CBS’s 60 Minutes program Risk of Nuclear Attack Rises described that Russia may be lowering the threshold for when it would use nuclear weapons, and showed how U.S. nuclear bombers have started flying missions they haven’t flown since the Cold War: Over the North Pole and deep into Northern Europe to send a warning to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The program follows last week’s program The New Cold War where viewers were shown unprecedented footage from STRATCOM’s command center at Omaha Air Base in Nebraska.

Producer Mary Welch and correspondent David Martin have produced a fascinating and vital piece of investigative journalism showing disturbing new developments in the nuclear relationship between Russia and the United States.

They were generous enough to consult me and include me in the program to discuss the increasing Cold War and dangerous military posturing.

Nuclear Bomber Operations Context

Just a few years ago, U.S. nuclear bombers didn’t spend much time in Europe. They were focused on operations in the Middle East, Western Pacific, and Indian Ocean. Despite several years of souring relations and mounting evidence that the “reset” with Russia had failed or certainly not taken off, NATO couldn’t make itself say in public that Russia gradually was becoming an adversary once again.

Whatever hesitation was left changed in March 2014 when Vladimir Putin sent his troops to invade Ukraine and annexed Crimea. The act followed years of Russian efforts to coerce the Baltic States, growing and increasingly aggressive military operations around European countries, and explicit nuclear threats against NATO countries getting involved in the U.S. ballistic missile defense system.

Granted, NATO may not have been a benign neighbor, with massive expansion eastward of new members all the way up to the Russian border, and a consistent tendency to ignore or dismiss Russian concerns about its security interests.

But whatever else Putin might have thought he would gain from his acts, they have awoken NATO from its detour in Afghanistan and refocused the Alliance on its traditional mission: defense of NATO territory against Russian aggression. As a result, Putin will now get more NATO troops along his western and southern borders, larger and more focused military exercises more frequently in the Baltic Sea and Black Sea, increasing or refocused defense spending in NATO, and a revitalization of a near-slumbering nuclear mission in Europe.

Six years ago the United States was this close to pulling its remaining non-strategic nuclear weapons out of Europe. Only an engrained NATO nuclear bureaucracy aided by the Obama administration’s lack of leadership prevented the withdrawal of the weapons. Russia has complained about them for years but now it seems very unlikely that the modernization of the F-35A with the B61-12 guided bomb can be stopped. The weapons might even get a more explicit role against Russia, although this is still a controversial issue for some NATO members.

But the U.S. military would much prefer to base the nuclear portion of its extended deterrence mission in Europe on strategic bombers rather than the short-range fighter-bombers forward deployed there. The non-strategic nuclear weapons are far too controversial and vulnerable to the myriads of political views in the host countries. Strategic bombers are free of such constraints.

A New STRATCOM-EUCOM Link

Therefore, even before NATO at the Warsaw Summit this summer decided to reinvigorate its commitment to nuclear deterrence, former U.S. European Command (EUCOM) commander General Philip Breedlove told Congress in February 2015, EUCOM had already “forged a link between STRATCOM Bomber Assurance and Deterrence [BAAD] missions to NATO regional exercises” as part of Operation Atlantic Resolve to deter Russia.

