The Pentagon’s (Slimmed Down) 2025 China Military Power Report

On Tuesday, December 23rd, the Department of Defense released its annual congressionally-mandated report on China’s military developments, also known as the “China Military Power Report,” or “CMPR.” The report is typically a valuable injection of information into the open source landscape, and represents a useful barometer for how the Pentagon assesses both the intentions and capabilities of its nuclear-armed competitor.

This year’s report, and particularly the nuclear section, is noticeably slimmed down relative to previous years; however, this is because the format of the report has changed to focus on newer information, rather than repeating and reaffirming older assessments. As a result, this year’s report includes no mention of China’s ballistic missile submarines and their associated missiles, and includes only cursory mention of China’s air-based nuclear capabilities. It also excludes analyses of several types of land-based missiles entirely. However, this does not reflect changed assessments on the part of the Pentagon, but rather a lack of new information to report. Going forward, this means that analysts will need to read multiple years of CMPR reports in order to ensure that they are accessing the complete range of available information.

In addition, this year’s CMPR did not include any mention of China’s September 2025 Victory Day parade––which featured multiple new weapon systems––as the parade took place too recently; it will very likely be analyzed in next year’s report. The maps of missile base and brigade locations also appear to be out of date: the information is listed as “current as of 04/01/2024.”

While this year’s report did not include any earth-shattering headlines with regards to China’s nuclear forces, it provides additional context and useful perspectives on various events that took place over the past 12 months.

Stockpile growth

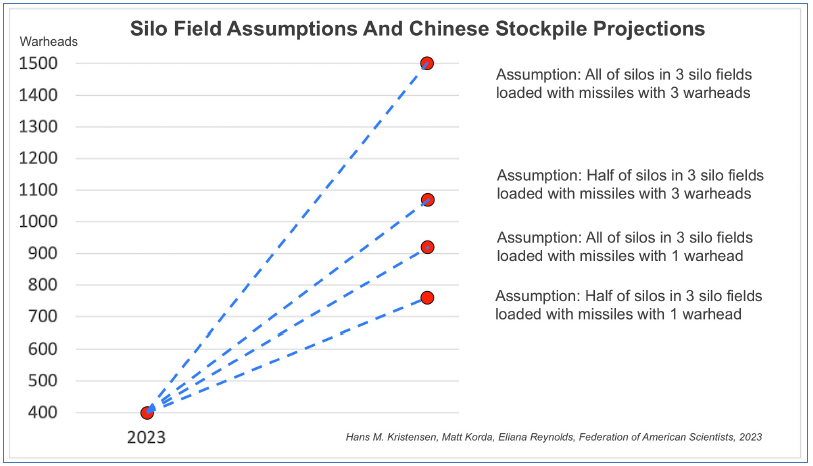

The CMPR states that China’s nuclear stockpile “remained in the low 600s through 2024, reflecting a slower rate of production when compared to previous years.” However, it reaffirmed previous years’ assessments that China “remains on track to have over 1,000 warheads by 2030.” China’s nuclear expansion over the past five years is now making this projection increasingly plausible, although even if it came to pass, China would still maintain several thousand warheads fewer than either the United States or Russia. Previous CMPRs had assessed that if China’s modernization pace continued, it would likely field a stockpile of about 1,500 warheads by 2035; however, this assessment has not been included in the CMPR since the 2022 iteration.

