After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

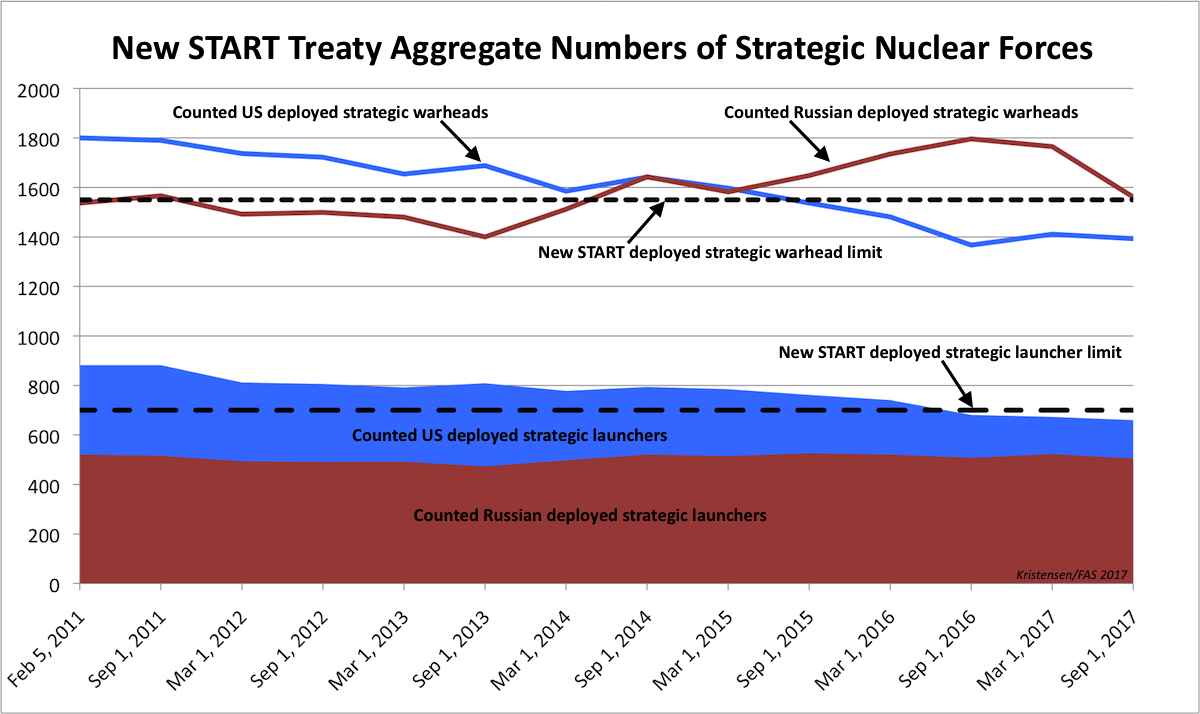

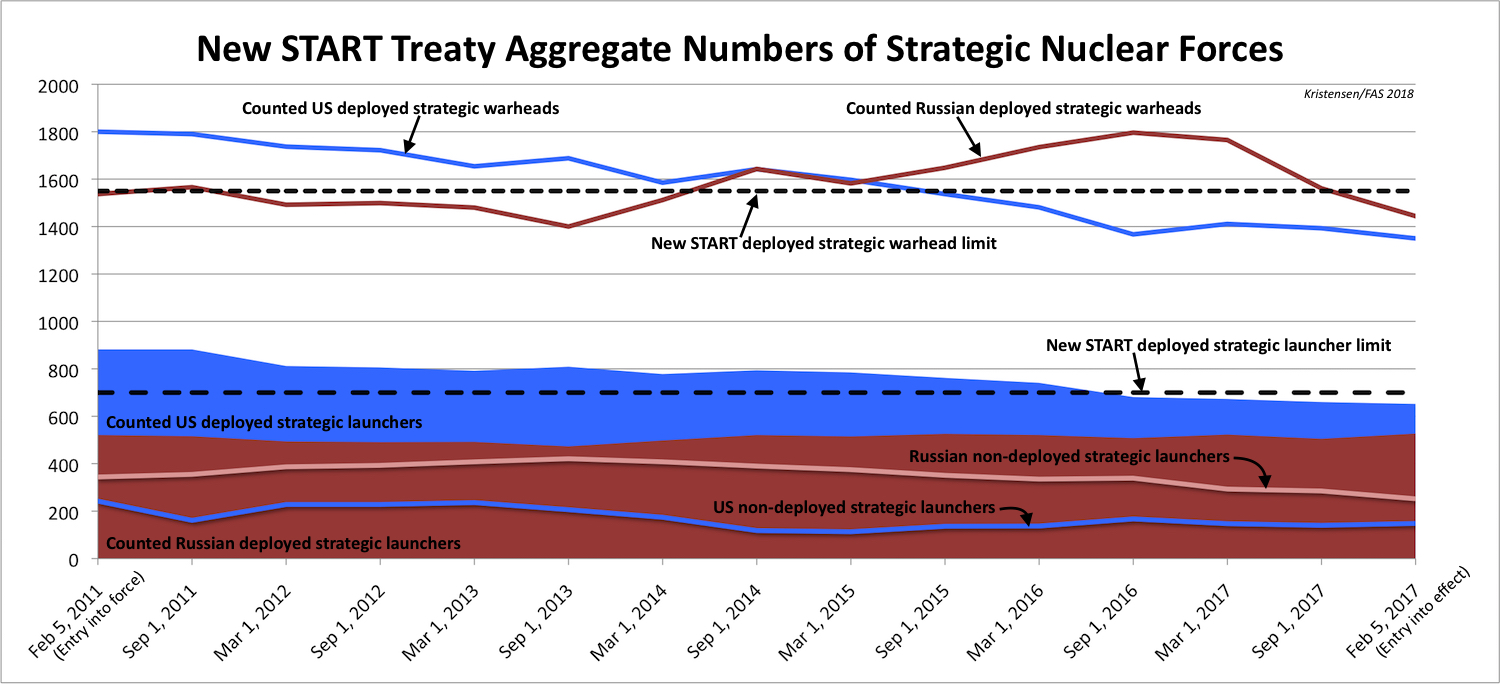

Russia and the United States are currently in compliance with the treaty limits of the New START treaty. This table summarizes the evolution of the three weapons categories reported between 2011 and 2018. (Click on graph to view full size.)

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Note: On February 22nd, the US State Department published updated numbers instead of relying on September 2017 numbers. This blog and tables have been updated accordingly.]

Seven years after the New START treaty between Russia and the United States entered into force in 2011, the treaty entered into effect on February 5. The two countries declared they have met the limits for strategic nuclear forces.

At a time when relations between the two countries are at a post-Cold War low and defense hawks in both countries are screaming for new nuclear weapons and declaring arms control dead, the achievement couldn’t be more timely or important.

Achievements by the Numbers

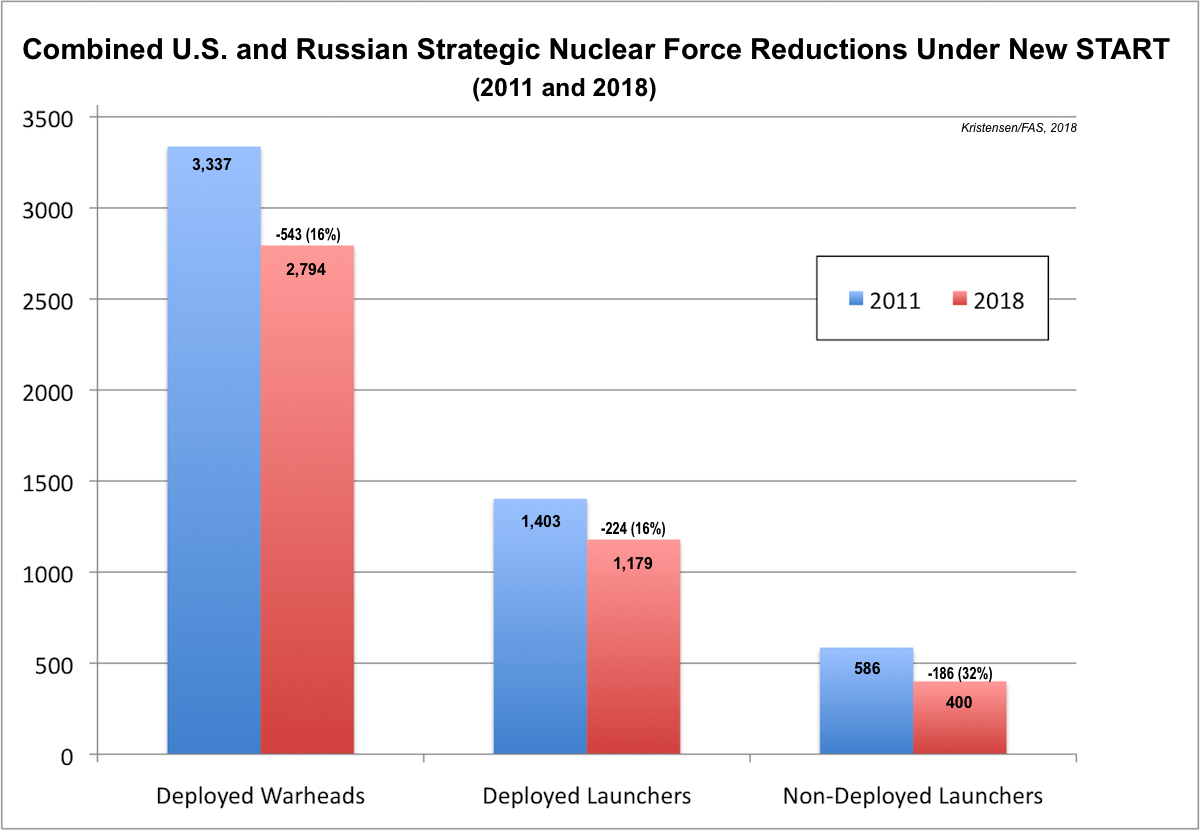

The declarations show that Russia and the United States currently deploy a combined total of 2,794 warheads on 1,179 deployed strategic launchers. An additional 400 non-deployed launchers are empty, in overhaul, or awaiting destruction.

Compare that with the same categories in 2011: 3,337 warheads on 1,403 deployed strategic launchers with an additional 586 non-deployed launchers.

In other words, since 2011, the two countries have reduced their combined strategic forces by: 543 deployed strategic warheads, 224 deployed strategic launchers, and 186 non-deployed strategic launchers. These are modest reductions of about 16 percent over seven years for deployed forces (see chart below).

The New START data shows the world’s two largest nuclear powers have reduced their deployed strategic force by about 15 percent over the past seven years. (Click on graph to view full size.)

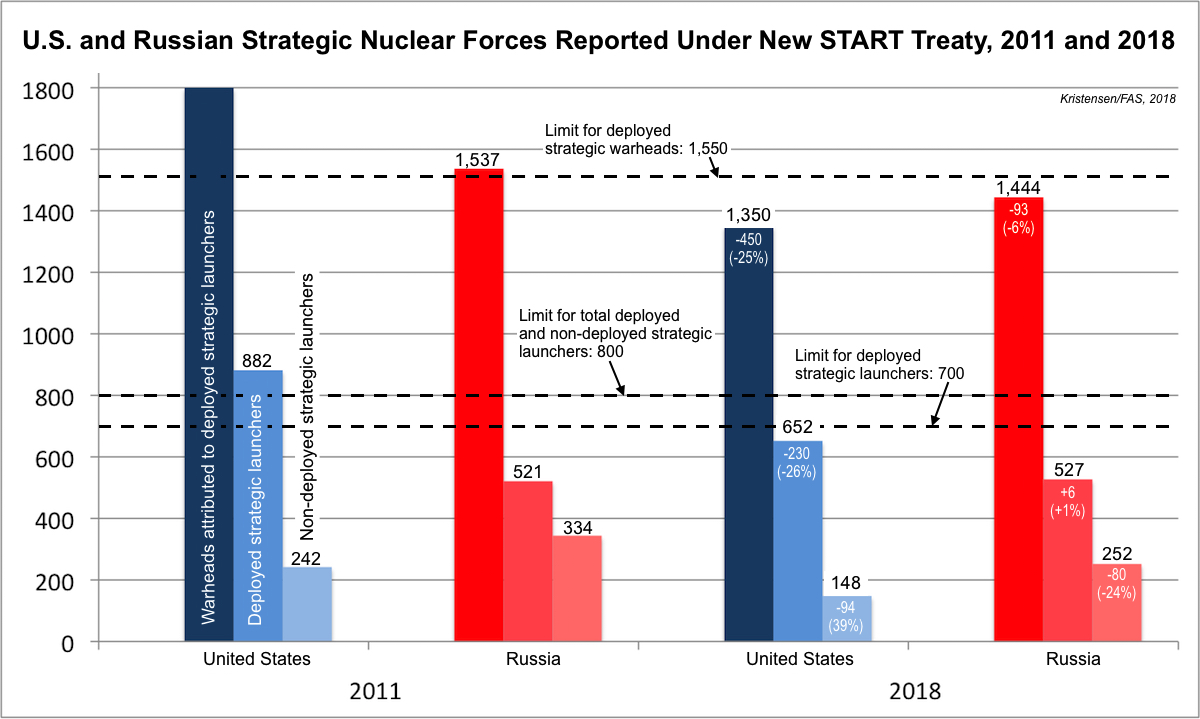

The Russian statement reports 1,444 warheads on 527 deployed strategic launchers with another 392 non-deployed launchers.

That means Russia since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 93, or only 6 percent. The number of deployed launchers has increased a little, by 6, while non-deployed launchers have declined by 80, or 24 percent (see chart below).

