A Reflection on the 2023 Hiroshima ICAN Academy

The views expressed herein belong solely to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Government.

As I stood outside of the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall, now memorialized as the Atomic Bomb Dome, I was amazed by the profound stillness of the park even though it sat in the shadow of the city’s tall buildings beside busy streets filled with cars and pedestrians.

I glanced at an image on my phone of the area taken several days after the bomb dropped. The Atomic Bomb Dome stood defiantly amidst the wasteland of flattened buildings and burnt rubble. Now, it stood beside large green trees and towering apartment buildings in the gaze of a large athletic stadium. I had learned that the river beside me, now full of boats bringing tourists to the nearby Miyajima Island, was once filled with bodies of people who sought a brief relief for their burning flesh. I tried to imagine how this peaceful and modernized city looked in 1945, but visualizing such horror was beyond my imagination.

Without intentionally traveling to the Peace Park in Hiroshima, one could almost entirely overlook the city’s tragic history. Amidst the modern stores, apartment buildings, and restaurants, several buildings that survived the atomic bomb blast have been preserved, bearing the heavy weight of Hiroshima’s legacy. They remember the flattened buildings, waves of fire, black rain, and harrowing human cries for water.

The New Voices on Nuclear Weapons Fellowship at the Federation of American Scientists helped me enter the field with no prior knowledge of nuclear weapons, let alone deterrence theory and the history of nuclear proliferation. I can confidently say that without this fellowship opportunity, I would not have thought I could have the authority to speak about nuclear weapons.

Many conversations and debates about nuclear weapons are rooted in complicated theories and hypothetical scenarios, making it difficult to join the discussion. While I believe it’s challenging for any human brain to fully internalize nuclear weapons’ lethal capacity, we can comprehend how nuclear weapons surpass the threats posed by other forms of warfare in terms of their destructive and indiscriminate potential.

I applied to the 2023 Hiroshima-ICAN Academy on Nuclear Weapons and Global Security to conceptualize the true destructive power of a nuclear weapon. Prior to the academy, I believed indisputable international norms prevented government officials from accepting disarmament and abolition as plausible nuclear policy guidelines. In speaking with hibakusha and many young activists in Japan, my preconceived notion was challenged; I learned that the propensity to dismiss the feasibility of nuclear abolition is not innate. Those who have experienced the apocalyptic repercussions of a nuclear weapon not only endorse the necessity of abolition but themselves underscore that the pursuit of disarmament is not just a policy objective but a moral responsibility—one that demands collective action and a commitment to preventing future generations from experiencing the unspeakable tragedies of the past.

The 2023 Hiroshima-ICAN Academy on Nuclear Weapons and Global Security is organized by Hiroshima Prefecture and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize laureate. The goal of the program is to educate young leaders who can make concrete contributions toward a more peaceful and secure world. In addition to several peers from the United States, I joined other participants from China, Italy, India, Kenya, Lebanon, Ukraine, and more.

The 2023 Hiroshima-ICAN Academy hosted several online lectures and four days of educational sessions in Hiroshima, Japan. Online webinars gave participants the opportunity to interact with famous activists, such as Koko Kondo, Mary Dickson, and Melissa Parke, and hear from esteemed professionals in the nuclear field like Dr. Vincent Intondi and Izumi Nakamitsu. We learned about the suffering of downwinders in the United States, ICAN’s initiatives towards abolition, the UN’s disarmament efforts, and the racial history of nuclear weapons testing and usage. Prior to the online portion of the academy, I knew nothing of the intersectionality of nuclear weapons threats.

While in Hiroshima, we had a busy week of meetings, lectures, and tours, including a guided tour of the Peace Park and meetings with Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui, Hiroshima Governor Hidehiko Yuzaki, and atomic bomb survivor Keiko Ogura. Together, we learned about Hiroshima nonprofit efforts to support atomic bomb survivors, discussed the ecological effects and colonial history of nuclear weapons testing, and planned how to effectively interject discussions about disarmament in our respective communities.

The most memorable part of the ICAN Academy for me was speaking with atomic bomb survivors, also known as hibakusha. I was fortunate to spend several hours with hibakusha Ms. Sadae Kasaoka, who was 12 years old when the atomic bomb dropped. Ms. Kasaoka urged all of the Hiroshima ICAN participants to share her story with our communities.

I was struck by Ms. Kasaoka’s bravery and resilience. No human wants to dwell on the most traumatic experience of their lives, let alone recount it for hundreds of listeners each year. However, Ms. Kasaoka has been doing so year after year for the benefit of our education.

Like many children in Japan during World War II, Ms. Kasaoka would help demolish wooden houses to prevent the spread of fire after air raids. Her life consisted of work, rushing to bomb shelters, and fearing for her family. On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Kasaoka was in her home when the atomic bomb was dropped. Ms. Kasaoka saw a blast of light through the window of her home and was knocked down by the initial blast of the bomb. Hours later, the images she would see in her town would be seared into her memory forever.

During our conversation with Ms. Kasaoka, she recounted the destruction of her friends’ homes and vividly remembered watching humans walk up the mountain, skin hanging off of their bodies like ghosts. When her father was brought back to the house on a stretcher several hours later, she did not recognize him because his face had significantly swelled and his skin was burnt black. She would spend the next two days applying cucumbers and potatoes to his skin to cool the burning while picking maggots out of her father’s flesh as he pleaded with her for water. Later, she would be brought a bag of ashes and hair, allegedly belonging to her mother. The atomic bomb would leave Sadae Kasaoka an orphan like thousands of young Japanese children in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Ms. Kasaoka’s words, “This is the reality of war.” Her story is only one of hundreds of thousands.

Prior to my fellowship with FAS, like many young Americans, I believed that nuclear weapons were a rusting relic of the past. At the end of my fellowship, I recognize these weapons are being cleaned and shined as arsenals expand and the risk of nuclear weapons use grows to be higher than at any time since the Cold War. Both FAS and the ICAN Academy led to my realization of a sobering truth: nuclear weapons cannot coexist with mankind indefinitely.

The Federation of American Scientists values diversity of thought and believes that a range of perspectives — informed by evidence — is essential for discourse on scientific and societal issues. Contributors allow us to foster a broader and more inclusive conversation. We encourage constructive discussion around the topics we care about.

New Nuclear Bomb Training At Dutch Air Base

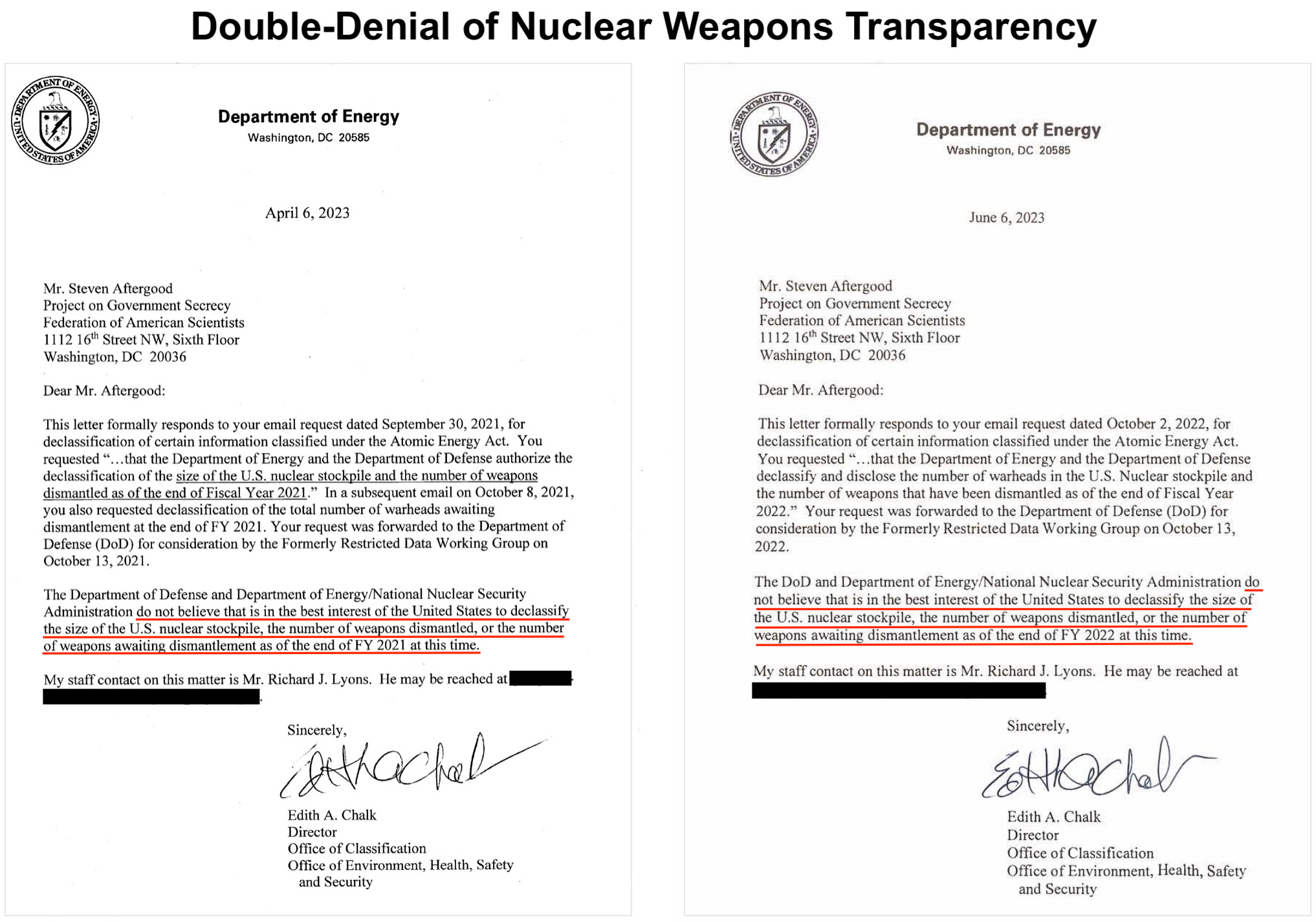

The Dutch air base at Volkel appears to have started integration training with the new U.S. B61-12 guided nuclear gravity bomb in 2021, even before the bomb went into full-scale production and entered the U.S. stockpile in 2022.

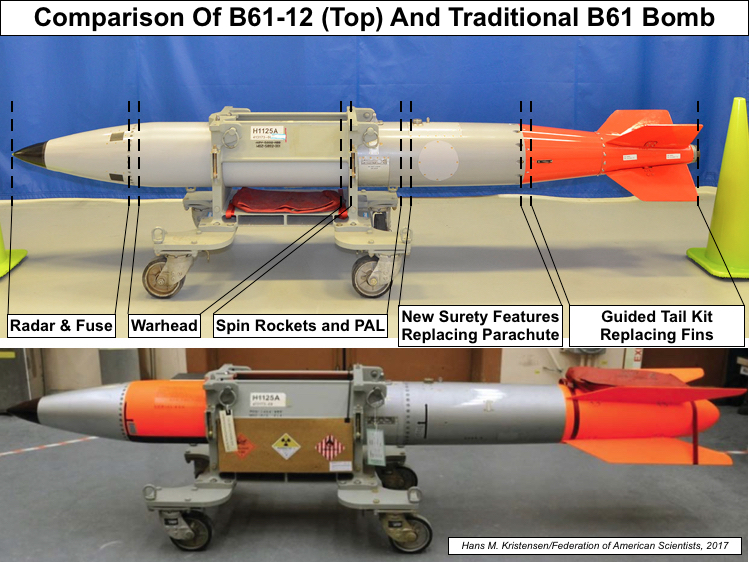

An image included in a Sandia National Laboratories video from early-2022 that snapshots accomplishments from 2021 shows what appears to be a B61-12 training shape hanging under the right wing of an F-16 (see image below).

The Dutch air force apparently started training for the new U.S. B61-12 guided nuclear bomb in 2021.

The video does not not identify the location but the image appears to be from Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands; The design of the protective aircraft shelter visible in the photo is unique to Dutch shelters. Eleven of the shelters at the Volkel are equipped with an underground vault that can hold up to four B61 bombs. But normally they only hold 1-2 bombs each for an estimated 10-15 bombs at the base. A picture posted on a public forum shows the outline of a vault inside a Protective Aircraft Shelter at Volkel Air Base (see below).

Eleven aircraft shelters at Volkel are equipped with an underground nuclear weapons storage vault.

