The New York Times: Which President Cut the Most Nukes?

By Hans M. Kristensen

The New York Time today profiles my recent blog about U.S. presidential nuclear weapon stockpile reductions.

The core of the story is that the Obama administration, despite its strong arms control rhetoric and efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons, so far has cut fewer nuclear warheads from the U.S. nuclear weapon stockpile than any other administration in history.

Even in terms of effect on the overall stockpile size, the Obama administration has had the least impact of any of the post-Cold War presidents.

There are obviously reasons for the disappointing performance: The administration has been squeezed between, on the one side, a conservative U.S. congress that has opposed any and every effort to reduce nuclear forces, and on the other side, a Russian president that has rejected all proposals to reduce nuclear forces below the New START Treaty level and dismissed ideas to expand arms control to non-strategic nuclear weapons (even though he has recently said he is interested in further reductions).

As a result, the United States and its allies (and Russians as well) will be threatened by more nuclear weapons than could have been the case had the Obama administration been able to fulfill its arms control agenda.

Congress only approved the modest New START Treaty in return for the administration promising to undertake a sweeping modernization of the nuclear arsenal and production complex. Because the force level is artificially kept at levels above and beyond what is needed for national and international security commitments, the bill to the American taxpayer will be much higher than necessary.

The New York Times article says the arms control community is renouncing the Obama administration for its poor performance. While we are certainly disappointed, what we’re actually seeking is a policy change that cuts excess capacity in the arsenal, eliminates redundancy, stimulates further international reductions, and saves the taxpayers billions of dollars in the process.

In addition to taking limited unilateral steps to reduce excess nuclear capacity, the Obama administration should spend its remaining two years in office testing Putin’s recent insistence on “negotiating further nuclear arms reductions.” The fewer nuclear weapons that threaten Americans and Russians the better. That should be a no-brainer for any president and any congress.

New York Times: Which President Cut the Most Nukes?

FAS Blog: How Presidents Arm and Disarm

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

How Presidents Arm and Disarm

The Obama administration has cut fewer nuclear weapons than any other post-Cold War administration.

It’s a funny thing: the administrations that talk the most about reducing nuclear weapons tend to reduce the least.

Analysis of the history of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile shows that the Obama administration so far has had the least effect on the size of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidencies.

In fact, in terms of warhead numbers, the Obama administration so far has cut the least warheads from the stockpile of any administration ever.

I have previously described how Republican presidents historically – at least in the post-Cold War era – have been the biggest nuclear disarmers, in terms of warheads retired from the Pentagon’s nuclear warhead stockpile.

Additional analysis of the stockpile numbers declassified and published by the Obama administration reveals some interesting and sometimes surprising facts.

What went wrong? The Obama administration has recently taken a beating for its nuclear modernization efforts, so what can President Obama do in his remaining two years in office to improve his nuclear legacy?

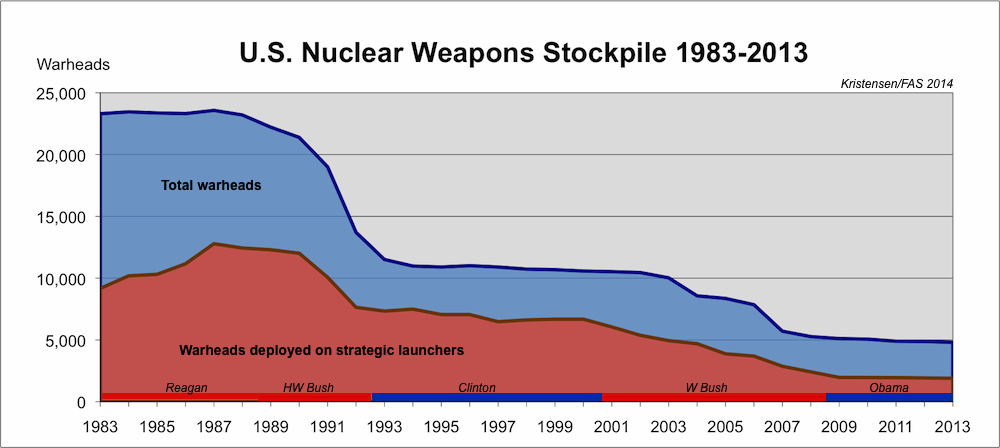

Effect on Warhead Numbers

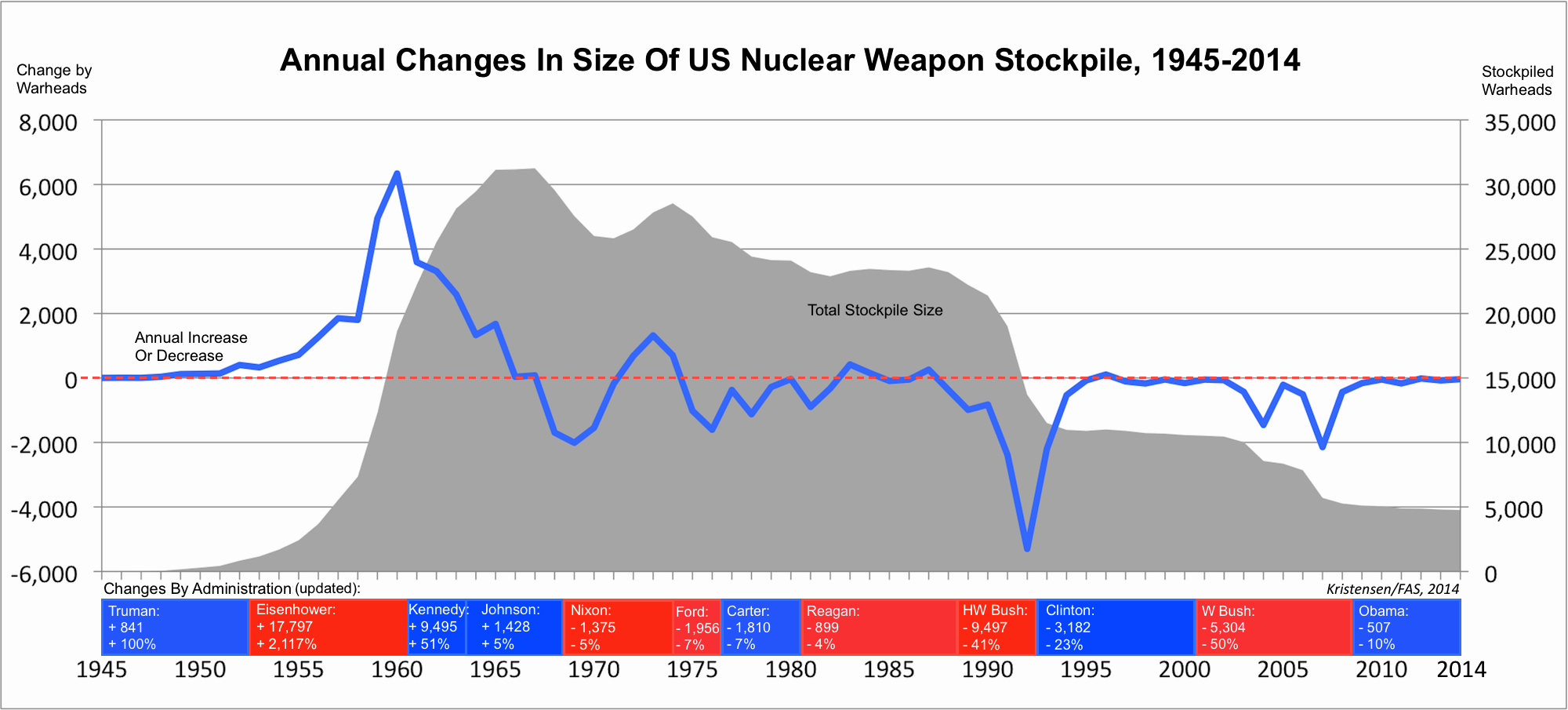

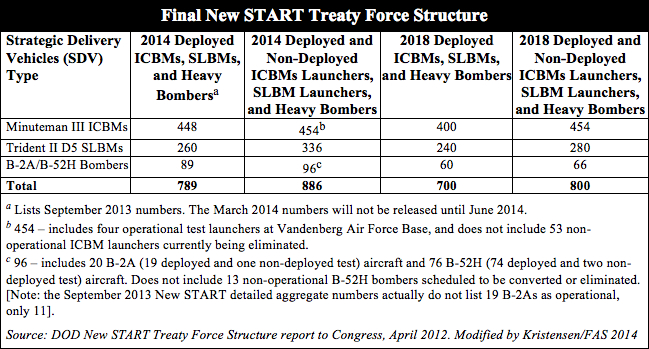

On the graph above I have plotted the stockpile changes over time in terms of the number of warheads that were added or withdrawn from the stockpile each year. Below the graph are shown the various administrations with the total number of warheads that each added or withdrew from the stockpile during its period in office.

The biggest increase in the stockpile occurred during the Eisenhower administration, which added a total of 17,797 warheads – an average of 2,225 warheads per year! Those were clearly crazy times; the all-time peak growth in one year was 1960, when 6,340 warheads were added to the stockpile! That same year, the United Sates produced a staggering 7,178 warheads, rolling them off the assembly line at an average rate of 20 new warheads every single day.

The Kennedy administration added another 9,495 warheads in the nearly three years before President John F. Kennedy was assassinated in October 1963. The Johnson administration initially continued increasing the stockpile and it was in 1967 that the stockpile reached its all-time high of 31,255 warheads. In its second term, however, the Johnson administration began reducing the stockpile – the first U.S. administration to do so – and ended up shrinking the stockpile by 1,428 warheads.

