Nuclear Policy and strategy, De-alerting,

Nuclear Weapons

By Hans M. Kristensen

The full unclassified New START treaty data set released by State Department yesterday shows that the US reduction of its nuclear forces to meet the treaty limit had been completed by September 1, 2017, more than four months early before the deadline next month on February 5, 2018.

The data set reveals details about how the final reduction was achieved (see below).

Unfortunately, no official detailed data is released about the Russian force adjustments under New START. Our previous analysis of the overall September 1, 2017 New START data is available here.

Submarines

During that six-month period last year, 20 ballistic missile submarine launch tubes were deactivated, corresponding to four tubes on five Ohio-class submarines. Two of those submarines were in drydock for refueling and not part of the operational force.

In total, the United States has deactivated 56 strategic missile submarine launch tubes since the New START treaty went into effect in 2011, although the first reduction didn’t begin until after September 2016 – more than five years into the treaty.

The USS Louisiana (SSBN-743) returns to Kitsap Submarine Base in Washington on October 15, 2017 after a deterrent patrol in the Pacific Ocean. The submarine carried 20 Trident II missiles with an estimated 90 nuclear warheads.

Of the 280 submarine launch tubes, only 212 were counted as deployed with as many Trident II missiles loaded. The treaty counts a missile as deployed if it is in a launch tube regardless of whether the submarine is deployed at sea. The United States has declared that it will not deploy more than 240 missiles at any time. Assuming each deployed submarine carries a full missile load, the 212 deployed missiles correspond to 10 submarines fully loaded with a total of 200 missiles. The remaining 12 deployed missiles were onboard one or two submarines loading or offloading missiles at the time the count was made.

The data shows that the 212 deployed missiles carried a total of 945 warheads, or an average of 4 to 5 warheads per missile, corresponding to 70 percent of the 1,344 deployed warheads as of September 1, 2017 (the New START count was 1,393 deployed warheads, but 49 bombers counted as 49 weapons don’t actually carry warheads, leaving 1,344 actual warheads deployed). If fully loaded, the 240 deployable SLBMs could carry nearly 2,000 warheads.

The Navy has begun replacing the original Trident II D5 missile with an upgraded version known as Trident II D5LE (LE for life-extension). The upgraded version carries the new Mk6 guidance system and the enhanced W76-1/Mk4A warhead (or the high-yield W88-0/Mk5). In the near future, according to the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), some of the missiles would be equipped with a low-yield version of the W76-1.

The Navy is developing a new fleet of 12 Columbia-class missile submarines to begin replacing the Ohio-class SSBNs in the late-2020s. The Trump NPR states that “at least” 12 will be built. Each Columbia-class SSBN, the first of which will deploy on deterrent patrol in 2031, will have 16 missile tubes for a total of 192, a reduction of one-third from the current number of SSBN tubes. Ten deployable boats will be able to carry 160 Trident II D5LE missiles with a maximum capacity of 1,280 warheads; normally they will likely carry about the same number of warheads as the current force, with an average of about 5 to 6 warheads per missile.

ICBMs

The New START data shows the United States now has just under 400 Minuteman III ICBMs in silos, down from 405 in March 2017. Normally the Air Force strides to have 400 deployed but one missile was undergoing maintenance.

A Minuteman III ICBM is removed from its silo at F.E. Warren AFB on June 2, 2017, the last to be offloaded to bring the United States into compliance with the New START treaty limits.

Although the number of deployed ICBMs had declined from 450 to 400, the total numbers of missiles and silos have not. The data shows the Air Force has the same number of missiles and silos as in March 2017 because 50 empty silos are “kept warm” and ready to load 50 non-deployed missiles if necessary. Reduction of deployed ICBMs started in 2016, five years after the New START was signed. And the actual ICBM force is the same size as when the treaty was signed.

The 399 deployed ICBMs carried 399 W78/Mk12A or W87/Mk21 warheads. Although normally loaded with only one warhead each, the Trump NPR confirms that “a portion of the ICBM force can be uploaded” if necessary. We estimate the ICBM force has the capacity to carry a maximum of 800 warheads.

An ICBM replacement program is underway to build a new ICBM (programmatically called Ground Based Strategic Deterrent) to begin replacing the Minuteman III from 2029. The new ICBM will have enhanced penetration and warhead fuzing capabilities.

Heavy Bombers

The New START data shows the US Air Force has completed the denuclearization of excess nuclear bombers to 66 aircraft. This includes 20 B-2A stealth bombers for gravity bombs and 46 B-52H bombers for cruise missiles. Only 49 of the 66 bombers were counted as deployed as of September 1, 2017. Another 41 B-52Hs have been converted to non-nuclear armament such as the conventional long-range JASSM-ER cruise missile.

The New START treaty counts each of the 66 bombers as one weapon even though each B-2A can carry up to 16 bombs and each B-52H can carry up to 20 cruise missiles. We estimate there are nearly 1,000 bombs and cruise missiles available for the bombers, of which about 300 are deployed at two of the three bomber bases.

The first B-52H bomber was denuclearized under New START in September 2015. Denuclearization of excess nuclear bombers was completed in early 2017.

The bomber force was the first leg of the Triad to begin reductions under New START, starting with denuclearization of the (non-operational) B-52Gs and later excess B-52Hs. The first B-52H war denuclearized in September 2015 and the last of 41 in early 2017. Despite the denuclearization of excess aircraft, however, the actual number of bombers assigned nuclear strike missions under the strategic war plans is about the same today as in 2011.

A new heavy bomber known as the B-21 Raider is under development and planned to begin replacing nuclear and conventional bombers in the mid-2020s. The B-21 will be capable of carrying both the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb and the new LRSO nuclear cruise missile. The Air Force wants at least 100 B-21s but can only make 66 nuclear-capable unless it plans to exceed the size of the current nuclear bomber force.

Looking Ahead

With the completion of the force reductions under New START in preparation for the treaty entering into effect on February 5, 2018, the attention now shifts to what Russia and the United States will do to extend the treaty or replace it with a follow-up treaty. With its on-site inspections and ceilings on deployed and non-deployed strategic forces, extending New START treaty for another five years ought to be a no-brainer for the two countries; anything else would increase risks to strategic stability and international security. If the treaty is allowed to expire in 2021, there will be no – none! – limits on the number of strategic nuclear forces. Unfortunately, right now neither side appears to be doing anything except to blame the other side for creating problems. It is time for Russia and the United States to get out of the sandbox and behave like responsible states by agreeing to extend the New START treaty. February 5 – when the treaty enters into effect just 23 days from now – would be a great occasion for the two countries to announce their decision to extend the treaty.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Updated: 2/6/2018, 15:32

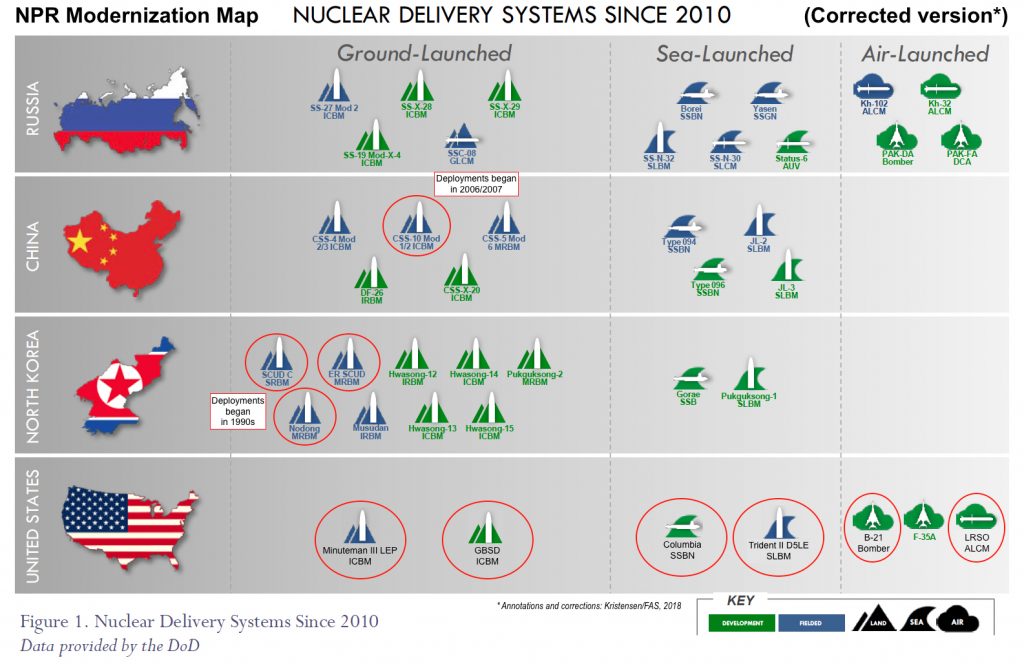

The Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) is the Pentagon’s primary statement of nuclear policy, produced by the last three presidents in their first years in office.

The Trump NPR perceives a rapidly deteriorating threat environment in which potential nuclear-armed adversaries are increasing their reliance on nuclear weapons and follows suit. The review reverses decades of bipartisan policy and orders what would be the first new nuclear weapons since the end of the Cold War. Furthermore, the document expands the use of circumstances in which the United States would consider employing nuclear weapons to include “non-nuclear strategic attacks.”

You can view the first version of the document here.

You can also view the leaked draft document here.

