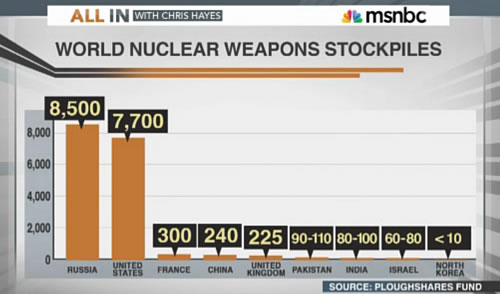

MSNBC On Nuclear Weapons Reduction Efforts

By Hans M. Kristensen

MSNBC used FAS data on the world nuke arsenals in an interview with Ploughshares Fund president Joe Cirincione about how deteriorating US-Russian relations might affect efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals.

The updated weapons estimates on the FAS web site are here.

Detailed profiles of each nuclear weapon state are published as Nuclear Notebooks in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Support our work to produce high-quality estimates of world nuclear forces: Donate here.

SSBNX Under Pressure: Submarine Chief Says Navy Can’t Reduce

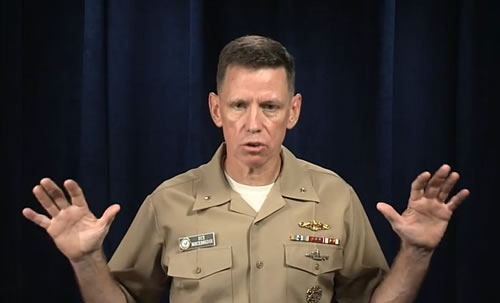

The head of the SSBN fleet, Rear Admiral Richard Breckenridge, says the size of the fleet is really about geography.

By Hans M. Kristensen

In a blog and video on the U.S. Navy web site Navy Live, the head of the U.S. submarine force Rear Admiral Richard Breckenridge claims that the United States cannot reduce its fleet of nuclear ballistic missile submarines further.

This is the third time in three months that Breckenridge has seen a need to go online to defend the size of the SSBN fleet. The first time was in May in reaction to my article about declining SSBN patrols. The second time was in June when he argued that the design chosen for the next-generation SSBN was the only option.

Now Breckenridge argues that the number of operational SSBNs cannot be reduced further if the U.S. Navy is to be able to conduct continuous deployments in the Pacific and Atlantic oceans.

Three public interventions in as many months shows that the plan to spend $70 billion-plus to build a new class of 12 SSBNs is under pressure, and Breckenridge acknowledges that much: “The heat inside the Pentagon right now is probably just as bad” as the summer heat outside and “with sequestration and the fiscal crisis and the budgetary impacts on the DOD topline, there’s a lot of folks looking at how low we can go with the SSBN force.”

But the 12 planned next-generation SSBNs “is the floor,” Breckenridge claims.

A Matter of Geography

It is not the first time that the navy has argued that what it has or plans to build is the absolute minimum and that anything less would undermine U.S. national security. But why does the navy plan to build 12 new SSBNs?

The answer, Breckenridge says, “really is a matter of geography.”

“For us to be able to conduct two-oceans strategic deterrence requires a bare minimum number of SSBNs of a force of twelve,” he claims. To get to that number, Breckenridge begins with a series of broad assumptions and claims about deterrence and SSBN operations.

“There are two important points for you to know for how strategic deterrence works. The first is those SSBNs have to invincible. They have to be survivable at sea. The adversary can’t find them. Hidden and unable to be detected. And second, they have to be within range of targets that matter to the adversary, that we can hold at risk to deter or dissuade them from ever considering attacking our homeland.”

“Geography requires that 60-40 split of our SSBN force,” he says. “A few more in the Pacific than in the Atlantic to be able to meet those two criteria for our nation’s defense.”

I May Not Know Much About Geography, But…

That explanation might work well for a public relations sound bite, but I hope the Pentagon folks examining the SSBN force level probe a little deeper.

First of all, why does two-oceans strategic deterrence require 12 SSBNs? Three decades ago it required 41. Two decades ago it required 33. One decade ago it required 18. Now it requires 14. And in two decades it will still require 12 SSBNs, according to the navy.

Breckenridge explains that out of 14 SSBNs currently in the fleet, 11 are on average operational but it sometimes drops to 10, with the rest undergoing maintenance (see here for article about SSBN operations). Those 10 operational SSBNs (six in the Pacific and four in the Atlantic) “is the bare minimum required to provide uninterrupted alert coverage for the combatant commander,” according to Breckenridge.

He says that the current SSBN fleet is a “lean” force. But there is nothing lean about it: the fleet is bigger than that of any other country; each Ohio-class SSBN carries more missiles than any SSBN of any other country can carry; each Trident II D5 missile can be loaded with more warheads than SLBMs of any other country; each missile is more accurate, lethal, and reliable than any other country’s SLBM; and the U.S. SSBN fleet conducts three times more deterrent patrols than any other country. The force is bloated both in terms of size, loadout, capability, and operations.

Britain and France both manage to ensure their security each with four SSBNs operating from a single base. In contrast, the “bare minimum” force that Breckenridge advocates of 10 deployable next-generation SSBNs will be able to carry 160 SLBMs with up to 1,280 warheads – more than Britain, France, China, Pakistan, India and Israel have in their total stockpiles, combined! In fact, that 10-SSBN force would be able to carry more than the entire deployed strategic warhead level proposed by President Obama in his recent Berlin speech.

Like Russia’s future SSBN fleet, the U.S. Navy could easily operate eight SSBNs from two bases. That would ensure that six next-generation SSBNs would always be deployed or ready to deploy on short notice. Combined they would be armed with nearly 100 long-range missiles capable of carrying up to 760 warheads that can hold a risk the full range of targets. Try to put 760 Xs – even 100 – on a map of Russia or China and tell me why that would be insufficient for deterrence in this day and age.

Equally important, where does the requirement to provide “uninterrupted alert coverage” on such a scale come from? What is the scenario? And why is it necessary – more than two decades after the end of the Cold War – “to provide uninterrupted alert coverage for the combatant commander”?

The requirement comes from the nuclear strategists that create the objectives and tasks that military planners translate into a “family” of nuclear strike plans against half a dozen adversaries. Those requirements are what Breckenridge is trying to meet with his 12 SSBNs.

But there is nothing in the strategic threat environment of today’s world that requires U.S. SSBNs to “provide uninterrupted alert coverage” under normal circumstances. Indeed, the new nuclear weapons employment policy issued by the White House last month concluded that “the potential for a surprise, disarming nuclear attack is exceedingly remote” and ordered DOD to “reduce the role of launch under attack” in nuclear planning.

Consequently, the SSBNs could be taken off alert and their readiness level significantly reduced while still providing basic operational training to the crews. The annual number of SSBN deterrent patrols has already declined by more than half over past decade and may drop further in the next years.

The Pentagon is already so confident in the capability of the SSBN fleet that it has concluded that Russia “would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its nuclear forces” because it would have “little to no effect” on the U.S. ability to retaliate with a devastating strike.

Despite Russian modernizations, the size of its strategic force is declining and will continue to decline over the next decade with or without a new arms reduction agreement. And there is no indication that China, despite its own modernizations, is planning to increase the size of its strategic nuclear force to anything remotely comparable to the force level proposed by President Obama.

Yet for the next two decades, until 2031 when the first next-generation SSBN is scheduled to sail on patrol, the navy plans to continue to operate all 14 Ohio-class SSBNs. Of those, the 12 operational boats currently carry 288 Trident II D5 missiles, which will be reduced to no more than 240 deployed missiles by 2018 under the New START Treaty. But that is 80 missiles (50 percent) more than the 160 missiles that will be deployed on the 10 operational next-generation SSBNs.

Why does the navy plan to sail for two decades with 50 percent more missiles than it has already decided it can do with on the next-generation SSBN?

This is even more puzzling because the plan for 12 SSBNs with 16 missiles each “did not assume any specific changes to targeting or employment guidance,” STRATCOM commander Robert Kehler testified before Congress in November 2011.

Read that again: the significant reduction planned for deployed sea-launched ballistic missiles did not require any specific changes to targeting or employment guidance!

That statement indicates that there is significant excess capacity on the SSBN fleet. And it is mind-boggling that Congress did not even notice it.

Conclusions and Recommendations

I may not know much about geography but it appears the SSBN force is significantly in excess of what is required now or planned for later. A force of 8-10 SSBNs with six operational boats would provide more than enough capacity to perform adequate deterrence deployments in Pacific and Atlantic.

Shedding the excess SSBN capacity now would save billions of dollars in construction and operational costs and make it easier to persuade Russia to reduce it forces as well. That seems to be a double win.

Part of the problem with debating SSBN operations and the war plans they are tasked under is that everything is so secret that there essentially is no way to independently verify Breckenridge’s claims. All we have are bits a pieces and common sense.

And because of this secrecy, and the almost religious aura of legitimacy that the SSBN force enjoys, many lawmakers blindly accept the claims and do not question the size of the force or the assumptions for its operations. That ends up costing the U.S. taxpayers billions of dollars.

The issue facing us is not whether the SSBN force provides an important contribution to U.S. national security or not. It does. The issue is what composition it needs to have and how it needs to operate to provide sufficient security at an affordable price.

Air Force Intelligence Report Provides Snapshot of Nuclear Missiles

By Hans M. Kristensen

The U.S. Air Force National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) has published its long-awaited update to the Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat report, one of the few remaining public (yet sanitized) U.S. intelligence assessment of the world nuclear (and other) forces.

Previous years’ reports have been reviewed and made available by FAS (here, here, and here), and the new update contains several important developments – and some surprises.

Most important to the immediate debate about further U.S.-Russian reductions of nuclear forces, the new report provides an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

Another new development is a significant number of new conventional short-range ballistic missiles being deployed or developed by China.

Finally, several of the nuclear weapons systems listed in a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing are not included in the NASIC report at all. This casts doubt on the credibility of the AFGSC briefing and creates confusion about what the U.S. Intelligence Community has actually concluded.

Russia

The report estimates that Russia retains about 1,200 nuclear warheads deployed on ICBMs, slightly higher than our estimate of 1,050. That is probably a little high because it would imply that the SSBN force only carries about 220 warheads instead of the 440, or so, warheads we estimate are on the submarines.

