How to Build Effective Digital Permitting Products in Government

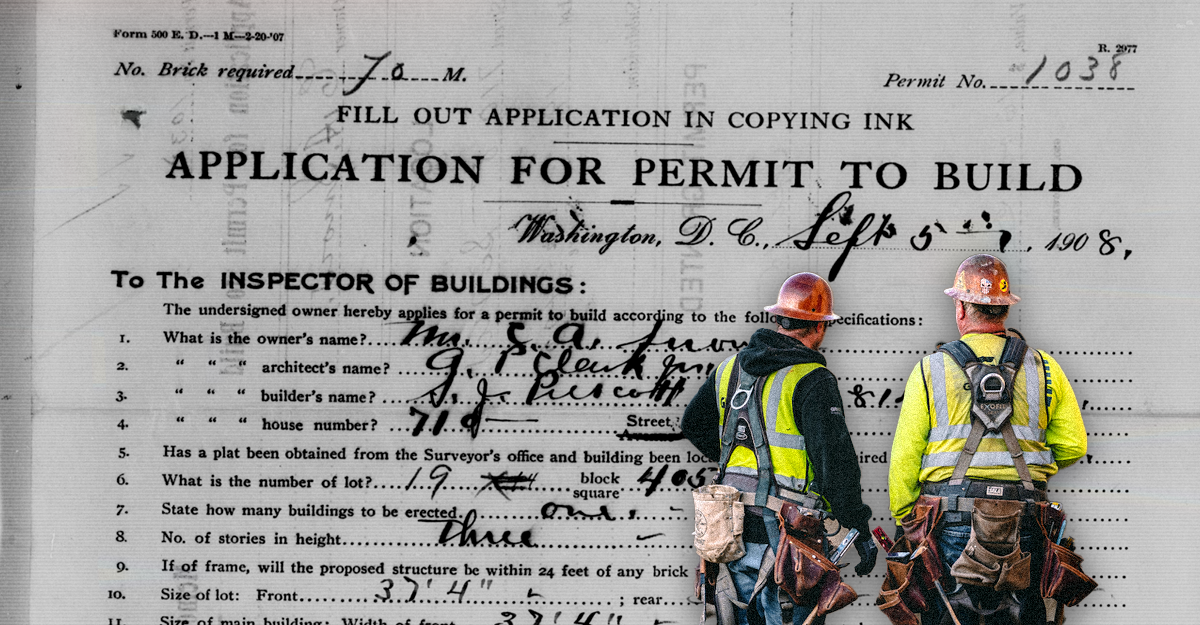

The success of historic federal investments in climate resilience, clean energy, and new infrastructure hinges on the government’s ability to efficiently permit, site, and build projects. Many of these projects are subject to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which dictates the procedures agencies must use to anticipate environmental, social, and economic impacts of potential actions.

Agencies use digital tools throughout the permitting process for a variety of tasks including permit data collection and application development, analysis, surveys, impact assessments, public comment processing, and post-permit monitoring. However, many of the technology tools presently used in NEPA processes are fragmented, opaque, and lack user-friendly features. Investments in permitting technology (such as software, decision support tools, data standards, and automation) could reduce the long timelines that plague environmental review. In fact, the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ)’s recent report to Congress highlights the “tremendous potential” for technology to improve the efficiency and responsiveness of environmental review.

The Permitting Council, a federal agency focused on improving the “transparency, predictability, and outcomes” of federal permitting processes, recently invested $30 million in technology projects at various agencies to “strengthen the efficiency and predictability of environmental review.” Agencies are also investing in their own technology tools aimed at improving various parts of the environmental review process. As just one example, the Department of Energy’s Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorizations and Permits (CITAP) Program recently released a new web portal designed to create more seamless communication between agencies and applicants.

Yet permitting innovation is still moving at a slow pace and not all agencies have dedicated funding to develop needed technology tools for permitting. We recently wrote a case study about the Department of Transportation’s Freight Logistics Optimization Works (FLOW) project to illustrate how agency staff can make progress in developing technology without large upfront funding investments or staff time. FLOW is a public-private partnership that supports transportation industry users in anticipating and responding to supply chain disruptions. Andrew Petritin, who we interviewed for our case study, was a member of the team that co-created this digital product with users.

