Nuclear Transparency and the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

I was reading through the latest Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and wondering what I should pick to critique the Obama administration’s nuclear policy.

After all, there are plenty of issues that deserve to be addressed, including:

– Why NNSA continues to overspend and over-commit and create a spending bow wave in 2021-2026 in excess of the President’s budget in exactly the same time period that excessive Air Force and Navy modernization programs are expected to put the greatest pressure on defense spending?

– Why a smaller and smaller nuclear weapons stockpile with fewer warhead types appears to be getting more and more expensive to maintain?

– Why each warhead life-extension program is getting ever more ambitious and expensive with no apparent end in sight?

– And why a policy of reductions, no new nuclear weapons, no pursuit of new military missions or new capabilities for nuclear weapons, restraint, a pledge to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and the goal of disarmament, instead became a blueprint for nuclear overreach with record funding, across-the-board modernizations, unprecedented warhead modifications, increasing weapons accuracy and effectiveness, reaffirmation of a Triad and non-strategic nuclear weapons, continuation of counterforce strategy, reaffirmation of the importance and salience of nuclear weapons, and an open-ended commitment to retain nuclear weapons further into the future than they have existed so far?

What About The Other Nuclear-Armed States?

Despite the contradictions and flaws of the administration’s nuclear policy, however, imagine if the other nuclear-armed states also published summaries of their nuclear weapons plans. Some do disclose a little, but they could do much more. For others, however, the thought of disclosing any information about the size and composition of their nuclear arsenal seems so alien that it is almost inconceivable.

Yet that is actually one of the reasons why it is necessary to continue to work for greater (or sufficient) transparency in nuclear forces. Some nuclear-armed states believe their security depends on complete or near-compete nuclear secrecy. And, of course, some nuclear information must be protected from disclosure. But the problem with excessive secrecy is that it tends to fuel uncertainty, rumors, suspicion, exaggerations, mistrust, and worst-case assumptions in other nuclear-armed states – reactions that cause them to shape their own nuclear forces and strategies in ways that undermine security for all.

Nuclear-armed states must find a balance between legitimate secrecy and transparency. This can take a long time and it may not necessarily be the same from country to country. The United States also used to keep much more nuclear information secret and there are many institutions that will always resist public access. But maximum responsible disclosure, it turns out, is not only necessary for a healthy public debate about nuclear policy, it is also necessary to communicate to allies and adversaries what that policy is about – and, equally important, to dispel rumors and misunderstandings about what the policy is not.

Nuclear transparency is not just about pleasing the arms controllers – it is important for national security.

So here are some thoughts about what other nuclear-armed states should (or could) disclose about their nuclear arsenals – not to disclose everything but to improve communication about the role of nuclear weapons and avoid misunderstandings and counterproductive surprises:

Russia should publish:

Russia should publish:

– Full New START aggregate data numbers (these numbers are already shared with the United States, that publishes its own numbers)

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Number of history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has made statements about percentage reductions since 1991 but not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of which nuclear forces are nuclear-capable (has made some statements about strategic forces but not shorter-range forces)

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces (has made occasional statements about modernizations but no detailed plan)

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

China should publish:

China should publish:

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (stated in 2004 that it possessed the smallest arsenal of the nuclear weapon states but has not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of its nuclear-capable forces

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

France should publish:

France should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has disclosed the size of its nuclear stockpile in 2008 and 2015 (300 weapons), but not the history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has declared dismantlement of some types but not history)

(France has disclosed its overall force structure and some nuclear budget information is published each year.)

Britain should publish:

Britain should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has declared some approximate historic numbers, declared the approximate size in 2010 (no more than 225), and has declared plan for mid-2020s (no more than 180), but has not disclosed history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has announced dismantlement of systems but not numbers or history)

(Britain has published information about the size of its nuclear force structure and part of its nuclear budget.)

Pakistan should publish:

Pakistan should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

India should publish:

India should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

Israel should publish:

Israel should publish:

…or should it? Unlike other nuclear-armed states, Israel has not publicly confirmed it has a nuclear arsenal and has said it will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Some argue Israel should not confirm or declare anything because of fear it would trigger nuclear arms programs in other Middle Eastern countries.

On the other hand, the existence of the Israeli nuclear arsenal is well known to other countries as has been documented by declassified government documents in the United States. Official confirmation would be politically sensitive but not in itself change national security in the region. Moreover, the secrecy fuels speculations, exaggerations, accusations, and worst-case planning. And it is hard to see how the future of nuclear weapons in the Middle East can be addressed and resolved without some degree of official disclosure.

North Korea should publish:

North Korea should publish:

Well, obviously this nuclear-armed state is a little different (to put it mildly) because its blustering nuclear threats and statements – and the nature of its leadership itself – make it difficult to trust any official information. Perhaps this is a case where it would be more valuable to hear more about what foreign intelligence agencies know about North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. Yet official disclosure could potentially serve an important role as part of a future de-tension agreement with North Korea.

Additional information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces with links to more information about individual nuclear-armed states.

“Nuclear Weapons Base Visits: Accident and Incident Exercises as Confidence-Building Measures,” briefing to Workshop on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Practice, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 27-28 March 2014.

“Nuclear Warhead Stockpiles and Transparency” (with Robert Norris), in Global Fissile Material Report 2013, International Panel on Fissile Materials, October 2013, pp. 50-58.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows Russian Increases and US Decreases

By Hans M. Kristensen

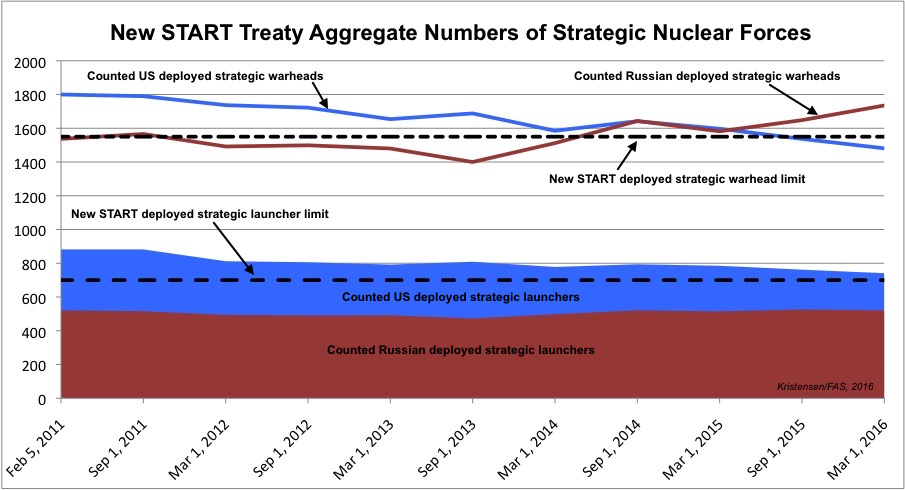

[Updated April 3, 2016] Russia continues to increase the number of strategic warheads it deploys on its ballistic missiles counted under the New START Treaty, according to the latest aggregate data released by the US State Department.

The data shows that Russia now has almost 200 strategic warheads more deployed than when the New START treaty entered into force in 2011. Compared with the previous count in September 2015, Russia added 87 warheads, and will have to offload 185 warheads before the treaty enters into effect in 2018.

The United States, in contrast, has continued to decrease its deployed warheads and the data shows that the United States currently is counted with 1,481 deployed strategic warheads – 69 warheads below the treaty limit.

The Russian increase is probably mainly caused by the addition of the third Borei-class ballistic missile submarine to the fleet. Other fluctuations in forces affect the count as well. But Russia is nonetheless expected to reach the treaty limit by 2018.

The Russian increase of aggregate warhead numbers is not because of a “build-up” of its strategic forces, as the Washington Times recently reported, or because Russia is “doubling their warhead output,” as an unnamed US official told the paper. Instead, the temporary increase in counted warheads is caused by fluctuations is the force level caused by Russia’s modernization program that is retiring Soviet-era weapons and replacing some of them with new types.

Strategic Launchers

The aggregate data also shows that Russia is now counted as deploying exactly the same number of strategic launchers as when the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011: 521.

But Russia has far fewer deployed strategic launchers than the United States (a difference of 220 launchers) and has been well below the treaty limit since before the treaty was signed. The United States still has to dismantle 41 launchers to reach the treaty limit of 700 deployed strategic launchers.

The United States is counted as having 21 launchers fewer than in September 2015. That reduction involves emptying of some of the ICBM silos (they plan to empty 50) and denuclearizing a few excess B-52 bombers. The navy has also started reducing launchers on each Trident submarine from 24 missile tubes to 20 tubes. Overall, the United States has reduced its strategic launchers by 141 since 2011, until now mainly by eliminating so-called “phantom” launchers – that is, aircraft that were not actually used for nuclear missions anymore but had equipment onboard that made them accountable.

Again, the United States had many more launchers than Russia when the treaty was signed so it has to reduce more than Russia.

New START Counts Only Fraction of Arsenals

Overall, the New START numbers only count a fraction of the total nuclear warheads that Russia and the United States have in their arsenals. The treaty does not count weapons at bomber bases or central storage, additional ICBM and submarine warheads in storage, or non-strategic nuclear warheads.

Our latest count is that Russia has about 7,300 warheads, of which nearly 4,500 are for strategic and tactical forces. The United States has about 6,970 warheads, of which 4,670 are for strategic and tactical forces.

