Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

North Korean Nuclear Weapons, 2024: Federation of American Scientists Release Latest North Korea Nuclear Weapons Estimate

North Korea continues to modernize and grow its nuclear weapons arsenal

Washington, D.C. – July 15, 2024 – The Federation of American Scientists today released the North Korea edition of the Nuclear Notebook, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and available here. The authors, Hans Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, estimate that North Korea may have produced enough fissile material to build up to 90 nuclear warheads, but the famously opaque country has likely assembled fewer than that—potentially around 50. This is not a significant change from previous estimates (2021, 2022) but follows the trendline researchers are tracking. North Korea’s abandonment of a no-first-use policy coincides with the country’s recent efforts to develop tactical nuclear weapons.

Warhead Preparation and Delivery

While its status remains unclear, North Korea has developed a highly diverse missile force in all major range categories. In this edition of the Nuclear Notebook, FAS researchers documented North Korea’s short-range tactical missiles, sea-based missiles, and new launch platforms such as silo-based and underwater platforms Additionally, FAS researchers provided an overview of North Korea’s advancements in solid-fuel missile technology, which will improve the survivability and mobility of its missile force.

“Since 2006, North Korea has detonated six nuclear devices, updated its nuclear doctrine to reflect the irreversible role of nuclear weapons for its national security, and continued to introduce a variety of new missiles test-flown from new launch platforms,” says Hans Kristensen, director of FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

The size and composition of North Korea’s nuclear stockpile depends on warhead design and the number and types of launchers that can deliver them.

Disco Balls, Peanuts, and Olives

Researchers informally refer to North Korea’s nuclear warhead designs as the disco ball, peanut, and olive based on their appearance in North Korean state media. These images, taken from this recent issue of the North Korea Nuclear Notebook, show supposed warhead designs, including a single-stage implosion device (nicknamed “disco-ball”), a new miniaturized warhead called the Hwasan-31 (nicknamed “olive”), and a two-stage thermonuclear warhead (nicknamed “peanut”).

Caption: Images from the Nuclear Notebook: North Korea, 2024. Top left “disco ball”, top right “olive”, bottom left “peanut”. (Source: Federation of American Scientists).

While North Korea’s warhead design and stockpile makeup are not verifiable, it is possible that most weapons are single-stage fission weapons with yields between 10 and 20 kilotons of TNT equivalent, akin to those demonstrated in the 2013 and 2016 tests. A smaller number could be composite-core single-stage warheads with a higher yield.

The Hwasan-31, first showcased in 2023, demonstrates North Korea’s progress towards developing and fielding short-range, or tactical, nuclear weapons. In addition to the development and demonstration of new long-range strategic nuclear-capable missiles, the pursuit of tactical nuclear weapons appears intended to provide options for nuclear use below the strategic level and to strengthen North Korea’s regional deterrence posture.

###

ABOUT THE NUCLEAR NOTEBOOK

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The joint publication began in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenals and the role of nuclear weapons in national security.

This latest issue follows the release of the 2024 United States Nuclear Notebook. The next issue will focus on India. More research is located at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review: Arms Control Subdued By Military Rivalry

On 27 October 2022, the Biden administration finally released an unclassified version of its long-delayed Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). The classified NPR was released to Congress in March 2022, but its publication was substantially delayed––likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Compared with previous NPRs, the tone and content come closest to the Obama administration’s NPR from 2010. However, it contains significant adjustments because of the developments in Russia and China. (See also our global overview of nuclear arsenals)

Despite the challenges presented by Russia and China, the NPR correctly resists efforts by defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists to add nuclear weapons to the U.S. arsenal and delay the retirement of older types. Instead, the NPR seeks to respond with adjustments in the existing force posture and increase integration of conventional and nuclear planning.

Although Joe Biden during his presidential election campaign spoke strongly in favor of adopting no-first-use and sole-purpose policies, the NPR explicitly rejects both for now.

From an arms control and risk reduction perspective, the NPR is a disappointment. Previous efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals and the role that nuclear weapons play have been subdued by renewed strategic competition abroad and opposition from defense hawks at home.

Even so, the NPR concludes it may still be possible to reduce the role that nuclear weapons play in scenarios where nuclear use may not be credible.

Unlike previous NPRs, the 2022 version is embedded into the National Defense Strategy document alongside the Missile Defense Review.

Below is our summary and analysis of the major portions of the NPR:

The Nuclear Adversaries

The NPR identifies four potential adversaries for U.S. nuclear weapons planning: Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. Of these, Russia and China are obviously the focus because of Russia’s large arsenal and aggressive behavior and because of China’s rapidly increasing arsenal. The NPR projects that “[b]y the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.” This echoes previous statements from high-ranking US military leaders, including the former and incoming Commanders of US Strategic Command although the NPR appears less “the sky is falling.”

China: Given that the National Defense Strategy is largely focused on China, it is unsurprising that the NPR declares China to be “the overall pacing challenge for U.S. defense planning and a growing factor in evaluating our nuclear deterrent.”

Echoing the findings of the previous year’s China Military Power Report, the NPR suggests that “[t]he PRC likely intends to possess at least 1,000 deliverable warheads by the end of the decade.” According to the NPR, China’s more diverse nuclear arsenal “could provide the PRC with new options before and during a crisis or conflict to leverage nuclear weapons for coercive purposes, including military provocations against U.S. Allies and partners in the region.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces.

Russia: The NPR presents harsh language about Russia, in particular surrounding its behavior around the invasion of Ukraine. In contrast to the Trump administration’s NPR, the assumptions surrounding a potential low-yield “escalate-to-deescalate” policy have been toned down; instead the NPR simply states that Russia is diversifying its arsenal and that it views its nuclear weapons as “a shield behind which to wage unjustified aggression against [its] neighbors.”

The review’s estimate of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons –– “up to 2,000 –– matches those of previous military statements. In 2021, the Defense Intelligence Agency concluded that Russia “probably possesses 1,000 to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads.” The State Department said in April 2022 that the estimate includes retired weapons awaiting dismantlement. The subtle language differences reflect a variance in estimates between the different US military departments and agencies.

The NPR also suggests that “Russia is pursuing several novel nuclear-capable systems designed to hold the U.S. homeland or Allies and partners at risk, some of which are also not accountable under New START.” Given that both sides appear to agree that Russia’s new Sarmat ICBM and Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle fit smoothly into the treaty, this statement is likely referring to Russia’s development of its Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, its Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile, and its Status-6 Poseidon nuclear torpedo.

It appears that Russia and the United States are at odds over whether these three systems are treaty-accountable weapons. In 2019, then-Under Secretary Andrea Thompson noted during congressional testimony that all three “meet the US criteria for what constitutes a “new kind of strategic offensive arms’ for purposes of New START.” However, Russian officials had previously sent a notice to the United States stating that they “find it inappropriate to characterize new weapons being developed by Russia that do not use ballistic trajectories of flight moving to a target as ‘potential new kinds of Russian strategic offensive arms.’ The arms presented by the President of the Russian Federation on March 1, 2018, have nothing to do with the strategic offensive arms categories covered by the Treaty.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on Russian nuclear forces.

North Korea: In recent years, North Korea has been overshadowed by China and Russia in the U.S. defense debate. Nonetheless this NPR describes North Korea as a target for U.S. nuclear weapons planning. The NPR bluntly states: “Any nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its Allies and partners is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime. There is no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on North Korean nuclear forces.

Iran: The NPR also describes Iran even though it does not have nuclear weapons. Interestingly, although Iran is not in compliance with its NPT obligations and therefore does not qualify for the U.S. negative security assurances, the NPR declares that the United States “relies on non-nuclear overmatch to deter regional aggression by Iran as long as Iran does not possess nuclear weapons.”

Nuclear Declaratory Policy

The NPR reaffirms long-standing U.S. policy about the role of nuclear weapons but with slightly modified language. The role is: 1) Deter strategic attacks, 2) Assure allies and partners, and 3) Achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails.

The NPR reiterates the language from the 2010 NPR that the “fundamental role” of U.S. nuclear weapons “is to deter nuclear attacks” and only in “extreme circumstances.” The strategy seeks to “maintain a very high bar for nuclear employment” and, if employment of nuclear weapons is necessary, “seek to end conflict at the lowest level of damage possible on the best achievable terms for the United States and its Allies and partners.”

Deterring “strategic” attacks is a different formulation than the “deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear attack” language in the 2018 NPR, but the new NPR makes it clear that “strategic” also accounts for existing and emerging non-nuclear attacks: “nuclear weapons are required to deter not only nuclear attack, but also a narrow range of other high consequence, strategic-level attacks.”

Indeed, the NPR makes clear that U.S. nuclear weapons can be used against the full spectrum of threats: “While the United States maintains a very high bar for the employment of nuclear weapons, our nuclear posture is intended to complicate an adversary’s entire decision calculus, including whether to instigate a crisis, initiate armed conflict, conduct strategic attacks using non-nuclear capabilities, or escalate to the use of nuclear weapons on any scale.”

