Regulating US Air Force Contacts with China

The U.S. Air Force last week issued updated guidance both to foster and to limit contacts with Chinese military personnel, based in part on classified Defense Department directives.

“With the rise of PRC influence in the international community and the increasing capabilities of the Chinese military, Air Force military-to-military relationship with the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), and the People’s Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) is becoming more crucial than before,” the Air Force document stated.

See Conduct of USAF Contacts with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Government of the Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) of the PRC, Air Force Instruction 16-118, August 5, 2015.

The Instruction provides a framework for conducting reciprocal US-PRC visits to each other’s military installations.

“The success of these visits, whether US or PRC-led, directly affects relationships between the US and the PRC, as well as our relationships with our allies and partners, and is thereby important in support of national and regional politico-military objectives.”

But the Instruction also identifies numerous topical areas that are likely to be off-limits for USAF-PRC military contacts.

“[P]rohibited contacts… may involve: force projection operations, nuclear operations, advanced combined-arms and joint combat operations, advanced logistical operations, chemical and biological defense and other capabilities related to weapons of mass destruction, surveillance and reconnaissance operations, joint war-fighting experiments and other activities related to a transformation in warfare, military space operations, other advanced capabilities of the armed forces, arms sales or military-related technology transfers, release of classified or restricted information, and access to a DoD laboratory.”

The new USAF Instruction implements two classified DoD Instructions, which have not been released: Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) C-2000.23, Conduct of DoD Contacts with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and DoDI S-2000.24, Conduct of DoD Contacts with the Government of Hong Kong, Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) of the PRC.

The Congressional Research Service produced a related report on U.S.-China Military Contacts: Issues for Congress, updated October 27, 2014.

China’s Science of Military Strategy (2013)

Updated below

In 2013, the Academy of Military Sciences of the People’s Liberation Army of China issued a revised edition of its authoritative, influential publication “The Science of Military Strategy” (SMS) for the first time since 2001.

“Each new edition of the SMS is closely scrutinized by China hands in the West for the valuable insights it provides into the evolving thinking of the PLA on a range of strategically important topics,” wrote Joe McReynolds of the Jamestown Institute.

A copy of the 2013 edition of the Science of Military Strategy — in Chinese — was obtained by Secrecy News and is posted on the Federation of American Scientists website (in a very large PDF).

“The availability of this document could be a huge boon for young China analysts who have not yet had the chance to buy their own copy in China or Taiwan,” said one China specialist.

An English translation of the document has not yet become publicly available.

But an overview of its treatment of nuclear weapons policy issues was provided in a recent essay by Michael S. Chase of the Jamestown Institute.

“Compared to the previous edition of SMS, the 2013 edition offers much more extensive and detailed coverage of a number of nuclear policy and strategy-related issues,” Mr. Chase wrote.

In general, SMS 2013 “reaffirms China’s nuclear No First Use policy…. Accordingly, any Chinese use of nuclear weapons in actual combat would be for ‘retaliatory nuclear counterstrikes’.”

With respect to deterrence, SMS 2013 states that “speaking with a unified voice from the highest levels of the government and military to the lowest levels can often enhance deterrence outcomes. But sometimes, when different things are said by different people, deterrence outcomes might be even better.”

SMS 2013 also notably included the first explicit acknowledgement of Chinese “network attack forces” which perform what the U.S. calls “offensive cyber operations.”

In a separate essay on “China’s Evolving Perspectives on Network Warfare: Lessons from the Science of Military Strategy,” Joe McReynolds wrote that the SMS authors “focus heavily on the central role of peacetime ‘network reconnaissance’ — that is, the technical penetration and monitoring of an adversary’s networks — in developing the PLA’s ability to engage in wartime network operations.”

On July 28, the Congressional Research Service updated its report on China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities — Background and Issues for Congress.

Update: The Union of Concerned Scientists has published a detailed review of the 2013 Science of Military Strategy, including translations of some key passages.

Pentagon Report: China Deploys MIRV Missile

By Hans M. Kristensen

The biggest surprise in the Pentagon’s latest annual report on Chinese military power is the claim that China’s ICBM force now includes the “multiple independently-targetable re-entry vehicle (MIRV)-equipped Mod 3 (DF-5).”

This is (to my knowledge) the first time the US Intelligence Community has made a public claim that China has fielded a MIRVed missile system.

If so, China joins the club of four other nuclear-armed states that have deployed MIRV for decades: Britain, France, Russia and the United States.

For China to join the MIRV club strains China’s claim of having a minimum nuclear deterrent. It is another worrisome sign that China – like the other nuclear-armed states – are trapped in a dynamic technological nuclear arms competition.

A Little Chinese MIRV History

There have been rumors for many years that China was working on MIRV technology. Some private analysts have even claimed – incorrectly – that China had developed MIRV for the DF-31 ICBM and JL-2 SLBM.

Fifteen years ago, CIA’s National Intelligence Estimate on foreign missile developments concluded that “China has had the technical capability to develop multiple RV payloads for 20 years. If China needed a multiple-RV (MRV) capability in the near term, Beijing could use a DF-31-type RV to develop and deploy a simple MRV or multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV) for the CSS-4 in a few years.” (For a review of earlier information and assessments, see here.)

The Pentagon echoed this conclusion in July 2002, when it stated that any Chinese multiple warhead capability will “most likely [be] for the CSS-4.”

Chinese MIRVing of a mobile ICBM such as the DF-31 “would be many years off” the CIA told Congress. This was also the conclusion of the CIA’s National Intelligence Estimate in 2001, which concluded that “Chinese pursuit of a multiple RV capability for its mobile ICBMs and SLBMs would encounter significant technical hurdles and would be costly.”

A DF-5 ICBM is launched from a silo. The Pentagon says China has equipped some of its DF-5s with MIRV.

In an exchange with Senator Cochran in 2002, CIA’s Robert Walpole explained that MIRVing a mobile ICBM would require a much smaller warhead and possibly require nuclear testing:

Sen. Cochran. How many missiles will China be able to place multiple reentry vehicles on?

Mr. Walpole. In the near term, it would be about 20 CSS-4s that they have, the big, large ICBMs. The mobile ICBMs are smaller and it would require a very small warhead for them to put multiple RVs on them.

Sen. Cochran. … [D]o you think that China will attempt to develop a multiple warhead capability for its new missiles?

Mr. Walpole. Over time they may look at that. That would probably require nuclear testing to get something that small, but I do not think it is something that you would see them focused on for the near term.

What makes the Pentagon’s report on the MIRVed DF-5A payload noteworthy is that it was not included in several other intelligence assessments published in the past few months: the prepared threat assessment by the Director of National Intelligence; the prepared threat assessment by the Defense Intelligence Agency; and STRATCOM’s prepared testimony.

Nor were a MIRVed DF-5A mentioned in the Pentagon’s report from 2014 or the Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) report from July 2013.

The Pentagon report also repeats an earlier assertion that “China also is developing a new road-mobile ICBM, the CSS-X-20 (DF-41), possibly capable of carrying MIRVs.” STRATCOM commander Admiral Cecil Haney also mentioned this, saying China is “developing a follow-on mobile system capable of carrying multiple warheads.”

“Possibly capable of” and “capable of” are not equal assessments; the first includes uncertainty, the second does not. Assuming CIA’s prediction from 15 years ago is correct, the DF-5 MIRV payload might consist of three warheads developed for the DF-31/31A.

Whatever the certainty, the MIRVed version of the DF-5 – which I guess we could call DF-5B – is not thought to be loaded with warheads under normal circumstances. In a crisis, the warheads would first have to be brought out of storage and mated with the missile.

Moreover, The Pentagon lists two versions of the DF-5 deployed: the DF-5A (CSS-4 Mod 2) and the new DF-5 MIRV (CSS-4 Mod 3). So only a portion of the 20 missiles in as many silos apparently have been equipped for MIRV.

Why Chinese MIRV?

The big question is why the Chinese leadership has decided to deploy MIRV on the silo-based, liquid-fuel DF-5A.

Chinese officials have for many years warned, and US officials have predicted, that advanced US non-nuclear capabilities such as missile defense systems could cause China to deploy MIRV on some of its missiles. The Pentagon report repeats this analysis by stating that China’s “new generation of mobile missiles, with warheads consisting of MIRVs and penetration aids, are intended to ensure the viability of China’s strategic deterrent in the face of continued advances in U.S. and, to a lesser extent, Russian strategic ISR, precision strike, and missile defense capabilities.”

Conclusions

Chinese MIRV on the DF-5 ICBM is a bad day for nuclear constraint.

Seen in the context of China’s other ongoing nuclear modernization programs – deployment of several types of mobile ICBMs and a new class of sea-launched ballistic missile submarines – the deployment of a MIRVed version of the DF-5 ICBM reported by the Pentagon’s annual report strains the credibility of China’s official assurance that it only wants a minimum nuclear deterrent and is not part of a nuclear arms race.

MIRV on Chinese ICBMs changes the calculus that other nuclear-armed states will make about China’s nuclear intensions and capacity. Essentially, MIRV allows a much more rapid increase of a nuclear arsenal than single-warhead missile. If China also develops MIRV for a mobile ICBM, then it would further deepen that problem.

To its credit, the Chinese nuclear arsenal is still much smaller than that of Russia and the United States. So this is not about a massive Chinese nuclear buildup. Yet the development underscores that a technological nuclear competition among the nuclear-armed states is in full swing – one that China also contributes to.

Although it is still unclear what has officially motivated China to deploy a MIRVed version of the DF-5 ICBM now, previous Chinese statements and US intelligence assessments indicate that it may be a reaction to the US development and deployment of missile defense systems that can threaten China’s ability to retaliate with nuclear weapons.

If so, how ironic that the US missile defense system – intended to reduce the threat to the United States – instead would seem to have increased the threat by triggering development of MIRV on Chinese ballistic missiles that could destroy more US cities in a potential war.

The deployment of a MIRVed DF-5 also raises serious questions about China’s strategic relationship with India. The Pentagon report states that in addition to US missile defense capabilities, “India’s nuclear force is an additional driver behind China’s nuclear force modernization.” There is little doubt that Chinese MIRV has the potential to nudge India into the MIRV club as well.

Indian weapons designers have already hinted that India may be working on its own MIRV system and the US Defense Intelligence Agency recently stated that “India will continue developing an ICBM, the Agni-VI, which will reportedly carry multiple warheads.”

