The Fallacy of Proven and Adaptable Defenses

It is currently U.S. policy to deploy missile defenses that are “proven, cost-effective, and adaptable.” As outlined in the 2010 Ballistic Missile Defense Review, proven means “extensive testing and assessment,” or “fly before you buy.” Adaptive means that defenses can respond to unexpected threats by being rapidly relocated or “surged to a region,” and by being easily integrated into existing defensive architectures.

While “extensive testing” in the field is an important step towards proven defenses, this article argues that it is insufficient for truly proven—that is, trustworthy—defenses. Defenses against nuclear weapons face a very high burden of proof because a single bomb is utterly devastating. But even if defenses achieve this level of trustworthiness in one context, this article argues that they cannot immediately be trusted when they are adapted to another context. Calls for proven and adaptive defenses thus promote a dangerous fallacy: that defenses which are proven in one context remain proven when they are adapted to another.

To explain why defenses should not be regarded as both proven and adaptable, this article begins by outlining a little-noted yet critical challenge for missile defense: developing, integrating, and maintaining its complex and continually-evolving software. A second section uses experience with missile defense to illustrate three key reasons that software which is proven on testing ranges does not remain proven when it is adapted to the battlefield. A third section outlines some of the challenges associated with rapidly adapting missile defense software to new threat environments. The article concludes that while missile defenses may offer some insurance against an attack, they also come with new risks.

Missile defense as an information problem

Missile defense is a race against time. Intercontinental ballistic missiles travel around the globe in just thirty minutes, while intermediate, medium, and short range ballistic missiles take even less time to reach their targets. While defenders would ideally like to intercept missiles in the 3-5 minutes that they launch out of the earth’s atmosphere (boost phase), geographic and physical constraints have rendered this option impractical for the foreseeable future. The defense has the most time to “kill” a missile during mid-course (as it travels through space), but here a warhead can be disguised by decoys and chaff, making it difficult to find and destroy. As missiles (or warheads) re-enter the earth’s atmosphere, any decoys are slowed down, and the warhead becomes easier to track. But, this terminal phase of flight leaves only a few minutes for the defender to act.

These time constraints make missile defense not only a physical problem, but also an informational problem. While most missile defense publicity focuses on the image of a bullet hitting a bullet in the sky, each interception relies critically on a much less visible information system which gathers radar or sensor data about the locations and speeds of targets, and guides defensive weapons to those targets. Faster computers can speed along information processing, but do not ensure that information is processed and interpreted correctly. The challenge of accurately detecting targets, discriminating targets from decoys or chaff, guiding defensive weapons to targets, and coordinating complementary missile defense systems, all falls to a very complex software system.

Today’s missile defense systems must manage tremendous informational complexity—a wide range of threats, emerging from different regions, in uncertain and changing ways. Informational complexity stems not only from the diverse threats that defenses aim to counter, but also from the fact that achieving highly effective defenses requires layering multiple defensive systems over large geographic regions; this in turn requires international cooperation. For example, to defend the United States from attack by Iran, the ground-based midcourse defense (GMD) relies not only on radars and missiles in Alaska and California but also on radars and missiles stationed in Europe. Effective defenses require computers and software to “fuse” data from different regions and systems controlled by other nations into a seamless picture of the battle space. Missile defense software requirements constantly evolve with changing threats, domestic politics, and international relations.

Such complex and forever-evolving requirements will limit any engineer. But software engineers such as Fred Brooks have come to recognize the complexity associated with unpredictable and changing human institutions as their “essential” challenge. Brooks juxtaposes the complexity of physics with the “arbitrary complexity” of software. Whereas the complexity of nature is presumed to be governed by universal laws, the arbitrary complexity of software is “forced without rhyme or reason by the many human institutions and systems to which [software] interfaces must conform.”

