Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

Translating Vision into Action: FAS Commentary on the NSCEB Final Report and the Future of U.S. Biotechnology

Advancing the U.S. leadership in emerging biotechnology is a strategic imperative, one that will shape regional development within the U.S., economic competitiveness abroad, and our national security for decades to come. In the past few years, the contribution of biotechnology to the U.S. economy (referred to as the bioeconomy) has grown significantly, contributing over $210 billion to GDP and creating more than 640,000 domestic jobs, cementing its role as a major and expanding economic force. The impact of biotechnologies and biomanufacturing can be seen across diverse sectors and geographies, with applications spanning agriculture, energy, industrial manufacturing, and health. As biotechnology continues to drive innovation, it is emerging as a core engine of the next industrial revolution.

To maximize the strategic potential of emerging biotechnology, Congress established the bipartisan National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology (NSCEB) through the FY22 National Defense Authorization Act. The commission was tasked with conducting a comprehensive review of how advancements in biotechnology and related technologies will shape the current and future missions of the Department of Defense (DOD), and developing actionable policy recommendations to support the adoption and advancement of biotechnology within DOD and across the federal government. This effort culminated in a report, “Charting the Future of Biotechnology”, delivered to Congress in April 2025. The final report outlines 49 recommendations aimed at accelerating biotechnology innovation and scaling the U.S. biomanufacturing base, reinforcing the bioeconomy as a strategic pillar of national security and economic competitiveness.

In addition to developing a series of recommendations to promote and grow the U.S. bioeconomy, the Commission has also been tasked with facilitating the implementation and adoption of these policy recommendations by Congress and relevant federal agencies. To date, several pieces of legislation have been introduced in both the 118th and 119th Congress that incorporate recommendations from NSCEB’s interim and final reports (Table 1). This Legislation Tracker will be updated as this legislation moves through the process and as new bills are introduced.

The NSCEB report represents a critical policy opportunity for the U.S. bioeconomy. It proposes an injection of $15 billion to support sustained growth in biotechnology innovation and biomanufacturing through strategic investment and improved coordination. This level of investment is significant and would signal congressional support for the bioeconomy that goes beyond that seen in CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022. This much needed infusion of federal investment offers a timely opportunity to build on existing momentum and unlock the next phase of U.S. leadership in the bioeconomy.

The recommendations in the report should be seen as opportunities for engagement with the Commission and with Congress for further refinement of these policy ideas. As the Commission begins its work on implementation, they have called on stakeholders across the bioeconomy to help refine and strengthen its proposals. Responding to this need, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has identified priority areas requiring greater clarity and has issued an open call for supplemental recommendations and policy proposals through the Day One Open Call process.

Overall, FAS supports the Commission’s final report and we applaud the Commission’s efforts to elevate the national conversation around emerging biotechnologies. The report provides a necessary foundation for long-term federal strategy and investment in biotechnology and biomanufacturing. At the same time, there remain clear opportunities to strengthen the recommendations through greater specificity and deeper stakeholder engagement. Two overarching decisions by the Commission deserve some additional scrutiny. First, the report’s adversarial framing towards China, while grounded in strategic reality, risks overlooking opportunities for targeted collaboration that could yield global benefits, particularly in areas where scientific progress depends on multinational cooperation. Second, the final report gives limited attention to the agricultural sector, despite its clear relevance to national security and the DOD’s growing interest in agricultural biotechnology. The “Additional Considerations” section does include a constructive call to modernize the USDA’s BioPreferred Program and update federal classification systems, recommendations that echo those issued by FAS. A more comprehensive approach toward this sector is needed.

The following sections summarize the report’s key pillars and provide analysis, highlighting core recommendations and identifying opportunities where additional detail and stakeholder input, through the Day One Open Call, will be essential for translating the report’s vision into actionable, high-impact policy. Additionally, the Supplementary Recommendations Table for the NSCEB Final Report (Table 2) lists each of the recommendations from the pillars and cross references related proposals from prior FAS work, subject matter experts, and Day One Memos submitted by external stakeholders.

Table 2: Supplementary Recommendations Table for the NSCEB Final Report

Pillar 1. Prioritize Biotechnology at the National Level

Pillar 1 of the report emphasizes the need to prioritize biotechnology at the national level. The recommendations within this pillar are essential for the development of a cohesive national strategy, and we encourage Congress to consider incorporating terminology and drawing on previous policy related to the bioeconomy to ensure that previous progress related to emerging biotechnologies is not lost.

A central recommendation within this Pillar is the establishment of the National Biotechnology Coordination Office (NBCO), which would reduce fragmentation and elevate biotechnology as a national priority. To succeed, the NBCO must address challenges faced by past coordination bodies and be empowered by the administration to drive cross-agency strategy despite differing institutional perspectives. While the presidential appointment of the director could lend authority, it also risks politicization and strategic shifts that may destabilize the sector. Success will depend on clarity of roles, coordination across functions, and strong institutional support for implementation.

FAS provided several additional recommendations and insights on these topics (see Table 2) to make them more nuanced and actionable by Congress, including:

- Coordinating the U.S. Government Approach to the Bioeconomy by Sarah Carter

- A National Bioeconomy Manufacturing and Innovation Initiative by Alexander Titus

Pillar 2. Mobilize the Private Sector to get U.S. Products to Scale

Pillar 2 of the final report focuses on mobilizing the private sector to strengthen biotechnology products by addressing key challenges to the sector, including regulatory reform, financing obstacles, and infrastructure and data needs. While the report correctly identifies long standing regulatory bottlenecks for products of biotechnology under the Coordinated Framework, including unclear oversight and interagency conflicts, it also acknowledges statutory complexities that make reform difficult. Empowering the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) to mediate these disputes is a promising approach, but would require statutory reinforcement. Similarly, proposals to modernize regulatory capacity, such as agency fellowships and regulatory science programs, highlight a critical need for technical expertise within government, though questions remain about institutional placement and long-term sustainability.

On financing and infrastructure, the report points to real gaps in early-stage capital and scale-up capacity, particularly for bridging the “Valley of Death” for biotechnology manufacturing. Concepts like advance market commitments and a new investment fund have potential, but their impact will depend heavily on design, risk management, and alignment with existing capital pipelines. The infrastructure recommendations are strong, but coordination challenges, particularly among national labs, regional hubs, and entities like BioMADE, must be addressed to avoid duplication or underutilization and approaches to securing bioeconomy infrastructure and data are underdeveloped. It will be critical to better define what constitutes critical biotechnology infrastructure and how it should be protected.

FAS provided significant expertise on these topics (see Table 2), such as:

- Coordinating the U.S. Government Approach to the Bioeconomy by Sarah Carter

- Regulations for the Bioeconomy by Sarah Carter

- A National Frontier Tech Public-Private Partnership to Spur Economic Growth by Katie Rae, Orin Hoffman & Michael Kearney

- De-Risking the U.S. Bioeconomy by Establishing Financial Mechanisms to Drive Growth and Innovation by Nazish Jeffery & Zak Weston

- Advancing the U.S. Bioindustrial Production Sector by Michael Fisher

- Closing Critical Gaps from Lab to Market by Phil Weilerstein, Shaheen Mamawala, and Heath Naquin

- Strengthening the U.S. Biomanufacturing Sector Through Standardization by Chris Stowers

- Summary Report – December 7, 2022, Bioeconomy Policy Workshop: Financial and Economic Tools

- Project BOoST: A Biomanufacturing Test Facility Network for Bioprocess Optimization, Scaling, and Training by Ed Charles & Chris Fracchia

One of the NSCEB’s recommendations in particular would benefit from additional input from external subject matter experts to make it more concrete and actionable for Congress:

- Recommendation 2.2d: Congress should improve the effectiveness and reach of the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs to support early-stage innovation. Specifically, stakeholder input on:

- Which areas of biotechnology or sectors within the bioeconomy would most benefit from SBIR and STTR investment?

