US Nuclear Stockpile Numbers Published Enroute To Hiroshima

The mushroom cloud rises over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, as the city is destroyed by the first nuclear weapon ever used in war.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Shortly before President Barack Obama is scheduled to arrive for his historic visit to Hiroshima, the first of two Japanese cities destroyed by U.S. nuclear bombs in 1945, the Pentagon has declassified and published updated numbers for the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile and warhead dismantlements.

Those numbers show that the Obama administration has reduced the U.S. stockpile less than any other post-Cold War administration, and that the number of warheads dismantled in 2015 was lowest since President Obama took office.

The declassification puts a shadow over the Hiroshima visit by reminding everyone about the considerable challenges that remain in reducing excessive nuclear arsenals – not to mention the daunting goal of eliminating nuclear weapons altogether.

Obama’s Stockpile Reductions

The declassified data shows that the stockpile as of September 2015 included 4,571 warheads. That means the Obama administration so far has reduced the stockpile by 702 warheads (or 13 percent) compared with the last count of the Bush administration.

Although 702 warheads is no small number (other than Russia, no other nuclear-armed state has more than 300 warheads), the reduction constitutes the smallest reduction of the stockpile achieved by any previous post-Cold War administration (see table).

The declassified 2015 number is about 100 warheads lower than the number we estimated in our latest Nuclear Notebook. The reason for the difference is that the number of warheads retired in 2014-2015 turned out to be higher than the average retirement in the previous three-year period. The increase probably reflects a quicker than anticipated retirement of excess warheads for the navy’s Trident missiles.

It can be deceiving to assess stockpile reduction performance by only comparing numbers of warheads. After all, there are significantly fewer warheads left in the stockpile today compared with 1991 (in fact, 14,437 warheads fewer!) so why wouldn’t the Obama administration be retiring fewer warheads than previous post-Cold War administrations?

To overcome that bias we also compare the reductions in terms of the percentage the stockpile size changed during the various administrations. But even so, the Obama administration’s performance comes in significantly below that of all other post-Cold War administrations (see table).

Obama’s Dismantlements

The declassified numbers also show that the Obama administration last year only dismantled 109 retired warheads. This is the lowest number of warheads dismantled in any year President Obama has been in office. And it appears to be the lowest number dismantled by the United States in one year since at least 1970.

The National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) says the poor performance in 2015 was due to “safety reviews, unusually high lightning events, and a worker strike at Pantex.”

But the decrease cannot be explained simply as disturbances. Although 2015 was unusually low, the Obama administration’s dismantlement record clearly shows a trendline of fewer and fewer warheads dismantled (see table).

Nuclear warhead dismantlement has decreased during the Obama administration. Click to view full size

There are currently roughly 2,300 retired warheads awaiting dismantlement, most of which were retired prior to 2009. NNSA says it plans to “increase weapons dismantlement by 20 percent starting in FY 2018” to be able to complete dismantlement of warheads retired prior to 2009 before the end of September 2021.

With the Obama administration’s average of about 280 warheads dismantled per year, it will take at least until 2024 before the total current backlog is dismantled. The several hundred additional warheads that will be retired before then will take several additional years to dismantle.

Yet in the same time period NNSA has committed to several other big warhead jobs that will compete with dismantlement work over the capacity at Pantex, including: complete production of the W76-1 by 2019, start up production of the B61-12 and W88 Alt 370 in 2020, preparation for the start up of the W80-4 in 2025, as well as the ongoing disassembly and reassembly for inspection of the existing warhead types in the stockpile.

Conclusion and Recommendations

President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima takes place in the shadow of his nuclear weapons legacy: he has reduced the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile less than any other post-Cold War president and nuclear warhead dismantlement has declined on his watch.

For the arms control community (and that includes several important US allies, including Japan) the Obama administration’s modest performance on reducing the number of nuclear weapons – despite the New START Treaty – is a disappointment. Not least because the administration’s nuclear weapons modernization program has been anything but modest.

To be fair, it is not all President Obama’s fault. His vision of significant reductions and putting an end to Cold War thinking has been undercut by opposition ranging from Congress to the Kremlin. An entrenched and almost ideologically opposed Congress has fought his arms reduction vision every step of the way. And the Russian government has rejected additional reductions while New START is being implemented (although we estimate Russia during the Obama administration has reduced its own stockpile by more than 1,000 warheads).

