New START 2017: Russia Decreasing, US Increasing Deployed Warheads

By Hans M. Kristensen

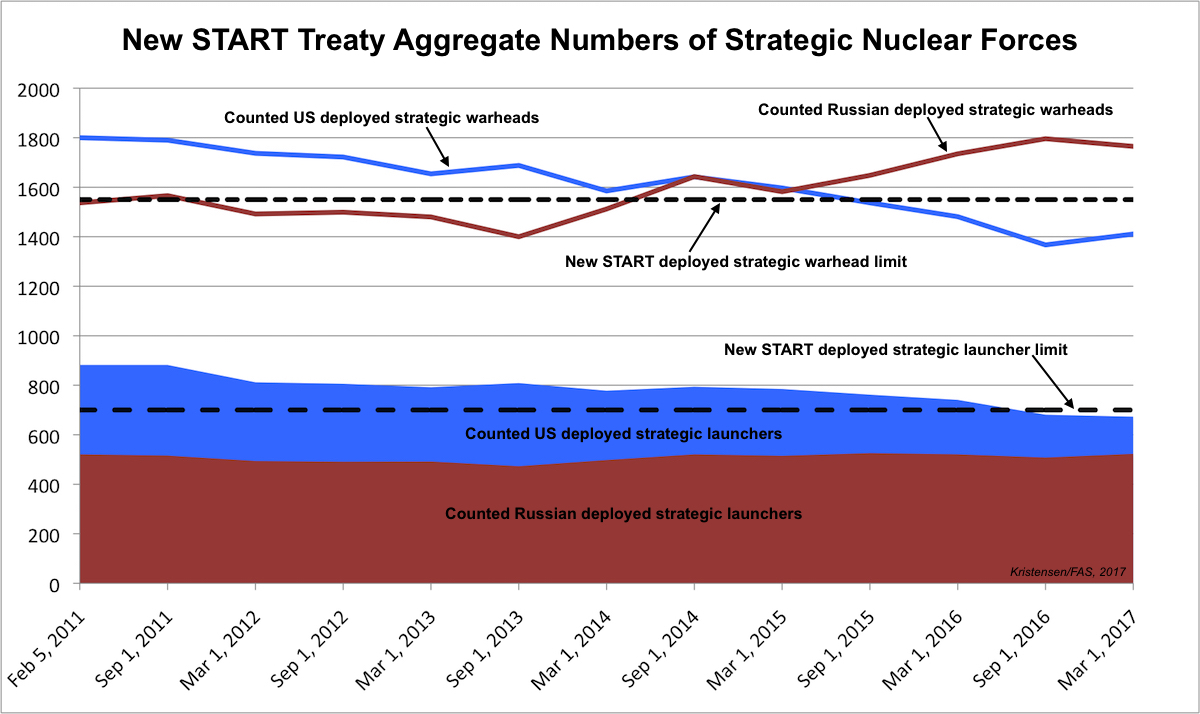

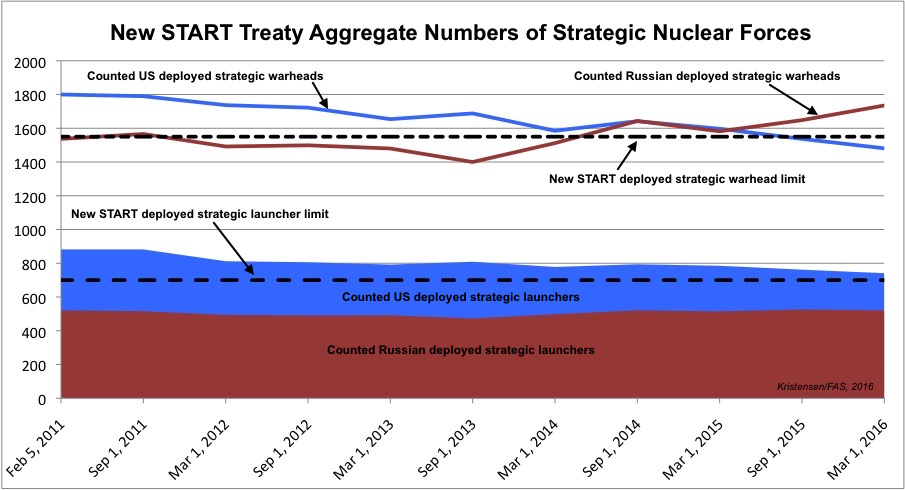

The latest set of New START aggregate data released by the US State Department shows that Russia is decreasing its number of deployed strategic warheads while the United States is increasing the number of warheads it deploys on its strategic forces.

The Russian reduction, which was counted as of March 1, 2017, is a welcoming development following its near-continuous increase of deployed strategic warheads compared with 2013. Bus as I previously concluded, the increase was a fluctuation caused by introduction of new launchers, particularly the Borei-class SSBN.

The US increase, similarly, does not represent a buildup – a mischaracterization used by some to describe the earlier Russian increase – but a fluctuation caused by the force loading on the Ohio-class SSBNs.

Strategic Warheads

The data shows that Russia as of March 1, 2017 deployed 1,765 strategic warheads, down by 31 warheads compared with October 2016. That means Russia is counted as deploying 228 strategic warheads more than when New START went into force in February 2011. It will have to offload an additional 215 warheads before February 2018 to meet the treaty limit. That will not be a problem.

The number of Russian warheads counted by the New START treaty is only a small portion of its total inventory of warheads. We estimate that Russia has a military stockpile of 4,300 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 7,000 warheads.

The United States was counted as deploying 1,411 strategic warheads as of March 1, 2017, an increase of 44 warheads compared with the 1,367 strategic deployed warheads counted in October 2016. The United States is currently below the treaty limit and can add another 139 warheads before the treaty enters into effect in February 2018.

The number of US warheads counted by the New START treaty is only a small portion of its total inventory of warheads. We estimate that the United States has a military stockpile of 4,000 warheads with more retired warheads in reserve for a total inventory of 6,800 warheads.

Strategic Launchers

The New START data shows that Russia as of March 1, 2017 deployed 523 strategic launchers, an increase of 15 launchers compared with October 2016. That means Russia has two (2) more launched deployed today than when New START entered into force in February 2011.

Russia could hypothetically increase its force structure by another 177 launchers over the next ten months and still be in compliance with New START. But its current nuclear modernization program is not capable of doing so.

Under the treaty, Russia is allowed to have a total of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. The data shows that it currently has 816, only 16 above the treaty limit. That means Russia overall has scrapped 49 total launchers (deployed and non-deployed) since New START was signed in February 2011.

The United States is counted as deploying 673 strategic launchers as of March 1, 2017, a decrease of eight (8) launchers compared with October 2016. That means the United States has reduced its force structure by 209 deployed strategic launchers since February 2011.

The US reduction has been achieved by stripping essentially all excess bombers of nuclear equipment, reducing the ICBM force to roughly 400, and making significant progress on reducing the number of launch tubes on each SSBN from 24 to 20.

The United States is below the limit for strategic launchers and could hypothetically add another 27 launchers, a capability it currently has. Overall, the United States has scrapped 304 total launchers (deployed and non-deployed) since the treaty entered into force in February 2011, most of which were so-called phantom launchers that were retired but still contained equipment that made them accountable under the treaty.

The United States currently is counted as having 820 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers. It will need to destroy another 20 to be in compliance with New START by February 2018.

Conclusions and Outlook

Both Russia and the United States are on track to meet the limits of the New START treaty by February 2018. The latest aggregate data shows that Russia is again reducing its deployed strategic warheads and both countries are already below the treaty’s limit for deployed strategic launchers.

In a notorious phone call between Russian President Vladimir Putin and US President Donald Trump, the Russian president reportedly raised the possibility of extending the New START treaty by another five years beyond 2021. But Trump apparently brushed aside the offer saying New START was a bad deal. After the call, Trump said the United States had “fallen behind on nuclear weapons capacity.”

