Increasing Nuclear Bomber Operations

CBS’s 60 Minutes program Risk of Nuclear Attack Rises described that Russia may be lowering the threshold for when it would use nuclear weapons, and showed how U.S. nuclear bombers have started flying missions they haven’t flown since the Cold War: Over the North Pole and deep into Northern Europe to send a warning to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The program follows last week’s program The New Cold War where viewers were shown unprecedented footage from STRATCOM’s command center at Omaha Air Base in Nebraska.

Producer Mary Welch and correspondent David Martin have produced a fascinating and vital piece of investigative journalism showing disturbing new developments in the nuclear relationship between Russia and the United States.

They were generous enough to consult me and include me in the program to discuss the increasing Cold War and dangerous military posturing.

Nuclear Bomber Operations Context

Just a few years ago, U.S. nuclear bombers didn’t spend much time in Europe. They were focused on operations in the Middle East, Western Pacific, and Indian Ocean. Despite several years of souring relations and mounting evidence that the “reset” with Russia had failed or certainly not taken off, NATO couldn’t make itself say in public that Russia gradually was becoming an adversary once again.

Whatever hesitation was left changed in March 2014 when Vladimir Putin sent his troops to invade Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The act followed years of Russian efforts to coerce the Baltic States, growing and increasingly aggressive military operations around European countries, and explicit nuclear threats against NATO countries getting involved in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

Granted, NATO may not have been a benign neighbor, with massive expansion eastward of new members all the way up to the Russian border, and a consistent tendency to ignore or dismiss Russian concerns about its security interests.

But whatever else Putin might have thought he would gain from his acts, they have awoken NATO from its detour in Afghanistan and refocused the Alliance on its traditional mission: defense of NATO territory against Russian aggression. As a result, Putin will now get more NATO troops along his western and southern borders, larger and more focused military exercises more frequently in the Baltic Sea and Black Sea, increasing or refocused defense spending in NATO, and a revitalization of a near-slumbering nuclear mission in Europe.

Six years ago the United States was this close to pulling its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons out of Europe. Only an engrained NATO nuclear bureaucracy aided by the Obama administration’s lack of leadership prevented the withdrawal of the weapons. Russia has complained about them for years but now it seems very unlikely that the modernization of the F-35A with the B61-12 guided bomb can be stopped. The weapons might even get a more explicit role against Russia, although this is still a controversial issue for some NATO members.

But the U.S. military would much prefer to base the nuclear portion of its extended deterrence mission in Europe on strategic bombers rather than the short-range fighter-bombers forward deployed there. The non-strategic nuclear weapons are far too controversial and vulnerable to the myriads of political views in the host countries. Strategic bombers are free of such constraints.

A New STRATCOM-EUCOM Link

Therefore, even before NATO at the Warsaw Summit this summer decided to reinvigorate its commitment to nuclear deterrence, former U.S. European Command (EUCOM) commander General Philip Breedlove told Congress in February 2015, EUCOM had already “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence [BAAD] missions to NATO regional exercises” as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve to deter Russia.

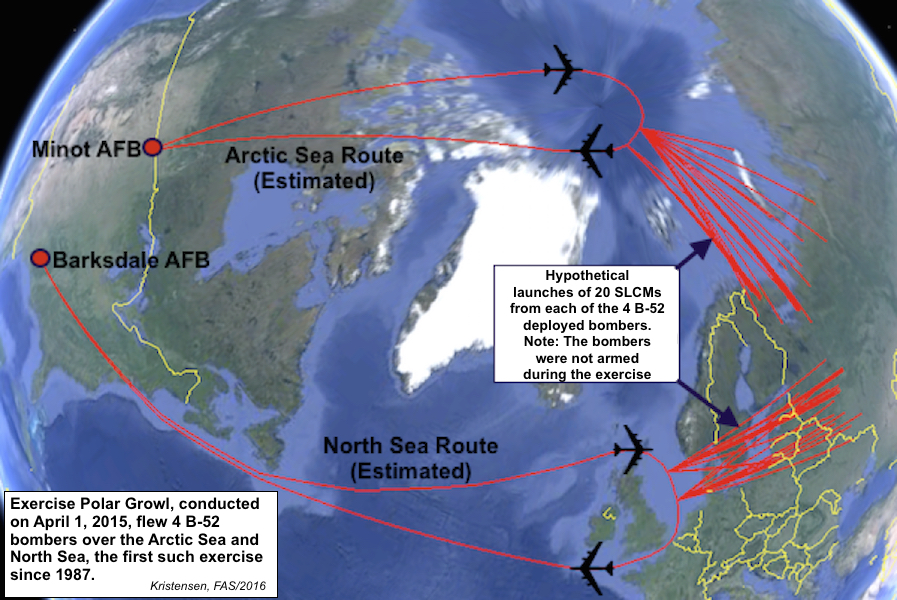

Less than two months later, on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers took of from their bases in the United States and flew across the North Pole and North Sea in a simulated strike exercise against Russia. The bombers proceeded all the way to their potential launch points for air-launched cruise missiles before they returned to the United States. Such an exercise had not been conducted since the late-1980s against the Soviet Union. Combined, the four bombers could have delivered 80 long-range nuclear cruise missiles with a combined explosive power of 800 Hiroshima bombs.

During Exercise Polar Growl on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers flew along two routes into the Arctic and North Sea regions that appeared to simulate long-range strikes against Russia. The four bombers were capable of launching up to 80 nuclear air-launched cruise missiles with a combined explosive power equivalent to 800 Hiroshima bombs. All routes are approximate.

Despite its strategic implications, Polar Growl also had a distinctive regional – even limited – objective because of the crisis in Europe. Planning for such regional deterrence scenarios have taken on a new importance during the past couple of decades and they have become central to current planning because it is in such regional scenarios that the United States believes it is most likely that nuclear weapons could actually be used.

“The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, in 2014 predicted only a few weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, “and continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.”

Two weeks after the bombers returned from Polar Growl, Robert Scher, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities, told Congress: “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts.” This includes “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

Nuclear Conventional Integration

Much of this increased planning involves conventional weapons such as the new long-range conventional JASSM-ER cruise missile, but the planning also involves nuclear. In fact, conventional and nuclear appear to be integrating in a way they have done before. This effort was described recently by Brian McKeon, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, during the annual STRATCOM Deterrence Symposium:

In the Department of Defense we’re working to effectively integrate conventional and nuclear planning and operations. Integration is not new but we’re renewing our focus on it because of recent developments and how we see potential adversaries preparing for conflict. This is an area where the focus in Omaha has really led the way and I want to commend Admiral Haney and STRATCOM for being able to shift planning so quickly toward this approach and thinking though conflict. No one wants to think about using nuclear weapons and we all know the principle role of nuclear weapons is to deter their use by others. But as we’ve seen, out adversaries may not hold the same view.

Let me be clear that when I say integration I do not mean to say we have lowered the threshold for nuclear use or would turn to nuclear weapons sooner in a conventional campaign. As we stated in the Nuclear Posture Review, the United States will “only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.” The NPR also emphasized the importance of reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, a requirement that has been advanced in our planning consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance, including with non-nuclear strike options.

What I mean by integration is synchronizing our thinking across all domains in a way that maximizes the credibility and flexibility of our deterrent through all phases of conflict and responds appropriately to asymmetrical escalation. For too long, crossing the nuclear threshold was through to move a nuclear conflict out of the conventional dimension and wholly into the nuclear realm. Potential adversaries are exploring ways to cross this threshold with low-yield nuclear weapons to test out resolve, capabilities, and Allied cohesion. We must demonstrate that such a strategy cannot succeed so that it is never attempted. To that end we’re planning and exercising our non-nuclear operations conscious of how they might influence an adversary’s decision to go nuclear.

We also plan for the possibility of ongoing U.S. and Allied operations in a nuclear environment and working to strengthen resiliency of conventional operations to nuclear attack. By making sure our forces are capable of continuing the fight following a limited nuclear use we preserve flexibility for the president. And by explicitly preparing for the implication of an adversary’s limited nuclear use and providing credible options for the President, we strengthen our deterrent and reduce the risk of employment in the first instance.

Regional nuclear scenarios no longer primarily involve planning against what the Bush administration called “rogue states” such as North Korea and Iran, but increasingly focus on near-peer adversaries (China) and peer adversaries (Russia). “We are working as part of the NATO alliance very carefully both on the conventional side as well as meeting as part of the NPG [Nuclear Planning Group] looking at what NATO should be doing in response to the Russian violation of the INF Treaty,” Scher explained.

STRATCOM last updated the strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) in 2012 and is currently about to publish an updated version that incorporates the changes caused by the Obama administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy from 2013.

