with better technology.

“In our work, we noticed that technology and talent initiatives face parallel challenges in several respects. For example, federal permitting is accomplished through disparate teams across agencies’ regions, offices, and bureaus with disparate staffing models and occupations; in the same way, permitting technologies are diffuse and unique to specific agency or sub-agency teams and permitting goals instead of consistent and shared across permitting teams,” says Peter Bonner, Senior Fellow at FAS, who was involved with the research.

He continues: “As the federal government wrestles with improving the efficiency of permitting processes, it is imperative that technology and talent teams work together. Recognizing the intrinsic link between talent and technology and addressing shared challenges collaboratively is essential to building a more efficient permitting system.”

“At the end of the day, we think using technology, including AI, can eliminate more than 50% of the time it takes to complete every permit,” says Tim Male, Executive Director of EPIC, “yet that tech won’t work if you don’t have the right people in and out of government who understand and can leverage it – our recommendations are about the people, policy and tech solutions to accelerate permitting.”

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

ABOUT ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY INNOVATION CENTER

The Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) advances policies that deliver spectacular improvement in the speed and scale of environmental progress. A nonprofit start-up founded in 2017, EPIC is committed to finding and highlighting the best approaches to scaling up results quickly across drinking water, biodiversity, permitting, environmental markets, and the use of data and technology to produce positive environmental and public health outcomes. More about our EPIC work at policyinnovation.org.

Permitting Reform Resources

A full list of publications from FAS’s 18 month research workstream, including findings, recommendations, and case studies, can be found on FAS’s website.

Solutions for an Efficient and Effective Federal Permitting Workforce

The United States faces urgent challenges related to aging infrastructure, vulnerable energy systems, and economic competitiveness. Improving American competitiveness, security, and prosperity depends on private and public stakeholders’ ability to responsibly site, build, and deploy critical energy and infrastructure. Unfortunately, these projects face one common bottleneck: permitting.

Permits and authorizations are required for the use of land and other resources under a series of laws, such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. However, recent court rulings and the Trump Administration’s executive actions have brought uncertainty and promise major disruption to the status quo. The Executive Order (EO) on Unleashing American Energy mandates guidance to agencies on permitting processes be expedited and simplified within 30 days, requires agencies prioritize efficiency and certainty over any other objectives, and revokes the Council of Environmental Quality’s (CEQ) authority to issue binding NEPA regulations. While these changes aim to advance the speed, efficiency, and certainty of permitting, the impact will ultimately depend on implementation by the permitting workforce.

Unfortunately, the permitting workforce is unprepared to swiftly implement changes following shifts in environmental policy and regulations. Teams responsible for permitting have historically been understaffed, overworked, and unable to complete their project backlogs, while demands for permits have increased significantly in recent years. Building workforce capacity is critical for efficient and effective federal permitting.

Project Overview

Our team at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has spent 18 months studying and working to build government capacity for permitting talent. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided resources to expand the federal permitting workforce, and we partnered with the Permitting Council, which serves as a central body to improve the transparency, predictability, and accountability of the federal environmental review and authorization process, to gain a cross-agency understanding of the hiring challenges experienced in permitting agencies and prioritize key challenges to address. Through two co-hosted webinars for hiring managers, HR specialists, HR leaders, and program leaders within permitting agencies, we shared tactical solutions to improve the hiring process.

We complemented this understanding with voices from agencies (i.e., hiring managers, HR specialists, HR teams, and leaders) by conducting interviews to identify new issues, best practices, and successful strategies for building talent capacity. With this understanding, we developed long-term solutions to build a sustainable, federal permitting workforce for the future. While many of our recommendations are focused on permitting talent specifically, our work naturally uncovered challenges within the broader federal talent ecosystem. As such, we’ve included recommendations to advance federal talent systems and improve federal hiring.

Problem

Building permitting talent capacity across the federal government is not an easy endeavor. There are many stakeholders involved across different agencies with varying levels of influence who need to play a role: the Permitting Council staff, the Permitting Council members-represented by Deputy Secretaries (Deputy Secretaries) of permitting agencies, the Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers (CERPOs) in each agency, the Office of Personnel and Management (OPM), the Chief Human Capital Officer (CHCO) in each permitting agency, agency HR teams, agency permitting teams, hiring managers, and HR specialists. Permitting teams and roles are widely dispersed across agencies, regions, states, and programs. The role each agency plays in permitting varies based on their mission and responsibilities, and there are many silos within the broader ecosystem. Few have a holistic view of permitting activities and the permitting workforce across the federal government.

With this complex network of actors, one challenge that arises is a lack of standardization and consistency in both roles and teams across agencies. If agencies are looking to fill specialized roles unique to one permitting need, it means that there will be less opportunity for collaboration and for building efficiencies across the ecosystem. The federal hiring process is challenging, and there are many known bottlenecks that cause delays. If agencies don’t leverage opportunities to work together, these bottlenecks will multiply, impacting staff who need to hire and especially permitting and/or HR teams who are understaffed, which is not uncommon. Additionally, building applicant pools to have access to highly qualified candidates is time consuming and not scalable without more consistency.

Tracking workforce metrics and hiring progress is critical to informing these talent decisions. Yet, the tools available today are insufficient for understanding and identifying gaps in the federal permitting workforce. The uncertainty of long-term, sustainable funding for permitting talent only adds more complexity into these talent decisions. While there are many challenges, we have identified solutions that stakeholders within this ecosystem can take to build the permitting workforce for the future.

There are six key recommendations for addressing permitting workforce capacity outlined in the table below. Each is described in detail with corresponding actions in the Solutions section that follows. Our recommendations are for the Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress.

Solutions

The six solutions described below include an explanation of the problem and key actions our signal stakeholders (Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, and Congress) can take to build permitting workforce capacity. The table in the appendix specifies the stakeholders responsible for each recommendation.