In reality, the United States has not fallen behind but has 150 strategic launchers more than Russia. The New START treaty is not a “bad deal” but an essential tool to provide transparency of strategic nuclear forces and keeping a lid on the size of the arsenals. Russia and the United States should move forward without hesitation to extend the treaty by another five years.

Additional resources:

- New START Aggregate Data (as of March 1, 2017)

- Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Deterring, and Relying Upon, Russia

In confronting Russia and rebutting its claims, the United States is hampered by unnecessary or inappropriate classification of national security information, according to former Pentagon official and Russia specialist Evelyn Farkas.

“We are not very good at declassifying and reclassifying information that is not propaganda, showing pictures of what the Russians are doing,” Dr. Farkas told the House Armed Services Committee last year.

“We did it a couple of times, and interestingly, the Open Skies Treaty was actually useful because, unlike satellites, that is unclassified data that is gleaned as a result of aircraft that take pictures for the purposes of our treaty requirements.”

“But in any event, I think that we can do more just by getting some information out. That is the minimum that the State Department could do and should do, together with the intelligence community. But it should also be a push, not a pull–not leaders like yourselves or executive branch members saying, ‘Declassify that,’ but actually the intelligence community looking with the State Department, ‘What should we declassify?’ not waiting for somebody to tell them to do it,” she said.

See Understanding and Deterring Russia: U.S. Policies and Strategies, House Armed Services Committee, February 10, 2016 (published January 2017).

The same hearing featured testimony from Fiona Hill of the Brookings Institution. She has just been offered a position in the Trump White House as senior director for Europe and Russia, Foreign Policy reported today. See Trump Taps Putin Critic for Senior White House Position, by John Hudson, March 2.

“Putin is a professional secret service operative,” Ms. Hill told the House Armed Services Committee. “He is very unusual among world leaders at present. Putin has also been trained to conceal his true identity and intentions at all times. This is what makes him particularly difficult to deal with.”

Meanwhile, yesterday the National Reconnaissance Office successfully launched a new U.S. spy satellite aboard an Atlas V rocket — that was powered by a Russian RD-180 engine. (“All in a day’s work,” tweeted Bill Arkin.)

Though it might seem incongruous that U.S. intelligence collection would be dependent on Russian space technology, that is how things stand and how they are likely to remain for some time.

“Goodness knows we want off the Russian engine as fast as any human being on the planet,” said Gen. John E. Hyten of US Air Force Space Command. “We want off the Russian engine as fast as possible.”

But there is a but. “But, asking the American taxpayers to write a check for multiple billions of dollars in the future for an unknown is a very difficult thing to do, and for the Air Force, that will be a very difficult budget issue to work,” Gen. Hyten told the House Armed Services Committee last year.

Pentagon official Dyke Weatherington concurred: “The Department continues to be dedicated to ending use of the Russian manufactured RD-180 engine as soon as reasonably possible, but still believes that access to the RD-180 while transitioning to new and improved launch service capabilities is the optimal way forward to meet statutory and Department policy requirements for assured access to space in both the near and long term.”

Even a new US-manufactured rocket engine will not suffice, Mr. Weatherington added. “Any new engine still has to be incorporated into a launch vehicle. The Department does not want to be in a position where significant resources have been expended on an engine and no commercial provider has built the necessary vehicle to use that engine.”

Their testimony was presented at a 2016 hearing on military and intelligence space programs that has recently been published. See Fiscal Year 2017 Budget Request for National Security Space, House Armed Services Committee, March 15, 2016.

Will Trump Be Another Republican Nuclear Weapons Disarmer?

By Hans M. Kristensen

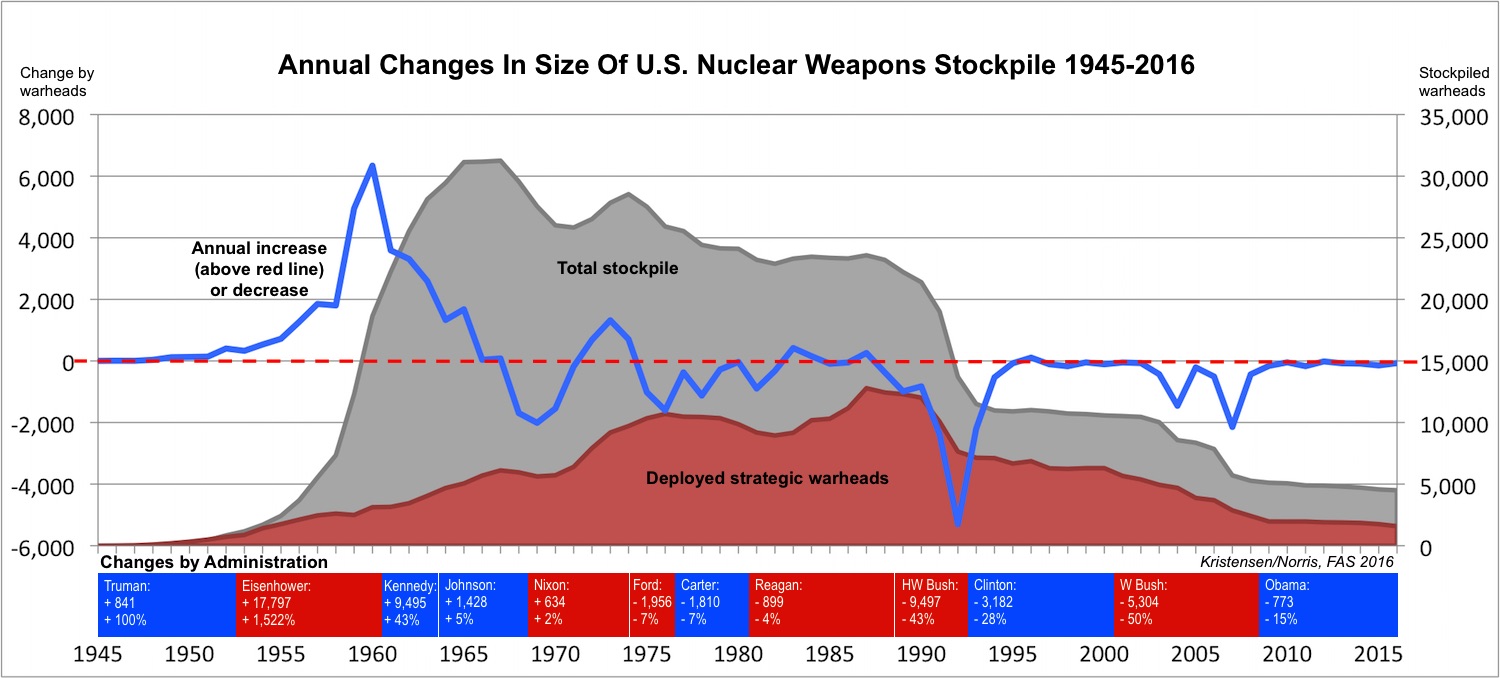

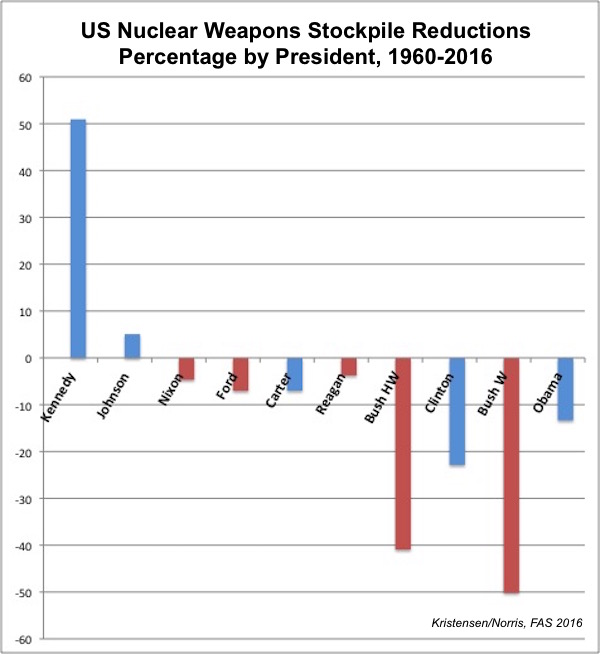

Republicans love nuclear weapons reductions, as long as they’re not proposed by a Democratic president.

