To scale up climate solutions, local governments need to accelerate system changes

When I ran for city council in Boulder, Colorado in 2023, everyone talked about climate change. Forum after forum, all ten candidates spoke up for the climate.

And cities saying climate change matters is typical. The number of US cities with adopted climate action plans is in the hundreds.

That’s what we need, since cities drive the bulk of greenhouse gas emissions and are on the front lines of climate havoc.

More specifically, for large-scale climate solutions to work, cities have to really stretch. That’s according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which says cities need to rapidly become compact, efficient, electrified, and nature‑rich urban ecosystems where we take better care of each other and avoid locking in more sprawl and fossil‑fuel dependence.

Yet, big-picture progress in the United States is critically insufficient. Those are the words of Climate Action Tracker, an independent scientific analysis evaluating climate commitments. The US has pledged to reduce 2030 GHG emissions levels by 50–52% below 2005, yet the latest projections show we are on track to achieve at best only 29–39%—assuming no further backsliding.

And earlier this month, the Trump administration withdrew our federal government from the international climate agreement process.

So when local governments say “we’re on it,” what is a concerned citizen to think?

What local government climate solutions look like

Climate advocates are used to talking about climate action. But for local governments, the measuring stick for climate progress isn’t simply action. What counts is measurable progress towards specific, substantive transitions.

Transitions to walkable, compact neighborhoods where abundant, space-efficient middle housing near jobs and services let most residents meet daily needs within a short walk or bike ride, reducing trip lengths and housing and transport costs.

To transit-rich, highly bikeable towns where frequent, accessible service and a connected, protected network allow seniors and youth travel independently and where per-capita car dependence falls.

To fully-electrified communities in which homes and transportation run on clean, distributed power, working efficiently, that delivers lower bills, healthier indoor air, and outage resilience, with benefits accruing equitably to residents.

To enhanced landscapes of bioswales, permeable streets, restored wetlands, and drought- and fire-resilient shade trees that cool neighborhoods, absorb stormwater, and buffer heat, flood, and smoke risks.

To resilient local food systems that blend urban agriculture with regional producers, food hubs, cold storage, and compost-to-soil loops to deliver reliable, affordable, nutritious food even during heat, drought, or supply disruptions.

There is good news: The transitions we need, and the solutions and capacity we need to implement them, are showing new signs of life. That’s evident in two trends.

One trend is local governments playing a bigger role in climate solutions. The number of U.S. cities reporting to the CDP, a global system for disclosing climate progress, has grown to over 150. Now more than 200 US cities have committed to 100 percent clean electricity. And cities’ climate action plans are showing a visible shift from a focus on municipal operations to community‑wide impacts of buildings, transportation, and waste, and more sophisticated thinking about resilience.

As the federal government has retreated, advocates are increasingly realizing cities and counties have tools to lead. Local governments manage streets, land use, buildings, public fleets, transit, and major service contracts. They can strongly influence state-level actors, like energy utilities and air quality programs, and be providers of those services directly.

There is proof of this awakening in the large numbers of people suddenly running for local office on climate. Political organizing coalitions such as Run on Climate and Climate Cabinet helped elect more than 50 local leaders running on climate in 2025. One of the year’s most high-profile candidates, Zohran Mamdani, won with “fast and free” buses–one of the measures IPCC has highlighted as a meaningful mitigation measure that saves more money than it costs–as a centerpiece of his campaign.

The other trend is a greater focus on wellbeing. Research included in the latest IPCC report shows demand-side measures can cut end-use emissions by roughly 40 to 70 percent by 2050 while improving daily life and making communities stronger. And wellbeing is the currency of local governments and local politics. Concrete quality of life issues dominate local elections and policymaking, which is where climate action takes root—or doesn’t.

Climate action prompted by a desire for healthier, happier, and less expensive lives is happening. People are adopting electric cars, e-bikes, heat pumps, and induction stoves because they work better, are cheaper to operate, and healthier. The intersection of climate solutions and wellbeing is central to a 2025 bestseller Abundance and to the national conversation it kicked off about defining and achieving “abundance.” The topic of wellbeing was a bright spot at the COP30 climate talks via the World Health Organization’s report, “Delivering the Belém Health Action Plan.”

These two trends reinforce each other. Local governments oversee the services where wellbeing, decarbonization, and resilience meet. When those services are designed as a system, investments can compound to create more value for more people, who then have a stake in continuing the transition. And the importance of rallying around local governments to carry climate solutions forward is becoming clearer as U.S. national policy looks structurally less reliable than most experts used to think.

Difficult conditions for change

But local governments face headwinds. Existing policies and markets, like those that have created widespread car dependence and extensive natural gas systems, create momentum that favors the status quo and encourages continued investments that lock us in further. Simply put, it’s easiest to keep doing it the way we’ve done it before, and then we dig ourselves in deeper.

Local governments purposefully design systems to keep things stable. Most likely, whatever your town or county is doing is based on the direction of long-term plans, from departmental plans to bigger comprehensive plans. Those plans often come up for renewal only every few years or longer, and if you miss that window or fail to follow procedures, making big change is nearly impossible. Related, local governments tend to have policies and practices for conducting community engagement that deliberately create a high bar for making major turns.

On top of all that, local governments in the U.S. are suffering a long-term decline in investment that leaves them with significant and growing cash flow constraints, heavy workloads, limited time to deliberate, and pressure to deliver. The pandemic and recent national political forces reduce their maneuverability even more.

Political will necessary but not sufficient—concrete transitions are needed

In order to drive climate transitions under such tough conditions, political will is necessary but it is not sufficient. For local governments to scale up climate solutions, they need to take tangible, visible steps to change systems, consistent with evidence-based recommendations, outlined by institutions like the IPCC.

Here is what that can look like – and what advocates can look to encourage:

1. Transition plans

Climate issues touch everything, so all local governments can point to doing climate things. But the difference between lists of activities and high-reward strategic commitments that make good use of time is everything. The latter requires a clear plan to make transitions happen, with defined outcomes and milestones, and dogged pursuit.

Ambitious climate action at the local government level means being clear about the transition(s) the community is focused on, which could include the previously mentioned examples, along with what successful completions looks like and by when. This involves working on at least two tracks concurrently—both integrating ambitious transformations into long-term planning exercises, for which adopting changes may or may not be available right away, and taking whatever more tactical action is possible now to support such planning and concrete action to the fullest extent possible.

- Transition plans might consider: What needs to be different? Who are the elected officials and partners needed to make the transition work? What barriers could inhibit progress, and what is the strategy for overcoming them? What are the key inflection points in behavior adoption, and what is the change model to reach them?

2. User experience

Cities often add a bike lane in one place or restore a bus line in another. What truly changes behavior is a complete experience that makes the pro-climate option the intuitive choice. Kids can bike around town without parents fearing they could be hit by a driver. You can count on bringing a large electric bike anywhere and park it safely. Buses are within a 10-minute walk of home and arrive every 10 minutes. Utility investments in electrification actually lower monthly bills. To make climate transitions attractive and sticky, we have to confront gaps that get in the way of people’s experience from their vantage point.

A practical opportunity for local governments is to use the tools of user experience (“UX”) and be responsible for how the ecosystem works and feels from the immersive standpoint of users. UX is an interdisciplinary field that uses research, psychology, and design to remove friction and ensure a seamless journey for users.

- Some questions for managing the user experience: Who is/are the transition(s) for—who are the “users” involved that will experience change? What do they need to do and stick with to make the transition work? What performance measures are needed to constitute progress, and how do we get elected officials and executives to care about them? Where are there persistent, hard-to-reach gaps that can be spotlighted as “known issues” for partners and other jurisdictions to see and possibly be helpful with? What are the gaps between our intent and reality, and how can we overcome them?

3. Public service delivery

One of the core jobs of local government is to provide public services like zoning, safe transportation, building standards, air quality protections, and emergency management. Providing services is also generally the justification for spending public money. And services are where the planning activities that local governments tend to be so careful about materialize in the real world. So if local governments are going to be engines of climate action, then day-to-day service delivery—their core product—is where most of that action will show up. Climate action will appear in what gets approved, funded, built, maintained, enforced, measured, and improved.