In other words, the design of software is not driven by predictive and deterministic natural laws, but by the arbitrary requirements of whatever hardware and social organizations it serves. Because arbitrary complexity is the essence of software, it will always be difficult to develop correctly. Despite tremendous technological progress, software engineers have agreed that arbitrary complexity imposes fundamental constraints on our ability to engineer reliable software systems.

In the case of missile defense, software must integrate disparate pieces of equipment (such as missile interceptors, radars, satellites, and command consoles) with the procedures of various countries (such as U.S., European, Japanese, and South Korean missile defense commands). Software can only meet the ad hoc requirements of physical hardware and social organizations by becoming arbitrarily complex.

Software engineers manage the arbitrary complexity of software through modular design, skillful project management, and a variety of automated tools that help to prevent common errors. Nonetheless, as the arbitrary complexity of software grows, so too do unexpected interactions and errors. The only way to make software reliable is to use it operationally and correct the errors that emerge in real-world use. If the operating conditions change only slightly, new and unexpected errors may emerge. Decades of experience have shown that it is impossible to develop trustworthy software of any practical scale without operational testing and debugging.

In some contexts, glitches are not catastrophic. For example, in 2007 six F-22 Raptors flew from Hawaii to Japan for the first time, and as they crossed the International Date Line their computers crashed. Repeated efforts to reboot failed and the pilots were left without navigation computers, information about fuel, and much of their communications. Fortunately, weather was clear so they could follow refueling tankers back to Hawaii and land safely. The software glitch was fixed within 48 hours.

Had the weather been bad or had the Raptors been in combat, the error would have had much more serious consequences. In such situations, time becomes much more critical. Similarly, a missile defense system must operate properly within the first few minutes that it is needed; there is no time for software updates.

What has been proven? The difference between field tests and combat experience

Because a small change in operating conditions can cause unexpected interactions in software, missile defenses can only be proven through real-world combat experience. Yet those who describe defenses as “proven” are typically referring to results obtained on a testing range. The phased adaptive approach’s emphasis on “proven” refers to its focus on the SM-3 missile, which has tested better than the ground-based midcourse defense (GMD). The SM-3 Block 1 system is based on technology in the Navy’s Aegis air and missile defense system, and it has succeeded in 19 of 23 intercept attempts (nearly 83 percent), whereas the GMD has succeeded in only half (8 of 16) intercept attempts. Similarly, when Army officers and project managers call the theater high altitude area defense (THAAD) proven, they are referring to results on a test range. THAAD, a late midcourse and early terminal phase defense, has intercepted eleven out of eleven test targets since 2005.

While tests are extremely important, they do not prove that missile defenses will be reliable in battle. Experience reveals at least three ways in which differences between real-world operating conditions and the testing range may cause missile defense software to fail.

First, missile defense software and test programs make assumptions about the behavior of its targets which may not be realistic. The qualities of test targets are carefully controlled—between 2002 and 2008, over 11 percent of missile defense tests were aborted because the target failed to behave as expected.

But real targets can also behave unexpectedly. For example, in the 1991 Gulf War, short range Scud missiles launched by Iraq broke up as they reentered the atmosphere, causing them to corkscrew rather than follow a predictable ballistic trajectory. This unpredictable behavior is a major reason that the Patriot (PAC-2) missile defense missed at least 28 out of 29 intercept attempts.Although the Patriot had successfully intercepted six targets on a test range, the unpredictability of real-world targets thwarted its success in combat.

Second, missile defense tests are conducted under very different time pressures than those of real-world battle. Missile defense tests do not require operators to remain watchful over an extended period of days or weeks, until the precise one or two minutes in which a missile is fired. Instead crews are given a “window of interest,” typically spanning several hours, in which to look for an attack. Defenders of such tests argue that information about the window of attack is necessary (to avoid conflicts with normal air and sea traffic), and realistic (presumably because defenses will only be used during a limited period of conflict).

