De-Risking the Clean Energy Transition: Opportunities and Principles for Subnational Actors

Executive Summary

The clean energy transition is not just about technology — it is about trust, timing, and transaction models. As federal uncertainty grows and climate goals face political headwinds, a new coalition of subnational actors is rising to stabilize markets, accelerate permitting, and finance a more inclusive green economy. This white paper, developed by the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) in collaboration with Climate Group and the Center for Public Enterprise (CPE), outlines a bold vision: one in which state and local governments – working hand-in-hand with mission-aligned investors and other stakeholders – lead a new wave of public-private clean energy deployment.

Drawing on insights from the closed-door session “De-Risking the Clean Energy Transition” and subsequent permitting discussions at the 2025 U.S. Leaders Forum, this paper offers strategic principles and practical pathways to scale subnational climate finance, break down permitting barriers, and protect high-potential projects from political volatility. This paper presents both a roadmap and an invitation for continued collaboration. FAS and its partners will facilitate further development and implementation of approaches and ideas described herein, with the goals of (1) directing bridge funding towards valuable and investable, yet at-risk, clean energy projects, and (2) building and demonstrating the capacity of subnational actors to drive continued growth of an equitable clean economy in the United States.

We invite government agencies, green banks and other financial institutions, philanthropic entities, project developers, and others to formally express interest in learning more and joining this work. To do so, contact Zoe Brouns (zbrouns@fas.org).

The Moment: Opportunity Meets Urgency

We are in the complex middle of a global energy transition. Clean energy and technology are growing around the world, and geopolitical competition to consolidate advantage in these sectors is intensifying. The United States has the potential to lead, but that leadership is being tested by erratic federal environmental policies and economic signals. Meanwhile, efforts to chart a lasting domestic clean energy path that resonates with the full American public have fallen short. Demand is rising — fueled by AI, electrification, and industrial onshoring – yet opposition to clean energy buildout is growing, permitting systems are gridlocked, and legacy regulatory frameworks are failing to keep up. This moment calls for new leadership rooted in local and regional capacity and needs. Subnational governments, green and infrastructure banks, and other funders have a critical opportunity to stabilize clean energy investment and sustain progress amid federal uncertainty. Thanks to underlying market trends favoring clean energy and clean technology, and to concerted efforts over the past several years to spur U.S. growth in these sectors, there is now a pipeline of clean projects across the country that are shovel-ready, relatively de-risked and developed, and investable (Box 1). Subnational actors can work together to identify these projects, and to mobilize capital and policy to sustain them in the near term.

The New York Power Authority used a simple, quick Request for Information (RFI) to identify readily investible clean energy projects in New York, and was then able to financially back many of the identified projects thanks to its strong bond rating and ability to access capital. As Paul Williams, CEO of the Center for Public Enterprise, noted, this powerful approach allowed the Authority to “essentially [pull] a 3.5-gigawatt pipeline out of thin air in less than a year.”

States, cities, and financial institutions are already beginning to provide the support and sustained leadership that federal agencies can no longer guarantee. They’re developing bond-backed financing, joint procurement schemes, rapid permitting pilot zones, and revolving loan funds — not just to fill gaps, but to reimagine what clean energy governance looks like in an era of fragmentation. One compelling example is the Connecticut Green Bank, which has successfully blended public and private capital to deploy over $2 billion in clean energy investments since its founding. Through programs like its Commercial Property Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE) financing and Solar for All initiative, the bank has reduced emissions, created jobs, and delivered energy savings to underserved communities.

Indeed, this kind of mission-oriented strategy – one that harnesses finance and policy towards societally beneficial outcomes, and that entrepreneurially blends public and private capacities – is in the best American tradition. Key infrastructure and permitting decisions are made at the state and local levels, after all. And state and local governments have always been central to creating and shaping markets and underwriting innovation that ultimately powers new economic engines. The upshot is clear and striking: subnational climate finance isn’t just a workaround. It may be the most politically durable and economically inclusive way to future-proof the clean energy transition.

The Role of Subnational Finance in the Clean Energy Transition

Recent years saw heavy reliance on technocratic federal rules to spur a clean energy transition. But a new political climate has forced a reevaluation of where and how federal regulation works best. While some level of regulation is important for creating certainty, demand, and market and investment structures, it is undeniable that the efficacy and durability of traditional environmental regulatory approaches has waned. There is an acute need to articulate and test new strategies for actually delivering clean energy progress (and a renewed economic paradigm for the country) in an ever-more complex society and dynamic energy landscape.

Affirmatively wedding finance with larger public goals will be a key component of this more expansive, holistic approach. Finance is a powerful tool for policymakers and others working in the public interest to shape the forward course of the green economy in a fair and effective way. In the near term, opportunities for subnational investments are ripe because the now partially paused boom in potential firms and projects generated by recent U.S. industrial policy has generated a rich set of already underwritten, due-diligenced projects for re-investment. In the longer term, the success of redesigned regulatory schema will almost certainly depend on creating profitable firms that can carry forward the energy transition. Public entities can assume an entrepreneurial role in ensuring these new economic entities, to the degree they benefit from public support, advance the public interest. Indeed, financial strategies that connect economic growth to shared prosperity will be important guardrails for an “abundance” approach to environmental policy – an approach that holds significant promise to accelerate necessary societal shifts, but also presents risk that those shifts further enrich and empower concentrated economic interests.

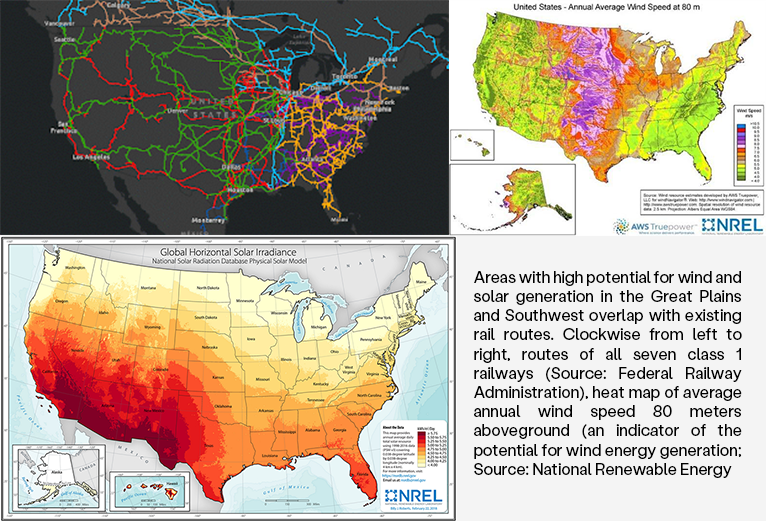

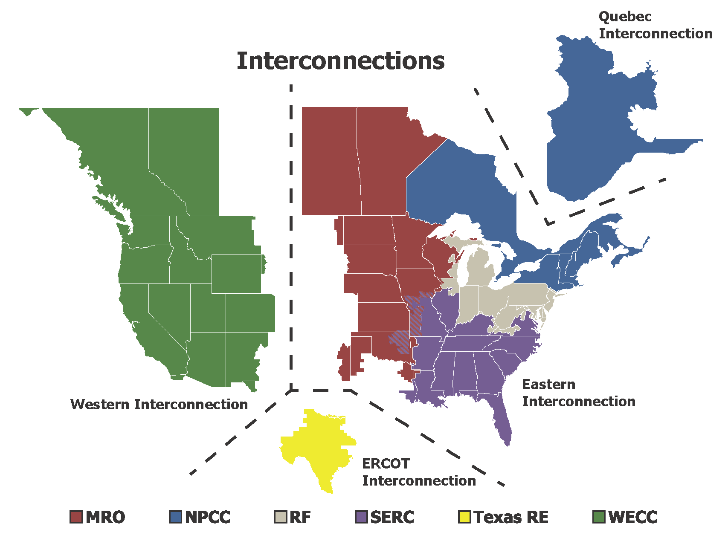

To be sure, subnational actors generally cannot fund at the scale of the federal government. However, they can mobilize existing revenue and debt resources, including via state green and infrastructure banks, bonding tools, and direct investment financing strategies, to seed capital for key projects and to provide a basis for larger capital stacks for key endeavors. They are also particularly well suited to provide “pre-development” support to help projects move through start-up phases and reach construction and development. Subnational entities can engage sectorally and in coalition to scale up financing, to draw in private actors, and to support projects along the whole supply and value chain (including, for instance, multi-state transmission and grid projects, multi-state freight and transportation network improvements, and multi-state industrial hubs for key technologies).