The 2018 NPR says US nuclear forces “contribute uniquely to the deterrence of both nuclear and non-nuclear aggression” (208). Conventional forces, it states, “do not provide comparable deterrence effects,” and “do not adequately assure many allies,” (851), many of whom rely on US conventional deployments for their security. In addition, the document states they contribute to assuring allies, achieving US objectives if deterrence fails, and hedging “against an uncertain future” (981). The review also raises the possibility of a nuclear strike against any group that “supports or enables terrorist efforts to obtain or employ nuclear devices,” extending previous language (2051).

The review also creates a new category of cases in which the United States would consider use of nuclear weapons—“significant non-nuclear strategic attacks,” to include attacks on “civilian population or infrastructure” (917, 1026). This new category helps serve as justification for “supplements to the planned nuclear force replacement program” (1751).

Overall, the NPR argues that a range of Russian and Chinese activities have caused the international threat environment to worsen (636), but it does not fully explain why these activities require increased reliance on nuclear weapons. It states that other nuclear-armed adversaries have failed to follow America’s lead in reducing reliance on nuclear weapons (678). In this, it claims that Russia plans for “limited nuclear first use” to prevail in limited conflict (694), though there is thin evidence that this is Russian doctrine. The document concedes that China has not altered its doctrine, while North Korea’s capabilities are so rudimentary that “increased reliance” has little meaning.

The United States is engaged in a 30 year effort to refurbish or replace nearly every warhead and delivery vehicle in air, sea, and land legs of the nuclear triad. The modernization program (formally known as the Program of Record) was initiated by the Obama administration and the Trump NPR has pledged to continue this effort. Despite calls from some external sources, the 2018 review makes no reductions in Obama’s modernization plan. Instead, the NPR calls for new nuclear SLCM and a low-yield SLBM warhead. The NPR also seems to call for retention of the 1.2 megaton B83 nuclear bomb (which had been slated for retirement once the B61-12 enters service) with contradictory statements for when the warhead may be retired (462 & 1900 vs. 325 & 1529) and what the replacement might be.

The NPR promises to “in the longer term, pursue a modern nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM) which “will provide a needed non-strategic regional presence, an assured response capability, and an INF-Treaty compliant response to Russia’s continuing Treaty violation” (395, 1729). The document also hopes that the program will help convince Russia to “negotiate seriously a reduction of its non-strategic nuclear weapons,” and return to compliance with the INF Treaty. Critical experts believe that a new SLCM would inhibit US forces from carrying out their conventional missions, add little new capability, and would be more likely to cause Russian reprisal than compliance.

The NPR calls for modifying “a small number of existing SLBM warheads to provide a low-yield option” (1715) that “will help counter any mistaken perception of an exploitable ‘gap’ in U.S. regional deterrence capabilities” (1724). It is a policy directly contrary to the Obama NPR’s affirmation that warhead development “will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities;” there currently are no low-yield SLBM warheads in the arsenal. The Trump NPR argues that this new capability would provide the option to rapidly strike a target with a lower nuclear yield than current options, hoping to communicate limited intentions or limit collateral damage. The new capability would blur the distinction between strategic and non-strategic weapons by what appears to be a sub-strategic SLBM mission. Launch of a low-yield SLBM would expose the submarine and its other warheads to retaliation and there is no guarantee that an adversary would understand the strike was limited, whether while in the air or once detonated.

The NPR document calls the nuclear mission “an affordable priority,” (1647) noting that “even the highest” of cost projections is “approximately 6.4 percent of the current DoD budget” (1660). Yet, Obama administration officials, military leaders, and federal research agencies have all warned that there is currently no plan to pay what CBO had estimated as the $1.2 trillion cost of operating the arsenal over the next thirty years. If Congress appropriates additional funds to meet the NPR’s requirements (and if there are cost overruns in the acquisition programs), this figure will increase.

Overall, the NPR seems to deemphasize and downplay the prospects for strategic arms control. The document says that the United States “remains willing to engage in a prudent arms control agenda,” (556) adds a new qualification for arms control agreements—that they be “verifiable and enforceable” (514, 540). This standard may prohibit agreements like President George H. W. Bush’s 1991 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives, which were largely voluntary. Furthermore, it is not clear whether any international agreement can be “enforceable.” Additionally, the document also states that the government “does not support ratification” of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which could allow the government to pursue activities incommensurate with the spirit of the treaty.

Status of World Nuclear Forces (with R. Norris)

FAS Nuclear Notebook series (with R. Norris), Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

New Data Shows Detail About Final Phase of US New START Treaty Reductions FAS Strategic Security Blog, 1/2018

NNSA’s New Nuclear Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan FAS Strategic Security Blog, 11/2017

The Flawed Push For New Nuclear Weapons Capabilities FAS Strategic Security Blog, 6/2017

Trump’s Troubling Nuclear Plan Foreign Affairs, 2/2018

Letting It Be An Arms Race The Atlantic, 1/2018

The Case Against New Nuclear Weapons, Center for American Progress, 5/2017

Adapting Nuclear Modernization to the New Administration, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2017

Setting Priorities for Nuclear Modernization (with L. Korb), Center for American Progress, 2/2016

NPR chart earns three Pinocchios for misleading public: “A Pentagon chart misleadingly suggests the U.S. is falling behind in a nuclear arms race,” Washington Post, 2/12/2018

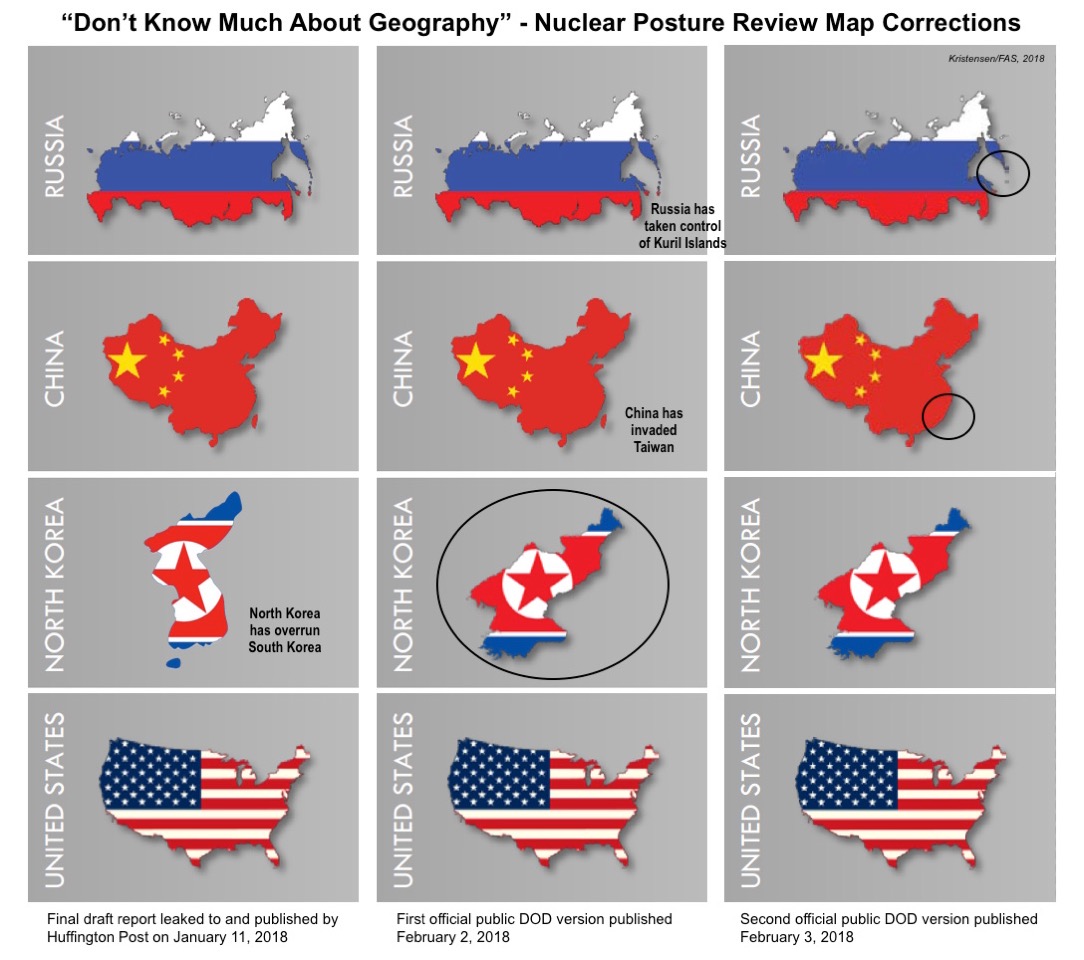

Geography graphics across the three versions of the Nuclear Posture Review (draft, official version, and updated version) with corrections and clarifications. (Hans Kristensen/FAS)

Anna Péczeli, “Continuity and change in the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2/20/2018

John R. Harvey, et al., “Continuity and Change in U.S. Nuclear Policy,” Real Clear Defense, 2/7/2018

Steven Pifer, “Questions about the Nuclear Posture Review, Brookings, 2/5/2018

Matthew Harries, “A nervous Nuclear Posture Review,” IISS, 2/5/2018

Rebecca Hersman, “Nuclear Posture Review: The More Things Change, The More They Stay the Same,” Defense Outlook 2018 (CSIS), 2/2018

James Acton (CEIP), “Command and Control in the Nuclear Posture Review: Right Problem, Wrong Solution,” War on the Rocks, 2/5/2018

Andy Weber, “Trump Call for New Nukes Will Make America Less Safe,” The Cipher Brief, 2/4/2018

The Washington Post editorial, “Trump’s request for even more nuclear weapons is flawed overkill,” 2/3/2018