That is the lesson from decades of US nuclear weapons and arms control management.

If that trend continues, then we can expect the new Donald Trump administration to reduce the US nuclear weapons arsenal more than the Obama administration did.

What? I know, it sounds strange but the record is very clear: During the post-Cold War era, Republication administrations have – by far – reduced the US nuclear weapons stockpile more than Democratic administrations (see graph below).

Even if we don’t count numbers of weapons (because arsenals have gotten smaller) but only look at by how much the nuclear stockpile was reduced, the history is clear: Republican presidents disarm more than Democrats (see graph below).

It’s somewhat of a mystery. Because Democratic presidents are generally seen to be more likely to propose nuclear weapons reductions. President Obama did so repeatedly. But when Democratic presidents have proposed reductions, the Republican opposition has normally objected forcefully. Yet Republican lawmakers won’t oppose reductions if they are proporsed by a Republican president.

Conversely, Democratic lawmakers will not opposed Republican reductions and nor will they oppose reductions proposed by a Democratic president.

As a result, if the Republicans control both the White House and Congress, as they do now after the 2016 election, the chance of significant reductions of nuclear weapons seems more likely.

Whether Donald Trump will continue the Republication tradition remains to be seen. US-Russian relations are different today than when the Bush administrations did their reductions. But both countries have far more nuclear weapons than they need for national security. And Trump would be strangely out of tune with long-held Republican policy and practice if he does not order a substantial reduction of the US nuclear weapons stockpile.

Perhaps he should use that legacy to try to reach an agreement with Russia to continue to reduce US and Russia nuclear arsenals to the benefit of both countries.

Further reading: Status of World Nuclear Forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows Russian Warhead Increase Before Expected Decrease

By Hans M. Kristensen

The latest set of so-called New START treaty aggregate data published by the U.S. State Department shows that Russia is continuing to increase the number of nuclear warheads it deploys on its declining inventory of strategic launchers.

Russia now has 259 warheads more deployed than when the treaty entered into force in 2011.

Rather than a nuclear build-up, however, the increase is a temporary fluctuation cause by introduction of new types of launchers that will be followed by retirement of older launchers before 2018. Russia’s compliance with the treaty is not in doubt.

In all other categories, the data shows that Russia and the United States continue to reduce the overall size of their strategic nuclear forces.

Strategic Warheads

The aggregate data shows that Russia has continued to increase its deployed strategic warheads since 2013 when it reached its lowest level of 1,400 warheads. Russian strategic launchers now carry 396 warheads more.

Overall, Russia has increase its deployed strategic warheads by 259 warheads since New START entered into force in 2011. Although it looks bad, it has no negative implications for strategic stability.

The Russian warhead increase is probably a temporary anomaly caused primarily by the fielding of additional new Borei-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). The third boat of the class deployed to its new base on the Kamchatka Peninsula last month, joining another Borei SSBN that transferred to the Pacific in 2015.

The United States, in contrast, has continued to decrease its deployed strategic warheads. It dipped below the treaty limit in September 2015 but has continued to decrease its deployed warheads to 1,367 deployed strategic warheads

Overall, the United States has decreased its deployed strategic warheads by 433 since New START entered into force in February 2011.

As a result, the disparity in Russian and U.S. deployed strategic warheads is now greater than at any previous time since New START entered into force in 2011: 429 warheads.

It’s important to remind that the counted deployed strategic warheads only represent a portion of the two countries total warhead inventories; we estimate Russia and the United States each have roughly 4,500 warheads in their military stockpiles. The New START treaty only limits how many strategic weapons can be deployed but has no direct effect on the size of the total nuclear stockpiles.

The Russian increase in deployed strategic warheads is temporary due to fielding of several new Borei-class ballistic missile submarines. This picture shows the Vladimir Monomakh arriving at the submarine base near Petropavlovsk on September 27, 2016.

Strategic Launchers

The aggregate data shows that both Russia and the United States continue to reduce their strategic launchers.

Russia has been below the treaty limit of 700 deployed strategic launchers since New START entered into force in 2011. Even so, it continues to reduce its strategic launchers. Thirteen deployed launchers have been removed since March 2016 and Russia overall now has 13 launchers fewer than in 2011.

Russia will have to dismantle another 47 launchers to meet the limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers by February 2018. Those launchers will likely come from retirement of the remaining Delta III SSBNs, retirement of additional Soviet-era ICBMs, and destruction of empty excess ICBM silos.

The United States is not also for the first time below the limit for deployed strategic launchers. The latest data lists 681 launchers deployed, a reduction of 60 compared with March 2016. The reduction reflects the ongoing work to denuclearize excess B-52H bombers, deactivate four excess launch tubes on each SSBN, and remove ICBMs from 50 excess silos.

The United States still has a considerable advantage in deployed strategic launchers: 681 versus Russia’s 508. But the disparity of 173 launchers is smaller than it was six months ago. The United States will need to dismantle another 48 launchers to meet the treaty’s limit of 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers by February 2018.

Strategic Context

The ongoing implementation of the New START treaty is one of the only remaining bright spots on the otherwise tense and deteriorating relationship between Russia and the United States. Despite the current increase of Russian deployed strategic warheads, which is temporary and will be followed by retirement of older systems in the next few years that will reduce the count, Russian compliance with the treaty by 2018 is not in doubt. And both countries continue to reduce their deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers.

In fact, the temporary warhead increase seems to be of little concern to U.S. military planners. DOD concluded in 2012 that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty…”

Equally important are the ongoing onsite inspections and notifications between the United States and Russia. The two countries have each carried out 103 inspections and exchanged 11,817 notifications since the treaty entered into force in 2011. These activities are increasingly important confidence-building measures.

Yet the modest reductions under the treaty must also be seen in the context of the extensive nuclear weapons modernization programs underway in both countries. Although these programs do not constitute a buildup of the overall nuclear arsenal, they are very comprehensive and reaffirm the determination by both Russia and the United States to retain large offensive nuclear arsenals at high levels of operational readiness.

Although those forces are significantly smaller than the arsenals that existed during the Cold War, they are nonetheless significantly larger than the arsenals of any other nuclear-armed state.

Moreover, New START contains no sub-limits, which enables both sides to take advantage of loopholes. Whereas the now-abandoned START II treaty banned multiple warheads (MIRV) on ICBMs, the New START treaty has no such limits, which enables Russia to incorporate MIRV on its new ICBMs and the United States to store hundreds of non-deployed warheads for re-MIRVing of its ICBMs. Russia is developing a new “heavy” ICBM with MIRV and the next U.S. ICBM (GBSD) will be capable of carrying MIRV as well.

Similarly, the “fake” bomber count of attributing only one deployed strategic weapon per bomber despite its capacity to carry many more has caused both sides to retain large inventories of non-deployed weapons to retain a quick upload capability with many hundreds of long-range nuclear cruise missiles. And both sides are developing new nuclear-armed cruise missiles.

How the two countries justify such large arsenals is somewhat of a mystery but seem to be mainly determined by the size of the other side’s arsenal. According to the U.S. State Department, the New START “limits are based on the rigorous analysis conducted by Department of Defense planners in support of the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review.”

Yet a recent GAO analysis of the 2010 NPR force structure found that “DOD officials were unable to provide us documentation of the NPR’s analysis of strategic force structure options that were considered.” Instead, STRATCOM, the Air Force and the Navy conducted their own analysis of options, which were discussed at senior-level meetings but not documented.