Yet in real-world combat, the “window of interest” may last much longer than a few hours. For example, the Patriot was originally designed with the assumption that it would only be needed for a few hours at a time, but when it was sent to Israel and Saudi Arabia in the first Gulf War, it was suddenly operational for days at a time. In these conditions, the Patriot’s control software began to accrue a timing error which had never shown up when the computer was rebooted every few hours. On February 25, 1991, this software-controlled timing error caused the Patriot to miss a Scud missile, which struck an Army barracks at Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, killing 28 Americans. The fix that might have helped the Patriot defuse the Dhahran attack arrived one day too late.

A third difference between test ranges and real-world combat is that air traffic is often present in and around combat zones, creating opportunities for friendly fire; the likelihood of friendly fire is increased by the stressful conditions of combat.For example, in the first Gulf War, the Patriot fired two interceptors at U.S. fighter jets (fortunately the fighters evaded the attack).When a more advanced version of the Patriot (PAC-3) was sent to Iraq in 2003, friendly fire caused more casualties. On March 23, 2003, a Patriot battery stationed near the Kuwait border shot down a British Tornado fighter jet, killing both crew members. Just two days later, operators in another battery locked on to a target and prepared to fire, discovering that it was an American F-16 only after the fighter fired back (fortunately only a radar was destroyed). Several days later, another Patriot battery shot down an American Navy Hornet fighter, killing its pilot.

A Defense Science Board task force eventually attributed the failure to several software-related problems. The Patriot’s Identify Friend or Foe (IFF) algorithms (which ought to have clearly distinguished allies from enemies) performed poorly. Command and control systems did not give crews good situational awareness, leaving them completely dependent on the faulty IFF technologies. The Patriot’s protocols, displays, and software made operations “largely automatic,” while “operators were trained to trust the software.” Unfortunately this trust was not warranted.

These three features—less predictable targets, longer “windows of interest,” and the presence of air traffic—are unique to combat, and are among the reasons that software which is proven on a test range may not be reliable in battle. Other differences concern the defensive technology itself—missile seekers are often hand-assembled, and quality is not always assured from one missile to the next. Missile defense aims to overcome such challenges in quality assurance by “layering” defensive systems (i.e. if one system fails to hit a missile, another one might make the kill). But unexpected interactions between missile defense layers could also cause failures. Indeed, some tests which produced “successful” interceptions by individual missile defense systems also revealed limitations in integrating different defensive systems. Layered defenses, like most individual defensive systems, have yet to be proven reliable in real-world battle.

The Fallacy of “Proven” and “Adaptive” Defenses

As this brief review suggests, field testing takes place in a significantly different operational environment than that of combat, and the difference matters. Missile defenses that were “proven” in field testing have repeatedly failed when they were adapted to combat environments, either missing missiles completely, or shooting down friendly aircraft. Thus, talk of “proven” and “adaptable” defense furthers a dangerous fallacy—that defensive systems that are proven in one context remain proven as they are adapted to new threats.

Defensive deployments do not simply “plug-and-play” as they are deployed to new operational environments around the world because they must be carefully integrated with other weapons systems. For example, to achieve “layered” defenses of the United States, computers must “fuse” data from geographically dispersed sensors and radars and provide commands in different regions with a seamless picture of the battle space. In the first U.S. missile defense test that attempted to integrate elements such as Aegis and THAAD, systems successfully intercepted targets, but also revealed failures in the interoperability of different computer and communications systems. In the European theater, these systems confront the additional challenge of being integrated with NATO’s separate Active Layered Theater Ballistic Missile Defence (ALTBMD).

Similar challenges exist in the Asia-Pacific region, where U.S. allies have purchased systems such as Patriot and Aegis. It is not yet clear how such elements should interoperate with U.S. forces in the region. The United States and Japan have effectively formed a joint command relationship, with both nations feeding information from their sensors into a common control room. However, command relationships with other countries in the Asian Pacific region such as South Korea and Taiwan remain unclear.