Alicia Sanders-Zakre (Arms Control Association), “Why we should reject Trump’s dangerous nuclear plan,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2/2/2018

Tom Z. Collina (Ploughshares), “Give Trump more nuclear weapons and more ways to use them? Not a good idea,” CNN, 2/2/2018

Rachel Bronson, Sharon Squassoni, Hans M. Kristensen, and Alicia Sanders-Zakre, “The experts on the Nuclear Posture Review,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2/2/2018

Anne Armstrong and Cassandra Varanka, “Taking on Trump’s Dangerous Nuclear Posture Review,” Ms. Magazine blog, 2/2/2018

Jon Wolfsthal (Global Zero), “US Approach to Russia in New Nuclear Posture Review Risks Boosting Chances of Conflict,” Russia Matters, 2/2/2018

Joe Cirincione (Ploughshares), “Nuclear Nuts: Trump’s New Policy Hypes The Threat and Brings Us Closer to War,” Defense One, 2/2/2018

Michaela Dodge (Heritage), “5 Myths About the Nuclear Posture Review,” Daily Signal, 2/2/2018

Mark Perry, “Trump’s Nuke Plan Raising Alarm Among Military Brass,” The American Conservative, 2/2/2018

William J. Hennigan, “Donald Trump Is Playing a Dangerous Game of Nuclear Poker,” Time Magazine, 1/1/2018

Paul Bracken (Yale), “The 2018 Nuclear Posture Review: Signaling Restraint with Stipulations,” FPRI, 2/1/2018

16 US Senators, Letter to the President on the NPR, 1/29, 2018

Rep. Adam Smith, “Smith Statement on the Nuclear Posture Review,” House Armed Services Committee Democrats, 1/24/2018

Lisbeth Gronlund and Stephen Young, “The U.S.’s Dangerous New Nuclear Policy,” Aviation Week, 1/26/2018

Michaela Dodge (Heritage), “Trump’s Nuclear Posture Review Must Keep us Safe,” National Review, 1/22/2018

Andy C. Weber (Harvard), “Trump Wants New Nukes. We Can’t Let Him Have Them,” Huffington Post, 1/19/2018

Michèle Flournoy, Interview with WNYC, 1/18/2018

Michael Krepon (Stimson), “The Most Dangerous Word in the Draft Nuclear Posture Review,” Defense One, 1/23/2018

Fred Kaplan, “Nuclear Posturing: Trump’s official nuclear policy isn’t that different from his predecessors.‘ That’s what makes it so scary,” Slate, 1/22/2018

Vince Manzo (CNA), “Give the Low -Yield SLBM its Day in Court,” Defense One, 1/22/2018

Joan Rohlfing, Jon Wolfsthal, Thomas Countryman, Arms Control Association briefing, Press Briefing with Experts on the Trump Nuclear Posture Review, 1/23/2018

George Perkovich (CEIP), “Really? We’re Gonna Nuke Russia for a Cyberattack?,” Politico, 1/2018

Loren Thompson (Lexington), “Trump’s Nuclear Strategy Is Basically The Same As Obama’s,” Forbes, 1/2018

Jon Wolfsthal and Richard Burt (Global Zero), “America and Russia May Find Themselves in a Nuclear Arms Race Once Again,” The National Interest, 1/2018

Tom Z Collina (Ploughshares Fund), “Give Trump new nukes and we are that much closer to war,” The Hill, 1/2018

The New York Times Editorial Board, “False Alarm Adds to Real Alarm About Trump’s Nuclear Risk,” 1/13/2018

Daryl G. Kimball, (Arms Control Association), “Trump’s More Dangerous Nuclear Posture,” Arms Control Today, 1/2018

Jon Wolfsthal (Global Zero), “Say No To New, Smaller Nuclear Weapons,” War on the Rocks, 11/2017

Brad Roberts (LLNL), “Strategic Stability Under Obama and Trump,” Survival, 7/2017

Jon Wolfsthal (Global Zero), “How Will Trump Change Nuclear Weapons Policy?” Arms Control Today, 11/2017

Robert Einhorn and Steven Pifer (Brookings), “Meeting U.S. Deterrence Requirements,” Brookings, 9/2017

The third Nuclear Posture Review set out from the start to produce an comprehensive public document. In this way, the review served several purposes: it provided an opportunity to interpret President Obama’s Prague commitment to seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons, to explain the strategic benefits of the New START treaty and to establish the force structure to comply with it, and served as a prominent and public way of communicating with allies and adversaries. The central compact was that as long as nuclear weapons exist, the United States will maintain a safe, secure, and effective deterrent. In this way, the NPR could endorse modernization and sustainment investments while reducing the role and number of nuclear weapons. Though relatively modest in terms of force structure changes, the document’s main innovation was to declare that the United States will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against nonnuclear weapons states that are party to and remain in compliance with their obligations under the Nonproliferation Treaty.

The second NPR was marked by inventive concepts and poor public relations. The intention was to produce a classified document that would be briefed publicly. In open testimony, Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Doug Feith described the NPR as an attempt rethink deterrence for a world where Russia was no longer an enemy. The nation’s strategic posture would no longer depend on Mutual Assured Destruction, but one Feith said would have “the flexibility to tailor military capabilities to a wide spectrum of contingencies.” Operational concepts would rely more on prompt conventional strike and defensive capabilities. To enhance flexibility, the NPR seemed to endorse development of new earth-penetrating warheads and also required a responsive infrastructure that could quickly produce and test new capabilities if a threat arose. Moving away from MAD allowed for a reduction of deployed warheads below 2,200, but the NPR mandated no further modifications to force structure. Three months after the initial briefing, selections of the classified report leaked to the media and were widely criticized by arms control groups and foreign officials. Fairly or unfairly, many read the leaked sections as blurring the line between nuclear and conventional weapons and refusing to accept mutual vulnerability. Administration officials scrambled to clarify but never fully dispelled concerns, leaving more questions than answers.

President Clinton ordered the first NPR to examine the role of nuclear weapons after the end of the Cold War. A five-person steering group led six working groups. The established process broke down in the summer of 1994 over tensions the steering group and the military stakeholders. In the end, the review failed to generate a unitary document; its results were briefed to the press and to Congress. The 1994 NPR established a force structure to comply with the START II Treaty and ordered cuts to each leg of the triad: conversion of four Ohio-class submarines and all B-1 bombers to conventional missions, reduction in B-52 and Minuteman III inventories, and elimination of Minuteman II and Peacekeeper ICBMs. Secretary of Defense Bill Perry summarized the NPR as an attempt to provide leadership for further reductions while hedging against the emergence of threats.

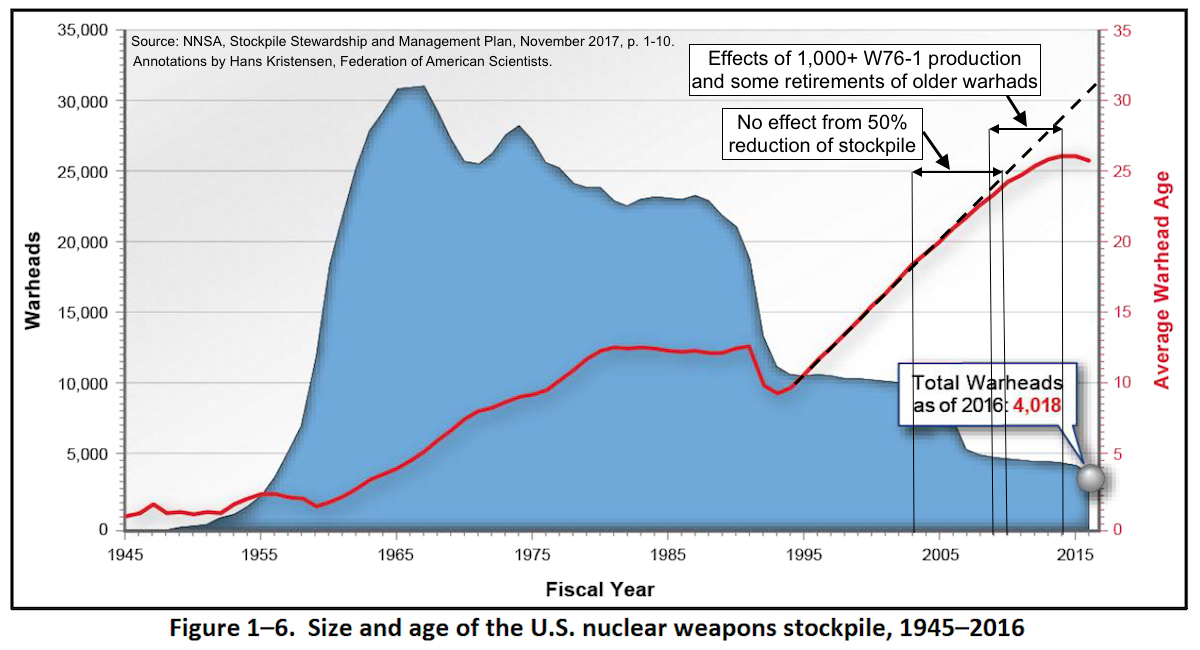

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has published its long-awaited Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) for Fiscal Year 2018. The SSMP is NNSA’s 25-year strategic program of record.

I’ll leave it to others to analyze the infrastructure and fissile material portions and focus on the nuclear weapons life-extension programs (LEPs) and cost estimates.