Enhance the Permitting Council’s Authority to Improve Permitting Processes and Workforce Collaboration

Permitting process, performance, and talent management cut across agencies and their bureaus—but their work is often disaggregated by agency and sub-agency, leading to inefficient and unnecessarily discrete practices. While the Permitting Council plays a critical coordinating role, it lacks the authority and accountability to direct and guide better permitting outcomes and staffing. There is no central authority for influencing and mandating permitting performance. Agency-level CERPOs vary widely in their authority, whereas the Permitting Council is uniquely positioned for this role. Choosing to overlook this entity will lead to another interagency workaround. Congress needs to give the Permitting Council staff greater authority to improve permitting processes and workforce collaboration.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Improved Performance: Enhance provisions in FAST-41 and IRA by passing legislation that empowers the Permitting Council staff to create and enforce consistent performance criteria for permitting outcomes, permitting process metrics, permitting talent acquisition, talent management, and permitting teams KPIs.

- Enhance Permitting Council Authority for Interagency Coordination: Empower the Permitting Council staff to manage interagency coordination and collaboration for defining permitting best practices, establishing frameworks for permitting, and reinforcing those frameworks across agencies. Clarify the roles and responsibilities between Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ).

- Assign Responsibility for Tracking Changes and Providing Guidance for Permitting Practices: Assign the Permitting Council staff in coordination with OMB responsibility for tracking changes and providing guidance on permitting practices in response to recent and ongoing court rulings that change how permitting outcomes are determined (e.g., Loper Bright/Chevron Deference, CEQ policies, etc.).

- Provide Permitting Council staff with Consistent Funding: Either renew components of IRA and/or IIJA funding that enables the Council to invest in agency technologies, hiring, and workforce development, or provide consistent appropriations for this.

- Enhance CERPO Authority and Position CERPOs for Agency-Wide and Cross-Agency Permitting Actions: Expand CERPO authority beyond the FAST-41 Act to include all permitting work within their agency. Through legislation, policy, and agency-level reporting relationships (e.g., CERPO roles assigned to the Secretary’s office), provide CERPOs with clear authority and accountability for permitting performance.

Build Efficient Permitting Teams and Standardize Roles

In our research, we interviewed one program manager who restructured their team to drive efficiency and support continuous improvement. However, this is not common. Rather, there is a lack of standardization in roles engaged in permitting teams within and across agencies, which hinders collaboration and prevents efficiencies. This is likely driven by the different roles played by agencies in permitting processes. These variances are in opposition to shared certifications and standardized job descriptions, complicate workforce planning, hinder staff training and development, and impact report consistency. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, OMB, and the CHCO Council should improve the performance and consistency of permitting processes by establishing standards in permitting team roles and configurations to support cross-agency collaboration and drive continuous improvements.

- Characterize Types of Permitting Processes: Permitting Council staff should work with Deputy Secretaries, CERPOs, and Permitting Program Team leaders to categorize types of permitting processes based on project “footprint”, complexity, regulatory reach (i.e., regulations activated), populations affected and other criteria. Identify the range of team configurations in use for the categories of processes.

- Map Agency Permitting Roles: Permitting Council staff should map and clarify the roles played by each agency in permitting processes (e.g., sponsoring agency, contributing agency) to provide a foundation for understanding the types of teams employed to execute permitting processes.

- Research and Analyze Agency Permitting Staffing: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with OMB to conduct or refine a data call on permitting staffing. Analyze the data to compare the roles and team structures that exist between and across agencies. Conduct focus groups with cross agency teams to identify consistent talent needs, team functions, and opportunities for standardization.

- Develop Permitting Team Case Studies: Permitting Council staff should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight efficient and high performing permitting team structures and processes.

- Develop Permitting Team Models: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop team models for different agency roles (i.e., sponsor, lead agency, coordinating agency) that focus on driving efficiencies through process improvements and technology, and develop guidelines for forming new permitting teams.

- Create Permitting Job Personas: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop personas to showcase the roles needed on each type of permitting team and roles, recognizing that some variance will always remain, and the type of hiring authority that should be used to acquire those roles (e.g., IPA for highly specialized needs). This should also include new roles focused on process improvements; technology and data acquisition, use, and development; and product management for efficiency, improved customer experience, and effectiveness.

- Define Standardized Permitting Roles and Job Analyses: With the support of Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should identify roles that can be standardized across agencies based on the personas, and collaborate with permitting agencies to develop standard job descriptions and job analyses.

- Develop Permitting Practice Guide: In collaboration with Deputy Secretaries and CERPOs, Permitting Council staff should develop a primer on federal permitting practices that explains how to efficiently and effectively complete permitting activities.

- Place Organizational Strategy Fellows: Permitting Council staff should hire at least one fellow to their staff to lead this effort and coordinate/liaise between permitting teams at different agencies.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: Permitting Council staff should collaborate with the CHCO Council to mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates.

- Revise Permitting Funding Requirements: Permitting Council staff should include requirements for the adoption of new team models and roles in the resources and coordination provided to permitting agencies to drive process efficiencies.

Improve Workforce Strategy, Planning, and Decisions through Quality Workforce Metrics

Agency permitting leaders and those working across agencies do not have the information to make informed workforce decisions on hiring, deployment, or workload sharing. Attempts to access accurate permitting workforce data highlighted inefficient methods for collecting, tracking, and reporting on workforce metrics across agencies. This results in a lack of transparency into the permitting workforce, data quality issues, and an opaque hiring progress. With these unknowns, it becomes difficult to prioritize agency needs and support. Permitting provided a purview into this challenge, but it is not unique to the permitting domain. OPM, OMB, the CHCO Council, and Permitting Council staff need to accurately gather and report on hiring metrics for talent surges and workforce metrics by domain.

- Establish Permitting Workforce Data Standards: OPM should create minimum data standards for hiring and expand existing data standards to include permitting roles in employee records, starting with the Request for Personnel Action that initiates hiring (SF52). Permitting Council staff should be consulted in defining standards for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Agency Data Sharing: OPM and OMB should require agencies share personnel action data; this should be done automatically through APIs or a weekly data pull between existing HR systems. To enable this sharing, agencies must centralize and standardize their personnel action data from their components.