The challenge of systems integration was a recurring theme at the May 2014 Atlantic Council’s missile defense conference. Attendees noted that U.S. allies such as Japan and South Korea mistrust one another, creating difficulties for integrating computerized command and control systems. They also pointed to U.S. export control laws that create difficulties by restricting the flow of computer and networking technologies to many parts of the world.Atlantic Council senior fellow Bilal Saab noted that the “problem with hardware is it doesn’t operate in a political vacuum.”

Neither does software. All of these constraints—export control laws, mistrust between nations, different computer systems—produce arbitrarily complex requirements for the software, which must integrate data from disparate missile defense elements into a unified picture of the battle space. Interoperability that is proven at one time does not remain proven as it is adapted to new technological and strategic environments.

Risky Insurance

Although defenses cannot be simultaneously proven and adaptive, it may still make sense to deploy defenses. Missile defenses that have undergone robust field testing may provide some measure of insurance against attack. Additionally, cooperative defenses may provide a means of reducing reliance on massive nuclear arsenals—although efforts to share NATO or U.S. missile defenses with Russia are currently stalled.

But whatever insurance missile defense offers, it also comes with new risks due to its reliance on tremendously complex software. Other analyses of missile defense have pointed to risks associated with strategic instability, and noted that defenses appear to be limiting rather than facilitating reductions of offensive nuclear arsenals. An appreciation for the difficulty of developing, integrating, and maintaining complex missile defense software calls attention to a slightly different set of risks.

The risks of friendly fire are evident from experience with the Patriot. More fundamentally, the inability of complex software to fully anticipate target behavior limits its reliability in battle, as seen in the first Gulf War. The PAC-3 system appears to have performed better in the second Gulf War; according to the Army, the defenses incapacitated nine out of nine missiles headed towards a defended asset. Thus, the PAC-3 system may be regarded as truly proven against a particular set of targets. But however well defenses perform against one set of targets, we cannot be assured that they will perform equally well against a new set of targets.

Additionally, defenses must be exceedingly reliable to defend against nuclear-armed missiles. In World War II, a 10 percent success rate was sufficient for air defenses to deter bombers, but the destructive power of nuclear weapons calls for a much higher success rate. If even one nuclear weapon gets by a defensive system, it can destroy a major city and its surroundings.

The greatest risk of all comes not with defenses themselves, but with overconfidence in their capabilities. In 2002, faith in military technology prompted then Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld to overrule seasoned military planners, insisting that high technology reduced the number of ground troops that were necessary in Iraq. As we now know, this confidence was tragically misplaced.

The decision to rely upon a missile defense deployment should thus weigh the risks of a missile attack against the risks of friendly fire and of unreliable defenses. While the fly-before-you-buy approach is an essential step towards trustworthy defenses, field testing does not yield truly proven, or trustworthy, defenses. However proven a defensive system becomes in one battle context, it does not remain proven when it is adapted to another. Ultimately, the notion of proven and adaptive defenses is a contradiction in terms.

White House Office of the Press Secretary, “Fact Sheet on U.S. Missile Defense Policy,” September 17, 2009. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/FACT-SHEET-US-Missile-Defense-Policy-A-Phased-Adaptive-Approach-for-Missile-Defense-in-Europe/

Department of Defense, “Ballistic Missile Defense Review,” (January 2010): vi, 11. http://www.defense.gov/bmdr/docs/BMDR%20as%20of%2026JAN10%200630_for%20web.pdf

See National Research Council, Making Sense of Ballistic Missile Defense: An Assessment of Concepts and Systems for U.S. Boost-Phase Missile Defense in Comparison to Other Alternatives (Washington D.C.: National Academies Press, 2012). “Report of the American Physical Society Study Group on Boost Phase Intercept Systems for National Missile Defense,” July 2003. http://www.aps.org/policy/reports/studies/upload/boostphase-intercept.PDF

Frederick Brooks, “No Silver Bullet: Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering,” IEEE Computer (Addison-Wesley Professional, 1987), http://www-inst.eecs.berkeley.edu/~maratb/readings/NoSilverBullet.html.