- How can these programs better support not only early- but also late-stage innovation?

If you have specific policy suggestions related to this topic, we encourage you to submit your ideas through the Day One Open Call page at FAS.

Pillar 3. Maximize the Benefits of Biotechnology for Defense

Pillar 3 of the final report focuses on maximizing the benefits of biotechnology for national defense, with an emphasis on the intelligence community and the Department of Defense (DOD). This pillar includes recommendations related to BioMADE oversight as well as internal workforce education on biotechnology. While oversight of BioMADE is important, it is unclear why additional oversight from Congress is needed for this manufacturing institute above and beyond that provided by its federal sponsor. Additionally, it will be essential for DOD to establish a mechanism for regularly updating workforce education in biotechnology, given the sector’s rapid and continuous evolution.

More broadly, this Pillar appropriately reframes biotechnology as a strategic capability, beyond its traditional role in R&D. This shift in perspective is timely, but realizing the potential of these technologies will require significant institutional change. Ethical use frameworks, particularly around dual-use risks (warfighter enhancement, surveillance, and environmental impact) must be developed through a transparent process that extends beyond DOD to include external stakeholders and independent organizations. In addition, proposed investment and export controls aimed at limiting adversarial advantage must be carefully scoped and implemented. The Department of Commerce (DOC) has published multiple Requests for Information (2018, 2020) to understand and delineate “high-risk” biotech products. Yet, DOC has not added new biotech products to the export list, which highlights the complexity of this task, and underscores the need for precision to avoid stifling beneficial collaboration or disrupting global supply chains.

FAS provided several additional recommendations and insights on these topics (see Table 2) to make them more nuanced and actionable by Congress, including:

- CLimate Improvements through Modern Biotechnology (CLIMB) — A National Center for Bioengineering Solutions to Climate Change and Environmental Challenges by Jennifer Panlilio & Hanny Rivera

- A Foundational Technology Development and Deployment Office to Create Jobs by Katie Rae, Michael Kearney, and Orin Hoffman

Pillar 4. Out-Innovate our Strategic Competitors

Pillar 4 of the NSCEB’s report offers recommendations for strengthening the biotechnology sector to out-innovate global competitors. It focuses on building robust data ecosystems, enhancing biosecurity, and expanding bio R&D infrastructure within the U.S. A central theme is the creation of a modern biological data ecosystem, which would provide the foundational infrastructure necessary to accelerate innovation. While a biological data ecosystem and associated standards are timely, several technical and governance challenges must be addressed, like harmonizing legacy systems, defining AI-readiness, and coordinating cloud lab integration. These complexities present an opportunity for stakeholder engagement and thoughtful design.

Within the Pillar, proposals that call for expanding National Lab capabilities and funding interdisciplinary biotechnology research are directionally strong, but success will depend on interagency coordination and alignment with industry needs. Finally, the report calls for stronger governance of biosafety and biosecurity, though its assertion that past efforts have “failed” could benefit from more nuanced analysis.

While FAS provided expertise on these topics (see Table 2), such as:

- A National Bioeconomy Manufacturing and Innovation Initiative by Alexander Titus

- Kickstarting Collaborative, AI-Ready Datasets in the Life Sciences with Government-funded Projects by Erika DeBenedictis, Ben Andrew, and Pete Kelly

- Creating a National Exposome Project by Gurdane Bhutani, Gary Miller, and Sandeep Patel

- Accelerating Biomanufacturing and Producing Cost-Effective Amino Acids through a Grand Challenge by Allison Berke

- Accelerating Bioindustry Through Research, Innovation, and Translation by Jon Roberts

A few of the report’s recommendations would benefit from additional stakeholder input to enhance clarity and ensure they are actionable for Congress:

- Recommendation 4.1c: Congress should authorize and fund the Department of Interior to create a Sequencing Public Lands Initiative to collect new data from U.S. public lands that researchers can use to drive innovation and Recommendation 4.1d: Congress should authorize the National Science Foundation to establish a network of “cloud labs,” giving researchers state-of-the-art tools to make data generation easier. Specifically, stakeholder input on:

- What type of data should be generated and what types of data generation or collection should be prioritized?

- How can we best draw on or expand existing cloud lab capabilities?

- Recommendation 4.3b: Congress should initiate a grand research challenge focused on making biotechnology predictably engineerable. Specifically, stakeholder input on:

- What specific grand challenge should Congress pursue and how should it be implemented?

- How should the U.S. government engage the scientific community (and others) in establishing and pursuing grand challenges for biotechnology?

- Recommendation 4.4a: Congress must direct the executive branch to advance safe, secure, and responsible biotechnology research and innovation. Specifically, stakeholder input on:

- The report calls for establishment of a body within the U.S. government for this purpose. What should this look like and how would it operate?

If you have specific policy suggestions related to these topics, we encourage you to submit your ideas through the Day One Open Call at FAS.

Pillar 5. Build the Biotechnology Workforce of the Future

Pillar 5 of the final report looks to the future by offering recommendations to secure and build the biotechnology workforce needed in the future. It addresses both the modernization of the federal biotech workforce and the development of the broader U.S. biotech workforce. Modernizing the federal workforce requires more than training programs. It requires coordination across HR systems, consistent standards, and better integration of biotechnology experts into national security and diplomacy. Proposals to expand Congressional science capacity are long overdue and necessary to equip lawmakers to address rapidly evolving biotechnology issues. On the national level, scaling the biomanufacturing workforce will depend on aligning credentials with industry needs and securing input from labor, academia, and employers. Expanding biotechnology education is promising, but successful implementation will require investment in teacher training and curriculum development.

While FAS contributed several recommendations to support this critical capacity-building effort (see Table 2), such as:

- Gathering Industry Perspectives on how the U.S. Government can Support the Bioeconomy by Sarah Carter

- Meeting Biology’s “Sputnik Moment”: A Plan to Position the United States as a World Leader in the Bioeconomy by Natalie Kuldell

One of the NSCEB’s recommendation would benefit from additional stakeholder input to enhance its clarity and make it more actionable for Congress:

- Recommendation 5.2a: Congress must maximize the impact of domestic biomanufacturing workforce training programs. Specifically, stakeholder input on:

- How should the government approach creating competency models for biomanufacturing training and microcredentialing?

- Which specific areas are best suited for microcredentialing efforts?

If you have specific policy suggestions related to these topics, we encourage you to submit your ideas through the Day One Open Call at FAS.

Pillar 6. Mobilize the Collective Strengths of our Allies and Partners

Pillar 6 of the final report focuses on strengthening alliances and partnerships on the global stage to enhance the U.S. biotechnology sector. It highlights the role of the State Department (DOS) in facilitating this effort through development of foreign policy tools, strengthening global data and market infrastructure, and leading in the establishment of international standards within the sector. Elevating biotechnology within U.S. foreign policy is both timely and necessary, particularly as biotech becomes increasingly strategic in areas like health security, climate resilience, and defense. Leveraging existing tools like the International Technology Security and Innovation (ITSI) Fund could provide a solid foundation, but effective execution will require clearer interagency coordination, transparency in funding allocation, and defined metrics for impact, especially across overlapping technology domains.

Proposals to create shared data infrastructure, joint purchasing mechanisms, and international fellowships point to smart long-term strategies for building trust and interoperability with allies. Yet, success hinges on careful coordination, especially around sensitive areas like dual-use biotechnology export controls. If U.S. standards are significantly more restrictive than those of allies, it could create friction and undermine broader goals of international collaboration and leadership.

