DIA Estimates For Chinese Nuclear Warheads

During a Hudson Institute conference on Russian and Chinese nuclear modernizations, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lt. Gen. Robert Ashley said in prepared remarks: “Over the next decade, China is likely to at least double the size of its nuclear stockpile…”

This projection is new and significantly above recent public statements by US government agencies. But how reliable is it and how have US agencies performed in the past?

The public record is limited because estimates are normally classified and agencies and officials are reluctant to say too much. But a few examples exist from declassified documents and public statements. These estimates vary considerably – some seemed downright crazy.

But before analyzing DIA’s projection for the future, let’s examine what the estimated Chinese nuclear stockpile looks like today.

Current Chinese Stockpile Estimate

While warning the Chinese stockpile will “at least double” over the next decade, Lt. Gen. Ashley’s prepared remarks did not say what it is today. But in the follow-up Q/A session, he added: “We estimate…the number of warheads the Chinese have is in the low couple of hundreds.

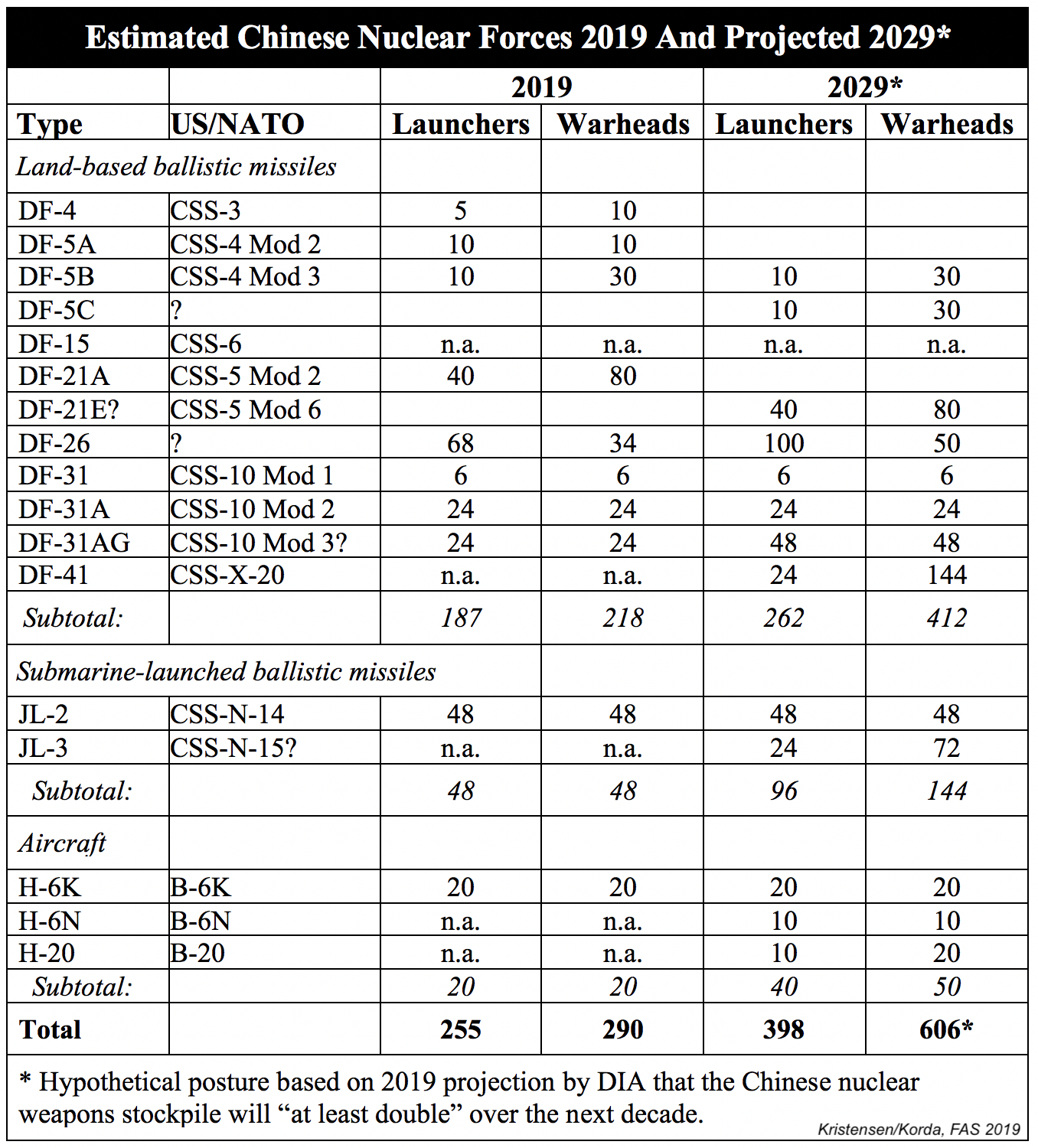

That estimate is close to statements made by DOD and STRATCOM nearly a decade ago. In our forthcoming Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces (scheduled for publication in July 2019), we estimate the Chinese stockpile now includes approximately 290 warheads and is likely to surpass the size of the French nuclear stockpile (~300 warheads) in the near future.

Earlier Chinese Stockpile Estimates

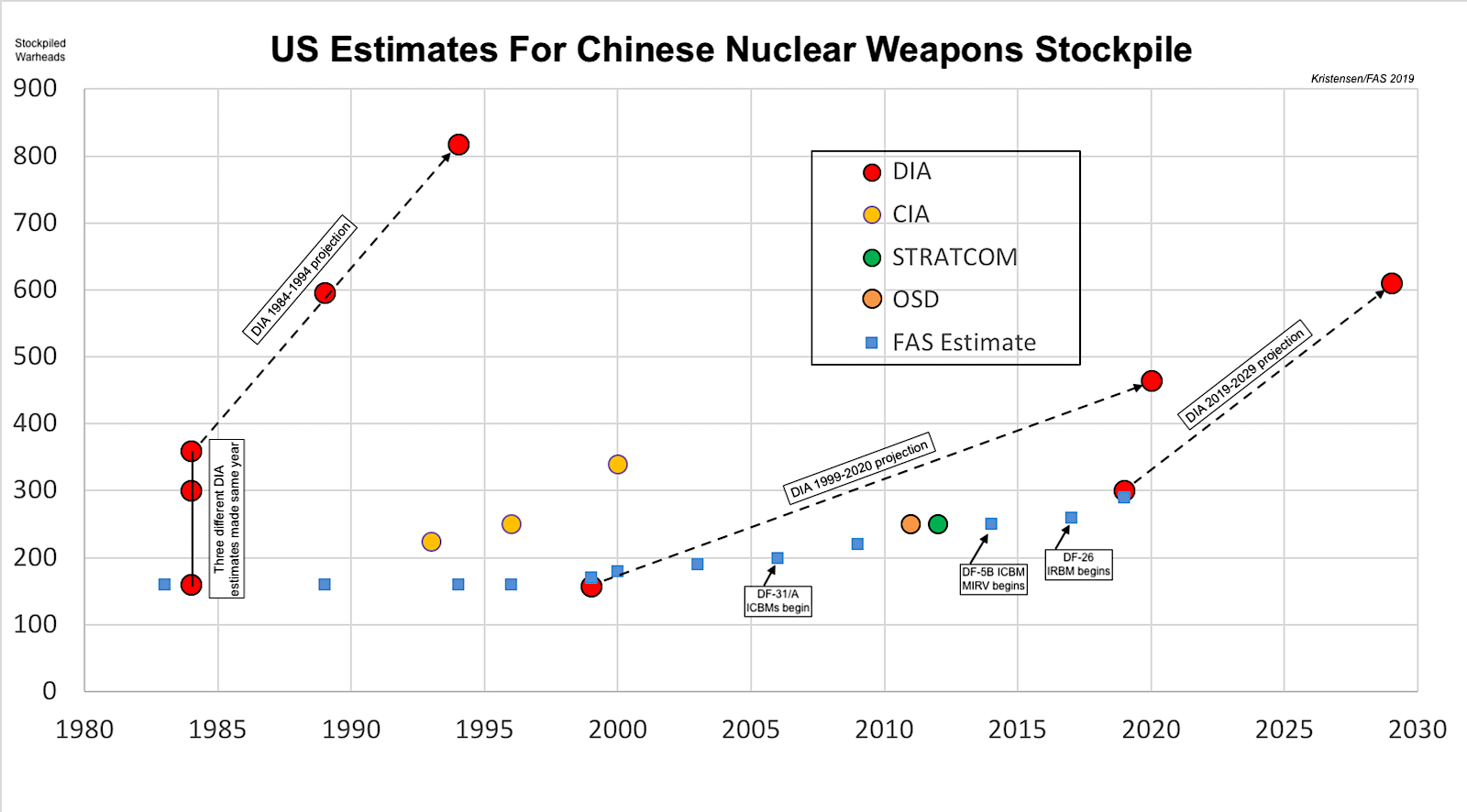

Earlier projections made by US agencies of China’s nuclear stockpile have varied considerably. DIA’s estimates have consistently been higher – even extraordinarily so – than that of other agencies (see graph below). The wide range reflects an enormous uncertainty and lack of solid intelligence, which makes it even more curious why DIA would make them. This record obviously raises questions about DIA’s latest projection.

In April 1980s, for example, DIA published a Defense Estimate Brief with the title: Nuclear Weapons Systems in China. The brief, which was prepared by the China/Far East Division of the Directorate for Estimates and approved by DIA’s deputy assistant director for estimates, projected an astounding growth for China’s nuclear arsenal that included everything from ICBMs, MRBMs, SRBMs, bombs, landmines, and air-to-surface missiles. The brief concluded a curious double estimate of 150-160 warheads in the text and 360 warheads in a table and projected an increase from 596 warheads in 1989 to as many as 818 by 1994. The brief was partially redacted for many years but it has since been possible to reconstruct in its entirety because of inconsistencies in the processing of different FOIA requests.

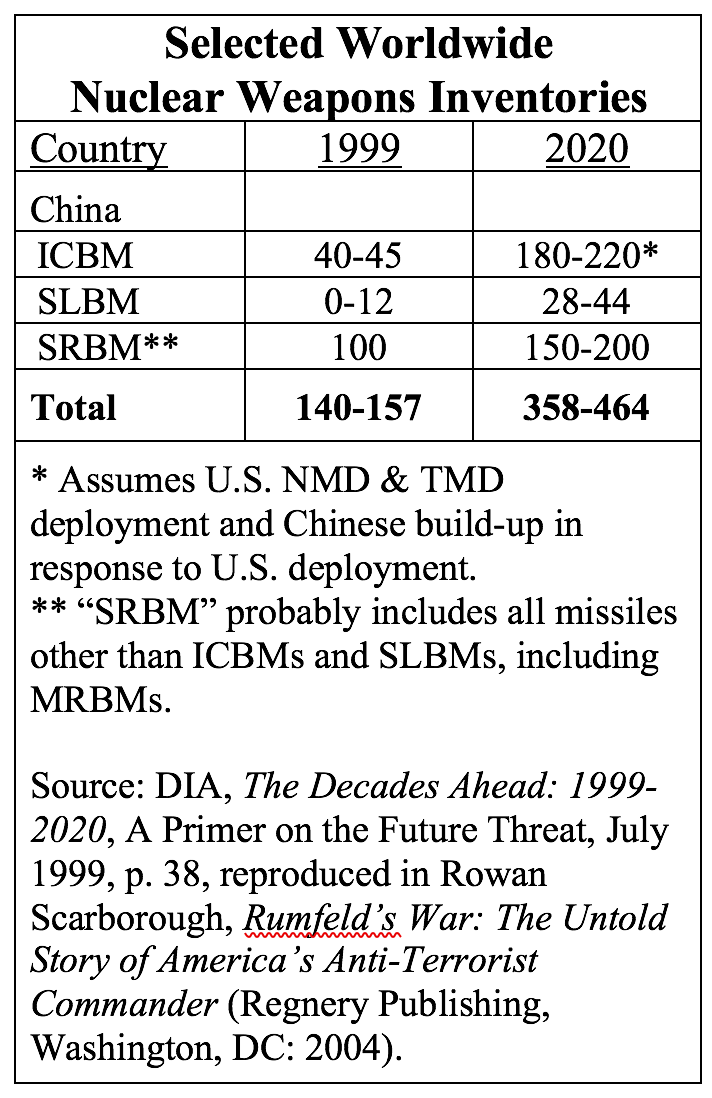

In the 1990s, CIA published three estimates, all significantly lower than the DIA projection from 1984. But DIA apparently was reworking its methodology because in 1999 it published A Primer On The Future Threat that was lower than the CIA estimate but projected an increase of the Chinese stockpile from 140-157 warheads to 358-464 warheads in 2020. The Primer predicted that deployment of US missile defenses would cause China to significantly increase its ICBM force, a prediction that has come through to some extent and is now ironically used by DIA and others to warn of a growing Chinese nuclear threat against the United States.

In the 1990s, CIA published three estimates, all significantly lower than the DIA projection from 1984. But DIA apparently was reworking its methodology because in 1999 it published A Primer On The Future Threat that was lower than the CIA estimate but projected an increase of the Chinese stockpile from 140-157 warheads to 358-464 warheads in 2020. The Primer predicted that deployment of US missile defenses would cause China to significantly increase its ICBM force, a prediction that has come through to some extent and is now ironically used by DIA and others to warn of a growing Chinese nuclear threat against the United States.

Following an intense debate in 2010 about Senate approval of the New START treaty, then-principle deputy undersecretary of defense for policy James Miller told Congress in 2011: “China is estimated to have only a few hundred nuclear weapons….”

And when false rumors flared up in 2012 that China had hundreds – even thousands – of warheads more than commonly assumed, STRATCOM commander Gen Kehler rebutted the speculations saying: “I do not believe that China has hundreds or thousands more nuclear weapons than what the intelligence community has been saying,” which is “that the Chinese arsenal is in the range of several hundred” nuclear warheads.

Since then, China has started to deploy the modified silo-based DF-5B ICBM that is equipped with multiple warheads (MIRV) – part of the response to the US missile defenses that DIA predicted in 1999, and deployed a significant number of dual-capable DF-26 IRBMs. Even so, Ashley’s most recent statement roughly matches the estimates made by Miller and Kehler nearly a decade ago, when he says: “We estimate…the number of warheads the Chinese have is in the low couple of hundreds.”

How Could The Chinese Stockpile More Than Double?

Although Ashley predicted a significant expansion of the Chinese stockpile, he did not explain the assumptions that go into that assessment. What would China have to do in order to more than double its stockpile over the next decade?

There are several potential options. China could field a significant number of additional launchers, or deploy significantly more MIRVs on some of its missiles, or – if the MIRV increase is less dramatic – a combination of more launchers and more MIRV. It seems likely to be the latter option.

Additional MIRVing seems to be an important factor. China is developing the road-mobile DF-41 ICBM that is said to be capable of carrying MIRV. It is also developing a third modification of the silo-based DF-5 (DF-5C) that may have additional MIRV capability compared with the current DF-5B. Finally, the next-generational JL-3 SLBM could potentially have MIRV capability, although I have yet to see solid sources saying so. There are many rumors about up to 10 MIRV per DF-41 (even unreliable rumors about MIRV on shorter-range systems), but if China’s decision to MIRV is a response to US missile defenses (which DIA and DOD have stated for years), then it seems more likely that the number of warheads on each missile is low and the extra spaces used for decoys.

China is also expanding its SSBN fleet, which could potentially double in size over the next decade if the production of the next-generation Type-096 gets underway in the early-2020s. And China reportedly has reassigned a nuclear mission to its bombers, is developing a new nuclear-capable bomber, and an air-launched ballistic missile that might have a nuclear option. Assuming a few bomber squadrons would a nuclear capability by the late-2020s, that could help explain DIA’s projection as well. Altogether, that adds up to a hypothetical arsenal that could potentially look like this in order to “at least double” the size of the stockpile:

Conclusions

Whether DIA’s projection comes through of a Chinese stockpile “at least double” the size of the current inventory remains to be seen. Given DIA’s record of worst-case predictions, there are good reasons to be skeptical. It would, at a minimum, be good to hear what the coordinated Intelligence Community assessment is. Does the Director of National Intelligence agree with this projection?

That said, the Chinese leadership has obviously decided that its “minimum deterrent” requires more weapons. To that end, the debate over how much is enough, what the Chinese intentions are, and what the US response should be, are important reminders that the Chinese leadership needs to be more transparent about what its modernization plans are. Lack of basic information from China fuels worst-case assumptions in the United States that can (and will) be used to justify defense programs that increase the threat against China. The recommendation by the Nuclear Posture Review to develop a new nuclear-armed sea-launched cruise missile is but one example. Both sides have an interest in limiting this action-reaction cycle.

Even if DIA’s projection of a more than doubling of the Chinse stockpile were to happen, that would still not bring the inventory anywhere near the size of the US or Russian stockpiles. They are currently estimated at 4,330 and 3,800 warheads, respectively – even more, if counting retired, but still largely intact, warheads awaiting dismantlement.

But despite the much smaller Chinese arsenal, a significant expansion of the stockpile would likely make US and Russia even more reluctant to reduce their arsenals – a reduction the Chinese government insists is necessary first before it will join a future nuclear arms limitation agreement. So while China’s motivation for increasing its arsenal may be to reduce the vulnerability of its deterrent, it may in fact also cause the United States and Russian to retain larger arsenals than otherwise and even increase their capabilities to threaten China.

Whether DIA’s projection pans out or not, it is an important reminder of the increasingly dynamic nuclear competition that is in full swing between the large nuclear weapons states. The pace and scope of that competition are intensifying in ways that will diminish security and increase risks for all sides. Strengthening deterrence is not always beneficial and even smaller arsenals can have significant effects.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

The Pentagon’s 2019 China Report

[Updated] The Pentagon has released its 2019 version of its annual report on China’s military developments. The report describes a Chinese military in significant modernization. There is much to digest but this review only examines the nuclear portion.

The DOD report does not indicate how many nuclear warheads China has to arm these forces. Our current estimate for 2019 is approximately 290 warheads.

Although China’s nuclear arsenal is far smaller than that of Russia and the United States, the growing and increasingly capable Chinese nuclear arsenal is pushing the boundaries of China’s “minimum” deterrent and undercutting its promise that it “will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country.” And the more the Chinese arsenal grows, the less likely it is that Russia and the United States will significantly reduce theirs.