“Most” of the ICBMs “are maintained on alert, capable of being launched within minutes of receiving a launch order,” the report states. This excessive alert posture is similar to that of the United States, which has essentially all of its ICBMs on alert.

The report also confirms that although Russia is developing and deploying new missiles, “the size of the Russia missile force is shrinking due to arms control limitations and resource constraints.”

Unfortunately, the report does not clear up the mystery of how many warheads the SS-27 Mod 2 (RS-24, Yars) missile carries. Initially we estimated thee because the throw-weight is similar to the U.S. Minuteman III ICBM. Then we considered six, but have recently settled on four, as the Strategic Rocket Forces commander has stated.

The report states that “Russia tested a new type of ICBM in 2012,” but it undercuts rumors that it not an ICBM by listing its range as 5,500+ kilometers. Moreover, in an almost direct rebuttal of recent allegations that Russia is violating the INF Treaty by developing an Intermediate-range ballistic missile, the report concludes: “Neither Russia nor the United States produce or retain any MRBM or IRBM systems because they are banned by the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty, which entered into force in 1988.”

The report also describes how Russian designers are working to modify missiles to overcome U.S. ballistic missile defense systems. The SS-27 Mod 1 (Topol-M) deployed in silos at Tatishchevo was designed with countermeasures to ballistic missile systems, and Russian officials claim that a new class of hypersonic vehicle is being developed to overcome ballistic missile defense systems, according to NASIC.

The report also refers to Russian press report that a rail-mobile ICBM is being considered, and that a new “heavy” ICBM is under development.

One of the surprises in the report is that SS-N-32/Bulava-30 missile on the first Borei-class SSBN is not yet considered fully operational – at least not by NASIC. The report lists the missile as in development and “not yet deployed.”

Another interesting status is that while the AS-4 and AS-15 nuclear-capable air-launched cruise missiles are listed as operational, the new Kh-102 nuclear cruise missile that Russian officials have said they’re introducing is not listed at all. The Kh-102 was also listed as already “fielded” by a recent U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing.

Finally, while the report lists the SS-N-21 sea-launched cruise missile as operational, it does not mention the new Kalibr cruise missile for the Yasen-class attack submarine that U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command recently listed a having been “fielded” within the past five years.

China

The NASIC report states that the Chinese ballistic missile force is expanding both in size and types of missiles.

Deployment of the DF-31A (CSS-10 Mod 2) ICBM continues at a slow pace with “more than 15” launchers deployed six years after the system was first introduced.

Despite many rumors about a new DF-41 ICBM, the NASIC report does not mention this system at all.

Deployment of the shorter-range DF-31 (CSS-10 Mod 1) ICBM, on the contrary, appears to have stalled or paused, with only 5-10 launchers deployed seven years after it was initially introduced (see my recent analysis of this trend here). Moreover, the range of the DF-31 is lowered a bit, from 7,200+ km in the 2009 report to 7,000+ in the new version.

Medium-range nuclear missiles include the DF-21 (CSS-5) (in two versions: Mod 1 and Mod 2, but with identical range etc.) and the old DF-3A (CSS-2), which is still listed as deployed. Only 5-10 launchers are left, probably in a single brigade that will probably convert to DF-21 in the near future.

An important new development concerns conventional missiles, where the NASIC report states that several new systems have been introduced or are in development. This includes a “number of new mobile, conventionally armed MRBMs,” apparently in addition to the DF-21C and DF-21D already known. As for the DF-21D anti-ship missile, report states that “China has likely started to deploy” the missile but that it is “unknown” how many are deployed.

More dramatic is the development on five new short-range ballistic missiles, including the CSS-9, CSS-11, CSS-14, CSS-X-15, and CSS-X-16. The CSS-9 and CSS-14 come in different versions with different ranges. The CSS-11 Mod 1 is a modification of the existing DF-11, but with a range of over 800 kilometers (500 miles). None of these systems are listed as nuclear-capable.

Concerning sea-based nuclear forces, the NASIC report echoes the DOD report by saying that the JL-2 SLBM for the new Jin-class SSBN is not yet operational. The JL-2 is designated as CSS-NX-14, which I thought it was a typo in the 2009 report, as opposed to the CSS-NX-3 for the JL-1 (which is also not operational).

NASIC concludes that JL-2 “will, for the first time, allow Chinese SSBNs to target portions of the United States from operating areas located near the Chinese coast.” That is true for Guam and Alaska, but not for Hawaii and the continental United States. Moreover, like the DF-31, the JL-2 range estimate is lowered from 7,200+ km in the 2009 report to 7,000+ km in the new version. Earlier intelligence estimates had the range as high as 8,000+ km.

One of the surprises (perhaps) in the new report is that it does not list the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile, which was listed in the U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command briefing as a nuclear cruise missile that had been “fielded” within the past five years.

Concerning the overall size of the Chinese nuclear arsenal, there have been many rumors that it includes hundreds or even thousands of additional warheads more than the 250 we estimate. STRATCOM commander has also rejected these rumors. To that end, the NASIC report lists all Chinese nuclear missiles with one warhead each, despite widespread rumors in the news media and among some analysts that multiple warheads are deployed on some missiles.

Yet the report does echo a projection made by the annual DOD report, that “China may also be developing a new road-mobile ICBM capable of carrying a MIRV payload.” But NASIC does not confirm widespread news media rumors that this system is the DF-41 – in fact, the report doesn’t even mention the DF-41 as in development.

As for the future, the NASIC report repeats the often-heard prediction that “the number of warheads on Chinese ICBMs capable of threatening the United States is expected to grow to well over 100 in the next 15 years.” This projection has continued to slip and NASIC slips it a bit further into the future to 2028.

Pakistan

Most of the information about the Pakistani system pretty much fits what we have been reporting. The only real surprise is that the Shaheen-II MRBM does still not appear to be fully deployed, even though the system has been flight tested six times since 2010. The report states that “this missile system probably will soon be deployed.”

India

The information on India also fits pretty well with what we have been reporting. For example, the report refers to the Indian government saying the Agni II IRBM has finally been deployed. But NASIC only lists “fewer than 10” Agni II launchers deployed, the first time I have seen a specific reference to how many of this system are deployed. The Agni III IRBM is said to be ready for deployment, but not yet deployed.

North Korea

The NASIC report lists the Hwasong-13 (KN-08), North Korea’s new mobile ICBM, but confirms that the missile has not yet been flight tested. It also lists an IRBM, but without naming it the Musudan.

The mysterious KN-09 coastal-defense cruise missile that U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command recently listed as a new nuclear system expected within the next five years is not mentioned in the NASIC report.

Full NASIC report: Ballistic and Cruise Missile Threat 2013

See also previous NASIC reports: 2009 | 2006 | 1998

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Russian Missile Test Creates Confusion and Opposition in Washington

The recent test-launch of a modified Russian ballistic missile has nuclear arms reduction opponents up in arms with claims that Russia is fielding a new missile in violation of arms control agreements and that the United States therefore should not pursue further reductions of nuclear forces.

The fact that the Russian name of the modified missile – Rubezh – sounds a little like rubbish is a coincidence, but it fits some of the complaints pretty well.

Although many of the facts are missing – what the missile is and what the U.S. Intelligence Community has concluded – public information and statements indicate that the missile is a modified RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2) with intercontinental range.

Whatever the missile is, it is certainly no reason for why the United States should not seek to reduce U.S. and Russian nuclear forces further. On the contrary, the continued modernization of nuclear weapons underscores why it is important that the United States continues its push for reducing the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

The Accusations

Under the headline “Russian Aggression: Putin violating nuclear missile treaty,” the article on Washington Times Free Beacon web site accuses Russia of being engaged in “a major violation” of the terms of the Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty signed with the United States in 1987.

The treaty bans all nuclear ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with range between 500 and 5,500 km (about 300-3,400 miles).

Claims of Russian cheating are frequent in the Washington arms control debate – just as claims about U.S. cheating is frequent in the Moscow arms control debate – and the ones in the article are largely consistent with the claims made by Mark Schneider, a former DOD official and now with the National Institute for Public Policy.

The “new” in the article is that it quotes “one official” saying: “The intelligence community believes it’s an intermediate-range missile that [the Russians] have classified as an ICBM because it would violate the INF treaty.” In total, “Two U.S. intelligence officials said the Yars M is not an ICBM,” according to the article.

Two members of Congress, House Armed Services Committee chairman Howard “Buck” McKeon (R-CA) and House Permanent Select Intelligence Committee chairman Mike Rodgers (R-MI), have written President Obama about alleged Russian violations. They complain that they haven’t received a response but the administration says it deals with treaty compliance issue directly with Russia and informs Congress accordingly.

Accusations Disputed

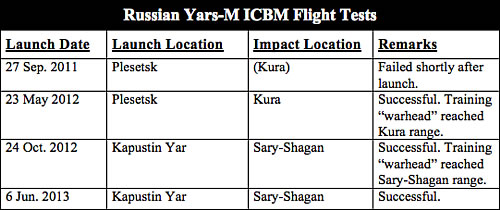

The accusations that the Yars-M is not an ICBM and in violation of the INF Treaty are disputed by Russian officials and, interestingly, previous flight tests of the missile itself.

To its credit, the Washington Times took the trouble of asking Colonel General Victor Yesin about the missile. Yesin is former Chief of Staff of the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces and apparently a consultant to the Chief of the General Staff. But Yesin clearly disputed the claim by the U.S. intelligence officials, saying that the Yars-M is a “Topol-M class ICBM” and that “its range is over 5,500 km.”

That assessment fits the description made by a source in the General Staff in November 2012, following the first Yars-M launch from Kapustin Yar in October 2012 and news media rumors that Russia was developing a “fundamentally new missile.” “There are no fundamentally new missiles ‘on the approach’ for [the Russian Strategic Rocket Forces]. We are talking about modernizing the existing Yars class by improving the warhead,” he told Interfax and explained:

“Take the Layner [modification of the SS-N-23] sea-based intercontinental ballistic missile, reported by some media to be a completely new missile. It is in fact a Sineva. Only the warhead is new. Novelty lies in greater missile defense penetration capabilities, achieved owing to, among other things, a greater number of re-entry vehicles (boyevoy blok) in the warhead. The same applies to the prototype missile that was successfully launched from Kapustin Yar (Astrakhan Region) recently. There is nothing new in the missile itself. Only the ‘head’ is new. Its creators went down the same route as the designers of the Layner.”

