Introducing Certification of Technical Necessity for Resumption of Nuclear Explosive Testing

The United States currently observes a voluntary moratorium on explosive nuclear weapons testing. At the same time, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) is required by law to maintain the capability to conduct an underground nuclear explosive test at the Nevada National Security Site, if directed to do so by the U.S. president.

Restarting U.S. nuclear weapons testing could have very negative security implications for the United States unless it was determined to be an absolute technical or security necessity. A restart of U.S. nuclear testing for any reason could open the door for China, Russia, Pakistan, and India to do the same, and make it even harder to condemn North Korea for its testing program. This would have significant security consequences for the United States and global environmental impacts.

The United States conducted over 1,000 nuclear weapons tests before the 1991 testing moratorium took effect. It was able to do so with the world’s most advanced diagnostic and data detection equipment, which enabled the US to conduct advanced computer simulations after the end of testing. Neither Russia or China conducted as many tests, and many fewer of those were able to collect advanced metrics, hampering these countries’ ability to match American simulation capabilities. Enabling Russia and China to resume testing could narrow the technical advantage the United States has held in testing data since the testing moratorium went into effect in 1992.

Aside from the security loss, nuclear testing would also have long-lasting radiological effects at the test site itself, including radiation contamination in the soil and groundwater, and the chance of venting into the atmosphere. Despite these downsides, a future president has the legal authority—for political or other reasons—to order a resumption of nuclear testing. Ensuring any such decision is more democratic and subject to a broader system of political accountability could be achieved by creating a more integrated approval process, based on scientific or security needs. To this end, Congress should pass legislation requiring the NNSA administrator to certify that an explosive nuclear test is technically necessary to rectify an existing problem or doubt in U.S. nuclear surety before a test can be conducted.

Challenges and Opportunities

The United States is party to the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty, which prohibits atmospheric tests, and the Threshold Ban Treaty of 1974, limiting underground tests of more than 150 kilotons of explosive yield. In 1992, the United States also established a legal moratorium on nuclear testing through the Hatfield-Exon-Mitchell Amendment, passed during the George H.W. Bush Administration. After extending this moratorium in 1993, the United States, Russia, and China also signed the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) in 1996, which prohibits nuclear explosions. However, none of the Annex 2 (nuclear armed) states have ratified the CTBT, which prevents it from entering into force.

Since halting nuclear explosive tests in 1992, the United States has benefited from a comparative advantage over other nuclear-armed states, given its advanced simulation and computing technologies, coupled with extensive data collected from conducting over 1,000 explosive nuclear tests over nearly five decades. The NNSA’s Stockpile Stewardship Program uses computer simulations to combine new scientific research with data from past nuclear explosive tests to assess the reliability, safety, and security of the U.S. stockpile without returning to nuclear explosive testing. Congress has mandated that the NNSA must provide a yearly report to the Nuclear Weapons Council, which reports to the president on the reliability of the nuclear weapons stockpile. The NNSA also maintains the capability to test nuclear weapons at the Nevada Test Site as directed by President Clinton in Presidential Decision Directive 15 (PDD-15). National Security Memorandum 7 requires the NNSA to have the capability to conduct an underground explosive test with limited diagnostics within 36 months, but the NNSA has asserted in their Stockpile Stewardship and Management plan that domestic and international laws and regulations could slow down this timeline. A 2011 report to Congress from the Department of Energy stated that a small test for political reasons could take only 6–10 months.

For the past 27 years, the NNSA administrator and the three directors of the national laboratories have annually certified—following a lengthy assessment process—that “there is no technical reason to conduct nuclear explosive testing.” Now, some figures, including former President Trump’s National Security Advisor, have called for a resumption of U.S. nuclear testing for political reasons. Specifically, testing advocates suggest—despite a lack of technical justification—that a return to testing is necessary in order to maintain the reliability of the U.S. nuclear stockpile and to intimidate China and other adversaries at the bargaining table.

A 2003 study by Sandia National Laboratories found that conducting an underground nuclear test would cost between $76 million and $84 million in then-year dollars, approximately $132 million to $146 million today. In addition to financial cost, explosive nuclear testing could also be costly to both humans and the environment even if conducted underground. For example, at least 32 underground tests performed at the Nevada Test Site were found to have released considerable quantities of radionuclides into the atmosphere through venting. Underground testing can also lead to contamination of land and groundwater. One of the most significant impacts of nuclear testing in the United States is the disproportionately high rate of thyroid cancer in Nevada and surrounding states due to radioactive contamination of the environment.

In addition to health and environmental concerns, the resumption of nuclear tests in the United States would likely trigger nuclear testing by other states—all of which would have comparatively more to gain and learn from testing. When the CTBT was signed, the United States had already conducted far more nuclear tests than China or Russia with better technology to collect data, including fiber optic cables and supercomputers. A return to nuclear testing would also weaken international norms on nonproliferation and, rather than coerce adversaries into a preferred course of action, likely instigate more aggressive behavior and heightened tensions in response.

Plan of Action

In order to ensure that, if resumed, explosive nuclear testing is done for technical rather than political reasons, Congress should amend existing legislation to implement checks and balances on the president’s ability to order such a resumption. Per section 2530 of title 50 of the United States Code, “No underground test of nuclear weapons may be conducted by the United States after September 30, 1996, unless a foreign state conducts a nuclear test after this date, at which time the prohibition on United States nuclear testing is lifted.” Congress should amend this legislation to stipulate that, prior to any nuclear test being conducted, the NNSA administrator must first certify that the objectives of the test cannot be achieved through simulation and are important enough to warrant an end to the moratorium. A new certification should be required for every individual test, and the amendment should require that the certification be provided in the form of a publicly available, unclassified report to Congress, in addition to a classified report. In the absence of such an amendment, the president should make a Presidential Decision Directive to call for a certification by the NNSA administrator and a public hearing under oath to certify the same results cannot be achieved through scientific simulation in order for a nuclear test to be conducted.

Conclusion

The United States should continue its voluntary moratorium on all types of explosive nuclear weapons tests and implement further checks on the president’s ability to call for a resumption of nuclear testing.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

Geolocating China’s Unprecedented Missile Launch: The Potential What, Where, How, and Why

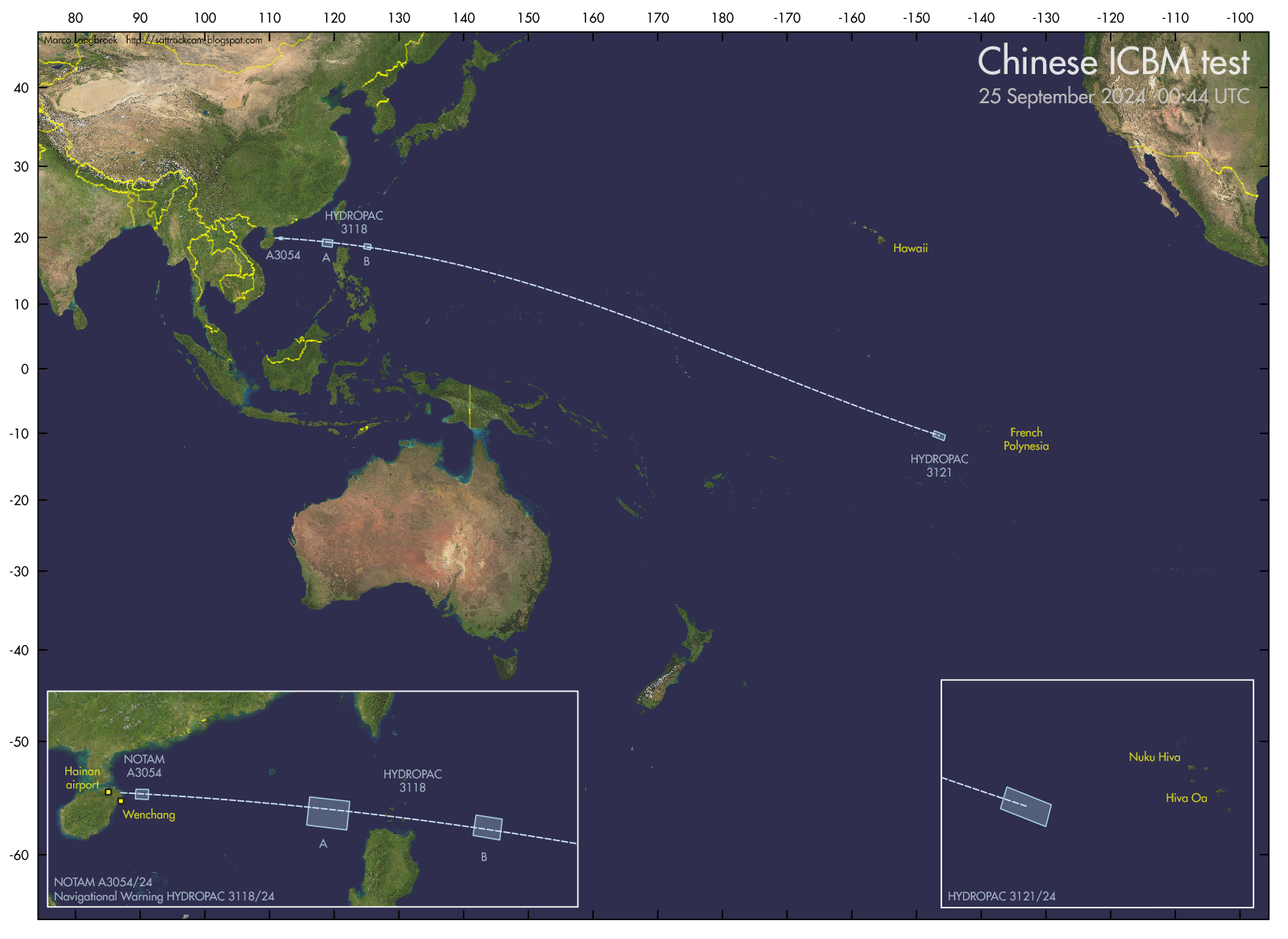

On September 25, 2024, the Chinese Ministry of National Defence announced that the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) had test-launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) into the South Pacific. The announcement stated that this was a “routine arrangement in [their] annual training plan.” However, the ICBM was launched from Hainan Island, an unusual location for this kind of missile. In addition, the reentry vehicle impacted in the South Pacific, an estimated 11,700 km away, marking the first time China had targeted the Pacific in a test since 1980 when it tested its first ICBM (the DF-5) at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center.

This map, created by Dr. Marco Langbroek (@Marco_Langbroek on X), shows hazard areas from Navigational Warnings and a NOTAM with the reconstructed ballistic flight path. (source)

Given the unusual nature of this test launch and the lack of official information about the status of China’s nuclear forces, this event is an opportunity to further examine China’s nuclear posture and activities, including the type of missile, how it fits into China’s nuclear modernization, and where it was launched from.

What missile is it?

When news of the launch broke, navigational warnings and trajectory calculations indicated the missile was launched from northeast Hainan Island, a Chinese province in the South China Sea. This is not where China normally test-launches its ICBMs, and there is no ICBM brigade permanently deployed on the island. The location and the range of the missile indicated that it was a road-mobile missile launcher, either a DF-41 or DF-31A/AG type. In the days after the launch, several images surfaced with clues about the type of missile and its potential launch location.

An image of the missile lauch released by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army on September 25, 2024.