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden spoke repeatedly in favor of a no-first-use and sole-purpose policy for U.S. nuclear weapons. But the NPR explicitly rejects both under current conditions. The public version of the NPR doesn’t explain why a no-first-use policy against nuclear attack is not possible, but it appears to trim somewhat the 2018 NPR language about an enhanced role of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear strategic attacks. And the stated goal is still “moving toward a sole purpose declaration” when possible in consultation with Allies and partners.

In that context the NPR reiterates previous “negative security assurances” that the United States “will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT [Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty] and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.”

“For all other states” the NPR warns, “there remains a narrow range of contingencies in which U.S. nuclear weapons may still play a role in deterring attacks that have strategic effect against the United States or its Allies and partners.” That potentially includes Iran, North Korea, and Pakistan.

Interestingly, the NPR states that “hedging against an uncertain future” is no longer a stated (formal) role of nuclear weapons. Hedging has been part of a strategy to be able to react to changes in the threat environment, for example by deploying more weapons or modifying capabilities. The change does not mean that the United States is no longer hedging, but that hedging is part of managing the arsenal, rather than acting as a role for nuclear weapons within US military strategy writ large.

The NPR reaffirms, consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy, that U.S. use of nuclear weapons must comply with the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) and that it is U.S. policy “not to purposely threaten civilian populations or objects, and the United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or objects in violation of LOAC.” That means that U.S. nuclear forces cannot attack cities per se (unless they contain military targets).

Nuclear Force Structure

The NPR reaffirms a commitment to the modernization of its nuclear forces, nuclear command and control and communication systems (NC3), and production and support infrastructure. This is essentially the same nuclear modernization program that has been supported by the previous two administrations.

But there are some differences. The NPR also identifies “current and planned nuclear capabilities that are no longer required to meet our deterrence needs.” This includes retiring the B83-1 megaton gravity bomb and cancelling the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). These decisions were expected and survived opposition from defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists.

Although the NPR has decided to move forward with retirement of the B83-1 bomb due to increasing limitations on its capabilities and rising maintenance costs, the NPR appears to hint at a replacement weapon “for improved defeat” of hard and deeply buried targets. The new weapon is not identified.

The NPR concludes that “SLCM-N was no longer necessary given the deterrence contribution of the W76-2, uncertainty regarding whether SLCM-N on its own would provide leverage to negotiate arms control limits on Russia’s NSNW, and the estimated cost of SLCM-N in light of other nuclear modernization programs and defense priorities.” This language is more subtle than the administration’s recent statement rebutting Congress’ attempt to fund the SLCM-N, which states:

“The Administration strongly opposes continued funding for the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) and its associated warhead. The President’s Nuclear PostureReview concluded that the SLCM-N, which would not be delivered before the 2030s, is unnecessary and potentially detrimental to other priorities. […] Further investment in developing SLCM-N would divert resources and focus from higher modernization priorities for the U.S. nuclear enterprise and infrastructure, which is already stretched to capacity after decades of deferred investments. It would also impose operational challenges on the Navy.

In justifying the cancelation of the SLCM-N, the NPR spells out the existing and future capabilities that adequately enable regional deterrence of Russia and China. This includes the W76-2 (the low-yield warhead for the Trident II D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile proposed and deployed under the Trump administration), globally-deployed strategic bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, and dual-capable fighter aircraft such as as the F-35A equipped with the new B61-12 nuclear bomb.

The NPR concludes that the W76-2 “currently provides an important means to deter limited nuclear use.” However, the review leaves the door open for its possible removal from the force structure in the future: “Its deterrence value will be re-evaluated as the F-35A and LRSO are fielded, and in light of the security environment and plausible deterrence scenarios we could face in the future.”

The review also notes that “[t]he United States will work with Allies concerned to ensure that the transition to modern DCA [dual-capable aircraft] and the B61-12 bomb is executed efficiently and with minimal disruption to readiness.” The release of the NPR coincides with the surprise revelation that the United States has sped up the deployment of the B61-12 in Europe. Previously scheduled for spring 2023, the first B61-12 gravity bombs will now be delivered in December 2022, likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Putin’s nuclear belligerency. Given that the Biden administration has previously taken care to emphasize that its modernization program and nuclear exercises are scheduled years in advance and are not responses to Russia’s actions, it is odd that the administration would choose to rush the new bombs into Europe at this time.

The NPR appears to link the non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe more explicitly to recent Russian aggression. “Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the occupation of Crimea in 2014, NATO has taken steps to ensure a modern, ready, and credible NATO nuclear deterrent.” While that is true, some of those steps were already underway before 2014 and would have happened even if Russia had not invaded Ukraine. This includes extensive modernizations at the bases and of the weapons and adding the United Kingdom to the nuclear storage upgrades. But the NPR also states that “Further steps are needed to fully adapt these forces to current and emerging security conditions,” including to “enhance the readiness, survivability and effectiveness of the DCA mission across the conflict spectrum, including through enhanced exercises…”

In the Pacific region, the NPR continues and enhances extended deterrence with U.S. capabilities and deepened consultation with Allies and partners. The role of Australia appears to be increasing. An overall goal is to “better synchronize the nuclear and non-nuclear elements of deterrence” and to “leverage Ally and partner non-nuclear capabilities that can support the nuclear nuclear deterrence mission.” The last part sounds similar to the so-called SNOWCAT mission in NATO where Allies support the nuclear strike mission with non-nuclear capabilities.

Nuclear-Conventional Integration

Although the integration of nuclear and conventional capabilities into strategic deterrence planning has been underway for years, the NPR seeks to deepen it further. It “underscores the linkage between the conventional and nuclear elements of collective deterrence and defense” and adopts “an integrated deterrence approach that works to leverage nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities to tailor deterrence under specific circumstances.”

This is not only intended to make deterrence more flexible and less nuclear focused when possible, but it also continues the strategy outlined in the 2010 NPR and 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons by relying more on new conventional capabilities.

According to the NPR, “Non-nuclear capabilities may be able to complement nuclear forces in strategic deterrence plans and operations in ways that are suited to their attributes and consistent with policy on how they are employed.” Although further integration will take time, the NPR describes “how the Joint Force can combine nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities in complementary ways that leverage the unique attributes of a multi-domain set of forces to enable a range of deterrence options backstopped by a credible nuclear deterrent.” An important part of this integration is to “better synchronize nuclear and non-nuclear planning, exercises, and operations.”

Beyond force structure issues, this effort also appears to be a way to “raise the nuclear threshold” by reducing reliance on nuclear weapons but still endure in regional scenarios where an adversary escalates to limited nuclear use. In contrast, the 2018 NPR sought low-yield non-strategic “nuclear supplements” for such a scenario, and specifically named a Russian so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” scenario as a potentially possibility for nuclear use.

Moreover, conventional integration can also serve to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons in response to non-nuclear strategic attacks, and could therefore pave the way for a sole-purpose policy in the future (see also An Integrated Approach to Deterrence Posture by Adam Mount and Pranay Vaddi).

Finally, increasing conventional capabilities in deterrence planning also allows for deeper and better integration of Allies and partners without having to rely on more controversial nuclear arrangements.

A significant challenge of deeper nuclear-conventional integration in strategic deterrence is to ensure that it doesn’t blur the line between nuclear and conventional war and inadvertently increase nuclear signaling during conventional operations.

Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

The NPR correctly concludes that deterrence alone will not reduce nuclear dangers and reaffirms the U.S. commitment to arms control, risk reduction, and nonproliferation. It does so by stating that the United States will pursue “a comprehensive and balanced approach” that places “renewed emphasis on arms control, non-proliferation, and risk reduction to strengthen stability, head off costly arms races, and signal our desire to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons globally.”

The Biden administration’s review contains significantly more positive language on arms control than can be found in the Trump administration’s NPR. The NPR concludes that “mutual, verifiable nuclear arms control offers the most effective, durable and responsible path to achieving a key goal: reducing the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. strategy.”

In that vein, the review states a willingness to “expeditiously negotiate a new arms control framework to replace New START,” as well as an expansive recommitment to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty” (CTBT), and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). However, the authors take a negative view of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), stating that the United States does not “consider the TPNW to be an effective tool to resolve the underlying security conflicts that lead states to retain or seek nuclear weapons.”

Although the NPR states that “major changes” in the role of U.S. nuclear weapons against Russia and China will require verifiable reductions and constraints on their nuclear forces, it also concludes that there “is some opportunity to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our strategies for [China] and Russia in circumstances where the threat of a nuclear response may not be credible and where suitable non-nuclear options may exist or may be developed.” The NPR does not identify what those scenarios are.

Looking Ahead

Many of the activities described in the NPR are already well underway. Now that the NPR has been completed and published, the Pentagon will produce an NPR implementation plan that identifies specific decisions to be carried out.