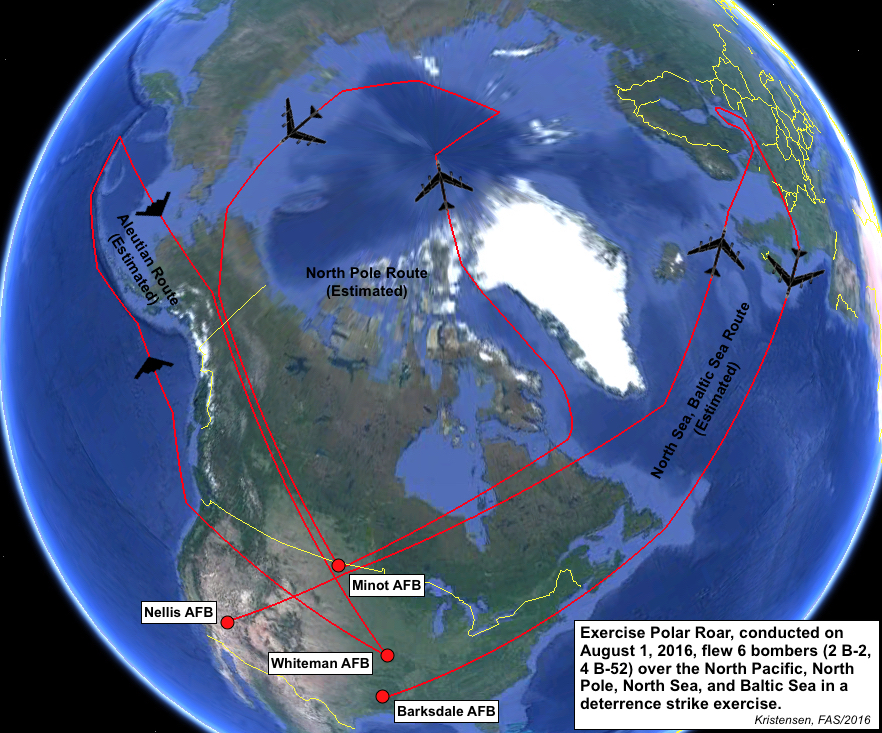

Two months ago, a little over a year after Polar Growl, another bomber strike exercise was launched. This time six bombers (4 B-52s and 2 B-2s) flew closer to Russia and simultaneously over the Arctic Sea, North Sea, Baltic Sea, and North Pacific Ocean. The six Polar Roar sorties required refueling support from 24 KC-135 tankers as well as E4-B Advanced Airborne Command Post and E-6B TACAMO nuclear command and control aircraft.

The routes (see below) were eerily similar to the Chrome Dome airborne alert routes that were flown by nuclear-armed bombers in the 1960s against the Soviet Union.

Exercise Polar Roar on August 1, 2016, followed Exercise Polar Growl from 2015 but involved more bombers, both nuclear-capable and conventional-only, and flew closer to Russia and deep into the Baltic Sea. Polar Roar also included B-2 stealth bombers in the North Pacific. All routes are approximate.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Seeking Verifiable Destruction of Nuclear Warheads

A longstanding conundrum surrounding efforts to negotiate reductions in nuclear arsenals is how to verify the physical destruction of nuclear warheads to the satisfaction of an opposing party without disclosing classified weapons design information. Now some potential new solutions to this challenge are emerging.

Based on tests that were conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission in the 1960s in a program known as Cloudgap, U.S. officials determined at that time that secure and verifiable weapon dismantlement through visual inspection, radiation detection or material assay was a difficult and possibly insurmountable problem.

“If the United States were to demonstrate the destruction of nuclear weapons in existing AEC facilities following the concept which was tested, many items of classified weapon design information would be revealed even at the lowest level of intrusion,” according to a 1969 report on Demonstrated Destruction of Nuclear Weapons.

But in a newly published paper, researchers said they had devised a method that should, in principle, resolve the conundrum.

“We present a mechanism in the form of an interactive proof system that can validate the structure and composition of an object, such as a nuclear warhead, to arbitrary precision without revealing either its structure or composition. We introduce a tomographic method that simultaneously resolves both the geometric and isotopic makeup of an object. We also introduce a method of protecting information using a provably secure cryptographic hash that does not rely on electronics or software. These techniques, when combined with a suitable protocol, constitute an interactive proof system that could reject hoax items and clear authentic warheads with excellent sensitivity in reasonably short measurement times,” the authors wrote.

See Physical cryptographic verification of nuclear warheads by R. Scott Kemp, et al,Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, published online July 18.

More simply put, it’s “the first unspoofable warhead verification system for disarmament treaties — and it keeps weapon secrets too!” tweeted Kemp.

See also reporting in Science Magazine, New Scientist, and Phys.org.

In another recent attempt to address the same problem, “we show the viability of a fundamentally new approach to nuclear warhead verification that incorporates a zero-knowledge protocol, which is designed in such a way that sensitive information is never measured and so does not need to be hidden. We interrogate submitted items with energetic neutrons, making, in effect, differential measurements of both neutron transmission and emission. Calculations for scenarios in which material is diverted from a test object show that a high degree of discrimination can be achieved while revealing zero information.”

See A zero-knowledge protocol for nuclear warhead verification by Alexander Glaser, et al, Nature, 26 June 2014.

But the technology of nuclear disarmament and the politics of it are two different things.

For its part, the U.S. Department of Defense appears to see little prospect for significant negotiated nuclear reductions. In fact, at least for planning purposes, the Pentagon foresees an increasingly nuclear-armed world in decades to come.

A new DoD study of the Joint Operational Environment in the year 2035 avers that:

“The foundation for U.S. survival in a world of nuclear states is the credible capability to hold other nuclear great powers at risk, which will be complicated by the emergence of more capable, survivable, and numerous competitor nuclear forces. Therefore, the future Joint Force must be prepared to conduct National Strategic Deterrence. This includes leveraging layered missile defenses to complicate adversary nuclear planning; fielding U.S. nuclear forces capable of threatening the leadership, military forces, and industrial and economic assets of potential adversaries; and demonstrating the readiness of these forces through exercises and other flexible deterrent operations.”

See The Joint Operating Environment (JOE) 2035: The Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World, Joint Chiefs of Staff, 14 July 2016.

New FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2016

By Hans M. Kristensen and Robert S. Norris

China’s nuclear forces are limited compared with those of Russia and the United States. Nonetheless, its arsenal is slowly increasing both in numbers of warheads and delivery vehicles.

In our latest FAS Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, we estimate that China has a stockpile of about 260 nuclear warheads for delivery by a growing diversity of land- and sea-based ballistic missiles and bombers.

Changes over the past year include fielding of the new dual-capable DF-26 road-mobile intermediate-rage ballistic missile, the reported fielding of a new nuclear version (Mod 6) of the DF-21 road-mobile medium-range ballistic missile, more flight-tests of the long-rumored DF-41 road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missile, and the slow readying of the Jin-class (Type 094) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines.

China is also modernizing its aging fleet of H-6 bombers, some of which may have a secondary nuclear role.

Although China is still thought to be fielding more DF-31A launchers, the overall number of ICBM launchers has not increased since 2011 but remained at 50-75 launchers. The oldest of these, the liquid-fuel DF-4, apparently has an extra load of missiles but is thought to be close to retirement. None of the new ICBMs are thought to have reloads.

ICBM Exercises and Force Level

Chinese television showed PLARF (PLA Rocket Force) videos of several exercises in late-2015 and early-2016 that included DF-4, DF-21 and DF-31 launchers.

One video showed what was said to be a Rocket Force exercise in northeast China in early 2016 that included a DF-31 launcher. The characteristic outline of the launch site made it possible for us (and many others) to identify the location as a launch unit site of the 816 Brigade at Tonghua in the Jilin province (see image below). The 816 Brigade is thought to be equipped with the DF-21 so the DF-31 exercise probably involved a launch unit on an extended deployment from another brigade.

A DF-31 or DF-31A launcher in exercise on launch pad near Tonghua in northeast China in early-2016. Image: CCTV13.

Although the liquid-fuel DF-4 ICBM is old and very slow as a retaliatory weapon, the single remaining brigade near Lingbao continued to conduct launch exercises in late-2015 and early-2016. One of these involved a roll-out-to-launch exercise from a missile garage of the 801 Brigade near Lingbao in Henan province (see image below). The DF-4 will likely be phased out in the near future.

A DF-4 launch unit near Lingbao held a roll-out-to-launch exercise in late-2015. Image: PLARF via CCTV-13.

Overall the number of Chinese ICBM launchers has been growing slowly since the mid-2000s. The DF-31 and its longer-range version DF-31A have been slowly fielding since 2006 and 2007, respectively, although the DF-31 seems to have stalled after less than 10 launchers. The DF-31A may still be fielding but not much. Since the mid-2000s, the introduction of these two systems has doubled the size of the Chinese ICBM force from around 30 to around 60. The force has been stable since 2011 (see image below).

Chinese ICBM launchers doubled between 2006 and 2011 but have remained steady since. Click to view full size.

There have also been several unconfirmed reports of a new DF-41 ICBM being test-launched, sometimes from rail cars. The Pentagon first predicted fielding of the long-rumored DF-41 in the late-1990s but then dropped references to the weapon system until two years ago when it stated that the missile might be capable of carrying MIRV warheads. Since then several photos of an eight-axel launcher have appeared on the Internet with unconfirmed claims that they showed the DF-41.