Both sides can easily reduce their nuclear forces further and increase security, reduce insecurity, and save money while doing so. Possible steps include: a five-year extension of the New START Treaty, lowering the limits of the existing treaty by one-third while maintaining the inspection regime, and taking unilateral steps to reduce the nuclear weapons modernization programs.

Additional information:

- Status of world nuclear forces

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: US nuclear forces 2016

- FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russia nuclear forces 2016

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Increasing Nuclear Bomber Operations

CBS’s 60 Minutes program Risk of Nuclear Attack Rises described that Russia may be lowering the threshold for when it would use nuclear weapons, and showed how U.S. nuclear bombers have started flying missions they haven’t flown since the Cold War: Over the North Pole and deep into Northern Europe to send a warning to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The program follows last week’s program The New Cold War where viewers were shown unprecedented footage from STRATCOM’s command center at Omaha Air Base in Nebraska.

Producer Mary Welch and correspondent David Martin have produced a fascinating and vital piece of investigative journalism showing disturbing new developments in the nuclear relationship between Russia and the United States.

They were generous enough to consult me and include me in the program to discuss the increasing Cold War and dangerous military posturing.

Nuclear Bomber Operations Context

Just a few years ago, U.S. nuclear bombers didn’t spend much time in Europe. They were focused on operations in the Middle East, Western Pacific, and Indian Ocean. Despite several years of souring relations and mounting evidence that the “reset” with Russia had failed or certainly not taken off, NATO couldn’t make itself say in public that Russia gradually was becoming an adversary once again.

Whatever hesitation was left changed in March 2014 when Vladimir Putin sent his troops to invade Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The act followed years of Russian efforts to coerce the Baltic States, growing and increasingly aggressive military operations around European countries, and explicit nuclear threats against NATO countries getting involved in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

Granted, NATO may not have been a benign neighbor, with massive expansion eastward of new members all the way up to the Russian border, and a consistent tendency to ignore or dismiss Russian concerns about its security interests.

But whatever else Putin might have thought he would gain from his acts, they have awoken NATO from its detour in Afghanistan and refocused the Alliance on its traditional mission: defense of NATO territory against Russian aggression. As a result, Putin will now get more NATO troops along his western and southern borders, larger and more focused military exercises more frequently in the Baltic Sea and Black Sea, increasing or refocused defense spending in NATO, and a revitalization of a near-slumbering nuclear mission in Europe.

Six years ago the United States was this close to pulling its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons out of Europe. Only an engrained NATO nuclear bureaucracy aided by the Obama administration’s lack of leadership prevented the withdrawal of the weapons. Russia has complained about them for years but now it seems very unlikely that the modernization of the F-35A with the B61-12 guided bomb can be stopped. The weapons might even get a more explicit role against Russia, although this is still a controversial issue for some NATO members.

But the U.S. military would much prefer to base the nuclear portion of its extended deterrence mission in Europe on strategic bombers rather than the short-range fighter-bombers forward deployed there. The non-strategic nuclear weapons are far too controversial and vulnerable to the myriads of political views in the host countries. Strategic bombers are free of such constraints.

A New STRATCOM-EUCOM Link

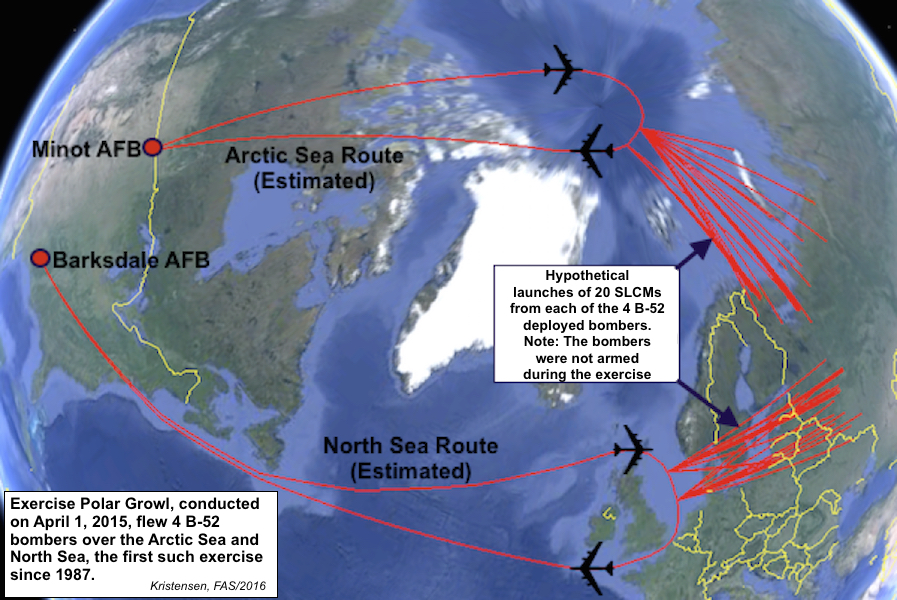

Therefore, even before NATO at the Warsaw Summit this summer decided to reinvigorate its commitment to nuclear deterrence, former U.S. European Command (EUCOM) commander General Philip Breedlove told Congress in February 2015, EUCOM had already “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence [BAAD] missions to NATO regional exercises” as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve to deter Russia.

Less than two months later, on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers took of from their bases in the United States and flew across the North Pole and North Sea in a simulated strike exercise against Russia. The bombers proceeded all the way to their potential launch points for air-launched cruise missiles before they returned to the United States. Such an exercise had not been conducted since the late-1980s against the Soviet Union. Combined, the four bombers could have delivered 80 long-range nuclear cruise missiles with a combined explosive power of 800 Hiroshima bombs.

During Exercise Polar Growl on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers flew along two routes into the Arctic and North Sea regions that appeared to simulate long-range strikes against Russia. The four bombers were capable of launching up to 80 nuclear air-launched cruise missiles with a combined explosive power equivalent to 800 Hiroshima bombs. All routes are approximate.

Despite its strategic implications, Polar Growl also had a distinctive regional – even limited – objective because of the crisis in Europe. Planning for such regional deterrence scenarios have taken on a new importance during the past couple of decades and they have become central to current planning because it is in such regional scenarios that the United States believes it is most likely that nuclear weapons could actually be used.

“The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, in 2014 predicted only a few weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, “and continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.”

Two weeks after the bombers returned from Polar Growl, Robert Scher, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities, told Congress: “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts.” This includes “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

Nuclear Conventional Integration

Much of this increased planning involves conventional weapons such as the new long-range conventional JASSM-ER cruise missile, but the planning also involves nuclear. In fact, conventional and nuclear appear to be integrating in a way they have done before. This effort was described recently by Brian McKeon, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, during the annual STRATCOM Deterrence Symposium:

In the Department of Defense we’re working to effectively integrate conventional and nuclear planning and operations. Integration is not new but we’re renewing our focus on it because of recent developments and how we see potential adversaries preparing for conflict. This is an area where the focus in Omaha has really led the way and I want to commend Admiral Haney and STRATCOM for being able to shift planning so quickly toward this approach and thinking though conflict. No one wants to think about using nuclear weapons and we all know the principle role of nuclear weapons is to deter their use by others. But as we’ve seen, out adversaries may not hold the same view.

Let me be clear that when I say integration I do not mean to say we have lowered the threshold for nuclear use or would turn to nuclear weapons sooner in a conventional campaign. As we stated in the Nuclear Posture Review, the United States will “only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.” The NPR also emphasized the importance of reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, a requirement that has been advanced in our planning consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance, including with non-nuclear strike options.