A wide range of financing strategies for clean energy projects already exist. For instance:

- Revolving loan funds can help public entities provide lower-cost debt financing to draw in additional private capital.

- Joint procurements or bundled financing can set technological standards, provide pricing power, and reduce the cost of capital for smaller businesses and make it easier for them to break into the clean energy economy.

- Financing programs for projects with public benefits can be designed in ways that allow government investors to take a small equity stake, sharing both risk and revenue over time.

Strategies like these empower states and other subnational actors to de-risk and drive the clean energy transition. The expanding green banking industry in the United States, and similar institutions globally, further augment subnational capacity. What is needed is rapid scaling and ready capitalization.

There is presently tremendous need and opportunity to deploy flexible financing strategies across projects that are shovel-ready or in progress but may need bridge funding or other investments in the wake of federal cuts. The critical path involves quickly identifying valuable, vetted projects in need of support, followed by targeted provision of financing that leverages the superior capital access of public institutions.

Projects could be identified through simple, quick Requests for Information (RFIs) like the one recently used to great effect by the New York Power Authority to build a multi-gigawatt clean energy pipeline (see Box 1, above). This model, which requires no new legislation, could be adopted by other public entities with bonding authority. Projects could also be identified through existing databases, e.g., of projects funded by, or proposed for funding under, the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) or Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA).

There is even the possibility of establishing a matchmaking platform that connects projects in need of financing with entities prepared to supply it. Projects could be grouped sectorally (e.g., freight or power sector projects) or by potential to address cross-cutting issues (e.g., cutting pollution burdens or managing increasing power grid load and its potential to electrify new economic areas). As economic mobilization around clean energy gains steam and familiarity with flexible financing strategies grows, such strategies can be extended to new projects in ways that are tailored to community interests, capacity, and needs.

Principles for Effective, Equitable Investment

The path outlined above is open now but will substantially narrow in the coming months without concerted, coordinated action. The following principles can help subnational actors capitalize on the moment effectively and equitably. It is worth emphasizing that equitable investment is not only a moral imperative – it is a strategic necessity for maintaining political legitimacy, ensuring community buy-in, and delivering long-term economic resilience across regions.

Funders must clearly state goals and be proactive in pursuing them – starting now to address near-term instability. Rather than waiting for projects to come to them, subnational governments, financial institutions, and other funders should use their platforms and convening power to lay out a “mission” for their investments – with goals like electrifying the industrial sector, modernizing freight terminals and ports, and accelerating transmission infrastructure with storage for renewables. Funders should then use tools like simple RFIs to actively seek out potential participants in that mission.

Public equity is a key part of the capital stack, and targeted investments are needed now. With significant federal climate investments under litigation and Congressional debates on the Inflation Reduction Act ongoing, other participants in the domestic funding ecosystem must step up. Though not all federal capital can (or should) be replaced, targeted near-term investments coupled with multi-year policy and funding roadmaps by these actors can help stabilize projects that might not otherwise proceed and provide reassurance on the long-term direction of travel.

Information is a surprisingly powerful tool. Deep, shared, information architectures and clarity on policy goals are key for institutional investors and patient capital. Shared information on costs, barriers, and rates of return would substantially help facilitate the clean energy transition – and could be gathered and released by current investors in compiled form. Sharing transparent goals, needs, and financial targets will be especially critical in the coming months. Simple RFIs targeted at businesses and developers can also function as dual-purpose information-gathering and outreach tools for these investors. By asking basic questions through these RFIs (which need not be more than a page!), investors can build the knowledge base for shaping their clean technology and energy plans while simultaneously drawing more potential participants into their investment networks.

States should invest to grow long-term businesses. The clean energy transition can only be self-sustaining if it is profitable and generates firms that can stand on their own. Designing state incentive and investment projects for long-term business growth, and aligning complementary policy, is critical – including by designing incentive programs to partner well with other financing tools, and to produce long-term affordability and deployment gains, especially for entities which may otherwise lack capital access. State strategies, like the one New Mexico recently published, that outline energy-transition and economic plans and timelines are crucial to build certainty and align action across the investment and development ecosystem. Metrics for green programs should assess prospects for long-term business sustainability as well as tons of emissions reduced.

States can finance the clean energy transition while securing long-term returns and other benefits. Many clean technology projects may have higher upfront costs balanced by long-term savings. Debt equity, provided through revolving loan funds, can play a large role in accelerating deployment of these technologies by buying down entry costs and paying back the public investor over time. Moreover, the superior bond ratings of state institutions substantially reduce borrowing costs; sharing these benefits is an important role for public finance. State financial institutions can explore taking equity stakes in some projects they fund that provide substantial public benefits (e.g., mega-charging stations, large-scale battery storage, etc.) and securing a rate of return over time in exchange for buying down upfront risk. Diversified subnational institutions can use cash flows from higher-return portions of their portfolios to de-risk lower-return or higher-risk projects that are ultimately in the public interest. Finally, states with operating carbon market programs can consider expanding their funding abilities by bonding against some portion of carbon market revenues, converting immediate returns to long-term collateral for the green economy.

Financing policy can be usefully combined with procurement policy. As electrification reaches individual communities and smaller businesses, many face capital-access problems. Subnational actors should consider packaging similar businesses together to provide financing for multiple projects at once, and can also consider complementary public procurement policies to pull forward market demand for projects and products (Box 2).

Explore contract mechanisms to protect public benefits. Distributive equity is as important as large-scale investment to ensure a durable economic transition. The Biden-Harris Administration substantially conditioned some investments on the existence of binding community benefit plans to ensure that project benefits were broadly shared and possible harms to communities mitigated. Subnational investors could develop parallel contractual agreements. There may also be potential to use contracts to enable revenue sharing between private and public institutions, partially addressing any impacts of changes to the IRA’s current elective pay and transferability provisions by shifting realized income to the public entities that currently use those programs from the private entities that realize revenue from projects.

Joint procurements, whereby two or more purchasers enter into a single contract with a vendor, can bring down prices of emerging clean technologies by increasing purchase volume, and can streamline technology acquisition by sharing contracting workload across partners. Joint procurement and other innovative procurement policies have been used successfully to drive deployment of zero-emission buses in Europe and, more recently, the United States. Procurement strategies can be coupled with public financing. For instance, the Federal Transit Agency’s Low or No Emission Grant Program for clean buses preferences applications that utilize joint procurement, thereby helping public grant dollars go further.