Once the DF-41 finally deploys, it will likely result in the retirement of the DF-4 and potentially also the liquid-fuel silo-based DF-5A/B, some of which have recently been equipped to carry MIRV.

DOD projections for the number of Chinese ICBM warheads that could threaten the United States have fluctuated over the years, generally promising too much too soon. Moreover, the projections have been inconsistent about whether they concerned warheads that could reach any part of the United States or just the continental United States. With the addition of MIRV to the DF-5B and potentially also on the future DF-41, the projections could potentially reach approximately 100 warheads in the foreseeable future (see graph below).

US agency projections for Chinese ICBM warheads have promised too much too soon. But with Chinese MIRVing of some ICBMs, the projections could potentially come true. Click to view full size.

IRBM/MRBM Developments

China is also boosting its force of medium- and inter-medium-range ballistic missiles for regional deterrence missions. The most important new development is the introduction of the new DF-26, an intermediate-range dual-capable road-mobile ballistic missile. Sixteen launchers were shown during the 2015 military parade but the system is probably still in its early stages of introduction.

The focus on missiles for regional deterrence missions is particularly clear in the fielding of several conventional versions of the solid-fuel DF-21 MRBM (DF-21C or CSS-5 Mod 4, and DF-21D or CSS-5 Mod 5). But the 2016 DOD report on Chinese military development also reports deployment of a new nuclear version of the DF-21, designated CSS-5 Mod 6. China already operates two older nuclear versions of the DF-21 (DF-21 or CSS-5 Mod 1, and DF-21A or CSS-5 Mod 2). It is unclear if the new Mod 6 version will be deployed alongside the two older versions or if it is intended to replace them.

More than 25 years after the DF-21 first began replacing the liquid-fuel DF-3A medium-range ballistic missile, the transition seems to be complete and the DF-3A finally retired. One of the bases where the transition has been visible is the 810 Brigade launch site near Dengshahe in the Liaoning province of northeast China. Commercial satellite images show the transition from DF-3A in 2003 to the DF-21 in 2014. A satellite image from April 2016 shows three DF-21 launchers positioned on the launch pads along with support vehicles (see image below).

The SSBN Fleet

China’s attempt to build an SSBN fleet has so far resulted in four Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs entering service. The US Navy says all four are based at the Longpo naval base on Hainan Island, although commercial satellite images have so far only shown three SSBNs at the base simultaneously.

The big question, which has generated lots of Internet rumors and news media articles, is whether the Jin fleet has yet conducted a deterrence patrol with nuclear-tipped JL-2 missiles onboard. We find that highly unlikely given the Chinese leadership’s reluctance to hand out nuclear weapons to the military services in peacetime. It is possible that one or more of the Jin subs have sailed on long voyages far from Chinese waters, but we haven’t seen credible sources reporting actual nuclear deterrent patrols yet.

Another area of speculation is how China will operate its SSBN fleet once it becomes fully operational. Most reports bluntly state that the Jin fleet will provide China with a secure second-strike capability. But that is an overstatement, given the technological, operational, and geographic challenges the Jin fleet faces. The Jin subs are as noisy [/blogs/security/2009/11/subnoise/] as submarines built by the Soviet Union back in the 1970s, the Chinese navy has almost no experience in operating nuclear-armed submarines, and the limited range of the JL-2 requires the submarine to sail far into dangerous waters to be able to hit targets in the United States.

ONI stated in 2015 [http://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/China_Media/2015_PLA_NAVY_PUB_Print.pdf?ver=2015-12-02-081247-687] that, once deployed, the Jin/JL-2 weapon system “will provide China with a capability to strike targets on the continental United States.” But that’s an overstatement. To reach targets on the continental United States, a Jin SSBN with JL-2 SLBMs would have to sail at least 3,600 kilometers (2,200 miles) from its base on Hainan Island into the Pacific Ocean just to be able to target Seattle (see image). Alaska and Guam could be hit from Chinese waters but Hawaii could not. Moreover, to target Washington, DC, a Jin SSBN would have to sail halfway across the Pacific Ocean.

Despite claims by many, including the US Navy, the JL-2 SLBM does not have sufficient range to target the continental United States.

We have analyzed the Chinese SSBN fleet for the past decade and frequently pointed out the tendency to overstate or exaggerate the capability of the Jin-class SSBNs and their missiles. The Jin-class fleet seems more like a work in progress that is intended to build technology and operational experience for the next generation SSBN: the Type 096.

Background: Chinese nuclear forces, 2016 (FAS Nuclear Notebook)

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

President’s Message: What Will the Next President’s Nuclear Policies Be?

The presidential candidates’ debates will soon occur, and the voters must know where the candidates stand on protecting the United States against catastrophic nuclear attacks. While debating foreign policy and national security issues, the Democratic and Republican candidates could reach an apparent agreement about the greatest threat facing the United States, similar to what happened on September 30, 2004. During that first debate between then President George W. Bush and then Senator John Kerry (now Secretary of State), they appeared to agree when posed the question: ”What is the single most serious threat to the national security to the United States?” Kerry replied, “Nuclear proliferation. Nuclear proliferation.” He went on to critique what he perceived as the Bush administration’s slow rate of securing hundreds of tons of nuclear material in the former Soviet Union.

When Bush’s turn came, he said, “First of all, I agree with my opponent that the biggest threat facing this country is weapons of mass destruction in the hands of a terrorist network. And that’s why proliferation is one of the centerpieces of a multi-prong strategy to make the country safer.”1 President Bush also mentioned that his administration had devoted considerable resources toward securing nuclear materials in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere.

Despite this stated agreement, the two candidates disagreed considerably on how to deal with nuclear threats. Today, the leading Democratic and Republican candidates appear to be in even further disagreement on this issue than Bush and Kerry, while nuclear dangers arguably look even more dangerous. I will not analyze each candidate’s views, especially because their views could change between the time of writing this president’s message in late June and the start of the debates in September. I think it is more useful here to outline several of the major themes on nuclear policy that should be addressed in the campaign and during the debates.

The most fundamental theme is: what is the role or roles of U.S. nuclear weapons? Deterrence is the easy answer, but against what or whom? That is, should nuclear weapons only be used when another nuclear-armed state uses them against the United States or U.S. allies or should the mission be expanded to include deterrence against massive biological attacks, for instance? Assuming the next president wants his policy team to elucidate that the sole purpose of nuclear weapons is solely for deterring others’ use of nuclear weapons, the next question is: should the United States have a no-first-use policy of not launching nuclear weapons before others launch nuclear weapons?

Such a policy would emphasize having nuclear weapons that would be secure against a nuclear attack that would come first from an enemy. For example, deployed submarines underneath the surface of the oceans would provide this type of secure force, whereas land-based nuclear-armed missiles and bombers could be more vulnerable to an incoming attack. Would the next president want to reduce the nuclear triad to a single leg of ballistic missile submarines? This decision would require considerable political courage and would have to withstand opposition from proponents who would want to keep the Air Force’s legs of the triad of intercontinental ballistic missiles and strategic bombers. However, the Air Force could transform its nuclear forces to have solely conventionally-armed missiles and bombers and in effect, it could have more militarily usable weapons that would not have to cross the high threshold of nuclear use.

Another argument for shifting to having just submarines deploy nuclear weapons is the cost savings from having to maintain nuclear arms for land-based missiles and bombers. This leads to the debate topic of whether the United States should spend up to $1 trillion in the coming decades on “modernizing” its nuclear forces. All three legs of the triad are showing their age. Each leg will require $100 billion or more to upgrade the launching platforms of missiles, bombers, and submarines, and in addition, there would be several $100 billion more in refurbishing and maintaining the half dozen types of nuclear warheads plus the related infrastructure costs. Would a presidential candidate seize the opportunity to save hundreds of billions of dollars by smartly downsizing U.S. nuclear forces?

The candidates would have to confront the promises made by the Obama administration to key Republican senators to “modernization” of the nuclear arsenal. This commitment was a crucial part of the bargain to convince enough Republican senators to vote in favor of the New START agreement with Russia in 2010. On June 17, 2016, Senator John McCain (R-Arizona) and Senator Bob Corker (R-Tennessee) sent a letter to President Obama to remind him of this commitment.2 Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and former Under Secretary of State Ellen Tauscher have called for Congress not to fund the proposed nuclear-armed cruise missile, known as the Long Range Standoff Weapon (LRSO), because: there is no compelling military need; it could lower the threshold of nuclear use; and it is too costly at an estimate of up to $30 billion.3

New START was a relatively modest reduction in strategic nuclear forces. The tough challenge for the next president is whether further reductions with Russia are even possible given the heightened tensions over Ukraine and other sticking points between Russia and NATO, as well as between Russia and the United States. Going much lower in numbers of strategic nuclear arms might require a rethinking of the nuclear weapons configurations in both nuclear superpowers. Thus, the next president will need a highly capable team who will understand U.S.-Russia relations, the concerns of certain NATO allies, the concerns of East Asian allies, namely Japan and South Korea, as well as the effect on China.