Land-Based Missiles

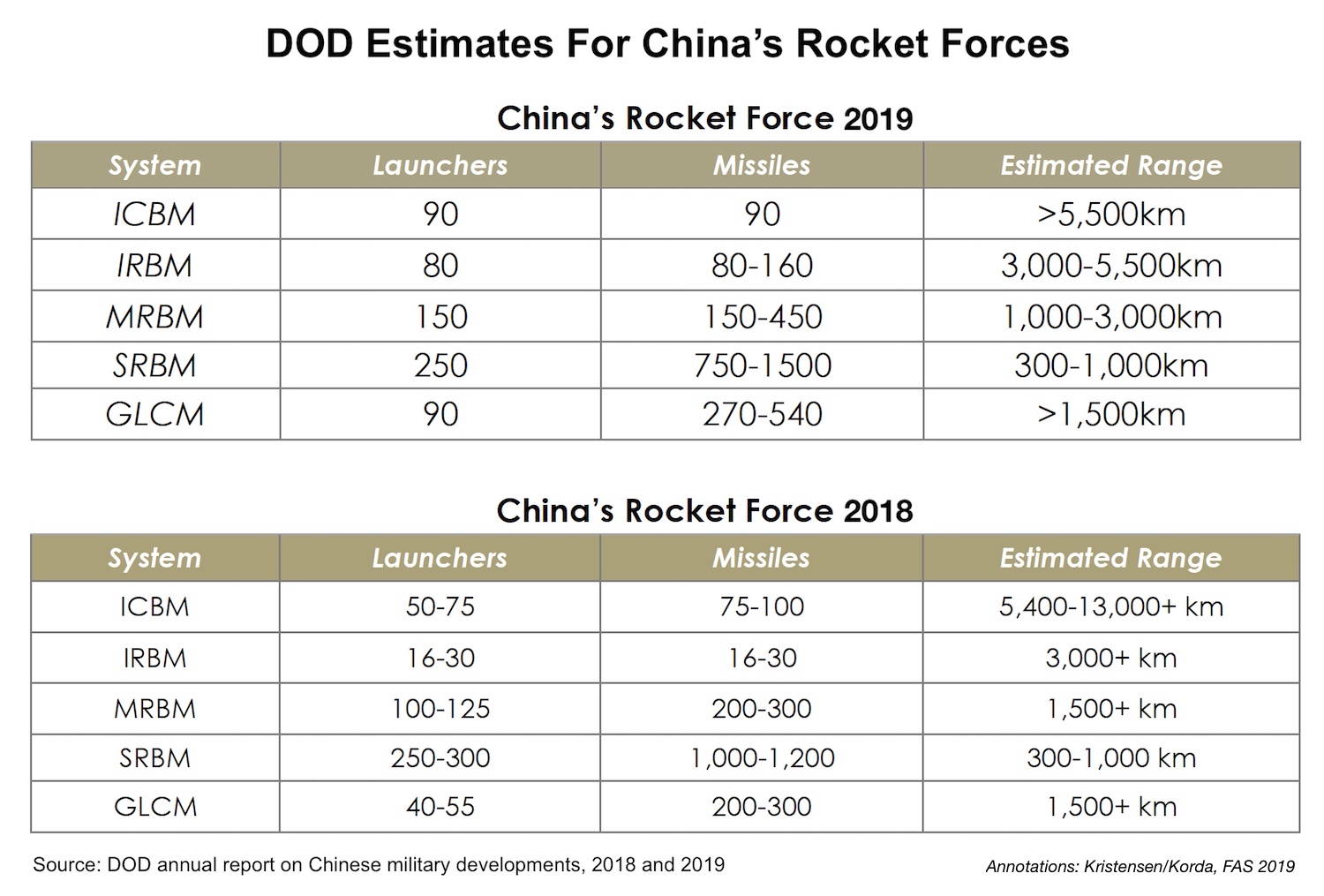

The DOD report describes a land-based missile force that is undergoing significant development with increases in almost all categories. China is clearly building up, even though it is still significantly below the nuclear force levels of Russia and the United States.

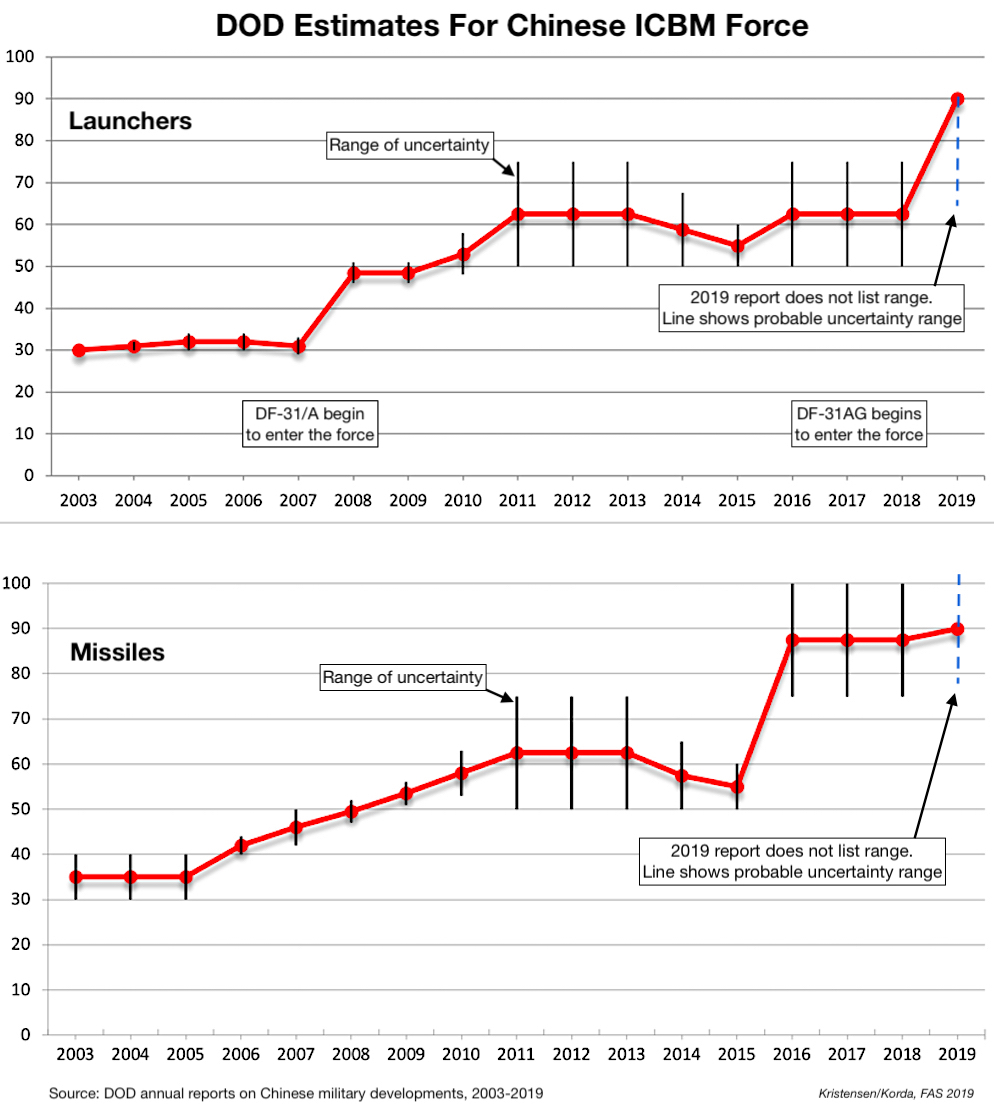

The report states that China now has 90 ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles) with as many missiles. This is close to the 75-100 missiles reported for the past several years. But the number of launchers for those ICBMs is significantly higher this year: 90 versus the 50-75 listed in last year’s report. For that to be true, China would have fielded 15-40 new launchers, or the equivalent of two to six new brigades (assuming six launchers per ICBM brigade). Two or three new brigades seem more plausible so I suspect the range estimate is at the high end and might be 65-90. This increase is probably caused by the fielding of the improved road-mobile DF-31AG launcher.

Each ICBM launcher normally is attributed one missile, except in previous years the DOD reports have presented more missiles than launchers. Part of that can be explained by the old liquid-fuel roll-out-to-launch DF-4, which is thought to have at least one reload. The DOD says the DF-4 is still operational, so it’s a mystery why the table doesn’t reflect that (all other missile categories are listed with a range instead of a single number). Since 2003, DOD’s estimates for Chinese ICBMs have fluctuated considerably:

DOD’s estimates for Chinese missiles have fluctuated considerably over the years. Click on graph to view full size.

The long-awaited road-mobile DF-41 ICBM is still not listed as operational but continues development. DOD has reported this system in development since at least 1997. Once it becomes operational, this solid-fuel missile might also replace the old liquid-fuel DF-5A/B in the silos. The DF-41 is said to be MIRV-capable, as is the DF-5B. The DOD report does not mention a DF-5C version that has been rumored in some outlets.

The most dramatic development is in the IRBM (intermediate-range ballistic missile) force, which has increased significantly since last year from 16-30 launchers to 80. That indicates the dual-capable DF-26 is being fielded more rapidly than anticipated, and might now be deployed at four bases. As with the ICBMs, the IRBM launcher estimate this year is a single number rather than a range used last year, which probably means that 80 is the upper number of a 65-80 range. The Chinese media in January 2019 described a DF-26 deployment that was later geo-located to a new missile training area in the Inner Mongolia province.

The MRBM (medium-range ballistic missile) force has also increased, mainly because of the fielding of conventional versions. The DOD report lists 150 MRBM launchers with 150-450 missiles available. This includes four versions – DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2), DF-21C (CSS-5 Mod 4), DF-21D (CSS-5 Mod 5), and DF-21E (CSS-5 Mod 6) – of which two are nuclear: DF-21A and DF-21E (note: DOD has not yet identified the CSS-5 Mod 6 as DF-21E but it is assumed given naming of other versions). Most of the MRBMs are conventional. The report does not reveal how many of the launchers are nuclear, but it might be no more than 40-50 of the 150 MRBM launchers. There appears to be a problem with the breakdown because the DOD report states elsewhere that “the PLA is fielding approximately 150-450 conventional MRBMs.” That would imply all missiles listed in the table are conventional, which is clearly not the case.

SRBMs (short-range ballistic missiles) constitute the largest group of Chinese missiles. The number of launchers is a little lower than last year, while the uncertainty about the number of missiles available for them has increased to 750-1,500 versus 1,000-1,200 in 2018. There are many rumors on the Internet that some of China’s SRBMs (DF-11, DF-15, and DF-16) have nuclear capability. But neither the DOD report nor NASIC attributes such a capability to this group of missiles. On the contrary, the DOD report explicitly states that these weapons are part of “China’s conventional missile force.”

Finally, DOD says China has increased its ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) force from 40-55 launchers in 2018 to 90 today. The missiles available for those launchers has increased from 200-300 to 270-540, so a significant uncertainty. The GLCM is not nuclear-capable.

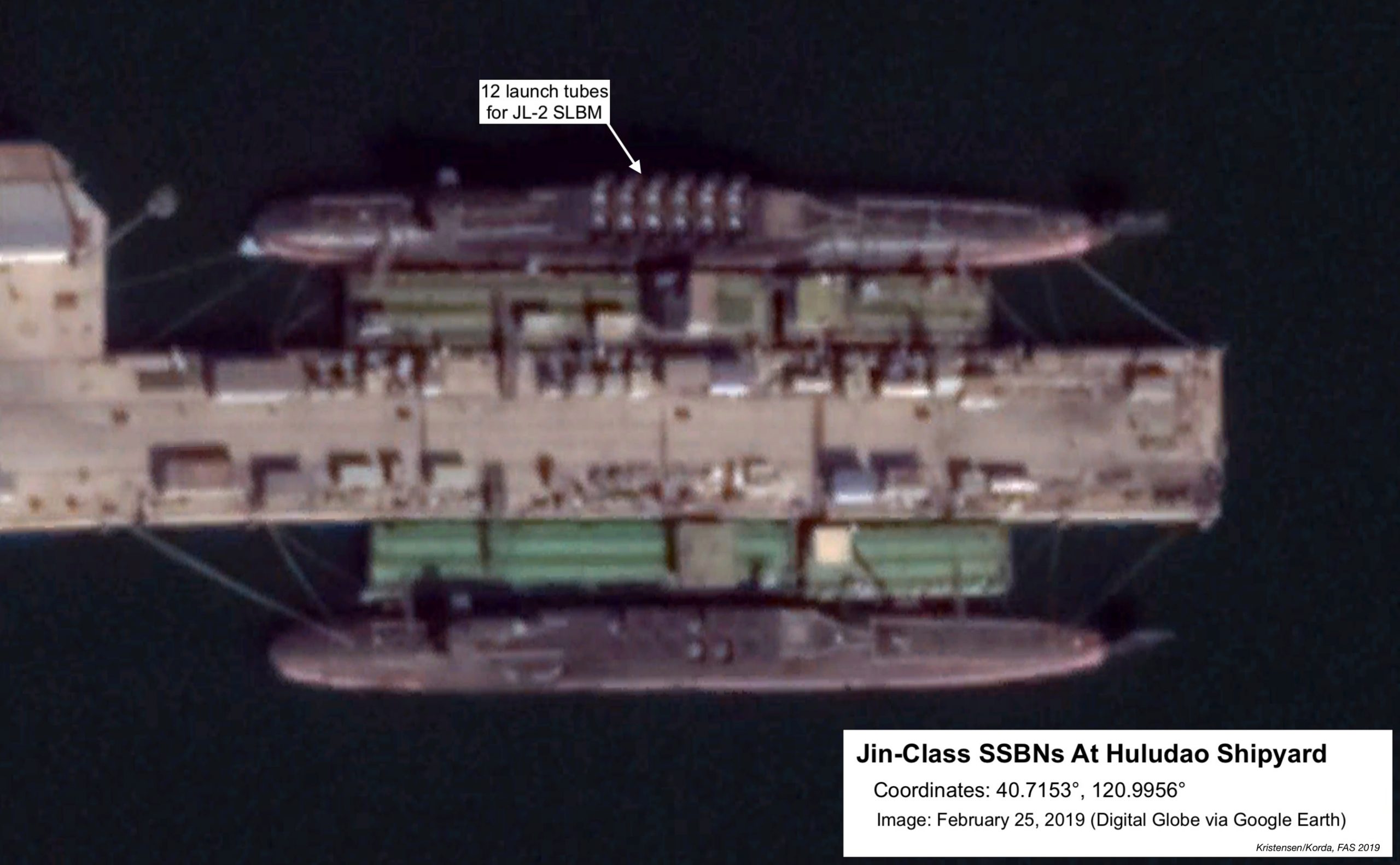

The SSBN Fleet

China currently operates four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs (nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines) with two more fitting out. The four operational SSBNs are all based at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. The information about the fifth and sixth hulls is new and expands observations of a fifth hull in 2018. Once completed, this force will be capable of carrying up to 72 JL-2 SLBMs with as many warheads, 24 more than the four operational can currently carry.

The Pentagon report says the four operational SSBNs “represent China’s first credible, sea-based nuclear deterrent,” although the report doesn’t say if the submarines are armed with missiles under normal circumstances, if the warheads for those missiles are installed, or if the submarines sail on deterrent patrols.

The six Jin-class SSBNs will be followed by a next-generation SSBN known as Type 096, which DOD projects might begin construction in the early-2020s. The new SSBN class will carry the follow-on JL-3 SLBM but China will probably operate the two types concurrently.

The Bomber Force

The annual DOD reports have become more specific about the nuclear role of Chinese bombers in recent years. While the 2017 version said the “PLAAF does not currently have a nuclear mission,” the 2018 report said “the PLAAF has been newly re-assigned a nuclear mission” and that the “H-6 and future stealth bomber could both be nuclear capable.”

We have for years assessed that part of the Chinese H-6 bomber force had a dormant nuclear capability with a small number of bombs in storage. Aircraft, including the H-6, were used to deliver at least 12 of the nuclear weapons that China detonated in its nuclear testing program between 1965 and 1979, and a variety of what’s said to be tactical and strategic bombs can be seen displayed in Chinese museums.

The new report references unidentified “Chinese media” saying since 2016 that the upgraded H-6K is a dual nuclear-conventional bomber. The report says China is fielding the H-6K in greater numbers with land-attack cruise missiles and more efficient engines. Armed with cruise missiles, the H-6K can target Guam, the report says. Some H-6Ks are being equipped with air-refueling capability, and a new refuellable bomber is said to be in development that could reach initial operational capability before the next-generation H-20 bomber.

The DOD report does not identify any of China’s air-launched cruise missiles (ALCMs) as nuclear-capable. An Air Force Global Strike Command command briefing in 2013 listed the CJ-20 as nuclear-capable and a DOD fact sheet published along with the 2018 Nuclear Posture Review lists both nuclear ALCM and SLCM (sea-launched cruise missile) under China. But neither NASIC nor the public annual threat assessments from the Intelligence Community have attributed nuclear capability to Chinese ALCMs or SLCMs.

US officials have publicly identified two new Air-Launched Ballistic Missiles (ALBMs) in development, “one of which may include a nuclear payload.” The ALBM, designated by the US Intelligence Community as CH-AS-13, would be carried on a modified H-6 known as H-6N, potentially the new refuellable bomber that might become operational before the H-20.

These developments, if and when they become fully operational, would give China a real nuclear Triad for the first time.

The Road Ahead

In 2004, the Chinese government declared: “Among the nuclear-weapon states, China…possesses the smallest nuclear arsenal.” The wording “nuclear-weapon states” probably referred to the five NPT-declared nuclear weapon states.

But the growing and increasingly capable Chinese nuclear arsenal is pushing the boundaries of China’s “minimum” deterrent and undercutting its promise that it “will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country.”

China might not consider itself to be in a formal arms race with any particular country, but it is clear that the United States is seen as the primary driver. Since 2004, the size of China’s nuclear arsenal has surpassed that of Britain and we project that China in the near future will surpass France as the world’s third-largest nuclear-armed state – although it will still be far below the levels of the nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States.

President Trump recently declared his interest in including China in a future nuclear arms limitation agreement. His instinct is correct but it’s entirely unclear what he would offer China in return for limits on China’s nuclear forces, given how much smaller China’s arsenal is. Moreover, it should not be done at the expense of deciding now to extend the New START treaty with Russia. Indeed, China’s growing arsenal illustrate the importance of Russia and the United States maintaining existing arms control agreements and taking steps to reduce their arsenals further in consultations with China.

The Chinese leadership, however, can no longer hide behind the response: “Come down to our level. Then we’ll talk.” Beijing must be mindful that China’s growing nuclear arsenal – as well as its general military modernization and territorial pursuits – can serve to limit US willingness to reduce its arsenal further and may even lead to decisions to increase the capabilities. The Trump administration’s plan to abandon the INF treaty with Russia and add a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile to the arsenal are just two examples; they have China written all over it.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Pentagon Slams Door On Nuclear Weapons Stockpile Transparency

The Pentagon has decided not to disclose the current number of nuclear weapons in the Defense Department’s nuclear weapons stockpile. The decision, which came as a denial of a request from FAS’s Steven Aftergood for declassification of the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpile number, reverses the U.S. practice from the past nine years and represents an unnecessary and counterproductive reversal of nuclear policy.