Ironically, although Congress is vehemently opposed to additional nuclear reductions – certainly unilateral ones, the modernization plan Congress has approved has significant unilateral nuclear reductions embedded in it: a reduction of nuclear gravity bombs by one-half, a reduction of 48 sea-launched ballistic missiles beyond what’s planned under the New START Treaty, and unilateral reduction in the late-2020s of excess W76 warheads.

The Air Force wants to build a new and better nuclear air-launched cruise missile even though the mission can be covered by conventional cruise missiles or other nuclear weapons. President Obama should cancel or delay the program and pursue a global ban on nuclear cruise missiles.

Curiously, there seems to have been less resistance to stockpile reductions from the U.S. military. The Pentagon’s Defense Strategic Guidance from 2012, for example, concluded: “It is possible that our deterrence goals can be achieved with a smaller nuclear force, which would reduce the number of nuclear weapons in our inventory as well as their role in U.S. national security strategy.”

Likewise, the Pentagon’s Nuclear Employment Strategy report sent to Congress in 2013 concluded that the nuclear force levels in place when the New START Treaty is fully implemented in 2018 “are more than adequate for what the United States needs to fulfill its national security objectives,” and that the United States “can ensure the security of the United States and our Allies and partners and maintain a strong and credible strategic deterrent while safely pursuing up to a one-third reduction in deployed nuclear weapons from the level established in the New START Treaty.”

And despite a significant turn for the worse in East-West relations, Russia is not increasing its nuclear arsenal but continuing to reduce it. But even if President Vladimir Putin decided to break out from the New START Treaty, the Pentagon concluded in 2012, Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” (Emphasis added.)

Those conclusions reveal a significant excess capacity in the U.S. nuclear arsenal that provides plenty of room for President Obama to do more in Hiroshima than simply remind of the dangers of nuclear weapons and reiterate the long-term vision of a world without them. Steps that he could and should take before leaving office include:

- Cancel plans to build a new nuclear air-launched cruise missile (the LRSO) or delay the plans as part of a focused effort to get international support for a global ban on nuclear cruise missiles;

- Retire now the majority of the gravity bombs scheduled to be retired in mid/late-2020s;

- Reduce now the number of ballistic missiles on U.S. strategic submarines to the lower number already planned for the Ohio replacement submarine in the 2030s;

- Retire now the excess sea-launched ballistic missile warheads scheduled to be retired in the mid/late-2020s;

- Reduce the ICBM force below the 400 planned under New START, probably to 300 as recommended by STRATCOM when Obama first took office;

- Reduce the alert level of U.S. nuclear forces to reduce risk of accidents and incidents, motivate Russia to also reduce its alert level, and to pave the way for an international effort to prevent other nuclear-armed states from increasing the readiness of their nuclear forces.

These actions would help bring U.S. nuclear policy back on track, remove excess capacity in the nuclear arsenal, restore the credibility of its arms control policy, retain a Triad of long-range nuclear forces, provide plenty of reassurance to allies and friends, maintain strategic stability, and free up resources for conventional forces. If Obama doesn’t do it, President Hillary Clinton will have to clean up after him.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Pentagon Report And Chinese Nuclear Forces

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Pentagon’s latest annual report on Chinese military developments mainly deals with non-nuclear issues, but it also contains important new information about developments in China’s nuclear forces. This includes:

- The size of China’s ICBM force has been relatively stable over the past five years

- China has deployed a new version of a medium-range ballistic missile

- A new intermediate-range ballistic missile is not yet deployed

- China’s SSBN fleet has yet to conduct its first deterrent patrol

- The possibility of nuclear capability for Chinese bombers

- Changes (or not) to Chinese nuclear policy

ICBM Developments

The future development of China’s ICBM force has been the subject of much speculation and projections over the years. Despite important new developments, this year’s report describes the size of the ICBM force as consistent with the force level reported over the past five years: around 60 launchers. Fielding of the DF-31 appears to have stalled and the data suggests that fielding of the DF-31A has been modest: so far about 20-30 launchers, enough for perhaps 4-5 brigades (see graph).

In 2012, the DOD report predicted that by 2015, “China will also field additional road-mobile DF-31A” launchers. But that doesn’t seem to have happened. Instead, the ICBM launcher force has remained relatively stable since 2011.