If Chinese MIRV triggers Indian MIRV it would deepen nuclear competition between the two Asian nuclear powers and reduce security for both. This calls for both countries to show constraint but it also requires the other MIRVed nuclear-armed states (Britain, France, Russia and the United States) to limit their MIRV and offensive nuclear warfighting strategies.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Is China Planning To Build More Missile Submarines?

By Hans M. Kristensen

Is China increasing production of nuclear ballistic missile submarines?

Over the past few months, several US defense and intelligence officials have stated for the record that China is planning to build significantly more nuclear-powered missile submarines than previously assumed.

This would potentially put a bigger portion of China’s nuclear arsenal out to sea, a risky proposition, and further deepen China’s unfortunate status as the only nuclear-armed state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation that is increasing it nuclear arsenal.

US Projections For Chinese SSBNs

China does not provide information about how many nuclear submarines it plans to build, but US government officials and agencies occasionally give projections.

The most recent comes from the commander of US Pacific Command (PACOM), Admiral Samuel Locklear, who in his prepared testimony to the US Congress earlier this month stated that in addition to the three Jin-class SSBNs currently in operation, “up to five more may enter service by the end of the decade.”

PACOM Commander Admiral Samuel Lochlear, seen here shaking hands with Chinese defense minister Liang Guanglie in Beijing in 2012, says that China may be building up to eight ballistic missile submarines.

National Intelligence Director James Clapper was a little less specific in his testimony to the Senate in February when he predicted that China “might produce additional Jin-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines.”

The Pentagon’s annual report on Chinese military issues from June 2014 stated that three Jin-class SSBNs (Type-094) were operational and that “up to five may enter service before China proceeds to its next generation SSBN (Type-096) over the next decade.” That projection was not seen as implying that five additional SSBNs would be produced but that a total of five might be built. But in hindsight it could of course be seen as similar projection as the latest PACOM statement.

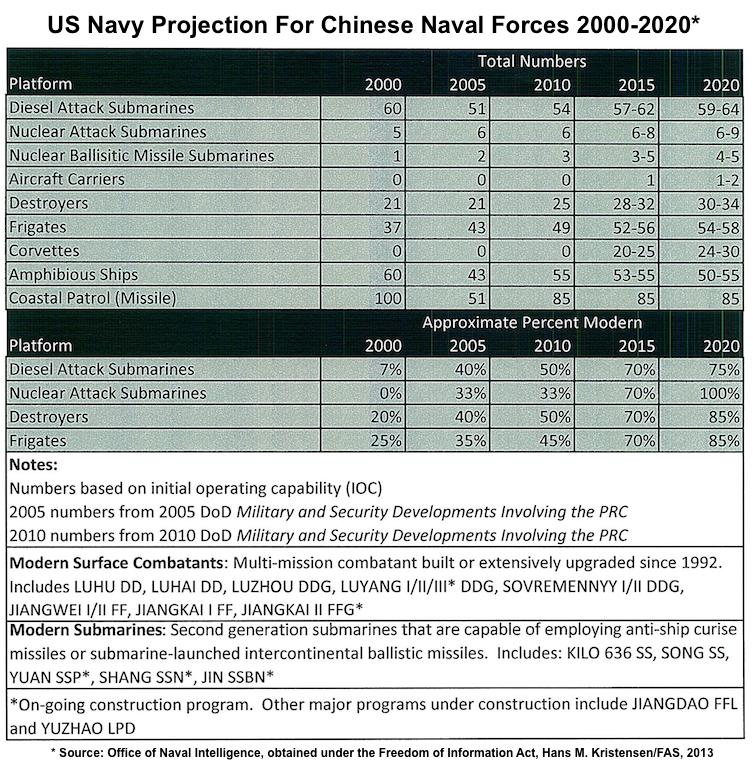

PACOM’s projection of “up to five” additional Jin-class SSBNs is a doubling of the projection of “4-5” SSBNs that the Office of Naval Intelligence made in 2013. That projection followed the first estimate from late-2006 of “a fleet of probably five” submarines.

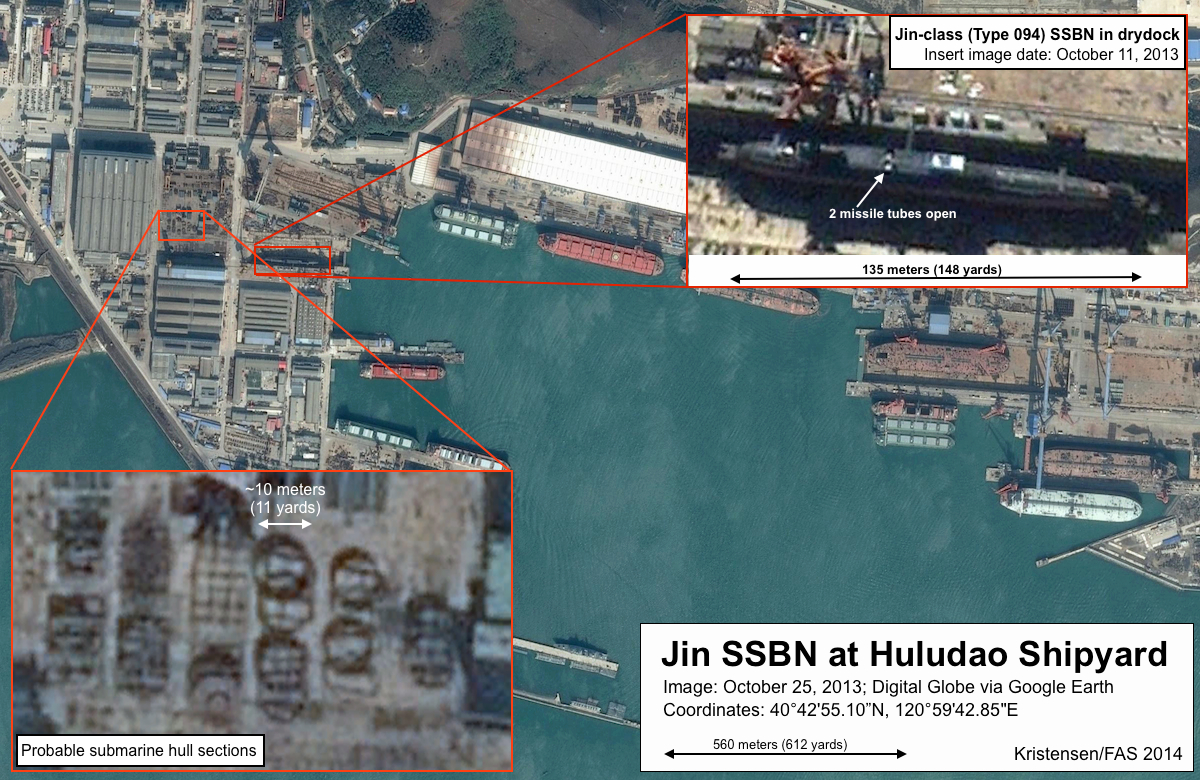

Production of five additional SSBNs by the end of the decade would require fielding one SSBN per year for the next five years, a production pace that China has yet to demonstrate. The first three Jin SSBNs took more than a decade to complete and a fourth boat is rumored to have started sea trials in 2014. The fourth SSBN might be the one seen on commercial satellite images in the dry dock at Huludao in October 2013.

Google Earth images from 2014 and 2015 do not show SSBNs at Huludao, only attack submarines. However, unassembled 10-meter diameter hull sections seen at the shipyard in December 2014 indicate that construction of additional Jin SSBN hulls may be underway (see image below).

Although no Jin-class SSBN has been visible at Huludao shipyard on Google Earth since October 2013, possible Jin-class hull sections seen later indicate additional construction. Click on image to see full size.

Although no Jin-class SSBN has been visible at Huludao shipyard on Google Earth since October 2013, possible Jin-class hull sections seen later indicate additional construction. Click on image to see full size.

Potential Effect on Nuclear Arsenal

Construction of additional Jin SSBNs obviously would have implications for the size of China’s nuclear arsenal. With each submarine capable of carrying 12 Julang-2 (JL-2) long-rang ballistic missiles, the low- and high-end projection of a fleet of 4-8 submarines would be able to carry 48-96 missiles with as many warheads. (Despite occasional claims on the Internet that the JL-2 carries MIRV, the US Intelligence Community assigns only one warhead to each missile.)

We estimate that China has a stockpile of approximately 250 nuclear warheads of which nearly 150 are for land-based missiles, 48 for submarines, and perhaps 20 for bombers. Some have speculated that China might have several thousand nuclear weapons, but former USSTRATCOM Commander General Kehler in 2012 rejected this saying that “the Chinese arsenal is in the range of several hundred” nuclear weapons. If China builds eight Jin SSBNs, it would presumably have to produce more warheads for their additional missiles. This could increase the stockpile to around 300 warheads (see table below).

Other weapon systems have also been rumored to have nuclear capability, although status is uncertain: The DH-10 ground-launched land-attack cruise missile is listed by Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) as “conventional or nuclear”; the DH-20 (CJ-20) air-launched cruise missiles was listed in 2013 by US Air Force Global Strike Command the DH-20 (CJ-20) as nuclear-capable; and a CIA intelligence memorandum in 1993 concluded that China “almost certainly has developed a warhead” for the DF-15 short-range ballistic missile and predicted that deployment of a nuclear-armed DF-15 would start in 1994. A nuclear test in January 1972 was with a small bomb delivered by a fighter-bomber (Q-5), although it is uncertain if the capability was ever operationalized and fielded.

SSBN Operational Questions

If China is indeed building significantly more Jin SSBNs, as the statement by PACOM implies, then it is a surprise that raises a number of questions.

The first question is whether it is accurate. The PACOM projection is above and beyond the estimate of 4-6 SSBNs projected by the Office of Naval Intelligence in 2013. The Jin-class is a work in progress and the submarines are noisier than Soviet Delta III SSBNs developed in the 1970s. Presumably the Chinese navy is working hard to make the Jin SSBNs survivable, but up to eight would be an expensive experiment. And China appears to be designing a newer SSBN type anyway, the Type-096. Projections such as these often prove too much too soon, so only time will tell.

But if China were to deploy up to eight Jin SSBNs with up to 96 missiles, it would be a significant shift in China’s nuclear posture, which up till recently was almost entirely focused on land-based nuclear weapons. And this is odd. Why, after having spent significant sources on building mobile ICBMs to hide in forests and caves across China’s vast territory to protect its nuclear deterrent from a first strike, would the Chinese government chose to deploy a significant portion of its nuclear warheads on noisy submarines and send them out to sea where US Navy attack submarines can sink them?