During the Nixon administration, the military started loading multiple warheads on ballistic missiles, but the stockpile declined for the first time due to retirement of large numbers of older warhead types. The successor, the Ford administration, reduced the stockpile and President Gerald Ford actually became the Cold War-period president who reduced the size of the stockpile the most: 1,956 warheads.

The Carter administration came in a close second Cold War disarmer with 1,810 warheads withdrawn from the stockpile.

The Reagan administration, which in its first term was seen by many as ramping up the Cold War, ended up shrinking the total stockpile by almost 900 warheads. But during three of its years in office, the administration actually increased the stockpile slightly, and the portion of those warheads that were deployed on strategic delivery vehicles increased as well.

As the first post-Cold War administration, the George H.W. Bush presidency initiated enormous nuclear weapons reductions and ended up shrinking the stockpile by almost 9,500 warheads – almost exactly the number the Kennedy administration increased the stockpile. In one year (1992), Bush cut 5,300 warheads, more than any other president – ever. Much of the Bush cut was related to the retirement of non-strategic nuclear weapons.

The Clinton administration came into office riding the Bush reduction wave, so to speak, and in its first term cut approximately 3,000 warheads from the stockpile. But in his second term, President Clinton slowed down significantly and in one year (1996) actually increased the stockpile by 107 weapons – the first time since 1987 that had happened and the only increase in the post-Cold War era so far. It is still unclear what caused the 1996 increase. When the Clinton administration left office, there were still approximately 10,500 nuclear warheads in the stockpile.

President George W. Bush, who many of us in the arms control community saw as a lightning rod for trying to build new nuclear weapons and advocating more proactive use against so-called “rogue” states, ended up becoming one of the great nuclear disarmers of the post-Cold War era. Between 2004 and 2007 (mainly), the Bush W. administration unilaterally cut the stockpile by more than half to roughly 5,270 warheads, a level not seen since the Eisenhower administration. Yet the remaining Bush arsenal was considerably more capable than the Eisenhower arsenal.

President Barack Obama took office with a strong arms control profile, including a pledge to reduce the number and role of nuclear weapons, taking nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger” alert, and “put and end to Cold War thinking.” So far, however, this policy appears to have had only limited effect on the size of the stockpile, with about 500 warheads retired over six years.

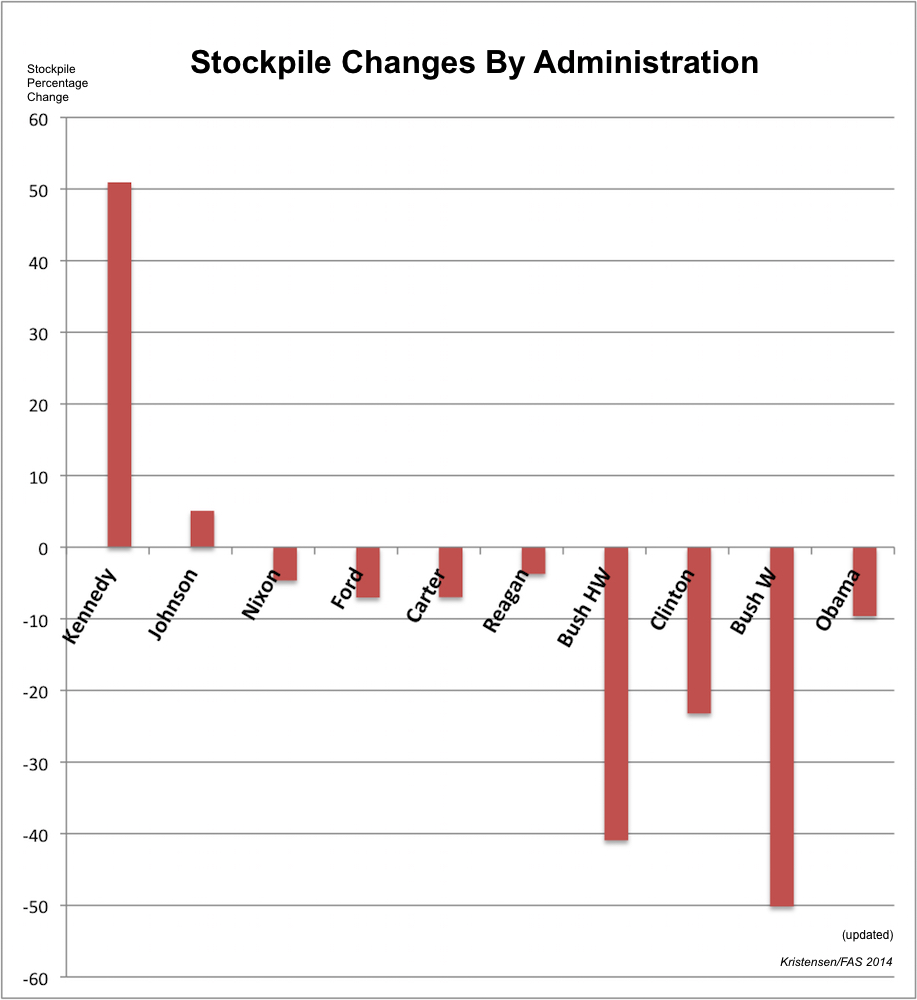

Effect On Stockpile Size

Counting warhead numbers is interesting but since the stockpile today is much smaller than during the previous three presidencies, comparing the number of warheads retired doesn’t accurately describe the degree of change inflicted by each president.

A better way is to compare the reductions as a percentage of the size of the stockpile at the beginning of each presidency. That way the data more clearly illustrates how much of an impact on stockpile size each president was responsible for.

This type of comparison shows that George W. Bush changed the stockpile the most: by a full 50 percent. His father, President H.W. Bush, came in a strong second with a 41 percent reduction. Combined, the Bush presidents cut a staggering 14,801 warheads from the stockpile during their 12 years in office – 1,233 warheads per year. President Clinton reduced the stockpile by 23 percent during his eight years in office.

The Obama administration has had less effect on the nuclear weapon stockpile than any other post-Cold War administration.

Despite his strong rhetoric about reducing the numbers of nuclear weapons, however, President Obama so far had the least effect on the size of the stockpile of any of the post-Cold War presidents: a reduction of 10 percent over six years. The remaining two years of the administration will likely see some limited reductions due to force adjustments and management, but nothing on the scale seen during the tree previous post-Cold War presidencies.

What Went Wrong?

There are of course reasons for the Obama administration’s limited success in reducing the number of nuclear weapons compared with the accomplishments of previous post-Cold War administrations.

The first reason is that the Obama administration during all of its tenure has faced a conservative Congress that has openly opposed any attempts to reduce the arsenal significantly. Even the modest New START Treaty was only agreed to in return for commitments to modernize the remaining arsenal. A conservative Congress does not complain when Republican presidents reduce the stockpile, only when Democratic president try to do so. As a result of the opposition, the United States is now stuck with a larger and more expensive nuclear arsenal than had Congress agreed to significant reductions.

A second reason is that Russian president Vladimir Putin has rejected additional arms reductions beyond the New START Treaty. Because the Obama administration has made additional reductions conditioned on Russian agreement, the United States today deploys one-third more nuclear warheads than it needs for national and international security commitments. Ironically, because of Putin’s opposition to additional reductions, Russia will now be “threatened” by more U.S. nuclear weapons than had Putin agreed to further reductions beyond New START. As a result, Russian taxpayers will have to pay more to maintain a bigger Russian nuclear force than would otherwise have been necessary.

A third reason is that the U.S. nuclear establishment during internal nuclear policy reviews was largely successful in beating back the more drastic disarmament ambitions president Obama may have had. Even before the Nuclear Posture Review was completed in April 2010, a future force level had already been decided for the New START Treaty based largely on the Bush administration’s guidance from 2002. President Obama’s Employment Strategy from June 2013 could have changed that, but it didn’t. It failed to order additional reductions beyond New START, reaffirmed the need for a Triad, retained the current alert and readiness level, and rejected less ambitious and demanding targeting strategies.

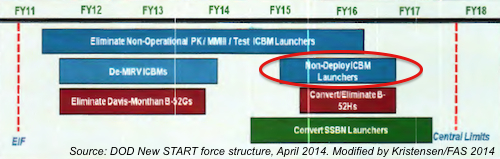

In the long run, some of the Obama administration’s policies are likely to result in additional unilateral reductions to the stockpile. One of these is the decision that fewer non-deployed warheads are needed in the “hedge.” Another effect will come from the decision to reduce the number of missiles on the next-generation ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 16, which will unilaterally reduce the number of warheads needed for the sea-based leg of the Triad. A third effect will come from a decision to phase out most of the gravity bombs in the arsenal. But these decisions depend on modernization of nuclear weapons production facilities and weapons and are unlikely to have a discernible effect on the size of the stockpile or arsenal until well after president Obama has left office.

The Next Two Years

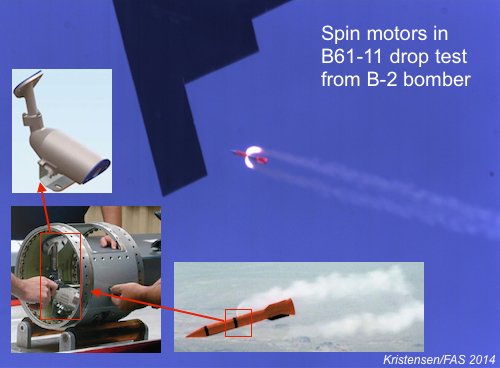

During its last two years in office, the Obama administration’s best change to achieve some of the stockpile reductions it failed to demonstrate in the first six years would be to initiate reductions now that are planned for later. In addition to implementing the reductions planned under the New START Treaty early, potential options include offloading excess Trident II SLBMs and retiring excess W76 warheads above what is needed for arming the future fleet of 12 SSBNX submarines; there are currently nearly 50 Trident II SLBMs too many deployed and about 800 W76s too many in the stockpile, so many that the Navy has asked DOE to accept transfer of excess W76s from navy depots faster than planned to free up space and save money. It also includes retiring excess warheads for cruise missiles and gravity bombs above what’s required for the B61-12 and LRSO programs; most, if not all, B61-3, B61-10, B83-1, and W84 warheads could probably be retired right away. Moreover, several hundred W78 and W87 warheads for the Minuteman ICBMs could probably be retired because they’re in excess of what’s needed for the force planned under New START.