- Create Workforce Dashboards: OPM should create domain-specific workforce dashboards based on most recent agency data and make it accessible to the relevant agencies. This should be done for the permitting workforce.

- Mandate Permitting Hiring Forecasts: The CHCO Council should mandate permitting hiring forecasts annually with quarterly updates. This data should feed into existing agency talent management/acquisition systems to track workforce needs and support adaptive decision making.

Invest in Professional Development and Early Career Pathways

There are few early career pathways and development opportunities for personnel who engage in permitting activities. This limits agencies’ workforce capacity and extends learning curves for new staff. This results in limited applicant pools for hiring, understaffed permitting teams, and limited access to expertise. More recently, many of the roles permitting teams hired for were higher level GS positions. With a greater focus on early career pathways and development, future openings could be filled with more internal personnel. In our research, one hiring manager shared how they established an apprenticeship program for early career staff, which has led 12 interns to continue into permanent federal service positions. The Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should create more development opportunities and early career pathways for civil servants.

- Invest in Training to Upskill and Reskill Staff: The Permitting Council staff should continue investing in training and development programs (i.e., Permitting University) to upskill and reskill federal employees in critical permitting skills and knowledge. Leveraging the knowledge gained through creating standard permitting team roles and collaborating with permitting leaders, the Permitting Council staff should define critical knowledge and skills needed for permitting and offer additional training to support existing staff in building their expertise and new employees in shortening their learning curve.

- Allocate Permitting Staff Across Offices and Regions: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should implement a flexible staffing model to reallocate staff to projects in different offices and regions to build their experience and skill set in key areas, where permitting work is anticipated to grow. This can also help alleviate capacity constraints on projects or in specific locations.

- Invest in Flexible Hiring Opportunities: CERPOs and Deputy Secretaries should invest in a range of flexible hiring options, including 10-year STEM term appointments and other temporary positions, to provide staffing flexibility depending on budget and program needs. Additionally, OPM needs to redefine STEM to include technology positions that do not require a degree (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialists).

- Establish a Permitting Apprenticeship: The Permitting Council staff should establish a 1-year apprenticeship program for early career professionals to gain on-the-job experience and learn about permitting activities. The apprenticeship should focus on common roles shared across agencies and place talent into agency positions. A rotational component could benefit participants in experiencing different types of work.

Improve and Invest in Pooled Hiring for Common Positions

Outdated and inaccurate job descriptions slow down and delay the hiring process. Further delays are often caused by the use of non-skills-based assessments, often self-assessments, which reduce the quality of the certificate list, or the list of eligible candidates given to the hiring manager. HR leaders confront barriers in the authority they have to share job announcements, position descriptions (PDs), classification determinations, and certificate lists of eligible candidates (Certs). Coupled with the above ideas on creating consistency in permitting teams and roles and better workforce data, OPM, CHCOs, OMB, Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should improve and make joint announcements, shared position descriptions, assessments, and certificates of eligibles for common positions a standard practice.

- Provide CHCOs the Delegated Authority to Share Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs: OPM and OMB should lower the barriers for agencies to share key hiring elements and jointly act on common permitting positions by delegating the authority for CHCOs to work together within and across their agencies, including with the Permitting Council staff.

- Revise Shared Certificate Policies: OPM and OMB should revise shared certificate policies to allow agencies to share certificates regardless of locations designated in the original announcement and the type of hire (temporary or permanent). They should require skills-based assessments in all pooled hiring. Additionally, OPM should streamline and clarify the process for sharing certificates across agencies. Agencies need to understand and agree to the process for selecting candidates off the certificate list.

- Create a Government-wide Platform for Permitting Hiring Collaboration: OPM should create a platform to gather and disseminate permitting job announcements, PDs, classification determinations, job/competency evaluations, and cert. lists to support the development of consistent permitting teams and roles.

- Pilot Sharing of Announcements, PDs, Assessments, and Certs for Common Permitting Positions: OPM and the CHCO Council should collaborate with the Permitting Council staff to select most common and consistent permitting team roles (e.g., Environmental Protection Specialist) to pilot sharing within and across agencies.

- Track Permitting Hiring and Workforce Performance through Data Sharing and Dashboards: Permitting Council staff, Deputy Secretaries, and CERPOs should leverage the metrics (see Improve Workforce Decisions Through Quality Workforce Metrics) and data actions above to track progress and make adjustments for sharing permitting hiring actions.

- Incorporate Shared Certificates into Performance: OPM and the CHCO Council should incorporate the use of shared certificates into the performance evaluations of HR teams within agencies.

Improve Human Resources Support for Hiring Managers

Hiring managers lack sufficient support in navigating the hiring and recruiting process due to capacity constraints. This causes delays in the hiring process, restricts the agency’s recruiting capabilities, limits the size of the applicant pools, produces low quality candidate assessments, and leads to offer declinations. The CHCO Council, OPM, CERPOs, and the Permitting Council staff need to test new HR resourcing models to implement hiring best practices and offer additional support to hiring managers.

- Develop HR Best Practice Case Studies: OPM should conduct research to develop a series of case studies that highlight HR best practices for recruitment, performance management, hiring, and training to share with CHCOs and provide guidance for implementation.

- Document Surge Hiring Capabilities: In collaboration, the Permitting Council staff and CERPOs should document successful surge hiring structures (e.g., strike teams), including how they are formed, how they operate, what funding is required, and where they sit within an organization, and plan to replicate them for future surge hiring.

- Create Hiring Manager Community of Practice: In collaboration, the Permitting Council staff and Permitting Agency HR Teams with support from the CHCO Council should convene a permitting hiring manager community of practice to share best practices, lessons learned, and opportunities for collaboration across agencies. Participants should include those who engage in hiring, specifically permitting hiring managers, HR specialists, and HR leaders.

- Develop Permitting Talent Training for HR: OPM should collaborate with CERPOs to create a centralized training for HR professionals to learn how to hire permitting staff. This training could be embedded in the Federal HR Institute.

- Contract HR Support for Permitting: The Permitting Council staff should create an omnibus contract for HR support across permitting agencies and coordinate with OPM to ensure the resources are allocated based on capacity needs.