A more important question is how China would actually operate the SSBNs. The Central Military Commission (CMC) does not normally hand out nuclear weapons to the military services but the whole point of having SSBNs is to hide nuclear weapons in the oceans as a secure retaliatory capability. It would be a significant change for Chinese nuclear policy if the CMC loaded warheads on the submarines and deployed them outside Chinese territory. Perhaps they will not be continuously deployed in peacetime but serve as a surge capability in a crisis.

And China does not have much (if any) experience in operating SSBNs on lengthy deterrent patrols. It has only recently started operating nuclear-powered attack submarines on lengthy patrols, including into the Indian Ocean, but the SSBNs have yet to conduct one. PACOM predicted the first would happen last year, but that didn’t happen. Now they predict it will happen this year. We’ll see.

As a party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), a significant increase of the SSBN fleet would further deepen China’s unfortunate status as the only nuclear-armed state part to the treaty that is increasing the size of its nuclear arsenal.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Cooperation Agreements and Nonproliferation

President Obama this week transmitted to Congress the text of a proposed agreement with the People’s Republic of China concerning cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy.

Known as “123 agreements” based on section 123 of the Atomic Energy Act, such accords are intended to regulate international traffic in nuclear materials and technology. The agreements generally provide for physical safeguards on subject materials, require consent for transfers of materials or technology to third countries, and impose restrictions on enrichment and reprocessing.

As of early last year, there were 23 agreements under Section 123 in effect.

“We want other nations to enter into 123 agreements with the United States because our [nuclear safeguards] standards are the highest in the world,” said Daniel B. Poneman, Deputy Secretary of Energy, at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing last year. “In our view, the more 123 agreements that exist in the world, the stronger the nonproliferation controls that will apply to all nuclear commerce.” (The record of that January 2014 hearing entitled “Section 123: Civilian Nuclear Cooperation Agreements” was published last month.)

In practice, the picture is a bit murkier, as such agreements by definition facilitate international transfers of nuclear materials and technology with long-term consequences that cannot always be foreseen. Beneficiaries of prior 123 agreements that subsequently lapsed include pre-revolutionary Iran, Israel, Venezuela, and Vietnam.

The U.S. and China previously reached an agreement on nuclear cooperation in 1985, though its implementation was blocked until 1998. For detailed background, see U.S.-China Nuclear Cooperation Agreement, Congressional Research Service, updated April 20, 2015.

That existing agreement with China expires this year, hence the President’s submission this week of a new proposed text. Among several proliferation-related issues likely to be considered in finalizing the pending agreement are Chinese missile technology exports and its nuclear support to Pakistan.

“China’s expanding civil nuclear cooperation with Pakistan raises serious concerns and we urge China to be more transparent regarding this cooperation,” the State Department’s Thomas Countryman told the Foreign Relations Committee last year.

Meanwhile, Iran is reportedly discussing its research on neutron transport and nuclear modeling with officials of the International Atomic Energy Agency. An extensive bibliography of nuclear research published by Iranian scientists including neutron transport problems and many other topics was prepared by researcher Mark Gorwitz in 2010.

Seeking China-U.S. Strategic Nuclear Stability

“To destroy the other, you have to destroy part of yourself.

To deter the other, you have to deter yourself,” according to a Chinese nuclear strategy expert. During the week of February 9th, I had the privilege to travel to China where I heard this statement during the Ninth China-U.S. Dialogue on Strategic Nuclear Dynamics in Beijing. The Dialogue was jointly convened by the China Foundation for International Strategic Studies (CFISS) and the Pacific Forum Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). While the statements by participants were not-for-attribution, I can state that the person quoted is a senior official with extensive experience in China’s strategic nuclear planning.

The main reason for my research travel was to work with Bruce MacDonald, FAS Adjunct Senior Fellow for National Security Technology, on a project examining the security implications of a possible Chinese deployment of strategic ballistic missile defense. We had discussions with more than a dozen Chinese nuclear strategists in Beijing and Shanghai; we will publish a full report on our findings and analysis this summer. FAS plans to continue further work on projects concerning China-U.S. strategic relations as well as understanding how our two countries can cooperate on the challenges of providing adequate healthy food, near-zero emission energy sources, and unpolluted air and water.

During the discussions, I was struck by the gap between American and Chinese perspectives. As indicated by the quote, Chinese strategic thinkers appear reluctant to want to use nuclear weapons and underscore the moral and psychological dimensions of nuclear strategy. Nonetheless, China’s leaders clearly perceive the need for such weapons for deterrence purposes. Perhaps the biggest gap in perception is that American nuclear strategists tend to remain skeptical about China’s policy of no-first-use (NFU) of nuclear weapons. By the NFU policy, China would not launch nuclear weapons first against the United States or any other state. Thus, China needs assurances that it would have enough nuclear weapons available to launch in a second retaliatory strike in the unlikely event of a nuclear attack by another state.

American experts are doubtful about NFU statements because during the Cold War the Soviet Union repeatedly stated that it had a NFU policy, but once the Cold War ended and access was obtained to the Soviets’ plans, the United States found out that the Soviets had lied. They had plans to use nuclear weapons first under certain circumstances. Today, given Russia’s relative conventional military inferiority compared to the United States, Moscow has openly declared that it has a first-use policy to deter massive conventional attack.

Can NFU be demonstrated? Some analysts have argued that China in its practice of keeping warheads de-mated or unattached from the missile delivery systems has in effect placed itself in a second strike posture. But the worry from the American side is that such a posture could change quickly and that as China has been modernizing its missile force from slow firing liquid-fueled rockets to quick firing solid-fueled rockets, it will be capable of shifting to a first-use policy if the security conditions dictate such a change.

The more I talked with Chinese experts in Beijing and Shanghai the more I felt that they are sincere about China’s NFU policy. A clearer and fuller exposition came from a leading expert in Shanghai who said that China has a two-pillar strategy. First, China believes in realism in that it has to take appropriate steps in a semi-anarchic geopolitical system to defend itself. It cannot rely on others for outside assistance or deterrence. Indeed, one of the major differences between China and the United States is that China is not part of a formal defense alliance pact such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) or the alliance the United States has with Japan and South Korea. Although in the 1950s, Chairman Mao Zedong decried nuclear weapons as “paper tigers,” he decided that the People’s Republic of China must acquire them given the threats China faced when U.S. General Douglas MacArthur suggested possible use of nuclear weapons against China during the Korean War. In October 1964, China detonated its first nuclear explosive device and at the same time declared its NFU policy.

The second pillar is based on morality. Chinese strategists understand the moral dilemma of nuclear deterrence. On the one hand, a nuclear-armed state has to show a credible willingness to launch nuclear weapons to deter the other’s launch. But on the other hand, if deterrence fails, actually carrying out the threat condemns millions to die. According to the Chinese nuclear expert, China would not retaliate immediately and instead would offer a peace deal to avert further escalation to more massive destruction. As long as China has an assured second strike, which might consist of only a handful of nuclear weapons that could hit the nuclear attacker’s territory, Beijing could wait hours to days before retaliating or not striking back in order to give adequate time for cooling off and stopping of hostilities.

Because China has not promised to provide extended nuclear deterrence to other states, Chinese leaders would also not feel compelled to strike back quickly to defend such states. In contrast, because of U.S. deterrence commitments to NATO, Japan, South Korea, and Australia, Washington would feel pressure to respond quickly if it or its allies are under nuclear attack. Indeed, at the Dialogue, Chinese experts often brought up the U.S. alliances and especially pointed to Japan as a concern, as Japan could use its relatively large stockpile of about nine metric tons of reactor-grade plutonium (which is still weapons-usable) to make nuclear explosives. Moreover, last July, the administration of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced a “reinterpretation” of the Article 9 restriction in the Japanese Constitution, which prohibits Japan from having an offensive military. (The United States imposed this restriction after the Second World War.) The reinterpretation allows Japanese Self-Defense Forces to serve alongside allies during military actions. Beijing is opposed because then Japan is just one step away from further changing to a more aggressive policy that could permit Japan to act alone in taking military actions. Before and during the Second World War, Japanese military forces committed numerous atrocities against Chinese civilians. Chinese strategists fear that Japan is seeking to further break out of its restraints.

Thus, Chinese strategists want clarity about Japan’s intentions and want to know how the evolving U.S.-Japan alliance could affect Chinese interests. Japan and the United States have strong concerns about China’s growing assertive actions near the disputed Diaoyu Islands (Chinese name) or Senkaku Islands (Japanese name) between China and Japan, and competing claims for territory in the South China Sea. Regarding nuclear forces, some Chinese experts speculate about the conditions that could lead to Japan’s development of nuclear weapons. The need is clear for continuing dialogue on the triangular relationship among China, Japan, and the United States.

Several Chinese strategists perceive a disparity in U.S. nuclear policy toward China. They want to know if the United States will treat China as a major nuclear power to be deterred or as a big “rogue” state with nuclear weapons. U.S. experts have tried to assure their Chinese counterparts that the strategic reality is the former. The Chinese experts also see that the United States has more than ten times the number of deliverable nuclear weapons than China. But they hear from some conservative American experts that the United States fears that China might “sprint for parity” to match the U.S. nuclear arsenal if the United States further reduces down to 1,000 or somewhat fewer weapons.1 According to the FAS Nuclear Information Project, China is estimated to have about 250 warheads in its stockpile for delivery.2Chinese experts also hear from the Obama administration that it wants to someday achieve a nuclear-weapon-free world. The transition from where the world is today to that future is fraught with challenges: one of them being the mathematical fact that to get to zero or close to zero, nuclear-armed states will have to reach parity with each other eventually.

DOD Report Shows Chinese Nuclear Force Adjustments and US Nuclear Secrecy

The Pentagon’s latest report to Congress on Chinese military developments cost $89.000 to prepare but no longer includes a list of China’s nuclear arsenal.

The Pentagon’s latest annual report to Congress on the Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China describes continued broad modernization and growing reach of Chinese military forces and strategy.

There is little new on the nuclear weapons front in the 2014 update, however, which describes slow development of previously reported weapons programs. This includes construction of a handful of ballistic missile submarines; the first of which the DOD predicts will begin to sail on deterrent patrols later this year.

It also includes the gradual phase-out of the old DF-3A liquid-fuel ballistic missile and the apparent – and surprising – stalling of the new DF-31 ICBM program.

Like all the other nuclear-armed states, China is modernizing its nuclear forces. China earns the dubious medal (although not in the DOD report) of being the only nuclear weapons state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty that is increasing it nuclear arsenal. Far from a build-up, however, the modernization is a modest increase focused on ensuring the survivability of a secure retaliatory strike capability (see here for China’s nuclear arsenal compared with other nuclear powers).