But in addition to retiring excess warheads, there are also strong fiscal and operational reasons to work with congressional leaders interested in trimming the planned modernization of the remaining nuclear forces. Options include reducing the SSBNX program from 12 to 10 or 8 operational submarines, reducing the ICBM force to 300 by closing one of the three bases and ending considerations to develop a new mobile or “hybrid” ICBM, delaying the next-generation bomber, canceling the new cruise missile (LRSO), scaling back the B61-12 program to a simple life-extension of the B61-7, canceling nuclear capability for the F-35 fighter-bomber, and work with NATO allies to phase out deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe. Such reductions would have the added benefit of significantly reducing the capacity needed for warhead life-extension programs and production facilities.

Achieving some or all of these reductions would free up significant resources more urgently needed for maintaining and modernizing non-nuclear forces. The excess nuclear forces provide no discernible benefits to day-to-day national security needs and the remaining forces would still be more than adequate to deter and defeat potential adversaries – even a more assertive Russia.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

W80-1 Warhead Selected For New Nuclear Cruise Missile

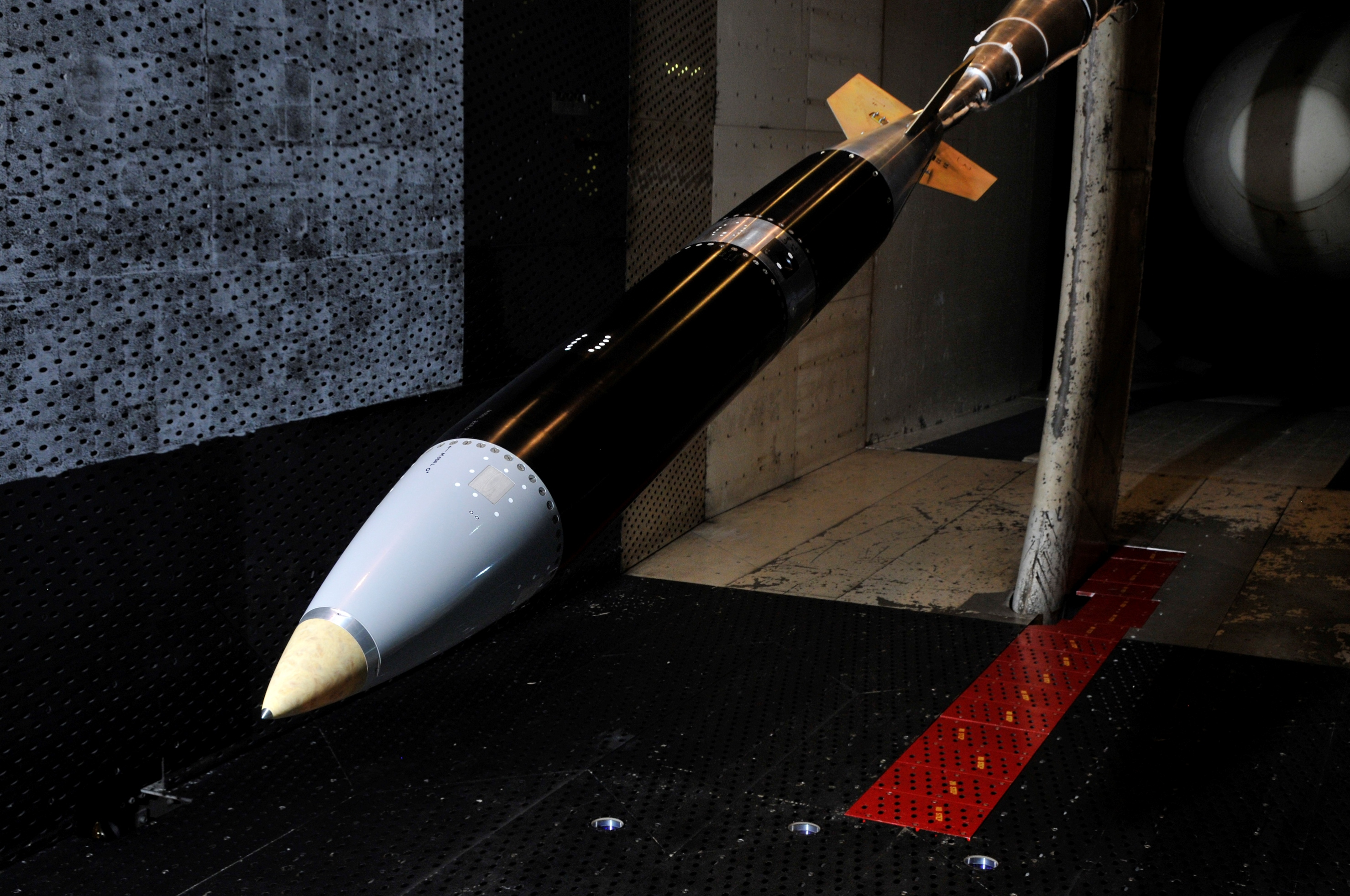

The U.S. Nuclear Weapons Council has selected the W80-1 thermonuclear warhead for the Air Force’s new nuclear cruise missile (Long-Range Standoff, LRSO) scheduled for deployment in 2027.

The W80-1 warhead is currently used on the Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), but will be modified during a life-extension program and de-deployed with a new name: W80-4.

Under current plans, the ALCM will be retired in the mid-2020s and replaced with the more advanced LRSO, possibly starting in 2027.

The enormous cost of the program – $10-20 billion by some estimates – is robbing defense planners of resources needed for more important non-nuclear capabilities.

Even though the United States has thousands of nuclear warheads on ballistic missiles and is building a new penetrating bomber to deliver nuclear bombs, STRATCOM and Air Force leaders are arguing that a new nuclear cruise missile is needed as well.

But their description of the LRSO mission sounds a lot like old-fashioned nuclear warfighting that will add new military capabilities to the arsenal in conflict with the administration’s promise not to do so and reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

What Kind of Warhead?

The selection of the W80-1 warhead for the LRSO completes a multi-year process that also considered using the B61 and W84 warheads.

The W80-4 selected for the LRSO will be the fifth modification name for the W80 warhead (see table below): The first was the W80-0 for the Navy’s Tomahawk Land-Attack Cruise Missile (TLAM/N), which was retired in 2011; the second is the W80-1, which is still used the ALCM; the third was the W80-2, which was a planned LEP of the W80-0 but canceled in 2006; the fourth was the W80-3, a planned LEP of the W80-1 but canceled in 2006.

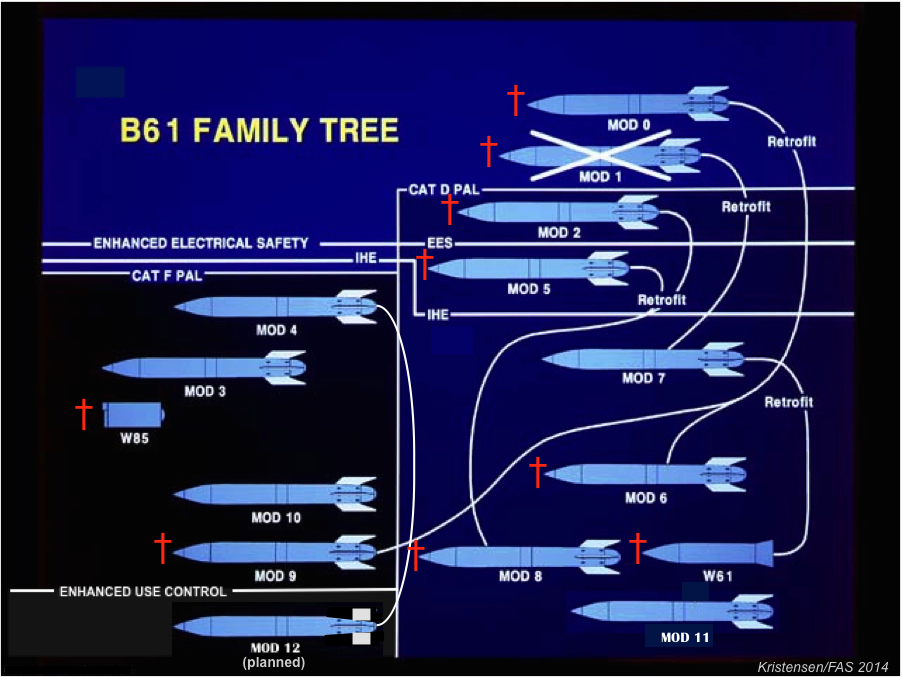

The B61 warhead has been used as the basis for a wide variety of warhead designs. It currently exists in five gravity bomb versions (B61-4, B61-4, B61-7, B61-10, B61-11) and was also used as the basis for the W85 warhead on the Pershing II ground-launched ballistic missile. After the Pershing II was eliminated by the INF Treaty, the W85 was converted into the B61-10. But the B61 was not selected for the LRSO partly because of concern about the risk of common-component failure from basing too many warheads on the same basic design.