Local governments already deliver public services. So the opportunity is to evaluate how core local government services can or should be tuned and/or reorganized to drive climate and resilience outcomes. This includes formal adoption in comprehensive plans, capital improvement programs, and strategic plans, and clear alignment with budget priorities. When leaders routinely report on progress and adjust course publicly, it signals that climate transitions are a core organizational responsibility rather than a side project.

- An evaluation of services might consider: How is climate action aligned with where money is actually spent? What changes in standards, contracts, and operations are needed to lock in better outcomes? How can the thinking and tools of service development improve user experiences?

4. High-level ownership

Plans only come to life when people who have the right level of power and accountability own delivery. Inside local government, that means both the elected body (mayor, city council, and/or their equivalents) and executives (city manager, their deputies, and in the case of a “strong mayor” form of government, the mayor) adopt the initiative as their own. Roles and accountability are defined and gaps are addressed. Resources are allocated through direct investments and through partnerships that expand capacity.

High-level ownership of climate solutions in local government happens when transitions are included in the agency’s highest-level plans and strategies.This includes formal adoption in comprehensive plans, capital improvement programs, and strategic plans, and clear alignment with budget priorities. It also looks like leaders routinely communicating to the public about the transitions under way, the progress against them, and how community members can help support the journey.

- Some ways to gauge high level ownership: Do staffing, partnerships, procurement, budgets, and intergovernmental advocacy support transition intent? Is change management happening as needed, with a clear vision and ongoing communication expressed to the public? Is the work of transitions integrated into core functions and the day-to-day responsibilities of staff necessary for success? How are electeds supporting and leading?

5. Playbook of procedures

Local government commitments are heavily shaped and constrained by procedure, like protocols for what gets a hearing and when, annual or biennial work plans, and comprehensive plans that may come around only every few years or longer. Communications between elected officials and staff may be limited by city ordinance, and communications among elected officials may be very limited by state law. There are also often arcane, highly-localized meeting customs. Getting things done requires working through these procedures and often landing decisions in small windows that are easy to miss.

A playbook for how climate transitions are going to make their way into staff proposals, planning processes,and budgeting is fundamental to turning a good idea into something real. Such a playbook is needed to spell out who does what, when, and through which formal channels, so that key decisions do not depend on heroic one-off efforts. It also helps new staff and elected officials quickly understand how to use existing procedures to advance climate goals, rather than be derailed by them.

- Some questions to ask: What are the relevant scheduled planning processes and upcoming meetings, and who is required to fully elevate the work there and how? What learning systems or listening structures exist, and how are they being used to surface discrepancies and continuously drive improvement?

Conclusion

To scale up climate solutions through local government, we need at least two things. First, political will, which is familiar to most advocates. Looking into 2026 and beyond, climate advocates have great opportunities to continue increasing the proportions of elected local bodies who are led by politicians serious about climate solutions. Everyone has a role to play: run for local office, support local climate candidates, use whatever powers of creativity and persuasion you have–from writing to speaking to organizing and beyond–to help make climate action a core election issue in your community.

The second—and where we need greater shared focus—is to make local governments responsible for specific, strategic commitments to systems change. To do that, help build transition plans that commit to providing great user experiences, an approach to public service delivery that is aligned with those objectives, ownership by city council and the city manager or mayor, and a clear playbook for how strategic climate commitments are going to be adopted and rolled out.

Not everything is going right for the climate movement. But there are some fantastic bright spots, and one of those is big new local government innovations that are starting to unfold.

Looking into 2026, I’m excited to be a part of the movement to help local governments drive the next generation of climate progress. And a big hat tip to FAS with its regulatory rethink and government capacity work as well as ICLEI USA, both partnering with local officials like me to map out how cities can translate ambitious climate goals into durable systems change.

There are great things ahead, and so much room to work together.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Children’s Health and Future Success

Extreme heat poses serious and growing risks to children’s health, safety, and education. Yet, schools and childcare facilities are unprepared to handle rising temperatures. To protect the health and well-being of American children, Congress should (1) set policies that guide childcare facilities and schools in preparing for and responding to extreme heat, (2) collect the data required to inform extreme heat readiness and adaptation, and (3) strategically invest in necessary infrastructure upgrades to build heat resilience.

Children are Uniquely Vulnerable to Extreme Heat Exposure and Acute and Chronic Health Impacts

At least five factors drive children’s vulnerability to negative health outcomes from extreme heat, like heat-related illnesses and chronic complications. First, children’s bodies take a longer time to increase sweat production and acclimatize to higher temperatures. Second, young children are more prone to dehydration than adults because a larger percentage of their body weight is water. Third, infants and young children have challenges regulating their body temperatures and often do not recognize when they should act to cool down. Fourth, compared with adults, children spend more time active outdoors, which results in increased exposure to high ambient heat. Fifth, children usually depend on others to provide them with water and protect them from unsafe outdoor environments, but children’s caretakers often underestimate the seriousness of the symptoms of heat stress. Research shows that extreme heat days are linked to increased emergency room (ER) visits for children, especially the 16% of children living at or below the federal poverty line. Extreme heat also exacerbates children’s chronic diseases, like asthma and eczema, increasing health care costs and decreasing children’s overall quality of life.

The Consequences of Chronic Extreme Heat Exposure on Children’s Learning and Well-Being

Studies show that excess temperatures reduce cognitive functioning. Hot weather also impacts children’s behavior, making them more prone to restlessness, irritability, aggression, and mental distress. Finally, nighttime extreme heat exposure can disrupt sleep patterns, making it harder to fall asleep and stay asleep. These factors can all reduce children’s ability to focus, learn and succeed in school. For each 1°F rise in average annual temperature in school districts without air conditioning or proper heat protections, there is a 1% drop in learning. The Environmental Protection Agency found that these learning losses could translate into nearly $7 billion dollars in annual future income losses if warming trends continue.

Extreme Heat’s Threat to Schools and Childcare Facilities

Rising temperatures force school districts and childcare facilities into a dilemma: choosing between staying open in unsafe heat or closing and disrupting learning and care.

Staying open can expose students and young children to extreme indoor and outdoor temperatures. The Government Accountability Office found that 41% of U.S. schools need to upgrade their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems: upgrades that will cost billions of dollars that schools in low-income areas do not have. Similar infrastructure challenges extend to childcare facilities. Extreme heat also makes outdoor recess more dangerous, as unshaded playgrounds and asphalt surfaces can heat up far above ambient temperatures and pose burn risks.

Yet when schools close for heat, children still suffer. Even five days of closures for inclement weather in a school year can cause measurable learning loss. Additionally, students may lose access to school meals; while food service continuation plans exist, overheated facilities can complicate implementation. Many children, especially in low-income families, also don’t have access to reliable cooling at home, meaning that when schools close for heat, these children receive little respite. Finally, parents are directly impacted as well: school closures also mean parents lose access to childcare, forcing many to miss work or pay for alternative arrangements, straining vulnerable households.

Advancing Solutions that Safeguard American Children from the Impacts of Extreme Heat

To support the capacity of child-serving facilities to adapt to extreme heat, Congress should direct the Department of Education to develop extreme heat guidance, technical assistance programs, and temperature standards, following existing state-level policies as a model for action. Congress should also direct the Administration for Children and Families to develop analogous policies for early childhood facilities and daycare centers receiving federal funding. Finally, Congress should direct the U.S. Department of Agriculture to develop a waiver process for continuing school food service when extreme heat disrupts schedules during the school year.