This year’s plan shows complex LEPs that are making progress but also getting more expensive (some even with funding gaps). There are some surprises (the retirement of the B61-10 tactical bomb), some sloppiness (the stockpile table has not been updated), and some questionable depictions (how to cut stockpile in half with no effect on average warhead age).

Nonetheless, the SSMP is a unique and important document and a service to the public discussion about the scope and management of the nuclear weapons arsenal and infrastructure. NNSA deserves credit for producing and publishing the SSMP. As such, it is a reminder that other nuclear-armed states should also publish factual overviews of their nuclear weapons programs to enable fact-based discussions and counter unsubstantiated rumors and worst-case suspicion.

Nuclear Nuts and Bolts

The 2017 SSMP does not update the nuclear stockpile number but continues to use the 4,018-warhead number (as of September 2016) declassified by the Obama administration in January 2017. The Trump administration has yet to declassify any nuclear stockpile numbers. The number now is estimated at around 4,000.

The report includes a graph that shows the average warhead age in the stockpile over the years. The graph shows the age continued to increase until about 2009, at which point it slowed until leveling out in 2014, presumably because of the significant production of W76-1 warheads (an LEP resets the warhead age to zero). In 2016, the average age began to drop, presumably because of the Obama administration’s 500-warhead cut in 2016 and continued production of the W76-1.

NNSA’s average warhead graph shows no effect from W Bush administration’s massive nuclear stockpile reduction. Click to view full size.

The near-continuous age increase through 2003-2007 is curious, however, because it shows hardly any visible effect from the massive stockpile reduction that occurred in those years. Why did a 50-percent reduction of the stockpile in 2003-2007 not have any effect on the average age of the remaining stockpiled warheads, when a 12-percent reduction in 2016 did? (The reductions in 1992-1994 also had a clear effect on the average warhead age.)

For that to be true, NNSA would have had to retire precisely the same portion of newer and older warheads of each warhead type, which seems odd.

The report reveals that the B61-10 tactical bomb was quietly retired in September 2016. The B61-10 has been in the inactive stockpile since 2006. The retirement is a surprise because the B61-10 is one of four B61 versions NNSA has listed to be consolidated into the B61-12. Once the B61-12 was produced and certified, so the argument was, the older versions would be retired.

The 2017 SSMP reveals that the B61-10 tactical bombs has been retired but continues to list the weapon as part of the B61-12 “consolidation” plan.

Despite the B61-10 retirement, officials have continued to include the weapon in the “consolidation” justification for the B61-12 during congressional hearings in 2017. In fact, the 2017 SSMP itself continues to include the B61-10 in its description of the B61-12 programs: “will consolidate four versions of the B61 into a single variant.”

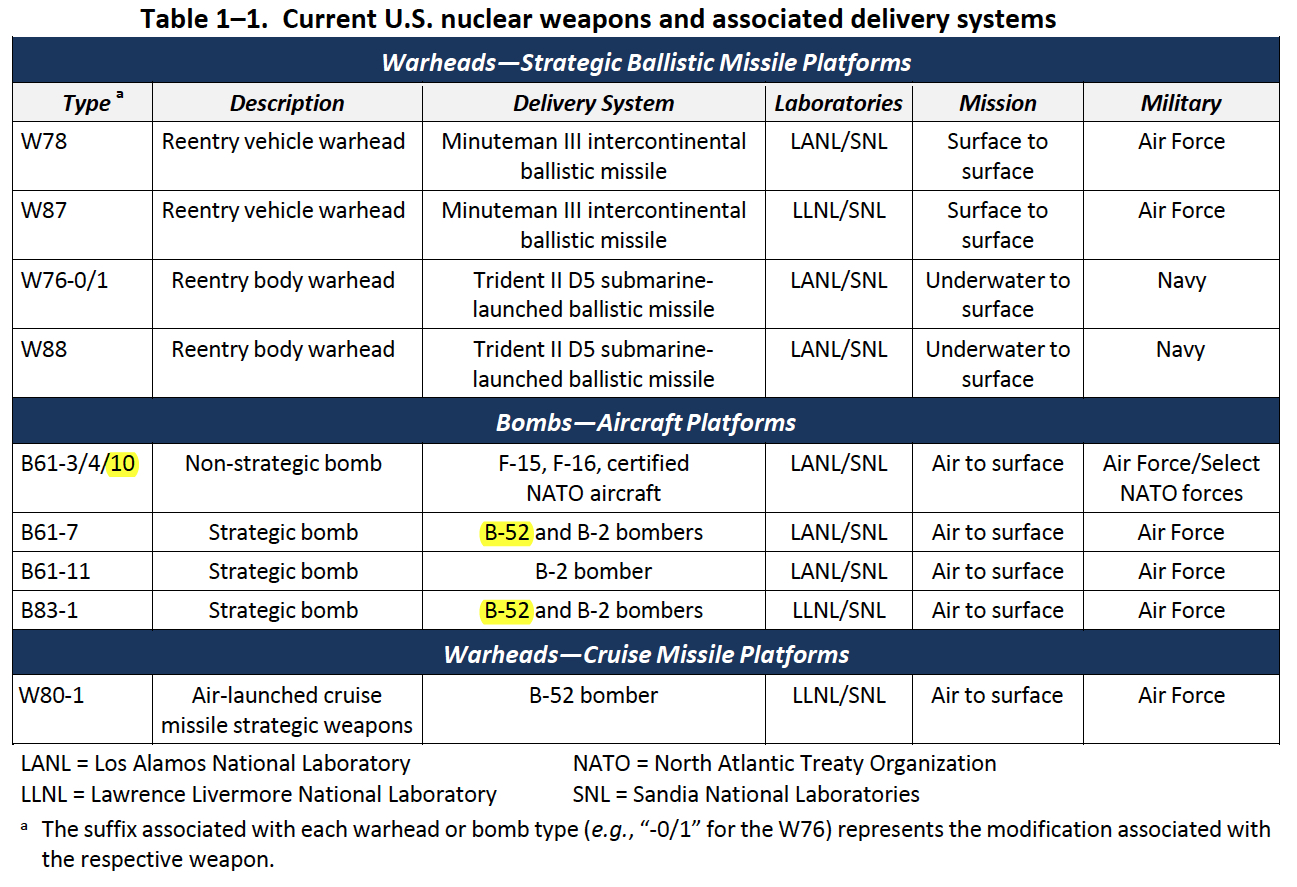

Despite the B61-10 retirement, the SSMP’s main table of the current nuclear weapons and associated delivery vehicles still lists the bomb (another table in the report does not list the B61-10).

The SSMP report’s main table for the arsenal lists the B61-10 even though it has been retired, and gravity bombs for the B-52H even though it no longer caries them.

That table also lists the B-52H as carrying gravity bombs, even though other government documents no longer list gravity bombs assigned to the bomber. The authors appear to have done a sloppy job and simply copied the table from the 2016 SSMP without updating it.

The 2017 SSMP breaks down the extensive nuclear weapons modernization plan:

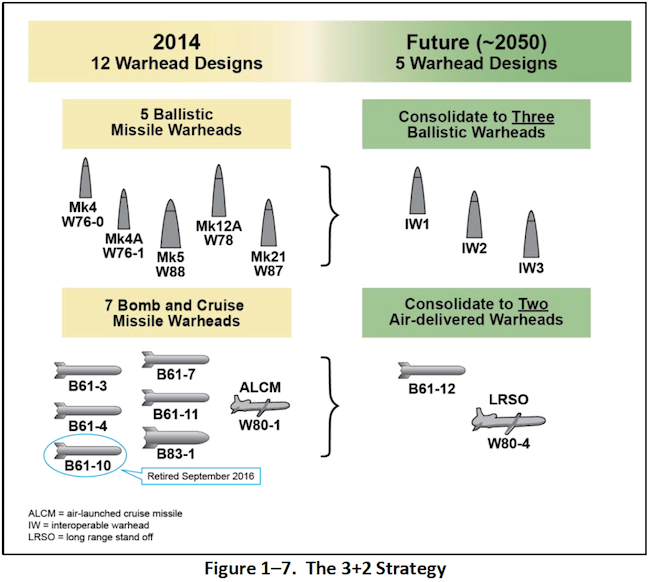

The 2017 SSMP also reaffirms the commitment to the “3+2” warhead strategy (which actually is a 6+2 strategy) even though the program is too expensive and potentially threatens the US nuclear testing moratorium. The “3” are so-called “interoperable warheads” intended for deployment on the ICBMs and SLBMs. The SSMP describes the Nuclear Weapons Council’s definition of an IW as “an interoperable NEP [Nuclear Explosive Package], with adaptable non-nuclear components on SLBMs and ICBMs.”

But even though “[f]inal designs of NEPs for the IW1, IW2, and IW3 warheads are yet to be determined,” the SSMP nonetheless confidently declares that the “3+2 Strategy preserves confidence in the stockpile’s operational reliability and effectiveness, while mitigating risk and uncertainty.” IW1 production is not expected until 2031, and I bet there are a couple of more design evaluations and decisions before NNSA can make any realistic assessment about reliability and effectiveness.

Moreover, I hear a lot of grumbling in the Navy and Air Force with concerns about introducing significantly modified warhead designs when the existing versions work just fine. Indeed, because the IW designs have not been tested in the assembled configuration envisioned, the 3+2 plan could introduce new uncertainties into the stockpile about warhead reliability and performance.

The Nuclear Posture Review is considering modifying a SLBM warhead to primary-only configuration to enable rapid low-yield strikes with ballistic missiles.

And The Money?