The W84 was developed for the ground-launched cruise missile (BGM-109G), another weapon eliminated by the INF Treaty. As a more modern warhead, it includes a Fire Resistant Pit (which the W80-1 does not have) and a more advanced Permissive Action Link (PAL) use-control system. The W84 was retired from the stockpile in 2008 but was brought back as a LRSO candidate but was not selected, partly because not enough W84s were built to meet the requirement for the planned LRSO inventory.

Cost Estimates

In the past two year, NNSA has provided two very different cost estimates for the W80-4. The FY2014 Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan (SSMP) published in June 2013 projected a total cost of approximately $11.6 billion through 2030. The FY2015 SSMP, in contrast, contained a significantly lower estimate: approximately $6.8 billion through 2033 (see graph below).

Official cost estimates for the W80-4 vary significantly.

The huge difference in the cost estimates (nearly 50%) is not explained in detail in the FY2015 SSMP, which only states that the FY2014 numbers were updated with a smaller “escalation factor” and “improvements in the cost models.” Curiously, the update only reduces the cost for the years that were particularly high (2019-2027), the years with warhead development and production engineering. The two-third reduction in the cost estimate may make it easier for NNSA to secure Congressional funding, but it also raises significant uncertainty about what the cost will actually be.

Assuming a planned production of approximately 500 LRSOs (there are currently 528 ALCMs in the stockpile and the New START Treaty does not count or limit cruise missiles), the cost estimates indicate a complex W80-4 LEP on par with the B61-12 LEP. NNSA told me the plan is to use many of the non-nuclear components and technologies on the W80-4 that were developed for the B61-12.

In addition to the cost of the W80-4 warhead itself, the cost estimate for completing the LRSO has not been announced but $227 million are programmed through 2019. Unofficial estimates put the total cost for the LRSO and W80-4 at $10-20 billion. In addition to these weapons costs, integration on the B-2A and next-generation long-range bomber (LRS-B) will add hundreds of millions more.

The W80-1 is not big, seen here with the author at the nuclear museum in Albuquerque, but it packs explosive yields of 5-150 kilotons.

What’s The Mission?

Why does the Air Force need a new nuclear cruise missile?

During a recent meeting with Pentagon officials, I asked why the LRSO was needed, given that the military also has gravity bombs on its bombers. “Because of what you see on that map,” a senior defense official said pointing to a large world map on the wall. The implication was that many targets would be risky to get to with a bomber. When reminded that the military also has land- and sea-based ballistic missiles that can reach all of those targets, another official explained: “Yes but they’re all brute weapons with high-yield warheads. We need the targeting flexibility and lower-yield options that the LRSO provides.”

The assumption for the argument is that if the Air Force didn’t have a nuclear cruise missile, an adversary could gamble that the United States would not risk an expensive stealth bomber to deliver a nuclear bomb and would not want to use ballistic missiles because that would be escalating too much. That’s quite an assumption but for the nuclear warfighter the cruise missile is seen as this great in-between weapon that increases targeting flexibility in a variety of regional strike scenarios.

That conversation could have taken place back in the 1980s because the answers sounded more like warfighting talk than deterrence. The two roles can be hard to differentiate and the Air Force’s budget request seems to include a bit of both: the LRSO “will be capable of penetrating and surviving advanced Integrated Air Defense Systems (IADS) from significant stand off range to prosecute strategic targets in support of the Air Force’s global attack capability and strategic deterrence core function.”

The deterrence function is provided by the existence of the weapon, but the global attack capability is what’s needed when deterrence fails. At that point, the mission is about target destruction: holding at risk what the adversary values most. Getting to the target is harder with a cruise missile than a ballistic missile, but it is easier with a cruise missile than a gravity bomb because the latter requires the bomber to fly very close to the target. That exposes the platform to all sorts of air defense capabilities. That’s why the Pentagon plans to spend a lot of money on equipping its next-generation long-range bomber (LRS-B) with low-observable technology.

The LRSO is therefore needed, STRATCOM commander Admiral Cecil Haney explained in June, to “effectively conduct global strike operations in the anti-access, access-denial environments.” When asked why they needed a standoff missile when they were building a stealth bomber, Haney acknowledge that “if you had all the stealth you could possibly have in a platform, then gravity bombs would solve it all.” But the stealth of the bomber will diminish over time because of countermeasures invented by adversaries, he warned. So “having standoff and stealth is very important” given how long the long-range bomber will operate into the future.

Lt. Gen. Stephen Wilson, the head of Air Force Global Strike Command, says the LRSO is needed to shoot holes in air defense systems.

Still, one could say that for any weapon and it doesn’t really explain what the nuclear mission is. But around the same time Admiral Haney made his statement, Air Force Global Strike Command commander General Wilson added a bit more texture: “There may be air defenses that are just too hard, it’s so redundant, that penetrating bombers become a challenge. But with standoff, I can make holes and gaps to allow a penetrating bomber to get in, and then it becomes a matter of balance.”

In this mission, the LRSO would not be used to keep the stealth bomber out of harms way per ce but as a nuclear sledgehammer to “kick down the door” so the bomber – potentially with B61-12 nuclear bombs in its bomb bay – could slip through the air defenses and get to its targets inside the country. Rather than deterrence, this is a real warfighting scenario that is a central element of STRATCOM’s Global Strike mission for the first few days of a conflict and includes a mix of weapons such as the B-2, F-22, and standoff weapons.

But why the sledgehammer mission would require a nuclear cruise missile is still not clear, as conventional cruise missiles have become significantly more capable against air defense and hard targets. In fact, most of the Global Strike scenarios would involve conventional weapons, not nuclear LRSOs. The Air Force has a $4 billion program underway to develop the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) and an extended-range version (JASSM-ER) for deliver by B-1B, B-2A, B-52H bombers and F-15E, F-16, and F-35 fighters. A total of 4,900 missiles are planned, including 2,846 JASSM-ERs.

The next-generation bomber will be equipped with non-nuclear weapons such as the Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) that will provide it with a standoff capability similar to the LRSO, although with shorter range.

Since the next-generation long-range bomber would also be the launch platform for those conventional weapons, it will be exposed to the same risks with or without a nuclear LRSO.

Most recently, according to the Nuclear Security & Deterrence Monitor, Gen. Wilson added another twist to the justification:

“If I take a bomber, and I put standoff cruise missiles on it, in essence, it becomes very much like a sub. It’s got close to the same magazine capacity of a sub. So once I generate a bomber with standoff cruise missiles, it becomes a significant deterrent for any adversary. We often forget that. It possesses the same firepower, in essence, as a sub that we can position whenever and wherever we want, and it becomes a very strong deterrent. So I’m a strong proponent of being able to modernize our standoff missile capability.”

Although the claim that a bomber has “close to the same capacity of a sub” is vastly exaggerated (it is up to 20 warheads on 20 cruise missiles on a B-52H bomber versus 192 warheads on 24 sea-launched ballistic missiles on an Ohio-class submarine), the example helps illustrates the enormous overcapacity and redundancy in the current arsenal.

What Kind of Missile?

Although we have yet to see what kind of capabilities the LRSO will have, the Air Force description is that LRSO “will be capable of penetrating and surviving advanced Integrated Air Defense Systems (IADS) from significant stand off range to prosecute strategic targets in support of the Air Force’s global attack capability and strategic deterrence core function.”

There is every reason to expect that STRATCOM and the Air Force will want the weapon to have better military capabilities than the current Air Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM), perhaps with features similar to the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM). After all, so the thinking goes, air defenses have improved significantly since the ALCM was deployed in 1982 and the LRSO will have to operate well into the middle of the century when air defense systems can be expected to be even better than today.

With a 3,000-km range similar to the ACM, the LRSO would theoretically be able to reach targets in much of Russia and most of China from launch-positions 1,000 kilometers from their coasts. Most of Russia and China’s nuclear forces are located in these areas.

In thinking about which capabilities would be needed for the LRSO, it is useful to recall the last time the warfighters argued that an improved cruise missile was needed. The ALCM was also “designed to evade air and ground-based defenses in order to strike targets at any location within any enemy’s territory,” but that was not good enough. So the Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM) was developed and deployed in 1992 to provide “significant improvements” over the ALCM in “range, accuracy, and survivability.” The rest of the mission was similar – “evade air and ground-based defenses in order to strike heavily defended, hardened targets at any location within any enemy’s territory” – but the requirement to hold at risk “heavily defended, hardened targets” was unique.

Yet when comparing the ALCM and ACM mission requirements and capabilities with the operational experience, GAO in 1993 found that “air defense threats had been overestimated” and that “tests did not demonstrate low ALCM survivability.” The ACM’s range was found to be “only slightly better than the older ALCM’s demonstrated capability,” and GAO concluded that “the improvement in accuracy offered by the ACM appears to have little real operational significance.”

The ACM was produced at great cost to provide improved targeting capabilities over the ALCM but apparently had little operational significance and was retired early in 2007. Will LRSO repeat the mistake?

Nonetheless, the ACM was produced in 1992-1993 at a cost of more than $10 billion. Strategic Air Command initially wanted 1461 missiles, but the high cost and the end of the Cold War caused Pentagon to cut the program to only 430 missiles. A sub-sonic cruise missile with a range of 3,000 kilometers (1,865 miles) and hard-target kill capability with the W80-1 warhead, the ACM was designed for external carriage on the B-52H bomber, with up to 12 missiles under the wings. The B-2 was also capable of carrying the ACM but as a penetrating stealth bomber there was never a need to assign it the stealthy standoff missile as well.