The United States in 2010 for the first time declassified the entire history of its nuclear weapons stockpile size, a decision that has since been used by officials to support U.S. non-proliferation policy by demonstrating U.S. adherence to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), providing transparency about U.S. nuclear weapons policy, counter false rumors about secretly building up its nuclear arsenal, and to encourage other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about their arsenals.

Importantly, the U.S. also disclosed the number of warheads dismantled each year back to 1994. This disclosure helped document that the United States was not hiding retired weapons but actually dismantling them. In 2014, the United States even declassified the total inventory of retired warheads still awaiting dismantlement at that time: 2,500.

The 2010 release built on previous disclosures, most importantly the Department of Energy’s declassification decisions in 1996, which included – among other issues – a table of nuclear weapons stockpile data with information about stockpile numbers, megatonnage, builds, retirements, and disassemblies between 1945 and 1994. Unfortunately, the web site is poorly maintained and the original page headlined “Declassification of Certain Characteristics of the United States Nuclear Weapon Stockpile” no longer has tables, another page is corrupted, but the raw data is still available here. Clearly, DOE should fix the site.

The decision in 2010 to disclose the size of the stockpile and the dismantlement numbers did not mean the numbers would necessarily be updated each subsequent year. Each year was a separate declassification decision that was announced on the DOD Open Government web site. The most recent decision from 2018 in response to a request from FAS showed the stockpile number as of September 2017: 3,822 stockpiled warheads and 354 dismantled warheads.

The 2017 number was extra good news because it showed the Trump administration, despite bombastic rhetoric from the president, had continued to reduce the size of the stockpile (see my analysis from 2018).

Since 2010, Britain and France have both followed the U.S. example by providing additional information about the size of their arsenals, although they have yet to disclose the entire history of their warhead inventories. Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea have not yet provided information about the size or history of their arsenals.

FAS’ Role In Providing Nuclear Transparency

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has been tracking nuclear arsenals for many years, previously in collaboration with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). The 5,113-warhead stockpile number declassified by the Obama administration in 2010 was only 13 warheads off the FAS/NRDC estimate at the time.

We provide these estimates on our web site, on our Strategic Security Blog, and in publications such as the bi-monthly Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and the annual nuclear forces chapter in the SIPRI Yearbook. The work is used extensively by journalists, NGOs, scholars, parliamentarians, and government officials.

With the Pentagon decision to close the books on the stockpile, and the rampant nuclear modernization underway worldwide, the role of FAS and others in documenting the status of nuclear forces will be even more important.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Pentagon’s decision not to disclose the 2018 nuclear weapons stockpiled and dismantled warhead numbers is unnecessary and counterproductive.

The United States or its allies are not suffering or at a disadvantage because the nuclear stockpile numbers are in the public. Indeed, there seems to be no rational national security factor that justifies the decision to reinstate nuclear stockpile secrecy.

The decision walks back nearly a decade of U.S. nuclear weapons transparency policy – in fact, longer if including stockpile transparency initiatives in the late-1990s – and places the United States is the same box as over-secretive nuclear-armed states, several of which are U.S. adversaries.

The decision also puts the United States in an even more disadvantageous position for next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) review conference where the administration will be unable to report progress on meeting its Article VI obligations. Instead, this decision, as well as decisions to withdraw from the INF treaty, start producing new nuclear weapons, and the absence of nuclear arms control negotiations, needlessly open up the United States to criticism from other Parties to the NPT – a treaty the United States needs to protect and strengthen to curtail nuclear proliferation.

The decision also puts U.S. allies like Britain and France in the awkward position of having to reconsider their nuclear transparency policies as well or be seen to be out of sync with their largest military ally at a time of increased East-West hostilities.

With this decision, the Trump administration surrenders any pressure on other nuclear-armed states to be more transparent about the size of their nuclear weapon stockpiles. This is curious since the Trump administration had repeatedly complained about secrecy in the Russian and Chinese arsenals. Instead, it now appears to endorse their secrecy.

The decision will undoubtedly fuel suspicion and worst-case mindsets in adversarial countries. Russia will now likely argue that not only has the United States obscured conversion of nuclear launchers under the New START treaty, it has now decided also to keep secret the number of nuclear warheads it has available for them.

Finally, the decision also makes it harder to envision achieving new arms control agreements with Russia and China to curtail their nuclear arsenals. After all, if the United States is not willing to maintain transparency of its warhead inventory, why should they disclose theirs?

It is yet unclear why the decision not to disclose the 2018 stockpile number was made. There are several possibilities:

- Is it because the chaos and incompetence in the Trump administration have enabled hardliners and secrecy zealots to reverse a policy they disagreed with anyway?

- Is it a result of the Nuclear Posture Review’s embrace of Great Power Competition with Cold War-like instincts to increase reliance on nuclear weapons, kill arms control treaties, increase secrecy, and scuttle policies that some say appease adversaries?

- Is it because of a Trump administration mindset opposing anything created by president Obama?

- Or is it because the United States has secretly begun to increase the size of its nuclear stockpile? (I don’t think so; the stockpile appears to have continued to decrease to now at or just below 3,800 warheads.)

The answer may be as simple as “because it can” with no opposition from the White House. Whatever the reason, the decision to reinstate stockpile secrecy caps a startling and rapid transformation of U.S. nuclear policy. Within just a little over two years, the United States under the chaotic and disastrous policies of the Trump administration has gone from promoting nuclear transparency, arms control, and nuclear constraint to increasing nuclear secrecy, abandoning arms control agreements, producing new nuclear weapons, and increasing reliance on such weapons in the name of Great Power Competition.

This is a historic policy reversal by any standard and one that demands the utmost effort on the part of Congress and the 2020 presidential election candidates to prevent the United States from essentially going nuclear rogue but return it to a more constructive nuclear weapons policy.

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Despite Obfuscations, New START Data Shows Continued Value Of Treaty

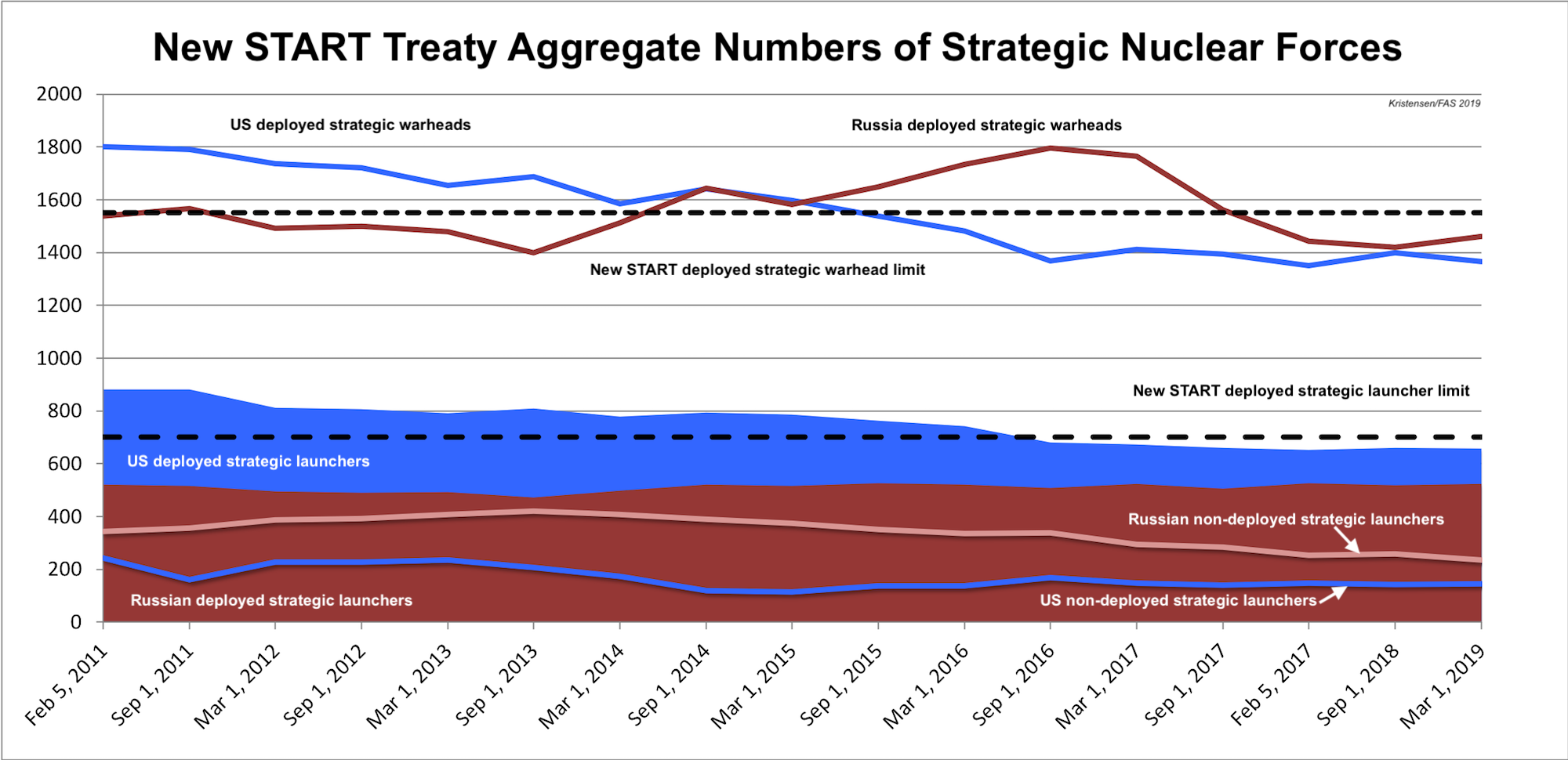

The latest set of New START treaty aggregate data released by the US State Department shows Russia and the United States continue to abide by the limitations of the New START treaty. The data shows that Russia and the United States combined have cut a total of 429 strategic launchers since February 2011, reduced the number of deployed launchers by 223, and reduced the number of warheads attributed to those launchers by 511.

The good news comes despite efforts by officials in Moscow and Washington to create doubts about the value of New START by complaining about lack of irreversibility, weapon systems not covered by the treaty, or other unrelated treaty compliance and behavioral matters. These complaints are part of the ongoing bickering between Russia and the United States and appear intended – they certainly have that effect – to create doubt about the value of extending New START for five years beyond 2021.

Playing politics with New START is irresponsible and counterproductive. While the treaty has facilitated coordinated and verifiable reductions and provides for on-site inspections and a continuous exchange of notifications about strategic offensive nuclear forces, the remaining arsenals are large, undergoing extensive modernizations, and demand continued limits and verification.

By the Numbers

The latest New START data shows that the United States and Russia combined, as of March 1st, 2019, deployed a total of 1,180 strategic launchers (long-range ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) with a total of 2,826 warheads attributed to them (see chart below). These two arsenals constitute more strategic launchers and warheads than all the world’s other seven nuclear-armed states possess combined.

For Russia, the data shows 524 deployed strategic launchers with 1,461 warheads. That’s a slight increase of 7 launchers and 41 warheads compared with September 2018. Russia is currently 176 launchers and 89 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

The United States deploys 656 strategic launchers with 1,365 warheads attributed to them, or a slight decrease of 3 launchers and 33 warheads compared with September 2018. The United States is currently 44 launchers and 185 warheads below the treaty limit for deployed strategic weapons.

These increases and decreases since September 2018 are normal fluctuations in the arsenals due to maintenance and upgrades and do not reflect an increase or decrease of the threat level.

It is important to remind, that the Russian and US nuclear forces reported under New START are only a portion of their total stockpiles of nuclear weapons, currently estimated at 4,350 for Russia and 3,800 for the United States (6,850 and 6,460, respectively, if also counting retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Build-Up, What Build-Up

Despite frequent claims by some about a Russian nuclear “buildup,” the New START data does not show such a development. On the contrary, it shows that Russia’s strategic offensive nuclear force level – despite ongoing modernization – is relatively steady. Deteriorating relations have so far not caused Russia (or the United States) to increase strategic force levels or slowed down the reductions required by New START. On the contrary, both sides seem to be continuing to structure their central strategic nuclear forces in accordance with the treaty’s limitations and intentions.

That said, both countries are working on modifications to their strategic nuclear arsenals. Russia has been working for a long time – even before New START was signed – to develop exotic intercontinental-range weapons to overcome US ballistic missile defense systems. These exotic weapons, which are not deployed or covered by the treaty, include a ground-launched nuclear-powered cruise missile (Burevestnik) and a submarine-launched torpedo-like drone (Poseidon). An ICBM-launched glide-vehicle commonly known as Avangard is close to initial deployment but would likely supplement the current ICBM force rather than increasing it. The new weapons are limited in numbers and insufficient to change the overall strategic balance or challenge extension of New START. The treaty provides for adding new weapon types if agreed by the two parties, although neither side has formally proposed to do so.

Russia is not at an advantage in terms of overall strategic nuclear forces, nor does it appear to try to close the significant gap the New START data shows exists in the number of strategic launchers – 132 in US favor by the latest count. To put things in perspective, 132 launchers is nearly the equivalent of a US ICBM wing, more than six Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines, or twice the size of the entire US nuclear bomber fleet. If the tables were turned, US officials and hardliners would be screaming about a disadvantage. Astoundingly, some are still trying to make that case despite the US advantage. Given the launcher asymmetry, one could also suspect that Russia might seek to retain more non-deployed launchers for potential redeployment to be able to rapidly increase the force if necessary. Instead, the New START data shows that Russia has continued to decrease its non-deployed launchers by 185 since the peak of 421 in 2013.

Russian strategic modernization has been slower than expected with delays and less elaborate base upgrades and is stymied by a weak economy and corruption in government and defense industry. Russia is compensating for this asymmetry by maximizing warhead loadings on its new missiles, but the New START data indicates that Russia since 2016 has been forced to reduce the normal warhead loading on some of its ballistic missiles in order to meet the treaty limit for deployed warheads. This demonstrates New START has a real constraining effect on Russian strategic forces.

Having said that, Russia could – like the United States – upload large numbers of non-deployed nuclear warheads onto deployed launchers if a decision was made to break out of the New START limits. Those launchers would include initially bombers, then sea-launched ballistic missiles, and in the longer term the ICBMs.

The United States has dismantled and converted more launchers than Russia because the United States had more of them when the treaty was signed, not because Washington was handed a “bad deal,’ as some defense hardliners have claimed. But Russia has complained – including in an unprecedented letter to the US Congress – that it is unable to verify that launchers converted by the US can’t be returned to nuclear use. The New START treaty does not require irreversibility and the US insists conversions have been carried out as required by the treaty rules that Russia agreed to. Discussions continue in Bilateral Consultative Committee (BCC).

Verification and Notifications

Although not included in the formal aggregate data, the State Department has also disclosed the total number of inspections and notifications conducted under the treaty. Since February 2011, this has included 294 onsite inspections (3 each since September) and 17,516 notifications (up about 1,100 since September 2018). This data flow is essential to providing confidence and reassurance that the strategic force level of the other side indeed is what they say it is. It also provides each side invaluable insight into structural and operational matters that complements and expands what is possible to ascertain with national technical means.

US SSBN in drydock. Russia says it cannot verify conversion of US strategic launchers. Click on image to see full size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although bureaucrats and Cold Warriors in both Washington and Moscow currently are busy raising complaints and uncertainties about the New START treaty, there is no way around the basic fact: the treaty is strongly in the national security interest of both countries – as well as that of their allies.

But the treaty expires in February 2021 and the two sides could – if their leadership was willing to act – extend it with the stroke of a pen.

Unfortunately, Russian claims that it is incapable of confirming US conversion of strategic launchers, US complaints that new exotic Russian weapons circumvent the treaty, Russia’s violation and the US decision to withdraw from the INF treaty, as well as the growing political animosity and bickering between East and West, have combined to increase the pressure on New START and put extension in doubt.

The idea that the INF debacle somehow requires a reevaluation of the value of New START is ridiculous. INF regulates regional land-based missiles whereas New START regulates the core strategic nuclear forces. Why would anyone in either country in their right mind jeopardize limits and verification of strategic forces that threaten the survival of the nation over a disagreement about regional forces that cannot? That seems to be the epidemy of irresponsible behavior.

And the disagreements about conversion of launchers and need to add new intercontinental forces to the treaty can and should be resolved within the BCC.

But it all captures well the danger of Cold War mindsets where nationalistic bravado and chest-thumping override deliberate rational strategy for the benefit of national and international security. Bad times are not an excuse for sacrificing treaties but reminders of the importance of preserving them. Arms limitation treaties are not made with friends (you don’t have to) but with potential adversaries in order to limit their offensive nuclear forces and increase transparency and verification. If officials focus on complaining and listing problems, well guess what, that’s what we’re going to get.

Additional information:

This publication was made possible by generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Nuclear Upgrades At Russian Bomber Base And Storage Site

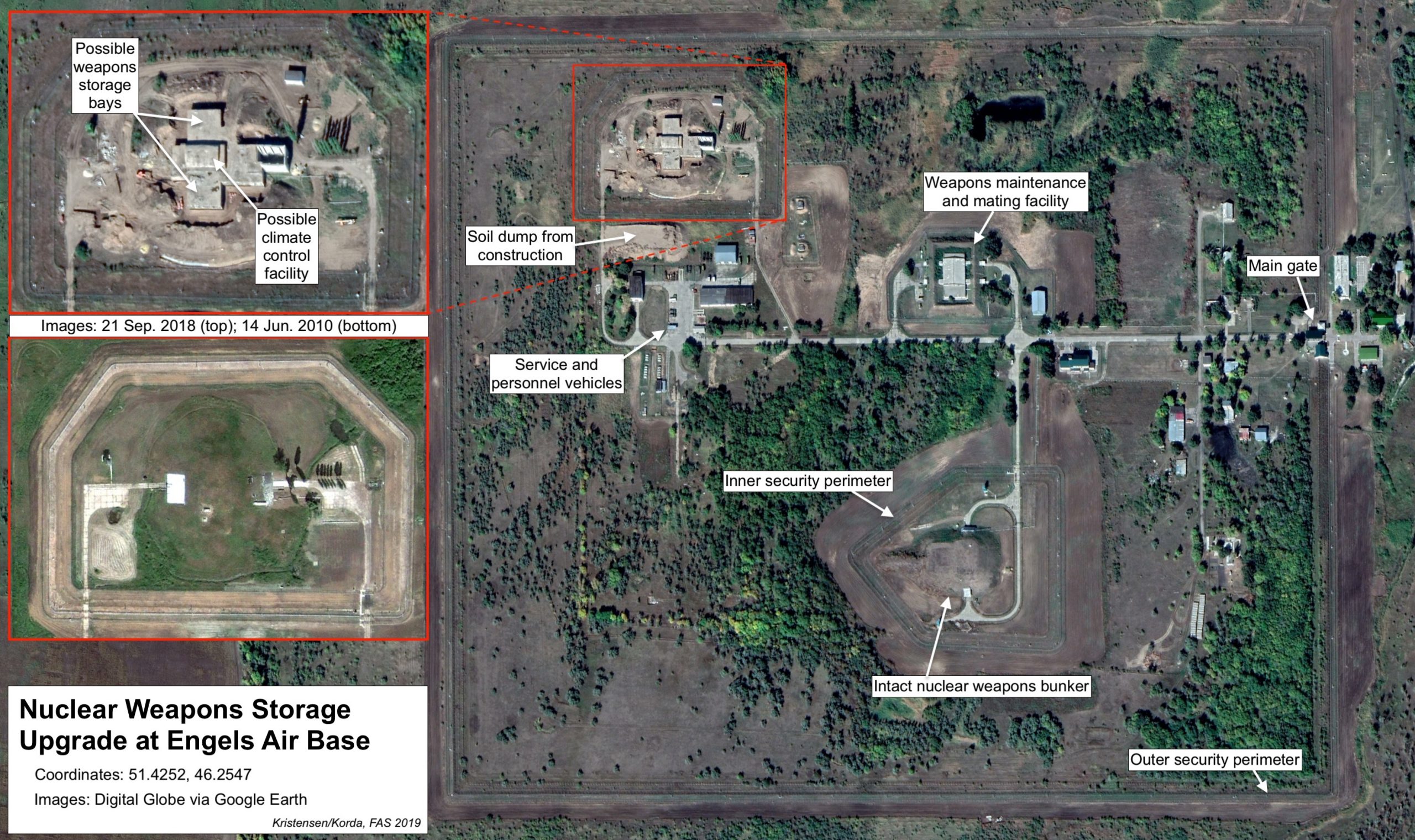

The Russian military has started upgrading nuclear weapons bunkers at Engels Air Base and the Saratov-63 central nuclear weapons storage facility in Saratov province.