To support improved federal data collection efforts on extreme heat’s impacts, Congress should direct the Department of Education and Administration for Children and Families to collect data on how schools and childcare facilities are experiencing and responding to extreme heat. There should be a particular focus on the infrastructure upgrades that these facilities need to make to be more prepared for extreme temperatures — especially in low-income and rural communities.Lastly, to foster much-needed infrastructure improvements in schools and childcare facilities, Congress should consider amending Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act or directing the Department of Education to clarify that funds for Title I schools may be used for school infrastructure upgrades needed to avoid learning losses. These upgrades can include the replacement of HVAC systems or installation of cool roofs, walls, and pavement, solar and other shade canopies, and green roofs, trees, and other green infrastructure, which can keep school buildings at safe temperatures during heat waves. Congress should also direct the Administration for Children and Families to identify funding resources that can be used to upgrade federally-supported childcare facilities.

Safeguarding Agricultural Research and Development Capacity

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) experienced a dramatic reduction in staff capacity in the first few months of the second Trump administration. More than 15,000 employees departed the agency through a combination of firings of probationary staff and two rounds of a deferred resignation program, shrinking USDA’s total workforce by 15%.

The administration’s government downsizing campaign is just getting started. Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins recently unveiled a reorganization plan aimed at moving key agency functions outside of the National Capital Region. While the plan does not include new reduction in force targets, further staff attrition is expected as positions are relocated.

The agency’s reorganization plan is not just an organizational change in the name of shrinking the administrative state or reducing bureaucracy. The reorganization, replete with planned office closures and an explicit shrinking of agricultural research capacity, is poised to reshape the American food system, a driver of public health, environment, and economic outcomes across the country.

Why Agricultural R&D is a Crucial Investment

The federal government has historically played a significant role in improving the productivity of U.S. agriculture. By boosting yields and output, public agricultural research and development (R&D) has in turn reduced food prices, enhanced food security, and enabled farmers to produce more with less land and other inputs. Today, with farmers facing high input costs relative to returns, growing pest and disease pressures, and a rapidly shifting trade landscape, new innovations are needed to help producers face challenges.

Every dollar invested in public agricultural R&D has generated $20 in returns—a huge historic return on USDA’s already small research budget. This is especially true relative to other industries. The Department of Energy spends roughly 7 times more on R&D than the Department of Agriculture. When it comes to climate-focused funding in particular, the federal government spent 22 times more on clean energy innovation than R&D agencies spent on climate mitigation in agriculture.

Continued agricultural R&D investments are expected to generate significant economic returns on investments and contribute to improved climate resilience, food security, and regional and rural economic development outcomes. For example, doubling public agricultural R&D funding over the next decade would increase U.S. productivity by about 60% compared to a business-as-usual scenario, while also expanding crop and livestock output more than 40%, reducing prices by more than a third, and substantially cutting greenhouse gas emissions, particularly from avoided deforestation.

Despite the value for farmers and consumers alike, public investment in U.S. agricultural research from USDA, other federal agencies, and states declined significantly from $7.64 billion in 2002 to $5.16 billion in 2019—a nearly 30% reduction, adjusting for inflation. This decline is the leading contributor to a slowdown in agricultural productivity growth. The 2024 Global Agricultural Productivity Report found that U.S. agriculture has not been growing more productive, while India, for example, has a robust annual productivity growth rate of 1.7 percent.

Instead of doubling down to strengthen the nation’s agricultural research capacity and reverse this trend, the administration’s reorganization plan bets on consolidation as a path to efficiency.

Region-Specific Research is at Stake

Preceding USDA’s reorganization announcement, the Office of Management and Budget sent a memo advising all federal agencies to develop plans for programmatic reorganization and significant reductions in force. The memo emphasized several key principles to guide a government-wide reduction in force, including a reduced real property footprint. It is therefore no surprise that several branches of USDA that have vast networks of local and regional offices spanning the nation, including the Agricultural Research Service and Forest Service, would come under scrutiny.

The Agricultural Research Service (ARS) is USDA’s in-house research agency. At the start of 2025, there were 95 ARS laboratories and research units across 42 states employing 8,000 scientists and support staff. This vast network includes soil scientists improving crop water productivity in Texas, experts leading dairy forage systems research in Wisconsin, and plant breeders developing improved protein content in soybeans in North Carolina. On the surface, the real estate footprint of ARS could look inefficient. But, this interpretation fails to recognize the importance of region-specific research and the ability of researchers to deliver farmer-focused, regionally-relevant breakthroughs, exactly the type of service to USDA’s customers the Secretary claims as a goal in the reorganization plan.

The administration justified the overhaul by citing the need to locate agency functions closer to USDA customers. However, more than 90% of USDA’s employees already work outside the National Capital Region, including all but one ARS site. The ARS site slated for closure in the reorganization plan is located in Beltsville, Maryland, outside of Washington, DC.

Appearing before the Senate Agriculture Committee, Deputy Secretary of Agriculture Stephen Vaden assured Senators that only four research centers would be affected by USDA’s reorganization in addition to the closure of the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center.

USDA has yet to announce which four ARS sites will be affected and whether the research done at the ARS location in Beltsville will be relocated and continued, or cancelled entirely.

USDA’s reorganization comes as the agency implements a broader funding freeze on competitive research grants, further threatening the non-federal agricultural scientific research workforce. The administration’s decision to conduct an extended program-by-program review that significantly delayed research grant cycles impacts agricultural research programs at land grant universities across the country. ARS sites are often co-located with public Land Grant institutions, with both benefiting from shared resources and often partnering on research efforts. These delays and ongoing uncertainty threaten the economic returns that publicly funded research has consistently generated for both farmers and consumers.

Consolidation is Not Always a Solution for Efficiency

The Trump administration has often cited consolidation as a path to efficiency. But history shows that USDA reorganizations have weakened, not strengthened, the agency’s capacity. From the Obama administration’s 2012 “Blueprint for Better Services” to the 2019 Trump administration relocation of USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS) and National Institute for Food and Agriculture (NIFA), past efforts framed as efficiency measures instead led to staff attrition, loss of institutional knowledge, and setbacks in core research and grantmaking functions. The reorganization now under consideration risks repeating those mistakes at a far greater scale.

For example, the 2019 relocation of ERS and NIFA to Kansas City led to significant staff attrition and a loss of institutional knowledge. This worsened productivity at all levels, a performance hit that took years to bounce back. In fact, it took USDA more than two years to recover from mass staff attrition and the agency is still facing challenges from the decision to relocate two of its major research facilities from Washington, DC. Two years after relocating, ERS and NIFA’s workforce size and productivity declined significantly. Many of the positions that were lost or left vacant were central to the agency’s functions. As a direct result, the relocation reduced the number of ERS reports and NIFA took longer to process scientific research grants. The Government Accountability Office found that USDA did not account for the cost of staff attrition that results from moving federal facilities and did not follow best practices for effective agency reforms and strategic human capital management. The 2019 relocation effort minimally involved USDA employees, Congress, and other key stakeholders. In addition, both agencies did not follow best practices related to strategic workforce planning, training, and development, which may have contributed to the time it took to recover to baseline staffing levels.

We’re seeing a similar scenario replay in real time with the reorganization plan that was announced in July, but at a much broader scale that can have severe impacts to U.S. agriculture. So far, USDA has not released a detailed reorganization plan or provided any economic or workforce analysis to evaluate how relocation and consolidation would affect its mission or the communities it serves. USDA’s decision to shutter the Beltsville Agricultural Research Center, its flagship research site near Washington, D.C., has drawn criticism from Congress, farm groups, and scientists alike. The agency conceded it had no supporting analysis for the closure, even as the decision threatens to upend vital research programs and dismantle longstanding collaborations.

Unlike the Obama administration’s 2012 proposal to end a dozen ARS programs, which was a direct response to a significant 12% reduction in discretionary funding from Congress, the current reorganization proposal has been announced during a period of strong bipartisan support for agricultural research. Thanks to this support, USDA’s R&D funding has recently rebounded, with funding for ARS and other research agencies surpassing $3.6 billion in 2024, just shy of the funding levels in the early- and mid-2000s. The administration’s reorganization plan threatens to stall or reverse this progress, jeopardizing whether the agency will be able to administer research funding allocated by Congress. Willingness to push forward a reorganization with little regard for legal or procedural constraints or Congressional oversight will cause staff and mission capacity to bear the brunt of the fallout.

