Rebuilding Environmental Governance: Understanding the Foundations

Today we are facing persistent, complex, and accelerating environmental challenges that require adding new approaches to existing environmental governance frameworks. The scale of some of them, such as climate change, require rethinking our regulatory tools, while diffuse sources of pollutants present additional difficulties. At the same time, effective governance systems must accommodate the addition of new infrastructure, housing, and energy delivery to support communities. Our legal framework must be sufficiently stable to enable regulation, investment, and innovation to proceed without the discontinuities and gridlock of the past few decades.

In an increasingly divided atmosphere, it will take candid, multiperspective dialogue to identify paths toward such a framework. This discussion paper explores the baseline that we’re building on and some key dynamics to consider as we think about the durable systems, approaches, and capacity needed to achieve today’s multiple societal goals.

Our environmental system was built for 1970s-era pollution control, but today it needs stable, integrated, multi-level governance that can make tradeoffs, share and use evidence, and deliver infrastructure while demonstrating that improved trust and participation are essential to future progress.

Implications for democratic governance

- Invest in strategic communications to build durable public understanding of environmental measures.

- Redesign public participation and engagement to transparently and rapidly weigh the inevitable trade-offs to a decision through open and informed consideration guided by clearly articulated principles.

Capacity needs

Modernize today’s system of cooperative federalism to address the lack of clear and intentional interconnections, adaptive feedback loops, and aligned objective, by:

- Rebuilding and sharing the data backbone at the state/local level, including working to preserve and sustain current environmental data; over time, expand interoperable data collection and make it genuinely usable to support consistent, evidence based state and local action.

- Using state/local powers for climate progress, integrating zoning, land use, infrastructure, and public health authorities into a whole-of-government discussion to address climate.

- Strengthening public sector networks to share data, best practices, and innovations across jurisdictions.

- Investing in tech-enabled capacity for states and local governments, (such as AI for decision support), satellite imagery, remote sensing, and digital modeling to lower the cost of monitoring, risk assessment, permitting, and compliance.

The early 20th Century saw the emergence of our first national laws regulating public resources— the Federal Power Act in the 1930s, the precursor to the Clean Water Act in the 1940s, and the first version of the Clean Air Act in the 1950s. Then, in a concentrated decade of new laws and massive amendments to existing ones, the 1970s saw a focus on assessing, controlling, and reducing pollution, while setting ambitious goals for human and ecosystem health. These statutes generally were constructed around specific resources—airsheds, watersheds, public lands, and wildlife habitat—and articulated specific roles for federal agencies and other levels of government. State efforts were incorporated into a nationwide system of cooperative federalism, while many states undertook their own initiatives to address environmental problems.

For half a century these laws—enacted with overwhelming, bipartisan congressional support— produced a great deal of success, with conventional pollution decreasing across many resources and regions and some species and habitats recovering. But we have plateaued in terms of broad improvements, and meanwhile novel pollutants and more diffuse, global threats have emerged. Political shifts, legacy economic interests, and a changing information landscape have played an important role, as amply recounted elsewhere.

The bipartisan legislation of the 1970s arose from both idealism and necessity, during an Earth Day moment that embraced ecological thinking in response to tangible harms to humans and the environment. The laws enjoyed massive public support and got many things right. Some were aspirational and holistic, such as the Clean Water Act’s “zero-discharge” target or NEPA’s vision “to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony, and fulfill the social, economic, and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans.” The latter Act established the Council on Environmental Quality to coordinate this policy across the entire federal government.

Other advances came piecemeal, focused on specific resources. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) was cobbled together by an executive plan to reorganize several existing agencies and offices, then granted authority in a series of media-specific statutes that began with the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Safe Drinking Water Act, and later the Toxic Substances Control Act and Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act. The Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, Superfund, and Oil Pollution Act addressed hazardous substances affecting the nation’s health and ecosystems. Implementation of all these laws required the Agency to develop in-house scientific expertise and detailed regulations that fleshed out statutory standards and applied them to specific sectors—an approach upheld for decades by the Supreme Court.

These laws made unquestionable progress on conventional pollution and waste, the visible, toxic byproducts of industrial production and consumer culture that had spurred the environmental movement and drawn a generation of lawyers to the new profession. But with specialization came fragmentation of environmental law into a plethora of subtopics, and a managerial, permit-centric legal culture that risked losing sight of ecological goals. Nor were the benefits distributed equally by race or class, as demonstrated by pioneering studies in the field of environmental justice.

As the field matured, it slowed, with congressional interventions becoming less frequent and more technical. Some of the last major amendments to a bedrock environmental statute were the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, enacted by a bipartisan Congress and signed by President George H.W. Bush. (The other prominent example is the Frank R. Lautenberg Chemical Safety for the 21st Century Act (Lautenberg Chemical Safety Act), a major amendment to TSCA in 2016.) Absent updated legislation, EPA regulations became paramount, but these had to run a gauntlet of shifting policy priorities, complex rulemaking procedures, litigation, and a transformed and often skeptical Supreme Court.

Critiques of this system date back almost as far as the statutes themselves. One ELI study listed 34 major “rethinking” efforts emanating from academia, blue-ribbon commissions, and NGOs between 1985 and 2014, across the political spectrum and ranging from incremental reforms to radical reinvention. One highly touted initiative, led by sitting Vice President Al Gore, resulted in some modest administrative streamlining. Most remained paper exercises, appealing to good-government advocates but lacking political support.

The stakes grew higher with increasing awareness of climate change. In June 1988, NASA and book-length treatments followed, sparking broad discussion of what was then a fully bipartisan issue. Vice President Bush campaigned on addressing it, and as President in 1992, he traveled to Rio de Janeiro to sign the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change. With successes like the 1987 Montreal Protocol on the ozone layer or EPA’s 1990 Acid Rain Program doubtless in mind, the Senate ratified the Framework Convention 92-0.

But climate change implicates much larger portions of the U.S. economy—energy, transportation, agriculture—at individual as well as industrial scales. While NEPA embodied the 1960s slogan that “everything is connected,” the lesson of climate change is that many things emit greenhouse gases, and all things will be affected by global warming. The need for systemic change proved to be an uneasy fit with existing site-specific, media-specific environmental laws.

Growing awareness of climate change and the scale of action needed to address it also generated a backlash from entrenched economic interests. By the mid-2000s, the Bush/Cheney administration had reversed course on federal climate commitments. It contested and lost Massachusetts v. EPA, a landmark ruling in which a narrowly divided Supreme Court held that the Clean Air Act applies to greenhouse gas emissions that affect the climate.

The Administration’s argument was captured by Justice Antonin Scalia’s flippant remark in dissent that “everything airborne, from Frisbees to flatulence, [would] qualif[y] as an ‘air pollutant.’” In Scalia’s opinion, real pollution must be visible, earthbound, toxic, inhaled, not a matter of colorless molecules interacting in the stratosphere. Even in dissent, this view set the stage for subsequent legal battles, right up to the present effort to revoke EPA’s 2009 “endangerment finding” that is now the underpinning of federal greenhouse gas regulation.

Climate change likewise laid bare the long-standing divide between environmental law, which historically regulated the power sector in terms of its fuel inputs and combustion byproducts, and energy and utility law, which focused more on transmission and distribution of the resulting power. (Both fields are further divided among federal, state, and local authorities, as discussed below.) Vehicle emissions similarly are regulated via both EPA tailpipe standards and National Highway Transportation and Safety Administration mileage standards, with California authorized to propose more stringent ones. When coordinated, this multi-headed structure produces steady advances, but in deregulatory moments it has become fertile ground for opportunism, retrenchment, and delay.

At the federal level, these questions have been exacerbated by massive shifts in administrative law, long the building block of environmental law and climate action, and in federal court rulings on the separation of powers, implicating the authority of federal agencies to issue and enforce rules. Successive administrations have run afoul of the current Supreme Court majority, whose “major questions doctrine” casts a shadow both on attempts to fit new problems into once-expansive environmental statutes, and on “whole of government” approaches that attempt to address climate change’s sources and impacts across the entire economy.