The rising importance of the electrical grid across sectors creates new financial product opportunities. As the economy decarbonizes, more previously independent sectors are being linked to the electric grid, with load increasing (AI developments exacerbate this trend). That means that project developers in the green economy can offer a broader set of services, such as providing battery storage for renewables at vehicle charging points, distributed generation of power to supply new demand, and potential access to utility rate-making. Financial institutions should closely track rate-making and grid policy and explore avenues to accelerate beneficial electrification. There is a surprising but potent opportunity to market and finance clean energy and grid upgrades as a national security imperative, in response to the growing threat of foreign cyberattacks that are exploiting “seams” in fragile legacy energy systems.

Global markets can provide ballast against domestic volatility. The United States has an innovative financial services sector. Even though federal institutions may retreat from clean energy finance globally over the next few years, there remains a substantial opportunity for U.S. companies to provide financing and investment to projects globally, generate trade credit, and to bring some of those revenues back into the U.S. economy.

Financial products and strategies for adaptation and resilience must not be overlooked. Growing climate-linked disasters, and associated adaptation costs, impose substantial revenue burdens on state and local governments as well as on insurers and businesses. Competition for funds between adaptation and mitigation (not to mention other government services) may increase with proposed federal cuts. Financial institutions that design products that reduce risk and strengthen resilience (e.g., by helping relocate or strengthen vulnerable buildings and infrastructure) can help reduce these revenue competitions and provide long-term benefits by tapping into the $1.4 trillion market for adaptation and resilience solutions. Improved cost-benefit estimates and valuation frameworks for these interacting systems are critical priorities.

Conclusion: A Defining Window for Subnational Leadership

Leaders from across the country agree: clean energy and clean technology are investable, profitable, and vital to community prosperity. And there is a compelling lane for innovative subnational finance as not just a stopgap or replacement for federal action, but as a central area of policy in its own right.

The federal regulatory state is, increasingly, just a component of a larger economic transition that subnational actors can help drive, and shape for public benefit. Designing financial strategies for the United States to deftly navigate that transition can buffer against regulatory uncertainty and create a conducive environment for improved regulatory designs going forward. Immediate responses to stabilize climate finance, moreover, can build a foundation for a more engaged, and innovative, coalition of subnational financial actors working jointly for the public good.

Active state and private planning is the key to moving down these paths, with governments setting a clear direction of travel and marshaling their convening powers, capital access, and complementary policy tools to rapidly stabilize key projects and de-risk future capital choices.

There is much to do and no time to lose as governments and investors across the country seek to maintain clean technology progress. The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) and its partners will facilitate further development and implementation of approaches and ideas described above, with the goals of (1) directing bridge funding towards valuable and investable, yet at-risk, clean energy projects, and (2) building and demonstrating the capacity of subnational actors to drive continued growth of an equitable clean economy in the United States.

We invite government agencies, green banks and other financial institutions, philanthropic entities, project developers, and others to formally express interest in learning more and joining this work. To do so, contact Zoe Brouns (zbrouns@fas.org).

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the many partners who contributed to this report, including: Dr. Jedidah Isler and Zoë Brouns at the Federation of American Scientists, Sydney Snow at Climate Group, Yakov Feigin, Chirag Lala, and Advait Arun at the Center for Public Enterprise, and Jayni Hein at Covington and Burling LLP.

Updating the Clean Electricity Playbook: Learning Lessons from the 100% Clean Agenda

Building clean energy faster is the most significant near-term strategy to combat climate change. While the Biden Administration and the advocacy community made significant gains to this end over the past few years, we failed to secure major pieces of the policy agenda, and the pieces we did secure are not resulting in as much progress as projected. As a result, clean energy deployment is lagging behind levels needed to match modeled cost-effective scenarios, let alone to achieve the Paris climate goals. Simultaneously, the Trump Administration is actively dismantling the foundations that have underpinned our existing policy playbook.

Adjusting course to rapidly transform the electricity sector—to cut pollution, reduce costs, and power a changing economy—requires us to upgrade the regulatory frameworks we rely upon, the policy tools we prioritize, and the coalition-building and messaging strategies we use.

After leaving the Biden Administration, I joined FAS as a Senior Fellow to jump into this work. We plan to assess the lessons from the Biden era electricity sector plan, interrogate what is and is not working from the advocacy community’s toolkit, and articulate a new vision for policy and strategy that is durable and effective, while meeting the needs of our modern society. We need a new playbook that starts in the states and builds toward a national mission that can tackle today’s pressing challenges and withstand today’s turbulent politics. And we believe that this work must be transpartisan—we intend to draw from efforts underway in a wide range of local political contexts to build a strategy that appeals to people with diverse political views and levels of political engagement.

This project is part of a larger FAS initiative to reimagine the U.S. environmental regulatory state and build a new system that can address our most pressing challenges.

Betting Big on 100% Clean Electricity

If we are successful in fighting the climate crisis, the largest share of domestic greenhouse gas emissions reductions over the next ten years will come from building massive amounts of new clean energy and in turn reducing pollution from coal- and gas-fired power plants. Electricity will also need to be cheap, clean, and abundant to move away from gasoline vehicles, natural gas appliances in homes, and fossil fuel-fired factories toward clean electric alternatives.

That’s why clean electricity has been the centerpiece of federal and state climate policy. The signature climate initiative of the Obama Administration was the Clean Power Plan. Over the past several decades, states have made the most emissions progress through renewable portfolio standards and clean electricity standards that require power companies to provide increasing amounts of clean electricity. Now 24 (red and blue) states and D.C. have goals or requirements to achieve 100 percent clean electricity. And in the 2020 election, Democratic primary candidates competed over how ambitious their plans were to transform the electricity grid and deploy clean energy.

As a result of that competition and the climate movement’s efforts to put electricity at the center of the strategy, President Biden campaigned on achieving 100 percent clean electricity by 2035. This commitment was very ambitious—it surpassed every state goal except Vermont’s, Rhode Island’s, and D.C.’s. In making such a bold commitment, Biden recognized how essential the power sector is to addressing the climate crisis. He also staked a bet that the right policies—large incentives for companies, worker protections, and support for a diverse mix of low-carbon technologies—would bring together a coalition that would fight for the legislation and regulations needed to make the 2035 goal a reality.

A Mix of Wins and Losses

That bet only partially paid off. We won components of the agenda that made major strides toward 100% clean electricity. New tax credits are accelerating deployment of wind, solar, and battery storage (although the Trump Administration and Republicans in Congress are actively working to repeal these credits). Infrastructure investments are driving grid upgrades to accommodate additional clean energy. And new grant programs and procurement policies are speeding up commercialization of critical technologies such as offshore wind, advanced nuclear, and enhanced geothermal.

But the movement failed to secure the parts of the plan that would have ensured an adequate pace of deployment and pollution reductions, including a federal clean electricity standard, a suite of durable emissions regulations to cover the full sector, and federal and state policies to reduce roadblocks to new infrastructure and align utility incentives with clean energy deployment. We ran into real-world and political headwinds that held us back. For example, deployment was stifled by long timelines to connect projects to the grid and local ordinances and siting practices that block clean energy. Policy initiatives were thwarted by political opposition from perceived reliability impacts and blowback from increasing electricity rates, especially for newer technologies like offshore wind and advanced nuclear. The opposition to clean energy successfully weaponized the rising cost of living to fight climate policies, even where clean energy would make life less expensive. These barriers not only impeded commercialization and deployment but also dampened support from key stakeholders (project developers, utilities, grid operators, and state and local leaders) for more ambitious policies. The necessary coalitions did not come together to support and defend the full agenda.