See here for our latest estimates: https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/

See analysis of previous New START data: https://fas.org/blogs/security/2015/10/newstart2015-2/

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

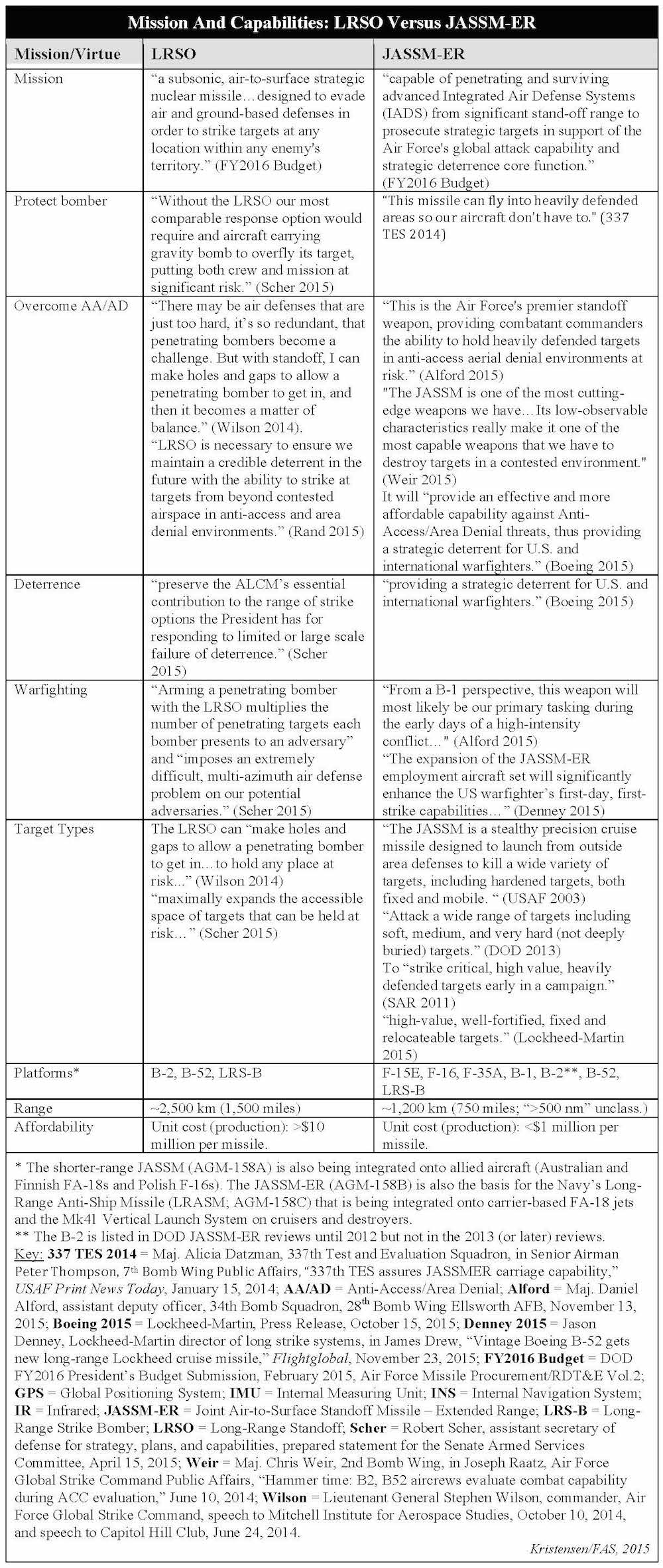

Questions About The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

During a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing on March 16, Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), the ranking member of the committee, said that U.S. Strategic Command had failed to convince her that the United States needs to develop a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile; the LRSO (Long-Range Standoff missile).

“I recently met with Admiral Haney, the head of Strategic Command regarding the new nuclear cruise missile and its refurbished warhead. I came away unconvinced of the need for this weapon. The so-called improvements to this weapon seemed to be designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war. I find that a shocking concept. I think this is really unthinkable, especially when we hold conventional weapons superiority, which can meet adversaries’ efforts to escalate a conflict.”

Feinstein made her statement only a few hours after Air Force Secretary Deborah James had told the House Armed Services Committee on the other side of the Capitol that the LRSO will be capable of “destroying otherwise inaccessible targets in any zone of conflict.”

Lets ignore for a moment that the justification used for most nuclear and advanced conventional weapons also is to destroy otherwise inaccessible targets, what are actually the unique LRSO targets? In theory the missile could be used against anything that is within range but that is not good enough to justify spending $20-$30 billion.

So Air Force officials have portrayed the LRSO as a unique weapon that can get in where nothing else can. The mission they describe sounds very much like the role tactical nuclear weapons played during the Cold War: “I can make holes and gaps” in air defenses, then Air Force Global Strike Command commander Lieutenant General Stephen Wilson explained in 2014, “to allow a penetrating bomber to get in.”

And last week, shortly before Admiral Haney failed to convince Sen. Feinstein, EUCOM commander General Philip Breedlove added more details about what they want to use the nuclear LRSO to blow up:

“One of the biggest keys to being able to break anti-access area denial [A2AD] is the ability to penetrate the air defenses so that we can get close to not only destroy the air defenses but to destroy the coastal defense cruise missiles and the land attack missiles which are the three elements of an A2AD environment. One of the primary and very important tools to busting that A2AD environment is a fifth generation ability to penetrate. In the LRSB you will have a platform and weapons that can penetrate.” (Emphasis added.)

Those A2/AD targets would include Russian S-400 air-defense, Russian Bastion-P coastal defense, and Chinese DF-10A land-attack missile launchers (see images).

Judging from Sen. Feinstein’s conclusion that the LRSO seems “designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war,” Admiral Haney probably described similar LRSO targets as Lt. Gen. Wilson and Gen. Breedlove.

After hearing these “shocking” descriptions of the LRSO’s warfighting mission, Senator Feinstein asked NNSA’s Gen. Klotz if he could do a better job in persuading her about the need for the new nuclear cruise missile:

Sen. Feinstein: “So maybe you can succeed where Admiral Haney did not. Let me ask you this question: Why do we need a new nuclear cruise missile?”

Gen. Klotz: “My sense at the time, and it still is the case, is that the existing cruise missile, the air-launched cruise missile, is getting rather long in the tooth with the issues that are associated with an aging weapon system. It was first deployed in 1982. And therefore it is well past it service life. In the meantime, as you know from your work on the intelligence committee, there has been an increase in the sophistication and capabilities as well as proliferation of sophisticated air- and missile-defenses around the world. Therefore the ability of the cruise missile to pose the deterrent capability, the capability that is necessary to deter, is under question. Therefore, just based on the ageing and the changing nature of the threat we need to replace a system we’ve had, again, since the early 1980s with an updated variant….I guess I didn’t convince you any more than the Admiral did.”

Sen. Feinstein: “No you didn’t convince me. Because this just ratchets up warfare and ratchets up deaths. Even if you go to a low kiloton of six or seven it is a huge weapon. And I thought there was a certain morality that we should have with respect to these weapons. If it’s really mutual deterrence, I don’t see how this does anything other…it’s like the drone. The drone has been invented. It’s been armed. Now every county wants one. So they get more and more sophisticated. To do this with nuclear weapons, I think, is awful.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

Senator Feinstein has raised some important questions about the scope of nuclear strategy. How useful should nuclear weapons be and for what type of scenarios?

Proponents of the LRSO do not seem to question (or discuss) the implications of developing a nuclear cruise missile intended for shooting holes in air- and coastal-defense systems. Their mindset seems to be that anything that can be used to “bust the A2AD environment” – even a nuclear weapon – must be good for deterrence and therefore also for security and stability.

While a decision to authorize use of nuclear weapons would be difficult for any president, the planning for the potential use does not seem to be nearly as constrained. Indeed, the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission that defense officials describe raises some serious questions about how soon in a conflict nuclear weapons might be used.

Since A2AD systems would likely be some of the first targets to be attacked in a war, a nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission appears to move nuclear use to the forefront of a conflict instead of keeping nuclear weapons in the background as a last resort where they belong.

And the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission sounds eerily similar to the outrageous threats that Russian officials have made over the past several years to use nuclear weapons against NATO missile defense systems – threats that NATO and US officials have condemned. Of course, they don’t brandish the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission as a threat – they call it deterrence and reassurance.

Nor do LRSO proponents seem to ask questions about redundancy and which types of weapons are most useful or needed for the anti-A2AD mission. The A2AD targets that the military officials describe are not “otherwise inaccessible targets,” as suggested by Secretary James, but are already being held at risk with conventional cruise missiles such as the Air Force’s JASSM-ER (extended range Joint Air-to-Surface Missile) and the navy’s Tactical Tomahawk, as well as with other nuclear weapons. The Air Force doesn’t have endless resources but must prioritize weapon systems.

Gen. Klotz defended the LRSO as if it were a choice between having a nuclear deterrent or not. But, of course, even without a nuclear LRSO, US stealth bombers will still be armed with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb and the US nuclear deterrent will still include land- and sea-based long-range ballistic missiles as well as F-35A stealthy fighter-bombers also armed with the B61-12.

The White House needs to rein in the nuclear warfighters and strategists to ensure that US nuclear strategy and modernization plans are better in tune with US policy to “reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks” and enable non-nuclear weapons to “take on a greater share of the deterrence burden.” Canceling the nuclear LRSO would be a good start.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

FAS Nuclear Notebook Published: US Nuclear Forces, 2016

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

Our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook has been published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. This issue provides a new overview of the status and plans for US nuclear forces and updates our estimate of the number of nuclear weapons in the stockpile and deployed force.

The next issue scheduled for May will be on Russian nuclear forces.

For an update on worldwide nuclear weapons inventories, see our World Nuclear Forces web page.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

New B-21 Bomber or B-2 Mod 1?

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

The US Air Force has published the first official image of the next-generation bomber, formerly known as LRS-B (Long Range Strike Bomber). Air Force Secretary Deborah Lee James revealed the image during her talk to the 2016 Air Warfare Symposium and gave it its official designation: B-21.

The “21” refers to the 21st Century and is intended to signal cutting-edge technology and capability. (Last time the Pentagon named a major defense program after the 21st Century was the SSN-21, the Navy’s Seawolf-class attack submarine. That program was canceled after only three boats.)

But just how different the B-21 is remains to be seen. The B-21 image shows the new bomber is not a significantly new design but looks more like an upgrade of the B-2. The main focus may have been to improve stealth and sensors. The Air Force has promised to disclose more details in March. They’ll certainly have to, if they want all the money they’re asking for it.

Preliminary Design Comparison

A preliminary comparison of the B-21 and B-2 bomber images suggests a very similar overall design, perhaps a little smaller, but with some significant modifications.

The most apparent difference is that the B-21 has a clean diamond-shaped center body section in contrast to the B-2’s more jagged rear center wing outline. The indents in the B-2’s rear center wing were created by the engine exhausts, a design feature that appears to be absent from the B-21. Engine exhaust is an important source of detectable heat. It is unknown if the engine exhausts have been moved below the body, integrated better into the edge of the wing, or omitted from the drawing because it is still a secret.

