A Conversation with Nobel Laureate Dr. Jack Steinberger

On January 27, 2014, I had the privilege and pleasure of meeting with Dr. Jack Steinberger at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Geneva, Switzerland. In a wide-ranging conversation, we discussed nuclear disarmament, nonproliferation, particle physics, great scientific achievements, and solar thermal power plants. Here, I give a summary of the discussion with Dr. Steinberger, a Nobel physics laureate, who serves on the FAS Board of Sponsors and has been an FAS member for decades.

Dr. Steinberger shared the Nobel Prize in 1988 with Leon Lederman and Melvin Schwartz “for the neutrino beam method and the demonstration of the doublet structure of the leptons through the discovery of the muon neutrino.” Dr. Steinberger has worked at CERN since 1968. CERN is celebrating its 60th anniversary this year and is an outstanding exemplar of multinational cooperation in science. Thousands of researchers from around the world have made use of CERN’s particle accelerators and detectors. Notably, in 2012, two teams of scientists at CERN found evidence for the Higgs boson, which helps explain the origin of mass for many subatomic particles. While Dr. Steinberger was not part of these teams, he helped pioneer the use of many innovative particle detection methods such as the bubble chamber in the 1950s. Soon after he arrived at CERN, he led efforts to use methods that recorded much larger samples of events of particle interactions; this was a necessary step along the way to allow discovery of elusive particles such as the Higgs boson.

In addition to his significant path-breaking contributions to physics, he has worked on issues of nuclear disarmament which are discussed in the book A Nuclear-Weapon-Free World: Desirable? Feasible?, (was edited by him, Bhalchandra Udgaonkar, and Joseph Rotblat). The book had recently reached its 20th anniversary when I talked to Dr. Steinberger. I had bought a copy soon after it was published in 1993, when I was a graduate student in physics and was considering a possible career in nuclear arms control. That book contains chapters by many of the major thinkers on nuclear issues including Richard Garwin, Carl Kaysen, Robert McNamara, Marvin Miller, Jack Ruina, Theodore Taylor, and several others. Some of these thinkers were or are affiliated with FAS.

While I do not intend to review the book here, let me highlight two ideas out of several insightful ones. First, the chapter by Joseph Rotblat, the long-serving head of the Pugwash Conferences, on “Societal Verification,” outlined a program for citizen reporting about attempted violations of a nuclear disarmament treaty. He believed that it was “the right and duty” for citizens to play this role. Asserting that technological verification alone is not sufficient to provide confidence that nuclear arms production is not happening, he urged that the active involvement of citizens become a central pillar of any future disarmament treaty. (Please see the article on Citizen Sensor in this issue of the PIR that explores a method of how to apply societal verification.)

The second concept that is worth highlighting is minimal deterrence. Nuclear deterrence, whether minimal or otherwise, has held back the cause of nuclear disarmament, as argued in a chapter by Dr. Steinberger, Essam Galal, and Mikhail Milstein. They point out, “Proponents of the policy of nuclear deterrence habitually proclaim its inherent stability… But the recent political changes in the Soviet Union [the authors were writing in 1993] have brought the problem of long-term stability in the control of nuclear arsenals sharply into focus. … This development demonstrates a fundamental flaw in present nuclear thinking: the premise that the world will forever be controllable by a small, static, group of powers. The world has not been, is not, and will not be static.”

Having laid bare this instability, they explain that proponents of a nuclear-weapon-free world also foresee that minimal deterrence will “encourage proliferation” because nations without nuclear weapons would argue that if minimal deterrence appears to strengthen security for the nuclear-armed nations, then why shouldn’t the non-nuclear weapon states have these weapons. After examining various levels for minimum nuclear deterrence, the authors conclude that any level poses a catastrophic risk because it would not “eliminate the nuclear threat.”

While Dr. Steinberger demurred that he has not actively researched nuclear arms control issues for almost 20 years, he is following the current nuclear political debates. He expressed concern that President Barack Obama “has said that he would lead toward nuclear disarmament but he hasn’t.” Dr. Steinberger emphasized that clinging to nuclear deterrence is “a roadblock” to disarmament and that “New START is too slow.”

On Iran, he said that if he were an Iranian nuclear scientist, he would want Iran to develop nuclear bombs given the threats that Iran faces. He underscored that if the United States stopped threatening Iran and pushed for global nuclear disarmament, real progress can be made in halting Iran’s drive for the latent capability to make nuclear weapons. He also believes that European governments need to decide to “get rid of U.S. nuclear weapons based in Europe.”

Another major interest of his is renewable energy that can provide reliable, around the clock electrical power. In particular, he has repeatedly spoken out in favor of solar thermal power. A few solar thermal plants have recently begun to show that they can generate electricity reliability even during the night or when clouds block the sun. Thus, they would provide “baseload” electricity. For example, the Gemasolar Thermosolar Plant in Fuentes de Andalucia, Spain, has an electrical power of 19.9 MW and uses a “battery” to generate power. The battery is a molten salt energy storage system that consists of a mixture of 60 percent potassium nitrate and 40 percent sodium nitrate. This mixture can retain 99 percent of the thermal energy for up to 24 hours. More than 2,000 specially designed mirrors, or “heliostats,” arrayed 360 degrees around a central tower, reflect sunlight onto the top part of the tower where the molten salt is heated up. The heated salt is then directed to a heat exchanger that turns liquid water into steam, which then spins a turbine coupled to an electrical generator.

Dr. Steinberger urges much faster accelerated development and deployment of these types of solar thermal plants because he is concerned that within the next 60 years the world will run out of relatively easy access to fossil fuels. He is not opposed to nuclear energy, but believes that the world will need greater use of true renewable energy sources.

Turning to the future of the Federation of American Scientists, Dr. Steinberger supports FAS because he values “getting scientists working together,” but he realizes that this is “hard to do” because it is difficult “to make progress in understanding issues” that involve complex politics. Many scientists can be turned off by messy politics and prefer to stick within their comfort zones of scientific research. Nonetheless, Dr. Steinberger urges FAS to get scientists to perform the research and analysis necessary to advance progress toward nuclear disarmament and to solve other challenging problems such as providing reliable renewable energy to the world.

50 Years Later “Dr. Strangelove” Remains a Must-See Film and Humorous Reminder of Our Civilization’s Fragility

Fifty years ago on January 30th, “Dr. Strangelove: Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying And Love the Bomb,” a seminal political-military satire and dark comedic film premiered. Based on Peter George’s novel Red Alert, the film gave us some of the most outrageously humorous and simultaneously satirical dialog in the history of the silver screen. For example, Peter Sellers as the President of the United States, “Gentleman, you cannot fight in here. This is the War Room.” Director/producer Stanley Kubrick produced a masterpiece that not only entertained viewers but turned out to be incredibly predictive about U.S.-Soviet Cold War nuclear policies, strategies, and outcomes.

The U.S. Air Force refused to cooperate with Kubrick and his production company because they felt that the premise of an accidental nuclear war being launched by a U.S. general wasn’t credible. In fact, on December 9, 1950, General Douglas MacArthur requested authorization to use atomic bombs against 26 targets in China after the People’s Liberation Army entered the Korean War. The Soviet Union had tested their first A-bomb the year before, so it is certainly possible that MacArthur’s use of such weapons could have triggered a nuclear conflict. In terms of nuclear accidents or “broken arrows” as the U.S. military refers to such events, there have been dozens of incidents including a January 17, 1966 Air Force crash involving nuclear warheads that contaminated thousands of acres in Palomares, Spain (although thankfully fail-safe switches on the damaged atomic bombs prevented any nuclear explosions). A computer generated false alert (one of countless false warnings over the years), on November 9, 1979 almost triggered nuclear Armageddon when President Jimmy Carter’s National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski was informed at 3 a.m. that 2,200 Soviet missiles were within minutes of impacting on the U.S. mainland. It turned out to be a training exercise loaded inadvertently into SAC’s early warning computer system.