The number of I CBM launchers reported by the annual DOD reports over the past 13 years has fluctuated considerably, from around 30 in 2003 to 50 to 60-plus launchers in 2008 and later years. The uncertainty has been greatest in 2011-2013 and 2016 with a plus/minus of 25 launchers. That’s a significant uncertainty of approximately 40 percent in recent years versus around 10 percent in earlier years. But it seems clear that the Chinese ICBM forces is so far not continuing to grow.

CBM launchers reported by the annual DOD reports over the past 13 years has fluctuated considerably, from around 30 in 2003 to 50 to 60-plus launchers in 2008 and later years. The uncertainty has been greatest in 2011-2013 and 2016 with a plus/minus of 25 launchers. That’s a significant uncertainty of approximately 40 percent in recent years versus around 10 percent in earlier years. But it seems clear that the Chinese ICBM forces is so far not continuing to grow.

While the number of launchers has been relatively stable, the DOD report shows a mysterious increase of missiles for those launchers: 75-100 missiles for 50-75 launchers. This is inconsistent with previous DOD reports, which have either listed the same number of launchers and missiles, or a slightly higher number of missiles because of a reload capability of the old DF-4 (see table).

It is unclear why the 2016 report suddenly increases the number of missiles to 25 more than the number of launchers. Neither the DF-5 nor the DF-31/31A ICBMs are thought to have reloads. Past DOD reports that included missile estimates always listed one reload for the DF-4, not any other system. With only about 10 DF-4 launchers left in the arsenal, the number of extra missiles in 2016 should probably be 10, not 25 (the 25 would fit better if there were two reloads for the DF-4). As far as I can tell, here is what the Chinese ICBM force looks like:

Despite many rumors in the public debate that China has developed or is developing rail-based versions of its ICBMs, there is no mentioning in the DOD report of any rail-based system. Here is out latest overview of Chinese nuclear forces. An update will be published in July.

DF-26 Nuclear Precision Strike?

China’s newest nuclear-capable missile, the DF-26 (DOD provides no CSS designation for the new missile) that was unveiled during the September 2015 parade in Beijing, appears not to have been deployed with missile units yet.

Sixteen six-axel launchers were displayed during the parade and described as the official commentator as nuclear-capable. The missile is not yet deployed. Image: PLA.

The DOD report states that the DF-26, if it uses the same guidance for the nuclear and the conventional payloads, “would give China its first nuclear precision strike capability against theater targets.”

This statement indicates that DOD does not believe that any of China’s other nuclear-capable missiles have precision strike capability.

A New DF-21 Version?

The DOD report also lists a new version of the nuclear medium-range DF-21 missile but provides no details. The new version is called DF-21 Mod 6, or CSS-5 Mod 6 as it is listed in the report.

The DOD report says China has deployed a new version of the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile. Here a DF-21 takes part in a nuclear strike exercise in 2015. Image: PLA via CCTV-13.

The previous report from 2015 stated that the ICBM force was complemented by the “road-mobile, solid-fueled CSS-5 (DF-21) MRBM for regional deterrence missions.” The 2016 report, however, states that the ICBM force “is complemented by road-mobile, solid-fueled CSS-5 Mod 6 (DF-21) MRBM for regional deterrence missions,” the first time the Mod 6 designation has been used.

DOD does not provide any details about what the Mod 6 version is and to what extent it affects the status of the two original nuclear versions (Mod 1 and Mod 2). The original versions are getting old, so one possibility might be that the Mod 6 version is intended to replace them. But it is unclear what the status is.

DF-21 holds a special status in the history of Chinese forces because it was the first real mobile solid-fuel missile that replaced the old and more cumbersome liquid-fuel missiles. The Mod 1 was first fielded in the late-1980s although deployment didn’t really get underway until 1992. The Mod 2 was “not yet deployed” in 1998, according to NASIC, but both versions were listed as deployed by 2000. That was also the case in 2013, which suggest that the two versions might not be that different (perhaps range is the only difference), or that they are different but both retained for specific missions.

