Forget LRSO; JASSM-ER Can Do The Job

Early next year the Obama administration, with eager backing from hardliners in Congress, is expected to commit the U.S. taxpayers to a bill of $20 billion to $30 billion for a new nuclear weapon the United States doesn’t need: the Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) air-launched cruise missile.

The new nuclear cruise missile will not be able to threaten targets that cannot be threatened with other existing nuclear weapons. And the Air Force is fielding thousands of new conventional cruise missiles that provide all the standoff capability needed to keep bombers out of harms way, shoot holes in enemy air-defenses, and destroy fixed and mobile soft, medium and hard targets with high accuracy – the same missions defense officials say the LRSO is needed for.

But cool-headed thinking about defense needs and priorities has flown out the window. Instead the Obama administration appears to have been seduced (or sedated) by an army of lobbyists from the defense industry, nuclear laboratories, the Air Force, U.S. Strategic Command, defense hawks in Congressional committees, and academic Cold Warriors, who all have financial, institutional, career, or political interests in getting approval of the new nuclear cruise missile.

LRSO proponents argue for the new nuclear cruise missile as if we were back in the late-1970s when there were no long-range, highly accurate conventional cruise missiles. But that situation has changed so dramatically over the past three decades that advanced conventional weapons have now eroded the need for a nuclear cruise missile.

That reality presents President Obama with a unique opportunity: because the new nuclear cruise missile is redundant for deterrence and unnecessary for warfighting requirements, it is the first opportunity for the administration to do what the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review, 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review, and 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy all called for: use advanced conventional weapons to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons in U.S. national security strategy.

Muddled Mission Claims

Defense officials have made a wide range of claims for why a new nuclear cruise missile is needed, ranging from tactical use against air-defense systems, rapid re-alerting, generic deterrence, escalation-control, to we-need-a-new-one-because-we-have-an-old-one. In a letter to the Senate Appropriations Committee in 2014, Nuclear Weapons Council chairman Frank Kendall provided one of the most authoritative – and interesting – justifications. After reminding the lawmakers that DOD “has an established military requirement for a nuclear capable stand-off cruise missile for the bomber leg of the U.S. Triad,” Kendall further explained:

Nuclear capable bombers with effective stand-off weapons assure our allies and provide a unique and important dimension of U.S. nuclear deterrence in the face of increasingly sophisticated adversary air defenses. The bomber’s stand-off capability with a modern cruise missile will provide a credible capability to penetrate advanced air defenses with multiple weapons attacking from multiple azimuths. Beyond deterrence, an LRSO-armed bomber force provides the President with uniquely flexible options in an extreme crisis, particularly the ability to signal intent and control escalation, long-standing core elements of U.S. nuclear strategy.

Nuclear Weapons Chair Frank Kendall says the LRSO is needed for deterrence and warfighting missions

The “Beyond deterrence” wording is interesting because it suggests that what precedes it is about deterrence and what follows it is not. It essentially says that flying around with bombers with nuclear cruise missiles that can shoot through air-defense systems will deter adversaries (and assure Allies), but if it doesn’t then firing all those nuclear cruise missiles will give the President lots of options to blow things up. And that should calm things down.

But this is where the LRSO mission gets muddled. Because although nuclear cruise missiles could potentially penetrate those air-defenses, so can conventional cruise missiles to hold at risk the same targets. And because it would be much harder for the President to authorize use of nuclear cruise missiles, he would in reality have considerably fewer options with the LRSO than with conventional cruise missiles.

The “options” that Kendall referred to are essentially just different ways to blow up facilities that U.S. planners have decided are important to the adversary. Yet LRSO provides no “unique” capability to blow up a target that cannot be done by existing or planned conventional long-range cruise missiles or, to the limited extent a nuclear warhead is needed to do the job, by other nuclear weapons such as ICBMs, SLBMs, or gravity bombs.

So what’s missing from the LRSO mission justification is why it would matter to an adversary that the United States would not blow up his facilities with nuclear cruise missiles but instead with conventional cruise missiles or other nuclear weapons. And why would it matter so much that the adversary would conclude: “Aha, the United States does not have a nuclear cruise missile, only thousands of very accurate conventional cruise missiles, hundreds of long-range ballistic missiles with thousands of nuclear warheads, and five dozen stealthy bombers with B61-12 guided nuclear bombs that can and will damage my forces or destroy my country. Now is my chance to attack!”

Some defense leaders confuse the need for the nuclear LRSO with broader defense requirements, as illustrated by this statement reportedly made by STRATCOM commander Adm. Haney at the Army & Navy Club in 2014.

A favorite phrase for defense officials these days is that nuclear weapons, including a new air-launched cruise missile, are needed to “convince adversaries they cannot escalate their way out of a failed conflict, and that restraint is a better option.” The scenario behind this statement is that an aggressor, for example Russia attacking a NATO country with conventional forces, is pushed back by superior U.S. conventional forces and therefore considers escalating to limited use of nuclear weapons to defeat U.S. forces or compel the United States to cease its counterattack on Russian forces.

Unless the United States has flexible regional nuclear forces such as the LRSO that can be used in a limited fashion similar to the aggressor’s escalation, so the thinking goes, the United States might be self-deterred from using more powerful strategic weapons in response, incapable of responding “in kind,” and thus fail to de-escalate the conflict on terms favorable to the United States and its Allies. Therefore, some analysts have begun to argue (here and here), the United States needs to develop nuclear weapons that have lower yields and appear more useable for limited scenarios.

The argument has an appealing logic – the same dangerous logic that fueled the Cold War for four decades. It carries with it the potential of worsening the very situation it purports to counter by increasing reliance on nuclear weapons and further stimulating development of regional nuclear warfighting scenarios. While promising to reduce the risk of nuclear use, the result would likely be the opposite.

It also ignores that existing U.S. nuclear forces already have considerable regional flexibility, yield variations, and are getting even better. And it glosses over the fact that U.S. military planners over the past three decades, while fully aware of modernizations in nuclear adversaries and a significant disparity with Russian non-strategic nuclear forces, nonetheless have continued to unilaterally eliminate all land- and sea-based non-strategic nuclear forces that used to serve many of the missions the advocates now say require more regionally tailored nuclear weapons.

Some senior defense officials have also started linking the LRSO justification to recent Russian behavior. Brian McKeon, the Pentagon’s principal deputy defense under secretary for policy, told Congress earlier this month that the Pentagon is “investing in technologies that will be most relevant to Russia’s provocations,” including “the long-range bomber, the new long-range standoff cruise missile…”

Last Time The Air Force Wanted A New Nuclear Cruise Missile…

Such advocacy for the LRSO is like playing a recording from the 1970s when defense officials were urging Congress to pay for nuclear cruise missiles. Back then the justifications were the same: provide bombers with standoff capability, shoot holes in air-defense systems, and provide the President with flexible regional options to hold targets at risk that are important to the adversary. And just as today, many of the justification were not essential or exaggerated.

With a range of more than 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles), the Air-Launched Cruise Missile (ALCM; AGM-86B) was seen as the answer to protecting bombers by holding targets at risk from well beyond the reach of Soviet advanced air-defense systems. After the first test flights in 1979, the ALCM became operational in December 1982 and more than 1,700 ALCMs were produced between 1980 and 1986. But a need for a long-range cruise missile that could actually be used in the real world soon resulted in conversion of hundreds of the ALCMs to conventional CALCMs (AGM-86C) that have since been used in half a dozen wars.

Billions were spent on the nuclear Advanced Cruise Missile for capabilities that had little operational significance. The weapon was retired in 2008.

No sooner had the ALCM entered service before the Air Force started saying the more capable Advanced Cruise Missile (ACM; AGM-129A) was needed: Soviet advanced air-defense systems expected in the 1990s would be able to destroy the ALCMs and the bombers carrying them. Sounds familiar? The initial plan was to produce 2,000 ACMs but the program was cut back to 460 missiles that were produced between 1990 and 1993.

The Air Force described the ACM as a “subsonic, low-observable air-to-surface strategic nuclear missile with significant range, accuracy, and survivability improvements over the ALCM.” And the missile had specifically been “designed to evade air and ground-based defenses in order to strike heavily defended, hardened targets at any location within an enemy’s territory.” A fact sheet on the Air Force’s web site still describes the unique capabilities:

When the threat is deep and heavily defended, the AGM-129A delivers the proven effectiveness of a cruise missile enhanced by stealth technology. Launched in quantities against enemy targets, the ACM’s difficulty to detect, flight characteristics and range result in high probability that enemy targets will be eliminated.

The AGM-129A’s external shape is optimized for low observables characteristics and includes forward swept wings and control surfaces, a flush air intake and a flat exhaust. These, combined with radar-absorbing material and several other features, result in a missile that is virtually impossible to detect on radar.

The AGM-129A offers improved flexibility in target selection over other cruise missiles. Missiles are guided using a combination of inertial navigation and terrain contour matching enhanced with highly accurate speed updates provided by a laser Doppler velocimeter. These, combined with small size, low-altitude flight capability and a highly efficient fuel control system, give the United States a lethal deterrent capability well into the 21st century.

Yet only 17 months after the ACM first become operational in January 1991, a classified GAO review concluded that “the range requirement for [the] ACM offers only a small improvement over the older ALCM and that the accuracy improvement offered does not appear to have real operational significance.”

Even so, ACM production continued for another year and the Air Force kept the missile in the arsenal for another decade-and-a-half. Finally, in 2008, after more than $6 billion spent on developing, producing, and deploying the missile, the ACM was unilaterally retired by the Bush administration. Although not until after a dramatic breakdown of Air Force nuclear command and control in August 2007 resulted in six ACMs with warheads installed being flown on a B-52 across the United States without the Air Force knowing about it.