Actor George C. Scott played a Strategic Air Command (SAC) general named Buck Turgidson not unlike real life Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Thomas Moorer. In 1969, Moorer proposed salvaging the war by targeting North Vietnam with two nuclear bombs – a proposal allegedly lobbied for by President Nixon’s Secretary of State Dr. Henry Kissinger. After it is discovered that Sterling Hayden’s character, General Jack D. Ripper has on his own authority (a credible possibility until coded locks were installed on most U.S. nuclear weapons later in the 1960s and on submarine-launched nuclear missiles in the late 1990s)1 ordered an all-out nuclear attack on Russia by his squadrons of B-52 bombers (an aircraft the United States still relies on after sixty years of deployment), General Turgidson pleads with Peter Sellers’ character President Merkin Muffley to consider, “…if on the other hand, we were to immediately launch an all-out and coordinated (nuclear) attack on all their airfields and missile bases, we’d stand a damn good chance of catching them with their pants down…I’m not saying we wouldn’t get our hair mussed, but I do say no more than 10-20 million (Americans) killed, tops, depending on the breaks.” Ironically nuclear war advocates Colin Gray and Keith Payne literally quoted Turgidson’s casualty figures verbatim when in 1980 they advised then presidential candidate Ronald Reagan that America could fight and win such a war against the Soviet Union.2

But Peter Sellers, who incredibly played three roles in the film, excelled as the title character Dr. Strangelove, an amalgam of NASA’s Werner von Braun, who built Nazi V-2 rockets by turning his back when SS soldiers worked thousands of Jewish conscripts to death and was part of Operation Paperclip, a group of German scientists amnestied by the United States (and the Soviet Union handpicked its own Nazi brainpower) after the war to help build Cold War weapons, Edward Teller, who worked on the hydrogen bomb, helped found Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, was an Atoms for Peace enthusiast and advocated for the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI- the “Star Wars” missile shield), and Herman Kahn, who worked at RAND, then founded the Hudson Institute, and wrote the seminal “thinking about the unthinkable” book On Thermonuclear War, published in 1960.

Deep in the bowels of the War Room, Dr. Strangelove responded to the Russian ambassador’s fearful notification that even if only one of the U.S. nuclear bombs struck Russia, the result would be the triggering of a doomsday machine. Sellers’ character admonished the ambassador, “But the whole point of a doomsday machine is lost if you keep it a secret. Why didn’t you tell the world, aye?” Coincidentally again, truth followed fiction according to David Hoffman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 2009 work The Dead Hand, as in November 1984, the Soviets did indeed construct a partially automated retaliatory nuclear strike system called Perimetr and tested it. Stranger still, Colonel Valery Yarynich of the Soviet Union’s Strategic Rocket Forces pointed out to his superiors that it was irrational and inconsistent with deterrence theory for them to go out of their way to hide Perimetr’s existence from U.S. leaders. This occurred during the height of the Cold War when the United States possessed 11,000 strategic nuclear warheads to the Soviet’s 9,900. In total, including tactical and intermediate-range bombs, the United States led 20,924 to 19,774 warheads.

When General Turgidson expressed skepticism that the Russians had the brains to build such a doomsday machine, Dr. Strangelove strongly disagreed, noting that such a system was entirely feasible. “The technology required is even within the means of the smallest nuclear power. It requires only the will to do so….It is remarkably simple to [build]. When you merely wish to bury bombs, there’s no limit to the size. After that they are connected to a gigantic complex of computers.” This echoed the real life February 1955 radio broadcast of German Nobel Laureate Otto Hahn, who first split the uranium atom in the late 1930s. Hahn warned that the detonation of as few as ten cobalt bombs, each the size of a naval vessel, would cause all mankind to perish. In the early 1980s, astronomer Carl Sagan and other scientists3 examined and subsequently built-on analyses of the last few decades via the TTAPS study. They concluded that as few as 100-200 nuclear warheads exploding within the span of a few hours could credibly trigger a nuclear winter, plunging temperatures dramatically in the northern hemisphere as tremendous nuclear firestorms block the sun’s rays, leading to wholesale starvation, exposure, and the radiation-borne deaths of billions of people worldwide.4

Dr. Strangelove was originally scheduled for its first screening on Friday, November 22, 1963. The assassination of President Kennedy earlier that day caused the producers to delay the film’s release date by several weeks. Time was needed to not only heal the nation’s gaping wound but to edit the film to remove some objectionable material relating to the murder of the president. Coincidental references by the hydrogen bomb-riding Slim Pickens character Major T.J. “King” Kong that the survival kits carried by each bomber crewman could help provide them a pretty good time in Dallas was redubbed to “Vegas.” A concluding sequence of a free-for-all pie fight in the War Room was edited out for stylistic reasons and also removed George C. Scott’s objectionable dialogue that, “Our commander-in-chief has been struck down in the prime of his life.” Not so coincidentally, perhaps, JFK’s murder and Nikita Khrushchev’s Politburo ouster in 1964 (the year of the film’s actual release), ended a post-Cuban Missile Crisis-Almost Armageddon (October 1962) apotheosis by both leaders to prevent another nuclear crisis. They cooperated in an earnest effort to prevent another visit to the brink of extinction by working to end the Cold War and reverse the nuclear arms race in favor of peaceful coexistence. The results of their labors cannot be underestimated—the Hot Line Agreement and the Limited Test Ban Treaty.

Today in 2014, “Dr. Strangelove,” along with other antiwar films like “Fail Safe,” “The Sum of All Fears,” “On the Beach,” “War Games,” and “Olympus Has Fallen,” remind us that all of humanity must acknowledge that nuclear war is not a blast from the past or an obsolete fear from a remote period in history. It is a real life current and future threat to our global civilization – indeed to our species’ continued existence on this planet.

But has anyone studied the actual possibilities of a nuclear Armageddon? Aside from Dr. Strangelove’s analysis discussing a study on nuclear war made by “the Bland Corporation” (which is obviously a reference to the real-life Rand Corporation), the answer is a definitive “yes.” According to Ike Jeane’s 1996 book Forecast and Solution: Grappling with the Nuclear, the risks of large-scale nuclear war average about 1-2 percent per year, down from a high of 2-3 percent annually during the Cold War (1945-1991). But Dr. Martin Hellman of Stanford and other analysts believe that as more decades pass since the only recorded use of nuclear weapons in combat (Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945), the probability may increase to ten percent over the duration of this century.5

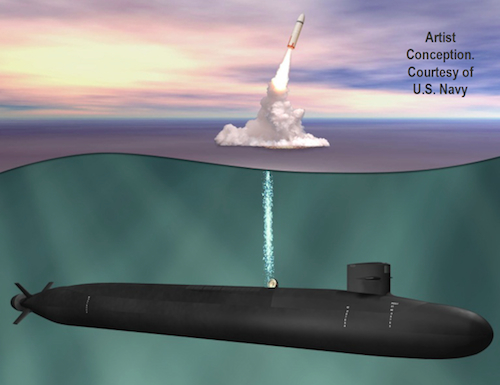

While President Barack Obama has called for the elimination of nuclear weapons, so too have past American leaders as diverse politically as Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, and Ralph Nader. Meanwhile thousands of nuclear warheads – 90-plus percent in the hands of America and Russia – still exist in global arsenals. Both countries continue to spend tens of billions of dollars annually to update, improve, and modernize their nuclear forces. For example, U.S. submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) have increased dramatically in accuracy from a 12 percent chance of destroying a hardened Russian missile silo to 90-98 percent effectiveness; thus giving these weapons a highly effective “kill” probability and putting pressure on Russia to launch its silo-based ballistic missiles on warning of attack. While U.S. missile “defenses” may soon include “Rods from God,” 20-30 foot long, two-foot wide tungsten cylinders fired from U.S. Air Force space-based assets, the Russians have also upgraded their aging Cold War arsenal by building dozens of new Topol-M ICBMs and Bulava SLBMs.

Substantial progress in reducing this Armageddon threat cannot be accomplished until decades-long objections by overly conservative members of Congress, the Russian Duma and both nations’ military leadership are lifted. Such multilateral, verifiable (new technologies make this relatively easy to achieve), measures include a global comprehensive nuclear test ban (laboratory sub-critical nuclear tests not excluded), and the standing down from heightened alert levels of not only Russian and American strategic and tactical nuclear weapons but those of China, France, Britain, Israel, Pakistan and India. This would transition all sides’ dangerous nuclear weapons from the physical capability of being fired in 15 minutes or less to 72 hours or longer—don’t we at least deserve three days to think about it before we destroy the world? We also need an accelerated global zero nuclear reduction agreement as well as an essential, little-mentioned but critically important move that the mainstream corporate media has rarely granted its stamp of legitimacy. This would be a unanimous United Nations demand as voiced by leaders in America and Russia, for the phase-out of all nuclear power plants, research as well as production facilities (with the exception of a handful of super-guarded medical radioisotope manufacturing and storage facilities) in the next 10-15 years.

Eliminating not just existing stocks of nuclear weapons, but also all of the 400 global nuclear power facilities is the trump card in the deck of human long-term survival. There are numerous issues including: proliferation, nuclear accidents, the long-term sequestration of tremendous amounts of deadly nuclear wastes, the economic non-competitiveness of nuclear energy, and the realization that nuclear plants are not a viable, safe or reasonable solution to global warming especially in the long term (since plutonium-239 has a half-life of an amazing duration of more than 20,000 years)! Dr. Strangelove’s circular slide rule-assisted calculation requiring humanity to survive the war by remaining in deep underground mineshaft spaces for merely a century was ergo a definite miscalculation—sorry Herr Merkwurdichliebe. 6

Five decades later, the hauntingly humorous end title lyrics and music of “Dr. Strangelove,” accompanied by actual images of awesome Cold War-era nuclear tests, serves as a read-between-the-lines warning to the human race: “We’ll meet again, don’t know where, don’t know when, but I know we’ll meet again some sunny day.” Nuclear weapons and nuclear power – indistinguishable in terms of the deadly threat to our species – must be eliminated now before it is too late. A penultimate but overwhelmingly appropriate edit of George C. Scott’s last line in the film is especially relevant here. “We must not allow a nuclear Armageddon!”