Flowing from the reviews that were done in preparation of the NPR, the White House will move forward with an update to the nuclear weapons employment guidance. This guidance will potentially include changes to the strike plans and the assumptions and the assumptions and requirements that underpin them.

The Biden administration must use this opportunity to scrutinize more closely the simulations and analysis that U.S. Strategic Command is using to set nuclear force structure requirements.

––

Additional analysis can be found on our FAS Nuclear Posture Review Resource Page.

For an overview of global modernization programs, see our annual contribution to the SIPRI Yearbook and our Status of World Nuclear Forces webpage. Individual country profiles are available in various editions of the FAS Nuclear Notebook, which is published by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and is freely available to the public.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

New NASIC Report Appears Watered Down And Out Of Date

The US Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published a new version of its widely referenced Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report.

The agency normally puts out an updated version of the report every four years. The previous version dates from 2017.

The 2021 report (dated 2020) provides information on developments in many countries but is clearly focused on China, Iran, North Korea, and Russia. Especially the North Korean data is updated because of the significant developments since 2017.

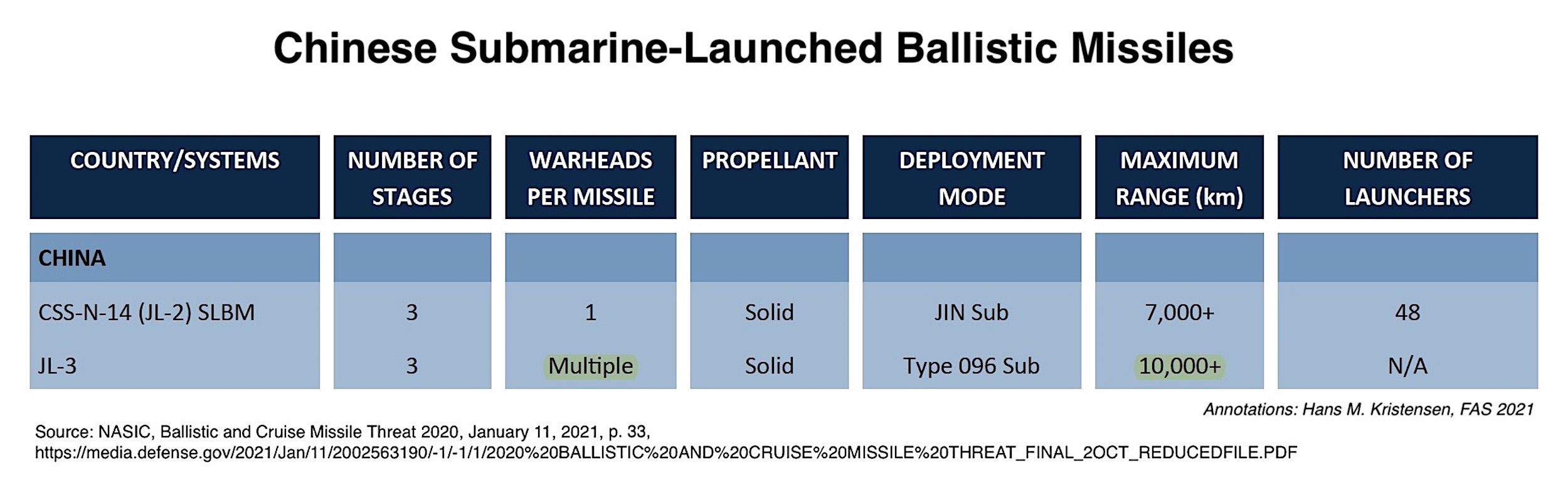

The most interesting new information in the updated report is probably that the new Chinese JL-3 sea-launched ballistic missile (SLBM) is capable of carrying multiple warheads.

Overall, however, the new report may be equally interesting because of what it does not include. There are a number of cases where the report is scaled back compared with previous versions. And throughout the report, much of the data clearly hasn’t been updated since 2018. In some places it is even inconsistent and self-contradicting.

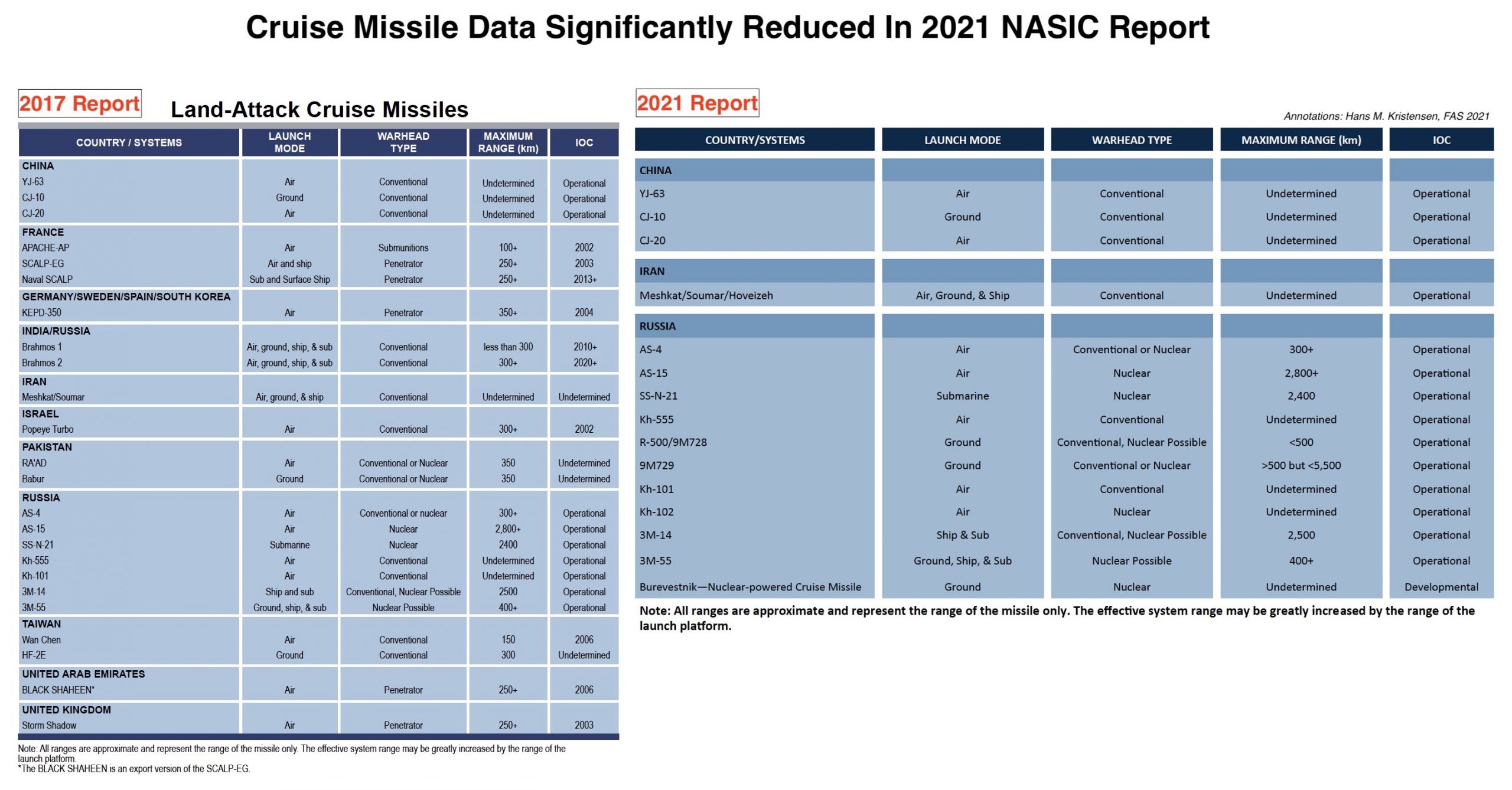

The most significant data reduction is in the cruise missile section where the report no longer lists countries other than Russia, China, and Iran. This is a significant change from previous reports that listed a wide range of other countries, including India and Pakistan and many others that have important cruise missile programs in development. The omission is curious because the report in all ballistic missile categories includes other countries.

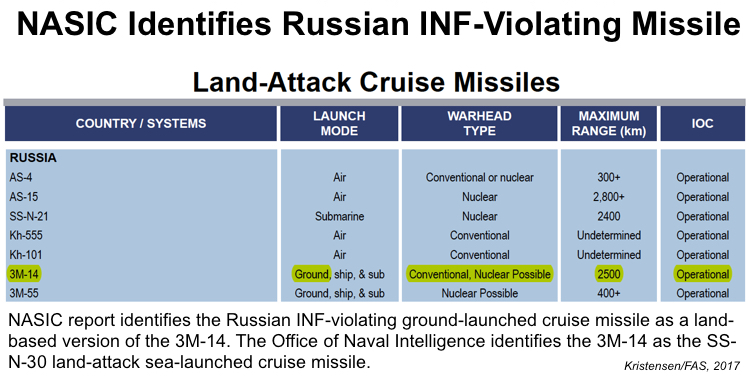

Cruise missile data is significantly reduced in the new NASIC report compared with the previous version from 2017. Click on image to view full size.