It is somewhat ironic that after the ACM was retired, the Air Force official who was given the ceremonial honor to crush the last of the unneeded missiles was none other than Brig. Gen. Garrett Harencak, then commander of the Nuclear Weapons Center at Kirtland AFB. The following year Harencak was promoted to Maj. Gen. and Assistant Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration (A-10) at the Pentagon where he became a staunch and sometimes bombastic advocate for the LRSO. Harencak has since been “promoted” to commander of the Air Force Recruiting Service in Texas.

The last Advanced Cruise Missile is destroyed by Brig. Gen. Jarrett Harencak in 2012, then commander of the Nuclear Weapons Center at Kirtland AFB, before he became a primary Air Force advocate for the LRSO.

JASSM-ER: Deterrence Without “N”

The ALCM and ACM were acquired in a different age. LRSO advocates appear to argue for the weapon as if they were still back in the 1970s when the military didn’t have long-range conventional cruise missiles.

Today it does and those conventional weapons are getting so effective, so numerous, and so widely deployed that they can hold at risk the same targets and fulfill the same targeting missions that advocates say the LRSO is needed for. Moreover, the conventional missiles can do the mission without radioactive fallout or the political consequences from nuclear use that would limit any President’s options.

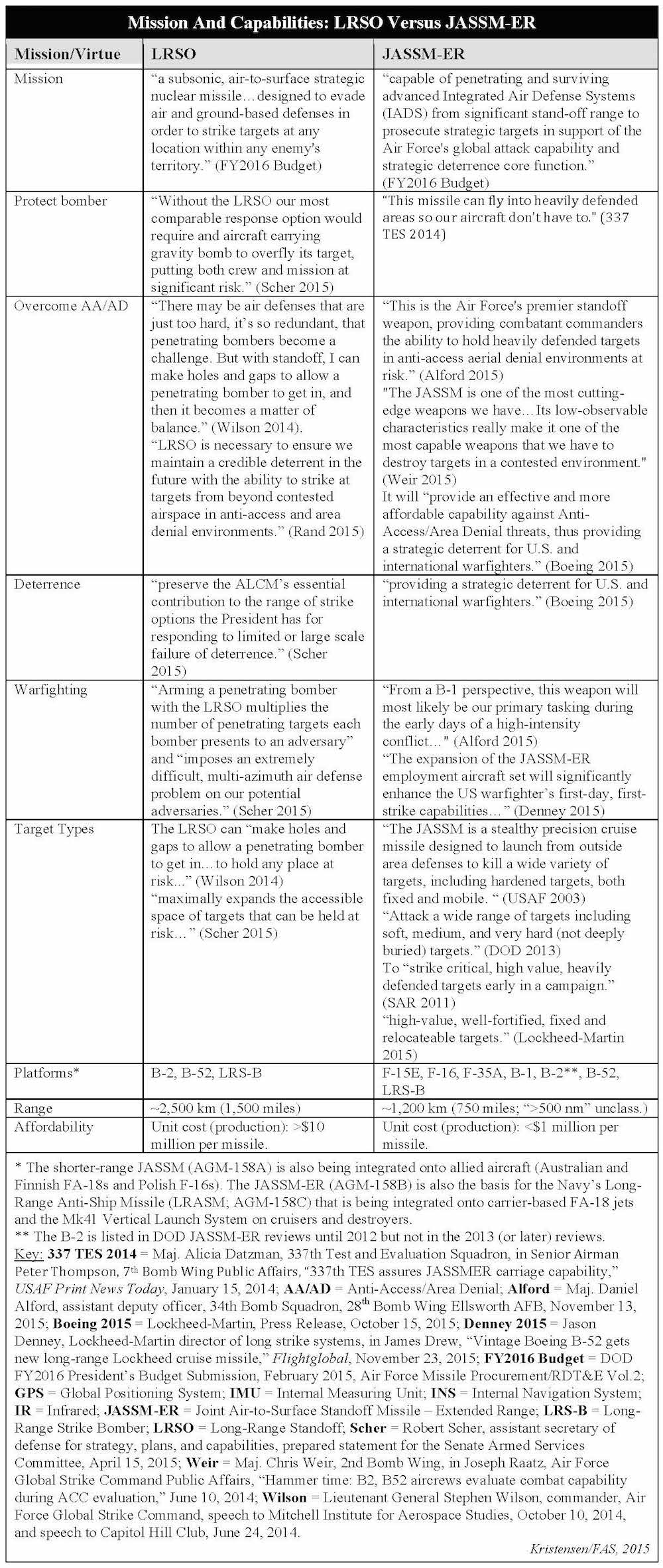

Curiously, defense officials use very similar descriptions when they describe the missions and virtues of the nuclear LRSO and the new conventional long-range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM-ER; AGM-158B). In many cases one could swap the names and you wouldn’t know the difference. The LRSO seems to offer no unique or essential capabilities that the JASSM-ER cannot provide:

2015 LRSO Mission Capabilities

The Pentagon describes the JASSM as a next-generation cruise missile “enabling the United States Air Force (USAF) to destroy the enemy’s war-sustaining capabilities from outside its area air defenses. It is precise, lethal, survivable, flexible, and adverse-weather capable.” Armed with a 1000-pound class, hardened, penetrating warhead with a robust blast fragmentation capability, the JASSM’s “inherent accuracy” (3 meters or less using the Imaging Infrared seeker and less than 13 meters with GPS/INS guidance only) “reduces the number of weapons and sorties required to destroy a target.”

The concept of operations (CONOPS) for JASSM states “employment will occur primarily in the early stages of conflict before air superiority is established, and in the later stages of conflict against high value targets remaining heavily defended. JASSM can also be employed in those cases where, due to rules of engagement/political constraints, high value, point targets must be attacked from international airspace. JASSM may be employed independently or the missile may be used as part of a composite package.”

Full-scale production of the JASSM-ER was authorized in 2014 and the weapon is already deployed on B-1 bombers, each of which can carry 24 missiles – more than the maximum number of ALCMs carried on a B-52H. Over the next decade JASSM-ER will be integrated on nearly all primary strategic and tactical aircraft – including the B-52H. Operational units equipped with the missile will, according to DOD, employ the JASSM-ER against high-value or highly defended targets from outside the lethal range of many threats in order to:

- Destroy targets with minimal risk to flight crews and support air dominance in the theater;

- Strike a variety of targets greater than 500 miles away;

- Execute missions using automated preplanning or manual pre-launch retargeting planning;

- Attack a wide range of targets including soft, medium, and very hard (not deeply buried) targets.

The new long-range JASSM-ER standoff cruise missile is already operational on the B-1 bombers (seen here in 2014 drop-test) and will be added to nearly all bombers and fighter-bombers. A sea-based version will also have land-attack capabilities. A shorter-range version (AGM-158A) is being sold to European and Pacific allies.

Says Kenneth Brandy, the JASSM-ER test director at the 337th Test and Evaluation Squadron: “While other long range weapons may have the capability of reaching targets within the same range, they are not as survivable as the low observable JASSM-ER…The stealth design of the missile allows it to survive through high-threat, well-defended enemy airspace. The B-1’s effectiveness is increased because high-priority targets deeper into heavily defended areas are now vulnerable.”

Indeed, the JASSM-ER is “specifically designed to penetrate air defense systems,” according to the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The JASSM-ER is already now being integrated into STRATCOM’s global strike exercises alongside nuclear weapons. During the Global Lightning exercise in May 2014, for example, B-52s at Barksdale AFB loaded JASSM-ER (see below). And in September 2015, two JASSM-ER equipped B-1 bomb wings were transferred from Air Combat Command (ACC) to Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC) control to operate more closely alongside the nuclear B-2 and B-52H bombers in long-range strike operations.

A JASSM-ER is loaded onto the wing pylon of a B-52H bomber at Barksdale AFB during STRATCOM’s Global Lightning exercise in May 2014.

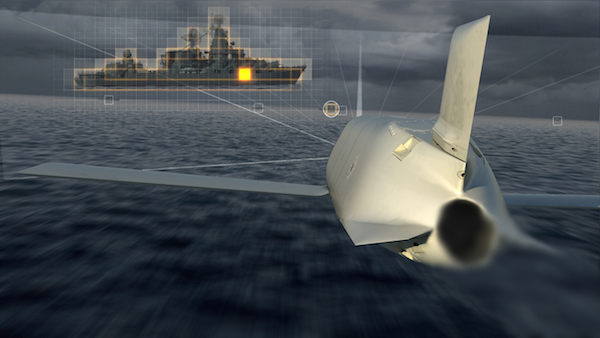

As if the Air Force’s JASSM-ER were not enough, the missile is also being converted into a naval long-range anti-ship cruise missile known as LRASM (Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile; AGM-158C) that in addition to sinking ships will also have land-attack capabilities. The LRASM will be launched from the Mk41 Vertical Launch System on cruisers and destroyers and is also being integrated onto B-1 bombers and carrier-based FA-18 aircraft.

In case anyone doubts who the target is, this Lockheed-Martin illustration shows the LRASM honing in on a Russian Slava-class cruiser.

A Clear Pledge To Reduce Nuclear Role

The considerable standoff targeting capabilities offered by the JASSM-ER and LRASM, as well as the Navy’s existing Tactical Tomahawk land-attack cruise missile, and the enhanced deterrence capability they provide fit well with U.S. policy to use advanced conventional weapons to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons in regional scenarios.