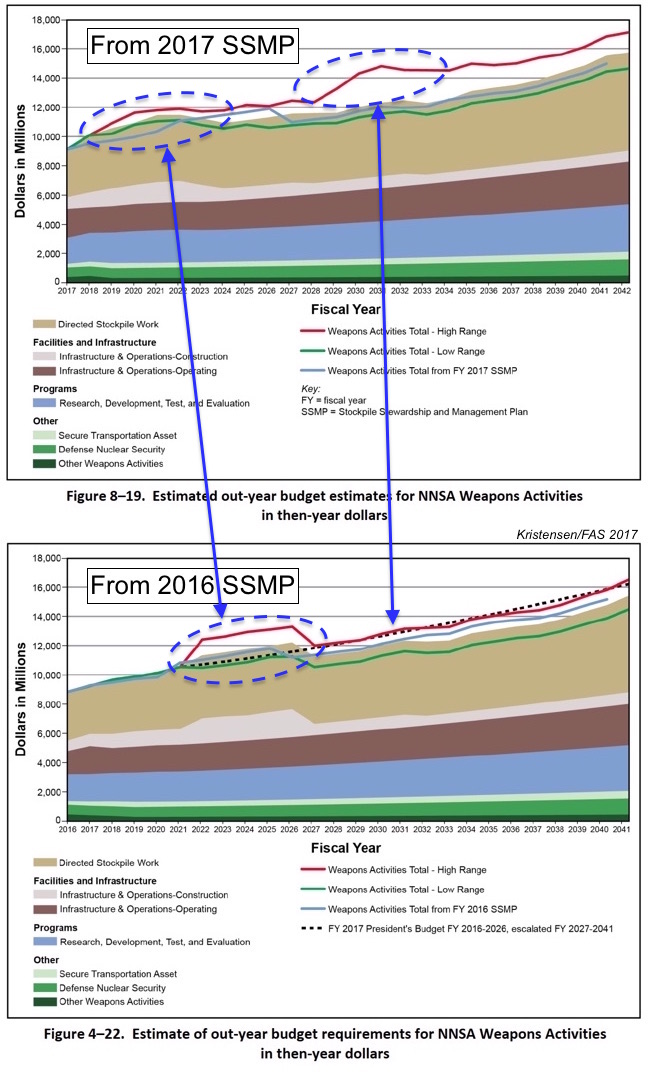

NNSA’s nuclear weapons budget has increased by 60 percent since 2010, and the agency is hoping for another $1 billion increase in 2018. In anticipation of the new NPR, the 2017 SSMP does not include budget numbers for 2019-2022 (the 2016 SSMP included these out-year numbers). And the detailed cost graph cuts off after 2018, unlike the 2016 SSMP graph that continued through 2021. But NNSA provides a new graph that plots expected weapons activities costs through 2042; there are significant changes compared with the graph included in the 2016 SSMP.

NNSA has restructure LEP spending plan so it moves “bow wave” up earlier, creates new bow wave later, and increases overall long-term costs.

It will take more time to analyze the data but a first impression is that NNSA has reorganized the projected costs so that the bow wave shown in the 2016 SSMP to appear in the 2020s now has been spread out and moved up so that it begins almost immediately and ends in the mid-2020s. Moreover, the graph shows a new high-range estimate cost emerging in the late-2020s and with significantly higher projections through 2042.

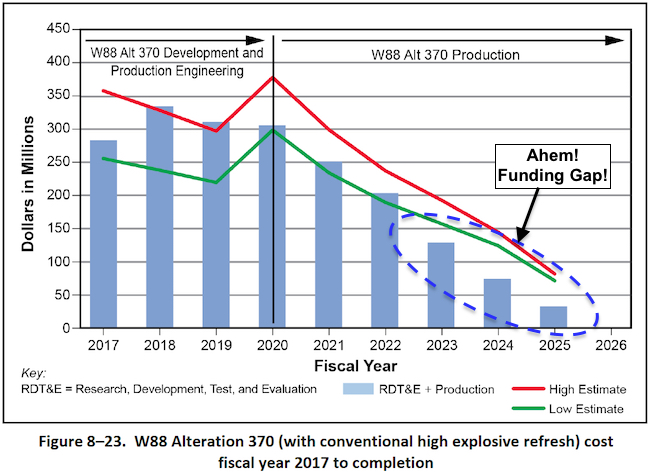

As part of that projection, all of NNSA’s LEPs high-end cost estimates appear to have increased, and there are still funding gaps toward the end of some of the programs, a budgeting problem that has previously been pointed out by GAO.

Some LEP programs appear to have insufficient funding.

And if you think the $10 billion B61-12 program is expensive, just check out the high-end cost estimate for the next B61 LEP (known as B61-13): a whopping $13.7 billion to $26.3 billion. Combined, in NNSA’s illustration, all the LEPs add up to $1.4 billion in 2017, increasing to nearly $2 billion per year in 2021-2037, and then ballooning to more than $2.8 billion per year by 2041.

Production Infrastructure

The 2017 SSMP also includes some interesting information about the production complex capacity, not least the planned production of plutonium pits at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Production is scheduled to increase from four pits in 2018 to 10 in 2024, 20 in 2025, 30 in 2026, and build capacity to produce 50-80 pits per year by 2030.

Later in the SSMP (p. A-10), it turns out the requirement for the 10, 20, and 30 pits in 2024, 2025, and 2026, respectively, actually is to produce “not less than” those numbers. And the requirement for 2030 is no less than 80 pits.

All of this of course hinges on if and how NNSA can complete the construction of the expensive production facilities needed.

Testing

The 2017 SSMP concludes that “there is no current requirement to conduct an underground nuclear test to maintain certification of any nuclear warhead.” That is good news. The 1993 Presidential Decision Directive (PDD-15, “Stockpile Stewardship”) directed NNSA to maintain the capability to conduct a nuclear test within 24 to 36 months, just in case a test was needed in the future.

But the 2017 SSMP states that NNSA has changed its assessment of what that guidance means and says “the fundamental approach taken to achieve test readiness has also changed.” Unlike the 2016 SSMP, the 2017 SSMP introduces a much shorter readiness timeline for a simple test:

This reassessment of the test readiness requirement appears to erode the US commitment to the testing moratorium. And it implies that NNSA is anticipating that future and more complex LEPs might potentially require “a simple test” with a nuclear yield. Such a test would be devastating to the international security environment and trigger a wave of nuclear tests in other nuclear-armed states.

For now, warhead development and surveillance rely on subcritical hydrodynamic tests, which are gradually becoming more complex and using more fissile material. The 2017 SSMP describes work is underway to develop an operational “enhanced capability” for subcritical experiments by the mid 2020s.

There were seven “integrated hydrodynamic experiments” conducted in 2016, including for what the SSMP describes as “stockpile options.” These options appear to be different from the known LEPs and stockpile maintenance efforts.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This is not even a Trump SSMP. The document describes the program of record: the maintenance and modernization plan initiated by the Obama administration. Yet in setting the policy framework for the 2017 SSMP, NNSA invokes president Trump’s January 2017 memorandum (NSPM-1) on rebuilding the armed forces to conduct a “new Nuclear Posture Review to ensure that the U.S. nuclear deterrent is modern, robust, flexible, resilient, ready, and appropriately tailored to deter 21st-century threats and reassure our allies.”

This formulation is different and much broader than the requirement listed in the 2016 SSMP, which required NNSA to “maintaining the safety, security, and effectiveness of the nuclear stockpile.”

From NSPM-1, the 2017 SSMP highlight an overall intension “to pursue peace through strength” and “give the President and the Secretary [of Defense] maximum strategic flexibility.”

“Maximum” is a dangerous requirement because it can be used to justify pursuit of all sorts of enhancements for the sake of improved capability. “Sufficient” is a much better word because it forces planners to think about how much is enough and balance this against other realities and requirements.

The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review expected at the turn of the year will mainly be focused on implementing the main elements of the Obama administration’s nuclear modernization program, but it is also considering new weapons and modified warheads.

And the tone describing the international environment will certainly darken. In describing the strategic context, the 2017 SSMP unfortunately makes the usual mistake of lumping Russia in among the countries that are “expanding” their nuclear arsenals. In terms of the total number of launchers and warheads, that is not the case.

NNSA’s nuclear warhead modernization plan forms part of a boarder nuclear modernization plan that is unaffordable as currently designed. The Congressional Budget Office recently presented options for how to reduce the costs. Several of those options include scaling back or canceling warhead programs, options that NNSA should actively consider.

Modifying requirements and scaling back ambitions can have considerable effects on what the Nation gets in return for its investments. Consider for example that the complex $10 billion B61-12 LEP only adds 20 years of life for 480 warheads, while the simpler $4 billion W76-1 LEP adds 30 years of life for 1,600 warheads.

The early retirement of the B61-10, moreover, raises obvious questions about why some of the other “consolidation” versions (B61-3, -4, and -7) cannot also be retired early. Moreover, many B83s currently maintained in the stockpile could probably be retired early as well and dismantled.

On dismantlement, the 2017 SSMP is a clear step back. The requirement in the 2016 SSMP to accelerate dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 has been deleted from the 2017 update. And while funding for dismantlement in the 2016 SSMP was increased to two percent of the directed stockpile budget, the 2017 report reduces the budget for warhead dismantlement and disposition to only one percent. Completion of dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 is scheduled for September 2022 – one year later than the deadline listed in the 2016 SSMP. But the 2017 SSMP doesn’t even address what the plan is for dismantling the backlog of the roughly 1,000 warheads that have been retired after 2009.