As a result, we are building clean energy much too slowly. In 2024, the United States built nearly 50 gigawatts of new clean power. This number, while a new record, falls short of the amount needed to address the climate crisis. Analysis from three leading research projects found that, with the tax incentives in the Inflation Reduction Act, the future in which we get within striking distance of the Paris climate goals requires 70 to 125 gigawatts of new clean power per year for the next five years, 40 to 250 percent higher than our record annual buildout.

Where do we go from here?

The climate crisis demands faster and deeper policy change with more staying power. Addressing the obvious obstacles standing in the way of clean energy deployment, like the process to connect power plants to the grid, is necessary but insufficient. We must also develop new policy frameworks and expanded coalitions to facilitate the rapid transformation of the electricity system.

This work requires us to ask and creatively answer an evolving set of questions, including: What processes are holding us back from faster buildout, and how do we address them? How can utility incentives be better aligned with the deployment and infrastructure investment we need and support for the required policies? How can the way we pay for electricity be better designed to protect customers and a livable climate? Where have our coalitional strategies failed to win the policies we need, and how do we adjust? How should we talk about these problems and the solutions to build greater support?

We must develop answers to these questions in a way that leads us to more transformative, lasting policies. We believe that, in the near term, much of this work must happen at the state level, where there is energy to test out new ideas and frameworks and iterate on them. We plan to build out a state-level playbook that is actionable, dynamic, and replicable. And we intend to learn from the experiences of states and municipalities with diverse political contexts to develop solutions that address the concerns of a wide range of audiences.

We cannot do this work on our own. We plan to draw on the expertise of a diverse range of organizations and people who have been working on these problems from many vantage points. If you are working on these issues and are interested, please join us in collaboration and conversation by reaching out to akrishnaswami@fas.org.

AI, Energy, and Climate: What’s at Stake? Hint: A lot.

DC’s first-ever Climate Week brought with it many chances to discuss the hottest-button topics in climate innovation and policy. FAS took the opportunity to do just that, by hosting a panel to explore the intersection of artificial intelligence (AI), energy, and climate issues with leading experts. Dr. Oliver Stephenson, FAS’ Associate Director of Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Policy, sat down with Dr. Tanya Das, Dr. Costa Samaras, and Charles Hua to discuss what’s at stake at this critical crossroads moment.

Missed the panel? Don’t fret. Read on to learn the need-to-knows. Here’s how these experts think we can maximize the “good” and minimize the “bad” of AI and data centers, leverage research and development (R&D) to make AI tools more successful and efficient, and how to better align incentives for AI growth with the public good.

First, Some Level Setting

The panelists took their time to make sure the audience understood two key facts regarding this space. First, not all data centers are utilized for AI. The Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) estimates that AI applications are only used in about 10-20% of data centers. The rest? Data storage, web hosting capabilities, other cloud computing, and more.

Second, load growth due to the energy demand of data centers is happening, but the exact degree still remains unknown. Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL) models project that data centers in the US will consume anywhere between 6.7% and 12% of US electricity generation by 2028. For a country that consumes roughly 4 trillion kilowatt hours (kWh) of electricity each year, this estimation spans a couple hundred billion kWh/year from the low end to the high. Also, these projections are calculated based on different assumptions that factor in AI energy efficiency improvements, hardware availability, regulatory decisions, modeling advancements, and just how much demand there will be for AI. When each of these conditions are evolving daily, even the most credible projections come with a good amount of uncertainty.

There is also ambiguity in the numbers and in the projections at the local and state levels, as many data center companies shop around to multiple utilities to get the best deal. This can sometimes lead to projects getting counted twice in local projections. Researchers at LBNL have recently said they can confidently make data center energy projections out to 2028. Beyond that, they can’t make reasonable assumptions about data center load growth amid growing load from other sectors working to electrify—like decarbonizing buildings and electric vehicle (EV) adoption.

Maximizing the Good, Minimizing the Bad

As data center clusters continue to proliferate across the United States, their impacts—on energy systems and load growth, water resources, housing markets, and electricity rates—will be most acutely felt at the state and local levels. DC’s nearby neighbor Northern Virginia has become a “data center alley” with more than 200 data centers in Loudoun County alone, and another 117 in the planning stages.

States ultimately hold the power to shape the future of the industry through utility regulation, zoning laws, tax incentives, and grid planning – with specific emphasis on state Public Utility Commissions (PUCs). PUCs have a large influence on where data centers can be connected to the grid and the accompanying rate structure for how each data center pays for its power—whether through tariffs, increasing consumer rates, or other cost agreements. It is imperative that vulnerable ratepayers are not left to shoulder the costs and risks associated with the rapid expansion of data centers, including higher electricity bills, increased grid strain, and environmental degradation.

Panelists emphasized that despite the potential negative impacts of AI and data centers expansion, leaders have a real opportunity to leverage AI to maximize positive outcomes—like improving grid efficiency, accelerating clean energy deployment, and optimizing public services—while minimizing harms like overconsumption of energy and water, or reinforcing environmental injustice. Doing so, however, will require new economic and political incentives that align private investment with public benefit.

Research & Development at the Department of Energy

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) is uniquely positioned to help solve the challenges AI and data centers pose, as the agency sits at the critical intersection of AI development, high-performance computing, and energy systems. DOE’s national laboratories have been central to advancing AI capabilities: Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) was indeed the first to integrate graphics processing units (GPUs) into supercomputers, pioneering a new era of AI training and modeling capacity. DOE also runs two of the world’s most powerful supercomputers – Aurora at Argonne National Lab and Frontier at ORNL – cementing the U.S.’ leadership in high-performance computing.

Beyond computing, DOE plays a key role in modernizing grid infrastructure, advancing clean energy technologies, and setting efficiency standards for energy-intensive operations like data centers. The agency has also launched programs like the Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence for Science, Security and Technology (FASST), overseen by the Office of Critical and Emerging Tech (CET), to coordinate AI-related activities across its programs.

As the intersection of AI and energy deepens—with AI driving data center expansion and offering tools to manage its impact—DOE must remain at the center of this conversation, and it must continue to deliver. The stakes are high: how we manage this convergence will influence not only the pace of technological innovation but also the equity and sustainability of our energy future.

Incentivizing Incentives: Aligning AI Growth with the Public Good

The U.S. is poised to spend a massive amount of carbon to power the next wave of artificial intelligence. From training LLMs to supporting real-time AI applications, the energy intensity of this sector is undeniable—and growing. That means we’re not just investing financially in AI; we’re investing environmentally. To ensure that this investment delivers public value, we must align political and economic incentives with societal outcomes like grid stability, decarbonization, and real benefits for American communities.

One of the clearest opportunities lies in making data centers more responsive to the needs of the electric grid. While these facilities consume enormous amounts of power, they also hold untapped potential to act as flexible loads—adjusting their demand based on grid conditions to support reliability and integrate clean energy. The challenge? There’s currently little economic incentive for them to do so. One panelist noted skepticism that market structures alone will drive this shift without targeted policy support or regulatory nudges.

Instead, many data centers continue to benefit from “sweetheart deals”—generous tax abatements and economic development incentives offered by states and municipalities eager to attract investment. These agreements often lack transparency and rarely require companies to contribute to local energy resilience or emissions goals. For example, in several states, local governments have offered multi-decade property tax exemptions or reduced electricity rates without any accountability for climate impact or grid contributions.

New AI x Energy Policy Ideas Underway

If we’re going to spend gigatons of carbon in pursuit of AI-driven innovation, we must be strategic about where and how we direct incentives. That means:

- Conditioning public subsidies on data center flexibility and efficiency performance.

- Requiring visibility into private energy agreements and emissions footprints.

- Designing market signals—like time-of-use pricing or demand response incentives—that reward facilities for operating in sync with clean energy resources.