Policy Implications

Loss of Institutional Knowledge and Capacity

USDA has begun to grapple with the implications of an unprecedented loss of experienced personnel. This mass exodus spans critical agencies from the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and Farm Service Agency to research divisions like ARS, NIFA, and ERS. These losses undermine food safety, rural development, and science-based policymaking. Pressures on staff to take deferred resignation offers earlier this year culled some of the most seasoned and deeply knowledgeable staff. In a letter to Congress, union groups representing USDA employees outlined that “despite the importance of ARS research, 98 out of 167 food safety scientists have recently resigned”, leaving the future of food security research for all Americans at risk.

Reducing staff capacity also risks the agency’s ability to administer its slate of competitive grant programs that fund critical research. Even if Congress continues to fund research programs at existing discretionary spending levels, research funding will backslide if USDA lacks adequate staff to review applications and get funding out the door each year. Such delays could lead to rescission requests for unspent funds despite existing NIFA programs being regularly oversubscribed with applications from scientists at land-grant universities and other research institutions. The loss of experienced staff not only jeopardizes the continuity of ongoing agricultural R&D, but it also hobbles USDA’s capacity to pivot swiftly in crises like disease outbreaks, market shocks, or climate emergencies. Replacing this intellectual capital will be difficult, costly, and time-consuming, with long-lasting ramifications for program effectiveness, policy depth, and trust in USDA’s scientific and operational integrity.

Decline of U.S. Agricultural R&D Capacity

Sweeping freezes and cancellations of USDA research grants are dealing a severe blow to the non-federal agricultural R&D community, with entire programs suddenly paused or eliminated. The National Sustainable Agricultural Coalition estimates that across all programs, $6B of USDA grants have been frozen or terminated. These disruptions to extramural competitive research are compounded by the ongoing exodus of USDA’s most experienced in-house research staff, threatening to set back U.S. agricultural science for years. China already invests more heavily in agricultural R&D than the U.S., and these setbacks further erode America’s ability to compete on food security, climate resilience, and rural innovation. Unlike other scientific fields, agricultural research has direct and immediate end users. Farmers depend on improved cultivars, conservation practices, access to cheap energy, and pest management tools. When R&D pipelines stall, the consequences eventually ripple into the fields, orchards, and markets that sustain rural economies and national resilience. Agricultural research can have long lag times, making it even more dangerous to abandon investments in agricultural innovation today that will leave U.S. producers empty handed and less competitive in the years ahead.

Erosion of Trust and Stability in Rural Communities

Beyond the immediate impacts on research institutions, the sudden freezing and cancellation of USDA programs destabilize the very communities those programs are designed to serve. Farmers, rural co-ops, and community organizations build their planting, labor, and investment decisions around multi-year USDA commitments. When those commitments are abruptly halted, producers face stranded costs, disrupted harvest cycles, and foregone markets. Community-based organizations and local governments lose confidence in USDA as a reliable partner, undermining adoption of conservation practices, renewable energy, and local food initiatives. This breakdown in trust makes it harder to recruit farmers into new R&D pilots or climate-smart initiatives in the future, even if funding is later restored. The long-term result is a weakened feedback loop between federally funded science and its most critical end-users. This could lower the utility and on-farm adoption of tools, technologies and practices informed by future research. This weakens the economic return on taxpayer dollars dedicated to research projects. At worst, this broken feedback loop leaves rural economies more vulnerable to economic shocks.

Policy Recommendations

Congress holds the ultimate authority over federal appropriations and agency oversight, and thus has significant leverage to shape the future of USDA’s reorganization. How lawmakers exercise that authority will determine whether this reorganization strengthens or undermines the nation’s agricultural research and rural service infrastructure. Through targeted oversight, Congress can insist on transparency, protect against unlawful impoundments or relocations, and ensure continuity so that farmers and rural communities continue to benefit from the innovations generated by USDA’s research agencies. Options available to Congress include:

- Directing the USDA Office of Inspector General to assess USDA’s budget and legal authority for reorganization and relocation, ensuring taxpayer dollars are used lawfully and effectively.

- Requiring USDA to conduct an economic and workforce impact analysis with direct engagement of USDA staff to measure how reorganization affects agricultural research, rural economies, and service delivery.

- Calling for USDA to provide transparent justification for its decision to consolidate into five hubs, including criteria, alternatives considered, and implications for farmer access to research, extension services, and technical assistance.

- Requesting details on how USDA plans to retain staff expertise and capacity to operate existing grant programs at their current size, in accordance with funding appropriated by Congress, ensuring the continuity of vital agricultural research and services.

The proposed consolidation and reorganization of USDA illustrate both the risks and the possibilities ahead. Without careful oversight, these moves could erode research capacity, diminish workforce expertise, and disrupt vital services for farmers and rural communities. Yet we also know there are champions inside and outside government, across party lines, who recognize the value of agricultural R&D and its central role in national food security. With their leadership, there remains a pathway to repair what is broken, ensure transparency and accountability in reorganization efforts, and ultimately build an agricultural R&D infrastructure that delivers lasting benefits for all.

Beyond Binary Debates: How an “Abundance” Framing Can Restore Public Trust and Guide Climate Solutions

Public trust in U.S. government has ebbed and flowed over the decades, but it’s been stuck in the basement for a while. Not since 2005 have more than a third of Americans trusted the institution that underpins so much of American life.

We shouldn’t be surprised. Along with much progress, over the past two decades the U.S. became more unequal, saw stagnation or decline in many rural counties, stumbled into a housing crisis, and experienced worsening health outcomes. When the government can’t deliver (especially in core areas like health, housing, and economic vitality), trust in it wanes while the false promises of autocrats grow more appealing.

The strength of American democracy, in other words, hinges in large part on how well our government functions. This urgency helps explain why, at a moment when the United States is flirting with autocracy ever more vigorously, a book on precisely this topic became a #1 bestseller and prompted a debate around the “abundance agenda” that has turned quasi-existential for many in the policy world.

The abundance agenda, as described by Jonathan Chait, is “a collection of policy reforms designed to make it easier to build housing and infrastructure and for government bureaucracy to work”, such as by streamlining regulations that constrain infrastructure buildout while scaling up major government programs and investments that can deliver public goods.

Unfortunately, popular discourse often flattens the conversation around abundance into a polarized binary around whether or not regulations are good. That frame is overly reductionist. Of course badly designed or out-dated regulatory approaches can block progress or (as in the case of the housing policies that the book Abundance centers on) dry up the supply of public goods. But a theory of the whole regulatory world can’t be neatly extrapolated from urban zoning errors. In an era of accelerating corporate capture, both private and public power structures act to block change and capture profits and power. We need a savvier understanding of what happens at the intersections between the government and the economy, and of how policy translates to communities at local scales.

We should therefore regard “abundance” less as a prescriptive policy agenda than as a frame from which to ask and answer questions at the heart of rebuilding public trust in government. Questions like: “Why is it so hard to build?” “Why are bureaucratic processes so badly matched to societal challenges?” “Why, for heaven’s sake, does nothing work?”

These questions can push us in a direction distinct from the usual big vs. small government debates, or squabbles about the welfare state versus the market. Instead, they may help us ask about interactions within and between government and the economy – the network of relationships, complex causation, and historical choices – that often seem to have left us with a government that feels ill-suited to its times.

At the Federation of American Scientists (FAS), we, along with colleagues in the broader government capacity movement, are exploring these questions, with a particular focus on agendas for renewal and advancing a new paradigm of regulatory ingenuity. One emerging insight is that at its core, abundance is largely about the dynamics of incumbency, that is, about the persistence of broken systems and legacy power structures even as society evolves. A second, related, insight is that the debate around abundance isn’t really about de-regulation or the regulatory state (every government has regulations), but rather about how multi-pronged and polycentric strategies can break through the inertia of incumbent systems, enabling government to better deliver the goods, services, and functions it is tasked with while also driving big and necessary societal changes. And a third is that the abundance discourse must center distributive justice in order to deliver shared prosperity and restore public trust.