The intent to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons has been clearly stated in key defense planning documents issued by the administration over the past five years: the February 2012 Ballistic Missile Defense Review, the February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review, the April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, and the June 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy.

According to the February 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review Report, “Against nuclear-armed states, regional deterrence will necessarily include a nuclear component (whether forward-deployed or not). But the role of U.S. nuclear weapons in these regional deterrence architectures can be reduced by increasing the role of missile defenses and other capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

The February 2010 Quadrennial Defense Review explained further that “new, tailored, regional deterrence architectures that combine our forward presence, relevant conventional capabilities (including missile defenses), and continued commitment to extend our nuclear deterrent…make possible a reduced role for nuclear weapons in our national security strategy.” (Emphasis added.)

The April 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report added more texture by stating that, while nuclear weapons are still as important, “fundamental changes in the international security environment in recent years – including the growth of unrivaled U.S. conventional military capabilities, major improvements in missile defenses, and the easing of Cold War rivalries – enable us to fulfill those objectives at significantly lower nuclear force levels and with reduced reliance on nuclear weapons. Therefore, without jeopardizing our traditional deterrence and reassurance goals, we are now able to shape our nuclear weapons policies and force structure in ways that will better enable us to meet today’s most pressing security challenges.” (Emphasis added.)

Most recently, in June 2013, the Nuclear Employment Strategy of the United State “narrows U.S. nuclear strategy to focus on only those objectives and missions that are necessary for deterrence in the 21st century,” and in doing so, “takes further steps toward reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our security strategy.” The guidance directs the Department of Defense “to strengthen non-nuclear capabilities and reduce the role of nuclear weapons in deterring non-nuclear attacks,” and specifically “to conduct deliberate planning for non-nuclear strike options to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options, and to propose possible means to make these objectives and effects achievable.” (Emphasis added.)

The Employment Strategy emphasizes that, “Although they are not a substitute for nuclear weapons, planning for non-nuclear strike options is a central part of reducing the role of nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added.)

The pledge to reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons has not risen from a naive unilateral nuclear disarmament gesture but as a consequence of decades of revolutionary advancement of conventional weapons. Those non-nuclear strike capabilities have increased even further since the NPR and the employment guidance were published and will increase even more in the decades ahead as the JASSM-ER and LRASM are integrated onto more and more platforms.

Conclusions and Recommendations

President Obama is facing a crucial decision: whether to approve or cancel the Air Force’s new Long-Range Standoff (LRSO) nuclear air-launched cruise missile. The decision will be his last chance as president to demonstrate that the United States is serious about reducing the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons in its defense strategy.

The President’s decision will also have to take into consideration whether the administration is serious about the pledge it made in the 2010 Nuclear Posture Review Report, that “Life Extension Programs (LEPs)…will not…provide for new military capabilities.” The LRSO will most certainly have new military capabilities compared with the ALCM it is intended to replace.

In their arguments for why the President should approve the LRSO, proponents have so far not presented a single mission that cannot be performed by advanced conventional weapons or other nuclear weapons in the U.S. arsenal.

Indeed, a review of many dozens of official statements, documents, a news media articles revealed that proponents argue for the LRSO as if they were back in the late-1970s arguing for the ALCM at a time when conventional long-range cruise missiles did not exist. As a result, LRSO proponents confuse the need for a standoff capability with the need for a nuclear standoff capability.

Yet in the more than three decades that have passed since the ALCM was approved, a revolution in non-nuclear military technology has produced a wide range of conventional weapons and strategic effects capabilities that can now do many of the targeting missions that nuclear weapons previously served. Indeed, the Navy and Army have already retired all their non-strategic nuclear weapons and today rely on conventional weapons for those missions.

Now it’s the Air Force’s turn; advanced conventional cruise missiles can now serve the role that nuclear air-launched cruise missiles used to serve: hold at risk heavily defended strategic and tactical targets at a range far beyond the reach of modern and anticipated air-defense systems. The Navy already has its Tactical Tomahawk widely deployed on ships and submarines, and now the Air Force is following with deployment of thousands of long-range Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM-ER) on bombers and fighter-bombers. The conventional missiles will in fact provide the President with more (and better) options than he has with a nuclear air-launched cruise missile; it will be a more credible deterrent.

This reality seems to not exist for LRSO advocates who argue from a point of doctrine instead of strategy. And for some the obsession with getting the nuclear cruise missile appears to have become more important than the mission itself. STRATCOM commander Adm. Cecil Haney reportedly argued recently that getting the LRSO “is just as important as having a future bomber.” It is perhaps understandable that a defense contractor can get too greedy but defense officials need to get their priorities straight.

The President needs to cut through the LRSO sales pitch and do what the NPR and employment guidance call for: reduce the role of and reliance on nuclear weapons by canceling the LRSO and instead focus bomber standoff strike capabilities on conventional cruise missiles. Doing so will neither unilaterally disarm the United States, undermine the nuclear Triad, nor abandon the Allies.

Now is your chance Mr. President – otherwise what was all the talk about reducing the role of nuclear weapons for?

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Kalibr: Savior of INF Treaty?

By Hans M. Kristensen

With a series of highly advertised sea- and air-launched cruise missile attacks against targets in Syria, the Russian government has demonstrated that it doesn’t have a military need for the controversial ground-launched cruise missile that the United States has accused Russia of developing and test-launching in violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty.

Moreover, President Vladimir Putin has now publicly confirmed (what everyone suspected) that the sea- and air-launched cruise missiles can deliver both conventional and nuclear warheads and, therefore, can hold the same targets at risk. (Click here to download the Russian Ministry of Defense’s drawing providing the Kalibr capabilities.)

The United States has publicly accused Russia of violating the INF treaty by developing, producing, and test-launching a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) to a distance of 500 kilometers (310 miles) or more. The U.S. government has not publicly identified the missile, which has allowed the Russian government to “play dumb” and pretend it doesn’t know what the U.S. government is talking about.

The lack of specificity has also allowed widespread speculations in the news media and on private web sites (this included) about which missile is the culprit.

As a result, U.S. government officials have now started to be a little more explicit about what the Russian missile is not. Instead, it is described as a new “state-of-the-art” ground-launched cruise missile that has been developed, produced, test-launched – but not yet deployed.

Whether or not one believes the U.S. accusation or the Russian denial, the latest cruise missile attacks in Syria demonstrate that there is no military need for Russia to develop a ground-launched cruise missile. The Kalibr SLCM finally gives Russia a long-range conventional SLCM similar to the Tomahawk SLCM the U.S. navy has been deploying since the 1980s.

What The INF Violation Is Not

Although the U.S. government has yet to publicly identify the GLCM by name, it has gradually responded to speculations about what it might be by providing more and more details about what the GLCM is not. Recently two senior U.S. officials privately explained about the INF violation that:

- it is not the R-500 cruise missile (Iskander-K);

- it is not the RS-26 road-mobile ballistic missile;

- it is not a sea-launched cruise missile test-launched from a ground launcher;

- it is not an air-launched cruise missile test-launched from a ground launcher;

- it is not a technical mistake;

- it is not one or two test slips;

- it is in development but has not yet been deployed.

Rose Gottemoeller, the U.S. under secretary of state for and international security, said in response to a question at the Brookings Institution in December 2014: “It is a ground-launched cruise missile. It is neither of the systems that you raised. It’s not the Iskander. It is not the other one, X-100. Is that what it is? Yeah, I’ve seen some of those reflections in the press and it’s not that one.” [The question was in fact about the X-101, sometimes used as a designation for the air-launched Kh-101, a conventional missile that also exists in a nuclear version known as the Kh-102.]

The explicit ruling out of the Iskander as an INF violation is important because numerous news media and private web sites over the past several years have claimed that the ballistic missile (SS-26; Iskander-M) has a range of 500 km (310 miles), possibly more. Such a range would be a violation of the INF. In contrast, the U.S. National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has consistently listed the range as 300 km (186 miles). Likewise, the cruise missile known as Iskander-K (apparently the R-500) has also been widely rumored to have a range that violates the INF, some saying 2,000 km (1,243 miles) and some even up to 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles). But Gottemoeller’s statement seems to undercut such rumors.

Gottemoeller told Congress in December 2015 that “we had no information or indication as of 2008 that the Russian Federation was violating the treaty. That information emerged in 2011.” And she repeated that “this it is not a technicality, a one off event, or a case of mistaken identity,” such as a SLCM launched from land.

Instead, U.S. officials have begun to be more explicit about the GLCM, saying that it involves “a state-of-the-art ground-launched cruise missile that Russia has tested at ranges capable of threatening most of [the] European continent and out allies in Northeast Asia” (emphasis added). Apparently, the “state-of-the-art” phrase is intended to underscore that the missile is new and not something else mistaken for a GLCM.

Some believe the GLCM may be the 9M729 missile, and unidentified U.S. government sources say the missile is designated SSC-X-8 by the U.S. Intelligence Community.

Forget GLCM: Kalibr SLCM Can Do The Job

Whatever the GLCM is, the Russian cruise missile attacks on Syria over the past two months demonstrate that the Russian military doesn’t need the GLCM. Instead, existing sea- and air-launched cruise missiles can hold at risk the same targets. U.S. intelligence officials say the GLCM has been test-launched to about the same range as the Kalibr SLCM.

Following the launch from the Kilo-II class submarine in the Mediterranean Sea on December 9, Putin publicly confirmed that the Kalibr SLCM (as well as the Kh-101 ALCM) is nuclear-capable. “Both the Calibre [sic] missiles and the Kh-101 [sic] rockets can be equipped either with conventional or special nuclear warheads.” (The Kh-101 is the conventional version of the new air-launched cruise missile, which is called Kh-102 when equipped with a nuclear warhead.)