The first image, released by news outlets on September 25, showed features that made it clear that this was, in fact, a DF-31AG missile. The DF-31AG is a modernized version of China’s first solid-fuel road-mobile ICBM, the DF-31, which debuted in 2006. Since 2007, China has been supplementing and now completely replaced the initial DF-31 versions with the longer-range DF-31A. The DF-31A launcher had limited maneuverability, so in 2017, China first displayed the enhanced DF-31AG launcher. The DF-31AG will likely completely replace the DF-31A in the next few years.

The DF-31AG launcher is thought to carry the same missile as the DF-31A, but the 21-meter-long eight-axle HTF5980 transporter erector launcher has improved maneuverability and is thought to require less support. The single erector arm seen in the above image matches other images of the DF-31AG. The image seems to show that the launcher was partially covered by some sort of camouflage during the launch.

The DF-31AG uses a cold-launch method, meaning the missile is ejected from the canister using compressed gas or steam before the first-stage engine ignites. Unfortunately, this also means it is harder to geolocate the site of the launch because there are unlikely to be burn marks that would normally remain visible on the ground after hot-launching a missile.

How did the missile get there?

The nearest deployment of DF-31AG missiles is with the 632 Brigade located in Shaoyang in mainland China, around 800 km away. There is no confirmation that the missile came from this particular brigade, but the distance gives some perspective as to the process and amount of time it takes to bring a DF-31AG to Hainan Island.

To transport the mobile ICBM to Hainan, it was likely placed onto a railcar and brought to a port such as Yuehai Railway Beigang Wharf before being loaded onto a ship and transferred to Haikou port or a similar location at Hainan Island. From there, the missile was likely driven, along with the accompanying support vehicles, to a sheltered and protected area near the final launch location.

It remains unknown whether the missile was launched directly from the launch position itself, remotely from a local command post, or remotely from a centralized authority.

Where was the missile launched from?

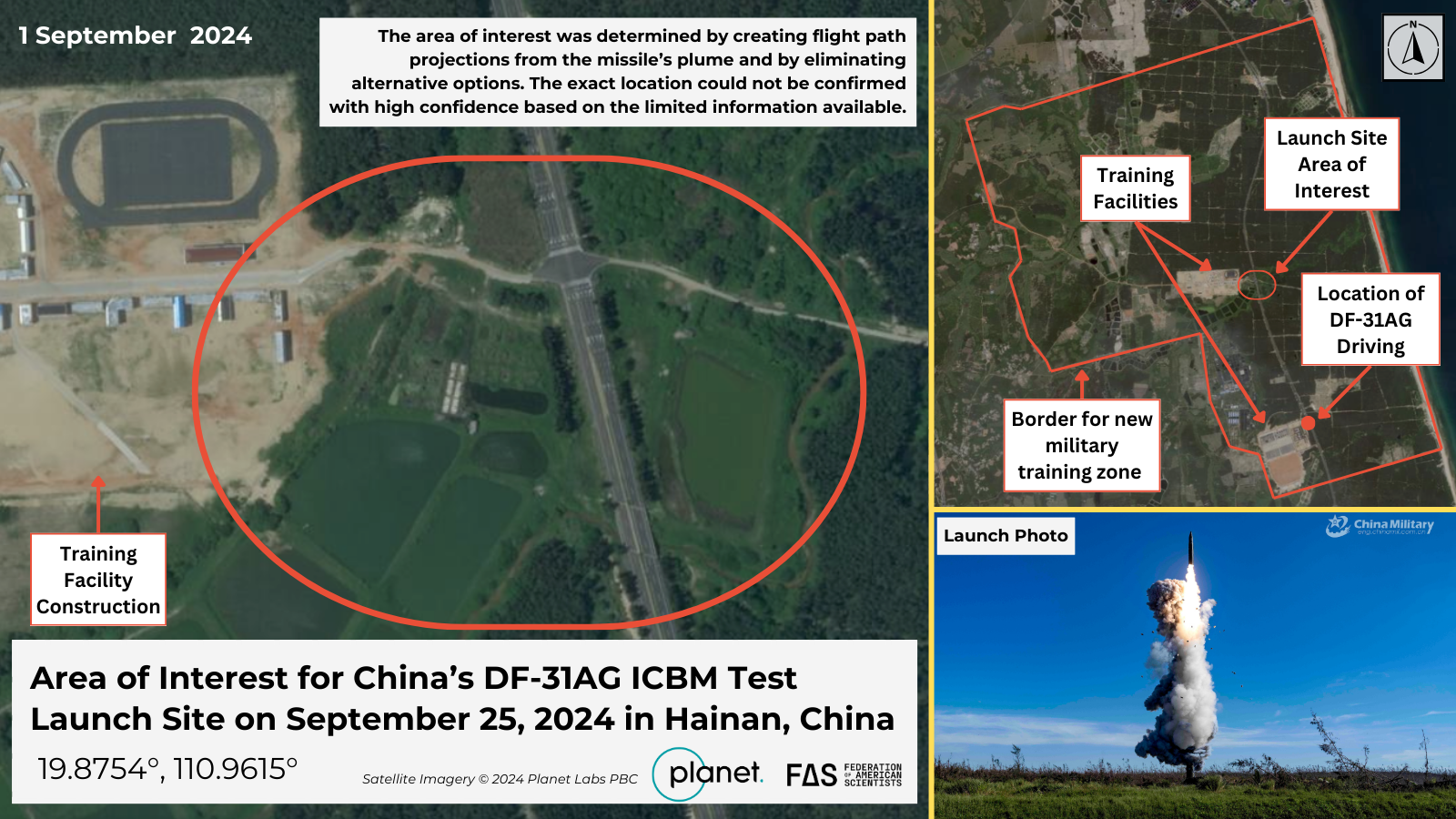

To find the precise location where the DF-31AG was launched on the island, we had to rely on the few photos and videos available to us (mostly captured by locals). To do this, we collaborated with analyst Ise Midori (@isekaimint on X), who carried out a complex analysis of the various launch videos to pinpoint the approximate launch location.

In the above image of the launch, one of the first noticeable features is the devastated vegetation, which matches what we would expect to see after typhoon Yagi impacted northeast Hainan in early September. There is also a small body of water barely visible at the bottom right of the image, which provides a clue when searching for the launch location.

After analyzing the available images, photos, and videos, Midori determined the general area where the launch likely occurred to be in Wenchang, Hainan. While we are unable to determine the exact location with high confidence due to a lack of clearly identifiable signatures, we expect it to be within the area of interest indicated below, potentially at the highway intersection.

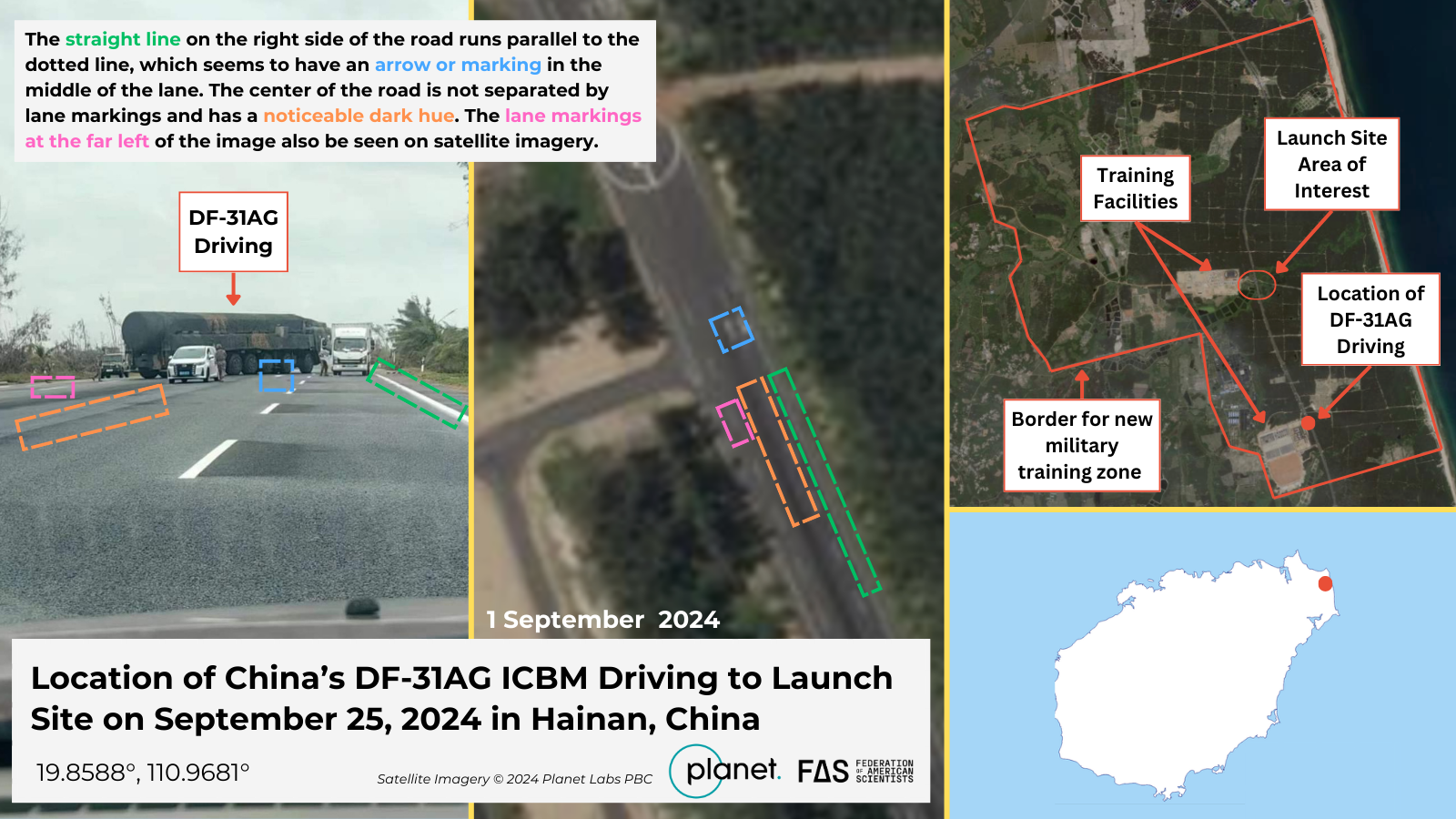

Meanwhile, the image below began circulating on social media shortly after the launch. The image reportedly captures the DF-31AG as it was driving to its launch position, although the cloud coverage does not match that from the photo of the launch and could have been taken hours beforehand.

An image of the DF-31AG missile driving on Hainan Island that circulated on social media shortly after the launch.

After observing the road markings and vegetation in the image, satellite imagery from Planet Labs PBC revealed a unique road that matched these signatures. This road is also only 1.9 km away from the launch location area of interest, increasing confidence that the launch occurred at or near this area.

Notably, both the launch area of interest and the location of the DF-31AG on the road are within the boundaries of what seems to be a new military training zone constructed in recent years. This also helps increase confidence in the launch area of interest and highlights this area as important for future observation.

Why here, and why now?

While China has not test-launched an ICBM into the Pacific in over four decades (it normally test launches the missiles in a very high apogee within its borders), it is not unusual for China – or other countries for that matter – to test-launch their nuclear-capable systems. It is interesting, however, to consider why China may have chosen to launch from Hainan Island instead of somewhere that is operationally representative or perhaps easier to travel to on the mainland coast. Nevertheless, the location allows China to fly the missile at full range without dropping missile stages on the ground or overflying other countries. It is unknown whether China will test-launch more ICBMs from Hainan Island in the future.