We don’t just need more incentives—we need better ones. And we need to ensure they serve public priorities, not just private profit. Through our AI x Energy Policy Sprint, FAS is working with leading experts to develop promising policy solutions for the Trump administration, Congress, and state and local governments. These policy memos will address how to: mitigate the energy and environmental impacts of AI systems and data centers, enhance the reliability and efficiency of energy systems using AI applications, and unlock transformative technological solutions with AI and energy R&D.

Right now, we have a rare opportunity to shape U.S. policy at the critical intersection of AI and energy. Acting decisively today ensures we can harness AI to drive innovation, revolutionize energy solutions, and sustainably integrate transformative technologies into our infrastructure.

Economic Impacts of Extreme Heat: Energy

As temperatures rise, the strain on energy infrastructure escalates, creating vulnerabilities for the efficiency of energy generation, grid transmission, and home cooling, which have significant impacts on businesses, households, and critical services. Without action, energy systems will face growing instability, infrastructure failures will persist, and utility burdens will increase. The combined effects of extreme heat cost our nation over $162 billion in 2024 – equivalent to nearly 1% of the U.S. GDP.

The federal government needs to prepare energy systems and the built environment through strategic investments in energy infrastructure — across energy generation, transmission, and use. Doing so includes ensuring electric grids are prepared for extreme heat by establishing an interagency HeatSmart Grids Initiative to assess the risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency responses. Congress should retain and expand home energy rebates, tax credits, and the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) to enable deep retrofits that prepare homes against power outages and cut cooling costs, along with extending the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC) to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation.

Challenge & Opportunity: Grid Security

Extreme Heat Reduces Energy Generation and Transmission Efficiency

During a heatwave, the energy grid faces not only surges in demand but also decreased energy production and reduced transmission efficiency. For instance, turbines can become up to 25% less efficient in high temperatures. Other energy sources are also impacted: solar power, for example, produces less electricity as temperatures rise because high heat slows the flow of electrical current. Additionally, transmission lines lose up to 5.8% of their capacity to carry electricity as temperatures increase, resulting in reliability issues such as rolling blackouts. These combined effects slow down the entire energy cycle, making it harder for the grid to meet growing demand and causing power disruptions.

Rising Demand and Grid Load Increase the Threat of Power Outages

Electric grids are under unprecedented strain as record-high temperatures drive up air conditioning use, increasing energy demand in the summer. Power generation and transmission are impeded when demand outpaces supply, causing communities and businesses to experience blackouts. According to data from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), between 2024 and 2028, an alarming 300 million people across the United States could face power outages. Texas, California, the Southwest, New England, and much of the Midwest are among the states and regions most at risk of energy emergencies during extreme conditions, according to 2024 NERC data.

Data center build-out, driven by growing demand for artificial intelligence, cloud services, and big data analytics, further adds stress to the grid. Data centers are estimated to consume 9% of US annual electricity generation by 2030. With up to 40% of data centers’ total yearly energy consumption driven by cooling systems, peak demand during the hottest days of the year puts demand on the U.S. electric grid and increases power outage risk.

Power outages bear significant economic costs and put human lives at severe risk. To put this into perspective, a concurrent heat wave and blackout event in Phoenix, Arizona, could put 1 million residents at high risk of heat-related illness, with more than 50% of the city’s population requiring medical care. As we saw with 2024’s Hurricane Beryl, more than 2 million Texans lost power during a heatwave, resulting in up to $1.3 billion in damages to the electric infrastructure in the Houston area and significant public health and business impacts. The nation must make strategic investments to ensure energy reliability and foster the resilience of electric grids to weather hazards like extreme heat.

Advancing Solutions for Energy Systems and Grid Security

Investments in resilience pay dividends, with every federal dollar spent on resilience returning $6 in societal benefits. For example, the DOE Grid Resilience State and Tribal Formula Grants, established by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), have strengthened grid infrastructure, developed innovative technologies, and improved community resilience against extreme weather. It is essential that funds for this program, as well as other BIL and Inflation Reduction Act initiatives, continue to be disbursed.

To build heat resilience in communities across this nation, Congress must establish the HeatSmart Grids Initiative as a partnership between DOE, FEMA, HHS, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), NERC, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). This program should (i) perform national audits of energy security and building-stock preparedness for outages, (ii) map energy resilience assets such as long-term energy storage and microgrids, (iii) leverage technologies for minimizing grid loads such as smart grids and virtual power plants, and (iv) coordinate protocols with FEMA’s Community Lifelines and CISA’s Critical Infrastructure for emergency response. This initiative will ensure electric grids are prepared for extreme heat, including the risk of energy system failures during extreme heat and the necessary emergency and public health responses.

Challenge & Opportunity: Increasing Household and Business Energy Costs

As temperatures rise, so do household and business energy bills to cover cooling costs. This escalation can be particularly challenging for low-income individuals, schools, and small businesses operating on thin margins. For businesses, especially small enterprises, power outages, equipment failures, and interruptions in the supply chain become more frequent and severe due to extreme weather, negatively affecting production and distribution. One in six U.S. households (21.2 million people) find themselves behind on their energy bills, which increases the risk of utility shut-offs. One in five households report reducing or forgoing food and medicine to pay their energy bills. Families, school districts, and business owners need active and passive cooling approaches to meet demands without increasing costs.

Advancing Solutions for Businesses, Households, and Vital Facilities

Affordably cooled homes, businesses, and schools are crucial to sustaining our economy. To prepare the nation’s housing and infrastructure for rising temperatures, the federal government should:

- Expand the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program, existing rebates and tax credits (including HER, HEAR, 25C, 179D, 45L, Direct Pay) to include passive cooling technology such as cool walls, pavements, and roofs (H.R. 9894). Revise 25C to be refundable at purchase to increase accessibility to low-income households.

- Authorize a Weatherization Readiness Program (H.R. 8721) to address structural, plumbing, roofing, and electrical issues and environmental hazards with dwelling units to make them eligible for WAP.

- Direct the DOE to work with its WAP contractors to ensure home energy audits consider passive cooling interventions, such as cool walls and roofs, strategically placing trees to provide shading and high-efficiency windows.

- Extend the National Initiative to Advance Building Codes (NIABC) to include (i) the development of codes and metrics for sustainable and passive cooling, shade, materials selection, and thermal comfort and (ii) the identification of opportunities to accelerate state and local adoption of code language for extreme heat adaptation. Partner with the National Institute of Standards and Technology to create an Extreme Heat clearinghouse for model building codes.

- Authorize an extension to the DOE Renew America’s Schools Program to continue funding cost-saving, energy-efficient upgrades in K-12 schools.

- Provide supportive appropriations to heat-critical programs at DOE, including: the Affordable Home Energy Shot, State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP), Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED), Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy (DOE), and the Home Energy Rebates program

The Federation of American Scientists: Who We Are

At the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), we envision a world where the federal government deploys cutting-edge science, technology, ideas, and talent to solve and address the impacts of extreme heat. We bring expertise in embedding science, data, and technology into government decision-making and a strong network of subject matter experts in extreme heat, both inside and outside of government. Through our 2025 Heat Policy Agenda and broader policy library, FAS is positioned to help ensure that public policy meets the challenges of living with extreme heat.

