Indian Test-Launch of MIRV Missile Latest Sign Of Emerging Nuclear Arms Race

The Indian government announced yesterday that it had conducted the first flight test of its Agni-5 ballistic missile “with Multiple Independently Targetable Re-Entry Vehicle (MIRV) technology.

While the Indian government may rejoice in its technical achievement, the proliferation of MIRV capability is a sign of a larger worrisome trend in worldwide nuclear arsenals that is already showing signs of an emerging nuclear arms race with more de-stabilizing MIRVed missiles.

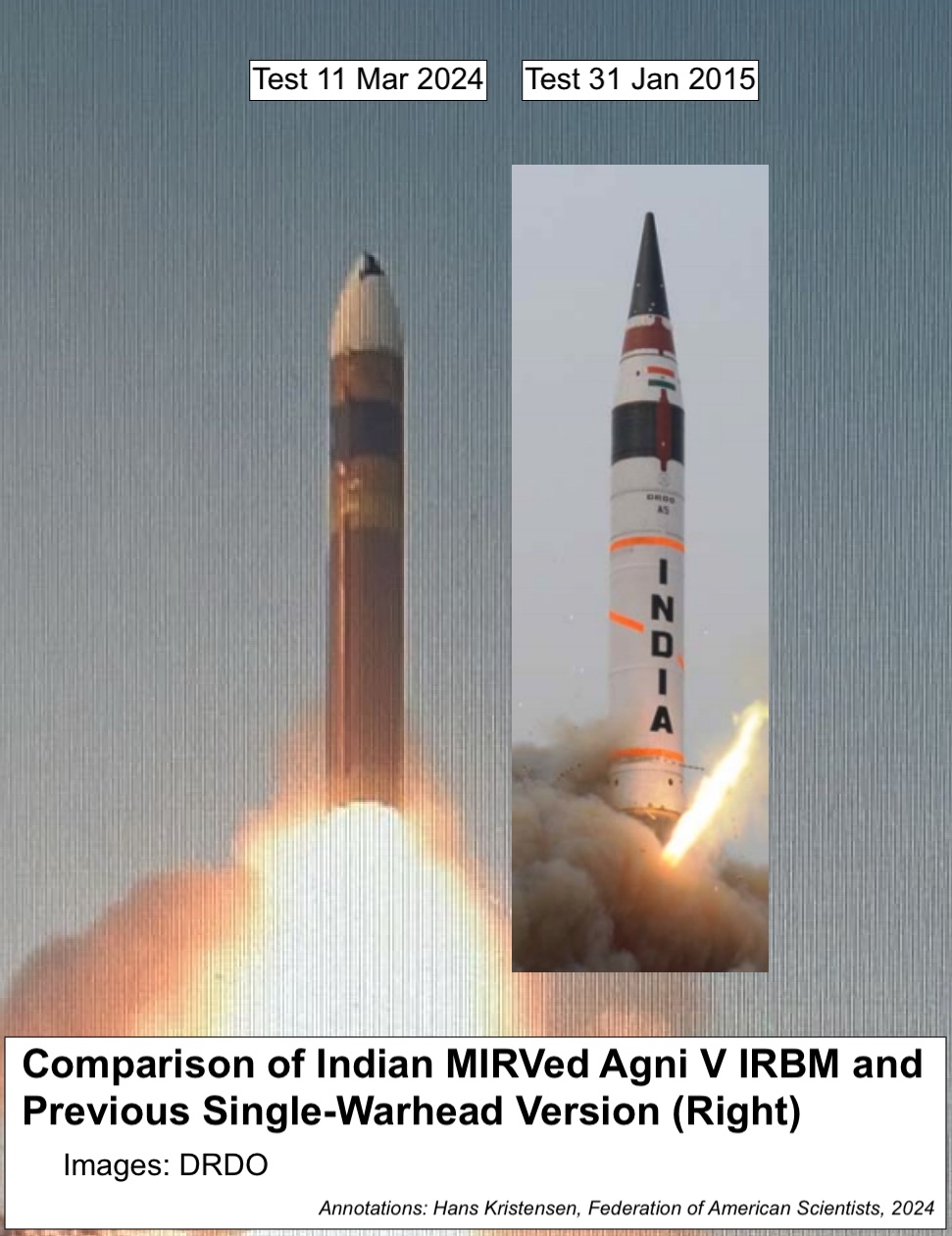

A photo of the launch published by the Indian Defense Research and Development Organization (DRDO) shows that the payload section has been significantly modified compared with the Agni-5 missiles used in earlier tests (see below).