FAS provided several additional recommendations and insights on these topics (see Table 2) to make them more nuanced and actionable by Congress, including:

- A Matter of Trust: Helping the Bioeconomy Reach Its Full Potential with Translational Governance by Christopher J. Gillespie

- Strategic Investments the U.S. Should Make in the Bioeconomy Right Now by Nazish Jeffery

- Strengthening U.S. Engagement in International Standards Bodies by Natalie Thompson and Mark Montgomery

- What’s Next for the U.S. Bioeconomy? Defining It. by Nazish Jeffery

One particularly important recommendation emphasizes the need to engage the public and build trust in the sector by collecting data on public acceptance. This data can help inform national governance and ensure it is more responsive and translatable to public concerns.

Additional Considerations

The additional considerations section of the NSCEB report brings several key recommendations that do not fit with the rest of the report, though are still very important. Many focus on aligning federal leadership and economic infrastructure with the needs of a growing and strategically vital biotechnology sector. Elevating biotechnology leadership within DOD is a logical step to align R&D with budget authority and operational needs. Similarly, expanding the scope of the Bioenergy Technologies Office (BETO) beyond biofuels and codifying the Office of Critical and Emerging Technology (OCET) role reflects an overdue shift toward recognizing biotech’s relevance to national security and broader innovation policy, though these changes will require institutional buy-in and cultural adjustment. On the economic side, proposals to create a public-private innovation consortium are timely, especially for supporting smaller firms and navigating the convergence of biotechnology with other technologies, like AI. However, care should be taken to not overly narrow the scope at the expense of other critical intersections.

While FAS provided a few recommendations on these topics (see Table 2), such as:

- Summary Report – December 5, 2022, Bioeconomy Policy Workshop: Measurement and Language

- Laying the Groundwork for the Bioeconomy by Sarah Carter

One of the report’s recommendations would benefit from additional stakeholder input to enhance clarity and ensure that it is actionable for Congress:

- Recommendation 8: Congress should direct the National Science Foundation (NSF) to establish a federal grant program for a national system of community biology labs that would engage Americans in informal learning. Specifically, stakeholder input on:

- What is most needed to support community biology labs?

- Should community labs be incorporated within universities or run as independent institutions?

If you have specific policy suggestions related to these topics, we encourage you to submit your ideas through the Day One Open Call at FAS.

Next Steps for the U.S. Bioeconomy

The NSCEB’s final report outlines a vision for a national biotechnology strategy aimed at securing U.S. leadership in a sector that is not only rapidly advancing but also delivering significant economic returns, outpacing even AI. While the report offers thoughtful, well-grounded recommendations that address many of the core challenges facing the U.S. biotechnology landscape, several proposals would benefit from greater specificity and refinement to make them actionable in legislative form. This moment presents a unique opportunity for stakeholders across the biotechnology ecosystem to contribute meaningfully to the development of a national bioeconomy strategy.

The U.S. bioeconomy, which encompasses biotechnology, holds enormous strategic and economic potential. Without a clear, well-implemented plan, the nation risks repeating the mistakes of past industrial shifts, such as the decline in domestic semiconductor leadership. FAS urges Congress to act on the Commission’s recommendations and leverage FAS’ additional proposals to strengthen them further (see Table 2). We also call on the scientific community to provide additional input on these recommendations to ensure they are viable and impactful. If you have actionable policy ideas on how to shape the path forward for the U.S. bioeconomy, we encourage you to submit them through the Day One Open Call. Applicants with compelling ideas will be partnered with our team at FAS to develop their idea into an implementation ready policy memo. Click here to learn more about the Day One Open Call.

FAS Bioeconomy Open Call Areas

- Recommendation 2.2d (SBIR and STTR): Congress should improve the effectiveness and reach of the Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs to support early-stage innovation.

- Which areas of biotechnology or sectors within the bioeconomy would most benefit from SBIR and STTR investment?

- How can these programs better support not only early- but also late-stage innovation?

- Recommendation 4.1c (Bio Data Generation): Congress should authorize and fund the Department of Interior to create a Sequencing Public Lands Initiative to collect new data from U.S. public lands that researchers can use to drive innovation and Recommendation 4.1d: Congress should authorize the National Science Foundation to establish a network of “cloud labs,” giving researchers state-of-the-art tools to make data generation easier.

- What type of data should be generated and what types of data generation or collection should be prioritized?

- How can we best draw on or expand existing cloud lab capabilities?

- Recommendation 4.3b (Predictable BioEngineering): Congress should initiate a grand research challenge focused on making biotechnology predictably engineerable.

- What specific grand challenge should Congress pursue and how should it be implemented?

- How should the U.S. government engage the scientific community (and others) in establishing and pursuing grand challenges for biotechnology?

- Recommendation 4.4a (Safe, Secure, Responsible): Congress must direct the executive branch to advance safe, secure, and responsible biotechnology research and innovation.

- The report calls for establishment of a body within the U.S. government for this purpose. What should this look like and how would it operate?

- Recommendation 5.2a (Domestic Bio Workforce): Congress must maximize the impact of domestic biomanufacturing workforce training programs.

- How should the government approach creating competency models for biomanufacturing training and microcredentialing?

- Which specific areas are best suited for microcredentialing efforts?

- Additional Considerations #8 (Grant Programs): Congress should direct the National Science Foundation (NSF) to establish a federal grant program for a national system of community biology labs that would engage Americans in informal learning.

- What is most needed to support community biology labs?

- Should community labs be incorporated within universities or run as independent institutions?

It’s Summer, America’s Heating Up, and We’re Even More Unprepared

Summer officially kicked off this past weekend with the onset of a sweltering heat wave. As we hit publish on this piece, tens of millions of Americans across the central and eastern United States are experiencing sweltering temperatures that make it dangerous to work, play, or just hang out outdoors.

The good news is that even when the mercury climbs, heat illness, injury, and death are preventable. The bad news is that over the past five months, the Trump administration has dismantled essential preventative capabilities.

At the beginning of this year, more than 70 organizations rallied around a common-sense Heat Policy Agenda to tackle this growing whole-of-nation crisis. Since then, we’ve seen some encouraging progress. The new Congressional Extreme Heat Caucus presents an avenue for bipartisan progress on securing resources and legislative wins. Recommendations from the Heat Policy Agenda have already been echoed in multiple introduced bills. Four states, California, Arizona, New Jersey, and New York, now have whole-of-government heat action plans, and there are several States with plans in development. More locally, mayors are banding together to identify heat preparedness, management, and resilience solutions. FAS highlighted examples of how leaders and communities across the country are beating the heat in a Congressional briefing just last week.

But these steps in the right direction are being forestalled by the Trump Administration’s leap backwards on heat. The Heat Policy Agenda emphasized the importance of a clear, sustained federal governance structure for heat, named authorities and dedicated resourcing for federal agencies responsible for extreme heat management, and funding and technical assistance to subnational governments to build their heat readiness. The Trump Administration has not only failed to advance these goals – it has taken actions that clearly work against them.

The result? It’s summer, America’s heating up, and we’re deeply unprepared.

The heat wave making headlines today is just the latest example of how extreme heat is a growing problem for all 50 states. In just the past month, the Pacific Northwest smashed early-summer temperature records, there were days when parts of Texas were the hottest places on Earth, and Alaska – yes, Alaska – issued its first-ever heat advisory. Extreme heat is deadlier than hurricanes, floods, and tornadoes combined, and is exacerbating a mental-health crisis as well. By FAS’ estimates, extreme heat costs the nation more than $162 billion annually, costs that have made extreme heat a growing concern to private markets.

