Summer, Wrapped: The 2025 “State of the Heat”

Earlier this year, FAS sounded the alarm that federal reductions in force, funding pauses and freezes, program elimination, and other actions were stalling or setting back national preparedness for extreme heat – just as summer was kicking into gear. The areas we focused on included:

- Leadership and governance infrastructure

- Key personnel and their expertise

- Data, forecasts, and information availability

- Funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

- Progress towards heat policy goals

With summer 2025 in the rearview mirror, we’re taking a look back to see how federal actions impacted heat preparedness and response on the ground, what’s still changing, and what the road ahead looks like for heat resilience. Consider this your 2025 State of the Heat.

2025 State of the Heat

The State of Summer: How Hot Was It and How Did Communities Cope?

Summer didn’t feel as sweltering this year as it has the past couple of years. That’s objectively true – but only because the summers of 2023 and 2024 were true scorchers.

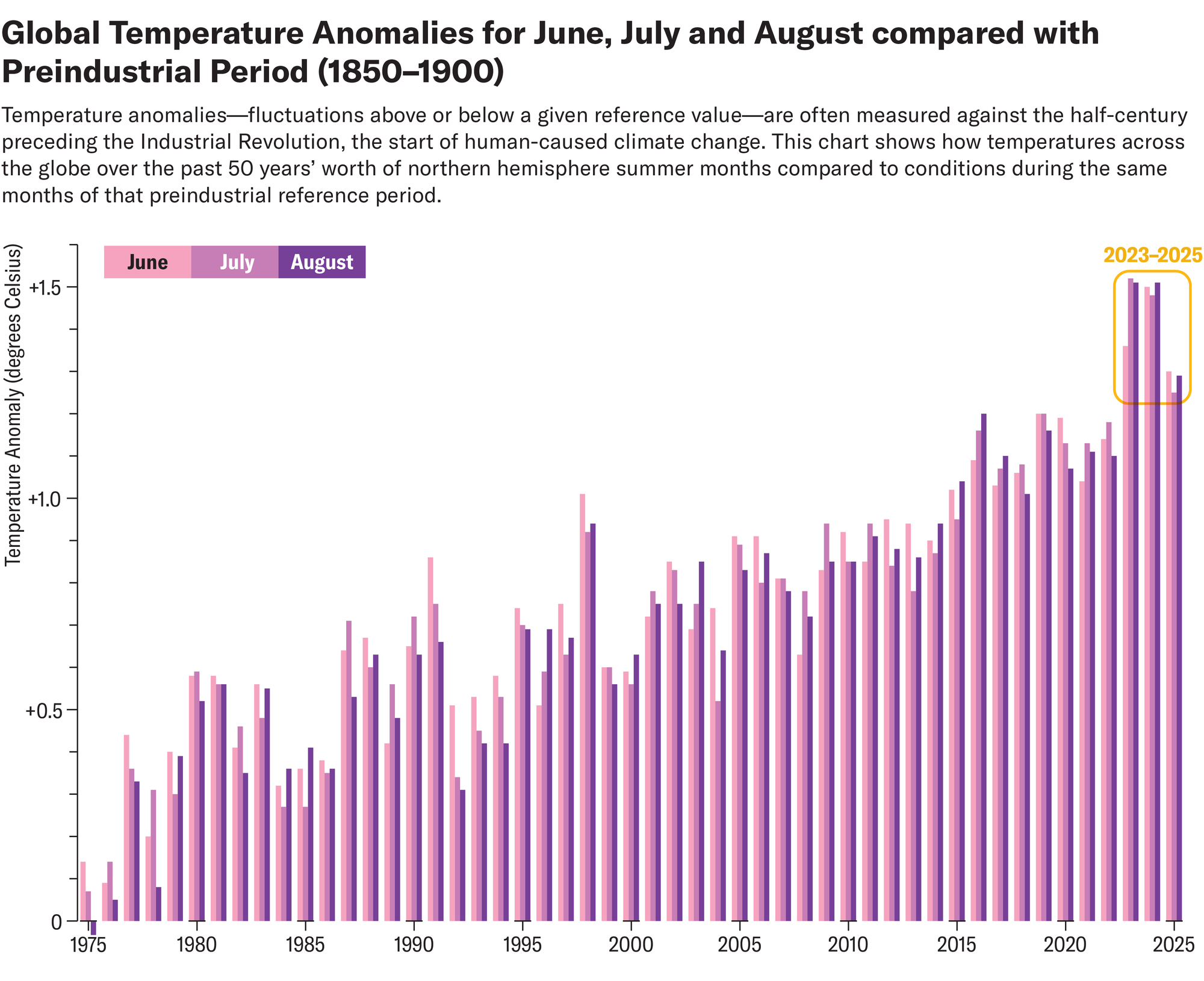

Summer 2025 was cooler than the past two summers, but still the third-hottest on record. Credit: Amanda Montañez in Scientific American; Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service (data)

Summer 2025 was still the third-hottest on record. High temperature records were shattered across the country. Eight states broke their all-time heat records for June, and in July almost the entire country – including Alaska – saw above-average temperatures. Temperature extremes continued into September. Places like the San Francisco Bay Area experienced their hottest temperatures of the year even as the season turned to autumn. In addition, humidity was a particularly potent threat. One hundred twenty million people experienced near-record humidity this summer alongside temperature extremes. Humidity and heat are a deadly combination because sweating is less effective when humidity is high, raising the risk of overheating and experiencing heat-related illness. This heat led to spikes in heat-related illnesses and hospitalizations, longer droughts, road buckling and damage, and even a federal energy emergency in June 2025.