A Planet Labs satellite image dated 9 March 2024 shows what appears to be an Agni-5 road-mobile launcher parked on the launch pad at the missile test launch facility on Abdul Kalam Island on India’s north-east coast. This is presumably the launcher that was used to test launch the MIRVed Agni-5 two days later (see image below).

Reports have circulated for two decades about the Indian defense industry working on MIRV technology. Some have suggested that a MIRV capability might exist for the Agni-3 medium-range missile, which is currently being fielded with the Indian army, but this has not yet been confirmed. Unconfirmed press reports also said that an Agni-P medium-range missile test in December 2021 carried two reentry vehicles to simulate MIRV capability.

The Indian government says that the latest Agni-5 test––named Mission Divyastra––was the first time that this missile had successfully demonstrated MIRV technology. If so, it will likely take several additional flight tests to complete the development of an operational MIRV capability for the Agni-5. Yet the test-launch demonstration of MIRV capability on the Agni-5 with a significantly modified payload section marks a significant development for India’s nuclear posture, and faster than we anticipated just a few years ago.

Significant integration work on Agni-5 road-mobile launchers has been visible at the Shampirpet Missile Complex northeast of Hyderabad for the past several years (see image below). The launchers appear to match the one seen on Abdul Kalam Island.

The bigger picture is that India’s pursuit of MIRV capability is a warning sign of an emerging arms race: It follows China’s deployment of MIRVs on some of its DF-5 ICBMs, Pakistan’s apparent pursuit of MIRVs for its Ababeel medium-range missile, North Korea may also be pursuing MIRV technology, and the United Kingdom has decided to increase its nuclear stockpile to enable it to deploy more warheads on its submarine-launched missiles.

This proliferation of MIRV capability follows the failure of the United States and Russia to implement the ban on MIRV on land-based missiles they agreed to in the START-II treaty in the 1990s. Instead, Russia is replacing all its single-warhead ICBMs with types capable of carrying multiple warheads, and there is a push in the United States to re-MIRV its deployed ICBMs.

The capability to deploy multiple warheads on each missile is one of the most dangerous developments of the nuclear era because it is one of the quickest ways for nuclear-armed states to significantly increase their number of deployed warheads and develop the capability to rapidly destroy large numbers of targets. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, MIRV capability resulted in a massive increase of US and Soviet nuclear arsenals. And MIRVing is a key element of the US projection that China might have 1,000 operational warheads by 2030. When the New START treaty expires in two years and the United States and Russia fail to agree to new limits on their strategic forces, both countries could upload hundreds of additional warheads onto their already deployed systems.

Although all 400 deployed US ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that is capable of carrying up to three warheads each. The United States could also upload each of its deployed Trident SLBMs with a full complement of eight warheads, rather than the current average of four to five. Meanwhile, we estimate that Russia also maintains a significant upload capacity, given that many of their ICBMs and SLBMs had been previously downloaded in order to meet New START’s central limits on deployed warheads. For both countries, these changes could be made within weeks to months for the submarines, and within months to years for the ICBMs.