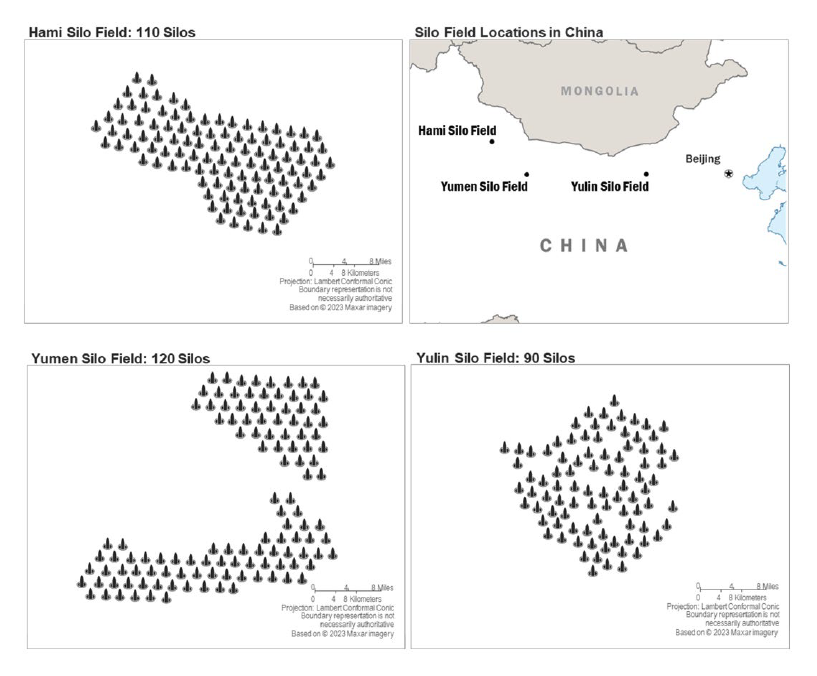

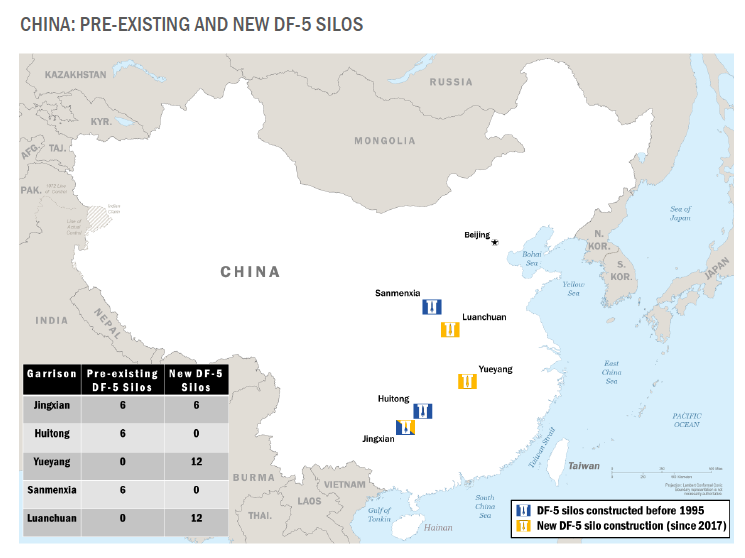

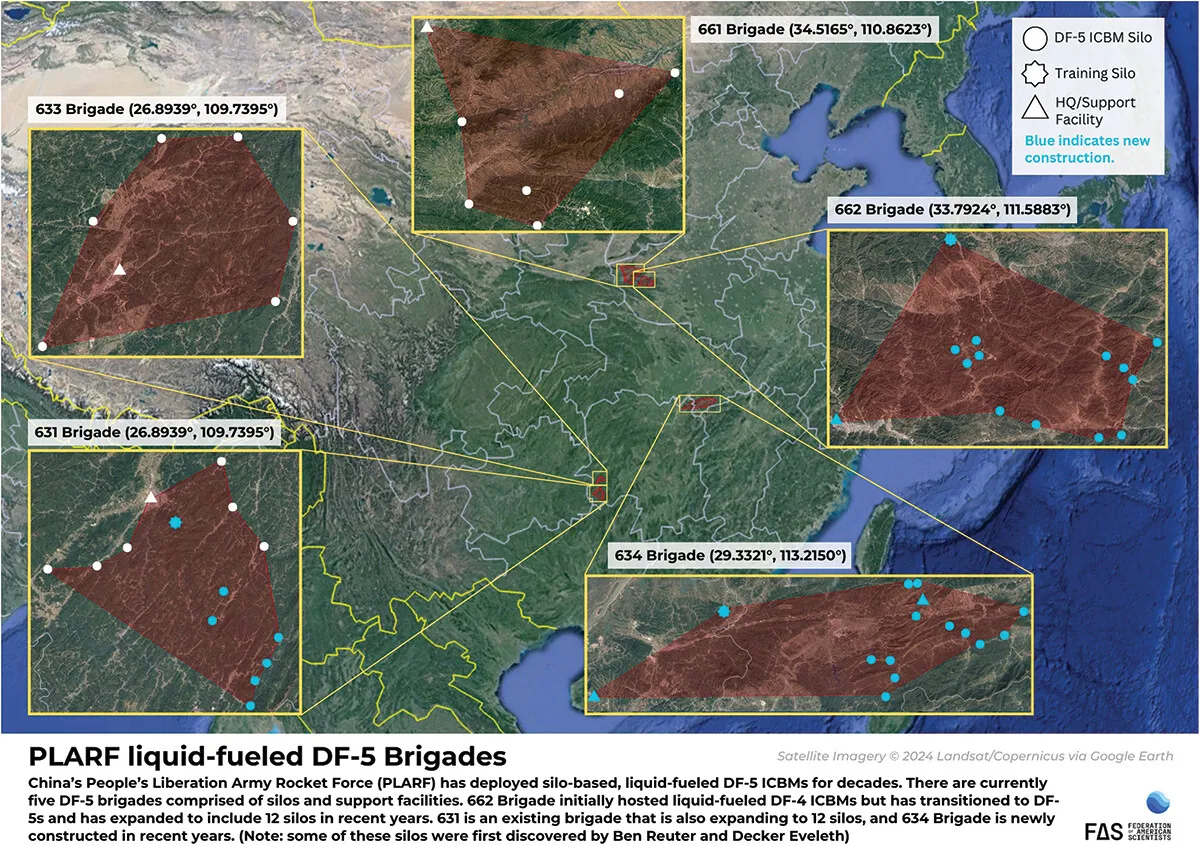

The dramatic expansion of China’s stockpile is primarily being prompted by the large-scale development and modernization of China’s next-generation intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) forces. In 2021, multiple non-governmental organizations (including our team at the Federation of American Scientists) publicly revealed the existence of three new ICBM silo fields capable of hosting up to 320 launchers for solid-propellant DF-31 class ICBMs. China is also more than doubling its number of silos for its liquid-fuel DF-5 class ICBMs, which the Pentagon assessed in its 2024 CMPR will likely yield about 50 modernized silos. Many of these missile types will be capable of carrying multiple warheads.

While the previous year’s CMPR indicated that China “has loaded at least some ICBMs into these silos,” the 2025 edition offers a valuable update: that China has now “likely loaded more than 100 solid-propellant ICBM missile silos at its three silo fields with DF-31 class ICBMs.” Our team continues to regularly monitor developments at the three silo fields using commercial satellite imagery and has not yet found sufficient evidence to corroborate this assessment; however, it is possible that the Pentagon’s assessment is primarily derived from other sources of intelligence, including human (HUMINT) and/or signals intelligence (SIGINT).

If China plans to continue its nuclear expansion, it will likely require additional fissile material, as China does not currently have the ability to produce large quantities of plutonium. The Pentagon assesses that China’s ongoing construction and planned commissioning of two new CFR-600 sodium-cooled fast breeder reactors at Xiapu “will reestablish China’s ability to produce weapons-grade plutonium.” However, the 2025 CMPR assesses that the first unit “is probably still undergoing testing,” and that “the second reactor unit is still under construction.” It is possible that this information is now out of date, as recent commercial satellite imagery now suggests that the first reactor unit may be operational.

Low-yield warheads

Previous editions of the CMPR had indicated that China was “probably” seeking low-yield warheads for escalation control during periods of small-scale nuclear crisis and/or conflict; however, the 2025 iteration is the first to offer an estimated yield value for such weapons, of “below 10 kilotons.” A recent technical history by Hui Zhang offers highly valuable data points for historical Chinese nuclear weapons tests, and suggests that China likely has the ability to produce smaller, low-yield warheads. Additionally, recent open-source reporting by Renny Babiarz with Open Nuclear Network (ONN) and researchers from the Verification Research Training and Information Center (VERTIC) found that China has been overhauling and expanding its warhead component manufacturing capabilities. Coupled with the expansion of the Lop Nur test site, this could indicate plans to upgrade China’s existing warheads, improve its ability to build more, or both.

The CMPR notes that the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) and the air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) carried by the H-6N bomber “are both highly precise theater weapons that would be well suited for delivering a low-yield nuclear weapon.” While the DF-26 had previously been identified as a likely carrier for a low-yield warhead, this is the first time that the H-6N’s ALBM has also been listed as a potential carrier.

Missile designations

It is often a complex endeavor to try and match China’s own missile designations to the names that are given to various systems by the Pentagon. This year’s CMPR, however, provides valuable confirmations for some of these missile designations. In particular, it confirms that both the DF-31A and DF-31AG ICBM are known to the Pentagon as CSS-10 Mod 2, which aligns with our understanding that both systems carry the same missile. It also strongly hints at the alignment between the CSS-18 and the DF-26 IRBM, as well as the CSS-10 Mod 3 and the DF-31B ICBM––a missile that was confirmed in the 2025 CMPR as the same missile that was launched from Hainan Island into the Pacific Ocean in September 2024 for the first time since 1980. This was the first mention of the DF-31B in the CMPR since the 2022 edition, and the first time that the missile’s existence under that designation has been confirmed.

The acknowledgement of the DF-31B’s existence coincides with the recent reveal of a likely silo-based version of the same missile during China’s September 2025 military parade. During that event, China unveiled a vehicle carrying a canister with the designation “DF-31BJ;” it is possible that the vehicle was a missile loader and the “J” likely indicates a silo basing mode, as the Chinese character “井” or “jing” means “well” and is used by the PLA to describe silos. We can therefore assume that the DF-31B ICBM has both a mobile and a silo basing mode, with the latter adding the J suffix to its designation.

Doctrinal shifts, arms control, and early warning

Beyond tweaks to China’s force posture and nuclear stockpile, the CMPR also offers some additional details with regards to its assessment of China’s nuclear doctrine. In particular, it expands on its previous assessments of China’s pursuit of an “early warning counterstrike (EWCS) capability,” which it calls “similar to launch on warning (LOW), where warning of a missile strike enables a counterstrike launch before an enemy first strike can detonate.” For the first time, the CMPR offers details into the capabilities of China’s early warning systems, stating that “China’s early warning infrared satellites [Tongxun Jishu Shiyan (TJS), also known as Huoyan-1] can reportedly detect an incoming ICBM within 90 seconds of launch with an early warning alert sent to a command center within three to four minutes.”

It also notes that China’s ground-based, large phased-array radars “probably can corroborate incoming missile alerts first detected by the TJS/Huoyan-1 and provide additional data, with the flow of early warning information probably enabling a command authority to launch a counterstrike before inbound detonation.” If this is accurate, it would appear that China is developing an early warning capability that functions in a similar manner to those of the United States and Russia, which rely on dual phenomenology to confirm the validity of incoming attacks before authorizing retaliatory launches.

The report also notes that “Beijing continues to demonstrate no appetite for pursuing […] more comprehensive arms control discussions,” including those related to a potential US-China bilateral missile launch notification mechanism.

Corruption

The CMPR focuses quite a bit on China’s ongoing measures to combat corruption, which has led to the removal of dozens of senior officials from their posts across the PLA Air Force, Navy, and Rocket Force. The report notes that “[c]orruption in defense procurement has contributed to observed instances of capability shortfalls, such as malfunctioning lids installed on missile silos”––a story which Bloomberg first reported in January 2024. The report notes that “these investigations very likely risk short term disruptions in the operational effectiveness of the PLA.”

Missiles and delivery systems

The 2025 report included a detail that in December 2024, “the PLA launched several ICBMs in quick succession from a training center into Western China.” Contrary to the launch from Hainan Island, there was very little public reporting about this salvo launch.

The CMPR also indicates an estimated growth in China’s ICBM and IRBM launchers by 50 each, although it is unclear whether these numbers include both finished launchers as well as those still under construction.