While dismantlement is not a priority for NNSA or defense planners who are focused on modernization, it is an important and powerful message to the international community that the United States is not only modernizing but actually also scrapping nuclear weapons. After all, with no new arms control treaty to replace New START (not even negotiations), an INF treaty that is close to collapsing, rejection of the Ban Treaty, and rampant modernization programs underway to extend the nuclear era through the rest of this century, what else do we (and the other P5s) have to show at the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty review conference in 2020?

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The President’s authority to use nuclear weapons — which is the subject of a congressional hearing today before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee — was addressed in several recent publications of the Congressional Research Service.

A new CRS Legal Sidebar addresses the unresolved question: Can Congress Limit the President’s Power to Launch Nuclear Weapons?

A detailed new CRS memorandum examines “Legislation Limiting the President’s Power to Use Nuclear Weapons: Separation of Powers Implications.”

See also Defense Primer: President’s Constitutional Authority with Regard to the Armed Forces, CRS In Focus.

The uncertain scope of presidential authority to order the use of nuclear weapons was identified as a serious policy problem in 1984 by the late Jeremy J. Stone, then-president of the Federation of American Scientists. In an article published in Foreign Policy at the time, he concluded that “presidential first use [of nuclear weapons] is unlawful.”

* * *

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act, November 8, 2017

The Rohingya Crises in Bangladesh and Burma, November 8, 2017

Lebanon, updated November 9, 2017

Turkey: Background and U.S. Relations in Brief, updated November 9, 2017

El Salvador: Background and U.S. Relations, updated November 3, 2017

Guatemala: Political and Socioeconomic Conditions and U.S. Relations, updated October 17, 2017

Why is Violence Rebounding in Mexico?, CRS Insight, November 8, 2017

Comprehensive Energy Planning for Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands, CRS Insight, November 6, 2017

Resolutions of Inquiry: An Analysis of Their Use in the House, 1947-2017, updated November 9, 2017

Government Printing, Publications, and Digital Information Management: Issues and Challenges, November 8, 2017

Diversity Immigrant Visa Program, CRS Insight, November 9, 2017

Natural Disasters of 2017: Congressional Considerations Related to FEMA Assistance, CRS Insight, November 2, 2017

Refugee Admissions and Resettlement Policy, updated November 7, 2017

U.S. Circuit and District Court Nominees Who Received a Rating of “Not Qualified” from the American Bar Association: Background and Historical Analysis, CRS Insight, November 9, 2017

Consumer and Credit Reporting, Scoring, and Related Policy Issues, updated November 3, 2017

The U.S. Science and Engineering Workforce: Recent, Current, and Projected Employment, Wages, and Unemployment, updated November 2, 2017

Two USAF B-1B Lancer bombers fly alongside a JASDF F-2 over the East China Sea, October 21, 2017. Photo: PACAF, http://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001830673/

Two USAF B-1B Lancer bombers fly alongside a JASDF F-2 over the East China Sea, October 21, 2017. Photo: PACAF, http://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001830673/

By Adam Mount

As the Trump administration has prioritized North Korea, it has expanded military exercises around the peninsula to attempt to coerce the regime and assure US allies in Seoul and Tokyo. Perhaps the most dependable signal has been B-1B bombers missions to allied airspace. Though the flights were staged regularly during the Obama administration, they have become more frequent over the last year and more assertive. A review of official press releases and public reporting places this week’s flight of a conventional B-1B bomber near the Korean peninsula as the thirteenth of 2017.

The B-1B bomber originally entered service in 1986 as a supersonic nuclear bomber intended to serve as an interim step between the aging B-52 and the stealthy B-2. The B-1B’s nuclear mission was eliminated in 1994, after which the Air Force did not expend money to maintain its nuclear certification. To meet its obligations under the START treaties, the B-1B was converted to a conventional only platform by welding a metal sleeve onto the aircraft to prevent installation of cruise missile pylons and by removing cable connections in the weapon bays necessary to arm nuclear munitions. As part of New START, Russian observers inspected these modifications in 2011 and accepted the bomber as nonnuclear.

Though effectively nonnuclear, the regional perception of the B-1B is more nuanced. South Korea regularly refers to these flights as demonstrating “strategic assets,” a term usually applied to nuclear-capable platforms. By allowing the term to refer to the intercontinental range of the aircraft in this context, the United States mollifies South Korean officials who desire frequent signals of the US nuclear commitment without devaluing their nuclear signaling options.

Perceptions of the flights are additionally complicated by the fact that North Korea regularly refers to the B-1B as a nuclear platform. For example, North Korea decried this week’s flight a “nuclear strike drill.” Whether they do so for propaganda purposes or genuinely believe the aircraft is nuclear-capable is not clear, but defense strategists must consider the possibility that Pyongyang perceives a nuclear signal, even if the US officials did not intend to send one. What is clear is that the B-1B flights are of particular concern for Pyongyang. In August, 2017, state propaganda agency KCNA described “the operational plan for making an enveloping fire at the areas around Guam” by firing four Hwasong-12 IRBMs as a way of “containing” B-1B flights. The threat was an early attempt to brandish North Korea’s new long-range missiles in an attempt to coerce the US-South Korea alliance to modify its deterrent posture.

The missions are meant to ensure interoperability with allied forces and reassure allies of US defense commitments. US defense observers now widely doubt that the missions have any deterrent value and have instead become essentially routine signals of assurance to South Korea. North Korea now expects that any major test or provocation will elicit a B-1B flight in response. The assurance value of the flights is also an open question. Though ROK officials appreciate the signal, in the wake of the North Korean ICBM and thermonuclear weapons tests, they have also reportedly sought explicit signals of the US nuclear commitment as well as new conventional military signals. As such, the flights now probably have limited value to the alliance and several observers suggest that they could be modified if North Korea proved willing to negotiate tensions reductions measures.

B-1B missions more frequent and more assertive

‘For the first two months of the Trump administration, US Pacific Air Force did not carry out B-1B flights. From March through June, there was one flight per month. Since then, the alliance has conducted two B-1B flights to Korea per month, often in direct response to North Korean missile or nuclear tests. (USAF carried out additional bilateral missions with Japan as well as flights to the South China Sea.)

The most common mission profile has been “sequenced bilateral” missions in which usually two B-1Bs depart Guam, operate with Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) fighters near Japan (often near Kyushu), then subsequently with Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) fighters. About half the time, the bombers perform a simulated release of munitions or, as in (July, August, and September) release live or inert munitions onto Pilsung range, South Korea.

In September and October, the Air Force has begun to experiment with provocative new mission profiles. On 30 August, the B-1Bs were escorted for the first time by USMC F-35B aircraft from MCAS Iwakuni, Japan. The combination of the stealth fighter with the low-observable bomber will raise new concerns in Pyongyang about the abilities of their air defenses to detect and aerial intrusions. On 23 September, a B-1B mission for the first time flew Northeast of the Demilitarized Zone in international airspace. According to the US Air Force, North Korean air defenses failed to detect the flight, raising additional concerns about their capabilities.

On 11 October, CNN reported that a sequenced bilateral mission had performed a missile release drill in the East Sea (Sea of Japan), following which the B-1Bs and their ROKAF escorts crossed the peninsula and repeated the drill in the West Sea (Yellow Sea). Though B-1B exercises in the West Sea are not unprecedented, they are highly unusual. Additionally, this is the first known report of a missile release drill. The only missiles carried by the B-1B are the standard and extended-range variants of the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Munition, a long-range conventional cruise missile. Using the unclassified range of 500 miles, the JASSM-ER is capable of striking Chinese territory from most points in the East Sea and all of the West Sea. Beijing can be struck from the western half of the West Sea without flying north of the DMZ. This fact, combined with the proximity of the flight with US-ROK naval exercises in the West Sea around the time of the landmark Chinese Party Congress, suggests that the flight was an assertive signal not only to Pyongyang but also to Beijing.

Escalation risks

Though B-1B sequenced bilateral missions are now essentially routine, several trends raise the risk that these flights could contribute to military escalation.

This year’s B-1B flights occur in a political and military context distinct from previous administration. The Trump administration has through rhetorical comments and assertive military signaling around the peninsula has signaled that they could order military strikes on North Korea. In the last two weeks, the US-ROK combined forces have staged a series of highly provocative exercises ahead of Mr. Trump’s visit to the region (including major live fire naval exercises in the East and West Seas, drills to evacuate US civilians, port visits from American submarines and the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier, and announcements of upcoming deployments of F-35A to Japan and a three-carrier exercise in the Pacific).

Both in exercises and in other announcements, both the United States and South Korea have openly signaled that they are training for decapitation strikes against North Korea’s leadership. The signal is intended to convey to Pyongyang that ordering an attack could place their lives directly at risk and so to deter aggression. Yet, the administration’s rhetorical emphasis on forcible denuclearization of the peninsula may also give the impression that the United States could carry out assassination strikes even absent North Korean aggression. Combined with poor situational awareness of low-observable aircraft, the statements significantly raise North Korea’s incentives to escalate any crisis, the likelihood that they perceive US operations as a prelude to attack, and the risk of nuclear use.

To date, the Trump administration has not conducted a flight of a nuclear-capable B-2 stealth bomber to Korea. In 2013, the Obama administration did carry out a prominent flight from Whiteman AFB, MO to deliver inert munitions at Pilsung, the first and last time a B-2 mission has been disclosed publicly.