These types of tests also take months of extensive planning and coordination. Thus, the launch was likely motivated by broader political factors, not in response to particular recent events. Tong Zhao, Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, points out that this test was crucial for the PLARF to reestablish its internal and external credibility following corruption scandals and unprecedented leadership shifts. Additionally, reports of issues with the quality of certain missiles likely prompted a desire to reestablish recognition of operational competence.

Further, because the PLARF conducted the test launch as part of a “military drill” rather than a technological development program, it likely aims to convey military prowess and combat readiness. Conducting an ICBM test over the ocean also likely reflects China’s ambition to solidify its international status as a major nuclear power since the United States also regularly tests its ICBMs over the open ocean.

Notably, the Pentagon confirmed they received advanced notice of China’s test launch, which potentially sets a precedent for pre-launch notification and could leave room for further communication on risk reduction measures. Moving forward, it will be interesting to see if China begins to routinely conduct these kinds of tests beyond its borders and if it continues to provide pre-launch notification to relevant states. The new DF-41 has yet to be test-flown at full range in a realistic trajectory.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

NATO Tactical Nuclear Weapons Exercise And Base Upgrades

NATO chose to use a Dutch F-35A as illustration in the press release for its tactical nuclear weapons exercise Steadfast Noon.

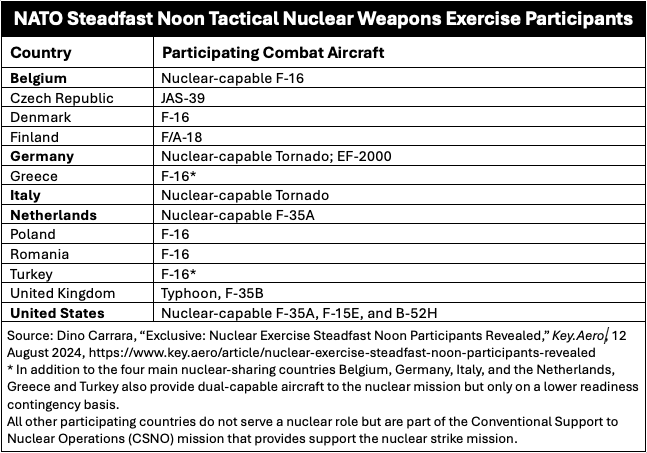

NATO today began its annual tactical nuclear weapons exercise in Europe. Known as Steadfast Noon, the two-week long exercise involves more than 60 aircraft from 13 countries and more than 2,000 personnel, according to a NATO press release. That is slightly bigger than last year’s exercise that involved “up to 60” aircraft.

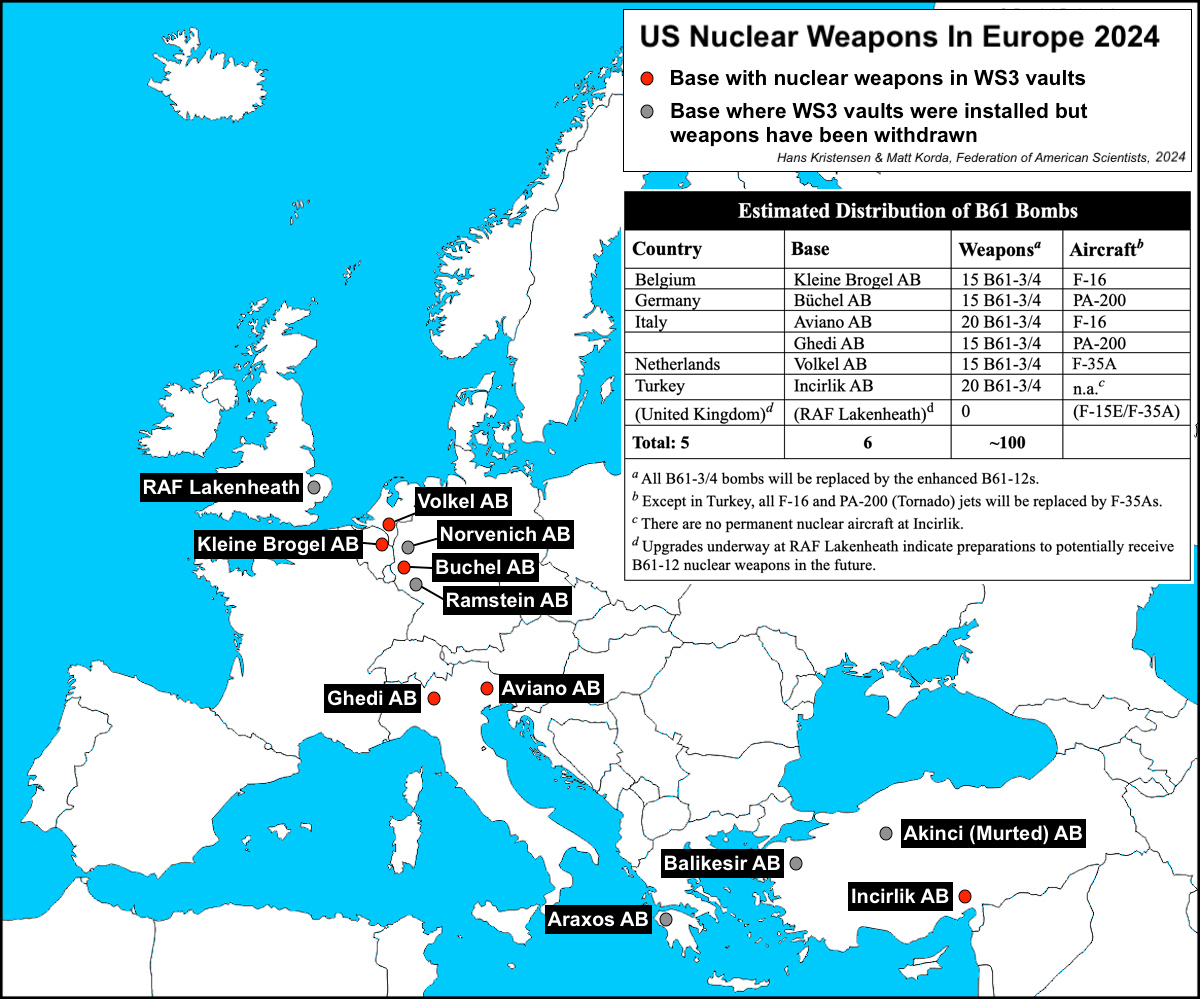

The exercise is co-hosted by Belgium and the Netherlands at the Kleine Brogel and Volkel airbases, respectively. Flight operations are focused over the North Sea and surrounding countries including Belgium, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. NATO says a total of eight bases are involved.

The NATO press release does not identify the countries or bases that are involved, but an article in Key.Aero previously reported that a NATO spokesperson had identified the following:

The thirteen countries match the number of participants identified in the NATO press release. Of these, Finland is obviously the most interesting – perhaps surprising – because the former neutral country has chosen to participate in a nuclear exercise only 18 months after it became a member of NATO.

Base Modernizations

The exercise coincides with major upgrades underway at most of the nuclear bases in Europe. This modernization involves security upgrades to the underground vaults that store the U.S. nuclear weapons, underground cables and nuclear command and control systems, and facilities needed for the new F-35A nuclear-capable fighter-bomber.

Several of the nuclear bases in Europe have recently seen construction of a special loading pad for use by the US C-17 aircraft that transport nuclear weapons and service equipment. This includes Kleine Brogel in Belgium, Ghedi in Italy, and Volkel in the Netherlands. The new pads at Ghedi and Volkel have walls to conceal the nuclear weapons transports. In this year’s Steadfast Noon exercise area, Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium has undergone extensive upgrades to weapons maintenance facilities, including the US Air Force 701st Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS) – the unit responsible for the physical security and maintenance of the weapons, as well as for delivering custody of the weapons to the user country’s air forces if directed to do so. This includes a new drive-through facility for nuclear weapons maintenance trucks. In addition, a large tarmac for C-17A nuclear transport aircraft has been added next to the presumed nuclear weapons area, construction of a high-security facility possibly related to nuclear weapons maintenance has been nearly completed, a new control tower has been added, and underground cables and the Alarm Communication & Display (AC&D) system have been upgraded. Much of this was previously visible on satellite images on Google Earth and described by FAS last year, but since then the image has been removed and all images of the base on Google Earth have been blurred to obscure details. In the interest of nuclear transparency, the image is included here:

Clear images of Kleine Brogel Air Base are now gone from Google Earth. This one was available last year but has since been removed.

In the Netherlands, Volkel Air Base has gone the extra mile to hide operations by building a wall in front of a parking area where aircraft enthusiasts used to watch and film the aircraft. A spokesperson at the base confirmed the purpose of the new wall: “We believe it is important that personnel can work safely and undisturbed. The visibility-restricting measures make it difficult to photograph operational equipment and air base personnel.” For the first time, this Steadfast Noon exercise will include the Royal Netherlands Air Force’s newly nuclear-certified F-35A fighter-bombers.

Walls have been built at Volkel Air Base to hide weapons loading and prevent the public from observing operations and equipment.

The German base at Büchel is in the middle of a year-long upgrade that includes a service area for the F-35A at the northern end of the base, a refurbished runway, as well as what appears to be a security upgrade of the nuclear weapons area with a possible loading pad for the US C-17 transport aircraft that are used to transport nuclear weapons and limited life components.

Modernization of Büchel Air Base in Germany appears to include a new double-fenced security perimeter around the nuclear shelters.

Finally, in this year’s Steadfast Noon operating area the most significant new development is the return of the nuclear mission to RAF Lakenheath, the home of the US Air Force 48th Fighter Wing with F-15E and F-35A fighter-bombers. The base previously was a major nuclear base with 33 underground storage vaults and over 100 nuclear bombs; but in the mid-2000s the US Air Force withdrew all the weapons and the nuclear mission was mothballed.

That began to change in 2022 when RAF Lakenheath was quietly added to the list of bases undergoing nuclear upgrades. Although the Pentagon tried to removed evidence of the change, other documents made it clear that the nuclear mission was returning. Satellite images of construction at RAF Lakenheath indicate that approximately 22 of the 33 protective aircraft shelters with underground WS3 vaults are involved in the nuclear upgrade.

Return of the nuclear mission to RAF Lakenheath appears to include 22 of the original 33 protective aircraft shelters with underground weapons vault.

It is unclear if nuclear weapons will return to RAF Lakenheath or the upgrade is intended as a backup to increase flexibility and reduce vulnerability of the tactical nuclear weapons posture in Europe. After the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey and the policies of the Erdogan government, there has been speculations that the remaining weapons at Incirlik Air Base could be withdrawn; To that end it is interesting that the number of vaults that appear to be readied at RAF Lakenheath is about the same as the numbers remaining active at Incirlik.

Weapons Modernization

In addition to base and aircraft modernizations, the US Air Force is in the process of the replacing the legacy B61-3 and B61-4 tactical nuclear bombs with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb. The priority has been to supply the B-2 bombers at Whiteman AFB with the new weapon, but preparations are now underway to ship the B61-12 to bases in Europe and return the B61-3/4 bombs to the United States for dismantlement. The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) reported recently that the B61-12 is technically certified for not only US Air Force fighter-bombers but also certified NATO aircraft (F-16, F-35A, and Tornado).