China has remained apart from nuclear arms reductions, although Chinese leaders have made their views clear that they want to ensure that China has a secure nuclear deterrent. While China has for decades been content to have a relatively small nuclear force, there have been signs in recent years of a buildup and modernization of Chinese nuclear weapons and associated delivery platforms, particularly the ballistic missile submarines that have recently demonstrated (after years of technical setbacks) the capability to deploy further out to sea and within striking range of the United States. The next president will have to wrestle with a host of political and military challenges from China, and in the nuclear area, he or she will have to determine how best to deter China without having China further buildup its nuclear arms.

A major issue of concern to China is the potential buildup of U.S. missile defense beyond just a relatively small number of missile interceptors. The ostensible purpose of this very limited U.S. missile defense system is to counter North Korean missiles and Iranian missiles, which are still relatively few in number in terms of longer range missiles. China has been concerned that even a limited or “small” missile defense system could threaten China’s capability to launch a retaliatory nuclear attack against the United States.

In recent weeks, some senators have opened up a debate about whether to remove the word “limited” in the Missile Defense Authorization Act. In particular, Senator Tom Cotton (R-Arkansas) and Senator Kelly Ayotte (R-NH) have taken such action in the Senate Armed Services Committee, while Senator Edward Markey (D-Mass.) has sought to restore the word “limited.” Over the past 20 years, the debate in Congress has shifted, such that there is really no debate about whether the United States should have some strategic missile defense system; instead the debate has been about how much the United States should spend on a limited system and how limited it should be. The next president has an opportunity to renew this debate on first principles: that is, whether a strategic missile system provides some crisis stability, whether this system would impede further nuclear arms reductions, and whether this system could achieve adequate technical effectiveness.

I will save (until a future president’s message) the challenges of Iran and North Korea. For this message, I will close by noting that both the George W. Bush administration and the Barack Obama administration made significant progress in securing and reducing nuclear materials that could be vulnerable to theft by terrorists. Preventing nuclear terrorism is very much a bipartisan issue, as is reducing any and all nuclear dangers. How will the next president build on the tremendous legacies of the two previous presidents in keeping the world’s leaders focused on achieving much better security over nuclear materials? Should the Nuclear Security Summit process be continued? What other cooperative international mechanisms can and should be implemented? As the leader of the world’s superpower, the next president must lead and must cooperate with other leaders in the shared endeavor of making the world safer against nuclear threats. As citizens, let’s encourage the candidates to debate seriously these issues and provide practical plans for reducing nuclear dangers.

I am grateful to all the supporters of FAS and readers of the PIR.

Three-Dimensional Arms Control: A Thought Experiment

The George W. Bush Administration is not typically viewed as the paragon of arms control. This was the Administration that withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002, agreed to the Moscow Treaty that same year with no verification provisions, and generally eschewed traditional approaches to arms control, including negotiations and treaties, as Cold War legacies. To be sure, in practice the Administration’s minimal attempts at arms control failed to produce significant results; but in principle, creative and new approaches cannot be so readily discarded. With that in mind, this article is a thought experiment. Some of the proposals suggested here are radical and come with major hurdles, but a non-traditional approach to arms control, based on opportunities rather than challenges, can hopefully generate new thinking.

Welcome Back, Multiple Object Kill Vehicles

Ever since the United States began developing a missile defense system, the focus has been on pursuing a robust missile defense system. As not much progress has been made on boost phase interception, it becomes mandatory to study a technology that could make the midcourse system of the ballistic missile more vulnerable to enemy missile defense system. At present, with counter measures like decoys, chaffs, and multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs), the mid-course phase of the ballistic missile becomes a complicated phase of interception. The Multiple Object Kill Vehicle (MOKV), a program of the United States, is believed to negate these challenges of the missile defense system in the mid-course phase.

Nuclear Security and Safety in America: A proposal on illicit trafficking of radioactive material and orphan sources

The special nature of nuclear energy requires particular safety and security conditions and stronger protective measures. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), as do other international and regional organizations, provides assessment, but it does not know a great deal about the security status of most Member States. It is necessary to learn of and determine the needs and concerns of a State for improving legal framework, reviewing detection of and response to illicit trafficking, and in order to develop a strategic plan that will enhance work that results in tangible improvements of security.

Nuclear law has an international dimension because the risks of nuclear materials do not respect borders. Terrorist acts defy the law; they don’t belong to a State. The possibility of transboundary impacts requires harmonization of policies, programs, and legislation. Several international legal instruments have been adopted in order to codify obligations of States in various fields, which can limit national legislation. There are legal and governmental responsibilities regarding the safe use of radiation sources, radiation protection, the safe management of radioactive waste, and the transportation of radioactive material.

The terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 represented a clear challenge, but they must not stand as obstacles in the development of nuclear technology. It is necessary to reinforce these efforts in order to improve nuclear energy security, because energy is a vital issue that cannot wait.

More From FAS: Highlights and Achievements Throughout Recent Months

NGOs AND THEIR ROLES IN THE VERIFICATION OF NUCLEAR AGREEMENTS – APRIL 2016

After finishing up his second MacArthur Foundation-sponsored research project on issues related to verifying a nuclear agreement with Iran, Christopher Bidwell, FAS Senior Fellow for Nonproliferation Law and Policy, and his team are now focused on a third project that will look at the increased role played by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in verifying compliance and noncompliance with nuclear nonproliferation obligations. Special attention will be paid to how the privacy rights of entities and individuals whose data are used to make a determination can be protected.

35 NOBEL LAUREATES CALL ON WORLD LEADERS TO TAKE ACTION ON NUCLEAR TERRORISM – MARCH 2016

In a letter dated March 26, 2016, 35 Nobel Laureates from physics, chemistry, and medicine urged national leaders attending President Obama’s fourth and final Nuclear Security Summit on March 31st to reduce the risk of nuclear or radiological terrorism to near-zero in three sectors. The signees stressed that because terrorist threats “cross national boundaries,” they “require the concerted work of all nations to prevent… terrorist acts from happening.” They also “urge” world leaders “to devote the necessary resources to make further substantial progress in the coming years to real risk reduction in preventing nuclear and radiological terrorism.” The letter, written by Dr. Burton Richter, a Nobel Laureate in physics and the Paul Pigott Professor in the Physical Sciences at Stanford University and Director Emeritus, Stanford Linear Accelerator Center, and Dr. Charles D. Ferguson, President of FAS, and list of signees is available online at: https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/nobel-laureates-letter-to-nss-march-20162.pdf.

REPORT: SUGGESTIONS ABOUT JAPAN’S NUCLEAR FUEL RECYCLING POLICY BASED ON U.S. CONCERNS – MARCH 2016

To date, Japan’s peaceful nuclear energy use has taken the form of a nuclear fuel recycling policy that reprocesses spent fuel and effectively utilizes the plutonium retrieved in light water reactors (LWRs) and fast reactors (FRs). With the aim to complete recycling domestically, Japan has introduced key technology from abroad and has further developed its own technology and industry. However, Japan presently seems to have issues regarding its recycling policy and plutonium management and, because of recent increasing risks of terrorism and nuclear proliferation in the world, the international community seeks much more secure use of nuclear energy. Yusei Nagata, an FAS Research Fellow from MEXT, Japan, analyzes U.S. experts’ opinions and concerns about Japan’s problem and considers what Japan can (and should) do to solve it.. A full version of the report can be accessed online at: https://fas.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/japannukefuelrecyling_final.pdf.

REPORT: USE OF MICROBIAL FORENSICS IN THE MIDDLE EAST/NORTH AFRICA REGION – MARCH 2016

In this study, Christopher Bidwell and Dr. Randall Murch explore the use of microbial forensics as a tool for creating a common base line for understanding biologically-triggered phenomena, as well as one that can promote mutual cooperation in addressing these phenomena. A particular focus is given to the Middle East/North Africa (MENA) region, as it has been forced to deal with multiple instances of both naturally-occurring and man-made biological threats over the last 10 years. Although the institution of a microbial forensics capability in the MENA region (however robust) is still several years away, establishing credibility of the results offered by microbial forensic analysis performed by western states and/or made today in workshops and training have the ability to prepare the policy landscape for the day in which the source of a bio attack, either man-made or from nature, needs to be accurately attributed. A full version of the report can be accessed online at: /pub-reports/microbial-forensics-middle-east-north-africa/.

REPORT: USE OF ATTRIBUTION AND FORENSIC SCIENCE IN ADDRESSING BIOLOGICAL WEAPON THREATS – FEBRUARY 2016

The threat from the manufacture, proliferation, and use of biological weapons (BW) is a high priority concern for the U.S. Government. As reflected in U.S. Government policy statements and budget allocations, deterrence through attribution (“determining who is responsible and culpable”) is the primary policy tool for dealing with these threats. According to those policy statements, one of the foundational elements of an attribution determination is the use of forensic science techniques, namely microbial forensics. In this report, Christopher Bidwell and Kishan Bhatt, an FAS summer research intern and undergraduate student studying public policy and global health at Princeton University, look beyond the science aspect of forensics and examine how the legal, policy, law enforcement, medical response, business, and media communities interact in a bioweapon’s attribution environment. The report further examines how scientifically based conclusions require credibility in these communities in order to have relevance in the decision making process about how to handle threats. The report can be found online at: /pub-reports/biological-weapons-and-forensic-science/.