However, on 28-29 October, 2017, a B-2 flew from Whiteman to an undisclosed location in the Pacific. The bomber reportedly stopped on Guam, where it swapped crews with the engines running. Though a B-2 flight to Korea is unlikely to be radically destabilizing, in the context of a frequent White House comments playing up the possibility of military action and thinly-veiled nuclear threats to North Korea, planners should be aware that dispatching a B-2 is likely to be significantly more provocative than similar missions in previous years.

In the past, the United States had generally conducted Bomber Assurance and Deterrence (BAAD) flights with B-52 bombers. Because some B-52s are nuclear-capable, these missions were widely interpreted as nuclear deterrent signals. The most recent B-52 flight was in January, 2016, following the fourth DPRK nuclear test. Since 2004, either B-1B, B-52, or B-2 bombers have been rotationally stationed in Guam as part of the “Continuous Bomber Presence” Mission. In 2003, 12 B-52s and 12 B-1B bombers were alerted in the United States and subsequently deployed to Guam after 4 North Korean MiG fighters intercepted an American surveillance plane.

Lastly, the missions may be sending precisely the opposite message from the one intended. For the last several years, the United States has continued to work to improve trilateral coordination between the United States, South Korea, and Japan in order to present North Korea with a united front. However, the sequenced bilateral missions only serve underscore the reticence of the ROKAF and JASDF to operate together. Though JASDF fighters sometimes “hand off” the US bombers to ROK pilots, trilateral missions would send a far stronger signal of cohesion and capability, especially if conducted over ROK airspace.

These considerations raise serious questions about the value of B-1B assurance flights. At a time of rapid advance in North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities, with a US leadership that has made statements exacerbating South Korea’s concerns that the United States could decouple from its allies, it is unlikely that routine and symbolic flights are an effective signal either for deterring Pyongyang or assuring Seoul.

A new report by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the current plan to sustain and modernize US nuclear forces will cost $1.2 trillion over the next 30 years – or $41.4 billion per year.

A new report by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the current plan to sustain and modernize US nuclear forces will cost $1.2 trillion over the next 30 years – or $41.4 billion per year.

A study by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in 2014 projected the cost would be “over $1 trillion” over 30 years.

CBO projected in February 2017 that US nuclear forces will cost $400 billion over the 10-year period 2017 to 2026, or $40 billion per year. The projection was a 15% increase over the $345 billion estimate from January 2015 for the period 2015 to 2024.

Although the cost of US nuclear forces is limited compared with the size total defense budget, the cost will increase significantly in the next decade and compete with other non-nuclear defense priorities that also need funding. As a result, the current nuclear modernization plan is unsustainable.

The CBO report therefore presents nine options for changing the nuclear force structure and timing that the Trump administration and Congress could consider for reducing the cost of nuclear forces.

Repeated Warnings

Over the past several years, government officials have warned repeatedly that the current nuclear weapons modernization plan is unsustainable.

“There is a big bow wave out in the ‘20s,” the Air Force’s top program planner acknowledged in 2014. Together with the other nuclear modernization programs of the navy and the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the Pentagon’s top acquisition official warned later that year: “We’ve got a big affordability problem out there with those programs.” And in 2015 he said: “We do have a problem in the budget, and that problem is called the recapitalization of the triad … There is no way I can see that we can sustain the force structure and have a reasonable modernization program unless we get more money in the defense budget.”

As Brian McKeon, then principal deputy under secretary of defense for policy, stated in October 2015: “We’re looking at that big bow wave and wondering how the heck we’re going to pay for it, and probably thanking our stars we won’t be here to have to answer the question.”

His warning was echoed in 2016 by Jamie Morin, then DOD’s director of cost assessment and program evaluation, who concluded that, “unless the department was willing to divest the submarine leg of the triad – which we’re not – there’s no way to pay for [nuclear] modernization within the budget.”

“All Or Nothing” Arguments

Despite these warnings, which are now being further substantiated by the CBO report, military leaders, lawmakers, and defense contractors have been relentlessly pushing the excessive “all of the above” modernization program under a false premise of a choice between modernizing or not or having a nuclear deterrent or not. These “all or nothing” arguments set up roadblocks to deal with the real issue.

One “all or nothing” argument is that the United States needs to modernize, otherwise the nuclear deterrent will atrophy. But that’s not the choice. No one is arguing that the United States should not modernize its nuclear forces. The question is how much it can afford to modernize and for what purpose.

Another cost related “all or nothing” argument is that nuclear weapons only cost 4-5 percent of the defense budget. Surely, the United States can afford that. But that’s not the issue. The question is how those 4-5 percent compete with all the other defense needs the taxpayers also have to pay for.

And then there’s the “all or nothing” argument that the United States needs nuclear weapons, otherwise world wars will happen again. But that’s not the choice either. No one is arguing that the United States should unilaterally scrap its nuclear weapons. The question is now how the nuclear posture should be structured to best serve US national and international requirements in the decades ahead.

If the White House, DOD, and Congress don’t make the right choices about priorities now at the outset of the modernization programs, future defense budgets will make the decisions for them. Those decisions will be much harsher: delaying, scaling back, or outright cancelling programs. The effect will be a nuclear posture in turmoil where the budget axe determines the structure rather than carefully thought out planning.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The timing of report is impeccable (and FAS is honored to be referenced several times); only a couple of months before the Trump administration is expected to complete its Nuclear Posture Review.

That review is expected to carry forward the bulk of the Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plan, possibly sprinkled with a few additions such as a new sea-launched cruise missile and a low-yield warhead option for one of the navy’s ballistic missile warheads.

But that modernization plan is unsustainable.

It would be irresponsible if the NPR reaffirms the current modernization program without adjustments to mitigate the funding threats raised by the CBO report.

The CBO report includes plenty of options that the White House and Congress must consider for how to adjust the nuclear posture and the modernization plan to make it sustainable and still maintain a highly capable and survivable nuclear deterrent.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Image: https://www.facebook.com/lowapproach/posts/1468961693225121. Hat tip: Roel Stynen.

By Hans M. Kristensen

NATO reportedly has quietly started its annual Steadfast Noon nuclear strike exercise in Europe.

This is the exercise that practices NATO’s nuclear strike mission with dual-capable aircraft (DCA) and the B61 tactical nuclear bombs the US deploys in Europe.

In addition to nuclear-capable aircraft from Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, local spotters have also seen Czech Gripens and Polish F-16s. The United States will likely also participate with either F-16s from Aviano AB in Italy or F-15Es from RAF Lakenheath in England.

The non-nuclear aircraft from Czech Republic and Poland are participating under NATO’s so-called SNOWCAT (Support of Nuclear Operations With Conventional Air Tactics) program, which is used to enable military assets from non-nuclear countries to support the nuclear strike mission without being formally part of it. Polish F-16s have participated several times before, including in the Steadfast Noon exercise held at Ghedi AB in Italy in 2010.

This year’s Steadfast Noon exercise is taking place at two locations: Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium and Buchel Air Base in Germany. Both bases store an estimated 20 US B61 nuclear bombs for use by the national air forces. This is the second year in a row that the exercise has been spread across two bases in two countries. Last year’s exercise was held at Kleine Brogel AB (Belgium) and Volkel AB (Netherlands). The multi-base Steadfast Noon exercises are often coinciding with or preceding/following other exercises such as Decisive North and Cold Igloo.

There are currently an estimated 150 B61 bombs deployed at six bases in five European countries (see figure below).

Weapons were previously also deployed at RAF Lakenheath but withdrawn sometime between 2004 and 2008. Weapons were also withdrawn from Araxos AB (Greece) in 2001. Consolidation (but not complete withdrawal) also happened in Germany and Turkey (for these earlier changes, see my report from 2005).

In addition to the countries with nuclear-capable aircraft – Belgium, Germany Italy, Netherlands, Turkey (note that the status of Turkey’s nuclear role is unclear, but it’s F-16s are still nuclear-capable), and the United States, there will likely be participation from other NATO countries under the SNOWCAT program.

NATO is adjusting its nuclear posture in reaction to the new adversarial relationship with Russia. The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review is expected to reaffirm the continued deployment and modernization of US non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. But there is a push from hardliners inside NATO to increase the readiness and planning for the non-strategic aircraft. Others say it is not necessary. Last month several B-52 bombers forward-deployed to Europe in support of NATO and many see that as sufficient signaling at the nuclear level. Overall, moreover, NATO’s reaction to Russia is focused on providing non-nuclear defense to Europe.

In a broader context, the nuclear exercise has not been officially announced and NATO is very tight-lipped about it because of the political sensitivity of this mission in mainly western NATO countries. The secrecy of the exercise is interesting because NATO only a few weeks ago complained that Russia was not being transparent about its Zapad exercise. Seems like both sides could do better.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

By Hans M. Kristensen

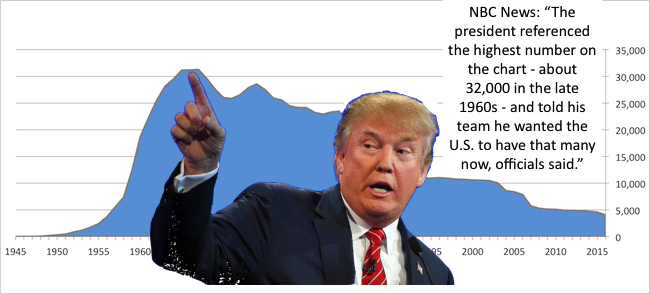

According to an NBC News report, President Donald Trump said during a meeting at the Pentagon on July 20 that “he wanted what amounted to a nearly tenfold increase in the U.S. nuclear arsenal,” according to three officials who were in the room.