There is a lot of confusion about the different versions of the DF-21 in the public debate where many authors re-use secondary sources instead of relying on the original reference material. The most common mistake is to refer to the DF-21C conventional land-attack version as the CSS-5 Mod 3 and the DF-21D anti-ship version as the CSS-5 Mod 4. Over the years, DOD and the U.S. Intelligence Community have reported the following versions of the DF-21 medium-range ballistic missile:

DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 1): nuclear

DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2): nuclear

DF-21C (CSS-5 Mod 4): conventional land-attack

DF-21D (CSS-5 Mod 5): conventional anti-ship

DF-21 (CSS-5 Mod 6): nuclear (new)

It is not clear what happened to DF-21B and/or CSS-5 Mod 3. In any case, the DF-21 has now completely replaced the old liquid-fuel DF-3As that dominated the Chinese regional nuclear deterrence posture since the early-1970s. The last brigade to convert to DF-21 possibly was the 810 Brigade at Dengshahe in Liaoning province.

About That Credible Sea-Based Deterrent

It seems that various news media reports and official statement continue to exaggerate or preempt the operational capability of the Chinese submarine force. Many have said the new Jin-class SSBNs had begun conducting deterrent patrols, but the DOE report seems to indicate that the subs (or rather, their missiles) are not yet fully operational.

In February 2015, for example, the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations, Vice Admiral Joseph Mulloy, reportedly told Congress that one SSBN had gone on a 95-day patrol. Later, STRATCOM Commander Admiral Cecil Haney said SSBNs had been at sea but that he didn’t know if they had nukes on board but had to assume they did.

In contrary to these statements, the DOD report states the Jin-class SSBN “will eventually carry” the JL-2 SLBM (apparently it doesn’t yet do so) and that “China will probably conduct its first SSBN nuclear deterrence patrol sometime in 2016.” So apparently not yet.

This “not quite yet” assessment was supported by the Defense Intelligence Agency saying “the PLA Navy deployed the JIN-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine in 2015, which, when armed with the JL-2 SLBM, provides Beijing its first sea-based nuclear deterrent.” (Emphasis added.)

So one or more SSBNs might have sailed on some kind of deployment, but not necessarily with nuclear weapons onboard. All four operational Jin SSBNs are based at Longpo (Yulin) Submarine Base on Hainan Island, along with two Shang-class nuclear-powered attack submarines. A fifth Jin SSBN is under construction.

The DOD report also seems to debunk a rumor that China is building up to five additional Jin-class SSBNs. The head of US Pacific Command in 2015 told Congress that in addition to the submarines already launched, “up to five more may enter service by the end of the decade.” That seems to have been a fluke. The DOD report says a fifth Jin is under construction after which China will probably move on to a next-generation SSBN (Type 096) armed with a new missile (JL-3).

Nuclear Bombers?

The DOD report for the first time raises the issue of a potential nuclear role for the bombers. It does so by referencing various Chinese writings but without presenting a clear U.S. Intelligence Community conclusion about such a capability:

A thermonuclear bomb is dropped from an H-6 bomber in June 1967.

“In 2015, China also continued to develop long-range bombers, including some Chinese military analysts have described as “capable of performing strategic deterrence”—a mission reportedly assigned to the PLA Air Force in 2012. There have also been Chinese publications indicating China intends to build a long-range “strategic” stealth bomber. These media reports and Chinese writings suggest China might eventually develop a nuclear bomber capability. If it does, China would develop a “triad” of nuclear delivery systems dispersed across land, sea, and air—a posture considered since the Cold War to improve survivability and strategic deterrence.”

Chinese bombers are normally not considered to have an active nuclear role and the “strategic deterrence” mission assigned to PLAA in 2012 could potentially also reflect the introduction of conventional land-attack cruise missiles on the modified H-6K bomber. Yet a US Air Force Global Strike command briefing in 2013 listed the new CJ-20 air-launched land-attack cruise missile carried by the H-6K as nuclear-capable.

And China in the past certainly developed the capability to deliver nuclear weapons from bombers. Between 1965 and 1979, bombers delivered the nuclear weapon for at least 12 of China’s nuclear test explosions. These tests involved both fission and thermonuclear weapons with yields ranging from 5-10 kilotons, a few hundred kilotons, to 2-4 megatons. The bombs were delivered by H-6 bombers (still in service and being modernized), H-5 bombers (retired), and Q-5 fighter-bombers (nearly all retired).

The Military Museum in Beijing apparently has on display models of at least two nuclear bomb designs: a fission bomb and a hydrogen bomb. This video shows what is said to be China’s first test of a thermonuclear bomb, delivered by an H-6 bomber in June 1967.