Consider FAS a resource for…

- Understanding evidence-based policy solutions

- Directing members and staff to relevant academic research

- Connecting with issue experts to develop solutions that can immediately address the impacts of extreme heat

We are tackling this crisis with initiative, creativity, experimentation, and innovation, serving as a resource on environmental health policy issues. Feel free to always reach out to us:

Emerging Technologies

Resilient Communities,

Extreme Weather,

Inclusive Innovation & Technology

The DOE Office Already Unleashing American Energy Dominance

President Trump’s executive order “Unleashing American Energy” promises an American economic revival based on lower costs, bringing back our supply chains, building America into a manufacturing superpower again, and cutting reliance on countries. Within this order he tasks the Secretary of Energy to prioritize programs to onshore critical mineral processing and development. Luckily, a little-known office at the Department of Energy (DOE) – the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC) – is already at the heart of that agenda.

MESC and the Manufacturing Renaissance

Energy manufacturing in the U.S. is experiencing a historic momentum, thanks in large part to the Department of Energy. Manufacturing was the backbone of the 20th century U.S. economy, but recent decades have seen a dramatic offshoring of domestic supply chains, in particular to China, that has threatened U.S. economic and national security. With the global supply chain crises of the early 2020s, driven by COVID and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Congress finally took note. Through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, CHIPS and Science Act, and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), lawmakers gave the federal government first-of-a-kind tools to reassert U.S. leadership in global manufacturing. This included creating, in 2021, a program (MESC) at the DOE that focuses on critical energy supply chains, including critical minerals.

Created in 2022 after the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law that infused DOE with new funds to reshore advanced energy manufacturing, the Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains (MESC) has been hard at work executing on reshoring manufacturing. Since inception, MESC has achieved a remarkable impact on the energy supply chain and manufacturing industry in the US. It has resulted in over $39 billion of investments from both the public and private sector into the American energy sector in companies that have created over 47,000 private sector jobs. Many of these jobs and companies that have been funded are for critical minerals development and processing.

MESC will be central to the energy dominance mission at the core of President Trump’s playbook along with Energy Secretary Chris Wright.

Why MESC is Crucial for Energy Dominance

MESC’s funding for energy infrastructure will be critical to American energy dominance and to address the energy crisis declaration that Trump signed on day one in office. Projects funded through this office include critical minerals and battery manufacturing necessary to compete with China, and grid modernization technology to ensure Americans have access to reliable and affordable power. For example, Ascend Elements was awarded two grants totaling $480M to build new critical minerals and battery recycling programs in Hopkinsville, Kentucky. This grant will yield an estimated $4.4 billion in economic activity and over 400 jobs for Hopkinsville. Sila Technologies was granted $100M for a silicon anode production facility in Moses Lake, Washington, which will be used in hundreds of thousands of automobiles, and strengthening the regional economy

The Trump administration can build on these successes and break new ground along the way:

- Work with congress to permanently establish MESC with statutory authority and permanent appropriated funds.

- Continue funding projects that will result in a resilient domestic energy supply, including projects to update our grid infrastructure and those that will create new jobs in energy technologies like critical minerals processing and battery manufacturing.

- Use DOE’s Other Transaction Authority (OTA) to ensure prices for critical minerals and other energy manufacturing technologies that are primarily created or manufactured in China or other foreign entities of concern are profitable for companies, and affordable for customers.

Cost-conscious citizens should enthusiastically support these efforts because MESC has already proven its capability to punch above its weight. By making funding more permanent, Congress can 10x or more the speed and scale with which we assert energy dominance.

MESC is small but mighty. Its importance to continuing U.S. dominance in energy manufacturing cannot be overstated. Despite that, its funding in the budget is not permanent. The Trump administration has an opportunity to supercharge American energy dominance through MESC, but they must come together with Congressional leaders to permanently establish MESC and its mission. 2025 is an opportunity for new leaders to invest in creating American manufacturing jobs and spur innovation in the energy sector.

Energy Dominance (Already) Starts at the DOE

Earlier this week, the Senate confirmed Chris Wright as the Secretary of Energy, ushering in a new era of the Department of Energy (DOE). In his opening statement before Congress, Wright laid out his vision for the DOE under his leadership—to unleash American energy and restore “energy dominance”, lead the world in innovation by accelerating the work of the National Labs, and remove barriers to building energy projects domestically. Prior to Wright’s nomination, there have already been a range of proposals circulating for how, exactly, to do this.

Of these, a Trump FERC commissioner calls for the reorganization – a complete overhaul – of the DOE as-is. This proposed reorganization would eliminate DOE’s Office of Infrastructure, remove all applied energy programs, strip commercial technology and deployment funding, and rename the agency to be the Department of Energy Security and Advanced Science (DESAS).

This proposal would eliminate crucial DOE offices that are accomplishing vital work across the country, and would give the DOE an unrecognizable facelift. Like other facelifts, the effort would be very costly – paid for by the American taxpayer, unnecessary, and a waste of public resources. Further, reorganizing DOE will waste the precious time and money of the Federal government, and mean that DOE’s incoming Secretary, Chris Wright, will be less effective in accomplishing the goals the President campaigned on – energy reliability, energy affordability, and winning the competition with China. The good news for the Trump Administration is that DOE’s existing organization structure is already well-suited and well-organized to pursue its “energy dominance” agenda.

The Cost of Reorganizing

Since its inception in 1977, the Department of Energy has evolved several times in scope and focus to meet the changing needs of the nation. Each time, there was an intent and purpose behind the reorganization of the agency. For example, during the Clinton Administration, Congress restructured the nuclear weapons program into the semi-autonomous National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) to bolster management and oversight.

More recently, in 2022, another reorganization was driven by the need to administer major new Congressionally-authorized programs and taxpayer funds effectively. With the enactment of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), DOE combined existing programs, like the Loan Programs Office, with newly-authorized offices, like the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED). This structure allows DOE to hone a new Congressionally-mandated skill set – demonstration and deployment – while not diluting its traditional competency in managing fundamental research and development.

Even when they make sense, reorganizations have their risks, especially in a complex agency like the DOE. Large-scale changes to agencies inherently disrupt operations, threaten a loss of institutional knowledge, impair employee productivity, and create their own legal and bureaucratic complexities. These inherent risks are exacerbated even further with rushed or unwarranted reorganizations.

The financial costs of reorganizing a large Federal agency alone can be staggering. Lost productivity alone is estimated in the millions, as employees and leadership divert time and focus from mission-critical projects to logistical changes, including union negotiations. These efforts often drag on longer than anticipated, especially when determining how to split responsibilities and reassign personnel. Studies have shown that large-scale reorganizations within government agencies often fail to deliver promised efficiencies, instead introducing unforeseen costs and delays.

These disruptions would be compounded by the impacts an unnecessary reorganization would have on billions of dollars in existing DOE projects already driving economic growth, particularly in rural and often Republican-led districts, which depend on the DOE’s stability to maintain these investments. Given the high stakes, policymakers have consistently recognized the importance of a stable DOE framework to achieve the nation’s energy goals. The bipartisan passage of the 2020 Energy Act in the Senate reflects a shared understanding that DOE needs a well-equipped demonstration and deployment team to advance energy security and achieve American energy dominance.

DOE’s Existing Structure is Already Optimized to Pursue the Energy Dominance Agenda

In President Trump’s second campaign for office, he ran on a platform of setting up the U.S. to compete with China, to improve energy affordability and reliability for Americans, and to address the strain of rising electricity demand on the grid by using artificial intelligence (AI). DOE’s existing organization structure is already optimized to pursue President Trump’s ‘energy dominance’ agenda, most of which being implemented in Republican-represented districts.

Competition with China

As mentioned above, in response to the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), DOE created several new offices, including the Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains Office (MESC) and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED). Both of these offices are positioning the U.S. to compete with China by focusing on strengthening domestic manufacturing, supply chains, and workforce development for critical energy technologies right here at home.