The report continues the Obama administration’s don’t-show-missile-numbers policy. Up until 2010, the annual DOD reports included a table overview of the composition of the Chinese missile force. But the overview gradually became less specific in until it was completed removed from the reports in 2013.

The policy undercuts the administration’s position that China should be more transparent about its military modernization by indirectly assisting Chinese government secrecy.

The main nuclear issues follow below.

Land-Based Nuclear Missile Developments

The DOD report formally identifies the new road-mobile ICBM under development as the DF-41, rumored at least since 1997 to be in development. The missile might “possibly [be] capable of carrying multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRV),” according to DOD. That obviously doesn’t mean that the DF-41 will carry them; the DF-5A has also been assessed for years to be capable of carrying MIRV without ever doing so.

The report lends some support to the assessment – although not explicitly – that deployment of the DF-31 ICBM has ceased after only 5-10 launchers deployed in a single brigade.

Instead, the focus of the road-mobile ICBM modernization appears to have shifted to the DF-31A ICBM, of which the DOD report predicts that more will be deployed by 2015.

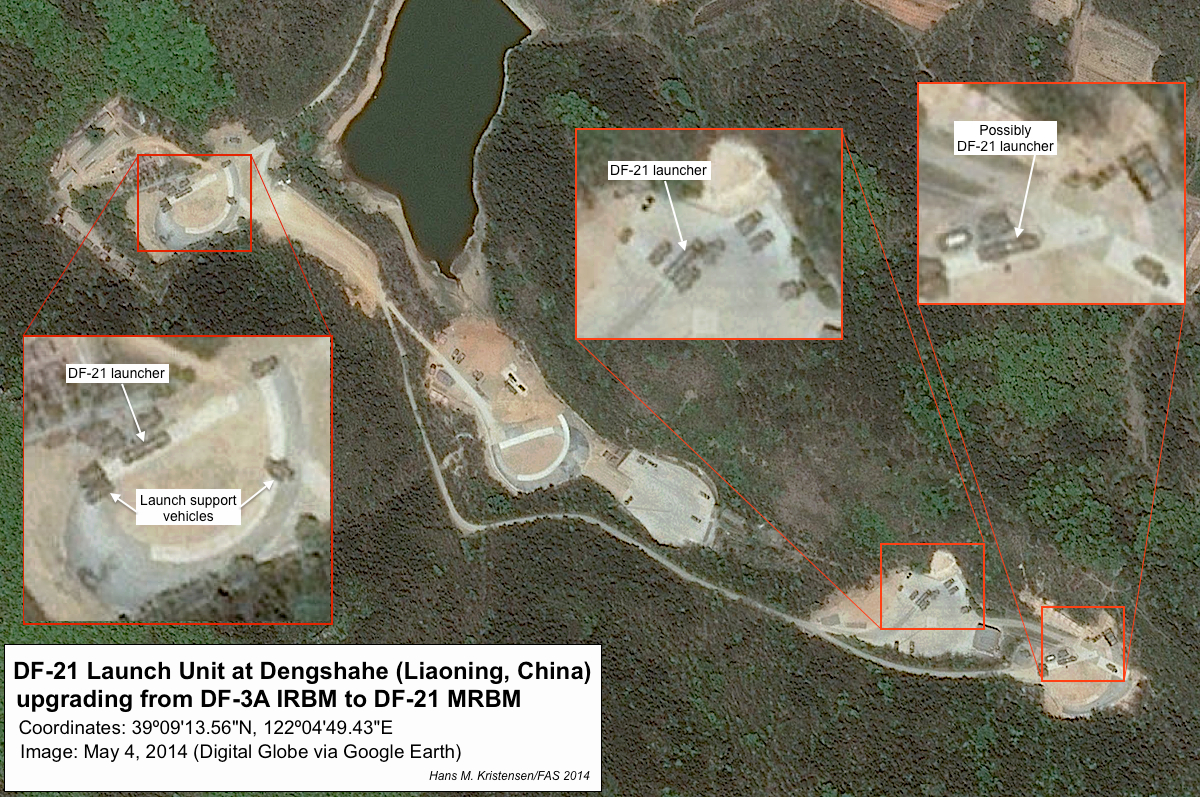

The liquid-fuel DF-3A (CSS-2) IRBM is not mentioned in the 2014 report, an indication that the 3.3-megaton weapon system has finally been retired after 42 years in service. The last DF-3A-equipped Second Artillery brigade – the 810 Brigade north of Dalian in the Liaoning province – was seen in May 2014 to have been converted to the solid-fuel medium-range DF-21 MRBM.

The 2014 DOD report appears to indicate that the 3.3-megaton, liquid-fuel DF-3A IRBM has been retired after 42 years in service.

The only other transportable liquid-fuel ballistic missile, the DF-4 (CSS-3) ICBM, is still operational with 10-15 launchers deployed in one or two brigades. But the missile is expected to be retired soon. When that happens, the only liquid-fuel ballistic missile left in the Chinese arsenals will be the 20 silo-based DF-5As (CSS-4 Mod 1) ICBM, which are still being ungraded.

The report also mentions conventional ballistic missiles under development, including several medium-range versions. That includes that anti-ship version of the DF-21 (CSS-5) – the DF-21D, which the report designates as the CSS-5 Mod 5. That suggests that other conventional MRBMs may also be under development.

Sea-Based Nuclear Missile Developments

The DOD report states that three Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs have been delivered and that two more are in various stages of construction. One of these was seen at the Bohai shipyard in October 2013. After the Jin-program is completed, DOD expects that China will proceed to its next-generation SSBN (Type 096) over the next decade.

The report makes the prediction that “China is likely to conduct its first nuclear deterrence patrols with the JIN-class SSBN in 2014,” assuming that the JL-2 SLBM will finally become operational.

The DOD report predicts that the Jin-class SSBNs (one seen here at Xiaopingdao) likely will conduct China’s first “nuclear deterrent patrols” in 2014, even though the Chinese Central Military Commission is through to insist on central control of Chinese warheads under normal circumstances.

The prediction of the upcoming nuclear deterrent patrols is controversial given that the Chinese leadership so far has been very reluctant to hand over nuclear weapons to the military under normal circumstances. China has never conducted a SSBN deterrent patrol before and a Jin SSBN deploying with nuclear warheads loaded on its SLBMs would constitute a significant change in Chinese nuclear operational policy. It would also constitute the first-ever deployment of Chinese nuclear weapons outside the land-territory of China.

Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Developments

The DOD report does not explicitly attribute nuclear capability to China’s growing inventory of land-attack cruise missiles. Yet the 2013 NASIC report designates the DH-10 ground-launched cruise missile as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation given to the Russian AS-4 and the Pakistani Ra’ad and Babur cruise missiles, weapons widely assumed to be nuclear-capable.

The DH-10 ground-launched land-attack cruise missile is described by NASIC as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation given to Russian and Pakistani dual-capable nuclear cruise missiles.

There are widespread rumors on Chinese Internet sites that the DH-10 has been modified for delivery by the H-6K intermediate-range bomber. It is unknown if that includes the apparently nuclear-capable version.

In addition, US Air Force Global Strike Command last year attributed the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile with nuclear capability, but neither NASIC nor the DOD does so.

Additional background: FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2013

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Chinese Nuclear Missile Upgrade Near Dalian

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

One of the last Chinese Second Artillery brigades with the old liquid-fuel DF-3A intermediate-range nuclear ballistic missile appears to have been upgraded to the newer DF-21 road-mobile, dual-capable, medium-range ballistic missile.

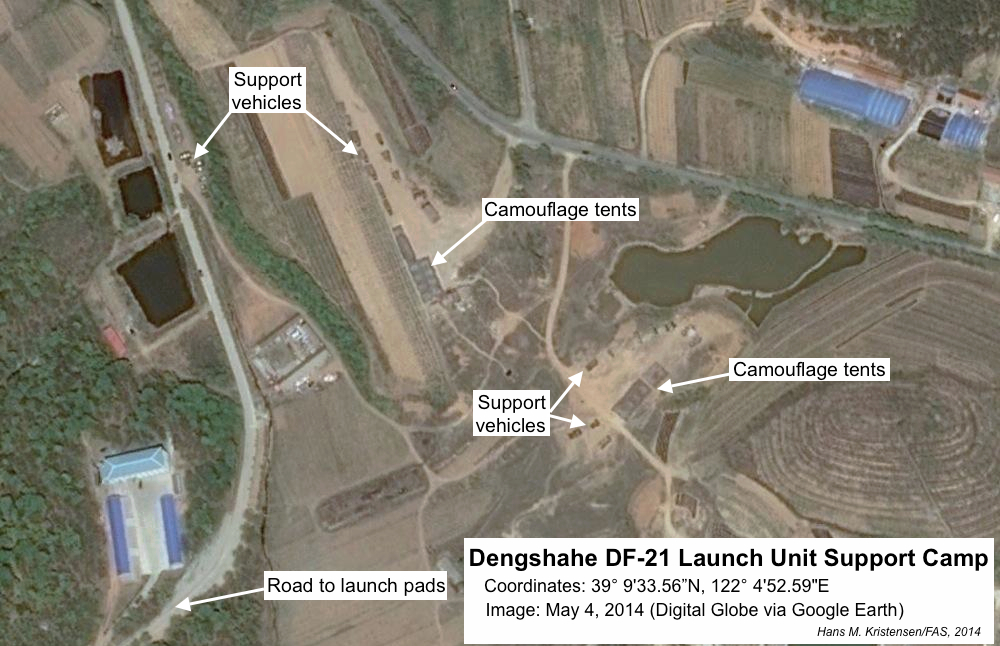

A new satellite image posted on Google Earth from May 4, 2014, reveals major changes to what appears to be a launch unit site for the Dengshahe brigade northeast of Dalian by the Yellow Sea.

The upgrade apparently marks the latest phase in a long and slow conversion of the Dengshahe brigade from the DF-3A to the DF-21.

The 810 Brigade base appears to be located approximately 60 km (36 miles) northeast of Dalian in the Liaoning province (see map below). The base is organized under 51 Base, one of six base headquarters organized under the Second Artillery Corps, the military service that operates the Chinese land-based nuclear and conventional missiles.

The 810 Brigade is based approximately 60 km (36 miles) northeast of Dalian, and the launch unit approximately 17 km (10 miles) south of the base.