The following graph indicates the growth of China’s launchers and missiles, as assessed by the Pentagon, over the past 20 years. It is important to note that many of these missiles, including China’s short- and medium-range ballistic missiles and its ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCMs), are not nuclear-capable.

Our 2025 overview of China’s nuclear arsenal can be freely accessed here.

The Nuclear Information Project is currently supported with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

Tracking the DF Express: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Chinese Media and Public Data for Studying Nuclear Forces

Observers of Chinese nuclear politics and force posture are old friends with information challenges. Open-source analysts of China’s nuclear force drew heavily on published Chinese-language writings, footage, and interviews by official Chinese media or private Chinese citizens, as well as commercial satellite imagery. These powerful open-source tools enable scholars to gain insight into some of the Chinese government’s most closely guarded secrets, such as the construction of 119 nuclear missile silos. Reports from well-regarded institutions, such as the PLA Rocket Force Order of Battle report by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, offer open-source research that provides concrete data on the Chinese nuclear force, using thoroughly analyzed imagery and Chinese-language materials. Other studies, such as several reports by the RAND Corporation and the Air University’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), extensively used Chinese military and technical writings to identify patterns in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s strategic thinking in its own words. Combined with the Federation of American Scientists (FAS)’s annual report on nuclear forces, there is a growing and vibrant open-source intellectual community on the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF).

While researchers continue to dissect new information from China, obtaining reliable data has become increasingly difficult for two reasons. First, the Chinese government has curtailed foreign access to sources like academic databases that were previously fair game for scholarly use, complicating the already dense “information fog” over China’s political and military apparatus. Second, unverified, digitally altered, and AI-generated disinformation and misinformation are commonplace on popular social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter). Combined with the multitude of Chinese social media and video websites, weeding out the noise and distraction has become an increasingly challenging task for new researchers in this field.

This essay provides introductory guidance on the usefulness of Chinese social media and video platforms for observers and researchers of China’s nuclear force. This guide may assist researchers in identifying what to look for and on which platform, especially for those who are not advanced or native speakers of Mandarin. In the sections below, I compare a set of popular Chinese social media platforms and discuss the usefulness of each with respect to open-source study of the Chinese nuclear force. I also present a brief glossary of nicknames and vernacular terms related to nuclear matters in Mandarin, along with their translations. I conclude with a brief discussion of the use of AI-enabled translation tools for open-source research on the PLA.

Chinese media and OSINT: What’s good for what?

Sina Weibo (新浪微博)

Weibo is useful for providing timely, authoritative, and chronologically documented information on training exercises, operations, and policy changes that are of propaganda or morale-promoting value. The equivalent of X in China, Weibo is the biggest Chinese-language social media with over 500 million monthly active users as of 2024. It is likely the most influential social media platform in China, as indicated by the vast number of users and a highly agile and effective censorship system. Due to Weibo’s ability to rapidly disseminate information, all major state and military organs, including the PLA Daily, the Ministry of Defense, individual service branches, and all five PLA Theater Commands (战区), maintain official accounts on Weibo (Figure 1). These accounts are directly managed by dedicated propaganda or public affairs teams and authorized to post military content, which sometimes features approved footage and photos of training exercises. Details revealed in the footage or pictures may help researchers identify the unit leadership and the weapon systems used during the exercise. Additionally, Weibo is often the first platform to announce state media PLA news. The People’s Daily, CCTV, and the Xinhua Agency regularly post links to news articles and updates on Weibo to facilitate dissemination.

For researchers, Weibo contains a reasonably reliable search system. Researchers may use the Weibo search bar to look for mentions of “strategic deterrence,” “nuclear force,” or names of nuclear missiles and use the filter function to screen for content released by official accounts. For well-publicized events like a missile exercise, the topic may be included in the trending (热搜) section for real-time updates. However, a significant limitation of Weibo is that scholars must distinguish whether the content posted by the official accounts directly reflects the Party’s policy or simply shows a lower-level interpretation of the policy by individual units. These official accounts are likely managed by young, tech-savvy officers or civilian employees trained in public affairs.

Sometimes, these individuals might improvise and go beyond what they were prescribed. Some more active accounts, such as the Eastern Theater Command official account, have interacted with random Weibo users in the past and have eagerly implied their belligerent stance toward Taiwan. This led many Chinese netizens to interpret the official account’s posts as a sign of imminent military action, which thankfully was not the intention. Additionally, state-run accounts have also taken down content (primarily propaganda material) for reasons other than revealing unapproved or sensitive information. Again, since the accounts are likely managed by younger personnel at the lower level, contents could be removed when it was later found to be too politically sensitive or too unpersuasive. In 2019, the People’s Liberation Army Army (PLAA) official account posted a propaganda article on Weibo aimed at inspiring nationalistic fervor. It quoted a passionate patriotic poem written by Wang Jingwei (汪精卫), whom the Chinese government considered a “traitor (汉奸)” for cooperating with the Imperial Japanese invaders, most likely because the editor had known about the poem but not its authorship. The comment section quickly pointed out this “political mistake (政治错误)”, leading to the content’s prompt removal. As such, researchers should be aware that removed content does not necessarily suggest valuable information worth hiding.

It is also important to note that accessing Weibo sometimes involves more than typing in the URL. Aside from the content available on the front page (e.g., the trending section), the rich content of the platform is only accessible after logging in. One does not need a mainland Chinese phone number to create an account on Weibo. A virtual number from a trusted provider is also sufficient. Even without an account, researchers could still access the Weibo homepage of many accounts by searching the account’s name in a search engine (for instance, here is the direct link to the official PLA Eastern Theater Weibo page). However, Sina Weibo’s search bar will not be available for unregistered users.

CCTV.com (央视网)

CCTV.com is a webpage that gives scholars access to the state media’s TV programs without a registered account. In addition to live-streamed news stories, the webpage also serves as a large but incomplete archive of past TV programs. CCTV.com has high-definition PLA video footage and interviews, which may be particularly useful for open-source analysis. Some of the CASI reports made clever use of video footage released by Chinese state media to identify key information regarding training exercises and unit deployment, particularly the CCTV-7 channel dedicated to military content. Other open-source intelligence analysts were able to map out key personnel, location, and weapon system information from CCTV news broadcasts and military TV programs. The search bar supports keyword searches and includes government-sponsored TV programs from various channels. The search also returns results from CCTV webpages and the Xinhua Agency. This is the most useful for finding information related to specific missile systems. For instance, among the top results for “DF-26” include footage of a DF-26 missile from a documentary (Figure 2). The search result for “dual-capability” also returned a video by a Chinese military commentator who states that China’s hypersonic vehicle is dual-capable (Figure 3). For open-source analysis, having the ability to revisit footage that might contain useful information on the PLARF is a major advantage of this platform. At the same time, the search function is limited to the titles of the program, not necessarily the content. Furthermore, many of the videos available on CCTV.com are commentaries from Chinese military experts. While the commentary from the Chinese experts may be useful, the visual component may not always be the latest developments. Because of the length requirement of the TV program, the visual element may only have looped videos of known weapon testing or parade footage. Researchers may consider comparing the footage from different programs to remove the repeated material.

Bilibili (哔哩哔哩), Douyin (抖音), Kuaishou (快手)

Bilibili, Douyin, and Kuaishou are among the most used entertainment video-sharing and short-video platforms in China. Bilibili is a video service primarily for animation, comics, and games (ACG) content. It has a “bullet comment (弹幕)” function that allows users to inject text over the video content in real time. The platform attracts over 100 million daily users as of 2024. Douyin (the Chinese mainland version of TikTok) and Kuaishou are short-video platforms with a significantly larger user base than Bilibili, with Douyin content reaching over 1 billion active users monthly. Unsurprisingly, the PLA, the individual Theater Commands, and the Chinese government and Party organs maintain an active presence on these platforms for propaganda, news updates, and publicity programs, often repeating the same message sent across other outlets.