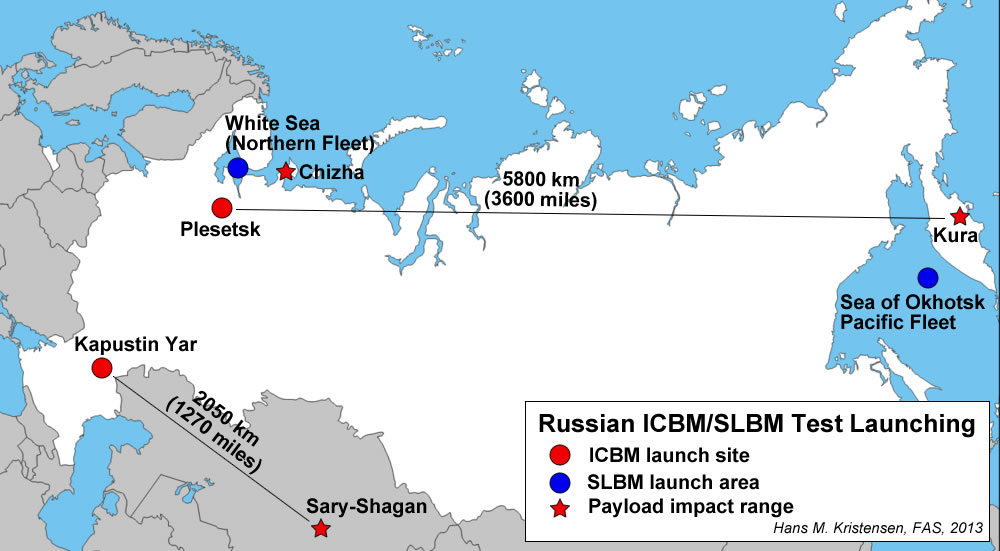

Moreover, the claim that the short flight range of the missile test launched from Kaputsin Yar in June 2013 would indicate that the Yars-M is not an ICBM ignores that an earlier flight test of the missile last year flew 5,800 kilometers from Plesetsk north of Moscow to the Kura test range on the Kamchatka Peninsula (see table).

After the May 2012 flight test, Colonel-General Vladimir Zarudnitsky of the General Staff said: “As part of the approved plan of your building the armed forces of the Russian Federation last night made a promising test launch rocket system” Frontier “with an intercontinental ballistic missile high-precision shooting.” (Emphasis added).

Col. Vadim Koval, a Russian defense ministry spokesperson, said “the main goals and tasks of the launch consisted of receiving experimental data on confirming the correctness of the scientific-technical and technological decisions in developing the intercontinental ballistic missile as well as checking the performance and determining the technical characteristics of its systems and components.” (Emphasis added).

Rather than an entirely new missile, Koval explained further, “This missile is being created by using and developing, to the maximum extent, already existing new capacities and technological solutions, which were obtained in the development of fifth generation missile complexes, which substantially reduces the terms and expenditures on its creation.”

After the successful initial launch from Plesetsk, the second test was moved to Kapustin Yar apparently to test the capability of the Yars-M payload to evade ballistic missile defense systems. An industry sources told Interfax that, “The use of new fuel is one of the features of the missile. It reduces boost phase engine operation time. Consequently, the missile’s capabilities to penetrate missile defense will go up.”

It is rare, but not unheard of, that ICBMs are launched from Kapustin Yar into the Sary-Sagan test range. It appears to happen when ICBM payloads are being tested against missile defense systems. In addition to the recent tests of the modified SS-27, an SS-25 was test launched from the site on June 7, 2012. The test flight verified the “extended service life” of the SS-25 and “the latest test of an ICBM combat payload.” During the test “information was received which in future will be used in the interests of developing effective means for overcoming missile defense,” according to the Russian Ministry of Defense.

After the June 2013 test, Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin, called the modified SS-27 a “missile defense killer.”

It is not unusual that ballistic missiles with intercontinental range are test-flown in a compressed trajectory with much shorter range. That doesn’t make them less than strategic weapons, however. In March 2006, for example, the U.S. Navy launched a Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missile with a range of well over 7,400 kilometer (4,000 miles) in a compressed trajectory of 2,200 kilometers (1,380 miles) – about the same range as the Yars-M test on June 6, 2013. No one has suggested that the Trident II D5 therefore is an INF weapon.

The USS Tennessee (SSBN-734) launches a Trident II D5 SLBM on March 2, 2005, on a compressed trajectory of only 2,200 km – about the same range as the Yars-M test in June 2013.

Conclusions and Recommendations

If there are Russian violations of the INF Treaty, then the United States certainly should raise it directly with Moscow.

But the claim that the Yars-M missile flight-tested on June 6 to a range of 2,050 kilometers is an intermediate-range ballistic missile in violation of the INF treaty seems strange since the same missile apparently was flight tested to an ICBM range of 5,800 kilometers just a year ago.

Of course, we don’t know who the U.S. intelligence officials cited in the Washington Times article are, if what they say is accurate, and to what extent it reflects a coordinated assessment by the U.S. Intelligence Community. We may learn more about the Yars-M in the future.

But several Russian government, military, and industry officials have consistently stated that the Yars-M is not a new missile but a modification of the RS-24 Yars (SS-27 Mod 2) and that it has intercontinental range.

The intension of the allegations in the article seems clear: to create doubts about further reductions of U.S. nuclear forces. One of the “officials” quoted in the article directly questions: “How can President Obama believe [the Russians] are going to live up to any nuclear treaty reductions when he knows they are violating the INF treaty by calling one of their missiles something else?”

The thought that Americans would use INF treaty allegations to argue against reducing the number of strategic nuclear weapons that can hit the United States seems kind of bizarre. After all, under current Russian war plans, many of the 400-500 warheads President Obama has proposed can be offloaded under a new agreement, are most likely currently tasked to hold at risk several hundred targets in the United States – including some in California and Michigan.

Since Russia – unlike the United States – is already below the New START Treaty limit on deployed nuclear weapons and likely to drop further before the treaty enters into force in 2018, it seems like a no-brainer that it is in the U.S. interest to nurture that trend by reducing its own forces further.

This is even more important because the very reason some Russian officials could potentially be tempted to argue that an INF-missile was needed is that China is modernizing of its medium-range missile forces. Ironically, many of those in the United States who make the accusations about Russian INF violations are the same people who also warn about China’s nuclear modernization.

What the article completely seems to miss is that the only way that China and smaller nuclear weapons states may be persuaded to place limits on their nuclear arsenals is if the United States and Russia take bold steps to reduce their still enormous nuclear arsenals. Why then nitpick about dubious INF accusations to block that from happening?

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

New Nuclear Weapons Employment Guidance Puts Obama’s Fingerprint on Nuclear Weapons Policy and Strategy

President Barack Obama’s Berlin speech failed to capture the nuclear disarmament spirit of the Prague speech four years ago. And no wonder. Back then Obama had to contrast with the Bush administration’s nuclear policies. This time Obama had to upstage his own record.

The only real nuclear weapons news that was included in the Berlin speech was a decision previously reported by the Center for Public Integrity that the administration is pursuing an “up to a one-third reduction” in deployed nuclear weapons established under New START.

Instead, the real nuclear news of the day were the results of the Obama administration’s long-awaited new guidance on nuclear weapons employment policy that was explained in a White House fact sheet and a more in-depth report to Congress.

From a nuclear arms control perspective, the new guidance is a mixed bag.

One the one hand, the guidance directs pursuit of additional reductions in deployed strategic warheads and less reliance on preparing for a surprise nuclear attack. On the other hand, the guidance reaffirms a commitment to core Cold War posture characteristics such as counterforce targeting, retaining a triad of strategic nuclear forces, and retaining non-strategic nuclear weapons forward deployed in Europe.

Pursue Additional Reductions

The top news is that the administration has decided that it can meet its security obligations with “up to one-third” fewer deployed strategic warheads that it is allowed under the New START treaty. That would imply that the guidance review has concluded that the United States needs 1,000-1,100 warheads deployed on land- and sea-based strategic warheads, down from the 1,550 permitted under the New START treaty.

It is not entirely clear from the public language, but it appears to be so, that these additional reductions will be pursued in negotiations with Russia rather than as reciprocal unilateral reductions.

Even though the nuclear weapons employment policy would allow for reductions below the New START Treaty levels, it does not direct any changes to the currently deployed forces of the United States. That is up to the follow-on process of the Secretary of Defense producing an updated Nuclear Weapons Employment Policy (NUWEP) appendix to the Guidance for the Employment of the Force (GEF), and the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff then producing an update to the nuclear supplement to the Joint Strategic Capabilities Plan (JSCP-N).

These updates will inform the Commander of STRATCOM on how to direct the Joint Functional Component Command Global Strike (JFCC-GS) to update the strategic war plan (OPLAN 8010-12), and Geographic Combatant Commanders such as the Commander of European Command to update their regional plans.

So if an when Russia agrees to cutting its deployed strategic warheads by up to one third, it could take several years before President Obama’s guidance actually affects the nuclear employment plans.

Already now, many news articles covering the Berlin speech misrepresent the “cut” by saying it would reduce the U.S. “arsenal” or “stockpile” by one third. But that is not accurate. The envisioned one-third reduction of deployed strategic warheads will not in and of itself destroy a single nuclear warhead or reduce the size of the bloated U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals.

Reduce Launch Under Attack

The new guidance recognizes, which is important although late, that the possibility of a disarming surprise nuclear attack has diminished significantly since the Cold War. Therefore, the guidance “directs DoD to examine further options to reduce the role of Launch Under Attack plays in U.S. planning, while retaining the ability to Launch Under Attack if directed.”