The launch unit appears to be using a remote site with four launch pads for training approximately 17 km (10 miles) south of the brigade base. A new commercial satellite image, dated May 4, 2014, and made available by Digital Globe via Google Earth, shows significant upgrades at the site since 2006.

This includes construction of new launch pads that in shape and size appear to match those recently seen at the 807 Brigade base launch unit near Qingyang (Anhui) and the 802 Brigade base at Jianshui (Yunnan).

The satellite image is particularly interesting because it was taken on a day when the launch unit was using the site for a launch training exercise. Three of the four pads are in use with what appears to be DF-21 launchers deployed on the 45-meter paved strip and support vehicles near by. Other vehicles are positioned near the fourth launch pad (see image below).

Four upgraded launch pads have been constructed at this launch unit site northeast of Dalian, possibly as part of conversion from DF-3A to DF-21 missiles. Click image for larger version.

The relatively poor quality of the high-resolution satellite image makes it hard to positively identify the launchers. But at approximately 14 meters (46 feet) they appear to match the nuclear DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1/Mod 2), which has a 10-11 meter (33-36 feet) missile canister on a trailer pulled by the motorized drivers section. The launchers do not appear to be the DF-21C, the conventional version, where the missile canister and drivers section are mounted on the same frame and the tip of the missile canister extends forward over the driver cabin (see here for images of such a unit).

A road-mobile launch unit has a large fingerprint because the launchers need a significant number of different support vehicles and personnel to operate. This includes command and control vehicles, cranes and other repair vehicles, trucks and busses. The Dengshahe launch unit image shows part of the large backup encamped immediately north of the launch pad sites (see image below).

Conversion to DF-21 at Dengshahe has been a long and slow process. DF-3A training levels dropped from five to eight months per year in the late-1980s to four months per year in the mid-1990s. Since then, the 810 Brigade shrunk to only five-ten launchers. The final phase has happened since 2006.

This unidentified picture of a DF-3A missile readied for launch with fuel trucks and other support vehicles might be from the second-most eastern launch pad at the Dengshahe site.

The range of the DF-21 is less than the range of the DF-3A (2,150 km versus 3,000 km), but the DF-21 system is much more capable than the DF-3A. Unlike the liquid-fuel, transportable DF-3A, the DF-21 is a solid-fuel missile carried on a road-mobile transporter erector launcher (TEL). As such, the DF-21 TEL can move around the landscape much more freely and can set up and fire its missile quicker than the DF-3A system. The DF-21 is also more accurate, which is reflected in a smaller warhead – 200-300 kilotons versus 3,300 kilotons for the DF-3A warhead.

From the launch pads north of Dalian, the DF-21 would able to target all U.S. military bases on the Japanese mainland as well as on Okinawa.

A DF-21 transporter erector launcher with the missile canister partially erected is surrounded by support vehicles.

The conversion from the DF-3A to the DF-21 is also reflected in significant reconstruction at the 810 Brigade base. Since 2006, this has included replacement of one of two high-bay garages with what are possibly garages for the DF-21 road-mobile launchers. A second high-bay garage has been significantly modified, and the support vehicle technical area has been upgraded (see image below).

Since 2006, the 810 Brigade base at Dengshahe north of Dalian has been upgraded with possible DF-21 launcher garages and a modified high-bay garage for maintaining the launchers and missiles. Click image for larger version.

Background information: Chinese nuclear forces, 2013

Previous blogs about Chinese nuclear forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Modernization Briefings at the NPT Conference in New York

By Hans M. Kristensen

Last week I was in New York to brief two panels at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (phew).

The first panel was on “Current Status of Rebuilding and Modernizing the United States Warheads and Nuclear Weapons Complex,” an NGO side event organized on May 1st by the Alliance for Nuclear Accountability and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). While describing the U.S. programs, I got permission from the organizers to cover the modernization programs of all the nuclear-armed states. Quite a mouthful but it puts the U.S. efforts better in context and shows that nuclear weapon modernization is global challenge for the NPT.

The second panel was on “The Future of the B61: Perspectives From the United States and Europe.” This GNO side event was organized by the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation on May 2nd. In my briefing I focused on providing factual information about the status and details of the B61 life-extension program, which more than a simple life-extension will produce the first guided, standoff nuclear bomb in the U.S. inventory, and significantly enhance NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

The two NGO side events were two of dozens organized by NGOs, in addition to the more official side events organized by governments and international organizations.

The 2014 PREPCOM is also the event where the United States last week disclosed that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has only shrunk by 309 warheads since 2009, far less than what many people had anticipated given Barack Obama’s speeches about “dramatic” and “bold” reductions and promises to “put an end to Cold War thinking.”

Yet in disclosing the size and history of its nuclear weapons stockpile and how many nuclear warheads have been dismantled each year, the United States has done something that no other nuclear-armed state has ever done, but all of them should do. Without such transparency, modernizations create mistrust, rumors, exaggerations, and worst-case planning that fuel larger-than-necessary defense spending and undermine everyone’s security.

For the 185 non-nuclear weapon states that have signed on to the NPT and renounced nuclear weapons in return of the promise made by the five nuclear-weapons states party to the treaty (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, and the United States) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to the cessation of the nuclear arms race at early date and to nuclear disarmament,” endless modernization of the nuclear forces by those same five nuclear weapons-states obviously calls into question their intension to fulfill the promise they made 45 years ago. Some of the nuclear modernizations underway are officially described as intended to operate into the 2080s – further into the future than the NPT and the nuclear era have lasted so far.

Download two briefings listed above: briefing 1 | briefing 2

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

China SSBN Fleet Getting Ready – But For What?

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

China’s emerging fleet of 3-4 new Jin-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines is getting ready to deploy on deterrent patrols, “probably before the end of 2014,” according to U.S. Pacific Command.

A new satellite image taken in October 2013 (above) shows a Jin SSBN in dry dock at the Bohai shipyard in Huludao. Two of the submarine’s 12 missile tubes are open. It is unclear if the submarine in the picture is the fourth boat or one of the first three Jin SSBNs that has returned to dry dock for repairs or maintenance.

The U.S. intelligence community predicts that “up to five [Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs] may enter service before China proceeds to its generation SSBN (Type 096) over the next decade,” an indication that the noisy Jin-class design might already be seen as outdated.

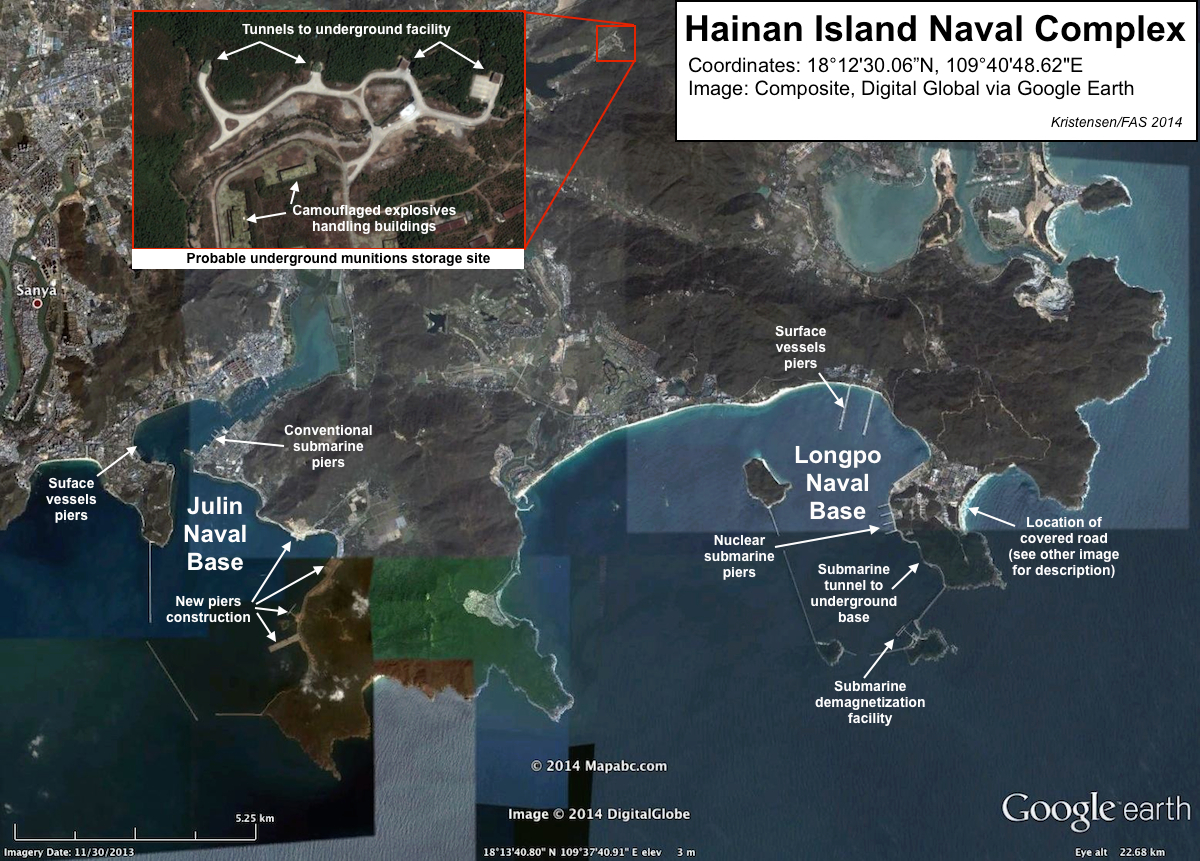

This and numerous other commercial satellite images (see below) show how China over the past decade has built an infrastructure of naval facilities to service the new SSBN fleet. This includes upgrades at naval bases, submarine hull demagnetization facilities, underground facilities and high-bay buildings for missile storage and handling, and covered tunnels and railways to conceal the activities from prying eyes in the sky.

Apart from how many Jin SSBNs China will build, the big question is whether the Chinese government will choose to operate them the way Western nuclear-armed states have operated their SSBNs for decades – deployed continuously at sea with nuclear warheads on the ballistic missiles – or continue China’s long-held policy of not deploying nuclear weapons outside Chinese territory but keeping them in central storage for deployment in a crisis.

Nuclear Submarine Sightings

Over the past decade, a total of 25 commercial satellite images made available on Google Earth have provided visual confirmation and information about the status and location of the Jin SSBNs (see table below). They show the submarines at four sites: the Bohai shipyard at Huludao on the Bohai Sea where the submarines are built; the Xiaopingdao naval base near Dalian where the submarines are fitted out for missile launch tests; the North Sea Fleet base at Jianggezhuang near Qingdao where one Jin SSBN is homeported along with the old Xia-class SSBN from the 1980s; and at the South Sea Fleet base at Longpo on Hainan Island where at least one Jin SSBN has been based since 2008.