Additional Sources

Walter J. Boyne, Beyond the Wild Blue: A History of the U.S. Air Force, 1947- 1997, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997, p. 394.

Columbia Pictures Corporation-Sony Pictures, 40th Anniversary Edition: Dr. Strangelove. Documentary- “Inside Dr. Strangelove,” 2004.

Bruce Cumings, The Origins of the Korean War, Volume 2. Princeton University Press, 1990, pp. 749-751.

The Defense Monitor (Center for Defense Information), Vol. 15, No. 7, “Accidental Nuclear War: A Rising Risk?” by Michelle Flournoy, 1986.

The Defense Monitor (Center for Defense Information), Vol. 36, No. 3, “Primed and Ready- Special Report: Nuclear Issues,” by Bruce G. Blair, May/June 2009.

Peter Janney, Mary’s Mosaic: The CIA Conspiracy to Murder John F. Kennedy, Mary Pinchot Meyer, and Their Vision for World Peace. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, 2012, pp. 242-247; 261-263.

Premiere (Magazine), “The 100 Greatest Movie Characters of All-Time,” April 2004, p. 58.

Carl Sagan, “The Case Against SDI,” Discover, September 1985, pp. 66-75.

H. Eric Semler, et al., The Language of Nuclear War: An Intelligent Citizen’s Dictionary. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1987, p. 44.

Oliver Stone and Peter Kuznick, The Untold History of the United States. New York: Gallery Books-Simon & Schuster, 2012, pp. 272, 362, 540-42.

John Tierman, editor, Empty Promise: The Growing Case Against Star Wars. Boston:

Beacon Press, 1986, pp. 2-3.

Louis Weber, editor, Movie Trivia Mania. Beekman House-Crown Publishers, Inc., 1984 p. 21.

Jeffrey W. Mason is a nuclear weapons, arms control, outer space, and First Contact scholar, published author and scriptwriter for acclaimed PBS-TV documentaries who possesses two MA degrees—one in international security. He has worked for the Center for Defense Information (11 years) where he helped produce award-winning PBS-TV documentaries on child soldiers, the Hiroshima bombing, and “The Nuclear Threat at Home.” He worked for the Defense Threat Reduction Agency, the State Department, Professionals’ Coalition for Nuclear Arms Control, Congressional Research Service, Amnesty International, Clean Water Action, and the International Studies Association.

Hedging and Strategic Stability

The concept of strategic stability emerged during the Cold War, but today it is still unclear what the term exactly means and how its different interpretations influence strategic decisions. After the late 1950s, the Cold War superpowers based many of their arguments and decisions on their own understanding of strategic stability1 and it still seems to be a driving factor in the arms control negotiations of today. However, in absence of a common understanding of strategic stability, using this argument to explain certain decisions or threat perceptions linked to the different aspects of nuclear policy tend to create more confusion than clarity.

In the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) report,2 the Obama administration used the term strategic stability as a central concept of U.S. nuclear policy vis-à-vis Russia and China. Altogether it appeared 29 times in the report, in reference to issues mostly related to nuclear weapons capabilities. In the U.S.-Russian bilateral relationship, strategic stability was associated with continued dialogue between the two states to further reduce U.S.-Russian nuclear arsenals, to limit the role of nuclear weapons in national security strategies, and to enhance transparency and confidence-building measures. At the same time, the United States pledged to sustain a safe, secure, and effective nuclear arsenal by modernizing its nuclear forces, retaining the triad, and “hedging against potential technical problems or vulnerabilities.”

On the other hand, Russia seems to use the term strategic stability in a broader context, claiming that the question of ballistic missile defense, conventional prompt global strike, and the militarization of outer space all affect strategic stability between Moscow and Washington. U.S. modernization efforts in these areas are seen as attempts to undermine the survivability of the Russian nuclear arsenal and steps to gain strategic advantage over Russia. Therefore, Moscow has been repeatedly arguing that any future arms control agreement should address all factors which affect strategic stability.3

Although these are the issues which Russia explicitly mentions in reference to strategic stability, there is another “hidden” issue which might also have a counterproductive impact on long term stability because of its potential to undermine strategic parity (which seems to be the basis of Russian interpretation of strategic stability).4 This issue is the non-deployed nuclear arsenal of the United States or the so-called “hedge.”

During the Cold War, both superpowers tried to deploy the majority of their nuclear weapons inventories. Reserve nuclear forces were small as a result of the continuous development and production of new nuclear weapons, which guaranteed the rapid exchange of the entire stockpile in a few years. The United States started to create a permanent reserve or hedge force in the early 1990s. The role of the hedge was twofold: first, to guarantee an up-build capability in case of a reemerging confrontation with Russia, and second, a technical insurance to secure against the potential failure of a warhead type or a delivery system. Despite the dissolution of the Soviet Union, during the first years of the 1990s, the United States was skeptical about the democratic transition of the previous Eastern Block and the commitment of the Russian Federation to arms control measures in general. Therefore, the Clinton administration’s 1994 NPR officially codified – for the first time – the concept of a hedge force against the uncertainties and the potential risks of the security environment.5 This concept gradually lost importance as the number of deployed strategic and non-strategic nuclear weapons kept shrinking on both sides and relations improved between Washington and Moscow. By the end of the 1990s, the main rationale for upholding the hedge force shifted towards the necessity of maintaining a back-up against technical failures. Although the nuclear arsenal was aging, a moratorium was declared on nuclear weapons testing, and several production facilities were closed. Therefore, it seemed imperative to retain fully functional nuclear warheads in reserve as an insurance policy.6

While the Clinton administration’s NPR was not too explicit about what the hedge really was, both the Bush and the Obama administrations made the specific role of the hedge clearer. Although technical considerations remained important, the Bush administration’s 2001 NPR refocused U.S. hedging policy on safeguarding against geopolitical surprises. The administration tried to abandon Cold War “threat-based” force planning and implemented a “capabilities-based” force structure which was no longer focused on Russia as an imminent threat but broadened planning against a wider range of adversaries and contingencies: to assure allies, deter aggressors, dissuade competitors and defeat enemies.7 This shift in planning meant that the force structure was designed for a post-Cold War environment with a more cooperative Russia. Therefore, the primary goal of the hedge was to provide guarantees in case this environment changed and U.S.-Russian relations significantly deteriorated.

Regardless of the main focus of the acting administration, the hedge has always served two different roles which belong to two separate institutions: the military considers the hedge a responsive force against the uncertainties of the international geopolitical environment, while the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) views the hedge as a repository to safeguard the aging U.S. nuclear arsenal. These two institutions advise the administration on the required size of the hedge. Since the end of the Cold War, both the United States and Russia considerably reduced their deployed nuclear warheads, but Washington retained many of these weapons in the hedge. By now there are more non-deployed nuclear weapons than deployed nuclear weapons in its military stockpile.