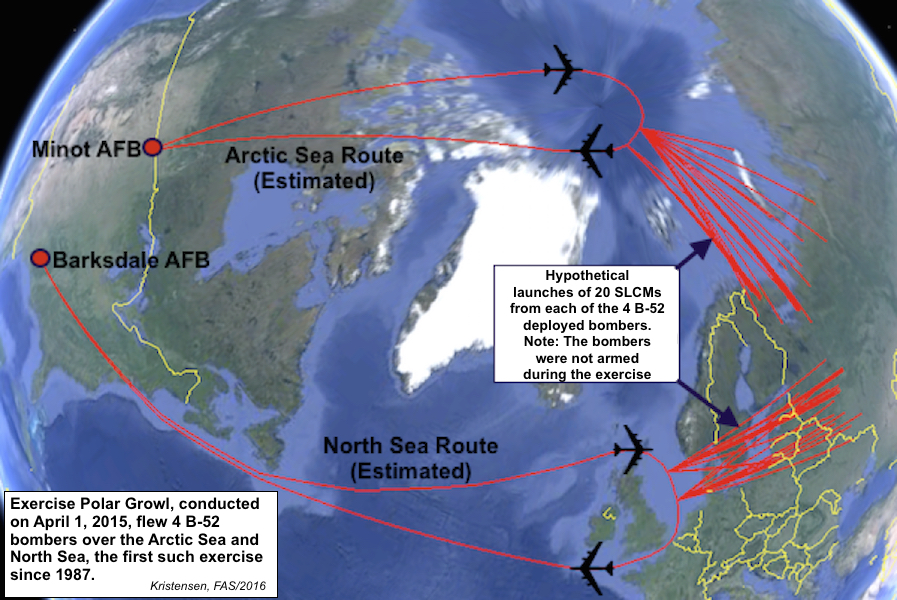

Less than two months later, on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers took of from their bases in the United States and flew across the North Pole and North Sea in a simulated strike exercise against Russia. The bombers proceeded all the way to their potential launch points for air-launched cruise missiles before they returned to the United States. Such an exercise had not been conducted since the late-1980s against the Soviet Union. Combined, the four bombers could have delivered 80 long-range nuclear cruise missiles with a combined explosive power of 800 Hiroshima bombs.

During Exercise Polar Growl on April 1, 2015, four nuclear-capable B-52H bombers flew along two routes into the Arctic and North Sea regions that appeared to simulate long-range strikes against Russia. The four bombers were capable of launching up to 80 nuclear air-launched cruise missiles with a combined explosive power equivalent to 800 Hiroshima bombs. All routes are approximate.

Despite its strategic implications, Polar Growl also had a distinctive regional – even limited – objective because of the crisis in Europe. Planning for such regional deterrence scenarios have taken on a new importance during the past couple of decades and they have become central to current planning because it is in such regional scenarios that the United States believes it is most likely that nuclear weapons could actually be used.

“The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, in 2014 predicted only a few weeks before Russia invaded Ukraine, “and continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.”

Two weeks after the bombers returned from Polar Growl, Robert Scher, the U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities, told Congress: “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts.” This includes “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

Nuclear Conventional Integration

Much of this increased planning involves conventional weapons such as the new long-range conventional JASSM-ER cruise missile, but the planning also involves nuclear. In fact, conventional and nuclear appear to be integrating in a way they have done before. This effort was described recently by Brian McKeon, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy and Acting Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, during the annual STRATCOM Deterrence Symposium:

In the Department of Defense we’re working to effectively integrate conventional and nuclear planning and operations. Integration is not new but we’re renewing our focus on it because of recent developments and how we see potential adversaries preparing for conflict. This is an area where the focus in Omaha has really led the way and I want to commend Admiral Haney and STRATCOM for being able to shift planning so quickly toward this approach and thinking though conflict. No one wants to think about using nuclear weapons and we all know the principle role of nuclear weapons is to deter their use by others. But as we’ve seen, out adversaries may not hold the same view.

Let me be clear that when I say integration I do not mean to say we have lowered the threshold for nuclear use or would turn to nuclear weapons sooner in a conventional campaign. As we stated in the Nuclear Posture Review, the United States will “only consider the use of nuclear weapons in extreme circumstances to defend the vital interests of the United States or its allies and partners.” The NPR also emphasized the importance of reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy, a requirement that has been advanced in our planning consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance, including with non-nuclear strike options.

What I mean by integration is synchronizing our thinking across all domains in a way that maximizes the credibility and flexibility of our deterrent through all phases of conflict and responds appropriately to asymmetrical escalation. For too long, crossing the nuclear threshold was through to move a nuclear conflict out of the conventional dimension and wholly into the nuclear realm. Potential adversaries are exploring ways to cross this threshold with low-yield nuclear weapons to test out resolve, capabilities, and Allied cohesion. We must demonstrate that such a strategy cannot succeed so that it is never attempted. To that end we’re planning and exercising our non-nuclear operations conscious of how they might influence an adversary’s decision to go nuclear.