Bohai Ship Yard

The Bohai shipyard at Huludao builds China’s nuclear-powered submarines. The shipyard, which is located in the north of the Bohai Sea, is immensely busy with numerous large tankers and cargo ships under construction at any time. The submarine hulls are assembled in a large 40,000-squaremeter construction hall at the western end of the shipyard, rolled across a storage area into a dry dock for completion, and then launched into the harbor where they spend years tied up to a pier fitting out until handed over to the Chinese navy (PLAN).

Commercial satellite photos provide snapshots of the status of submarine construction and the quality is good enough to differentiate different submarine types and identify design details such as dimensions and layout of the missile compartment. One of the most recent photos (see below) shows a Jin-class SSBN in dry dock with two of 12 missile tubes open. Additional unassembled submarine hull sections are laid out on the ground next to the assembly hall.

The busy Bohai shipyard mixes nuclear submarine construction with commercial tankers and cargo ships in half a dozen dry docks. In this composite image from October 11 and 25, 2013, a completed Jin-class SSBN can be seen in dry dock and what appear to be hull sections for another submarine awaiting assembly. Click for large version.

In addition to satellite photos, tourists also occasionally take photos and post them on Google Panoramio or other web site. One such photo (see below) shows most of the shipyard with other overlaid photos showing dry dock cranes and two missile submarines first seen in 2007.

Xiaopingdao Submarine Refit Base

After completing construction at the Bohai shipyard the submarines sail to the Xiaopingdao refit base near Dalian. This base is used to prepare the submarines for operational service and is where test missiles are loaded into the launch tubes for test launches from the Bohai Sea across China into the Qinghai desert. Xiaopingdao is also used by China’s single Golf-class SSB, a special design submarine previously used to test launch SLBMs.

The base has been upgraded several times over the past decade-and-a-half including an extended pier to service the larger Jin-class SSBNs.

On two occasions, in March 2009 and March 2011, two Jin SSBNs have been seen docked at Xiaopingdao at the same time.

Xiaopingdao is also where the first Jin-class SSBN was spotted on a commercial satellite photo in July 2007.

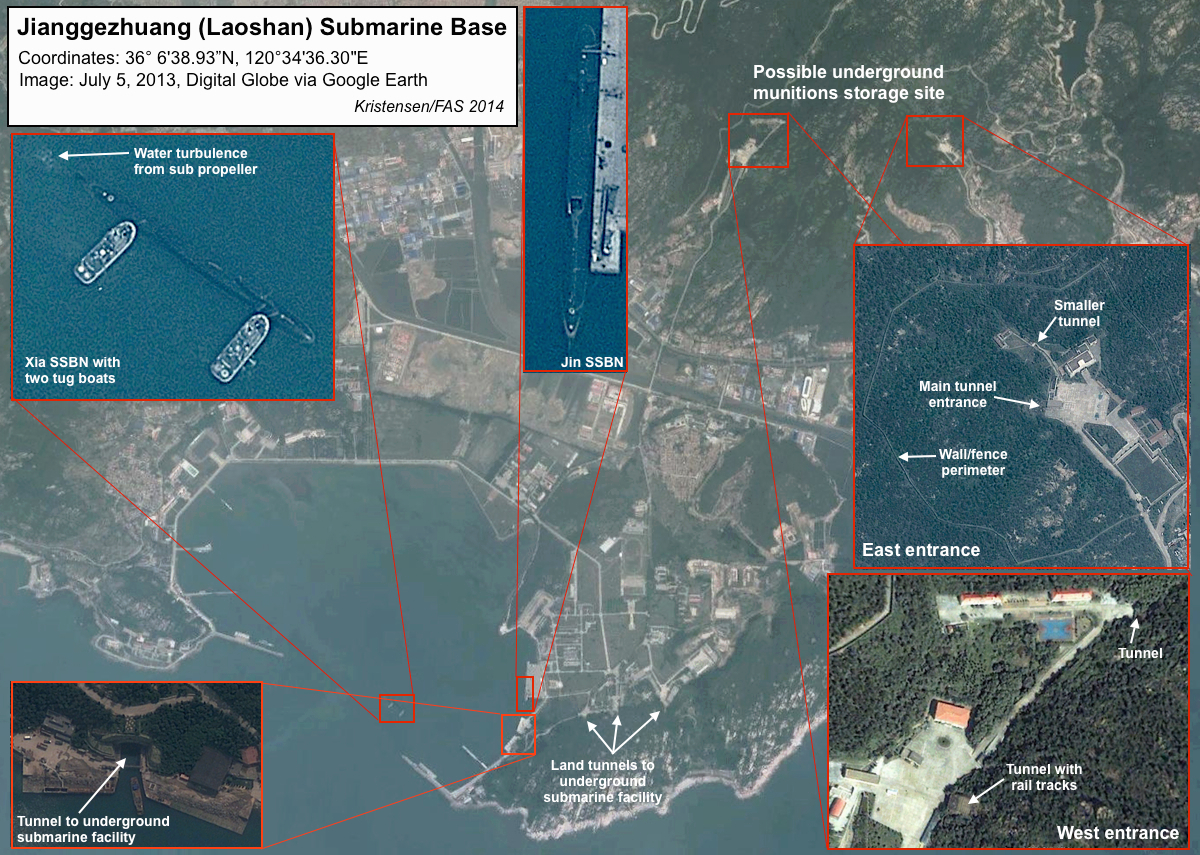

Jianggezhuang (Laoshan) Submarine Base

The oldest nuclear submarine base is the North Sea Fleet base at Jianggezhuang (Laoshan) approximately 18 kilometers (11 miles) east of Qingdao in the Shandong province.

The Jin-class SSBN was first seen at Jianggezhuang on a commercial satellite image in August 2010.

The base is also home to the old Xia-class SSBN, the lone unit of China’s first experiment with ballistic missile submarines. The Xia completed a multi-year dry dock overhaul in 2007 but has probably never been fully operational and has never conducted a deterrent patrol.

This base is where we in 2006 spotted the long-rumored submarine cave, also described in Imaging Notes. The cave has a large water tunnel with access from the harbor and three land-tunnels providing access from various base facilities.

A satellite image from July 2013 (see below) shows both the Xia and a Jin SSBN at the base, with the Xia being assisted by two tugboats. Water turbulence behind the submarine indicates the Xia’s engine is operational.

Both Jin- and Xia-class SSBNs are based at Jianggezhuang submarine base, which includes an underground submarine cave. A possible underground weapons storage site is located northeast of the base. Click for large version.

Jianggezhuang also has a dry dock, the only one at a naval base that has so far been seen servicing nuclear-propelled submarines. There are also several nuclear-powered attack submarines homeported at the base.

Only a few miles north of the base is an underground facility that may be storing munitions for the submarine fleet. As such, it could potentially also serve as a regional storage facility for nuclear warheads for the SLBMs once released to the navy in a crisis by the Central Military Committee.

Several buildings have been added since 2003, possibly in preparation for accommodating the new Jin SSBN and its larger JL-2 SLBMs.

Hainan Island Submarine Complex

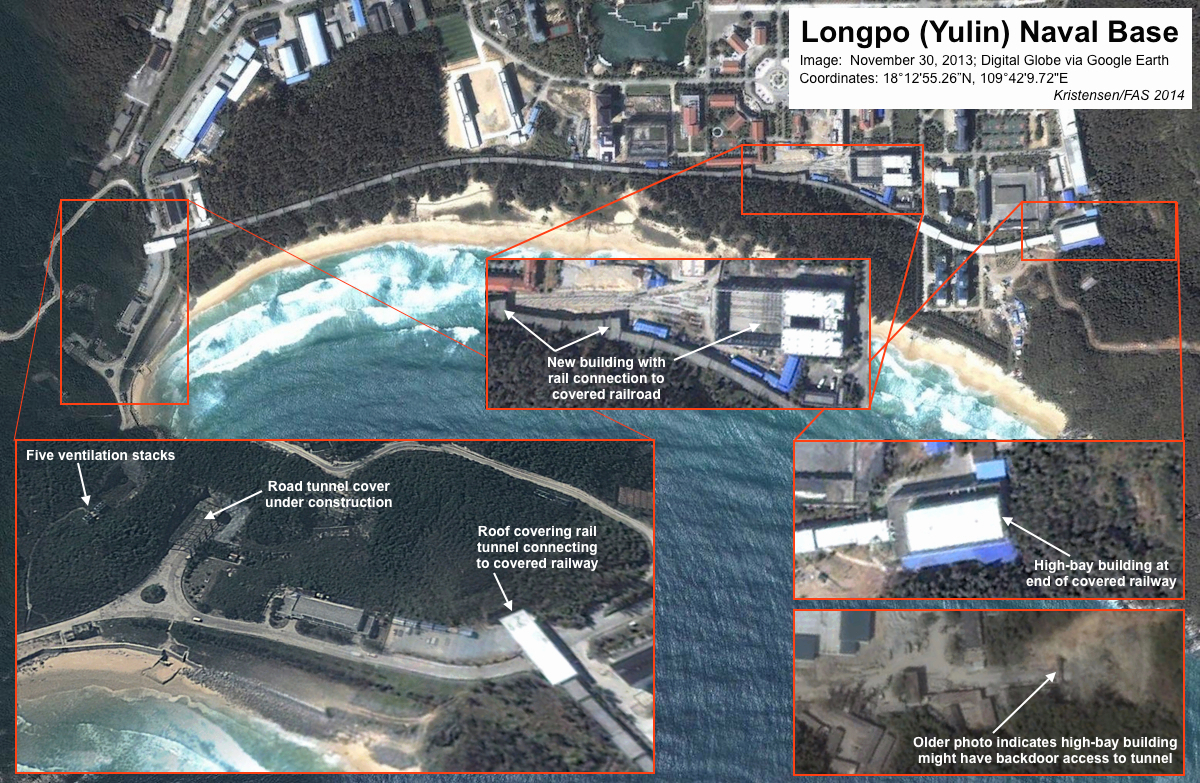

The South Sea Fleet naval facilities on Hainan Island are under significant expansion. The nuclear submarine base at Longpo has been upgraded to serve as the first nuclear submarine base in the South China Sea. The first Jin-class SSBN was seen at Longpo on February 27, 2008, and a new photo from November 2013 shows a Jin SSBN with its missile tubes open (see below).