To build a common understanding of the state of federal heat infrastructure, we analyzed the status of heat-critical programs and agencies through public media, government reports, and conversations with stakeholders. All known impacts are confirmed via publicly available sources. We highlight five areas where federal capacity has been impacted:

- Leadership and governance infrastructure

- Key personnel and their expertise

- Data, forecasts, and information availability

- Funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

- Progress towards heat policy goals

This work provides answers to many of the questions our team has been asked over the last few months about what heat work continues at the federal level. With this grounding, we close with some options and opportunities for subnational governments to consider heading into Summer 2025.

What is the Current State of Federal Capacity on Extreme Heat?

Loss of leadership and governance infrastructure

At the time of publication, all but one of the co-chairs for the National Integrated Heat Health Information System’s (NIHHIS) Interagency Working Group (IWG) have either taken an early retirement offer or have been impacted by reductions in force. The co-chairs represented NIHHIS, the National Weather Service (NWS), Health and Human Services (HHS), and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The National Heat Strategy, a whole-of-government vision for heat governance crafted by 28 agencies through the NIHHIS IWG, was also taken offline. A set of agency-by-agency tasks for Strategy implementation (to build short-term readiness for upcoming heat seasons, as well as to strengthen long-term preparedness) was in development as of early 2025, but this work has stalled. There was also a goal to formalize NIHHIS via legislation, given that its existence is not mandated by law – relevant legislation has been introduced but its path forward is unclear. Staff remain at NIHHIS and are continuing the work to manage the heat.gov website, craft heat resources and information, and disseminate public communications like Heat Beat Newsletter and Heat Safety Week. Their positions could be eliminated if proposed budget cuts to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are approved by Congress.

Staffing reductions and actualized or proposed changes to FEMA and HHS, the federal disaster management agencies implicated in addressing extreme heat, are likely to be consequential in relation to extreme heat this summer. Internal reports have found that FEMA is not ready for responding to even well-recognized disasters like hurricanes, increasing the risk for a mismanaged response to an unprecedented heat disaster. The loss of key leaders at FEMA has also put a pause to efforts to integrate extreme heat within agency functions, such as efforts to make extreme heat an eligible disaster. FEMA is also proposing changes that will make it more difficult to receive federal disaster assistance. The Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response (ASPR), HHS’ response arm, has been folded into the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which has been refocused to focus solely on infectious diseases. There is still little public information for what this merger means for HHS’ implementation of the Public Health Service Act, which requires an all-hazards approach to public health emergency management. Prior to January 2025, HHS was determining how it could use the Public Health Emergency authority to respond to extreme heat.

Loss of key personnel and their expertise

Many key agencies involved in NIHHIS, and extreme heat management more broadly, have been impacted by reductions in force and early retirements, including NOAA, FEMA, HHS, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the U.S. Forest Service (USFS), and the Department of Energy (DOE). Some key agencies, like FEMA, have lost or will lose almost 2,000 staff. As more statutory responsibilities are put on fewer workers, efforts to advance “beyond scope” activities, like taking action on extreme heat, will likely be on the back burner.

Downsizing at HHS has been acutely devastating to extreme heat work. In January, the Office of Climate Change and Health Equity (OCCHE) was eliminated, putting a pause on HHS-wide coordination on extreme heat and the new Extreme Heat Working Group. In April, the entire staff of the Climate and Health program at CDC, the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), and all of the staff at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) working on extreme heat, received reduction in force notices. While it appears that staff are returning to the CDC’s National Center for Environmental Health, they have lost months of time that could have been spent on preparedness, tool development, and technical assistance to local and state public health departments. Sustained funding for extreme heat programs at HHS is under threat, the FY2026 budget for HHS formally eliminates the CDC’s Climate and Health Program, all NIOSH efforts on extreme heat, and LIHEAP.

Risks to data, forecasts, and information availability, though some key tools remain online

Staff reductions at NWS have compromised local forecasts and warnings, and some offices can no longer staff around-the-clock surveillance. Staff reductions have also compromised weather balloon launches, which collect key temperature data for making heat forecasts. Remaining staff at the NWS are handling an increased workload at one of the busiest times of the year for weather forecasting. Reductions in force, while now reversed, have impacted real-time heat-health surveillance at the CDC, where daily heat-related illness counts have been on pause since May 21, 2025 and the site is not currently being maintained as of the date of this publication.

Some tools remain online and available to use this summer, including NWS/CDC’s HeatRisk (a 7-day forecast of health-informed heat risks) and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Heat-Related EMS Activation Surveillance Dashboard (which shows the number of heat-related EMS activations, time to patient, percent transported to medical facilities, and deaths). Most of the staff that built HeatRisk have been impacted by reductions in force. The return of staff to the CDC’s Climate and Health program is a bright spot, and could bode well for the tool’s ongoing operations and maintenance for Summer 2025.

Proposed cuts in the FY26 budget will continue to compromise heat forecasting and data. The budget proposes cutting budgets for upkeep of NOAA satellites crucial to tracking extreme weather events like extreme heat; cutting budgets for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s LandSat program, which is used widely by researchers and private sector companies to analyze surface temperatures and understand heat’s risks; and fully defunding the National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network, which funds local and state public health departments to collect heat-health illness and death data and federal staff to analyze it.

Rollbacks in key funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

As of May 2025, both NIHHIS Centers of Excellence – the Center for Heat Resilient Communities and the Center for Collaborative Heat Monitoring – received stop work orders and total pauses in federal funding. These Centers were set to work with 26 communities across the country to either collect vital data on local heat patterns and potential risks or shape local governance to comprehensively address the threat of extreme heat. These communities represented a cross-cut of the United States, from urban to coastal to rural to agricultural to tribal. Both Center’s leadership plans to continue the work with the selected communities in a reduced capacity, and continue to work towards aspirational goals like a universal heat action plan. Future research, coordination, and technical assistance at NOAA on extreme heat is under fire with the proposed total elimination of NOAA Research in the FY26 budget.

At FEMA, a key source of funding for local heat resilience projects, the Building Resilience Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, has been cancelled. BRIC was the only FEMA Resilience grant that explicitly called out extreme heat in its Notice of Funding Opportunity, and funded $13 million in projects to mitigate the impacts of extreme heat. Many states have also faced difficulties in getting paid by FEMA for grants that support their emergency management divisions, and the FY26 budget proposes cuts to these grant programs. The cancellation of Americorps further reduces capacity for disaster response. FEMA is also dropping its support for improving building codes that mitigate disaster risk as well as removing requirements for subnational governments to plan for climate change.

At HHS, a lack of staff at CDC has stalled payments from key programs to prepare communities for extreme heat, the Building Resilience Against Climate Effects (BRACE) grant program and the Public Health Preparedness and Response program. BRACE is critical federal funding for state and local climate and health offices. In states like North Carolina, the BRACE program funds live-saving efforts like heat-health alerts. Both of these programs are proposed to be totally eliminated in the FY26 budget. The Hospital Preparedness Program (HPP) is also slated for elimination, despite being the sole source of federal funding for health care system readiness. HPP funds coalitions of health systems and public health departments, which have quickly responded to heat disasters like the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Domes and established comprehensive plans for future emergencies. The National Institutes of Health’s Climate and Health Initiative was eliminated and multiple grants paused in March 2025. Research on extreme weather and health may proceed, according to new agency guidelines, yet overall cuts to the NIH will impact capacity to fund new studies and new research avenues. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, which funds research on environmental health, faces a 36% reduction in its budget, from $994 million to $646 million.