The ACM was supposed to undergo a life extension program to extend it to 2030, but after only 15 years of service the missile was retired early in 2007. An Enhanced Cruise Missile (ECM) was planned by the Bush administration, but it never materialized. It is likely, but still not clear, that LRSO will make use of some of the technologies from the ACM and ECM programs.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The W80-1 warhead has been selected to arm the new Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) missile, a $10-20 billion weapon system the Air Force plans to deploy in the late-2020s but can poorly afford.

Even though the United States has thousands of nuclear warheads on land- and sea-based ballistic missiles that can reach the same targets intended for the LRSO, the military argues that a new nuclear standoff weapon is needed to spare a new penetrating bomber from enemy air-defense threats.

Yet the same bomber will be also equipped with conventional weapons – some standoff, some not – that will expose it to the same kinds of threats anyway. So the claim that the LRSO is needed to spare the next-generation bomber from air-defense threats sounds a bit like a straw man argument.

The mission for the LRSO is vague at best and to the extent the Air Force has described one it sounds like a warfighting mission from the Cold War with nuclear cruise missiles shooting holes in enemy air defense systems. Given the conventional weapon systems that have been developed over the past two decades, it is highly questionable whether such a mission requires a nuclear cruise missile.

The Air Force has a large inventory of W80-1 warheads. Nearly 2,000 were built, 528 are currently used on the ALCM, and hundreds are in storage at the Kirtland Underground Maintenance and Munitions Storage Complex (KUMMSC) near Kirtland AFB in New Mexico.

The warfighters and the strategists might want a nuclear cruise missile as a flexible weapon for regional scenarios. But good to have is not the same as essential. And the regional scenarios they use to justify it are vague and largely unknown – certainly untested – in the public debate.

In the nuclear force structure planned for the future, the United States will have roughly 1,500 warheads deployed on land- and sea-based ballistic missiles. Nearly three-quarters of those warheads will be onboard submarines that can move to positions off adversaries anywhere in the world and launch missiles that can put warheads on target in as little as 15 minutes.

It really stretches the imagination why such a capability, backed up by nuclear bombs on bombers and the enormous conventional capability the U.S. military possesses, would be insufficient to deter or dissuade any potential adversary that can be deterred or dissuaded.

As the number of warheads deployed on land- and sea-based ballistic missiles continues to drop in the future, long-range, highly accurate, stealthy, standoff cruise missiles will increasingly complicate the situation. These weapons are not counted under the New START treaty and if a follow-on treaty does not succeed in limiting them, which seems unlikely in the current political climate, a new round of nuclear cruise missile deployments could become real spoilers. There are currently more ALCMs than ICBMs in the U.S. arsenal and with each bomber capable of loading up to 20 missiles the rapid upload capacity is considerable.

Under the 1,500 deployed strategic warhead posture of the New START treaty, the unaccounted cruise missiles could very quickly increase the force by one-third to 2,000 warheads. Under a posture of 1,000 deployed strategic warheads, which the Obama administration has proposed for the future, the effect would be even more dramatic: the air-launched cruise missiles could quickly increase the number of deployed warheads by 50 percent. Not good for crisis stability!

As things stand at the moment, the only real argument for the new cruise missile seems to be that the Air Force currently has one, but it’s getting old, so it needs a new one. Add to that the fact that Russia is also developing a new cruise missile, and all clear thinking about whether the LRSO is needed seems to fly out the window. Rather than automatically developing and deploying a new nuclear cruise missile, the administration and Congress need to ask tough questions about the need for the LRSO and whether the money could be better spent elsewhere on non-nuclear capabilities that – unlike a nuclear cruise missile – are actually useful in supporting U.S. national and international security commitments.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New START: Russia and the United States Increase Deployed Nuclear Arsenals

Three and a half years after the New START Treaty entered into force in February 2011, many would probably expect that the United States and Russia had decisively reduced their deployed strategic nuclear weapons.

On the contrary, the latest aggregate treaty data shows that the two nuclear superpowers both increased their deployed nuclear forces compared with March 2014 when the previous count was made.

Russia has increased its deployed weapons the most: by 131 warheads on 23 additional launchers. Russia, who went below the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads in 2013, is now back above the limit by 93 warheads. And Russia is now counted – get this – as having more strategic warheads deployed than when the treaty first went into force in February 2011!

Before arms control opponents in Congress get their banners out, however, it is important to remind that these changes do not reflect a build-up the Russian nuclear arsenal. The increase results from the deployment of new missiles and fluctuations caused by existing launchers moving in and out of overhaul. Hundreds of Russian missiles will be retired over the next decade. The size of the Russian arsenals will most likely continue to decrease over the next decade.

Nonetheless, the data is disappointing for both nuclear superpowers – almost embarrassing – because it shows that neither has made substantial reductions in its deployed nuclear arsenal since the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011.

The meager performance is risky in the run-up to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in April 2015 where the United States and Russia – together with China, Britain, and France – must demonstrate their progress toward nuclear disarmament to ensure the support of the other countries that have signed the NPT in strengthening the non-proliferation treaty regime.

Russian Deployments

The data for Russia is particularly interesting because it now has 106 warheads more deployed than when the New START Treaty went into force in February 2011. The number of deployed launchers is exactly the same: 106.

This does not mean that Russia is in the middle of a nuclear arms build-up; over the next decade more than 240 old Soviet-era land- and sea-based missiles are scheduled to be withdrawn from service. But the rate at which the older missiles are withdrawn has been slowing down recently from about 50 missiles per year before the New START treaty to about 22 missiles per year after New START. The Russian military wants to retire all the old missiles by the early 2020s, so the current rate will need to pick up a little.

At the same time, the rate of introduction of new land-based missiles to replace the old ones has increased from approximately 9 missiles per year to about 18. The net effect is that the total missile force and warheads deployed on it have increased slightly since 2013.

The new deployments include the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) ICBM, of which the first two regiments with 18 mobile missiles were put in service with the Teykovo division in 2010-2012, replacing SS-25s (Topol) previously there. Deployment followed in late-2013 at the Novosibirsk and Nizhniy Tagil divisions, each of which now has one regiment for a total of 36 RS-24s. This number will grow to 54 missiles by the end of this year because the two divisions are scheduled to receive a second regiment. And because each RS-24 carries an estimated 4 warheads (compared with a single warhead on the SS-25), the number of deployed warheads has increased.

Introduction of the SS-27 Mod (RS-24) road-mobile ICBM is underway at the 42nd Missile Division at Nizhniy Tagil in central Russia. Click to see full size image.

Also underway is the deployment of SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) in silos at the Kozelsk division, where they are replacing old SS-19s. The first regiment of 10 RS-24s was scheduled to become operational by the end of this year but appears to have fallen behind schedule with only 4 missiles expected. It has not been announced how many missiles are planned for Kozelsk but it might involve 6 regiments with a total of 60 missiles (a similar number of SS-27 Mod 1s (Topol-M) were installed at Tatishchevo between 1997 and 2013). Since each RS-24 carries 4 warheads compared with the 6 on the SS-19, the number of silo-based warheads will decrease over the next decade.

Another reason for the increase in the latest New START data is probably the long-awaited introduction of the new Borei-class of ballistic missile submarines. The precise loadout status of the first submarines is uncertain, but the first might have been partially or fully loaded by now. The first two boats (Yuri Dolgoruy and Alexander Nevsky) entered service in late-2013 but have been without missiles because of the troubled test-launch performance of their missile (SS-N-32, Bulava), which has failed about half of its test launched since 2005. After fixes were made, a successful launch took place on September 10 from the third Borei SSBN, the Vladimir Monomakh. The Yuri Dolgoruy is scheduled to conduct an operational launch later this month. A total of 8 Borei SSBNs are planned, each with 16 Bulavas, each with 6 warheads, for a total of nearly 100 warheads per boat.

A new Borei-class SSBN at missile loading pier by the Okolnaya SLBM Deport at Severomorsk on the Kola Peninsula. Click to see full size image.

United States

For the United States, the data shows that the number of warheads deployed on strategic missiles increased slightly since March, by 57 warheads from 1,585 to 1,642. The number of deployed launchers also increased, by 16 from 778 to 794.

The reason for the U.S. increase is not an actual increase of the nuclear arsenal but reflects fluctuations caused by the number of launchers in overhaul at any given time. The biggest effect is caused by SSBNs loading or offloading missiles, most importantly the return to service of the USS West Virginia (SSBN-736) after a refueling overhaul with a load of 24 missiles and approximately 100 warheads.

More details will be come available in December when the State Department is expected to release the detailed unclassified breakdown of the U.S. aggregate data for October.

Overall, however, the U.S. performance under the treaty is better than that of Russia because the data shows that the United States has actually reduced its deployed force structure since 2011: by 158 warheads and 88 launchers. In addition, the U.S. military has also destroyed 124 non-deployed launchers including empty silos and retired bombers.

The better U.S. performance does not indicate that the Pentagon has embarked upon a program of unilateral disarmament. Rather, it reflects that the U.S. nuclear forces structure is much larger than that of Russia and that the U.S. therefore has more work to do before the treaty enters into effect in February 2018.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The increase in Russian and U.S. deployed strategic nuclear weapons shown by New START aggregate data is disappointing because it illustrates the degree to which the two nuclear superpowers are holding on to excessively large nuclear arsenals. While there is no doubt that the two countries will eventually implement the treaty by 2018, they have been exceedingly slow in doing so.

The fact that Russia now has more warheads deployed than when the treaty first entered into force in 2011 is particularly disappointing. And it illustrates just how modest the New START Treaty is.