Tentative attempts by presidents to leverage executive power and emergency authority have been curtailed when invoked for regulatory purposes, but are running strong in deregulatory efforts and executive actions in the service of “energy dominance.” Whether the Supreme Court will articulate some principled limits, and whether those will be even-handedly applied to future administrations, remains to be seen. Meanwhile, the past year has seen a large-scale push to reduce environmental regulation, in parallel with abrupt reorganizations and steep reductions in the federal workforce and agency budgets. These actions were joined by sharp declines in environmental enforcement and U.S. withdrawal from environmental and climate-related international instruments and bodies.

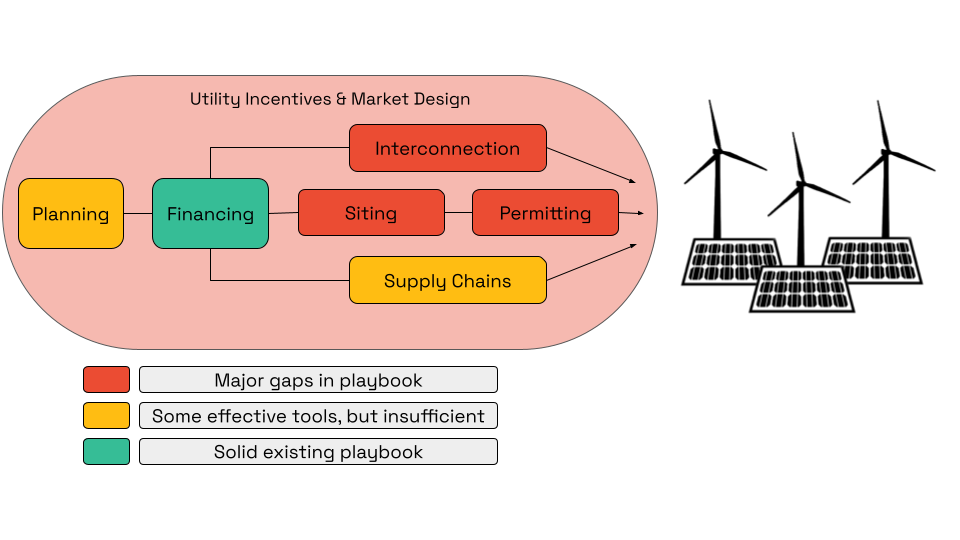

In this uncertain atmosphere, attention has turned to new technologies and building the necessary infrastructure to effect growth in low- and zero-carbon energy. As clean energy alternatives have matured and become economically competitive, the climate imperative is pushing against long-standing environmental review and permitting procedures. That may well include NEPA, which is now attracting attention from all three branches of government and a robust debate about whether, or how much, its procedures might be slowing energy deployment.

Environmental issues were federalized for a reason: to counter pollution that crosses state borders and to prevent a race to the bottom. But decades of implementation have seen the blunting of some tools, expansion of others, and identification of gaps. Moving forward requires reaffirming that the environment is inseparable from societal health and well-being, economic stability, and energy systems. Any serious response must orient governance toward decarbonization, while embedding accountability, equity, and justice from the outset rather than inconsistently and often inadequately after the fact. Doing all this without sacrificing hard-won environmental gains will not be easy.

To meet the challenge of the worldwide crises of biodiversity loss, pollution overload, and climate change, creation of any new structure must be rooted in understanding the existing baseline for environmental governance.

- Cross-Cutting Objectives: Effective governance paths must overcome the persistent false dichotomy between the environment and the economy, making clear that energy production, economic prosperity, ecosystem health, and societal well-being are inextricably linked. Improved trust and participation are essential to sustaining and accelerating progress across these interconnected goals.

- Democracy, Expertise, and Regulatory Certainty: Our legacy environmental laws have seen many successes, but their media- and site-specific tendencies are in tension with the scale of action needed to decarbonize our economy, conserve biodiversity, and control pollution. Eroded trust, accreted layers of process, and increasingly extreme political actions and reactions hamstring progress. At the same time, rapidly advancing scientific knowledge and technology have greatly expanded our ability to anticipate environmental challenges and understand and react to the impacts of our actions. Harnessing these tools effectively can help us improve and accelerate our decisionmaking processes.

- Building a Structure Fit for Purpose: Environmental law necessarily operates at multiple scales: global, national, tribal, regional, state, and local. Our system of cooperative federalism centers authority around the federal and state governments, backstopped by treaty obligations, interstate compacts, and traditional state and local authority over land use and public safety and welfare. A strong cooperative federalism framework can foster collaboration across subnational jurisdictions, including by leaning into data collection, analysis, and dissemination to support decisionmaking. In addition, understanding the effects and drivers of private sector environmental actions can help to identify ways to leverage those actions to augment and fill gaps in public governance.

Cross-Cutting Objectives

Inseparable: Environment, Energy, Economy, and Society

The past half-century has demonstrated the impossibility of severing the environment from the economy, energy production, and social well-being. We must ensure the false dichotomy between environmental protection and economic development, characterized by an oversimplified idea that the two are in a zero-sum competition, also fades. The decades-old concept of sustainability (or triple bottom line) has not yet made its way into many of our foundational laws and governance structures.

Ignoring the complex relationships among environment, energy, the economy, and society favors short-term decisions that externalize impacts. This underlies the longstanding debate over the accuracy and efficacy of cost-benefit analyses, throughout their 40-plus year federal history, including questions about scope and how they handle uncertainty. For any project or program, system designers that consider an integrated suite of factors that move beyond basic environmental parameters or economic indicators (from public health to workforce development, from the supply chain to community well-being) have a greater chance of cross-sector success.

These governance challenges are also inseparable from shifts in how finance flows. Public and private financial tools—from subsidies and tax credits to loans, grants, and community-based financing—are increasingly shaping market behavior and determining whether policy objectives translate into real-world outcomes. Who controls these tools, how they are deployed, and when capital is made available all play a central role in driving or constraining environmental progress.

Bridging these gaps is, of course, easier said than done. But widening the aperture of considerations can connect decisionmaking to holistic industrial policies that account for a wider range of economic, social, and environmental factors. Accounting for this wider range isn’t just a nice-to-have, but essential to shared prosperity.

Foundational: Trust and Participation

A process, project, or program will move at the speed of trust—no faster and no slower. This refers to trust in institutions, in science, and in process.

Trust is earned through consistent transparency, clear accountability, and demonstrated responsiveness. For governance systems to function at the scale and pace required today, these principles must be embedded in decisionmaking in ways that are coherent and durable, rather than fragmented across a series of disparate steps and entities. Our traditional frameworks contain mechanisms to solicit and incorporate public input. But those mechanisms have limitations for all involved, both those trying to make their voice heard and those proposing the action and receiving input. (These range from when and how often participation occurs in the decisionmaking process to how the input is incorporated and decisions communicated.) Participation is foundational to our regulatory democracy and must occur early enough and in meaningful ways to improve decisions.

Effective participation also depends on clarity. People must be able to understand how decisions are made, what tradeoffs are being weighed, and where and how engagement can influence outcomes. But our frameworks still reflect reliance on elite and professional representation rather than widespread engagement. Trust—and the durability of outcomes—will increase when our processes have clearly articulated principles, transparently and rapidly weigh tradeoffs, and come to decisions through open and informed consideration.

The Concurrent Risk and Promise of Technology

Mechanization and industrialization created both unprecedented wealth and the pollutants that were the target of the 1970s wave of environmental laws. Emerging technologies likewise offer great promise, but also place familiar stresses—greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption, land use, waste—on the ecosystem and on human health and well-being. Our existing laws will need to respond and adapt to these problems as data centers and other novel demands reach greater scale, even as we evolve new ways of balancing those technologies’ potential against their up-front impacts and opportunity costs.