At Engels Air Base, satellite images show one of two bunkers in the weapons storage area has been exposed as part of apparent maintenance of the base’s nuclear weapons mission.

The bunker is one of two earth-covered concrete bunkers at the base, which is home to Russian Tu-160 (Blackjack) and Tu-95 (Bear) long-range bombers. Engels Air Base made international headlines recently when two Tu-160s were deployed from the base to Venezuela in December, as part of the intensifying standoff between the Trump and Maduro governments. Although the bombers themselves are nuclear-capable and are collocated with nuclear weapons bunkers in Russia, it’s a certainty that the two planes deployed to Venezuela carried no such weapons.

The bunker is located about seven kilometers (4.3 miles) south of the runway. The bombers, which are accountable under the New START treaty, can carry nuclear AS-15 (Kh-55) long-range cruise missiles and are being upgraded to carry the new nuclear AS-23B (Kh-102) long-range cruise missile. Each cruise missile is thought to carry a 200-kiloton nuclear warhead. The bombers are also equipped to carry conventional Kh-555 and Kh-101 cruise missiles.

Initial work on the bunker appears to have started in 2011 with addition of a tall structure at the eastern entrance. But the work apparently stalled – potentially because of lack of funds – until late-May 2018 when excavation of the bunker itself began. Between 2011 and 2018, the bunker seemed dormant. The second bunker, however, is intact and appears to have been active during this time.

The size of the exposed bunker is approximately 1,800 square meters (19,800 square feet). It consists of two entrances, a main hall for loading, a climate control facility, and what are probably two warhead storage bays. Each bay is about 20×20 meters (60×60 feet), or 400 square meters (1,200 square feet). It is unknown if warheads are stored in shipping containers or mated with the missiles. If mated with missiles, each bay could potentially store 40 missiles for a total capacity of 80 missiles per bunker, or 160 missiles combined in the two bunkers. If warheads are stored in containers, the capacity would be significantly greater.

Bunker Upgrade at Saratov-63

Like the United States, Russia is thought to store only some of its bomber weapons at the bomber bases while most are kept in central storage facilities. Russia has about a dozen central storage facilities, which are managed by the 12th Main Directorate (GUMO) of the Ministry of Defence. One of them is Saratov-63, located near Berezovka—only 36 kilometers (22 miles) south of Engels. One of the five large underground bunkers at this facility is also being upgraded.

The bunker at Saratov-63 is much larger than the one at Engels and covers an area of roughly 5,300 square meters (57,600 square feet). A lot of that consists of access tunnels and technical areas while the core structure covers approximately 3,500 square meters (38,500 square feet). The bunker can probably hold several hundred nuclear weapons.

Saratov-63 has a special history. In June 1998, former US STRATCOM commander General Gene Habiger visited the facility and was given access to one of the bunkers. He later described the interior:

“We went to Saratov, a national nuclear weapons storage site, where I saw not only strategic weapons, but tactical weapons…And they took me into the side of a mountain, a hill, where we went behind two doors that were each several thousands of tons in weight. And you had to open up one door at a time, these sliding, massive doors, in order to get into the inner sanctum. In the inner sanctum, there were five nuclear weapon storage bays. They took me into one of those bays, and we had an interesting discussion.”

“We went to Saratov, a national nuclear weapons storage site, where I saw not only strategic weapons, but tactical weapons…And they took me into the side of a mountain, a hill, where we went behind two doors that were each several thousands of tons in weight. And you had to open up one door at a time, these sliding, massive doors, in order to get into the inner sanctum. In the inner sanctum, there were five nuclear weapon storage bays. They took me into one of those bays, and we had an interesting discussion.”

The upgrade of nuclear storage bunkers at Engels and Saratov-63 follow upgrades to nuclear bunkers we have described at Kulikovo in the Kaliningrad province and at Vilyuchinsk on the Kamchatka peninsula.

These infrastructure upgrades are part of Russia’s overall nuclear modernization efforts. Both facilities serve central roles in Russia’s nuclear posture, so it’s no surprise that they are being upgraded. Engels Air Base also recently completed major upgrades of runway and tarmac and remains the only Russian air base serving the Air Force’s fleet of Tu-160 strategic bombers (at least 10 are scheduled to complete modernization by the end of 2019).

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, and the Prospect Hill Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Chinese DF-26 Missile Launchers Deploy To New Missile Training Area

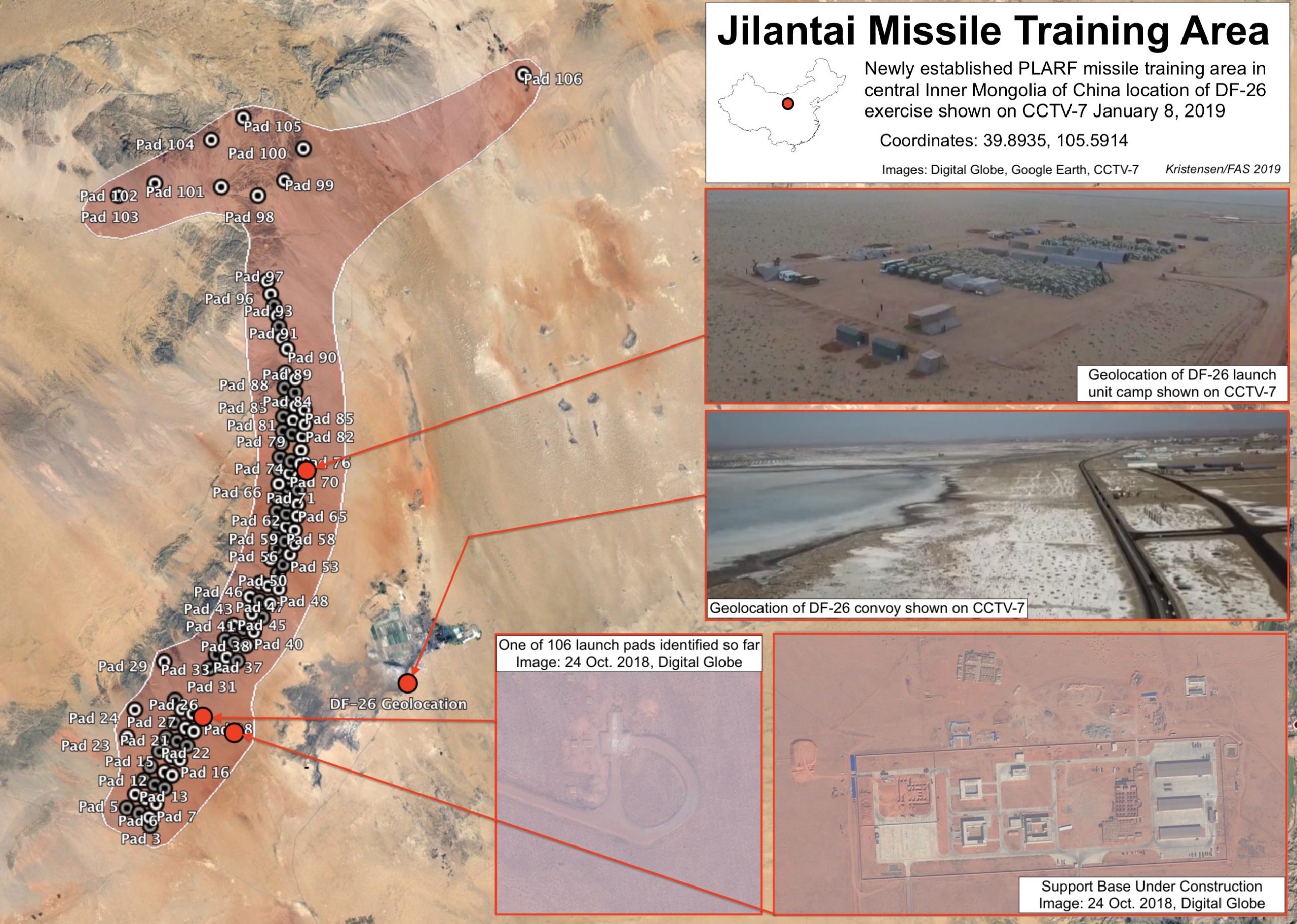

[Updated Jan 31, 2019] Earlier this month, the Chinese government outlet Global Times published a report that a People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) unit with the new DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile had carried out an exercise in the “Northwest China’s plateau and desert areas.” The article made vague references to a program previously aired on China’s CCTV-7 that showed a column of DF-26 launchers and support vehicles driving on highways, desert roads, and through mountain streams.

As it turns out, the exercise may have been west of Beijing, but the actual location is in upper Central China. Several researchers (for example Sean O’Connor) have been attempting to learn more about the unit. By combining scenes from the CCTV-7 program with various satellite imagery sources, I was able to geolocate the DF-26s to the S218 highway (39.702137º, 105.731469º) outside the city of Jilantai (Jilantaizhen) roughly 100 km north of Alxa in the Inner Mogolia province in the northern part of central China (see image below).

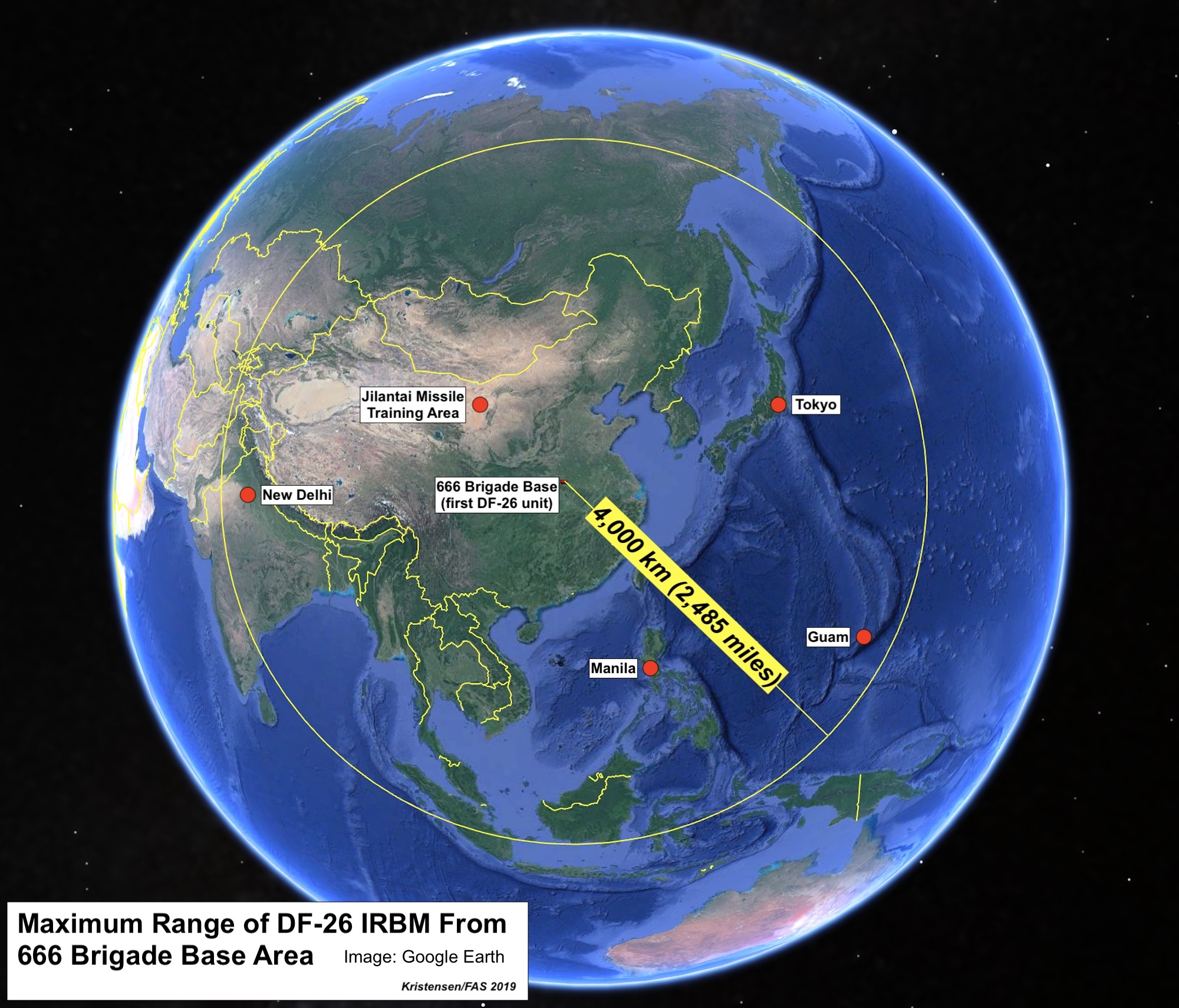

The DF-26s appear to have been visiting a new missile training area established by PLARF since 2015. By combining use of Google Earth, Planet, and Terra Server, each of which has unique capabilities needed to scan vast areas and identifying individual facilities, as well as analyzing images purchased from Digital Globe, I have so far been able to identify more than 100 launch pads used by launchers and support vehicles during exercises, a support base, a landing strip, and at least eight launch unit camp sites covering an area of more than 1,000 square kilometers (400 square miles) along a 90-kilometer (55-mile) corridor (see image below). A Google Earth placemark file (kml) with all these locations is available for download here.

The Chinese military has for decades been operating a vast missile training area further west in the Qinghai province, which I profiled in an article a decade ago. They also appear to operate a training area further west near Korla (Beyingol). The best unclassified guide for following Chinese missile units is, of course, the indispensable PLA Rocket Force Leadership and Unit Reference produced by Mark Stokes at the Project 2049 Institute.

It is not clear if the DF-26 unit that exercised in the Jilantai training area is or will be permanently based in the region. It is normal for Chinese missile units to deploy long distances from their home base for training. The first brigade (666 Brigade) is thought to be based some 1,100 kilometers (700 miles) to the southeast near Xinyang in southern Henan province. This was not the first training deployment of the brigade. The NASIC reported in 2017 that China had 16+ DF-26 launchers and it is building more. The CCTV-7 video shows an aerial view of a launch unit camp with TEL tents, support vehicles, and personnel tents. A DF-26 is shown pulling out from under a camouflage tent and setting up on a T-shaped concrete launch pad (see image below). More than 100 of those pads have been identified in the area.

The support base at the training area does not have the outline of a permanent missile brigade base. But several satellite images appear to show the presence of DF-16, DF-21, and DF-26 launchers at this facility. One image purchased from Digital Globe and taken by one of their satellites on October 24, 2018, shows the base under construction with what appears to be two DF-16 launchers (h/t @reutersanders) parked between two garages. Another photo taken on August 16, 2017, shows what appears to be 22 DF-21C launchers with a couple of possible DF-26 launchers as well (see below).

The DF-26, which was first officially displayed in 2015, fielded in 2016, and declared in service by April 2018, is an intermediate-range ballistic missile launched from a six-axle road-mobile launchers that can deliver either a conventional or nuclear warhead to a maximum distance of 4,000 kilometers (2,485 miles). From the 666 Brigade area near Xinyang, a DF-26 IRBM could reach Guam and New Delhi (see map below). China has had the capability to strike Guam with the nuclear DF-4 ICBM since 1980, but the DF-4 is a moveable, liquid-fuel missiles that takes a long time to set up, while the DF-26 is a road-mobile, solid-fuel, dual-capable missile that can launch quicker and with greater accuracy. Moreover, DF-26 adds conventional strike to the IRBM range for the first time.

The 666 Brigade is in range of U.S. sea- and air-launched cruise missiles as well as ballistic missiles. But the DF-26 is part of China’s growing inventory of INF-range missiles (most of which, by far, are non-nuclear), a development that is causing some in the U.S. defense community to recommend the United States should withdraw from the INF treaty and deploy quick-launch intermediate-range ballistic missiles in the Western Pacific. Others (including this author) disagree, saying current and planned U.S. capabilities are sufficient to meet national security objectives and that engaging China in an INF-race would make things worse.

See also: FAS Nuclear Notebook on Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2018

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Mixed Messages On Trump’s Missile Defense Review

President Trump personally released the long-overdue Missile Defense Review (MDR) today, and despite the document’s assertion that “Missile Defenses are Stabilizing,” the MDR promotes a posture that is anything but.

Firstly, during his presentation, Acting Defense Secretary Shanahan falsely asserted that the MDR is consistent with the priorities of the 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS). The NSS’ missile defense section notes that “Enhanced missile defense is not intended to undermine strategic stability or disrupt longstanding strategic relationships with Russia or China.” (p.8) During Shanahan’s and President Trump’s speeches, however, they made it clear that the United States will seek to detect and destroy “any type of target,” “anywhere, anytime, anyplace,” either “before or after launch.” Coupled with numerous references to Russia’s and China’s evolving missile arsenals and advancements in hypersonic technology, this kind of rhetoric is wholly inconsistent with the MDR’s description of missile defense being directed solely against “rogue states.” It is also inconsistent with the more measured language of the National Security Strategy.

Secondly, the MDR clearly states that the United States “will not accept any limitation or constraint on the development or deployment of missile defense capabilities needed to protect the homeland against rogue missile threats.” This is precisely what concerns Russia and China, who fear a future in which unconstrained and technologically advanced US missile defenses will eventually be capable of disrupting their strategic retaliatory capability and could be used to support an offensive war-fighting posture.