However, despite these platforms’ popularity, they are not great resources for open-source nuclear force research for two reasons. First, there is overwhelming noise from private click-farming content creators who would grossly overstate or fabricate China’s military capabilities to profit from nationalistic sentiments. A researcher may find many videos speculating about the capabilities of the H-20 bomber with no credible source to back up the claims. Private content creators typically have no privileged access to information. In the rare cases where some villagers filmed a rocket booster falling from the sky (some Chinese rocket boosters in the past landed in populated villages), the video is often quickly censored on these closely watched platforms. Second, official government accounts on these platforms almost always repeat information that has been released on Weibo and other traditional news platforms. Some Party organs, such as the Communist Youth League (共青团), which pushes propaganda to the younger generation, would convey the same approved message using CGI videos to boost nationalist sentiment, but the content itself is no more useful than reading the official news release. Overall, there is little added advantage of using the entertainment-based services for potentially useful open-source information.

Combining Sources

While Chinese video and social media platforms could assist OSINT research on China’s nuclear forces, researchers could also combine the visual element of weapon systems with textual data gathered from authoritative Chinese platforms like China Military Online (中国军网), PLA Procurement website (军队采购网), and Qi Cha Cha (企查查). The visual data can help identify many technical aspects of the PLA’s nuclear weapons, but the textual information can greatly inform the acquisition, production, and deployment of the weapon and support systems. Provinces with robust military and heavy industries, such as Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Shandong, and Shaanxi, sometimes release contracting and procurement information locally on provincial and municipal government websites. The information found on local government websites is admittedly sporadic, making broad, systematic collection difficult. Still, such information could serve as valuable first-hand sources for OSINT researchers. For more technical analysis of weapon systems, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (中国国家知识产权局) has a patent database that could be useful to track the development and ownership of certain enabling technologies for nuclear systems. This may be further enhanced by using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (中国知网CNKI) to locate academic articles on the relevant technology, though access to CNKI articles usually requires an institutional subscription through a university library. Note that many of the Chinese government and military websites do not support a secure HTTPS connection. Some, like Qi Cha Cha, may require the user to access its content from a Chinese mainland IP address. Researchers should deploy cybersecurity tools to take full advantage of these resources.

Nicknames and Vernacular

In addition to the advantages and limitations of different social media platforms, researchers should be aware of the common nicknames and vernacular related to the Chinese nuclear force. Much like how the F-16 is commonly called “viper” instead of the official name “fighting falcon,” there are also nicknames for weapons and systems in the PLA. The table below summarizes several common terms and explains their meaning and primary usage.

A Note on Using AI Translation Services

There is little doubt that AI-enabled translation services like DeepL offer convenient and mostly accurate translations of Chinese texts. However, users should exercise caution when asking the AI to translate lengthy or complicated Chinese texts. Since the Chinese written language system is not space-delimited and often contains a mix of recently invented slang words, formal, and classical Chinese (文言文) phrases and quotes, the translation software sometimes cannot adjust properly to the context in which the classical phrases are used. This could easily lead to misinterpretation.For instance, translating and searching for the phrase “nuclear force (核力量)” may return results that contain the phrase “hardcore power (硬核力量)”, which is unrelated to nuclear weapons. In another example, a PLA Daily article uses the phrase “北约军费连增虚实几何” as the title, which mixes the classical grammar with modern Mandarin. DeepL would translate the word “几何” as “geometry” because it is the most used meaning in modern Mandarin, whereas the correct interpretation is “to what extent” or “by how much” in this context (Figure 4).

In a similar instance, DeepL entirely fails to translate the part that contains classical grammar and offers an incorrect translation (Figure 5). This is most likely because the software treats the original Chinese phrase as a statement, whereas the classical grammar indicates a question.

Therefore, it is prudent to cross-reference and look up phrases individually when using AI-enabled translation tools. Inserting complete paragraphs is likely less accurate than looking up difficult phrases or individual vocabulary.

Conclusion

This paper provides a preliminary guide on using Chinese social media and video platforms for nuclear-related open-source research by reviewing the usefulness and credibility of the content released by various official and privately owned platforms (Table 2). In sum, there is no singular most useful platform for information on the Chinese nuclear force, but some may help piece together interesting findings upon cautious review and cross-reference. While advanced Chinese language proficiency and cultural familiarity remain irreplaceable skills that can greatly enhance the accuracy and speed of open-source analysis, they are neither necessary nor sufficient for successful open-source analysis on China’s nuclear forces. Researchers can still make effective and efficient use of publicly available information by applying analytical due diligence and having context-specific awareness of Chinese sources.

This publication was made possible by a generous grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Understanding the Two Nuclear Peer Debate

Since 2020, China has dramatically expanded its nuclear arsenal. That year, the Pentagon estimated China’s stockpile of warheads in the low 200s and projected that it would “at least double in size.”1 Two years later, the report warned that China would “likely field a stockpile of about 1500 warheads by its 2035 timeline.”2 Both inside and outside government, the finding has transformed discourse on U.S. nuclear weapons policy.

Adm. Charles Richard, while Commander of U.S. Strategic Command, warned that changes in China’s nuclear forces would fundamentally alter how the United States practices strategic deterrence. In 2021, Richard told the Senate Armed Services Committee that “for the first time in history, the nation is facing two nuclear-capable, strategic peer adversaries at the same time.”3 In his view, China is pursuing “explosive growth and modernization of its nuclear and conventional forces” that will provide “the capability to execute any plausible nuclear employment strategy.”4 In Richard’s view, the United States is facing a “crisis” of deterrence that will require major shifts in U.S. nuclear strategy.5 “We’re rewriting deterrence theory,” he told an audience.6 For Richard, the danger is not just that the United States would face two separate major power, nuclear-armed adversaries but two nuclear peers that can coordinate their actions or act to exploit opportunities created by the other.

How the United States responds to China’s nuclear buildup will shape the global nuclear balance for the rest of the century. For many observers, the “two nuclear peer problem” presents an existential choice because existing U.S. nuclear force structure and strategy cannot maintain deterrence against two nuclear peers simultaneously. There are only three options: expand the capability of U.S. nuclear force structure; shift nuclear strategy to engage nonmilitary targets;7 or do nothing, which increases the risk of regional aggression and nuclear use.

Despite this growing wave of concern and commentary, there has been no systematic studies that define the nature of the “two nuclear peer problem” and the options available to the United States and its allies for responding to China’s nuclear buildup. An informed decision about how to respond to China’s buildup will depend on answering two additional questions.

First, what exactly is the threat posed by China’s expanding nuclear forces? What is a “two nuclear peer problem” and will the United States face one in the next decade? Specifically, will China’s nuclear buildup render U.S. nuclear forces incapable of attaining critical objectives for deterring nuclear attacks.

Second, what are the best options for responding to China’s expanding nuclear forces? What are the available options to modify U.S. nuclear force structure given existing constraints and will these options effectively correct vulnerabilities created by a “two nuclear peer problem?” Would these options create new risks to the interests of the United States and its allies?

In the following chapters, we each consider a central aspect of the “two nuclear peer problem” and the options available to meet it. Though we have tried to coordinate our chapters so they do not overlap, and build on assumptions and data regarding U.S. and Chinese nuclear forces, each chapter is the work of a single author. We do not present a consensus perspective or set of recommendations and do not necessarily endorse the arguments made in neighboring chapters.

In chapter 2, Adam Mount surveys expert analysis and the statements of government officials to develop a more rigorous definition of the “two nuclear peer problem” than currently exists in the literature. Characterizing and categorizing the risks posed by a tripolar system leads to an unappreciated possibility: there is no “two nuclear peer problem” in the way that the problem is commonly presented. As it stands today, the prominent and influential discourse on the “two nuclear peer problem” does not clearly or accurately characterize the risks posed by China’s expanding nuclear forces, nor the range of options available to U.S. officials to respond. The need to deter two nuclear adversaries does not necessarily create a qualitatively new problem for U.S. strategic deterrence posture.