Technology also offers a potential path through the climate crisis, as solar and wind energy have become scalable and cost-competitive with traditional fossil fuels. Other clean technologies on the horizon, such as geothermal or fusion energy, retain bipartisan support and will require legal and regulatory guardrails if they mature and are integrated into the system. Battery storage and energy efficiency advances will help manage and reduce energy demand, and carbon removal and sequestration technologies may also play a role in curbing emissions. And at the outer limits of our knowledge, various geoengineering concepts are raising difficult questions about feasibility, decisionmaking procedures, unintended consequences, and accountability.

New technologies are also helping shape the implementation of environmental law in important ways. Existing tools such as satellite imaging, GPS location and geographic information systems, remote monitoring and sensing, and drones have fundamentally altered the way we view and record data from the physical world, in close to real time. Computer modeling and simulations have been a mainstay of climate science and policy, and other software innovations may improve environmental governance, including addressing long-standing issues of government transparency and public participation.

Effective messaging is essential to enhancing public understanding of interconnected issues and support for responses. It should be tailored to specific jurisdictions and informed by advances in research (e.g., behavioral science), learn from those thriving in today’s information ecosystem, and embrace strategies for reducing polarization.

How can we identify and address barriers to the development and equitable deployment of technologies that advance environmental protection while limiting their negative impacts.

Democracy, Expertise, and Regulatory Certainty

In a healthy democracy, public policy is guided by evidence, and truth is the shared foundation for collective decisionmaking, whatever the chosen outcome. When facts and scientific expertise are dismissed or minimized in favor of ideology, however, it becomes harder for citizens to deliberate, solve problems, and hold leaders accountable. The diminution and marginalization of science contribute to the erosion of democracy itself.

In the United States, our ability to build necessary infrastructure and take action has been slowed by the long timelines and sometimes overlapping requirements of our regulatory processes. This is exacerbated by the increasingly extreme policy swings we have been experiencing between administrations. The result is the twin challenge of how to increase the pace of our processes without lessening their protections, while also making our decisions more stable and durable.

Aligning Regulatory Certainty and Timelines

Regulatory certainty is not the same thing as rigidity. When done correctly, it can be the backdrop against which communities are able to plan for the future and companies can make informed decisions about where and how to invest. Regulation that is sufficiently clear on stable objectives does not have as much space in which to swing.

Long horizons with clear milestones matter: think of a national clean electricity standard, or the emissions-based equivalent, set on a 15- to 20-year glidepath. Confidence in long-term decisions, however, stems from effective inclusion, holistic analysis, and transparent decisions. The perspectives of subject-matter experts (in-house and external), and of those who manage and care about the resources or land in question, should be considered essential and actively pursued by policymakers.

Program-level thinking can help inform decisions at the project level. The energy transition will be remembered for feats of engineering—the thousands of miles of transmission lines, the buildout of battery storage—but its success will be determined by whether our framework listens, incorporates needed expertise, and produces rules that last long enough for people to plan their lives.

Evidence-Based Decisionmaking

For decades, the principle that good decisions require a good evidence base has been axiomatic. Dating back to 1945, the federal government has invested in science as a discipline and an idea, with government supporting the research to be conducted by public institutions and delivered as socially useful goods by the private sector.

Incorporating meaningful, often complex, evidence—including scientific data, traditional knowledge, and the needs, concerns, and priorities of potentially affected individuals—into decisionmaking is increasingly fraught. Climate change illustrates these challenges: despite decades of understanding by government officials and private sector decisionmakers about its causes and the need to act, economic and social interests have prevented effective policy and legislative response. Decisions are as good as the information they are based on. Emissions reductions ultimately depend not just on technical knowledge, but on institutions and governments capable of acting on that knowledge independently, transparently, and free from corruption and clientelism.

In a study assessing the effectiveness of the federal government’s efforts to improve evidence-based decisionmaking, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found mixed progress in: (1) developing relevant and high-quality evidence; (2) employing it in decisionmaking; and (3) ensuring adequate capacity to undertake those activities. These are foundational problems.

Compounding our challenges in making legislative and policy decisions based on accurate and pertinent evidence is the siren song of AI. Artificial intelligence promises many tools, ranging in complexity and autonomy from providing clerical tasks to generating substantive recommendations. (AI Clerical Assistive Systems automate certain administrative and procedural tasks, such as document classification and automatic transcription, and AI Recommendation Systems can contribute to judicial decision-making, for example, by analyzing legal codes and case precedents. Paul Grimm et al.)

AI is already being used across jurisdictions and agencies for environmental regulation, including planning, reviewing proposals, drafting environmental reviews, public participation and engagement, monitoring compliance, and enforcement. Recent federal policy has fueled the AI flame, with a 2025 AI action plan and multiple Executive Orders that offer the power to expedite permitting processes.

Enormous governance questions around AI have yet to be resolved. Technologies built by people reflect the values and assumptions of those who built them, and their use shifts power in decisionmaking processes. If a judge were called upon to review a decision made by such a tool, how could she determine the finding was reasonable under existing standards of administrative law? Can machine-generated analysis satisfy NEPA’s “hard look” review? These types of governance concerns dog AI tools wherever they are deployed but become particularly critical when they have the potential to become the decisionmaker in our legal and regulatory system.

The importance of having rigorous systems for identifying and considering trusted information to ground collective and democratic decisionmaking cannot be overstated. Until recently, dozens of scientific advisory committees routinely advised federal agencies to help bridge information gaps. Staggering recent losses of federal research funding and government programs and scrubbing of essential data sets means any path forward will likely require significant investments of both financial and human capital. When we rebuild, priority should be placed on ensuring all participants in decisionmaking have access to the same evidence, supported by the same systems.

Frontloading Regulatory Decisionmaking

Even as we work to improve how evidence informs decisionmaking, we face growing risks, uncertainties, and tradeoffs. The challenge is not simply to generate more information, but to make better use of what we already know through regulatory systems that reflect the integrated nature of the problems we face—without mistaking uncertainty for an absence of evidence.

Many conflicts arise because decisions are fragmented across regulatory silos and institutions. Consider a proposed electrical transmission line crossing a wetland. Decisionmakers must balance the imperatives of the energy transition, the conservation of biodiversity, the protection of water resources, and local economic opportunities. Yet these factors may be evaluated at different times, at different scales, and by different agencies. As a result, environmental permitting decisions can be made in isolation, long after foundational choices about the project’s purpose and design have already been locked in.

By the time site-specific questions arise, such as whether a particular wetland falls within the narrowed jurisdiction of the Clean Water Act, many broader tradeoffs have already been foreclosed.

A holistic approach would entail identifying the priority of certain projects and a system for weighing their impacts. For example, infrastructure decisions could happen at a systemic scale such as nationwide grid needs, providing context for decisions about individual projects and resources. Our decisionmaking processes need systems for weighing tradeoffs, and making them transparent, to enable systems-level planning and prioritization and effective engagement.

Hard decisions will have to be made regarding prioritized (and thus deprioritized) objectives. But frontloading data gathering, assessment, and decisionmaking on a national scale—through meaningful scenario planning, for example—could reduce the number of decisions made much further down the line in a project lifecycle and temper the uncertainty that can stem from permitting officials’ discretion.

We will be facing these types of tradeoffs with increasing frequency as needs mount to build infrastructure and housing, retreat from our coasts, manage and conserve species and ecosystems, and respond to and prepare for increasingly frequent and severe emergencies. In addition to an integrated approach for assessing impacts and making tradeoffs transparent, the system will need certain decisions to be made earlier in the decisionmaking processes and with a broader scope.

Acting (and Adapting) Amidst Uncertainty

Core tenets of administrative law structure decisionmaking with up front analysis and assume that we have full—or at least sufficient—information about circumstances and potential impacts to support a decision. But this is not always the case. When there are substantial uncertainties about conditions or the possible impacts of an action or rulemaking, adaptive management can improve outcomes by taking an iterative, systematic approach.

The uncertainties brought on by changing conditions due to climate impacts and unknowns about the consequences of proposed actions may call for an adaptive approach. And there are other situations where establishing sufficient evidence before taking irreversible action is appropriate. For example, we currently have limited understanding of the potential local and global impacts of geoengineering proposals to release aerosols into the atmosphere to block the sun’s rays, nor are there governing mechanisms in place to address them.