In this image from November 30, 2013, a Jin-class SSBN can be seen flashing its 12 missile tubes while docked at Longpo naval base on Hainan Island.

Longpo submarine base includes four piers for submarines, an underground submarine facility with tunnel access from the harbor and land-tunnels from the other side of the mountain, as well as a demagnetization facility. Longpo was the first base to get a demagnetization facility, which has since also been added to the East Sea Fleet near Ningbo.

The Hainan naval complex also includes the conventional submarine base at Julin, which also appears to be under expansion with new piers and a sea break wall under construction.

Approximately 12 kilometers (7 miles) northeast of Longpo is a military facility that appears to include four tunnels connecting to one or several underground facilities inside the mountain. Tugged away at the end of a lake inside a valley, the facility has a significant infrastructure with administrative and technical buildings as well as several camouflaged high-bay buildings surrounded by berms for blast protection during explosives handling.

The naval complex on Hainan Island is spread across several locations with nuclear submarines based at Longpo, conventional submarines based at Julin, and a possible underground weapon storage facility north of the bases. Click for large version.

The Longpo base does not have a dry dock so nuclear submarines would have to sail to another base for maintenance or repair. The conventional submarine base at Julin has a 165-meter (550-feet) dry dock that could potentially accommodate a Jin-class SSBN, but it would be a tight fit. More likely are the 215-meter (706-feet) dry docks at the Zhanjiang Naval Base on the mainland north of Hainan Island, or the East Sea Fleet submarine base near Ningbo. Yet so far available commercial satellite images have not shown a nuclear submarine at either Julin, Zhanjiang (South Sea Fleet headquarters), nor Ningbo (East Sea Fleet headquarters), and it is unclear if the bases are certified for nuclear-propelled submarines. If not, then nuclear submarines based on Hainan Island would have to use a dry dock as far north as Jianggezhuang or Bohai for maintenance and repairs. That seem strange so I’m sure I’ve missed a naval dry dock somewhere closer to Hainan.

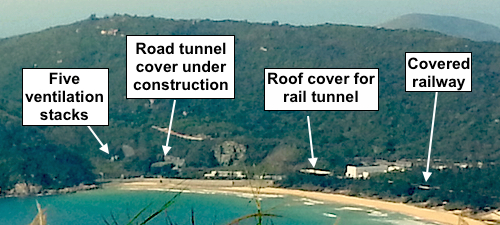

A unique new feature at Longpo is a 1.3-kilometer (0.8-mile) long covered railway completed in May or June 2010 (see below). The railway connects a high-bay building with possible access into the mountain at the eastern part of the base with one of the land-based tunnels to the underground submarine cave on the Longpo peninsula. The covered railway clearly seems intended to keep movement of something between the two mountains out of sight from spying satellites. Two turnoffs from the railway lead to a large building under construction with rail tracks inside. The purpose of the new facilities and rail is unknown but might potentially be intended for movement of SLBMs or other weapons between storage inside the mountain to the submarine cave for arming of SSBNs or SSNs.

A new covered railway constructed in 2010 might connect a missile handling building with the submarine cave on the other side of the mountain. Click for large version.

Before a roof was constructed to conceal the land-tunnel into the submarine cave, the rail tracks into the tunnel were visible on satellite images. Other features at this portion of the base include five ventilation stacks, the roof between the covered railway and tunnel entrance, and a coverage being constructed over a second tunnel road entrance (see above). These features are also visible on a tourist photo posted on Google Panoramio (see below).

The east side of the underground submarine cave at the Longpo naval base on Hainan Island includes rail- and road-tunnels, ventilation stacks, and a covered railway.

Implications

With the emerging Jin-class SSBN fleet, China appears ready to add an important component to its nuclear deterrent. Although the focus of China’s nuclear posture is the land-based missile force, the Chinese leadership appears to view a triad of nuclear forces as a symbol of great power status. Commercial satellite images clearly show that the Chinese leadership has been spending considerable resources over the past decade building the infrastructure needed to support the SSBN fleet. The development is watched closely in India, Japan, and the United States as an example of China’s (modestly) growing and more sophisticated nuclear arsenal.

In building the Jin-class SSBN fleet, however, China appears more to mirror the nuclear postures of the United States, Russia, Britain and France rather than demonstrating a clear purpose and contribution of the SSBN force to China’s own security and crisis stability in general.

As a new second-strike capability added to the Chinese nuclear arsenal, the Jin SSBN fleet only makes strategic sense if it is more secure than the Second Artillery’s land-based ICBM force. Its justification must be based on a conclusion that the ICBMs are too vulnerable to a first strike and that a more secure sea-based second-strike force therefore is needed.

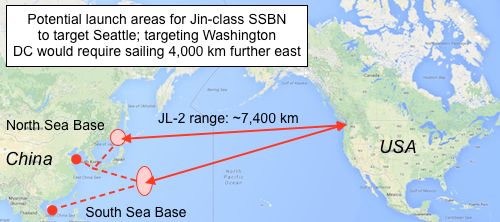

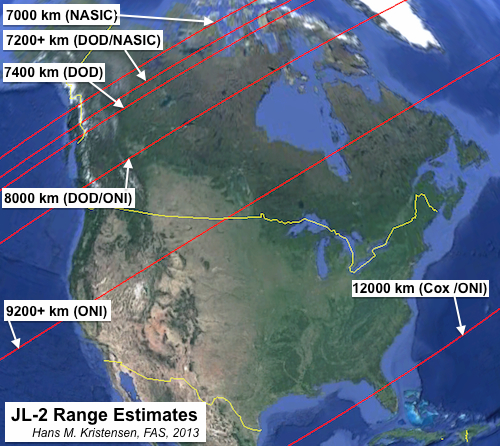

The ultimate test of the Jin SSBNs will be whether they can survive long enough at sea in a hypothetical war situation to provide a back-up deterrent at all. If they are too noisy, the Jins could be vulnerable to early detection and attrition, especially if they had to deploy to distant patrols areas in order for the missiles to be able to reach important targets. With a range of 7,200 to 7,400 kilometers (4,470 to 4,600 miles) – the range estimate given by the U.S. intelligence community for the JL-2 SLBM carried on Jin-class SSBNs, a submarine would need to sail deep into the Pacific Ocean to be able to target the U.S. west coast. To threaten Washington DC, a Jin SSBN would have to sail halfway across the Pacific (see map below). Not exactly safe travel for a submarine that is noisier than the ancient Russian Delta III SSBNs built in the 1970s.

It is probably a fair assumption that U.S. attack submarines have already been trailing or monitoring the Jin SSBNs to record individual sound characteristics and observe operational patterns. Such information would be used to locate and, if necessary, sink the Chinese submarines in a hypothetical war.

The value of the Jin SSBNs is also dependent on their capability to communicate with the national command authority on land from submerged patrol areas. Secure and reliable communication is essential for the Chinese leaders to be able to exercise command and control of the nuclear missiles on the SSBNs. If communication is poor, the SSBNs could become irrelevant or, perhaps more importantly, downright dangerous to crisis stability if loss of contact caused Beijing to mistakenly conclude that one or more of the subs had been sunk by enemy action. That could, potentially, cause the Chinese leadership to conclude that the nuclear threshold had already been crossed and decide to activate its land-based nuclear forces in a way that would be seen by an adversary as preparation to launch.

Some of these issues may become clearer when China begins to operate the Jin submarines as a real SSBN force. Part of the public debate has been somewhat overblown with claims that Jin SSBNs will be able to target the continental United States from Chinese waters. They will not. And the DOD assessment that the Jins “will give the PLA Navy its first credible sea-based nuclear deterrent” is probably premature and certainly depends on what is meant by “credible.”

Whatever their ultimate capability may be, however, the Jin SSBNs and the infrastructure China is building are symbols of the extensive nuclear modernizations that are underway in all the nuclear-armed countries. The Chinese government says it “will never enter into a nuclear arms race with any other country,” but it is certainly in a technological race with the United States, Russia and India about developing improved and more capable nuclear weapons.

Additional resources: Previous articles about Chinese nuclear forces | Most recent (2013) Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Force Modernization

Launch pads for DF-21 mobile medium-range ballistic missile launchers have been added to a Second Artillery base in southern China.

Click image for large version with annotations.

Image: Digital Globe 2012 via Apple Maps.

By Hans M. Kristensen

China continues to upgrade bases for mobile nuclear medium-range ballistic missiles. The image above shows one of several new launch pads for DF-21 missile launchers constructed at a base near Jianshui in southern China.

A new satellite image* on Apple Maps shows the latest part of a two-decade long slow replacement of old liquid-fuel moveable DF-3A intermediate-range ballistic missiles with new road-mobile solid-fuel DF-21 medium-range ballistic missiles.

Similar developments can be seen near Qingyang in the Anhui province in eastern China and in the Qinghai and Xinjiang provinces in central China.

This and other developments are part of our latest Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces, recently published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

New Nuclear Notebook

In the Nuclear Notebook, Robert Norris and I estimate that China currently has roughly 250 warheads in its nuclear stockpile for delivery by land- and sea-based ballistic missiles, aircraft, and possibly cruise missiles.

This is a slight increase compared with previous years that reflects the introduction of new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). China is the only nuclear weapon state party to the Non-Proliferation Treaty that is increasing its nuclear stockpile, which might grow a bit more over as more missiles are fielded over the next decade.

Even so, the Chinese nuclear modernization is very slow, as in the case of the introduction of DF-21 medium-range ballistic missiles (MRBMs) at Jianshui and the apparent (temporary?) leveling out of ICBM deployments; China is clearly not in a hurry to reach parity with the United States or Russia anytime soon (if at all) but instead seems focused on safeguarding its minimum retaliatory nuclear deterrent. Even so, the breadth of Chinese nuclear capabilities is widening with introduction of a class of ballistic missile submarines and cruise missiles that might have nuclear capability. With these come new scenarios and command and controls issues that are not yet apparent or understood.

Several interesting publications have made contributions to the public debate on China’s nuclear force operations and modernization over the past few years. Most valuable has been the work by Mark Stokes at Project 2049, most noticeably his 2010 report on China’s nuclear warhead storage and handling system. Also in 2010, M. Taylor Fravel and Evan Medeiros provided valuable analysis of China’s search for assured retaliation. Retired Russian general Victor Yesin claimed in 2012 that China has 1,300-1,500 nuclear warheads more than assumed by the U.S. intelligence community – a Georgetown University study even imagined 3,000 warheads (we consider these estimates exaggerated; see here and here). And renowned scholars John Lewis and Xue Litai described last year what they view as an increasing complexity of Chinese nuclear war planning.