The increase in U.S. deployed warheads and launchers is also disappointing especially when considering that the Nuclear Employment Strategy issued by the White House in June 2013 concluded that the United States has one-third more strategic nuclear weapons deployed than it needs to fulfill its national and international security commitments.

The United States currently has 273 deployed strategic launchers more than Russia, as well as a reserve of several thousand non-deployed warheads that are not counted by the treaty but intended to increase the loadout on the launchers if necessary.

Faced with the planned retirement of Soviet-era missiles within the next decade, Russia appears to be compensating for the disparity by accelerating deployment of new land-based missiles with multiple warheads to maintain parity with the larger U.S. missile force structure.

Russia and the United States each has over four times more nuclear weapons than all the seven other nuclear-armed states in the world – combined! Clearly, the large Russian and U.S. arsenals exist in a bubble justified predominantly by the large size of the other’s arsenal.

Russia and the United States need to do more to reduce their nuclear arsenals faster. The lackluster performance in implementing and following up on the New START Treaty, as well as the extensive nuclear weapons modernization underway in both countries, mean that the two nuclear superpowers will have very little to show at next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in New York to demonstrate how they are meeting their obligations and promises made under the treaty to reduce and eventually eliminate nuclear weapons.

Neither Russia nor the United States can afford the expensive nuclear weapon modernization programs currently underway to sustain their large arsenals. And they certainly cannot afford to weaken the support of the non-proliferation treaty regime in strengthening efforts to halt and curtail the proliferation of nuclear weapons.

More Background Information:

• “Russian Nuclear Weapons Modernization: Status, Trends, and Implications,” briefing to Foundation pour la Recherche Stratégique, Paris, September 29, 2014;

• “Russian ICBM Force Modernization: Arms Control Please!,” FAS Strategic Security Blog, May 7, 2014;

• FAS Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Forces, 2014, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January 2014.

See also Pavel Podvig’s analysis.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russia Declared In Violation Of INF Treaty: New Cruise Missile May Be Deploying

A Russian GLCM is launched from an Iskander-K launcher at Kapustin Yar in 2007.

The United States yesterday publicly accused Russia of violating the landmark 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

The accusation was made in the State Department’s 2014 Compliance Report, which states:

“The United States has determined that the Russian Federation is in violation of its obligations under the INF Treaty not to possess, produce, or flight-test a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) with a range capability of 500 km to 5,500 km, or to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.”

The Russian violation of the INF is, if true, a very serious matter and Russia must immediately restore its compliance with the Treaty in a transparent and verifiable manner.

Rumors about a violation have swirled around Washington (and elsewhere) for a long time. Apparently, the GLCM was first launched in 2007 (see image to the left), so why the long wait?

The official accusation it is likely to stir up calls for the United States to abandon the INF Treaty and other arms control efforts. Doing so would be a serious mistake that would undercut benefits from existing and possible future agreements. Instead the United States should continue to adhere to the treaty, work with the international community to restore Russian compliance, and pursue additional measures to reduce nuclear dangers worldwide.

What Violation?

The unclassified Compliance Report doesn’t specify the Russian weapon system that it concludes constitutes a violation of the INF Treaty. Nor does it specify when the violation occurred. The classified version and the briefings that the Obama administration has given Congress and European allies presumably are more detailed. All the Compliance Report says is that the violation concerns a GLCM with a range of 310 miles to 3,400 miles (500 km to 5,500 km).

While public official identification is still pending, news media reports and other information indicate that the violation possibly concerns the Iskander-K weapon system, a modification of the Iskander launcher designed to carry two cruise missiles instead of two SS-26 Iskander-M ballistic missiles.

[UPDATE December 2014: US Undersecretary of State Rose Gottemoeller helpfully removes some of the uncertainty: “It is a ground-launched cruise missile. It is neither of the systems that you raised. It’s not the Iskander. It’s not the other one, X-100 [sic; X-101].” And the missile “is in development.”

The cruise missile apparently was first test-launched at Kapustin Yar in May 2007. Russian news media reports at the time identified the missile as the R-500 cruise missile. Sergei Ivanov was present at the test and Vladimir Putin confirmed that “a new cruise missile test” had been carried out.

Public range estimates vary tremendously. One report claimed last month that the range of the R-500 is 1,243 miles (2,000 km), while most other reports give range estimates from 310 miles (500 km) and up. Images on militaryrussia.ru that purport to show the R-500 GLCM 2007-test show dimensions very similar to the SS-N-21 SLCM (see comparison below).

Images on militaryrussia.ru that purport to show the R-500 GLCM 2007-test show dimensions very similar to the SS-N-21 SLCM

The wildly different range estimates might help explain why it took the U.S. Intelligence Community six years to determine a treaty violation. A State Department spokesperson said yesterday that the Obama administration “first raised this issue with Russia last year. ”The previous Compliance Report from 2013 (data cut-off date December 2012) did not call a treaty violation, and the 2013 NASIC report did not mention any GLCM at all.

So either there must have been serious disagreements and a prolonged debate inside the Intelligence Community about the capability of the GLCM. Or the initial flight tests did not exceed 310 miles (500 km) and it wasn’t until a later flight test with an extended range – perhaps in 2012 or 2013 – exceeded the INF limit that a violation was established. Obviously, much uncertainty remains.

Deployment Underway at Luga?

The Compliance Report, which covers through December 2013, does not state whether the GLCM has been deployed and one senior government official consulted recently did not want to say. And the New York Times in January 2014 quoted an unnamed U.S. government official saying the missile had not been deployed.

But since then, important developments have happened. Last month, Russian defense minister Sergei Shuigu visited the 26 Missile Brigade base near Luga south of Saint Petersburg, approximately 75 miles (120 km) from the Russian-Estonian border. A report of the visit was posted on the Russian Ministry of Defense’s web site on June 20th.

The report describes introduction of the Iskander-M ballistic missile weapon system at Luga, a development that has been known for some time. But it also contains a number of photos, one of which appears to show transfer of an Iskander-K cruise missile canister between two vehicles.

The fact that the Russian MOD report shows both what appears to be the Iskander-M and the Iskander-K systems is interesting because images from another visit by defense minister Shuigo to the 114th Missile Brigade in Astrakhanskaya Oblast in June 2013 also showed both Iskander-M and Iskander-K. During that visit, Shoigu said that Iskander was delivered in a complete set, rather than “piecemeal” as done before. That could indicate that the Iskander units are being equipped with both the Iskander–M ballistic missile and Islander-K cruise missile, and that Luga is the first western missile brigade to receive them.

A satellite image from April 9, 2014, shows significant construction underway at the Luga garrison that appears to include missile storage buildings and launcher tents for the Iskander weapon system (see image below). The base is upgrading from the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) short-range ballistic missile.

Construction underway at the 26th Missile Brigade base near Luga show what appear to include missile storage buildings and launcher tents for the Iskander weapon system.

The eight garage-tents that are visible on the satellite photo also appear on the ground photos the Russian MOD published of defense minister Shuigo’s visit to Luga. The garages are in two groups bent in a slight angle that is also visible one of the ground photos (see middle photo of collage below).

Earlier this month, the acting commander of the western military district told Interfax that infrastructure to house the missiles is being built at the base where they will be stationed. And Russian news media reported that the first of the three Missile Battalions at Luga had completed training and the Iskander was accepted for service on July 8, 2014. The remaining two Battalions will complete training in September, at which time the 26th Missile Brigade is scheduled to conduct a launch exercise in the western military district.

What the Report Doesn’t Say

Troubling as the alleged INF violation is, the Compliance Report also brings some good news by way of what it doesn’t say.

For example, the Compliance Report does not say that any Russia ballistic missiles violate the INF. Some speculated last year that Russia’s development of a new long-range ballistic missile – the RS-26, a modified version of the RS-24 (SS-27 Mod 2) intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – was a violation because it was test-flown at less than 5,500 km. I challenged that at the time and the 2013 NASIC report clearly listed the “new ICBM” with a range of more than 5,500 km. The Compliance Report indirectly confirms that Russian longer-range ballistic missiles have not been found to be in violation of the INF.

Nor does the Compliance Report declare any shorter-range ballistic missiles – such as the SS-26 Iskander-M – to be in violation of the treaty. This is important because there have been rumors that the Iskander-M might have a range of 310 miles (500 km) or more.

As such, the Compliance Repot helpfully confirms indirectly that the Iskander-M range must be less than 310 miles (500 km). This conclusion matches the 2013 NASIC report, which lists the Iskander-M (SS-26) range as 186 miles (300 km).

The report also indirectly lay to rest rumors that the violation might have involved a sea-launched cruise missile that was test-launched on land.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The alleged Russian violation of the INF treaty is serious stuff that calls into question Russia’s status as a trustworthy country. That status has already taken quite a few hits recently with the annexation of Crimea and the proxy-war in eastern Ukraine. But it’s one thing for a country to withdraw from a treaty because it’s deemed no longer to serve national security interests; it’s quite another to cheat while pretending to abide by it.

That’s why the U.S. accusation is so serious that Russia has violated the terms of the 1987 INF Treaty by producing, flight-testing, and possessing a GLCM with a range of more than 310 miles (500 km). Unfortunately, the lack of details in the unclassified report will leave the public guessing about what the violation is and enable Russian officials to reject the accusation (at least in public) as unsubstantiated.

Shortly after the 2007 flight-test of the GLCM now seen as violating the INF, President Putin warned that it would be difficult for Russia to adhere to the INF Treaty if other countries developed INF weapons. He didn’t mention the countries but Russian defense experts said he meant China, India, and Pakistan.

By that logic, one would have expected Russia’s first deployment of Iskander-K and its GLCM to be in eastern or central Russia. Instead, the first deployment appears to be happening at Luga in the western military district, even though the United States no longer has GLCMs deployed in Europe.