- Establish HR Strike Teams: OPM should create a strike team of HR personnel that can be detailed to agencies to support surge hiring and provide supplemental support to hiring managers.

- Place a Permitting Council HR Fellow: The Permitting Council should place an HR professional fellow on their staff to assist permitting agencies in shared certifications and build out talent pipelines for the key roles needed in permitting teams.

- Establish Talent Centers of Excellence: The CHCO Council should mandate the formation of a Talent Center of Excellence in each agency, which is responsible for providing training, support, and tools to hiring managers across the agency. This could include training on hiring, hiring authorities, and hiring incentives; recruitment network development; career fair support; and the development of a system to track potential candidates.

Next Steps

These recommendations aim to address talent challenges within the federal permitting ecosystem. As you can see, these issues cannot be addressed by one stakeholder, or even one agency, rather it requires effort from stakeholders across government. Collaboration between these stakeholder groups will be key to realizing sustainable permitting workforce capacity.

Technology and NEPA: A Roadmap for Innovation

Improving American competitiveness, security, and prosperity depends on private and public stakeholders’ ability to responsibly site, build, and deploy proposed critical energy, infrastructure, and environmental restoration projects. Some of these projects must undergo some level of National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review, a process that requires federal agencies to consider the environmental impacts of their decisions.

Technology and data play an important role in and ultimately dictate how agencies, project developers, practitioners and the public engage with NEPA processes. Unfortunately, the status quo of permitting technology falls far short of what is possible in light of existing technology. Through a workstream focused on technology and NEPA, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and the Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) have described how technology is currently used in permitting processes, highlighted pockets of innovation, and made recommendations for improvement.

Key findings, described in more detail below, include:

- Systems and digital tools play an important role at every stage of the permitting process and ultimately dictate how federal employees, permit applicants, and constituents engage with NEPA processes and related requirements.

- Developing data standards and a data fabric should be a high priority to support agency innovation and collaboration.

- Case management systems and a cohesive NEPA database are essential for supporting policy decisions and ensuring that data generated through NEPA is reusable.

- Product management practices can and should be applied broadly across the permitting ecosystem to identify where technology investments can yield the highest gains in productivity.

- User research methods and investments can ensure that NEPA technology are easier for agencies, applicants, and constituents to use.

Introduction

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization that works to embed science, technology, innovation, and experience into government and public discourse. The Environmental Policy Innovation Center (EPIC) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan organization focused on building policies that deliver spectacular improvement in the speed of environmental progress.

FAS and EPIC have partnered to evaluate how agencies use technology in permitting processes required by NEPA. We’ve highlighted pockets of innovation, talked to stakeholders working to streamline NEPA processes, and made evidence-based recommendations for improved technology practices in government. This work has substantiated our hypothesis that technology has untapped potential to improve the efficiency and utility of NEPA processes and data.

Here, we share challenges that surfaced through our work and actionable solutions that stakeholders can take to achieve a more effective permitting process.

Background

NEPA was designed in the 1970s to address widespread industrial contamination and habitat loss. Today, it often creates obstacles to achieving the very problems it was designed to address. This is in part because of an emphasis on adhering to an expanding list of requirements that adds to administrative burdens and encourages risk aversion.