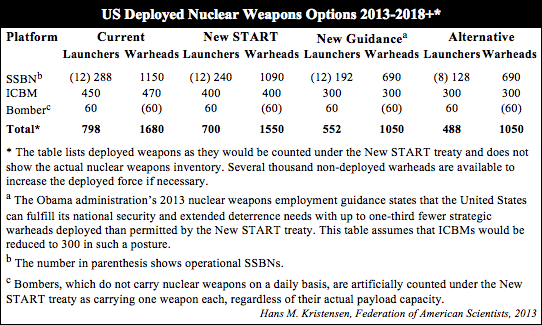

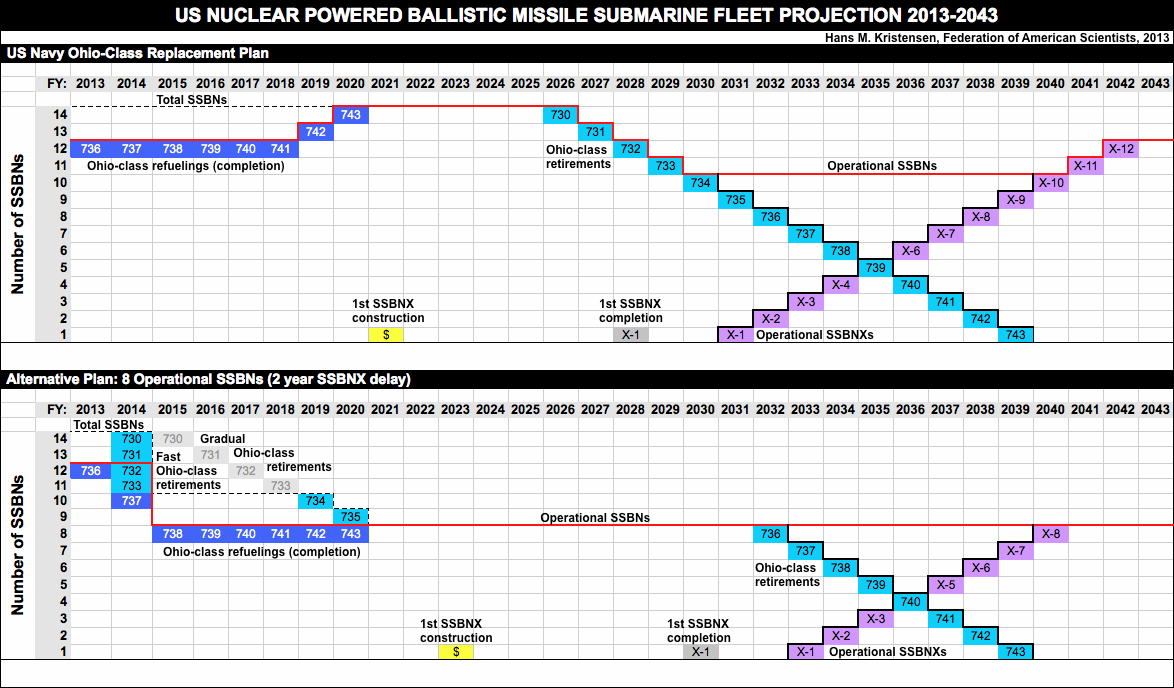

According to the Federation of American Scientists,8 the United States has a military stockpile of 4,650 nuclear weapons, of which roughly 1,900 strategic nuclear weapons are deployed (this includes bomber weapons on bomber bases as deployed) and another approximately 200 non-strategic nuclear weapons are deployed in Europe. Altogether this leaves around 2,500 non-deployed nuclear weapons in reserve – approximately 2,200 strategic and 300 non-strategic.9 This hedge force10 provides the United States with a capability to increase its deployed nuclear arsenal to more than 4000 nuclear weapons within three years.11 In the long run, this capability might feed into Russian paranoia over anything that can potentially undermine strategic parity and it could become a serious roadblock on the way toward further reductions in deployed strategic as well as non-strategic nuclear arsenals.

The Obama administration has already indicated in the 2010 NPR that it is considering reductions in the nuclear hedge. According to the document, the “non-deployed stockpile currently includes more warheads than required” and the “implementation of the Stockpile Stewardship Program and the nuclear infrastructure investments” could set the ground for “major reductions” in the hedge. However, in parallel to these significant reductions, the United States “will retain the ability to ‘upload’ some nuclear warheads as a technical hedge against any future problems with U.S. delivery systems or warheads, or as a result of a fundamental deterioration of the security environment.” In line with the 2010 NPR, the 2013 Presidential Employment Guidance also envisions reductions in the deployed strategic nuclear arsenal and reaffirms the intention to reduce the hedge as well. The Pentagon report on the guidance12 discusses an “alternative approach to hedging” which would allow the United States to provide the necessary back-up capabilities “with fewer nuclear weapons.” This alternative approach puts the main emphasis on the technical role of the hedge, claiming that “a non-deployed hedge that is sized and ready to address these technical risks will also provide the United States the capability to upload additional weapons in response to geopolitical developments.” According to Hans Kristensen, Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists, this might imply that the hedge will no longer contain two categories of warheads – as there will be enough reserve warheads to protect against technical failures and potential geopolitical challenges.13 However, at this point it is still unclear if (and when) this new approach will lead to actual force reductions in the non-deployed nuclear arsenal.

In the meantime, the United States could achieve several benefits by reducing the hedge. First, reducing the number of warheads (which require constant maintenance and periodic life extension) could save a few hundred million dollars in the federal budget. Second, it could send a positive signal to Russia about U.S. long-term intentions. In his 2013 Berlin address, President Obama indicated that his administration would seek “negotiated cuts with Russia” to reduce the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons below the ceilings of the New START Treaty.14 In terms of deployed strategic nuclear weapons, Moscow has already met the limits of the Treaty and seems to be reluctant to negotiate any further cuts until the 2018 New START implementation deadline or until the United States also meets the Treaty limits15 (which – in light of the current trends – is probably not going to happen earlier than 2018). In addition, the deeper the two sides reduce their deployed strategic nuclear arsenals, the harder Russia tries to press the United States to include all other issues which affect strategic stability (especially ballistic missile defense). The United States has tried to alleviate Russian concerns over missile defense by offering some cooperative and transparency measures but Moscow insists that a legally binding treaty is necessary, which would put serious limits on the deployment of the system (a condition that is unacceptable to the United States Congress at the moment). Therefore, the future of further reductions seems to be blocked by disagreements over missile defense. But the proposed reduction of the hedge could signal U.S. willingness to reduce its strategic advantage against Russia.

Despite the potential benefits, U.S. government documents16 have been setting up a number of preconditions for reducing the size of the hedge. Beyond “geopolitical stability,” the two most important preconditions are the establishment of a responsive infrastructure by constructing new warhead production facilities and the successful completion of the warhead modernization programs. The Department of Energy’s FY 2014 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) proposes a so-called 3+2 warhead plan that would create three interoperable warheads for ballistic missiles and two for long-range bombers.17 The transition to interoperable warheads could, according to the plan, permit a reduction of the number of warheads in the hedge. In light of the current budget constraints, it is still unclear if the program will start as planned and even if completed according to schedule, the gradual reduction of the technical hedge would not begin until the mid-2030s. Similar challenges will arise if the administration wishes to link the reduction of the hedge to the construction of new warhead production facilities – some of which have already been delayed due to budget considerations, and the exact dates and technical details of their future completion are still unclear.

The preconditions would mean that significant reductions in the hedge18 are unlikely to materialize for at least another 15 years. Meanwhile, the deployed arsenal faces two scenarios in the coming decades: the number of warheads and delivery platforms could keep shrinking or arms control negotiations might fail to produce further reductions as a result of strategic inequalities (partly caused by the huge U.S. non-deployed arsenal). Under the first scenario, keeping the hedge in its current size would be illogical because a smaller deployed arsenal would require fewer replacement warheads19 in case of technical failures, and because fewer delivery platforms would require fewer up-load warheads in case of geopolitical surprises. Maintaining the current non-deployed arsenal would not make any more sense under the second scenario either. If future arms control negotiations get stuck based on arguments over strategic parity, maintaining a large hedge force will be part of the problem, not a solution. Therefore, insisting on the “modernization precondition” and keeping the current hedge for another 15 years would not bring any benefits for the United States.

On the other hand, President Obama could use his executive power to start gradual reductions in the hedge. Although opponents in Congress have been trying to limit his flexibility in future nuclear reductions (which could happen in a non-treaty framework), current legislative language does not explicitly limit cuts in the non-deployed nuclear arsenal. After the successful vote on the New START Treaty, the Senate adopted a resolution on the treaty ratification which declares that “further arms reduction agreements obligating the United States to reduce or limit the Armed Forces or armaments of the United States in any militarily significant manner may be made only pursuant to the treaty-making power of the President.”20 However, if gradual cuts in the hedge would not be part of any “further arms reduction agreement” but instead implemented unilaterally, it would not be subject to a new legally binding treaty (and the necessary Senate approval which comes with it). Similarly, the FY2014 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which was adopted in December 2013, does not use explicit language against unilateral reductions in the hedge.21 The NDAA only talks about preconditions to further nuclear arms reductions with Russia below the New START Treaty levels and it does not propose any limitations on cutting the non-deployed arsenal. In fact, the NDAA encourages taking into account “the full range of nuclear weapons capabilities,” especially the non-strategic arsenals – and this is exactly where reducing the United States hedge force could send a positive message and prove beneficial.

The 2013 Presidential Employment Guidance appears to move towards an alternative approach to hedging. This new strategy implies less reliance on non-deployed nuclear weapons which is a promising first step towards their reduction. However, the FY 2014 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan links this reduction to the successful completion of the ongoing nuclear modernization programs, anticipating that the number of warheads in the hedge force will not change significantly in the near future. Its fate will mainly depend on congressional budget fights.