THE NEW B61-12 GUIDED NUCLEAR BOMB – JANUARY 2016

From the start of the development of the new $10 billion B61-12 guided nuclear bomb, FAS has been at the forefront of providing the public with factual information about the status and capabilities of the program. In November 2015, Hans Kristensen, Director of the FAS Nuclear Information Project, was featured in a PBS Newshour program about the weapon where former STRATCOM commander and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General James Cartwright confirmed FAS assessments that the increased accuracy of the B61-12 could make it a more usable weapon [/blogs/security/2015/11/b61-12_cartwright/]. In early 2016, FAS and NRDC used a government video of a B61-12 test drop to analyze the bomb’s increased accuracy and earth-penetrating capability [/blogs/security/2016/01/b61-12_earth-penetration/]. The analysis was used in a New York Times feature article, “As U.S. Modernizes Nuclear Weapons, ‘Smaller’ Leaves Some Uneasy.” 1

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE CONFRONTS “CLIMATE CHANGE” – MARCH 7, 2016

The official entry of the term “climate change” in the latest revision of the Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms reflects a growing awareness of the actual and potential impacts of climate change on military operations. Steven Aftergood, Director of the FAS Project on Government Secrecy, reported in Secrecy News that according to a Pentagon directive issued in January 2016, “The DoD must be able to adapt current and future operations to address the impacts of climate change in order to maintain an effective and efficient U.S. military.” Among other things, the new directive requires the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and the Director of National Intelligence to coordinate on “risks, potential impacts, considerations, vulnerabilities, and effects [on defense intelligence programs] of altered operating environments related to climate change and environmental monitoring.” In a report to Congress last year, the DoD said that “The Department of Defense sees climate change as a present security threat, not strictly a long-term risk.” Read Aftergood’s analysis in full here: /blogs/secrecy/2016/01/dod-climate/.

THE NEW NUCLEAR CRUISE MISSILE – OCTOBER-DECEMBER 2015

The FAS Nuclear Information Project provided the public with important analysis about the mission and capabilities of the new nuclear air-launched cruise missile the Air Force is developing: the Long-Range Standoff missile (LRSO). The analysis was the first to highlight an overview of the mission government officials say the missile is needed for, a mission that includes a worrisome nuclear war-fighting role [/blogs/security/2015/10/lrso-mission/]. Hans Kristensen was also quick to point out that a new long-range conventional air-launched cruise missile being deployed by the Air Force could do much of the LRSO mission and he recommended canceling the LRSO, a measure which would save $20-$30 billion [/blogs/security/2015/12/lrso-jassm/].

PAKISTANI NUCLEAR FORCES – OCTOBER 2015

FAS research on the status and modernization of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons was covered extensively in news media reports in connection with Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif’s visit to Washington in October 2015. The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans Kristensen and Robert S. Norris, FAS Senior Fellow for Nuclear Policy, published by the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, estimated that Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal has grown by 20 weapons since 2011 to 130 warheads presently, including new tactical nuclear weapons. The research was used by the New York Times in a background article, “U.S. Set to Sell Fighter Jets to Pakistan, Balancing Pressure on Nawaz Sharif,”2 and an editorial, “The Pakistan Nuclear Nightmare,”3 as well as by the Associated Press and Indian and Pakistani news media. The Nuclear Notebook can be accessed at: https://fas.org/blogs/security/2015/10/pakistan-notebook/.

ODNI ISSUES TRANSPARENCY IMPLEMENTATION PLAN – OCTOBER 28, 2015

Transparency is not ordinarily a trait that one associates with intelligence agencies. But the Office of the Director of National Intelligence has released a transparency implementation plan that establishes guidelines for increasing public disclosure of information by and about U.S. intelligence. Based on a set of principles on transparency that were published earlier last year, the plan prioritizes the objectives of transparency and describes potential initiatives that could be undertaken. Thus, the plan aims “to provide more information about the IC’s governance framework; to provide more information about the IC’s mission and activities; to encourage public engagement [by intelligence agencies in social media and other venues]; and to institutionalize transparency policies and procedures.” FAS Secrecy News reports that the plan neither includes any specific commitments nor sets any deadlines for action. Moreover, it is naturally rooted in self-interest. Its purpose is explicitly “to earn and retain public trust” of U.S. intelligence agencies. Nonetheless, it has the potential to provide new grounds for challenging unnecessary secrecy and to advance a corresponding “cultural reform” in the intelligence community. Read Aftergood’s analysis here: /blogs/secrecy/2015/10/transparency-plan/.

DOD SECURITY-CLEARED POPULATION DROPS AGAIN – OCTOBER 7, 2015

The number of people in the Department of Defense holding security clearances for access to classified information declined by 100,000 in the first six months of FY2015, recounts FAS Secrecy News. The latest available data show 3.8 million DoD employees and contractors with security clearances, down from 3.9 million earlier in 2015, and a steep 17.4 percent drop from 4.6 million two years ago. Furthermore, only 2.2 million of the 3.8 million cleared DoD personnel are actually “in access,” meaning that they have current access to classified information. Thus, further significant reductions in clearances would seem to be readily achievable by shedding those who are not currently “in access.” The total number of security-cleared persons government-wide is roughly 0.5 million higher than the number of DoD clearances, putting it at around 4.3 million, down from 5.1 million in 2013. The new DoD security clearance numbers were presented in the latest quarterly report on Insider Threat and Security Clearance Reform, FY2015 Quarter 3, September 2015. The reduction in security clearances is not simply a reflection of programmatic or budgetary changes – rather, it has been defined as a policy goal in its own right. A bloated security bureaucracy is harder to manage, more expensive, and more susceptible to catastrophic security failures than a properly streamlined system would be. The full post is available to view here: /blogs/secrecy/2015/10/clearances-down/.

Navy Builds Underground Nuclear Weapons Storage Facility; Seattle Busses Carry Warning

Seattle busses warn of largest nuclear weapons base. Click image to see full size.

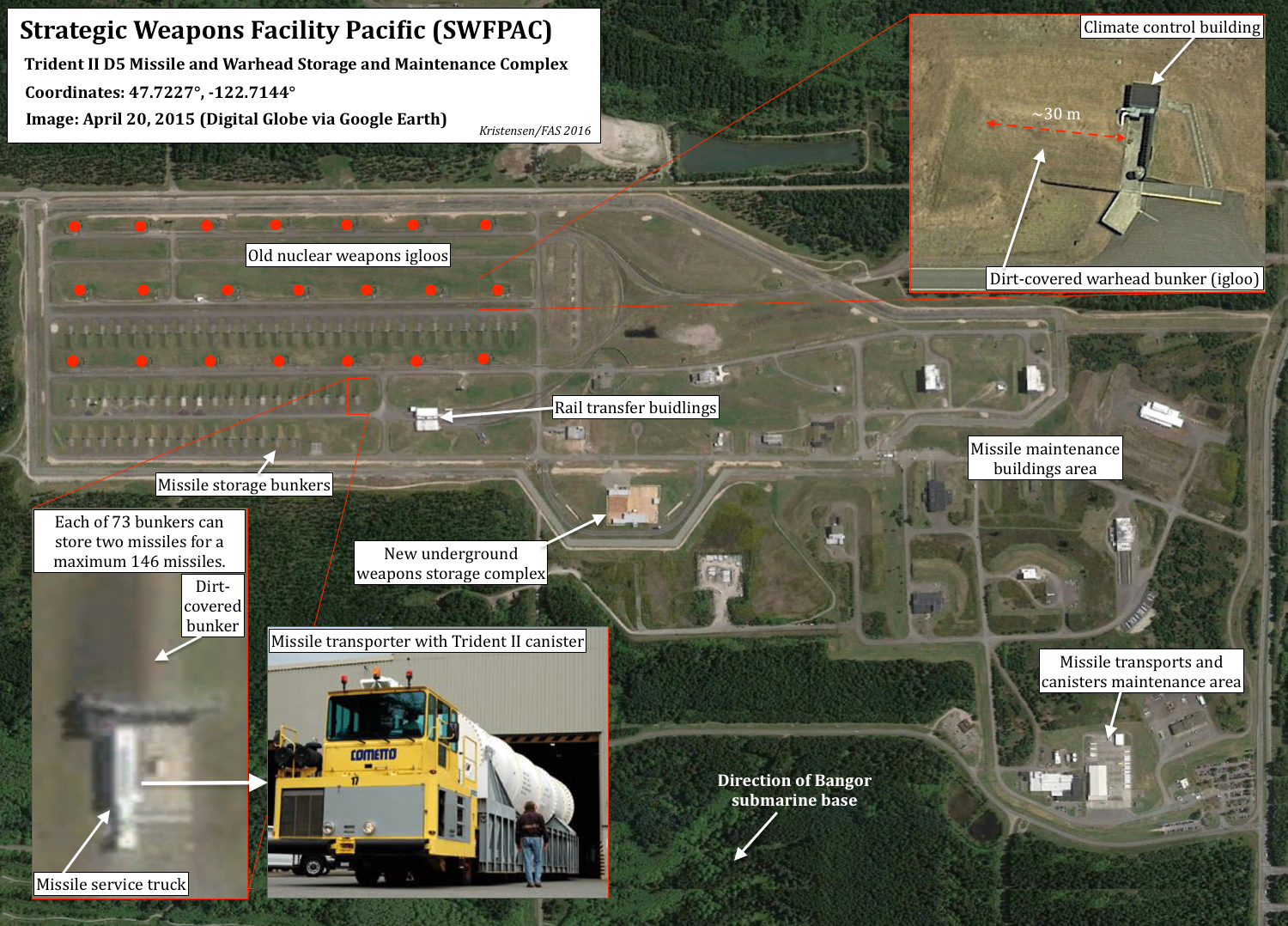

The US Navy has quietly built a new $294 million underground nuclear weapons storage complex at the Strategic Weapons Facility Pacific (SWFPAC), a high-security base in Washington that stores and maintains the Trident II ballistic missiles and their nuclear warheads for the strategic submarine fleet operating in the Pacific Ocean.