The conventional Kalibr version used in Syria appears to have a range of up to 2,000 kilometers (1,240 miles). It is possible, but unknown, that the nuclear version has a longer range, possibly more than 2,500 kilometers (1,550 miles). The existing nuclear land-attack sea-launched cruise missile (SS-N-21) has a range of more than 2,800 kilometers (the same as the old AS-15 air-launched cruise missile).

The Russian navy is planning to deploy the Kalibr widely on ships and submarines in all its five fleets: the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula; the Baltic Sea Fleet in Kaliningrad and Saint Petersburg; the Black Sea Fleet bases in Sevastopol and Novorossiysk; the Caspian Sea Fleet in Makhachkala; and the Pacific Fleet bases in Vladivostok and Petropavlovsk.

The Russian navy is already bragging about the Kalibr. After the Kalibr strike from the Caspian Sea, Vice Admiral Viktor Bursuk, the Russian navy’s deputy Commander-in-Chief, warned NATO: “The range of these missiles allows us to say that ships operating from the Black Sea will be able to engage targets located quite a long distance away, a circumstance which has come as an unpleasant surprise to counties that are members of the NATO block.”

With a range of 2,000 kilometers the Russian navy could target facilities in all European NATO countries without even leaving port (except Spain and Portugal), most of the Middle East, as well as Japan, South Korea, and northeast China including Beijing (see map below).

As a result of the capabilities provided by the Kalibr and other new conventional cruise missiles, we will probably see many of Russia’s old Soviet-era nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles retiring over the next decade.

The nuclear Kalibr land-attack version will probably be used to equip select attack submarines such as the Severodvinsk (Yasen) class, similar to the existing nuclear land-attack cruise missile (SS-N-21), which is carried by the Akula, Sierra, and Victor-III attack submarines, but not other submarines or surface ships.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Now that Russia has demonstrated the capability of its new sea- and air-launched conventional long-range cruise missiles – and announced that they can also carry nuclear warheads – it has demonstrated that there is no military need for a long-range ground-launched cruise missile as well.

This provides Russia with an opportunity to remove confusion about its compliance with the INF treaty by scrapping the illegal and unnecessary ground-launched cruise missile project.

Doing so would save money at home and begin the slow and long process of repairing international relations.

Moreover, Russia’s widespread and growing deployment of new conventional long-range land-attack and anti-ship cruise missiles raises questions about the need for the Russian navy to continue to deploy nuclear cruise missiles. Russia’s existing five nuclear sea-launched cruise missiles (SS-N-9, SS-N-12, SS-N-19, SS-N-21 and SS-N-22) were all developed at a time when long-range conventional missiles were non-existent or inadequate.

Those days are gone, as demonstrated by the recent cruise missile attacks, and Russia should now follow the U.S. example from 2011 when it scrapped its nuclear Tomahawk sea-launched cruise missile. Doing so would reduce excess types and numbers of nuclear weapons.

Background:

- Russian Nuclear Forces, 2015, FAS Nuclear Notebook, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

- Status of World Nuclear Forces, 2015

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

US Drops Below New START Warhead Limit For The First Time

By Hans M. Kristensen

The number of U.S. strategic warheads counted as “deployed” under the New START Treaty has dropped below the treaty’s limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time since the treaty entered into force in February 2011 – a reduction of 263 warheads over four and a half years.

Russia, by contrast, has increased its deployed warheads and now has more strategic warheads counted as deployed under the treaty than in 2011 – up 111 warheads.

Similarly, while the United States has reduced its number of deployed strategic launchers (missiles and bombers) counted by the treaty by 120, Russia has increased its number of deployed launchers by five in the same period. Yet the United States still has more launchers deployed than allowed by the treaty (by 2018) while Russia has been well below the limit since before the treaty entered into force in 2011.

These two apparently contradictory developments do not mean that the United States is falling behind and Russia is building up. Both countries are expected to adjust their forces to comply with the treaty limits by 2018.

Rather, the differences are due to different histories and structures of the two countries’ strategic nuclear force postures as well as to fluctuations in the number of weapons that are deployed at any given time.

Deployed Warhead Status

The latest warhead count published by the U.S. State Department lists the United States with 1,538 “deployed” strategic warheads – down 60 warheads from March 2015 and 263 warheads from February 2011 when the treaty entered into force.

But because the treaty artificially counts each bomber as one warhead, even though the bombers don’t carry warheads under normal circumstances, the actual number of strategic warheads deployed on U.S. ballistic missiles is around 1,450. The number fluctuates from week to week primarily as ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) move in and out of overhaul.

Russia is listed with 1,648 deployed warheads, up from 1,537 in 2011. Yet because Russian bombers also do not carry nuclear weapons under normal circumstances but are artificially counted as one warhead per bomber, the actual number of Russian strategic warheads deployed on its ballistic missiles is closer to 1,590 warheads.

Because it has fewer ICBMs than the United States (see below), Russia is prioritizing deployment of multiple warheads on its new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). In contrast, the United States has downloaded its ICBMs to carry a single warhead – although the missiles retain the capability to load the warheads back on if necessary. And the next-generation missile (GBSD; Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent) the Air Force plans to deploy a decade from now will also be capable of carry multiple warheads.

Warheads from the last MIRVed U.S. ICBM are moved to storage at Malmstrom AFB in June 2014. The sign “MIRV Off Load” has been altered from “Wide Load” on the original photo. Image: US Air Force.

This illustrates one of the deficiencies of the New START Treaty: it does not limit how many warheads Russia and the United States can keep in storage to load back on the missiles. Nor does it limit how many of the missiles may carry multiple warheads.

And just a reminder: the warheads counted by the New START Treaty are not the total arsenals or stockpiles of the United States and Russia. The total U.S. stockpile contains approximately 4,700 warheads (with another 2,500 retired but still intact warheads awaiting dismantlement. Russia has a stockpile of approximately 4,500 warheads (with perhaps 3,000 more retired warheads awaiting dismantlement).

Deployed Launcher Status

The New START Treaty count lists a total of 762 U.S. deployed strategic launchers (ballistic missiles and long-range bombers), down 23 from March 2015 and a total reduction of 120 launchers since 2011. Another 62 launchers will need to be removed before February 2018.

Four and a half years after the treaty entered into force, the U.S. military is finally starting to reduce operational nuclear launchers. Up till now all the work has been focused on eliminating so-called phantom launchers, that is launchers that were are no longer used in the nuclear mission but still carry some equipment that makes them accountable. But that is about to change.

On September 17, the Air Force announced that it had completed denuclearization of the first of 30 operational B-52H bombers to be stripped of their nuclear equipment. Another 12 non-deployed bombers will also be denuclearized for a total of 42 bombers by early 2017. That will leave approximately 60 B-52H and B-2A bombers accountable under the treaty.

The Air Force is also working on removing Minuteman III ICBMs from 50 silos to reduce the number of deployed ICBMs from 450 to no more than 400. Unfortunately, arms control opponents in the U.S. Congress have forced the Air Force to keep the 50 empted silos “warm” so that missiles can be reloaded if necessary.

Finally, this year the Navy is scheduled to begin inactivating four of the 24 missile tubes on each of its 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. The work will be completed in 2017 to reduce the number of deployed sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) to no more than 240, down from 288 missiles today.

Russia is counted with 526 deployed launchers – 236 less than the United States. That’s an addition of 11 launchers since March 2015 and five launchers more than when New START first entered into force in 2011. Russia is already 174 deployed launchers below the treaty’s limit and has been below the limit since before the treaty was signed. So Russia is not required to reduce any more deployed launchers before 2018 – in fact, it could legally increase its arsenal.

Yet Russia is retiring four Soviet-era missiles (SS-18, SS-19, SS-25, and SS-N-18) faster than it is deploying new missiles (SS-27 and SS-N-32) and is likely to reduce its deployed launchers more over the next three years.

Russia is also introducing the new Borei-class SSBN with the SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBM, but slower than previously anticipated and is unlikely to have eight boats in service by 2018. Two are in service with the Northern Fleet (although one does not appear fully operational yet) and one arrived in the Pacific Fleet last month. The Borei SSBNs will replace the old Delta III SSBNs in the Pacific and later also the Delta IV SSBNs in the Northern Fleet.

Russian Borei- and Delta IV-class SSBNs at the Yagelnaya submarine base on the Kola Peninsula. Click to open full size image.

The latest New START data does not provide a breakdown of the different types of deployed launchers. The United States will provide a breakdown in a few weeks but Russia does not provide any information about its deployed launchers counted under New START (nor does the U.S. Intelligence Community say anything in public about what it sees).

As a result, we can’t see from the latest data how many bombers are counted as deployed. The U.S. number is probably around 88 and the Russian number is probably around 60, although the Russian bomber force has serious operational and technical issues. Both countries are developing new strategic bombers.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Four and a half years after the New START Treaty entered into force in 2011, the United States has reduced its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads below the limit of 1,550 warheads for the first time. The treaty limit enters into effect in February 2018.

Russia has moved in the other direction and increased its “accountable” deployed strategic warheads and launchers since the treaty entered into force in 2011. Not by much, however, and Russia is expected to reduce its deployed strategic warheads as required by the New START Treaty by 2018. Russia is not in a build-up but in a transition from Soviet-era weapons to newer types that causes temporary fluctuations in the warhead count. And Russia is far below the treaty’s limit on deployed strategic launchers.