The SSBN Force

Since our previous Notebook in 2011, most attention has been on the status of China’s new ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) and Julang-2 SLBM. After a series of technical difficulties, the DOD reported in May 2013 that the JL-2 “appears ready to reach initial operational capability in 2013.”

The range of the JL-2 has been the subject of much speculation, and we are struck by how much the range estimates vary and how much experts and news media continued to use outdated estimates or claim that the missile will be able to target the entire United States from Chinese waters. A review of the various estimates published by U.S. government agencies since 1999 shows estimates spanning from 7,000 km to as much as 12,000 km (see image below), although most hover around 7,200+ km.

US range estimates for China’s Julang-2 SLBM vary considerably, but most are around 7,200+ km.

The latest range estimates of 7,000+ km (NASIC) to 7,400+ km (DOD) show continued uncertainty within the U.S. Intelligence Community about the JL-2 capability. But both estimates also reaffirm that the missile cannot be used to target the continental United States from Chinese waters. Doing so would require a range of at least 8,400 km – and that would only reach Seattle. To target Washington DC from Chinese waters, the range would have to be at least 11,000 km. With the current range estimate of about 7,200+ km, a JL-2 equipped SSBN would have to sail deep into the Sea of Japan between the island of Hokkaido and Russia’s Primorsky Krai oblast to target Seattle, or venture far into the Pacific northeast of Tokyo. To target Washington DC, the SSBN would have to sail even further and launch from a position between the Aleutian Islands and Hawaii – more than halfway across the Pacific Ocean. Due to the apparent noise level of Chinese missile submarines and the extensive anti-submarine capabilities of the United States, that would indeed be risky sailing in a war.

Sending SSBNs far into dangerous water would be China’s only option to fire missiles directly at the United States if Chinese leaders wanted to avoid shooting across Russian territory (all China’s ICBMs launched at the United States from their current deployment areas would overfly Russia).

A JL-2 equipped SSBN could of course target U.S. territories outside the continental United States, including Alaska and Guam, from Chinese waters. To target Hawaii, and SSBN would have to launch from a position in the Sea of Japan or the Philippine Sea.

All of that just to say that JL-2 – despite what you might hear on the Internet – can not be used to target the continental United States. Instead, it is a regional weapon capable of targeting Alaska, Guam, India and Russia from Chinese waters.

So far three Jin-class SSBNs have been delivered and one or two more are in various stages of construction. By 2020, according to information obtained from ONI, China might operate 4-5 SSBNs (see image below). Now that China has said something about its submarines (see sections below), it would help if it would also say something in its next transparency initiative about how many SSBNs it plans to build. The United States, Russia, France and Britain have all shown their plans and there’s no reasons China cannot do so as well.

A Washington Times article recently described how many of China’s state-run press outlets have reported that China’s SSBNs “are now on routine strategic patrol,” and quoted the an article concluding that this “means that China for the first time has acquired the strategic deterrence and second strike capability against the United States.”

The first claim – that China’s SSBNs are now on routine strategic patrol – is wrong. Although it has operated an SSBN (the Xia) since the early 1980s, China has never conducted an SSBN deterrent patrol. And since the JL-2 is not yet operational, the SSBNs are certainly not on patrol yet. But even once the JL-2 becomes operational, it is not clear whether China will operate the SSBN fleet in the way other nuclear weapons states operate their SSBNs. For one thing, it seems unlikely that the Chinese leadership would authorize deployment of nuclear weapons onboard SSBNs unless in a crisis situation.

The second claim – that China for the first time has acquired the strategic deterrence and second-strike capability against the United States – is also not correct. China has had a nuclear deterrent and second-strike capability against the continental United States since 1981 when the silo-based DF-5 ICBM became operational. In 2008, that posture of 20 missiles was broadened with the addition of the road-mobile DF-31A ICBM. Even before the JL-2 has become operational, China already has about 40 ICBMs that can target the U.S. mainland.

Once the Jin/JL-2 weapon system becomes operational, China would theoretically be able to conduct SSBN deterrent patrols. But that will not in itself provide a submarine-based strike capability against the continental United States from Chinese waters because of the range limitations described above.

The So-Called Targeting Map

Chinese news media carried several stories (see for example here, here, here) in September about increasing transparency of the submarine force. Despite claims about “revelations,” the articles did not reveal much that wasn’t already known. That said, any official news about the secretive submarine force and its operations is of course better than nothing – and perhaps a new beginning.

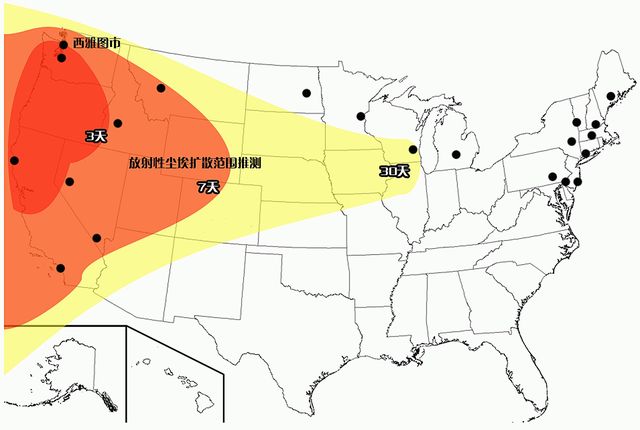

What created the most attention in the United States, however, was a map (see figure below) that allegedly showed radioactive fallout over the western part of the country apparently following a Chinese submarine attack with the future JL-2 SLBM. I have not been able to find the original article with the map on Global Times but there were plenty of dramatic spin-offs in U.S. papers suggesting the image showed Chinese plans for a strike on the United States. And some hinted that publication in “state-run media” somehow reflected Chinese government endorsement of the information.

A map on a Chinese web site describes fictive fallout from hypothetical Chinese nuclear strike on the United States.

Instead, the map appears on huanqiu.com, a glossy military-techno web site without official government status. And the publication is not an “article” but a series of 30 slides with text below each image by someone who appears to have vacuum-cleaned the much of the information from the Internet – including from some of my publications. Statements made in other news articles by “military experts” Du Wenlong (identified as a senior researcher with the PLA Academy of Military Scientists) and Li Jie (affiliation not identified) do not appear in the slides. The Google translator lists the slides editor’s name as [Shen Then] and the artist that drew the map is identified as Pei Shen.

In other words, this map does not appear to be an official government product and does not appear to reflect official Chinese nuclear strike planning.

The map shows three colored regions of radioactive fallout progressively spreading across the United States after 3, 7, and 30 days. One city (Seattle) is identified and 20 other black dots appear to mark locations of major cities. Many are misplaced – and some are odd.

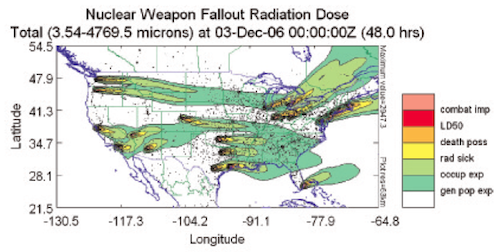

The radioactive fallout patterns on the map are also not very good and appear to be fictive. In reality, radioactive fallout patters are much more narrow, depending on wind and precipitation. In 2006, FAS and NRDC published a report in which we used advanced computer programs to simulate hypothetical Chinese nuclear strikes on the United States. They showed not surprisingly that use of only 20 missiles against American cities would kill tens of millions of people. Back then China only had about 20 DF-5A missiles that could reach the continental United States. But their 20 4-Megaton warheads would cause enormous devastation and extensive radioactive fallout throughout much of the United States (see figure below).

Fallout from attack on 20 US cities with 20 DF-5A 4-MT ground burst warheads.

Source: Hans M. Kristensen, et al., Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning, FAS/NRDC, November 2006, p. 191.

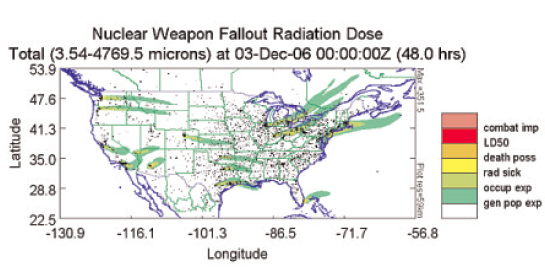

Since then, China has introduced the DF-31A ICBM, each of which carries a smaller (but still significant) warhead. The second simulation we did therefore examined the effect of 20 DF-31A missiles, each with a 250-kiloton warhead. These explosions would also kill tens of millions of people but cause considerably less radioactive fallout (see figure below).

Fallout from attack on 20 US cities with 20 DF-31A 250-kiloton ground burst warheads.

Source: Hans M. Kristensen, et al., Chinese Nuclear Forces and U.S. Nuclear War Planning, FAS/NRDC, November 2006, p. 193.

* I’m indebted to Marius Bulla, a 21-year old GIS enthusiast and freelance photographer in Germany, for first bringing my attention to the Apple Maps image of the Jianhui upgrade.

Additional information: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2013

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Air Force Intelligence Report Provides Snapshot of Nuclear Missiles

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published its long-awaited update to the Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report, one of the few remaining public (yet sanitized) U.S. intelligence assessment of the world nuclear (and other) forces.

Previous years’ reports have been reviewed and made available by FAS (here, here, and here), and the new update contains several important developments – and some surprises.

Most important to the immediate debate about further U.S.-Russian reductions of nuclear forces, the new report provides an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

Another new development is a significant number of new conventional short-range ballistic missiles being deployed or developed by China.

Finally, several of the nuclear weapons systems listed in a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing are not included in the NASIC report at all. This casts doubt on the credibility of the AFGSC briefing and creates confusion about what the U.S. Intelligence Community has actually concluded.

Russia

The report estimates that Russia retains about 1,200 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs, slightly higher than our estimate of 1,050. That is probably a little high because it would imply that the SSBN force only carries about 220 warheads instead of the 440, or so, warheads we estimate are on the submarines.

“Most” of the ICBMs “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” the report states. This excessive alert posture is similar to that of the United States, which has essentially all of its ICBMs on alert.

The report also confirms that although Russia is developing and deploying new missiles, “the size of the Russia missile force is shrinking due to arms control limitations and resource constraints.”

Unfortunately, the report does not clear up the mystery of how many warheads the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) missile carries. Initially we estimated thee because the throw-weight is similar to the U.S. Minuteman III ICBM. Then we considered six, but have recently settled on four, as the Strategic Rocket Forces commander has stated.