Since January 2025, and continuing over the course of the summer, FAS’s Climate and Health team has been in regular touch with local and state government officials involved in heat preparedness, response, and resilience. These officials generally shared that heat management activities continued successfully in most places throughout the summer despite disruptions to federal funding and programs. Officials emphasized three specific developments that helped enable that continuity:

- Tools like the National Weather Service’s HeatRisk tool remained functional. HeatRisk is a critical tool for subnational governments to understand risks, inform and coordinate partners, and design thresholds for emergency response alerts and actions. Further, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Heat and Health Tracker, which monitors heat-related visits in emergency departments across the country, was brought back online following reversals in CDC reductions in force.

- Some key sources of federal funds, like American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding, remained available. Many local governments – particularly in places without large emergency management programs and Hazard Mitigation Assistance Program (HMGP) funds – have used ARPA funding to support heat response.

- Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) funding was released after considerable advocacy from the external community and members of Congress. This funding is critical to support home energy assistance for cooling bills.

Yet this continuity is fragile:

- The future of the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) and the CDC’s Climate and Health program remains uncertain and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and CDC have faced notable staffing cuts and could face more cuts, jeopardizing the maintenance and existence of tools like HeatRisk and the Heat and Health Tracker.

- Officials are also concerned about their ability to keep robust heat response programs going in a more austere funding landscape. For example, ARPA funding must be spent by December 31, 2026, and many officials are expecting a steep funding cliff that could lead to cuts to heat-related programs. We are already seeing evidence of this in Miami-Dade County, which eliminated its Chief Heat Officer position as a part of an effort to close a $400 million funding gap that emerged in part as ARPA funds were exhausted. Additional cuts to, and restrictions on, federal health preparedness programs and emergency management programs will also impact the staffing capacity of state and local governments. For example, one of the state officials FAS was working with on heat lost their job because of state budget shortfalls, and others have worried about their future job security.

- Finally, while the LIHEAP program is currently intact, and has bipartisan support in Congress, it could be undermined by Executive Branch pocket rescissions and reductions in force.

The State of Federal Heat Governance: What Changed?

The federal heat landscape continues to be highly dynamic. While extreme heat is no longer a stated priority of the federal government, both this Administration and Congress have acknowledged heat’s risks. Against this backdrop, federal agencies are advancing a mixed bag of heat-related policies. For example:

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) continues to pursue a heat rule. This rule, which was initiated under the Biden Administration and is a top priority for worker advocates, was included on the Trump Administration’s Unified Agenda as a regulation in development. However, given comments made at summer hearings on this rule, recent reporting has hypothesized that OSHA may model the rule after Nevada’s newer and weaker “performance-based” standards. This rule includes no “trigger temperatures” above which certain protections are required. An evaluation of the Nevada rule’s effectiveness will be limited by cuts to the staff at the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and less funding for NIOSH’s research.

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommits to research on extreme heat and health. The NIH’s Climate Change and Health (CCH) Initiative was reintroduced as the Program on Health and Extreme Weather (HEW). The HEW Program’s strategic framework eliminates language directly referencing climate change and greenhouse gases and aligns with the Department of Health and Human Services’ broader MAHA strategy. As both houses of Congress rejected cuts to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), there could be funding available through NIEHS for studies on the outcomes of heat exposure, long-term health risks, and preventative measures.

- The Government Accountability Office (GAO) says the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) needs to evaluate its role in addressing extreme heat. A recent GAO report recommended that FEMA improve its benefit-cost analysis for heat, identify heat mitigation projects it might fund, and evaluate its role in heat response – all recommendations from FAS’s 2025 Heat Policy Agenda. FEMA agreed to act partially on the recommendations, citing changes made to HMGP to make extreme heat projects ineligible for standalone funding as a barrier to full action.

- The Department of Energy acknowledges heatwaves as a particular risk. In July, the Department of Energy published a report entitled A Critical Review of the Science of Climate Change. This report has been widely discredited for cherry-picking and misrepresenting scientific studies. However, it is notable that even as the report minimizes the risks of greenhouse gas emissions, it emphasizes the importance of taking action on extreme heat, stating that “heatwaves have important effects on society that must be addressed” and that “inability to afford energy leaves low-income households exposed to weather extremes”. While there are partisan disagreements on how to secure that affordable energy, the report demonstrates that heat risk is an area of consensus between the parties that merits further pursuit.