When software engineers gathered for the twenty-year anniversary of Brooks’ article, they all agreed that his original argument had been proven correct despite impressive technological advances. See Frederick Brooks et al., “Panel: ‘No Silver Bullet’ Reloaded,” in 22nd Annual ACM SIGPLAN Conference on Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages, and Applications (OOPSLA), ed. Richard Gabriel et al. (Montreal, Canada: ACM, 2007).

For a summary of such techniques, and reasons that they are not sufficient to produce reliable software, see David Parnas, “Software Aspects of Strategic Defense Systems,” Communications of the ACM 28, no. 12 (1985): 1326.

“F-22 Squadron Shot Down by the International Date Line,” Defense Industry Daily, March 1 2007. http://www.defenseindustrydaily.com/f22-squadron-shot-down-by-the-international-date-line-03087/ Accessed June 15, 2014.

See for example, White House “Fact Sheet on U.S. Missile Defense Policy,” September 17, 2009 http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/FACT-SHEET-US-Missile-Defense-Policy-A-Phased-Adaptive-Approach-for-Missile-Defense-in-Europe

For results on the SM3 Block 1, see Missile Defense Agency, “Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense testing record,” http://www.mda.mil/global/documents/pdf/aegis_tests.pdf October 2013. On the GMD, see Missile Defense Agency, “Ballistic Missile Defense Intercept Flight Test record,” last updated October 4, 2013 http://www.mda.mil/news/fact_sheets.html

See for example, comments in “THAAD Soldiers take part in historic training exercise,” Fort Bliss Bugle, http://fortblissbugle.com/thaad-soldiers-take-part-in-historic-training-exercise/ ; BAE, “Bae Systems’ Seeker Performs Successfully In Historic Integrated Live Fire Missile Defense Test,” Press release, 7 February 2013, http://www.baesystems.com/article/BAES_156395/bae-systems-seeker-performs-successfully-in-historic-integrated-live-fire-missile-defense-test . Both accessed June 15, 2014.

Missile Defense Agency, “Ballistic Missile Defense Intercept Flight Test record,” last updated October 4, 2013 http://www.mda.mil/news/fact_sheets.html

This is based upon reports that 3 of 42 launches experienced target failures or anomalies between 2002-2005, and 6 of 38 launches experienced such failures from 2006-2007. See U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Sound Business Case Needed to Implement Missile Defense Agency’s Targets,” September 2008 http://www.gao.gov/assets/290/281962.pdf

George N. Lewis and Theodore A. Postol, “Video Evidence on the Effectiveness of Patriot During the 1991 Gulf War,” Science & Global Security 4 (1993).

Ibid; see also George N. Lewis and Theodore A. Postol, “Technical Debate over Patriot Performance in the Gulf War,” Science & Global Security 3 (2000). In fact, though Iraqis launched fewer Scuds after the Army deployed Patriot, evidence suggested that damage in Israel increased—suggesting that Patriot itself caused some damage. See George N. Lewis and Theodore A. Postol, “An Evaluation of the Army Report “Analysis of Video Tapes to Assess Patriot Effectiveness” Dated 31 March 1992,” (Cambridge MA: Defense and Arms Control Studies Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1992). Available online at /spp/starwars/docops/pl920908.htm

On the Patriot’s performance on the testing range before deployment, see “Performance of the Patriot Missile in the Gulf War,” Hearings before the Committee on Government Operations, 102nd Congress, 2nd sess., April 7, 1992.

Lt. Gen. Henry A. Obering III (ret.) and Rebeccah Heinrichs, “In Defense of U.S. Missile Defense,” Letter to the International Herald Tribune, September 27, 2011 http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/28/opinion/28iht-edlet28.html?_r=2&

The Patriot was only designed to operate for 24 hours at a time before rebooting, and hence the timing problem did not matter in previous operating conditions. Technically this would be described as a “requirements failure.” GAO, “Patriot Missile Defense: Software Problem Led to System Failure at Dhahan, Saudi Arabia,” (Washington, D.C.: General Accounting Office, 1992).