The elimination of the two engine exhaust wing-indents appears to have resulted in longer outer wing sections. And the wings on the B-21 appear a little more backswept than the wings on the B-2 resulting in a pointier aircraft nose, although that could be an optical illusion from the the quality of the images.

Another difference is that the air-intakes of the two engines have been extended forward and the edges angled, presumably to further reduce the aircraft’s radar signature.

Whatever else is “hidden under the hood,” the Air Force says that the design “allowed for the use of mature systems and existing technology while still providing desired capability” but with “an open architecture allowing integration of new technology and timely response to future threats across the full range of military operations.” (Emphasis added.)

It Doesn’t Have A Name

The new bomber has a designation (B-21) but not yet a name. The B-2 is called the Spirit. The B-52 is called the Stratofortress. The B-1 is called the Lancer. So Secretary James invited air force personnel to come up with a name. There are already many suggestions – some serious, some gung ho, others highly critical:

Defense News has a voting page and there is a growing list of suggestions in the comments to Secretary James’ announcement. Just to mention a few:

Spirit II, Deliverance, Thunderbolt, Sand Melter, Nightwing, Stormbringer, Flying W, Batwing, The Obama, Lemay, Regurgitating Pigeon, Flying Money-Pit, 2-Bad (the Cold War never really ended), Boondoggle, Budgetbuster, or Another Flying Turd from Northrop Hunk Of Overpriced Under-Performing Long Delayed Useless Waste of Taxpayers Money.

Or how about Resurrection? The Air Force didn’t get its 132 B-2 bombers, only 21 because they were too expensive. So now the Air Force tries again with what looks like a modified B-2: the B-21.

Looming Costs

The Air Force says each B-21 will “only” cost $564 million (in FY2016 money) plus $23.5 billion for overall program development, or a total of nearly $80 billion for 100 bombers.

The Air Force also claims the average procurement cost of each B-21 will be approximately a third of what the B-2 cost was.

These cost projections are already being met with considerable skepticism. Based on the Air Force’s own projections, according to a recent study, the cost of major Air Force aircraft programs “is projected to peak in FY2023 at nearly twice the FY2015 level of funding, adjusting for inflation, and is a driving factor behind the overall defense modernization bow wave.”

Senator John McCain, the chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee that has to approve B-21 funding, has already voiced opposition to key provisions in the current B-21 contract. This should make for some interesting hearings on the Hill later this spring.

And new defense programs historically tend to go 20-30 percent over budget, which would put further pressure on the Air Force’s budget.

If so, the total cost for developing and producing 100 B-21 bombers might reach $96 billion to $104 billion. Oh, and don’t forget to add the costs of integrating the new B61-12 nuclear guided bomb and new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO) on the B-21 as well.

I just wonder what the Air Force’s fallback plan is. Delay? Fewer bombers? Less advanced design? Fewer fighters? Fewer satellites? Fewer tankers? No LRSO? Fewer ICBMs? Absent a major infusion of additional money into the defense budget, the Air Force’s current modernization plan seems unsustainable.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

PBS Newshour Takes On The Holy Nuclear Triad

Although they forgot to credit, PBS Newshour used FAS updated estimates for world nuclear stockpiles. The full list is here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

It has almost become dogma: the United States needs to keep a Triad of strategic nuclear forces. Therefore, expensive modernization of every leg is necessary plus a fourth leg of non-strategic fighter-jets. Oh, and don’t forget nuclear command and control systems such as terminals and satellites.

Without that, deterrence of potential adversaries will fail and they will use nuclear weapons, allies will loose faith and develop their own, and potential adversaries will win a nuclear war. That’s the picture being painted by a vast and influential community of nuclear warfighters, planners, strategists, defense contractors, and former nuclear officials. They’re having a field day now because of Russia’s misbehavior in Eastern Europe and China’s military modernization.

In reality the situation is less clear-cut: the choice is not between modernization or no modernization, nuclear weapons or no nuclear weapons, but how much and of what kind is necessary for which scenarios. When have strategists and warfighters not been able to come up with yet another worst-case scenario to justify status quo or even better nuclear weapons?

The reality is that if we don’t think carefully about missions and priorities and overspend on nuclear weapons, maintenance and modernization of conventional forces – the weapons that are actually useable – will suffer. And that’s bad defense planning.

The PBS Newshour program does a good job (in the limited time it had) in taking on the Holy Triad, bringing in people from both sides of the isle. This was the third program in a series about the U.S. nuclear arsenal and mission. The others two episodes were: How many ballistic missile submarines does the U.S. really need? from July 2015, and America’s nuclear bomb gets a makeover from November 2015.

Watch them, learn, and think…

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Pentagon Portrays Nuclear Modernization As Response to Russia

By Hans M. Kristensen

The final defense budget of the Obama administration effectively crowns this administration as the nuclear modernization leader of post-Cold War U.S. presidencies.

While official statements so far have mainly justified the massive nuclear modernization as simply extending the service-life of existing capabilities, the Pentagon now explicitly paints the nuclear modernization as a direct response to Russia:

PB 2017 Adjusts to Strategic Change. Today’s security environment is dramatically different from the one the department has been engaged with for the last 25 years, and it requires new ways of thinking and new ways of acting. This security environment is driving the focus of the Defense Department’s planning and budgeting.

[…]

Russia. The budget enables the department to take a strong, balanced approach to respond to Russia’s aggression in Eastern Europe.

- We are countering Russia’s aggressive policies through investments in a broad range of capabilities. The FY 2017 budget request will allow us to modify and expand air defense systems, develop new unmanned systems, design a new long-range bomber and a new long-range stand-off cruise missile, and modernize our nuclear arsenal.

[…]

The cost for the new long-range bomber (LRS-B) is still secret but will likely total over 100 billion. But the new budget contains out-year numbers for the new cruise missile (LRSO) that show a significant increase in funding in 2018 and 2019. More than $4.6 billion is projected through 2021:

The total life-cycle cost of the new cruise missile may be as high as $30 billion. Excessive and expensive nuclear modernization programs in the budget threaten funding of more important non-nuclear defense programs.

The Pentagon and defense contractors say the LRSO is needed to replace the existing aging air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) to shoot holes in enemy air defenses, fight limited nuclear wars, and because Russia has nuclear cruise missiles. The claims recycle Cold War justifications and ignore the effectiveness of other military forces in deterring and defeating potential adversaries.

Last year Defense Secretary Carter promised NATO’s response to Russia would not use the “Cold War playbook” of large American forces stationed in Europe.

But other pages in the Cold War playbook – including those relating to nuclear forces – appear to have been studied well with growing nuclear bomber integration in Europe, revival of escalation scenarios and contingency planning, development of a new bomber and a cruise missiles, and deployment of guided nuclear bombs on stealth fighters in Europe within the next decade.

Russia – after having triggered a revival of NATO with its invasion of Ukraine, large-scale exercises, and overt nuclear threats – is likely to respond to NATO’s military posturing by beefing up its own operations. Russian officials quickly reacted to NATO’s latest announcement to boost military forces in Eastern Europe by pledging to improve its conventional and nuclear forces further.

It is obvious what’s happening here. The issue is not who’s to blame or who started it. The challenge is how to prevent that the actions each side take in what they consider justified responses to the other side’s aggression do not escalate further into a new round of Cold War.

The explicit inclusion of nuclear forces in the tit-for-tat posturing is another worrisome sign that the escalation has already started.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

RAND Report Questions Nuclear Role In Defending Baltic States

By Hans M. Kristensen

The RAND Corporation has published an interesting new report on how NATO would defend the Baltic States against a Russian attack.

Without spending much time explaining why Russia would launch a military attack against the Baltic States in the first place – the report simply declares “the next [after Ukraine] most likely targets for an attempted Russian coercion are the Baltic Republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania” – the report contains some surprising (to some) observations about the limitations of nuclear weapons in the real world (by that I mean not in the heads of strategists and theorists).

The central nuclear observation of the report is that NATO nuclear forces do not have much credibility in protecting the Baltic States against a Russian attack.

That conclusion is, to say the least, interesting given the extent to which some analysts and former/current officials have been arguing that NATO/US need to have more/better limited regional nuclear options to counter Russia in Europe.

The report is very timely because the NATO Summit in Warsaw in six months will decide on additional responses to Russian aggression. Unfortunately, some of the decisions might increase the role or readiness of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Limits of Nuclear Weapons

The RAND report contains important conclusions about the role that nuclear weapons could play in deterring and repelling a Russian attack on the Baltic States. Here are the relevant nuclear-related excerpts from the report:

“Any counteroffensive would also be fraught with severe escalatory risks. If the Crimea experience can be taken as a precedent, Moscow could move rapidly to formally annex the occupied territories to Russia. NATO clearly would not recognize the legitimacy of such a gambit, but from Russia’s perspective it would at least nominally bring them under Moscow’s nuclear umbrella. By turning a NATO counterattack aimed at liberating the Baltic republics into an “invasion” of “Russia,” Moscow could generate unpredictable but clearly dangerous escalatory dynamics.”

[…]

“The second option would be for NATO to turn the escalatory tables, taking a page from its Cold War doctrine of “massive retaliation,” and threaten Moscow with a nuclear response if it did not withdraw from the territory it had occupied. This option was a core element of the Alliance’s strategy against the Warsaw Pact for the duration of the latter’s existence and could certainly be called on once again in these circumstances.

The deterrent impact of such a threat draws power from the implicit risk of igniting an escalatory spiral that swiftly reaches the level of nuclear exchanges between the Russian and U.S. homelands. Unfortunately, once deterrence has failed—which would clearly be the case once Russia had crossed the Rubicon of attacking NATO member states—that same risk would tend to greatly undermine its credibility, since it may seem highly unlikely to Moscow that the United States would be willing to exchange New York for Riga. Coupled with the general direction of U.S. defense policy, which has been to de-emphasize the value of nuclear weapons, and the likely unwillingness of NATO’s European members, especially the Baltic states themselves, to see their continent or countries turned into a nuclear battlefield, this lack of believability makes this alternative both unlikely and unpalatable.”

[…]

“We did not portray nuclear use in any of our games, although we did explore the effects of various kinds of constraints on each side’s operations intended to represent limitations that might be imposed by national or alliance political leaderships anxious to avoid setting off escalatory spirals.”