Subsequent chapters evaluate important pieces of the “two nuclear peer problem” in detail. In chapter 3, Hans Kristensen presents new estimates of U.S. and Chinese force structure to 2035. He provides correctives against excessive estimates of China’s current and future capability and argues it should not properly be considered a nuclear peer of the United States.

The final chapters consider two plausible ways that a tripolar system could present a qualitatively new threat to U.S. deterrence credibility. In chapter 4, Pranay Vaddi considers how China’s buildup will affect U.S. nuclear strategy. He surveys how U.S. planning has historically approached China and evaluates multiple courses of action for how the United States might adapt. In chapter 5, John Warden examines the prospects for Sino-Russian cooperation in peacetime, in crisis, in conventional conflict, and in a nuclear conflict. He argues that it is not only the material facts of China’s buildup that will drive U.S. planning, but the expectations and risk acceptance of U.S. officials with respect to Sino-Russian coordination and U.S. extended deterrence commitments.

The authors are grateful to Carnegie Corporation of New York for their generous funding of the project, as well as innumerable colleagues, academics, and government officials for informative discussions. The authors each write in an independent capacity. Their chapters do not reflect the positions of any organization or government.

Nuclear Weapons At China’s 2025 Victory Day Parade

On September 3, 2025, China showcased its military power in a parade commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the end of World War II. The parade featured a large number of new military weapons and equipment, including new and modified nuclear systems that had not been previously publicly displayed. This parade was also the first time China had showcased land-, sea-, and air-launched nuclear weapons in the same parade, marking an important milestone in the country’s longtime effort to establish a nuclear triad.

As in some previous parades, the official announcer for the 2025 parade clearly distinguished between the nuclear and conventional weapon systems displayed during the parade. Hypersonic missiles such as the DF-17 and the DF-26D were grouped in conventional formations, whereas the five weapon systems that followed were explicitly referred to as being part of the nuclear formation. This language may be innocuous, but largely fits with Western descriptions of the weapons.

Although only one of the nuclear weapons presented at the parade was entirely new (the DF-61 ICBM), that and the many other systems displayed in this and previous parades – combined with the construction of three large missile silo fields and so far more than a tripling of the nuclear warhead stockpile – vividly illustrate the significant modernization and buildup of nuclear forces that China has undertaken over the past couple of decades. This buildup appears to contradict China’s obligations under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and risks stimulating nuclear buildups in the United States and India – developments that would not be in China’s interest. Instead of building up the nuclear arsenal, the Chinese leadership instead should freeze it and work with the other nuclear-armed states to responsibly limit the numbers and roles of nuclear weapons.

In the sections below we describe the nuclear weapons displayed at the parade and their role in the Chinese nuclear posture.

Ground-based nuclear missiles

Based on new information from the parade footage, it seems China now has nine different versions of land-based ICBMs: DF-5A, DF-5B, DF-5C, DF-27 (not yet displayed in public), DF-31A, DF-31AG, DF-31BJ, DF-41, and DF-61. Interestingly, rather than necessarily representing incremental upgrades, many of the missiles are quite distinct from one another: five are road-mobile, and four are silo-based; three are liquid-fueled, four are solid-fueled, and two are unconfirmed; at least one carries MIRVs, at least one carries an HGV, at least one carries a multi-megaton warhead, and one may even carry a conventional warhead.

The DF-61

The DF-61 is a new missile that was grouped alongside the DF-31BJ, JL-3, and JL-1 nuclear systems during the parade, suggesting it is also nuclear. The display of the DF-61 ICBM launcher was a surprise because the Chinese Rocket Force (PLARF) is still fielding the DF-41, and the two systems are strikingly similar. In fact, the DF-61 launcher displayed at this year’s parade appears to be nearly identical to the DF-41 launcher displayed in the 2019 parade. Other than the paint job, they look the same (see image below; image sizes and angles vary slightly). This raises the question of whether the DF-61 missile is a modified version of the DF-41 missile. Another possibility is that the DF-61 is the conventional ICBM rumored to be under development by China, but that doesn’t fit with the DF-61 being displayed as part of the nuclear group. (Instead, the conventional ICBM could be the DF-27, which was not displayed at the parade.)

The DF-61 ICBM launcher displayed at the 2025 Victory Day Parade looks almost identical to the DF-41 ICBM launcher displayed in 2019.

The DF-31BJ

The vehicle identified in the parade as DF-31BJ looks different than a road-mobile launcher with its stub end of the missile canister and the personnel compartment only including the left side for the driver (see image below). It is possible that this vehicle is a missile loader and the DF-31BJ is the designation of the ICBM assigned to the three large silo fields in northern China. The “J” likely denotes the silo basing, as the Chinese character “井” or “jing” means “well” and is used by the PLA to describe silos.

The DF-31BJ is possibly a missile transport loader for the ICBMs being loaded into China’s three large silo fields.

The DOD reported last year that China probably began loading a DF-31-class solid-fuel ICBM across its three new ICBM silo fields. To do that, a missile transport and loading truck would be needed, which might be the DF-31BJ displayed at the parade. The status of the silo loading is unknown in public, but we estimated early this year that perhaps 30 silos had been loaded. While silo loading at the three silo fields has not been publicly shown, a possible load training operation at the Jilantai training complex in 2021 shows a 20-meter truck that might have been an early version of the DF-31BJ (see image below).

A possible DF-31BJ missile transporter is seen in 2021 practicing loading an ICBM into a silo at the Jilantai training complex in northern China.

The DF-5C

The long-rumored DF-5C was displayed with all three sections: the first stage on a long trailer at the rear, the upper stage on a shorter trailer, and a warhead reentry vehicle shape in the front. This is similar to the first display of the original DF-5 at the parade back in 1984 (see image below).

The DF-5C ICBM lineup in the 2025 parade is similar to the initial DF-5 display in the 1984 parade four decades ago.

The DF-5C is, according to the DOD, intended to carry a multi-megaton warhead. As such, it is probably a replacement for the DF-5A first deployed in the 1980s, which is already equipped with a multi-megaton warhead. Another version, known as the DF-5B, is capable of delivering up to five smaller MIRVs.

Similar to the DF-5 in the 1984 parade, the four DF-5Cs were displayed with four cone-shaped reentry vehicle shapes intended to illustrate the aeroshell designed to protect the multi-megaton warhead during reentry of the atmosphere (see below).

The 2025 parade displayed the reentry vehicle shape for the DF-5C multi-megaton warhead.

Sea-based nuclear missile

The Chinese Navy displayed the JL-3 (Julang-3) sea-launched ballistic missile, which is currently being back-fitted onto modified Jin-class (Type 094A) ballistic missile submarines at their homeport on Hainan Island in the South China Sea.

The JL-3 displayed at this year’s parade (above) looks very similar to the JL-2 displayed in the 2019 parade (below), with no visible external changes to the payload section or fuel stages.

The JL-3 has a longer range than its predecessor, JL-2, probably around 10,000 kilometers, according to the DOD. Although the DOD claims this is “giving the PRC the ability to target [the continental United States] from littoral waters,” that is not the case if the missile is launched from the South China Sea. Launching from the shallow Bohai Sea or the Yellow Sea would probably be less secure.

Air-delivered nuclear missile

For the first time, China displayed a nuclear weapons system for delivery by aircraft. This is the JL-1, or JingLei-1, translating to “sudden thunder” (not to be confused with the JL-3 or Julang-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile, which translates to “massive wave”). The official parade commentator described it as an “air-based long-range missile.”

The JL-1 air-launched ballistic missile for the H-6N bomber was displayed in the 2025 parade for the first time.

This is likely the air-launched ballistic missile (designated CH-AS-X-13 by the DOD) that the Chinese air force has been working on for several years to integrate on the H-6N intermediate-range bomber. The first bomber base to be equipped for the nuclear mission is thought to be Neixiang air base in Henan province.