GAO, “Patriot Missile Defense: Software Problem Led to System Failure at Dhahan, Saudi Arabia.”

These stresses were one contributing factor to the downing of Iran Air flight 655 by the Vincennes in 1988; for a closer analysis, see Gene Rochlin, Trapped in the Net: The Unanticipated Consequences of Computerization (Princeton: Princeton U, 1998).

Clifford Johnson, “Patriots,” posted in the RISKS forum, 29 January 1991 http://www.catless.com/Risks/10.83.html#subj4

Jonathan Weisman, “Patriot Missiles Seemingly Falter for Second Time; Glitch in Software Suspected,” Washington Post, March 26 2003.

Bradley Graham, “Radar Probed in Patriot Incidents,” Washington Post, May 8, 2003.

Michael Williams and William Delaney, “Report of the Defense Science Board Task Force on Patriot System Performance,” (Washington, D.C.: Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics, 2005).

Quality assurance has been a significant problem, for example, in the GMD. See David Willman, “$40 Billion Missile Defense System Proves Unreliable,” LA Times, June 15, 2014. http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-missile-defense-20140615-story.html#page=1 The “tacit knowledge” required to fabricate missile guidance technology has historically been a source of significant concern; see Donald MacKenzie, Inventing Accuracy: A Historical Sociology of Ballistic Missile Guidance (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990).

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Missile Defense: Mixed Progress in Achieving Acquisition Goals and Improving Accountability,” April 2014, p 16-17.

The GAO has warned that the U.S. approach to European defenses, by developing these eclectic systems concurrently, is increasing the risks that the system “will not meet the warfighter’s needs, with significant potential cost and schedule growth consequences.” GAO, “Missile Defense: European Phased Adaptive Approach Acquisitions Face Synchronization, Transparency, and Accountability Challenges,” (Washington, D.C.: GAO, 2010), 3. For more on the NATO Active Layered Theater Ballistic Missile Defence (ALTBMD), and efforts to coordinate its command and control systems with those of individual member nations, see http://www.nato.int/nato_static/assets/pdf/pdf_2011_07/20110727_110727-MediaFactSheet-ALTBMD.pdf

Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Trust, Not Tech, Big Problem Building Missile Defenses Vs. Iran, North Korea,”Ian E. Rinehart, Steven A. Hildreth, Susan V. Lawrence, Congressional Research Service Report, “Ballistic Missile Defense in the Asia-Pacific Region: Cooperation and Opposition,” June 24 2013. /sgp/crs/nuke/R43116.pdf

Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “Trust, Not Tech, Big Problem Building Missile Defenses Vs. Iran, North Korea,” BreakingDefense.com, May 29, 2014, http://breakingdefense.com/2014/05/trust-not-tech-big-problem-building-missile-defenses-vs-iran-north-korea/

http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/events/past-events/missile-defense-in-the-asia-pacific

James E Goodby and Sidney D Drell, “Rethinking Nuclear Deterrence” (paper presented at the conference Reykjavik Revisited: Steps Towards a World Free of Nuclear Weapons, Stanford, CA, 2007).

For a discussion of both issues, and references for further reading, see Rebecca Slayton, Arguments That Count: Physics, Computing, and Missile Defense, 1949-2012, Inside Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013).

Historically, the complexity of missile defense software has also made it prone to schedule delays and cost overruns.

Kadish testimony, Subcommittee on Defense, Committee on Appropriations, Department of Defense Appropriations, May 1 2003.

Thom Shanker and Eric Schmitt, “Rumsfeld Orders War Plans Redone for Faster Action,” New York Times, 2002.