Access to cool spaces is key to preventing heat-illness and death. Yet cuts, regulatory rollbacks, and program eliminations across the federal government are preventing progress towards ensuring every American can afford their energy bills. At DOE, rollbacks in energy efficiency standards for cooling equipment and the ending of the EnergyStar program will impact the costs of cooling for consumers. Thankfully, DOE’s Home Energy Rebates survived the initial funding freezes and the funding has been deployed to states to support home upgrades like heat pumps, insulation, air sealing, and mechanical ventilation. At HUD, the Green and Resilient Retrofits Program has been paused as of March 2025, which was set to fund important upgrades to affordable housing units that would have decreased the costs of cooling for vulnerable residents. At EPA, widespread pauses and cancellations in Inflation Reduction Act programs have put projects to provide more affordable cooling solutions on pause. At the U.S. Department of Agriculture, all grantees for the Rural Energy for America Program, which funds projects that provide reliable and affordable energy in rural communities, have been asked to resubmit their grants to receive allocated funding. These delays put rural community members at risk of extreme heat this summer, where they face particular risks due to their unique health and sociodemographic vulnerabilities. Finally, while the remaining $400 million in LIHEAP funding was released for this year, it faces elimination in FY26 appropriations. If this money is lost, people will very likely die and utilities will not be able to cover the costs of unpaid bills and delay improvements to the grid infrastructure to increase reliability.

Uncertain progress towards heat policy goals

Momentum towards establishing a federal heat stress rule as quickly as possible has stalled. The regulatory process for the Heat Injury and Illness Prevention in Outdoor and Indoor Work Settings is proceeding, with hearings that began June 16 and are scheduled to continue until July 3. It remains to be seen how the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) will proceed with the existing rule as written. OSHA’s National Emphasis Program (NEP) for Heat will continue until April 6, 2026. This program focuses on identifying and addressing heat-related injuries and illnesses in workplaces, and educating employers on how they can reduce these impacts on the job. To date, NEP has conducted nearly 7,000 inspections connected to heat risks, which lead to 60 heat citations and nearly 1,400 “hazard alert” letters being sent to employers.

How Can Subnational Governments Ready for this Upcoming Heat Season?

Downscaled federal capacity comes at a time when many states are facing budget shortfalls compounded by federal funding cuts and rescissions. The American Rescue Plan Act, the COVID-19 stimulus package, has been a crucial source of revenue for many local and state governments that enabled expansion in services, like extreme heat response. That funding must be spent by December 2026, and many subnational governments are facing funding cliffs of millions of dollars that could result in the elimination of these programs. While there is a growing attention to heat, it is still often deprioritized in favor of work on hazards that damage property.

Even in this environment, local and state governments can still make progress on addressing extreme heat’s impacts and saving lives. Subnational governments can:

- Conduct a data audit to ensure they are tracking the impacts of extreme heat, like emergency medical services activations, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and deaths, and tracking expenditures dedicated to any heat-related activity.

- Develop a heat preparedness and response plan, to better understand how to leverage existing resources, capacities, and partnerships to address extreme heat. This includes understanding emergency authorities available at the local and state level that could be leveraged in a crisis.

- Use their platforms to educate the public about extreme heat and share common-sense strategies that reduce the risk of heat-illness, and public health departments can target communications to the most vulnerable.

- Ensure existing capital planning and planned infrastructure build-outs prioritize resilience to extreme heat and set up cooling standards for new and existing housing and for renters. Subnational governments can also leverage strategies that reduce their fiscal risk, such as implementing heat safety practices for their own workforces and encouraging or requiring employers to deploy these practices as a way to reduce workers compensation claims.

FAS stands ready to support leaders and communities in implementing smart, evidence-based strategies to build heat readiness – and to help interested parties understand more about the impacts of the Trump administration’s actions on federal heat capabilities. Contact Grace Wickerson (gwickerson@fas.org) with inquiries.

The Data We Take for Granted: Telling the Story of How Federal Data Benefits American Lives and Livelihoods

Across the nation, researchers, data scientists, policy analysts and other data nerds are anxiously monitoring the demise of their favorite federal datasets. Meanwhile, more casual users of federal data continue to analyze the deck chairs on the federal Titanic, unaware of the coming iceberg as federal cuts to staffing, contracting, advisory committees, and funding rip a giant hole in our nation’s heretofore unsinkable data apparatus. Many data users took note when the datasets they depend on went dark during the great January 31 purge of data to “defend women,” but then went on with their business after most of the data came back in the following weeks.

Frankly, most of the American public doesn’t care about this data drama.

However, like many things in life, we’ve been taking our data for granted and will miss it terribly when it’s gone.

As the former U.S. Chief Data Scientist, I know first-hand how valuable and vulnerable our nation’s federal data assets are. However, it took one of the deadliest natural disasters in U.S history to expand my perspective from that of just a data user, to a data advocate for life.

Twenty years ago this August, Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans. The failure of the federal flood-protection infrastructure flooded 80% of the city resulting in devastating loss of life and property. As a data scientist working in New Orleans at the time, I’ll also note that Katrina rendered all of the federal data about the region instantly historical.

Our world had been turned upside down. Previous ways of making decisions were no longer relevant, and we were flying blind without any data to inform our long-term recovery. Public health officials needed to know where residents were returning to establish clinics for tetanus shots. Businesses needed to know the best locations to reopen. City Hall needed to know where families were returning to prioritize which parks they should rehabilitate first.

Normally, federal data, particularly from the Census Bureau, would answer these basic questions about population, but I quickly learned that the federal statistical system isn’t designed for rapid, localized changes like those New Orleans was experiencing.

We explored proxies for repopulation: Night lights data from NASA, traffic patterns from the local regional planning commission, and even water and electricity hookups from utilities. It turned out that our most effective proxy came from an unexpected source: a direct mail marketing company. In other words, we decided to use junk mail data to track repopulation.

Access to direct mail company Valassis’ monthly data updates was transformative, like switching on a light in a dark room. Spring Break volunteers, previously surveying neighborhoods to identify which houses were occupied or not, could now focus on repairing damaged homes. Nonprofits used evidence of returning residents to secure grants for childcare centers and playgrounds.

Even the police chief utilized this “junk mail” data. The city’s crime rates were artificially inflated because they used a denominator of annual Census population estimates that couldn’t keep pace with the rapid repopulation. Displaced residents had been afraid to return because of the sky-high crime rates, and the junk mail denominator offered a more timely, accurate picture.

I had two big realizations during this tumultuous period:

- Though we might be able to Macgyver some data to fill the immediate need, there are some datasets that only the federal government can produce, and

- I needed to expand my worldview from being just a data user, to also being an advocate for the high quality, timely, detailed data we need to run a modern society.

Today, we face similar periods of extreme change. Socio-technological shifts from AI are reshaping the workforce; climate-fueled disasters are coming at a rapid pace; and federal policies and programs are undergoing massive shifts. All of these changes will impact American communities in different ways. We’ll need data to understand what’s working, what’s not, and what we do next.

For those of us who rely on federal data in small or large ways, it’s time to champion the federal data we often take for granted. And, it’s also going to be critical that we, as active participants in this democracy, take a close look at the downstream consequences of weakening or removing any federal data collections.

There are upwards of 300,000 federal datasets. Here are just three that demonstrate their value:

- Bureau of Justice Statistics’ National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS): The NCVS is a sample survey produced through a collaboration between the Department of Justice and the Census Bureau that asks people if they’ve been victims of crime. It’s essential because it reveals the degree to which different types of crimes are underreported. Knowing the degree to which crimes like intimate partner violence, sexual assault, and hate crimes tend to be under-reported helps law enforcement agencies better interpret their own crime data and protect some of their most vulnerable constituents.

- NOAA’s ARGO fleet of drifting buoys: Innovators in the autonomous shipping industry depend on NOAA data such as that collected by the Argo Fleet of drifting buoys – an international collaboration that measures global ocean conditions. These detailed data train AI algorithms to find the safest and most fuel-efficient ocean routes.