Yet it is disappointing that Russia has allowed its number of “accountable” deployed strategic warheads to increase during the duration of the treaty. There is no need for this increase and it risks fueling exaggerated news media headlines about a Russian nuclear “build-up.”

Overall, however, the New START reductions are very limited and are taking a long time to implement. Despite souring East-West relations, both countries need to begin to discuss what will replace the treaty after it enters into effect in 2018; it will expire in 2021 unless the two countries agree to extend it for another five years. It is important that the verification regime is not interrupted and failure to agree on significantly lower limits before the next Non-Proliferation Treaty review conference in 2020 will hurt U.S. and Russian status.

Moreover, defining lower limits early rather than later is important now to avoid that nuclear force modernization programs already in full swing in both countries are set higher (and more costly) than what is actually needed for national security.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The Red Web: Russia and the Internet

The Internet in Russia is a battleground between activists who would use it as a tool of political and cultural freedom and government officials who see it as a powerful instrument of political control, write investigative journalists Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan in their new book The Red Web. For now, the government appears to be winning the battle.

Soldatov and Borogan trace the underlying conflict back to official anxiety in the Soviet era about the hazards of freedom of information. In the 1950s, the first Soviet photocopy machine was physically destroyed at the direction of the government “because it threatened to spread information beyond the control of those who ruled.”

With the introduction of imported personal computers in the 1980s and a connection to the Internet in 1990, new possibilities for free expression and political organizing in Russia seemed to arise. But as described in The Red Web, each private initiative was met by a government response seeking to disable or limit it. Internet service providers were required to install “black boxes” (known by the acronym SORM) giving Russia’s security services access to Internet traffic. Independent websites, such as the authors’ own agentura.ru site on intelligence matters, were subject to blocking and attack. Journalists’ computers were seized.

But the struggle continued. Protesters used new social media tools to organize demonstrations. The government countered with new facial recognition technology and cell phone tracking to identify them. Large teams of “trolls” were hired to disrupt social networks. A nationwide system of online filtering and censorship was put in place by 2012, and has been refined since then.

To some extent, the government actions constituted an implied threat rather than a fully implemented one, according to Soldatov and Borogan.

“The Russian secret services have had a long tradition of using spying techniques not merely to spy on people but to intimidate them. The KGB had a method of ‘overt surveillance’ in which they followed a target without concealing themselves. It was used against dissidents.”

And in practice, much of the new surveillance infrastructure fell short of stifling independent activity, as the authors’ own work testifies.

“The Internet filtering in Russia turned out to be unsophisticated; thousands of sites were blocked by mistake, and users could easily find ways to make an end-run around it,” they write. Moreover, “very few people in Russia were actually sent to jail for posting criticism of the government online.”

Nevertheless, “Russian Internet freedom has been deeply curtailed.”

In a chapter devoted to the case of Edward Snowden, the authors express disappointment in Snowden’s unwillingness to comment on Russian surveillance or to engage with Russian journalists. “To us, the silence seemed odd and unpleasant.”

More important, they say that Snowden actually made matters in Russia worse.

“Snowden may not have known or realized it, but his disclosures emboldened those in Russia who wanted more control over the Internet,” they write.

Because the Snowden disclosures were framed not as a categorical challenge to surveillance, but exclusively as an exposure of U.S. and allied practices, they were exploited by the Russian government to legitimize its own preference for “digital sovereignty.”

Snowden provided “cover for something the Kremlin wanted all along– to force Facebook, Twitter, and Google’s services, Gmail and YouTube, to be subject to Russian legislation, which meant providing backdoor access to the Russian security services.”

“Snowden could have done good things globally, but for Russia he was a disaster,” said Stas Kozlovsky of Moscow State University, a leading Wikipedia contributor in Russia, as quoted in The Red Web.

(Recently, Snowden has spoken out more clearly against Russian surveillance practices. “I’ve been quite critical of [it] in the past and I’ll continue to be in the future, because this drive that we see in the Russian government to control more and more the internet, to control more and more what people are seeing, even parts of personal lives, deciding what is the appropriate or inappropriate way for people to express their love for one another … [is] fundamentally wrong,” he said in a recent presentation. See “Snowden criticises Russia for approach to internet and homosexuality,” The Guardian, September 5, 2015).

The Red Web provides a salutary reminder for Western readers that the so-called U.S. “surveillance state” has hardly begun to exercise the possibilities of political control implied in that contemptuous term. For all of its massive collection of private data, the National Security Agency — unlike its Russian counterparts — has not yet interfered in domestic elections, censored private websites, disrupted public gatherings, or gained unrestricted access to domestic communications.

Soldatov and Borogan conclude on an optimistic note. After all, they write, things are even worse in China. See The Red Web: The Struggle Between Russia’s Digital Dictators and the New Online Revolutionaries by Andrei Soldatov and Irina Borogan, Public Affairs, 2015.

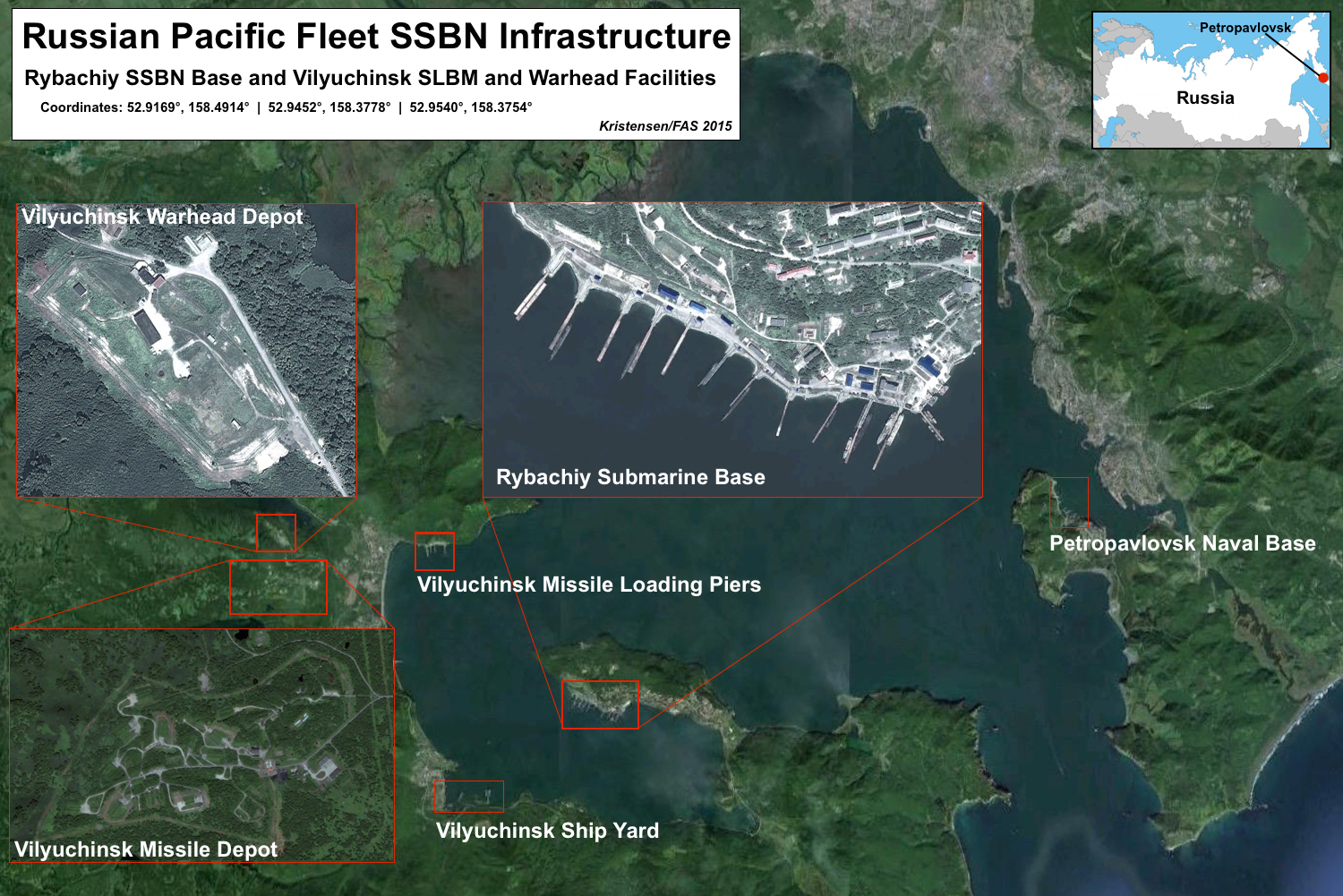

Russian Pacific Fleet Prepares For Arrival of New Missile Submarines

Later this fall (possibly this month) the first new Borei-class (sometimes spelled Borey) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) is scheduled to arrive at the Rybachiy submarine base near Petropavlovsk on the Kamchatka Peninsula.

[Update September 30, 2015: Captain First Rank Igor Dygalo, a spokesperson for the Russian Navy, announced that the Aleksander Nevsky (K-550) arrived at Rybachiy Submarine Base at 5 PM local time (5 AM GMT) on September 30, 2015.]

At least one more, possibly several, Borei SSBNs are expected to follow over the next few years to replace the remaining outdated Delta-III SSBNs currently operating in the Pacific.

The arrival of the Borei SSBNs marks the first significant upgrade of the Russian Pacific Fleet SSBN force in more than three decades.

In preparation for the arrival of the new submarines, satellite pictures show upgrades underway to submarine base piers, missile loading piers, and nuclear warhead storage facilities.