Other examples of reduced data include the overview of ballistic missile launches, which for some reason does not show data for 2019 and 2020. Nor is it clear from the table which countries are included.

Also, in some descriptions of missile program developments the report appears to be out of date and not update on recent developments. This includes the Russian SS-X-28 (RS-26 Rubezh) shorter-range ICBM, which the report portrays as an active program but only presents data for 2018. Likewise, the report does not mention the two additional boats being added to the Chinese SSBN fleet. Moreover, the new section with air-launched ballistic missiles only includes Russia but leaves out Chinese developments and only appears to include data up through early 2018.

Whether these omissions reflect changes in classification rules, chaos is the Intelligence Community under the Trump administration, or simply oversight is unknown.

Below follows highlights of some of the main nuclear issues in the new report.

Russian Nuclear Forces

Information about Russian ballistic and cruise missile programs dominate the report, but less so than in previous versions. NASIC says Russia currently has approximately 1,400 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs and SLBMs, a reduction from the “over 1,500” reported in 2017. The new number is well known from the release of New START data and is very close to the 1,420 warheads we estimated in our Russian Nuclear Notebook last year.

NASIC repeats the projection from 2017, that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints….”

The statement that “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs” is curious, however, because would imply the SLBM force is loaded with fewer warheads than normally assumed. The warhead loading attributed to the SS-N-32 (Bulava) is 6, the number declared by Russia under the START treaty, and less than the 10 warheads that is often claimed by unofficial sources.

The new version describes continued development of the SS-28 (RS-26 (Rubezh) shorter-range ICBM suspected by some to actually be an IRBM. But the report only lists development activities up through 2018 and nothing since. The system is widely thought to have been mothballed due to budget constraints.

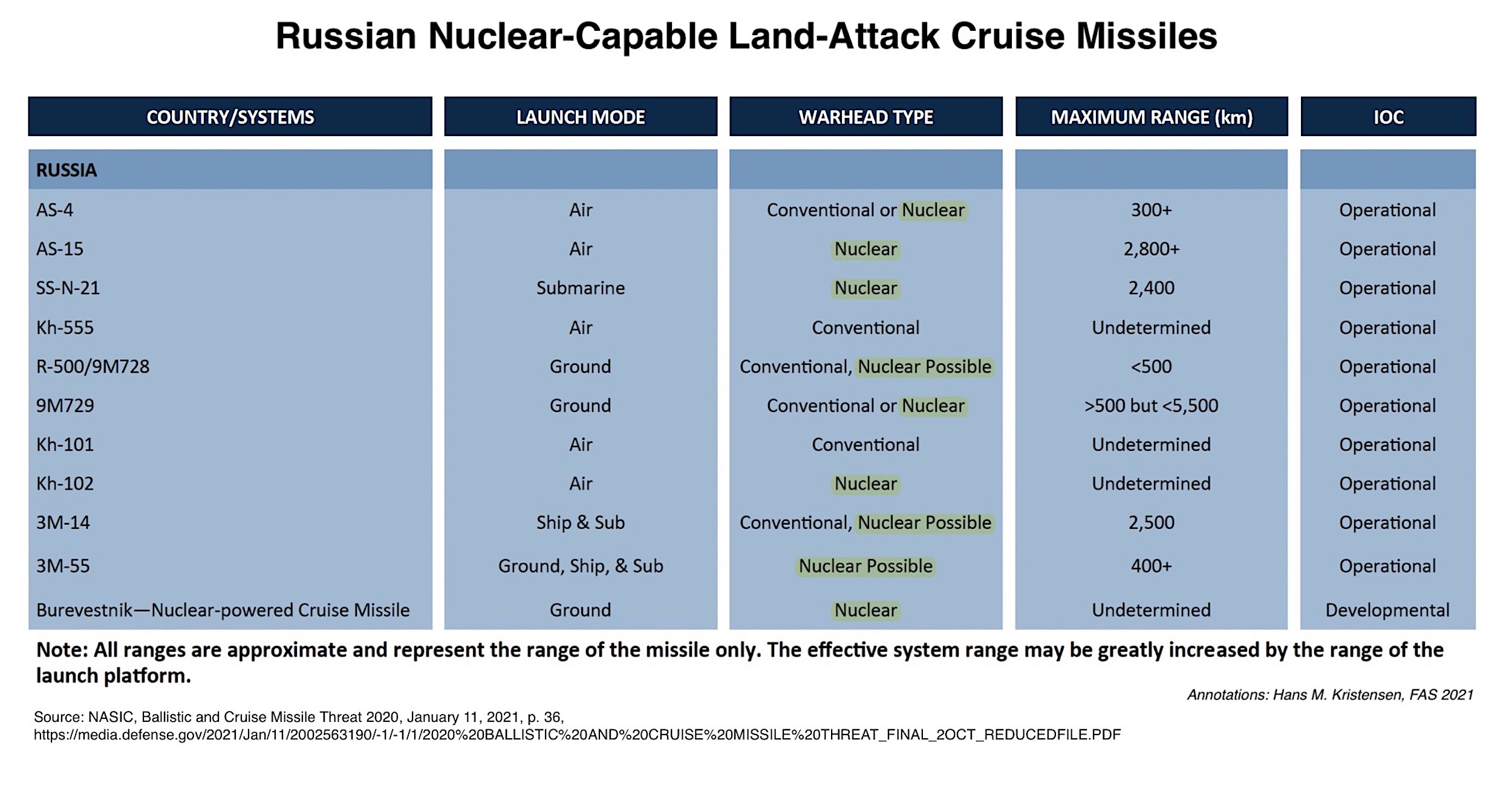

The cruise missile section attributes nuclear capability – or possible nuclear capability – to most of the Russian missiles listed. Six systems are positively identified as nuclear, including the Kh-102, which was not listed in the 2017 report. Two of the nuclear systems are dual-capable, including the 9M729 (SSC-8) missile the US said violated the now-abandoned INF treaty, while 3 missiles are listed as “Conventional, Nuclear Possible.” That includes the 9M728 (R-500) cruise missile (SSC-7) launched by the Iskander system, the 3M-14 (Kalibr) cruise missile (SS-N-30), and the 3M-55 (Yakhont, P-800) cruise missile (SS-N-26).

NASIC attributes nuclear capability to nine Russian land-attack cruise missiles, three of them “possible.” Click on image to view full size.

The designation of “nuclear possible” for the SS-N-30 (3M-14, often called the Kalibr even though Kalibr is strictly speaking the name of the launcher system) is curious because the Russian government has clearly stated that the missile is nuclear-capable.

Chinese Nuclear Forces

The biggest news in the China section of the NASIC report is that the new JL-3 SLBM that will arm the next-generation Type 096 SSBN will be capable of delivering “multiple” warheads and have a range of more than 10,000 kilometers. That is a significant increase in capability compared with the JL-2 SLBM currently deployed on the Jin-class SSBNs and is likely part of the reason for the projection that China’s nuclear stockpile might double over the next decade.

NASIC reports that China’s next-generation JL-3 SLBM will be capable of carrying “multiple” warheads. Click on image to view full size.

Despite this increased range, however, a Type 096 operating from the current SSBN base in the South China Sea would not be able to strike targets in the continental United States. To be able to reach targets in the continental United States, an SSBN would have to launch its missile from the Bohai Sea. That would bring almost one-third of the continental United States within range. To target Washington, DC, however, a Type 096 SSBN would still have to deploy deep into the Pacific.

The new DF-41 (CSS-20) has lost its “-X-“ designation (CSS-X-20), which indicates that NASIC considers the missile has finished development is now being deployed. A total of 16+ launchers are listed, probably based on the number attending the 2019 parade in Beijing and the number seen operating in the Jilantai training area.

The number of DF-31A and DF-31AG launchers is very low, 15+ and 16+ respectively, which is strange given the number of bases observed with the launchers. Of course, “+” can mean anything and we estimate the number of launchers is probably twice that number. Also interesting is that the DF-31AG is listed as “UNK” (unknown) for warheads per missile. The DF-31A is listed with one warhead, which suggests that the AG version potentially could have a different payload. Nowhere else is the AG payload listed as different or even multiple warheads.