In a prior case study, Jennifer Pahlka and Allie Harris identified strategies that contributed to DOT FLOW’s success in building a great digital product in government. Here, we expand on a subset of these strategies and how they can be applied to build great digital products in the permitting sector. We also point to several permitting technology efforts that have benefited from independently applying similar strategies to demonstrate how agencies with permitting responsibilities can approach building digital products. These case studies and insights serve as inspiration for how agencies can make positive change even when substantive barriers exist.

Make data function as a compass, not a grade.

Here is an illustrative example of how data can be used as a compass to inform decisions and provide situational awareness to customers.

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) recently launched a Permitting Mapping Tool to support grantees and others in deploying infrastructure by identifying permitting requirements and potential environmental impacts. This is a tool that both industry and the public can use to see the permitting requirements for a geographic location. The data gathered and shared through this tool is not intended to assess performance; rather, it is used to provide an understanding of the landscape to support decision making.

NTIA staff recognized the potential value of the Federal Communication Commission’s (FFC) existing map of broadband serviceable locations to users in the permitting process and worked to combine it with other available information in order to support decision making. According to NTIA staff, NTIA’s in-house data analysts started prototyping mapping tools to see how they could better support their customers by using the FCC’s information about broadband serviceable locations. They first overlaid federal land management agency boundaries and showed other agencies where deployments will be required on federal lands in remote and unserved areas, where they might not have a lot of staff to process permits. The team then pulled in hundreds of publicly available data sources to illustrate where deployments will occur on state and Tribal lands and in or near protected environmental resources including wetlands, floodplains, and critical habitats before releasing the application on NTIA’s website with an instructional video. Notably, NTIA staff were able to make substantial progress prior to receiving Permitting Council funds to support grant applicants in using the environment screening to improve the efficiency of categorical exclusions processing.

Build trust. Trust allows you to co-create with your users. Understand your users’ needs, don’t solicit advice.

Recent recipients of Permitting Council grants for technology development have the opportunity to define their customers and work with them from day one to understand their needs. Rather than assuming their customer’s pain points, grant recipients can gather input from their customers and build the new technology to meet their needs. Recipients can learn from FLOW’s example by building trust early through direct collaboration. Examples of strategies agencies can use to engage customers include defining user personas for their technology; facilitating user interviews to understand their needs; visiting field offices to meet their customers and learn how technology integrates into their work processes and environment; conducting observations of existing technologies to assess opportunities for improvement; and rapidly prototyping, testing, and iterating their solutions with user feedback.

In the longer term, the Permitting Council and other funding entities can drive the adoption of a user-center approach to technology development through their future grant requirements. By incorporating user research, user testing, and agile methodologies in their requests for proposals, the Permitting Council and others can set clear expectations for user involvement throughout the technology development process.

In comparison to DOT FLOW, where the customers are largely external to the federal government, the customers and stakeholders for permitting technology include internal federal employees with responsibilities for preparing, reviewing, and publishing NEPA documentation. But even if your end-users are within your organization (or even on your same team!), the principles of building trust, co-creating, and understanding user needs still apply.

Fight trade-off denial.

When approaching the complex process of permitting and developing technological tools to support customers, it is critical for teams to focus on a specific problem and prioritize user needs to develop a minimum viable product (MVP). A great example of this is the Department of Energy (DOE)’s Coordinated Interagency Transmission Authorizations and Permits Program (CITAP).

DOE collaborated with a development team at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory to create a new portal for interstate transmission applications requiring environmental review and compliance. The team applied a “user-centered, agile approach” to develop and deploy the new tool by the effective date for new CITAP regulations. The tool streamlines communication by allowing the project proponent to track the status of the permit, submit documentation, and communicate with DOE through the platform. Through iterative development, DOE plans to expand the system to include additional users, including cooperating agencies, and provide the ability for cooperating agencies to receive applicant-submitted materials. Deprioritizing these desired functions in the initial release required tradeoffs and a prioritization of user needs, but enabled the team to ultimately meet its deadline and provide near-term value to the public.