Launch under attack is the capability to be able to launch nuclear forces after detection that an adversary has initiated a major nuclear attack. Because it only takes about 30 minutes for an ICBM to fly from Russia over the North Pole, Launch Under Attack (LOA) has meant keeping hundreds of weapons on alert and ready to launch within minutes after receiving the launch order.

Barack Obama promised during his election campaign in 2007 that he would work with Russia to take nuclear weapons off “hair-trigger alert,” but the Nuclear Posture Review instead decided to continue the existing readiness of nuclear forces. Now the DOD is directed to study how to reduce LOA in nuclear strike planning but retain some LOA capability.

The guidance does not explicitly say – to the extent it is covered by the DOD report – that nuclear force will be retained on alert. The NPR makes such a statement clearly. The DOD guidance report only states that the practice of open-ocean targeting should be retained so that a weapon launched by mistake would land in the open ocean.

Despite the decision to reduce deployed strategic warheads and reduce Launch Under Attack, the guidance hedges against the change by stating that “the maintenance of a Triad and the ability to upload warheads ensures that, should any potential crisis emerge in the future, no adversary could conclude that any perceived benefits of attacking the United States or its Allies and partners are outweighed by the costs our response would impose on them.”

Counterforce Reaffirmed

The new guidance reaffirms the Cold War practice of using nuclear forces to hold nuclear forces at risk. According to the DOD summary, the new guidance “requires the United States to maintain significant counterforce capabilities against potential adversaries” and explicitly “does not rely on a ‘counter-value’ or ‘minimum deterrence’ strategy.”

This reaffirmation is perhaps the single most important indicator that the new guidance fails to “put and end to Cold War thinking” as envisioned by the Prague speech.

Because “counterforce is preemptive or offensively reactive,” in the words of a STRATCOM-led study from 2002, reaffirmation of nuclear counterforce reaffirms highly offensive planning that is unnecessarily threatening for deterrence to work in the 21st Century. This condition is exacerbated because the reaffirmation of counterforce is associated with a decision to retain – albeit at a reduced level – the ability to Launch Under Attack if directed (see below).

The “warfighting” nature of nuclear counterforce drives requirements for Cold War-like postures and technical and operational requirements that sustain nuclear competition between major nuclear powers at a level that undercuts efforts to reduce the role and numbers of nuclear weapons.

No Sole Purpose…But

Four years after the Nuclear Posture Review decided that the United States could not adopt a sole purpose of nuclear weapons to deter only nuclear attacks, the new guidance reaffirms this rejection by saying “we cannot adopt such a policy today.”

Even so, the guidance apparently reiterates the intention to work towards that goal over time. And it directs the DOD to undertake concrete steps to further reducing the role of nuclear weapons.

Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons

The decisions regarding non-strategic nuclear weapons are disappointing because they fail to progress the issue. In fact, the White House fact sheet explicitly states that the guidance review did not address forward deployed non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe.

Even so, the guidance decides to retain a forward-based posture in Europe until NATO agrees it is time to change the posture. The last four years have shown that NATO is incapable of doing so because a few eastern NATO countries cling to Cold War perceptions about nuclear weapons in Europe that blocks progress.

In effect, the lack of initiative now means countries like Lithuania now effectively dictate U.S. policy on non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Hedging Against Hedging

The guidance also directs that the United States will continue to retain a large reserve of non-deployed warheads to hedge against technical failures in deployed warheads.

This both means enough extra warhead types within each leg to hedge against another warhead on that leg failing, as well as keeping enough extra warheads for each leg to hedge against failure of one of the warheads on another leg.

Now that warhead life-extension programs are underway, the guidance directs that DOD should only retain hedge warheads for those modified warheads until confidence is attained. This is a little cryptic because why would the DOD not do that, but the intension seems to be to avoid keeping the old hedge warheads longer than necessary.

Moreover, the guidance also states that all of the hedging against technical issues will provide enough reserve warheads to allow upload of additional warheads – including those removed under the New START Treaty – in response to a geopolitical development somewhere in the world.

This all suggests that we should not expect to see significant reductions in the hedge in the near future but that much of the current hedging strategy will be in place for the next decade and a half.

Conclusions

The Obama administration deserves credit for seeking further reductions in nuclear forces and the role of Launch of Warning in nuclear weapons employment planning. A White House fact sheet and a DOD report provide important information about the new nuclear weapons employment guidance, a controversial issue on which previous administrations have largely failed to brief the public.

The DOD’s report on the new guidance reiterates that it is U.S. policy to “seek the peace and security of a world without nuclear weapons,” but helpfully reminds that “it is imperative that we continue to take concrete steps toward it now.” This is helpful because Obama’s recognition in Prague that the goal of a world free of nuclear weapons might not be achieved in his lifetime has been twisted by opponents of reductions and disarmament to mean an affirmative “not in my lifetime!”

The guidance directs that nuclear “planning should focus on only those objectives and missions that are necessary for deterrence in the 21st century.” The force should be flexible enough, the guidance says, to be able to respond to “a wide range of options” by being able to “threaten credibly a wide range of nuclear responses if deterrence should fail.”

Unfortunately, the public documents do not shed any light on what those objectives and missions are or which ones have been deemed no longer necessary.

Instead, the official descriptions of the new guidance show that its retains much of the Cold War thinking that President Obama said in Prague four years ago that he wanted to put an end to. The reaffirmation of nuclear counterforce and retention of nuclear weapons in Europe are particularly disappointing, as is the decision to retain a large reserve of non-deployed warheads partly to be able to reverse reductions of deployed strategic warheads achieved under the New START Treaty.

In the coming months and years, these decisions will likely be used to justify expensive modernizations of nuclear forces and upgrades to nuclear warheads that will prompt many to ask what has actually changed.

Background: US Nuclear Forces, 2013 – Russian Nuclear Forces, 2013 – Reviewing Nuclear Guidance – From Counterforce to Minimal Deterrence

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Radiological Ray Gun: More Buck Rogers Fantasy than Risk to Real People

The June 18th arrest of two men for allegedly plotting to build a bizarre yet potentially deadly radiological device once again highlights the potential nexus of non-state actors with so-called weapons of mass destruction (WMD). However, much like this year’s troika of ricin-laced letters addressed to government facilities (including one to the CIA) and public officials (all three incidents targeted President Obama at his White House address), this most recent plot reveals the historical rarity and non-lethality of non-state actors and their behaviors with radiological weapons and agents. While the potential for catastrophe posed by terrorist use of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons deserves ongoing and serious attention, recent events remind us how public apprehension is sometimes founded more in fear than reality; indeed, reactions based on fear are capable of far more disruption than the physical reality of the event itself. The role of science-based organizations such as the Federation of American Scientists is to educate the public about the real risks. [box border=”full”]The methodologies and data sets used in this article, augmented by several others of each, will be discussed in a two day professional education summer course, “Terrorism Analysis: Quantitative and Qualitative Research Methodologies and Tools” held at George Mason University in Fairfax, VA on July 25-26, 2013. This non-credit course introduces participants to state-of-the art analytical techniques, research methods, and cutting-edge databases used by the industry for the study of terrorism. Course participants gain a detailed understanding of single and multi-methodological techniques, learning how to develop analytical tools applicable to the needs of those responsible for preventing, preparing, responding to, or predicting terrorism. Highlights include how to use these research techniques to identify previous and emerging trends in terrorist activities and to cogently assess the potential role of WMD in terrorism. Register now for the “early bird” discount – 25 percent less than the listed fee. For more information and to register, please visit the course page.[/box]

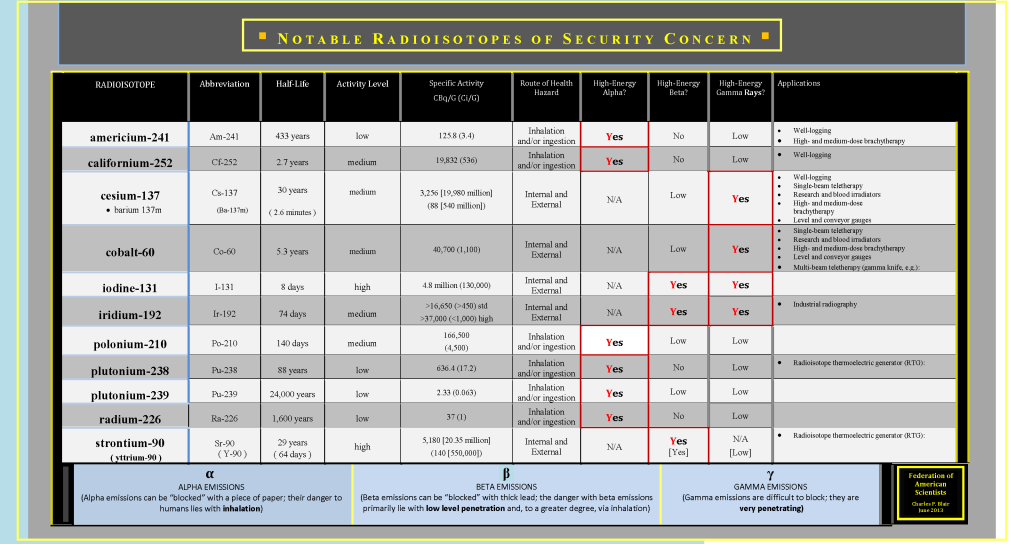

Of the CBRN threats, the nuclear threat is undoubtedly truly catastrophic because a nuclear weapon can cause massive destruction, but obtaining a nuclear weapon or the fissile material to make such a weapon is very hard to do. In comparison, radiological sources are far more common, but most of them would cause little or no harm to human health if dispersed by a radiological weapon because there is not enough radioactive material contained in the vast majority of each of these sources. And even those radiological sources containing highly radioactive materials would pose great difficulties for terrorists to use because they would hazard exposing themselves to lethal ionizing radiation. These latter issues, and others outlined below, are very relevant to the recent radiological plot.

According to Tuesday’s radiological- related FBI affidavit, Glenford Scott Crawford, an industrial mechanic who reportedly self-identified as a member of the Ku Klux Klan, plotted to build “a mobile, remotely operated, radiation emitting device capable of killing human targets silently and from a distance with lethal doses of radiation.” Crawford, along with Eric J. Freight, an electronics specialist, allegedly succeeded in constructing a “remote initiation device,” but according to the FBI’s affidavit had not yet “weaponized” the device before their arrest. Monitored by the FBI since April 2012, the duo never obtained a radiological source for their device.