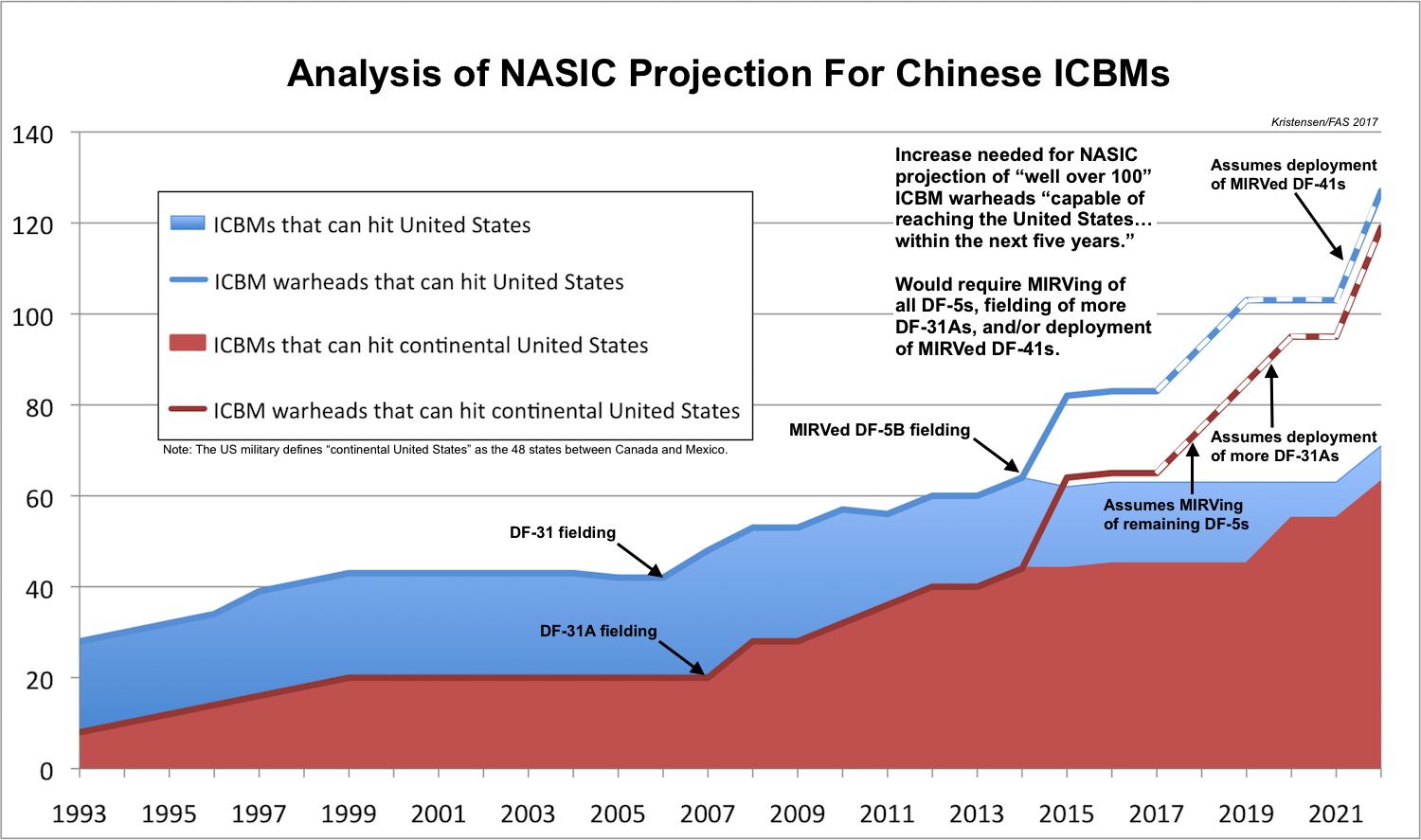

The NASIC report projection for the increase in Chinese nuclear ICBM warheads that can reach the United States is inconsistent and self-contradicting. In one section (p. 3) the report predicts “the number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States potentially expanding to well over 200 within the next 5 years.” But in another section (p. 27), the report states that the “number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs capable of threatening the United States is expected to grow to well over 100 in the next 5 years.” The projection of “well over 100” was also listed in the 2017 report, and the “well over 200” projection matches the projection made in the DOD annual report on Chinese military developments. So the authors of the NASIC might simply have forgotten to update the text.

On Chinese shorter-range ballistic missiles, the NASIC report only mentions DF-21A (CSS-5 Mod 2) as nuclear, but not the CSS-5 Mod 6 version. The Mod 6 version (potentially called DF-21E) was first mentioned in the 2016 DOD report on Chinese military developments and has been included since.

Newer missiles finally get designations: The dual-capable DF-26 is called the CSS-18, and the conventional (possibly) DF-17 is called the CSS-22. NASIC continues to list the DF-26 range as less (3,000+ km) than the annual DOD China report (4,000 km).

An in case anyone was tempted, no, none of China’s cruise missiles are listed as nuclear-capable.

Pakistani Nuclear Forces

The report provides no new information about Pakistani nuclear-capable ballistic missiles. As with several other sections in the report, the information does not appear to have been updated much beyond 2018, if at all. As such, status information should be read with caution.

The Shaheen-III MRBM is still not deployed, nor is the Ababeel MRBM that NASIC describes as a “MIRV version.” It has only been flight-tested once.

The tactical nuclear-capable NASR is listed with a range of 60 km, the same as in 2017, even though the Pakistani government has since claimed the range has been extended to 70 km.

Because the new NASIC report no longer includes data on Pakistan’s cruise missiles, neither the Babur nor the RAAD programs are described. Nor is any information provided about the efforts by the Pakistani navy to develop a submarine-launched nuclear-capable cruise missile.

Indian Nuclear Forces

Similar to other sections of the report, the data on Indian programs are tainted by the fact that some information does not appear to have been updated since 2018, and that the cruise missile section does not include India at all.

According to the report, Agni II and Agni III MRBMs are still deployed in very low numbers, fewer than 10 launchers, the same number reported in 2017. That number implies only a single brigade of each missile. But, again, it is not clear this information has actually been updated.

Nor are the Agni IV or the Agni V listed as deployed yet.

North Korean Forces

The North Korean sections are main interesting because of the inclusion of data on several systems test-launched since the previous report in 2017. This contrasts several other data set in the report, which do not appear to have been updated past 2018. But since the North Korean long-range tests occurred in 2017, this may explain why they are included.

NASIC provides official (unclassified) range estimates for these missiles:

The Hwasong-12 IRBM range has been increased from 3,000+ km in 2017 to 4,500+ km in the new report.

On the ICBMs, the Taepo Dong 2 no longer has a range estimate. The Hwasong-13 and Hwasong-14 range estimates have been raised from the generic 5,500+ km in the 2017 report to 12,000 km and 10,000+ km, respectively, in the new report, and the new Hwasong-15 has been added with a range estimate of 12,000+ km. The warhead loading estimates for the Hwasong-14 and Hwasong-15 are “unknown” and none of the ICBMs are listed as deployed.

On submarine-launched missiles, the NASIC report lists two: the Puguksong-1 and Pukguksong-3. Both have range estimates of 1,000+ km and the warhead estimate for the Pukguksong-3 is unknown (“UNK”). Neither is deployed. The new Pukguksong-4 paraded in October 2020 is not listed, not is the newest Pukguksong-5 displayed in early 2021 mentioned.

Additional background information:

• Russian nuclear forces, 2020

Conventional Deterrence of North Korea

The debate over whether North Korea could be deterred was eclipsed by the onset of negotiations in 2018. Yet, the last three years have been marked by rapid advancements in the regime’s military capabilities and apparent evolution in its military strategy, which now relies on the threat of preemptive attacks against allied conventional forces to limit damage to the regime. Many of the standard assumptions that have underwritten U.S.-ROK deterrence posture are now obsolete. The deterrence balance on the peninsula is now between DPRK nuclear forces and allied conventional forces. Allied deterrence posture that depends on the threat of nuclear use or invasion will be insufficient to deter the regime from attempting to impose a fait accompli to forcibly achieve limited objectives. The alliance must place conventional deterrence at the center of its planning to ensure that U.S. conventional forces can effectively supplement South Korea’s ability growing ability to defend itself from limited aggression. The proposed posture requires closer coordination and additional capability, a difficult but necessary step at a time when the alliance faces severe friction.

Report of the International Study Group on North Korea Policy

The FAS International Study Group on North Korea Policy convened to develop a strategy toward a North Korea that will in all likelihood remain nuclear-armed and under the control of the Kim family for the next two decades. The composition of the group reflects a conviction that a sustainable and realistic strategy must draw on the expertise of new voices from a broader range of disciplines coordinating across national boundaries—and cannot be met by replicating outdated assumptions and methods. In the pages that follow, the study group issues recommendations to the United States and its allies—most directly South Korea and Japan, but also to countries in Europe, Southeast Asia, and Oceania who hold broadly shared objectives even as they prioritize issues of specific national concern.

DoD: North Korea is Committed to its Nuclear Forces

“Pyongyang portrays nuclear weapons as its most effective way to deter the threat from the United States,” the Department of Defense says in a newly disclosed report to Congress on North Korean security policy.

“North Korea’s primary strategic goal is perpetual Kim family rule via the simultaneous development of its economy and nuclear weapons program — a two-pronged policy known as byungjin.” See Military and Security Developments Involving the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, 2017, Office of the Secretary of Defense, February 2018.