There are also situations where it is important to ensure that we do not indefinitely postpone action due to a desire to have all the answers before acting, such as infrastructure for transitioning away from fossil fuel combustion. When appropriate, effective adaptive management plans include procedural and substantive safeguards such as clear goals to set an agenda and provide transparency, an accurate assessment of baseline conditions to compare future monitoring data against, an outline of the thresholds at which management actions should be taken to promote certainty and assist with judicial enforcement, and is linked to response action.

Learning as we go and making appropriate adjustments may be justified in some contexts, and even essential when we do not have the luxury of time and must move ahead without critical information. Adaptive management can increase an agency’s ability to make decisions and allow managers to experiment, learn, and adjust based on data. But adaptive management’s flexibility comes at the cost of more resources and less certainty, which may also invite controversy. The sweet spot for adaptive management may be when managing a dynamic system for which uncertainty and controllability are high and risk is low. While uncertainties are proliferating, situations that meet those conditions are not the norm.

It would be beneficial for our environmental governance systems to explicitly identify conditions under which adaptive management may and may not be used, and to provide clear accountability mechanisms. The approach must fit with the practical realities of the working environment. For example, even if uncertainty and controllability are high and risk is relatively low, tinkering with large-scale energy infrastructure is not practical. Adaptive management may not be suited to regulatory contexts (1) in which long-term stability of decisions is important; (2) where decisions simply can’t easily be adjusted once implemented; or (3) where it is essential that an agency retain firm authority to say “yes” or “no” and leave it at that. It is a valuable tool to be invoked when truly necessary.

The interconnectedness of today’s global environmental challenges is in tension with the accreted framework of media-specific, site-specific laws and siloed agencies. Adjustments that help to align objectives, processes, and structures could scale impact.

Our framework should reflect commitment to and investment in gathering and analyzing information, from intricate science to the concerns of impacted communities; and be designed to incorporate and respond to changing information, such as through judicial review or other checks.

In part because of impacts already set in motion, we must consider when we cannot wait for more information before taking action on environmental and climate challenges. By their nature, some of those actions can be adapted on an ongoing basis, while others cannot. Clear parameters for differentiating will help ensure clear timelines and appropriate, effective processes.

Building a Structure Fit for Purpose

The triple planetary crises, a term coined by the UN Environment Programme, refers to the challenges of biodiversity loss, pollution overload, and climate change. They require large-scale mobilization and societal level adjustments. This magnitude of action requires a multifaceted system that can support and move myriad levers in a coordinated and balanced manner. The year she received the Nobel Prize in Economics, Elinor Ostrom published a paper capturing the tension but also necessity of this layered system, calling for a “polycentric approach” to addressing climate change.

The following discussion focuses largely on federal and state government action. In addition, Tribal Nations are vital sovereign authorities, partners, and voices in governance, including natural resource management, and their needs and knowledge are critical to effective, sustainable, just results. And as Ostrom recognized, private entities will also be instrumental in addressing climate change and other complex challenges; this includes not only corporations, as discussed below, but philanthropic organizations and a variety of other nongovernmental actors.

The Scale Challenge

Environmental regulation occurs at multiple levels: local ordinances, state laws and policies, interstate agreements, tribal laws, federal regulations, and international laws and norms. It also works at different resource scales, from managing a subspecies to protecting regional drinking water to setting nationwide air standards.

Jurisdictional nesting can provide comparative benefits at various levels for specific resources or pollutants. For example, working at the local level may allow for tailoring to specific circumstances to maximize benefits and the building of trust, while working at the state level can allow for the cumulative benefits of collective local action while also allowing for the testing of different approaches to federal implementation. Meanwhile, working at the federal and larger scale allows, among other things, the balancing of voices, and the establishment of shared objectives, standards, or requirements.

However, tiered systems can also be subject to gaps in implementation, such as when there is no mechanism to trigger enforcement of an international mandate at a national level. This may inadvertently impede interoperability and shared learning, such as by using different data standards, tools, or systems, and slow action due to competing or otherwise unaligned priorities. In addition, rarely do jurisdictional boundaries align with resource definitions, whether it be a hydrogeographic basin, extent of an air pollutant, or natural hazard vulnerability zone. Further complexity is added by questions around preemption, with changes occurring in longstanding understandings of federal versus state authorities under key statutes and regulatory structures.

Federal, tribal, state, and local governments must navigate these challenging dynamics as they work to effectively implement existing environmental laws and creatively address new environmental problems.

Cooperative Federalism

Federalism—whereby the federal government and states share power and responsibilities—is a central tenet of the U.S. governance system. A particular form, cooperative federalism, is embodied in most of the major U.S. environmental laws, including the Clean Air Act and the Clean Water Act. These laws establish a legal framework in which minimum standards are established at the federal level and individual states implement the programs. Today, over 90 percent of the delegable federal environmental programs are run by states. As a general matter, states are responsible for ensuring that federal standards are met but have the flexibility to impose standards that are more stringent than the federal standards.

In practice, the Congressional Research Service observes that the “precise relationship and balance of power between federal and state authorities in cooperative federalism systems is the subject of debate.” This debate has manifested in a variety of ways over the decades, including differences over the appropriate scope of federal oversight and levels of federal funding for state-delegated programs.

Environmental protection has advanced in many respects over time with cooperative federalism as its foundation, but few would argue there is no room for improvement. For example, a 2018 memorandum by the Environmental Council of the States (ECOS) captured a consensus among states that the “current relationship between U.S. EPA and state environmental agencies doesn’t consistently and effectively engage nor fully leverage the capacity and expertise of the implementing state environmental agencies or the U.S. EPA.”

In addition to the leeway that cooperative federalism provides to the states in implementing federal environmental laws, states are free to regulate or otherwise address environmental problems that are not covered by federal laws. As a result, states are often referred to as (in Justice Brandeis’ phrase) “laboratories of democracy” for testing innovative policies. Historically, states have served as testing grounds for environmental policies later adopted by the federal government. Given the current federal governance landscape, discussed below, what happens in the states may stay in the states (at least for quite some time)—making state laboratories one of the few promising options for advancing environmental protection.

Barriers to Optimal Functioning of Cooperative Federalism

In addition to the inherent systemic challenges outlined above with respect to multi-tiered jurisdiction and resource scale, there are broad societal barriers to maximizing the efficacy of cooperative federalism. The numerous overarching problems contributing to democratic dysfunction (e.g., channelized communication, primaries that yield extreme candidates who foster dramatic pendulum swings, lack of public trust) will contribute to impeding the optimal functioning of cooperative federalism for the foreseeable future.

The multitude of environmental governance-specific challenges identified earlier also significantly affect the functioning of cooperative federalism. These include, for example, long-standing congressional gridlock; new and emerging environmental harms that cannot be easily addressed within the existing, siloed framework; a Supreme Court changing its review of regulation; and regulatory pendulum swings that make consistency and stability difficult and hinder continuous improvement.

In addition, several additional barriers arguably weaken the foundations of cooperative federalism. These include: ineffective federal oversight of state programs (possibly both too stringent and too lenient in some respects); insufficient collection and dissemination of data (e.g., on environmental conditions, performance, pollution impacts), as well as inconsistent tracking of key environmental indicators; lack of state-specific effective risk communication and messaging; limited state resources for filling federal regulatory gaps or experimenting with innovative ways of implementing federal and state regulations; and insufficient federal funding for state programs. Recent critiques also point to the need to build out state administrative law to improve the functioning of cooperative federalism.

Opportunities for Renewing Cooperative Federalism

Recent developments in federal programs are disrupting many aspects of the country’s environmental protection efforts. These developments include drastic regulatory rollbacks, multiplied industry influence, curtailed input from scientists and other experts, rollback of federal grant funds to states and local governments, and sweeping staffing cuts resulting in loss of critical expertise.