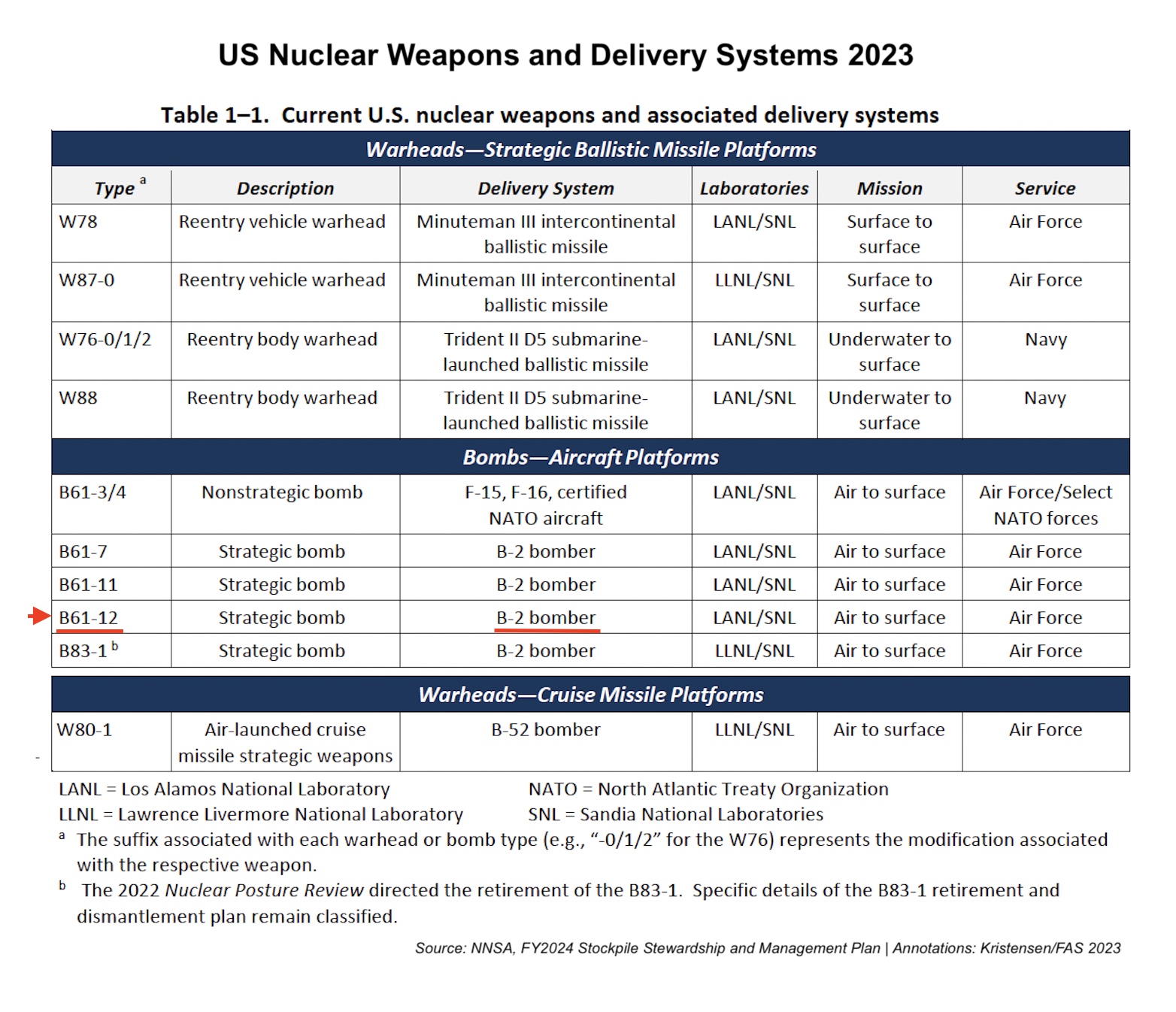

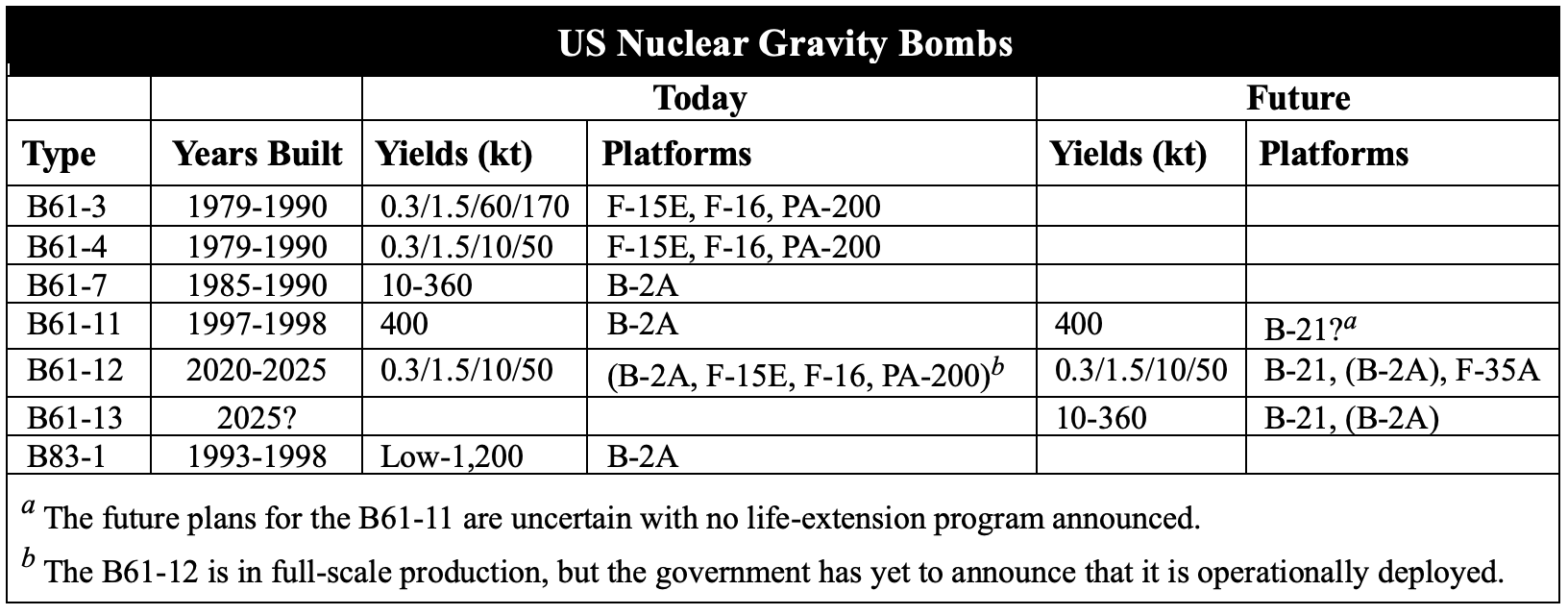

Although the training B61-12 is mounted on an F-16, the weapon is not yet assigned to the NATO fighter jets. The B61-12 has entered the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile, but it is so far only assigned to the B-2 strategic bomber, according to the U.S. Department of Energy. The fighter jets (F-15E, F-16, Tornado) have completed integration flights but had, as of recently, not yet been assigned the B61-12 (see table below). The new F-35A that will take over the nuclear strike role at Volkel and other European bases had also not been assigned the B61-12 yet, but U.S. European Command training was scheduled to start in 2023.

The new B61-12 nuclear bomb had, until recently, only been assigned to the B-2 strategic bomber not yet to dual-capable fighter aircraft.

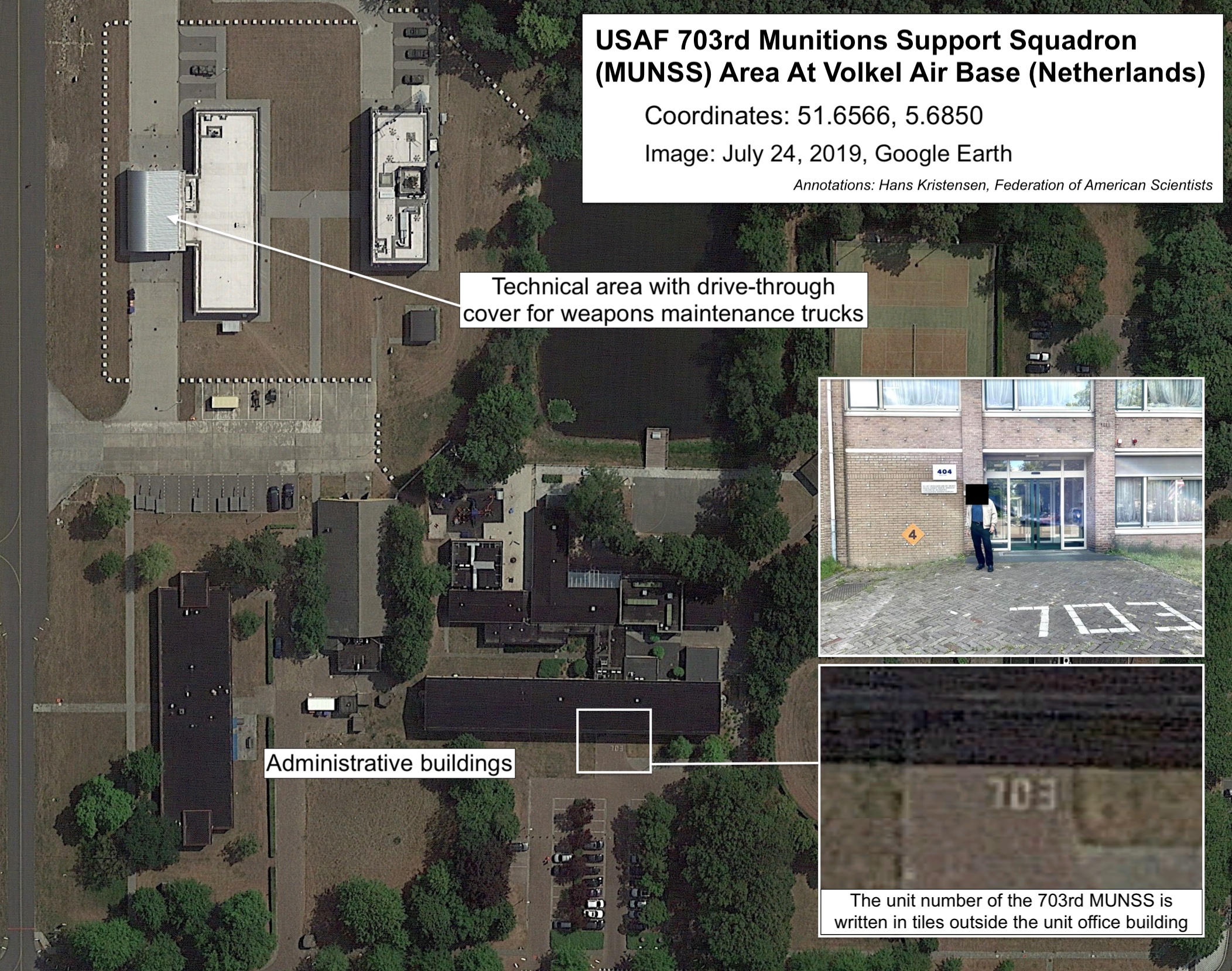

The 312th Squadron of the 1st Wing at Volkel Air Base is part of the so-called NATO nuclear sharing arrangement where the United States equips Dutch F-16s (and aircraft of five other NATO countries: Belgium, Germany, Greece, Italy, Turkey) and trains their pilots to employ U.S. B61 nuclear bombs in war. During peacetime, the weapons are under the custody of U.S. Air Force units (the 703rd Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS) at Volkel).

The location of the USAF nuclear weapons custodial unit at Volkel Air Base is written in tiles.

On December 8, 2023, the 312th Squadron performed what is known as an elephant walk where 14 F-16s were displayed on the runway at the same time. A similar display was performed in 2021. At least one of the pilots in the 2023 event can be seen wearing a helmet visor with a nuclear weapons explosion mushroom cloud (see image below). It is possible, but unknown, that this is the helmet of the commander of the 312th Squadron.

One of the pilots in the December 2023 elephant walk at Volkel Air Base wore a nuclear mushroom cloud design on his helmet visor.

The nuclear weapons upgrade at Volkel Air Base is part of a broad nuclear modernization program of U.S. non-strategic nuclear forces in Europe that includes replacement of aircraft, bombs, base infrastructure, nuclear command and control, readiness level, operational planning, and public visibility.

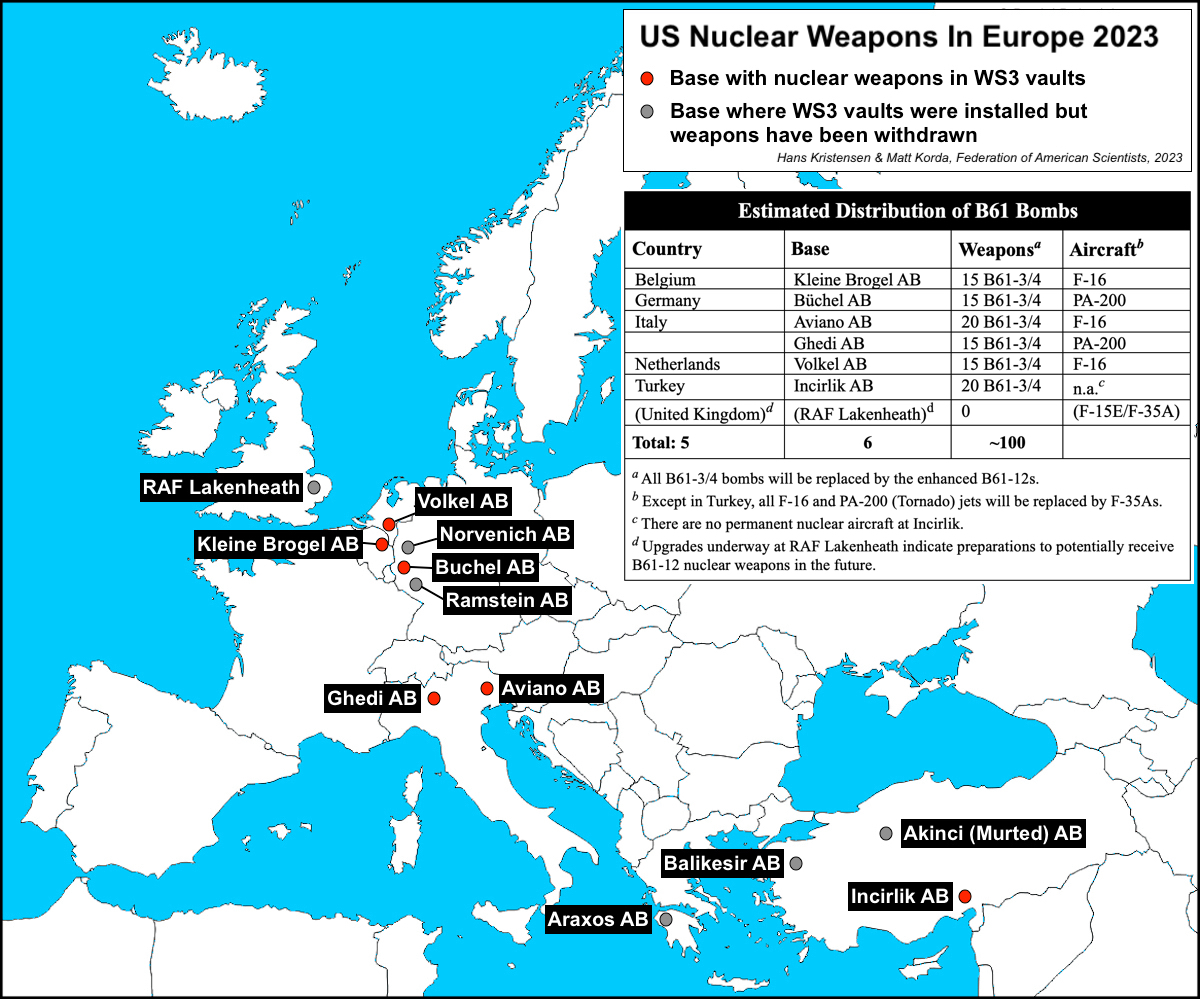

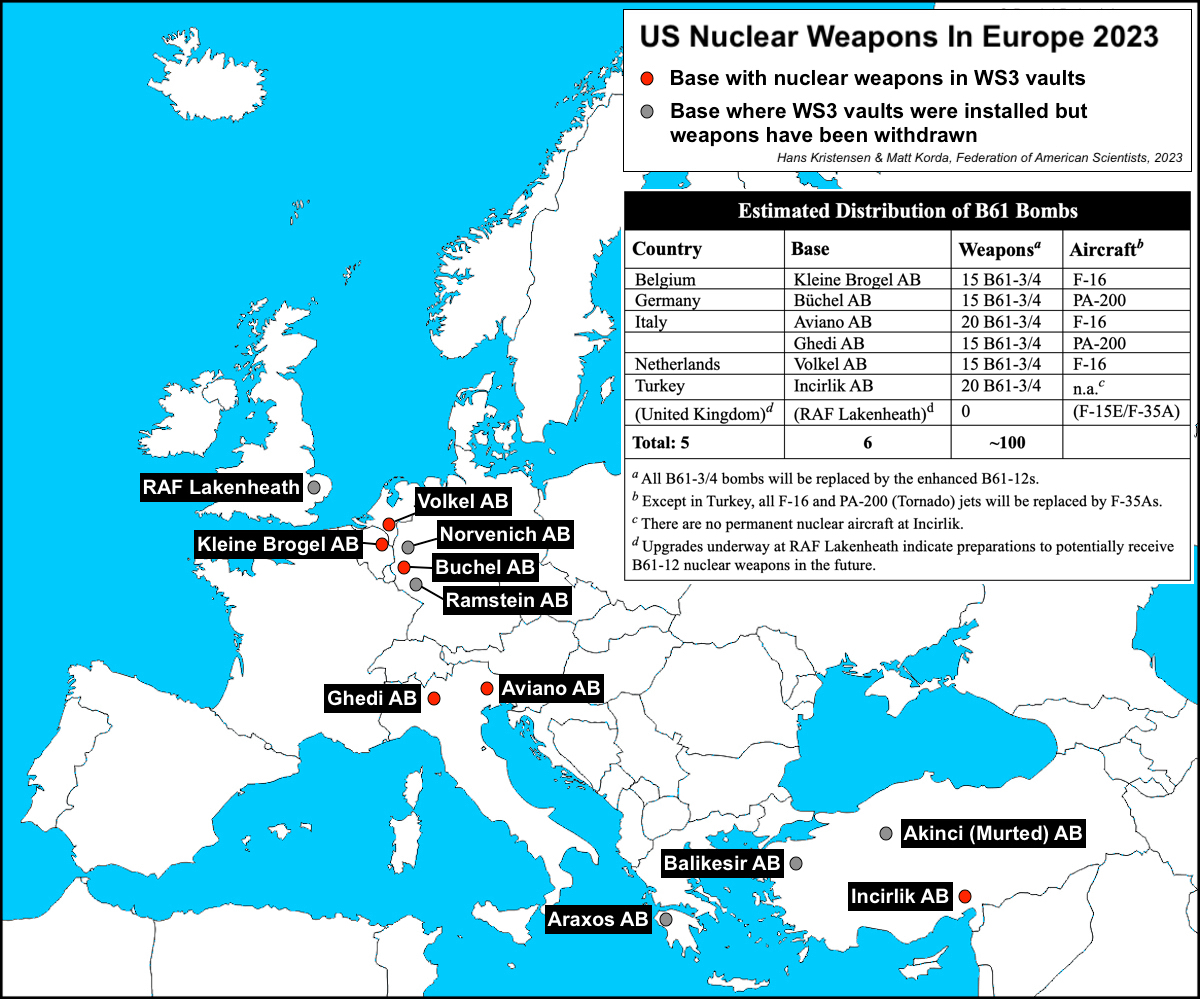

There is no public information that the B61-12 bombs have been shipped to Europe yet but the C-17A nuclear transport aircraft has been cleared and the first shipments could potentially begin next year. If so, they would replace the estimated 100 B61-3/4 nuclear bombs currently deployed in Europe (see figure below).