The JL-1 ALBM seen loaded on the H-6N bomber. Image: @lqy99021608

The H-6N does not have an intercontinental range like Russian and U.S. bombers. To increase its range, the H-6N has been equipped with a refueling boom that enables the bomber to refuel during flight. Several H-6Ns were seen during the parade flying in formation with Y-20U tankers (the quality of images from the parade was hampered by air pollution, so an archive photo is used below), which is a converted Y-20 military transport aircraft that can refuel both bombers and fighter jets. The first known public imagery of an H-6N by a Y-20U tanker is from January 2025.

The nuclear-capable H-6N was displayed with a Y-20U tanker (archive photo).

Other Missile Launchers

The weapons described above were grouped in the nuclear part of the parade. Noticeable weapons in the conventional weapons lineup included the DF-26D (a new conventional variant of the DF-26 that also includes a nuclear version), the DF-17 medium-range hypersonic glide vehicle, and the CJ-1000 (sometimes also described as DF-1000) long-range cruise missile.

Additional Information:

• Chinese nuclear weapons, 2025

• Status of world nuclear forces

• The FAS Nuclear Information Project

This article was researched and written with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

Chinese Nuclear Weapons, 2025: Federation of American Scientists Reveals Latest Facts on Beijing’s Nuclear Buildup

Washington, D.C. – March 12, 2025 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) today released “Nuclear Notebook: China” – its authoritative annual survey of China’s nuclear weapons arsenal. The FAS Nuclear Notebook is considered the most reliable public source for information on global nuclear arsenals for all nine nuclear-armed states. FAS has played a critical role for almost 80 years to increase transparency and accountability over the world’s nuclear arsenals and to support policies that reduce the numbers and risks of their use.

This year’s report, published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, shows the following nuclear trends:

- The total number of Chinese nuclear warheads is now estimated to include approximately 600 warheads. The vast majority of these are in storage and a small number—perhaps 24—are deployed.

- China is NOT a nuclear “peer” of the United States, as some contend. China’s total number of approximately 600 warheads constitutes only a small portion of the United States’ estimated stockpile of 3,700 warheads. While the United States has a fully established triad of strategic forces, China is still working to develop a nuclear triad; the submarine-based leg has significantly less capability, and the bomber leg is far less capable than the United States.

- China continues to see their land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) as their most reliable and survivable nuclear force. China continues to prioritize its land-based force and increase its role in both number and capability. China has completed construction of its three new ICBM silo fields, one of which was publicly disclosed by FAS in 2021. We estimate that around 30 silos have been loaded. China has also increased the number of road-mobile ICBM bases.

- China is continuing to develop its relatively small ballistic missile submarines (SSBN) force through improved missiles and a follow-on SSBN class. Production of the new “Type 096” SSBN has been delayed. We estimate that Chinese SSBNs are now conducting continuous patrols with nuclear weapons on board. However, Chinese SSBNs cannot target continental United States from their operating areas.

- Development of a viable nuclear bomber force is still in its early stages. Only one base has been established at Neixiang for the new H-6N bomber. The H-20 replacement bomber appears to be delayed.

FAS Nuclear Experts and Previous Issues of Nuclear Notebook

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The joint publication began in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenal and their role.

This latest issue on the United State’s nuclear weapons comes after the release of Nuclear Notebook: United States on America’s nuclear arsenal. More research available at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Winning the Next Phase of the Chip War

Last year the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), Jordan Schneider (of ChinaTalk), Chris Miller (author of Chip War) and Noah Smith (of Noahpinion) hosted a call for ideas to address the U.S. chip shortage and Chinese competition. A handful of ideas were selected based on the feasibility of the idea and its and bipartisan nature. This memo is one of them.

Summary

- Danger Ahead: Until now, the U.S. semiconductor policy agenda focused on getting an edge over China in the production of advanced semiconductors. But now a potentially even more substantial challenge looms. Possible Chinese dominance in so-called ‘legacy’ chips essential for modern economic life could grant it unacceptable leverage over the United States. This challenge will require tools far more disruptive than ever before considered by policymakers for the chip competition.

- The Foot on America’s Economic Neck: Collecting offensive economic leverage lies at the heart of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s strategy. Chinese dominance in legacy chips could enable Beijing’s bullying of the United States it has thus far reserved for U.S. allies. China’s growing leverage over Washington may embolden Beijing to think it could attack Taiwan with relative impunity.

- Familiar Semiconductor Policy Tools Won’t Work Alone: China increasingly has access to the tech it needs for its legacy ambitions (via stockpiling and indigenization), damaging possible expanded export controls. And unfair Chinese trade practices could reduce the benefits of subsidies, as it has for solar and critical minerals.

- Learning to Love Trade Protection: Only when the U.S. market cannot access Chinese chips will they have sufficient incentive to manufacture chips in third countries. Washington could either turn to tariffs or outright bans on Chinese chips. Washington has several options to block China’s chips – AD/CVD, 337, ‘ICTS’, 5949, and 232. But the most powerful tool would be Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974.

- The Keys to Success: Trade measures will have to target Chinese chips contained within other products, not just the chips themselves. The U.S. government’s clarity into global supply chains will have to grow dramatically. Allied participation and knowledge-sharing might be needed. The United States can ease enforcement of a chips trade war by incentivizing private industry to share the burden of detecting violations of U.S. law.

The Generational Leap in U.S. Chip Policy

For five years, U.S. concerns over China’s semiconductor sector focused on its cutting-edge chip production. The bipartisan instinct has been to mix restrictions on Chinese access to Western technology and to fund manufacturing of advanced chips at home. It began with the Trump administration’s sanctions against Chinese chip giants Fujian Jinhua, Huawei, and SMIC. The Biden administration’s October 2022 export controls on China’s advanced chipmakers and the CHIPS and Science Act crowned a new era of technology competition focused on the absolute bleeding edge.

Fast forward to July 2024: Washington entered the next phase of the chip war.

Biden administration concerns about legacy chips emerged subtly last summer from one-off statements from Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo. Before long Team Biden began to formally investigate the issue in an industry survey. Then in May the administration doubled existing tariffs on Chinese-made chips from 25% to 50%.

Congress is equally concerned. The bipartisan China Committee endorsed tariffs on Chinese legacy chips in its December 2023 economic report and in a January 2024 letter to the administration. China’s growing position in the production of mature-node chips took center stage in a Committee hearing in June 2024, where Committee Chair John Moolenaar called for “a reliable domestic supply of semiconductors outside the reach of the CCP”.

This apparently sudden shift reflects the growth of the stakes in the U.S.-China chip competition over the past year:

- Legacy Chips Fuel Modern Life: Cars, aircraft, home appliances, consumer electronics, military systems, and medical devices rely on legacy chips. About 70% of chips produced globally are non-advanced.

- China’s Bid for Legacy Dominance: China already accounts for 30% of global logic chip capacity, a number that is projected to rise to 39% by 2027. And if Beijing makes good on its threats to annex Taiwan, the world’s other major manufacturer of legacy semiconductors, China could potentially control 60% of global production of chips in the range of 20 to 45 nanometers and 75% of overall legacy chip production by 2027.

Despite the scale of the challenge, Washington has not yet decided on its strategy to take on the problem. The best approach to the legacy challenge will be one that can prevent U.S. reliance on Chinese-made chips to ensure China cannot capture decisive leverage over the U.S. economy. Doing so will require using trade measures to reject Chinese chips from the U.S. altogether.

Dominance Means Leverage

China’s fast-rising position in the legacy chip industry threatens U.S. national security because it would grant Beijing extraordinary strategic leverage over the United States. That would encourage Chinese economic coercion and even a war over Taiwan.

2.1. Xi’s Plan for ‘Offensive Leverage’: Geoeconomics lies at the heart of Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s international strategy. The strategy is to exploit foreign dependence on Chinese critical supply chains to accomplish Beijing’s objectives abroad.

Xi himself laid the foundation of this vision in a pair of speeches in 2020 in which he called for economic “deterrence” over the rest of the world. He called for an economic “gravitational field” to “benefit the formation of new advantages for participating in international competition and cooperation”. China would achieve this by heightening “the dependent relationships of international industrial chains on our country, to form a powerful countermeasure and deterrence capability against external parties who artificially cut off supply”, according to Xi.