Cooperative federalism has been particularly undermined by federal funding cuts (e.g., withdrawal of federal grants, reductions in revolving loan funds) and cuts to the federal programs that collect and analyze environmental data. Moreover, federal interference with independent or “more stringent than” state initiatives is taking a toll (e.g., response to California’s electric vehicle requirements ).

Given the barriers outlined above that make major statutory change infeasible, building an entirely new structure to replace cooperative federalism will be a nonstarter for the foreseeable future. However, ample opportunities exist to strengthen the existing structure in a manner that yields more effective and innovative approaches to environmental protection.

Front and center is building state and local governmental capacity to fill the gaps created by federal inaction and rollbacks as well as to lead on regulatory innovation. In so doing, states and local governments can serve as more effective laboratories of democracy and foster innovative federal action. And because states and local governments are on the frontlines of managing environmental and climate impacts such as floods and wildfires, as well as aging water infrastructure and other environment-related challenges, they are motivated to address the cause and effects of these harms, despite the intensely politicized nature of environmental issues such as climate change.

To be sure, renewing the existing structure is complicated by an uneven political landscape. For example, the level of political and popular support for environmental protection measures in the 26 states led by Republican governors differs from the levels of support in the 24 states led by Democratic governors, and the relative dominance of a particular party (e.g., trifectas or triplexes) is also a factor. These dynamics likewise influence environmental action by local governments when, for example, the potential for state preemption of local authority is a factor.

Nevertheless, the practical reality of increased extreme weather events, aging water infrastructure, and other environment-related challenges provides a strong incentive for all states and local governments to act. State and local efforts, however, are hindered by limited capacity in the form of staffing, funding, expertise, data, and other factors. For example, virtually all states could benefit in their decisionmaking from more robust data on local environmental conditions, and many states lack adequate funding, staff, and other resources.

Private Sector Synergies and Opportunities

Private environmental governance (PEG)—which can take a range of forms including collective standard-setting, certification and labeling systems, corporate carbon commitments, investor and lender initiatives, and supply chain requirements—is already making its mark across industries as diverse as electronics, forestry, apparel, and AI. For example, roughly 20 percent of the fish caught for human consumption worldwide and 15 percent of all temperate forests are subject to private certification standards. In addition, 80 percent of the largest companies in key sectors impose environmental supply chain contract requirements on their suppliers. And investors are increasingly taking environmental, social, and governance (ESG) into account, including risks related to climate change. A 2022 study estimated, for example, that assets invested in U.S. ESG products could double from 2021 to 2026 and reach $10.5 trillion.

As professors Vandenbergh, Light, and Salzman explain in their book Private Environmental Governance: “If you want to understand the future of environmental policy in the 21st century, you need to understand the actors, strategies, and challenges central to private environmental governance.”

Given the scope of PEG activities, it is not surprising that a range of regulatory regimes are implicated, including corporate governance, contract, antitrust, and consumer protection laws. In some cases, these legal regimes place constraints on the forms and scope of PEG initiatives. Many contend, however, that these constraints are inadequate, as reflected in recent efforts to severely curtail ESG initiatives.

Further, some scholars and advocates have criticized PEG from an entirely different perspective, citing concerns that PEG measures constitute greenwashing—that is, that they do not actually change corporate behavior and environmental conditions. Among other concerns is that PEG may undermine support for public governance measures in certain contexts.

Yet federal legislative gridlock, a dramatically swinging environmental regulatory pendulum, unregulated new technologies, and other factors point to needing a better understanding of how PEG can be leveraged to advance environmental protection efforts—including the improved functioning of cooperative federalism.

How can we use innovative approaches for preserving existing data and collecting new data on environmental conditions, regulated entity performance, and pollution impacts to enhance interoperability of local, state, and federal systems, foster consistency among assessments of risk, and help align priorities and approaches?

Problems such as climate change require a whole of government approach to address and could benefit from leveraging adjacent state and local regulatory authorities in areas such as land use (e.g., zoning), infrastructure, and public health.

Bolstering state and local officials’ networks for sharing data, best practices, and regulatory innovations may help align priorities and produce further progress on cross-jurisdictional problems as well as new challenges such as permitting reforms.

For example, asking—what are the effects of PEG (e.g., emissions reductions); what are the drivers of PEG (e.g., brand reputation, shareholder actions, employees, and corporate customers); are there ways to reduce greenwashing and greenhushing; and how can we ensure that PEG complements public governance.

For example, AI and advanced monitoring technologies—if thoughtfully leveraged—could lessen the burden on state and local governments, particularly those that are under-resourced, in their efforts to assess climate risk, develop resilience plans, and monitor regulatory compliance.

Conclusion

The environmental gains of the last half-century demonstrate that governance choices matter. The United States built a system capable of addressing the urgent environmental crises of its time by combining scientific expertise, democratic accountability, and enforceable legal standards.

Today’s urgent challenges—climate change, biodiversity loss, and pervasive pollution—demand a similar alignment under far more complex conditions. The challenge is not merely to regulate more, faster, or differently, but to recommit to decisionmaking that is credible and durable: by restoring confidence that evidence matters, that participation is meaningful, that tradeoffs get confronted honestly, and that rules will persist long enough to justify investment and collective effort.

The path forward lies neither in abandoning the foundations of environmental law, nor in relying solely on technological or private solutions. It will be found by strengthening and adapting existing governance structures—integrating cross-cutting objectives across domains, clarifying roles across jurisdictions, and rebuilding the shared evidentiary base and institutional capacity needed to act amid uncertainty, rather than deferring action in pursuit of unattainable certainty. And it requires clear communication about today’s complex, dispersed challenges that enhances understanding and reduces polarization.

At its core, the triple planetary crisis is a democratic and governance challenge: how societies decide, together, to protect people and places while sharing costs and benefits fairly. Meeting that challenge will require systems capable of carrying both technical complexity and public trust, as well as a sustained commitment to invest in institutions that can decide, act, and endure.

Costs Come First in a Reset Climate Agenda

Durable and legitimate climate action requires a government capable of clearly weighting, explaining, and managing cost tradeoffs to the widest away of audiences, which in turn requires strong technocratic competency.

Democratic governance needs

- Clear articulation of tradeoffs in policy design, including who pays, who benefits (and when), and why.

- Think bigger and wider in building durable coalitions for climate action, mobilizing dispersed beneficiaries and taking advantage of policy Overton windows that cut across partisan lines.

State Capacity needs

- Intergovernmental delivery muscle and partnering capacity to enable state and local actors.

- Invest in technocratic state capacity where the big wins live, like permitting and siting, interconnection and transmission, or power-market governance, and implementation capacity to limit bottleneck-driven policy failures.

- Institutionalize rigorous ex ante and regular cost benefit analysis to guide design and mid-course corrections.

Key Takeaways

- The costs of climate policy influence whether reforms benefit society, as well as their likelihood of passage and durability. Four ways to categorize climate policy costs are: negative-cost policies (pro-growth policies with climate co-benefits); low-cost policies (costs below domestic climate benefits); medium-cost policies (costs below global climate benefits); and high-cost policies (costs above global climate benefits). Cross-partisan alignment is most evident among pro-abundance progressives and pro-market conservatives.

- Negative- and low-cost policies align with domestic self-interest and comprise a growing share of the abatement curve. For example, market liberalization in permitting, siting, electricity regulation, and certain transportation applications lower energy costs and have profound emissions benefits. A prominent low-cost policy is emissions transparency. Negative- and low-cost policies hold the most potential for durable reforms and are often technocratic in nature.

- Chronic underconsideration of costs has induced an overselection of high-cost policies and underpursuit of low- and negative-cost policies. Legislative policies, such as subsidies and fuel mandates or bans, often receive no ex ante cost-benefit analysis before adoption. Interventions receiving cost-benefit analysis, especially regulation, tend to underestimate costs.

- Innovation policy – namely public support for research, development, and early-stage deployment – can align with domestic self-interest and address legitimate market deficiencies. By contrast, industrial policy for mature technology carries high costs, often erodes social welfare, and is not politically durable. Notably, public support for mature technologies in the Inflation Reduction Act was not durable, but support remained for nascent industry.