Thirdly, in a move that will only exacerbate these fears, the MDR commits the Missile Defense Agency to test the SM-3 Block IIA against an ICBM-class target in 2020. The 2018 NDAA had previously mandated that such a test only take place “if technologically feasible;” it now seems that there is sufficient confidence for the test to take place. However, it is notable that the decision to conduct such a test seems to hinge upon technological capacity and not the changes to the security environment, despite the constraints that Iran (which the SM-3 is supposedly designed to counter) has accepted upon its nuclear and ballistic missile programs.

Fourthly, the MDR indicates that the United States will look into developing and fielding a variety of new capabilities for detecting and intercepting missiles either immediately before or after launch, including:

- Developing a defensive layer of space-based sensors (and potentially interceptors) to assist with launch detection and boost-phase intercept.

- Developing a new or modified interceptor for the F-35 that is capable of shooting down missiles in their boost-phase.

- Mounting a laser on a drone in order to destroy missiles in their boost-phase. DoD has apparently already begun developing a “Low-Power Laser Demonstrator” to assist with this mission.

There exists much hype around the concept of boost-phase intercept—shooting down an adversary missile immediately after launch—because of the missile’s relatively slower velocity and lack of deployable countermeasures at that early stage of the flight. However, an attempt at boost-phase intercept would essentially require advance notice of a missile launch in order to position US interceptors within striking distance. The layer of space-based sensors is presumably intended to alleviate this concern; however, as Laura Grego notes, these sensors would be “easily overwhelmed, easily attacked, and enormously expensive.”

Additionally, boost-phase intercept would require US interceptors to be placed in very close proximity to the target––almost certainly revealing itself to an adversary’s radar network. The interceptor itself would also have to be fast enough to chase down an accelerating missile, which is technologically improbable, even years down the line. A 2012 National Academy of Sciences report puts it very plainly: “Boost-phase missile defense—whether kinetic or directed energy, and whether based on land, sea, air, or in space—is not practical or feasible.”

Overall, the Trump Administration’s Missile Defense Review offers up a gamut of expensive, ineffective, and destabilizing solutions to problems that missile defense simply cannot solve. The scope of US missile defense should be limited to dealing with errant threats—such as an accidental or limited missile launch—and should not be intended to support a broader war-fighting posture. To that end, the MDR’s argument that “the United States will not accept any limitation or constraint” on its missile defense capabilities will only serve to raise tensions, further stimulate adversarial efforts to outmaneuver or outpace missile defenses, and undermine strategic stability.

During the upcoming spring hearings, Congress will have an important role to play in determining which capabilities are actually necessary in order to enforce a limited missile defense posture, and which ones are superfluous. And for those superfluous capabilities, there should be very strong pushback.

Report of the International Study Group on North Korea Policy

The FAS International Study Group on North Korea Policy convened to develop a strategy toward a North Korea that will in all likelihood remain nuclear-armed and under the control of the Kim family for the next two decades. The composition of the group reflects a conviction that a sustainable and realistic strategy must draw on the expertise of new voices from a broader range of disciplines coordinating across national boundaries—and cannot be met by replicating outdated assumptions and methods. In the pages that follow, the study group issues recommendations to the United States and its allies—most directly South Korea and Japan, but also to countries in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Oceania who hold broadly shared objectives even as they prioritize issues of specific national concern.

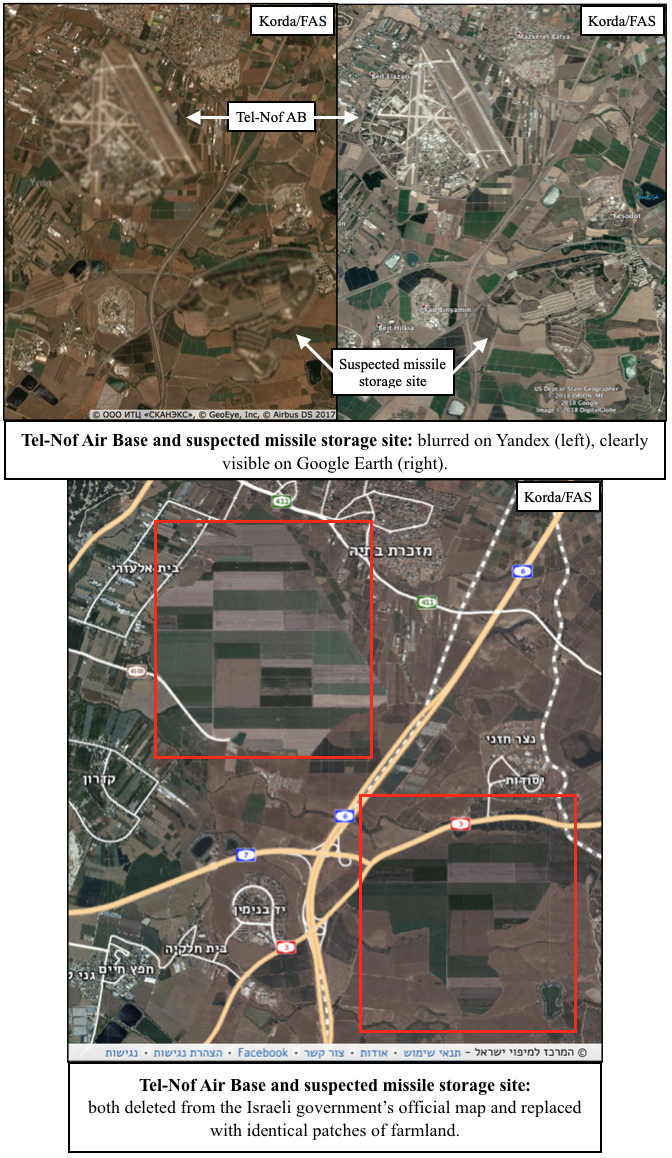

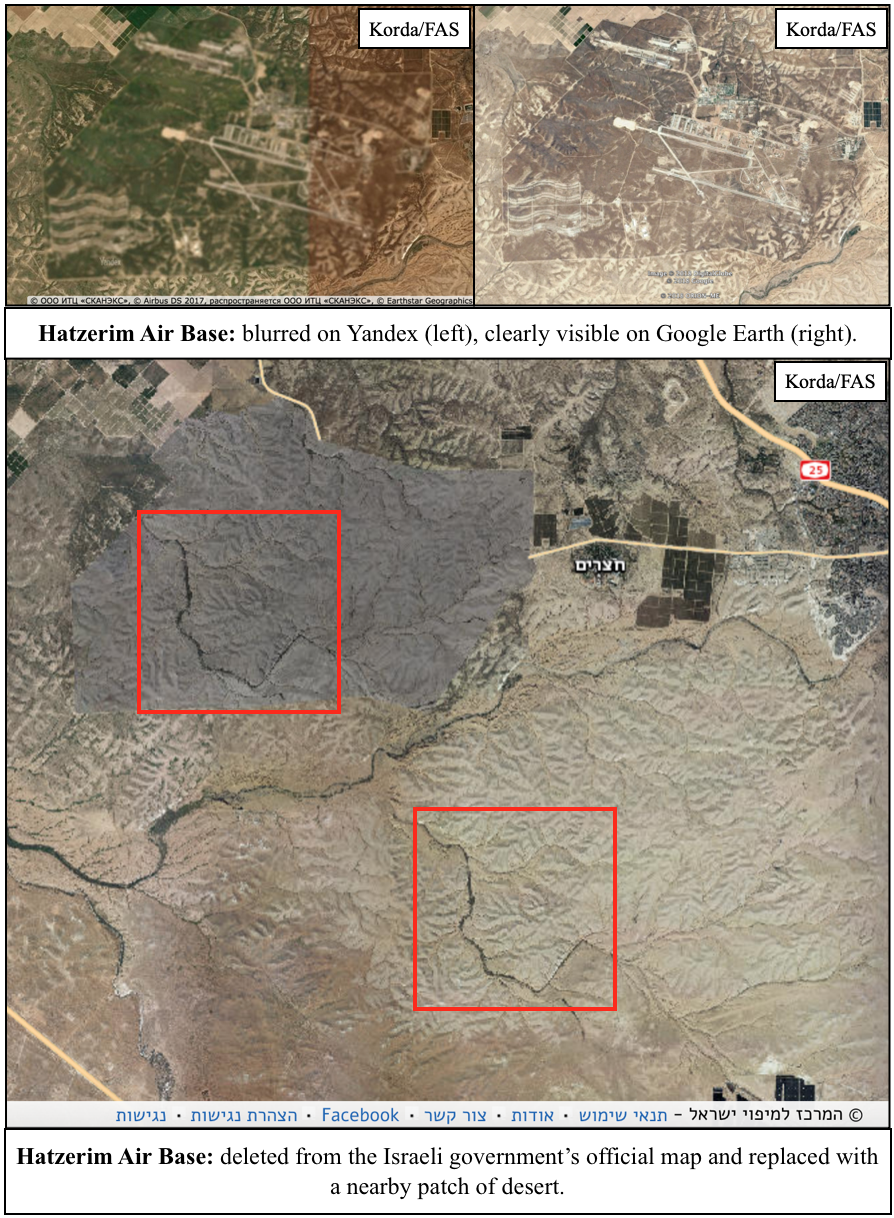

Israel’s Official Map Replaces Military Bases with Fake Farms and Deserts

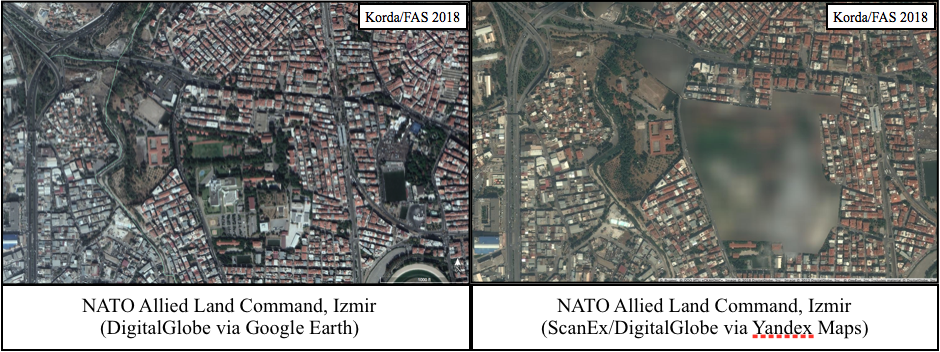

Somewhat unexpectedly, a blog post that I wrote last week caught fire internationally. On Monday, I reported that Yandex Maps—Russia’s equivalent to Google Maps—had inadvertently revealed over 300 military and political facilities in Turkey and Israel by attempting to blur them out.

In a strange turn of events, the fallout from that story has actually produced a whole new one.

After the story blew up, Yandex pointed out that its efforts to obscure these sites are consistent with its requirement to comply with local regulations. Yandex’s statement also notes that “our mapping product in Israel conforms to the national public map published by the government of Israel as it pertains to the blurring of military assets and locations.”

The “national public map” to which Yandex refers is the official online map of Israel which is maintained by the Israeli Mapping Centre (מרכז למיפוי ישראל) within the Israeli government. Since Yandex claims to take its cue from this map, I wondered whether that meant that the Israeli government was also selectively obscuring sites on its national map.

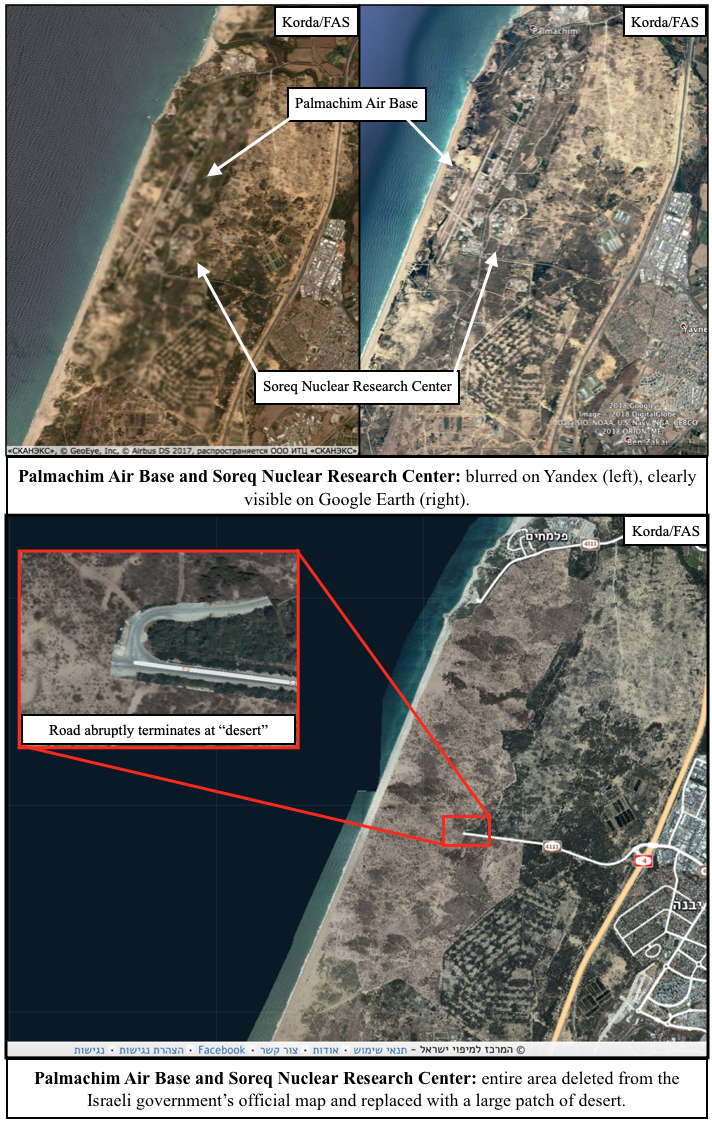

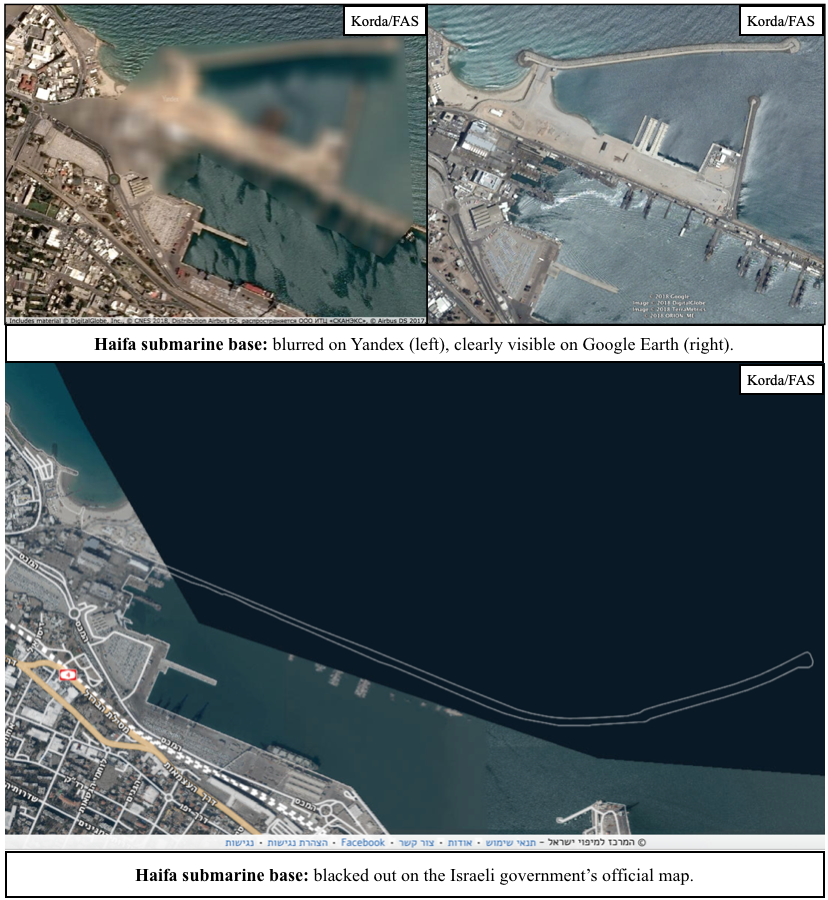

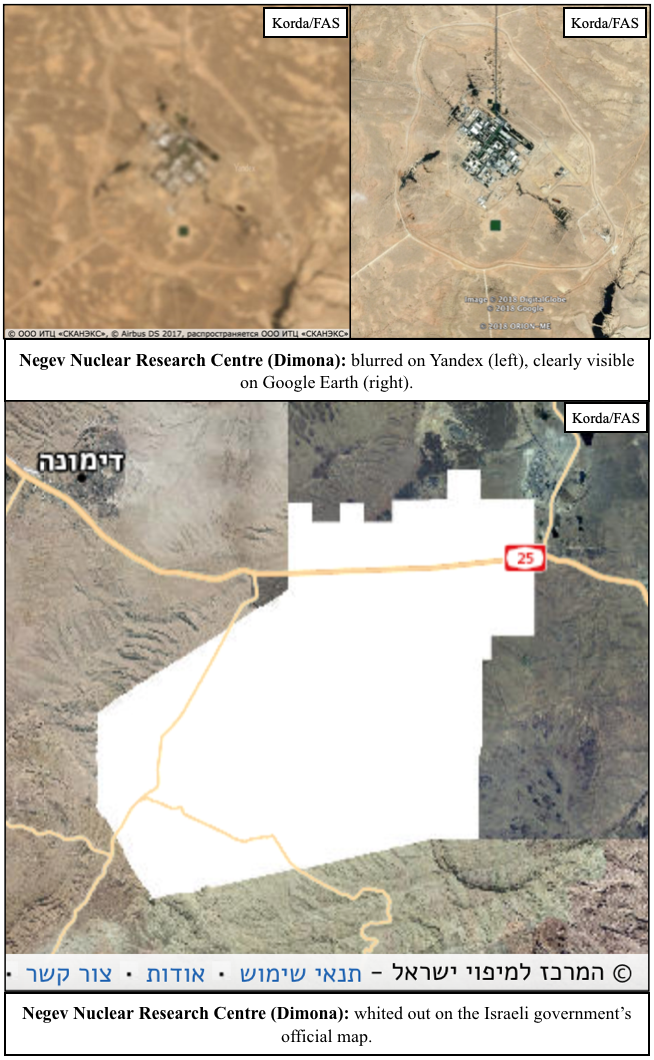

I wasn’t wrong. In fact, the Israeli government goes well beyond just blurring things out. They’re actually deleting entire facilities from the map—and quite messily, at that. Usually, these sites are replaced with patches of fake farmland or desert, but sometimes they’re simply painted over with white or black splotches.

Some of the more obvious examples of Israeli censorship include nuclear facilities:

- Tel-Nof Air Base is just down the road from a suspected missile storage site, both of which have been painted over with identical patches of farmland.

- Palmachim Air Base doubles as a test launch site for Jericho missiles and is collocated with the Soreq Nuclear Research Center, which is rumoured to be responsible for nuclear weapons research and design. The entire area has been replaced with a fake desert.