What I mean by integration is synchronizing our thinking across all domains in a way that maximizes the credibility and flexibility of our deterrent through all phases of conflict and responds appropriately to asymmetrical escalation. For too long, crossing the nuclear threshold was through to move a nuclear conflict out of the conventional dimension and wholly into the nuclear realm. Potential adversaries are exploring ways to cross this threshold with low-yield nuclear weapons to test out resolve, capabilities, and Allied cohesion. We must demonstrate that such a strategy cannot succeed so that it is never attempted. To that end we’re planning and exercising our non-nuclear operations conscious of how they might influence an adversary’s decision to go nuclear.

We also plan for the possibility of ongoing U.S. and Allied operations in a nuclear environment and working to strengthen resiliency of conventional operations to nuclear attack. By making sure our forces are capable of continuing the fight following a limited nuclear use we preserve flexibility for the president. And by explicitly preparing for the implication of an adversary’s limited nuclear use and providing credible options for the President, we strengthen our deterrent and reduce the risk of employment in the first instance.

Regional nuclear scenarios no longer primarily involve planning against what the Bush administration called “rogue states” such as North Korea and Iran, but increasingly focus on near-peer adversaries (China) and peer adversaries (Russia). “We are working as part of the NATO alliance very carefully both on the conventional side as well as meeting as part of the NPG [Nuclear Planning Group] looking at what NATO should be doing in response to the Russian violation of the INF Treaty,” Scher explained.

STRATCOM last updated the strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) in 2012 and is currently about to publish an updated version that incorporates the changes caused by the Obama administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy from 2013.

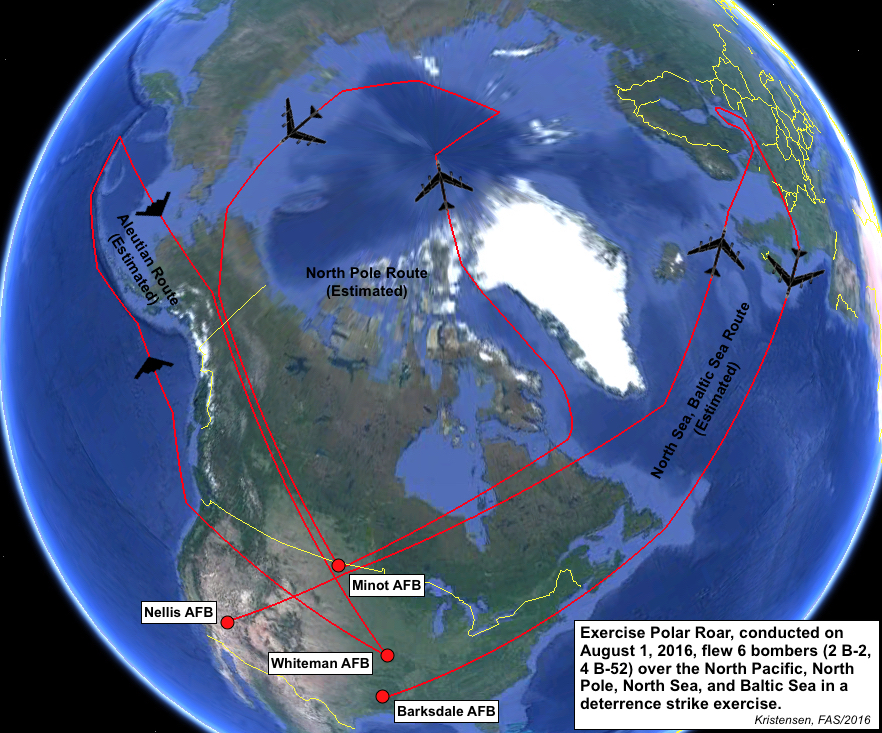

Two months ago, a little over a year after Polar Growl, another bomber strike exercise was launched. This time six bombers (4 B-52s and 2 B-2s) flew closer to Russia and simultaneously over the Arctic Sea, North Sea, Baltic Sea, and North Pacific Ocean. The six Polar Roar sorties required refueling support from 24 KC-135 tankers as well as E4-B Advanced Airborne Command Post and E-6B TACAMO nuclear command and control aircraft.

The routes (see below) were eerily similar to the Chrome Dome airborne alert routes that were flown by nuclear-armed bombers in the 1960s against the Soviet Union.

Exercise Polar Roar on August 1, 2016, followed Exercise Polar Growl from 2015 but involved more bombers, both nuclear-capable and conventional-only, and flew closer to Russia and deep into the Baltic Sea. Polar Roar also included B-2 stealth bombers in the North Pacific. All routes are approximate.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russia Foreign Intelligence Service Expands

The headquarters complex of the Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR) of the Russian Federation has expanded dramatically over the past decade, a review of open source imagery reveals.

Since 2007, several large new buildings have been added to SVR headquarters, increasing its floor space by a factor of two or more. Nearby parking capacity appears to have quadrupled, more or less.

The compilation of open source imagery was prepared by Allen Thomson. See Expansion of Russian Foreign Intelligence Service HQ (SVR; Former KGB First Main Directorate) Between 2007 and 2016, as of July 11, 2016.

Whether the expansion of SVR headquarters corresponds to changes in the Service’s mission, organizational structure or budget could not immediately be learned.

Russian journalist and author Andrei Soldatov, who runs the Agentura.ru website on Russian security services, noted that the expansion “coincides with the appointment of the current SVR director, Mikhail Fradkov, in 2007.” He recalled that when President Putin introduced Fradkov to Service personnel, he said that the SVR should endeavor to help Russian corporations abroad, perhaps indicating a new mission emphasis.

FAS Nuclear Notebook Published: Russian Nuclear Forces, 2016

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

In our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Norris and I take the pulse on Russia’s nuclear arsenal, reviewing its strategic modernization programs and the status of its non-strategic nuclear forces.

Despite what you might read in the news media and on various web sites, the Russian modernization is not a “buildup” but a transition from Soviet-era nuclear weapons to newer and more reliable types on a less-than-one-for-one basis.

As a result, the Russian nuclear arsenal will likely continue to decline over the next decade – with or without a new arms control agreement. But the trend is that the rate of decline is slowing and Russian strategic nuclear forces may be leveling out around 500 launchers with some 2,400 warheads.

Because Russia has several hundred strategic launchers fewer than the United States, the Russian modernization program emphasizes deployment of multiple warheads on ballistic missiles to compensate for the disparity and maintain rough parity in overall warhead numbers. Before 2010, no Russian mobile launcher carried multiple warheads; by 2022, nearly all will.

As a result, Russia currently has more nuclear warheads deployed on its strategic missiles than the United States. But not by many and Russia is expected to meet the limit set by the New START treaty by 2018.

Russia to some extent also uses its non-strategic nuclear weapons to keep up. But non-strategic nuclear forces have unique roles that appear to be intended to compensate for Russia’s inferior conventional forces, which – despite important modernization such as long-range conventional missiles – are predominantly made up of Soviet-era equipment or upgraded Soviet-era equipment.

Russia’s non-strategic nuclear forces are currently the subject of much interest in NATO because of concern that Russian military strategy has been lowering the threshold for when nuclear weapons could potentially be used. Russia has also been increasing operations and exercises with nuclear-capable forces, a trend that can also be seen in NATO and U.S. military posturing.

More information:

FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russian nuclear forces, 2016

Who’s Got What: Status of World Nuclear Forces

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Transparency and the Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

I was reading through the latest Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) and wondering what I should pick to critique the Obama administration’s nuclear policy.

After all, there are plenty of issues that deserve to be addressed, including:

– Why NNSA continues to overspend and over-commit and create a spending bow wave in 2021-2026 in excess of the President’s budget in exactly the same time period that excessive Air Force and Navy modernization programs are expected to put the greatest pressure on defense spending?

– Why a smaller and smaller nuclear weapons stockpile with fewer warhead types appears to be getting more and more expensive to maintain?

– Why each warhead life-extension program is getting ever more ambitious and expensive with no apparent end in sight?