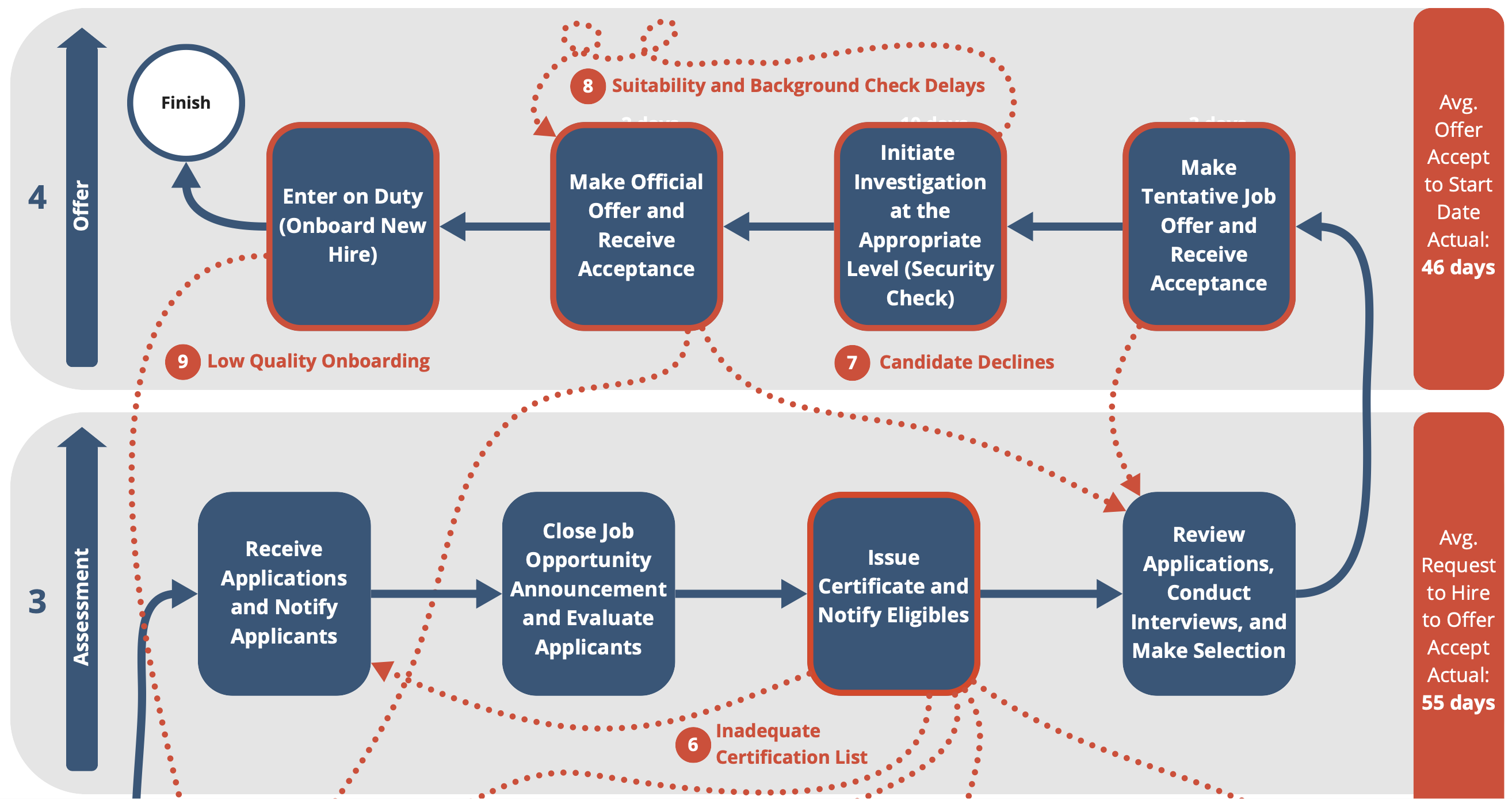

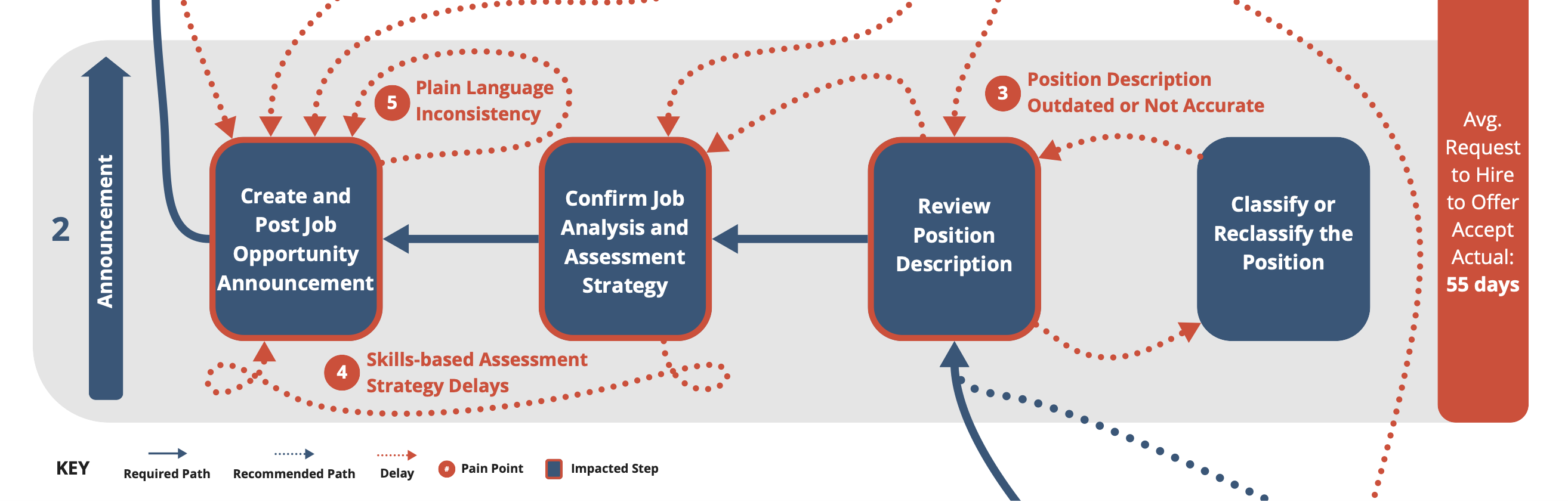

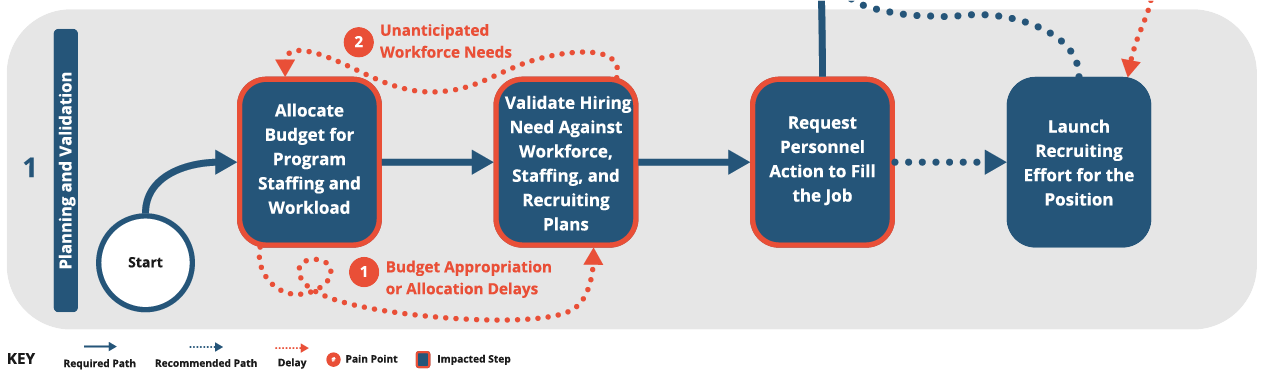

Digital systems and tools play an important role at every stage of the permitting process and ultimately dictate how federal employees, permit applicants, and constituents engage with NEPA processes and related requirements. From project siting and design to permit application steps and post-permit activities, agencies use digital tools for an array of tasks throughout the permitting “life-cycle”—including for things like permit data collection and application development; analysis, surveys, and impact assessments; and public comment processes and post-permit monitoring.

Unfortunately, the current technology landscape of NEPA comprises fragmented and outdated data, sub-par tools, and insufficient accessibility. Agencies, project developers, practitioners and the public alike should have easy access to information about proposed projects, similar previous projects, public input, and up-to-date environmental and programmatic data to design better projects.

Our work has largely been focused on center-of-government agencies and actions agencies can take that have benefits across government.