- The Haifa Naval Base includes pens for submarines that are rumoured to be nuclear-capable, and is entirely blacked out on the official map.

- The Negev Nuclear Research Center at Dimona is responsible for plutonium and tritium production for Israel’s nuclear weapons program, and has been entirely whited out on the official map.

- Hatzerim Air Base has no known connection to Israel’s nuclear weapons program; however, the sloppy method that was used to mask its existence (by basically just copy-pasting a highly-distinctive and differently-coloured patch of desert to an area only five kilometres away) was too good to leave out.

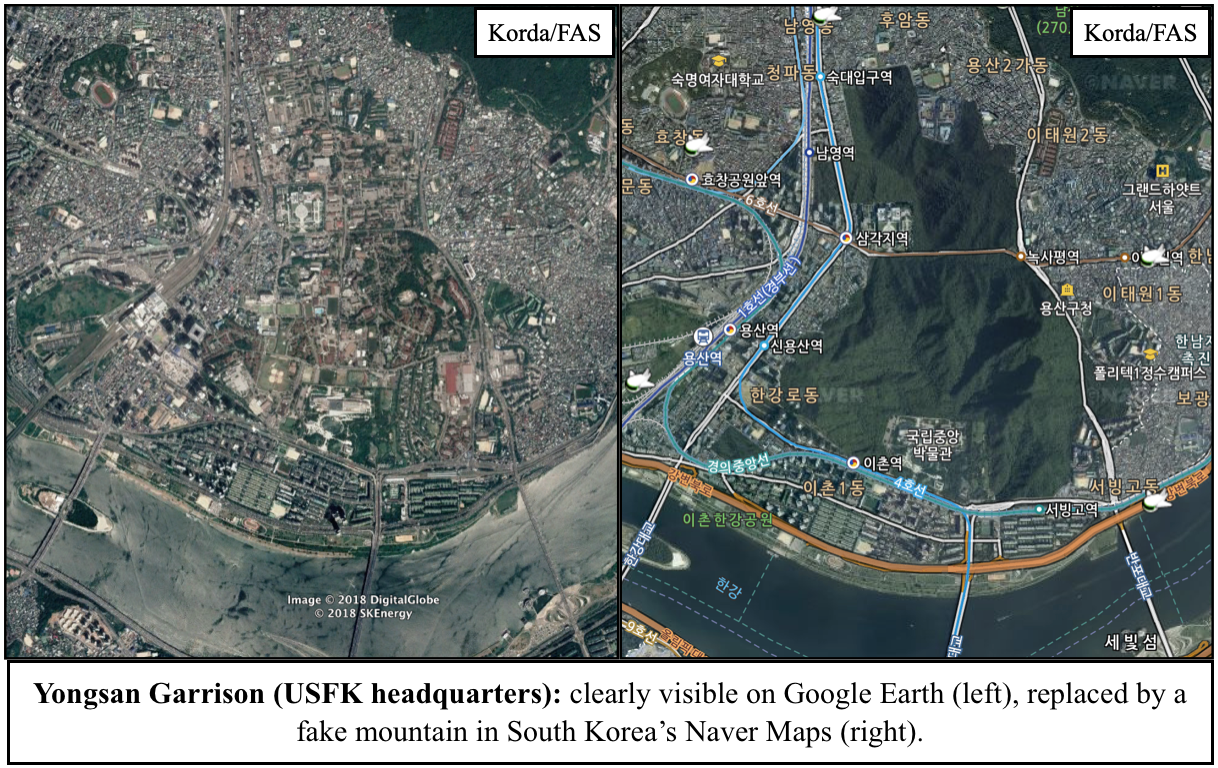

Given that all of these locations are easily visible through Google Earth and other mapping platforms, Israel’s official map is a prime example of needless censorship. But Israel isn’t the only one guilty of silly secrecy: South Korea’s Naver Maps regularly paints over sensitive sites with fake mountains or digital trees, and in a particularly egregious case, the Belgian Ministry of Defense is actually suing Google for not complying with its requests to blur out its military facilities.

Before the proliferation of high-resolution satellite imagery, obscuring aerial photos of military facilities was certainly an effective method for states to safeguard their sensitive data. However, now that anyone with an internet connection can freely access these images, it simply makes no sense to persist with these unnecessary censorship practices–especially since these methods can often backfire and draw attention to the exact sites that they’re supposed to be hiding.

Case studies like Yandex and Strava—in which the locations of secret military facilities were revealed through the publication of fitness heat-maps—should prompt governments to recognize that their data is becoming increasingly accessible through open-source methods. Correspondingly, they should take the relevant steps to secure information that is absolutely critical to national security, and be much more publicly transparent with information that is not—hopefully doing away with needless censorship in the process.

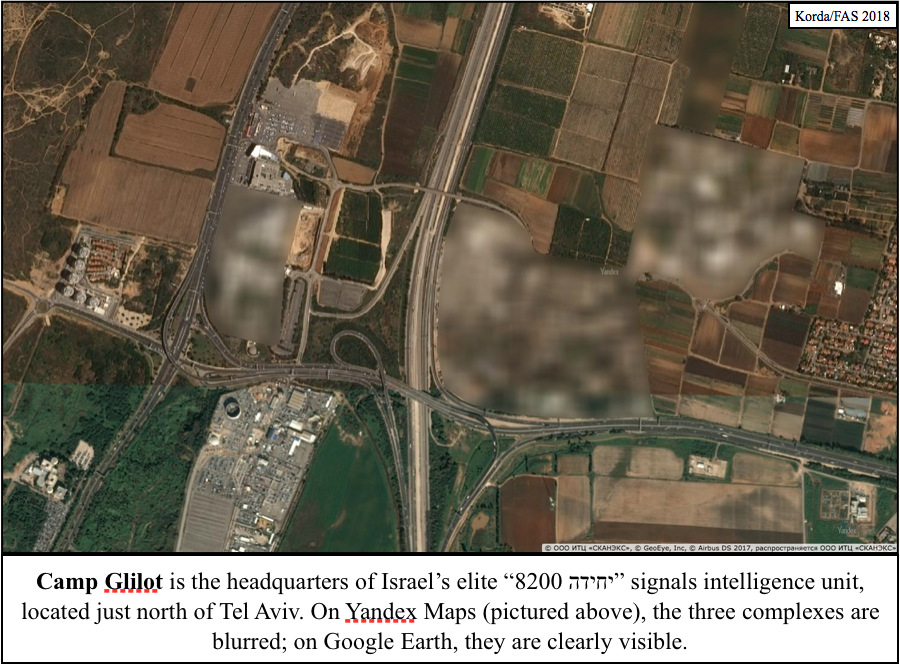

Widespread Blurring of Satellite Images Reveals Secret Facilities

Want to know how to make a satellite imagery analyst instantly curious about something?

Blur it out.

Google Earth occasionally does this at the request of governments that want to keep prying eyes away from some of their more sensitive military or political sites. France, for example, has asked Google to obscure all imagery of its prisons after a French gangster successfully conducted a Hollywood-inspired jailbreak involving drones, smoke bombs, and a stolen helicopter(!)—and Google has agreed to comply by the end of 2018. In similar fashion, an old Dutch law requires Dutch companies to blur their satellite images of military and royal facilities—even to the point where a satellite imagery provider once doctored an image of Volkel Air Base after it was purchased by FAS’ very own Hans Kristensen.

Yandex Maps—Russia’s foremost mapping service—has also agreed to selectively blur out specific sites beyond recognition; however, it has done so for just two countries: Israel and Turkey. The areas of these blurred sites range from large complexes—such as airfields or munitions storage bunkers—to small, nondescript buildings within city blocks.

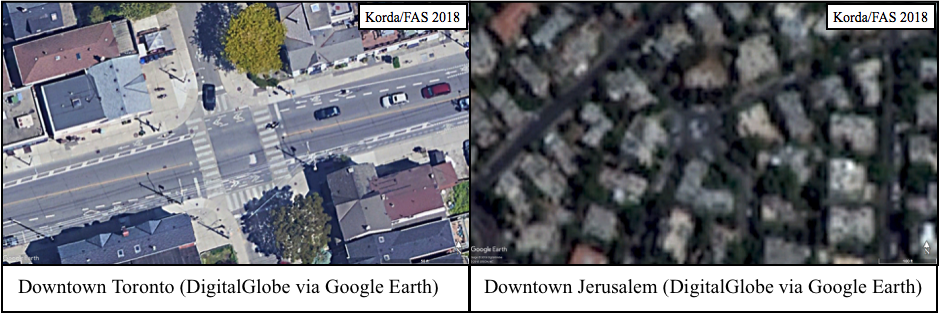

Although blurring out specific sites is certainly unusual, it is not uncommon for satellite imagery companies to downgrade the resolution of certain sets of imagery before releasing them to viewing platforms like Yandex or Google Earth; in fact, if you trawl around the globe using these platforms, you’ll notice that different locations will be rendered in a variety of resolutions. Downtown Toronto, for example, is always visible at an extremely high resolution; looking closely, you can spot my bike parked outside my old apartment. By contrast, imagery of downtown Jerusalem is always significantly blurrier; you can just barely make out cars parked on the side of the road.

As I explained in my previous piece about geolocating Israeli Patriot batteries, a 1997 US law known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment (KBA) prohibits US companies from publishing satellite imagery of Israel at a Ground Sampling Distance lower than what is commercially available. This generally means that US-based satellite companies like DigitalGlobe and viewing platforms like Google Earth won’t publish any images of Israel that are better than 2m resolution.

Foreign mapping services like Russia’s Yandex are legally not subject to the KBA, but they tend to stick to the 2m resolution rule regardless, likely for two reasons. Firstly, after 20 years the KBA standard has become somewhat institutionalized within the satellite imagery industry. And secondly, Russian companies (and the Russian state) are surely wary of doing anything to sour Russia’s critical relationship with Israel.

However, Yandex has taken a step well beyond simply downgrading its Israeli imagery, as is typical for most mapping services. Yandex itself—or perhaps its imagery provider ScanEx—has blurred out specific military installations in their entirety. Interestingly, it has done the same to Turkey, a country that benefits from no special standards and is therefore almost always shown in very high resolution.

This blurring is almost certainly the result of requests from both Israel and Turkey; it seems highly unlikely that a Russian company would undertake such a time-consuming task of its own volition. Fortunately (from an OSINT perspective), this has had the unintended effect of revealing the location and exact perimeter of every significant military facility within both countries, if one is obsessive curious enough to sift through the entire map looking for blurry patches. Matching the blurred sites to un-blurred (albeit downgraded) imagery available through Google Earth is a method of “tipping and cueing,” in which one dataset is used to inform a more detailed analysis of a second dataset.

My complete list of blurred sites in both Israel and Turkey totals over 300 distinct buildings, airfields, ports, bunkers, storage sites, bases, barracks, nuclear facilities, and random buildings—prompting several intriguing points of consideration:

- Included in the list of Yandex’s blurred sites are at least two NATO facilities: Allied Land Command (LANDCOM) in Izmir, and Incirlik Air Base, which hosts the largest contingent of US B61 nuclear gravity bombs at any single NATO base.

- Strangely, no Russian facilities have been blurred—including its nuclear facilities, submarine bases, air bases, launch sites, or numerous foreign military bases in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, or the Middle East.

- Although none of Russia’s permanent military installations in Syria have been blurred, almost the entirety of Syria is depicted in extremely low resolution, making it nearly impossible to utilize Yandex for analyses of Syrian imagery. By contrast, both Crimea and the entire Donbass region are visible at very high resolutions, so this blurring standard applies only selectively to Russia’s foreign adventures.

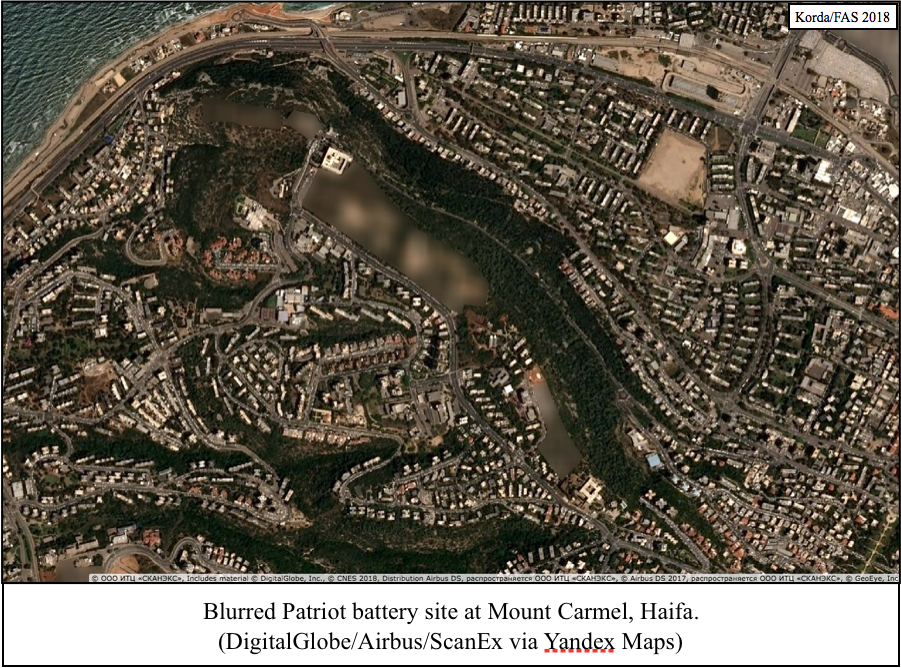

- All four Israeli Patriot batteries that I identified using radar interference in my previous post have been blurred out, confirming that these sites do indeed have a military function.

Putting aside the geopolitical intrigue of Russia’s relations with both Israel and Turkey, Yandex’s actions are a prime example of what is known as the Streisand Effect. In 2003, Barbra Streisand attempted to sue a photographer who posted photos of her Malibu mansion online, claiming $10 million in damages and demanding that the innocuous photo be taken down. Her actions completely backfired: not only did Streisand lose the case and have to cover the defendant’s legal fees, but the attention raised by her lawsuit directed significant traffic to the photo in question. Before the lawsuit, the photo had only been viewed six times (including twice by Streisand’s lawyers); a month later, the photo had accumulated over 420,000 views—a prime example of how attempting to obscure something is actually likely to result in unwanted attention.

So too with Yandex. By complying with requests to selectively obscure military facilities, the mapping service has actually revealed their precise locations, perimeters, and potential function to anyone curious enough to find them all.

An X reveals a Diamond: locating Israeli Patriot batteries using radar interference

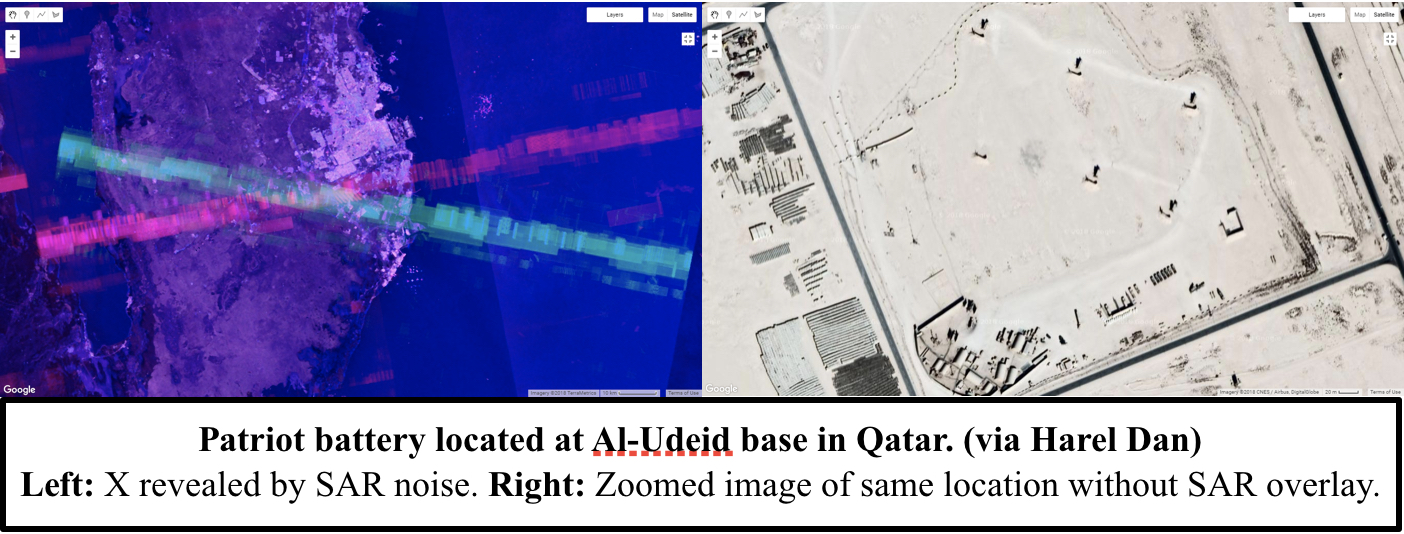

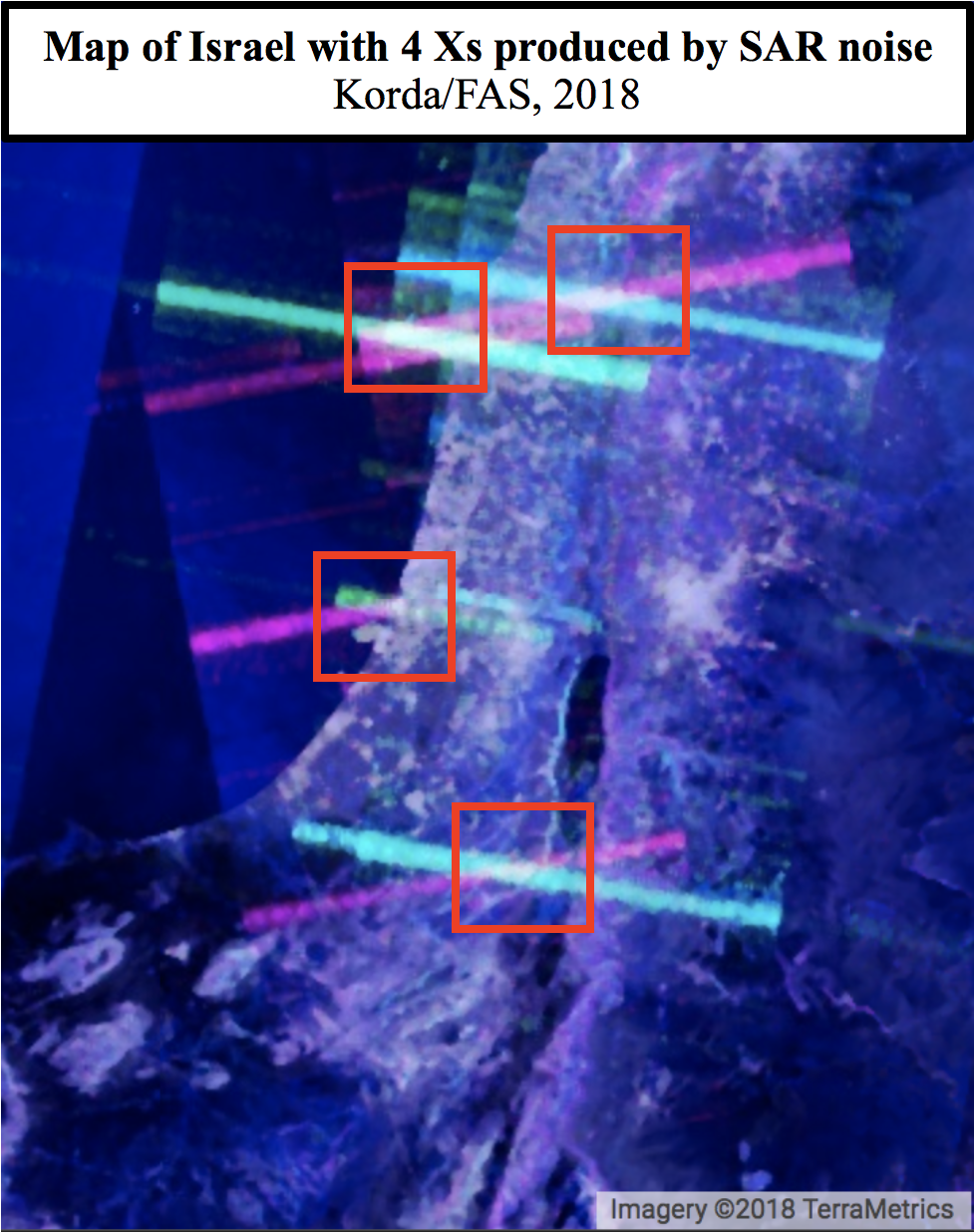

Amid a busy few weeks of nuclear-related news, an Israeli researcher made a very surprising OSINT discovery that flew somewhat under the radar. As explained in a Medium article, Israeli GIS analyst Harel Dan noticed that when he accidentally adjusted the noise levels of the imagery produced from the SENTINEL-1 satellite constellation, a bunch of colored Xs suddenly appeared all over the globe.