Moving the Boulder: Inertia, Climate Change, and the Mission State

The above insights are particularly helpful in guiding new and more durable solutions to climate change – a challenge that touches every aspect of our society, that involves complex questions of market and government design, and that is rooted in the challenges of changing incumbent systems.

Consider the following. It’s now been almost 16 years since the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued its 2009 finding that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are a public danger and began trying to regulate them. To simplify a complex history, what happened on the regulatory front was this: the Obama administration tried to push regulations forward, the Trump administration worked to undo them, and then the cycle repeated through Biden and Trump II, culminating in the EPA’s recent move to revoke the endangerment finding.

We can certainly see the power of incumbency and inertia within this history. Over a decade and a half, the EPA regulated greenhouse gases from new power plants (though never very stringently), new cars and trucks (quite effectively cutting pollution, though never with mandates to actually electrify the fleet), and…that’s about it. The agency never implemented standards for the existing power plants and existing vehicles that emit the lion’s share of U.S. GHGs. It never regulated GHGs from industry or buildings. And thanks to the efforts of entrenched fossil-fuel actors and their political allies, the climate regulations EPA managed to get over the finish line were largely rolled back.

None of this should be read as a knock on the dedicated civil servants at EPA and partner federal agencies who worked to produce GHG regulations that were scientifically grounded, legally defensible, technically feasible, and cost effective, even while grappling with the monumental challenges of outdated statutes and internal systems. But it certainly speaks to the challenge of securing lasting change.

The work of economist Mariana Mazzucato offers clues to how we might tackle this challenge; she paints a portrait of a “mission state” that integrates all of government’s levers to define and execute a particular objective, such as an effective, equitable, and durable clean energy transition. This theory isn’t a case for simplistic deregulation, nor is it a claim that regulations somehow “don’t work”. Rather, it suggests that (especially in a post-Chevron world) another round of battles over EPA authority won’t ultimately get us where we need to go on climate, nor will it help us productively reshape our institutions in ways that engender public trust.

The shift from one energy system foundation to another is messy – and it is inherently about power. As giant investment firms hustle to buy public utilities, enormous truck companies side with the Trump administration to dismantle state clean freight programs, and subsidies for clean energy are decried as unfair and market-distorting even though subsidies for fossil energy have persisted for nearly a century, it’s clear that corporate incumbents can capture public investments or capture government power to throttle change. Delivering change means thinking through the many ways incumbency creates systems of dependencies throughout society, and what options – from regulations to monetary policy to the ability to shape the rule of law – we have to respond. To disrupt energy incumbents and achieve energy abundance, in other words, we must couple regulatory and non-regulatory tools.

After all, the past 16 years haven’t just been a story of regulatory back-and-forth. They are also a story of how U.S. emissions have fallen relatively steadily in part due to federal policies, in part to state and local leadership, and in part to ongoing technological progress. Emissions will likely keep falling (though not fast enough) despite Trump-era rollbacks. That’s evidence that there’s not a one-to-one connection between regulatory policy and results.

We also have evidence of how potent it can be when economic and regulatory efforts pull in tandem. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was the first time the United States strongly invested in an economic pivot towards clean energy at scale and in a mission-oriented way. The results were immediate and transformative: U.S. clean energy and manufacturing investments took off in ways that far surpassed most expectations. And while the IRA has certainly come under attack during this Administration, it is nevertheless striking that today’s Republican trifecta retained large parts of the entirely Democratically-passed IRA, demonstrating the sticking power of a mission-oriented approach.

Conducting the Orchestra: The Need for an Expanded Playing Field

Thinking beyond regulatory levers (i.e., a multi-pronged approach) is necessary but not sufficient to chart the path forward for climate strategy. In a highly diverse and federalist nation like the United States, we must also think beyond federal government entirely.

That’s because, as Nobel-winning economist Dr. Elinor Ostrom put it, climate change is inherently a “polycentric” problem. The incumbent fossil systems at the root of the climate crisis are entrenched and cut across geographies as well as across public/private divisions. Therefore the federal government cannot effectively disrupt these systems alone. Many components of the fundamental economic and societal shifts that we need to realize the vision of clean energy abundance lie substantially outside sole federal control – and are best driven by the sustained investments and clear and consistent policies that our polarized politics aren’t delivering.

For example, states, counties, and cities have long had primary oversight of their own economic development plans, their transportation plans, their building and zoning policies, and the make-up of their power mix. That means they have primary power both over most sources of climate pollution (two-thirds of the world’s climate emissions come from cities) and over how their economies and built environments change in response. These powers are fundamentally different from, and generally much broader than, powers held by federal regulatory agencies. Subnational governments also often have a greater ability to move funds, shape new complex policies across silos, and come up with creative responses that are inherently place-based. (The indispensable functions of subnational governments are also a reason why decades of cuts to subnational government budgets are a worryingly overlooked problem – austerity inhibits bottom-up climate progress.)

The private sector has similar ability to either constrain or drive forward new economic pathways. Indeed, with the private sector accounting for about half of funding for climate solutions, it is impossible to imagine a successful clean-energy transition that isn’t heavily predicated on private capabilities – particularly in the United States. While China’s clean-tech boom is largely the product of massive top-down subsidies and market interventions, a non-communist regime must rely on the private sector as a core partner rather than a mere executor of climate strategy. Fortunately, avenues for effectively engaging and leveraging the private sector in climate action are rapidly developing, including partnering public enterprise with private equity to sustain clean energy policies despite federal cutbacks.

An orchestra is an apt analogy. Just as many instruments and players come together in a symphony, so too can private and public actors across sectors and governance levels come together to achieve clean energy abundance. This analogy extends Mazzucato’s conception of a mission state into a “mission society”, envisioning a network that spans from cities to nation states, from private firms to civil actors, working in concert to overcome what Ben Rhodes calls a “crisis of short termism” and deliver a “coherent vision” of a better future.

Building Towards Shared Prosperity

For the vision to be coherent, it must resonate across socioeconomic and ideological boundaries, and it must recognize that the structures of racial, class, and gender disparity that have marked the American project from the beginning are emphatically still there. Such factors shape available pathways for progress and affect their justice and durability. For instance: electric vehicle adoption can only grow so quickly until we make it much easier for those living in rented or multifamily housing to charge. Cheaper renewables only mean so much when prevailing policies limit the financial benefits that are passed on to lower-income Americans.

To borrow, and complicate, a metaphor from Abundance: distributive justice questions are fundamentally not “everything bagel” seasonings to be disregarded as secondary to delivery goals. They are meaningful constraints on delivery as well as critical potentialities for better systems, and are hence central to policy and politics. No mission state or mission nation, addressing the polycentric landscape of networked change needed to shift big incumbent systems, can afford to dismiss or ignore them. Displacing those systems requires wrestling with inequality and striving to create shared prosperity through new approaches that are distributively fair.

That’s an approach rooted in orchestration, one that asks why some instruments drown out others, and how to alter relationships between players to produce better results. It understands that we can’t solve scarcity without centering distributive justice, because as long as deep structural disparities and structural power exist there is strong potential for the benefits of rapid energy or housing buildout to be channeled towards those who need them least. And it is capable of restabilizing the center of American society and restoring trust in U.S. government because it realistically grapples with the interests of incumbents while paying more than lip service to the interests of a dazzlingly diverse American public.

This re-fashioned abundance agenda can provide actual principles for administrative state reform because it knows what it is asking regulators, and the larger intersecting layers of government and civil society, to do: Systematically remove points of inertia to accelerate shared prosperity in a safe climate, while anticipating and solving for distributive risks of change.

Because again, the abundance debate isn’t really about whether or not regulations are good. It’s about unfreezing our politics by being clear and courageous about our goals for a society that works better and is capable of big things.