The B61-12 nuclear bomb is now technically certified on the B-2 bomber and all US and NATO dual-capable fighter aircraft.

It is unknown if the B61-12 has been shipped to Europe. NATO officials have only been willing to say preparations are underway. If so, it is unlikely to go to all bases at the same time or necessarily within a short period of time; Instead, the new weapon will probably replace the old weapons gradually depending on aircraft and base upgrade status.

Load training of B61-12 (bottom) and legacy B61-4 (top) in a weapons storage vault of the kind installed at bases in Europe. Each vault can store up to four bombs but normally only have one or two. Image credit: US Air Force via The War Zone.

Our current estimate is that there are roughly 100 B61 nuclear bombs deployed in Europe at six bases in five countries. They constitute a small part of the total US nuclear stockpile of roughly 3,700 nuclear weapons.

Broader Context

Steadfast Noon is an annual exercise and planning for this one began over a year ago, NATO says. Nonetheless, the two-week long tactical nuclear weapons exercise with over 60 aircraft from 13 countries is taking place during very tense relations with Russia who for nearly three years has waged a brutal full-scale war against Ukraine and issued numerous warnings to NATO about potential use of nuclear weapons.

Earlier this year, Russia held a series of diverse tactical nuclear weapons exercise and distributed pictures and videos to make sure it was noticed in the West. And most recently Russian president Vladimir Putin announced possible changes to Russia’s nuclear doctrine that appeared intended to signal a lower threshold for potential use of nuclear weapons.

In response, some analysts and institutes in the West are advocating for more nuclear weapons and broadening of the nuclear weapons sharing mission to more countries for what they believe is necessary to “strengthen deterrence” against Russia.

The United States has already increased the role and profile of nuclear bombers in support of NATO and US ballistic missile submarines have resumed visits to European ports – one submarine recently surfaced off Norway in a clear nuclear signal. In announcing the start of exercise Steadfast Noon, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte said that “Steadfast Noon is an important test of the Alliance’s nuclear deterrent and sends a clear message to any adversary that NATO will protect and defend all Allies.” (Emphasis added.)

Combined, these action and reaction steps clearly have raised the nuclear profile over the past several years and are likely to be followed by more. With hardened rhetoric and increased signaling, the salience of nuclear weapons is again growing. Whether this will change the other sides’ behavior for the better or increase nuclear competition and risks even more remains to be seen.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

What Would a Harris Presidency Mean for Nuclear Policy?

The future of U.S. Nuclear Policy is on the table in the 2024 election because the president of the United States has sole authority over the decision to launch nuclear weapons as the Commander in Chief. Proponents of the Trump Administration have advocated for increasing the U.S. tactical nuclear weapons stockpile and encouraging allies like South Korea to develop their own nuclear weapons. What would a Harris Presidency mean for Nuclear Policy?

Women protesters at Greenham Commons and women groups who advocated for the treaty on the prohibitions of nuclear weapons may lead people to believe that women are less in support of nuclear weapons. However, a 2017 Stanford survey found that “women are as hawkish as men and, in some scenarios, are even more willing to support the use of nuclear weapons” in order to protect American troops. This isn’t just endemic to public opinion, when it comes to leadership, research has shown that while increasing the ratio of women in the legislature decreased the defense budget, having a women executive resulted in defense budgets raising by 3 percent. According to the study’s model, “using year 2000 spending and GDP data, the presence of a female executive would produce almost a $10.6 billion increase in U.S. defense spending.” This sentiment was reflected in Harris’s speech at the Democratic National Convention: “As commander in chief, I will ensure America always has the strongest, most lethal fighting force in the world. And I will fulfill our sacred obligation to care for our troops and their families, and I will always honor and never disparage their service and their sacrifice.” In the speech, she also said how she would be tougher than former President Trump on dictators like Kim Jong Un.

Harris has seemed to recognize the existential threat of nuclear war, responding to a question from a student in 2019, and saying “This president [Donald Trump], because he likes to sound tough as opposed to what my mother says — ‘It’s not about how you sound, it’s about how you act.’ — pulls us out of that [Iran Nuclear Deal], exposing us to great harm.” However, the current Biden-Harris Administration has continued nuclear modernization under the Sentinel program, and passed the National Defense Authorization Act, ordering the US Air Force to reduce the time it takes to upload ICBMs.

With regard to policy perspectives, some could argue there are gendered differences. Radiation from nuclear weapons fallout results in higher cases of cancer in females than males. Additionally, women face the brunt of psychological trauma from nuclear weapons attack. Because of these factors, scholars have noted the importance of including gendered analysis factors to nuclear weapons attack.

Increasing women in leadership roles is important for gender parity and bringing in new perspectives, but it does not guarantee peace. Kamala Harris’s lived experience as a woman and daughter of immigrant parents may lead her to pursue more empathetic humanitarian policies or diplomatic arms control solutions, but it does not guarantee it.

For a longer analysis on this issue, you can read more here.

FAS Receives $1.5 Million Grant on The Artificial Intelligence / Global Risk Nexus

Grant Funds Research of AI’s Impact on Nuclear Weapons, Biosecurity, Military Autonomy, Cyber, and other global issues

Washington, D.C. – September 11, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has received a $1.5 million grant from the Future of Life Institute (FLI) to investigate the implications of artificial intelligence on global risk. The 18-month project supports FAS’s efforts to bring together the world’s leading security and technology experts to better understand and inform policy on the nexus between AI and several global issues, including nuclear deterrence and security, bioengineering, autonomy and lethality, and cyber security-related issues.

FAS’s CEO Daniel Correa noted that “understanding and responding to how new technology will change the world is why the Federation of American Scientists was founded. Against this backdrop, FAS has embarked on a critical journey to explore AI’s potential. Our goal is not just to understand these risks, but to ensure that as AI technology advances, humanity’s ability to understand and manage the potential of this technology advances as well.

“When the inventors of the atomic bomb looked at the world they helped create, they understood that without scientific expertise and brought her perspectives humanity would never live the potential benefits they had helped bring about. They founded FAS to ensure the voice of objective science was at the policy table, and we remain committed to that effort after almost 80 years.”

“We’re excited to partner with FLI on this essential work,” said Jon Wolfsthal, who directs FAS’ Global Risk Program. “AI is changing the world. Understanding this technology and how humans interact with it will affect the pressing global issues that will determine the fate of all humanity. Our work will help policy makers better understand these complex relationships. No one fully understands what AI will do for us or to us, but having all perspectives in the room and working to protect against negative outcomes and maximizing positive ones is how good policy starts.”

“As the power of AI systems continues to grow unchecked, so too does the risk of devastating misuse and accidents,” writes FLI President Max Tegmark. “Understanding the evolution of different global threats in the context of AI’s dizzying development is instrumental to our continued security, and we are honored to support FAS in this vital work.”

The project will include a series of activities, including high-level focused workshops with world-leading experts and officials on different aspects of artificial intelligence and global risk, policy sprints and fellows, and directed research, and conclude with a global summit on global risk and AI in Washington in 2026.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

ABOUT FLI

Founded in 2014, the Future of Life Institute (FLI) is a leading nonprofit working to steer transformative technology towards benefiting humanity. FLI is best known for their 2023 open letter calling for a six-month pause on advanced AI development, endorsed by experts such as Yoshua Bengio and Stuart Russell, as well as their work on the Asilomar AI Principles and recent EU AI Act.

Federation of American Scientists Releases Latest India Edition of Nuclear Notebook

Washington, D.C. – September 6, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists today released the latest India edition of the Nuclear Notebook, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and available here. The authors, Hans Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, estimate that India has produced enough weapons-grade plutonium for up to 210 nuclear warheads but has likely assembled closer to 172. Along with its growing arsenal, India is developing at least five new weapon systems and several new delivery platforms. Seeking to address security concerns with both Pakistan and China, India appears to be taking steps to increase the readiness of its arsenal, including “pre-mating” some of its warheads with missiles in canisters.

SSBNs and MIRVs

This Nuclear Notebook provides an overview of India’s nuclear modernization, documenting the development of new land and sea-based missiles, the retirement of older nuclear-capable systems, and the commissioning of India’s second indigenous nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN). The authors also analyze India’s significant progress in developing its next generation of land-based missiles with the capability to launch multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs).

###

ABOUT THE NUCLEAR NOTEBOOK

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The joint publication began in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenals and the role of nuclear weapons in national security.

This latest issue follows the release of the 2024 North Korea Nuclear Notebook. The next issue will focus on the United Kingdom. More research is located at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

The Federation of American Scientists’ work on nuclear transparency would not be possible without generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, Longview Philanthropy, the Jubitz Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Hot-Launch Yoga: Cobra Pose Reveals Nuke Repose

The Indian Navy has integrated yoga into its training practices for decades, and in recent years it has conducted yoga sessions onboard its warships during port visits as a form of cultural diplomacy. These events, and the social media posts documenting them, occasionally offer fascinating data points about the status of specific military capabilities.

In particular, yoga-related social media posts and satellite imagery now indicate that one of India’s oldest naval missiles capable of launching nuclear weapons has likely been retired as the country continues to develop its sea-based nuclear deterrent.