MESC is spearheading efforts to establish a secure battery manufacturing supply chain within the U.S. In September 2024, the Office announced plans to deliver over $3 billion in investments to more than 25 battery projects across 14 states. The portfolio of selected projects, once fully contracted, are projected to support over 8,000 construction jobs and over 4,000 operating jobs domestically. These projects encompass essential critical mineral processing, battery production, and recycling efforts. By investing in domestic battery infrastructure, the program reduces reliance on foreign sources, particularly China, and enhances the U.S.’s ability to compete and lead on a global scale.

In passing BIL, Congress understood that to compete with China, R&D alone is not sufficient. The United States needs to be building large-scale demonstrations of the newest energy technologies domestically. OCED is ensuring that these technologies, and their supply chains, reach commercial scale in the U.S. to directly benefit American industry and energy consumers. OCED catalyzes private capital by sharing the financial risk of early-stage technologies which speeds up domestic innovation and counters China’s heavy state-backed funding model. In 2024 alone, OCED awarded 91 projects, in 42 U.S. states, to over 160 prize winners. By supporting first-of-a-kind or next-generation projects, OCED de-risks emerging technologies for private sector adoption, enabling quicker commercialization and global competitiveness. With additional or existing funding, OCED could create next-generation geothermal and/or advanced nuclear programs that could help unlock the hundreds of gigawatts of potential domestic energy from each technology area.

Energy Affordability and Reliability

Another BIL-authorized DOE office, the Grid Deployment Office (GDO), is playing a crucial role in improving energy affordability and reliability for Americans through targeted investments to modernize the nation’s power grid. GDO manages billions of dollars in funding under the BIL to improve grid resilience against wildfires, extreme weather, cyberattacks, and other disruptions. Programs like the Grid Resilience and Innovation Partnerships (GRIP) Program aim to enhance the reliability of the grid by supporting state-of-the-art grid infrastructure upgrades and developing new solutions to prevent outages and speed up restoration times in high-risk areas. The U.S. is in dire need of new transmission to keep costs low and maintain reliability for consumers. GDO is addressing the financial, regulatory, and technical barriers that are standing in the way of building vital transmission infrastructure.

The Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP), also part of the Office of Infrastructure, supports energy projects that help upgrade local government and residential infrastructure and lower household energy costs. Investments from BIL and IRA funding have already been distributed to states and communities, and SCEP is working to ensure that this taxpayer money is used as effectively as possible. For example, SCEP administers the Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP), which helps Americans in all 50 states improve energy efficiency by funding upgrades like insulation, window replacements, and modern heating systems. This program typically saves households $283 or more per year on energy costs.

Addressing Load Growth by Using AI

The DOE’s newest office, the Office of Critical and Emerging Tech (CET), leads the Department’s work on emerging areas important to national security like biotechnology, quantum, microelectronics, and artificial intelligence (AI). In April, CET partnered with several of DOE’s National Labs to produce an AI for Energy report. This report outlines DOE’s ongoing activities and the near-term potential to “safely and ethically implement AI to enable a secure, resilient power grid and drive energy innovation across the economy, while providing a skilled AI-ready energy workforce.”

In addition to co-authoring this publication, CET partners with national labs to deploy AI-powered predictive analytics and simulation tools for addressing long-term load growth.

By deploying AI to enhance forecasting, manage grid performance, and integrate innovative energy technologies, CET ensures that the U.S. can handle our increasing energy demands while advancing grid reliability and resiliency.

The Path Forward

DOE is already very well set up to pursue an energy dominance agenda for America. There’s simply no need to waste time conducting a large-scale agency reorganization.

In a January 2024 Letter from the CEO, Chris Wright discusses his “straightforward business philosophy” for leading a high-functioning company. As a leader, he strives to “Hire great people and treat them like adults…” which makes Liberty Energy, his company, “successful in attracting and retaining exceptional people who together truly shine.” Secretary Wright knows how to run a successful business. He knows the “secret sauce” lies in employee satisfaction and retention.

To apply this approach in his new role, Wright should resist tinkering with DOE’s structure, and instead, give employees a vision, and get off to the races of achieving the American energy dominance agenda without wasting time, the public’s money, and morale. Instead of redirecting resources to reorganizations, the DOE’s ample resources and existing program infrastructure should be harnessed to pursue initiatives that bolster the nation’s energy resilience and cut costs. Effective governance demands thoughtful consideration and long-term strategic alignment rather than hasty or superficial reorganizations.

Launch the Next Nuclear Corps for a More Flexible Nuclear Regulatory Commission

The Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), the Nation’s regulator of civilian nuclear technologies, should shift agency staff, resources, and operations more flexibly based on emergent regulatory demands. The nuclear power industry is demonstrating commercialization progress on new reactor concepts that will challenge the NRC’s licensing and oversight functions. Rulemaking on new licensing frameworks is in progress, but such regulation will fall short without changes to the NRC’s staffing. Since the NRC is exempt from civil service laws under the Atomic Energy Act (AEA) of 1954, the agency should use AEA flexible hiring authorities to launch the Next Nuclear Corps, a staffing program to shift capacity based on emergent, short-term workforce needs. The NRC should also better enable hiring managers to meet medium-term workforce needs by clarifying guidance on NRC’s direct hire authority.

Challenge and Opportunity

Policymakers, investors, and major energy users, such as data centers and industrial plants, are interested in new nuclear power because it promises unique value. New nuclear power technologies could add either additional base load or variable power to electrical systems. Small modular or micro reactors could provide independent power to military bases, many of which are connected to power grids and vulnerable to disruption. Local governments can stimulate economies with high-paying and safe jobs at nuclear plants. The average nuclear power plant also has the lowest lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions compared to other available electricity-generating technologies, including wind, solar, and hydropower. Current efforts to expand nuclear power are different from those of the 1970s and 1980s, the most recent decades of significant building. Proposals today include building plants designed similarly to plants of those decades or even restarting power operations at up to three closed plants; but more activity is focused on commercializing advanced and small modular reactors, diverse concepts incorporating innovations in reactor design, fuel types, and safety systems. The government has partnered with private companies to develop and demonstrate advanced reactors since the inception of nuclear technology in the 1950s, but today several companies demonstrate advanced technical and business progress toward commercialization.

Innovation in nuclear power challenges the NRC’s status-quo approaches to licensing and oversight. Rulemaking on new regulatory frameworks is necessary and in progress, but changes to the agency’s staffing and operations are also needed. Over time, Congress, the President, and the Commission itself have adjusted the agency’s operations in response to shifts in international postures, comprehensive national energy plans, and accidents or emerging threats at nuclear plants, but the NRC’s ability to respond to sudden changes in the nuclear industry is a long-standing challenge. To become more flexible, NRC initiated Project Aim in 2014 after expectations of significant industry growth, spurred in part by tax incentives in the Energy Policy Act of 2005, were not realized due to record-low natural gas prices. More recent assessments from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and NRC Office of Inspector General (OIG) acknowledge the challenge of workload forecasting in an unpredictable nuclear industry, but counterintuitively, some recommendations focus on improving the ability to workforce plan two years or more in advance. Renewed expectations of growth, spurred by interest from policymakers and energy customers, reinforces a point from the 2015 Project Aim final report that, “…effectiveness, efficiency, agility, flexibility, and performance must improve for the agency to continue to succeed in the future.”