– And why a policy of reductions, no new nuclear weapons, no pursuit of new military missions or new capabilities for nuclear weapons, restraint, a pledge to “put an end to Cold War thinking,” and the goal of disarmament, instead became a blueprint for nuclear overreach with record funding, across-the-board modernizations, unprecedented warhead modifications, increasing weapons accuracy and effectiveness, reaffirmation of a Triad and non-strategic nuclear weapons, continuation of counterforce strategy, reaffirmation of the importance and salience of nuclear weapons, and an open-ended commitment to retain nuclear weapons further into the future than they have existed so far?

What About The Other Nuclear-Armed States?

Despite the contradictions and flaws of the administration’s nuclear policy, however, imagine if the other nuclear-armed states also published summaries of their nuclear weapons plans. Some do disclose a little, but they could do much more. For others, however, the thought of disclosing any information about the size and composition of their nuclear arsenal seems so alien that it is almost inconceivable.

Yet that is actually one of the reasons why it is necessary to continue to work for greater (or sufficient) transparency in nuclear forces. Some nuclear-armed states believe their security depends on complete or near-compete nuclear secrecy. And, of course, some nuclear information must be protected from disclosure. But the problem with excessive secrecy is that it tends to fuel uncertainty, rumors, suspicion, exaggerations, mistrust, and worst-case assumptions in other nuclear-armed states – reactions that cause them to shape their own nuclear forces and strategies in ways that undermine security for all.

Nuclear-armed states must find a balance between legitimate secrecy and transparency. This can take a long time and it may not necessarily be the same from country to country. The United States also used to keep much more nuclear information secret and there are many institutions that will always resist public access. But maximum responsible disclosure, it turns out, is not only necessary for a healthy public debate about nuclear policy, it is also necessary to communicate to allies and adversaries what that policy is about – and, equally important, to dispel rumors and misunderstandings about what the policy is not.

Nuclear transparency is not just about pleasing the arms controllers – it is important for national security.

So here are some thoughts about what other nuclear-armed states should (or could) disclose about their nuclear arsenals – not to disclose everything but to improve communication about the role of nuclear weapons and avoid misunderstandings and counterproductive surprises:

Russia should publish:

Russia should publish:

– Full New START aggregate data numbers (these numbers are already shared with the United States, that publishes its own numbers)

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Number of history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has made statements about percentage reductions since 1991 but not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of which nuclear forces are nuclear-capable (has made some statements about strategic forces but not shorter-range forces)

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces (has made occasional statements about modernizations but no detailed plan)

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

China should publish:

China should publish:

– Size and history of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (stated in 2004 that it possessed the smallest arsenal of the nuclear weapon states but has not disclosed numbers or history)

– Basic overview of its nuclear-capable forces

– Plans for future years force levels of long-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

France should publish:

France should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has disclosed the size of its nuclear stockpile in 2008 and 2015 (300 weapons), but not the history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has declared dismantlement of some types but not history)

(France has disclosed its overall force structure and some nuclear budget information is published each year.)

Britain should publish:

Britain should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile (has declared some approximate historic numbers, declared the approximate size in 2010 (no more than 225), and has declared plan for mid-2020s (no more than 180), but has not disclosed history)

– Number and history of nuclear warhead dismantlement (has announced dismantlement of systems but not numbers or history)

(Britain has published information about the size of its nuclear force structure and part of its nuclear budget.)

Pakistan should publish:

Pakistan should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

India should publish:

India should publish:

– History of overall nuclear weapons stockpile

– Basic overview of nuclear-capable forces (occasionally declares that a missile test involves nuclear-capable weapon)

– Plans for future years force levels of longer-range nuclear forces

– Overall status and out-year budgets for nuclear weapons and nuclear forces

Israel should publish:

Israel should publish:

…or should it? Unlike other nuclear-armed states, Israel has not publicly confirmed it has a nuclear arsenal and has said it will not be the first to introduce nuclear weapons in the Middle East. Some argue Israel should not confirm or declare anything because of fear it would trigger nuclear arms programs in other Middle Eastern countries.

On the other hand, the existence of the Israeli nuclear arsenal is well known to other countries as has been documented by declassified government documents in the United States. Official confirmation would be politically sensitive but not in itself change national security in the region. Moreover, the secrecy fuels speculations, exaggerations, accusations, and worst-case planning. And it is hard to see how the future of nuclear weapons in the Middle East can be addressed and resolved without some degree of official disclosure.

North Korea should publish:

North Korea should publish:

Well, obviously this nuclear-armed state is a little different (to put it mildly) because its blustering nuclear threats and statements – and the nature of its leadership itself – make it difficult to trust any official information. Perhaps this is a case where it would be more valuable to hear more about what foreign intelligence agencies know about North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. Yet official disclosure could potentially serve an important role as part of a future de-tension agreement with North Korea.

Additional information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces with links to more information about individual nuclear-armed states.

“Nuclear Weapons Base Visits: Accident and Incident Exercises as Confidence-Building Measures,” briefing to Workshop on Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons in Europe: Transparency and Confidence-Building Measures in Practice, German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Berlin, 27-28 March 2014.

“Nuclear Warhead Stockpiles and Transparency” (with Robert Norris), in Global Fissile Material Report 2013, International Panel on Fissile Materials, October 2013, pp. 50-58.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START Data Shows Russian Increases and US Decreases

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Updated April 3, 2016] Russia continues to increase the number of strategic warheads it deploys on its ballistic missiles counted under the New START Treaty, according to the latest aggregate data released by the US State Department.

The data shows that Russia now has almost 200 strategic warheads more deployed than when the New START treaty entered into force in 2011. Compared with the previous count in September 2015, Russia added 87 warheads, and will have to offload 185 warheads before the treaty enters into effect in 2018.

The United States, in contrast, has continued to decrease its deployed warheads and the data shows that the United States currently is counted with 1,481 deployed strategic warheads – 69 warheads below the treaty limit.

The Russian increase is probably mainly caused by the addition of the third Borei-class ballistic missile submarine to the fleet. Other fluctuations in forces affect the count as well. But Russia is nonetheless expected to reach the treaty limit by 2018.

The Russian increase of aggregate warhead numbers is not because of a “build-up” of its strategic forces, as the Washington Times recently reported, or because Russia is “doubling their warhead output,” as an unnamed US official told the paper. Instead, the temporary increase in counted warheads is caused by fluctuations is the force level caused by Russia’s modernization program that is retiring Soviet-era weapons and replacing some of them with new types.

Strategic Launchers

The aggregate data also shows that Russia is now counted as deploying exactly the same number of strategic launchers as when the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011: 521.

But Russia has far fewer deployed strategic launchers than the United States (a difference of 220 launchers) and has been well below the treaty limit since before the treaty was signed. The United States still has to dismantle 41 launchers to reach the treaty limit of 700 deployed strategic launchers.

The United States is counted as having 21 launchers fewer than in September 2015. That reduction involves emptying of some of the ICBM silos (they plan to empty 50) and denuclearizing a few excess B-52 bombers. The navy has also started reducing launchers on each Trident submarine from 24 missile tubes to 20 tubes. Overall, the United States has reduced its strategic launchers by 141 since 2011, until now mainly by eliminating so-called “phantom” launchers – that is, aircraft that were not actually used for nuclear missions anymore but had equipment onboard that made them accountable.

Again, the United States had many more launchers than Russia when the treaty was signed so it has to reduce more than Russia.

New START Counts Only Fraction of Arsenals

Overall, the New START numbers only count a fraction of the total nuclear warheads that Russia and the United States have in their arsenals. The treaty does not count weapons at bomber bases or central storage, additional ICBM and submarine warheads in storage, or non-strategic nuclear warheads.

Our latest count is that Russia has about 7,300 warheads, of which nearly 4,500 are for strategic and tactical forces. The United States has about 6,970 warheads, of which 4,670 are for strategic and tactical forces.