- We recommend that a reset climate agenda focus on abatement results over symbolic outcomes, prioritize state capacity for technocratic institutions, and emphasize cost considerations in policy formulation and maintenance. Negative cost policies warrant prioritization, with an emphasis on mobilizing beneficiaries like consumer, non-incumbent supplier, and taxpayer groups to overcome the lobbying clout of entrenched interests. Robust benefit-cost analysis should precede any cost-additive policies and be periodically reconducted to guide adjustments.

Introduction

Public policy involves tradeoffs. The primary tradeoff for climate change mitigation is economic cost. Secondary tradeoffs include commercial freedom, consumer choice, and the quality or reliability of goods and services. Political movements seeking to address a collective action problem, such as climate change, are prone to overlook the consequences of tradeoffs on other parties, like consumers and taxpayers. This paper posits that the cost tradeoffs of climate change mitigation have been underappreciated in the formation of public policy. This has resulted in an overselection of high cost policies that are not politically durable and may erode social welfare. It also results in overlooking low or negative-cost policies that are durable and hold deep abatement potential. These policies can have broad political appeal because they align with the self-interest of the United States, however they typically require dispersed beneficiaries to overcome the concentrated lobby of entrenched interests.

A core, normative objective of public policy is to improve social welfare, which “encourages broadminded attentiveness to all positive and negative effects of policy choices”. Environmental economics determines the welfare effects of climate change mitigation policy by the net of its abatement benefits less the costs. The conventional technique to determine abatement benefits is the social cost of carbon (SCC). The barometer for whether climate policy benefits society is to determine whether abatement benefits exceed costs. Accounting for full social welfare effects requires consideration of co-benefits as well, granted these tend to be conventional air emissions with existing mitigation mechanisms covered under the Clean Air Act. Nevertheless, accounting for costs is essential to ensure climate policy benefits society.

Abatement costs also have a discernable bearing on the likelihood and durability of policy reforms. Climate policies exhibit patterns of passage, mid-course adjustments, and political resilience across election cycles based on the constituency support levels linked to benefit-allocation and cost imposition. This paper develops four policy classifications as a function of their abatement benefit-cost profile, and uses this framework to examine the political economy, abatement effectiveness, and economic performance of select past and potential policy instruments.

Political Economy and Policy Taxonomy

The translation of climate policy concepts into legitimate policy options in the eyes of policymakers can be viewed through the Overton Window. That is, politicians tend to support policies when they do not unduly risk their electoral support. The Overton Window for climate policy is constantly shifting within and across political movements with the foremost factor being cost.

In a 2024 survey of voters, the most valued characteristics of energy consumption were 37% for energy cost, 36% for power availability, 19% for climate effect, 6% for U.S. energy security effect, and 1% for something else. Democrats slightly valued energy cost and power availability more than climate effects. Independents and Republicans heavily valued energy cost and power availability more than climate effect.

Progressives have long exhibited greater prioritization of climate change policy, but cost concerns are driving an overhaul of the progressive Overton Window on climate change. In California, which contains perhaps the most climate-concerned electorate in the U.S., progressives have begun a “climate retreat” to recalibrate policy as “[e]lected officials are warning that ambitious laws and mandates are driving up the state’s onerous cost of living”. Nationally, a new progressive thought leadership think tank is encouraging Democrats to downplay climate change for electoral benefit. Importantly, they find that 61% of battleground voters acknowledge that “climate change is at least a very serious problem,” but that “it is far less important than issues like affordability.”

Similarly, veteran progressive thought leaders, such as the Progressive Policy Institute, now stress that “energy costs come first” in a new approach to environmental justice. While emphasising the continued importance of GHG emissions reductions, those policy leaders are making energy affordability the top priority, amid a broader Democratic messaging pivot from climate to the “cheap energy” agenda. The rise of cost-conscious progressives is particularly notable because the progressive electorate has expressed a higher willingness to pay to mitigate climate change than moderate and conservative electoral segments.

Economic tradeoffs, namely costs and more government control, has long been the central concern on climate policy for the conservative movement. The conventional climate movement messaged on fear and the need for economic sacrifice, which is the antithesis of the conservative electoral mantra: economic opportunity. Yet the conservative climate Overton Window emerged with a series of state and federal policy reforms when climate change mitigation aligned with expanded economic opportunity. However, pro-climate conservative thought leaders remain opposed to high cost policies, such as calling to phase out Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) subsidies for mature technologies.

Many leading conservative thought leaders continue to challenge the climate agenda writ large because of its association with high cost policies. For example, President Trump’s 2025 Climate Working Group report was expressly motivated by concerns over “access to reliable, affordable energy” while acknowledging that climate change is a real challenge. Similarly, a 2025 American Enterprise Institute report finds that the public is most interested in energy cost and reliability and unwilling to sacrifice much financially to address climate change. Meanwhile, climate-conscious conservative thought leaders like the Conservative Coalition for Climate Solutions and the R Street Institute continue to emphasize a market-driven, innovation-focused policy agenda that prioritizes American economic interests and drives a cleaner, more prosperous future. Altogether, it indicates a conservative Overton Window on negative and low-cost climate change mitigation.

While cost is driving the Overton Window within each political movement, it also buoys the potential for alignment across political movements. Political movements are not monoliths, but rather exhibit major subsets within each movement. The progressive movement has seen gains in popularity among its populist left flank, often identified as the “democratic socialist” wing, which contributes to ongoing debate about Democrats’ ideological direction. Climate policy initiated by this wing, however, is associated with high economic tradeoffs (e.g., degrowth) and has prompted a backlash within the progressive movement. By contrast, a subset of the progressive movement, sometimes labelled “abundance progressives,” has emerged to support a more pro-market, pro-development posture. This movement is especially responsive to energy cost concerns, and is an emerging substitute for the anti-development traditions of the progressive environmental movement. Overall, variances in the progressive movement are fairly straightforward to categorize linearly on the economic policy spectrum.

The Republican electorate views capitalism far more favorably than Democrats, but with modest decline in recent years. Republicans have trended away from consistently conservative positions associated with limited government, which historically emphasized the rule of law and a strict cost-benefit justification for government intervention in the market economy. They have migrated towards right-wing populism associated with the Make America Great Again (MAGA) movement. Right-wing populism is hard to operationalize for economic policy because it is not a standalone ideology, but a movement vaguely attached to conservative ideology. Generally, the “America First” orientation of MAGA implies positions based on the self-interest of the U.S., with the Trump administration prioritizing cost reductions in energy policy.

MAGA is further to the right of conventional conservatives on environmental regulation and general government reform. For example, conservatives have noted the contrast between conservative “limited, effective government” and the Department of Government Efficiency’s “gutted, ineffective government” reform approach. On the other hand, MAGA will occasionally back leftist policy instruments, such as coal subsidies, wind restrictions, executive orders to override state policies, and emergency authorities for fossil power plants. These are often justified to counteract the leftist policies passed by progressives (e.g., renewables subsidies, fossil restrictions, emergency authorities for renewables), resulting in dueling versions of industrial policy. In other words, ostensible overlap between MAGA and progressives on policy instrument choice actually reflects the use of similar tools used for conflicting purposes (e.g., restrictive permitting or subsidies for opposing resources; i.e. picking different “winners and losers”). Nevertheless, the disciplinary agent for right-wing energy populism has been cost concerns, which have influenced the Trump administration to pursue more traditionally conservative energy policies like permitting reform and lowering electric transmission costs.

This political economy identifies the broadest cross-movement Overton Window between moderate or “abundance progressives” and traditional conservatives. Regardless, both broad movements exhibit cost sensitivity and growing prioritization of U.S. self–interest. Distinguishing the domestic SCC from global SCC is essential to determine what policies are consistent with the self-interest of the U.S. versus the world as a whole. Traditionally, the U.S. government only considers domestic effects in cost-benefit analysis, yet the vast majority of domestic climate change abatement benefits accrue globally.