While the affidavit lacks a definitive answer on whether or not Crawford and Freight sought to craft a device that would emit x-rays or were trying to obtain a radioactive source to emit radiation, it appears likely that the former is the case. Significant differences exist between an x-ray emitting device and a radioactive source that emits gamma radiation. The first distinction is that an x-ray device needs electrical power to work but a radioactive source is always “on” and emitting radiation due to the natural process of radioactive decay. The other salient distinction is that if Crawford and Freight had sufficient electrical power they could—in principle—have a device capable of emitting potent radiation from a relatively far off distance— such as several meters. That is, the output of the x-ray device would depend on the electrical power available. In contrast, a radioactive source would not be able to boost its potency with the use of electrical power because the potency depends on the properties of the radioisotope and the natural process of decay.

Active in two small towns near Albany, New York, over the past year, Crawford and Freight unwittingly dealt with at least one FBI planted “confidential human source” who posed as a potential financer of the project and buyer of the finished device. Tuesday’s arrests came as the suspects, “planned to conduct a test-run of the triggering system.”

Contrary to public perceptions of radiological weapons, or “dirty bombs,” as weapons of mass destruction, experts correctly note that radiological attacks could not produce mass destruction or mass casualties. This is because when dispersed the radioactive material would be spread out over a wide area and thus would be far less potent than material concentrated in the original source. Moreover, trying to use the original source as a lethal means of exposing large numbers of people from a distance would be hard to do because the potency of the ionizing radiation would decrease the farther the source is from the targeted population. Specifically, it would decrease as one divided by the distance squared. For example, an unshielded source that is lethal at one-meter distance would have a potency of one one-hundredth when the source is ten meters away and would not likely pose a lethal threat.

Thus, the reality is that radiological devices are “weapons of mass disruption” – likely to directly generate few, if any, immediate casualties via ionizing radiation, yet capable of precipitating mass panic and large-scale economic disruption.

Similarly, belying public apprehension of radiological terrorism, there is the extreme rarity of such events; indeed, terrorist use of harmful radioisotopes, according to open-source data, numbers no more than three incidents—none of which generated casualties. If other non-state actors are included, those not considered terrorists, but include, for example, lone actors seeking revenge, recorded radiological incidents are more numerous, but still strikingly rare. A finding from a 2009 study—conducted by a University of Maryland (UMD) research team that included this author, combined with research into radiological events occurring subsequent to the studies completion—reveals only 19 recorded radiological incidents by non-state actors. (Maintaining harmony with the UMD study, the criteria for inclusion excluded hoaxes and “clear cases of smuggling or transfer activity with no apparent links to end-users.”)

Taking a brief pause, here are some basic nuclear physics useful when putting this event in the proper context. The entire universe consists of less than 120 elements; 92 are naturally occurring. Each element contains a unique number of protons. While their number of protons remains the same, some elements possess different numbers of neutrons. These are called isotopes. With neutrons in greater quantity than those found in lead and bismuth, are isotopes prone to natural decay. Such unstable isotopes are referred to as radioisotopes, which undergo decay in one of three ways: alpha, beta, or gamma decay. Depending on the rate of decay and the other factors, less than a dozen radioisotopes pose serious health risks.

Easily blocked from entering the human body, alpha emitting radioisotopes pose a health risk via inhalation or ingestion. Beta particles possess greater penetrating power, yet these can be blocked by thin layers of lead or other dense materials. It is gamma particles that pose the greatest health risk via exposure. The device Crawford and Freight sought—“a radiation emitting device that could be placed in the back of a van to covertly emit ionizing radiation strong enough to bring about radiation sickness or death against Crawford’s enemies,” required a radiological source emitting high-energy gamma rays.

States long ago foresaw radiological weapons as ineffective for battlefield use—easily obviated by many conventional and unconventional weapons. As early as 1943, notes Robert S. Norris in his 2002 book Racing for the Bomb, the “impending invasion of Europe precipitated fears and concerns about possible German use of radioactive materials on Allied forces.” U.S. scientists investigated the threat. They concluded, Norris writes, “that there would be many difficulties in devising munitions that would effectively deliver radioactive materials…” Still, Norris explained to this author on June 20, 2013, “Even in the early 1940s the fear of radioactivity was enough to move Allied planners to equip some D-Day soldiers with dosimeters.” Thankfully, Nazi Germany did not develop radiological weaponry and although serious consideration was given to their potential development (including the United States), no open-source data exists of any state having done so with the exception of one incident. The November 2006 death of Alexander Litvinenko, occurring three weeks after the former Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) officer drank tea containing polonium-210 (Po-210) in a London restaurant, was likely the work of Russian state operatives.

Non-state actors, in contrast, sometimes perceive harmful radioisotopes as an effective means towards achieving their goals. With regard to four possible perpetrator types, of the 19 recorded incidents, lone-actors account for ten. Four incidents are attributed to formal organizations and two to unaffiliated cells. Unknown perpetrator types account for three incidents.

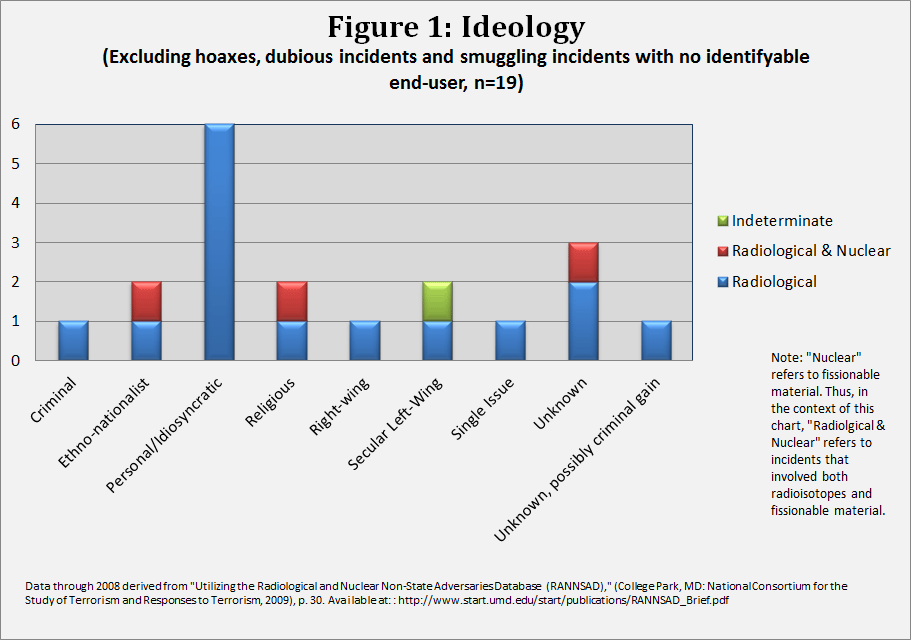

Figure 1 demonstrates the variety of general ideologies adhered to by the perpetrators. Note that the most active of all individuals and groups with “Religious” and “Personal / Idiosyncratic” ideologies were Sunni Islamists and U.S. right-wing extremist respectively.

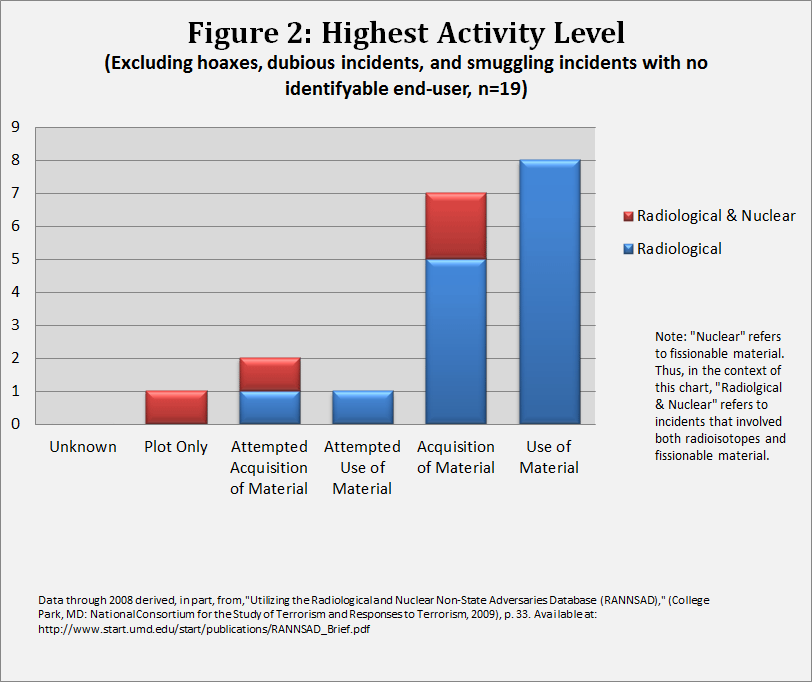

Figure 2 reveals how far along groups and individuals got on the spectrum of radiological activity. As noted in the UMD study, perpetrators successful in acquisition of radioisotopes more likely than not used the materials, although “success” came in only five of the incidents (assuming operational objectives that included generating casualties). The data set used to compile the previously mentioned UMD study—the Radiological and Nuclear Non-State Adversaries Database (RANNSAD)—when enlarged by this author’s subsequent research, reveals the following: four incidents that each resulted in one injury. A fifth incident, involving the use of iridium-192 (Ir-192) by a “nuclear medical researcher” in Guangzhou, China, sickened 75 individuals. When correctly excluding the death of Alexander Litvinenko, noted earlier as likely due to state actions, radiological incidents writ large have yet to yield a single fatality.

Some radioisotopes pose an extreme risk. One case of inadvertent dispersal—the 1988 Goiânia, Brazil, incident—killed four and negatively affected thousands. For well over a decade experts have warned of the likelihood of terrorist use of radioisotopes (almost half the expert respondents in a seminal 2005 survey “judged the risk of such an attack [occurring in the next ten years – i.e. by 2015] as 50 percent or greater”). Explaining non-use is akin to proving a negative—impossible. The latest incident, as farcical as elements of it may seem, should serve as a reminder that, despite a paucity of incidents and no fatalities, non-state actors continue to plot and actualize the nefarious use of radioisotopes.