See here for our latest estimates: https://fas.org/issues/nuclear-weapons/status-world-nuclear-forces/

See analysis of previous New START data: https://fas.org/blogs/security/2015/10/newstart2015-2/

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Questions About The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

During a Senate Appropriations Committee hearing on March 16, Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), the ranking member of the committee, said that U.S. Strategic Command had failed to convince her that the United States needs to develop a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile; the LRSO (Long-Range Standoff missile).

“I recently met with Admiral Haney, the head of Strategic Command regarding the new nuclear cruise missile and its refurbished warhead. I came away unconvinced of the need for this weapon. The so-called improvements to this weapon seemed to be designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war. I find that a shocking concept. I think this is really unthinkable, especially when we hold conventional weapons superiority, which can meet adversaries’ efforts to escalate a conflict.”

Feinstein made her statement only a few hours after Air Force Secretary Deborah James had told the House Armed Services Committee on the other side of the Capitol that the LRSO will be capable of “destroying otherwise inaccessible targets in any zone of conflict.”

Lets ignore for a moment that the justification used for most nuclear and advanced conventional weapons also is to destroy otherwise inaccessible targets, what are actually the unique LRSO targets? In theory the missile could be used against anything that is within range but that is not good enough to justify spending $20-$30 billion.

So Air Force officials have portrayed the LRSO as a unique weapon that can get in where nothing else can. The mission they describe sounds very much like the role tactical nuclear weapons played during the Cold War: “I can make holes and gaps” in air defenses, then Air Force Global Strike Command commander Lieutenant General Stephen Wilson explained in 2014, “to allow a penetrating bomber to get in.”

And last week, shortly before Admiral Haney failed to convince Sen. Feinstein, EUCOM commander General Philip Breedlove added more details about what they want to use the nuclear LRSO to blow up:

“One of the biggest keys to being able to break anti-access area denial [A2AD] is the ability to penetrate the air defenses so that we can get close to not only destroy the air defenses but to destroy the coastal defense cruise missiles and the land attack missiles which are the three elements of an A2AD environment. One of the primary and very important tools to busting that A2AD environment is a fifth generation ability to penetrate. In the LRSB you will have a platform and weapons that can penetrate.” (Emphasis added.)

Those A2/AD targets would include Russian S-400 air-defense, Russian Bastion-P coastal defense, and Chinese DF-10A land-attack missile launchers (see images).

Judging from Sen. Feinstein’s conclusion that the LRSO seems “designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war,” Admiral Haney probably described similar LRSO targets as Lt. Gen. Wilson and Gen. Breedlove.

After hearing these “shocking” descriptions of the LRSO’s warfighting mission, Senator Feinstein asked NNSA’s Gen. Klotz if he could do a better job in persuading her about the need for the new nuclear cruise missile:

Sen. Feinstein: “So maybe you can succeed where Admiral Haney did not. Let me ask you this question: Why do we need a new nuclear cruise missile?”

Gen. Klotz: “My sense at the time, and it still is the case, is that the existing cruise missile, the air-launched cruise missile, is getting rather long in the tooth with the issues that are associated with an aging weapon system. It was first deployed in 1982. And therefore it is well past it service life. In the meantime, as you know from your work on the intelligence committee, there has been an increase in the sophistication and capabilities as well as proliferation of sophisticated air- and missile-defenses around the world. Therefore the ability of the cruise missile to pose the deterrent capability, the capability that is necessary to deter, is under question. Therefore, just based on the ageing and the changing nature of the threat we need to replace a system we’ve had, again, since the early 1980s with an updated variant….I guess I didn’t convince you any more than the Admiral did.”

Sen. Feinstein: “No you didn’t convince me. Because this just ratchets up warfare and ratchets up deaths. Even if you go to a low kiloton of six or seven it is a huge weapon. And I thought there was a certain morality that we should have with respect to these weapons. If it’s really mutual deterrence, I don’t see how this does anything other…it’s like the drone. The drone has been invented. It’s been armed. Now every county wants one. So they get more and more sophisticated. To do this with nuclear weapons, I think, is awful.”

Conclusion and Recommendations

Senator Feinstein has raised some important questions about the scope of nuclear strategy. How useful should nuclear weapons be and for what type of scenarios?

Proponents of the LRSO do not seem to question (or discuss) the implications of developing a nuclear cruise missile intended for shooting holes in air- and coastal-defense systems. Their mindset seems to be that anything that can be used to “bust the A2AD environment” – even a nuclear weapon – must be good for deterrence and therefore also for security and stability.

While a decision to authorize use of nuclear weapons would be difficult for any president, the planning for the potential use does not seem to be nearly as constrained. Indeed, the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission that defense officials describe raises some serious questions about how soon in a conflict nuclear weapons might be used.

Since A2AD systems would likely be some of the first targets to be attacked in a war, a nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission appears to move nuclear use to the forefront of a conflict instead of keeping nuclear weapons in the background as a last resort where they belong.

And the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission sounds eerily similar to the outrageous threats that Russian officials have made over the past several years to use nuclear weapons against NATO missile defense systems – threats that NATO and US officials have condemned. Of course, they don’t brandish the nuclear LRSO anti-A2AD mission as a threat – they call it deterrence and reassurance.

Nor do LRSO proponents seem to ask questions about redundancy and which types of weapons are most useful or needed for the anti-A2AD mission. The A2AD targets that the military officials describe are not “otherwise inaccessible targets,” as suggested by Secretary James, but are already being held at risk with conventional cruise missiles such as the Air Force’s JASSM-ER (extended range Joint Air-to-Surface Missile) and the navy’s Tactical Tomahawk, as well as with other nuclear weapons. The Air Force doesn’t have endless resources but must prioritize weapon systems.

Gen. Klotz defended the LRSO as if it were a choice between having a nuclear deterrent or not. But, of course, even without a nuclear LRSO, US stealth bombers will still be armed with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb and the US nuclear deterrent will still include land- and sea-based long-range ballistic missiles as well as F-35A stealthy fighter-bombers also armed with the B61-12.

The White House needs to rein in the nuclear warfighters and strategists to ensure that US nuclear strategy and modernization plans are better in tune with US policy to “reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks” and enable non-nuclear weapons to “take on a greater share of the deterrence burden.” Canceling the nuclear LRSO would be a good start.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Pentagon Portrays Nuclear Modernization As Response to Russia

By Hans M. Kristensen

The final defense budget of the Obama administration effectively crowns this administration as the nuclear modernization leader of post-Cold War U.S. presidencies.

While official statements so far have mainly justified the massive nuclear modernization as simply extending the service-life of existing capabilities, the Pentagon now explicitly paints the nuclear modernization as a direct response to Russia:

PB 2017 Adjusts to Strategic Change. Today’s security environment is dramatically different from the one the department has been engaged with for the last 25 years, and it requires new ways of thinking and new ways of acting. This security environment is driving the focus of the Defense Department’s planning and budgeting.

[…]

Russia. The budget enables the department to take a strong, balanced approach to respond to Russia’s aggression in Eastern Europe.

- We are countering Russia’s aggressive policies through investments in a broad range of capabilities. The FY 2017 budget request will allow us to modify and expand air defense systems, develop new unmanned systems, design a new long-range bomber and a new long-range stand-off cruise missile, and modernize our nuclear arsenal.

[…]

The cost for the new long-range bomber (LRS-B) is still secret but will likely total over 100 billion. But the new budget contains out-year numbers for the new cruise missile (LRSO) that show a significant increase in funding in 2018 and 2019. More than $4.6 billion is projected through 2021:

The total life-cycle cost of the new cruise missile may be as high as $30 billion. Excessive and expensive nuclear modernization programs in the budget threaten funding of more important non-nuclear defense programs.

The Pentagon and defense contractors say the LRSO is needed to replace the existing aging air-launched cruise missile (ALCM) to shoot holes in enemy air defenses, fight limited nuclear wars, and because Russia has nuclear cruise missiles. The claims recycle Cold War justifications and ignore the effectiveness of other military forces in deterring and defeating potential adversaries.