This is not the first time Americans have envisioned a better future in the midst of national crisis, or the first time we have collectively disrupted failed incumbent systems. From our messy foundation, to the beginnings of Reconstruction during the Civil War, to the architects of the New Deal envisioning an active and effective government in the midst of the Dust Bowl and Depression, the history of our nation is full of evidence that a compelling vision of truly democratic government can pull Americans back together despite deep and real problems. Each time, these debates have scrambled existing binaries, and driven realignment. We are on the verge of realignment again as the systems built up over the fossil era break down and our neoliberal order fragments. This is the right time to engage, together, in orchestrating what comes next.

Too Hot not to Handle

Every region in the U.S. is experiencing year after year of record-breaking heat. More households now require home cooling solutions to maintain safe and liveable indoor temperatures. Over the last two decades, U.S. consumers and the private sector have leaned heavily into purchasing and marketing conventional air conditioning (AC) systems, such as central air conditioning, window units and portable ACs, to cool down overheating homes.

While AC can offer immediate relief, the rapid scaling of AC has created dangerous vulnerabilities: rising energy bills are straining people’s wallets and increasing utility debt, while surging electricity demand increases reliance on high-polluting power infrastructure and mounts pressure on an aging power grid increasingly prone to blackouts. There is also an increasing risk of elevated demand for electricity during a heat wave, overloading the grid and triggering prolonged blackouts, causing whole regions to lose their sole cooling strategy. This disruption could escalate into a public health emergency as homes and people overheat, leading to hundreds of deaths.

What Americans need to be prepared for more extreme temperatures is a resilient cooling strategy. Resilient cooling is an approach that works across three interdependent systems — buildings, communities, and the electric grid — to affordably maintain safe indoor temperatures during extreme heat events and reduce power outage risks.

This toolkit introduces a set of Policy Principles for Resilient Cooling and outlines a set of actionable policy options and levers for state and local governments to foster broader access to resilient cooling technologies and strategies.

This toolkit introduces a set of Policy Principles for Resilient Cooling and outlines a set of actionable policy options and levers for state and local governments to foster broader access to resilient cooling technologies and strategies. For example, states are the primary regulators of public utility commissions, architects of energy and building codes, and distributors of federal and state taxpayer dollars. Local governments are responsible for implementing building standards and zoning codes, enforcing housing and health codes, and operating public housing and retrofit programs that directly shape access to cooling.

The Policy Principles for Resilient Cooling for a robust resilient cooling strategy are:

- Expand Cooling Access and Affordability. Ensuring that everyone can affordably access cooling will reduce the population-wide risk of heat-related illness and death in communities and the resulting strain on healthcare systems. Targeted financial support tools — such as subsidies, rebates, and incentives — can reduce both upfront and ongoing costs of cooling technologies, thereby lowering barriers and enabling broader adoption.

- Incorporate Public Health Outcomes as a Driver of Resilience. Indoor heat exposure and heat-driven factors that reduce indoor air quality — such as pollutant accumulation and mold-promoting humidity — are health risks. Policymakers should embed heat-related health risks into building codes, energy standards, and guidelines for energy system planning, including establishing minimum indoor temperature and air quality requirements, integrating health considerations into energy system planning standards, and investing in multi-solving community system interventions like green infrastructure.

- Advance Sustainability Across the Cooling Lifecycle. Rising demand for air conditioning is intensifying the problem it aims to solve by increasing electricity consumption, prolonging reliance on high-polluting power plants, and leaking refrigerants that release powerful greenhouse gases. Policymakers can adopt codes and standards that reduce reliance on high-emission energy sources and promote low-global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants and passive cooling strategies.

- Promote Solutions for Grid Resilience. The U.S. electric grid is struggling to keep up with rising demand for electricity, creating potential risks to communities’ cooling systems. Policymakers can proactively identify potential vulnerabilities in energy systems’ ability to sustain safe indoor temperatures. Demand-side management strategies, distributed energy resources, and grid-enhancing technologies can prepare the electric grid for increased energy demand and ensure its reliability during extreme heat events.

- Build a Skilled Workforce for Resilient Cooling. Resilient cooling provides an opportunity to create pathways to good-paying jobs, reduce critical workforce gaps, and bolster the broader economy. Investing in a workforce that can design, install, and maintain resilient cooling systems can strengthen local economies, ensure preparedness for all kinds of risks to the system, and bolster American innovation.

By adopting a resilient cooling strategy, state and local policymakers can address today’s overlapping energy, health, and affordability crises, advance American-made innovation, and ensure their communities are prepared for the hotter decades ahead.

Position on the Cool Corridors Act of 2025

The Federation of American Scientists supports H.R. 4420, the Cool Corridors Act of 2025, which would reauthorize the Healthy Streets program through 2030 and seeks to increase green and other shade infrastructure in high-heat areas.

Science has shown that increasing sources of shade, including tree canopy and other shade infrastructure, can cool surrounding areas as much as 10 degrees, protecting people and critical infrastructure. The Cool Corridors Act of 2025 would create a unique and reliable funding source for communities to build out their shade infrastructure.

“Extreme heat is a serious threat to public health and critical infrastructure,” says Grace Wickerson, Senior Manager for Climate and Health at the Federation of American Scientists. “Increasing tree canopies and shade infrastructure is a key recommendation in FAS’ 2025 Heat Policy Agenda and we commend Reps Lawler and Strickland for taking action on this.”

Maintaining American Leadership through Early-Stage Research in Methane Removal

Methane is a potent gas with increasingly alarming effects on the climate, human health, agriculture, and the economy. Rapidly rising concentrations of atmospheric methane have contributed about a third of the global warming we’re experiencing today. Methane emissions also contribute to the formation of ground-level ozone, which causes an estimated 1 million premature deaths around the world annually and poses a significant threat to staple crops like wheat, soybeans, and rice. Overall, methane emissions cost the United States billions of dollars each year.

Most methane mitigation efforts to date have rightly focused on reducing methane emissions. However, the increasingly urgent impacts of methane create an increasingly urgent need to also explore options for methane removal. Methane removal is a new field exploring how methane, once in the atmosphere, could be broken down faster than with existing natural systems alone to help lower peak temperatures, and counteract some of the impact of increasing natural methane emissions. This field is currently in the “earliest stages of knowledge discovery”, meaning that there is a tremendous opportunity for the United States to establish its position as the unrivaled world leader in an emerging critical technology – a top goal of the second Trump Administration. Global interest in methane means that there is a largely untapped market for innovative methane-removal solutions. And investment in this field will also generate spillover knowledge discovery for associated fields, including atmospheric, materials, and biological sciences.

Congress and the Administration must move quickly to capitalize on this opportunity. Following the recommendations of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM)’s October 2024 report, the federal government should incorporate early-stage methane removal research into its energy and earth systems research programs. This can be achieved through a relatively small investment of $50–80 million annually, over an initial 3–5 year phase. This first phase would focus on building foundational knowledge that lays the groundwork for potential future movement into more targeted, tangible applications.

Challenge and Opportunity

Methane represents an important stability, security, and scientific frontier for the United States. We know that this gas is increasing the risk of severe weather, worsening air quality, harming American health, and reducing crop yields. Yet too much about methane remains poorly understood, including the cause(s) of its recent accelerating rise. A deeper understanding of methane could help scientists better address these impacts – including potentially through methane removal.