The DoD assessment presents an uncompromisingly hostile North Korea that is committed to nuclear weapons. The report provides no reason to anticipate a reconsideration or a reorientation of the country’s nuclear policies, though that is the entire premise of the upcoming June 12 summit meeting between President Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong Un.

The report, generated in February 2018, has not been posted online by the Department of Defense. (Update: now posted by DoD.) It was first reported last week by Anthony Capaccio of Bloomberg. See Pentagon Says North Korea’s Regime Has Staked Its Survival on Nuclear Weapons, May 17.

“North Korea ultimately seeks the capability to strike the continental United States with a nuclear-armed ICBM,” the Pentagon report said. “This pursuit supports North Korea’s strategy of deterring the United States as well as weakening U.S. alliances in the region by casting doubt on the U.S.commitment to extended deterrence. In the long term, North Korea may see nuclear weapons as permitting more frequent coercive behavior and may further increase Kim Jong Un’s tolerance for risk.”

The DoD report, required by statute and reflecting developments only through December 15, 2017, is largely consistent with previous DoD reports on the subject. It includes some new material on North Korea’s ballistic missile tests, cyber capabilities, special operations forces, and other topics.

An Airborne Defense Against North Korean ICBMs?

Could an airborne network of drone-based interceptors effectively defend against the launch of North Korean ballistic missiles? A recent assessment by physicists Richard L. Garwin and Theodore A. Postol concludes that it could.

“All of the technologies needed to implement the proposed system are proven and no new technologies are needed to realize the system,” they wrote.

Their concept envisions the deployment of a number of Predator B drones loitering outside of North Korean airspace each bearing two boost-phase intercept missiles.

“The baseline system could technically be deployed in 2020, and would be designed to handle up to 5 simultaneous ICBM launches.”

“The potential value of this system could be to quickly create an incentive for North Korea to take diplomatic negotiations seriously and to destroy North Korean ICBMs if they are launched at the continental United States.”

See Airborne Patrol to Destroy DPRK ICBMs in Powered Flight by R.L. Garwin and T.A. Postol, November 26, 2017.

The asserted role of such a system in promoting diplomatic negotiations rests on certain assumptions about how it would be perceived and evaluated by North Korea that are not addressed by the authors here.

Negotiating with North Korea: History and Options

The alternative to military conflict with North Korea over its nuclear weapons program is to advance some kind of negotiated settlement. But what would that be? And how could it be achieved?

A new report from the Congressional Research Service summarizes the limited successes of past nuclear negotiations between the US and North Korea, including lessons learned. Looking forward, it discusses the features of possible negotiations that would need to be determined, such as the specific goals to be achieved, preconditions for negotiations (if any), the format (bilateral or multilateral), and potential linkage to other policy issues.

See Nuclear Negotiations with North Korea: In Brief, December 4, 2017.

See also Possible U.S. Policy Approaches to North Korea, CRS In Focus, September 4, 2017.

US B-1B bomber assurance missions to Korea

Two USAF B-1B Lancer bombers fly alongside a JASDF F-2 over the East China Sea, October 21, 2017. Photo: PACAF, http://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001830673/

Two USAF B-1B Lancer bombers fly alongside a JASDF F-2 over the East China Sea, October 21, 2017. Photo: PACAF, http://www.pacaf.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2001830673/

By Adam Mount

As the Trump administration has prioritized North Korea, it has expanded military exercises around the peninsula to attempt to coerce the regime and assure US allies in Seoul and Tokyo. Perhaps the most dependable signal has been B-1B bombers missions to allied airspace. Though the flights were staged regularly during the Obama administration, they have become more frequent over the last year and more assertive. A review of official press releases and public reporting places this week’s flight of a conventional B-1B bomber near the Korean peninsula as the thirteenth of 2017.

The B-1B bomber originally entered service in 1986 as a supersonic nuclear bomber intended to serve as an interim step between the aging B-52 and the stealthy B-2. The B-1B’s nuclear mission was eliminated in 1994, after which the Air Force did not expend money to maintain its nuclear certification. To meet its obligations under the START treaties, the B-1B was converted to a conventional only platform by welding a metal sleeve onto the aircraft to prevent installation of cruise missile pylons and by removing cable connections in the weapon bays necessary to arm nuclear munitions. As part of New START, Russian observers inspected these modifications in 2011 and accepted the bomber as nonnuclear.

Though effectively nonnuclear, the regional perception of the B-1B is more nuanced. South Korea regularly refers to these flights as demonstrating “strategic assets,” a term usually applied to nuclear-capable platforms. By allowing the term to refer to the intercontinental range of the aircraft in this context, the United States mollifies South Korean officials who desire frequent signals of the US nuclear commitment without devaluing their nuclear signaling options.

Perceptions of the flights are additionally complicated by the fact that North Korea regularly refers to the B-1B as a nuclear platform. For example, North Korea decried this week’s flight a “nuclear strike drill.” Whether they do so for propaganda purposes or genuinely believe the aircraft is nuclear-capable is not clear, but defense strategists must consider the possibility that Pyongyang perceives a nuclear signal, even if the US officials did not intend to send one. What is clear is that the B-1B flights are of particular concern for Pyongyang. In August, 2017, state propaganda agency KCNA described “the operational plan for making an enveloping fire at the areas around Guam” by firing four Hwasong-12 IRBMs as a way of “containing” B-1B flights. The threat was an early attempt to brandish North Korea’s new long-range missiles in an attempt to coerce the US-South Korea alliance to modify its deterrent posture.

The missions are meant to ensure interoperability with allied forces and reassure allies of US defense commitments. US defense observers now widely doubt that the missions have any deterrent value and have instead become essentially routine signals of assurance to South Korea. North Korea now expects that any major test or provocation will elicit a B-1B flight in response. The assurance value of the flights is also an open question. Though ROK officials appreciate the signal, in the wake of the North Korean ICBM and thermonuclear weapons tests, they have also reportedly sought explicit signals of the US nuclear commitment as well as new conventional military signals. As such, the flights now probably have limited value to the alliance and several observers suggest that they could be modified if North Korea proved willing to negotiate tensions reductions measures.

B-1B missions more frequent and more assertive

‘For the first two months of the Trump administration, US Pacific Air Force did not carry out B-1B flights. From March through June, there was one flight per month. Since then, the alliance has conducted two B-1B flights to Korea per month, often in direct response to North Korean missile or nuclear tests. (USAF carried out additional bilateral missions with Japan as well as flights to the South China Sea.)

The most common mission profile has been “sequenced bilateral” missions in which usually two B-1Bs depart Guam, operate with Japan Air Self-Defense Force (JASDF) fighters near Japan (often near Kyushu), then subsequently with Republic of Korea Air Force (ROKAF) fighters. About half the time, the bombers perform a simulated release of munitions or, as in (July, August, and September) release live or inert munitions onto Pilsung range, South Korea.

In September and October, the Air Force has begun to experiment with provocative new mission profiles. On 30 August, the B-1Bs were escorted for the first time by USMC F-35B aircraft from MCAS Iwakuni, Japan. The combination of the stealth fighter with the low-observable bomber will raise new concerns in Pyongyang about the abilities of their air defenses to detect and aerial intrusions. On 23 September, a B-1B mission for the first time flew Northeast of the Demilitarized Zone in international airspace. According to the US Air Force, North Korean air defenses failed to detect the flight, raising additional concerns about their capabilities.

On 11 October, CNN reported that a sequenced bilateral mission had performed a missile release drill in the East Sea (Sea of Japan), following which the B-1Bs and their ROKAF escorts crossed the peninsula and repeated the drill in the West Sea (Yellow Sea). Though B-1B exercises in the West Sea are not unprecedented, they are highly unusual. Additionally, this is the first known report of a missile release drill. The only missiles carried by the B-1B are the standard and extended-range variants of the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Munition, a long-range conventional cruise missile. Using the unclassified range of 500 miles, the JASSM-ER is capable of striking Chinese territory from most points in the East Sea and all of the West Sea. Beijing can be struck from the western half of the West Sea without flying north of the DMZ. This fact, combined with the proximity of the flight with US-ROK naval exercises in the West Sea around the time of the landmark Chinese Party Congress, suggests that the flight was an assertive signal not only to Pyongyang but also to Beijing.

Escalation risks

Though B-1B sequenced bilateral missions are now essentially routine, several trends raise the risk that these flights could contribute to military escalation.

This year’s B-1B flights occur in a political and military context distinct from previous administration. The Trump administration has through rhetorical comments and assertive military signaling around the peninsula has signaled that they could order military strikes on North Korea. In the last two weeks, the US-ROK combined forces have staged a series of highly provocative exercises ahead of Mr. Trump’s visit to the region (including major live fire naval exercises in the East and West Seas, drills to evacuate US civilians, port visits from American submarines and the USS Ronald Reagan aircraft carrier, and announcements of upcoming deployments of F-35A to Japan and a three-carrier exercise in the Pacific).