The SWFPAC and the eight Ohio-class nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) homeported at the adjacent Bangor Submarine Base are located only 20 miles (32 kilometers) from downtown Seattle. The SWFPAC and submarines are thought to store more than 1,300 nuclear warheads with a combined explosive power equivalent to more than 14,000 Hiroshima bombs.

A similar base with six SSBNs is located at Kings Bay in Georgia on the US east coast, which houses the SWFLANT (Strategic Weapons Facility Atlantic) that appears to have a dirt-covered warhead storage facility instead of the underground complex built at SWFPAC. Of the 14 SSBNs in the US strategic submarine fleet, 12 are considered operational with 288 ballistic missiles capable of carrying 2,300 warheads. Normally 8-10 SSBNs are loaded with missiles carrying approximately 1,000 warheads.

To bring public attention to the close proximity of the largest operational nuclear stockpile in the United States, the local peace group Ground Zero Center for Nonviolent Action has bought advertisement space on 14 transit buses. The busses will carry the posters for the next eight weeks. FAS is honored to have assisted the group with information for its campaign.

The Limited Area Protection and Storage Complex

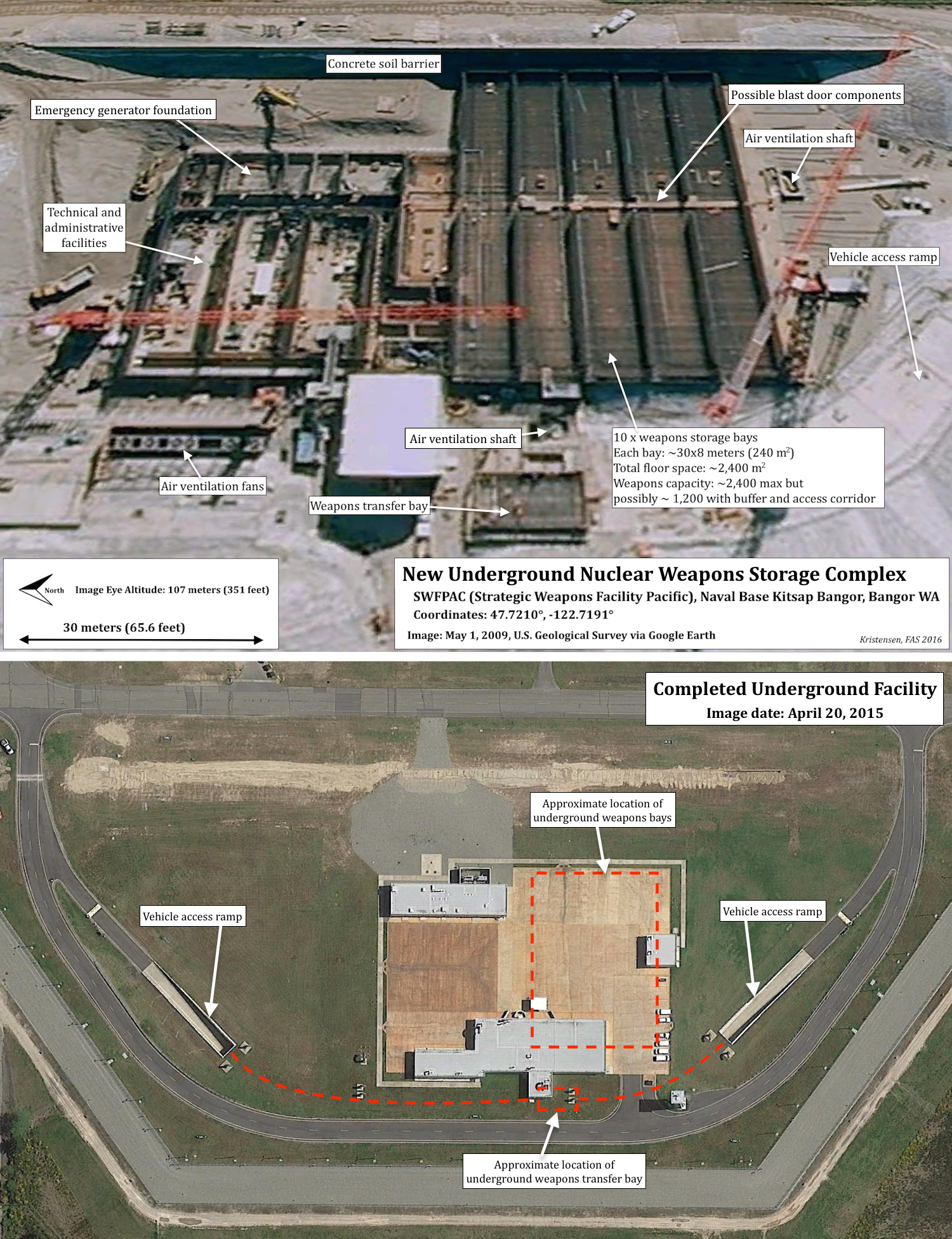

Although the new underground storage complex is not a secret – its existence has been reported in public navy documents since 2003 – it has largely escaped public attention until now.

The new complex is officially known as the Limited Area Protection and Storage Complex (LAPSC), or navy construction Project Number P973A. The complex was originally estimated to cost $110 million but ended up costing nearly $294 million.

The US Navy describes the complex as “a reinforced concrete, underground, multi-level re-entry body processing and storage facility” with “hardened floors, and hardened load-bearing walls and roof.” Glen Milner at the Ground Zero Center helped locate some of the budget documents. Other construction details provided by the navy further describe the complex as:

A 16,000-m2 [180,000 square feet] multi-level, underground, hardened, blast-resistant, reinforced concrete structure, with approximate dimensions of 110 meters long by 82 meters wide. Two tunnels (approximately 122 meters long, 6 meters wide, and 6 meters tall) will provide heavy vehicle access to and from the LAPSC. An aboveground portion of the facility will provide administrative and utility support spaces. Special features of the facility include: power-operated physical security and blast-resistant doors, TEMPEST shielded rooms, seven (7) overhead bridge cranes (2 ton capacity), three (3) elevators, lightning protection system, grounding system, liquid waste collection/retention system, emergency air purge system, fire protection systems, and multiple HVAC systems. This project will also provide a new 1000 kW emergency generator (enclosed within a new hardened, reinforced concrete structure), two security guard towers, lightning protection, utilities, and other site improvements. The existing Limited Area perimeter fence, security zone, and patrol roads will be expanded to encompass the new LAPSC.

The underground complex is similar to the general design of the large underground nuclear weapons storage facility Kirtland AFB in New Mexico, known as Kirtland Underground Munitions Storage Complex (KUMSC) – except KUMSC appears to be four times bigger than the SWFPAC complex. It appears to include 10 weapons storage bays (each 30 x 8 meters; 98 x 26 feet) where nuclear W76 and W88 warheads in their containers will be stored when they’re not deployed on submarines (see image analysis below).

New underground nuclear weapons storage site at Naval Base Kitsap. Click to view full size.

The primary building contractor, Ammann & Whitney, describes the unique blast doors and gas-tight features intended to ensure the safe storage and handling of the nuclear weapons:

The structures are reinforced concrete containment structures designed to withstand both interior and exterior explosions. All exterior penetrations and blast doors are gas-tight. There are a total of 24 blast doors; 12 are located in the above ground structures and 12 in the buried structure. All 12 doors in the above ground structures are subject to exterior blast loads while seven are subject to additional internal gas loads. Of the 12 doors in the buried structure, six doors are subject to blast loads from both sides, the remaining six are subject to blast loads from one side only but three must be gas-tight. Penetrations from the buried structure are blast resistant and gas-tight.

Design of the complex began in 2002, construction in 2007, and by 2009 the excavation and main outlines were clearly visible on satellite images. The complex was completed in 2012. Construction required enormous amounts of concrete. Over an 18-month period between December 2008 and mid-2010, for example, two hundred cement trucks entered the base every two weeks.