- The ongoing government shutdown could be used by the Trump Administration to continue their mass firing of federal workers. With the status of Appropriations negotiations stalled, the Office of Management and Budget has asked agencies to prepare contingency plans, and has threatened mass layoffs of furloughed employees. Given that most heat-related activities are not statutorily authorized, this could lead to further cuts to the federal heat workforce. On Friday October 10th, hundreds of workers were laid off across Health and Human Services, including at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics and the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response.

Congressional actions are also shaping what’s possible for nationwide heat preparedness. To start, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) cut funding necessary to mitigate extreme heat’s impacts as well as respond to the negative health consequences of heat. Impacts include:

Beyond OBBBA, Congressional appropriations proposals for Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 represent a mixed bag for federal heat policy. The House and the Senate proposals diverge in key ways, and will need to be rectified. Some of the things we are tracking include:

State of the Future: What Comes Next for Heat Policy

Looking ahead, it is essential that the federal government maintains its role as a data collector, steward, and analyst, supports heat-related research and development, supports social services for the most vulnerable American households facing extreme heat. and continues to make investments in state, local, territorial, and tribal (SLTT) governments and their heat mitigation infrastructure and preparedness capacity. At the same time, SLTT governments are rapidly innovating in heat policy, and will be sites of innovation to watch this next year. Our team is tracking promising signs in three key areas:

- More places are standing up heat governance infrastructure. A growing number of state, regional, and local plans acknowledge extreme heat as a risk; at the same time, more and more communities are developing standalone heat preparedness, response, or action plans (see heatplans.org to learn more, and read our “Framework for a Heat Ready Nation” to learn about progress in the Sunbelt region). New heat plans that launched in 2025 include Lincoln-Lancaster Heat Response Plan, the Low Country Heat Action Plan Toolkit, Orange County, NC’s Heat Action Plan, and King County’s Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy. Many more plans are in the development pipeline. Further, more networks of local governments, including the Ten Across Network and Climate Mayors, are making heat technical assistance a priority.

- More places are expanding their extreme heat protections. Policies that protect people from extreme heat exposure inside of their homes, inside of schools, and at the workplace are also starting to see uptake. LA County set an indoor temperature maximum of 82°F for rental units, creating a legal right to cooling for tenants. Meanwhile, the state of California recently enacted a law that all homes should be able to attain and maintain safe indoor temperatures, without specifying that limit. New Jersey now restricts utilities from shutting off the power due to non-payment from June 15 through August 31; New Jersey is also providing direct utility relief to New Jersey ratepayers. New York State became the first state in the country to regulate extreme heat in schools, setting a maximum temperature threshold of 88F for safe school operations. Finally, in Boston and in New Orleans, ordinances passed that require basic protections from heat, like rest breaks, for all city workers and city contractors. Scaling up these policies that minimize heat overexposure will be critical to be ready for hotter heat seasons to come.

- Regional networks are forming to advance evidence-based public health measures. In light of rollbacks to public health infrastructure at the federal level, two regional networks have formed to coordinate across state public health departments, the West Coast Health Alliance and the Northeast Public Health Collaborative. While the initial focus is on developing evidence-based recommendations on vaccines and combining forces on vaccine procurement for their populations, we will be tracking how these networks address other public health efforts under threat, such as the health risks of extreme heat.

Protecting Americans from extreme heat will require a multiplicity of leadership across the levels of government in the United States and the capacity to connect hundreds of diverse organizations and experts around a shared solution set. To meet this moment, FAS will develop the 2026 State & Local Heat Policy Agenda, a blueprint for polycentric action towards a Heat Ready Nation. The 2026 Heat Policy Agenda will align the growing heat community around a shared set of objectives and equip state and local decision makers with the strategies they can deploy for heat season 2026 and beyond. We are focused on strategies that (1) build government capacity to address the threat of extreme heat and (2) ensure every American can be safe from heat in their homes, in their workplaces, and in their communities.

Over the next couple of months, the FAS team will be documenting the policy levers available at the state and local levels to address extreme heat and crafting model guidance, model executive orders, model legislation, and financing models. Want to be a part of this effort? Reach out to Grace Wickerson at gwickerson@fas.org if you want to contribute by:

- Identifying promising extreme heat policies as well as evidence for their effectiveness.

- Offering your expertise on potential heat-related policy interventions.

- Sharing about heat-related advocacy efforts and potential technical assistance needs.

- Raising your hand as an extreme heat champion inside of state or local government.

FAS is launching the Center for Regulatory Ingenuity (CRI) to build a new, transpartisan vision of government that works – that has the capacity to achieve ambitious goals while adeptly responding to people’s basic needs.

This runs counter to public opinion: 4 in 5 of all Americans, across party lines, want to see the government take stronger climate action.

Cities need to rapidly become compact, efficient, electrified, and nature‑rich urban ecosystems where we take better care of each other and avoid locking in more sprawl and fossil‑fuel dependence.

Hurricanes cause around 24 deaths per storm – but the longer-term consequences kill thousands more. With extreme weather events becoming ever-more common, there is a national and moral imperative to rethink not just who responds to disasters, but for how long and to what end.