Both in exercises and in other announcements, both the United States and South Korea have openly signaled that they are training for decapitation strikes against North Korea’s leadership. The signal is intended to convey to Pyongyang that ordering an attack could place their lives directly at risk and so to deter aggression. Yet, the administration’s rhetorical emphasis on forcible denuclearization of the peninsula may also give the impression that the United States could carry out assassination strikes even absent North Korean aggression. Combined with poor situational awareness of low-observable aircraft, the statements significantly raise North Korea’s incentives to escalate any crisis, the likelihood that they perceive US operations as a prelude to attack, and the risk of nuclear use.

To date, the Trump administration has not conducted a flight of a nuclear-capable B-2 stealth bomber to Korea. In 2013, the Obama administration did carry out a prominent flight from Whiteman AFB, MO to deliver inert munitions at Pilsung, the first and last time a B-2 mission has been disclosed publicly.

However, on 28-29 October, 2017, a B-2 flew from Whiteman to an undisclosed location in the Pacific. The bomber reportedly stopped on Guam, where it swapped crews with the engines running. Though a B-2 flight to Korea is unlikely to be radically destabilizing, in the context of a frequent White House comments playing up the possibility of military action and thinly-veiled nuclear threats to North Korea, planners should be aware that dispatching a B-2 is likely to be significantly more provocative than similar missions in previous years.

In the past, the United States had generally conducted Bomber Assurance and Deterrence (BAAD) flights with B-52 bombers. Because some B-52s are nuclear-capable, these missions were widely interpreted as nuclear deterrent signals. The most recent B-52 flight was in January, 2016, following the fourth DPRK nuclear test. Since 2004, either B-1B, B-52, or B-2 bombers have been rotationally stationed in Guam as part of the “Continuous Bomber Presence” Mission. In 2003, 12 B-52s and 12 B-1B bombers were alerted in the United States and subsequently deployed to Guam after 4 North Korean MiG fighters intercepted an American surveillance plane.

Lastly, the missions may be sending precisely the opposite message from the one intended. For the last several years, the United States has continued to work to improve trilateral coordination between the United States, South Korea, and Japan in order to present North Korea with a united front. However, the sequenced bilateral missions only serve underscore the reticence of the ROKAF and JASDF to operate together. Though JASDF fighters sometimes “hand off” the US bombers to ROK pilots, trilateral missions would send a far stronger signal of cohesion and capability, especially if conducted over ROK airspace.

These considerations raise serious questions about the value of B-1B assurance flights. At a time of rapid advance in North Korea’s nuclear and missile capabilities, with a US leadership that has made statements exacerbating South Korea’s concerns that the United States could decouple from its allies, it is unlikely that routine and symbolic flights are an effective signal either for deterring Pyongyang or assuring Seoul.

The North Korean Nuclear Challenge, & More from CRS

North Korea’s rapidly maturing nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missile programs have prompted urgent reconsideration of what to do about them.

A new report from the Congressional Research Service identifies and examines seven possible directions for US policy, none of them risk-free or altogether satisfactory:

* maintaining the military status quo

* enhanced containment and deterrence

* denying DPRK acquisition of delivery systems capable of threatening the US

* eliminating ICBM facilities and launch pads

* eliminating DPRK nuclear facilities

* DPRK regime change

* withdrawing U.S. military forces

For a copy of the 67-page report (which was first reported by Bloomberg News), see The North Korean Nuclear Challenge: Military Options and Issues for Congress, October 27, 2017.

Other new and updated reports from the Congressional Research Service include the following.

Niger: Frequently Asked Questions About the October 2017 Attack on U.S. Soldiers, October 27, 2017

Taiwan: Issues for Congress, October 30, 2017

Doing Business with Iran: EU-Iran Trade and Investment Relations, CRS Insight, October 25, 2017

Renegotiating NAFTA and U.S. Textile Manufacturing, October 30, 2017

The Vacancies Act: A Legal Overview, October 30, 2017

Department of Health and Human Services Halts Cost-Sharing Reduction (CSR) Payments, CRS Legal Sidebar, October 26, 2017

GAO Issues Opinions on Applicability of Congressional Review Act to Two Guidance Documents, CRS Insight, October 25, 2017

Treasury Proposes Rule That Could Deliver a “Death Sentence” to Chinese Bank, CRS Legal Sidebar, October 30, 2017

Review of NASIC Report 2017: Nuclear Force Developments

Click on image to download copy of report. Note: NASIC later published a corrected version, available here

By Hans M. Kristensen

The National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) at Wright-Patterson AFB has updated and published its periodic Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report. The new report updates the previous version from 2013.

At a time when public government intelligence resources are being curtailed, the NASIC report provides a rare and invaluable official resource for monitoring and analyzing the status of ballistic and cruise missiles around the world.

Having said that, the report obviously comes with the caveat that it does not include descriptions of US, British, French, and most Israeli ballistic and cruise missile forces. As such, the report portrays the international “threat” situation as entirely one-sided as if the US and its allies were innocent bystanders, so it will undoubtedly provide welcoming fuel for those who argue for increasing US defense spending and buying new weapons.

Also, the NASIC report is not a top-level intelligence report that has been sanctioned by the Director of National Intelligence. As such, it represents the assessment of NASIC rather than necessarily the coordinated and combined conclusion of the US Intelligence Community.

Nonetheless, it’s a unique and useful report that everyone who follows international security and ballistic and cruise missile developments should consult.

Overall, the NASIC report concludes: “The last decade has seen a dramatic increase in ballistic missile capabilities to include accuracy, post-boost maneuverability, and combat effectiveness.” During the same period, “there has been a significant increase in worldwide ballistic missile testing.” The countries developing ballistic and cruise missile systems view them “as cost-effective weapons and symbols of national power” that “present an asymmetric threat to US forces” and many of the missiles “are armed with weapons of mass destruction.” At the same time, “numerous types of ballistic and cruise missiles have achieved dramatic improvements in accuracy that allow them to be used effectively with conventional warheads.”

Some of the more noteworthy individual findings of the new report include:

- Russia’s nuclear modernization is, despite claims by some, not a “buildup” but the size of the Russian ICBM force will continue to decline.

- The Russian RS-26 “short” SS-27 ICBM is still categorized as an ICBM (as in the 2013 report) despite claims by some that it’s an INF weapon.

- The report is the first US official document to publicly identify the ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty: 3M-14. The weapon is assessed to “possibly” have a nuclear option. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

- The Russian SS-N-26 (Oniks or Onix) anti-ship cruise missile that is currently replacing several Soviet-era cruise missiles “possibly” has a nuclear option.

- The range of the dual-capable SS-26 (Islander) SRBM is listed as 350 km (217 miles) rather than the 500-700 km (310-435 miles) often claimed in the public debate.

- The number of Chinese warheads capable of reaching the United States could increase to well over 100 in the next five years, six years sooner than predicted in the 2013 report. (The count includes warheads that can only reach Alaska and Hawaii, not necessarily all of continental United States.)

- Deployment of the Chinese DF-31/DF-31A ICBMs appears to have stalled.

- China’s long-awaited DF-41 ICBM will “possibly” be capable of carrying multiple warheads but is not yet deployed.

- Two Chinese medium-range ballistic missile types (DF-3A and DF-21 Mod 1) have been retired.

- The Chinese ground-launched DH-10 land-attack cruise missile is no longer listed as “conventional or nuclear” but only as “conventional.”

- None of North Korea’s ICBMs are listed as deployed.

Below I go into more details about the individual nuclear-armed states:

Russia

Russia is now more than halfway through its modernization, a generational upgrade that began in the mid/late-1990s and will be completed in the mid-2020s. This includes a complete replacement of the ICBM force (but at lower numbers), transition to a new class of strategic submarines, upgrades of existing bombers, replacement of all dual-capable SRBM units, and replacement of most Soviet-era naval cruise missiles with fewer types.

The NASIC report states that “Russian in September 2014 surpassed the United States in deployed warheads capable of reaching the United States,” referring to the aggregate number reported under the New START treaty. The report does not mention, however, that Russia since 2016 has begun to reduce its deployed strategic warheads and is expected meet the treaty limit in 2018.

ICBMs: Contrary to many erroneous claims in the public debate (see here and here) about a Russia nuclear “build-up,” the NASIC report concludes that “the number of missiles in the Russian ICBM force will continue to decrease because of arms control agreements, aging missiles, and resource constraints…” This conclusion fits the assessment Norris and I have made for years that Russia is modernizing its nuclear forces but not increasing the size of the arsenal.

The report counts about 330 ICBM launchers (silos and TELs), significantly fewer than the 400 claimed by the Russian military. The actual number of deployed missiles is probably a little lower because several SS-19 and SS-25 units are in the process of being dismantled.