SENTINEL-1’s C-band Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) operates at a centre frequency of 5.405 GHz, which conveniently sits within the range of the military frequency used for land, airborne, and naval radar systems (5.250-5.850 GHz)—including the AN/MPQ-53/65 phased array radars that form the backbone of a Patriot battery’s command and control system. Therefore, Harel correctly hypothesized that some of the Xs that appeared in the SENTINEL-1 images could be triggered by interference from Patriot radar systems.

Using this logic, he was able to use the Xs to pinpoint the locations of Patriot batteries in several Middle Eastern countries, including Qatar, Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia.

Harel’s blog post also noted that several Xs appeared within Israeli territory; however, the corresponding image was redacted (I’ll leave you to guess why), leaving a gap in his survey of Patriot batteries stationed in the Middle East.

This blog post partially fills that gap, while acknowledging that there are some known Patriot sites—both in Israel and elsewhere around the globe—that interestingly don’t produce an X via the SAR imagery.

All of these sites were already known to Israel-watchers and many have appeared in news articles, making Harel’s redaction somewhat unnecessary—especially since the images reveal nothing about operational status or system capabilities.

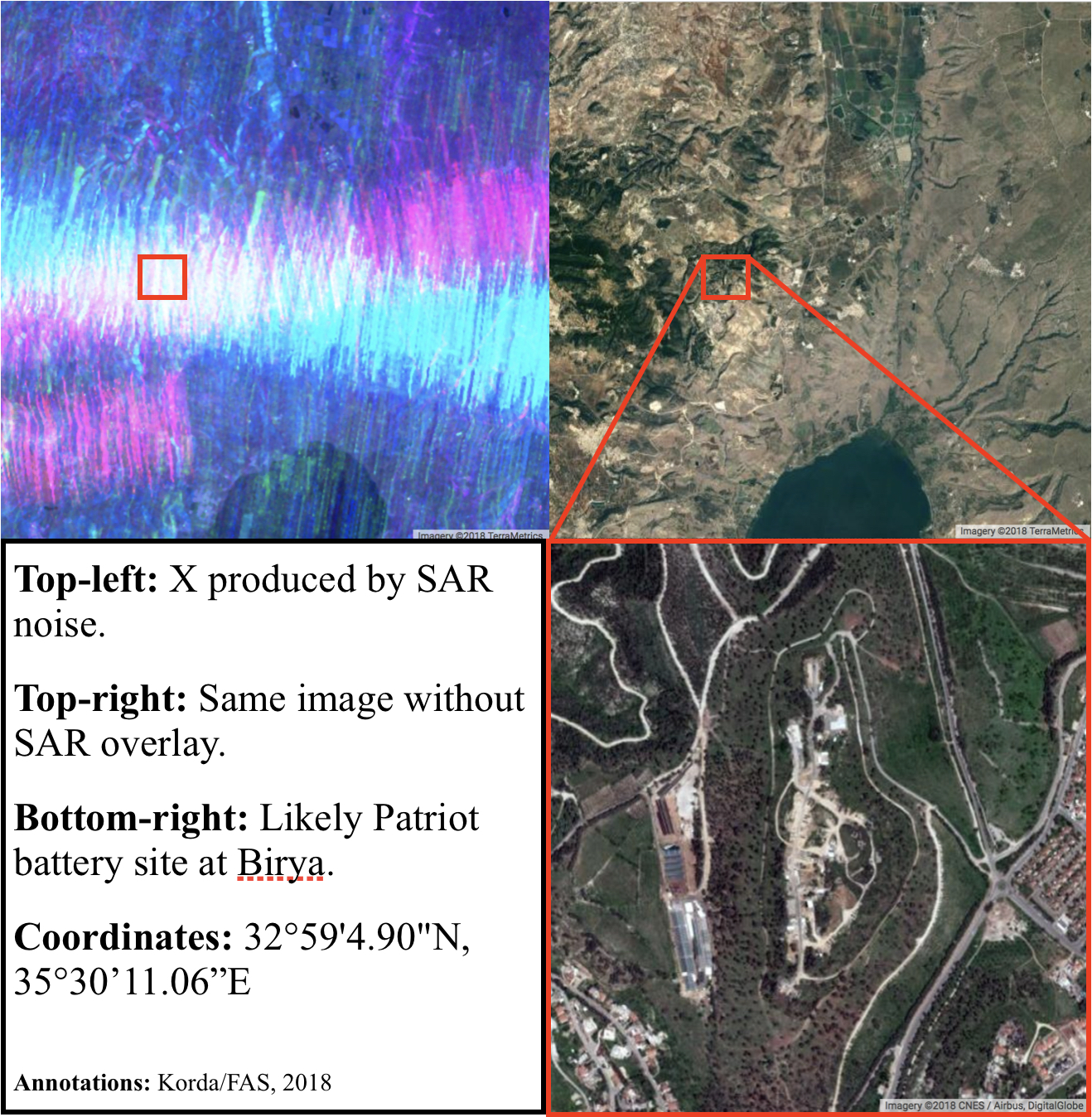

Looking at the map of Israel through the SENTINEL-1 SAR images, four Xs are clearly visible: one in the Upper Galilee, one in Haifa, one near Tel Aviv, and one in the Negev. All of these Xs correspond to likely Patriot battery sites, which are known in Israel as “Yahalom” (יהלום, meaning “Diamond”) batteries. Let’s go from north to south.

The northernmost site is home to the 138th Battalion’s Yahalom battery at Birya, which made news in July 2018 for successfully intercepting a Syrian Su-24 jet which had reportedly infiltrated two kilometers into Israeli airspace before being shot down. Earlier that month, the Birya battery also successfully intercepted a Syrian UAV which had flown 10 kilometers into Israeli airspace.

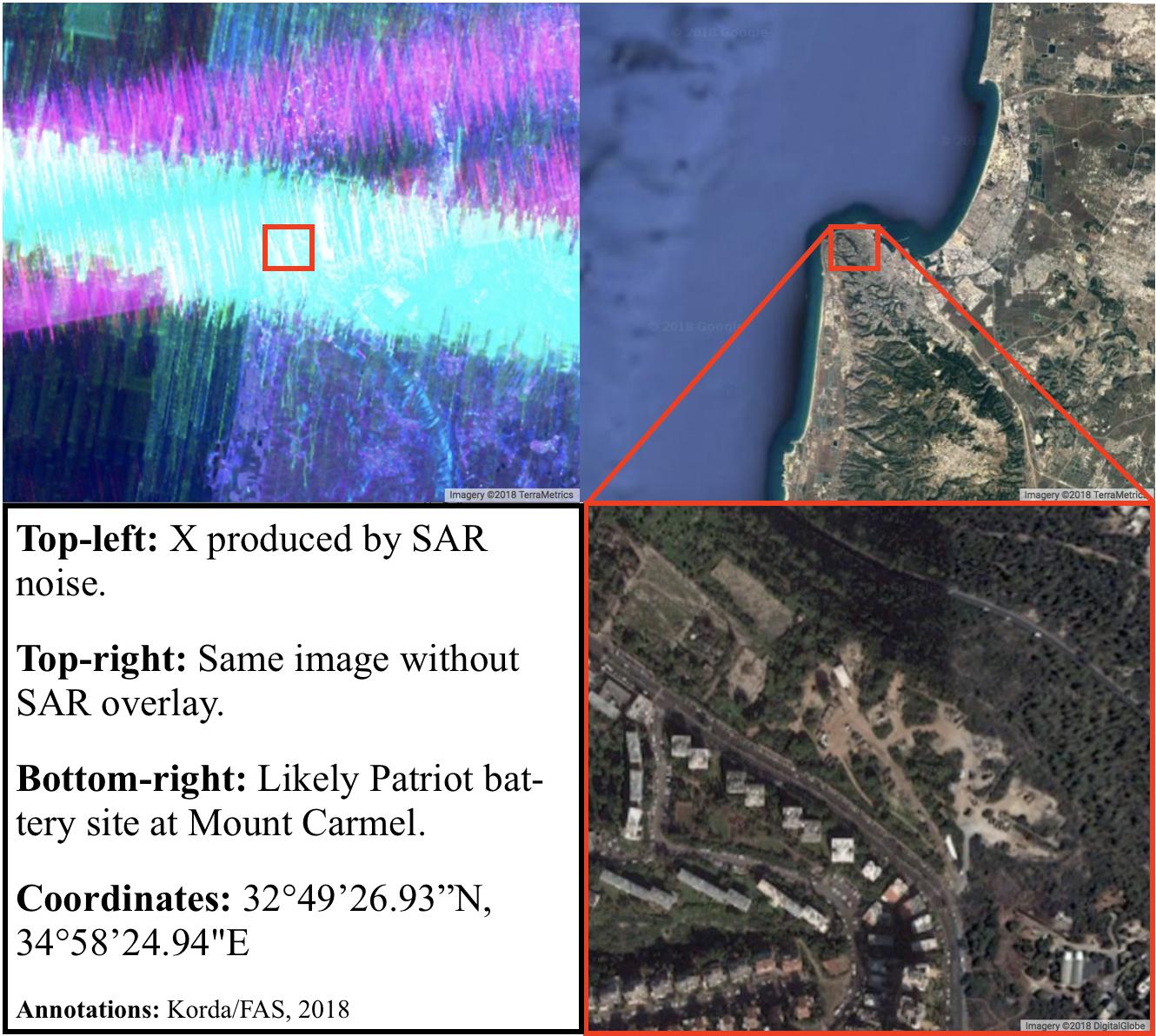

The Yahalom battery in the northwest is based on one of the ridges of Mount Carmel, near Haifa’s Stella Maris Monastery. It is located only 50 meters from a residential neighborhood, which has understandably triggered some resentment from nearby residents who have complained that too much ammunition is stored there and that the air sirens are too loud.

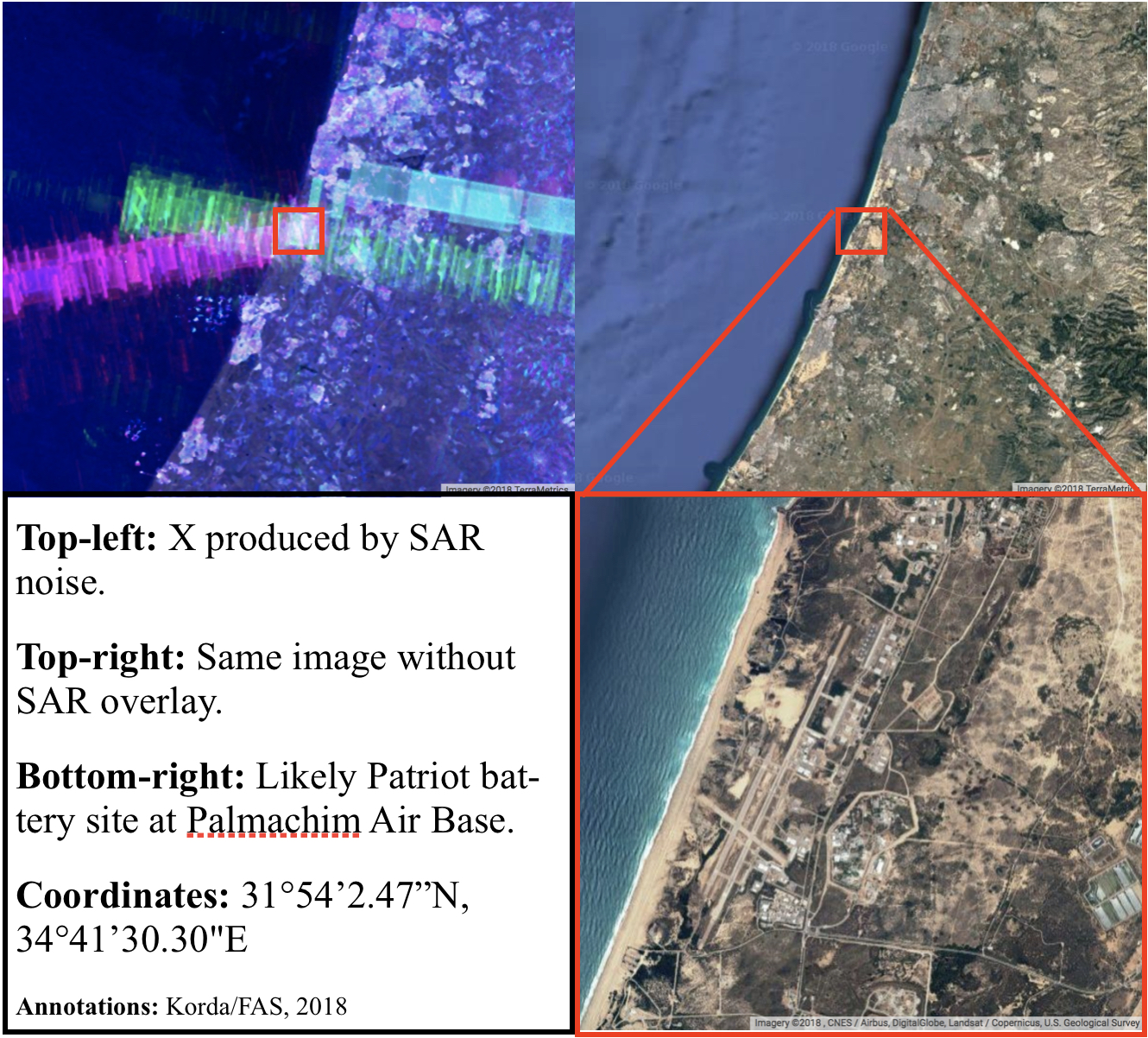

The X in the west indicates the location of a Yahalom site at Palmachim air base, south of Tel Aviv, where Israel conducts its missile and satellite launches. In March 2016, the Israeli Air Force launched interceptors as part of a pre-planned missile defense drill, and while the government refused to divulge the location of the battery, an Israeli TV channel reported that the drill was conducted using Patriot missiles fired from Palmachim air base.

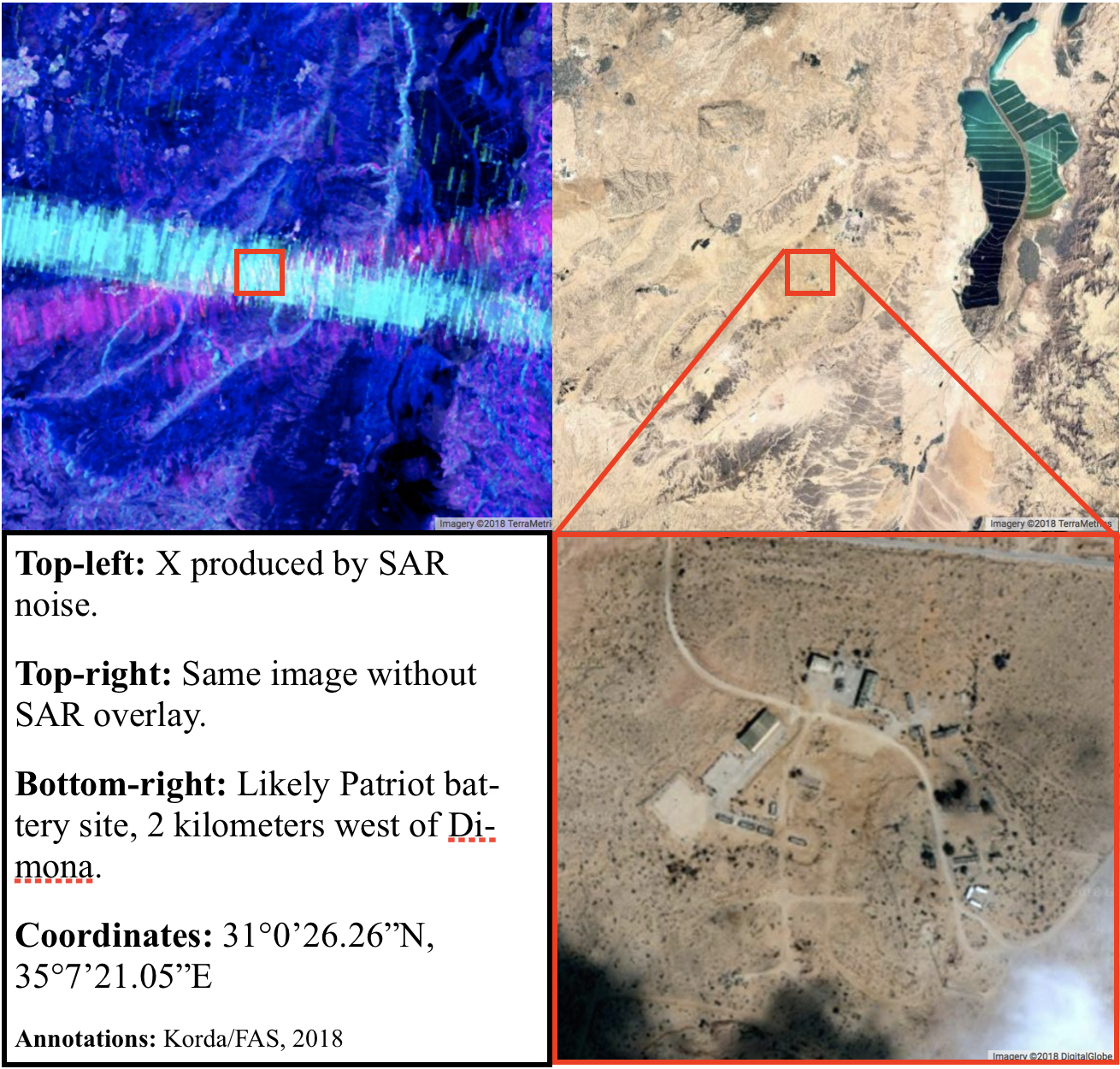

Finally, the X in the southeast sits right on top of the Negev Nuclear Research Centre, more commonly known as Dimona. This is the primary facility relating to Israel’s nuclear weapons program and is responsible for plutonium and tritium production. The site is known to be heavily fortified; during the Six Day War, an Israeli fighter jet that had accidentally flown into Dimona’s airspace was shot down by Israeli air defenses and the pilot was killed.