Additional information:

• Nuclear Notebook: Nuclear Weapons Sharing, 2023

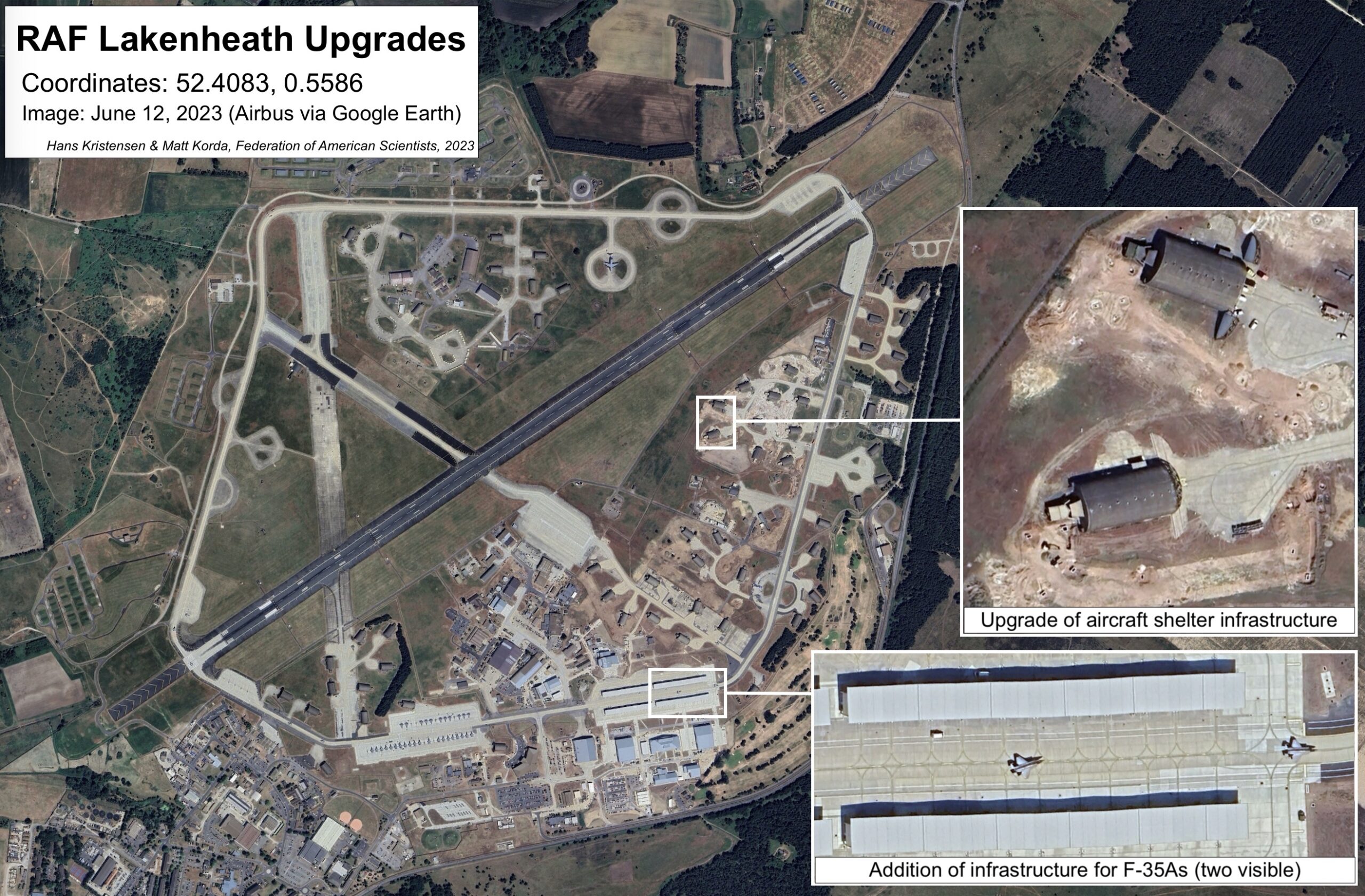

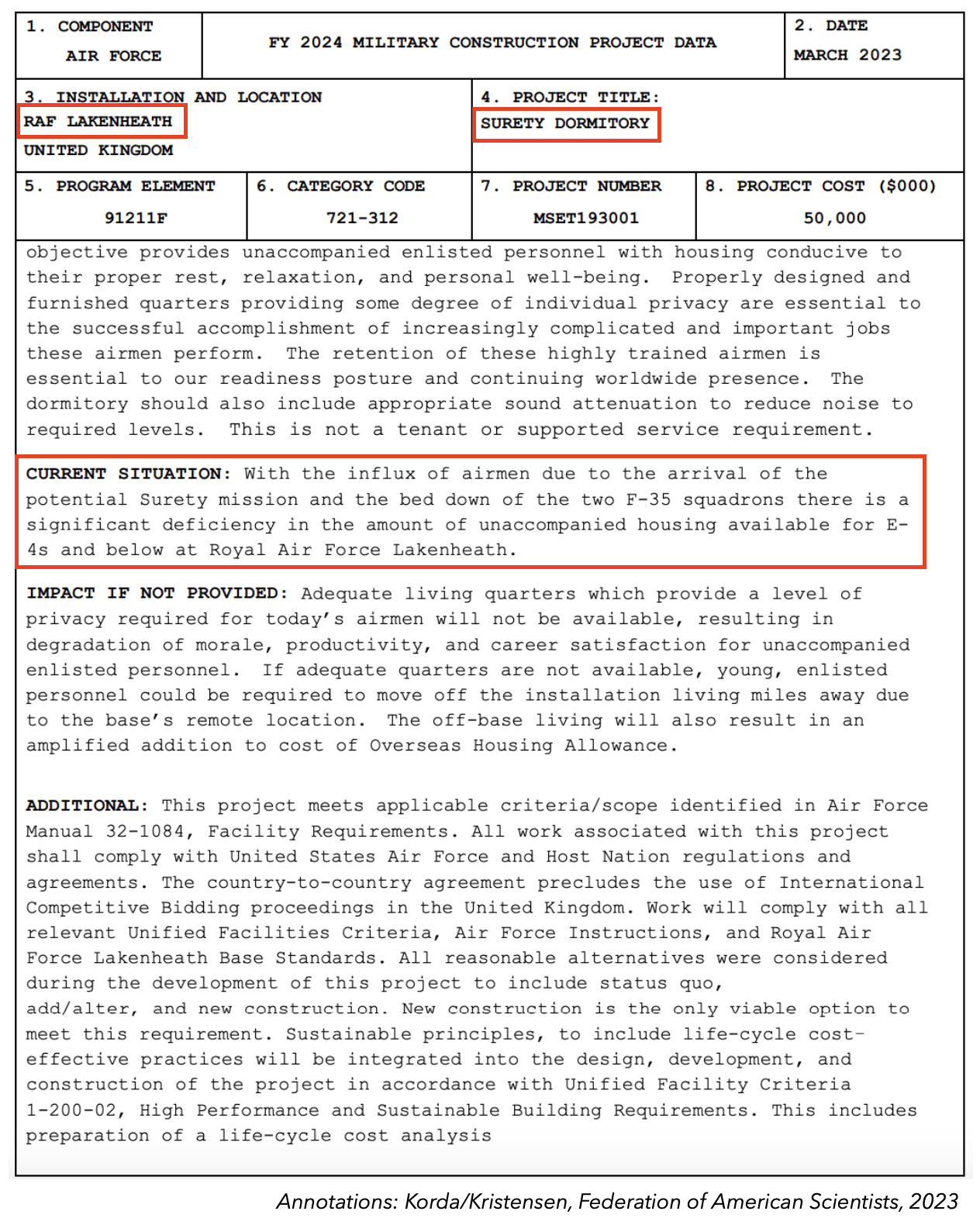

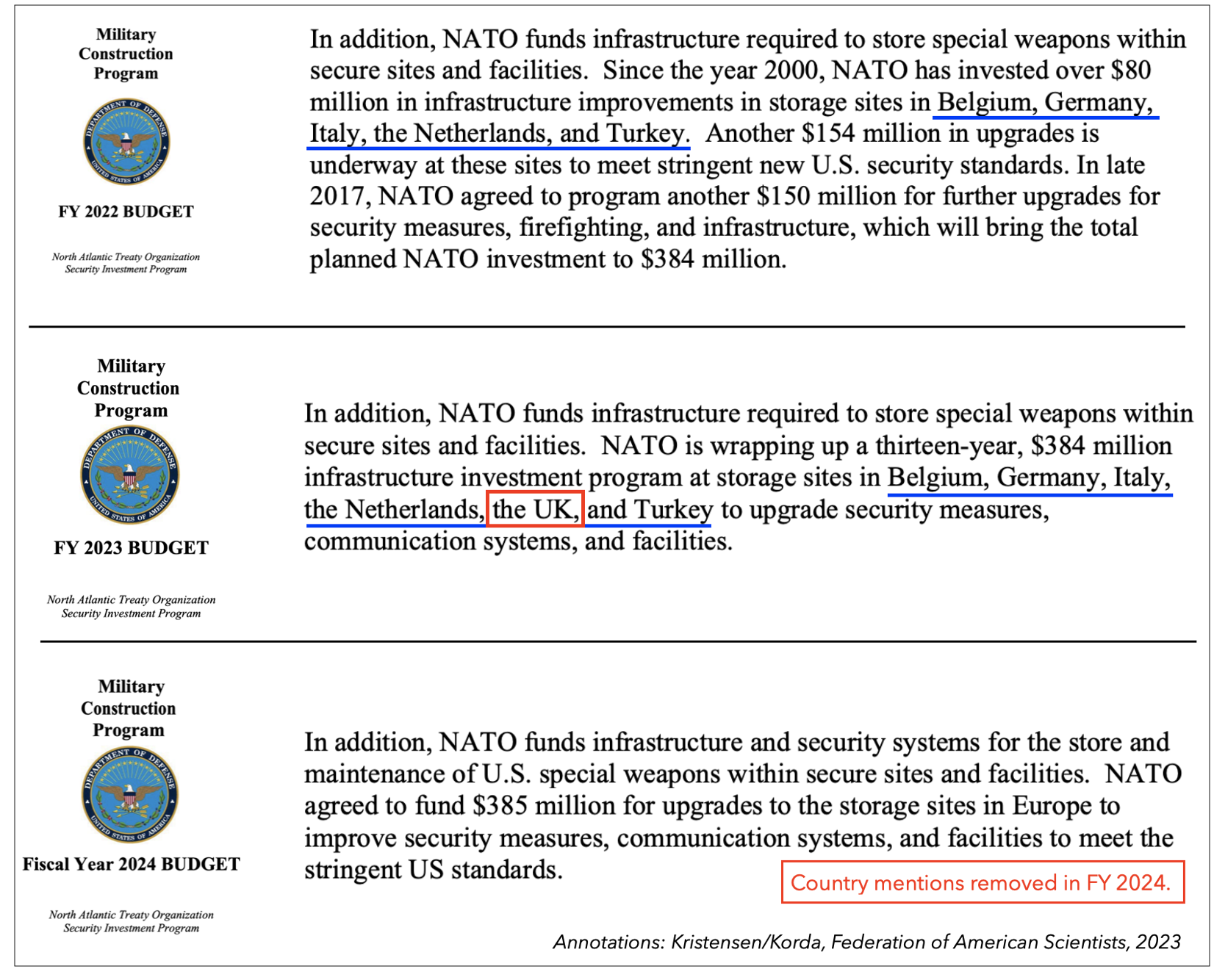

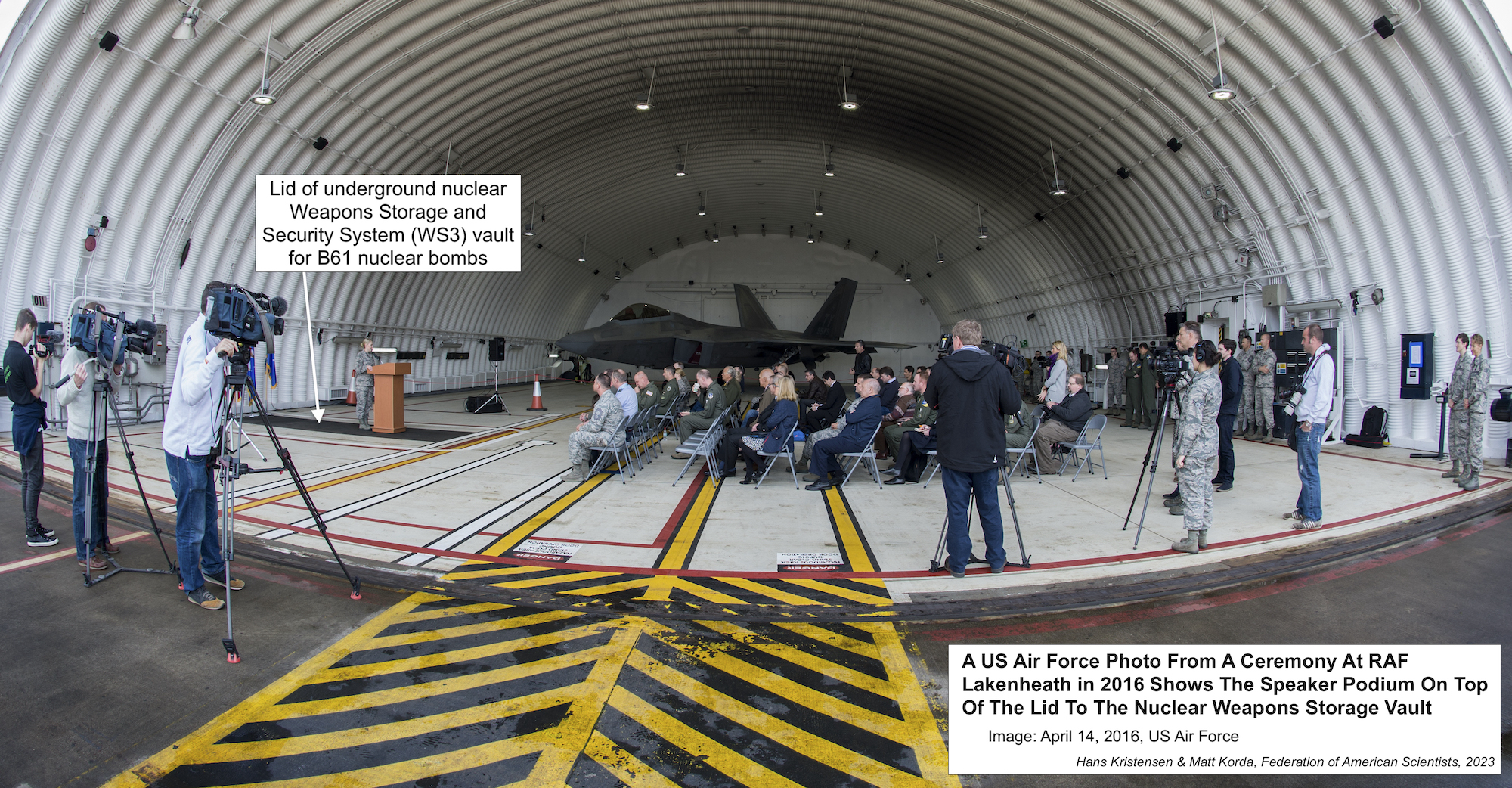

• Increasing Evidence That The US Air Force’s Nuclear Mission May Be Returning To UK Soil

• The C-17A Has Been Cleared To Transport B61-12 Nuclear Bomb To Europe

• NATO Steadfast Noon Exercise And Nuclear Modernization In Europe

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

TPNW2MSP: Overview and Key Takeaways

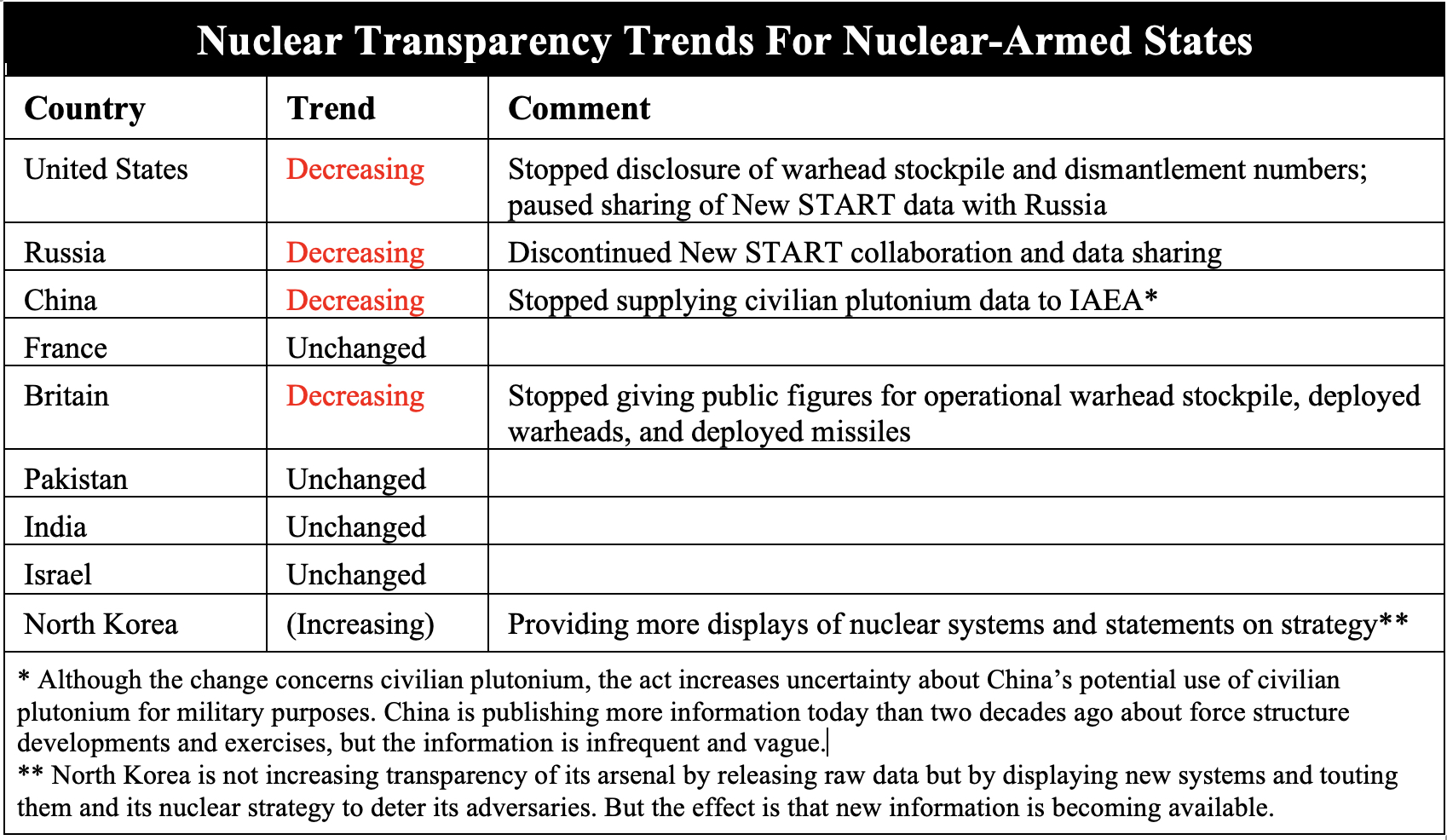

The 2nd Meeting of States Parties (MSP) to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW) took place at United Nations Headquarters in New York City from November 27 through December 1. Participants in the Meeting included 59 member nations, 35 observer states, around 700 civil society registrants, members of the scientific community, and representatives of communities affected by nuclear weapons.