The Russian numbers hide an important new development: In order to meet the New START treaty limit, the warhead loading on some Russian strategic missiles has been reduced. The details of the download are not apparent from the limited data published by Russia. I am currently working on developing the estimate for how the download is distributed across the Russian strategic forces. The analysis will be published in a subsequent blog, as well in our next FAS Nuclear Notebook and in the 2018 SIPRI Yearbook.

The US statement lists 1,350 warheads on 652 deployed strategic launchers, and 148 non-deployed launchers.

That means the United States since 2011 has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 450, or 25 percent. The number of deployed launchers has been reduced by 230, or 26 percent, while the number of non-deployed launchers had declined by 94, or 39 percent (see chart below).

US and Russian strategic force structures differ significantly. As a result, the reductions under New START have affected the two countries differently. Russia has significantly fewer launchers so rely on great warhead-loading to maintain rough overall parity. (Click on chart to view full size.)

In Context

The reason for the different reductions is, of course, that the United States in 2011 had significantly more warheads and launchers deployed than Russia. During the New START negotiations, the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit than proposed by Russia. So while Russia by the latest count has 94 deployed warheads more than the United States, the United States enjoys a sizable advantage of 125 deployed strategic launchers more than Russia. Those extra launchers have a significant warhead upload capacity, a potential treaty breakout capability that Russian officials often complain about.

So despite the importance of the New START treaty and its achievements, not least its important verification regime, the declared numbers are a reminder of how far the two nuclear superpowers still have to go to reduce their unnecessarily large nuclear forces. Ironically, because the US military insisted on a higher launcher limit, Russia could – if it decided to do so, although that seems unlikely – build up its strategic launchers to reduce the US advantage, and still be in compliance with the treaty limits. The United States, in contrast, is at full capacity.

But the apparent download of warheads on Russia’s strategic missiles demonstrates an important effect of New START: It actually keeps a lid on the strategic force levels.

Still, not to forget: The deployed strategic warhead numbers counted under New START represent only a portion of the total number of warheads the two countries have in the arsenals. We estimate that the deployed strategic warheads declared by the two countries represent on about one-third of the total number of warheads in their nuclear stockpiles (see here for details).

This all points to the importance of the two countries agreeing to extend the New START treaty for an additional five years before it expires in 2021. Neither can afford to abandon the only strategic limitations treaty and its verification regime. Failing this most basic responsibility would, especially in the current political climate, remove any caps on strategic nuclear forces and potentially open the door to a new nuclear arms race. The warning signs are all there: East and West are in an official adversarial relationship, increasing military posturing, modernizing and adding nuclear weapons to their arsenals, and adjusting their nuclear policies for a return to Great Power competition.

The symbolic importance of New START could not be greater!

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Data Shows Detail About Final Phase of US New START Treaty Reductions

By Hans M. Kristensen

The full unclassified New START treaty data set released by State Department yesterday shows that the US reduction of its nuclear forces to meet the treaty limit had been completed by September 1, 2017, more than four months early before the deadline next month on February 5, 2018.

The data set reveals details about how the final reduction was achieved (see below).

Unfortunately, no official detailed data is released about the Russian force adjustments under New START. Our previous analysis of the overall September 1, 2017 New START data is available here.

Submarines

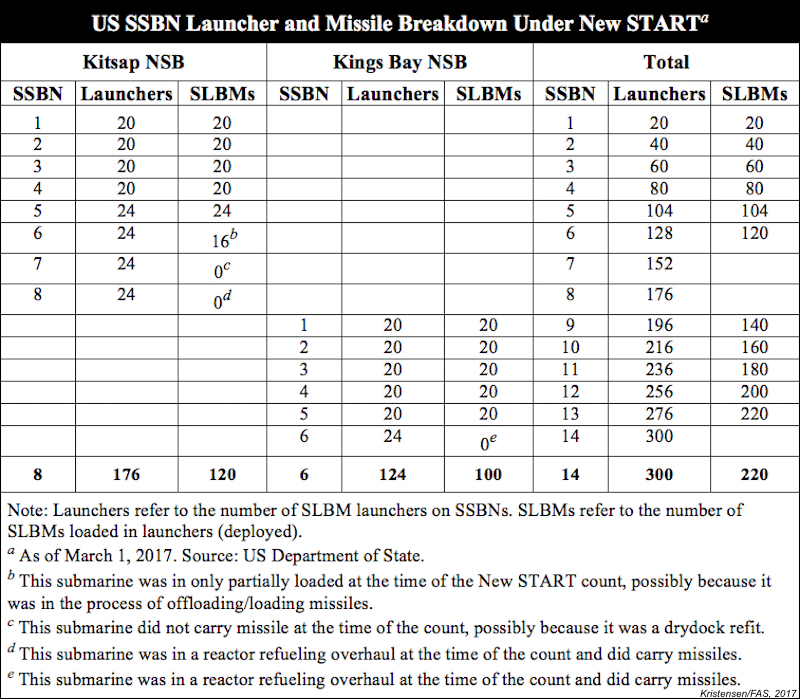

During that six-month period last year, 20 ballistic missile submarine launch tubes were deactivated, corresponding to four tubes on five Ohio-class submarines. Two of those submarines were in drydock for refueling and not part of the operational force.

In total, the United States has deactivated 56 strategic missile submarine launch tubes since the New START treaty went into effect in 2011, although the first reduction didn’t begin until after September 2016 – more than five years into the treaty.

The USS Louisiana (SSBN-743) returns to Kitsap Submarine Base in Washington on October 15, 2017 after a deterrent patrol in the Pacific Ocean. The submarine carried 20 Trident II missiles with an estimated 90 nuclear warheads.

Of the 280 submarine launch tubes, only 212 were counted as deployed with as many Trident II missiles loaded. The treaty counts a missile as deployed if it is in a launch tube regardless of whether the submarine is deployed at sea. The United States has declared that it will not deploy more than 240 missiles at any time. Assuming each deployed submarine carries a full missile load, the 212 deployed missiles correspond to 10 submarines fully loaded with a total of 200 missiles. The remaining 12 deployed missiles were onboard one or two submarines loading or offloading missiles at the time the count was made.

The data shows that the 212 deployed missiles carried a total of 945 warheads, or an average of 4 to 5 warheads per missile, corresponding to 70 percent of the 1,344 deployed warheads as of September 1, 2017 (the New START count was 1,393 deployed warheads, but 49 bombers counted as 49 weapons don’t actually carry warheads, leaving 1,344 actual warheads deployed). If fully loaded, the 240 deployable SLBMs could carry nearly 2,000 warheads.

The Navy has begun replacing the original Trident II D5 missile with an upgraded version known as Trident II D5LE (LE for life-extension). The upgraded version carries the new Mk6 guidance system and the enhanced W76-1/Mk4A warhead (or the high-yield W88-0/Mk5). In the near future, according to the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR), some of the missiles would be equipped with a low-yield version of the W76-1.

The Navy is developing a new fleet of 12 Columbia-class missile submarines to begin replacing the Ohio-class SSBNs in the late-2020s. The Trump NPR states that “at least” 12 will be built. Each Columbia-class SSBN, the first of which will deploy on deterrent patrol in 2031, will have 16 missile tubes for a total of 192, a reduction of one-third from the current number of SSBN tubes. Ten deployable boats will be able to carry 160 Trident II D5LE missiles with a maximum capacity of 1,280 warheads; normally they will likely carry about the same number of warheads as the current force, with an average of about 5 to 6 warheads per missile.

ICBMs

The New START data shows the United States now has just under 400 Minuteman III ICBMs in silos, down from 405 in March 2017. Normally the Air Force strides to have 400 deployed but one missile was undergoing maintenance.

A Minuteman III ICBM is removed from its silo at F.E. Warren AFB on June 2, 2017, the last to be offloaded to bring the United States into compliance with the New START treaty limits.

Although the number of deployed ICBMs had declined from 450 to 400, the total numbers of missiles and silos have not. The data shows the Air Force has the same number of missiles and silos as in March 2017 because 50 empty silos are “kept warm” and ready to load 50 non-deployed missiles if necessary. Reduction of deployed ICBMs started in 2016, five years after the New START was signed. And the actual ICBM force is the same size as when the treaty was signed.

The 399 deployed ICBMs carried 399 W78/Mk12A or W87/Mk21 warheads. Although normally loaded with only one warhead each, the Trump NPR confirms that “a portion of the ICBM force can be uploaded” if necessary. We estimate the ICBM force has the capacity to carry a maximum of 800 warheads.

An ICBM replacement program is underway to build a new ICBM (programmatically called Ground Based Strategic Deterrent) to begin replacing the Minuteman III from 2029. The new ICBM will have enhanced penetration and warhead fuzing capabilities.

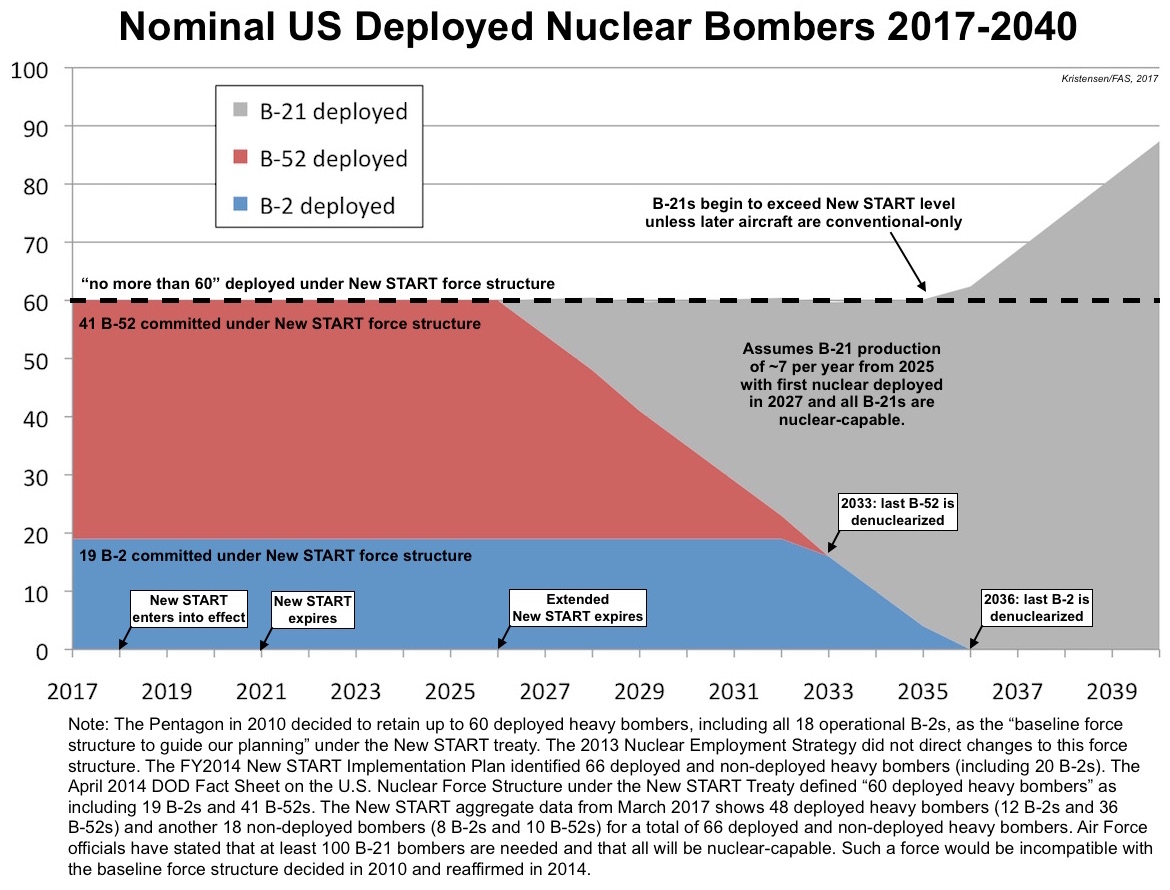

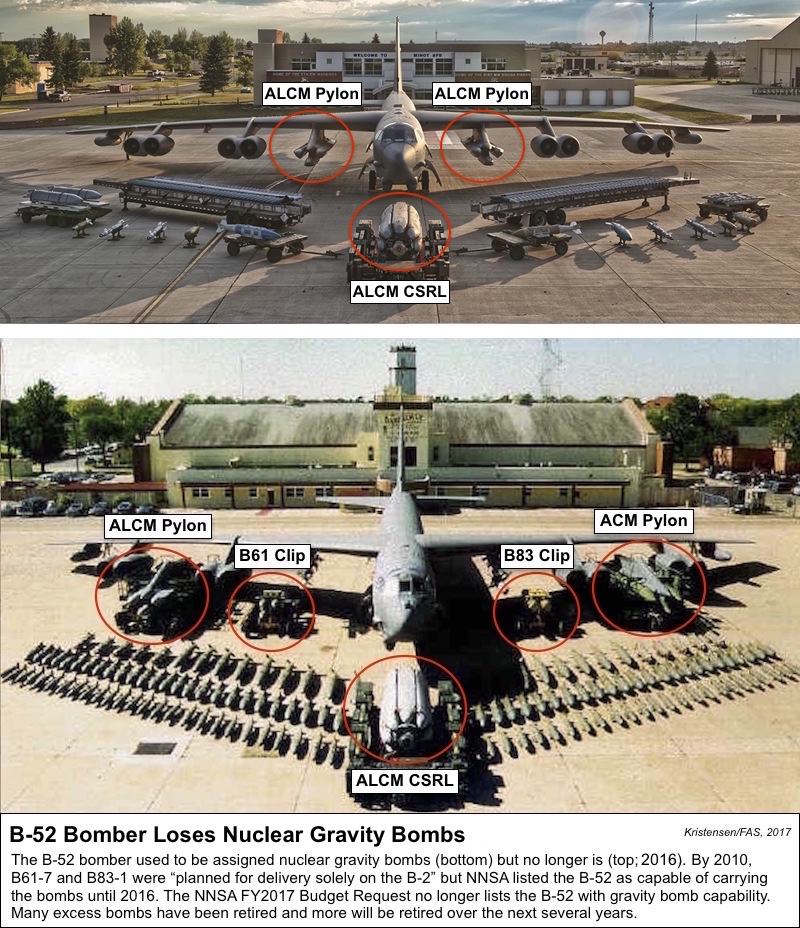

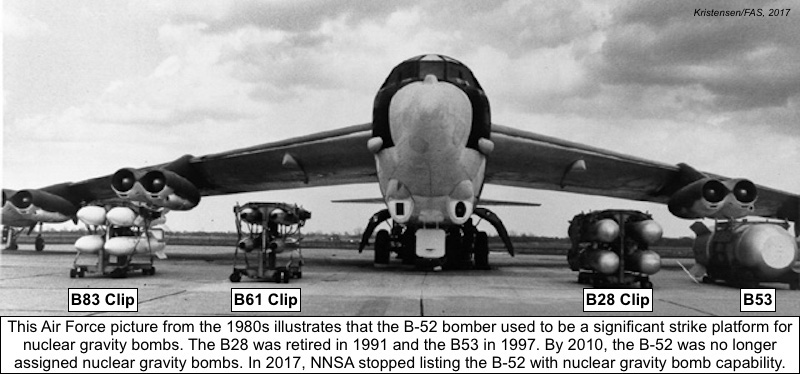

Heavy Bombers

The New START data shows the US Air Force has completed the denuclearization of excess nuclear bombers to 66 aircraft. This includes 20 B-2A stealth bombers for gravity bombs and 46 B-52H bombers for cruise missiles. Only 49 of the 66 bombers were counted as deployed as of September 1, 2017. Another 41 B-52Hs have been converted to non-nuclear armament such as the conventional long-range JASSM-ER cruise missile.