- USGS’ North American Bat Monitoring Program: Bats save the American agricultural industry billions of dollars annually by consuming insects that damage crops. Protecting this essential service requires knowing where bats are. The USGS North American Bat Monitoring Program database is an essential resource for developers of projects that could disturb bat populations – projects such as highways, wind farms, and mining operations. This federal data not only protects bats but also helps streamline permitting and environmental impact assessments for developers.

If your work relies on federal data like these examples, it’s time to expand your role from a data user to a data advocate. Be explicit about the profound value this data brings to your business, your clients, and ultimately, to American lives and livelihoods.

That’s why I’m devoting my time as a Senior Fellow at FAS to building EssentialData.US to collect and share the stories of how specific federal datasets can benefit everyday Americans, the economy, and America’s global competitiveness.

EssentialData.US is different from a typical data use case repository. The focus is not on the user – researchers, data analysts, policymakers, and the like. The focus is on who ultimately benefits from the data, such as farmers, teachers, police chiefs, and entrepreneurs.

A good example is the Department of Transportation’s T-100 Domestic Segment Data on airplane passenger traffic. Analysts in rural economic development offices use these data to make the case for airlines to expand to their market, or for state or federal investment to increase an airport’s capacity. But it’s not the data analysts who benefit from the T-100 data. The people who benefit are the cancer patient living in a rural county who can now fly directly from his local airport to a metropolitan cancer center for lifesaving treatment, or the college student who can make it back to her home town for her grandmother’s 80th birthday without missing class.

Federal data may be largely invisible, but it powers so many products and services we depend on as Americans, starting with the weather forecast when we get up in the morning. The best way to ensure that these essential data keep flowing is to tell the story of their value to the American people and economy. Share the story of your favorite dataset with us at EssentialData.US. Here’s a direct link to the form.

Federal Climate Policy Is Being Gutted. What Does That Say About How Well It Was Working?

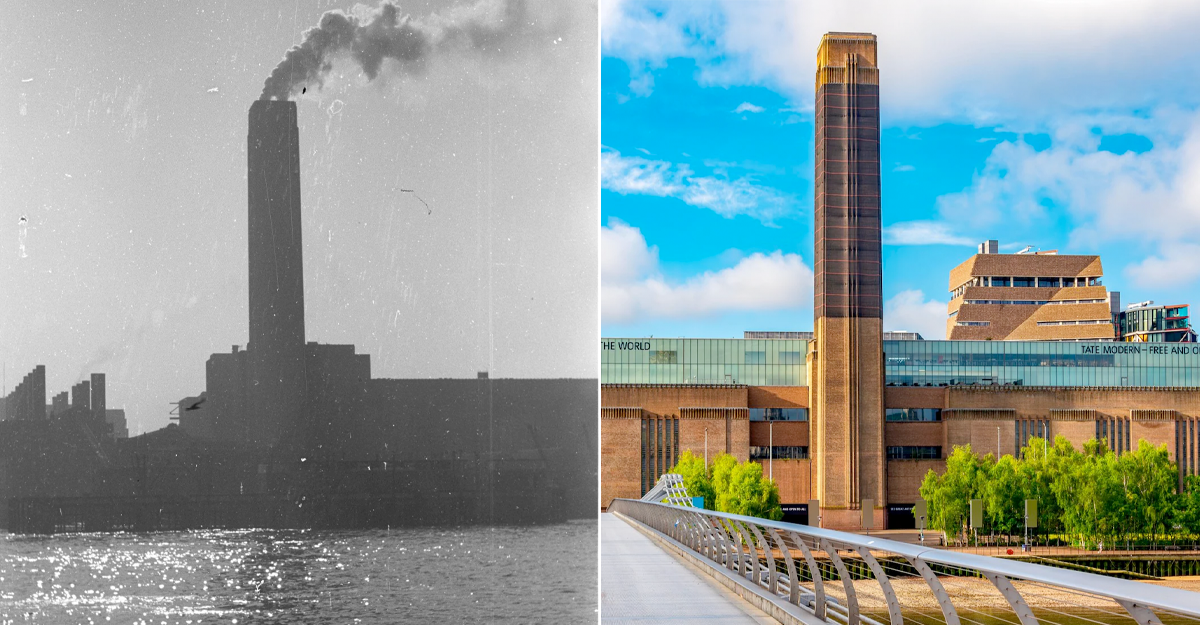

On the left is the Bankside Power Station in 1953. That vast relic of the fossil era once towered over London, oily smoke pouring from its towering chimney. These days, Bankside looks like the right:

The old power plant’s vast turbine hall is now at the heart of the airy Tate Modern Art Museum; sculptures rest where the boilers once churned.

Bankside’s evolution into the Tate illustrates that transformations, both literal and figurative, are possible for our energy and economic systems. Some degree of demolition – if paired with a plan – can open up space for something innovative and durable.

Today, the entire energy sector is undergoing a massive transformation. After years of flat energy demand served by aging fossil power plants, solar energy and battery storage are increasingly dominating energy additions to meet rising load. Global investment in clean energy will be twice as big as investment in fossil fuels this year. But in the United States, the energy sector is also undergoing substantial regulatory demolition, courtesy of a wave of executive and Congressional attacks and sweeping potential cuts to tax credits for clean energy.

What’s missing is a compelling plan for the future. The plan certainly shouldn’t be to cede leadership on modern energy technologies to China, as President Trump seems to be suggesting; that approach is geopolitically unwise and, frankly, economically idiotic. But neither should the plan be to just re-erect the systems that are being torn down. Those systems, in many ways, weren’t working. We need a new plan – a new paradigm – for the next era of climate and clean energy progress in the United States.

Asking Good Questions About Climate Policy Designs

How do we turn demolition into a superior remodel? First, we have to agree on what we’re trying to build. Let’s start with what should be three unobjectionable principles.

Principle 1. Climate change is a problem worth fixing – fast. Climate change is staggeringly expensive. Climate change also wrecks entire cities, takes lives, and generally makes people more miserable. Climate change, in short, is a problem we must fix. Ignoring and defunding climate science is not going to make it go away.

Principle 2. What we do should work. Tackling the climate crisis isn’t just about cleaning up smokestacks or sewer outflows; it’s about shifting a national economic system and physical infrastructure that has been rooted in fossil fuels for more than a century. Our responses must reflect this reality. To the extent possible, we will be much better served by developing fit-for-purpose solutions rather than just press-ganging old institutions, statutes, and technologies into climate service.

Principle 3. What we do should last. The half-life of many climate strategies in the United States has been woefully short. The Clean Power Plan, much touted by President Obama, never went into force. The Trump administration has now turned off California’s clean vehicle programs multiple times. Much of this hyperpolarized back-and-forth is driven by a combination of far-right opposition to regulation as a matter of principle and the fossil fuel industry pushing mass de-regulation for self-enrichment – a frustrating reality, but one that can only be altered by new strategies that are potent enough to displace vocal political constituencies and entrenched legacy corporate interests.

With these principles in mind, the path forward becomes clearer. We can agree that ambitious climate policy is necessary; protecting Americans from climate threats and destabilization (Principle 1) directly aligns with the founding Constitutional objectives of ensuring domestic tranquility, providing for the common defense, and promoting general welfare. We can also agree that the problem in front of us is figuring out which tools we need, not how to retain the tools we had, regardless of their demonstrated efficacy (Principle 2). And we can recognize that achieving progress in the long run requires solutions that are both politically and economically durable (Principle 3).

Below, we consider how these principles might guide our responses to this summer’s crop of regulatory reversals and proposed shifts in federal investment.