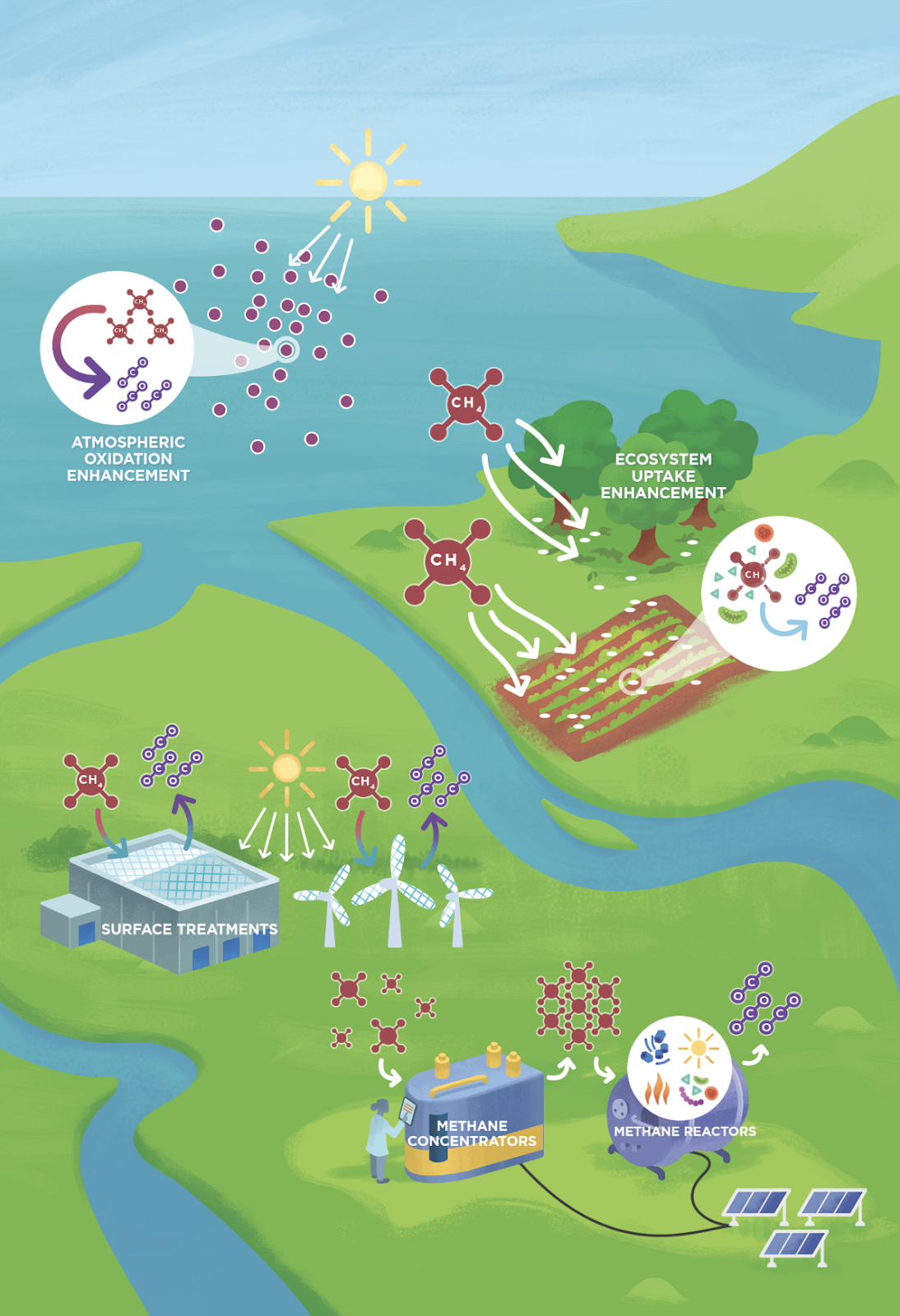

Methane removal is an early-stage research field primed for new American-led breakthroughs and discoveries. To date, four potential methane-removal technologies and one enabling technology have been identified. They are:

- Ecosystem uptake enhancement: Increasing microbes’ consumption of methane in soils and trees or getting plants to do so.

- Surface treatments: Applying special coatings that “eat” methane on panels, rooftops, or other surfaces.

- Atmospheric oxidation enhancement: Increasing atmospheric reactions conducive to methane breakdown.

- Methane reactors: Breaking down methane in closed reactors using catalysts, reactive gases, or microbes.

- Methane concentrators: A potentially enabling technology that would separate or enrich methane from other atmospheric components.

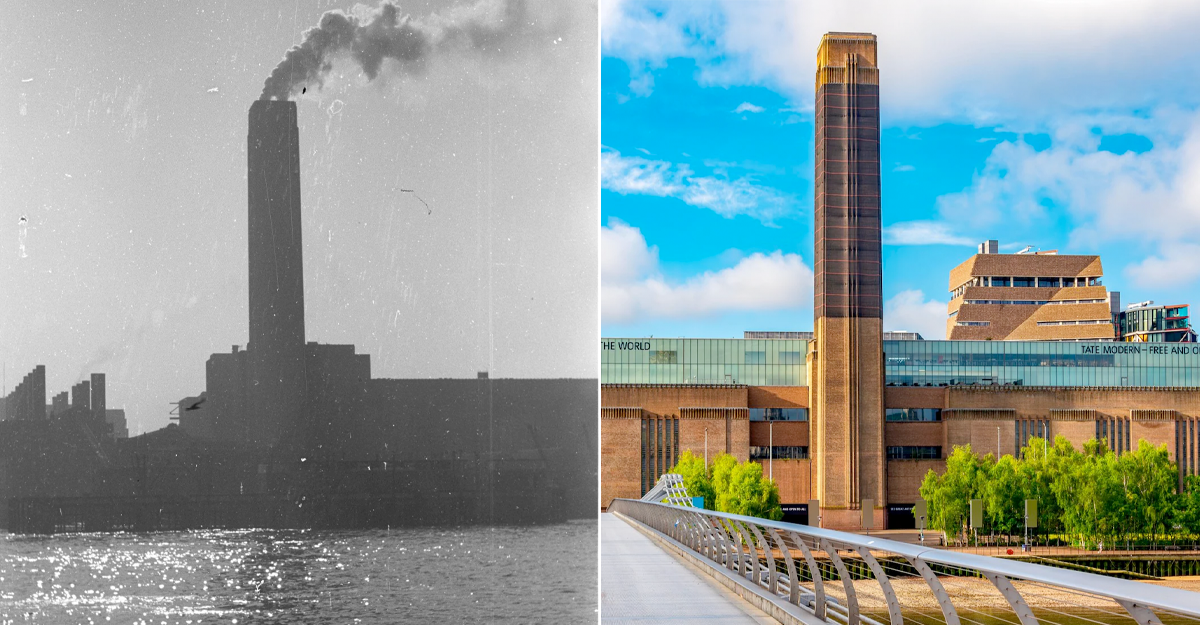

Figure 1. Atmospheric Methane Removal Technologies. (Source: National Academies Research Agenda)

Many of these proposed technologies have analogous traits to existing carbon dioxide removal methods and other interventions. However, much more research is needed to determine the net climate benefit, cost plausibility and social acceptability of all proposed methane removal approaches. The United States has positioned itself to lead on assessing and developing these technologies, such as through NASEM’s 2024 report and language included in the final FY24 appropriations package directing the Department of Energy to produce its own assessment of the field. The United States also has shown leadership with its civil society funding some of the earliest targeted research on methane removal.

But we risk ceding our leadership position – and a valuable opportunity to reap the benefits of being a first-mover on an emergent technology – without continued investment and momentum. Indeed, investing in methane removal research could help to improve our understanding of atmospheric chemistry and thus unlock novel discoveries in air quality improvement and new breakthrough materials for pollution management. Investing in methane removal, in short, would simultaneously improve environmental quality, unlock opportunities for entrepreneurship, and maintain America’s leadership in basic science and innovation. New research would also help the United States avoid possible technological surprises by competitors and other foreign governments, who otherwise could outpace the United States in their understanding of new systems and approaches and leave the country unprepared to assess and respond to deployment of methane removal elsewhere.

Plan of Action

The federal government should launch a five-year Methane Removal Initiative pursuant to the recommendations of the National Academies. A new five-year research initiative will allow the United States to evaluate and potentially develop important new tools and technologies to mitigate security risks arising from the dangerous accumulation of methane in the atmosphere while also helping to maintain U.S. global leadership in innovation. A well-coordinated, broad, cross-cutting federal government effort that fosters collaborations among agencies, research universities, national laboratories, industry, and philanthropy will enable the United States to lead science and technology improvements to meet these goals. To develop any new technologies on timescales most relevant for managing earth system risk, this foundational research should begin this year at an annual level of $50–$80 million per year. Research should last ideally five years and inform a more applied second-phase assessment recommended by the National Academies.