Two nuclear bomb models are displayed in Beijing, the first fission bomb (left) and the first thermonuclear bomb (right). The marking on the thermonuclear bomb H639-23 is similar to those on the bomb used in the nuclear test on June 17, 1967: H639-6. Image: news.cn

Nuclear Policy and Strategy

Finally, the DOD report also summarizes the US understanding of Chinese nuclear policy and strategy.

The first is that the PLA has deployed new command, control, and communications capabilities to its nuclear forces to improve control of multiple units in the field. “Through the use of improved communications links,” DOD concludes, “ICBM units now have better access to battlefield information and uninterrupted communications connecting all command echelons. Unit commanders are able to issue orders to multiple subordinates at once, instead of serially, via voice commands.”

This is intended to improve control of the units but also to enhance their combat effectiveness in a crisis situation. To that end the DOD report mentions recent press accounts that China “may be enhancing peacetime readiness for nuclear forces to ensure responsiveness.” Part of this debate reflects a report by Gregory Kulacki citing Chinese military documents and statements that the nuclear forces may move towards a “launch-on-warning” posture to be able to launch missiles before they can be destroyed.

Despite these problematic developments, the DOD report concludes that there are no signs that China’s no-first-use policy and negative security assurance have been changed.

In other words, while Chinese nuclear policy itself does not appear to have changed, the way China deploys and operates its nuclear forces appears to be evolving significantly.

Additional resources:

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

President’s Message: Reinvention and Renewal

From its inception 70 years ago, the founders and members of the Federation of American Scientists were reinventing themselves. Imagine yourself as a 26-year old chemist having participated in building the first atomic bombs. You may have joined because your graduate school adviser was going to Los Alamos and encouraged you to come. You may also have decided to take part in the Manhattan Project because you believed it was your patriotic duty to help America acquire the bomb before Nazi Germany did. And even when Hitler and the Nazis were defeated in May 1945, you continued your work on the bomb because the war with Japan was still raging in the Pacific. Moreover, by then, you may have felt like Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the Scientific Director, that the project was “technically sweet”—you had to see it through to the end.

But when the end came—the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—in August 1945, you may have had doubts about whether you should have built the bombs, or you may have at least been deeply concerned about the future of humanity in facing the threat of nuclear destruction. What should you then do? About a thousand of the “atomic scientists” throughout the country at various sites, such as Los Alamos, Oak Ridge, Hanford, and Chicago began to organize and discuss the implications of this new military technology.1

This political activity was not natural for scientists. Almost all of the founders of FAS were so-called “rank-and-file” scientists in their 20s and 30s. Members of this youth brigade—led by Dr. Willie Higinbotham, who was in his mid-30s but who looked younger—arrived in Washington. With their “crew cuts, bow ties, and tab collars [testifying] to their youth,” they roamed the halls of Capitol Hill, educating Congressmen and their staffs.2 Newsweek called them the “reluctant lobby.” As a history of the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) notes, “Part of their reluctance stemmed from their conviction that the cause of science should not be dragged through the political arena.”3

Fortunately, these scientists persisted and achieved the notable result of successfully lobbying for civilian control of the AEC. While they also wanted international control of nuclear energy, they fell short of that goal. However, they were indefatigable in their educational efforts on promoting peaceful uses of nuclear energy and warning about the dangers of nuclear arms races.

Throughout FAS’s seven decades, the organization has transformed itself into various incarnations depending on the issues to be addressed and the resources available for operating FAS. To learn about this continual reinvention, I invite you to read all the articles in this special edition of the Public Interest Report. This edition has an all-star list of writers—many of whom have served in leadership roles at FAS and others who have deep, scholarly knowledge of FAS. These authors discuss many of the accomplishments of FAS, but they also do not shy away from mentioning several of the challenges faced by FAS.

What will FAS achieve and what adversities will occur in the next 70 years? As scientists know, research results are difficult, if not impossible, to predict. However, we do know that the mission of FAS is as relevant as ever, perhaps even more so than it was 70 years ago. Nuclear dangers—the founding call to action—have become more complex; instead of one nuclear weapon state in 1945, there are now nine countries with nuclear arms. Instead of a few nuclear reactors in 1945, today there are more than 400 power reactors in 31 countries and more than 100 research reactors in a few dozen countries. Moreover, some non-nuclear weapon states have acquired or want to acquire uranium enrichment or reprocessing facilities that can further sow the seeds of future proliferation of nuclear weapons programs. For these dangers alone, FAS has the important purpose to serve as a voice for scientists, engineers, and policy experts working together to develop practical means to reduce nuclear risks.