The development continues of the heavy Sarmat (RS-28), which looks very similar to the existing SS-18. The lighter SS-27 known as RS-26 (Rubezh or Yars-M) appears to have been delayed and still in development. Despite claims by some in the public debate that the RS-26 is a violation of the INF treaty, the NASIC report lists the missile with an ICBM range of 5,500+ km (3,417+ miles), the same as listed in the 2013 version. NASIC says the RS-26, which is designated SS-X-28 by the US Intelligence Community, has “at least 2” stages and multiple warheads.

Overall, “Russia retains over 1,000 nuclear warheads on ICBMs,” according to NASIC, another assessment that fits our estimate from the Nuclear Notebook. The NASIC report states that “most” of those missiles “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order.” (In comparison, essentially all US ICBMs are maintained on alert: see here for global alert status.)

SLBMs: The Russian navy is in the early phase of a transition from the Soviet-era Delta-class SSBNs to the new Borei-class SSBN. NASIC lists the Bulava (SS-N-32) SLBM as operational on three Boreis (five more are under construction). The report also lists a Typhoon-class SSBN as “not yet deployed” with the Bulava (the same wording as in the 2013 report), but this is thought to refer to the single Typhoon that has been used for test launches of the Bulava and not imply that the submarine is being readied for operational deployment with the missile.

While the new Borei SSBNs are being built, the six Delta-IVs are being upgrade with modifications to the SS-N-23 SLBM. The report also lists 96 SS-N-18 launchers, corresponding to 6 Delta-III SSBNs. But that appears to include 3-4 SSBNs that have been retired (but not yet dismantled). Only 2 Delta-IIIs appear to be operational, with a third in overhaul, and all are scheduled to be replaced by Borei-class SSBNs in the near future.

Cruise Missiles: The report lists five land-attack cruise missiles with nuclear capability, three of which are Soviet-era weapons. The two new missiles that “possibly” have nuclear capability include the mysterious ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has developed and deployed in violation of the INF treaty. The US first accused Russia of treaty violation in 2014 but has refused to name the missile, yet the NASIC report gives it a name: 3M-14. The weapon exists in both “ground, ship & sub” versions and is credited with “conventional, nuclear possible” warhead capability. [Note: A corrected version of the NASIC report published in June removed the reference to a “ground” version of the 3M-14.]

Ground- and sea-based versions of the 3M-14 have different designations. The Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) identifies the naval 3M-14 as the SS-N-30 land-attack missile, which is part of the larger Kalibr family of missiles that include:

- The 3M-14 (SS-N-30) land-attack cruise missile (the nuclear version might be called SS-N-30A; Pavel Podvig reported back in 2014 that he was told about an 8-meter 3M-14S missile “where ‘S’ apparently stands for ‘strategic’, meaning long-range and possibly nuclear”);

- The 3M-54 (SS-N-27, Sizzler) anti-ship cruise missile;

- The 91R anti-submarine missile.

The US Intelligence Community uses a different designation for the GLCM version, which different sources say is called the SSC-8, and other officials privately say is a modification of the SSC-7 missile used on the Iskander-K. (For public discussion about the confusing names and designations, see here, here, and here.)

The range has been the subject of much speculation, including some as much as 5,472 km (3,400 miles). But the NASIC report sets the range as 2,500 km (1,553 miles), which is more than was reported by the Russian Ministry of Defense in 2015 but close to the range of the old SS-N-21 SLCM.

The “conventional, nuclear possible” description connotes some uncertainty about whether the 3M-14 has a nuclear warhead option. But President Vladimir Putin has publicly stated that it does, and General Curtis Scaparrotti, the commander of US European Command (EUCOM), told Congress in March that the ground-launched version is “a conventional/nuclear dual-capable system.”

ONI predicts that Kalibr-type missiles (remember: Kalibr can refer to land-attack, anti-ship, and/or anti-submarine versions) will be deployed on all larger new surface vessels and submarines and backfitted onto upgraded existing major ships and submarines. But when Russian officials say a ship or submarine will be equipped with the Kalibr, that can potentially refer to one or more of the above missile versions. Of those that receive the land-attack version, for example, presumably only some will be assigned the “nuclear possible” version. For a ship to get nuclear capability is not enough to simply load the missile; it has to be equipped with special launch control equipment, have special personnel onboard, and undergo special nuclear training and certification to be assigned nuclear weapons. That is expensive and an extra operational burden that probably means the nuclear version is only assigned to some of the Kalibr-equipped vessels. The previous nuclear land-attack SLCM (SS-N-21) is only assigned to frontline attack submarines, which will most likely also received the nuclear SS-N-30. It remains to be seen if the nuclear version will also go on major surface combatants such as the nuclear-propelled attack submarines.

The NASIC report also identifies the 3M-55 (P-800 Oniks (Onyx), or SS-N-26 Strobile) cruise missile with “nuclear possible” capability. This weapon also exists in “ground, ships & sub” versions, and ONI states that the SS-N-26 is replacing older SS-N-7, -9, -12, and -19 anti-ship cruise missiles in the fleet. All of those were also dual-capable.

It is interesting that the NASIC report describes the SS-N-26 as a land-attack missile given its primary role as an anti-ship missile and coastal defense missile. The ground-launched version might be the SSC-5 Stooge that is used in the new Bastion-P coastal-defense missile system that is replacing the Soviet-era SSC-1B missile in fleet base areas such as Kaliningrad. The ship-based version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the nuclear-propelled Kirov-class cruisers and Kuznetsov-class aircraft carrier. Presumably it will also replace the SS-N-12 on the Slava-class cruisers and SS-N-9 on smaller corvettes. The submarine version is replacing the SS-N-19 on the Oscar-class nuclear-propelled attack submarine.

NASIC lists the new conventional Kh-101 ALCM but does not mention the nuclear version known as Kh-102 ALCM that has been under development for some time. The Kh-102 is described in the recent DIA report on Russian Military Power.

Short-range ballistic missiles: Russia is replacing the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) missile with the SS-26 (Iskander-M), a process that is expected to be completed in the early-2020s. The range of the SS-26 is often said in the public debate to be the 500-700 km (310-435 miles), but the NASIC report lists the range as 350 km (217 miles), up from 300 km (186 miles) reported in the 2013 version.

That range change is interesting because 300 km is also the upper range of the new category of close-range ballistic missiles. So as a result of that new range category, the SS-26 is now counted in a different category than the SS-21 it is replacing.

China

The NASIC report projects the “number of Chinese ICBM nuclear warheads capable of reaching the United States could expand to well over 100 within the next 5 years.” Four years ago, NASIC projected the “well over 100” warhead number might be reached “within the next 15 years,” so in effect the projection has been shortened by 6 years from 2028 to 2022.

One of the reasons for this shortening is probably the addition of MIRV to the DF-5 ICBM force (the MIRVed version is know as DF-5B). All other Chinese missiles only have one warhead each (although the warheads are widely assumed not to be mated with the missiles under normal circumstances). It is unclear, however, why the timeline has been shortened.

The US military defines the “United States” to include “the land area, internal waters, territorial sea, and airspace of the United States, including a. United States territories; and b. Other areas over which the United States Government has complete jurisdiction and control or has exclusive authority or defense responsibility.”

So for NASIC’s projection for the next five years to come true, China would need to take several drastic steps. First, it would have to MIRV all of its DF-5s (about half are currently MIRVed). That would still not provide enough warheads, so it would also have to deploy significantly more DF-31As and/or new MIRVed DF-41s (see graph below). Deployment of the DF-31A is progressing very slowly, so NASIC’s projection probably relies mainly on the assumption that the DF-41 will be deployed soon in adequate numbers. Whether China will do so remains to be seen.

China currently has about 80 ICBM warheads (for 60 ICBMs) that can hit the United States. Of these, about 60 warheads can hit the continental United States (not including Alaska). That’s a doubling of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States (including Guam) over the past 25 years – and a tripling of the number of warheads that can hit the continental United States. The NASIC report does not define what “well over 100” means, but if it’s in the range of 120, and NASIC’s projection actually came true, then it would mean China by the early-2020s would have increased the number of ICBM warheads that can hit the United States threefold since the early 1990s. That a significant increase but obviously but must be seen the context of the much greater number of US warheads that can hit China.

Land-Based Ballistic Missiles: The report describes the long and gradual upgrade of the Chinese ballistic missile force. The most significant new development is the fielding of the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) with 16+ launchers. The missile was first displayed at the 2015 military parade, which showed 16 launchers – potentially the same 16 listed in the report. NASIC sets the DF-26 range at 3,000+ km (1,864 miles), 1,000 km less than the 2017 DOD report.

China does not appear to have converted all of its DF-5 ICBMs to MIRV. The report lists both the single-warhead DF-5A and the multiple-warhead DF-5B (CSS-4 Mod 3) in “about 20” silos. Unlike the A-version, the B-version has a Post-Boost Vehicle, a technical detail not disclosed in the 2013 report. A rumor about a DF-5C version with 10 MIRVs is not confirmed by the report.