Honing Regulatory Approaches

The Trump Administration recently announced that it plans to dismantle the “endangerment finding” – the legal predicate for the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and transportation; meanwhile, the Senate revoked permission for California to enforce key car and truck emission standards. It has also proposed to roll back key power plant toxic and greenhouse gas standards. We agree with those who think that these actions are scientifically baseless and likely illegal, and therefore support efforts to counter them. But we should also reckon honestly with how the regulatory tools we are defending have played out so far.

Federal and state pollution rules have indisputably been a giant public-health victory. EPA standards under the Clean Air Act led directly to dramatic reductions in harmful particulate matter and other air pollutants, saving hundreds of thousands of lives and avoiding millions of cases of asthma and other respiratory diseases. Federal regulations similarly caused mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants to drop by 90% in just over a decade. Pending federal rollbacks of mercury rules thus warrant vocal opposition. In the transportation sector, tailpipe emissions standards for traditional combustion vehicles have been impressively effective. These and other rules have indeed delivered some climate benefits by forcing the fossil fuel industry to face pollution clean-up costs and driving development of clean technologies.

But if our primary goal is motivating a broad energy transition (i.e., what needs to happen per Principle 1), then we should think beyond pollution rules as our only tools – and allocate resources beyond immediate defensive fights. Why? The first reason is that, as we have previously written, these rules are poorly equipped to drive that transition. Federal and state environmental agencies can do many things well, but running national economic strategy and industrial policy primarily through pollution statutes is hardly the obvious choice (Principle 2).

Consider the power sector. The most promising path to decarbonize the grid is actually speeding up replacement of old coal and gas plants with renewables by easing unduly complex interconnection processes that would speed adding clean energy to address rising demand, and allow the old plants to retire and be replaced – not bolting pollution-control devices on ancient smokestacks. That’s an economic and grid policy puzzle, not a pollution regulatory challenge, at heart. Most new power plants are renewable- or battery-powered anyway. Some new gas plants might be built in response to growing demand, but the gas turbine pipeline is backed up, limiting the scope of new fossil power, and cheaper clean power is coming online much more quickly wherever grid regulators have their act together. Certainly regulations could help accelerate this shift, but the evidence suggests that they may be complementary, not primary, tools.

The upshot is that economics and subnational policies, not federal greenhouse gas regulation, have largely driven power plant decarbonization to date and therefore warrant our central focus. Indeed, states that have made adding renewable infrastructure easy, like Texas, have often been ahead of states, like California, where regulatory targets are stronger but infrastructure is harder to build. (It’s also worth noting that these same economics mean that the Trump Administration’s efforts to revert back to a wholly fossil fuel economy by repealing federal pollution standards will largely fail – again, wrong tool to substantially change energy trajectories.)

The second reason is that applying pollution rules to climate challenges has hardly been a lasting strategy (Principle 3). Despite nearly two decades of trying, no regulations for carbon emissions from existing power plants have ever been implemented. It turns out to be very hard, especially with the rise of conservative judiciaries, to write legal regulations for power plants under the Clean Air Act that both stand up in Court and actually yield substantial emissions reductions.

In transportation, pioneering electric vehicle (EV) standards from California – helped along by top-down economic leverage applied by the Obama administration – did indeed begin a significant shift and start winning market share for new electric car and truck companies; under the Biden administration, California doubled down with a new set of standards intended to ultimately phase out all sales of gas-powered cars while the EPA issued tailpipe emissions standards that put the industry on course to achieve at least 50% EV sales by 2030. But California’s EV standards have now been rolled back by the Trump administration and a GOP-controlled Congress multiple times; the same is true for the EPA rules. Lest we think that the Republican party is the sole obstacle to a climate-focused regulatory regime that lasts in the auto sector, it is worth noting that Democratic states led the way on rollbacks. Maryland, Massachusetts, Oregon, and Vermont all paused, delayed, or otherwise fuzzed up their plans to deploy some of their EV rules before Congress acted against California. The upshot is that environmental standards, on their own, cannot politically sustain an economic transition at this scale without significant complementary policies.

Now, we certainly shouldn’t abandon pollution rules – they deliver massive health and environmental benefits, while forcing the market to more accurately account for the costs of polluting technologies, But environmental statutes built primarily to reduce smokestack and tailpipe emissions remain important but are simply not designed to be the primary driver of wholesale economic and industrial change. Unsurprisingly, efforts to make them do that anyway have not gone particularly well – so much so that, today, greenhouse gas pollution standards for most economic sectors either do not exist, or have run into implementation barriers. These observations should guide us to double down on the policies that improve the economics of clean energy and clean technology — from financial incentives to reforms that make it easier to build — while developing new regulatory frameworks that avoid the pitfalls of the existing Clean Air Act playbook. For example, we might learn from state regulations like clean electricity standards that have driven deployment and largely withstood political swings.

To mildly belabor the point – pollution standards form part of the scaffolding needed to make climate progress, but they don’t look like the load-bearing center of it.

Refocusing Industrial Policy

Our plan for the future demands fresh thinking on industrial policy as well as regulatory design. Years ago, Nobel laureate Dr. Elinor Ostrom pointed out that economic systems shift not as a result of centralized fiat, from the White House or elsewhere, but from a “polycentric” set of decisions rippling out from every level of government and firm. That proposition has been amply borne out in the clean energy space by waves of technology innovation, often anchored by state and local procurement, regional technology clusters, and pioneering financial institutions like green banks.

The Biden Administration responded to these emerging understandings with the CHIPS and Science Act, Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) – a package of legislation intended to shore up U.S. leadership in clean technology through investments that cut across sectors and geographies. These bills included many provisions and programs with top-down designs, but the package as a whole but did engage with, and encourage, polycentric and deep change.

Here again, taking a serious look at how this package played out can help us understand what industrial policies are most likely to work (Principle 2) and to last (Principle 3) moving forward.

We might begin by asking which domestic clean-technology industries need long-term support and which do not in light of (i) the multi-layered and polycentric structure of our economy, and (ii) the state of play in individual economic sectors and firms at the subnational level. IRA revisions that appropriately phase down support for mature technologies in a given sector or region where deployment is sufficient to cut emissions at an adequate pace could be worth exploring in this light – but only if market-distorting supports for fossil-fuel incumbents are also removed. We appreciate thoughtful reform proposals that have been put forward by those on the left and right.

More directly: If the United States wants to phase down, say, clean power tax credits, such changes should properly be phased with removals of support for fossil power plants and interconnection barriers, shifting the entire energy market towards a fair competition to meet increasing load, as well as new durable regulatory structures that ensure a transition to a low-carbon economy at a sufficient pace. Subsidies and other incentives could appropriately be retained for technologies (e.g., advanced battery storage and nuclear) that are still in relatively early stages and/or for which there is a particularly compelling argument for strengthening U.S. leadership. One could similarly imagine a gradual shift away from EV tax credits – if other transportation system spending was also reallocated to properly balance support among highways, EV charging stations, transit, and other types of transportation infrastructure. In short, economic tools have tremendous power to drive climate progress, but must be paired with the systemic reforms needed to ensure that clean energy technologies have a fair pathway to achieving long-term economic durability.

Our analysis can also touch on geopolitical strategy. It is true that U.S. competitors are ahead in many clean technology fields; it is simultaneously true that the United States has a massive industrial and research base that can pivot ably with support. A pure on-shoring approach is likely to be unwise – and we have just seen courts enjoin the administration’s fiat tariff policy that sought that result. That’s a good opportunity to have a more thoughtful conversation (in which many are already engaging) on areas where tariffs, public subsidies, and other on-shoring planning can actually position our nation for long-term economic competition on clean technology. Opportunities that rise to the top include advanced manufacturing, such as for batteries, and critical industries, like the auto sector. There is also a surprising but potent national security imperative to center clean energy infrastructure in U.S. industrial policy, given the growing threat of foreign cyberattacks that are exploiting “seams” in fragile legacy energy systems.