Key actors include:

- The Permitting Council. Established in 2015 through the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (known as FAST-41), the Permitting Council is charged with facilitating coordination of qualified infrastructure projects subject to NEPA as well as serving as a center of excellence for permitting across the federal government. Administrative functions and salaries are supported primarily by annual appropriations. Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) funding enables “ongoing operation of, maintenance of, and improvements to the Federal permitting dashboard” while Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) funding supports the center of excellence and coordination functions.

- The Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ). CEQ is an office within the Executive Office of the President established in 1969 through the National Environmental Policy Act. Executive Order 11991, issued in 1977, gave CEQ the authority to issue regulations under NEPA. However, President Trump rescinded that EO in January 2025 and issued a new Executive Order on Unleashing American Energy. This new Executive Order directs the Chair of CEQ to provide “guidance on implementing the National Environmental Policy Act…and propose rescinding CEQ’s NEPA regulations found at 40 CFR 1500 et seq.” CEQ has received annual appropriations to support staff as well as supplemental funding. The IRA provided CEQ with $32.5 million to “support environmental and climate data collection efforts and $30 million more to “support efficient and effective environmental reviews.“

Below, we outline key challenges identified through our work and propose actionable solutions to achieve a more efficient, effective, and transparent NEPA process.

Challenges and Solutions

Product management practices are not being applied broadly to the development of technology tools used in NEPA processes.

Applying product management practices and frameworks has potential to drastically improve the return on investment in permitting technology and process reform. Product managers help shepherd the concept for what a project is trying to achieve and get it to the finish line, while project managers ensure that activities are completed on time and on budget. In a recent blog post, Jennifer Pahlka (Senior Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists and the Niskanen Center) contrasts the project and product funding models in government. Product models, executed by a team with product management skills, facilitate iterative development of software and other tools that are responsive to the needs of users.

Throughout our work, the importance of product management as a tool for improving permitting technology has become abundantly clear; however there is substantial work to be done to institutionalize product management practices in policy, technology, procurement, and programmatic settings.

Solutions:

- Create process maps for the permitting process – in detail – within and across agencies. Once processes are mapped, agencies can develop tailored technology solutions to alleviate identified administrative burdens by either removing, streamlining, or automating steps where possible and appropriate. As part of this process, agencies should evaluate existing software assets, use these insights to streamline approval processes, and expand access to the most critical applications. Agencies can work independently or in collaboration to inventory their software assets. Mapping should be a collaborative, iterative effort between project leads and practitioners. Mapping leads should consider whether the co-development of user journeys with practitioners who play different roles in the permitting process, such as applicants, environmental specialists (federal employees), and public commenters, would be a useful first step to help scope the effort.

- Hire product management and customer experience specialists in strategic roles. Agencies and center of government leaders should carefully consider where product management and customer experience expertise could support innovation. For example, the Permitting Council could hire a product management specialist or customer experience expert to consult with agencies on their technology development projects. Fellowship programs like the Presidential Innovation Fellows (PIF) or U.S. Digital Corps can be leveraged to provide agencies with expertise for specific projects.

- Strategically leverage existing product management guidance and resources. Agencies should use existing resources to support product management in government. The 18F unit, part of the General Services Administration (GSA)’s Technology Transformation Services (TTS), helps federal agencies build, share, and buy technology products. 18F offers a number of tools to support agencies with product management. GSA’s IT Modernization Centers of Excellence can support agency staff in using a product-focused approach. The Centers focused on Contact Center, Customer Experience, and Data and Analytics may be most relevant for agencies building permitting technology. In addition, the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) “collaborates with public servants throughout the government”; their staff can assist with product, strategy, and operations as well as procurement and user experience. 18F and USDS could work together to provide product management training for relevant staff at agencies with a NEPA focus. 18F or USDS could create product management guidance specifically for agencies working on permitting, expanding on the 18F Product Guide. These resources could also explore how agencies can make decisions about building or buying when developing permitting technology. Agencies can also look to the private sector and NGOs for compelling examples of product development.

- Learn from successes at other agencies. We have written about how agencies have successfully applied product management approaches inside and outside of the NEPA space.

Siloed, fragmented data and systems cost money and time for governments and industry

As one partner said, “NEPA is where environmental data goes to die.” Data is needed to inform both risk analysis and decisions; data can and should be reused for these purposes. However, data used and generated through the NEPA process is often siloed and can’t be meaningfully used across agencies or across similar projects. Consequently, applicants and federal employees spend time and money collecting environmental data that is not meaningfully reused in subsequent decisions.

Solutions:

- Develop a data fabric and taxonomy for NEPA-related data. CEQ’s Report to Congress on the Potential for Online and Digital Technologies to Address Delays in Reviews and Improve Public Accessibility and Transparency, delivered in July 2024, recommends standards that would give agencies and the public the ability to track a project from start to finish, know specifically what type of project is being proposed, and understand the complexity of that project. The federal government should pilot interagency programs to coordinate permitting data for existing and future needs. Chief Environmental Review and Permitting Officers (CERPOs) should invest in this process and engage their staff where applicable and appropriate.

- Establish a Digital Service for the Planet to work with agencies specifically on how environmental data is collected and shared across agencies. The Administration should create a Digital Service for the Planet (DSP) that is staffed with specialists who have prior experience working on environmental projects. The DSP should support cross-agency technology development and improve digital infrastructure to better foster collaboration and reduce duplication of federal environmental efforts to achieve a more integrated approach to technology—one that makes it easier for all stakeholders to meet environmental, health, justice, and other goals for the American people.

- Centralize access to NEPA documents and ensure that a user-friendly platform is available to facilitate public engagement. The federal government should ensure public access to a centralized repository of NEPA documents, and a searchable, user-friendly platform to explore and analyze those documents. Efforts to develop a user friendly platform should include dedicated digital infrastructure to continually update centralized datasets and an associated dashboard. Centralizing searchable historical NEPA documents and related agency actions would make it easier for interested parties to understand the environmental assessments, analyses, and decisions that shape projects. Congress can require and provide resources to support this, agencies can invest staff time in participation, and agency leaders can set an expectation for participation in the effort.