This might send a bad signal to Russia, where U.S. missile defense developments and its alleged impact on strategic stability are already a primary source of concern to the Kremlin. As a result of aging technologies and necessary retirements, Russian nuclear forces have been constantly decreasing, and despite all modernization efforts,[ref]Russian has an ongoing modernization program, in the framework of which it has already begun to build a new heavy ICBM and a multiple-warhead Bulava SLBM.[/ref] it is expected that by the early 2020s the ICBM arsenal will shrink to 220 missiles.22 Russia already deploys 40 percent less strategic delivery systems than the United States and tries to keep the balance of deployed weapons by higher warhead loadings. This does not give Russia the ability to significantly increase the deployed number of warheads – not just because of the lower number of delivery vehicles but also because of the lack of reserve warheads comparable in number to the United States hedge force. In this regard there is an important asymmetry between Russia and the United States – while Washington keeps a hedge for technical and geopolitical challenges, Moscow maintains an active production infrastructure, which – if necessary – enables the production of hundreds of new weapons every year. It definitely has its implications for the long term (10-15 years) status of strategic parity, but certainly less impact on short term prospects.

In the meantime, the United States loads only 4-5 warheads on its SLBMs (instead of their maximum capacity of 8 warheads) and keeps downloading all of its ICBMs to a single warhead configuration.23 Taken into account the upload potential of the delivery vehicles and the number of warheads in the hedge force, in case of a dramatic deterioration of the international security environment the United States could increase its strategic nuclear arsenal to above 4000 deployed warheads in about three years.

Whether one uses a narrow or a broader interpretation of strategic stability, these tendencies definitely work against the mere logic of strategic parity and might have a negative effect on the chances of further bilateral reductions as well. Cutting the hedge unilaterally would definitely upset Congress and it could endanger other foreign policy priorities of the United States (such as the CTBT ratification or negotiations with Iran), but it would still be worth the effort as it could also indicate good faith and contribute to the establishment of a more favorable geopolitical environment. It could signal President Obama’s serious commitment to further disarmament, send a positive message to Russian military planners and ease some of their paranoia about U.S. force structure trends.

Anna Péczeli is a Fulbright Scholar and Nuclear Research Fellow at the Federation of American Scientists. Additionally, Péczeli is an adjunct fellow at the Hungarian Institute of International Affairs, where she works on nuclear arms control. Péczeli earned a master’s degree in international relations from Corvinus University of Budapest, and is currently working on her doctoral dissertation, which focuses on the Obama administration’s nuclear strategy.

President’s Message: Legitimizing Iran’s Nuclear Program

Be careful of self-fulfilling prophecies about the intentions for Iran’s nuclear program. Often, Western analysts view this program through the lens of realist political science theory such that Iranian leaders seek nuclear weapons to counteract threats made to overthrow their regime or to exert dominance in the Middle East. To lend support to the former argument, Iranian leaders can point to certain political leaders in the United States, Israel, Saudi Arabia, or other governments that desire, if not actively pursue, the downfall of the Islamic Republic of Iran. To back up the latter rationale for nuclear weapons, Iran has a strong case to make to become the dominant regional political power: it has the largest population of any of its neighbors, has a well-educated and relatively technically advanced country, and can shut off the vital flow of oil and gas from the Strait of Hormuz. If Iran did block the Strait, its leaders could view nuclear weapons as a means to protect Iran against attack from powers seeking to reopen the Strait. (Probably the best deterrent from shutting the Strait is that Iran would harm itself economically as well as others. But if Iran was subject to crippling sanctions on its oil and gas exports, it might feel compelled to shut down the Strait knowing that it is already suffering economically.) These counteracting external threats and exerting political power arguments provide support for the realist model of Iran’s desire for nuclear bombs.

But viewed through another lens, one can forecast continual hedging by Iran to have a latent nuclear weapons capability, but still keeping barriers to proliferation in place such as inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). In particular, Iranian leaders have arguably gained considerable political leverage over neighbors by just having a latent capability and have maintained some legitimacy for their nuclear program by remaining part of the IAEA’s safeguards system.

If Iran crosses the threshold to make its own nuclear weapons, it could stimulate neighbors to build or acquire their own nuclear weapons. For example, Saudi leaders have dropped several hints recently that they will not stand idly by as Iran develops nuclear weapons. The speculation is that Saudi Arabia could call on Pakistan to transfer some nuclear weapons or even help Saudi Arabia develop the infrastructure to eventually make its own fissile material for such weapons. Pakistan is the alleged potential supplier state because of stories that Saudi Arabia had helped finance Pakistan’s nuclear weapons program and thus, Islamabad owes Riyadh for this assistance. Moreover, Pakistan remains outside the Non-Proliferation Treaty and therefore would not have the treaty constraint as a brake on nuclear weapons transfer. Furthermore, one could imagine a possible nuclear cascade involving the United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and Egypt, all states that are developing or considering developing nuclear power programs. This proliferation chain reaction would likely then undermine Iran’s security and make the Middle East further prone to potential nuclear weapons use.

I would propose for the West to act optimistically and trust but verify Iran’s claim that its nuclear program is purely for peaceful purposes. The interim deal that was recently reached between Iran and the P5+1 (the United States, Russia, France, China, United Kingdom, and the European Union) is encouraging in that it places a temporary halt on some Iranian activities such as construction of the 40 MW reactor at Arak, the further enrichment of uranium to 20 percent uranium-235 (which is about 70 percent of the work needed to reach the weapons-grade level of 90 percent uranium-235), and continued expansion of the enrichment facilities. Iran also has become more open to the IAEA’s inspections. But these are measures that can be readily reversed if the next deal cannot be negotiated within the next several months. Iran is taking these actions in order to get relief from some economic sanctions.

Without getting into the complexities of the U.S. and Iranian domestic politics as well as international political considerations, I want to outline in the remaining part of this president’s message a research agenda for engineers and scientists. I offer FAS as a platform for these technical experts to publish their analyses and communicate their findings. Specifically, FAS will create a network of experts to assess the Iranian nuclear issues, publish their work on FAS.org, and convene roundtables and briefings for executive and legislative branch officials.

Let’s look at the rich research agenda, which is intended to provide Iran with access to a suite of peaceful nuclear activities while still putting limits on the latent weapons capacity of the peaceful program. By doing so, we can engender trust with Iranians, but this will hinge on adequate means to detect breakout into a nuclear weapons program.

First, consider the scale of Iran’s uranium enrichment program. It is still relatively small, only about a tenth of the capacity needed to make enough low enriched uranium for even the one commercial nuclear plant at Bushehr. Russia has a contract with Iran for ten years of fuel supply to Bushehr. If both sides can extend that agreement over the 40 or more years of the life of the plant, then Iran would not have the rationale for a large enrichment capacity based on that one nuclear plant. However, Iran has plans for a major expansion of nuclear power. Would it be cost effective for Iran to enrich its own uranium for these power plants? The short answer is no, but because of Iranian concerns about being shut out of the international enrichment market and because of Iranian pride in having achieved even a modestly sized enrichment capacity, Iranian leaders will not give up enrichment. I would suggest that a research task for technical experts is to work with Iran to develop effective multi-layer assurances for nuclear fuel. Another task is to assess what capacity of enrichment is appropriate for the existing and under construction research and isotope production reactors or for smaller power reactors. These reactors require far less enrichment capacity than a large nuclear power plant. A first order estimate is that Iran already has the right amount of enrichment capacity to fuel the current and planned for research reactors. But nuclear engineers and physicists can and should perform more detailed calculations.

One reactor under construction has posed a vexing challenge; this is the 40 MW reactor being built at Arak. The concern is that Iran has planned to use heavy water as the moderator and natural uranium as the fuel for this reactor. (Heavy water is composed of deuterium, a heavy form of hydrogen with a proton and neutron in its nucleus, rather than the more abundant “normal” hydrogen, with a proton in its nucleus, which composes the hydrogen atoms in “light” or ordinary water.) A heavy water reactor can produce more plutonium per unit of power than a light water reactor because there are more neutrons available during reactor operations to be absorbed by uranium-238 to produce plutonium-239, a fissile material. The research task is to develop reactor core designs that either use light water or use heavy water with enriched uranium. The light water reactor would have to use enriched uranium in order to operate. A heavy water reactor could also make use of enriched uranium in order to reduce the available neutrons. Another consideration for nuclear engineers who are researching how to reduce the proliferation potential of this reactor is to determine how to lower the power rating, while still providing enough power for Iran to carry out necessary isotope production services and scientific research with the reactor. The 40 MW thermal power rating implies that if operated at near full power for a year, this reactor can make one to two bombs’ worth of plutonium annually. Another research problem is to design the reactor so that it is very difficult to use in an operational mode to produce weapons-grade plutonium. Safeguards and monitoring are essential mechanisms to forestall such production but might not be adequate. Here again, research into proliferation-resistant reactor designs would shed light on this problem.

Regarding isotope production, further research and development would be useful to figure out if non-reactor alternative technologies such as particle accelerators can produce the needed isotopes at a reasonable cost. Derek Updegraff and Pierce Corden of the American Association of the Advanced of Science have been investigating alternative production methods. Science progresses faster when additional researchers investigate similar issues. Thus, this research task could bear considerable fruit if teams can develop cost effective non-reactor means to produce medical and other industrial isotopes in bulk (or whatever quantity is required). If such development is successful, Iran and other countries could retire isotope production reactors that could pose latent proliferation concerns.