[…]

“Other options have been discussed to enhance NATO’s deterrent posture without significantly increasing its conventional force deployments. For example, NATO could rely on an increased availability and reliance on tactical and theater nuclear weapons. However, as recollections of the endless Cold War debates about the viability of nuclear threats to deter conventional aggression by a power that itself has a plethora of nuclear arms should remind us, this approach has issues with credibility similar to those already discussed with regard to the massive retaliation option in response to a Russian attack.”

Even So…

Not surprisingly, some analysts and former officials (even some current officials) are busy arguing – even lobbying for – that NATO and the United States need more tailored nuclear capabilities to be able to deter and, if necessary, respond to precisely the type of scenario the RAND study had doubts about.

There’s no doubt that Vladimir Putin’s escapades are creating security concerns in the Baltic States and NATO. The invasion of Ukraine, increased military operations, direct nuclear threats, and a host of less visible activities effectively have killed the trust between Russia and NATO. Relations have deteriorated to an officially adversarial and counter-responsive climate. It is in this atmosphere that analysts and nuclear hardliners are trying to understand how it affects nuclear weapons policy.

Hardliners are convinced that Russia has increased reliance on nuclear weapons in a whole new way that envisions first-use of nuclear weapons. One former official who helped shape the George W. Bush administration’s nuclear policy recently warned that Russia “seeks to prevent any significant collective Western defensive opposition by threatening limited nuclear first-use in response,” and that the Russian threat to use nuclear weapons first “is a new reality more dangerous than the Cold War.” (Emphasis added.)

That is probably a bit over the top. As for the claim that Russia is “pursuing” low-yield nuclear weapons to “make its first-use threat credible,” that rumor dates back to a number of articles in Russian media in the 1990s. Those rumors followed reports in the United States in 1993 that the Clinton administration was considering low-yield nuclear weapons – even “micro-nukes.” The Bush administration in the 2000s pursued pre-emptive nuclear strike scenarios and advanced-concept nuclear weapons for tailored use. Although Congress rejected these plans, some of the ideas seem to have influenced Russian nuclear thinking.

The US Air Force plans to deploy the new F-35A with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb in Europe from 2024. The B61-12 will be more accurate than current bombs and appears to have earth-penetration capability.

Now we’re again hearing proposals from some analysts that the United States should develop a “measured response” strategy that includes “discriminate nuclear options at all rungs of the nuclear escalation ladder” to ensure that “there are no gaps in U.S. nuclear response options that would prevent it from retaliating proportionately to any employment of a nuclear weapon against the United States and its allies.” This would require “low-yield, accurate, special-effects options that can respond proportionately at the lower end of the nuclear continuum.”

It is easy to get spooked by public statements and led astray by entangled logic and worst-case scenarios that spin into claims and recommendations that may be based on misunderstood or exaggerated information. It would be more interesting and beneficial to the public debate to hear what the U.S. Intelligence Community has concluded Russia has developed and what is new and different in Russian nuclear strategy today.

A Better Strategy

Fortunately, Russia’s general military capabilities – although important – are so limited that the RAND study concludes that for NATO to be able to counter a Russian attack on the Baltic States “does not appear to require a Herculean effort.”

The LRSO, not yet developed, could pay for 10 years of real-world protection of the Baltic States.

Instead, the report concludes that a NATO force of about seven brigades, including three heavy armored brigades – adequately supported by airpower, land-based fires, and other enablers on the ground and ready to fight at the onset of hostilities – might prevent such an outcome.

NATO has already created a conventional Spearhead Force brigade of about 5,000 troops. Seven brigades of that size would include about 35,000 troops.

Creating and maintaining such a force, RAND estimates, might cost on the order of $2.7 billion per year.

Put in perspective, the $30 billion the Pentagon plans to spend on a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO) that is not needed could buy NATO more a decade worth of real protection of the Baltic States.

Guess what would help the Baltic States the most.

Background: Rand Report

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Declassified: US Nuclear Weapons At Sea

ASROC nuclear test, 1962

Remember during the Cold War when US Navy warships and attack submarines sailed the World’s oceans bristling with nuclear weapons and routinely violated non-nuclear countries’ bans against nuclear weapons on their territories in peacetime?

The weapons were onboard ballistic missile submarines, attack submarines, aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers, destroyers, frigates and supply ships. The weapons were brought along on naval exercises, spy missions, freedom of navigation demonstrations and port visits.

Sometimes the vessels they were on collided, ran aground, caught fire, or sank.

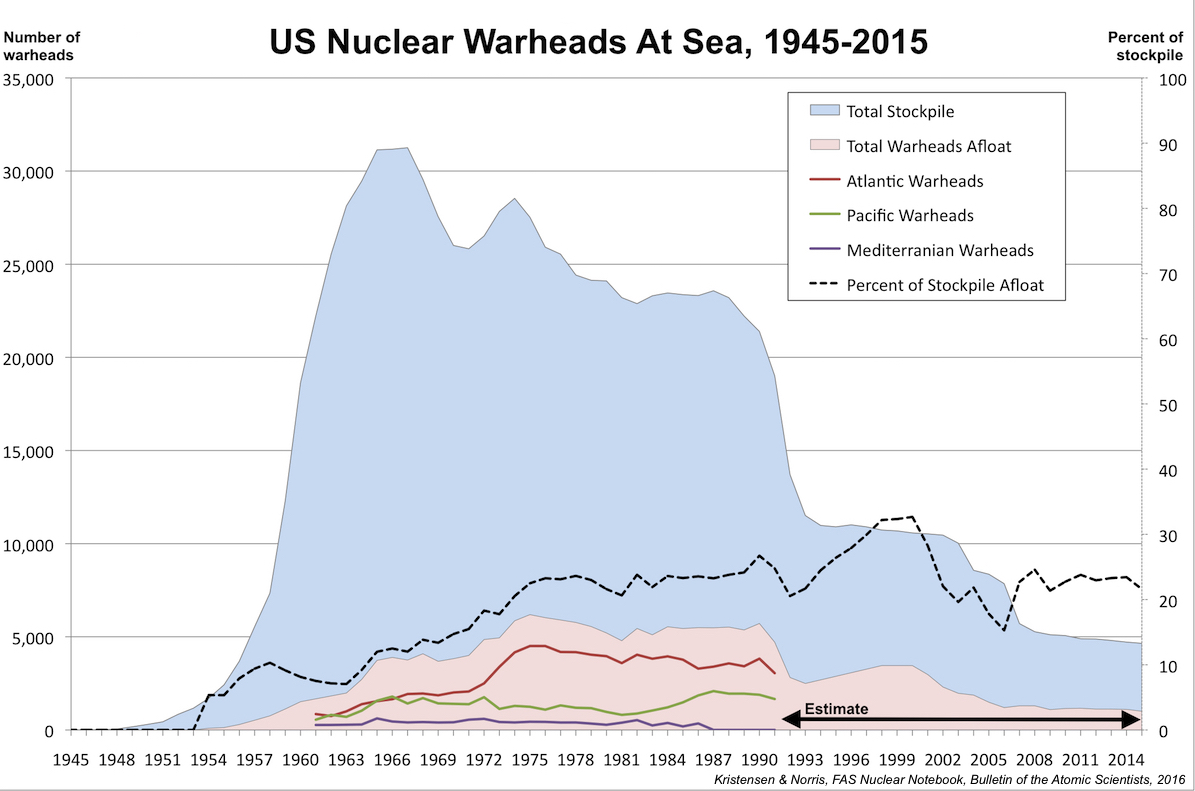

Not many remember today. But now the Pentagon has declassified how many nuclear weapons they actually deployed in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean. In our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists we review this unique new set of de-classified Cold War nuclear history.

The Numbers

The declassified documents show that the United States during much of the 1970s and the 1980s deployed about a quarter of its entire nuclear weapons stockpile at sea. The all-time high was in 1975 when 6,191 weapons were afloat, but even in 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, there were 5,716 weapons at sea. That’s more nuclear weapons than the size of the entire US nuclear stockpile today.

The declassified data provides detailed breakdowns for weapons in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Mediterranean for the 30-year period between 1961 and 1991. Prior to 1961 only totals are provided. Except for three years (1962, 1965 and 1966), most weapons were always deployed in the Atlantic, a reflection of the focus on defending NATO against the Soviet Union. When adding the weapons in the Mediterranean, the Euro-centric nature of the US nuclear posture during the Cold War becomes even more striking. The number of weapons deployed in the Pacific peaked much later, in 1987, at 2,085 weapons.

The declassified numbers end in 1991 with the offloading of non-strategic naval nuclear weapons from US Navy vessels. After that only strategic missile submarines (SSBNs) have continued to deploy with nuclear weapons onboard. Those numbers are still secret.

In the table above we have incorporated our estimates for the number of nuclear warhead deployed on US ballistic missile submarines since 1991. Those estimates show that afloat weapons increased during the 1990s as more Ohio-class SSBNs entered the fleet.

Because the total stockpile decreased significantly in the early 1990s, the percentage of it that was deployed at sea grew until it reached an all-time high of nearly 33 percent in 2000. Retirement of four SSBNs, changes to strategic war plans, and the effect of arms control agreements have since reduced the number of nuclear weapons deployed at sea to just over 1,000 in 2015. That corresponds to nearly 22 percent of the stockpile deployed at sea.

The just over 1,000 afloat warheads today may be less than during the Cold War, but it is roughly equivalent to the nuclear weapons stockpiles of Britain, China, France, India, Israel, Pakistan and North Korea combined.

Mediterranean Mystery

The declassification documents do not explain how the numbers are broken down. The “Atlantic,” “Pacific,” and “Mediterranean” regions are not the only areas where the U.S. Navy sent nuclear-armed warships. Afloat weapons in the Indian and Arctic oceans, for example, are not listed even though nuclear-armed warships sailed in both oceans. Similarly, the declassified documents show the number of afloat weapons in the Mediterranean suddenly dropping to zero in 1987, even though the U.S. Navy continued so deploy nuclear-armed vessels into the Mediterranean Sea.

During the naval deployments in support of Operation Desert Storm against Iraq in early 1991, for example, the aircraft carrier USS America (CV-66) deployed with its nuclear weapons division (W Division) and B61 nuclear strike bombs and B57 nuclear depth bombs. The W Division was still onboard when America deployed to Northern Europe and the Mediterranean in 1992 but had been disbanded by the time it deployed to the Mediterranean in 1993.