Trump’s statement came in response to a chart shown during the meeting on the history of the U.S. and Russia’s nuclear capabilities. Trump reportedly referenced the highest number on the chart – about 32,000 in the late 1960s – and “told his team he wanted the U.S. to have that many now, officials said.”

It is often a mystery how Trump reaches his conclusions and his statement about increasing the arsenal is clearly not based on rational reasoning or factual information. Presidential advisors at the meeting reportedly explained why an expansion was not feasible (that must have been an embarrassing moment) and officials said his comments “raised questions about his familiarity with the nuclear posture and other issues.”

Despite Trump’s fantasies, the United States is unlikely to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile. There are currently about 4,000 nuclear warheads in the Pentagon’s stockpile, of which roughly 1,800 are deployed on ballistic missiles and at bomber and fighter bases. The military says it has too many and could meet national and international commitments with up to one-third fewer deployed weapons. And the trend is that the stockpile will continue to decline over the next decade because of changes being made to the force structure as part of the current modernization program.

Fun facts added: The biggest stockpile increase in one year was 1959-1960 when the United States added 6,340 warheads. During the 72 years since the first production of nuclear weapons in 1945, the average number of nuclear weapons added to the U.S. stockpile per year is 56. At that rate, it would take 487 years to increase the stockpile to the peak of 31,255 warheads in 1967.

Yet Trump’s repeated statements demonstrate a predisposition toward more nuclear weapons. The big question is to what extent that will influence the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) currently under preparation. Trump might try to slow the reduction and force the military to hang on to excess warheads even though they don’t need them or want them.

More likely is that Trump with the NPR will try to further increase the capabilities of the remaining weapon types. Again, enhancements are already being added as part of the ongoing modernization programs, but there are people involved in the NPR process that are advocating doing more. The White House apparently is in favor of researching and developing a ground-launched missile that, if tested and deployed, would violate the INF treaty (this is a Cold War tit-for-tat response to Russia’s violation of the treaty).

Despite current challenges to the international nuclear weapons arms control efforts, it is essential that the Trump administration reaffirms long-standing U.S. nuclear policy to reduce nuclear arsenals and work toward the eventual elimination of nuclear weapons. Doing otherwise might satisfy defense hawks with no gain for national security, but it would also embolden other nuclear-armed states to further increase their arsenals to the detriment of the security of the United States and its allies.

Background:

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States has now reached the limits for all three weapons categories under the New START treaty.

The latest data published by the State Department shows that the United States for the first time since the treaty entered into force in 2011 has reached the limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. The 660 deployed launchers are also below the treaty limit of 700 and the 1,393 deployed warheads is well below the limit of 1,550. As such, the United States is now technically in compliance with the treaty.

The latest US reductions are the result of denuclearization of bombers and reduction of launch tubes on the Ohio-class submarines.

The data shows that Russia has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 235 in the past 12 months and is now only 11 warheads above the New START treaty limit of 1,550 warheads to be achieved by February 2018. Russia is already below the treaty limit on deployed launchers as well as deployed and non-deployed launchers.

Russia’s increase in deployed strategic warheads between 2013 and 2016 triggered widespread claims by defense hawks that Kremlin was building up its nuclear forces. As I previously pointed out, that was wrong and the result of temporary fluctuations in the Russian force structure. Russia is modernizing, not increasing, its nuclear arsenal.

The Bigger Picture

The latest data shows that the United States has a significant advantage over Russia in deployed strategic launchers; 660 versus 505. The 155-launcher disparity means Russia emphasizes multiple warhead loading on its ICBMs while the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carrying only a single warhead each. A future follow-on treaty will need to address this disparity, which is unhealthy for long-term strategic stability.

Although the United States and Russia are now at, near, or below the limits of the New START treaty, the warheads counted by the treaty only constitute a small fraction of the two countries’ total warhead inventories.

We estimate that Russia has a military stockpile of 4,300 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 7,000 warheads. For its part, we estimate the United States has a military stockpile of 4,000 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 6,800 warheads.

These arsenals are vastly in excess of the nuclear force levels maintained by other nuclear-armed states and constitute more than 90% of the world’s combined inventory of nearly 15,000 nuclear warheads.

Moreover, the New START treaty does not limit the 2,350 non-strategic nuclear warheads we estimate that Russia and the United States have in their arsenals combined. Both sides are modernizing their non-strategic nuclear forces.

Finally, the New START treaty expires in 2021 unless extended for another five years. The Trump administration has previously indicated opposition to extending the treaty, although recent discussions with Russia may seek to change that. A follow-on treaty seems unlikely given the current political climate but could easily be achieved by reducing the excess nuclear forces of Russia and the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A so-called loophole might allow a non-nuclear weapon state (NNWS) to use a naval reactor program to acquire nuclear weapons by taking nuclear material outside of safeguards and then potentially diverting some of that material. Additionally, nuclear-armed states with nuclear-powered warships might use their naval reactor programs to justify keeping a substantial inventory of highly enriched uranium (HEU)3 that could be quickly converted to nuclear weapon use or low enriched uranium (LEU) that could also be converted, but with more steps required to boost the LEU to HEU. Recognizing these and related nonproliferation and disarmament challenges, this report presents a proposal for the 2020 Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference: a naval reactor quid pro quo (QPQ) for nuclear- armed states4 and NPT non-nuclear weapon states.

https://issuu.com/fascientists/docs/the-nonproliferation-and-disarmamen?utm_medium=referral&utm_source=fas.org

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has quietly published a corrected report on the world’s Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats that deletes a previously identified Russian ground-launched cruise missile.

The earlier version, published on June 26, 2017, identified a “ground” version of the 3M-14 land-attack cruise missile that appeared to identify the ground-launched cruise missile the United States has accused Russia of testing and deploying in violation of the 1987 INF Treaty.

The corrected version, available on the NASIC web site, no longer lists a “ground” version of the 3M-14 (popularly referred to as Kalibr) but only ship- and submarine-launched versions of the missile.

Apart from correcting the spelling of the North Korean Bukkeukseong-2 medium-range ballistic missile and downgrading the operational status of the Iranian Shahab-3 medium-range ballistic missile from deployed with “fewer than 50” launchers to “undetermined,” the deletion of the “ground” version of the Russian 3M-14 appears to be the only correction in the new NASIC report. (Curiously, the report still doesn’t identify the Russian Kh-102 air-launched cruise missile). Other than these changes buried deep in the report, however, there are no external markings on the new version to indicate that it has been changed (the URL identifies the new report date as July 21, 2017).

The older version of the NASIC report has been deleted from the NASIC web site, but a copy can be found here.

Implications and Recommendations

The deletion of the 3M-14 as the apparent INF-violating missile from the NASIC report is noteworthy, but it doesn’t actually change much. In essence, it returns the public INF debate to square one where it was three months ago. The correction even helps clear up confusion about the origins and status of the alleged Russian INF violation (several of us in the GNO community have been trying to crosscheck and cross-reference missile designations).

The United States has refused to publicly identify the INF-violating ground-launched cruise missile, apparently to protect intelligence sources. Instead, government sources have described what the missile is not (see here for previous statements). Although NASIC took the time to correct the error, it missed the opportunity to identify the actual INF-violating ground-launched cruise missile.

The correction refocuses the attention back on what I’ve heard all along: That the Russian INF-violating missile is thought to be a modification of the ground-launched SSC-7, a short-range cruise missile used on the Iskander system. But U.S. intelligence officials are adamant that the INF-violating missile is not the Iskander but a state-of-the-art missile. The new missile is known in the U.S. intelligence community as the SSC-8. The launcher itself apparently is physically different from the one used for the SSC-7. I co-authored a paper about this with the Deep Cuts Commission in April.

Apparently one battalion is operational and a second is fitting out, potentially embedded with Islander battalions starting in central Russia, and deployments are expected eventually in all four Russian military districts. So far, however, according to U.S. officials, the SSC-8 does not appear to give Russia any military advantage in Europe. And the U.S. military already has the military capability to counter the SSC-8 with sea- and air-launched cruise missiles and other means.

The U.S. refusal to identify the missile has given the Russian government the public space to “play ignorant” and claim it doesn’t know what the U.S. government is talking about. Similarly, the secrecy has made it difficult for allied governments to verify the claim and privately and publicly assist the United States with putting pressure on Russia to return to treaty compliance. That, in turn, has allowed hardliners in the U.S. Congress to propose that the United States should also develop it’s own ground-launched cruise missile (something the U.S. military does not believe is necessary).

Rather than making a bad situation worse, in order to sustain and increase pressure on Russia to return to INF compliance, the United States must reinforce its own commitment to the treaty by rejecting any Cold War proposal to mimic Russia’s bad behavior by developing a U.S. ground-launched cruise missile and instead focus potential military responses on existing forces already widely available, remove public ambiguity by identifying the Russia missile and disclose the information it has shared with Russia (if it can tell the Kremlin, then it can also tell the rest of the world), increase intelligence sharing with allies to improve their ability to work the issue with Russia directly, and pursue the matter directly with Russia in the Special Versification Commission of the INF treaty.

Background information:

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

This report examines the nuclear dynamics and implications for strategic relations in a world where four nuclear-armed states are developing strategic ballistic missile defenses (BMD). These states are the United States, Russia, China, and India. Each state appears to have the common rationale of wanting at least limited protection against ballistic missile attacks, and all will respond with various countermeasures to ensure that their nuclear deterrents are viable as they react to missile defense developments in other countries. In addition, we have found that each state has differing motivations for strategic BMD.

https://issuu.com/fascientists/docs/nuclear-dynamics-in-a-multipolar-st_908e6ac1e06017