The first SCC, developed under the Obama administration, relied solely on a global SCC. Leading conservative scholars, including the former regulatory leads for President George W. Bush, criticized the use of the global SCC only to set federal regulations. They argued for a “domestic duty” to refocus regulatory analysis on domestic costs and benefits. Similarly, the first Trump administration used a domestic SCC. Although the second Trump administration moved to discard the SCC outright, this appears to be part of a regulatory containment strategy, not a reflection of the conservative movement’s dismissal of the negative effects of climate change. In other words, even if the SCC is not the explicit basis for policymaking, it is a useful heuristic for policymakers.

The proper value of the SCC is the subject of intense scholarly and political debate. It has fluctuated between $42/ton under President Obama, $1-$8/ton under President Trump, and $190/ton under the Biden administration (all values for 2020). The main methodological disagreement has been over whether to use a domestic or global SCC, with the Trump administration position guided by “domestic self-interest.” This suggests the original domestic and global SCC values may approximate the Overton Window parameters the best. This underscores the following policy taxonomy that characterizes climate abatement policies by cost relative to domestic and global SCC levels:

- Class I policy: negative abatement costs. Such policies are widely viewed as “no regrets” by scholars and political actors across the spectrum because they constitute sound economic policy that happens to carry climate co-benefits. The Overton Window is most robust for Class I policy. It typically takes the form of fixing government failure, such as permitting reform.

- Class II policy: positive abatement costs below the domestic SCC. These low-cost policies often fall within the Overton Window, because they advance U.S. self-interest (i.e., positive domestic net benefits). Class II policies have a small abatement cost range (e.g., up to $8/ton). One estimate puts them at 4-14 times smaller than the global SCC.

- Class III policy: abatement costs between the domestic SCC and global SCC. These medium-cost policies improve global social welfare, but are not in the self-interest of the U.S., excluding co-benefits. Most cost-additive policies that pass a global SCC test fall in this range, underscoring why climate change is an especially challenging strategic problem; those incurring abatement costs do not accrue most abatement benefits. Class III policies face inconsistent domestic support and often require international reciprocation to be in the self-interest of the U.S.

- Class IV policy: abatement costs exceeding the global SCC. These high-cost policies fail a climate-only cost-benefit test. In other words, Class IV policies erode social welfare, excluding co-benefits. Class IV policies may be effective at reducing emissions, but often leave society worse off. Class IV policies are challenging to pass and are hardest to sustain.

Policy Applications

There are myriad policies across the abatement cost spectrum. This analysis applies to particularly popular domestic policies already pursued or readily considered. This includes policies targeting the environmental market failure via direct abatement (GHG regulation) and indirect abatement (public spending, clean technology mandates, and fuel bans). It also includes policies targeting non-climate market failure, yet hold deep climate co-benefits (innovation policy). The analysis also examines policies that correct government failure and have major climate co-benefits (permitting, siting, and electric regulation reform).

Fuel Mandates and Bans

For the last two decades, the most prevalent climate policy type in the U.S. has been state level fuel mandates and bans. Last decade, the environmental movement came to prefer policies that explicitly promote or remove fuels or technologies, not emissions. This is despite ample evidence in the economics literature that market-based policies are more effective and carry far lower abatement costs. Nevertheless, the most common domestic climate policy instrument this century has been state renewable portfolio standards (RPS). The literature notes several key findings from RPS:

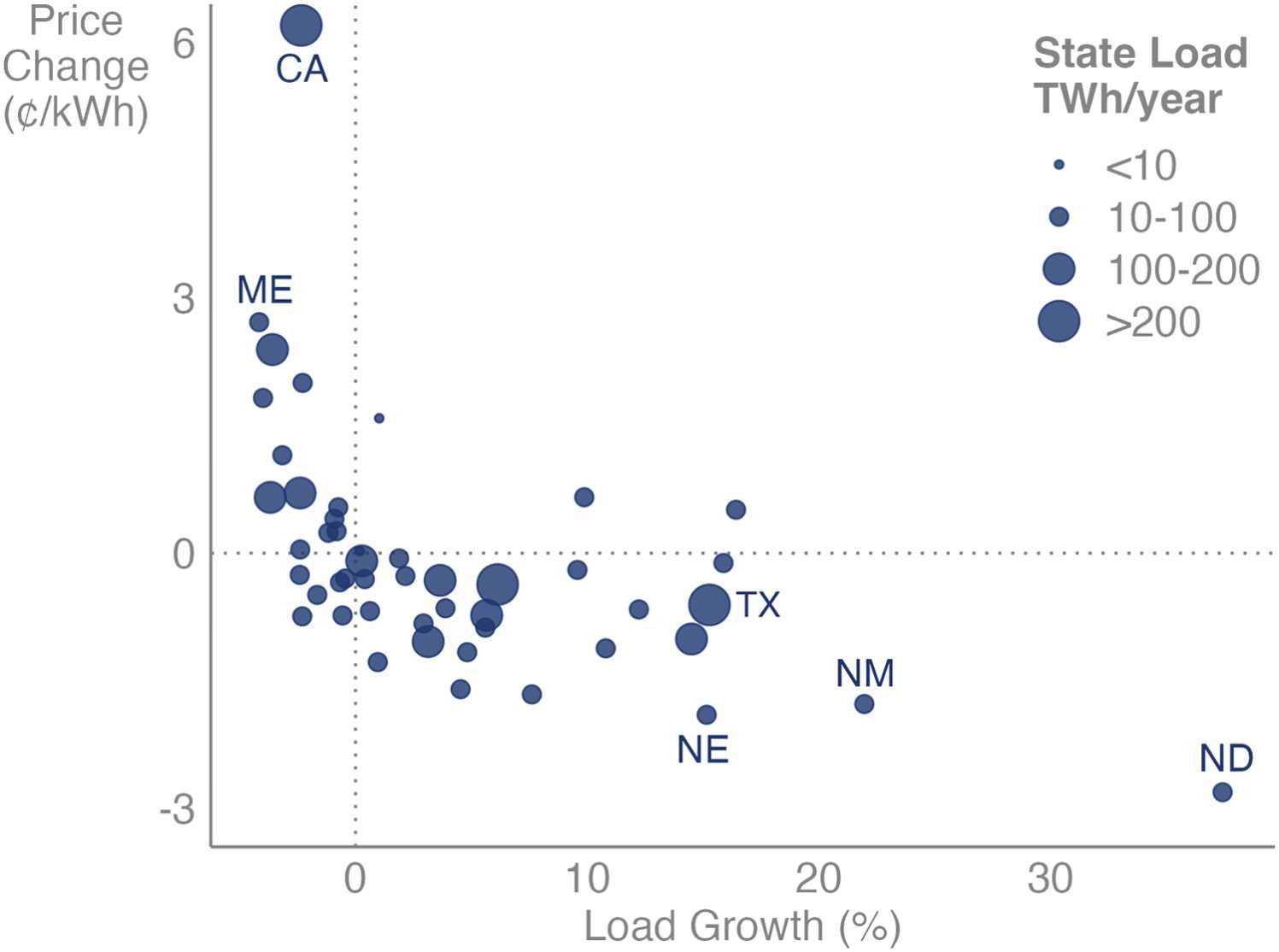

- RPS has substantial but diminishing abatement efficacy. RPS compliance drove the bulk of initial renewables deployment, but declined to 35% of U.S. renewables capacity additions in 2023. This reflects the improved economics of renewable energy, which went from an infant industry in the 2000s to a mature technology and the preferred choice of voluntary markets by the 2020s. Renewables also exhibit declining marginal abatement as penetration levels grow. This underscores the environmental underperformance of policies promoting fuel, not emissions reductions.