Congress also called on the NRC to become more responsive to current developments as expressed in legislation enacted with bipartisan support. Across the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 and the ADVANCE Act of 2024, Congress requires the NRC to update its mission statement to better reflect the benefits of civilian nuclear technology, establish regulatory frameworks for new technology, streamline environmental review, incentivize licensing of advanced nuclear technologies, and position itself and the United States as a leader in civilian nuclear power. Meeting expectations requires significant operational and workforce changes. Since NRC is exempt from civil service laws and operates an independent competitive merit system, widespread changes to the agency’s hiring practices will be determined by future Commissioners, including the President’s selection of Chair (and by extension, the Chair’s selection of the Executive Director for Operations (EDO)), and modifications to agreements between the NRC and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM). In the meantime, NRC is well equipped to increase hiring flexibility using authorities from existing law and regulations.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. The NRC EDO should launch the Next Nuclear Corps, a staffing program dedicated to shifting agency capacity based on short-term workforce needs.

The EDO should hire a new director to lead the Corps. The Corps director should report to the EDO and consult with the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer (OCHCO) and division heads to develop Corps positions to address near-term priorities in competency areas that do not require in-depth training. Near-term priorities should be informed by the NRC’s existing yearly capacity assessments, but the Corps director should also rely on direct expertise and insights from branch chiefs who have a real-time understanding of industry activity and staffing challenges.

Recommendation 2. Hiring for the Corps should be executed under the special authority to appoint directly to the excepted service under 161B(a) of the Atomic Energy Act (AEA).

The ADVANCE Act of 2024 created new categories of hires to fill critical needs related to licensing, oversight, and matters related to NRC efficiency. The EDO should execute the Corps under the new authorities in section 161B(a) of the AEA as it provides clear direction and structure for the EDO to make personnel appointments outside of the NRC’s independent competitive merit system described in Management Directive 10.1. 161B(a)(A) provides up to 210 hires at any time and 161B(a)(B) provides up to 20 additional hires each fiscal year which are limited to a term of four years. The standard service term should be one year as near-term workforce needs may be temporary because of the nature of the position or uncertainty in future demand.

The EDO should adopt the following practices to allow renewals of some positions from the prior year without reaching the limits described in the AEA:

- 161B(a)(A): Appoint up to 140 new staff each fiscal year and consider staggering appointments to address capacity needs that arise later in the year. After the initial one-year term, up to half of the positions should be eligible for a one-year renewal if the need continues. After the initial cohort off-boards, an additional 140 new staff should be appointed alongside up to 70 renewed staff from the prior cohort without exceeding the maximum of 210 appointments at any time.

- 161B(a)(B): Appoint up to 20 new staff each fiscal year and consider staggering appointments to address capacity needs that arise later in the year. All positions should be eligible for a one-year renewal for up to three additional years if the need continues.

Recommendation 3. The EDO should update Management Directives 10.13 and 10.1 to contain or reference the standard operating procedure for NRC’s mirrored version of OPM’s Direct Hire Authority.

The proposed Corps addresses emergent, short-term capacity needs, but internal policy clarity is needed to solve medium-term hiring challenges for hard-to-recruit positions. As far back as 2007, NRC hiring managers and human resources reported that DHA was highly desired for hiring flexibility. The NRC OIG closed Recommendation 2.1 from Audit of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s Vacancy Announcement Process in June 2024 because NRC updated Standard Operating Procedure for Direct Hire Authority with more details. However, management directives are the primary policy and procedure documents that govern the NRC’s internal functions. The EDO should update management directives to formally capture or reference this procedure so that NRC staff are better equipped to use DHA. Specifically, the EDO should:

- amend Management Directive 10.13 Special Employment Programs to add Section IX. Direct Hire Authority, that formalizes the procedure in the Standard Operating Procedure for Direct Hire Authority

- update Management Directive 10.1, Section I.A. to reference the amended Management Directive 10.13 as the general policy for non-competitive hiring

Conclusion

The potential of new nuclear power plants to meet energy demand, increase energy security, and revitalize local economies depends on new regulatory and operational approaches at the NRC. Rulemaking on new licensing frameworks is in progress, but the NRC should also use AEA flexible hiring authorities to address emergent, short-term workforce needs that may be temporary based on shifting industry developments. The proposed Corps structure allows the EDO to quickly hire new staff outside of the agency’s competitive merit system for short-term needs while preserving flexibility to renew appointments if the capacity needs continue. For permanent hard-to-recruit positions, the EDO should clarify guidance for hiring managers on direct hire authority. The NRC is well equipped with existing authorities to meet emergent regulatory demand and renewed expectations of nuclear power growth.

This action-ready policy memo is part of Day One 2025 — our effort to bring forward bold policy ideas, grounded in science and evidence, that can tackle the country’s biggest challenges and bring us closer to the prosperous, equitable and safe future that we all hope for whoever takes office in 2025 and beyond.

PLEASE NOTE (February 2025): Since publication several government websites have been taken offline. We apologize for any broken links to once accessible public data.

The Corps director should create positions informed by the expertise and insights from agency leaders who have a real-time understanding of industry activity and present staffing challenges. Positions should cover all career levels and cover competency areas that do not require in-depth internal training or security clearances. The Corps should fill new positions created for special roles in support of other staff or teams, such as special coordinators, specialists, and consultants.

The Corps is not a graduate-level fellowship or leadership development program. The Corps is specifically for short-term, rapid hiring based on emergent capacity needs that may be temporary based on the nature of the need or uncertainty in future demand.

The Corps structure includes flexibility for a limited number of renewals, but it is not intended to recruit for permanent positions. Supervisors and hiring managers could choose to coordinate with the OCHCO to recruit off-boarding Corps members to other employment opportunities.

The Corps director can identify talent through existing NRC recruiting channels, such as job fairs, universities, and professional associations, however, the Corps director should also establish new recruiting efforts through more competitive channels. Because the positions are temporary, the Corps can recruit from more competitive talent pools, such as talent seeking long term careers in private industry. Job seekers with long-term ambitions in the private nuclear sector and the NRC could both benefit from a one- or two-year period of service focused on a specific project.

Promoting Fusion Energy Leadership with U.S. Tritium Production Capacity

As a fusion energy future becomes increasingly tangible, the United States should proactively prepare for it if/when it arrives. A single, commercial-scale fusion reactor will require more tritium fuel than is currently available from global civilian-use inventories. For fusion to be viable, greater-than-replacement tritium breeding technologies will be essential. Before the cycle of net tritium gain can begin, however, the world needs sufficient tritium to complete R&D and successfully commission first-of-a-kind (FOAK) fusion reactors. The United States has the only proven and scalable tritium production supply chain, but it is largely reserved for nuclear weapons. Excess tritium production capacity should be leveraged to ensure the success of and U.S. leadership in fusion energy.

The Trump administration should reinforce U.S. investments and leadership in commercial fusion with game changing innovation in the provision of tritium fuel. The Congressional Fusion Energy Caucus has growing support in the House with 92 members and an emerging Senate counterpart chaired by Sen. Martin Heinrich. Energy security and independence are important areas of bipartisan cooperation, but strong leadership from the White House will be needed to set a bold, America-first agenda.

Challenge and Opportunity

Fusion energy R&D currently relies on limited reserves of tritium from non-scalable production streams. These reserves reduce by ~5% each year due to radioactive decay, which makes stockpiling difficult. One recent estimate suggests that global stocks of civilian-use tritium are just 25–30kg, while commissioning and startup of a single commercial fusion reactor may require up to 10kg. The largest source of civilian-use tritium is Canada, which produces ~2kg/yr as a byproduct of heavy water reactor operation, but most of that material is intended to fuel the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) in the next decade. This tritium production is directly coupled to the power generation rate of its fleet of Canadian Deuterium Uranium (CANDU) reactors; therefore, the only way to increase the tritium production rate is to build more CANDU power reactors.