Several nuclear-related facilities near Petropavlovsk are being upgraded.

Upgrade of Rybachiy Submarine Base Pier

Similar to upgrades underway at the Yagelnaya Submarine Base to accommodate Borei-class SSBNs in the Northern Fleet on the Kola Peninsula, upgrades visible of submarine piers at Rybachiy Submarine Base are probably in preparation for the arrival of the first Borei SSBN – the Aleksandr Nevskiy (K-550) in the near future (see below).

Upgrades at Rybachiy submarine base.

Commercial satellite images from 2014 show a new large pier under construction. The pier includes six large pipes, probably for steam and water to maintain the submarines and their nuclear reactors while in port.

The image also shows two existing Delta III SSBNs, one with two missile tubes open and receiving service from a large crane. Other visible submarines include a nuclear-powered Oscar-II class guided missile submarine, a nuclear-powered Victor III attack submarine, and a diesel-powered Kilo-class submarine.

The arrival of the Borei-class in the Pacific has been delayed for more than a year because of developmental delays of the Bulava missile (SS-N-32) and the SSBN construction program. Russian Deputy Defence Minister Ruslan Tsalikov recently visited the base and promised that infrastructure and engineering work for the Borei-class SSBNs would be completed in time for the arrival of the Aleksander Nevsky (K-550). Predictions for arrival range from early- to late-September 2015.

Upgrade of Missile Depot Loading Pier

When not deployed onboard SSBNs, sea-launched ballistic missiles and their warheads are stored at the Vilyuchinsk missile deport and warhead storage site across the bay approximately 8 kilometers (5 miles) east-northwest of the Rybachiy submarine base. To receive and offload missiles and warheads, an SSBN will moor at one of two piers where a large floating crane is used to lift missiles into or out of the submarine’s 16 launch tubes.

Upgrades of Vilyuchinsk missile loading piers.

Satellite images show that a larger third pier is under construction possibly to accommodate the Borei SSBNs and the Bulava SLBM loadings (see above). This will also provide additional docking space for both submarines and surface ships that use the facility.

SS-N-18 handling at Vilyuchinsk missile loading pier.

The missile depot itself includes approximately 60 earth-covered bunkers (igloos) and a number of service facilities located inside a 2-kilometer (1.3- mile) long, multi-fenced facility covering an area of 2.7 square kilometer (half a square mile). The igloos have large front doors that allow SLBMs to be rolled in for horizontal storage inside the climate-controlled facilities (see image below).

Vilyuchinsk missile depot.

In addition to SLBMs for SSBNs, the depot probably also stores cruise missiles for attack submarines and surface ships. A supply ship will normally load the missiles at Vilyuchinsk and then deliver them to the attack submarine or surface ship back at their base piers. However, most of the Russian surface fleet in the Pacific is based at Vladivostok, some 2,200 kilometers (1,400 miles) to the southwest near North Korea, and has its own nuclear weapons storage sites.

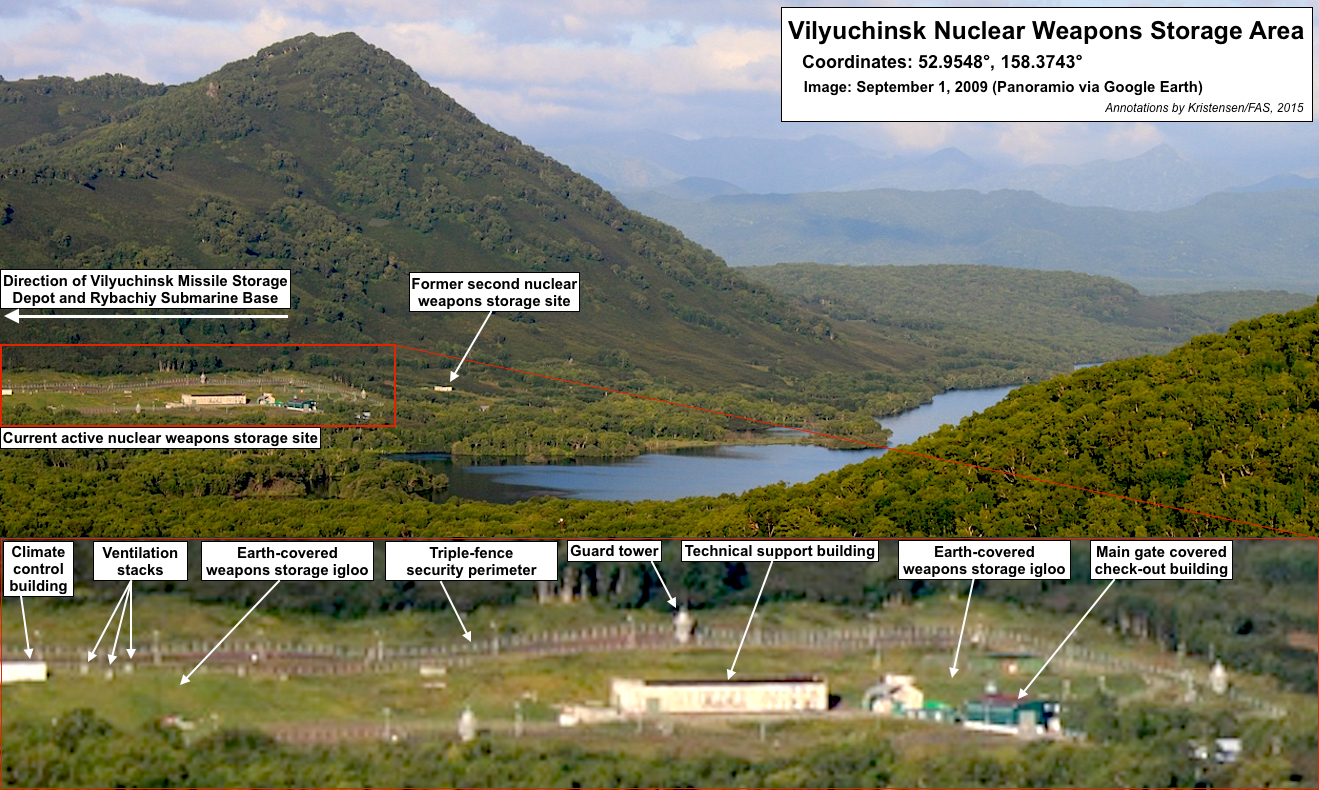

Upgrade of Warhead Storage Site

When not mated with SLBMs onboard the SSBNs, nuclear warheads appear to be stored at a weapons storage facility north of the missile depot. The facility, which includes two earth-covered concrete storage bunkers, or igloos, inside a 430-meter (1,500-foot) long 170-meter (570-foot) wide triple-fenced area, is located on the northeastern slope of a small mountain next to a lake north of the missile depot. A third igloo outside the current perimeter probably used to store nuclear warheads in the past when more SSBNs were based at Rybachiy (see image below).

Vilyuchinsk nuclear weapons storage area.

Satellite images show that the nuclear weapons storage site is under major renovation. The work started sometime after August 2013. By September 2014, one of the two igloos inside the security perimeter had been completely exposed revealing an 80×25-meter (263×82-foot) underground structure. The structure has two access tunnels and climate control (see below).

Upgrade of Vilyuchinsk nuclear weapons storage area.

A later satellite image taken on November 1, 2014 reveals additional details of the storage facility. Rather than one large storage room, it appears to be made up of several rooms. One of the internal structures is about 37 meters (82 feet) long. A 30-meter (90 feet) long and 10-meter (30 feet) wide tunnel that connects the storage section with the main square of the site is being lengthened with new entry building. It is not possible to determine from the satellite images how deep the structure is but it appears to be at least 25 meters (see image below).

Upgrade of Vilyuchinsk nuclear weapons igloo.

The weapons storage facility is likely capable of storing several hundred nuclear warheads. Each Delta-III SSBN based at Rybachiy can carry 16 SLBMs with up to 48 warheads. In recent years the Pacific Fleet has included only 2-3 Delta IIIs with a total of 96-144 warheads, but there used be many more SSBNs operating from Rybachiy. Each new Borei-class SSBN is capable of carrying twice the number of warheads of a Delta III and so far 2-3 Borei SSBNs are expected to transfer to the Pacific over the next few years.

To arm the SLBMs loaded onto submarines at the missile-loading pier, the warheads are first loaded onto trucks at the warheads storage facility and then driven the 2.5 kilometers (1.6 miles) down the road to the entrance of the missile depot. During storage site renovation the warheads that are not onboard the SSBNs are probably stored in the second igloo inside the security perimeter or temporarily at the missile depot.