The New START treaty counts each of the 66 bombers as one weapon even though each B-2A can carry up to 16 bombs and each B-52H can carry up to 20 cruise missiles. We estimate there are nearly 1,000 bombs and cruise missiles available for the bombers, of which about 300 are deployed at two of the three bomber bases.

The first B-52H bomber was denuclearized under New START in September 2015. Denuclearization of excess nuclear bombers was completed in early 2017.

The bomber force was the first leg of the Triad to begin reductions under New START, starting with denuclearization of the (non-operational) B-52Gs and later excess B-52Hs. The first B-52H war denuclearized in September 2015 and the last of 41 in early 2017. Despite the denuclearization of excess aircraft, however, the actual number of bombers assigned nuclear strike missions under the strategic war plans is about the same today as in 2011.

A new heavy bomber known as the B-21 Raider is under development and planned to begin replacing nuclear and conventional bombers in the mid-2020s. The B-21 will be capable of carrying both the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb and the new LRSO nuclear cruise missile. The Air Force wants at least 100 B-21s but can only make 66 nuclear-capable unless it plans to exceed the size of the current nuclear bomber force.

Looking Ahead

With the completion of the force reductions under New START in preparation for the treaty entering into effect on February 5, 2018, the attention now shifts to what Russia and the United States will do to extend the treaty or replace it with a follow-up treaty. With its on-site inspections and ceilings on deployed and non-deployed strategic forces, extending New START treaty for another five years ought to be a no-brainer for the two countries; anything else would increase risks to strategic stability and international security. If the treaty is allowed to expire in 2021, there will be no – none! – limits on the number of strategic nuclear forces. Unfortunately, right now neither side appears to be doing anything except to blame the other side for creating problems. It is time for Russia and the United States to get out of the sandbox and behave like responsible states by agreeing to extend the New START treaty. February 5 – when the treaty enters into effect just 23 days from now – would be a great occasion for the two countries to announce their decision to extend the treaty.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NNSA’s New Nuclear Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) has published its long-awaited Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) for Fiscal Year 2018. The SSMP is NNSA’s 25-year strategic program of record.

I’ll leave it to others to analyze the infrastructure and fissile material portions and focus on the nuclear weapons life-extension programs (LEPs) and cost estimates.

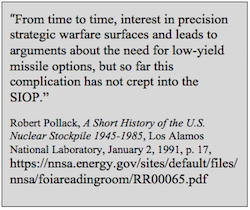

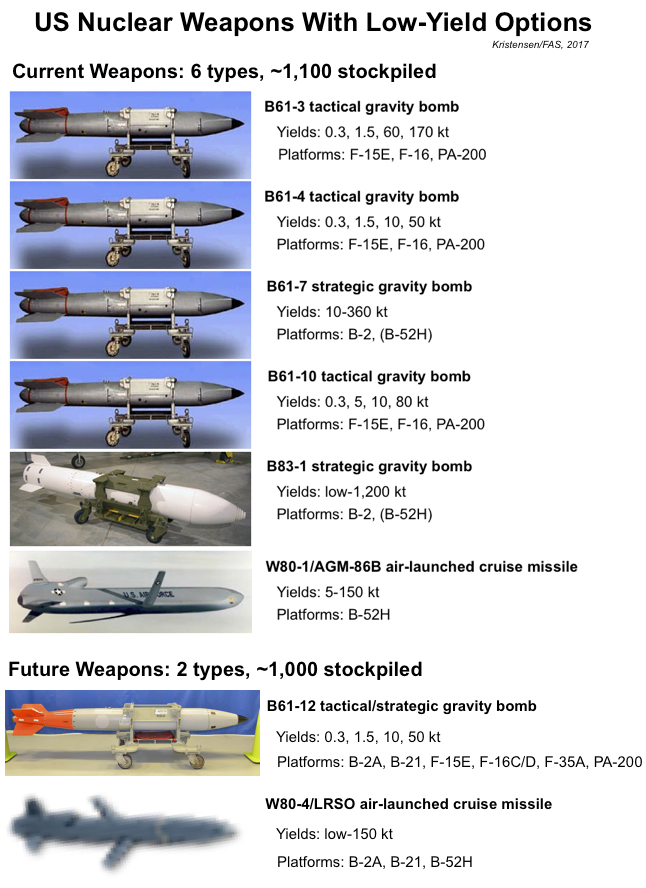

This year’s plan shows complex LEPs that are making progress but also getting more expensive (some even with funding gaps). There are some surprises (the retirement of the B61-10 tactical bomb), some sloppiness (the stockpile table has not been updated), and some questionable depictions (how to cut stockpile in half with no effect on average warhead age).

Nonetheless, the SSMP is a unique and important document and a service to the public discussion about the scope and management of the nuclear weapons arsenal and infrastructure. NNSA deserves credit for producing and publishing the SSMP. As such, it is a reminder that other nuclear-armed states should also publish factual overviews of their nuclear weapons programs to enable fact-based discussions and counter unsubstantiated rumors and worst-case suspicion.

Nuclear Nuts and Bolts

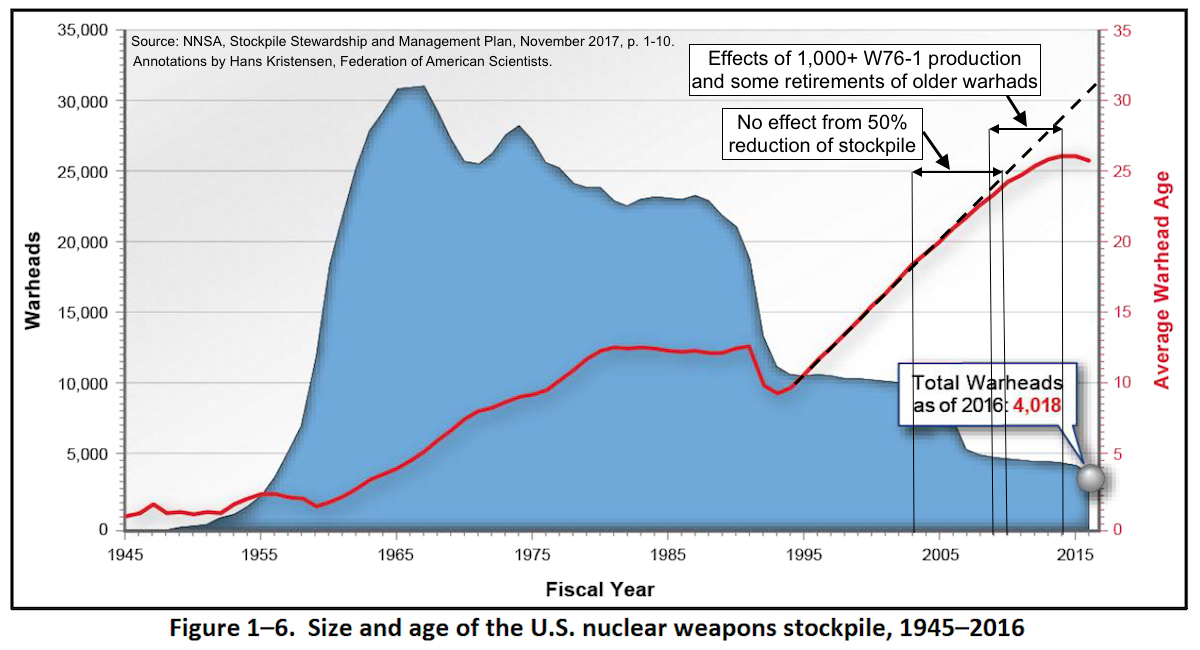

The 2017 SSMP does not update the nuclear stockpile number but continues to use the 4,018-warhead number (as of September 2016) declassified by the Obama administration in January 2017. The Trump administration has yet to declassify any nuclear stockpile numbers. The number now is estimated at around 4,000.

The report includes a graph that shows the average warhead age in the stockpile over the years. The graph shows the age continued to increase until about 2009, at which point it slowed until leveling out in 2014, presumably because of the significant production of W76-1 warheads (an LEP resets the warhead age to zero). In 2016, the average age began to drop, presumably because of the Obama administration’s 500-warhead cut in 2016 and continued production of the W76-1.

NNSA’s average warhead graph shows no effect from W Bush administration’s massive nuclear stockpile reduction. Click to view full size.

The near-continuous age increase through 2003-2007 is curious, however, because it shows hardly any visible effect from the massive stockpile reduction that occurred in those years. Why did a 50-percent reduction of the stockpile in 2003-2007 not have any effect on the average age of the remaining stockpiled warheads, when a 12-percent reduction in 2016 did? (The reductions in 1992-1994 also had a clear effect on the average warhead age.)

For that to be true, NNSA would have had to retire precisely the same portion of newer and older warheads of each warhead type, which seems odd.

The report reveals that the B61-10 tactical bomb was quietly retired in September 2016. The B61-10 has been in the inactive stockpile since 2006. The retirement is a surprise because the B61-10 is one of four B61 versions NNSA has listed to be consolidated into the B61-12. Once the B61-12 was produced and certified, so the argument was, the older versions would be retired.

The 2017 SSMP reveals that the B61-10 tactical bombs has been retired but continues to list the weapon as part of the B61-12 “consolidation” plan.

Despite the B61-10 retirement, officials have continued to include the weapon in the “consolidation” justification for the B61-12 during congressional hearings in 2017. In fact, the 2017 SSMP itself continues to include the B61-10 in its description of the B61-12 programs: “will consolidate four versions of the B61 into a single variant.”