Last year Defense Secretary Carter promised NATO’s response to Russia would not use the “Cold War playbook” of large American forces stationed in Europe.

But other pages in the Cold War playbook – including those relating to nuclear forces – appear to have been studied well with growing nuclear bomber integration in Europe, revival of escalation scenarios and contingency planning, development of a new bomber and a cruise missiles, and deployment of guided nuclear bombs on stealth fighters in Europe within the next decade.

Russia – after having triggered a revival of NATO with its invasion of Ukraine, large-scale exercises, and overt nuclear threats – is likely to respond to NATO’s military posturing by beefing up its own operations. Russian officials quickly reacted to NATO’s latest announcement to boost military forces in Eastern Europe by pledging to improve its conventional and nuclear forces further.

It is obvious what’s happening here. The issue is not who’s to blame or who started it. The challenge is how to prevent that the actions each side take in what they consider justified responses to the other side’s aggression do not escalate further into a new round of Cold War.

The explicit inclusion of nuclear forces in the tit-for-tat posturing is another worrisome sign that the escalation has already started.

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

RAND Report Questions Nuclear Role In Defending Baltic States

By Hans M. Kristensen

The RAND Corporation has published an interesting new report on how NATO would defend the Baltic States against a Russian attack.

Without spending much time explaining why Russia would launch a military attack against the Baltic States in the first place – the report simply declares “the next [after Ukraine] most likely targets for an attempted Russian coercion are the Baltic Republics of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania” – the report contains some surprising (to some) observations about the limitations of nuclear weapons in the real world (by that I mean not in the heads of strategists and theorists).

The central nuclear observation of the report is that NATO nuclear forces do not have much credibility in protecting the Baltic States against a Russian attack.

That conclusion is, to say the least, interesting given the extent to which some analysts and former/current officials have been arguing that NATO/US need to have more/better limited regional nuclear options to counter Russia in Europe.

The report is very timely because the NATO Summit in Warsaw in six months will decide on additional responses to Russian aggression. Unfortunately, some of the decisions might increase the role or readiness of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Limits of Nuclear Weapons

The RAND report contains important conclusions about the role that nuclear weapons could play in deterring and repelling a Russian attack on the Baltic States. Here are the relevant nuclear-related excerpts from the report:

“Any counteroffensive would also be fraught with severe escalatory risks. If the Crimea experience can be taken as a precedent, Moscow could move rapidly to formally annex the occupied territories to Russia. NATO clearly would not recognize the legitimacy of such a gambit, but from Russia’s perspective it would at least nominally bring them under Moscow’s nuclear umbrella. By turning a NATO counterattack aimed at liberating the Baltic republics into an “invasion” of “Russia,” Moscow could generate unpredictable but clearly dangerous escalatory dynamics.”

[…]

“The second option would be for NATO to turn the escalatory tables, taking a page from its Cold War doctrine of “massive retaliation,” and threaten Moscow with a nuclear response if it did not withdraw from the territory it had occupied. This option was a core element of the Alliance’s strategy against the Warsaw Pact for the duration of the latter’s existence and could certainly be called on once again in these circumstances.

The deterrent impact of such a threat draws power from the implicit risk of igniting an escalatory spiral that swiftly reaches the level of nuclear exchanges between the Russian and U.S. homelands. Unfortunately, once deterrence has failed—which would clearly be the case once Russia had crossed the Rubicon of attacking NATO member states—that same risk would tend to greatly undermine its credibility, since it may seem highly unlikely to Moscow that the United States would be willing to exchange New York for Riga. Coupled with the general direction of U.S. defense policy, which has been to de-emphasize the value of nuclear weapons, and the likely unwillingness of NATO’s European members, especially the Baltic states themselves, to see their continent or countries turned into a nuclear battlefield, this lack of believability makes this alternative both unlikely and unpalatable.”

[…]

“We did not portray nuclear use in any of our games, although we did explore the effects of various kinds of constraints on each side’s operations intended to represent limitations that might be imposed by national or alliance political leaderships anxious to avoid setting off escalatory spirals.”

[…]

“Other options have been discussed to enhance NATO’s deterrent posture without significantly increasing its conventional force deployments. For example, NATO could rely on an increased availability and reliance on tactical and theater nuclear weapons. However, as recollections of the endless Cold War debates about the viability of nuclear threats to deter conventional aggression by a power that itself has a plethora of nuclear arms should remind us, this approach has issues with credibility similar to those already discussed with regard to the massive retaliation option in response to a Russian attack.”

Even So…

Not surprisingly, some analysts and former officials (even some current officials) are busy arguing – even lobbying for – that NATO and the United States need more tailored nuclear capabilities to be able to deter and, if necessary, respond to precisely the type of scenario the RAND study had doubts about.

There’s no doubt that Vladimir Putin’s escapades are creating security concerns in the Baltic States and NATO. The invasion of Ukraine, increased military operations, direct nuclear threats, and a host of less visible activities effectively have killed the trust between Russia and NATO. Relations have deteriorated to an officially adversarial and counter-responsive climate. It is in this atmosphere that analysts and nuclear hardliners are trying to understand how it affects nuclear weapons policy.

Hardliners are convinced that Russia has increased reliance on nuclear weapons in a whole new way that envisions first-use of nuclear weapons. One former official who helped shape the George W. Bush administration’s nuclear policy recently warned that Russia “seeks to prevent any significant collective Western defensive opposition by threatening limited nuclear first-use in response,” and that the Russian threat to use nuclear weapons first “is a new reality more dangerous than the Cold War.” (Emphasis added.)

That is probably a bit over the top. As for the claim that Russia is “pursuing” low-yield nuclear weapons to “make its first-use threat credible,” that rumor dates back to a number of articles in Russian media in the 1990s. Those rumors followed reports in the United States in 1993 that the Clinton administration was considering low-yield nuclear weapons – even “micro-nukes.” The Bush administration in the 2000s pursued pre-emptive nuclear strike scenarios and advanced-concept nuclear weapons for tailored use. Although Congress rejected these plans, some of the ideas seem to have influenced Russian nuclear thinking.

The US Air Force plans to deploy the new F-35A with the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb in Europe from 2024. The B61-12 will be more accurate than current bombs and appears to have earth-penetration capability.

Now we’re again hearing proposals from some analysts that the United States should develop a “measured response” strategy that includes “discriminate nuclear options at all rungs of the nuclear escalation ladder” to ensure that “there are no gaps in U.S. nuclear response options that would prevent it from retaliating proportionately to any employment of a nuclear weapon against the United States and its allies.” This would require “low-yield, accurate, special-effects options that can respond proportionately at the lower end of the nuclear continuum.”

It is easy to get spooked by public statements and led astray by entangled logic and worst-case scenarios that spin into claims and recommendations that may be based on misunderstood or exaggerated information. It would be more interesting and beneficial to the public debate to hear what the U.S. Intelligence Community has concluded Russia has developed and what is new and different in Russian nuclear strategy today.

A Better Strategy

Fortunately, Russia’s general military capabilities – although important – are so limited that the RAND study concludes that for NATO to be able to counter a Russian attack on the Baltic States “does not appear to require a Herculean effort.”

The LRSO, not yet developed, could pay for 10 years of real-world protection of the Baltic States.

Instead, the report concludes that a NATO force of about seven brigades, including three heavy armored brigades – adequately supported by airpower, land-based fires, and other enablers on the ground and ready to fight at the onset of hostilities – might prevent such an outcome.

NATO has already created a conventional Spearhead Force brigade of about 5,000 troops. Seven brigades of that size would include about 35,000 troops.

Creating and maintaining such a force, RAND estimates, might cost on the order of $2.7 billion per year.

Put in perspective, the $30 billion the Pentagon plans to spend on a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (LRSO) that is not needed could buy NATO more a decade worth of real protection of the Baltic States.

Guess what would help the Baltic States the most.

Background: Rand Report

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.