FAS has also served and will continue to serve as a platform for innovative projects that shine spotlights on government policies that work and don’t work and how to improve these policies. In particular, for a quarter century, the Government Secrecy Project, directed by Steve Aftergood, has worked to reduce the scope of official secrecy and to promote public access to national security information.

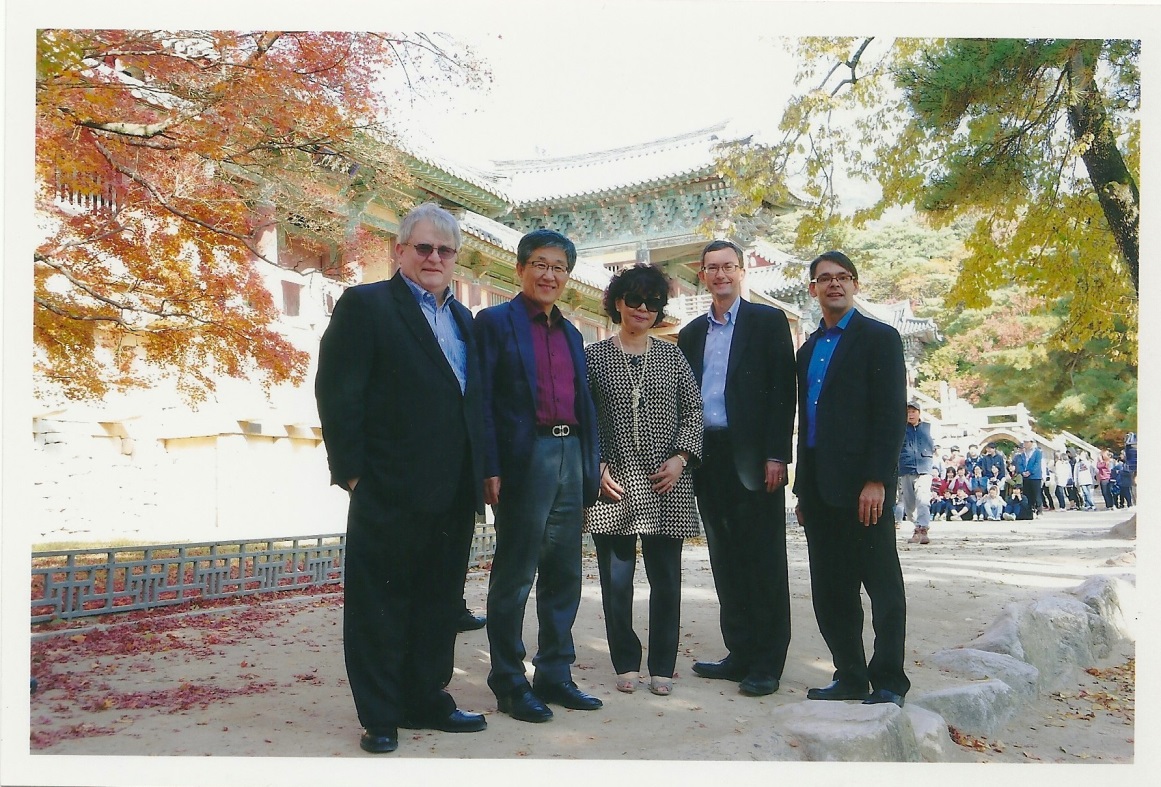

Nuclear energy research travel (cosponsored by FAS) to the Republic of Korea, November 7, 2013, taken at Gyeongju National Museum: From left to right: Paul Dickman, Argonne National Laboratory, Lee Kwang-seok, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute, Florence Lowe-Lee, Global America Business Institute, Everett Redmond, Nuclear Energy Institute, and Charles D. Ferguson, FAS.