Implications and Recommendations

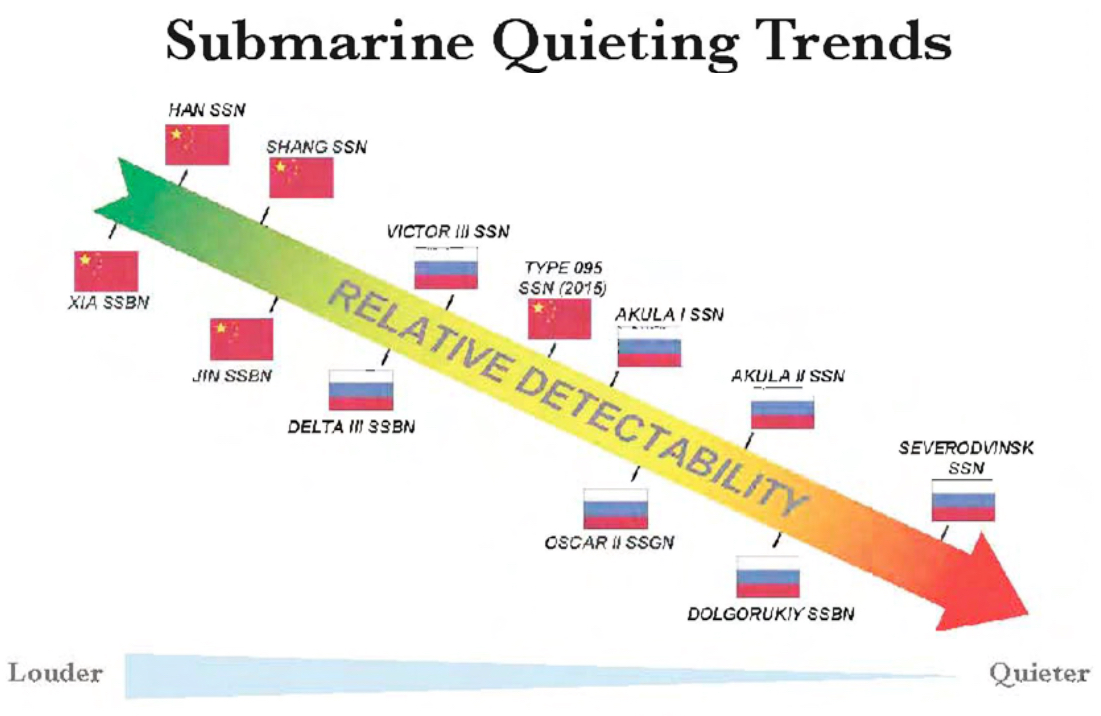

The expected arrival of the Borei SSBNs at the Rybachiy submarine base marks the first significant upgrade of the Russian Pacific Fleet SSBN force in more than three decades. The new submarines will have implications for strategic nuclear operations in the Pacific: they will be quieter and capable of carrying more nuclear warheads than the current class of Delta III submarines.

The Borei-class SSBN is significantly quieter than the Delta III and quieter than the Akula II-class attack submarine. A Delta III would probably have a hard time evading modern U.S. and Japanese anti-submarine forces but the Borei-class SSBN would be harder to detect. Even so, according to a chart published by the US Navy’s Office of Naval Intelligence, the Borei-class SSBN is not as quiet as the Severodvinsk-class (Yasen) attack submarine (see graph below).

Nuclear submarine noise levels. Credit: US Navy Office of Naval Intelligence.

The Borei-class SSBN is equipped with as many SLBMs (16) as the Delta III-class SSBN. But the SS-N-32 (Bulava) SLBM on the Borei can carry twice as many warheads (6) as the SS-N-18 SLBM on the Delta III and is also thought to be more accurate. How many Borei-class SSBNs will eventually operate from Rybachiy remains to be seen. After the arrival of Alexander Nevsky later this year, a second is expected to follow in 2016. A total of eight Borei-class SSBNs are planned for construction under the Russian 2015-2020 defense plan but more could be added later to eventually replace all Delta III and Delta IV SSBNs.

With its SSBN modernization program, Russia is following the examples of the United States and China, both of which have significantly modernized their SSBN forces operating in the Pacific region over the past decade and a half.

The United States added the Trident II D5 SLBM to its Pacific SSBN fleet in 2002-2007, replacing the less capable Trident I C4 first deployed in the region in 1982. The D5 has greater range and better accuracy than its predecessor and also carries the more powerful W88 warhead. Unlike the C4, the D5 has full target kill capability and has significantly increased the effectiveness of the U.S. nuclear posture in the Pacific. Today, about 60 percent of all U.S. SSBN patrols take place in the Pacific, compared with the Cold War when most patrols happened in the Atlantic. The US Navy has announced plans to build 12 new and improved SSBNs and there are already rumors that Russia may build 12 Borei SSBNs as well.

China, for its part, has launched four new Jin-class SSBNs designed to carry the new Julang-2 SLBM. The Julang-2 (JL-2) has longer range and greater accuracy than its predecessor, the JL-1 developed for the unsuccessful Xia-class SSBN.

Combined, the nuclear modernization programs (along with the general military build-up) in the Pacific are increasing the strategic importance of and military competition in the region. The Borei-class SSBNs at Rybachiy will sail on deterrent patrols into the Pacific officially to protect Russia but they will of course also be seen as threatening other countries. Rather than sailing far into the Pacific, the Boreis will most likely be deployed in so-called bastions near the Kamchatka Peninsula where Russian attack submarines will try to protect them against U.S. attack submarines – the most advanced of which are being deployed to the Pacific.

And so, the wheels of the nuclear arms race make another turn…

For more information, see: Russian Nuclear Forces 2015

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Forces 2015

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian nuclear weapons have received a lot of attention lately. Russian officials casually throw around direct or thinly veiled nuclear threats (here, here and here). And U.S. defense hawks rail (here and here) about a Russian nuclear buildup.

In reality, rather than building up, Russia is building down but appears to be working to level off the force within the next decade to prevent further unilateral reduction of its strategic nuclear force in the future. For details, see the latest FAS Nuclear Notebook on the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists web site.

This trend makes it more important for the United States and Russia to reach additional nuclear arms control agreements to reduce strategic nuclear forces. Hard to imagine in the current climate, but remember: even at the height of the Cold War the two sides reached important arms limitation agreements because it was seen then (as it is now) to be in their national security interest.

Trends: Launchers and Warheads

There are many uncertainties about the future development of Russian nuclear forces. Other than three aggregate numbers released under the New START Treaty, neither Russia nor the United States publish data on the numbers of Russian nuclear forces.

Russian officials occasionally make statements about the status of individual nuclear launchers and modernization programs, and Russian news articles provide additional background. Moreover, commercial satellite photos make it possible to monitor (to some extent) the status of strategic nuclear forces.

As a result, there is considerable – and growing – uncertainty about the status and trend of Russian nuclear forces. The available information indicates that Russia is continuing to reduce its strategic nuclear launchers well below the limit set by the New START Treaty. Over the next decade, all Soviet-era ICBMs (SS-18, SS-19, and SS-25) will be retired, the navy’s Delta III SSBN and its SS-N-18 missiles will be retired, and some of the Delta IV SSBNs will probably be retired as well.

To replace the Soviet-era launchers, Russia is deploying and developing several versions of the SS-27 ICBM and developing a new “heavy” ICBM. The navy is deploying the Borey-class SSBN with a new missile, the SS-N-32 (Bulava). This transition has been underway since 1997.

Depending on the extent of modernization plans over the next decade and how many missiles Russia can actually produce and deploy, the overall strategic force appears to be leveling off just below 500 launchers (see below), well below the New START Treaty limits of 700 deployed strategic launchers and 800 deployed and non-deployed strategic launchers.

The warhead loading on the strategic launchers is also decreasing mainly because of the retirement of warhead-heavy SS-18 and SS-19 ICBMs. But because single-warhead SS-25s are being replaced with MIRVed SS-27s, and because the navy’s new SS-N-32 (Bulava) missile carries more warheads than the SS-N-18 and SS-N-23 missiles it is replacing, the overall warhead loading appears to be leveling off as well (see below).

Not all of these warheads are deployed on launchers at any given time. Weapons are not loaded on bombers under normal circumstances and some SSBNs and ICBMs are down for maintenance or repair. The latest New START Treaty warhead count was 1,582 warheads, which means approximately 1,525 warheads were on SSBNs and ICBMs (excluding the roughly 55 counted bombers that are artificially attributed one weapon each).

Non-strategic nuclear weapons are also described in the Notebook. Their status is even more uncertain than the strategic forces. We estimate there are roughly 2,000 warheads assigned to fighter-bombers, short-range ballistic missiles, naval cruise missiles and anti-submarine weapons, and land-based defense and missile-defense forces. Some of the non-strategic nuclear forces are also being modernized and the United States has accused Russia of developing a new ground-launched cruise missile in violation of the INF Treaty, but overall the size of the non-strategic nuclear forces will likely decreased over the next decade.

Russian Nuclear Strategy: What’s Real?

Underpinning these nuclear forces is Russia’s nuclear strategy, which reportedly is causing concern in NATO. A new study was discussed at the NATO ministerial meeting in February. “What worries us most in this strategy is the modernization of the Russian nuclear forces, the increase in the level of training of those forces and the possible combination between conventional actions and the use of nuclear forces, including possibly in the framework of a hybrid war,” one unnamed NATO official told Reuters.

That sounds like a summary of events over the past decade merged with fear that Putin’s currently military escapades could escalate into something more. The nuclear modernizations have been underway for a long time and the increased training is widely reported but its implications less clear. For all its concern about Russian nuclear strategy, NATO hasn’t said much in public about specific new developments.

A senior NATO official recently said Russia’s Zapad exercise in 2013 was “supposed to be a counter-terrorism exercise but it involved the (simulated) use of nuclear weapons.” In contrast, an earlier private analysis of Zapad-13 said the exercise included “virtually the entire range of conceivable military operations except for nuclear strikes…”

Russian nuclear strategy has been relatively consistent over the past decade. The most recent version, approved by Putin in December 2014, states that Russia “shall reserve for itself the right to employ nuclear weapons in response to the use against it and/or its allies of nuclear and other kinds of weapons of mass destruction, as well as in the case of aggression against the Russian Federation with use of conventional weapons when the state’s very existence has been threatened.”