Technology tools used in NEPA processes fall far short of their potential

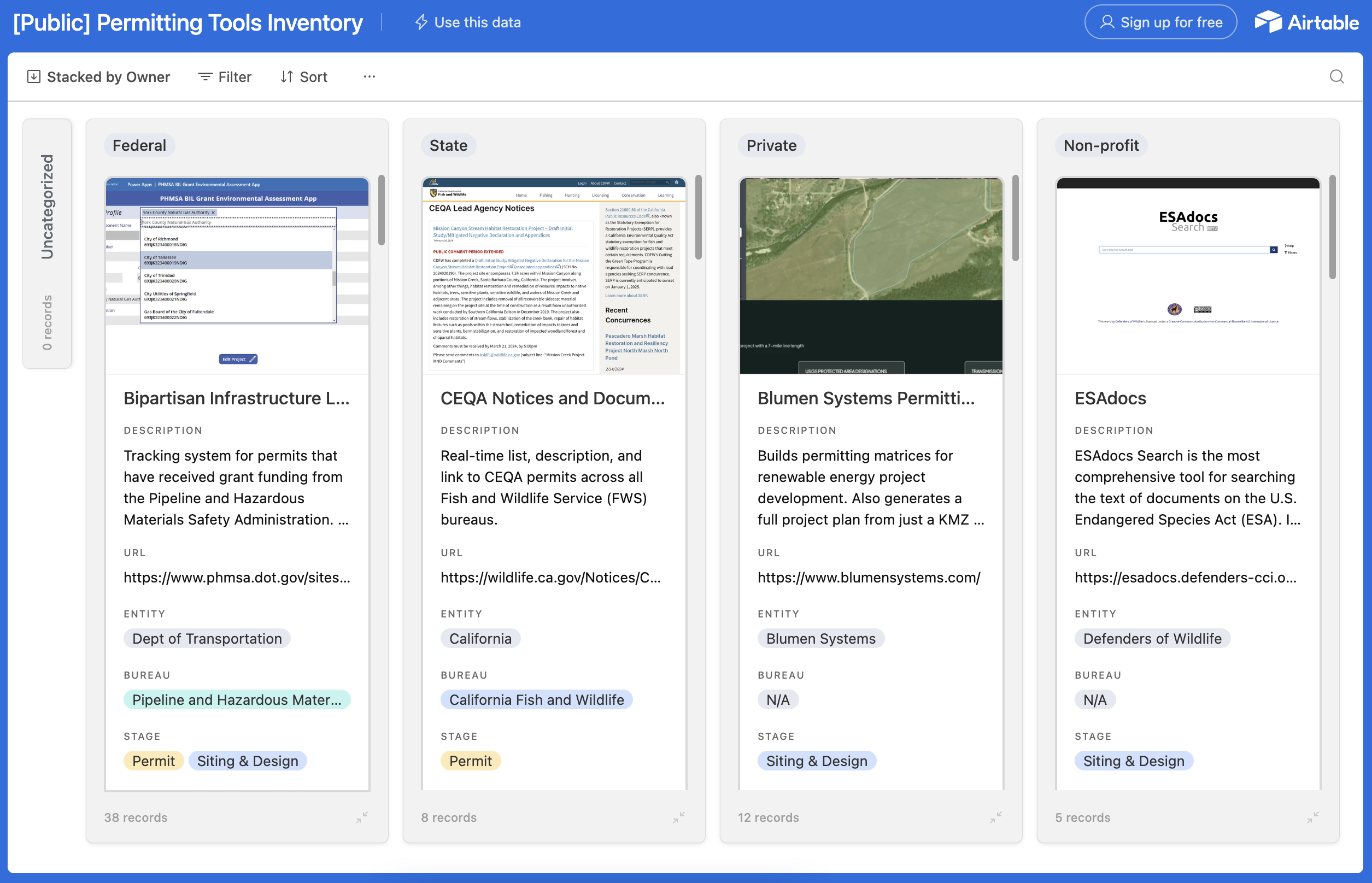

The status quo of permitting technology falls far short of what is possible in light of existing technology. Permitting tools we identified in our inventory range widely in intended use cases and maturity levels. Opportunities exist to reduce feature fragmentation across these tools and improve the reliability of their content. Additionally, many software tools are built and used by a single agency, instead of being efficiently shared across agencies. Consequently, technology is not realizing its potential to improve environmental decision-making and mitigation through the NEPA process.

Solutions:

- Set more ambitious modernization goals. We have the technological capabilities to go above and beyond data fabric and taxonomy. CEQ and the Permitting Council can focus on helping agencies scale successful permitting technology projects and develop decision support tools. This could include supporting agency tools to bring e-permitting into the modern era, which speeds processing time and saves staff time. Agency tools to enhance could include USACE’s Regulatory Request System and tool for tracking wetland mitigation credits (RIBITS), USFWS’s tool for Endangered Species Act consultation (IPaC), the Permitting Council’s FAST-41 dashboard, and CEQ’s eNEPA tool. Policymakers and staff working to improve permitting technology should consider replicating the functionality of successful existing tools, and automating the determination of “application completeness”, which has frequently been cited as a source of delays.

- Institutionalize human centered design (HCD) principles and processes. Agencies should encourage and incentivize deployment of HCD processes. The Permitting Council, GSA, and agency leadership can play a key role in institutionalizing these principles through agency guidance and staff training. Applying human-centered design can ensure thoughtful, well-designed automation of tasks that free up staff members to focus their limited time and attention on matters that need their focus and, crucially, increase the number of NEPA decisions the federal government is able to reach in a designated period of time.

- Prioritize development of digital applications with easy-to-use forms. Application systems may look different from agency to agency depending on their specific needs, but all should prioritize easy-to-use forms, working collaboratively where applicable. Relevant HCD principles include entering data once, user-friendly templates or visual aids, and auto-populating information. Eventually, more advanced features could be incorporated into such forms—including features like AI-generated suggestions for application improvements, fast-tracking reviews for submissions that use templates, and highlighting deviations from templates for review by counsel.