The Meeting culminated in agreement by states parties on a joint declaration and package of decisions. Arguably, the most significant outcome of the 2nd MSP was the consensus joint declaration challenging long-held assumptions of nuclear deterrence theory and affirming the security risks it poses.

What’s happened since the first MSP

The first Meeting of States Parties to the TPNW occurred in Vienna, Austria in June 2022, where states parties adopted the Vienna Action Plan. That plan listed 50 actions for States Parties to implement the TPNW and goal of global nuclear disarmament and created three working groups on disarmament verification; victim assistance, environmental remediation, and international cooperation and assistance; and universalisation. The Vienna Plan additionally created thematic focal points for gender and complementarity of the TPNW with other fora like the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). The working groups each met several times during the intersessional period.

The first MSP also created a Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) of 15 experts to study and provide scientific and technical expertise on a variety of issues related to nuclear weapons. The SAG is the first international scientific body formally created by a multilateral treaty process to promote nuclear disarmament. The group met nine times during the intersessional period to prepare its report to the second MSP, and its final report drew heavily upon research conducted by independent open-source analysts, including the Federation of American Scientists.

Several states have joined or taken action toward joining the treaty during the intersessional period. The Bahamas, Barbados, Burkina Faso, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Haiti, and Sierra Leone signed the treaty; the Dominican Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Malawi ratified the treaty; Sri Lanka acceded to the treaty; and Indonesia, the fourth largest country in the world by population, recently enacted the TPNW into law within its parliament and is expected to soon complete ratification.

Nearly half of NPT states parties have now signed the TPNW, reflecting growing unacceptance of the lack of progress on nuclear weapons states’ Article VI disarmament obligations.

Noteworthy happenings during 2MSP

The 2nd Meeting of States Parties included a large number of national and other statements and reports. The proceedings notably included moving testimony from nuclear-affected communities, active participation and presentation of research by civil society, a report from the Scientific Advisory Group, notable observer state attendance, and statements from a group of parliamentarians from around the world and the financial community.

Impacted communities

One of the most important features of the TPNW is its focus on impacted communities. Participants and attendees included victims of nuclear testing in Kazakhstan, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Australia, and French Polynesia; Hibakusha (atomic bomb survivors) from Hiroshima and Nagasaki; downwinders from the U.S. Southwest; and communities impacted by uranium mining.

Benetick Kabua Maddison, Executive Director of the Marshallese Education Initiative, delivered a joint statement to the Meeting on behalf of 26 affected community organizations and supported by 45 allied organizations that provided testimony of the harm of nuclear weapons and called for land remediation and universalization of the treaty.

Scientific Advisory Group

In addition to numerous civil society research presentations and statements throughout the week, the Scientific Advisory Group (SAG) presented its Report on the Status and Developments Regarding Nuclear Weapons to the Meeting. This presentation marked the first formal participation of the SAG in the proceedings of the TPNW following its formation.

SAG co-chairs Dr. Zia Mian and Dr. Patricia Lewis introduced the report to the MSP. The report, heavily citing the work of FAS’s Nuclear Information Project, included an overview of the global status of nuclear stockpiles, nuclear modernization, nuclear risks, humanitarian consequences, and disarmament verification. Additionally, the SAG recommended a global scientific study sponsored by the UN on the effects and consequences of nuclear war.

Observer states

Unsurprisingly, none of the nuclear-armed states attended, but several U.S. treaty allies – Australia, Belgium, Germany, and Norway – attended the MSP as observers. Two of the observers (Belgium and Germany) are part of the NATO nuclear sharing arrangements to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons in times of war.

The delegate from Norway made a statement in support of NATO as a nuclear alliance: “Norway stands fully behind NATO’s nuclear deterrence and posture, including the established nuclear sharing arrangements.” According to some analysts, this may be the first time Norway has explicitly supported U.S. nuclear weapons deployments in Europe in a multilateral disarmament forum. This continues a trend of increased support of NATO nuclear missions by Norway since the end of the Cold War, which has recently included participating in joint exercises with US B-52 bombers and a US B-2 bomber landing in Norway for the first time.

The German delegation similarly supported NATO’s nuclear mission in its statement to the Meeting while criticizing Russia’s announcement of nuclear weapons deployments to Belarus. The representative stated that “confronted with an openly aggressive Russia, the importance of nuclear deterrence has increased for many states, including for my country.”

Three observer states to the first MSP were notably absent from the second: The Netherlands, Finland, and Sweden. The Netherlands is the only NATO member to participate in the initial negotiations of the TPNW. Despite this, the Netherlands has consistently voted against UNGA resolutions welcoming the adoption of the TPNW, and, after the first MSP, the Dutch Foreign Ministry reported that continued observation of TPNW proceedings “is not useful.”

Finland voted against the UNGA resolution on the TPNW for the first time in 2022 and chose not to observe the 2nd MSP, possibly due to its recent NATO membership. Sweden similarly voted against the resolution for the first time in 2022 and was absent from the 2nd MSP. These actions by Sweden could be related to its bid for NATO membership and its brand new Defense Cooperation Agreement with the U.S.

Points of tension

Although states parties came to agreement on a final declaration and package of decisions (with the MSP even closing around two hours earlier than scheduled on the final day), there were some points of disagreement and division throughout the week.

One primary disagreement was on nuclear sharing – particularly how strongly the final declaration should condemn it. European states parties pushed back on forceful language to prevent their regional allies and the U.S. from being implicated in the condemnation that they wanted centered on Russia’s nuclear deployments to Belarus. The final joint declaration avoided mention of specific sharing arrangements and simply included a condemnation of and call to cease all such arrangements.

In a similar vein, some states like South Africa wanted to include strong language on the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) that would condemn both Russia’s recent de-ratification and the fact that the U.S. has never ratified the CTBT. U.S. allies at the Meeting, however, wanted language focusing solely on Russia’s actions. Ultimately, neither country was identified by name in the joint declaration; instead, states parties made a broad call for all countries to sign and ratify the CTBT and promote its entry into force.

Unique participants

Alongside states parties, observer states, and civil society groups, the TPNW 2MSP included participation from a diverse, global group of parliamentarians as well as representatives from the financial community.

A delegation of 23 parliamentarians from 14 different countries, including US Rep. Jim McGovern (D-MA), delivered a statement to the Meeting urging governments (in some cases their own) to join the treaty.

The financial community provided a statement to the MSP on behalf of over 90 investors to promote collaboration between states parties and the financial community to divest from the nuclear weapons industry.

Results of the MSP: Final declaration and decisions

The Meeting of States Parties closed on Friday, December 1st around 4:30 PM after consensus agreement on a joint declaration and package of decisions.

Through the joint declaration, states presented their consensus view that nuclear risks are growing due to the actions of nuclear weapons states: “Nuclear risks are being exacerbated in particular by the continued and increasing salience of and emphasis on nuclear weapons in military postures and doctrines, coupled with the on-going qualitative modernization and quantitative increases in nuclear arsenals, and the heightening of tensions.”

States parties additionally declared the catastrophic humanitarian effects of nuclear weapons as the central impetus for pursuing and achieving global nuclear disarmament, spotlighting the human and environmental costs to argue that “the only guarantee against the use of nuclear weapons is their complete elimination and the legally binding assurance that they will never be developed again.” States jointly rejected any normalization of nuclear rhetoric and identified nuclear threats and deterrence as security risks, declaring:

“The threat of inflicting mass destruction runs counter to the legitimate security interests of humanity as a whole. This is a dangerous, misguided and unacceptable approach to security… Far from preserving peace and security, nuclear weapons are used as instruments of policy, linked to coercion, intimidation and heightening of tensions. The renewed advocacy, insistence on and attempts to justify nuclear deterrence as a legitimate security doctrine gives false credence to the value of nuclear weapons for national security and dangerously increases the risk of horizontal and vertical nuclear proliferation… The perpetuation and implementation of nuclear deterrence in military and security concepts, doctrines and policies not only erodes and contradicts nonproliferation, but also obstructs progress towards nuclear disarmament.”

On nuclear sharing, states parties called on all states with nuclear arrangements, including extended nuclear security guarantees, to cease all such arrangements and join the TPNW. They also reaffirmed the complementarity between the TPNW and the NPT and called out the lack of progress nuclear weapons states have made toward their NPT Article VI obligations on disarmament.

The package of decisions included an agreement by states parties to collaborate in challenging false narratives of nuclear deterrence by engaging in and promoting scientific work on the humanitarian consequences of nuclear weapons. This collaboration includes the establishment of a consultative process on security concerns of states to advance arguments against nuclear weapons and nuclear deterrence.

States also agreed to engage in discussions on establishing an international trust fund for victim assistance and environmental remediation. Lack of progress and vague phrasing on such a trust fund is likely due to disagreements on whether or not non-states parties to the TPNW should be able to contribute to the fund. Some states fear non-states parties could use their contributions to the trust fund to avoid strong pressure to join the treaty.

Next steps for the intersessional period

The Third Meeting of States Parties to the treaty will take place in 2025 from March 3 to 7, again in New York.

During the intersessional period, the informal working groups established by the Vienna Action Plan will continue to meet, and focused discussions will take place in order to present a report to the third MSP on the feasibility and guidelines for an international trust fund.

States parties and signatories will engage in an intersessional consultative process along with the Scientific Advisory Group, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), and others with the aim of providing a report to the third MSP containing arguments and recommendations to promote a counternarrative to nuclear deterrence rhetoric.

New Voices on Nuclear Weapons Fellowship: Creative Perspectives on Rethinking Nuclear Deterrence

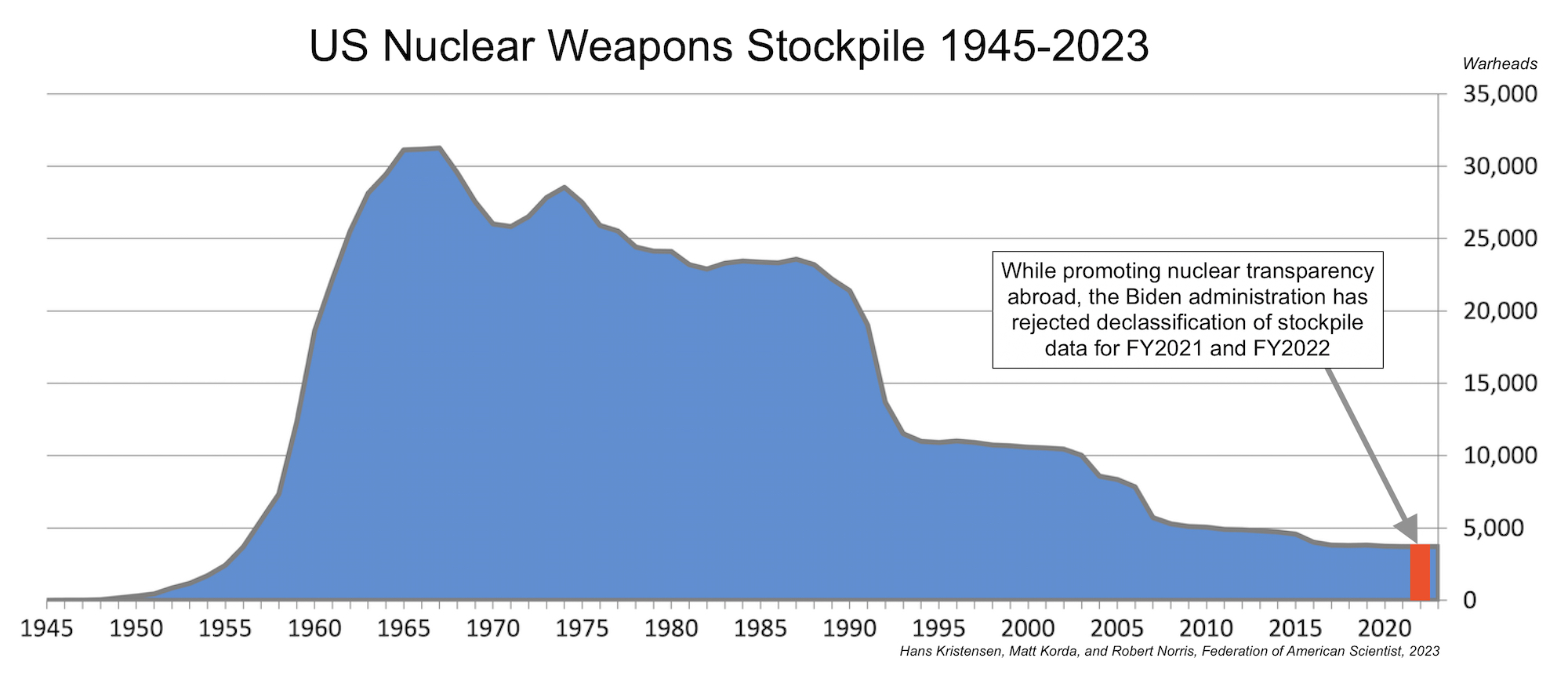

After decades of reductions in the number and salience of nuclear weapons, they are once again at the center of international security. All nine nuclear-armed states are updating their arsenals, and several are expanding them. But despite new military technology and new risks, the concepts underpinning nuclear deterrence have changed little since the height of the Cold War. It is more important than ever that the nuclear policy community recruit new voices from diverse demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds to bring new perspectives, skills, and ideas into the field.

To empower new voices to start their career in nuclear weapons studies, the Federation of American Scientists launched the New Voices on Nuclear Weapons Fellowship. Between May and August 2023, each of our inaugural fellows–Anna Pluff, Clara Sherwood, Cameron Vega, and Charlotte Yeung–was paired with a senior academic or policy expert (John Emery, Jamie Withorne, Alan Robock, and Lovely Umayam) to co-author a research project that provides a creative perspective on nuclear deterrence policy.

As a culmination of this year’s fellowship, FAS hosted a showcase featuring presentations by fellows on their research following a Q&A session, as well as remarks by FAS staff on the fellowship’s structure, goals, and role in empowering the next generation of nuclear policy experts. A recording of the showcase is available for viewing below.

Fellowship Showcase

Fellowship Projects and Publications

New Voices on Nuclear Weapons fellows have had their research projects published across a variety of mediums. Please see below the fellows’ project summaries and publications related to this fellowship to date; this list will be updated as their research continues to be finalized.