Nukes in Europe: Secrecy Under Siege

By Hans M. Kristensen

The Cold War practice of NATO and the United States refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons anywhere is under attack in Europe. This week, two former Dutch prime ministers publicly confirmed the presence of nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands, one of six bases in NATO that still host US nuclear weapons.

The Cold War practice of NATO and the United States refusing to confirm or deny the presence of nuclear weapons anywhere is under attack in Europe. This week, two former Dutch prime ministers publicly confirmed the presence of nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base in the Netherlands, one of six bases in NATO that still host US nuclear weapons.

The first confirmation came in the program How Time Flies on the Dutch National Geographic channel where former prime minister Ruud Lubbers confirmed that there are nuclear weapons at Volkel Air Base. “I would never have thought those silly things would still be there in 2013,” Lubbers said, who was prime minister in 1982-1994. He even mentioned a specific number: 22 bombs.

The second confirmation Lubbers was joined yesterday by another former Dutch prime minister, Dries van Agt, who also confirmed that the weapons are there. “They are there and its crazy they still are,” said va Agt, who was prime minister in 1977-1982.

The second confirmation Lubbers was joined yesterday by another former Dutch prime minister, Dries van Agt, who also confirmed that the weapons are there. “They are there and its crazy they still are,” said va Agt, who was prime minister in 1977-1982.

As readers of this blog are aware (and anyone who have followed this issue over the years), it is not news that the US stores nuclear weapons at Volkel AB. But it is certainly news that two former Dutch prime ministers are now confirming it.

It is not a formal Dutch break with NATO nuclear secrecy norms but it is certainly a big crack in the dike that makes the Dutch government’s continued refusal to confirm or deny nuclear weapons at Volkel AB look rather, well, silly.

The instinct of the bureaucracy will be to ignore the statements to the extent possible and retreat into past policies of neither confirming nor denying the presence of nuclear weapons. But the new situation also presents an opportunity to break with the past and attempt to engage Russia about increasing the transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe.

Privileged Information

Information about US nuclear weapons at Volkel AB is privileged information that Lubbers and van Agt would have had access to on a highly confidential basis as prime ministers under the bilateral US-Dutch nuclear weapons storage agreement code named Toy Chest (no pun intended).

After leaving office, Lubbers and van Agt would have had to rely on other people with access to such information to be told. A nod would be sufficient to confirm the general presence of weapons, but the specific number would be harder to get. Why Lubbers says 22 is unclear; perhaps that’s the number he recalls from 1994.

Back then, the Clinton administration’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review decided to retain 480 nuclear bombs in Europe. How many of those were at Volkel AB is unknown, but when President Clinton six years later in December 2000 signed Presidential Decision Directive/NSC-74 that authorized continued deployment of 480 nuclear weapons in Europe, 20 of those were for Volkel AB.

Since then, the United States has unilaterally reduced the stockpile in Europe by nearly 60 percent from 480 to nearly 200 bombs today. Whether the number at Volkel AB has remained the same is unknown. The base has 11 underground storage vaults inside Protective Aircraft Shelters that can house a maximum of 44 bombs (see image). The 22 bombs that Lubbers mentions would imply each vault carries two bombs, but it is probably unlikely that there are more weapons in the Volkel vaults today than in 2000.

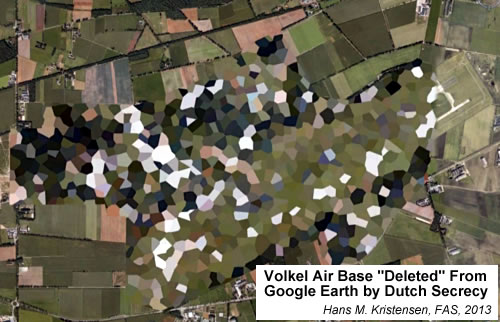

Silly Dutch Secrecy

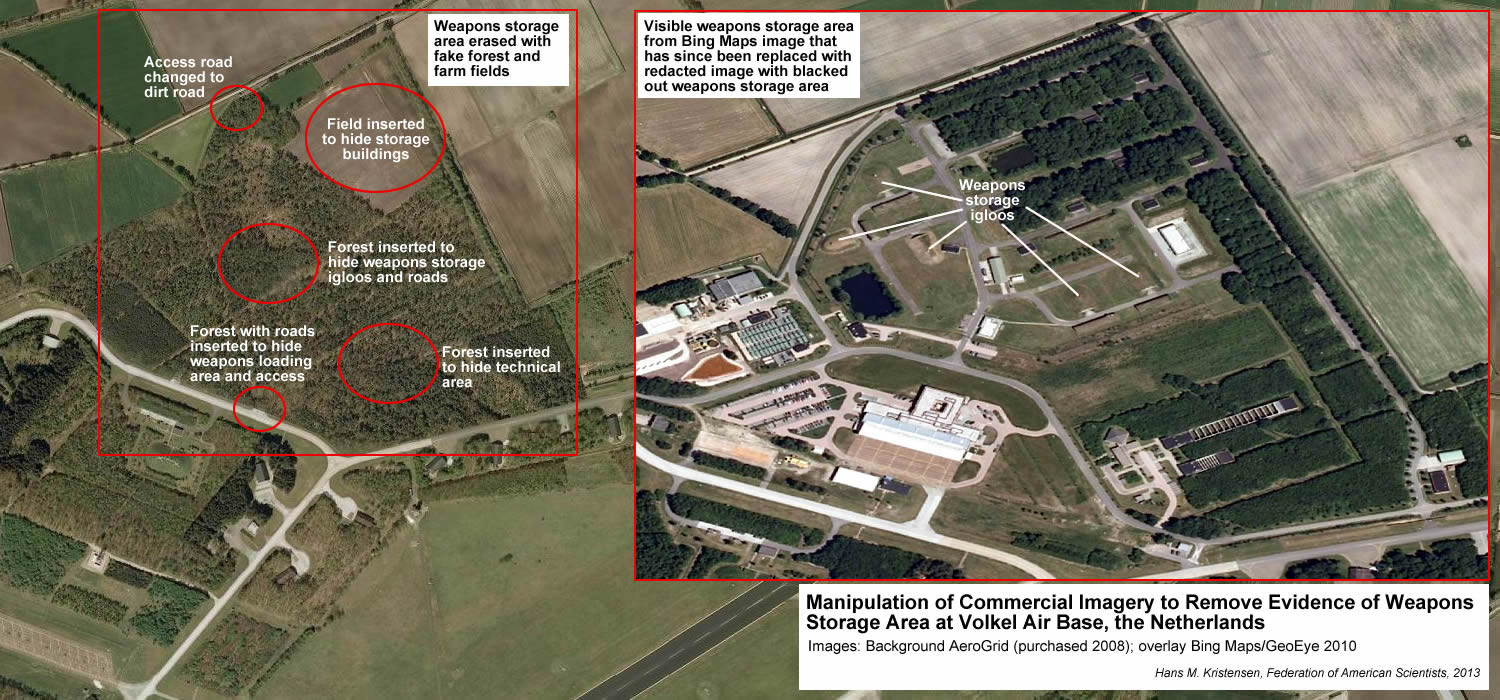

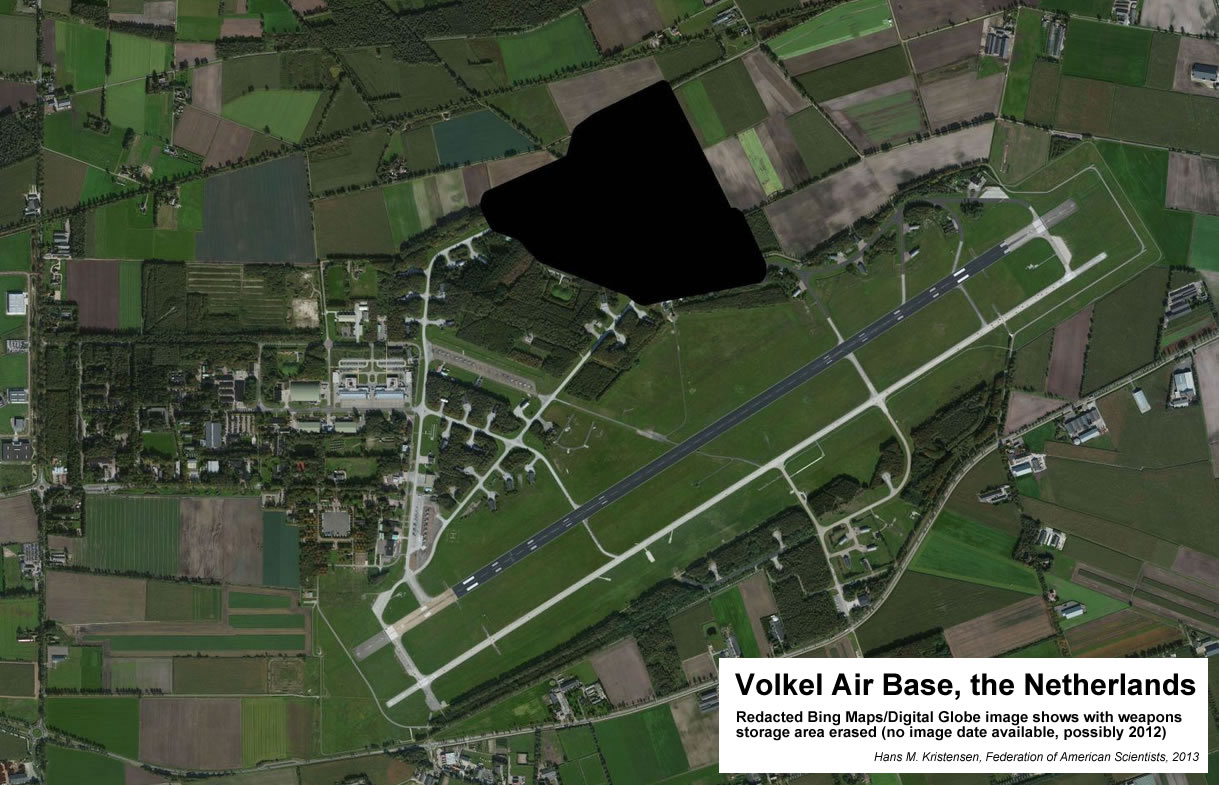

Getting basic information about the nuclear weapons at Volkel AB is not the only obstacle to nuclear transparency. Even aerial photos of the base are secret. For example, anyone who has tried to view Volkel AB on Google Earth will know that you can’t; the base has been completed pixel’ed out (see image below).