Rebecca Slayton is an Assistant Professor in Science & Technology Studies at the Judith Reppy Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies at Cornell University. Her research examines how experts assess different kinds of risks in new technology, and how their arguments gain influence in distinctive organizational and political contexts. She is author of Arguments that Count: Physics, Computing, and Missile Defense, 1949-2012 (MIT Press: 2013), which compares how two different ways of framing complex technology—physics and computer science—lead to very different understandings of the risks associated with weapons systems. It also shows how computer scientists established a disciplinary repertoire—quantitative rules, codified knowledge, and other tools for assessment—that enabled them to construct authoritative arguments about complex software, and to make those analyses “stick” in the political process.

Slayton earned a Ph.D. in physical chemistry at Harvard University in 2002, and completed postdoctoral training in the Science, Technology, and Society Program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She has also held research fellowships from the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University. She is currently studying efforts to manage the diverse risks—economic, environmental, and security—associated with a “smarter” electrical grid.

Manufacturing Nuclear Weapon Pits, and More from CRS

A critical assessment of the feasibility of reaching the Department of Defense’s goal of producing 80 plutonium pits (or triggers) for nuclear weapons was prepared by the Congressional Research Service. It provides new analysis of the space and material requirements needed to achieve the declared goal. See Manufacturing Nuclear Weapon “Pits”: A Decisionmaking Approach for Congress, August 15, 2014.

Other new or updated CRS reports obtained by Secrecy News include the following.

The U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa and the Futenma Base Controversy, August 14, 2014

India’s New Government and Implications for U.S. Interests, August 7, 2014

Guatemala: Political, Security, and Socio-Economic Conditions and U.S. Relations, updated August 7, 2014

Small Refineries and Oil Field Processors: Opportunities and Challenges, August 11, 2014

Telemarketing Regulation: National and State Do Not Call Registries, August 14, 2014

Immigration Policies and Issues on Health-Related Grounds for Exclusion, updated August 13, 2014

Russia Declared In Violation Of INF Treaty: New Cruise Missile May Be Deploying

A Russian GLCM is launched from an Iskander-K launcher at Kapustin Yar in 2007.

The United States yesterday publicly accused Russia of violating the landmark 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty.

The accusation was made in the State Department’s 2014 Compliance Report, which states:

“The United States has determined that the Russian Federation is in violation of its obligations under the INF Treaty not to possess, produce, or flight-test a ground-launched cruise missile (GLCM) with a range capability of 500 km to 5,500 km, or to possess or produce launchers of such missiles.”

The Russian violation of the INF is, if true, a very serious matter and Russia must immediately restore its compliance with the Treaty in a transparent and verifiable manner.

Rumors about a violation have swirled around Washington (and elsewhere) for a long time. Apparently, the GLCM was first launched in 2007 (see image to the left), so why the long wait?

The official accusation it is likely to stir up calls for the United States to abandon the INF Treaty and other arms control efforts. Doing so would be a serious mistake that would undercut benefits from existing and possible future agreements. Instead the United States should continue to adhere to the treaty, work with the international community to restore Russian compliance, and pursue additional measures to reduce nuclear dangers worldwide.

What Violation?

The unclassified Compliance Report doesn’t specify the Russian weapon system that it concludes constitutes a violation of the INF Treaty. Nor does it specify when the violation occurred. The classified version and the briefings that the Obama administration has given Congress and European allies presumably are more detailed. All the Compliance Report says is that the violation concerns a GLCM with a range of 310 miles to 3,400 miles (500 km to 5,500 km).

While public official identification is still pending, news media reports and other information indicate that the violation possibly concerns the Iskander-K weapon system, a modification of the Iskander launcher designed to carry two cruise missiles instead of two SS-26 Iskander-M ballistic missiles.

[UPDATE December 2014: US Undersecretary of State Rose Gottemoeller helpfully removes some of the uncertainty: “It is a ground-launched cruise missile. It is neither of the systems that you raised. It’s not the Iskander. It’s not the other one, X-100 [sic; X-101].” And the missile “is in development.”