The proximity of the Negev air defense battery to an Israeli nuclear facility is not unique. In fact, the 2002 SIPRI Yearbook suggests that several of the Yahalom batteries identified through SENTINEL-1 SAR imagery are either co-located with or located close to facilities related to Israel’s nuclear weapons program. The Palmachim site is near the Soreq Centre, which is responsible for nuclear weapons research and design, and the Mount Carmel site is near the Yodefat Rafael facility in Haifa—which is associated with the production of Jericho missiles and the assembly of nuclear weapons—and near the base for Israel’s Dolphin-class submarines, which are rumored to be nuclear-capable.

Google Earth’s images of Israel have been intentionally blurred since 1997, due to a US law known as the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment which prohibits US satellite imagery companies from selling pictures that are “no more detailed or precise than satellite imagery of Israel that is available from commercial sources.” As a result, it is not easy to locate the exact position of the Yahalom batteries; for example, given the number of facilities and the quality of the imagery, the site at Palmachim is particularly challenging to spot.

However, this law is actually being revisited this year and could soon be overturned, which would be a massive boon for Israel-watchers. Until that happens though, Israel will remain blurry and difficult to analyze, making creative OSINT techniques like Harel’s all the more useful.

—–

Sentinel-1 data from 2014 onwards is free to access via Google Earth Engine here, and Harel’s dataset is available here.

NNSA Plan Shows Nuclear Warhead Cost Increases and Expanded Production

By Hans M. Kristensen

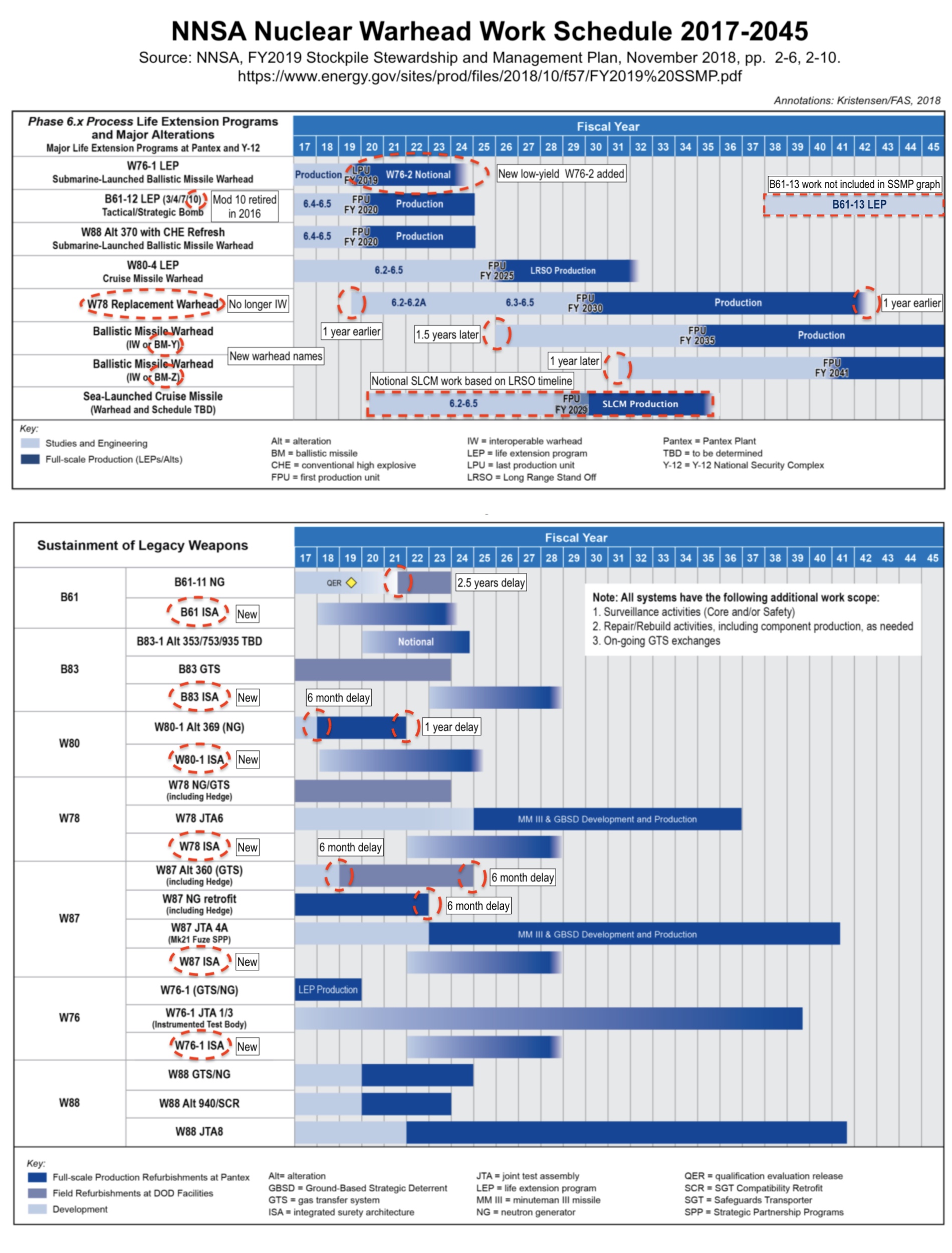

NNSA has published the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan for Fiscal Year 2019, which updates the agency’s work on producing and maintaining the U.S. stockpile of nuclear warheads.

The latest plan follows the broad outlines of last year’s plan but contains important changes.

The new plan shows significant cost increases and warhead production plans that appear to collide with the fiscal realities facing the Nation in the years ahead.

Significant Cost Increases

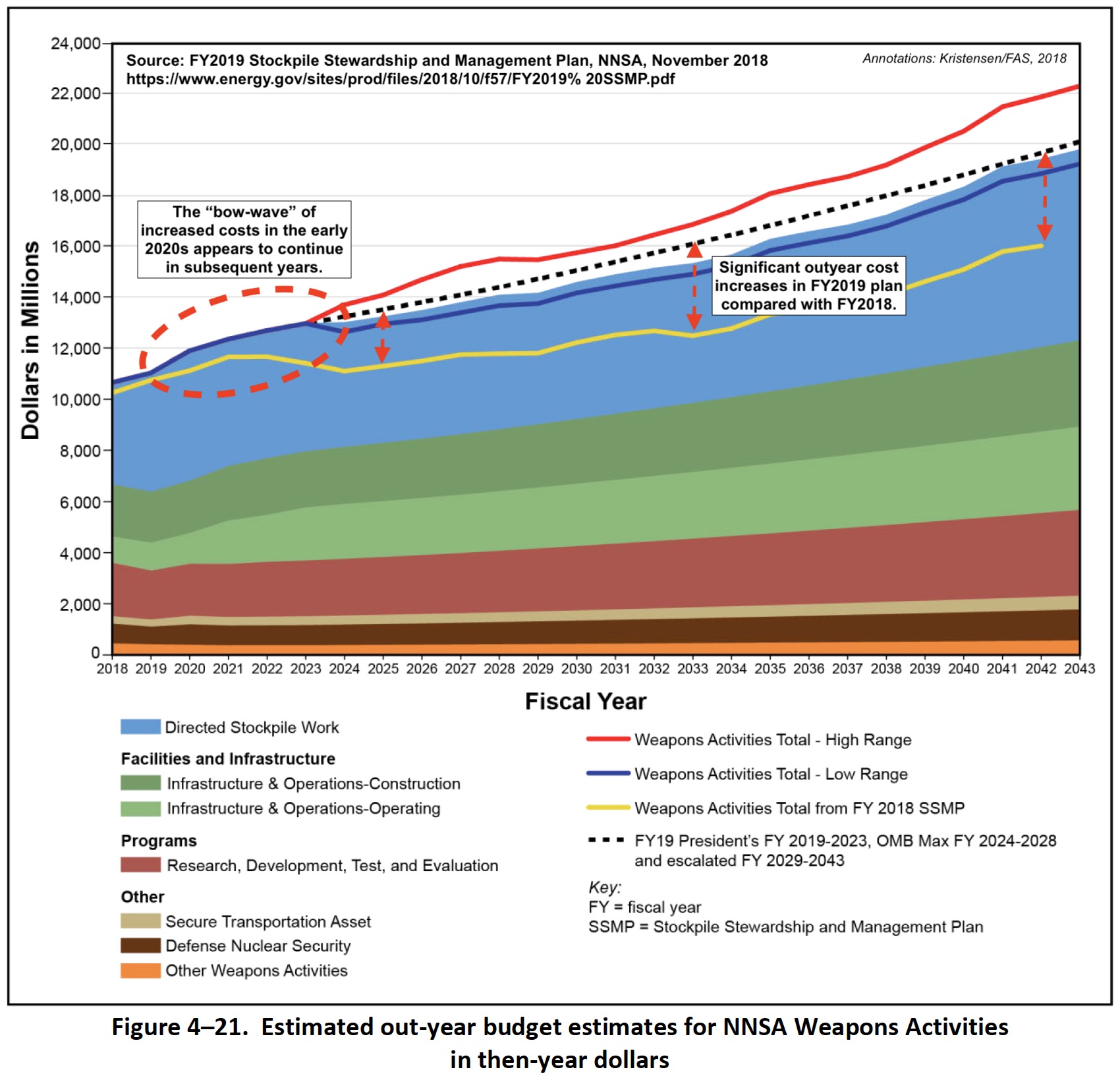

The FY2019 SSMP shows significant increases in out-year cost estimates. The “bow wave” of increased costs in the early-2020s that triggered concerns about affordability appears to have become “a flooding” and continue in subsequent years. The cost-drop the previous SSMP projected for the mid-2020s appears not to be happening. Over the next 25 years, NNSA’s spending on nuclear weapons activities is projected to double (see figure below).

Moreover, the addition of a new SLCM not included in the current plan will further increase costs over the next decade-plus.

FY2019 SSMP shows significant cost increases compared with the FY2018 plan. Click on image to view full size

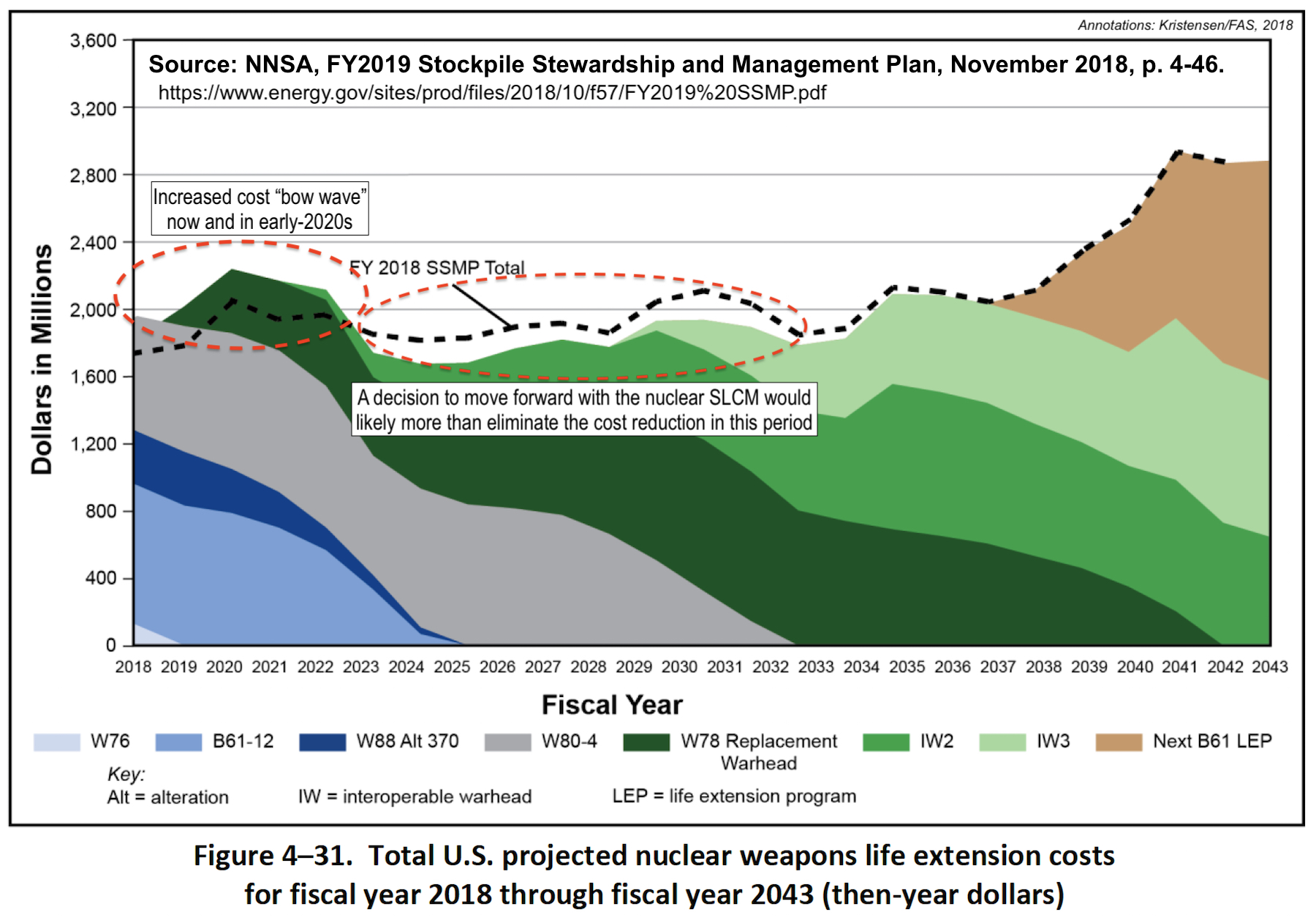

Part of the greater cost comes from increases in the cost estimates for the individual warhead live-extension programs (LEPs). The W78 LEP, one of the two warheads on the Minuteman III ICBM, is now projected to cost $15.4 billion, up 3.3% from $14.9 billion in the previous plan. The high estimate has even greater increase: up from $18.6 billion to $19.5 billion. Moreover, this cost estimate does not include the incremental cost to get to a 30-pit-per-year plutonium capability by FY 2026 to support this LEP. All of the other warhead programs also have cost increases.

In the near-term, these developments result in immediate cost increases and exacerbate the cost “bow wave” in the first half of the 2020s, which shows an increase of several hundred million dollars each year. Total annual LEP costs are lower in the following decade but that reduction would likely be more than erased by expected cost increases and a decision to move forward with development and production of a SLCM as recommended by the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (see figure below).

Cost growth increases fiscal “bow wave” and new weapons would erase future cost reductions. Click on image to view full size

Extensive Warhead Work Planned

The FY2019 SSMP includes several graphs that expand transparency of the nuclear warhead work now and for the next several decades. Most significantly, the SSMP expands information about sustainment work on legacy warheads (those warheads that are already in the stockpile) by breaking it down by work on limited life components (LLCs) such as neutron generators and gas transfer systems, alterations, surety upgrades, and joint test assemblies (JCSs) used for text flights. Overall, this transparency improves overview of the total workload facing the nuclear enterprise.

Interestingly, the so-called “3+2 warhead strategy” that was highlighted in the previous SSMP and congressional hearings as the only way forward is not mentioned in the new plan at all. The intension was to build three interoperable warheads (IWs) for ICBMs and SLBMs and two warheads for aircraft. IW1, which was previously described as a combination of W78 and W88-1, is now simply referred to as the W78 Replacement Program. The two other IWs – the IW2 combining W87 and W88, and the IW3 involving the W76-1 – are now listed with new names: BM-Y and BM-Z.

The SSMP also shows that six warheads will get a new ISA (Integrated Surety Architecture). This involves “improving DOE/NNSA transportation surety by integrating nuclear weapon shipping configurations with physical security elements.” A “matured integrated surety architecture capability to stockpile systems” matured in FY2018 “for further development and integration activities.”

In the graph below, I have combined the SSMP graphs of warhead LEPs and legacy warhead work into one graph and marked changes and omissions compared with the previous SSMP. The new plan includes two new warheads: the low-yield W76-2 and the SLCM.

FY2019 SSMP warhead work sheets show expanded warhead work but do not include several weapons. Click on image to view full size

The LEP section shows W76-2 work stretching out five years from mid-FY2019 (after completion of the current W76-1 LEP) through much of FY2024 (although work might actually be happening one year earlier). The W76-2 is intended to be deployed on SSBNs along with higher-yield W76-1 and W88 warheads. The W76-2 is intended for use in limited “tactical” scenarios in response to for example Russian use of tactical nuclear weapons. It might also serve a role in the expanded nuclear first-use options against “non-nuclear strategic attack” described in the NPR.

The SLCM is mentioned in the SSMP but with no details about the development and production timeline. NNSA says the SLCM “will be a major new addition in the next decade.” In the combined graph I have included a notional SLCM development and production line for illustrative purposes based on the LRSO timeline. It assumes initial startup in FY2020 after completion of an Analysis of Alternatives (AoA).

The SSMP LEP graph does not include the next B61 life extension program (previously called B61-13 in FY2016 SSMP version), which is scheduled to start in 2038. To correct that oversight, I have included it in the graph. This is a major warhead upgrade with cost estimates in the early-2040s ($1.4 billion in 2043) that go beyond that of any other existing or projected LEP program. And based on the cost graph, annual costs estimates would be even greater after 2043. It is yet unclear why the next B61 LEP will be so expensive.

Altogether, the warhead LEP and legacy graphs show a very ambitious workload for the nuclear weapons complex. At some point in the early-2020s, as many as six different warheads LEPs would be in development or production at the same time, in addition to sustainment of legacy warheads in the stockpile.