Nuclear weapon at SWFPAC were previously stored in above-ground earth-covered bunkers, or igloos, from where they were transported to two above-ground handling facilities for maintenance or for loading onto Trident II sea-launched ballistic missiles for deployment on operational SSBNs.

But the navy has concluded that a “single underground protected structure provides the most robust protection for fulfilling this mission against all threats.” With the completion of the underground complex, the old surface facilities (2 handling buildings and 21 igloos) will be demolished (see site outline above).

The US Navy plans to operate nuclear-armed ballistic missile submarines at Naval Base Kitsap at least through 2080.

Over the next could couple of years the navy will “convert” four of the 24 missile launch tubes on each SSBN. The conversion will remove the capability to launch missiles from the four tubes, which no longer count under the New START treaty. The 384 excess warheads associated with the 24 missiles will likely be dismantled, leaving roughly 1,000 warheads at SWFPAC.

In the longer term (in the 2030s), the US Navy will transition to a new fleet of 12 SSBNs that will replace the current 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Each of the new submarines will only carry 16 missiles, a reduction of an additional four tubes from the 20 left on the New START compatible SSBNs. Assuming seven of the 12 new SSBNs will be based at Bangor, that will leave 112 missiles with an estimated 896 warheads at SWFPAC and Bangor submarine base, or a reduction of about one-third of the warheads currently stored there.

Despite these expected reductions, the Naval Base Kitsap complex (the SWFPAC and Bangor submarine base) will remain the largest and most important nuclear weapons base in the United States for the foreseeable future.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Flawed Pentagon Nuclear Cruise Missile Advocacy

The Pentagon is using flawed arguments to sell a nuclear cruise missile to President Obama?

By Hans M. Kristensen

In its quest to secure Congressional approval for a new nuclear cruise missile, the Pentagon is putting words in the mouth of President Barack Obama and spinning and overstating requirements and virtues of the weapon.

Last month, DOD circulated an anonymous letter to members of Congress after it learned that Senator Dianne Fenstein (D-CA) was planning an amendment to the FY2017 National Defense Authorization Act to put limits on funding and work on the new Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) nuclear air-launched cruise missile. The letter not surprisingly opposes the limits but contains a list of amazingly poor justifications for the new weapon.

The letter follows another letter in March from Under Secretary of Defense Frank Kendall to Senator John McCain that contains false claims about official documents endorsing the LRSO, as well a vague and concerning statements about the mission and purpose of the weapon.

The two letters raise serious questions about DOD’s justifications for the LRSO and Congress’ oversight of the program.

About That Strategy…

The DOD letter circulated to Congress in May presents surprisingly poor arguments in defense of the LRSO. In response to Senator Feinstein asking the Pentagon to show “the types of targets the LRSO is needed to destroy that cannot also be destroyed by existing U.S. nuclear and conventional weapons, “ DOD spins off into an off-topic, incoherent, and vague defense for retaining different nuclear capabilities in the arsenal:

Using the ability to destroy the target as the sole metric would also fail to address the dependence of effective deterrence on possessing credible options for responding to adversary attacks. A strategy of relying on large-scale or high-yield response options is credible and effective for deterring large-scale nuclear attack, particularly against the U.S. homeland, but it is less credible in the context of limited adversary use against an ally or U.S. forces operating abroad. Maintaining a credible ability to respond to a limited as well as large-scale nuclear attack against the United States or our allies strengthens our ability to deter such attacks from ever taking place.

But Feinstein’s draft amendment doesn’t say that destruction of the target is or should be “the sole metric” for deterrence. Even so, the bottom line for an effective nuclear deterrent is the credible capability to hold at risk the targets that an adversary values most. One can try to do that in many different ways, of course, but the DOD letter’s portrayal of an either-or choice between “large-scale or high-yield response options” against large attacks or limited-scale and lower-yield response options to limited adversary attacks is obviously a strawman argument because no one – certainly not Feinstein’s draft resolution – is arguing that the United States should eliminate its large inventory of lower-yield gravity bombs on heavy bombers and dual-capable fighter bombers. The US nuclear arsenal would still be able to provide limited and lower-yield options if the LRSO were canceled.

Next the DOD May letter tries to paint the LRSO decision as a choice between nuclear and non-nuclear weapons:

We do not and should not think of nuclear weapons as just another tool for destroying a target. The President’s guidance directs that [sic] DoD to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through non-nuclear strike options, but also recognizes the unique contribution of nuclear weapons to our overall deterrence strategy. For example, the President might require a nuclear response to a nuclear attack in order to restore deterrence and prevent further attacks, even if a conventional weapon could also destroy the target.

This is another strawman argument because Feinstein’s draft amendment does not call for the elimination of all nuclear weapons or gravity bombs on heavy bombers and dual-capable fighter-bombers. Those weapons would of course still provide limited escalation-control options if the LRSO were canceled. Not to mention what non-nuclear cruise missiles could accomplish.

Next the DOD May letter gets into the obscure issue of “hedging” where multiple warhead types are used to provide backup against possible failure of one of them. I won’t go into a detailed analysis of hedging (Union of Concerned Scientists has a good report here) but critique the claims made in the DOD letter:

Requiring that only one warhead type is suitable for a given target also misses the LRSO’s critical role in providing the ability to hedge against significant geopolitical or technical issues. An effective bomber force with standoff capability can be put on alert in response to a serious technical problem in another leg of the Triad, or if the nature of the threat changes suddenly. Reliance on a single warhead type would threaten the stability of our deterrence posture, and would have changed the approach required for negotiating the New START Treaty with Russia.

The Feinstein draft amendment does not argue “that only one warhead is suitable for a given target” but asks for clarity about what the LRSO targets are that cannot also be destroyed by other existing nuclear or conventional weapons. That’s a reasonable question when someone is asking you to pay for a weapon that might cost $20 to $30 billion dollars over its lifetime.

But an effective bomber force does not require the LRSO to hedge. A force that includes 20 B-2 and 100 B-21 stealthy bombers (60 of them equipped with nearly 500 B61-12 gravity bombs) would still provide a considerable hedging capability against a serious technical problem in another leg of the Triad. Under the New START Treaty force structure the ICBMs are planned to deploy 400 warheads and the SLBMs 1,090 warheads.

However, the bomber hedging argument is weak. Under the Pentagon’s so-called 3+2 warhead plan (which is actually a 6+2 warhead plan according to a 2015 JASONs study), billions of dollars will be spent on building six new warhead types for the two ballistic missile legs partially to hedge against warhead failures on each other. So if the two ballistic legs are already designed to hedge each other, why are bomber weapons needed to hedge them as well? It sounds more like the Pentagon is using the hedge argument as a way to get the LRSO.

It is also amazing to see DOD bluntly advocating that the “bomber force with standoff capability can be put on alert… if the nature of the threat changes suddenly.” The bombers were taken off alert in 1991 and the Pentagon strongly argues against the dangers of rapidly increasing the alert level of nuclear forces.

The Kendall letter from March also defends the LRSO because it gives the Pentagon the ability to rapidly increase the number of deployed warheads significantly on its strategic launchers. He does so by bluntly describing it as a means to exploit the fake bomber weapon counting rule (one bomber one bomb no matter what they can actually carry) of the New START Treaty to essentially break out from the treaty limit without formally violating it:

Additionally, cruise missiles provide added leverage to the U.S. nuclear deterrent under the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty. The accounting rules for nuclear weapons carried on aircraft are such that the aircraft only counts as one weapon, even if the aircraft carries multiple cruise missiles.

It is disappointing to see a DOD official justifying the LRSO as a means to take advantage of a loophole in the treaty to increase the number of deployed strategic nuclear weapons above 1,550 warheads. Not least because the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy determined that the Pentagon, even when the New START Treaty is implemented in 2018, will still have up to one-third more nuclear weapons deployed than are needed to meet US national and international security commitments.

Finally, the DOD May letter also takes issue with the Feinstein draft resolution demand to certify that the sole objective of the LRSO is to deter nuclear attack. This would be inconsistent with the Administration’s nuclear weapons policy and the President’s guidance on nuclear employment, DOD says. Even though the NPR and guidance both affirmed that “the fundamental purpose of all U.S. nuclear weapons is to deter nuclear attack,” they also determined that a sole-purpose nuclear policy can not be adopted yet because there “remains a narrow range of contingencies in which U.S. nuclear weapons may still play a role in deterring a conventional or CBW attack against the United States or its allies and partners.”

The public DOD report on the 2013 guidance does not mention the “role in deterring a conventional or CBW attack” that the NPR specifies. And there are rumors that the guidance removed the requirement to plan nuclear missions against chemical weapons attacks. If so, that would leave only biological and conventional attacks other than nuclear attacks as a role for US nuclear weapons. Deterring biological attacks is thought to remain a mission because of the widespread human casualties such weapons can cause. And conventional might for example refer to a devastating North Korean conventional attack against Seoul or a Russian conventional attack against Eastern European NATO allies. But it is unclear and such attacks would in any case almost certainly be more likely to trigger non-nuclear responses; why would the US escalate to nuclear use if no one else has?