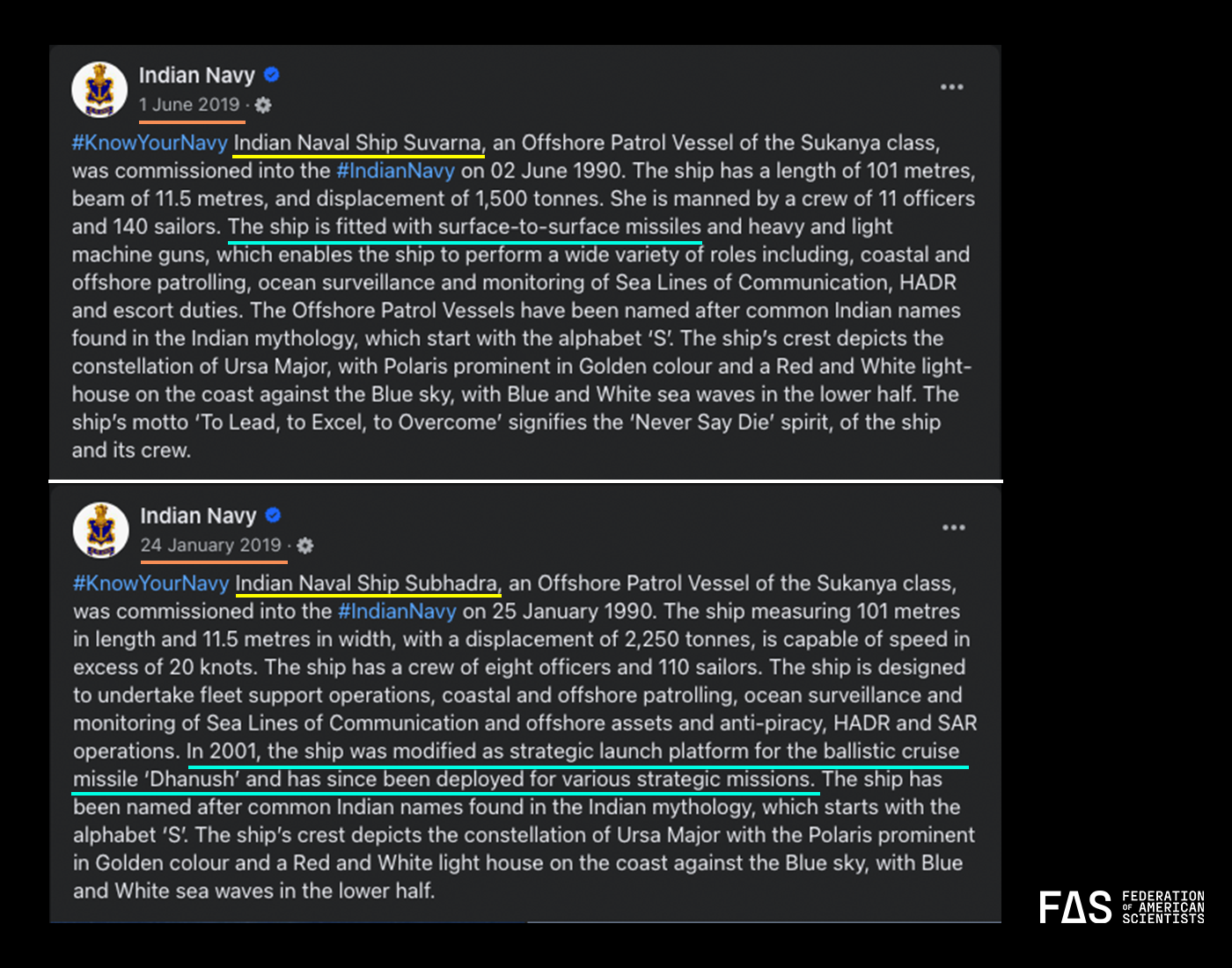

For nearly 15 years, India’s naval nuclear forces solely consisted of two offshore patrol vessels that had been specially configured to launch nuclear-capable Dhanush missiles.

The Dhanush––a variant of India’s Prithvi short-range ballistic missile––had always been somewhat of an odd capability for India’s navy. Given its relatively short range and liquid-fuel design––meaning that it would need to be fueled immediately prior to launch––the Dhanush’s utility as a strategic deterrence weapon was severely limited. The ships carrying these missiles would have to sail dangerously close to the Pakistani or Chinese coasts to target facilities in those countries, making them highly vulnerable to counterattack.

For those reasons, we have continuously assessed that as India’s long-planned nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines become operational, the Dhanush would eventually be phased out.

New data points from social media and satellite imagery indicate it is very likely that this has now happened.

––

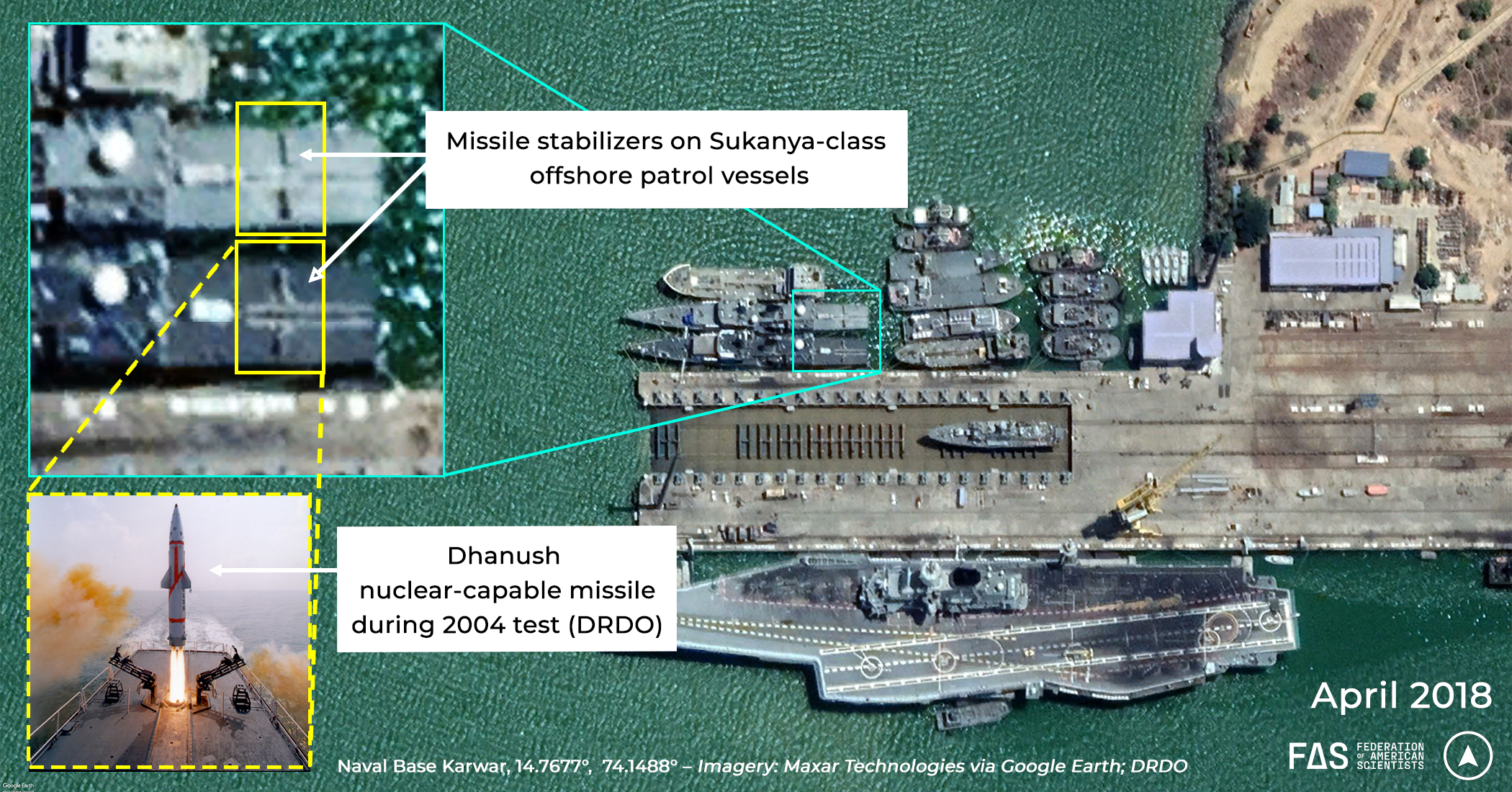

For years, India’s nuclear-capable Dhanush missiles were carried by two specially configured Sukanya-class offshore patrol vessels, known as INS Subhadra (hull number P51) and INS Suvarna (P52). These two vessels have been most clearly distinguishable from India’s four other Sukanya-class patrol vessels by the presence of missile stabilizer platforms on their aft decks that could be clearly seen through satellite imagery, including in this image from April 2018.

The last time that any official Indian source had indicated that the Dhanush capability was still operational was in 2019, when two Facebook posts by the Indian Navy’s official page specifically mentioned the capability and implied that it was still active on both INS Subhadra and INS Suvarna.

In December 2021, satellite imagery from Airbus showed two Sukanya-class vessels at Naval Base Karwar, one with missile stabilizers and the other without. The vessel without stabilizers also featured new aft deck markings in a cross pattern that had not been seen before on other vessels of that class. Without additional images, it was unclear whether the vessel featuring the new markings was one of the two nuclear-capable ships or another ship in the Sukanya-class that is also home-ported at Karwar––INS Sukanya (P50). If the vessel without stabilizers was the INS Sukanya, then the markings on the ship would not have necessarily indicated any change to the nuclear mission, since INS Sukanya had never been equipped with missile stabilizers. If the new pattern belonged to one of the two vessels that had previously been equipped with those stabilizers, however, then it would indicate that those stabilizers had been removed, thus likely eliminating that vessel’s nuclear strike role and removing the Dhanush missile from combat duty.

Clarity arrived through a strange medium: a series of yoga-related Instagram posts published by India’s public broadcaster during port visits to Seychelles in October 2022, indicating that the vessel with the new deck markings was indeed INS Suvarna. This meant that as of December 2021 at the latest, the missile stabilizers on INS Suvarna had been removed, meaning that the vessel has since been unable to launch nuclear-capable Dhanush ballistic missiles.

At the exact same time that the crew of INS Suvarna was practicing yoga in Seychelles, another satellite image captured by Maxar Technologies showed another Sukanya-class patrol vessel at Naval Base Karwar with its aft deck under construction. Similarly to the previous case, it remained unclear whether this vessel was the nuclear-capable INS Subhadra or the non-nuclear INS Sukanya. A subsequent satellite image in April 2023 indicated that the aft deck had been repainted with a new cross pattern with a circle––likely to be used as a helipad.

This same unique deck pattern was then on full display at another yoga session in Seychelles, during a port visit by INS Subhadra in February 2024. This indicates that this vessel lost its ability to deliver nuclear-capable Dhanush missiles when its aft deck began construction around October 2022.

Since then, neither vessel has been seen with its missile stabilizer platforms returned to the aft deck, suggesting that the nuclear-capable Dhanush has finally been removed from active service and that the nuclear strike mission for the Sukanya-class patrol vessels has likely been retired. Given that the Dhanush is a close variant of India’s land-based Prithvi SRBM, it is likely that the Dhanush’s associated warheads have not been dismantled, but instead have been returned to India’s stockpile for use by these short-range systems.

—

Although the yoga-related source of the news may have been surprising, the Dhanush missile’s retirement in itself was not. For years, we have assumed that the system would be eliminated once India’s sea-based deterrent reached a higher level of maturity. That time appears to be now: after years of delays, India’s second ballistic missile submarine––INS Arighat––is expected to be commissioned into the Navy before the end of 2024. Two more ballistic missile submarines are expected to follow over the course of this decade, and satellite imagery indicates that they will be able to carry double the number of missiles as India’s first two submarines.

More details on these developments, as well as other elements of India’s evolving nuclear arsenal, will be available in our forthcoming September publication: Indian Nuclear Weapons, 2024, in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

United States Discloses Nuclear Warhead Numbers; Restores Nuclear Transparency

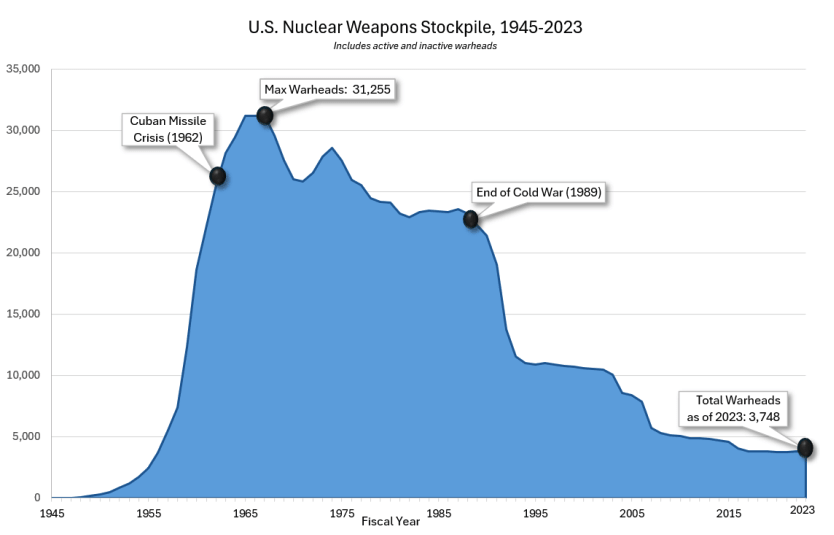

Note: The initial NNSA release showed an incorrect graph that did not accurately depict the size of the stockpile for the period 2012-2023. The corrected graph is shown above.