- Binding RPS increases costs, with large state variances based on target stringency and carveouts. RPS compliance costs average 4% of retail electricity bills in RPS states and reach 11-12% of retail bills in states with solar carve-outs. Stringency is a key factor, as some RPS are not binding due to strong market forces, whereas binding RPS increases costs. Abatement cost estimates of RPS vary widely, with one prominent study placing compliance with RPS from 1990-2015 at $60-$200/ton. Within the Mid-Atlantic region alone, implied states’ RPS compliance costs in 2025 ranged from $11/tonne to $66/tonne, with solar carveout compliance clocking in at $70/tonne to $831/tonne. The future abatement cost of renewables integration is highly sensitive to RPS stringency and technology cost assumptions, with one estimate of implied abatement costs ranging from zero (nonbinding) to $63/tonne at 90% requirement in 2050. This evidence qualifies RPS as a class II to class IV policy, depending on its design.

- States with stringent RPS face challenging compliance targets, prompting calls for reforms to mitigate cost. Compliance with interim targets has generally been strong but stringent RPS states are beginning to fall behind on their targets. For example, renewable energy credit (REC) costs are nearing alternative compliance payment levels. To reduce costs, popular reform ideas have included delaying compliance timelines, adopting a clean energy standard to capture broader resource eligibility, or making RECs emissions weighted.

- Modest RPS exists in some conservative states but aggressive RPS policy has, generally, only proven popular in progressive states. As of late 2024, 15 states plus the District of Columbia had RPS targets of at least 50% retail sales, and four have 100% RPS. Sixteen (16) states have adopted a broader 100% clean electricity standard, though the broad definition of clean energy dilutes expected abatement performance in some states. Overall, renewable or clean portfolio standards do not appear to hold broad Overton Window alignment potential beyond modest applications.

Micro-mandates have also sprung up, primarily in progressive states. These have often targeted the promotion of nascent or symbolic energy sources that the market would not otherwise provide, with the costs obscured from public view (e.g., rolled into non-bypassable electric customer charges). A good example is offshore wind requirements in the Northeast, which carries a high abatement cost (over $100/ton).

Fuel bans have become increasingly popular climate policy in progressive states and municipalities. Beginning in 2016, a handful of progressive states began banning coal. However, this does not appear to have created much cost or abatement benefit, as evidenced by a lack of commercial interest in coal expansion in areas without such restrictions. In fact, neither federal nor state regulation was responsible for steep emissions declines from coal retirements. Coal retirements were mostly driven by market forces, especially breakthroughs in low-cost natural gas production and high efficiency power plants. Policy factors, like the Mercury and Air Toxics Rule, were secondary drivers of coal plant retirement.

Around 2020, California, New York, and most New England states began adopting partial natural gas bans or de facto bans on new gas infrastructure through highly restrictive permitting and siting practices. Unlike coal restrictions, these laws have markedly decreased commercial activity, namely gas pipeline and power plant development, and in some cases caused economically premature retirements. This has caused “pronounced economic costs and reliability risk.” Resulting pipeline constraints drive steep gas price premiums in these states, which translate into a core driver of elevated electricity prices.

Insufficient pipeline service in the Northeast is especially problematic, as demonstrated by a December 2022 winter storm event that nearly led to an unprecedented loss of the Con Edison gas system in New York City that would have taken weeks or months to restore. Further, preventing gas infrastructure development does not provide a clear abatement benefit, because more infrastructure is needed to meet peak conditions even if gas burn declines. A prominent study found a 130 gigawatt increase in gas generation capacity by 2050 was compatible with a 95% decarbonization scenario.

Progressive states and municipalities have also pursued natural gas consumption bans. This policy may carry exceptional cost, especially for existing buildings, with potentially well over $1 trillion in investment cost to replace gas with electric infrastructure. One estimate put the cost of natural gas bans at over $25,600 per New York City household. A Stanford study projected a 56% electric residential rate increase in California from a natural gas appliance ban. Generally, conservative thought leaders and elected officials have opposed natural gas bans for cost as well as non-pecuniary reasons, including security concerns and the erosion of consumer choice. This applies even for prominent members of the Conservative Climate Caucus. Altogether, gas bans are considered class IV policy with virtually no Overton Window alignment.

GHG Transparency

GHG regulation takes various forms. The least stringent is GHG transparency, which addresses an information deficiency and lowers transaction costs in voluntary markets. This begins with reporting and accounting requirements on emitters (Scope 1 emissions). Public policy can help resolve measurement and verification problems that have eroded confidence in voluntary carbon markets. GHG transparency policy can also standardize terminology and provide indirect emissions platforms. For example, making locational marginal emissions rates on power systems publicly available lets market participants identify the indirect power emissions of power consumption (Scope 2 emissions). Progressives have consistently favored GHG transparency policy, while conservatives have typically supported light-touch versions of it like the Growing Climate Solutions Act.

The second Trump administration recently pursued removal of basic GHG reporting requirements on ideological grounds, specifically repeal of the GHG Reporting Program (GHGRP). This appears to reflect an optical deregulatory agenda over an effective one. Conservative groups have warned of the downsides of GHGRP repeal. Pressure to course correct may prove fruitful, given that the industry the Trump administration aims to assist – oil and natural gas – maintain that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) should retain the GHGRP. A recent analysis found that if states replace the GHGRP, new programs will be more expensive (Figure 2).

Many regulated industry and conservative groups instead support a low compliance cost GHG reporting regime with durability across future administrations. This not only applies to direct emissions reporting but indirect emissions reporting, as in the absence of federal policy industry faces a patchwork of compliance requirements across states and foreign governments. The same economic self-interest rationale justifies a role for limited government in emissions accounting, with an emphasis on the capital market appeal of showcasing the “carbon advantage” of the U.S. in emissions-intensive industries. An example is liquified natural gas, whose export market is enhanced by showcasing its lifecycle emissions advantage over foreign gas and coal.

The abatement effectiveness of GHG transparency has grown appreciably in the 2020s, as voluntary industry initiatives have sharply increased. This policy set enables an efficient “greening of the invisible hand” with staying power, as corporate environmental sustainability efforts appear resilient regardless of political sentiment, unlike corporate social endeavors. In fact, the aggregate willingness to pay for voluntary abatement from producers, consumers, and investors suggests that well-informed domestic markets go a long way towards self-correcting the externality of GHGs (e.g., convergence of the private and social cost curves). Certain voluntary corporate behaviors may even exceed the global SCC, especially commitments to nuclear, carbon capture, and other higher cost abatement generation financed by the largest sources of power demand growth. Well-functioning voluntary carbon markets could yield roughly one billion metric tons of domestic carbon dioxide abatement by 2030. Providing locational marginal emissions data can slash abatement costs from $19-$47/ton down to $8-$9/ton while doubling abatement levels from some power generation sources.

Overall, efficient GHG transparency policy described above is a low-cost mitigation strategy consistent with class II designation. Basic, federal GHG transparency policy may even constitute class I policy, because it avoids the higher compliance cost alternative of a patchwork of state and international standards that would manifest in the absence of federal policy. However, stringent GHG transparency policy may constitute class III or IV policy. Prominent examples include a recent California climate disclosure law and a former Securities and Exchange Commission proposed rule to require emissions disclosure related to assets a firm does not own or control (Scope 3). Such efforts may obfuscate material information on climate-related risk and worsen private-sector led emission mitigation efforts.

Direct GHG Regulation

Classic environmental regulation takes the form of a command-and-control approach. These instruments include applying emissions performance standards or technology-forcing mechanisms, typically for power plants or mobile sources. These policies vary widely in stringency and cost. Overall, command-and-control is widely considered in the economics literature to be an unnecessarily costly approach to reducing GHGs relative to market-based alternatives. It can also result in freezing innovation, by discouraging adoption of new technologies.

Federal command-and-control GHG programs have not been particularly environmentally effective, cost-effective, or demonstrated legal or political durability. The first power plant program was the Clean Power Plan, which was struck down in court, and yet its emissions target was achieved a decade early from favorable market forces and subnational climate policy. The most recent federal command-and-control approaches for GHG regulation were 2024 EPA rules for vehicles and power plants. A 2025 review of these and other federal climate regulations over the last two decades of federal climate regulations found:

- EPA’s cost estimates to be “extraordinarily conservative” with suspect methodology that was prone to error and inconsistent with economic theory;