Anna Pluff

In the early years of the Cold War, many scientists from the Manhattan Project fervently believed in the idea of “One World or None” and promoted nuclear one worldism. Though the scientific profession had relatively little experience with public engagement before the 1940s, scientists banded together to stretch the political possibilities of professional modes of association to foster support for world government. Anna’s case study looks at the historic role that scientific activism played in nuclear policy through one-worldism and how scientific activism can become a viable force in rethinking deterrence today.

Publications

- “Failed visionaries: Scientific activism and the Cold War” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- “What “Oppenheimer” Misses About The Decision to Drop the Bomb” Inkstick Media.

- “Manhattan Project Scientists Believed the Way We Get Out Alive is World Government” Inkstick Media.

Clara Sherwood

Targeted disinformation and rapid digital communication are complicating nuclear deterrence and crisis management in an unprecedented manner. While nuclear discussions have traditionally occurred privately between governments, in the 21st century, there are a myriad of different actors participating in global nuclear conversations. Clara’s research aims to describe how digital narratives from non-governmental actors are contributing to escalation management, nuclear discourse, and nuclear rhetoric in the context of the Russian-Ukrainian War.

Publications

- “Exiting Musk’s Twitter Has Compromised Nuclear Communication Channels” Inkstick Media.

- “How nongovernmental entities are tailoring their outreach to address nuclear escalation” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Cameron Vega

American nuclear deterrence inherently relies on ethical principles dictating the appropriate use of nuclear weapons; however, these ethical principles insufficiently consider modern scientific modeling demonstrating the devastating climatic impacts of nuclear use. Cameron’s research aims to update the ethical principles underpinning American nuclear deterrence to account for the realities of how nuclear strikes would affect the local environment and global climate change.

Publications

- “The climate blind spot in nuclear weapons policy” The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Charlotte Yeung

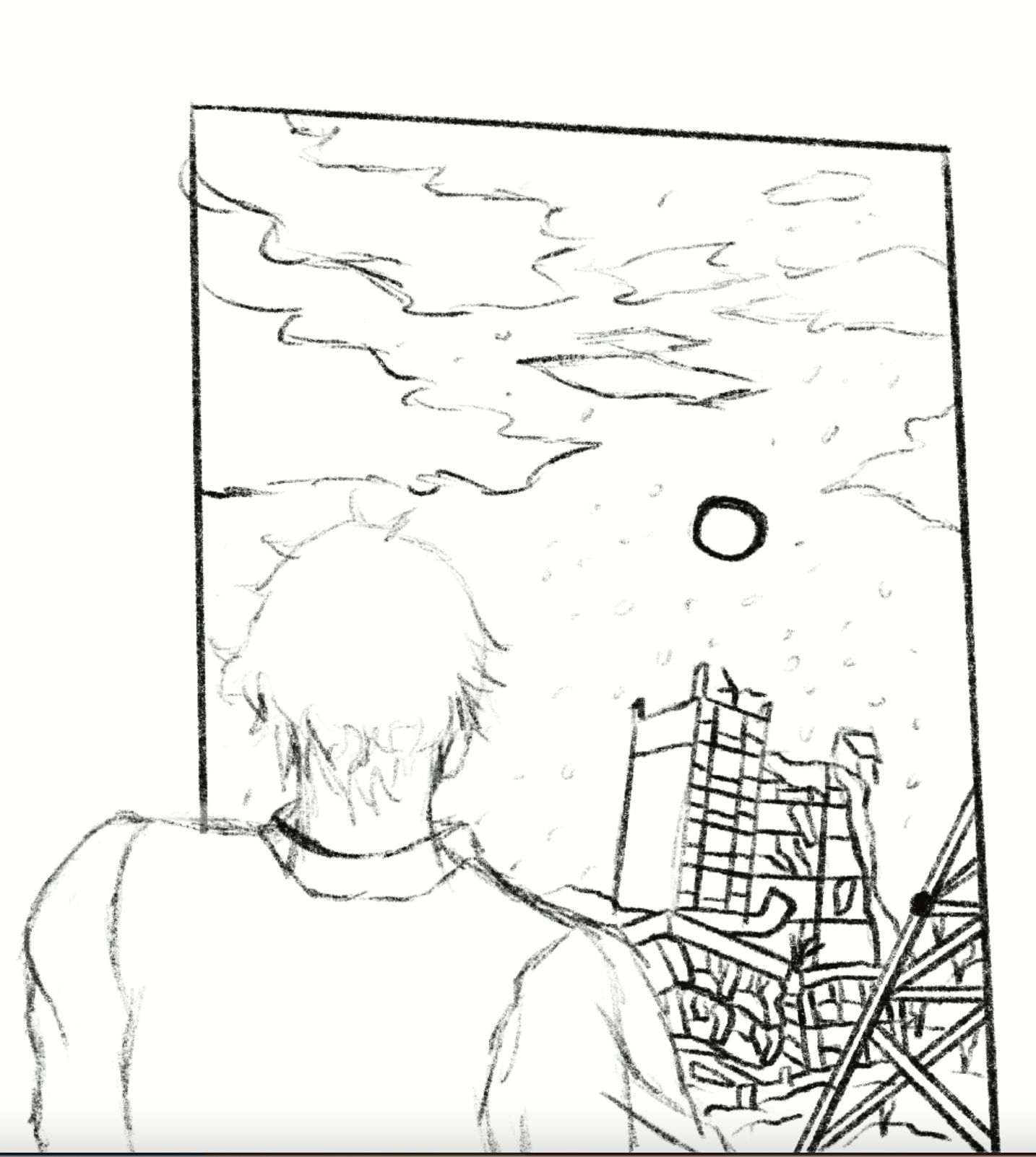

The nuclear narratives told and believed today are rooted in how nuclear weapons are discussed in schools, culture, and locality. The branching narratives in America and Japan are particularly distinct and told through different forms of official narratives taught in textbooks, visual aesthetics, preservation of nuclear-related sites, movements, and the military-industrial complex. Charlotte’s exhibit and poetry ask how education and culture are the roots through which come the multidimensional nature of how Americans and Japanese learn about nuclear weapons and how those define the systems that shape public opinion about nuclear weapons today in those two countries.

Publications

- Culture Blast: Tracing Nuclear Narratives (Online Research Project Website)

- “Culture Blast At The Kurt Vonnegut Museum” Federation of American Scientists

Nuclear Notebook: Nuclear Weapons Sharing, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Fellow Matt Korda, Research Associate Eliana Johns, and Scoville Peace Fellow Mackenzie Knight.

This issue’s column examines the current state of global nuclear sharing arrangements, which include non-nuclear countries that possess nuclear-capable delivery systems for employment of a nuclear-armed state’s nuclear weapons.

Read the full “Nuclear weapons sharing, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Biden Administration Decides To Build A New Nuclear Bomb to Get Rid Of An Old Bomb

A B-2 bomber drops an unarmed B61-12 bomb in a trial. The planned B61-13, which seems intended to persuade Congress to allow retirement of the B83-1, would look the same and arm the new B-21 bomber.

[UPDATED] The Biden administration has decided to add a new nuclear gravity bomb to the US arsenal. The bomb will be known as the B61-13.

The decision to add the B61-13 comes shortly after another new nuclear bomb – the B61-12 – began full-scale production last year and is currently entering the nuclear stockpile. The administration stated that it would not increase the number of weapons in the arsenal and that any B61-13s would come at the expense of the long-planned B61-12.

According to defense officials, the B61-13 will use the warhead from the B61-7 but will be modified with new safety and use-control features as well as a guided tail kit (like the B61-12) to increase the bomb’s accuracy compared with the B61-7.

Although officials assured us that the B61-13 plan is not due to new developments in the target set, the press material from the Pentagon is more direct: B61-13 will “provides us with additional flexibility” by “providing the President with additional options against certain harder and large-area military targets.”

Like the B61-7, the B61-13 will be designed for delivery by strategic bombers: the future B-21 and, until it is retired, possibly also the B-2. It is not intended for delivery by dual-capable fighters. This decision to build the B61-13, however, appears to have less to do with a military need than striking a political deal to get rid of the last megaton-yield weapon in the US arsenal: the B83-1. This weapon was originally slated for retirement under President Obama until it was resurrected by the Trump administration; it has since become a focal point of the battle between the Biden administration, which wants to retire it, and congressional hardliners, who want to keep it.

Change Of Plan

The case for the B61-13 is strange. For the past 13 years, the sales pitch for the expensive B61-12 has been that it would replace all other nuclear gravity bombs. By re-using the B61-4 warhead, adding new safety and use-control features, and increasing accuracy with a guided tail kit, the agencies initially argued that it would be a consolidation of four existing types (B61-3/4/7/10) into a single type of gravity bomb.

Military officials have explained countless times that the B61-12 would be able to cover all gravity missions with less collateral damage than large-yield bombs. Increasing the bomb’s accuracy was the key reason why the tail kit was added, replacing the older drag parachute system of the older weapons.

By reducing the number of bomb types, the administration argued, it would be possible to reduce the total number of gravity bombs in the arsenal by 50 percent and save a substantial amount of money. Moreover, by using a warhead for the B61-12 with the least amount of fissile material, the proliferation risk from theft would be reduced, so the argument went. When the B61-10 was retired in 2016, the pitch obviously changed to consolidating three bomb types, rather than four, into one. But the Obama administration also wanted to use it to replace the ultra-high yield B83-1 and eventually the B61-11 earth-penetrator.

The Biden administration appears to have decided to build the new B61-13 nuclear bomb to persuade hardliners to get rid of the old B83-1 bomb.

The Trump administration had different interests, however, and its Nuclear Posture Review decided to retain the B83-1 (for reasons that remain unclear, and appear to have as much to do with undoing any decisions from the previous administration and little to do with military requirements or target sets) and leave the fate of the B61-11 unanswered.

When the Biden administration took over, its Nuclear Posture Review decided to proceed with retirement of the B83-1 but did not say anything about the B61-11. The Republican-controlled House did not agree and have used the years since to solicit hardline views that the B83-1 is somehow still needed.

Privately, however, Air Force and NNSA official disagreed. A high-yield gravity bomb is no longer needed and maintaining the B83-1 would cost a lot of money that could be better used elsewhere. Moreover, the NNSA production schedule is packed and adding a B83-1 life-extension program could jeopardize much more important programs. Although the B61-13 will add stress to this backlog, it will not increase the NNSA’s planned plutonium pit production schedule.

B61-13 Characteristics

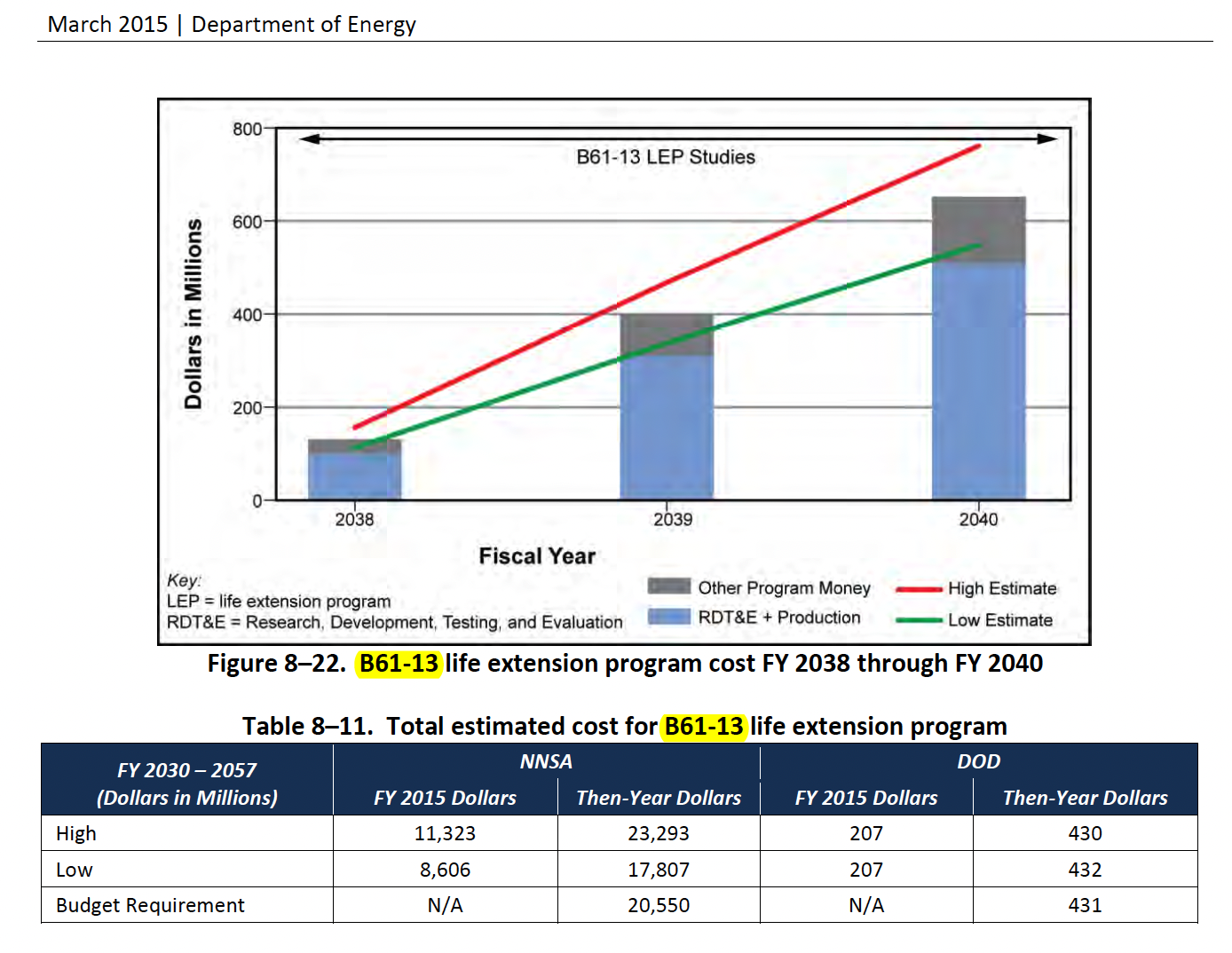

Confusingly, the name B61-13 has already been used for another nuclear weapon: the future bomb intended to replace the B61-12 in the late-2030s and 2040s. That weapon was first described in NNSA’s Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan in 2015 (see images below).

The B61-13 designation was previously given to another future nuclear bomb back in 2015.

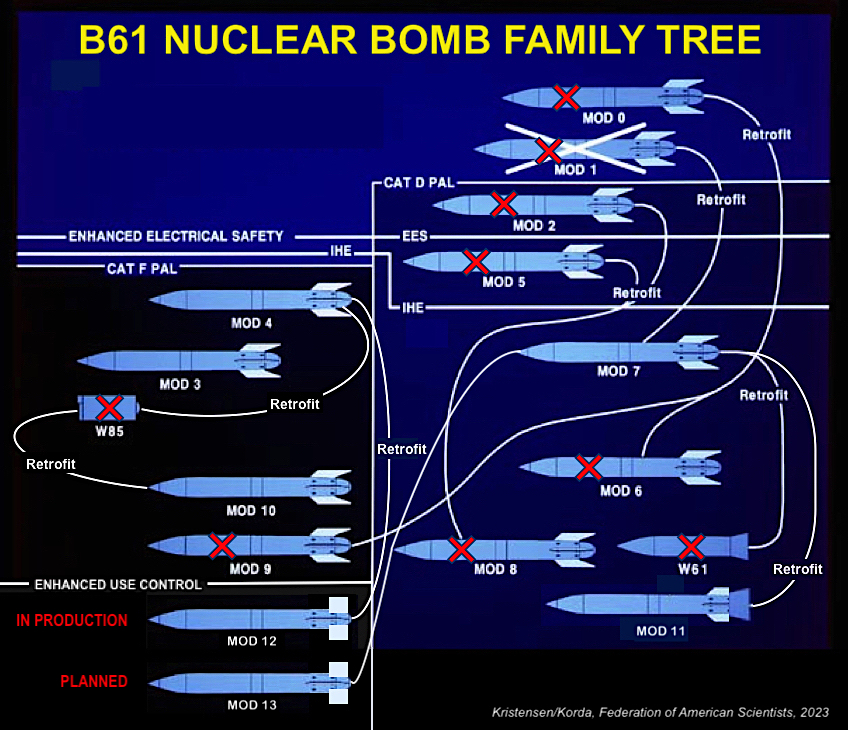

The new B61-13 bomb will be the 13th modification of the B61 warhead design (see image below). These modifications have varied in physical appearances, yields, safety and use-control features, and delivery platforms. Five of these modifications remain in the stockpile (B61-3/4/7/11/12).