[UPDATED VERSION] The Federation of American Scientists applauds the United States for declassifying the number of nuclear warheads in its military stockpile and the number of retired and dismantled warheads. The decision is consistent with America’s stated commitment to nuclear transparency, and FAS calls on all other nuclear states to follow this important precedent.

The information published on the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) web site today shows that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile as of September 2023 included 3,748 nuclear warheads, only 40 warheads off FAS’ estimate of 3,708 warheads.

The information also shows that the United States last year dismantled only 69 retired nuclear warheads, the lowest number since 1994.

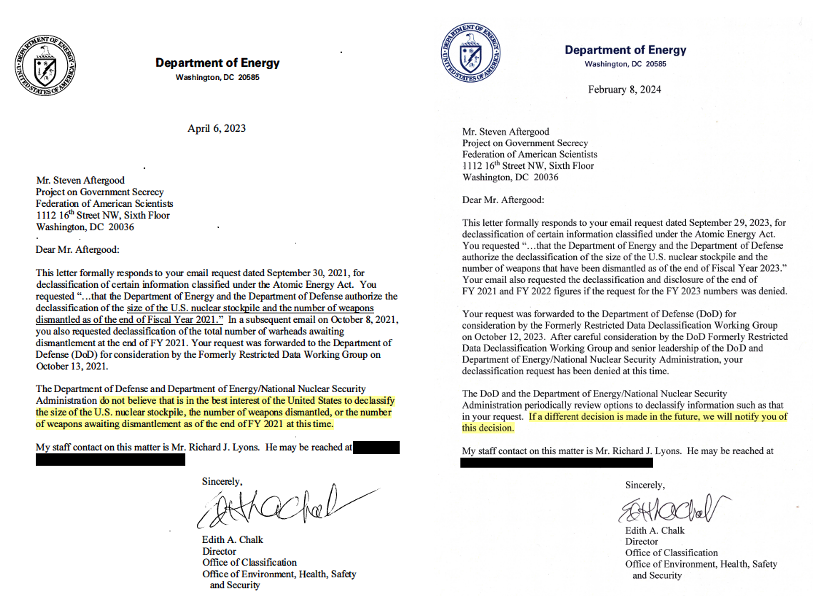

FAS has previously requested that the United States release the size of the US nuclear arsenal for FY2021, FY2022, and FY2023, but those requests were denied. FAS believes the information was wrongly withheld and that today’s declassification decision vindicates our belief that stockpile disclosures do not negatively affect U.S. security but should be provided to the public.

With today’s announcement, the Biden Administration has restored the nuclear stockpile transparency that was created by the Obama administration, halted by the Trump administration, revived by Biden administration in its first year, but then halted again for the past three years.

While applauding the U.S. disclosure, FAS also urged other nuclear-armed states to disclose their stockpile numbers and warheads dismantled. Excessive nuclear secrecy creates mistrust, fuels worst-case planning, and enables hardliners and misinformers to exaggerate nuclear threats.

What The Nuclear Numbers Show

The declassified stockpile numbers show that the United States maintained a total of 3,748 warheads in its military stockpile as of September 2023. The military stockpile includes both active and inactive warheads in the custody of the Department of Defense. The information also discloses weapons numbers for the previous two years, numbers that the U.S. government had previously declined to release.

Although there have minor fluctuations, the numbers show that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has remained relative stable for the past seven years. The fluctuations during that period do not reflect decision to increase or decrease the stockpile but are the result of warheads movements in and out of the stockpile as part of the warhead life-extension and maintenance work.

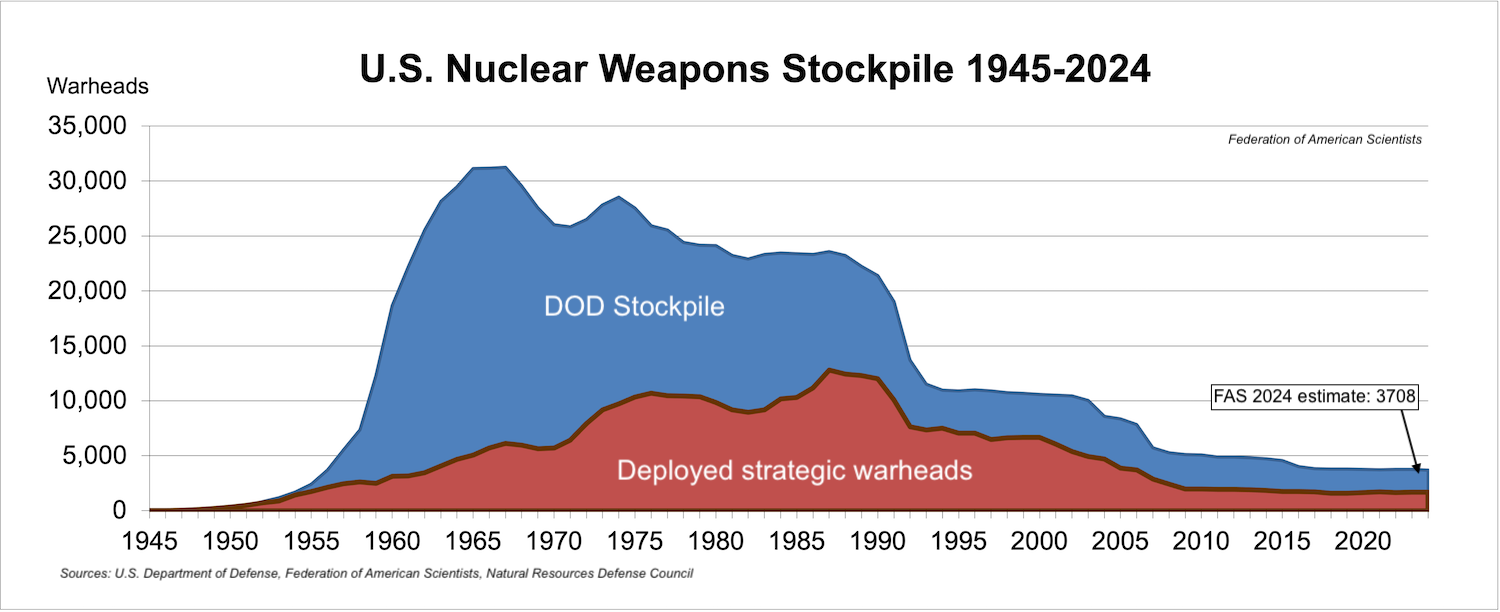

Although the warhead numbers today are much lower than during the Cold War and there have been reductions since 2000, the reduction since 2007 has been relatively modest. Although the New Start treaty has had some indirect effect on the stockpile size due to reduced requirement, the biggest reductions since 2007 have be caused by changes in presidential guidance, strategy, and modernization programs. The initial chart released by NNSA did not accurately show the 1,133-warhead drop during the period 2012-2023. NNSA later corrected the chart (see top of article). The chart below shows the number of warheads in the stockpile compared with the number of warheads deployed on strategic launchers over the years.

This graph shows the size of the U.S. nuclear stockpile over the years plus the portion of those warheads deployed on strategic launchers. The stockpile number for 2024 and the strategic launcher warheads are FAS estimates.

The information also shows that the United States last year dismantled only 69 retired nuclear warheads. That is the lowest number of warheads dismantled in a year since 1994. The total number of retired nuclear warheads dismantled 1994-2023 is 12,088. Retired warheads awaiting dismantlement are not in the DOD stockpile but in the DOE stockpile.

The information disclosed also reveals that there are currently another approximately 2,000 retired warheads in storage awaiting dismantlement. This number is higher than our most recent estimate (1,336) because of the surprisingly low number of warheads dismantled in recent years. Because dismantlement appears to be a lower priority, the number of retired weapons awaiting dismantlement today (~2,000) is only 500 weapons lower than the inventory was in 2015 (~2,500).

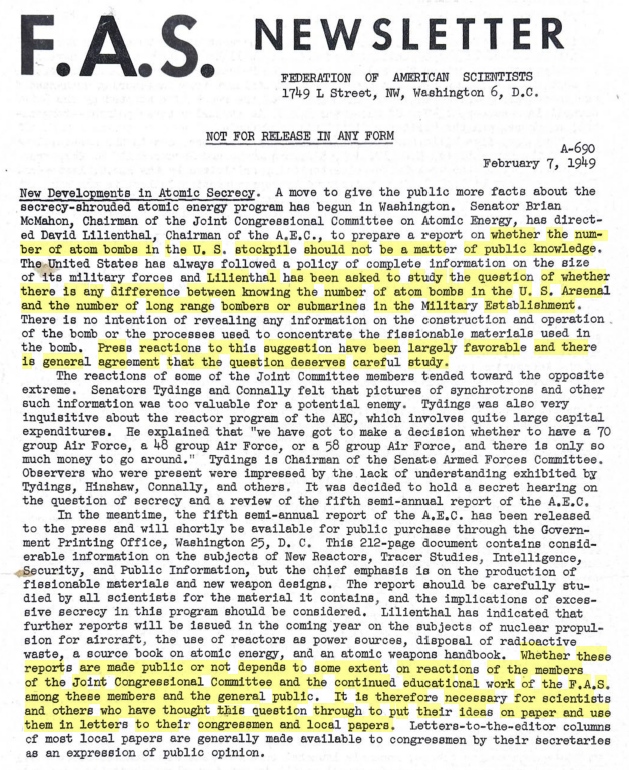

FAS’ Work For Nuclear Transparency

The Federation of American Scientists has worked since its creation to increase responsible transparency on nuclear weapons issues; in fact, the nuclear scientists that built the bomb created the “Federation of Atomic Scientists” to enable some degree of transparency to discuss the implications of nuclear weapons (see FAS newsletter from 1949). There are of course legitimate nuclear secrets that must remain so, but nuclear stockpile numbers are not among them.

This FAS newsletter from 1949 describes the debate and FAS effort in support of transparency of the US weapons stockpile.

One part of FAS’ efforts, spearheaded by Steve Aftergood who for many years directed the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, has been to report on the government’s discussions about what needs to be classified and repeatedly request declassification of unnecessary secrets such as the stockpile numbers. This work yielded stockpile declassifications in some years (2012-2018, 2021) while in other years (2019-2020 and 2022-2024) FAS’ declassified requests were initially denied. Most recently, in February 2024, an FAS declassification request for the stockpile numbers as of 2023 was denied, although the letter added: “If a different decision is made in the future, we will notify you of this decision” (see rejection letters). Given these denials, FAS in March 2024 sent a letter to President Biden outlining the important reasons for declassifying the numbers.

The new disclosure of the stockpile numbers suggests that denial of earlier FAS declassification requests in 2023 and 2024 may not have been justified and that future years’ numbers should not be classified.

The other part of FAS’ efforts has been the Nuclear Information Project, which works to analyze, estimate, and publish information about the U.S. nuclear arsenal. In 2011, when the Obama administration first declassified the history of the stockpile, the FAS estimate was only 13 warheads off from the official number of 5,112 warheads. The Project also works to increase transparency of the other nuclear-armed states by providing the public with estimates of their nuclear arsenals. The project described the structures that enabled Matt Korda on our team and others to discover the large missile silo fields China was building, and NATO officials say our data is “the best for open source information that doesn’t come from any one nation.”