There is a real risk that Russia will now formally withdraw from the INF Treaty. Doing so would be a serious mistake. First, it is because of the INF Treaty that Russia no longer faces quick-strike INF missiles in Europe. Moreover, continuing the INF treaty is Russia’s best hope of achieving some form of limitations on other countries’ INF weapons. But instead of trying to sell INF limitations to China and India, Putin has been busy selling them advanced weapons, including cruise missiles.

In the meantime, Russia must restore its compliance with the INF Treaty in a transparent a verifiable manner. Doing anything else will seriously undermine Russia’s international status and isolate it at next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference.

Some will use Russia’s alleged INF violation to argue that the United States should withdraw from the INF treaty and abandon other arms control initiatives because Russia cannot be trusted. But the treaty has served its purpose well and it is in the U.S. and European interest to maintain and promote its norms to the extent possible. Besides, the United States and NATO have plenty of capability to offset any military challenge a potential widespread Russian GLCM deployment might pose.

Moreover, arms control treaties, such as the New START Treaty or future agreements, can have significant national security benefits by allowing the United Stated and its allies better confidence in monitoring the status and development of Russian strategic nuclear forces. For arms control opponents to use the INF violation to prevent further reductions of nuclear weapons that can otherwise hit American and allied cities seems downright irresponsible.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Italy’s Nuclear Anniversary: Fake Reassurance For a King’s Ransom

A new placard at Ghedi Air Base implies that U.S. nuclear weapons stored at the base have protected “the free nations of the world” after the end of the Cold War. But where is the evidence?

By Hans M. Kristensen

In December 1963, a shipment of U.S. nuclear bombs arrived at Ghedi Torre Air Base in northern Italy. Today, half a century later, the U.S. Air Force still deploys nuclear bombs at the base.

The U.S.-Italian nuclear collaboration was celebrated at the base in January. A placard credited the nuclear “NATO mission” at Ghedi with having “protected the free nations of the world….”

That might have been the case during the Cold War when NATO was faced with an imminent threat from the Soviet Union. But half of the nuclear tenure at Ghedi has been after the end of the Cold War with no imminent threat that requires forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Instead, the nuclear NATO mission now appears to be a financial and political burden to NATO that robs its armed forces of money and time better spent on non-nuclear missions, muddles NATO’s nuclear arms control message, and provides fake reassurance to eastern NATO allies.

Italian Nuclear Anniversary

Neither the U.S. nor Italian government will confirm that there are nuclear weapons at Ghedi Torre Air Base. The anniversary placard doesn’t even include the word “nuclear” but instead vaguely refers to the “NATO mission.”

But there are numerous tell signs. One of the biggest is the presence of the 704th Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS), a U.S. Air Force unit of approximately 134 personnel that is tasked with protecting and maintaining the 20 U.S. B61 nuclear bombs at the base. The MUNSS would not be at the base unless there were nuclear weapons present. There are only four MUNSS units in the U.S. Air Force and they’re all deployed at the four European bases where U.S. nuclear weapons are earmarked for delivery by aircraft of the host nation.

A satellite photo from March this year shows part of the nuclear infrastructure at Ghedi Torre Air Base. Click on image to see full size.

Another tell sign is the presence of NATO Weapons Maintenance Trucks (WMT) at Ghedi. NATO has 12 of these trucks that are specially designed to enable field service of nuclear bombs at the storage bases in Europe. A satellite image provided by Digital Globe via Google Earth shows a WMT parked near the 704th MUNSS quarters at Ghedi on March 12, 2014. An older image from September 28, 2009, shows two WMTs at the same location (see image above).

These trucks will drive out to the 11 individual Protective Aircraft Shelters (PAS) that are equipped with underground Weapons Storage and Security System (WS3) vaults to service the B61 bombs. The WS3 vaults at Ghedi were completed in 1997; before that the weapons were stored in bunkers outside the main base. Once the truck is inside the shelter, the B61 is brought up from the vault, disassembled into its main sections as needed, and brought into the truck for service.

It is during this process of weapon disassembly when the electrical exclusion regions of the nuclear bomb are breached that a U.S. Air Force safety review in 1997 warned that “nuclear detonation may occur” if lightning strikes the shelter.

NATO is in the process of replacing the WMTs with a fleet of new nuclear weapons maintenance trucks known as the Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS). The trailers will have improved lightning protection. NATO provided $14.7 million for the program in 2011, and in July 2012 the U.S. Air Force awarded a $12 million contract to five companies in the United States to build 10 new STMS trailers for delivery by June 2014.

NATO’s new mobile nuclear weapons maintenance system is scheduled for delivery to European nuclear bases in 2014. Click image to see full size.

The new trailers will be able to handle the new B61-12 guided standoff nuclear bomb that is planned for deployment in Europe from 2020. The B61-12 apparently will be approximately 100 lbs pounds (~45 kilograms) heavier than the existing B61s in Europe (see slide below) – even without the internal parachute. This suggests that a fair amount of new or modified components will be added. To better handle the heavier B61-12, each trailer will be equipped with hoist rails.

The new B61-12 bomb will be heavier than the B61s currently deployed in Europe. For pictures of actual B61-12 features, click here.

The deployment to Ghedi 50 years ago was not the earliest or only deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons to Italy. During the Cold War, ten different U.S. nuclear weapon systems were deployed to Italy. The first weapons to arrive were Corporal and Honest John short-range ballistic missiles in August 1956. They were followed by nuclear bombs in April 1957 and nuclear land mines in 1959. All but one – nuclear bombs – of these nuclear weapon systems have since been withdrawn and scrapped.

A decade ago, most B61s in Europe were stored in Germany and the United Kingdom, but today, Italy has the honor of being the NATO country with the most U.S. nuclear weapons deployed on its territory; a total of 70 of all the 180 B61 bombs remaining in Europe (39 percent). Italy is also the only country with two nuclear bases: the Italian base at Ghedi and the American base at Aviano. Aviano Air Base is home to the U.S. 31st Fighter Wing with two squadrons of nuclear-capable F-16 fighter-bombers. One of these, the 555th Fighter Squadron, was temporarily forward deployed to Lask Air Base in Poland in March 2014.

The nuclear “NATO mission” that the 6th Stormo wing at Ghedi Torre Air Base serves means that Italian Tornado aircraft are equipped and Italian Tornado pilots are trained in peacetime to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons in wartime. This arrangement dates back to before the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), but it is increasingly controversial because Italy as a signatory to the NPT has pledged “not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons…or of control over such weapons…directly, or indirectly.”

The United States, also a signatory to the NPT, has committed “not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons…or control over such weapons…directly, or indirectly; and not in any way to assist, encourage, or induce any non-nuclear-weapon State to…acquire nuclear weapons…, or control over such weapons….”

In peacetime, the B61 nuclear bombs at Ghedi are under the custody of the 704th MUNSS, but the whole purpose of the NATO mission is to equip, train and prepare in peacetime for “transfer” and “control” of the U.S. nuclear bombs to the Italian air force in case of war.

The Nuclear Burden

Maintaining the NATO nuclear strike mission in Europe does not come cheap or easy but “steals” scarce resources from non-nuclear military capabilities and operations that – unlike tactical nuclear bombs – are important for NATO.

Italy pays for the basing of the U.S. Air Force 704th MUNSS at Ghedi, for security upgrades needed to protect the weapons at the base, and for training pilots and maintaining Tornado aircraft to meet the stringent certification requirements for nuclear strike weapons. Moreover, the cost of securing the B61 bombs at the European bases is expected to more than double over the next few years (to $154 million) to meet increased U.S. security standards for storage of nuclear weapons.

But these costs are getting harder to justify given the serious financial challenges facing Italy. The air force’s annual flying hours dropped form 150,000 in 1990 to 90,000 in 2010, training reportedly declined by 80 percent from 2005 to 2011, and training for air operations other than Afghanistan apparently has been “pared to the bone.” In addition, the Italian defense posture is in the middle of a 30-percent contraction of the overall operational, logistical and headquarters network spending. The F-35 fighter-bomber program, part of which is scheduled to replace the current fleet of Tornados in the nuclear strike mission, has already been cut by a third and the new government has signaled its intension to cut the program further.

Under such conditions, maintaining a nuclear mission for the Italian air force better be really important.

Most of the costs of the European nuclear mission are carried by the United States. Over the next decade, the United States plans to spend roughly $10 billion to modernize the B61 bomb, over $1 billion more to make the new guided B61-12 compatible with four existing aircraft, another $350 million to make the new stealthy F-35 fighter-bomber nuclear-capable, and another $1 billion to sustain the deployment in Europe.

This adds up to roughly $12.5 billion for sustaining, securing, and modernizing U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe over the next decade. Whether the price tag is worth it obviously must to be weighed against the security benefits it provides to NATO, how well the deployment fits with U.S. and NATO nuclear arms control policy, and whether there are more important defense needs that could benefit from that level of funding.

Fake Versus Real Reassurance

The anniversary placard displayed at Ghedi Air Base claims that the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs have “protected the free nations of the world” even after the end of the Cold War. And during the nuclear safety exercise at Ghedi in January, the commander of the U.S. Air Force 52nd Fighter Wing told the U.S. and Italian security forces that “your mission today is still as relevant as when together our country stared down the Soviet Union alongside a valued member of our enduring alliance.” (Emphasis added).

That is probably an exaggeration, to put it mildly. In fact, it is hard to find any evidence that the deployment of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe after the end of the Cold War has protected anything or that the mission is even remotely as relevant today. The biggest challenge today seems to be to protect the weapons and to find the money to pay for it.