The B61-13 will be the 13th modification of the original B61 bomb. It will use the warhead from the B61-7 but with enhanced use- and security features and a guided tail kit like the B61-12 to increase accuracy.

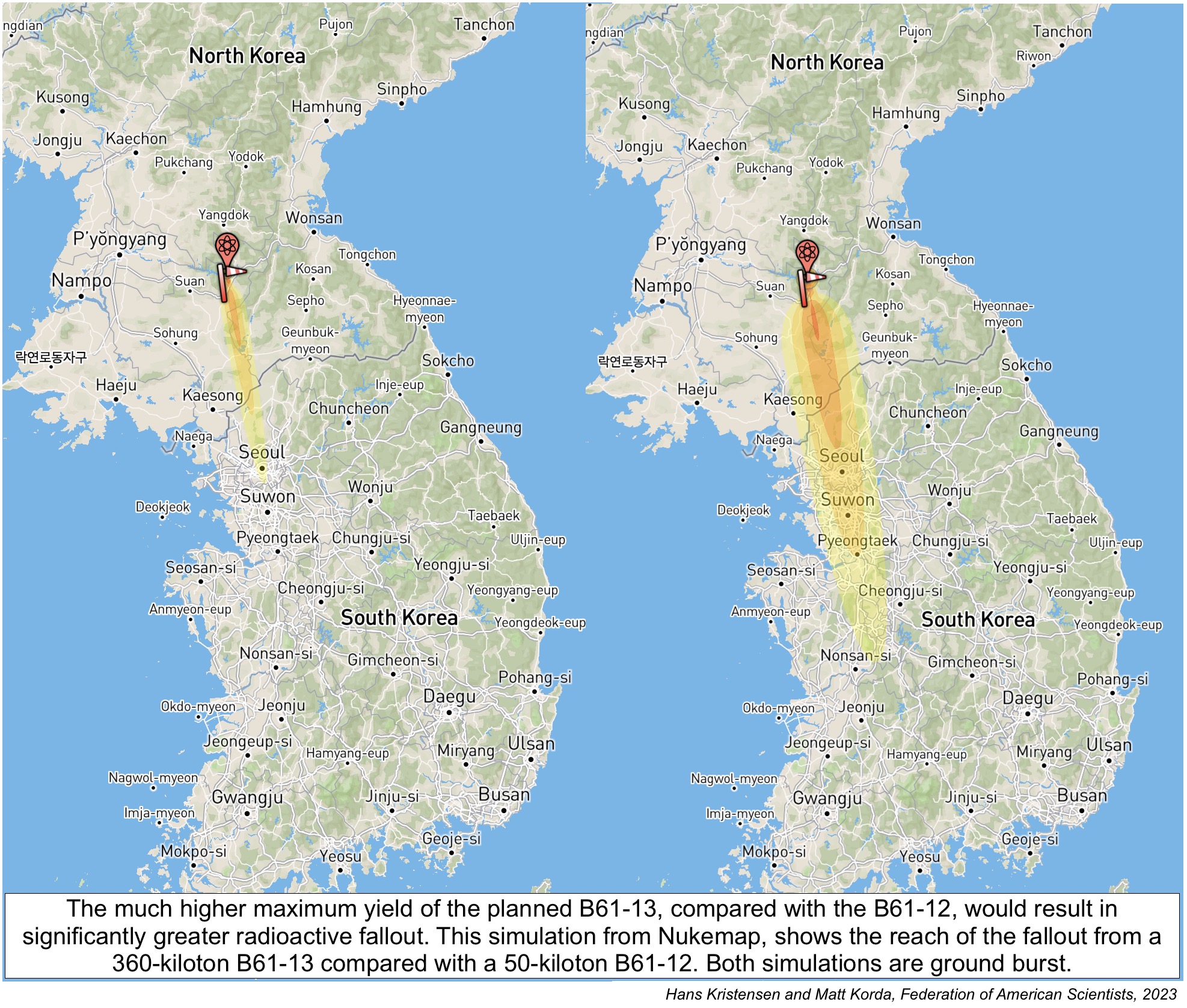

The B61-13 will have the same maximum yield as the B61-7 (360 kilotons), according to defense officials, a significant increase compared with the 50-kiloton B61-12 it is intended to supplement. If detonated on the surface, a yield of 360 kilotons would cause significant radioactive fallout over large areas.

The effects of a 360-kiloton explosion are significantly greater than those that would result from a 50-kiloton explosion. The following map compared the radioactive fallout from a ground burst detonation in North Korea. Depending on target location and weather conditions, the fallout from a B61-13 could reach half-way across South Korea (simulation from Nukemap).

Similar to the B61-12, the B61-13 will likely also have limited earth-penetration capabilities (through soft soil), which will be enhanced by the addition of the guided tail kit. Due to the phenomenon of ground-shock coupling, the B61-13’s relatively high yield and accuracy will likely enable the bomb to strike underground targets with yields equivalent to a surface-burst weapon of more than one megaton. The B61-13 will also have lower-yield options (see table below).

Although government officials insist that the B61-13 plan is not driven by new developments in adversarial countries or a new military targeting requirement, increasing the accuracy of a high-yield bomb obviously has targeting implications. Detonating the weapon closer to the target will increase the probably that the target is destroyed, and a very hard facility could hypothetically be destroyed with one B61-13 instead of two B61-12s. The DOD says the B61-13 will “provides us with additional flexibility” by “providing the President with additional options against certain harder and large-area military targets.”

Once the B61-12 and B61-13 are produced and stockpiled, the older versions replaced, and the B83-1 retired, the changes to the gravity weapons inventory will look something like this:

Although the B61-12 was previously said to also allow retirement of the B61-11 earth-penetrator, the B61-13 plan only appears intended to facilitate retirement of the B83-1. There is currently no life-extension program for the B61-11. The plan might be to allow it to age out. Officials say the B61-13 plan does not preclude that the United States potentially decides in the future to field a new nuclear earth-penetrator to replace the B61-11. But there is no decision on this yet.

Defense officials explain that the new B61-13 will not result in an increase of the overall number of warheads in the stockpile. The reason is that the administration plans to reduce the number of B61-12s produced by the number of B61-13s produced, so the total number of new bombs will ultimately be the same. The production plan for the B61-12 involved an estimated 480 bombs for both strategic bombers and dual-capable fighters. Since the bombers will now carry both B61-12 and B61-13 bombs (in addition to the new LRSO cruise missiles), and because the actual number of targets requiring a high-yield gravity bomb is probably small, it seems likely that the number of B61-13 bombs to be produced is very limited – perhaps on the order of 50 weapons – and that production will happen at the back end of the B61-12 schedule in 2025.

Unlike the B61-12s – of which a portion will be forward-deployed to Europe for use with NATO’s dual-capable aircraft – all of the B61-13s will be stored within the United States for use with the incoming B-21 bomber and the B-2 bomber (until it is replaced by the B-21). Nonetheless, because the B61-13 will use the same mechanical and electronic interface as the B61-12, the fighters that are destined to deliver the B61-12 will also be capable of delivering the B61-13. But the current plan is that the B61-13 is only for the bombers.

The B61-13 will look identical to the B61-12 (top) but use a much more powerful warhead from the B61-7. It is intended for delivery by bombers but can technically also be delivered by fighter jets (although that is not planned).

A Political Nuclear Bomb

The military justification for adding the B61-13 to the stockpile is hard to see. Instead, it seems more likely to be a political maneuver to finally get rid of the B83-1.

Defense officials say that the decision is not related to current events or developments in China, Russia, or other potential adversaries. Nor is the administration’s decision a product of the hard and deeply buried target capability study mentioned in the 2022 Nuclear Posture Review.

The B61-13 is a separate decision, they explain.

The military doesn’t need an additional, more powerful gravity bomb. In fact, Air Force officials privately say the military mission of nuclear gravity bombs is decreasing in importance because of the risk of putting bombers and their pilots in harm’s way over heavily defended targets – particularly as long-range missiles are becoming more capable.

To that end, the military mission of the B61-13 is somewhat of a mystery, especially given that the LRSO will also be arming the bombers and that the United States has thousands of other high-yield weapons in its arsenal.

Instead, what appears to have happened is this: after defense hardliners blocked the administration’s plans to retire the B83-1, the administration likely agreed to retain the B61-7 yield in the stockpile in the form of a modern bomb modification (B61-13) that is easier and cheaper to maintain, so that they can finally proceed with the retirement of the B83-1.

As such, the B61-13 will be the second “political” weapon in recent memory. The first was the low-yield W76-2 warhead fielded in late-2019 on the Trident submarines. The next one could be a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), if defense hawks have their way.

Additional Information

• US nuclear weapons, 2023

• The B61 Family of Nuclear Bombs

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Upgrade Underway for Russian Silos to Receive New Sarmat ICBM

New satellite imagery shows that preparations to deploy Russia’s new RS-28 Sarmat (SS-29) intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) are well underway.

However, the imagery also indicates that President Putin’s claims of deployment “in the near future” may be too optimistic. It is potentially possible that one or two missiles could be deployed early, but major construction is still ongoing at many of the silos in the first regiment and has not yet begun at all of them, and the completion of construction at all eventual Sarmat regiments may be over a decade away.

The Sarmat––which was originally scheduled to enter service between 2018 and 2020 and will replace Russia’s aging RS-20V Voevoda (SS-18) ICBM––had been subject to significant manufacturing, production, and testing delays. In January 2022, the “War Bolts” Telegram channel reported that flight tests for Sarmat had been postponed due to problems with the missile’s command module. Following Sarmat’s eventual first test flight on 20 April 2022, Putin announced that the new ICBM would enter combat duty by the end of the year. As of October 2023, however, only one additional Sarmat flight test had reportedly taken place (in February 2023) and, according to US officials, likely ended in failure.

Despite the lack of successful tests, in November 2022 the General Director of the Makeyev Rocket Design Bureau––responsible for the design of Sarmat––claimed that the missile had already entered serial production. On 1 September 2023, Roscosmos Chief Yury Borisov announced that Sarmat had “assumed combat alert posture,” although this was likely premature: on 5 October 2023, President Putin noted during his speech at the Valdai Club that some “administrative and bureaucratic procedures” still needed to be carried out before Sarmat could be placed on combat duty, and on 7 October 2023, the Russian Ministry of Defence noted on Telegram that the “final stages” of construction and installation were still underway at the first launch facilities and associated command post.

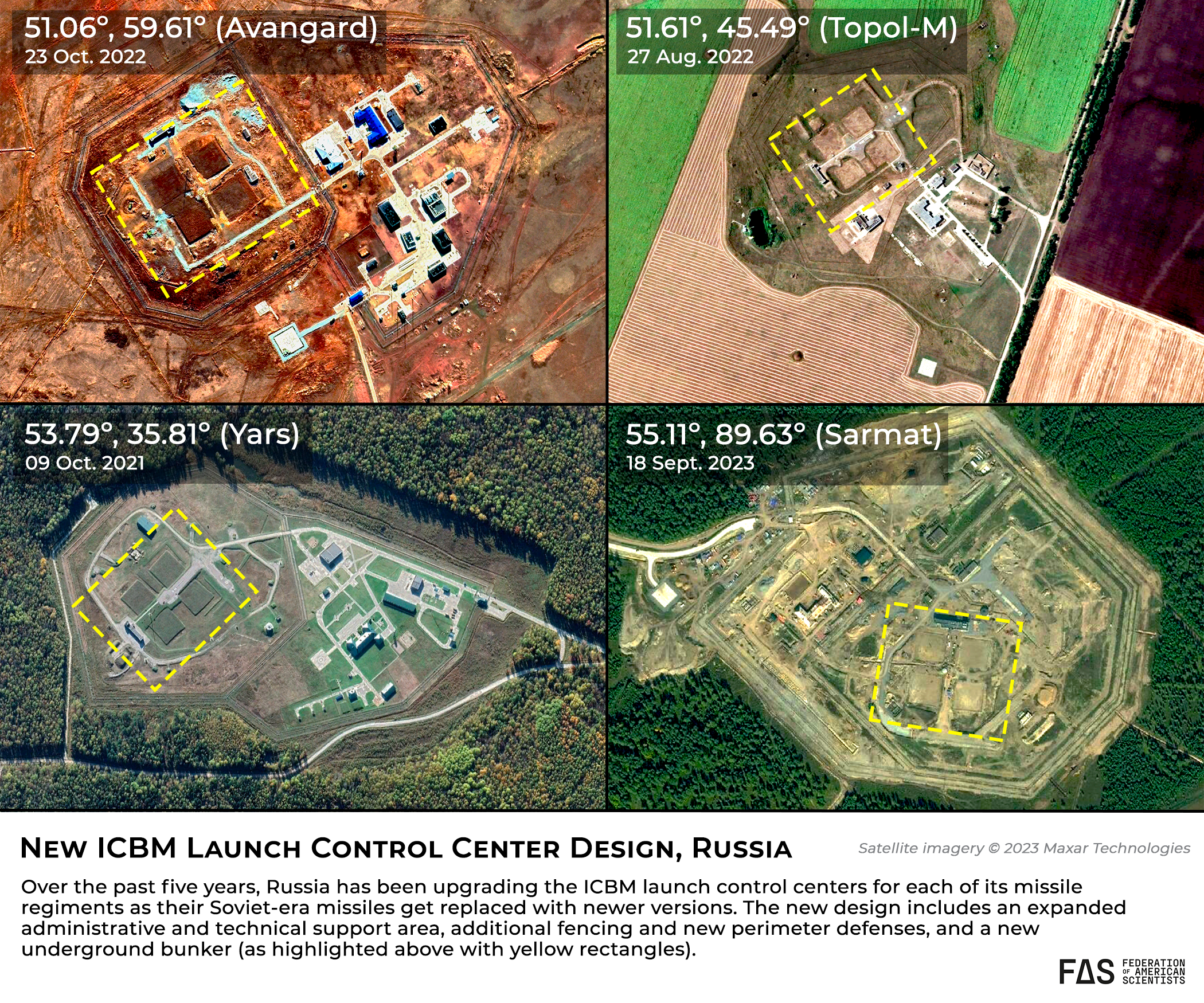

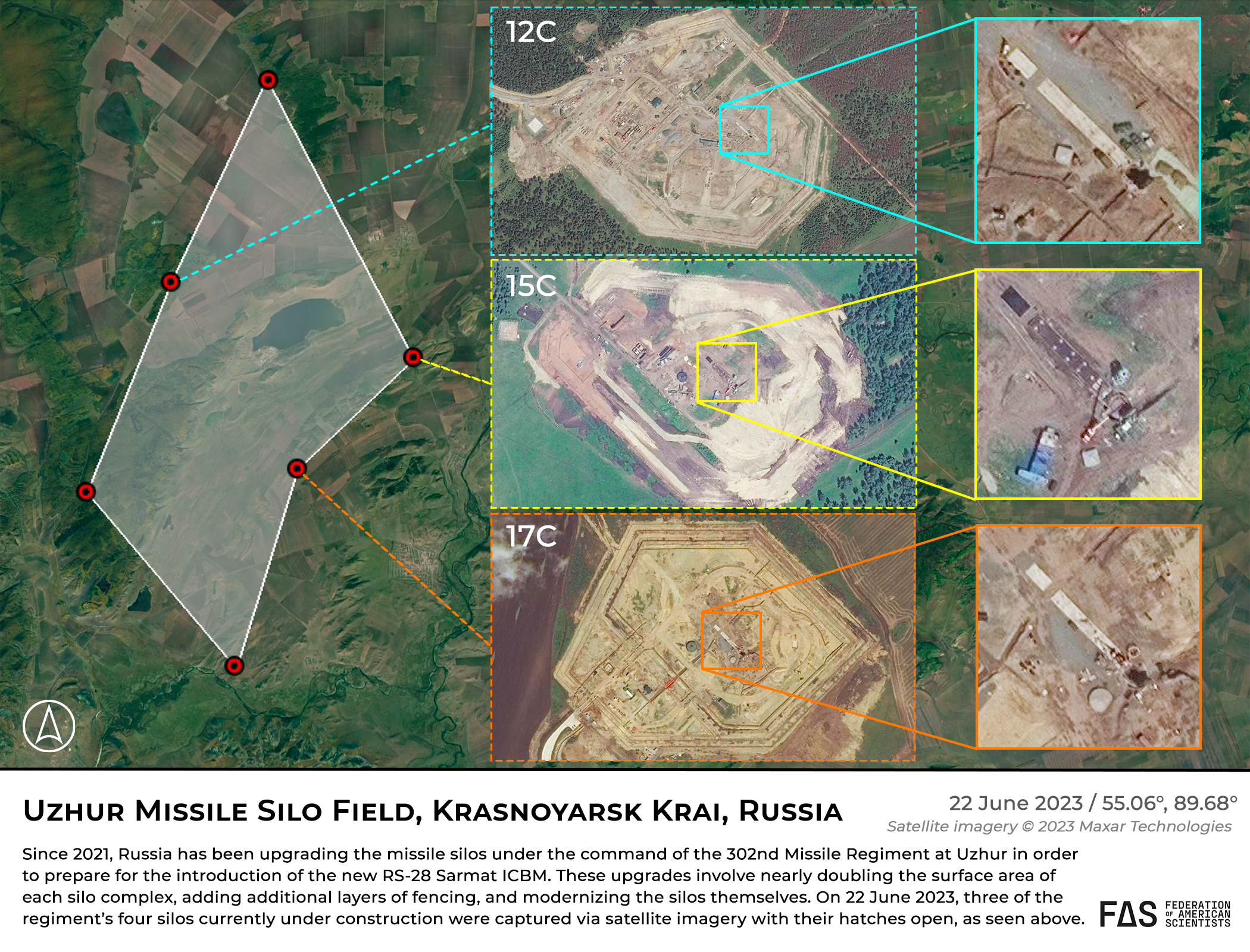

New satellite imagery indicates construction is well underway at the first regiment of the 62nd Missile Division near Uzhur in south Siberia. It is expected that a total of 46 Sarmat missiles will eventually be deployed with seven regiments (six missiles per regiment, plus one 10-missile regiment) in two divisions at Uzhur and Dombarovsky.