Why Nuclear Transparency Is Important

FAS has since its founding years worked for maximum responsible disclosure of nuclear weapons information in the interest of international security and democratic values. In a letter to President Biden in March 2024 we outlined those interests.

After denials in 2023 and February 2024 of FAS declassification requests, FAS in March sent President Biden a letter outlining why the denials were wrong. Click here to download full version of letter.

First, responsible transparency of the nuclear arsenal serves U.S. security interests by supporting deterrence and reassurance missions with factual information about U.S. capabilities. Equally important, transparency of stockpile and dismantlement numbers demonstrate that the United States is not secretly building up its arsenal but is dismantling retired warheads instead of keeping them in reserve. This can help limit mistrust and worst-case scenario planning that can fuel arms races.

Second, the United States has for years advocated and promoted nuclear transparency internationally. Part of its criticism of Russia and China is their lack of disclosure of basic information about their nuclear arsenals, such as stockpile numbers. U.S. diplomats have correctly advocated for years about the importance of nuclear transparency, but their efforts are undermined if stockpile and dismantlement numbers are kept secret because it enables other nuclear-armed states to dismiss the United States as hypocritical.

Third, nuclear transparency is important for the debate in the United States (and other Allied democracies) about the status and future of the nuclear arsenal and strategy and how the government is performing. Opponents of declassifying nuclear stockpile numbers tend to misunderstand the issue by claiming that disclosure gives adversaries a military advantage or that the United States should not disclose stockpile numbers unless the adversaries do so as well. But nuclear transparency is not a zero-sum issue but central to the democratic process by enabling informed citizens to monitor, debate, and influence government policies. Although the U.S. disclosure is not dependent on other nuclear-armed states releasing their stockpile numbers, Allied countries such as France and the United Kingdom should follow the U.S. example, as should Russia and China and the other nuclear-armed states.

Acknowledgement: Mackenzie Knight, Jon Wolfsthal, and Matt Korda provided invaluable edits.

More information on the FAS Nuclear Information Project page.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

North Korean Nuclear Weapons, 2024: Federation of American Scientists Release Latest North Korea Nuclear Weapons Estimate

North Korea continues to modernize and grow its nuclear weapons arsenal

Washington, D.C. – July 15, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists today released the North Korea edition of the Nuclear Notebook, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and available here. The authors, Hans Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, estimate that North Korea may have produced enough fissile material to build up to 90 nuclear warheads, but the famously opaque country has likely assembled fewer than that—potentially around 50. This is not a significant change from previous estimates (2021, 2022) but follows the trendline researchers are tracking. North Korea’s abandonment of a no-first-use policy coincides with the country’s recent efforts to develop tactical nuclear weapons.

Warhead Preparation and Delivery

While its status remains unclear, North Korea has developed a highly diverse missile force in all major range categories. In this edition of the Nuclear Notebook, FAS researchers documented North Korea’s short-range tactical missiles, sea-based missiles, and new launch platforms such as silo-based and underwater platforms Additionally, FAS researchers provided an overview of North Korea’s advancements in solid-fuel missile technology, which will improve the survivability and mobility of its missile force.

“Since 2006, North Korea has detonated six nuclear devices, updated its nuclear doctrine to reflect the irreversible role of nuclear weapons for its national security, and continued to introduce a variety of new missiles test-flown from new launch platforms,” says Hans Kristensen, director of FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

The size and composition of North Korea’s nuclear stockpile depends on warhead design and the number and types of launchers that can deliver them.

Disco Balls, Peanuts, and Olives

Researchers informally refer to North Korea’s nuclear warhead designs as the disco ball, peanut, and olive based on their appearance in North Korean state media. These images, taken from this recent issue of the North Korea Nuclear Notebook, show supposed warhead designs, including a single-stage implosion device (nicknamed “disco-ball”), a new miniaturized warhead called the Hwasan-31 (nicknamed “olive”), and a two-stage thermonuclear warhead (nicknamed “peanut”).

Caption: Images from the Nuclear Notebook: North Korea, 2024. Top left “disco ball”, top right “olive”, bottom left “peanut”. (Source: Federation of American Scientists).

While North Korea’s warhead design and stockpile makeup are not verifiable, it is possible that most weapons are single-stage fission weapons with yields between 10 and 20 kilotons of TNT equivalent, akin to those demonstrated in the 2013 and 2016 tests. A smaller number could be composite-core single-stage warheads with a higher yield.

The Hwasan-31, first showcased in 2023, demonstrates North Korea’s progress towards developing and fielding short-range, or tactical, nuclear weapons. In addition to the development and demonstration of new long-range strategic nuclear-capable missiles, the pursuit of tactical nuclear weapons appears intended to provide options for nuclear use below the strategic level and to strengthen North Korea’s regional deterrence posture.

###

ABOUT THE NUCLEAR NOTEBOOK

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The joint publication began in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenals and the role of nuclear weapons in national security.

This latest issue follows the release of the 2024 United States Nuclear Notebook. The next issue will focus on India. More research is located at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Nuclear Experts from the Federation of American Scientists Call for More Transparency from the Defense Department with Its Decision to Certify the Sentinel ICBM Program

The Air Force’s flawed assumptions, processes, and estimation methodologies have led to unprecedented cost overruns

Washington, D.C. – July 9, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) stands with fellow scientists and peer organizations critiquing the Biden administration’s decision to certify the Sentinel ICBM program, despite it being 81% over budget and two to three years behind schedule. This program does not improve American safety or global peace efforts, and is an unnecessary financial burden on taxpayers.

The Pentagon’s review of the Sentinel came after the projected cost of the project rose by 37 percent, to $131 billion––requiring a re-evaluation of the program and a consideration of possible alternatives under the Nunn-McCurdy Act. Recent reporting from Bloomberg indicates that the Sentinel’s costs are now estimated to rise to $141 billion. This represents an 81 percent increase from the Pentagon’s own estimate in 2020.

“You can be for nuclear weapons modernization and think this program is both in trouble and needs a serious re-examination. At 81% over budget and $140 billion and climbing, we owe it to consider real alternatives and get modernization right,” says Jon Wolfsthal, Director of Global Risk at FAS.

In its justification decision, the Pentagon suggested that the Nunn-McCurdy review team considered “‘four to five different options,’ including extending the aging Minuteman III missiles in 2070, ‘hybrid options of different ground facilities, mobile versus fixed,’ and others.” However, the Pentagon’s stated justifications for continuing the program, its timelines, and its funding are all questioned by the FAS team.

Associate Director for FAS’ Nuclear Information Project, Matt Korda, asks: “Where does the year 2070 come from? The Air Force previously referred to the year 2075 in its program documentation, and as far as I know, neither year is codified in any official policy documents like the National Defense Strategy or the Nuclear Posture Review. Yet these benchmarks have enormous bearing on cost estimates, and can be purposely selected to tip the scales and make some options look more palatable than others.” Korda wrote a detailed report in 2021 showing how changes in these cost benchmarks would have indicated that alternatives to the Sentinel––such as life-extending the current fleet of Minuteman III ICBMs––would very likely have been cheaper than building an entirely brand-new weapon system.

Director of FAS’s Nuclear Information Project, Hans Kristensen, is more pointed in his criticism: “Despite massively escalating cost projection, having sold the new Sentinel ICBM program to Congress based on unrealistic cost, the Pentagon says go ahead anyway.”

Kristensen and Korda are leading researchers on the global stockpile of nuclear weapons. Along with their colleagues, Senior Research Associates Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight, they produce and distribute, in conjunction with the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the Nuclear Notebook, detailed reports on the status of nuclear weapons worldwide.

Knight was among the first to identify Sentinel’s extreme cost overruns and raise public awareness of this issue. In March she wrote what should happen next:

Secretary Austin’s likely certification of the Sentinel program should be open to public interrogation, and Congress must thoroughly examine whether every requirement is met before allowing the program to continue. Congress should ask the Government Accountability Office and Congressional Budget Office to conduct independent reviews to interrogate the Pentagon’s justification for Sentinel and ensure hawk-eyed scrutiny of the program’s next steps.

The Hill, March 1, 2024

She adds now: “The Sentinel program being allowed to continue despite an 81% cost increase sets a dangerous precedent. Whether the program is flawed, necessary, or not, Congress and the administration should not allow ostensibly limitless spending on nuclear weapons programs. How much is too much?”

More than 700 scientists, including ten Nobel laureates and 23 members of the National Academies, have signed a letter calling for President Biden and Congress to cancel the program, led by the Union of Concerned Scientists.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Photo Depicts Potential Nuclear Mission for Pakistan’s JF-17 Aircraft

Due to longstanding government secrecy, analyzing Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program is fraught with uncertainties. While it is known that Pakistan–along with many other nuclear-armed states–is modernizing its nuclear capabilities and fielding new weapons systems, little official information has been released regarding these plans or the status of its arsenal.

One of the many questions researchers have been asking concerns the modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear-capable aircraft and its associated air-launched cruise missiles (ALCM). It has been long assumed that the Mirage III and Mirage V fighter bombers are the two aircraft with a nuclear delivery role in the Pakistan Air Force (PAF). The Mirage V is thought to have a strike role with Pakistan’s limited supply of nuclear gravity bombs, while the Mirage III has been used to conduct test launches of Pakistan’s dual-capable Ra’ad-I (Hatf-8) ALCM, as well as the follow-on Ra’ad-II. The Ra’ad ALCM was first tested in 2007 and has since remained Pakistan’s only nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missile.

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) reported in 2017 that the Ra’ad cruise missile was “conventional or nuclear,” a term normally used to describe a dual-capable system.

In order to retire its aging Mirage III and V aircraft and bolster defense production, Pakistan has procured over 130 operational JF-17 aircraft–which are jointly produced with China–and plans to acquire more in the future. During the 2024 Pakistan Day Parade, the PAF also announced a JF-17 PFX (Pakistan Fighter Experimental) project to maximize the operational lifespan and modernize the capabilities of the JF-17 aircraft.

Over the past few years, several reports have suggested Pakistan may incorporate the dual-capable Ra’ad ALCM onto the JF-17 so that the newer aircraft could eventually take over the nuclear strike role from the Mirage III/Vs. However, little information has been revealed about the status of this procurement and whether the JF-17s will replace the Mirage III and Vs in the nuclear mission. That is, until March 2023, when an aviation photographer captured an image that could help answer some of these lingering questions.

A possible new nuclear mission

During rehearsals for the 2023 Pakistan Day Parade (which was subsequently canceled), an image surfaced of a JF-17 Thunder Block II carrying what was reported to be a Ra’ad ALCM. Notably, this was the first time such a configuration had been observed in public.