Finally, I will underscore perhaps the biggest research challenge: how to ensure that the Iranian nuclear program is adequately safeguarded and monitored. One of the next important steps for Iran is to apply a more rigorous safeguards system called the Additional Protocol and for a period of time, perhaps from five to ten years, apply inspection measures that go beyond the requirements of the Additional Protocol in order to instill confidence in the peaceful nature of Iran’s nuclear program. Dozens of states have ratified the Additional Protocol, which requires the IAEA to assess whether there are any undeclared nuclear material and facilities in the country being inspected. The Additional Protocol was formed in response to the finding in 1991 in Iraq that Saddam Hussein’s nuclear technicians were getting close to producing fissile material for nuclear weapons, despite the fact that Iraq was subject to regular IAEA inspections of its declared nuclear material and facilities. The undeclared facilities were often physically near declared facilities. There are concerns that given the large land area of Iran, clandestine nuclear facilities might go unnoticed by the IAEA or other means of detection and thus pose a significant risk for proliferation. The research task is to find out if there are effective means to find such clandestine facilities and to provide enough warning before Iran would be able to make enough fissile material and form it into bombs.

A key consideration of any part of this research agenda is how to cooperate with Iranian counterparts. For this plan to be acceptable and achievable, Iranian engineers, scientists, and leaders must own these concepts and believe that the plan supports their objectives to have a legitimate nuclear program that can generate electricity, produce isotopes for medical and industrial purposes, and provide other peaceful benefits including scientific research. Thus, we will need to leverage earlier and ongoing outreach to Iran by organizations such as the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advance of Science, and the Richard M. Lounsbery Foundation. Future workshops with Iranian counterparts are essential and companion studies by these counterparts would further advance the cause of legitimizing the Iranian nuclear program.

Several scientists and other technically trained experts in the United States have already been assessing aspects of this agenda as I indicated above with the mention of Updegraff and Corden’s research. Also, without meaning to slight anyone I may not know of or forget to mention, I would call out David Albright and his team at the Institute for Science and International Security, Richard Garwin of IBM, Frank von Hippel and colleagues at Princeton University, and Scott Kemp of MIT. This group is doing insightful work, but I believe that getting more engineers and scientists involved would bring more diverse ideas and more technical expertise to bear on this challenge to international security.

Engineers and scientists have a fundamental role to play in explaining the technical options to policy makers. For FAS, in particular, such work will help revitalize the organization as a true federation of scientists and engineers dedicated to devoting their talents to a more secure and safer world. FAS invites you to contact us if you have skills and knowledge you want to contribute to this proposal to help ensure Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, Federation of American Scientists

A Citizen Approach to Nonproliferation

Have you ever watched a football match where thousands of attendees witness an event that the officials missed? Sometimes there is wisdom in the crowd, especially a crowd who understand the rules of the game. Officials, no matter how dedicated and hardworking they may be, cannot be everywhere or look everywhere at every moment. Indeed, sometimes just one set of eyes can call attention to what should have been obvious or would have been missed.

Consider the individual with administrative responsibilities working for an import/export company who has been told that the company works on the acquisition of farming equipment. Invoices and shipment information cross their desk for large diameter carbon fiber tubes or those made from maraging steel or high-speed electronics, potential items for a gas centrifuge uranium enrichment facility or nuclear weapons detonation fire sets. Maybe they are laborers in the company’s receiving facility and are responsible for uncrating and repackaging these purchases. They are witnesses to illegal activities and, if they remain uninformed, these individuals would simply go about their everyday tasks.

Shouldn’t we consider a way to reach the citizens of the world to make the world a safer place? Shouldn’t we explore how the power of the web and crowdsourcing might have a profound impact in the area of nonproliferation? Part of the power of the web is how inexpensive it is to explore concepts and allow users to vote with their participation and support.

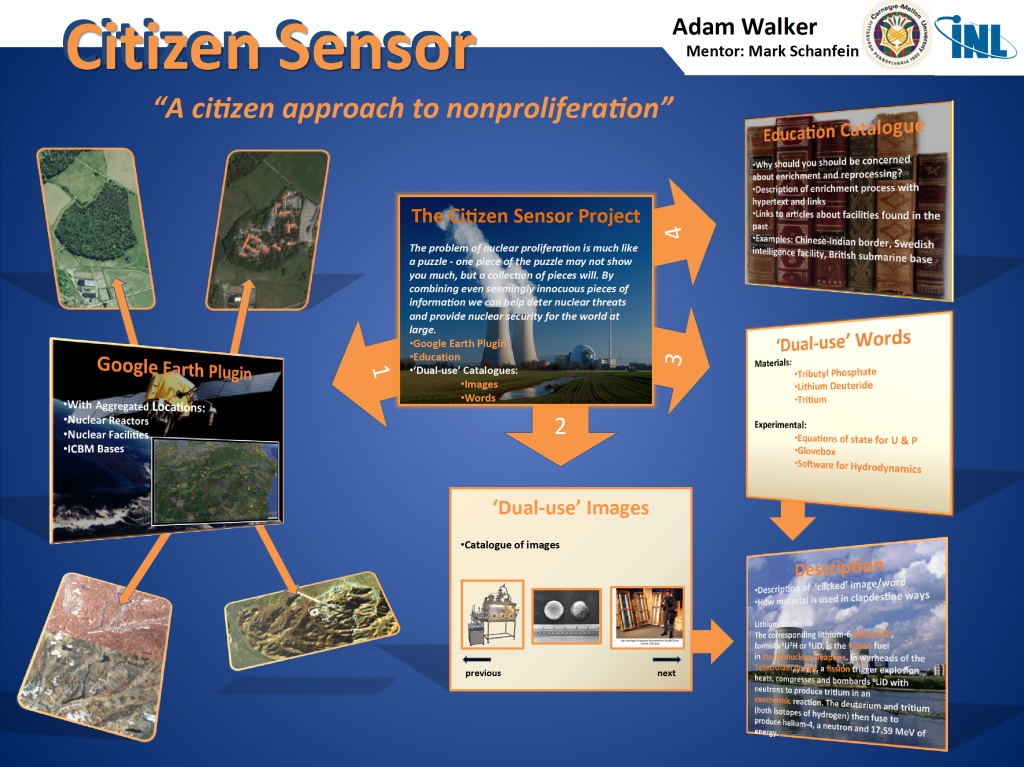

This article describes the concept of Citizen Sensor1, which aims at leveraging citizens around the world to further strengthen the nonproliferation and international safeguard regime. Start by imagining a world with new and inexpensive methods of vigilance against the spread of nuclear weapons by producing as many knowledgeable citizens as possible – using the observations of crowds and attentive individuals through the power of the web.

The detection of undeclared nuclear facilities and nuclear weapons programs is unequivocally the greatest challenge facing the International Atomic Energy Agency. The common theme for all nuclear nonproliferation challenges is the exposure of people to information, but they are often unaware of the actual application or nature of their work or of the items and activities they see. Or, even if they are aware, they are not sure where to turn to or how to safely inform others. By using the web as both an education tool and a reporting platform, Citizen Sensor aims to alert them to this type of threat, instruct them on how they can help with early detection through education and vigilance and share their knowledge to try to deter those who seek to create a nuclear weapon or other weapons of mass destruction. From the proposed website: “The problem of nuclear proliferation is much like a puzzle – one piece of the puzzle may not show you much, but a collection of pieces will. By combining even seemingly innocuous pieces of information we can help deter nuclear threats and provide nuclear security for the world at large.”

Elements of the Internet-based Citizen Sensor Culture

A variety of potential elements could influence the creation of the Citizen Sensor. These include:

- Proliferation indicator training – What are the most important signs that might indicate proliferation is happening and how do you watch for them? Citizen Sensor would educate the web-based community as a formidable mechanism for early detection of the construction of clandestine nuclear facilities and discovery of weaponization activities. The website would allow education through words and pictures.

- “Neighborhood Watch” as a sharing platform – Post your evidence/suspicions anonymously or signed for discussion and analysis by the crowd.

- “Amber” or “911” type alert for urgent real-time events – If nuclear or radiological material or sensitive information goes missing, mobilize people to help law enforcement find them.

- “Suggestion” box – What are your ideas on how to improve a Citizen Sensor website?

- Testimonials – What supporting activities can be shared with the general public in order to encourage this work?

The concept of Citizen Sensor reaches beyond its website; it would leverage information and capabilities on other websites (such as the IAEA, Google Earth, and Wikipedia) and it will develop an international culture of informed training, watchfulness, and reflection regarding proliferation, coupled with statistical and social science analysis of the information exchanges and discussions that transpire.