B61 and B57 nuclear weapons are displayed on board the USS America (CV-66) during its deployment to Operation Desert Storm in 1991. The nuclear division was also onboard in 1992 but gone in 1993.

As ships offloaded their weapons, the on-board nuclear divisions gradually were disbanded in anticipation of the upcoming denuclearization of the surface fleet. One of the last carriers to deploy with a W Division was the USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67), which upon its return to the United States from a Mediterranean deployment in 1992-1993 ceremoniously photographed the W crew with the sign: “USS John F. Kennedy, CV 67, last W-Division, 17 Feb. 93.” The following year, the Clinton administration publicly announced that all carriers and surface ships would be denuclearized.

The last nuclear weapons division on the USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) is disbanded in February 1993. The following year the entire surface fleet was denuclearized.

Since nuclear weapons clearly deployed to the Mediterranean Sea after the declassified documents showing zero afloat nuclear weapons in the area, perhaps the three categories “Atlantic,” “Pacific,” and “Mediterranean” refer to overall military organization: “Atlantic” might be weapons under the command of the Atlantic Fleet (LANTFLT); “Pacific” might refer to the Pacific Fleet (PACFLT); and “Mediterranean” might refer to the Sixth Fleet. Yet I’m not convinced that organization is the whole story; the Atlantic numbers didn’t suddenly increase when the Mediterranean numbers dropped to zero.

The declassified afloat numbers end in 1991. After that year the only nuclear weapons deployed at sea have been strategic weapons onboard ballistic missile submarines. Most of those deploy in the Atlantic and Pacific but have occasionally deployed into the Mediterranean even after the declassified documents list zero afloat weapons in that region, and even after the surface fleet was denuclearized.

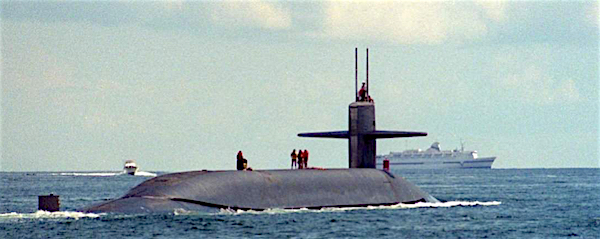

In 1999, for example, the ballistic missile submarine USS Louisiana (SSBN-743) conducted a port visit to Souda Bay on Crete with it load of 24 Trident missiles and an estimated 192 warheads. The ship’s Command History states that the port visit, which took place December 12-16, 1999, occurred during the “Alert Strategic Deterrent Patrol in support of national tasking” that included a “Mediterranean Sea Patrol.”

Risks of Nuclear Accidents

Deploying nuclear weapons on ships and submarines created unique risks of accidents and incidents. Because warships sometimes collide, catch fire, or even sink, it was only a matter of time before the nuclear weapons they carried were threatened, damaged, or lost. This really happened.

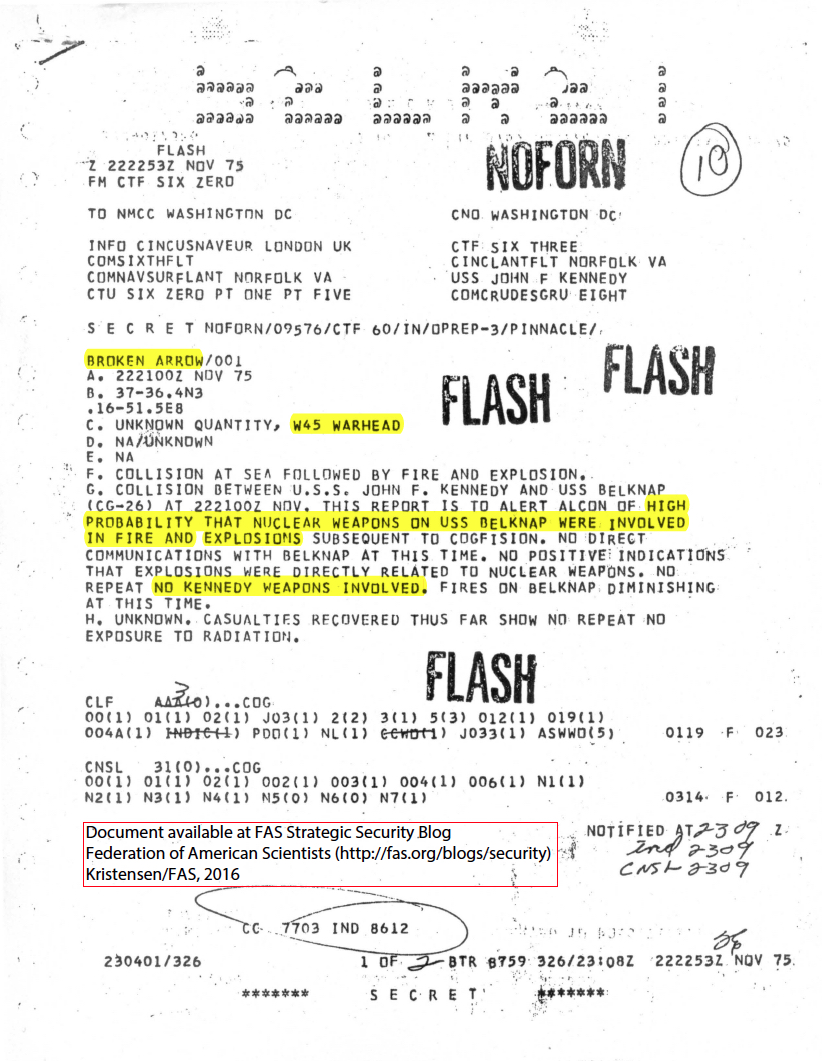

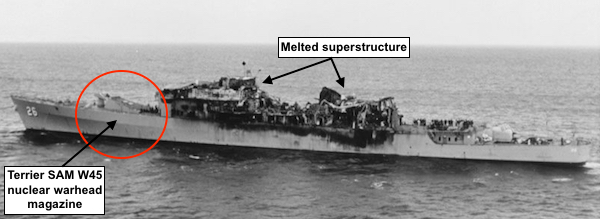

During night air exercises on November 22, 1975, for example, the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) and cruiser USS Belknap (CG-26) collided in rough seas 112 kilometers (70 miles) east of Sicily. The carrier’s flight deck cuts into the superstructure of the Belknap setting off fires on the cruiser, which burned out of control for two-and-one-half hours. The commander of Carrier Striking Force for the U.S. Sixth Fleet on board the Kennedy issues a Broken Arrow alert to higher commands stating there was a “high probability that nuclear weapons (W45 Terrier missile warheads) on the Belknap were involved in fire and explosions.” Eventually the fire was stopped only a few meters from Belknap’s nuclear weapons magazine.

The fire-damaged USS Belknap (CG-26) after colliding with USS John F. Kennedy (CV-67) new Sicily in 1975. The fire stopped a few meters from the nuclear warhead magazine.

The Kennedy also carried nuclear weapons, approximately 100 gravity bombs for delivery by aircraft. The carrier caught fire but luckily it was relatively quickly contained. Another carrier, the USS Enterprise (CVN-65), had been less fortunate six years earlier when operating 112 kilometers (70 miles) southwest of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. A rocket on a F-4 Phantom aircraft exploded puncturing fuel tanks and starting violent fires that caused other rockets and bombs to explode. The explosions were so violent that they tore holes in the carrier’s solid steel deck and engulfed the entire back of the ship. The captain later said: “If the fire had spread to the hangar deck [below], we could have very easily lost the ship.” The Enterprise probably carried about 100 nuclear bombs and was powered by eight nuclear reactors.

The nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered USS Enterprise (CVN-65) burns off Hawaii on January 14, 1969. The carrier could have been lost, the captain said.

Dozens of nuclear weapons were lost at sea over the decades because they were on ships, submarines, or aircraft that were lost. On December 5, 1965, for example, while underway from operations off Vietnam to Yokosuka in Japan, an A-4E aircraft loaded with one B43 nuclear weapon rolled overboard from the Number 2 Elevator. The aircraft sank with the pilot and the bomb in 2,700 fathoms (4,940 meters) of water. The bomb has never been recovered. The Department of Defense reported the accident took place “more than 500 miles [805 kilometers] from land” when it revealed the accident in 1981. But Navy documents showed the accident occurred about 80 miles (129 kilometers) east of the Japanese Ryukyu Island chain, approximately 250 miles (402 kilometers) south of Kyushu Island, Japan, and about 200 miles (322 kilometers) east of Okinawa. Japan’s public policy and law prohibit nuclear weapons. (For a video if B43 aircraft carrier handling and A-4 loading, see this video.)

An A-4 Skyhawk with a B43 nuclear bomb under its belly rises on an elevator from the hangar deck to the flight deck on the USS Independence (CV-62) in an undated US Navy photo. In December 1965, a B43 attached to an A-4 rolled off the elevator on the USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14) while the carrier was on its way to Yokosuka in Japan.

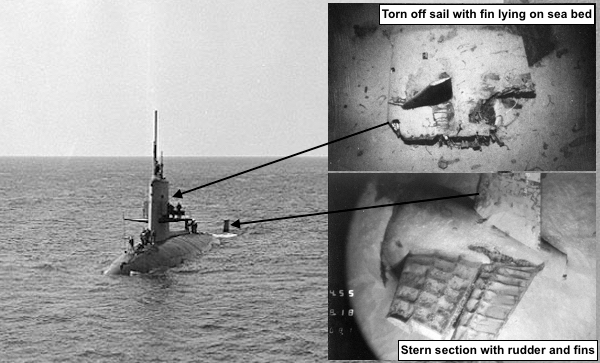

Three years later, on May 27, 1968, the nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Scorpion (SSN-589) suffered an accident and sank with all 99 men on board in the Atlantic Ocean approximately 644 kilometers (400 miles) southwest of the Azores. The Department of Defense in 1981 mentioned a nuclear weapons accident occurred in the Atlantic in the spring of 1968 but continues to classify the details. It is thought that two nuclear ASTOR torpedoes were on board the Scorpion when it sank.

The USS Scorpion (SSN-589) photographed in the Mediterranean Sea in April 1968, one month before it sank in the Atlantic Ocean. The Navy later located and photographed the wreck (inserts).