This formulation is almost identical to the mission described in the 2010 version of the doctrine, which stated that Russia “reserves the right to utilize nuclear weapons in response to the utilization of nuclear and other types of weapons of mass destruction against it and (or) its allies, and also in the event of aggression against the Russian Federation involving the use of conventional weapons when the very existence of the state is under threat.”

Despite many rumors in both 2010 and 2014 that the strategy would incorporate preemptive nuclear strikes, neither document discusses such options (it is unknown what is in the secret versions). On the contrary, the nuclear portion of the strategy doesn’t seem that different from what NATO and the United States say about the role of their nuclear weapons: responding to use of weapons of mass destruction and even significant conventional attacks. The Russian strategy appears to limit the nuclear use in response to conventional attacks to when the “very existence” of Russia is threatened.

Given this defensive and somewhat restrictive nuclear strategy, why do we hear Russian officials throwing around nuclear threats against all sorts of scenarios that do not involve WMD attacks against Russia or threaten the very existence of the country?

For example, why does the Russian Ambassador to Denmark threaten nuclear strikes against Danish warships if they were equipped with radars that form part of the U.S. missile defense system when they would not constitute a WMD attack or threaten the existence of Russia?

Or why does President Putin say he would have considered placing nuclear weapons on alert if NATO had intervened to prevent annexation of the Crimean Peninsula if it were not an WMD attack or threaten the existence of Russia? (Note: Russia already has nuclear weapons on alert, although not in Crimea).

Or why did Russian officials tell U.S. officials that Russia would consider using nuclear weapons if NATO tries to force return of Crimea to Ukrainian control or deploys sizable forces to the Baltic States, if these acts do not involve WMD attacks or threaten the existence of Russia? (Kremlin denied its officials said that).

When officials from a nuclear-armed country make nuclear threats one obviously has to pay attention – especially if made by the president. But these nuclear threats so deviate from Russia’s public nuclear strategy that they are either blustering, or Russia has a very different nuclear strategy than its official documents portray.

Ironically, the more Russian officials throw around nuclear threats, the weaker Russia appears. Whereas NATO and the United States have been reluctant to refer to the role of nuclear weapons in the current crisis (despite what you might hear, the justification for U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe is weaker today than it was before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine) and instead emphasized conventional forces and operations, Russia’s nuclear threats reveal that Russian officials do not believe their conventional forces are capable of defending Russia – even against conventional attack.

That makes it even stranger that Putin is wasting enormous sums of money on maintaining a large nuclear arsenal instead of focusing on modernizing Russia’s conventional forces, as well as using arms control to try to reduce NATO’s nuclear and conventional forces. That would actually improved Russia’s security.

New START Treaty Count: Russia Dips Below US Again

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian deployed strategic warheads counted by the New START Treaty once again slipped below the U.S. force level, according to the latest fact sheet released by the State Department.

The so-called aggregate numbers show that Russia as of March 1, 2015 deployed 1,582 warheads on 515 strategic launchers.

The U.S. count was 1,597 warheads on 785 launchers.

Back in September 2014, the Russian warhead count for the first time in the treaty’s history moved above the U.S. warhead count. The event caused U.S. defense hawks to say it showed Russia was increasing it nuclear arsenal and blamed the Obama administration. Russian news media gloated Russia had achieved “parity” with the United States for the first time.

Of course, none of that was true. The ups and downs in the aggregate data counts are fluctuations caused by launchers moving in an out of overhaul and new types being deployed while old types are being retired. The fact is that both Russia and the United States are slowly – very slowly – reducing their deployed forces to meet the treaty limits by February 2018.

New START Count, Not Total Arsenals

And no, the New START data does not show the total nuclear arsenals of Russia and the United States, only the portion of them that is counted by the treaty.

While New START counts 1,582 Russian deployed strategic warheads, the country’s total warhead inventory is much higher: an estimated 7,500 warheads, of which 4,500 are in the military stockpile (the rest are awaiting dismantlement).

The United States is listed with 1,597 deployed strategic warheads, but actually possess an estimated 7,100 warheads, of which about 4,760 are in the military stockpile (the rest are awaiting dismantlement).

The two countries only have to make minor adjustments to their forces to meet the treaty limit of 1,550 deployed strategic warheads by February 2018.

Launcher Disparity

The launchers (ballistic missiles and heavy bombers) are a different matter. Russia has been far below the treaty limit of 700 deployed launchers since before the treaty entered into effect in 2011. Despite the nuclear “build-up” alleged by some, Russia is currently counted as deploying 515 launchers – 185 launchers below the treaty limit.

In other words, Russia doesn’t have to reduce any more launchers under New START. In fact, it could deploy an additional 185 nuclear missiles over the next three years and still be in compliance with the treaty.

The United States is counted as deploying 785 launchers, 270 more than Russia. The U.S. has a surplus in all three legs of its strategic triad: bombers, ICBMs, and SLBMs. To get down to the 700 launchers, the U.S. Air Force will have to destroy empty ICBM silos, dismantle nuclear equipment from excess B-52H bombers, and the U.S. Navy will reduce the number of launch tubes on each ballistic missile submarine from 24 to 20.

In 2015 the U.S. Navy will begin reducing the number of missile tubes from 24 to 20 on each SSBN, three of which are seen in this July 2014 photo at Kitsap Naval Submarine Base at Bangor (WA). The image also shows construction underway of a second Trident Refit Facility (coordinates: 47.7469°, -122.7291°). Click image for full size,

Even when the treaty enters into force in 2018, a considerable launcher disparity will remain. The United States plans to have the full 700 deployed launchers. Russia’s plans are less certain but appear to involve fewer than 500 deployed launchers.

Russia is compensating for this disparity by transitioning to a posture with a greater share of the ICBM force consisting of MIRVed missiles on mobile launchers. This is bad for strategic stability because a smaller force with more warheads on mobile launchers would have to deploy earlier in a crisis to survive. Russia has already begun to lengthen the time mobile ICBM units deploy away from their garrisons.

Modernization of mobile ICBM garrison base at Nizhniy Tagil in the Sverdlovsk province in Central Russia. The garrison is upgrading from SS-25 to SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24) (coordinates: 58.2289°, 60.6773°). Click image for full size.

It seems obvious that the United States and Russia will have to do more to cut excess capacity and reduce disparity in their nuclear arsenals.

The INF Crisis: Bad Press and Nuclear Saber Rattling

By Hans M. Kristensen

Russian online news paper Vzglaid is carrying a story that wrongly claims that I have said a Russian flight-test of an INF missile would not be a violation of the INF Treaty as long as the missile is not in production or put into service.

That is of course wrong. I have not made such a statement, not least because it would be wrong. On the contrary, a test-launch of an INF missile would indeed be a violation of the INF Treaty, regardless of whether the missile is in production or deployed.

Meanwhile, US defense secretary Ashton Carter appears to confirm that the ground-launched cruise missile Russia allegedly test-launched in violation of the INF Treaty is a nuclear missile and threatens further escalation if it is deployed.

Background

The error appears to have been picked up by Vzglaid (and apparently also sputniknews.com, although I haven’t been able to find it yet) from an article that appeared in a Politico last Monday. Squeezed in between two quotes by me, the article carried the following paragraph: “And as long as Russia’s new missile is not deployed or in production, it technically has not violated the INF.” Politico did not explicitly attribute the statement to me, but Vzglaid took it one step further:

According to Hans Kristensen, a member of the Federation of American Scientists, from a technical point of view, even if the Russian side and tests a new missile, it is not a breach of the contract as long as it does not go into production and will not be put into service.

Again, I didn’t say that; nor did Politico say that I said that. Politico has since removed the paragraph from the article, which is available here.

The United States last year officially accused Russia of violating the INF Treaty by allegedly test-launching a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) to a range that violates the provisions of the treaty. Russia rejected the accusation and counter-accused the United States for violating the treaty (see also ACA’s analysis of the Russian claims).

Conventional or Nuclear GLCM?

The US government has not publicly provided details about the Russian missile, except saying that it is a GLCM, that it has been test-launched several times since 2008, and that it is not currently in production or deployed. But US officials insist they have provided enough information to the Russian government for it to know what missile they’re talking about.

US statements have so far, as far as I’m aware, not made clear whether the GLCM test-launched by Russia is conventional, nuclear, or dual-capable. It is widely assumed in the public debate that it concerns a nuclear missile, but the INF treaty bans any ground-launched missile, whether nuclear or conventional. So the alleged treaty violation could potentially concern a conventional missile.

However, in a written answer to advanced policy questions from lawmakers in preparation for his nomination hearing in February for the position of secretary of defense, Ashton Carter appeared to identify the Russian GLCM as a nuclear system:

Question: What does Russia’s INF violation suggest to you about the role of nuclear weapons in Russian national security strategy?

Carter: Russia’s INF Treaty violation is consistent with its strategy of relying on nuclear weapons to offset U.S. and NATO conventional superiority.

That explanation would imply that US/ NATO conventional superiority to some extent has triggered Russian development and test-launch of the new nuclear GLCM. China and the influence of the Russian military-industrial complex might also be factors, but Russian defense officials and strategists are generally paranoid about NATO and seem convinced it is a real and growing threat to Russia. Western officials will tell you that they would not want to invade Russia even if you paid them to do it; only a Russian attack on NATO territory or forces could potentially trigger US/NATO retaliation against Russian forces.

Possible Responses To A Nuclear GLCM?

The Obama administration is currently considering how to respond if Russia does not return to INF compliance but produces and deploys the new nuclear GLCM. Diplomacy and sanctions have priority for now, but military options are also being considered. According to Carter, they should be designed to “ensure that Russia does not gain a military advantage” from deploying an INF-prohibited system: