The Pentagon’s 2017 Report On Chinese Military Affairs

The Pentagon report says China is “developing a strategic bomber that officials expect to have a nuclear mission.” The Internet is full of artistic fantasies of what it might look like.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s latest annual report to Congress on Chinese military and security developments describes a nuclear force that is similar to previous years but with a couple of important new developments in the pipeline.

The most sensational nuclear news in the report is the conclusion that China is developing a new strategic nuclear bomber to replace the aging (but upgraded) H-6.

The report also portrays the Chinese ICBM force as a little bigger than it really is because the report lists missiles rather than launchers. But once adjusted for that, the report shows the same overall nuclear missile force as in 2016, with two new land-based missiles under development (DF-26 and DF-41) but not yet operational.

The SSBN force is described as the same four boats but with “others” under construction. The report is a bit hasty to declare China now has a survivable sea-based deterrent, a condition that will require a few more steps.

Finally, the report concludes that Chinese nuclear strategy and doctrine, despite a domestic debate about scope and role, are unchanged from previous years.

Nuclear Bombers?

The Pentagon report states unequivocally that the Chinese Air Force “does not currently have a nuclear mission.” Yet bombers delivered nuclear gravity bombs in at least 12 of China’s nuclear test explosions between 1965 and 1979, so China probably has some dormant air-delivered nuclear capability.

But the report goes further by stating that China now “is developing a strategic bomber that officials expect to have a nuclear mission.”

In making this affirmative conclusion, the report refers to several sources. First, a 2016 statement by PLAAF commander Ma Xiaotian that China was “developing a next generation, long-range strike bomber” to replace the H-6 bombers. Second, the “nuclear” role is attributed to unidentified “observers” and speculations that “past PLA writings” about the need for a “stealth strategic bomber” suggests “aspirations to field a strategic bomber with a nuclear delivery capability.“

Although the Pentagon report says the Chinese Air Force does not currently have a nuclear mission, China has developed and tested nuclear gravity bombs. Mock-ups of the first fission bomb (left) and first thermonuclear bomb are on display in Beijing.

A U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing in 2013 attributed nuclear capability to the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile that is now operational with the H-6K bomber. And in May 2017, the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency told Congress that China is “upgrading its aircraft…with two, new air-launched [ballistic cruise] missiles, one of which may include a nuclear payload.”

Whether a nuclear strategic bomber emerges sometime in the mid-2020s remains to be seen. If so, it would change China’s nuclear posture into a formal Triad of air-, land- and sea-based nuclear capabilities, similar to U.S. and Russian strategic arsenals.

The ICBM Force

The most mysterious nuclear number in the Pentagon report is this: “75-100 ICBMs.”

According to the report, “China’s nuclear arsenal currently consists of approximately 75-100 ICBMs, including the silo-based CSS-4 Mod 2 (DF-5A) and Mod 3(DF-5B); the solid-fueled, road-mobile CSS-10 Mod 1 and Mod 2 (DF-31 and DF-31A); and the more-limited-range CSS-3 (DF-4).”

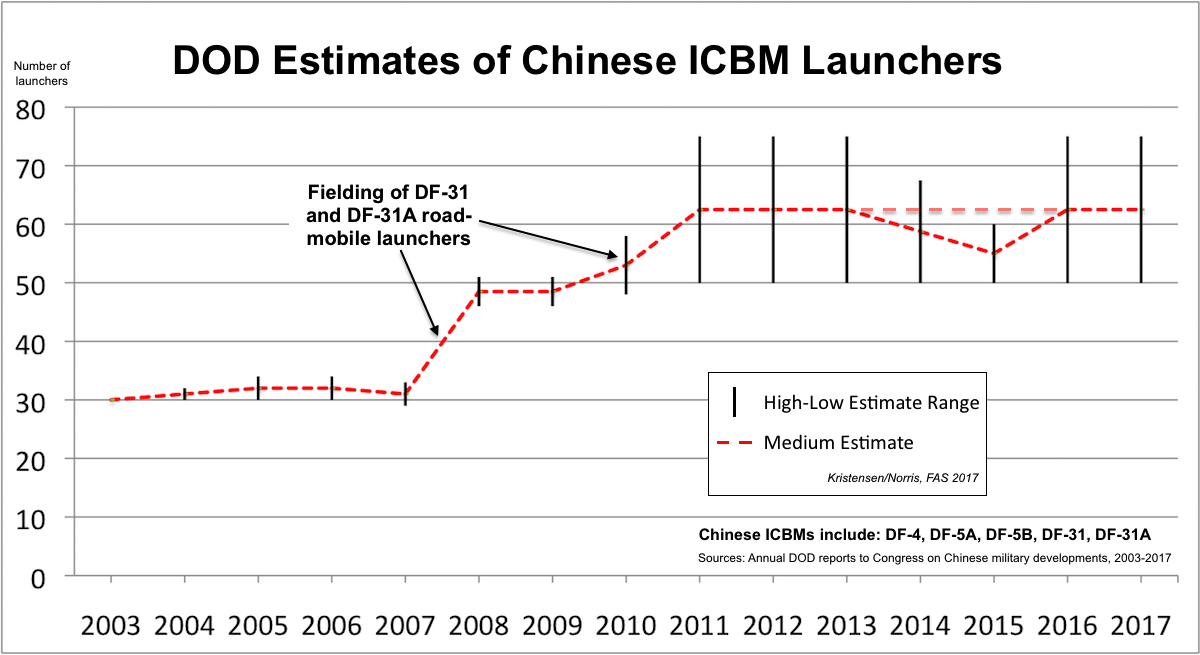

The “75-100 ICBMs” estimate was also made in the 2016 report, but in the 2015 and earlier reports, the estimate was: “China’s ICBM arsenal currently consists of 50-60 ICBMs” of the same five types. For the “75-100 ICBM” estimate to be true, China would have had to add 15-40 ICBMs between 2015 and 2016, which probably did not happen.

The confusion appears to be caused by a change in terminology: the “75-100” is the number of missiles available for the ICBM launchers, some of which have reloads. There are only 50-75 ICBM launchers, the same number listed in the previous six reports. In fact, the ICBM force structure appears to have been relatively stable since 2011.

The 2017 report lists the same number of Chinese ICBM launchers as the previous six years. Click on image to view full size.

Of those 50-75 ICBM launchers, only about 45 (DF-5 and DF-31A) can target the continental United States.

Development continues of the road-mobile DF-41 ICBM, which the report says is “MIRV capable” like the existing silo-based DF-5B. The rumored DF-5C that some news media reported earlier this year is not mentioned in the Pentagon report, even though the Chinese Ministry of Defense appeared to acknowledge the existence of a DF-5C version in a response to the rumors.

Other Land-Base Nuclear Missiles

The report states that China in 2016 began fielding the new road-mobile, dual-capable, intermediate-range DF-26. The missile is not included in the total missile force overview, however, indicating that it is not yet operational. The maximum range is estimated at 4,000 km (2,485 miles), which means it could potentially target Guam from eastern China (similar to the current DF-4 and DF-31).

The DF-26 IRBM is “fielding” but the Pentagon report does not yet include it in the total missile count.

The road-mobile DF-26 will complement the existing force of DF-21 medium-range missiles, of which two versions are nuclear-capable, in China’s regional deterrence mission. And the DF-26 will probably replace the old liquid-fueled DF-4. The other old liquid-fueled missile, the DF-3A, now appears to have been retired.

The SSBN Force

The Pentagon report lists four Jin-class (Type-024) SSBNs as commissioned and “others under construction.” All Jin SSBNs are homeported at the Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island. The report declares that “China’s JIN SSBNs, which are equipped to carry up to 12 CSS-N-14 (JL-2) SLBMs, are the country survivable sea-based nuclear deterrent.”

One of the four Jin-class SSBNs based at Longpo Naval Base on Hainan Island flashes nine of twelve SLBM tubes. Image: DigitalGlobe via GoogleEarth, April 17, 2016.

There are probably several caveats buried in that assessment. First, “survivable” requires that the SSBNs, once deployed at sea, can hide and avoid detection by US and allied anti-submarine warfare capabilities. Jin SSBNs apparently are rather noisy. Second, is the JL-2 operational on the SSBNs? Do they deploy with the missiles, train with them, and do they practice deterrent patrols and launch procedures?

The operational status is unclear from the report, which instead describes an effort to develop “more sophisticated C2 systems and processes” for “future SSBN deterrence patrols…” Rather, the Jin SSBNs appear to be a work in progress.

One indication the Jin-class might not constitute a “survivable” capability is that development of a replacement has already started. The future SSBN, which the Pentagon report says might begin construction in the early-2020s, reportedly will be equipped with a new SLBM known as JL-3. The new missile will probably have longer range than the current JL-2, which is insufficient to target the continental United Stated from Chinese waters.

Once China develops an operational aircraft carrier battle group, the report predicts, it would also be able to protect nuclear ballistic missile submarines stationed on Hainan Island. China has already built a carrier pier at the Yulin Naval Base on Hainan Island (see image below). Like so many other things, such a carrier battle group mission would depend on a number of things, not least how survivable it will be and how effective its anti-submarine capability will be.

The Liaoning docked at the carrier pier at Yulin Naval Base on Hainan Island. Image: DigitalGlobe via GoogleEarth, December 3, 2013.

Additional information:

- Pentagon Annual Report To Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2017

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces 2016

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New Land Foundation, and the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A military depot in central Belarus has recently been upgraded with additional security perimeters and an access point that indicate it could be intended for housing Russian nuclear warheads for Belarus’ Russia-supplied Iskander missile launchers.

The Indian government announced yesterday that it had conducted the first flight test of its Agni-5 ballistic missile “with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-Entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology.

While many are rightly concerned about Russia’s development of new nuclear-capable systems, fears of substantial nuclear increase may be overblown.

Despite modernization of Russian nuclear forces and warnings about an increase of especially shorter-range non-strategic warheads, we do not yet see such an increase as far as open sources indicate.