Risks of Nuclear Incidents

Another kind of risk was that nuclear weapons onboard US warships could become involved in offensive maneuvers near Soviet warships that also carried nuclear weapons. Sometimes those nuclear-armed vessels collided – sometimes deliberately. Other times they were trapped in stressful situation. The presence of nuclear weapons could significantly increase the stakes and symbolism of the incidents and escalate a crisis.

Some of the most dramatic incidents happened during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962 where crisis-stressed personnel on Soviet nuclear-armed submarines readied nuclear weapons for actual use as they were being hunted by US naval forces, many of which were also nuclear-armed. At the time there were approximately 750 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in the Atlantic Ocean.

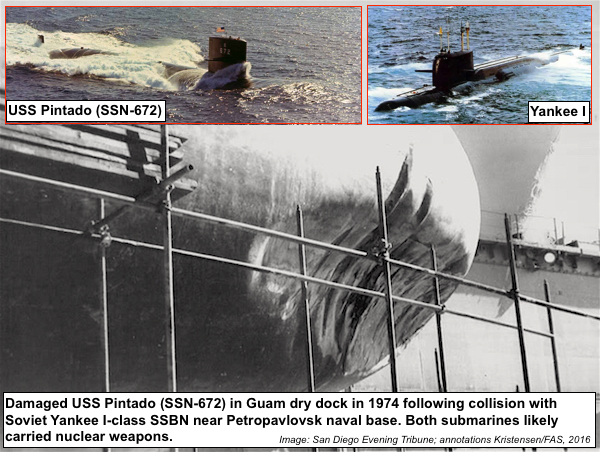

Less serious but nonetheless potentially dangerous incidents continued throughout the Cold War. In May 1974 the nuclear-powered attack submarine USS Pintado (SSN-672) collided almost head-on with a Soviet Yankee I-class ballistic missile submarine while cruising 200 feet (60 meters) below the surface in the approaches to the Petropavlovsk naval base on the Kamchatka Peninsula. The collision smashed much Pintado’s bow sonar, jammed shut a starboard side torpedo hatch, and damaged the diving plane. The Pintado, which probably carried 4-6 nuclear SUBROC missiles, sailed to Guam for seven weeks of repairs. The Soviet submarine, which probably carried its complement of 16 SS-N-6 ballistic missiles with 32 nuclear warheads, surfaced immediately and presumably limped back to port.

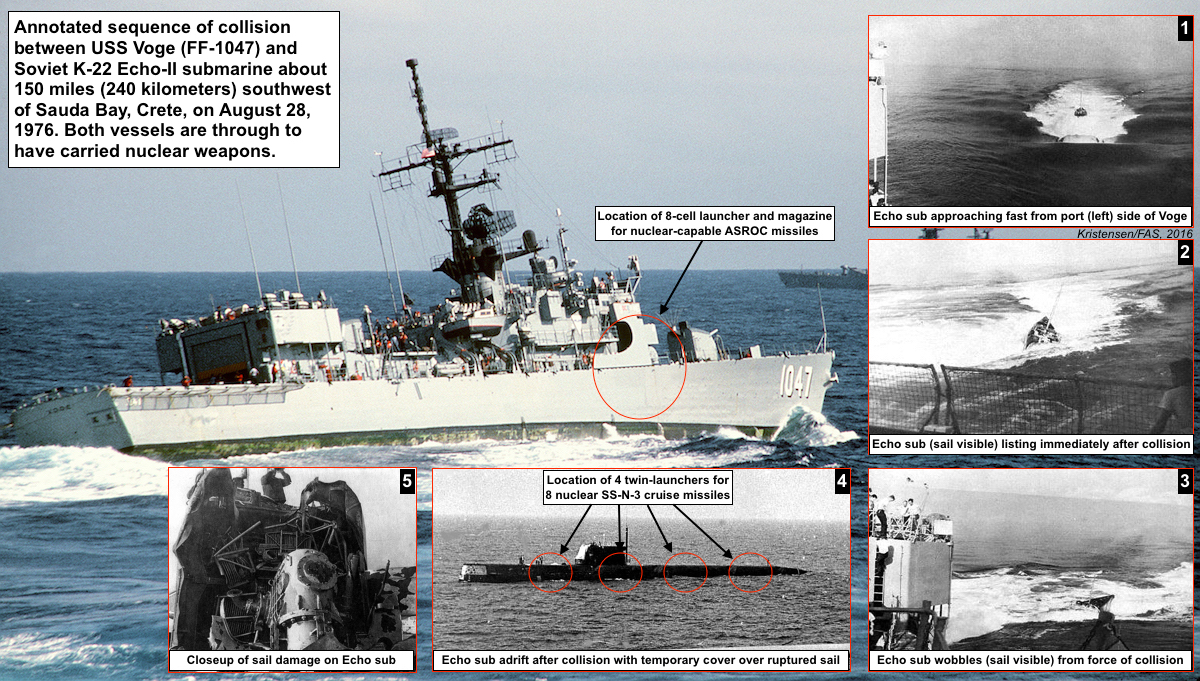

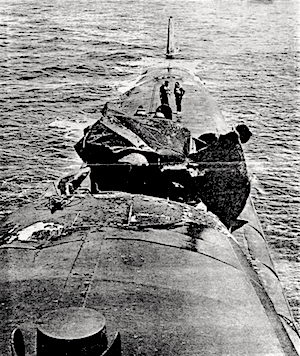

On August 22, 1976, for example, US anti-submarine forces in the Atlantic and Mediterranean had been tracking a Soviet nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed Echo II-class attack submarine for ten days. The Soviet sub partially surfaced alongside the US frigate USS Voge (FF-1047), then turned right and ran into the frigate. The collision tore off part the Voge’s propeller and punctured the hull. The Voge is thought to have carried nuclear ASROC anti-submarine rockets. At the time there were around 430 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in the Mediterranean Sea. The Soviet submarine suffered serious damage to its sail and some to its front hull section. (For a US account of the incident, see here; a Russian account is here.)

A starboard view of the frigate USS VOGE (FF-1047) conducting a high speed evasive maneuver while operating with the aircraft carrier USS JOHN F. KENNEDY (CV-67) battle group.

Even toward the very end of the Cold War in the late-1980s, nuclear-capable warships continued to get involved in serious incidents at sea. During a Freedom of Navigation exercise in the Black Sea on February 12, 1988, the cruiser USS Yorktown (CG-48) and destroyer USS Caron (DD-970) were bumped by a Soviet Krivak-class frigate and a Mirka-class frigate, respectively. Both U.S. ships were equipped to carry the nuclear-capable ASROC missile and the Caron had completed a series of nuclear certification inspections prior to its departure from the United States. Yet the W44 warhead for the ASROC was in the process of being phased out and it is possible that the vessels did not carry nuclear warheads during the incident. The declassified data shows that the number of U.S. nuclear weapons in the Mediterranean dropped to zero in 1987. The Soviet Krivak frigate, however, probably carried nuclear anti-submarine weapons at the time of the collision.

Nuclear Diplomacy Headaches

In addition to the risks created by accidents and incidents, nuclear-armed warships were a constant diplomatic headache during the Cold War. Many U.S. allies and other countries did not allow nuclear weapons on their territory in peacetime but the United States insisted that it would neither confirm nor deny the presence of nuclear weapons anywhere. So good-will port visits by nuclear-armed warships instead turned into diplomatic nightmares as protestors battled what they considered blatant violations of the nuclear ban.

The port visit protests were endless, happening in countries all over the world. The national governments were forced to walk a fine line between their official public anti-nuclear policies and the secret political arrangements that allowed the weapons in anyway.

Public sentiments were particularly strong in Japan because it was the target of two nuclear weapon attacks in 1945. Japanese law banned the presence of nuclear weapons on its territory and required consultation prior to introduction, but the governments secretly accepted nuclear weapons in Japanese ports.

During the 1970s and early-1980s, opposition to nuclear ship visits grew in New Zealand and in 1984 culminating in the David Lange government banning visits by nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed vessels. The Reagan administration reacted angrily by ending defense cooperation with New Zealand under the ANZUS alliance. Only much later, during the Obama administration, have defense relations been restored.

The nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed attack submarine USS Haddo (SSN-604) is barraged by protestors during a port visit to Auckland in New Zealand in 1979.

The treatment of New Zealand was partially intended to deter other more important allies in Europe from adopting similar anti-nuclear legislation. But not surprisingly, the efforts backfired and instead increased opposition. In Denmark the growing evidence that nuclear weapons were actually being brought into Danish harbors despite its clear prohibition soon created political pressure to tighten up the ban. In 1988, this came to a head when a majority in the parliament adopted a resolution requiring the government to inform visiting warships of Denmark’s ban. The procedure did not require the captain to reveal whether his ship carried nuclear weapons, but the conservative government called an election and asked the United States to express its concern.

The crew of the nuclear-armed destroyer USS Conyngham (DDG-17) uses high-pressure hoses to wash anti-nuclear protestors off its anchor chain during a standoff in Aalborg, Denmark, in 1988.

Across the Danish Straits in Sweden, the growing evidence that non-nuclear policies were violated in 1990 resulted in the government party deciding to begin to reinforce Sweden’s nuclear ban. The policy would essentially have created a New Zealand situation in Europe, a political situation that was a direct threat to the US Navy sailing its nuclear warships anyway it wanted.

These diplomatic battles over naval nuclear weapons were so significant that many US officials gradually began to wonder if nuclear weapons at sea were creating more trouble than good.

After The Big Nuke Offload

Finally, on September 27, 1991, President George H.W. Bush announced during a primetime televised address that the United States would unilaterally offload all non-strategic nuclear weapons from its naval forces, bring all those weapons home, and destroy many of them. Warships would immediately stop loading nuclear weapons when sailing on overseas deployments and deployed vessels would offload their weapons as they rotated back to the United States. The offload was completed in mid-1992.

Two years later, the Clinton administration’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review, decided that all surface ships would loose the capability to launch nuclear weapons. Only selected attack submarines would retain the capability to fire the nuclear Tomahawk land-attack sea-launched cruise missile (TLAM/N), but the weapons would be stored on land. Sixteen years later, in 2010, the Obama administration decided to retire the TLAM/N as well, ending decades of nuclear weapons deployments on ships, attack submarines, and on land-based naval air bases.