The Chinese Communist Party’s 2021 Five-Year Plan enshrined these principles in Party jargon, calling for a “powerful domestic market and strong-trading country” to “form a powerful gravitational field for global production factors and resources”. This is often called the “dual circulation” strategy by outside observers. It could more usefully be called “offensive leverage”.

2.2. Beijing’s Bullying Could Come for Washington: Since Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012, China has repeatedly demonstrated these geoeconomic principles by flashing its economic strength to accomplish strategic objectives.

The list of examples of Chinese economic coercion is long. In 2010, China limited Japanese purchases of rare-earth minerals over a Senkaku Islands dispute. Norwegian salmon rotted that same year on Chinese docks in retaliation for dissident Liu Xiaobo winning the Nobel Peace Prize. In 2012, Philippine bananas also rotted over the Scarborough Shoal dispute. In 2016, Beijing conveyed its displeasure toward Seoul for agreeing to host U.S. missile defense systems by squeezing South Korean auto sales in China and slashing Chinese tourism in the country.

This bullying has not slowed since Xi unveiled his economic thinking in 2020. That year, China embargoed Australian wine, barley, wheat, coal, fish, and other products after Canberra passed laws to reduce foreign influence and called for an investigation into the origins of Covid-19.In 2021, China blocked imports of Lithuanian goods over the state opening a “Taiwanese Representative Office”. In just the past month, Beijing has threatened French luxury brands, German car makers, and Spanish pork producers in retaliation for EU duties on Chinese electric vehicles.

Washington faces less blatant coercion compared to its allies. True, China has targeted U.S. firms such Micron over the past few years. But the scale and ambition of this bullying has never approached what China has applied to the likes of Australia and Lithuania. This may be because Beijing does not believe it yet maintains necessary leverage over Washington to brandish its economic blade as it does toward smaller economies.

China’s growing position in the legacy semiconductor market could change that. How would Beijing’s behavior change if sales of the Ford F-150 relied on Beijing’s willingness to sell its semiconductors?

2.3. Reliance Endangers Taiwan: Western European reliance on Russian energy was one factor (among many) that encouraged Vladimir Putin to believe he could invade Ukraine with relative impunity. Likewise, deepening U.S. dependence on China for strategic supply chains could make it far more difficult to challenge Beijing on sensitive geopolitical issues.

The United States already relies on China for other key inputs to its economy: generic pharmaceuticals, critical minerals, solar panels, and printed circuit boards, among others. U.S. reliance on Chinese-made legacy chips – the product at the heart of modern economic life – could be the crown jewel of Chinese geoeconomics. American economic reliance on China could embolden Xi Jinping to think he could attack Taiwan with tolerable penalty.

The Case for Blocking China’s Chips

Familiar semiconductor policy approaches – export controls and subsidies – are inadequate alone to prevent reliance on Chinese-made legacy chips. Washington and its allies will instead have to turn to the old-fashioned, disruptive tools of trade defense in the face of a challenge of this scale.

3.1. It’s Too Late for Export Controls: The crux of current U.S. semiconductor policy toward China is to contain the growth of Chinese advanced chip production by limiting its access to exquisite machine tools produced by the United States and its allies (often called the ‘restrict’ agenda). Without those tools, China will be unable to build the cutting-edge chips that enable AI and advanced weapons.

Why not do the same for legacy chips? Washington and its allies could grow its existing rules so that China could not purchase machines capable of manufacturing legacy chips from Western producers.

The issue is that China increasingly already has the tools it needs for its legacy chip production, in two ways:

- China Has Stockpiled Western Tech: Beginning in 2020, China became the world’s top buyer of semiconductor manufacturing equipment, a strong indicator of future capacity.Over the past year, China has risen to represent nearly half of all sales for Dutch giant ASML and U.S. firm Lam Research. China’s demand is ‘non-market’. As ASML’s CEO put it: “Our Chinese customers say: We are happy to take the machines that others don’t want”.

- Chinese Tools are Replacing Foreign Ones: Chinese semiconductor industrial policy has pivoted in the past two years to cultivate domestic alternatives to Western tech. Advanced Micro-fabrication Equipment, an etching firm competing with U.S. company Lam Research, can produce some kinds of etching equipment for chip production at 5 nanometers and 28 nanometers. Shanghai Microelectronics Equipment, China’s lithography champion, reportedly hopes to reveal soon a machine capable of servicing 28-nanometer manufacturing. Chinese semiconductor players may soon be able to produce legacy chips without Western tech.

Export controls may have worked for the legacy challenge five or ten years ago. It’s unlikely to work alone today.

3.2. Chinese Trade Practices Undermine Subsidies: The second pillar of Washington semiconductor strategy for the past couple of years has been what’s often called the ‘promote’ agenda. The United States is deploying $39 billion in subsidies through the 2022 CHIPS and Science Act to incentivize new chip factories at home. The strategy has helped galvanize $447 billion in private investment across 25 states, 37 new chip fabs, and expansions at 21 other fabs. The United States is now projected to make 30% of all advanced logic chips by 2032. But the CHIPS and Science Act focuses on advanced chips, not legacy ones. Only a quarter of CHIPS funding ($10 billion) is planned to be spent on legacy-chip production.

Why not pass a Chips Act for legacy chips? California Representative Ro Khanna has called for doing so: “a Chips Act 2.0 and 3.0 to better focus on legacy chips for our cars, refrigerators, and dryers”. Indeed, subsidies may be a key tool to spur additional domestic legacy chip production.

But subsidies alone are unlikely to rise to the challenge. China’s “brute force” economic strategy might render a legacy ‘promote’ agenda stillborn. Beijing’s approach is to eliminate foreign competitors with low prices by flooding international markets with state-sponsored artificially high supply. China could flood the market with cheap chips to deter private Western investment into new chip production despite generous subsidies. The result could be billions of taxpayer dollars spent with insufficient new chip capacity to show for it.

Two recent examples demonstrate how Chinese industrial policy practices can undermine Washington ‘promote’ policy:

- Solar Panels: Two years ago, the Biden administration placed a two-year waiver on tariffs on solar panels manufactured mostly in China but with minor processing in Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam). The administration waived these tariffs (between 50% and 254%) to help meet Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) targets for solar installation. But in 2024 officials became worried that rock-bottom prices of imports (down 50% over the previous year) caused U.S. firms to abandon plans to build new U.S. factories, undermining the separate IRA goal of funding domestic solar manufacturing. Last month the administration let that waiver lapse.

- Critical Minerals: Low global prices are also disrupting administration goals to reshore critical mineral mining with domestic incentives. Lithium prices, for example, dropped by 75% in 2023. Mining investments globally grew at a lower rate last year than in 2022, despite Washington concern about reliance on Chinese minerals.

One Pentagon-funded Idaho mine, the only cobalt mine in the United States, was planned to open last year. It’s instead been mothballed since over low cobalt prices – down by almost two-thirds in two years.The owner of that mine, Australian firm Jervois, told investors in March it would lay off 30% of its senior corporate management over “adverse cobalt market conditions caused by Chinese overproduction and its impact on pricing”.

The warning signs in the legacy chip sector are already flashing. Chinese semiconductors were “20 to more than 30%” cheaper than their international counterparts in 2022 and 2023, according to the Silverado Policy Accelerator.This price advantage will likely only widen with time.

3.3. Don’t Compete with China on Price: The challenge facing U.S. policymakers is that Chinese industrial policy is designed to make it impossible for Western firms to offer prices competitive against Chinese players. The solution is to deny Chinese chips access to Western markets.

The logic is simple yet unfamiliar for some following semiconductor policy. Only if the U.S. market is denied to Chinese chips will those producing for the United States be forced to source chips outside of China, and only then will the construction of scaled chipmaking capacity in third countries become economic.

How It Would Work

Preventing U.S. reliance on Chinese chips would be more complicated than simply raising the tariff on Chinese-made chips imported into the U.S. market. For it to work, Washington would need to target goods that contain Chinese chips, not just the imports of the chips themselves. It also may need allied cooperation.