FAS has also contributed to the public debate on bio-safety and bio-security. Daniel Singer (one of the contributors to this issue) and Dr. Maxine Singer have been active for more than 50 years in bio-ethics. Dr. Barbara Hatch Rosenberg and Dorothy Preslar in the 1990s and early 2000s worked through FAS to develop methods (such as an email list serve, which was cutting edge in the 1990s) to connect biologists and public health experts around the globe to identify, monitor, and evaluate emerging diseases. In recent years, Chris Bidwell, Senior Fellow for Law and Nonproliferation Policy, has led projects examining potential biological attacks or outbreaks and the forensic evidence needed for a court of law or government decision making in countries in the Middle East and North Africa. The Nuclear Information Project, directed by Hans Kristensen, continues its longstanding work on providing the public with reliable information and analysis on the status and trends of global nuclear weapons arsenals. Its famed Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, a senior fellow at FAS, is one of the most widely referenced sources for consistent data about the status of the world’s nuclear weapons.

I believe the greatest renewal and reinvention of FAS has been emerging in the past three years with the creation of networks of experts to work together to prevent threats from becoming global catastrophes. FAS has organized task forces that have provided practical guidance to policy makers about the implementation of the agreement on Iran’s nuclear program and that have examined the benefits and risks of the use of highly enriched uranium in naval nuclear propulsion. As I look to the next 70 years, I foresee numerous opportunities for FAS to seize by being the bridge between the technical and policy communities.

I am very grateful for the support of FAS’s members and donors and encourage you to invite your friends and colleagues to join FAS. Happy 70th anniversary!

The Legacy of the Federation of American Scientists

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) formed after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, precisely because many scientists were genuinely concerned for the fate of the world now that nuclear weapons were a concrete reality. They passionately believed that, as scientific experts and citizens, they had a duty to educate the American public about the dangers of living in the atomic age. Early in 1946, the founding members of FAS established a headquarters in Washington, D.C.,and began to coordinate the political and educational activities of many local groups that had sprung up spontaneously at universities and research facilities across the country. The early FAS had two simultaneous goals: the passage of atomic energy legislation that would ensure civilian control and promote international cooperation on nuclear energy issues, and the education of the American public about atomic energy. In addition, from its very inception, FAS was committed to promoting the broader idea that science should be used to benefit the public. FAS aspired, among other things, “To counter misinformation with scientific fact and, especially, to disseminate those facts necessary for intelligent conclusions concerning the social implications of new knowledge in science,” and “To promote those public policies which will secure the benefits of science to the general welfare.”

Scientists and Nuclear Weapons, 1945-2015

On August 8, 2015, twenty-nine scientists sent a letter to President Obama in support of the agreement with Iran that would block (or at least significantly delay) Iran’s pathways to obtain nuclear weapons. This continues a tradition that began seventy years ago of scientists having a role in educating the public, advising government officials, and helping shape policy about nuclear weapons.

Soon after the end of World War II, scientists mobilized themselves to address the pressing issues of how to deal with the many consequences of atomic energy. Of prime importance was the question of which government entity would control the research, development and production of atomic weapons, and any peaceful applications. Would it be the military, as it was during World War II, or a civilian agency, such as the newly created Atomic Energy Commission (AEC)?

FAS History, 1961-1963

“I was chairman of FAS from 1962-63. Fifty-year-old memories are hopelessly unreliable and historically worthless. Fortunately, my mother preserved the letters that I wrote to her describing events as they happened. The letters are reliable and give glimpses of history undistorted by hindsight. Instead of trying to recall fading memories, I decided to quote directly from the letters. Here are two extracts. The first describes an FAS Council meeting in 1961 before I became chairman. The second describes conversations in 1962 after I became chairman…”

FAS in the 1960s: Formative Years

“I am sharing some memories of the period 1960-1970 when I served as FAS General Counsel. I start by echoing Freeman Dyson’s caution that 50-year old memories are unreliable. I first learned about FAS in late 1958 when my wife, Dr. Maxine Singer, a molecular biologist employed by NIH, shared with colleagues her concerns about a range of science-related public issues. I was then a young lawyer in the small DC office of a larger NY-based general practice firm; the DC office had substantial experience representing, among many other clients, American Indian tribes in matters before Federal agencies and on Capitol Hill. At that time, FAS volunteers published a newsletter 8-10 times a year to keep its members (approximately 2000) informed about matters of concern to scientists – e.g., radiation hazards, nuclear weapons, passport denials, government secrecy, loyalty oaths, and civil liberties for scientists – in anticipation that scientists would take direct policy to influence governmental action. For several years, the FAS Newsletter was assembled on our dining room table and, willy-nilly, I became part of the process…”

Read on: View the full version of the article here.