We also plan for the possibility of ongoing U.S. and Allied operations in a nuclear environment and working to strengthen resiliency of conventional operations to nuclear attack. By making sure our forces are capable of continuing the fight following a limited nuclear use we preserve flexibility for the president. And by explicitly preparing for the implication of an adversary’s limited nuclear use and providing credible options for the President, we strengthen our deterrent and reduce the risk of employment in the first instance.

Regional nuclear scenarios no longer primarily involve planning against what the Bush administration called “rogue states” such as North Korea and Iran, but increasingly focus on near-peer adversaries (China) and peer adversaries (Russia). “We are working as part of the NATO alliance very carefully both on the conventional side as well as meeting as part of the NPG [Nuclear Planning Group] looking at what NATO should be doing in response to the Russian violation of the INF Treaty,” Scher explained.

STRATCOM last updated the strategic nuclear war plan (OPLAN 8010-12) in 2012 and is currently about to publish an updated version that incorporates the changes caused by the Obama administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy from 2013.

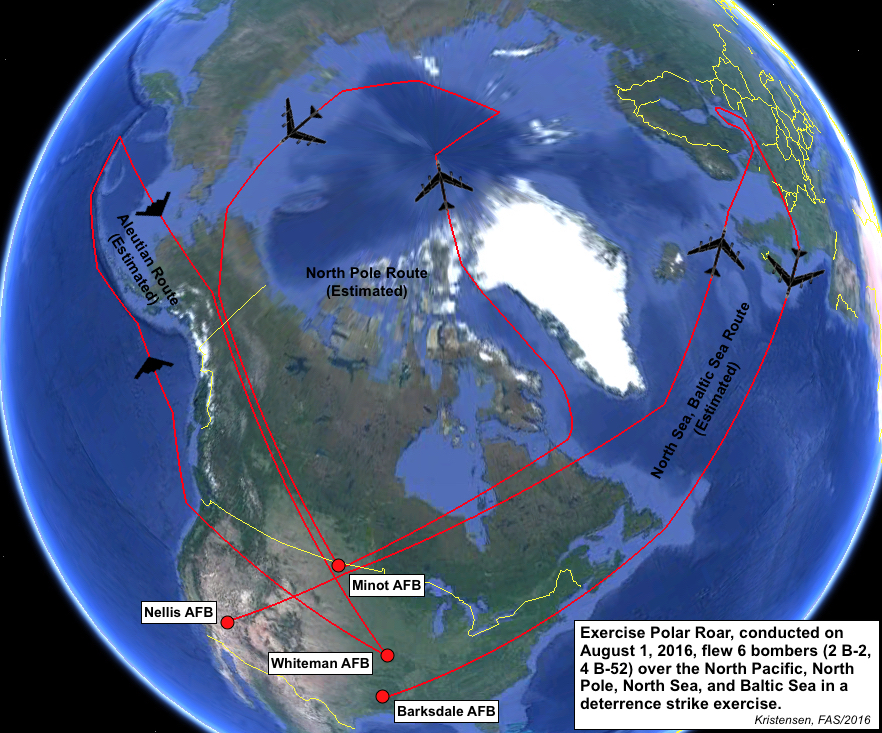

Two months ago, a little over a year after Polar Growl, another bomber strike exercise was launched. This time six bombers (4 B-52s and 2 B-2s) flew closer to Russia and simultaneously over the Arctic Sea, North Sea, Baltic Sea, and North Pacific Ocean. The six Polar Roar sorties required refueling support from 24 KC-135 tankers as well as E4-B Advanced Airborne Command Post and E-6B TACAMO nuclear command and control aircraft.

The routes (see below) were eerily similar to the Chrome Dome airborne alert routes that were flown by nuclear-armed bombers in the 1960s against the Soviet Union.

Exercise Polar Roar on August 1, 2016, followed Exercise Polar Growl from 2015 but involved more bombers, both nuclear-capable and conventional-only, and flew closer to Russia and deep into the Baltic Sea. Polar Roar also included B-2 stealth bombers in the North Pacific. All routes are approximate.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.