Citizen Sensor would include tools for education, information discovery, and anonymous reporting, and could serve as a test bed for other researchers to experiment with specific data processing and social science techniques. These include incentives for the public to participate and methods to screen for incorrect information.

Training modules on all elements of the nuclear fuel cycle, single/dual use items, and aspects of weaponization would be developed, along with search tools to allow users to discover any linkages/matches from their “found” information to be translated into written and/or visual knowledge.

A successful Citizen Sensor website would catalyze a watchful and credible culture of citizen sensors – a worldwide community that produces potential actionable threats and concerns that those with authority and power would consider and act upon. It could be a significant deterrent to proliferators, as it targets the very human resources they count on.

As smart phones continue to grow in computational and sensor capability, new applications continue to arise. GammaPix™ works with the camera of iPhones2 and Android-based3 smart phones to detect radioactivity. The app allows you to measure radioactivity levels wherever you are and determine if your local environment is safe. The app can be used for the detection of radioactivity in everyday life such as exposure on airplanes, from medical patients, or from contaminated products. GammaPix™ can also be used to detect hazards resulting from unusual events like nuclear accidents (such as Fukushima), a terrorist attack by a dirty bomb, or quietly placed and potentially dangerous radioactive sources. As this technology becomes more widespread, a way to gather, process, and post the information is needed. Educating the public on its limitations is just as important as its capabilities, and Citizen Sensor website could potentially accomplish both aspects.

If Citizen Sensor had already been operational, perhaps it could have helped during the 2013 theft in Mexico of a cobalt-60 radioactive source. The thieves apparently had not been aware of what they had stolen, but what if they had been interested in making a radiological dispersal device? Just as an Amber Alert aims to help officials find a missing child or a 911 call is used for emergencies in the United States, perhaps a Citizen Sensor alert could help find missing radioactive materials.

Through the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty Organization, the world is building a surveillance network to detect nuclear tests. According to an article in the Washington Post, “the nearly-completed International Monitoring System is proving adept at tasks its inventors never imagined. The system’s scores of listening stations continuously eavesdrop on Earth itself, offering clues about man-made and natural disasters as well as a window into some of nature’s most mysterious processes.”4 What might thousands of people, educated observers, and radioactivity-detecting smart phones find?

Requirements

Citizen Sensor must be as open as possible, without any government affiliation, by hosting through a non-governmental organization. It must be unencumbered by government policy and/or regulations. It must be responsive to current events and actively maintain updated information. Knowledgeable developers of websites and training modules for nuclear fuel cycle facilities, proliferation indicators, and sustained funding are all key factors for any chance of success.

The effort must be international and multi-lingual with capabilities that evolve over time as experience and suggestions drive its future. Contributions can be either public posts or private messages and can be either anonymous or signed. It is certain there will be false positives, and issues and concerns that do not point to proliferation activity. Both the culture and software must be structured to minimize false positives and protect it and contributors from the ramifications of false positives. It will also act as a nexus for discovery tools at other websites offering maps, images, knowledge, and analysis tools.

The challenge that is faced is the support (financial and skills) to make this concept a reality. This includes recruiting scientific talent to populate educational modules, website creation and operators and methods to promote the Citizen Sensor and its potential to educate citizens about the nature of nuclear materials and proliferation.

Editor’s Note

If interested, please send feedback and ideas to citizensensor@inl.gov.

Mark Schanfein joined Idaho National Laboratory (INL) in September 2008, as their Senior Nonproliferation Advisor, after a 20-year career at Los Alamos National Laboratory where, in his last role, he served as Program Manager for Nonproliferation and Security Technology. He served as a technical expert on the ground in the DPRK during the disablement activities resulting from the 6-Party Talks. Mark has eight years of experience working at the International Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna, Austria, in the Department of Safeguards where he served four years as a safeguards inspector and as Inspection Group Leader in Operations C, and four years as the Unit Head for Unattended Monitoring Systems (UMS) in Technical Support. In this position he was responsible for the installation of all IAEA unattended systems in nuclear fuel cycle facilities worldwide.

With over 30 years of experience in international and domestic safeguards, his current focus is on conducting R&D to develop the foundation for effective international safeguards on pyroprocessing facilities and solutions to other novel safeguards challenges.

Steven Piet has worked 31 years at Idaho National Laboratory. He earned the Bachelors, Masters, and Doctor of Science degrees in nuclear engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He has 57 peer-reviewed journal articles and is author or co-author of 3 book chapters – in the fields of nuclear fuel cycles, fusion safety and technology, environmental science and decision making, and stakeholder assessment and decision making. For the nuclear fuel cycle program, he framed questions, searched for broadly acceptable and flexible solutions, promoted consensus on criteria, evaluated trade-offs, and identified R&D needs and possibilities to improve concepts; and was responsible for development of the world-leading multi-institution fuel cycle system dynamic model VISION. For the Generation IV advanced nuclear power program, his lab-university team diagnosed public/stakeholder issues and heuristics.

He has also been a Toastmaster for almost 9 years and has attained the educational achievement level of “Distinguished Toastmaster,” which less than 1% of Toastmasters achieve. As Club President, his club achieved President’s Distinguished Status. He was recognized as Area Governor of the year (2011-2012) and Division Governor of the year (2012-2013) and now serves as District Lt Governor of Marketing.

Saving Money and Saving the World

As the United States struggles to deal with budget problems, as the U.S. Air Force deals with boredom, poor morale, drug use, and cheating on certification exams by their personnel entrusted with control of nuclear missiles, we have a solution that will save money as well as make the world a much safer place – get rid of most of our nuclear weapons immediately. A recent New York Times editorial pointed out that it would cost $10,000,000,000 just to update one small portion of the U.S. arsenal, gravity bombs. The U.S. government has no data on the overall cost of maintaining its nuclear arsenal, but various sources estimate the cost over the next decade between $150 billion and $640 billion, depending largely on which nuclear related tasks are included in the budget.

A Credible Radioactive Threat to the Sochi Olympics?

With the Sochi Olympics set to start on February 6th there has been an escalating concern about security threats to the Games. There are hunts for female suicide bombers (“black widows”), video threats from militant groups, etc., all of which have triggered a massive Russian security response, including statements by President Putin insuring the safety of the Games.

Many of the security concerns are raised by the proximity of Sochi to Chechnya and relate to the threats expressed by Chechen leader Doku Umarov who exhorted Islamic militants to disrupt the Olympics.

In the past weeks the region has seen Islamic militants claims that they carried out two recent suicide bombings in Volgorad which tragically killed 34 people and injured scores of others. Volgograd is about 425 miles from Sochi and although the media stresses the proximity it is a considerable distance.

General Confirms Enhanced Targeting Capabilities of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb

By Hans M. Kristensen

The former U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff, General Norton Schwartz, confirmed last week that the B61-12 nuclear bomb planned by the Obama administration will have improved military capabilities to attack targets with greater accuracy and less radioactive fallout.

The confirmation comes two and a half years after an FAS publication first described the increased accuracy of the B61-12 and its implications for nuclear targeting in general and the deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe in particular.

The confirmation is important because the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) pledged that nuclear warhead “Life Extension Programs…will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.”

In addition to violating the NPR pledge, enhancing the nuclear capability contradicts U.S. and NATO goals of reducing the role of nuclear weapons and could undermine efforts to persuade Russia to reduce its non-strategic nuclear weapons posture.

Confirmation of the enhanced military capability of the B61-12 also complicates the political situation of the NATO allies (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey) that currently host U.S. nuclear weapons because the governments will have to explain to their parliaments and public why they would agree to increase the military capability.

Desired Military Capability

General Schwartz’s confirmation came during a conference organized by the Stimson Center in response to a question from Steven Young (video time 49:15) whether the relatively low yield and increased accuracy of the B61-12 in terms of targeting planning would change the way the military thinks about how to use the weapon.

General Schwartz made his statements during a Stimson conference last Thursday.

General Schwartz’s answer was both clear and blunt: “Without a doubt. Improved accuracy and lower yield is a desired military capability. Without a question.”

When asked whether that would result in a different target set or just make the existing weapon better, General Schwartz said: “It would have both effects.”

General Schwartz said that the B61 tail kit “has benefits from an employment standpoint that many consider stabilizing.” I later asked him what he meant by that and his reply was that critics (myself included) claim that the increased accuracy and lower yield options could make the B61-12 more attractive to use because of reduced collateral damage and radioactive fallout. But he said he believed that the opposite would be the case; that the enhanced capabilities would enhance deterrence and make use less likely because adversaries would be more convinced that the United States is willing to use nuclear weapons if necessary.