Prioritizing functionality and activities for improvements in permitting can be challenging, but it is critical that agencies make decisions on where to focus and start small with any technology development. Having more accessible data can help inform these trade off decisions by providing an assessment of problem criticality and impact.

Don’t just reduce burden – provide value.

Our partners at EPIC recently wrote about the opportunity to operationalize rules and regulations in permitting technology. They discussed how AI could be applied to: (1) help answer permitting questions using a database of rulings, guidelines, and past projects; (2) verify compliance of permits and analyses with up-to-date legal requirements, and (3) automatically apply legal updates impacting permitting procedures to analyses. These examples illustrate how improving permitting technology can not only reduce burdens on the permitting workforce, but simultaneously provide value by offering decision support tools.

Fund products, not projects.

The federal government often uses the project funding model for developing and modernizing technology. This approach provides different levels of funding based on a specific waterfall process step (e.g., requirements gathering, development, and operations and maintenance). While straightforward, this model provides little flexibility for iteration and little support for modernization and maintenance. Jen Pahlka, former U.S. Deputy Chief Technology Officer, recommends the government move towards a product funding model that acknowledges software development never ends, rather there is ongoing work to improve technology over time. This requires steady levels of funding and has implications for talent.

Permitting teams should be considering these different models when developing new technology and tools. Whether procuring technology or developing it in-house, teams should be thinking about how they can support long-term technology development and hire employees with the knowledge, skills, and abilities to effectively manage the technology. Where relevant, agencies should seek to fund products. While product funding models may seem onerous at first, they are likely to have lower costs and enable teams to respond more effectively to user needs over time.

Several existing resources support product development in government. The 18F unit, part of the General Services Administration (GSA)’s Technology Transformation Services (TTS), helps federal agencies build, share, and buy technology products. 18F offers a number of tools to support agencies with product management. GSA’s IT Modernization Centers of Excellence can support agency staff in using a product-focused approach. The Centers focused on Contact Center, Customer Experience, and Data and Analytics may be most relevant for agencies building permitting technology. Finally, the U.S. Digital Service (USDS) “collaborates with public servants throughout the government”; their staff can assist with product, strategy, and operations as well as procurement and user experience. Agencies can also look to the private sector and NGOs for compelling examples of product development.

Looking forward

Agency staff can deploy tactics like those outlined above to quickly improve permitting technology using existing authorities and resources. But these tactics should complement, not substitute, a longer-term systemic strategy for improving the U.S. permitting ecosystem. Center of government entities and individual agencies need to be thinking holistically about shared user needs across processes and technologies. As CEQ stated in their report, where there are shared needs, there should be shared services. Government leadership must equip successful small-scale projects with the resources and guidance needed to scale effectively.

Additionally, there needs to be an investment from the government in developing effective permitting technology, with technical talent (product managers, developers, user researchers, data scientists) hired to support these efforts).

As the government continues to modernize to meet emerging challenges, it will need to adopt best practices from industry and compete for the talent to bring their visions to life. Sustained investment in interagency collaboration, talent, and training can shift the status quo from pockets of innovation (such as DOT FLOW and other examples highlighted here) to an innovation ecosystem guided by a robust, shared product strategy.

The Philanthropy Partnerships Summit demonstrated both the urgency and the opportunity of deeper collaboration between sectors that share a common goal of advancing discovery and ensuring that its benefits reach people and communities everywhere.

We’re launching a national series of digital service retrospectives to capture hard-won lessons, surface what worked, be clear-eyed about what didn’t, and bring digital service experts together to imagine next-generation models for digital government.

In a year when management issues like human capital, IT modernization, and improper payments have received greater attention from the public, examining this PMA tells us a lot about where the Administration’s policy is going to be focused through its last three years.

Congress must enact a Digital Public Infrastructure Act, a recognition that the government’s most fundamental responsibility in the digital era is to provide a solid, trustworthy foundation upon which people, businesses, and communities can build.