Revitalizing and Leading FAS: 1970-2000

“When, in 1970, I descended from the FAS Executive Committee to become the chief executive officer, FAS had 1,000 members and an annual budget of $7,000 per year. The organization was very near death. During my 30 year tenure, FAS became a famous, creative, and productive organization….”

FAS’s Contribution to Ending the Cold War Nuclear Arms Race

by Frank von Hippel

“When, at Jeremy Stone’s instigation, I was elected chair of the Federation of American Scientists in 1979, I had no idea what an adventure that I was about to embark upon. This adventure was triggered by President Reagan taking office in 1981 and resulted in FAS making significant contributions to ending the U.S.-Soviet nuclear arms race and the Cold War. This was not the President Reagan we remember now as the partner of Mikhail Gorbachev in ending the Cold War. This was a president who had been convinced by the Committee on the Present Danger that the United States was falling behind in the nuclear arms race and was in mortal danger of a Soviet first nuclear strike…”

FAS Engagement With China

“Supporting and expanding on Frank von Hippel’s cogent and exciting narrative of some of the great accomplishments of the Federation of American Scientists, I detail below two endeavors, at least one of which may have had far-reaching impact. The first was the initiative of FAS Director (and later President) Jeremy J. Stone who, in 1971, wrote the president of the Chinese Academy of Sciences to introduce FAS and to begin some kind of dialogue…”

Nuclear Legacies: Public Understanding and FAS

“In late 1945, a group of scientists who had been involved with the Manhattan Project felt it was their civic duty to help inform the public and political leaders of both the potential benefits and dangers of nuclear energy. To facilitate this important work, they established the Federation of Atomic Scientists, which soon became the Federation of American Scientists. Over the years, FAS has evolved into a model non-governmental organization that plays a leading role in providing scientifically-sound, non-partisan analyses of nuclear and broader security issues. I have long admired FAS and was therefore deeply honored when President Charles D. Ferguson asked if I would be interested in preparing a brief essay for a special edition of the PIR that would commemorate the organization’s 70th anniversary. A period of mild apprehension then followed: What could I say on the relationship between science and society that had not been said a thousand times before?”

FAS Nuclear Notebook Published: Russian Nuclear Forces, 2016

By Hans M. Kristensen

By Hans M. Kristensen

In our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Norris and I take the pulse on Russia’s nuclear arsenal, reviewing its strategic modernization programs and the status of its non-strategic nuclear forces.

Despite what you might read in the news media and on various web sites, the Russian modernization is not a “buildup” but a transition from Soviet-era nuclear weapons to newer and more reliable types on a less-than-one-for-one basis.

As a result, the Russian nuclear arsenal will likely continue to decline over the next decade – with or without a new arms control agreement. But the trend is that the rate of decline is slowing and Russian strategic nuclear forces may be leveling out around 500 launchers with some 2,400 warheads.

Because Russia has several hundred strategic launchers fewer than the United States, the Russian modernization program emphasizes deployment of multiple warheads on ballistic missiles to compensate for the disparity and maintain rough parity in overall warhead numbers. Before 2010, no Russian mobile launcher carried multiple warheads; by 2022, nearly all will.

As a result, Russia currently has more nuclear warheads deployed on its strategic missiles than the United States. But not by many and Russia is expected to meet the limit set by the New START treaty by 2018.

Russia to some extent also uses its non-strategic nuclear weapons to keep up. But non-strategic nuclear forces have unique roles that appear to be intended to compensate for Russia’s inferior conventional forces, which – despite important modernization such as long-range conventional missiles – are predominantly made up of Soviet-era equipment or upgraded Soviet-era equipment.

Russia’s non-strategic nuclear forces are currently the subject of much interest in NATO because of concern that Russian military strategy has been lowering the threshold for when nuclear weapons could potentially be used. Russia has also been increasing operations and exercises with nuclear-capable forces, a trend that can also be seen in NATO and U.S. military posturing.

More information:

FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russian nuclear forces, 2016

Who’s Got What: Status of World Nuclear Forces

The research for this publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation, and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.