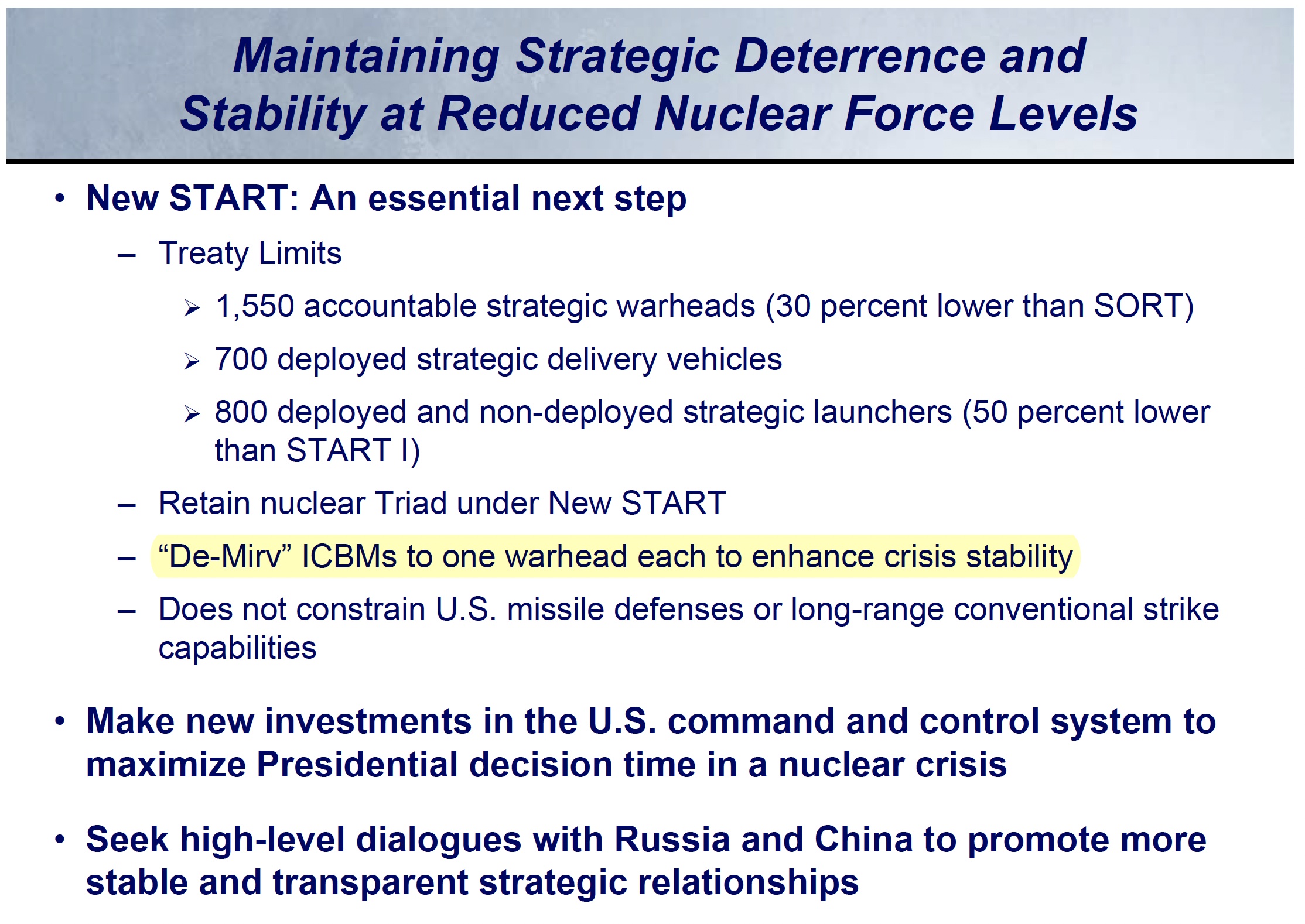

The US decided to “de-MIRV” its ICBMs in recognition of the de-stabilizing effect of MIRV on land-based ballistic missiles.

A world in which nearly all nuclear-armed countries deploy significant MIRV capability looks far more dangerous than our current geostrategic environment. This is because the highly destructive capacity of MIRVs means that they are both potential first-strike weapons and juicy first-strike targets. Not only would widespread MIRV deployments likely spur on the global nuclear arms competition by deepening worst-case force posture planning, but it would dramatically reduce crisis stability by incentivizing leaders to launch their nuclear weapons quickly in a crisis (the US explicitly decided to “de-MIRV” its deployed ICBMs to “enhance crisis stability”).

One would think, despite their differences, that all nuclear-armed states should be able to agree that a MIRV-race is neither in their national security interests nor those of the rest of the world. But we’re not holding our breath.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.