The reason is, the Dutch ministry of defense told me, that an old Dutch law requires that all military and royal (go figure!) facilities be obscured on aerial photos. And because the images covering the Netherlands on Google Earth are supplied by Aerodata International Surveys, a company partly based in Utrecht, the images are sanitized before handed over to Google Earth. It is a pity that a company such as Google lets itself be subjected to silly secrecy by accepting sanitized images on Google Earth.

The law is silly because all national-level adversaries (to Holland) have their own satellite imaging capabilities, so pixel’ing out Volkel AB won’t deny them any information. And anyone else can simply buy high-resolution satellite imagery on the Internet.

To test this point, I went to the web site of AeroGRID, a company partially owned by Aerodata (!). Armed only with a credit card, I was able to purchase a high-resolution image of Volkel Air Base that appeared to show the entire base (see image below).

Problem solved? Not quite. After a closer examination, I discovered that even this “clean” image had also been manipulated, even though AeroGRID never told me that the product I had paid for was actually a fake. Someone had very carefully erased a weapon storage area at the northern part of Volkel AB by overlaying it with trees and farm fields – even inserted forest roads that appear to meet up with dead-end access roads that would otherwise give away that the image had been altered.

Despite these efforts of silly secrecy, I was able to find the secret weapon storage area on another photo that was available on Bing Maps. That photo clearly showed the secret weapons storage area. By overlaying the area from the Bing Maps image onto the AeroGRID image, one can better see the extent of the image manipulation (see image below).

The secret weapons storage area is also visible on a Dutch military base map from 1999 that shows the layout of storage buildings and access roads. Comparison of the map with the Bing Maps image, however, also reveals that the weapons storage loading area has been upgraded significantly (see image below).

This un-redacted image is no longer available on Bing Map, however. Instead, on the new photo that is now available – yes, you guessed it – the weapons storage area has been deleted (see image below).

So why is the weapons storage area at Volkel AB secret? The facility was probably used to store the nuclear weapons until the underground vaults were added to the Protective Aircraft Shelters in 1991. But since then the weapons have been in the vaults. Perhaps they are sometimes serviced in the weapons storage area, or perhaps it’s simply a weapons storage area and therefore automatically considered secret. But now that we know that the weapons storage area is there and what it looks like, there is no need to manipulate the images anymore.

Implications and Conclusions

The confirmation by two former Dutch prime ministers that nuclear weapons are present at Volkel AB is an important contribution to increasing nuclear transparency in Europe. Although it doesn’t tell us something we don’t know, it challenges NATO’s long-standing, outdated, and counterproductive policy of keeping nuclear weapons locations secret. Germany has also confirmed that it hosts nuclear weapons.

Instead of trying to hush things up and continue the secrecy, the Dutch and German governments should together with NATO use the disclosures as an opportunity to reach out to Russia and propose a limited but reciprocal declaration of nuclear weapons storage at Volkel AB, Büchel AB in Germany, and one or two Russian bases. A declaration could be accompanied by verification of the absence of nuclear weapons from one or two bases in each country where nuclear weapons have been removed. Doing so could help jump-start the process of increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe, a goal NATO and the Dutch and German governments say they favor. Russia might be interested in exploring such an initiative.

Of course, such a transparency initiative will require the national leadership to twist the arms of the bureaucrats who will oppose any change. But incremental micromanagement of nuclear status quo in Europe will not move the ball forward; it requires political vision and leadership.

Continuing the nuclear secrecy no longer serves a beneficial purpose. The secrecy is not needed for safety or national security; those needs are taken care of by guards, guns, gates, and overall military and political postures. Instead, the secrecy fuels mistrust and rumors that lock NATO and Russia into old mindsets, postures, and relations. The secrecy is also used to chill a public debate that could otherwise result in a demand to withdraw the nuclear weapons from Europe.

One particularly controversial issue that faces the Dutch government and parliament in the next few years is that the B61 bombs at Volkel AB within the next decade are scheduled to be replaced with an improved nuclear bomb that is equipped with a new guidance tail kit that increases the weapon’s accuracy and gives it a standoff capability.

The combination of the new guided standoff B61-12 bomb and the stealthy F-35A Joint Strike Fighter – that the Dutch air force plans to get to replace the F-16 that currently has the nuclear strike mission – will significantly increase the nuclear capability at Volkel AB.

Why does the Dutch government believe it is necessary to begin deploying new guided standoff nuclear weapons at Volkel AB? How will that support the efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons in Europe? How will that help persuade Russia to reduce its non-strategic nuclear weapons?

It would be smart for the Dutch parliament to try to get answers to these questions from the government before the new nuclear bombs and stealth bombers start arriving at Volkel AB.

Background: Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons (FAS 2012) | US Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 2011 (BAS 2011) | US Nuclear Weapons in Europe (NRDC 2005)

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

SIPRI Yearbook 2013 Published

The Swedish International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) today published the 2013 issue of the SIPRI Yearbook. I’m coauthor of the chapter on worldwide nuclear weapons arsenals.

The yearbook is translated into Arabic, Chinese, Russian and Ukrainian, providing a unique source of nuclear weapons information to regions where such information is either not available or only to English-speaking readers.

In addition to the annual SIPRI Yearbook, bimonthly updates of individual nuclear weapon states are published as Nuclear Notebooks in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Moreover, an online table of world nuclear forces is provided on the FAS web site. The table is updated as new information becomes available.

Finally, occasional issue reports are published on the FAS Strategic Security Blog.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

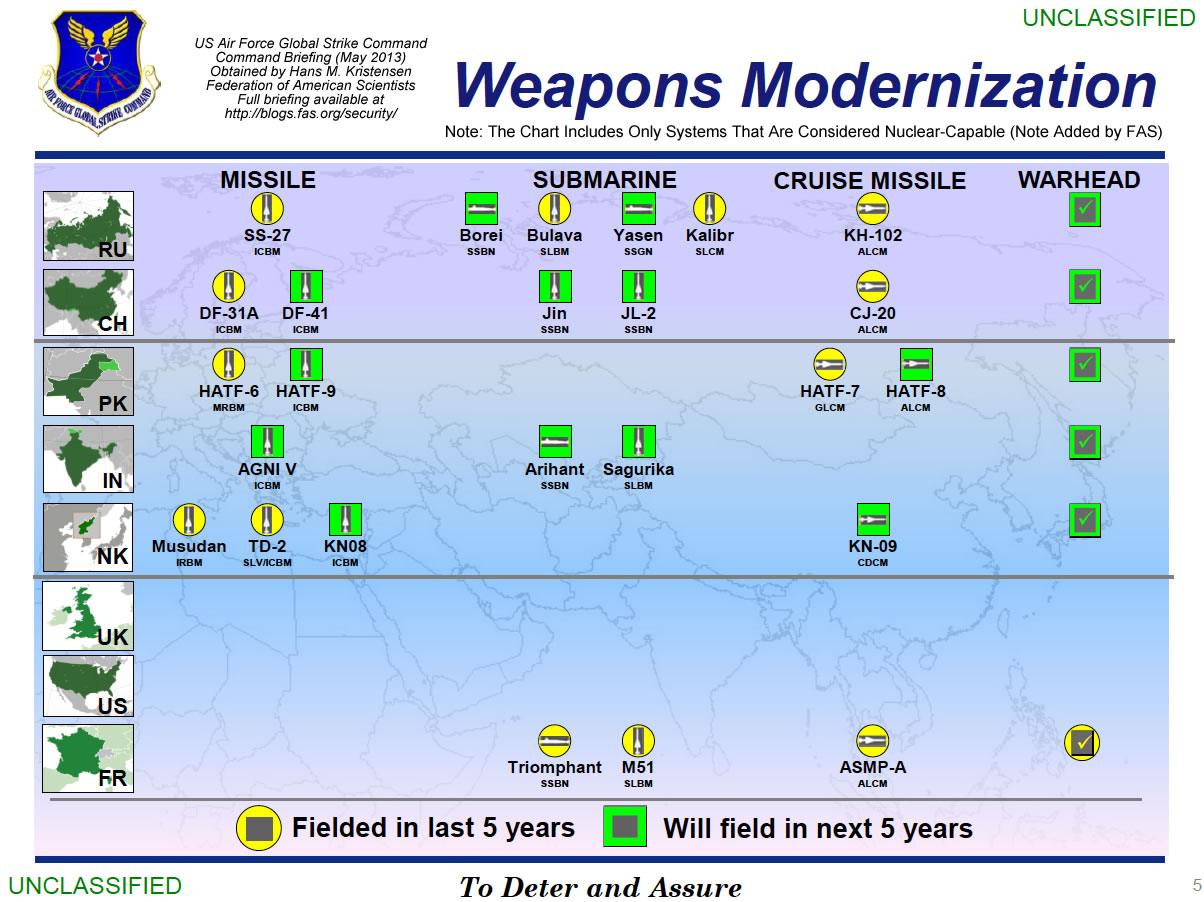

Air Force Briefing Shows Nuclear Modernizations But Ignores US and UK Programs

Click to view large version. Full briefing is here.

By Hans M. Kristensen

China and North Korea are developing nuclear-capable cruise missiles, according to U.S. Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC).

The new Chinese and North Korean systems appear on a slide in a Command Briefing that shows nuclear modernizations in eight of the world’s nine nuclear weapons states (Israel is not shown).

The Chinese missile is the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile for delivery by the H-6 bomber. The North Korean missile is the KN-09 coastal-defense cruise missile. These weapons would, if for real, be important additions to the nuclear arsenals in Asia.