Military Implications

“Nuclear capable aircraft may have many advantages. Accuracy (as compared to other systems) is not one of them,” the Joint Staff argued in 2004 during drafting of the Doctrine for joint Nuclear Operations. Test drops of U.S. nuclear bombs normally achieve an accuracy of 110-170 meters, which is insufficient to hold underground targets at risk except with very large yield. The designated nuclear earth-penetrator (B61-11) has a 400-kiloton warhead to be effective. Therefore, increasing the accuracy of the B61 to enhance targeting and reduce collateral damage are, as General Schwartz put it at the conference, desired military capabilities.

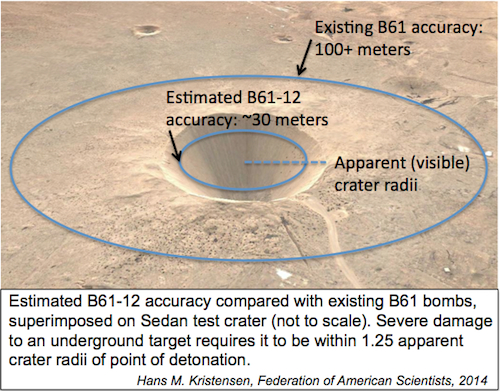

Increasing the accuracy broadens the type of targets that the B61 can be used to attack. The effect is most profound against underground targets that require ground burst and cratering to be damaged by the chock wave. Against a relatively small, heavy, well-designed, underground structure, severe damage is achieved when the target is within 1.25 the radius of the visible crater created by the nuclear detonation. Light damage is achieved at 2.5 radii. For a yield of 50 kt – the estimated maximum yield of the B61-12, the apparent crater radii vary from 30 meters (hard dry rock) to 68 meters (wet soil). Therefore an improvement in accuracy from 100-plus meter CEP (the current estimated accuracy of the B61) down to 30-plus meter CEP (assuming INS guidance for the B61-12) improves the kill probability against these targets significantly by achieving a greater likelihood of cratering the target during a bombing run. Put simply, the increased accuracy essentially puts the CEP inside the crater (see illustration below).

Cratering targets is dirty business because a nuclear detonation on or near the surface kicks up large amounts of radioactive material. With poor accuracy, strike planners would have to choose a relatively high selectable yield to have sufficient confidence that the target would be damaged. The higher the yield, the greater the radioactive fallout.

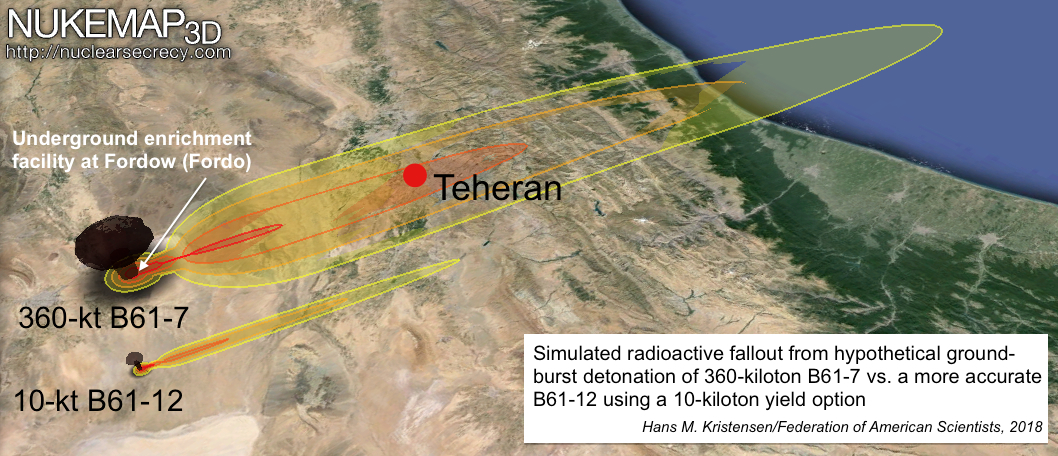

With the increased accuracy of the B61-12 the strike planners will be able to select a lower yield and still achieve the same (or even better) damage to the underground target. Using lower yields will significantly reduce collateral damage by reducing the radioactive fallout that civilians would be exposed to after an attack. The difference in fallout from a 360-kiloton B61-7 surface burst compared with a B61-12 using a 10-kiloton selective yield option is significant (see map below).

Illustrative difference in radioactive fallout from a 360-kiloton B61-7 surface burst against Iranian underground enrichment facility at Fordow, compared with using a lower-yield option of the B61-12. Fallout calculation from NUKEMAP at nuclearsecrecy.com. Click image to see larger version.

No U.S. president would find it easy to authorize use of nuclear weapon. Apart from the implications of ending nearly 70 years of non-use of nuclear weapons and the international political ramifications, anticipated collateral damage serves as an important constraint on potential use of nuclear weapons. Some analysts have argued that higher yield nuclear weapons are less suitable to deter regional adversaries and that lower yield weapons are needed in today’s security environment. The collateral damage from high-yield weapons could “self-deter” a U.S. president from authorizing an attack.

There is to my knowledge no evidence that potential adversaries are counting on being able to get away with using nuclear weapons because the United States is self-deterred. Moreover, all gravity bombs and cruise missiles currently in the U.S. nuclear arsenal have low-yield options. But poor accuracy and collateral damage have limited their potential use to military planners in some scenarios. The improved accuracy of the B61-12 appears at least partly intended to close that gap.

Implications for NATO

For NATO, the improved accuracy has particularly important implications because the B61-12 is a more effective weapon that the B61-3 and B61-4 currently deployed in Europe.

The United States has never before deployed guided nuclear bombs in Europe but with the increased accuracy of the B61-12 and combined with the future deployment of the F-35A Lightning II stealth fighter-bomber to Europe, it is clear that NATO is up for quite a nuclear facelift.

Once European allies acquire the F-35A Lightning II it will “unlock” the guided tail kit on the B61-12 bomb. The increased military capability of the guided B61-12 and stealthy F-35A will significantly enhance NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

Initially the old NATO F-16A/B and Tornado PA-200 aircraft that currently serve in the nuclear strike mission will not be able to make use of the increased accuracy of the B61-12, according to U.S. Air Force officials. The reason is that the aircraft computers are not capable of “talking to” the new digital bomb. As a result, the guided tail kit on the B61-12 for Belgian, Dutch, German, Italian and Turkish F-16s and Tornados will initially be “locked” as a “dumb” bomb. Once these countries transition to the F-35 aircraft, however, the enhanced targeting capability will become operational also in these countries.

The Dutch parliament recently approved purchase of the F-35 to replace the F-16, but a resolution adopted by the lower house stated that the F-35 could not have a capability to deliver nuclear weapons. The Dutch government recently rejected the decision saying the Netherlands cannot unilaterally withdraw from the NATO nuclear strike mission.

It is one thing to extend the existing nuclear capabilities in Europe; improving the capabilities, however, appears to go beyond the 2012 Deterrence and Defense Posture Review, which decided that “the Alliance’s nuclear posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.” It is unclear how improving the nuclear posture in Europe will help create the conditions for a world free of nuclear weapons.

It is also unclear how improving the nuclear posture in Europe fits with NATO’s arms control goal to seek reductions in Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. Instead, the increased military capabilities provided by the B61-12 and F-35 would appear to signal to Russia that it is acceptable for it to enhance its non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe as well.

Such considerations ought to be well behind us more than two decades after the end of the Cold War but continue to tie down posture planning and political signaling.

See also: B61 LEP: Increasing NATO Nuclear Capability and Precision Low-Yield Nuclear Strikes

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Radioactive Theft in Mexico: What a Thief Doesn’t Know Can Kill Him

While the theft of a truck carrying radioactive cobalt made international headlines, this was unfortunately not the first time thieves or scavengers have exposed themselves or others to lethal radiation. Probably the most infamous case was on September 13, 1987 in Goiania, Brazil. Scavengers broke into an abandoned medical clinic and stole a disused teletherapy machine. These machines are used to treat cancer by irradiating tumors with gamma radiation typically emitted by either cobalt-60 or cesium-137. In the Goiania case, the gamma-emitting radioisotope was cesium-137 in the chemical form of cesium chloride, which is a salt-like substance. When the scavengers broke open the protective seal of the radioactive source, they saw a blue glowing powder: cesium chloride. This material did not require a “dirty bomb” to disperse it. Because of the easily dispersible salt-like nature of the substance, it spread throughout blocks of the city and contaminated about 250 people. Four people died form radiation sickness by ingesting just milligrams of the substance.

The effects could have been worse, but an extensive cleanup effort, costing tens of millions of dollars, captured about 1200 Curies of the estimated 1350 Curies of radioactivity in the disused teletherapy source. To put this Curie content in perspective, a source with 100 or more Curies of gamma-emitting radioactive material would be considered a source of security concern. The International Atomic Energy Agency has published an authoritative account of the Goiania event.