4.1. Target Chips as Components, not the Chips Themselves: Semiconductors are overwhelmingly an intermediate good, not a final product of the sort Washington typically tariffs or blocks at the border. U.S. policy will have to reflect that complexity.

The Biden administration in May doubled U.S. tariffs on imported Chinese chips from 25% to 50%, citing China’s “rapid capacity expansion that risks driving out investment by market-driven firms”. The original 25% tariff, imposed by the Trump administration in 2018, reduced direct imports of Chinese chips by around 72%, according to the U.S. International Trade Commission. But direct imports represent only a portion – likely a minority portion – of the Chinese-made chips that otherwise enter the United States as components within other devices.

The original 2018 tariffs had no effect on Chinese chips arriving as components of other goods – and neither will the new Biden tariffs, which double the rate of the 2018 tariffs without changing their design. Closing this loophole would require the administration to do just that.

One way of doing so would be to apply a “component tariff”, effectively increasing the import cost of the final good (whatever it is) because it contains a chip or chips made in China. The China Committee called for this in January 2024. Another way would be to deny outright products containing Chinese chips entry into the United States. Both options could work, assuming a component tariff is high enough to overcome any possible Chinese price advantage (e.g., 200% or higher).

Some experts have expressed doubt that it is even possible as a policy matter to target Chinese chips because they are intermediate goods. But this view is erroneous. In fact, various laws allow Washington to tariff or outright exclude from the U.S. market any product made with Chinese semiconductors. (See Section 5).

4.2. Bring the Allies Along: A strategy to prevent U.S. reliance on Chinese chips would have higher odds of success if U.S. allies join, most importantly Europe and Japan. The risk is that without allies, international chip players would continue to design their microelectronics with Chinese chips, leaving the United States out of the best the market has to offer. A more optimistic assessment would be that the U.S. consumer market is so large that unilateral Washington action would be enough to force leading market players to design their products without Chinese chips.

Either way, allied signals are positive. The EU said about legacy chips last April that it was “gathering information on this issue”, and that it would coordinate with the United States to “collect and share non-confidential information” about Chinese “non-market policies and practices”.The bloc’s new duties on Chinese automakers indicate it could be open to similar measures toward chips. Japan has taken fewer concrete steps than Europe, but Tokyo’s Minister for Economy, Trade and Industry Ken Saito told reporters that participants took “great interest” in legacy chips at the first Japan Korea-U.S. Commerce and Industry Ministerial Meeting on 28 June 2024.

Washington’s Toolkit

The United States has multiple policy tools that could be used to prevent U.S. reliance on Chinese made semiconductors. Th following summarizes these tools, in roughly ascending order of magnitude.

5.1. Countervailing Duties: This form of tax can be placed by the Commerce Department on foreign goods that it finds to be subsidised and that the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) finds materially injure a U.S. domestic industry. After an investigation prompted either by a petition from U.S. industry or initiated by Commerce itself, Commerce can impose “CVDs” on the goods in question.

Two challenges, however: First, it can sometimes be difficult to prove that Chinese state subsidies have boosted specific goods. Second, chips imported as components of other goods aren’t a natural fit for CVD investigations, so some policy creativity would likely be required.

5.2. Anti-Dumping Duties: This alternative tax is like its sister duty in how it comes about and who investigates it, but in this case it seeks to counter imports that have been “dumped” at artificially low prices in the U.S. market.

As with CVDs, however, some policy creativity may be required to use anti-dumping duties for chips imported as components of other goods. Further, it can be challenging to establish a baseline “fair” price against which to measure the price of any Chinese goods in the U.S. market. Former senior Commerce official Nazak Nikakhtar noted: “It is nearly impossible to find a surrogate country that has not been adversely affected by the PRC’s predatory pricing. . . . Virtually all benchmark prices in trade cases are now understated and inadequate for measuring [dumping] by the PRC.”

5.3. Section 337: This provision (from the Tariff Act of 1930) allows the U.S. ITC to investigate imported goods for alleged links to intellectual-property theft and a range of other unfair trade practices. Relief can take the form of exclusion orders, cease-and-desist orders, or sequestration of goods.

But the 337’s bureaucratic process might be too burdensome. The ITC is an independent agency not subject to direction by the White House. In 2018, the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, led by ex-ambassador and ex-governor Jon Huntsman, recommended speeding up the ITC’s 337 process.

5.4. Section 5949: With relatively little fanfare, Congress in late 2022 enacted a measure that will curb some Chinese legacy-chip sales in the U.S. market – but only some, and slowly. Via Section 5949 of the annual defence bill, Congress prohibited the U.S. federal government and its contractors from procuring semiconductors for “critical” uses from three Chinese firms (SMIC, YMTC, CXMT), beginning in four years. This provision could be expanded in multiple ways that would block Chinese chips from large swathes of the U.S. market. Policymakers could shorten the phase-in period, blacklist additional companies (beside SMIC, YMTC and CXMT), or force U.S. government contractors not to buy proscribed Chinese chips even for their own private use.

The federal government does not, however, have the authority to force state governments to adopt similar rules. This approach would also allow any company that does not contract with the federal government to purchase Chinese chips.

5.5. ‘ICTS’: The Commerce Department’s “Information and Communications Technology and Services” (ICTS) regime is probably capable of restricting the import of goods containing Chinese made chips. The regime, first outlined in the final days of the Trump administration and embraced by the Biden administration, has broad authorities to restrict transactions (from limits on cross-border data flows to import bans) across theoretically the entire digital economy: critical infrastructure, network infrastructure, data hosting, surveillance and monitoring tech, communications software, and emerging technology.The ICTS office’s current investigation on Chinese ‘Connected Vehicles’, will restrict Chinese-controlled critical components from being used in cars on U.S. roads. The president might similarly be able to use ICTS to restrict the import of products containing Chinese made semiconductors.

Taking on Chinese legacy chips, however, would not fit the ICTS Office neatly:

- ICTS’s policy emphasis thus far has been on technologies key for connectivity applications. In the ongoing ‘Connected Vehicles’ investigation, for example, the office cited its worries about Chinese electric vehicles as centering on software and hardware that enables the car’s connection back to China (e.g., cellular telecommunications systems).Legacy chips do enable connectivity, but the challenge is much broader than that. Mature-node chips enable the entire modern economy.

- It would be daunting task such a new Washington bureaucracy. The office only began fully staffing up in summer 2022, and its first action was taken against a single firm three years after the Biden administration first confirmed it would maintain the authority. ICTS is not likely ready to oversee a mission with such deep implications for the entire microelectronics industry and U.S. trade with China and the rest of the world.

5.6. Section 232: This instrument (from the Trade Expansion Act of 1962) allows any federal department to require a Commerce Department investigation of specified imports that may threaten national security (defined broadly). The President may then impose tariffs or quotas as a remedy. The Trump administration used Section 232 to tariff imports of steel and aluminum in 2018, and it could be a viable approach to legacy chips too.

232’s main drawback is that it does not allow import bans. An obvious workaround would be to apply a component tariff onto Chinese semiconductors so high that it works effectively as a ban (e.g., north of 200%).

5.7. Washington’s Most Powerful Tool – Section 301: The strongest tool for the legacy-chips challenge might be the Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, which gives the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative broad scope investigate “unreasonable”, “discriminatory”, or “unjustifiable” actions that burden U.S. commerce. After an investigation, USTR has sweeping powers to impose remedies as it sees fit, e.g. with tariffs, import bans, or other sanctions. It gives a president notably broad, flexible, and discretionary powers.

301 has become the bipartisan tool of choice to address unfair Chinese trade and industrial practices and to reshore supply chains:

- The Trump administration used 301 as its main instrument for adjusting trade with China. Trump launched a Section 301 investigation into Chinese intellectual-property theft and technology transfer in August 2017, then used its conclusions to apply tariffs in multiple tranches in 2018 and 2019. This is what came to be called the U.S.-China “trade war”. With 301, the Trump administration was able to apply tariffs on Chinese goods to a level unseen (and overwhelmingly unexpected) since before China’s accession to the World Trade Organization.