NATO’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, moreover, strongly suggests that NATO itself does not attribute any real role to the non-strategic nuclear weapons in reassuring eastern NATO allies of a U.S. commitment to defend them. Yet this reassurance role is the main justification used by proponents of the deployment. In hindsight, the reassurance effect appears to be largely doctrine talk, while NATO’s actual response has focused on non-nuclear forces and exercises.

To the extent that a potential nuclear card has been played, such as when three B-52 and two B-2 nuclear-capable bombers were temporarily deployed to England earlier this month, it was done with long-range strategic bombers, not tactical dual-capable aircraft. The fact that nuclear fighter-bombers were already in Europe seemed irrelevant. The same was done in March 2013, when the United States deployed long-range bombers over Korea to reassure South Korea and Japan against North Korean threats.

No eastern European ally has said: “Hold the bombers, hold the paratroopers, hold the naval exercises! The B61 nuclear bombs in Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Turkey are here to reassure us against Russia.”

In the real world, the non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe are fake reassurance because they are useless and meaningless for the kind of crises that face NATO allies today or in the foreseeable future. NATO pays a king’s ransom for the deployment with very little to show for it.

President Obama has asked for $1 billion to reassure Europe against Russia. But he could get a dozen non-nuclear European Reassurance Initiatives for the price of sustaining, modernizing, and deploying the non-strategic nuclear bombs in Europe. Doing so would help “put an end to Cold War thinking” as he promised in Prague five years ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Exercises Amidst Ukrainian Crisis: Time For Cooler Heads

A Russian Tu-95MS long-range bomber drops an AS-15 Kent nuclear-capable cruise missiles from its bomb bay on May 8th. Six AS-15s were dropped from the bomb bay that day as part of a Russian nuclear strike exercise.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Less than a week after Russia carried out a nuclear strike exercise, the United States has begun its own annual nuclear strike exercise.

The exercises conducted by the world’s two largest nuclear-armed states come in the midst of the Ukraine crisis, as NATO and Russia appear to slide back down into a tit-for-tat posturing not seen since the Cold War.

Military posturing in Russia and NATO threaten to worsen the crisis and return Europe to an “us-and-them” adversarial relationship.

One good thing: the crisis so far has demonstrated the uselessness of the U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

Different Styles, Different Messages

Vladimir Putin’s televised commanding of the nuclear strike exercise – flanked by the presidents of Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the Russian National Defense Command Center – made one thing very clear: Putin wanted to showcase his nuclear might to the world. Russian military news media showed the huge displays in the Command Center with the launch positions and impact areas of long-range nuclear missiles launched from a road-mobile launchers and ballistic missile submarines.

A map in the National Defense Command Center shows the launch points and impact areas of nuclear missiles launched across Russia. Click to see larger version.

Other displays and images on the Russian Internet showed AS-15 Kent (Kh-55) nuclear cruise missiles launched from a Tu-95 “Bear” bomber (six missiles were launched), short-range ballistic missiles, and air-defense and ballistic missile defense interceptors reportedly repelled a “massive rocket nuclear strike” launched against Russia by “a hypothetical opponent.”

Of course everything was said to work just perfectly but there is no way to known how well the Russian forces performed, how realistic the exercise was designed to be, or what was different compared with previous exercises. Russia conducts these exercises each year and Russian military planners love to launch a lot of rockets very quickly with lots of smoke and noise (it looks impressive on television). But the exercise looked more like a one-day snap intended to showcase test launching of offensive and defensive forces rather than a significant new development.

The STRATCOM announcement of the Global Lightning exercise was, in contrast, much more timid, so far limited to a single press release. Mindful of the problematic timing, the press release said the timing was “unrelated to real-world events” and that the exercise has been planned for more than a year. But some new stories nonetheless linked the two events.

The STRATCOM press release didn’t say much about the exercise scenario or what forces would be involved. Only bombers – whose operations are highly visible and would probably be noticed anyway – were mentioned: 10 B-52 and up to six B-2 bombers. But SSBNs and ICBMs also participate in Global Lightning (although not with live test launches as in the Russian exercise) as well as refueling tankers and command and control units.

As its main annual strategic nuclear command post/field training exercise, STRATCOM uses Global Lightning to verify the readiness and effectiveness of U.S. nuclear forces and practice strike scenarios from OPLAN 8010-12 and other war plans against potential adversaries. Last updated in June 2012, OPLAN 8010-12 is being adjusted to incorporate decisions from the Obama administration’s June 2013 nuclear weapons employment strategy.

Although STRATCOM has only mentioned bombers participating in the Global Lightning 14 exercise, SSBNs and ICBMs also participate. This picture shows a V-22 Osprey delivering supplies to USS Louisiana (SSBN-424) during operations in the Pacific in 2012.

The previous Global Lightning exercise was held in 2012 (Global Lightning 2013 was canceled due to budget cuts) and is normally accompanied or followed by other nuclear-related exercises such as Global Thunder, Vigilant Shield, and Terminal Fury. In addition to strategic nuclear planning, STRATCOM supports regional nuclear targeting as well. The 2012 Global Lightning exercise supported Pacific Command’s Terminal Fury exercise in the Pacific and included several crisis and time-sensitive strike scenarios against extremely difficult target sets never seen before in Terminal Fury.

Back to Us and Them

One can read a lot into the exercises, if one really wants to. And some commentators have suggested that the exercises were deliberately intended as reminders to “the other side” of the Ukrainian crisis about the horrific military destructive power each side possesses.

I don’t think the Russian exercise or the U.S. Global Lightning exercise are directly linked to the Ukrainian crisis; they were planned long in advance. Nuclear weapons – and fortunately so – seem completely out of proportion to the circumstances of the situation in Ukraine.

Nonetheless, they do matter in the overall east-west sparing and the fact that the national leadership of Russia and the United States authorized these nuclear exercises at this particular time is a cause for concern. It is the first time nuclear forces have been rattled during the Ukrainian crisis. And because they are nuclear, the exercises add important weight to a pattern of increasingly militaristic behaviors on both sides.

Russia’s invasion of Crimea – bizarrely coinciding with Russia celebrating its defeat of a different invasion of the Soviet Union 73 years ago – to prevent loosing its Black Sea fleet area to an increasingly westerly looking Ukraine, and NATO responding by beefing up its military posture in Eastern Europe far from Ukraine to demonstrate “that NATO is prepared to meet and deter any threat to our alliance” – even though there are no signs of an increased Russian military threat against NATO territory in general – ought to have caused political leaders on both sides to delay the nuclear exercises to avoid fueling crisis sentiments and military posturing any further.

Instead, both sides now seem determined to stick to their guns and overturn the budding partnership and trust that had emerged after the Cold War. In doing so, the danger is, of course, that the military institutions on both sides are allowed to dominate the official responses to the crisis and deepen it rather than de-escalating and resolving it. No doubt, military hawks and defense contractors on both sides see an opportunity to use the Ukrainian crisis to get the defense budgets and weapons they have wanted for years but been unable to get because of budget cuts and the absence of a significant military “threat.”

A French Mirage follows a Russian Tu-22M3 Backfire bomber over the Baltic Sea in June 2013. Three months earlier, two Russian Tu-22M3s escorted by four Su-27 Flanker fighters simulated a nuclear attack on two targets in Sweden.

Russia has already announced plans to add 30 warships to the Black Sea Fleet and widen deployment of navy and air forces to four additional bases in Crimea.

The Russian air force has resumed long-range training flights with nuclear aircraft and often violates the air space of other countries. In March 2013, two Tu-22M3 backfire bombers reportedly simulated a nuclear strike against two targets in Sweden (although the aircraft did not violate Swedish air space at that time).

It is almost inevitable that increased NATO deployments and defense budgets in eastern member countries will trigger Russian military counter-steps closer to NATO borders. One of the first tell signs will be the Zapad exercise later this fall.

For its part, NATO has already deployed ships, aircraft, and troops to Eastern European countries and is considering how to further change its defense planning to respond with “air, land and sea ’reassurances’” to “a different paradigm, a different rule set” (translation: Russia is now an official military threat), according to NATO’s military commander General Philip Breedlove and “position those ‘reassurances’ across the breadth of our exposure: north, center, and south.”

NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen echoed Breedlove’s defense vision during a visit to Estonia on May 1st, saying the Ukrainian crisis had triggered a NATO response where “aircraft and ships from across the Alliance are reinforcing the security from the Baltic to the Black Sea.”

Breedlove and Rasmussen paint a military response that appears to go beyond the Ukrainian crisis itself and involve a broad reinforcement of NATO’s eastern areas. Breedlove got NATO approval for the initial deployments and exercises seen in recent weeks, but the defense ministers meeting in Brussels in June likely will prepare more fundamental changes to NATO military posture for approval at the NATO Summit in Wales in September.

General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen and other NATO officials describe a broad military reinforcement across NATO in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel says requires NATO countries to increase their defense budgets.

Among other aspects, those changes will probably involve modifying NATO’s General Intelligence Estimate (MC 161) and NATO Ministerial Guidance to explicitly identify Russia, once again, as a potential threat. Doing so will open the door for more specific Article 5 contingency plans for the defense of eastern European NATO countries.

In reality, the military responses to the Ukraine crisis include many efforts that have been underway within NATO since 2008. The Baltic States and Poland have been urging NATO to draw up contingency plans for the defense of Eastern Europe against Russian incursions or military attack. Two obstacles worked against this: declining defense budgets (who’s going to pay for it?) and a reluctance to officially declare Russia to be a military threat to NATO. The latter obstacle is now gone and U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel’s is now publicly using the Ukraine crisis to ask NATO countries to increase their defense budgets.