- Create better pre-design tools to give applicants more information about where they can site projects. Improved pre-design tools can help applicants anticipate components of a site that may come up in environmental reviews, such as endangered species. Examples include Vibrant Planet’s landscape resilience tool and the USFWS iPAC platform. These platforms can be developed by agencies or by private-sector and nonprofit organizations. Agencies should seek opportunities to invest in tools that meet multiple needs or provide shared services. The Permitting Council and/or CEQ could lead an interagency task force on modernizing permitting and establish a cross-agency workflow to prevent the siloing of these tools and support agencies in pursuing shared services approaches where applicable.

- Invest in decision-support tools to better equip federal employees. Many regulators lack either the technical skillset to review projects and/or lack the confidence to efficiently and effectively review permit applications to the extent needed. Decision-support tools are needed to lay out all options that the reviewer needs to be aware of to make an informed and timely decision that isn’t based on institutional knowledge (e.g., existing categorical exclusions or nationwide permits that fit the project). These types of decision-support tools can also help create more consistency across reviews. CEQ and/or the Permitting Council could establish a cross-agency workflow to prevent siloing of these tools and support agencies in pursuing shared services approaches where applicable.

Existing NEPA technology tools are difficult for agencies, applicants, and constituents to use

Agencies generally do not conduct sufficient user research in the development of permitting technology. This can be because agencies do not have the resources to hire product management expertise or train staff in product management approaches. Consequently, agencies may only engage users at the very end (if at all), or not think expansively about the range of users in the development of technology for NEPA applications. Advocacy groups and permit applicants aren’t well considered as tools are being developed. As a consequence, permitting forms and other tools are insufficiently customized for their sectors and audiences.

Solutions:

- Incorporate user research into existing projects. Agencies can build user experience activities and funding into project plans and staffing for bespoke permitting tool development. There are resources available to agencies to incorporate user research if they don’t have the talent in-house (as many don’t). These include the 18F unit, GSA’s IT Modernization Centers of Excellence, USDS, and the Presidential Innovation Fellows program.

- Elevate case studies of agencies using user research to improve product delivery. As a center of excellence, the Permitting Council can support elevating agencies using user research. CEQ can also support sharing both challenges and opportunities across agencies. CERPOs can exchange ideas and elevate case studies to explore what is working.

- Launch a regulatory sandbox for permitting. A sandbox would allow testing of different forms and other small interventions. The sandbox would provide an environment for intentional AB testing (e.g., test a new permitting form with ten applicants). The sandbox could be managed by the Permitting Council or another agency, but responsibility to oversee the sandbox should be contained within one single agency. This office should be empowered to offer waivers or exemptions. Ideally, a customer experience specialist would lead the activities of the sandbox. Improving forms that project proponents or public commenters might encounter during the NEPA process is low-hanging fruit that could be a first focus area for the sandbox. Better forms would make processes simpler for applicants, but would also make it possible for agencies to receive and manage associated geospatial and environmental data with applications.

Poor understanding of the costs and benefits of NEPA processes

Costs and benefits of the federal permitting sector have to date been poorly quantified, which makes it difficult to decide where to invest in technology, process reform, talent, or a combination. Applying technology solutions in the wrong place or at the wrong time could make processes more complicated and expensive, not less. For instance, automating a process that simply should not exist would be a waste of resources. At the same time, eliminating processes that provide critical certainty and consistency for developers while delivering substantial environmental benefits would work against goals of achieving greater efficiency and effectiveness.

A more reliable, comprehensive accounting of NEPA costs and benefits will help us design solutions that cost less for taxpayers, better account for public input, and enable rapid yet responsible deployment of energy infrastructure and other critical projects.

Solutions:

- Equip agencies with case management systems that automatically collect data needed for process evaluation. Case management software systems support coordination across multiple stakeholders working on a shared task (e.g., an Environmental Impact Statement). Equipping agencies with these systems would enable automatic capture of data needed to conduct rigorous cost-benefit assessments, providing researchers with rich data to study the impacts of policy interventions on staff time and document quality. Automatic data collection would also drastically reduce the need for expensive and time-consuming retrospective data gathering and analysis efforts. and

- Rapidly execute on a permitting research agenda to support innovation. Establishing a robust case management system may take time. In the interim, agencies, philanthropy, nonprofits, and others can undertake research projects that inform nearer-term decisions about NEPA. Collaborations with user researchers, designers, and product managers will make this research agenda successful. Key gaps a research agenda could address include:

- Money and Time Federal Agencies Spend on NEPA Tasks

- How many staff whose primary job is spent on permitting-related tasks does each agency employ at the national, region, and field levels? The study scope could start with the agencies on the Permitting Council, as they are agencies with relatively large roles in the permitting process.

- How do staffing levels correspond with the number and kind of permitting actions by region and field office? Sources for agency staffing data could include General Services Administration employment classifications and agency NEPA offices.

- What is each agency’s total budget allocated for NEPA review? Do budget codes accurately reflect permitting work?

- Research Gap 2: Private Sector Cost and Scale. The NEPA sector is larger than just the federal government. For example, private-sector consulting firms sometimes help project sponsors prepare their applications and navigate federal processes. A number of private sector entities support the permitting process through government contracts. Questions include:

- What is the total market size of the permitting private sector (dollar amount and employees)?

- What percent is spent on federally mandated permits? How does this break down by task? What are the most expensive labor components and why?

- Research Gap 3: Technology-related Costs

- Building on FAS and EPIC’s permitting inventory, what is the annual technology budget for each agency’s major permit tracking system? Answers to this question should include both internal and external staff costs.

- How many years has each system been in operation? How did the application receive initial funding (e.g., appropriation, general fund, permitting-specific budget)? This helps us know 1) which systems are likely in the most need of an upgrade and 2) how likely it is that funding will be available in the future to modernize.

- Money and Time Federal Agencies Spend on NEPA Tasks

Conclusion