The first missile regiment undergoing its upgrade to Sarmat is the 302nd Missile Regiment and consists of six silos. Major construction continues at the launch control center and its accompanying silo (12C) and three other silos (13C, 15C, and 17C). The two remaining silos (16C and 18C) have only received minor upgrades and will take many months to complete if scheduled for the same comprehensive upgrade as the other silos.

Silos 12C and 17C:

The first two silos to begin their upgrades were Silos 12C (55.1144°, 89.6344°) and 17C (55.0347°, 89.7286°), which began their upgrades in the spring and summer of 2021, respectively. Over the past two years, the perimeters at both sites were removed, reshaped, and expanded with additional layers of fencing. The surface area of both silos has nearly doubled in size: Silo 12C has been expanded from approximately 0.228 square kilometers to 0.427 square kilometers, and the area of Silo 17C has been expanded from approximately 0.082 square kilometers to 0.136 square kilometers.

As of mid-September, construction appeared to be nearly complete inside the inner silo areas at both sites. The launch control center at Silo 12C has been upgraded to a newer LCC design that can also be seen at other Russian ICBM complexes, including the SS-27 Mod 1 “Topol-M” silo field near Tatishchevo, the SS-27 Mod 2 “Yars” silo field near Kozelsk, and the SS-19 Mod 4 “Avangard” silo field near Dombarovsky. In addition, Silo 12C boasts a new gun turret placement and expanded administrative area, although this outer area is not yet complete.

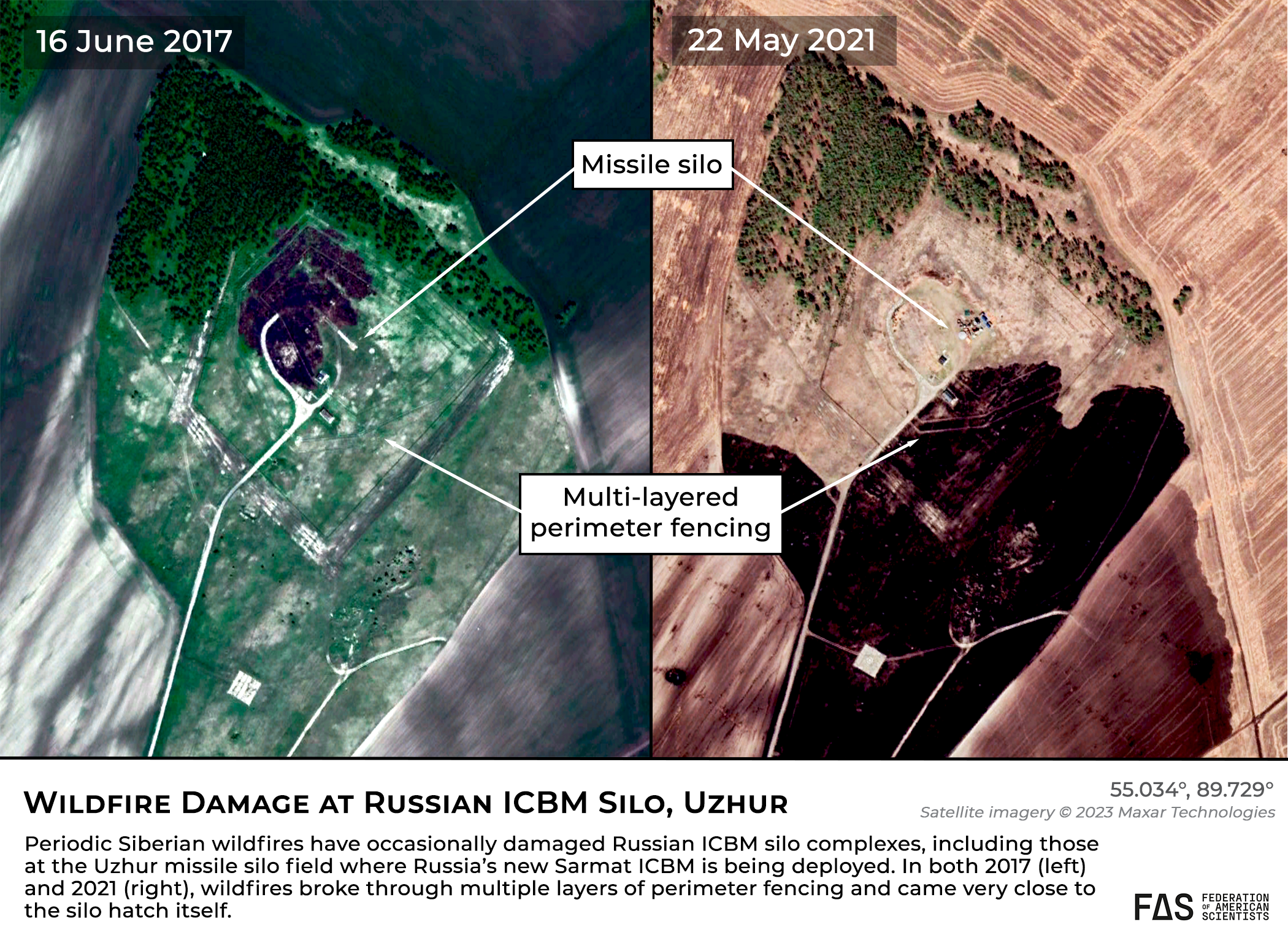

Notably, the immediate area surrounding Silo 17C has been subject to significant wildfire damage in the past. In 2017, a wildfire burned through all three sets of perimeter fencing and damaged the inner road leading to the silo hatch. In May 2021, another wildfire again burned through the three layers of fencing and appeared to damage an administrative building near the hatch.

Silos 13C and 15C:

Silos 13C (55.2008°, 89.7061°) and 17C (55.0822°, 89.8155°) began their upgrades in late-2022, nearly 1.5 years after construction on the first two silos began. As of mid-October 2023, significant construction at both sites was still underway, including underground and inside the silos themselves. Trees have been removed at both sites to make space for the expanded perimeter fences. While the new perimeters at both sites have been marked out, the multiple layers of fencing have not yet been completed. New gun turrets at both sites now appear to be in place.

Use the Planet Labs PBC interactive slider to compare before/after images.

Silos 16C and 18C:

As of mid-September 2023, full-site construction at Silos 16C (55.0247º, 89.5711º) and 18C (54.9501º, 89.6833º) had not yet begun, although some silo maintenance work has been visible since mid-2021, possibly in preparation for the full-site construction.

Open silos

It is notable that satellites have managed to capture images of all four silos currently under construction with their hatches open; on more than one occasion, multiple different silos could be seen with their hatches open on the same day, and in some cases hatches have stayed open for days at a time. This suggests that operations to upgrade the silos themselves and preparations to deploy Sarmat ICBMs inside them––as touted by high-ranking Russian officials––are well underway.

Additional information:

• Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons, 2023

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Strategic Posture Commission Report Calls for Broad Nuclear Buildup

On October 12th, the Strategic Posture Commission released its long-awaited report on U.S. nuclear policy and strategic stability. The 12-member Commission was hand-picked by Congress in 2022 to conduct a threat assessment, consider alterations to U.S. force posture, and provide recommendations.

In contrast to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the Congressionally-mandated Strategic Posture Commission report is a full-throated embrace of a U.S. nuclear build-up.

It includes recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase its number of deployed warheads, as well as increasing its production of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warhead production capacity. It also calls for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal.

The only thing that appears to have prevented the Commission from recommending an immediate increase of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile is that the weapons production complex currently does not have the capacity to do so.

The Commission’s embrace of a U.S. nuclear buildup ignores the consequences of a likely arms race with Russia and China (in fact, the Commission doesn’t even consider this or suggest other steps than a buildup to try to address the problem). If the United States responds to the Chinese buildup by increasing its own deployed warheads and launchers, Russia would most likely respond by increasing its deployed warheads and launchers. That would increase the nuclear threat against the United States and its allies. China, who has already decided that it needs more nuclear weapons to stand up to the existing U.S. force level (and those of Russia and India), might well respond to the U.S and Russian increases by increasing its own arsenal even further. That would put the United States back to where it started, feeling insufficient and facing increased nuclear threats.

Framing and context

The Commission’s report is generally framed around the prospect of Russian and Chinese strategic military cooperation against the United States. The Commission cautions against “dismissing the possibility of opportunistic or simultaneous two-peer aggression because it may seem improbable,” and notes that “not addressing it in U.S. strategy and strategic posture, could have the perverse effect of making such aggression more likely.” The Commission does not acknowledge, however, that building up new capabilities to address this highly remote possibility would likely kick the arms race into an even higher gear.

The report acknowledges that Russia and China are in the midst of large-scale modernization programs, and in the case of China, significant increases to its nuclear stockpile. This accords with our own assessments of both countries’ nuclear programs. However, the report’s authors suggest that these changes fundamentally call into question the United States’ assured retaliatory capabilities, and state that “the current U.S. strategic posture will be insufficient to achieve the objectives of U.S. defense strategy in the future….”

The Commission appears to base this conclusion, as well as its nuclear strategy and force structure recommendations, squarely on numerically-focused counterforce thinking: if China increases its posture by fielding more weapons, that automatically means the United States needs more weapons to “[a]ddress the larger number of targets….” However, the survivability of the US ballistic missile submarines should insulate the United States against needing to subscribe to this kind of thinking.

In 2012, a joint DOD/DNI report acknowledged that because of the US submarine force, Russia would not achieve any military advantage against the United States by significantly increasing the size of its deployed nuclear forces. In that 2012 study, both departments concluded that the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” [Emphasis added.] Why would this logic not apply to China as well? Although China’s nuclear arsenal is undoubtedly growing, why would it fundamentally alter the nature of the United States’ assured retaliatory capability while the United States is confident in the survivability of its SSBNs?

In this context, it is worth reiterating the words of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at the U.S. Strategic Command Change of Command Ceremony: “We all understand that nuclear deterrence isn’t just a numbers game. In fact, that sort of thinking can spur a dangerous arms race…deterrence has never been just about the numbers, the weapons, or the platforms.”

Force structure

Although the report says the Commission “avoided making specific force structure recommendations” in order to “leave specific material solution decisions to the Executive Branch and Congress,” the list of “identified capabilities beyond the existing program of record (POR) that will be needed” leaves little doubt about what the Commission believes those force structure decisions should be.

Strategic posture alterations

The Commission concludes that the United States “must act now to pursue additional measures and programs…beyond the planned modernization of strategic delivery vehicles and warheads may include either or both qualitative and quantitative adjustments in the U.S. strategic posture.”

Specifically, the Commission recommends that the United States should pursue the following modifications to its strategic nuclear force posture “with urgency:” [our context and commentary added below]

- Prepare to upload some or all of the nation’s hedge warheads; [these warheads are currently in storage; increasing deployed warheads above 1,550 is prohibited by the New START treaty (which expires in early-2026) and would likely cause Russia to also increase its deployed warheads.]

- Plan to deploy the Sentinel ICBM in a MIRVed configuration; [the Sentinel appears to be capable of carrying two MIRV but current plan calls for each missile to be deployed with just a single warhead]

- Increase the planned number of deployed Long-Range Standoff Weapons; [the Air Force currently has just over 500 ALCMs and plans to build 1,087 LRSOs (including test-flight missiles), each of which costs approximately $13 million]

- Increase the planned number of B-21 bombers and the tankers an expanded force would require; [the Air Force has said that it plans to purchase at least 100 B-21s]

- Increase the planned production of Columbia SSBNs and their Trident ballistic missile systems, and accelerate development and deployment of D5LE2; [the Navy currently plans to build 12 Columbia-class SSBNs and an increase would not happen until after the 12th SSBN is completed in the 2040s]

- Pursue the feasibility of fielding some portion of the future ICBM force in a road mobile configuration; [historically, any efforts to deploy road-mobile ICBMs in the United States have been unsuccessful]

- Accelerate efforts to develop advanced countermeasures to adversary IAMD; and

- Initiate planning and preparations for a portion of the future bomber fleet to be on continuous alert status, in time for the B-21 Full Operational Capability (FOC) date.” [Bombers currently regularly practice loading nuclear weapons as part of rapid-takeoff exercises. Returning bombers to alert would revert the decision by President H.W. Bush in 1991 to take bombers off alert. In 2021, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration stated that keeping the bomber fleet on continuous alert would exhaust the force and could not be done indefinitely]

Nonstrategic posture alterations

The Commission appears to want the United States to bolster its non-strategic nuclear forces in Europe, and begin to deploy non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific theater: “Additional U.S. theater nuclear capabilities will be necessary in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific regions to deter adversary nuclear use and offset local conventional superiority. These additional theater capabilities will need to be deployable, survivable, and variable in their available yield options.” Although the Commission does not explicitly recommend fielding either ground-launched theater nuclear capabilities or a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile for the Navy, it seems clear that these capabilities would be part of the Commission’s logic.

The United States used to deploy large numbers of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific region during the Cold War, but those weapons were withdrawn in the early 1990s and later dismantled as U.S. military planning shifted to rely more on advanced conventional weapons for limited theater options. Despite the removal of certain types of theater nuclear weapons after the Cold War, today the President maintains a wide range of nuclear response options designed to deter Russian and Chinese limited nuclear use in both regions––including capabilities with low or variable yields. In addition to ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-capable bombers operating in both regions, the U.S. Air Force has non-strategic B61 nuclear bombs for dual-capable aircraft that are intended for operations in both regions if it becomes necessary. The Navy now also has a low-yield warhead on its SSBNs––the W76-2––that was fielded specifically to provide the President with more options to deter limited scenarios in those regions. It is unclear why these existing options, as well as several additional capabilities already under development––including the incoming Long-Range Stand-Off Weapon––would be insufficient for maintaining regional deterrence.

The Commission specifically recommends that the United States should “urgently” modify its nuclear posture to “[p]rovide the President a range of militarily effective nuclear response options to deter or counter Russian or Chinese limited nuclear use in theater.” Although current plans already provide the President with such options, the Commission “recommends the following U.S. theater nuclear force posture modifications:

Develop and deploy theater nuclear delivery systems that have some or all of the following attributes: [our context and commentary added below]

- Forward-deployed or deployable in the European and Asia-Pacific theaters [The United States already has dual-capable fighters and B61 bombs earmarked for operations in the Asia-Pacific theaters, backed up by bombers with long-range cruise missiles];

- Survivable against preemptive attack without force generation day-to-day;

- A range of explosive yield options, including low yield [US nuclear forces earmarked for regional options already have a wide range of low-yield options];

- Capable of penetrating advanced IAMD with high confidence [F-35A dual-capable aircraft, the B-21 bomber, and air-launched cruise missiles are already being developed with enhanced penetration capabilities]; and

- Operationally relevant weapon delivery timeline (promptness) [the US recently fielded the W76-2 warhead on SSBNs to provide prompt theater capability in limited scenarios and is developing new prompt conventional missiles].”

Unlike U.S. low-yield theater nuclear weapons, the Commission warns that China’s development of “theater-range low-yield weapons may reduce China’s threshold for using nuclear weapons.” Presumably, the same would be true for the United States threshold if it followed the Commission’s recommendation to increase deployed (or deployable) non-strategic nuclear weapons with low-yield capabilities in the Indo-Pacific theater.