Finally, our analysis suggests that states, which are primarily responsible for economic policy in their jurisdictions, have a role to play in this polycentric strategy that extends beyond simply replicating repealed federal regulations. States have a real opportunity in this moment to wed regulatory initiatives with creative whole-of-the-economy approaches that can actually deliver change and clean economic diversification, positioning them well to outlast this period of churn and prosper in a global clean energy transition.

A successful and “sticky” modern industrial policy must weave together all of the above considerations – it must be intentionally engineered to achieve economic and political durability through polycentric change, rather than relying solely or predominantly on large public subsidies.

Conclusion

The Trump Administration has moved with alarming speed to demolish programs, regulations, and institutions that were intended to make our communities and planet more liveable. Such wholesale demolition is unwarranted, unwise, and should not proceed unchecked. At the same time, it is, as ever, crucial to plan for the future. There is broad agreement that achieving an effective, equitable, and ethical energy transition requires us to do something different. Yet there are few transpartisan efforts to boldly reimagine regulatory and economic paradigms. Of course, we are not naive: political gridlock, entrenched special interests, and institutional inertia are formidable obstacles to overcome. But there is still room, and need, to try – and effort bears better fruit when aimed at the right problems. We can begin by seriously debating which past approaches work, which need to be improved, which ultimately need imaginative recasting to succeed in our ever-more complex world. Answers may be unexpected. After all, who would have thought that the ultimate best future of the vast oil-fired power station south of the Thames with which we began this essay would, a few decades later, be a serene and silent hall full of light and reflection?

50 Years, $50 Billion in Savings: Don’t Pull the Plug on FEMP

When it comes to energy use, no one tops Uncle Sam. With more than 300,000 buildings and 600,000 vehicles, the Federal Government is the nation’s largest energy consumer. That means any effort to conserve power across federal operations directly benefits taxpayers, strengthens national security, and reduces emissions.

Since 1975, the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP) has been leading that charge. Born out of the oil crisis and authorized under the Federal Energy Policy and Conservation Act (1975), FEMP has quietly transformed how the federal government uses energy, helping agencies save money, modernize infrastructure, and meet ambitious energy goals.

FEMP has been backed by bipartisan support across administrations. In recent years, a bipartisan group of Senators hailing from states across the country—from Hawaii, to Ohio, to New Hampshire, and West Virginia—cosponsored legislation to formally authorize FEMP and establish energy and water reduction goals for federal buildings in an effort to reduce emissions and save money.

Over time, FEMP’s role has expanded to include a wide range of Congressional mandates: from helping agencies leverage funding for infrastructure modernization, to tracking agency accountability, to offering cutting-edge technical assistance. But perhaps its most powerful achievement isn’t written into statute: FEMP saves the federal government billions of dollars.

In fact, FEMP has done the unthinkable: it’s achieved a “50/50/50.”

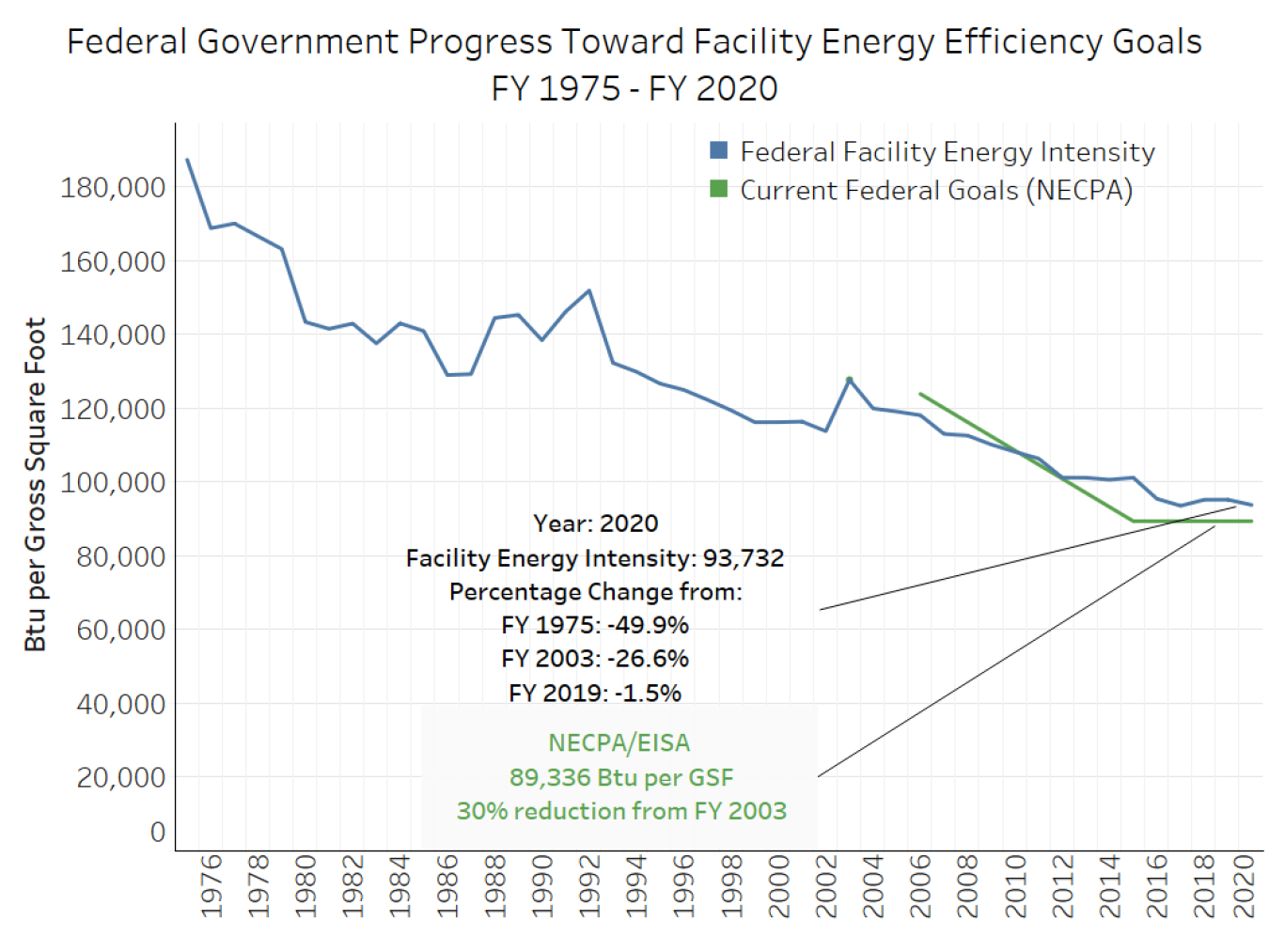

Over the past 50 years, FEMP has delivered:

- A 50% reduction in federal energy intensity

- $50 billion in cumulative energy cost savings

- And this year, it marks its 50th anniversary

Since 1975, FEMP has helped agencies reduce the energy intensity of their facilities by 50%.

So what’s behind these staggering savings, and how can FEMP build on its legacy of efficiency to meet the challenges of the next 50 years? That is, if its operations aren’t wound down, as DOE leadership has proposed for FEMP in the FY2026 budget.1

The AFFECT Program: Investing in Smarter, Cleaner Government

When it comes to saving taxpayers money while cutting emissions, few programs punch above their weight like FEMP’s AFFECT program—short for Assisting Federal Facilities with Energy Conservation Technologies.