Consistent with the recommendations from the National Academies’ Atmospheric Methane Removal Research Agenda and early philanthropic seed funding for methane removal research, the Methane Removal Initiative would:

- Establish a national methane removal research and development program involving key science agencies, primarily the National Science Foundation, Department of Energy, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, with contributions from other agencies including the US Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Standards and Technology, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Department of Interior, and Environmental Protection Agency.

- Focus early investments in foundational research to advance U.S. interests and close knowledge gaps, specifically in the following areas:

- The “sinks” and sources of methane, including both ground-level and atmospheric sinks as well as human-driven and natural sources (40% of research budget),

- Methane removal technologies, as described below (30% of research budget); and

- Potential applications of methane removal, such as demonstration and deployment systems and their interaction with other climate response strategies (30% of research budget).

The goal of this research program is ultimately to assess the need for and viability of new methods that could break down methane already in the atmosphere faster than natural processes already do alone. This program would be funded through several appropriations subcommittees in Congress, most notably Energy & Water Development and Commerce, Justice, Science and Related Agencies. Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Interior and Environment also have funding recommendations relevant to their subcommittees. As scrutiny grows on the federal government’s fiscal balance, it should be noted that the scale of proposed research funding for methane removal is relatively modest and that no funding has been allocated to this potentially critical area of research to date. Forgoing these investments could result in neglecting this area of innovation at a critical time where there is an opportunity for the United States to demonstrate leadership.

Conclusion

Emissions reductions remain the most cost-effective means of arresting the rise in atmospheric methane, and improvements in methane detection and leak mitigation will also help America increase its production efficiency by reducing losses, lowering costs, and improving global competitiveness. The National Academies confirms that methane removal will not replace mitigation on timescales relevant to limiting peak warming this century, but the world will still likely face “a substantial methane emissions gap between the trajectory of increasing methane emissions (including from anthropogenically amplified natural emissions) and technically available mitigation measures.” This creates a substantial security risk for the United States in the coming decades, especially given large uncertainties around the exact magnitude of heat-trapping emissions from natural systems. A modest annual investment of $50–80 million can pay much larger dividends in future years through new innovative advanced materials, improved atmospheric models, new pollution control methods, and by potentially enhancing security against these natural systems risks. The methane removal field is currently at a bottleneck: ideas for innovative research abound, but they remain resource-limited. The government has the opportunity to eliminate these bottlenecks to unleash prosperity and innovation as it has done for many other fields in the past. The intensifying rise of atmospheric methane presents the United States with a new grand challenge that has a clear path for action.

Methane is a powerful greenhouse gas that plays an outsized role in near-term warming. Natural systems are an important source of this gas, and evidence indicates that these sources may be amplified in a warming world and emit even more. Even if we succeed in reducing anthropogenic emissions of methane, we “cannot ignore the possibility of accelerated methane release from natural systems, such as widespread permafrost thaw or release of methane hydrates from coastal systems in the Arctic.” Methane removal could potentially serve as a partial response to such methane-emitting natural feedback loops and tipping elements to reduce how much these systems further accelerate warming.

No. Aggressive emissions reductions—for all greenhouse gases, including methane—are the highest priority. Methane removal cannot be used in place of methane emissions reduction. It’s incredibly urgent and important that methane emissions be reduced to the greatest extent possible, and that further innovation to develop additional methane abatement approaches is accelerated. These have the important added benefit of improving American energy security and preventing waste.

More research is needed to determine the viability and safety of large-scale methane removal. The current state of knowledge indicates several approaches may have the potential to remove >10 Mt of methane per year (~0.8 Gt CO₂ equivalent over a 20 year period), but the research is too early to verify feasibility, safety, and effectiveness. Methane has certain characteristics that suggest that large-scale and cost-effective removal could be possible, including favorable energy dynamics in turning it into CO2 and the lack of a need for storage.

The volume of methane removal “needed” will depend on our overall emissions trajectory, atmospheric methane levels as influenced by anthropogenic emissions and anthropogenically amplified natural systems feedbacks, and target global temperatures. Some evidence indicates we may have already passed warming thresholds that trigger natural system feedbacks with increasing methane emissions. Depending on the ultimate extent of warming, permafrost methane release and enhanced methane emissions from wetland systems are estimated to potentially lead to ~40-200 Mt/yr of additional methane emissions and a further rise in global average temperatures (Zhang 2023, Kleinen 2021, Walter 2018, Turetsky 2020). Methane removal may prove to be the primary strategy to address these emissions.

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, 43 times stronger than carbon dioxide molecule for molecule, with an atmospheric lifetime of roughly a decade (IPCC, calculation from Table 7.15). Methane removal permanently removes methane from the atmosphere by oxidizing or breaking down methane into carbon dioxide, water, and other byproducts, or if biological processes are used, into new biomass. These products and byproducts will remain cycling through their respective systems, but without the more potent warming impact of methane. The carbon dioxide that remains following oxidation will still cause warming, but this is no different than what happens to the carbon in methane through natural removal processes. Methane removal approaches accelerate this process of turning the more potent greenhouse gas methane into the less potent greenhouse gas carbon dioxide, permanently removing the methane to reduce warming.

The cost of methane removal will depend on the specific potential approach and further innovation, specific costs are not yet known at this stage. Some approaches have easier paths to cost plausibility, while others will require significant increases in catalytic, thermal or air processing efficiency to achieve cost plausibility. More research is needed to determine credible estimates, and innovation has the potential to significantly lower costs.

Greenhouse gases are not interchangeable. Methane removal cannot be used in place of carbon dioxide removal because it cannot address historical carbon dioxide emissions, manage long-term warming or counteract other effects (e.g., ocean acidification) that are results of humanity’s carbon dioxide emissions. Some methane removal approaches have characteristics that suggest that they may be able to get to scale quickly once developed and validated, should deployment be deemed appropriate, which could augment our near-term warming mitigation capacity on top of what carbon dioxide removal and emissions reductions offer.

Methane has a short atmospheric lifetime due to substantial methane sinks. The primary methane sink is atmospheric oxidation, from hydroxyl radicals (~90% of the total sink) and chlorine radicals (0-5% of the total sink). The rest is consumed by methane-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in soils (~5%). While understood at a high level, there is substantial uncertainty in the strength of the sinks and their dynamics.

Up until about 2000, the growth of methane was clearly driven by growing human-caused emissions from fossil fuels, agriculture, and waste. But starting in the mid-2000s, after a brief pause where global emissions were balanced by sinks, the level of methane in the atmosphere started growing again. At the same time, atmospheric measurements detected an isotopic signal that the new growth in methane may be from recent biological—as opposed to older fossil—origin. Multiple hypotheses exist for what the drivers might be, though the answer is almost certainly some combination of these. Hypotheses include changes in global food systems, growth of wetlands emissions as a result of the changing climate, a reduction in the rate of methane breakdown and/or the growth of fracking. Learn more in Spark’s blog post.

Methane has a significant warming effect for the 9-12 years that it remains in the atmosphere. Given how potent methane is, and how much is currently being emitted, even with a short atmospheric lifetime, methane is accumulating in the atmosphere and the overall warming impact of current and recent methane emissions is 0.5°C. Methane removal approaches may someday be able to bring methane-driven warming down faster than with natural sinks alone. The significant risk of ongoing substantial methane sources, such as natural methane emissions from permafrost and wetlands, would lead to further accumulation. Exploring options to remove atmospheric methane is one strategy to better manage this risk.

Research into all methane removal approaches is just beginning, and there is no known timeline for their development or guarantee that they will prove to be viable and safe.

Some methane removal and carbon dioxide removal approaches overlap. Some soil amendments may have an impact on both methane and carbon dioxide removal, and are currently being researched. Catalytic methane-oxidizing processes could be added to direct air capture (DAC) systems for carbon dioxide, but more innovation will be needed to make these systems sufficiently efficient to be feasible. If all planned DAC capacity also removed methane, it would make a meaningful difference, but still fall very short of the scale of methane removal that could be needed to address rising natural methane emissions, and additional approaches should be researched in parallel.