After the summer of 1992, only strategic submarines armed with long-range ballistic missiles have carried U.S. nuclear weapons at sea, a practice that is planned to continue through at least through the 2080s. These strategic submarines (SSBNs) have also been involved in accidents and incidents, risks that will continue as long as nuclear weapons are deployed at sea. Because secrecy is so much tighter for SSBN operations than for general naval forces, most accidents and incidents involving SSBNs probably escape public scrutiny. But a few reports, mainly collisions and groundings, have reached the public over the years.

USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) after collision with tanker Sealady.

During a strategic deterrent patrol on August 9, 1968, the USS Von Steuben (SSBN-632) was struck by a submerged tow cable while operating submerged about 40 miles (64 kilometers) off the southern coast of Spain. As it surfaces, the submarine collides with the tanker Sealady, suffering damage to the superstructure and main deck (see image right). The submarine carried 16 Polaris A3 ballistic missiles with 48 nuclear warheads.

Two years later, on November 29, 1970, a fire breaks out onboard the nuclear submarine tender USS Canopus (AS-34) at the Holy Loch submarine base in Scotland. Two nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (USS Francis Scott Key (SSBN-657) and USS James K. Polk (SSBN-645)) were moored alongside Canapus. The Francis Scott Key cast off, but the Polk remained alongside. The fire burns out of control for four hours killing three men. The submarine tender carried nuclear missiles and warheads and the two submarines combined carried 32 Polaris A3 ballistic missiles with a total of 96 nuclear warheads.

Four years later, in November 1974, after having departed from its base at Holy Loch in Scotland, the ballistic missile submarine USS James Madison (SSBN-627) collides with a Soviet submarine in the North Sea. The collision left a nine-foot scrape in the Madison, which apparently dove onto the Soviet submarine, thought to have been a Victor-class nuclear-powered attack submarine. The Madison carried 16 Poseidon (C3) ballistic missiles with 160 nuclear warheads. The Soviet submarines probably carried nuclear rockets and torpedoes. Madison crew members called the incident The Victor Crash. Two days after the collision, the Madison enters dry dock at Holy Loch for a week of inspection and repairs.

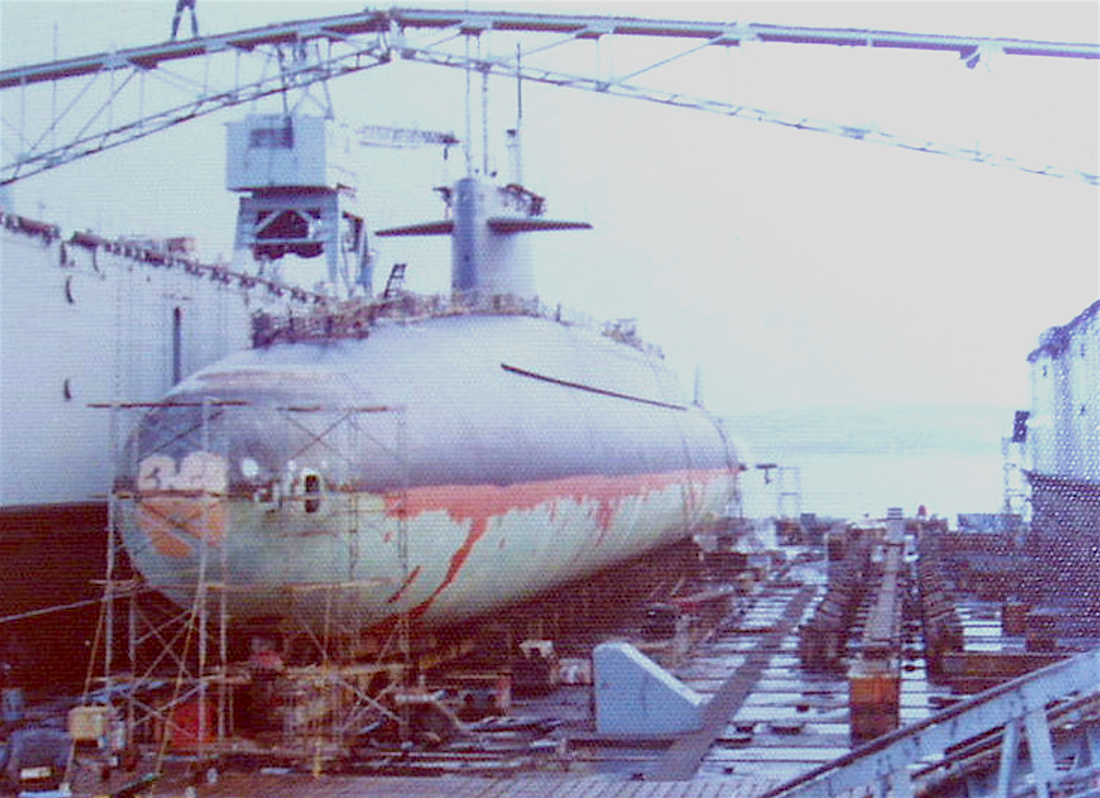

The missile submarine USS James Madison (SSBN-627) in dry dock in Scotland in 1974 only days after it collided with a Soviet Victor-class nuclear-powered attack submarine in the North Sea.

After nuclear weapons were offloaded from surface ships and attack submarines in 1991-1992, nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines have continued to run aground or bump into other vessels from time to time.

On September 24, 1993, for example, after conducting a medical evacuation for a suck crew member, the ballistic missile submarine USS Maryland (SSBN-738) ran aground at Port Canaveral, Florida. The submarine was on a strategic deterrent patrol with 24 missiles onboard carrying an estimated 192 warheads. The Maryland eventually pulled free and continued the patrol two days later.

On March 19, 1998, while operating on the surface 125 miles (200 kilometers) off Long Island, New York, the ballistic missile submarine USS Kentucky (SSBN-737) was struck by the attack submarine USS San Juan (SSN-751). The Kentucky suffered damaged to its rudder and San Juan’s forward ballast tank was ruptured. In a typical display of silly secrecy, the Navy refused to say whether the Kentucky carried nuclear weapons. But it did; the Kentucky was in the middle of its 21st strategic deterrent patrol and carried its complement of 24 Trident II missiles with an estimated 192 nuclear warheads.

In 1998, the USS Kentucky (SSBN-737) carrying nearly 200 nuclear warheads collided with an attack submarine less than 230 miles (378 kilometers) from New York City.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Obama administration has made an important contribution to nuclear policy by declassifying the documents with official numbers of US nuclear weapons deployed at sea during the Cold War. This adds an important chapter to the growing pool of declassified information about the history of the U.S. nuclear arsenal.

The new declassified information helps us better understand the extent to which nuclear weapons were involved in day-to-day operations around the world. Every day, nuclear-armed warships of the US and Soviet navies were rubbing up against each other on the high seas in gong-ho displays of national determination. Some saw it as necessary for nuclear deterrence; others as dangerous nuclear brinkmanship. Many of those who were on the ships submarines still get goosebumps when they talk about it and wonder how we survived the Cold War. The tactical naval nuclear weapons were considered more acceptable to use early in a conflict because there would be few civilian casualties. But any use would probably quickly have escalated into large-scale nuclear war and the end of the world as we know it.

The declassified information, when correlated with the many accidents and incidents that nuclear-armed ships and submarines were involved in over the years, also helps us remember a key lesson about nuclear weapons: when they are operationally deployed they will sooner or later be involved in accidents and incidents.

This is not just a Cold War lesson: thousands of nuclear weapons are still operationally deployed on ballistic missile submarines, on land-based ballistic missiles, and on bomber bases. And not just in the United States but also in Britain, France, and Russia. Some of those deployed weapons will have accidents in the future. (See here for the most recent.)

Moreover, growing tensions with Russia and China now make some ask if the United States needs to increase the role of its nuclear weapons and once again equip aircraft carriers with the capability to deliver nuclear bombs and once again develop and deploy nuclear land-attack sea-launched cruise missiles on attack submarines.

Doing so would be to roll back the clock and ignore the lessons of the Cold War and likely make the current tensions worse than they already are.

Instead, the United States should seek to work with Russia – even though it is challenging right now – to reduce deployed nuclear weapons and jointly try to persuade smaller nuclear-armed countries such as China, India, and Pakistan from increasing the operational readiness of their nuclear forces. That ought to be one thing Russia and the United States could actually agree on.

Background information:

- Department of Defense, “Nuclear Weapons Afloat: End of Fiscal Years 1953-1991,” n.d.

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Declassified: US Nuclear Weapons at Sea During the Cold War, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, February 2016.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

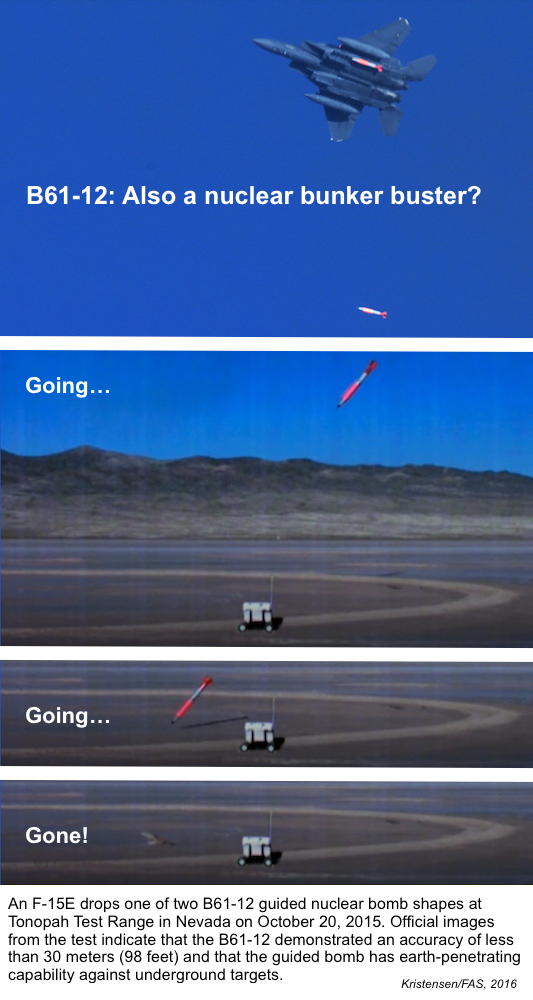

Video Shows Earth-Penetrating Capability of B61-12 Nuclear Bomb

The capability of the new B61-12 nuclear bomb seems to continue to expand, from a simple life-extension of an existing bomb, to the first U.S. guided nuclear gravity bomb, to a nuclear earth-penetrator with increased accuracy.