Strategy

Overall, the Commission suggests that current U.S. nuclear strategy is basically sound, but just needs to be backed up with additional weapons and industrial capacity. However, by not including recommendations to modify presidential nuclear employment guidance –– or even considering such an adjustment, which could reshape U.S. force posture to allow for decreased emphasis on counterforce targeting –– the Commission has limited its own flexibility to recommend any options other than simply adding more weapons.

Three scholars recently proposed a revised nuclear strategy that they concluded would reduce weapons requirements yet still be sufficient to adequately deter Russia and China. The central premise of reducing the counterforce focus is similar to a study that we published in 2009. In contrast, the Commission appears to have assumed an unchanged nuclear strategy and instead focused intensely on weapons and numbers.

The Commission report does not explain how it gets to the specific nuclear arms additions it says are needed. It only provides generic descriptions of nuclear strategy and lists of Chinese and Russian increases. The reason this translates into a recommendation to increase the US nuclear arsenal appears to be that the list of target categories that the Commission believes need to be targeted is very broad: “this means holding at risk key elements of their leadership, the security structure maintaining the leadership in power, their nuclear and conventional forces, and their war supporting industry.”

This numerical focus also ignores years of adjustments made to nuclear planning intended to avoid excessive nuclear force levels and increase flexibility. When asked in 2017 whether the US needed new nuclear capabilities for limited scenarios, then STRATCOM commander General John Hyten responded:

“[W]e actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, …I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the President on to give him options on what he would want to do… So I’m very comfortable today with the flexibility of our response options… And the reason I was surprised when I got to STRATCOM about the flexibility, is because the last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive, and that’s all there. We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing.”

While advocating integrated deterrence and a “whole of government” approach, the Commission nonetheless sets up an artificial dichotomy between conventional and nuclear capabilities: “The objectives of U.S. strategy must include effective deterrence and defeat of simultaneous Russian and Chinese aggression in Europe and Asia using conventional forces. If the United States and its Allies and partners do not field sufficient conventional forces to achieve this objective, U.S. strategy would need to be altered to increase reliance on nuclear weapons to deter or counter opportunistic or collaborative aggression in the other theater.”

Arms control

The Commission recommends subjugating nuclear arms control to the nuclear build-up: “The Commission recommends that a strategy to address the two-nuclear-peer threat environment be a prerequisite for developing U.S. nuclear arms control limits for the 2027-2035 timeframe. The Commission recommends that once a strategy and its related force requirements are established, the U.S. government determine whether and how nuclear arms control limits continue to enhance U.S. security.”

Put another way, this constitutes a recommendation to participate in an arms race, and then figure out how to control those same arms later.

The Commission report does acknowledge the importance of arms control, and notes that “[t]he ideal scenario for the United States would be a trilateral agreement that could effectively verify and limit all Russian, Chinese, and U.S. nuclear warheads and delivery systems, while retaining sufficient U.S. nuclear forces to meet security objectives and hedge against potential violations of the agreement.” (p.85) However, the prospect of this “ideal scenario” coming true would become increasingly unlikely if the United States significantly built up its nuclear forces as the Commission recommends.

Capacity and budget

The Commission recommends an overhaul and expansion of the nuclear weapons design and production capacity. That includes full funding of all NNSA recapitalization efforts, including pit production plans, even though the Government Accountability Office has warned that the program faces serious challenges and budget uncertainties. The Commission appears to brush aside concerns about the proposed pit production program.

Overall, the report does not seem to acknowledge any limits to defense spending. Amid all of the Commission’s recommendations to increase the number of strategic and tactical nuclear systems, there is almost no mention of cost in the entire report. Fulfilling all of these recommendations would require a significant amount of money, and that money would have to come from somewhere.

For example, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that developing the SLCM-N alone would cost an estimated $10 billion until 2030, not to mention another $7 billion for other tactical nuclear weapons and delivery systems. The amount of money it would take to field new systems, in addition to addressing other vital concerns such as IAMD, means funding would necessarily be cut from other budget priorities.

The true costs of these systems are not only the significant funds spent to acquire them, but also the fact that prioritizing these systems necessarily means deprioritizing other domestic or foreign policy initiatives that could do more to increase US security.

Implications for U.S. Nuclear Posture

The Strategic Posture Commission report is, in effect, a congressionally-mandated rebuttal to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, which many in Congress have critiqued for not being hawkish enough. The report does not describe in detail its methodology for how it arrives at its force buildup recommendations, and includes several claims and assumptions about nuclear strategy that have been critiqued and called into question by recent scholarship. In some respects, it reads more like an industry report than a Congressionally-mandated study.

While the timing of the report means that it is unlikely to have a significant impact on this year’s budget cycle, it will certainly play a critical role in justifying increases to the nuclear budget for years to come.

From our perspective, the recommendations included in the Commission report are likely to exacerbate the arms race, further constrict the window for engaging with Russia and China on arms control, and redirect funding away from more proximate priorities. At the very least, before embarking on this overambitious wish list the United States must address any outstanding recommendations from the Government Accountability Office to fix its planning and budgeting processes, otherwise it risks overloading the assembly line even more.

In addition, the United States could consider how modified presidential employment guidance might enable a posture that relies on fewer nuclear weapons, and adjust accordingly.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Nuclear Notebook: Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2023

The FAS Nuclear Notebook is one of the most widely sourced reference materials worldwide for reliable information about the status of nuclear weapons and has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists since 1987. The Nuclear Notebook is researched and written by the staff of the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project: Director Hans M. Kristensen, Senior Research Fellow Matt Korda, and Research Associate Eliana Johns.

This issue’s column finds that Pakistan is continuing to gradually expand its nuclear arsenal with more warheads, more delivery systems, and a growing fissile material production industry. We estimate that Pakistan now has a nuclear weapons stockpile of approximately 170 warheads.

Read the full “Pakistan Nuclear Weapons, 2023” Nuclear Notebook in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, or download a PDF using the button on the left side of this page. The complete archive of FAS Nuclear Notebooks can be found here.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Culture Blast at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum

Charlotte Yeung is a Purdue student and New Voices in Nuclear Weapons fellow at FAS. Her multimedia show, Culture Blast, opens this week at the Kurt Vonnegut Museum in Indianapolis.

Best known for his anti-war novel Slaughterhouse-Five (1969), Kurt Vonnegut’s experience serving in World War II informed his work and his life. He acted as a powerful spokesman for the preservation of our Constitutional freedoms, for nuclear arms control, and for the protection of the earth’s fragile biosphere throughout the 1980s and 1990s. He remained engaged in these issues throughout his life.

FAS: Tell us about this project and its goals…

Charlotte: My exhibit, Culture Blast, weaves Kurt Vonnegut’s stance on nuclear weapons with current issues we face today. It serves as a space for preservation and linkage, asking the viewer to connect Vonnegut’s concerns to the modern day. It is also a place of artistic protest and education, meant to inform the viewer of the often ignored complexity of nuclear weapons and how they affect many different parts of society. I worked with Lovely Umayam and the team at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) to ideate and research what underpins this exhibit.

Why this medium?

I explore nuclear history and literary protest through blackout poetry, free verse, and digital illustration – contemporary forms of written and visual art that carries on Vonnegut’s artistic protest into the modern day.

In particular, I wanted to create art that can be accessible to everyone and not just people who go to the museum. Seeing a photo of a pencil drawing or a statue online is experiencing just the surface-level nature of a work of art. It lacks the other sensory components like seeing how the art fits with the wider space and how others react to it. A similar issue comes up if my poems were spoken word. That art form lives off of a crowd. My digital art and poetry is meant to be seen in both a museum setting and online setting. Viewers can watch a time lapse of my art and see the process of creating this work. The poetry is meant to be read rather than performed.

Can you share some of the backstory on a few of the multimedia pieces? How did the concept evolve as you worked on them?

My favorite pair in the collection is Sketch 1 (the typewriter) and the blackout poem Protection in the name of public interest. I drew Vonnegut on his typewriter because I felt this to be the most symbolic image of his artistic protest. Though he wrote and sketched on countless personal notebooks, his work commenting on nuclear weapons can be found in some of his published stories. Vonnegut turned to his literary creativity to reflect on nuclear weapons, in particular scientists’ indifference to the suffering caused by the atom bomb, as seen in works such as Cat’s Cradle and Report on The Barnhouse Effect.

The uncensored version of my poem (Protection in the name of public interest) meditates on the bomb’s harm and also the long association between science and violence. I chose to create a blackout poem because in the immediate aftermath of World War II, the American government censored many of the photos and stories about what happened to the people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in effect erasing the lived experience of these people. It wasn’t until writer John Hersey’s account of the U.S. nuclear attacks, titled Hiroshima, was published in The New Yorker in 1946 that the American public had an uncensored understanding of what had happened in Japan.

In terms of the process, I began this thinking that I would draw a hand and a pencil but Vonnegut is strongly associated with his typewriter so I felt that it wouldn’t be as accurate to draw something else. I knew I would write a blackout poem and link it to censorship but I wasn’t sure what it would be called or what it would say. I ultimately wrote how I felt about the exhibit and what I’ve learned so far in the FAS fellowship and what I wanted to convey. I started blacking out the poem and left the main themes I wanted viewers to have from this exhibit.

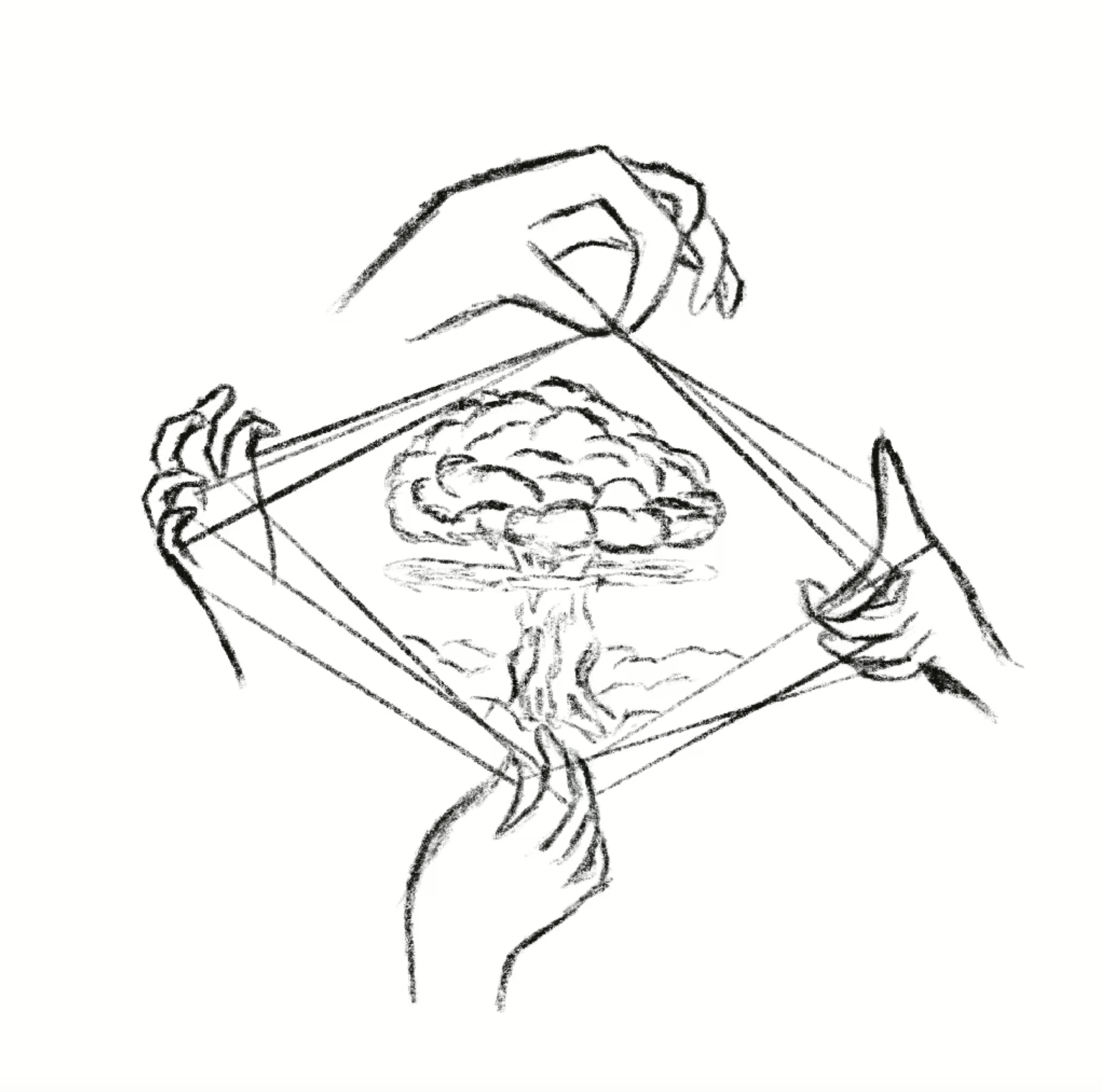

I am very fond of Sketch 2 (the cat’s cradle with the mushroom cloud inside) and the poem Labels. Labels was inspired by a lunch I had last year with a hibakusha, Yoshiko Kajimoto. She was 14 when the bomb fell and she spoke of the following days in vivid detail. I believe it was her testimony in particular that started me on this path towards researching the societal implications of nuclear weapons.

I drew an artistic interpretation of a cat’s cradle seeking to capture a mushroom cloud to communicate the concept of hyperobjects. According to Timothy Morton, a hyperobject is a real event or phenomenon so vast that it is beyond human comprehension. Nuclear weapons are an example of a hyperobject – its existence and use has had devastating ramifications touching different aspects of life that may be hard to fully comprehend all at once.

Nuclear weapons are both deeply present and hidden. On one hand, nuclear weapons are a constant security threat and have left deep scars on cities and bodies ranging from people in Japan to Utah downwinders. On the other hand, some of the information around them is clouded in mystery, and censored by different governments. Nuclear and fallout shelters built for nuclear warfare are considered to be Cold War relics; in the United States, they are largely abandoned or hidden, tucked in the basements of homes and schools, or located far out in the countryside away from cities. Some nuclear bunkers are parking lots in New York City and rumored rooms in DC. Secrecy and hidden locality are reasons why there isn’t as much widespread public knowledge or understanding of nuclear weapons.

Why is nuclear weapon risk a conversation we’re still having today? Where can people new to this issue learn more?

As a young person, I encounter many people my age who ask me why I care about nuclear weapons and why they matter in this day and age. It is, in a sense, meaningless to them. The violence of the bomb cannot be completely understood without hearing about the pain it wrought on people who experienced it firsthand. From burning skin and bodies to radiation poisoning, nuclear weapons have left permanent physical and psychological scars that are rarely spoken about, but have affected generations of families and communities.

I suggest reading more about what happened to individual A-bomb survivors to truly understand the effects of nuclear weapons. Humanizing those affected by war combats the practice of minimizing lives and experience to death counts. Great works to look at include Barefoot Gen (a manga on the Hiroshima bombings inspired by the hibakusha author’s experience), Grave of the Fireflies (a film about children grappling with the effects of the bombing), and the poem Bringing Forth New Life (生ましめんかな) by hibakusha poet Sadako Kurihara (which is about a woman giving birth in the ruins while the midwife dies from injuries in the middle of the process).

I knew the design from the beginning. It had to be a cat’s cradle because Vonnegut equates scientific irreverence to the bomb’s humanitarian effects to a cat’s cradle (an essentially useless game of moving strings with your fingers). The poem centers around hyperobjects, a term I grappled with in a university seminar with Dr. Brite from Purdue’s Honors College. I had never heard of the term before that class but I thought it was fitting for something like nuclear weapons. My research is interdisciplinary in nature and it seeks to analyze the cultural aspects of nuclear weapons that aren’t traditionally used by the political science community.

The third piece I’ll discuss is Sketch 5 and Rebuilding. This sketch of a rose is reminiscent of the Duftwolke roses sent from Germany to Hiroshima after the war as a symbol of rebuilding. It is also symbolic of Vonnegut’s experiences in World War II. He was caught in the firestorm that engulfed Dresden and he sheltered in a slaughterhouse. As one of the remaining survivors, he was forced to burn dead bodies in the aftermath. Vonnegut became an anti-war activist as a result of this experience. He also wrote Slaughterhouse-Five a book that grapples with trauma and PTSD after war. His writing was his way of finding closure and rebuilding, hence the title of the poem.

I wanted to end this collection on an optimistic note because, as dark and grim as war and nuclear weapons can be, there is great resilience in humanity. It takes monumental courage and hope to rebuild a city or mind or soul after facing the devastation of an all-consuming weapon.