Photo credit: Rana Suhaib/Snappers Crew

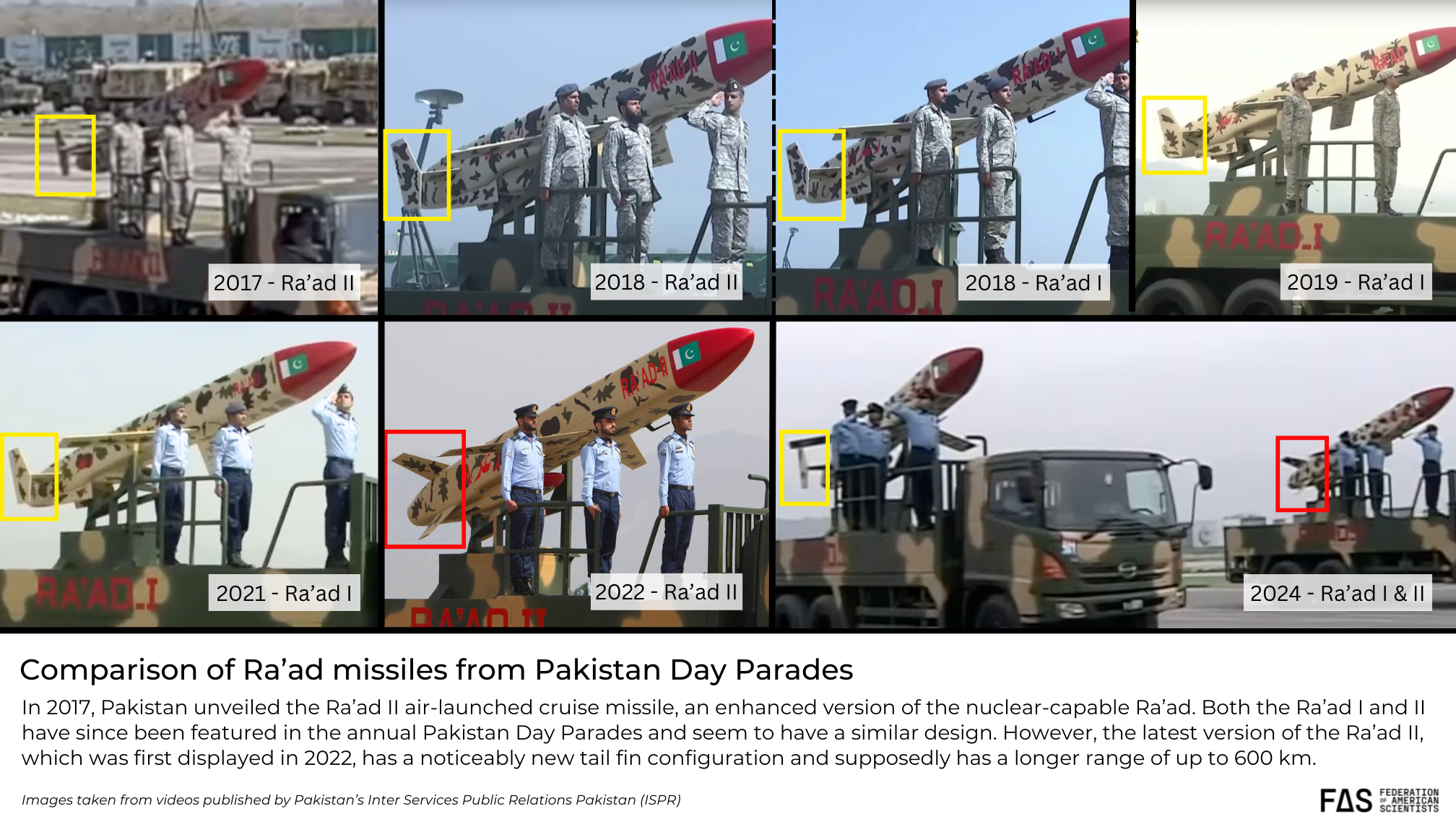

FAS was able to purchase the original image. To try and ascertain which type of Ra’ad is in the JF-17 image–the original Ra’ad-I or the extended-range Ra’ad-II–we compared it to other Ra’ad-I and -II missiles displayed in the 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021, 2022, and 2024 Pakistan Day Parades (the parades in 2020 and 2023 were canceled) where the Ra’ad-I and Ra’ad-II were showcased alongside other nuclear-capable missiles such as the Nasr, Ghauri, Shaheen-IA and -II, as well as the Babur-1A.

Between 2017–when the Ra’ad-II was first publicly unveiled–and 2022, there were very few observable differences between the Ra’ad-I and -II. During this period, both missiles featured a new engine air intake, and although the Ra’ad-II was presented as having nearly double the range capability, this was not clearly observable through external features.

In 2017, Pakistan unveiled the Ra’ad Il air-launched cruise missile, an enhanced version of the nuclear-capable Ra’ad. Both the Ra’ad I and II have since been featured in the annual Pakistan Day Parades and seem to have a similar design. However, the latest version of the Ra’ad II, which was first displayed in 2022, has a noticeably new tail fin configuration and supposedly has a longer range of up to 600 km.

However, in 2022, a new version of the Ra’ad-II was displayed at the 2022 Pakistan Day Parade. Notably, this new version had an ‘x-shaped’ tail fin configuration as opposed to the other ‘twin-tail’ configurations seen in previous versions of the missile. The subsequent 2024 Pakistan Day parade also showcased the two distinct versions of the Ra’ad with their respective tail fin arrangements.

The fin arrangements of the photographed missile on the JF-17 appear to more closely match the ‘twin-tail’ configuration of the Ra’ad-I, rather than the newer ‘x-shaped’ tail of the Ra’ad-II, especially since it is unlikely that an outdated version of the Ra’ad II would be utilized in a flight test intended to demonstrate state-of-the-art capabilities.

Pakistan is also developing a conventional, anti-ship variant of the Ra’ad ALCM, known as Taimoor, that can be launched from the JF-17. Photos of the missile indicate that the two designs are highly similar, although the Taimoor missile also appears to include an ‘x-tail’ fin configuration, and its length is reported to be 4.38 meters. The ‘x-tail configuration’ would appear to indicate that the missile photographed on the JF-17 was not the Taimoor; however, for additional clarity, we measured multiple parade images of both versions of the Ra’ad and compared their lengths to that of the photographed missile.

We took an image of the Ra’ad-I from the 2019 Pakistan Day Parade and used the Vanishing Point feature in Photoshop to add gridded planes that simulate a 3D space in order to account for the angle at which the image was taken and the depth at which the missile sits compared to the side of the truck. After finding the make and model of the vehicle carrying the missile (which appears to be an early version of the Hino 500 Series FM 2630), we used the truck’s trailer axle spread of approximately 1.3 meters and wheelbase of 4.24 meters reference values and used Photoshop’s measuring tool to render an approximate length. We found it to be around 4.9 meters.

To estimate the dimensions of the Ra’ad-II, we started with a photo from the 2022 Pakistan Day Parade. Using the same methodology with Photoshop’s Vanishing Point tool to account for the angle of the photo and the distance from the missile’s position in the center of the vehicle to the foremost gridded plane that measures the length of the truck, we roughly estimated the size of the missile to be around 4.9 meters.

We also double-checked the dimensions of the cruise missile in the JF-17 image. Since we know that the JF-17 is roughly 14.3 meters long, we used that number as a reference value and employed Photoshop’s Vanishing Point and measuring tool again to render an approximate length of the missile, given its lowered position in relation to the edge of the fuselage. The result was 4.9 meters, which matches the reported dimensions of the Ra’ad-I and -II ALCM as well as our estimated measurements. This measurement is also longer than the Taimoor’s reported 4.38-meter length.

While it is possible that the missile could be an old Ra’ad-II, given that the 2017 version also had a ‘twin-tail’ configuration, that version of the Ra’ad-II appears to be outdated and is therefore unlikely to be utilized in a flight test. Still, it is possible that more information, images, or statements from the Pakistan government could surface that answer some of these questions.

Observing the differences between the Ra’ad-I and Ra’ad-II missiles raises a few questions. How was Pakistan able to nearly double the range of the Ra’ad from an estimated 350 km to 550 km and then to 600 km for the newest version without noticeably changing the size of the missile to carry more fuel? The answer could possibly be that the Ra’ad-II engine design is more efficient, the construction components are made from lighter-weight materials, or the payload has been reduced.

These measurements offer additional evidence to support our conclusion that the missile observed in the photographed image of the JF-17 is the Ra’ad-I ALCM.

Implications for Pakistan’s nuclear forces

Given the lack of publicly available information from the government of Pakistan about its nuclear forces, we must rely on these types of analyses to understand the status of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal. From these observations, it is likely that Pakistan has made significant progress toward equipping its JF-17s with the capability to eventually supplement–and possibly replace–the nuclear strike role of the aging Mirage III/Vs. Additionally, it is evident that Pakistan has redesigned the Ra’ad-II ALCM, but little information has been confirmed about the purpose or capabilities associated with this new design. It is also unclear whether either of the Ra’ad systems has been deployed, but this may only be a question of when rather than if. Once deployed, it remains to be seen if Pakistan will also continue to retain a nuclear gravity bomb capability for its aircraft or transition to stand-off cruise missiles only.

This all takes place in the larger backdrop of an ongoing and deepening nuclear arms competition in the region. Pakistan is reportedly pursuing the capability to deliver multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) with its Ababeel land-based missile, while India is also pursuing MIRV technology for its Agni-P and Agni-5 missiles, and China has deployed MIRVs on a number of its DF-5B ICBMs and DF-41. In addition to the Ra’ad ALCM, Pakistan has also been developing other short-range, lower-yield nuclear-capable systems, such as the NASR (Hatf-9) ballistic missile, that are designed to counter conventional military threats from India below the strategic nuclear level.

These developments, along with heightened tensions in the region, have raised concerns about accelerated arms racing as well as new risks for escalation in a potential conflict between India and Pakistan, especially since India is also increasing the size and improving the capabilities of its nuclear arsenal. This context presents an even greater need for transparency and understanding about the quality and intentions behind states’ nuclear programs to prevent mischaracterization and misunderstanding, as well as to avoid worst-case force buildup reactions.

The author would like to thank David La Boon and Decker Eveleth for their invaluable guidance and feedback on using Photoshop’s Vanishing Point feature.

Correction: After the article’s publication, the final image was removed and replaced with the correct image. The language and conclusions of the piece remained unchanged.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Nuclear Experts from the Federation of American Scientists Contribute to SIPRI Yearbook 2024

FAS’s Nuclear Information Project estimates that the combined global inventory of nuclear warheads is approximately 12,120

Washington, DC – June 17, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists’ nuclear weapons researchers Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda with the Nuclear Information Project write in the new SIPRI Yearbook, released today, that the world’s nuclear arsenals are on the rise, and massive modernization programs are underway.

“China is expanding its nuclear arsenal faster than any other country,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “But in nearly all of the nuclear-armed states, there are either plans or a significant push to increase nuclear forces.”

“We are entering a new period in the post-Cold War era as nuclear stockpiles increase and nuclear transparency decreases. It is, therefore, extremely important for independent researchers to inject factual data into the debate,” says Matt Korda, Associate Researcher in the SIPRI Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Senior Research Fellow at FAS.

Kristensen and Korda are leading researchers on the global stockpile of nuclear weapons. Along with their colleagues Eliana Johns and Mackenzie Knight, the Nuclear Information Project team at FAS produces the Nuclear Notebook, a bi-monthly report published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists detailing current estimates of nuclear weapon stockpiles. This work plays an increasingly important role as government transparency about nuclear forces continues to decline around the globe. Ongoing reports, archives, and other materials are available at fas.org.

The first edition of the SIPRI Yearbook was released in 1969, with the aim of producing “a factual and balanced account of a controversial subject-the arms race and attempts to stop it.” Interested parties may download excerpts from the latest Yearbook in several languages here, or purchase the report in full.

Read a summary of SIPRI findings by FAS Nuclear Information Project researcher Eliana Johns here.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.