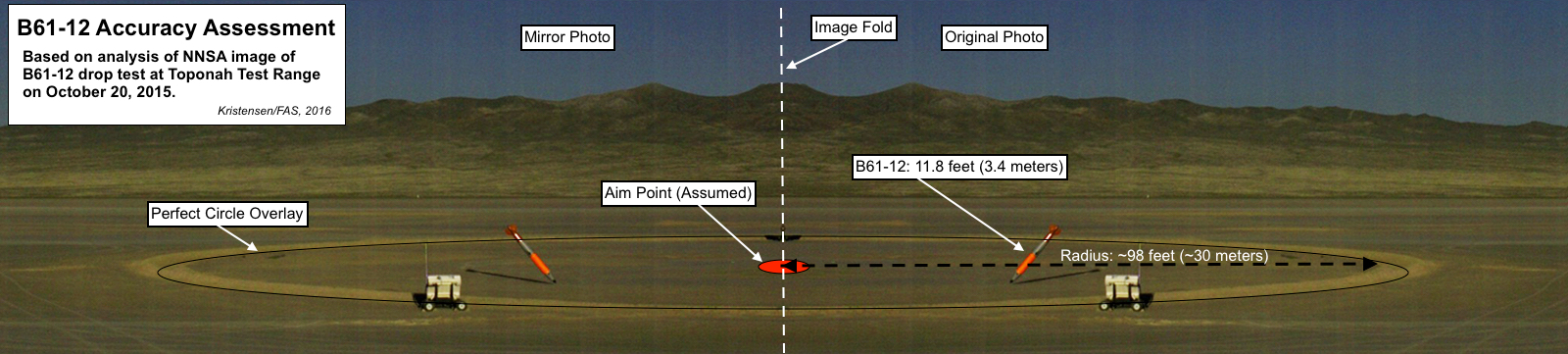

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) previously published pictures of the drop test from October 2015 that showed the B61-12 hitting inside the target circle but without showing the bomb penetrating underground.

But a Sandia National Laboratories video made available by the New York Times shows the B61-12 penetrating completely underground. (A longer version of the video is available at the Los Alamos Study Group web site.)

Implication of Earth-Penetration Capability

The evidence that the B61-12 can penetrate below the surface has significant implications for the types of targets that can be held at risk with the bomb. A nuclear weapon that detonates after penetrating the earth more efficiently transmits its explosive energy to the ground, thus is more effective at destroying deeply buried targets for a given nuclear yield. A detonation above ground, in contrast, results in a larger fraction of the explosive energy bouncing off the surface. Two findings of the 2005 National Academies’ study Effects of Earth-Penetrator and other Weapons are key:

“The yield required of a nuclear weapon to destroy a hard and deeply buried target is reduced by a factor of 15 to 25 by enhanced ground-shock coupling if the weapon is detonated a few meters below the surface.”

And

“Nuclear earth-penetrator weapons (EPWs) with a depth of penetration of 3 meters capture most of the advantage associated with the coupling of ground shock.”

Given that the length of the B61-12 is about three-and-a-half meters, and that the Sandia video shows the bomb disappearing completely beneath the surface of the Nevada desert, it appears the B61-12 will be able to achieve enhanced ground-shock coupling against underground targets in soil. We know that the B61-12 is designed to have four selectable explosive yields: 0.3 kilotons (kt), 1.5 kt, 10 kt and 50 kt. Therefore, given the National Academies’ finding, the maximum destructive potential of the B61-12 against underground targets is equivalent to the capability of a surface-burst weapon with a yield of 750 kt to 1,250 kt.

One of the bombs the Pentagon plans to retire after the B61-12 is deployed is the B83-1, which has a maximum yield of 1,200 kt.

Even at the lowest selective yield setting of only 0.3 kt, the ground-shock coupling of a B61-12 exploding a few meters underground would be equivalent to a surface-burst weapon with a yield of 4.5 kt to 7.5 kt.

Implications of Increased Accuracy

Existing B61 versions (B61-3, -4, 7, -10) are thought to have some limited earth-penetration capability but with much less accuracy than the B61-12. The only official nuclear earth-penetrator in the U.S. arsenal, the unguided B61-11, compensates for poor accuracy with a massive yield: 400 kt. The ground-shock coupling of 400 kt, using the National Academies’ finding, is equivalent to the effect of a surface-burst of 6 Megatons (MT) to 10 MT. The B61-11 replaced the old B53, the Cold War bunker buster bomb, which had a yield of 9 MT. The B61-11 can penetrate into frozen soil; it is yet unknown if the B61-12 has a similar capability. Currently there is no life-extension planned for the B61-11, which is not part of NNSA’s so-called 3+2 stockpile plan and is expected to be phased out when it expires in the 2030s.

What makes the B61-12 special is that the B61 capability is enhanced by the increased accuracy provided by the new guided tail kit assembly, a unique feature of the new weapon. The combination of increased accuracy with earth-penetration and low-yield options provides for unique targeting capabilities. Moreover, while the B61-11 can only be delivered by the B-2 strategic bomber, the B61-12 will be integrated on virtually all nuclear-capable U.S. and NATO aircraft: B-2, LRS-B (next-generation long-range bomber), F-35A, F-16, F-15E, and PA-200 Tornado.

How accurate the B61-12 will be is a secret. In an article from 2011 we estimated the accuracy might be on the order of 30-plus meters. Back then no test drop had been conducted and we didn’t have imagery. But now we do.

We cannot see with certainty on the NNSA photo and Sandia video how accurate the November 2015 drop test was. The video and image clearly show the B61-12 impacting the ground well within a large circle. Unfortunately the imagery does not show the full circle and the low angle makes it hard to determine the diameter. But by flipping the image horizontally and combining the copy with the original, the two appear to make a nearly perfect circle. Because we know the length of the B61-12 (11.8 feet; 3.4 meters), it appears the circle has a diameter of approximately 197 feet (60 meters). Since the point of impact is well within circle (roughly one bomb length inside), the B61-12 appears to have hit less than 100 feet (30 meters) from the center of the circle (see analysis of NNSA photo below).

Accuracy of a weapon is expressed as CEP (Circular Error Probability), which is defined as the radius of a circle centered at the target aim-point within which 50% of the weapons will fall. Formally estimating the accuracy of the B61-12 requires more information than the ground zero location of the drop test in the November 2015 event. Even so, the image indicates that at least the November 2015 drop test impacted well within the 30-meter diameter circle.

Little is known in public about the accuracy of nuclear gravity bombs. But information previously released by the U.S. Air Force to Kristensen under the Freedom of Information Act states that drop tests in the late-1990s normally achieved an accuracy of 380 feet (116 meters) for both high- and low-altitude releases and occasionally down to around 300 feet (91 meters) for low-altitude bombing runs.

In other words, although formal and more comprehensive data is missing, the November 2015 drop test indicates a B61-12 performance three times more accurate than existing non-guided gravity bombs.

That increased accuracy and earth-penetration capability will allow strike planners to chose lower selectable yields than are needed with the accuracy of current B61 and B83 bombs to destroy the same targets. Selecting lower yields will reduce the radioactive fallout from an attack, a feature that would make a B61-12 attack more attractive to military planners and less controversial to political decision makers.

Contradictions

The ability of the B61-12 to penetrate below the surface before detonating as seen on the video will further increase the capability against underground targets, especially when combined with the improved accuracy. This opens up a range of options for destroying underground targets with lower selectable nuclear yield settings than with the bombs in the current arsenal. We believe this constitutes an enhanced military capability that is in conflict with the Obama administration’s stated policy not to develop new capabilities for nuclear weapons.

The New York Times article is well written because it captures the contradiction between the denial by some officials (in this case NNSA’s Madelyn Creedon) that the B61-12 has new military capabilities while others (in this case former under secretary of defense for policy James Miller) seem to think it is a good thing that it does.

To that end the article is astute because it quotes the White House pledge not to pursue new military capabilities:

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads or pursue new military mission or new capabilities for nuclear weapons.”

…instead of using the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) Report formulation:

“The United States will not develop new nuclear warheads. Life Extension Programs (LEPs) will use only nuclear components based on previously tested designs, and will not support new military missions or provide for new military capabilities.”

This is important because the NPR formulation is a little less clear and is being used by some officials and defense contractors to argue that the pledge not to pursue new military missions or new military capabilities only refers to the warhead itself and not nuclear weapons in general. That may seem pedantic so the White House statement helps clarify, in case anyone is confused, that the policy indeed applies to “weapons” and not just “warheads.”

The officials who claim the B61-12 will not have new military capabilities say so because the United States already has the capability to hold at risk surface and underground targets, or to the fact that the warhead within the bomb –the so-called “physics package” –remains the same Cold War design. But the combination of increased accuracy and limited earth-penetrating capability allow the B61-12 to threaten below-ground structures with less radioactive fallout. That is a new military capability.

Back in 2011, before the B61-12 development program had progressed to the point of no return, FAS sent a letter to the White House and the Office of the Secretary of Defense pointing out the contradiction with the administration’s policy and implications for nuclear strategy. They never responded.

Worrying about the Bomb

The B61-12 earth-penetration capability may be less than the existing B61-11 earth-penetrator and the accuracy less than a conventional GPS-guided smart bomb, but the Sandia video shows a versatile new weapon that is intended for deployment on both strategic and non-strategic aircraft in the United States and Europe.

Such a capability begs the question of which targets in which countries are envisioned for B61-12 missions, and under what circumstances could use of such a weapon be ordered by the President? The National Academies’ study also found that earth penetration by a nuclear weapon could not contain the effects of the nuclear explosion, and that casualties would likely be the same as if the weapon were detonated at the surface of the earth. These findings particularly speak to the implications of dropping the B61-12 on a bunker located underneath a city.

Moreover, the significant improvements being made to non-nuclear earth-penetrators begs the question why it is necessary to enhance the capabilities of the B61 gravity bomb in the first place.

Both the United State and Russia (and the other nuclear-armed states) have extensive and expensive nuclear force modernization programs underway. What we are seeing today lies somewhere between parallel efforts to refurbish Cold War arsenals and the emergence of a new arms competition fueled by enhancements to existing weapons or production of new or significantly modified types. These enhancements are being developed without nuclear test explosions.