At the same time, a closer look at the characterization used for nuclear modernizations in the various countries shows generalizations, inconsistencies and mistakes that raise questions about the quality of the intelligence used for the briefing.

Moreover, the omission from the slide of any U.S. and British modernizations is highly misleading and glosses over past, current, and planned modernizations in those countries.

For some, the briefing is a sales pitch to get Congress to fund new U.S. nuclear weapons.

Overall, however, the rampant nuclear modernizations shown on the slide underscore the urgent need for the international community to increase its pressure on the nuclear weapon states to curtail their nuclear programs. And it calls upon the Obama administration to reenergize its efforts to reduce the numbers and role of nuclear weapons.

Russia

![]()

The briefing lists seven Russian nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known and have been underway for many years. Fielded systems include SS-27 ICBM, Bulava SLBM, Kalibr SLCM, and KH-102 ALCM.

It is puzzling, however, that the briefing lists Bulava SLBM and Kalibr SLCM as fielded when their platforms (Borei SSBN and Yasen SSGN, respectively) are not. The first Borei SSBN officially entered service in January 2013.

Nuclear Cruise Missile For Yasen SSGN

It is the first time I’ve seen a U.S. government publication stating that the non-strategic Kalibr land-attack SLCM is nuclear (in public the Kalibr is sometimes called Caliber). The first Yasen SSGN, the Severodvinsk, test launched the Kalibr in November 2012. The weapon will also be deployed on the Akula-class SSGN. The Kalibr SLCM, which is dual-capable, will probably replace the aging SS-N-21, which is not. There are no other Russian non-strategic nuclear systems listed in the AFGSC briefing.

A new warhead is expected within the next five years, but since no new missile is listed the warhead must be for one of the existing weapons.

China

![]()

The briefing lists six Chinese nuclear modernizations: DF-31A ICBM, DF-41 ICBM, Jin SSBN, JL-2 SLBM, CJ-20 ALCM, and a new warhead.

The biggest surprise is the CJ-20 ALCM, which is the first time I have ever seen an official U.S. publication crediting a Chinese air-launched cruise missile with nuclear capability. The latest annual DOD report on Chinese military modernization does not do so.

H-6 with CJ-20. Credit: Chinese Internet.

The CJ-20 is thought to be an air-launched version of the 1,500+ kilometer ground-launched CJ-10 (DH-10), which the Air Force in 2009 reported as “conventional or nuclear” (the AFGSC briefing does not list the CJ-10). The CJ-20 apparently is being developed for delivery by a modified version of the H-6 medium-range bomber (H-6K and/or H-6M) with increased range. DOD asserts that the H-6 using the CJ-20 ALCM in a land-attack mission would be able to target facilities all over Asia and Russia (east of the Urals) as well as Guam – that is, if it can slip through air defenses.

The elusive DF-41 ICBM is mentioned by name as expected within the next five years. References to a missile known as DF-41 has been seen on and off for the past two decades, but disappeared when the DF-31A appeared instead. The latest DOD report does not mention the DF-41 but states that, “China may also be developing a new road-mobile ICBM, possibly capable of carrying a multiple independently targetable reentry vehicle (MIRV).” (Emphasis added).

AFGSC also predicts that China will field a new nuclear warhead within the next five years. MIRV would probably require a new and smaller warhead but it could potentially also refer to the payload for the JL-2.

Pakistan

![]()

Pakistan is listed with five nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known: Hatf-8 (Shaheen II) MRBM, Hatf-9 (NASR) SRBM, Hatf-7 (Babur) GLCM, Hatf-8 (Ra’ad) ALCM, and a new warhead. Two of them (Hatf-8 and Hatf-7) are listed as fielded.

The briefing mistakenly identifies the Hatf-9 as an ICBM instead of what it actually is: a short-range (60 km) ballistic missile.

The new warhead might be for the Hatf-9.

India

![]()

India is listed with four nuclear modernizations, all of which are well known: Agni V ICBM, Arihant SSBN, “Sagurika” SLBM, and a new warhead. The U.S. Intelligence Community normally refers to “Sagurika” as Sagarika, which is known as K-15 in India.

Neither the Agni III nor Agni IV are listed in the briefing, which might indicate, if correct, that the two systems, both of which were test launched in 2012, are in fact technology development programs intended to develop the technology to field the Agni V.

The U.S. Intelligence Community asserts that the Agni V will be capable of carrying multiple warheads, as recently stated by an India defense industry official – a dangerous development that could well motivate China to deploy multiple warheads on some of its missiles and trigger a new round of nuclear competition between India and China.

The new warhead might be for the SLBM and/or for Agni V.

North Korea

![]()

North Korea is listed with five nuclear modernizations: Musudan IRBM, TD-2 SLV/ICBM, KN-08 ICBM, KN-09 CDCM, and a warhead.

The biggest surprise is that AFGSC asserts that the KN-09 is nuclear-capable. There are few public reports about this weapon, but the South Korean television station MBC reported in April that it has a range of 100-120 km. MBC showed KN-09 as a ballistic missile, but AFGSC lists it as a CDCM (Coastal Defense Cruise Missile).

The Musudan IRBM is listed as “fielded” even though the missile, according to the U.S. Intelligence Community, has never been flight tested. In this case, “fielded” apparently means it has appeared but not that it is operational or necessarily deployed with the armed forces.

The Mushudan is listed as “fielded,” similar to the Russian SS-27, even though the North Korean missile has never been flight tested.

The KN-08 ICBM, which was displayed at the May 2012 parade, was widely seen by non-governmental analysts to be a mockup. But AFGSC obviously believes the weapon is real and expected to be “fielded” within the next five years. There were rumors in January 2013 that North Korea had started moving KN-08 launchers around the country at the beginning of a saber-rattling campaign that lasted through March.

Finally, the AFGSC briefing also predicts that North Korea will field a nuclear warhead within the next five year. Whether this refers to North Korea’s first weaponized warhead or newer types is unclear.

United Kingdom

![]()

The UK section does not include any weapons modernizations, which doesn’t quite capture what’s going on. For example, Britain is deploying the modified W76-1/Mk4A, which British officials have stated will increase the targeting capability of the Trident II D5 SLBM. Accordingly, a warhead icon has been added to the U.K. bar above.

Moreover, although the final approval has not been given yet, Britain is planning construction of a new SSBN to replace the current fleet of four Vanguard-class SSBNs. The missile section is under development in the United States. The new submarine will also receive the life-extended D5 SLBM.

United States

![]()

The U.S. section also does not show any nuclear modernizations, which glosses over important upgrades.

For example, the Minuteman III ICBM is in the final phases of a decade-long multi-billion dollar life-extension program that will extend the weapon to 2030. Privately, Air Force officials are joking that everything except the shell is new. Accordingly, a fielded ICBM icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

Moreover, full-scale production and deployment of the W76-1/Mk4A warhead on the Trident II D5 SLBM is underway. The combination of the new reentry body with the D5 increases the targeting capability of the weapon. Accordingly, a fielded warhead icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

In addition, from 2017 the U.S. Navy will begin deploying a modified life-extended version of the D5 SLBM (D5LE) on Ohio-class SSBNs. Production of the D5LE is currently underway, which will be “more accurate” and “provide flexibility to support new missions,” according to the navy and contractor. Accordingly, a forthcoming SLBM icon has been added to the U.S. bar.

Finally, the United States has begun design of a new SSBN class, a long-range bomber, a long-range cruise missile, a fighter-bomber, a guided standoff gravity bomb, and is studying a replacement-ICBM.

Hardly the dormant nuclear enterprise portrayed in the briefing.

France

![]()

France is listed with four nuclear modernizations, all well known: Triomphant SSBN, M51 SLBM, ASMP-A ALCM, and a new warhead.

The introduction of the ASMP-A is complete but the M51 SLBM is still replacing M45 SLBMs on the SSBN fleet.

The warhead section only appears to include the TNA warhead for the ASMP-A but ignores that France from 2015 will begin replacing the TN75 warhead on the M51 SLBM with the new TNO.

What is Meant by Nuclear and Fielded?

The AFGSC briefing is unclear and somewhat confusing about what constitutes a nuclear-capable weapon system and when it is considered “fielded.”

AFGSC confirmed to me that the slide only lists nuclear-capable weapon systems.

Air Force regulations are pretty specific about what constitutes a nuclear-capable unit. According to Air Force Instruction 13-503 regarding the Nuclear-Capable Unit Certification, Decertification and Restriction Program, a nuclear-capable unit is “a unit or an activity assigned responsibilities for employing, assembling, maintaining, transporting or storing war reserve (WR) nuclear weapons, their associated components and ancillary equipment.”

This is pretty straightforward when it comes to Russian weapons but much more dubious when describing North Korean systems. Russia is known to have developed miniaturized warheads and repeatedly test-flown them on missiles that are operationally deployed with the armed forces.

North Korea is a different matter. It is known to have detonated three nuclear test devices and test-launched some missiles, but that’s pretty much the extent of it. Despite its efforts and some worrisome progress, there is no public evidence that it has yet turned the nuclear devices into miniaturized warheads that are capable of being employed successfully by its ballistic or cruise missiles. Nor is there any public evidence that nuclear-armed missiles are operationally deployed with the armed forces.

Moreover, the U.S. Intelligence Community has recently issued strong statements that cast doubt on whether North Korea has yet mastered the technology to equip missile with nuclear warheads. James Clapper, the director of National Intelligence, testified before the Senate on April 18, 2013, that despite its efforts, “North Korea has not, however, fully developed, tested, or demonstrated the full range of capabilities necessary for a nuclear-armed missile.”

So how can the AFGSC briefing label North Korean ballistic missiles as nuclear-capable – and also conclude that the KN-09 cruise missile is nuclear-capable?

There are similar questions about the determination of when a weapon system is “fielded.” Does it mean it is fielded with the armed forces or simply that it has been seen? For example, how can a North Korean Musudan IRBM be considered fielded similarly to a Russia SS-27 ICBM?

Or how can the Musudan IRBM be identified as already “fielded” when it has not been flight tested and only displayed on parade, when the KN-08 is identified as not “fielded” even though it has also not been flight tested, also been displayed on parade, and even moved around North Korea?