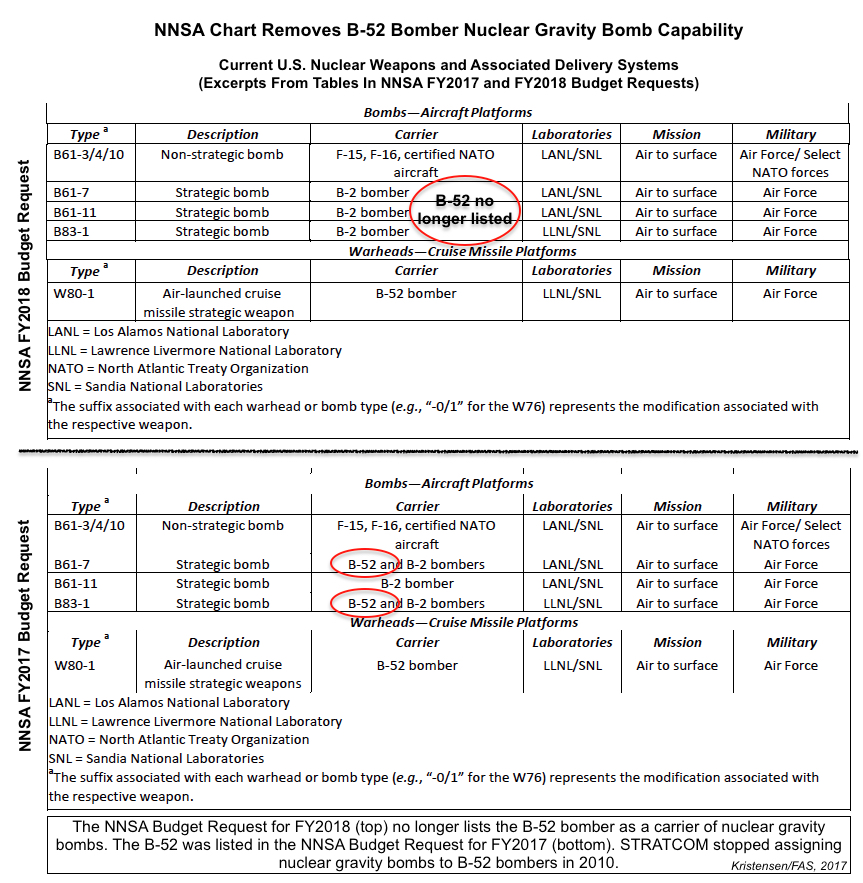

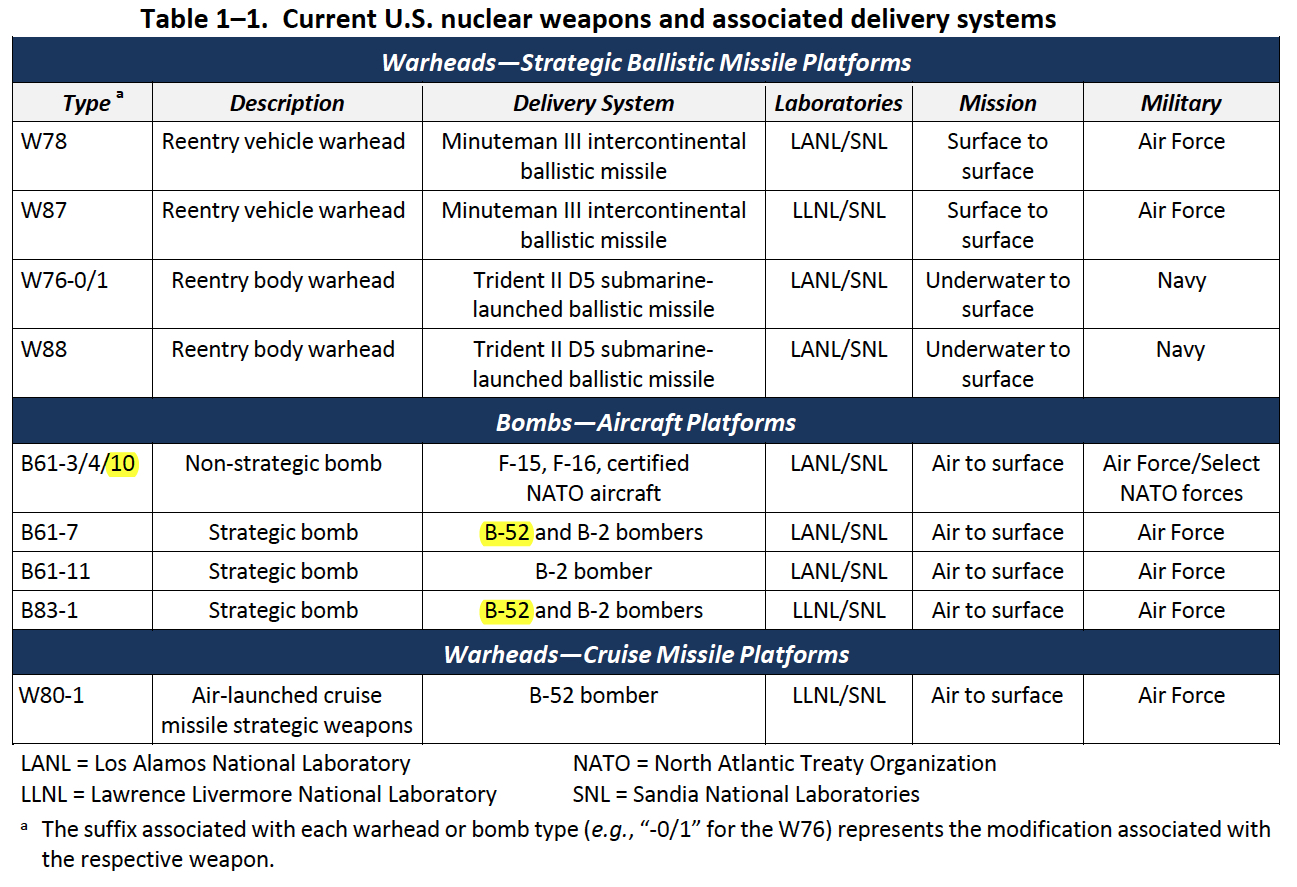

Despite the B61-10 retirement, the SSMP’s main table of the current nuclear weapons and associated delivery vehicles still lists the bomb (another table in the report does not list the B61-10).

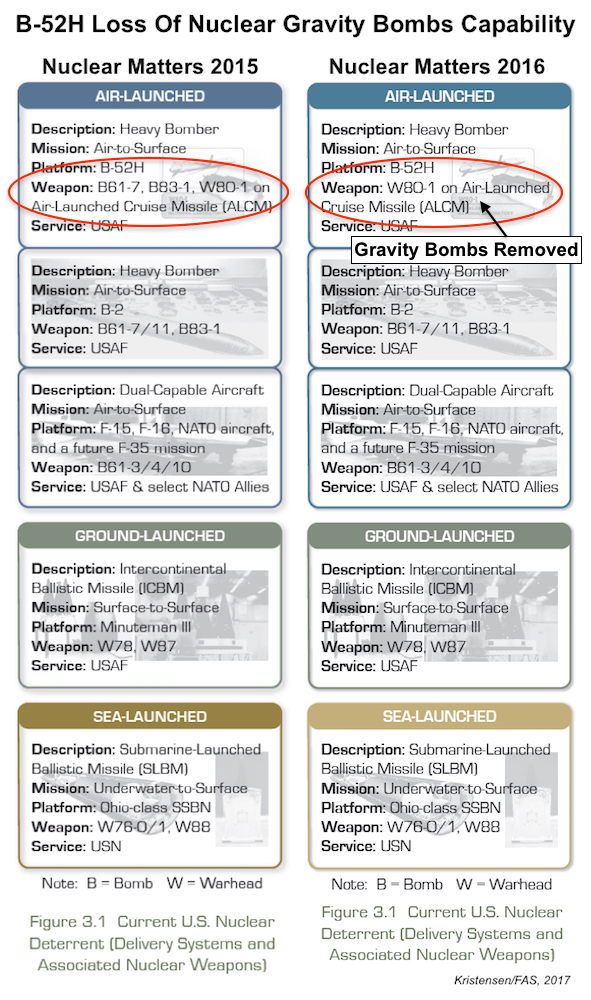

The SSMP report’s main table for the arsenal lists the B61-10 even though it has been retired, and gravity bombs for the B-52H even though it no longer caries them.

That table also lists the B-52H as carrying gravity bombs, even though other government documents no longer list gravity bombs assigned to the bomber. The authors appear to have done a sloppy job and simply copied the table from the 2016 SSMP without updating it.

The 2017 SSMP breaks down the extensive nuclear weapons modernization plan:

- W76-1 LEP: Complete production in 2019. With production of the W76-1/Mk4A having reached 80% and scheduled completion in 2019, Joint Flight Tests for the W76-0 has now stopped. That means it is official out of the stockpile and that all W76 war reserve warhead are now of the new W76-1 design.

- W87: Gas Transfer System (GTS) field refurbishment appears to have slipped halfway through 2019 with completion in 2024 instead of 2023.

- B61-12 LEP: First production unit in March 2020. Because program is moving ahead, the Nuclear Weapons Council in 2016 agreed to reduce surveillance tests for the B83 and B61-3, -, -7, and -10 bombs (the -10 has been retired).

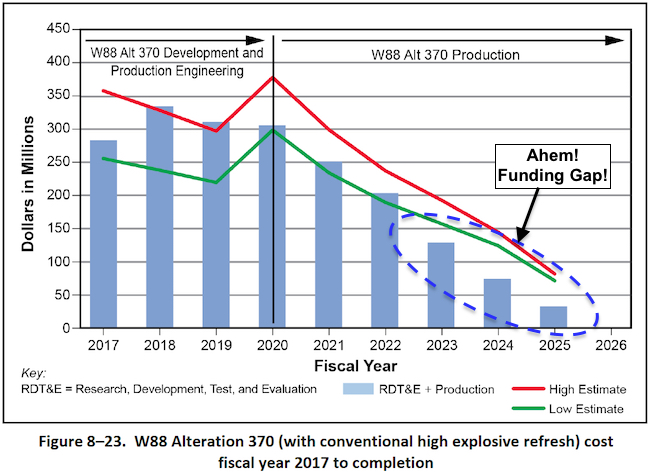

- W88 Alt 370: First production unit December 2019. Cost estimate has increased by 11 percent since 2015.

- W80-4 LEP: First production unit in 2025. Will use IHE of W80-1 but with new surety features. Unique program risks due to parallel integration with LRSO missile.

- IW1 (W78/W88): Studies and engineering to begin in 2020 and production to run from 2031 to 2041, a bit shorter than depicted in the 2016 SSMP. Will use W87 pit. ICBM first production unit in 2030 for use in Mk21 RV. SLBM first production unit in 2032 for use in Mk5 RB. PF-4 facility at Los Alamos in August 2016 “fabricated a W87 pit as part of the planned development series,” but next War Reserve pit is not scheduled until 2023.

- IW2 (W87/W88): ICBM first production unit in 2035. SLBM first production unit in 2036.

- IW3 (W76-1): ICBM first production unit in 2041. SLBM first production unit in 2042.

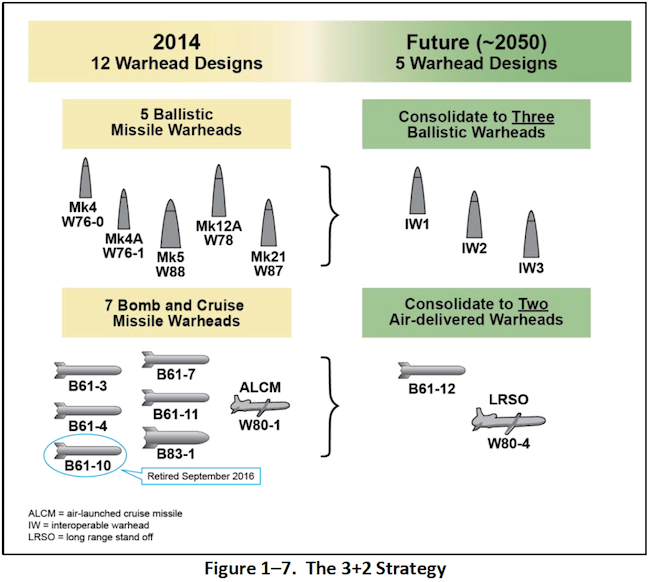

The 2017 SSMP also reaffirms the commitment to the “3+2” warhead strategy (which actually is a 6+2 strategy) even though the program is too expensive and potentially threatens the US nuclear testing moratorium. The “3” are so-called “interoperable warheads” intended for deployment on the ICBMs and SLBMs. The SSMP describes the Nuclear Weapons Council’s definition of an IW as “an interoperable NEP [Nuclear Explosive Package], with adaptable non-nuclear components on SLBMs and ICBMs.”

But even though “[f]inal designs of NEPs for the IW1, IW2, and IW3 warheads are yet to be determined,” the SSMP nonetheless confidently declares that the “3+2 Strategy preserves confidence in the stockpile’s operational reliability and effectiveness, while mitigating risk and uncertainty.” IW1 production is not expected until 2031, and I bet there are a couple of more design evaluations and decisions before NNSA can make any realistic assessment about reliability and effectiveness.

Moreover, I hear a lot of grumbling in the Navy and Air Force with concerns about introducing significantly modified warhead designs when the existing versions work just fine. Indeed, because the IW designs have not been tested in the assembled configuration envisioned, the 3+2 plan could introduce new uncertainties into the stockpile about warhead reliability and performance.

The Nuclear Posture Review is considering modifying a SLBM warhead to primary-only configuration to enable rapid low-yield strikes with ballistic missiles.

And The Money?

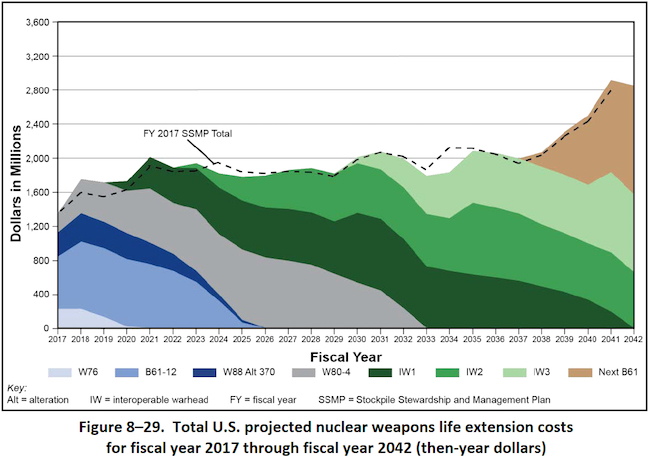

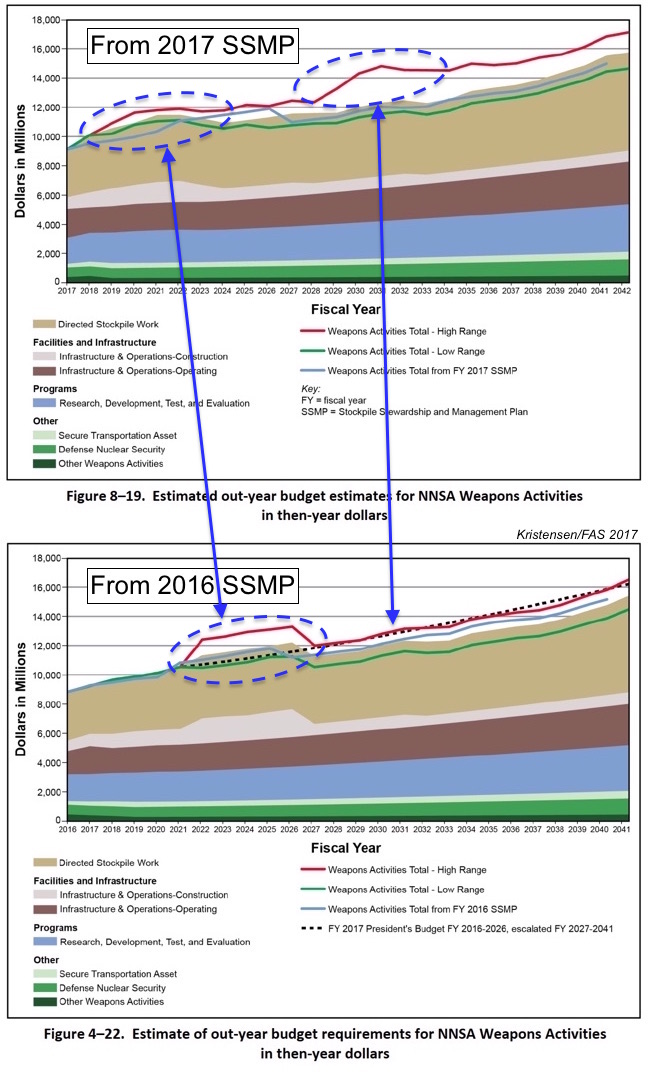

NNSA’s nuclear weapons budget has increased by 60 percent since 2010, and the agency is hoping for another $1 billion increase in 2018. In anticipation of the new NPR, the 2017 SSMP does not include budget numbers for 2019-2022 (the 2016 SSMP included these out-year numbers). And the detailed cost graph cuts off after 2018, unlike the 2016 SSMP graph that continued through 2021. But NNSA provides a new graph that plots expected weapons activities costs through 2042; there are significant changes compared with the graph included in the 2016 SSMP.

NNSA has restructure LEP spending plan so it moves “bow wave” up earlier, creates new bow wave later, and increases overall long-term costs.

It will take more time to analyze the data but a first impression is that NNSA has reorganized the projected costs so that the bow wave shown in the 2016 SSMP to appear in the 2020s now has been spread out and moved up so that it begins almost immediately and ends in the mid-2020s. Moreover, the graph shows a new high-range estimate cost emerging in the late-2020s and with significantly higher projections through 2042.

As part of that projection, all of NNSA’s LEPs high-end cost estimates appear to have increased, and there are still funding gaps toward the end of some of the programs, a budgeting problem that has previously been pointed out by GAO.

Some LEP programs appear to have insufficient funding.

And if you think the $10 billion B61-12 program is expensive, just check out the high-end cost estimate for the next B61 LEP (known as B61-13): a whopping $13.7 billion to $26.3 billion. Combined, in NNSA’s illustration, all the LEPs add up to $1.4 billion in 2017, increasing to nearly $2 billion per year in 2021-2037, and then ballooning to more than $2.8 billion per year by 2041.

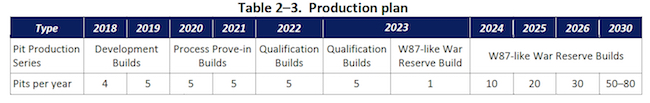

Production Infrastructure

The 2017 SSMP also includes some interesting information about the production complex capacity, not least the planned production of plutonium pits at Los Alamos National Laboratory. Production is scheduled to increase from four pits in 2018 to 10 in 2024, 20 in 2025, 30 in 2026, and build capacity to produce 50-80 pits per year by 2030.

Later in the SSMP (p. A-10), it turns out the requirement for the 10, 20, and 30 pits in 2024, 2025, and 2026, respectively, actually is to produce “not less than” those numbers. And the requirement for 2030 is no less than 80 pits.

All of this of course hinges on if and how NNSA can complete the construction of the expensive production facilities needed.

Testing

The 2017 SSMP concludes that “there is no current requirement to conduct an underground nuclear test to maintain certification of any nuclear warhead.” That is good news. The 1993 Presidential Decision Directive (PDD-15, “Stockpile Stewardship”) directed NNSA to maintain the capability to conduct a nuclear test within 24 to 36 months, just in case a test was needed in the future.

But the 2017 SSMP states that NNSA has changed its assessment of what that guidance means and says “the fundamental approach taken to achieve test readiness has also changed.” Unlike the 2016 SSMP, the 2017 SSMP introduces a much shorter readiness timeline for a simple test:

- 6 to 10 months for a simple test, with waivers and simplified processes;

- 24 to 36 months for a fully instrumented test to address stockpile needs with the existing stockpile;

- 60 months for a test to develop a new capability

This reassessment of the test readiness requirement appears to erode the US commitment to the testing moratorium. And it implies that NNSA is anticipating that future and more complex LEPs might potentially require “a simple test” with a nuclear yield. Such a test would be devastating to the international security environment and trigger a wave of nuclear tests in other nuclear-armed states.

For now, warhead development and surveillance rely on subcritical hydrodynamic tests, which are gradually becoming more complex and using more fissile material. The 2017 SSMP describes work is underway to develop an operational “enhanced capability” for subcritical experiments by the mid 2020s.

There were seven “integrated hydrodynamic experiments” conducted in 2016, including for what the SSMP describes as “stockpile options.” These options appear to be different from the known LEPs and stockpile maintenance efforts.

Conclusions and Recommendations

This is not even a Trump SSMP. The document describes the program of record: the maintenance and modernization plan initiated by the Obama administration. Yet in setting the policy framework for the 2017 SSMP, NNSA invokes president Trump’s January 2017 memorandum (NSPM-1) on rebuilding the armed forces to conduct a “new Nuclear Posture Review to ensure that the U.S. nuclear deterrent is modern, robust, flexible, resilient, ready, and appropriately tailored to deter 21st-century threats and reassure our allies.”

This formulation is different and much broader than the requirement listed in the 2016 SSMP, which required NNSA to “maintaining the safety, security, and effectiveness of the nuclear stockpile.”

From NSPM-1, the 2017 SSMP highlight an overall intension “to pursue peace through strength” and “give the President and the Secretary [of Defense] maximum strategic flexibility.”

“Maximum” is a dangerous requirement because it can be used to justify pursuit of all sorts of enhancements for the sake of improved capability. “Sufficient” is a much better word because it forces planners to think about how much is enough and balance this against other realities and requirements.

The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review expected at the turn of the year will mainly be focused on implementing the main elements of the Obama administration’s nuclear modernization program, but it is also considering new weapons and modified warheads.

And the tone describing the international environment will certainly darken. In describing the strategic context, the 2017 SSMP unfortunately makes the usual mistake of lumping Russia in among the countries that are “expanding” their nuclear arsenals. In terms of the total number of launchers and warheads, that is not the case.

NNSA’s nuclear warhead modernization plan forms part of a boarder nuclear modernization plan that is unaffordable as currently designed. The Congressional Budget Office recently presented options for how to reduce the costs. Several of those options include scaling back or canceling warhead programs, options that NNSA should actively consider.

Modifying requirements and scaling back ambitions can have considerable effects on what the Nation gets in return for its investments. Consider for example that the complex $10 billion B61-12 LEP only adds 20 years of life for 480 warheads, while the simpler $4 billion W76-1 LEP adds 30 years of life for 1,600 warheads.

The early retirement of the B61-10, moreover, raises obvious questions about why some of the other “consolidation” versions (B61-3, -4, and -7) cannot also be retired early. Moreover, many B83s currently maintained in the stockpile could probably be retired early as well and dismantled.

On dismantlement, the 2017 SSMP is a clear step back. The requirement in the 2016 SSMP to accelerate dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 has been deleted from the 2017 update. And while funding for dismantlement in the 2016 SSMP was increased to two percent of the directed stockpile budget, the 2017 report reduces the budget for warhead dismantlement and disposition to only one percent. Completion of dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 is scheduled for September 2022 – one year later than the deadline listed in the 2016 SSMP. But the 2017 SSMP doesn’t even address what the plan is for dismantling the backlog of the roughly 1,000 warheads that have been retired after 2009.

While dismantlement is not a priority for NNSA or defense planners who are focused on modernization, it is an important and powerful message to the international community that the United States is not only modernizing but actually also scrapping nuclear weapons. After all, with no new arms control treaty to replace New START (not even negotiations), an INF treaty that is close to collapsing, rejection of the Ban Treaty, and rampant modernization programs underway to extend the nuclear era through the rest of this century, what else do we (and the other P5s) have to show at the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty review conference in 2020?

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

CBO Study Presents Options For A More Affordable Nuclear Modernization Plan

A new report by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the current plan to sustain and modernize US nuclear forces will cost $1.2 trillion over the next 30 years – or $41.4 billion per year.

A new report by the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the current plan to sustain and modernize US nuclear forces will cost $1.2 trillion over the next 30 years – or $41.4 billion per year.

A study by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in 2014 projected the cost would be “over $1 trillion” over 30 years.

CBO projected in February 2017 that US nuclear forces will cost $400 billion over the 10-year period 2017 to 2026, or $40 billion per year. The projection was a 15% increase over the $345 billion estimate from January 2015 for the period 2015 to 2024.

Although the cost of US nuclear forces is limited compared with the size total defense budget, the cost will increase significantly in the next decade and compete with other non-nuclear defense priorities that also need funding. As a result, the current nuclear modernization plan is unsustainable.

The CBO report therefore presents nine options for changing the nuclear force structure and timing that the Trump administration and Congress could consider for reducing the cost of nuclear forces.

Repeated Warnings

Over the past several years, government officials have warned repeatedly that the current nuclear weapons modernization plan is unsustainable.

“There is a big bow wave out in the ‘20s,” the Air Force’s top program planner acknowledged in 2014. Together with the other nuclear modernization programs of the navy and the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), the Pentagon’s top acquisition official warned later that year: “We’ve got a big affordability problem out there with those programs.” And in 2015 he said: “We do have a problem in the budget, and that problem is called the recapitalization of the triad … There is no way I can see that we can sustain the force structure and have a reasonable modernization program unless we get more money in the defense budget.”

As Brian McKeon, then principal deputy under secretary of defense for policy, stated in October 2015: “We’re looking at that big bow wave and wondering how the heck we’re going to pay for it, and probably thanking our stars we won’t be here to have to answer the question.”

His warning was echoed in 2016 by Jamie Morin, then DOD’s director of cost assessment and program evaluation, who concluded that, “unless the department was willing to divest the submarine leg of the triad – which we’re not – there’s no way to pay for [nuclear] modernization within the budget.”

“All Or Nothing” Arguments

Despite these warnings, which are now being further substantiated by the CBO report, military leaders, lawmakers, and defense contractors have been relentlessly pushing the excessive “all of the above” modernization program under a false premise of a choice between modernizing or not or having a nuclear deterrent or not. These “all or nothing” arguments set up roadblocks to deal with the real issue.

One “all or nothing” argument is that the United States needs to modernize, otherwise the nuclear deterrent will atrophy. But that’s not the choice. No one is arguing that the United States should not modernize its nuclear forces. The question is how much it can afford to modernize and for what purpose.

Another cost related “all or nothing” argument is that nuclear weapons only cost 4-5 percent of the defense budget. Surely, the United States can afford that. But that’s not the issue. The question is how those 4-5 percent compete with all the other defense needs the taxpayers also have to pay for.

And then there’s the “all or nothing” argument that the United States needs nuclear weapons, otherwise world wars will happen again. But that’s not the choice either. No one is arguing that the United States should unilaterally scrap its nuclear weapons. The question is now how the nuclear posture should be structured to best serve US national and international requirements in the decades ahead.

If the White House, DOD, and Congress don’t make the right choices about priorities now at the outset of the modernization programs, future defense budgets will make the decisions for them. Those decisions will be much harsher: delaying, scaling back, or outright cancelling programs. The effect will be a nuclear posture in turmoil where the budget axe determines the structure rather than carefully thought out planning.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The timing of report is impeccable (and FAS is honored to be referenced several times); only a couple of months before the Trump administration is expected to complete its Nuclear Posture Review.

That review is expected to carry forward the bulk of the Obama administration’s nuclear modernization plan, possibly sprinkled with a few additions such as a new sea-launched cruise missile and a low-yield warhead option for one of the navy’s ballistic missile warheads.

But that modernization plan is unsustainable.

It would be irresponsible if the NPR reaffirms the current modernization program without adjustments to mitigate the funding threats raised by the CBO report.

The CBO report includes plenty of options that the White House and Congress must consider for how to adjust the nuclear posture and the modernization plan to make it sustainable and still maintain a highly capable and survivable nuclear deterrent.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO Nuclear Exercise Underway With Czech and Polish Participation

Image: https://www.facebook.com/lowapproach/posts/1468961693225121. Hat tip: Roel Stynen.

By Hans M. Kristensen

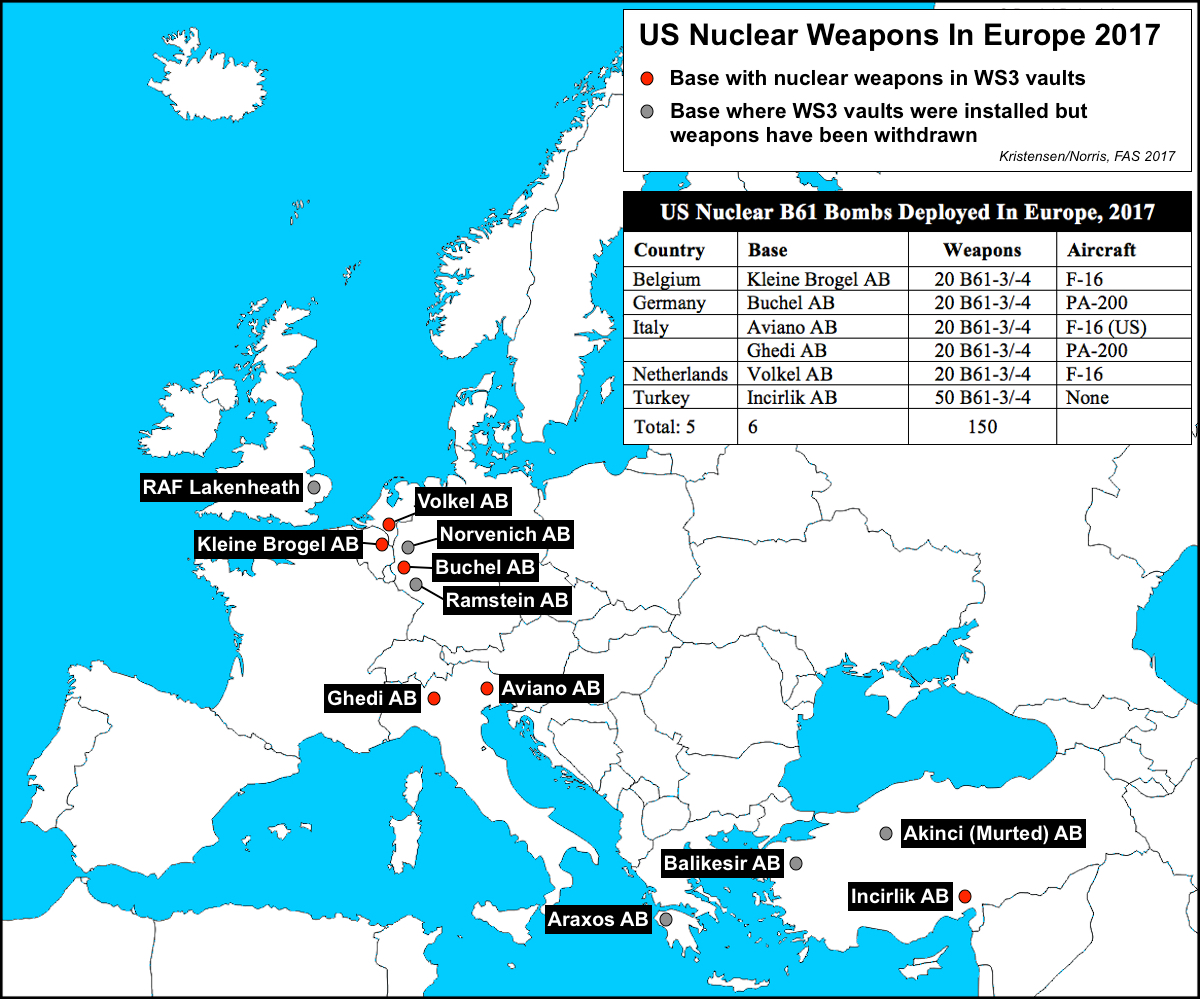

NATO reportedly has quietly started its annual Steadfast Noon nuclear strike exercise in Europe.

This is the exercise that practices NATO’s nuclear strike mission with dual-capable aircraft (DCA) and the B61 tactical nuclear bombs the US deploys in Europe.

In addition to nuclear-capable aircraft from Belgium, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, local spotters have also seen Czech Gripens and Polish F-16s. The United States will likely also participate with either F-16s from Aviano AB in Italy or F-15Es from RAF Lakenheath in England.

The non-nuclear aircraft from Czech Republic and Poland are participating under NATO’s so-called SNOWCAT (Support of Nuclear Operations With Conventional Air Tactics) program, which is used to enable military assets from non-nuclear countries to support the nuclear strike mission without being formally part of it. Polish F-16s have participated several times before, including in the Steadfast Noon exercise held at Ghedi AB in Italy in 2010.

This year’s Steadfast Noon exercise is taking place at two locations: Kleine Brogel Air Base in Belgium and Buchel Air Base in Germany. Both bases store an estimated 20 US B61 nuclear bombs for use by the national air forces. This is the second year in a row that the exercise has been spread across two bases in two countries. Last year’s exercise was held at Kleine Brogel AB (Belgium) and Volkel AB (Netherlands). The multi-base Steadfast Noon exercises are often coinciding with or preceding/following other exercises such as Decisive North and Cold Igloo.

There are currently an estimated 150 B61 bombs deployed at six bases in five European countries (see figure below).

Weapons were previously also deployed at RAF Lakenheath but withdrawn sometime between 2004 and 2008. Weapons were also withdrawn from Araxos AB (Greece) in 2001. Consolidation (but not complete withdrawal) also happened in Germany and Turkey (for these earlier changes, see my report from 2005).

In addition to the countries with nuclear-capable aircraft – Belgium, Germany Italy, Netherlands, Turkey (note that the status of Turkey’s nuclear role is unclear, but it’s F-16s are still nuclear-capable), and the United States, there will likely be participation from other NATO countries under the SNOWCAT program.

NATO is adjusting its nuclear posture in reaction to the new adversarial relationship with Russia. The Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review is expected to reaffirm the continued deployment and modernization of US non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe. But there is a push from hardliners inside NATO to increase the readiness and planning for the non-strategic aircraft. Others say it is not necessary. Last month several B-52 bombers forward-deployed to Europe in support of NATO and many see that as sufficient signaling at the nuclear level. Overall, moreover, NATO’s reaction to Russia is focused on providing non-nuclear defense to Europe.

In a broader context, the nuclear exercise has not been officially announced and NATO is very tight-lipped about it because of the political sensitivity of this mission in mainly western NATO countries. The secrecy of the exercise is interesting because NATO only a few weeks ago complained that Russia was not being transparent about its Zapad exercise. Seems like both sides could do better.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

‘Small Hands’ Don’t Like Small Nuclear Arsenals

By Hans M. Kristensen

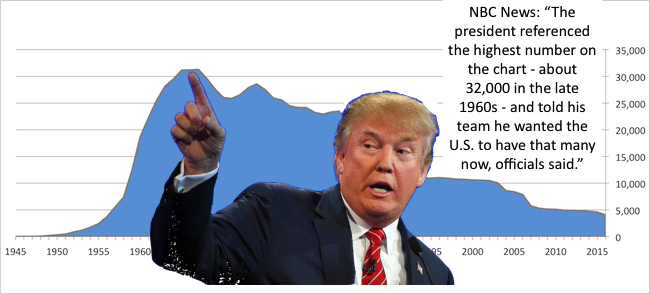

According to an NBC News report, President Donald Trump said during a meeting at the Pentagon on July 20 that “he wanted what amounted to a nearly tenfold increase in the U.S. nuclear arsenal,” according to three officials who were in the room.

Trump’s statement came in response to a chart shown during the meeting on the history of the U.S. and Russia’s nuclear capabilities. Trump reportedly referenced the highest number on the chart – about 32,000 in the late 1960s – and “told his team he wanted the U.S. to have that many now, officials said.”

It is often a mystery how Trump reaches his conclusions and his statement about increasing the arsenal is clearly not based on rational reasoning or factual information. Presidential advisors at the meeting reportedly explained why an expansion was not feasible (that must have been an embarrassing moment) and officials said his comments “raised questions about his familiarity with the nuclear posture and other issues.”

Despite Trump’s fantasies, the United States is unlikely to increase its nuclear weapons stockpile. There are currently about 4,000 nuclear warheads in the Pentagon’s stockpile, of which roughly 1,800 are deployed on ballistic missiles and at bomber and fighter bases. The military says it has too many and could meet national and international commitments with up to one-third fewer deployed weapons. And the trend is that the stockpile will continue to decline over the next decade because of changes being made to the force structure as part of the current modernization program.

Fun facts added: The biggest stockpile increase in one year was 1959-1960 when the United States added 6,340 warheads. During the 72 years since the first production of nuclear weapons in 1945, the average number of nuclear weapons added to the U.S. stockpile per year is 56. At that rate, it would take 487 years to increase the stockpile to the peak of 31,255 warheads in 1967.

Yet Trump’s repeated statements demonstrate a predisposition toward more nuclear weapons. The big question is to what extent that will influence the Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) currently under preparation. Trump might try to slow the reduction and force the military to hang on to excess warheads even though they don’t need them or want them.

More likely is that Trump with the NPR will try to further increase the capabilities of the remaining weapon types. Again, enhancements are already being added as part of the ongoing modernization programs, but there are people involved in the NPR process that are advocating doing more. The White House apparently is in favor of researching and developing a ground-launched missile that, if tested and deployed, would violate the INF treaty (this is a Cold War tit-for-tat response to Russia’s violation of the treaty).

Despite current challenges to the international nuclear weapons arms control efforts, it is essential that the Trump administration reaffirms long-standing U.S. nuclear policy to reduce nuclear arsenals and work toward the eventual elimination of nuclear weapons. Doing otherwise might satisfy defense hawks with no gain for national security, but it would also embolden other nuclear-armed states to further increase their arsenals to the detriment of the security of the United States and its allies.

Background:

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data: Russia Slashes Deployed Warheads, US Reaches Limits

By Hans M. Kristensen

The United States has now reached the limits for all three weapons categories under the New START treaty.

The latest data published by the State Department shows that the United States for the first time since the treaty entered into force in 2011 has reached the limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. The 660 deployed launchers are also below the treaty limit of 700 and the 1,393 deployed warheads is well below the limit of 1,550. As such, the United States is now technically in compliance with the treaty.

The latest US reductions are the result of denuclearization of bombers and reduction of launch tubes on the Ohio-class submarines.

The data shows that Russia has reduced its deployed strategic warheads by 235 in the past 12 months and is now only 11 warheads above the New START treaty limit of 1,550 warheads to be achieved by February 2018. Russia is already below the treaty limit on deployed launchers as well as deployed and non-deployed launchers.

Russia’s increase in deployed strategic warheads between 2013 and 2016 triggered widespread claims by defense hawks that Kremlin was building up its nuclear forces. As I previously pointed out, that was wrong and the result of temporary fluctuations in the Russian force structure. Russia is modernizing, not increasing, its nuclear arsenal.

The Bigger Picture

The latest data shows that the United States has a significant advantage over Russia in deployed strategic launchers; 660 versus 505. The 155-launcher disparity means Russia emphasizes multiple warhead loading on its ICBMs while the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carrying only a single warhead each. A future follow-on treaty will need to address this disparity, which is unhealthy for long-term strategic stability.

Although the United States and Russia are now at, near, or below the limits of the New START treaty, the warheads counted by the treaty only constitute a small fraction of the two countries’ total warhead inventories.

We estimate that Russia has a military stockpile of 4,300 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 7,000 warheads. For its part, we estimate the United States has a military stockpile of 4,000 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 6,800 warheads.

These arsenals are vastly in excess of the nuclear force levels maintained by other nuclear-armed states and constitute more than 90% of the world’s combined inventory of nearly 15,000 nuclear warheads.

Moreover, the New START treaty does not limit the 2,350 non-strategic nuclear warheads we estimate that Russia and the United States have in their arsenals combined. Both sides are modernizing their non-strategic nuclear forces.

Finally, the New START treaty expires in 2021 unless extended for another five years. The Trump administration has previously indicated opposition to extending the treaty, although recent discussions with Russia may seek to change that. A follow-on treaty seems unlikely given the current political climate but could easily be achieved by reducing the excess nuclear forces of Russia and the United States.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NASIC Removes Russian INF-Violating Missile From Report

By Hans M. Kristensen

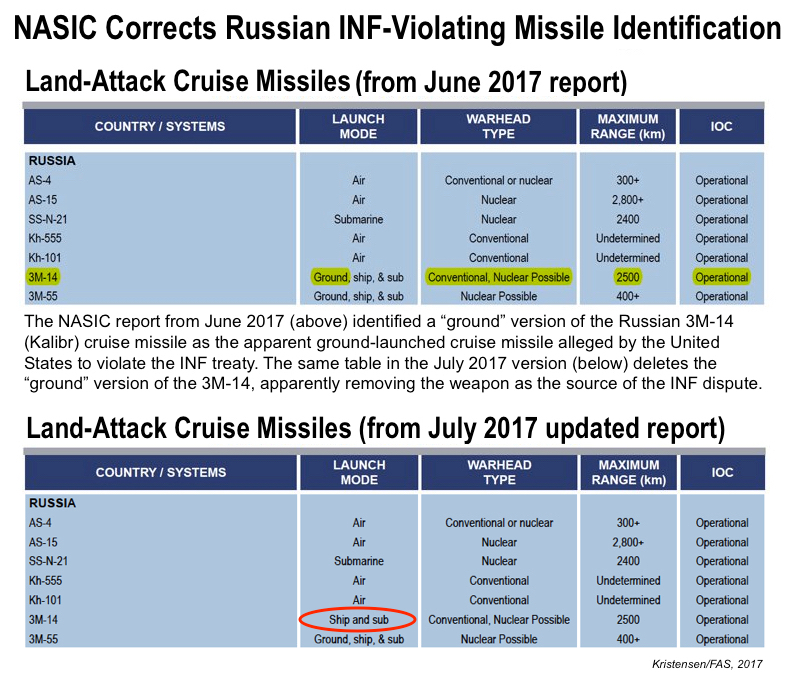

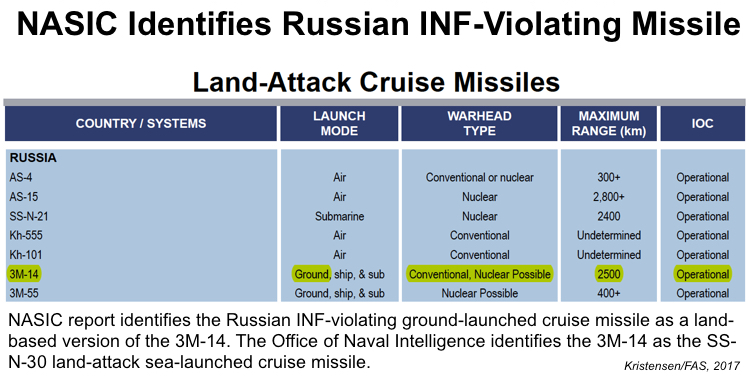

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has quietly published a corrected report on the world’s Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats that deletes a previously identified Russian ground-launched cruise missile.

The earlier version, published on June 26, 2017, identified a “ground” version of the 3M-14 land-attack cruise missile that appeared to identify the ground-launched cruise missile the United States has accused Russia of testing and deploying in violation of the 1987 INF Treaty.

The corrected version, available on the NASIC web site, no longer lists a “ground” version of the 3M-14 (popularly referred to as Kalibr) but only ship- and submarine-launched versions of the missile.

Apart from correcting the spelling of the North Korean Bukkeukseong-2 medium-range ballistic missile and downgrading the operational status of the Iranian Shahab-3 medium-range ballistic missile from deployed with “fewer than 50” launchers to “undetermined,” the deletion of the “ground” version of the Russian 3M-14 appears to be the only correction in the new NASIC report. (Curiously, the report still doesn’t identify the Russian Kh-102 air-launched cruise missile). Other than these changes buried deep in the report, however, there are no external markings on the new version to indicate that it has been changed (the URL identifies the new report date as July 21, 2017).

The older version of the NASIC report has been deleted from the NASIC web site, but a copy can be found here.

Implications and Recommendations

The deletion of the 3M-14 as the apparent INF-violating missile from the NASIC report is noteworthy, but it doesn’t actually change much. In essence, it returns the public INF debate to square one where it was three months ago. The correction even helps clear up confusion about the origins and status of the alleged Russian INF violation (several of us in the GNO community have been trying to crosscheck and cross-reference missile designations).

The United States has refused to publicly identify the INF-violating ground-launched cruise missile, apparently to protect intelligence sources. Instead, government sources have described what the missile is not (see here for previous statements). Although NASIC took the time to correct the error, it missed the opportunity to identify the actual INF-violating ground-launched cruise missile.

The correction refocuses the attention back on what I’ve heard all along: That the Russian INF-violating missile is thought to be a modification of the ground-launched SSC-7, a short-range cruise missile used on the Iskander system. But U.S. intelligence officials are adamant that the INF-violating missile is not the Iskander but a state-of-the-art missile. The new missile is known in the U.S. intelligence community as the SSC-8. The launcher itself apparently is physically different from the one used for the SSC-7. I co-authored a paper about this with the Deep Cuts Commission in April.

Apparently one battalion is operational and a second is fitting out, potentially embedded with Islander battalions starting in central Russia, and deployments are expected eventually in all four Russian military districts. So far, however, according to U.S. officials, the SSC-8 does not appear to give Russia any military advantage in Europe. And the U.S. military already has the military capability to counter the SSC-8 with sea- and air-launched cruise missiles and other means.

The U.S. refusal to identify the missile has given the Russian government the public space to “play ignorant” and claim it doesn’t know what the U.S. government is talking about. Similarly, the secrecy has made it difficult for allied governments to verify the claim and privately and publicly assist the United States with putting pressure on Russia to return to treaty compliance. That, in turn, has allowed hardliners in the U.S. Congress to propose that the United States should also develop it’s own ground-launched cruise missile (something the U.S. military does not believe is necessary).

Rather than making a bad situation worse, in order to sustain and increase pressure on Russia to return to INF compliance, the United States must reinforce its own commitment to the treaty by rejecting any Cold War proposal to mimic Russia’s bad behavior by developing a U.S. ground-launched cruise missile and instead focus potential military responses on existing forces already widely available, remove public ambiguity by identifying the Russia missile and disclose the information it has shared with Russia (if it can tell the Kremlin, then it can also tell the rest of the world), increase intelligence sharing with allies to improve their ability to work the issue with Russia directly, and pursue the matter directly with Russia in the Special Versification Commission of the INF treaty.

Background information:

- NASIC (corrected) report on Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats

- NASIC (previous) report on Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threats

- FAS review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

- Deep Cuts Commission: Preserving the INF Treaty

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows US Implementation, Questions About Bomber Force

By Hans M. Kristensen

While defense hawks try to block funding for implementing the US-Russian New START treaty, the US military is making rapid process toward meeting the treaty limits by February 2018.

The latest full declassified aggregate data for the US force structure under New START shows that both the ICBMs and bombers appear to have reached the force level planned and more than two-thirds of the SSBN fleet has been converted as well.

But the implementation also raises questions about what the plan is for the future bomber force structure. Depending on how many new B-21 bombers the Air Force will deploy how soon and how many will be nuclear-capable, the Air Force might have to withdraw the B-52 from the nuclear mission by the early 2030s.

This also raises questions about the need to deploy the new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (RLSO) on the B-52 bombers. The new B-21 is intended to take over the nuclear air-launched cruise missile mission. The B-2 appears to have been eliminated as a future LRSO platform.

The ICBM Force

The Minuteman III ICBM force is listed with 405 deployed missiles, a reduction of 8 since September 2016. Since this count was reported, the Air Force has removed the last 5 ICBMs from their silos, leaving 400 deployed ICBMs, the goal identified in the New START Implementation report.

A Minuteman III ICBM is removed from its silo at Malmstrom AFB on June 2, 2017, as part of US implementation of the New START treaty.

The ICBM reduction is spread evenly across the three missile wings (133 ICBMs per wing), but other detailed New START data obtained from State Department shows that Malmstrom AFB was the first of the three wings to reach the 133 number.

Although the number of deployed ICBMs has been reduced, the total number of deployed and non-deployed ICBMs has not gone down but remains at 454 as in September 2016. The reason is that the reduction of 50 deployed ICBMs since 2011 requires the 50 empty silos to be kept “warm” and ready for redeployments if necessary. There is no strategic need to do so.

All deployed Minuteman III ICBMs have been “de-MIRVed” and currently carry one warhead each. Yet more than half of the force (those with the W78/Mk12A reentry vehicle) can still carry up to three warheads; the additional warheads are in storage. The remaining W87/Mk21-equipped ICBMs can only carry one warhead each. However, all of the next-generation ICBMs (currently known as Ground Based Strategic Deterrent, GBSD) will be MIRVable.

The SSBN Force

The New START data shows that US SSBNs carried a total of 220 SLBMs at the time of the count. That’s 11 missiles more than the previous count in September 2016. A total of 80 launchers were empty (three SSBNs in drydock and one in missile handling) for a total of 300 missile launch tubes.

Nine of the 14 SSBNs appear to have been converted to 20 missile launchers, a reduction of 4 missile launchers per boat to meet the New START overall limit of 700 deployed launchers. As of March 2017, the navy still had to inactivate a total of 20 launch tubes on five SSBNs to reach the goal of 280 deployed and non-deployed SLBM launchers by February 2018. Of those, no more than 240 will be deployed at any time.

The USS Alaska (SSBN-732) that returned to Kings Bay in mid-June following its 100th deterrent patrol since 1986, probably carried 20 Trident II SLBMs loaded with 88 nuclear W76-1 and W88 warheads.

Additional information obtained from State Department shows where the changes have been made (see table below). The Atlantic fleet has almost completed the conversion to 20 launchers per SSBN (one sub in refueling overhaul is probably being converted), while the Pacific fleet still has three SSBNs with 24 missiles, but two of them were empty at the time of the count (one of them in refueling overhaul) and a third was only partially loaded (probably undergoing missile handling).

The full declassified aggregate data also shows that there were a total of 958 warheads onboard deployed SLBMs as of March 2017, or nearly two-thirds of the total warhead number permitted by New START by February 2018. The United States does not need to make additional reductions in deployed warheads but could in fact increase the number of warheads deployed on SSBNs by another 139 warheads if it decided to do so.

The Heavy Bomber Force

The reduction of nuclear bombers appears to be complete. The Air Force has not yet declared so in public, but the data shows the number of deployed and non-deployed nuclear bombers are down to 66 – the same number required by the New START Implementation report. That is a reduction of 45 bombers compared with the inventory of 111 nuclear-capable bombers declared back in September 2011 (another 39 retired bombers were also declared as nuclear at the time but did not have an actual nuclear mission).

B-1, B-2 and B-52 bombers at RAF Fairfield in England on June 12, 2017. B-1 is equipped with conventional JASSM-ER. The B-2 and B-52 are nuclear-capable and part of the 66 nuclear bomber force planned under the New START treaty.

At 48, the number of deployed nuclear bombers is now 12 aircraft below the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” the Pentagon set in 2010 as the New START force level. That development is despite the B-52s having lost the nuclear gravity bomb mission and is now only delivering ALCMs; only the B-2 today has a strategic gravity bomb mission. The willingness to drop below the 60 indicates that there is excess capacity in the nuclear bomber force.

Moreover, with a New START force level of 66 deployed and non-deployed nuclear bombers (20 B-2s and 46 B-52s), an important question is how many of the new B-21 bombers will be nuclear-capable. The Air Force wants “a minimum of 100” B-21s in total and Lt Gen Jack Weinstein, the Air Force’s deputy chief of staff for strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, reportedly told Flight Global that the entire fleet of B-21s will be dual-capable.

The Air Force wants more than 100 B-21 bombers and officials say all will be nuclear-capable. That would violate the force level of “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” planned under New START.

If that were the case, then it would raise questions about US long-term nuclear forces plans, challenge nuclear arms control, and potentially influence strategic stability. Assuming delivery of about seven B-21s per year starting in 2025 and the first nuclear-capable aircraft two years later, the US would by 2028 begin to exceed the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” pledged in 2010 and reaffirmed in April 2014, unless it begins to denuclearize B-52 and B-2 bombers as the B-21 enters the force. Although that would be two years after a possible extended treaty had expired in 2026 leaving the United States free of legal constraints, the Pentagon currently uses the New START force level as long-term guidance for the force structure. So a decision to go beyond “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” would be a significant change.

To avoid exceeding the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force level, it would be necessary to begin reducing the number of B-52s in the nuclear mission pretty much as soon as the B-21 begins to enter the force. By the mid-2030s, all the B-52s would have to be out of the nuclear mission, and the B-2 would have to begin withdrawing from the nuclear mission as well. By 2037, there would only be room for B-21s in the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force level. Any B-21 produced after that year would have to be conventional-only (see graph below). A slower B-21 production would obviously affect this projection.

How the nuclear bomber force structure evolves also has implications for development and deployment of the new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO). The Air Force has previously stated that the LRSO would be made compatible with all three nuclear bombers: B-2, B-21, and B-52. In testimony before the U.S. Congress in July 2016, Air Force Global Strike Command listed all three bombers as part of the LRSO program, but in its June 2017 testimony the command only said the LRSO “will be compatible with B-52 and B-21 platforms.” Apparently, the B-2 has been removed from the LRSO program. [Update 7/26/2017: Although AFGSC chief Gen Rand omitted the B-2 from his 2017 congressional testimonies, AFGSC PA told me the “LRSO will be compatible with B-2, B-52, and B-21″ but also reminded that the Trump administration’s NPR “will guide modernization efforts, including the future of our bombers.”]

But the B-52 is still intended to be made compatible with the LRSO. By the time the new missile becomes operation in 2030, however, half of the B-52s that are currently nuclear-capable might already have been denuclearized to make room for the B-21 under the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force level (see above). The remaining nuclear B-52s would be gone from the force only a few years later, which appears to make the fielding of the LRSO on the B-52 a waste of money and effort.

The Air Force should clarify its plans for the bomber force, whether it intends to keep the “up to 60 deployed heavy bombers” force structure, how many B-21s will be nuclear-capable, and whether the LRSO needs to be made compatible with the B-52 at all.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

Click on image to download copy of report. Note: NASIC later published a corrected version, available here

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB has updated and published its periodic Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. The new report updates the previous version from 2013.

At a time when public government intelligence resources are being curtailed, the NASIC report provides a rare and invaluable official resource for monitoring and analyzing the status of ballistic and cruise missiles around the world.

Having said that, the report obviously comes with the caveat that it does not include descriptions of US, British, French, and most Israeli ballistic and cruise missile forces. As such, the report portrays the international “threat” situation as entirely one-sided as if the US and its allies were innocent bystanders, so it will undoubtedly provide welcoming fuel for those who argue for increasing US defense spending and buying new weapons.

Also, the NASIC report is not a top-level intelligence report that has been sanctioned by the Director of National Intelligence. As such, it represents the assessment of NASIC rather than necessarily the coordinated and combined conclusion of the US Intelligence Community.

Nonetheless, it’s a unique and useful report that everyone who follows international security and ballistic and cruise missile developments should consult.

Overall, the NASIC report concludes: “The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in ballistic missile capabilities to include accuracy, post-boost maneuverability, and combat effectiveness.” During the same period, “there has been a significant increase in worldwide ballistic missile testing.” The countries developing ballistic and cruise missile systems view them “as cost-effective weapons and symbols of national power” that “present an asymmetric threat to US forces” and many of the missiles “are armed with weapons of mass destruction.” At the same time, “numerous types of ballistic and cruise missiles have achieved dramatic improvements in accuracy that allow them to be used effectively with conventional warheads.”

Some of the more noteworthy individual findings of the new report include:

- Russia’s nuclear modernization is, despite claims by some, not a “buildup” but the size of the Russian ICBM force will continue to decline.

- The Russian RS-26 “short” SS-27 ICBM is still categorized as an ICBM (as in the 2013 report) despite claims by some that it’s an INF weapon.

- The report is the first US official document to publicly identify the ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty: 3M-14. The weapon is assessed to “possibly” have a nuclear option. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

- The Russian SS-N-26 (Oniks or Onix) anti-ship cruise missile that is currently replacing several Soviet-era cruise missiles “possibly” has a nuclear option.

- The range of the dual-capable SS-26 (Islander) SRBM is listed as 350 km (217 miles) rather than the 500-700 km (310-435 miles) often claimed in the public debate.

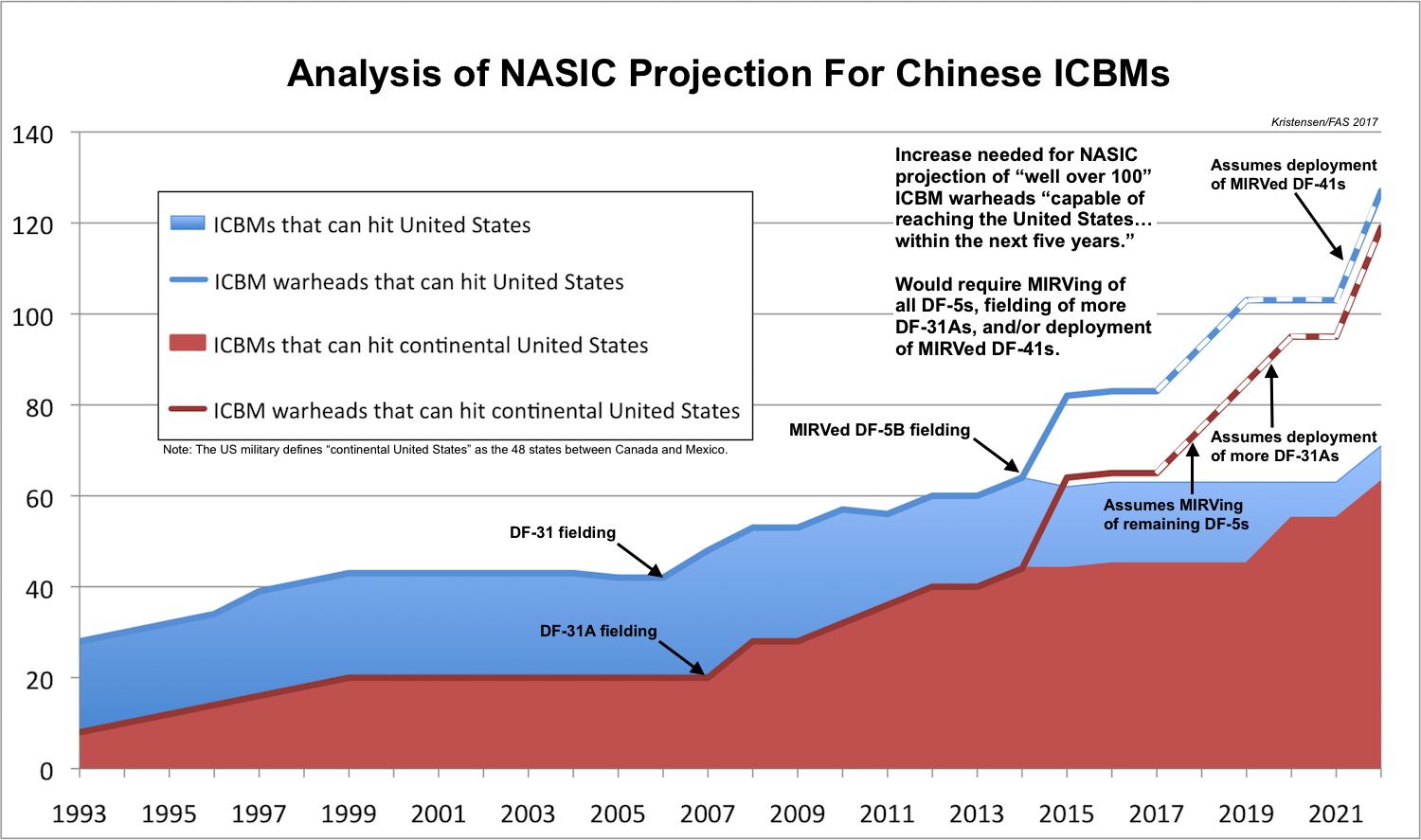

- The number of Chinese warheads capable of reaching the United States could increase to well over 100 in the next five years, six years sooner than predicted in the 2013 report. (The count includes warheads that can only reach Alaska and Hawaii, not necessarily all of continental United States.)

- Deployment of the Chinese DF-31/DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled.

- China’s long-awaited DF-41 ICBM will “possibly” be capable of carrying multiple warheads but is not yet deployed.

- Two Chinese medium-range ballistic missile types (DF-3A and DF-21 Mod 1) have been retired.

- The Chinese ground-launched DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is no longer listed as “conventional or nuclear” but only as “conventional.”

- None of North Korea’s ICBMs are listed as deployed.

Below I go into more details about the individual nuclear-armed states:

Russia

Russia is now more than halfway through its modernization, a generational upgrade that began in the mid/late-1990s and will be completed in the mid-2020s. This includes a complete replacement of the ICBM force (but at lower numbers), transition to a new class of strategic submarines, upgrades of existing bombers, replacement of all dual-capable SRBM units, and replacement of most Soviet-era naval cruise missiles with fewer types.

The NASIC report states that “Russian in September 2014 surpassed the United States in deployed warheads capable of reaching the United States,” referring to the aggregate number reported under the New START treaty. The report does not mention, however, that Russia since 2016 has begun to reduce its deployed strategic warheads and is expected meet the treaty limit in 2018.

ICBMs: Contrary to many erroneous claims in the public debate (see here and here) about a Russia nuclear “build-up,” the NASIC report concludes that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints…” This conclusion fits the assessment Norris and I have made for years that Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces but not increasing the size of the arsenal.

The report counts about 330 ICBM launchers (silos and TELs), significantly fewer than the 400 claimed by the Russian military. The actual number of deployed missiles is probably a little lower because several SS-19 and SS-25 units are in the process of being dismantled.

The development continues of the heavy Sarmat (RS-28), which looks very similar to the existing SS-18. The lighter SS-27 known as RS-26 (Rubezh or Yars-M) appears to have been delayed and still in development. Despite claims by some in the public debate that the RS-26 is a violation of the INF treaty, the NASIC report lists the missile with an ICBM range of 5,500+ km (3,417+ miles), the same as listed in the 2013 version. NASIC says the RS-26, which is designated SS-X-28 by the US Intelligence Community, has “at least 2” stages and multiple warheads.

Overall, “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs,” according to NASIC, another assessment that fits our estimate from the Nuclear Notebook. The NASIC report states that “most” of those missiles “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order.” (In comparison, essentially all US ICBMs are maintained on alert: see here for global alert status.)

SLBMs: The Russian navy is in the early phase of a transition from the Soviet-era Delta-class SSBNs to the new Borei-class SSBN. NASIC lists the Bulava (SS-N-32) SLBM as operational on three Boreis (five more are under construction). The report also lists a Typhoon-class SSBN as “not yet deployed” with the Bulava (the same wording as in the 2013 report), but this is thought to refer to the single Typhoon that has been used for test launches of the Bulava and not imply that the submarine is being readied for operational deployment with the missile.

While the new Borei SSBNs are being built, the six Delta-IVs are being upgrade with modifications to the SS-N-23 SLBM. The report also lists 96 SS-N-18 launchers, corresponding to 6 Delta-III SSBNs. But that appears to include 3-4 SSBNs that have been retired (but not yet dismantled). Only 2 Delta-IIIs appear to be operational, with a third in overhaul, and all are scheduled to be replaced by Borei-class SSBNs in the near future.

Cruise Missiles: The report lists five land-attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability, three of which are Soviet-era weapons. The two new missiles that “possibly” have nuclear capability include the mysterious ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty. The US first accused Russia of treaty violation in 2014 but has refused to name the missile, yet the NASIC report gives it a name: 3M-14. The weapon exists in both “ground, ship & sub” versions and is credited with “conventional, nuclear possible” warhead capability. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

Ground- and sea-based versions of the 3M-14 have different designations. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) identifies the naval 3M-14 as the SS-N-30 land-attack missile, which is part of the larger Kalibr family of missiles that include:

- The 3M-14 (SS-N-30) land-attack cruise missile (the nuclear version might be called SS-N-30A; Pavel Podvig reported back in 2014 that he was told about an 8-meter 3M-14S missile “where ‘S’ apparently stands for ‘strategic’, meaning long-range and possibly nuclear”);

- The 3M-54 (SS-N-27, Sizzler) anti-ship cruise missile;

- The 91R anti-submarine missile.

The US Intelligence Community uses a different designation for the GLCM version, which different sources say is called the SSC-8, and other officials privately say is a modification of the SSC-7 missile used on the Iskander-K. (For public discussion about the confusing names and designations, see here, here, and here.)

The range has been the subject of much speculation, including some as much as 5,472 km (3,400 miles). But the NASIC report sets the range as 2,500 km (1,553 miles), which is more than was reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense in 2015 but close to the range of the old SS-N-21 SLCM.

The “conventional, nuclear possible” description connotes some uncertainty about whether the 3M-14 has a nuclear warhead option. But President Vladimir Putin has publicly stated that it does, and General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command (EUCOM), told Congress in March that the ground-launched version is “a conventional/nuclear dual-capable system.”

ONI predicts that Kalibr-type missiles (remember: Kalibr can refer to land-attack, anti-ship, and/or anti-submarine versions) will be deployed on all larger new surface vessels and submarines and backfitted onto upgraded existing major ships and submarines. But when Russian officials say a ship or submarine will be equipped with the Kalibr, that can potentially refer to one or more of the above missile versions. Of those that receive the land-attack version, for example, presumably only some will be assigned the “nuclear possible” version. For a ship to get nuclear capability is not enough to simply load the missile; it has to be equipped with special launch control equipment, have special personnel onboard, and undergo special nuclear training and certification to be assigned nuclear weapons. That is expensive and an extra operational burden that probably means the nuclear version is only assigned to some of the Kalibr-equipped vessels. The previous nuclear land-attack SLCM (SS-N-21) is only assigned to frontline attack submarines, which will most likely also received the nuclear SS-N-30. It remains to be seen if the nuclear version will also go on major surface combatants such as the nuclear-propelled attack submarines.

The NASIC report also identifies the 3M-55 (P-800 Oniks (Onyx), or SS-N-26 Strobile) cruise missile with “nuclear possible” capability. This weapon also exists in “ground, ships & sub” versions, and ONI states that the SS-N-26 is replacing older SS-N-7, -9, -12, and -19 anti-ship cruise missiles in the fleet. All of those were also dual-capable.

It is interesting that the NASIC report describes the SS-N-26 as a land-attack missile given its primary role as an anti-ship missile and coastal defense missile. The ground-launched version might be the SSC-5 Stooge that is used in the new Bastion-P coastal-defense missile system that is replacing the Soviet-era SSC-1B missile in fleet base areas such as Kaliningrad. The ship-based version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the nuclear-propelled Kirov-class cruisers and Kuznetsov-class aircraft carrier. Presumably it will also replace the SS-N-12 on the Slava-class cruisers and SS-N-9 on smaller corvettes. The submarine version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the Oscar-class nuclear-propelled attack submarine.

NASIC lists the new conventional Kh-101 ALCM but does not mention the nuclear version known as Kh-102 ALCM that has been under development for some time. The Kh-102 is described in the recent DIA report on Russian Military Power.

Short-range ballistic missiles: Russia is replacing the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) missile with the SS-26 (Iskander-M), a process that is expected to be completed in the early-2020s. The range of the SS-26 is often said in the public debate to be the 500-700 km (310-435 miles), but the NASIC report lists the range as 350 km (217 miles), up from 300 km (186 miles) reported in the 2013 version.

That range change is interesting because 300 km is also the upper range of the new category of close-range ballistic missiles. So as a result of that new range category, the SS-26 is now counted in a different category than the SS-21 it is replacing.

China

The NASIC report projects the “number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100 within the next 5 years.” Four years ago, NASIC projected the “well over 100” warhead number might be reached “within the next 15 years,” so in effect the projection has been shortened by 6 years from 2028 to 2022.

One of the reasons for this shortening is probably the addition of MIRV to the DF-5 ICBM force (the MIRVed version is know as DF-5B). All other Chinese missiles only have one warhead each (although the warheads are widely assumed not to be mated with the missiles under normal circumstances). It is unclear, however, why the timeline has been shortened.

The US military defines the “United States” to include “the land area, internal waters, territorial sea, and airspace of the United States, including a. United States territories; and b. Other areas over which the United States Government has complete jurisdiction and control or has exclusive authority or defense responsibility.”

So for NASIC’s projection for the next five years to come true, China would need to take several drastic steps. First, it would have to MIRV all of its DF-5s (about half are currently MIRVed). That would still not provide enough warheads, so it would also have to deploy significantly more DF-31As and/or new MIRVed DF-41s (see graph below). Deployment of the DF-31A is progressing very slowly, so NASIC’s projection probably relies mainly on the assumption that the DF-41 will be deployed soon in adequate numbers. Whether China will do so remains to be seen.

China currently has about 80 ICBM warheads (for 60 ICBMs) that can hit the United States. Of these, about 60 warheads can hit the continental United States (not including Alaska). That’s a doubling of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States (including Guam) over the past 25 years – and a tripling of the number of warheads that can hit the continental United States. The NASIC report does not define what “well over 100” means, but if it’s in the range of 120, and NASIC’s projection actually came true, then it would mean China by the early-2020s would have increased the number of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States threefold since the early 1990s. That a significant increase but obviously but must be seen the context of the much greater number of US warheads that can hit China.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report describes the long and gradual upgrade of the Chinese ballistic missile force. The most significant new development is the fielding of the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with 16+ launchers. The missile was first displayed at the 2015 military parade, which showed 16 launchers – potentially the same 16 listed in the report. NASIC sets the DF-26 range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles), 1,000 km less than the 2017 DOD report.

China does not appear to have converted all of its DF-5 ICBMs to MIRV. The report lists both the single-warhead DF-5A and the multiple-warhead DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3) in “about 20” silos. Unlike the A-version, the B-version has a Post-Boost Vehicle, a technical detail not disclosed in the 2013 report. A rumor about a DF-5C version with 10 MIRVs is not confirmed by the report.