It is curious why Senator Feinstein chose the wording “sole objective” given that the NPR and guidance both clearly rejected a “sole purpose of nuclear weapons” for now (although the policy is to “work to establish conditions under which such a policy could be safely adopted”). She must have known that it would be easily rejected.

But it is also possible that what she was really after was a way to limit the almost tactical warfighting mission of the LRSO that numerous officials have widely described in public statements. Only a week after Kendall sent his LRSO letter to Senator McCain, Senator Feinstein said during a hearing:

The so-called improvements to this weapon seemed to be designed candidly to make it more usable, to help us fight and win a limited nuclear war. I find that a shocking concept. I think this is really unthinkable, especially when we hold conventional weapons superiority, which can meet adversaries’ efforts to escalate a conflict. (Emphasis added.)

The two DOD letters seem to confirm Senator Feinstein’s worst fears. The Kendall letter speaks of “flexible options across the full range of threat scenarios” with “multi-axis” attacks, and the DOD May letter talks about using “lower-yield” options in limited regional scenarios “even if a conventional weapon could also destroy the target.”

About Those Claims…

The Kendall letter, first published by Union of Concerned Scientists, makes numerous claims about official documents endorsing the LRSO. But when you check the documents, it turns out that they don’t explicitly endorse the weapon. Some don’t even mention it.

For example, Kendall claims that the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review “committed to maintaining a viable standoff nuclear deterrent for the air leg of the Triad…” But the NPR made no such commitment. The pubic version of the NPR only stated that “the Air Force will conduct an assessment of alternatives to inform decisions in FY 2012 about whether and (if so) how to replace the current air-launched cruise missile (ALCM)…” (Emphasis added). Contrary to Kendall’s claim, there is no explicit commitment in the public NPR to a nuclear cruise missile capability beyond the lifespan of the current ALCM.

Kendall also claims that the 2014 Nuclear Enterprise Review “committed to maintaining a viable standoff nuclear deterrent for the air leg of the Triad…” But that is also wrong. The public version of the document does not mention a cruise missile replacement at all but instead acknowledges “a moderate public attack on the need for the cruise missile carrying B-52 force…”

In terms of how the LRSO aligns with US nuclear employment strategy, the Kendall letter also explains that the DOD report Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, to which President Obama provided the foreword, “reaffirmed the need for U.S. forces to project power and hold at risk any target at any location on the globe, to include anti-access and area denial environments.”

That may be so but neither the DOD report nor President Obama’s foreword mention a requirement for a nuclear cruise missile with one word. Instead, here is what the report says:

Project Power Despite Anti-Access/Area Denial Challenges. In order to credibly deter potential adversaries and to prevent them from achieving their objectives, the United States must maintain its ability to project power in areas in which our access and freedom to operate are challenged… Accordingly, the U.S. military will invest as required to ensure its ability to operate effectively in anti-access and area denial (A2/AD) environments. This will include implementing the Joint Operational Access Concept, sustaining our undersea capabilities, developing a new stealth bomber, improving missile defenses, and continuing efforts to enhance the resiliency and effectiveness of critical space-based capabilities.

On the same issue, President Obama’s foreword states:

As we end today’s wars and reshape our Armed Forces, we will ensure that our military is agile, flexible, and ready for the full range of contingencies. In particular, we will continue to invest in the capabilities critical to future success, including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; counterterrorism; countering weapons of mass destruction; operating in anti-access environments; and prevailing in all domains, including cyber.

Neither the DOD report nor Obama’s foreword makes any explicit commitment to a new nuclear cruise missile. Yet Kendall nonetheless uses them both to argue for one.

Humanitarian Crocodile Tears

The DOD May letter contains some really interesting statements about nuclear weapons and international law and collateral damage. The letter argues that not acquiring the LRSO would be “inconsistent with Administration policy and Presidential guidance” because the June 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance “directs that all plans must apply the principles of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian populations and civilian objects.”

According to the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy report DOD sent to Congress in June 2013, the guidance “makes clear that all plans must also be consistent with the fundamental principles of the Law of Armed Conflict. Accordingly, plans will, for example, apply the principles of distinction and proportionality and seek to minimize collateral damage to civilian populations and civilian objects. The United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or civilian objects.”

This has been US policy for several decades but it is great that it was included in the new guidance. And it is even better if it actually restrains nuclear strike planning. But the authors of the DOD May letter forget to mention that even if the Obama administration were to cancel the LRSO, the Pentagon still plans to retain nearly 500 nuclear gravity bomb with lower yields for delivery by heavy bombers and dual-capable fighter-bombers. Retiring the ALCM or canceling the LRSO would not be incompatible with the guidance.

Yet the May letter illustrates how the new guidance is already being used by nuclear advocates in a twisted effort to use concern about civilian casualties in war as an argument against retiring existing nuclear weapons and to justify acquisition of new nuclear weapons that are more accurate with better lower-yield options to reduce radioactive fallout from nuclear attacks. The LRSO is one example; the B61-12 gravity bomb is another. As STRATCOM commander Gen. Robert Kehler told Congress in 2013 shortly after the guidance was published, “…we are trying to pursue weapons that actually are reducing in yield because we’re concerned about maintaining weapons that would have less collateral effect if the President ever had to use them.” (Emphasis added.)

“Electing to retire a lower-yield option because a higher-yield weapon can also destroy the target would be inconsistent with this principle and direction,” the DOD May letter concludes.

What makes this newfound “humanitarian” concern of the nuclear planners particularly hypocritical is that they don’t use the same guidance to conclude that the thousands of high-yield nuclear warheads on ICBMs and SLBMs therefore would be equally “inconsistent with Administration policy and Presidential guidance.”

Apparently, limiting damage to civilians is only worth it if you can get a better weapon in return.

Conclusions and Recommendations

It is the responsibility of the Pentagon to advocate for nuclear forces but this should also require it to have clear and valid justifications for why it needs them. The March letter from DOD’s Frank Kendall and the anonymous DOD letter from May arguing for why the Congress should approve and pay for the LRSO clearly fall short of that standard. Instead, they are full of false claims, spin, and vague and overstated assertions about its mission.

The scary part of this is that a majority in Congress appears to have accepted these poor justifications for the LRSO. The majority leadership in the Senate Armed Services Committee recently rejected an amendment by Senator Edward Markey to delay funding for the LRSO to allow Congress to better study the justifications. The rejection made use of many of the same false claims, spin, and vague overstatements that the DOD letters contain.

The DOD May letter rejecting Senator Feinstein’s draft amendment insisted that the LRSO Assessment of Alternative provided to Congress in 2014 “does not and should not address why we have an airborne standoff leg of the Triad,” and that the AoA therefore “only examined technical options to meet an air-based stand-off strategy in a cost and mission-effective manner.”

But then, in the next sentence, DOD essentially told the lawmakers that unless they approved more money for the LRSO program to advance it further, they cannot be told what the cost will be.

This is tantamount to blackmailing and wrong because several officials privately have said that they have already seen preliminary briefings on estimated life-cycle costs for both the LRSO missile and W80-4 warhead.

Providing false claims, spin, and vague overstatements about the requirements and mission of the LRSO is bad enough. But unless President Obama during his remaining time in office decides to cancel the LRSO program, it could end up costing the taxpayers $20-$30 billion over the lifetime of the weapon for a nuclear weapon the United States doesn’t need.

Further reading about the LRSO:

- Questions About The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

- Forget LRSO; JASSM-ER Can Do The Job

- LRSO: The Nuclear Cruise Mission

- W80-1 Warhead Selected For New Nuclear Cruise Missile

- B-2 Stealth Bomber To Carry New Nuclear Cruise Missile

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Briefing to Arms Control Association Annual Meeting

Yesterday I gave a talk at the Arms Control Association’s annual meeting: Global Nuclear Challenges and Solutions for the Next U.S. President. A full-day and well-attended event that included speeches by many important people, including Ben Rhodes, who is Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications in the Obama administration.

My presentation was on the panel “Examining the U.S. Nuclear Spending Binge,” which included Mark Cancian from CSIS, Amy Woolf from CRS, and Andrew Weber, the former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical, and Biological Defense Programs. I was asked to speak about the enhancement of nuclear weapons that happens during the nuclear modernization programs and life-extension programs and the implications these improvement might have for strategic stability.

My briefing described enhancement of military capabilities of the B61-12 nuclear bomb, the new air-launched cruise missile (LRSO), and the W76-1 warhead on the Trident submarines. The briefing slides are available here:

Nuclear Modernization, Enhanced Military Capabilities, and Strategic Stability.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Updated Nuclear Stockpile Figures Declassified

The size of the U.S. nuclear stockpile as of September 30, 2015 — 4,571 weapons — and the number of U.S. nuclear weapons that were dismantled in FY 2015 — 109 of them — were declassified and disclosed last week.

The latest figures came as a disappointment to arms control and disarmament advocates who favor sharp reductions in global nuclear inventories.

The new numbers “show that the Obama administration has reduced the U.S. stockpile less than any other post-Cold War administration, and that the number of warheads dismantled in 2015 was lowest since President Obama took office,” wrote Hans M. Kristensen in the FAS Strategic Security blog.