The cruise missile apparently was first test-launched at Kapustin Yar in May 2007. Russian news media reports at the time identified the missile as the R-500 cruise missile. Sergei Ivanov was present at the test and Vladimir Putin confirmed that “a new cruise missile test” had been carried out.

Public range estimates vary tremendously. One report claimed last month that the range of the R-500 is 1,243 miles (2,000 km), while most other reports give range estimates from 310 miles (500 km) and up. Images on militaryrussia.ru that purport to show the R-500 GLCM 2007-test show dimensions very similar to the SS-N-21 SLCM (see comparison below).

Images on militaryrussia.ru that purport to show the R-500 GLCM 2007-test show dimensions very similar to the SS-N-21 SLCM

The wildly different range estimates might help explain why it took the U.S. Intelligence Community six years to determine a treaty violation. A State Department spokesperson said yesterday that the Obama administration “first raised this issue with Russia last year. ”The previous Compliance Report from 2013 (data cut-off date December 2012) did not call a treaty violation, and the 2013 NASIC report did not mention any GLCM at all.

So either there must have been serious disagreements and a prolonged debate inside the Intelligence Community about the capability of the GLCM. Or the initial flight tests did not exceed 310 miles (500 km) and it wasn’t until a later flight test with an extended range – perhaps in 2012 or 2013 – exceeded the INF limit that a violation was established. Obviously, much uncertainty remains.

Deployment Underway at Luga?

The Compliance Report, which covers through December 2013, does not state whether the GLCM has been deployed and one senior government official consulted recently did not want to say. And the New York Times in January 2014 quoted an unnamed U.S. government official saying the missile had not been deployed.

But since then, important developments have happened. Last month, Russian defense minister Sergei Shuigu visited the 26 Missile Brigade base near Luga south of Saint Petersburg, approximately 75 miles (120 km) from the Russian-Estonian border. A report of the visit was posted on the Russian Ministry of Defense’s web site on June 20th.

The report describes introduction of the Iskander-M ballistic missile weapon system at Luga, a development that has been known for some time. But it also contains a number of photos, one of which appears to show transfer of an Iskander-K cruise missile canister between two vehicles.

The fact that the Russian MOD report shows both what appears to be the Iskander-M and the Iskander-K systems is interesting because images from another visit by defense minister Shuigo to the 114th Missile Brigade in Astrakhanskaya Oblast in June 2013 also showed both Iskander-M and Iskander-K. During that visit, Shoigu said that Iskander was delivered in a complete set, rather than “piecemeal” as done before. That could indicate that the Iskander units are being equipped with both the Iskander–M ballistic missile and Islander-K cruise missile, and that Luga is the first western missile brigade to receive them.

A satellite image from April 9, 2014, shows significant construction underway at the Luga garrison that appears to include missile storage buildings and launcher tents for the Iskander weapon system (see image below). The base is upgrading from the Soviet-era SS-21 (Tochka) short-range ballistic missile.

Construction underway at the 26th Missile Brigade base near Luga show what appear to include missile storage buildings and launcher tents for the Iskander weapon system.

The eight garage-tents that are visible on the satellite photo also appear on the ground photos the Russian MOD published of defense minister Shuigo’s visit to Luga. The garages are in two groups bent in a slight angle that is also visible one of the ground photos (see middle photo of collage below).

Earlier this month, the acting commander of the western military district told Interfax that infrastructure to house the missiles is being built at the base where they will be stationed. And Russian news media reported that the first of the three Missile Battalions at Luga had completed training and the Iskander was accepted for service on July 8, 2014. The remaining two Battalions will complete training in September, at which time the 26th Missile Brigade is scheduled to conduct a launch exercise in the western military district.

What the Report Doesn’t Say

Troubling as the alleged INF violation is, the Compliance Report also brings some good news by way of what it doesn’t say.

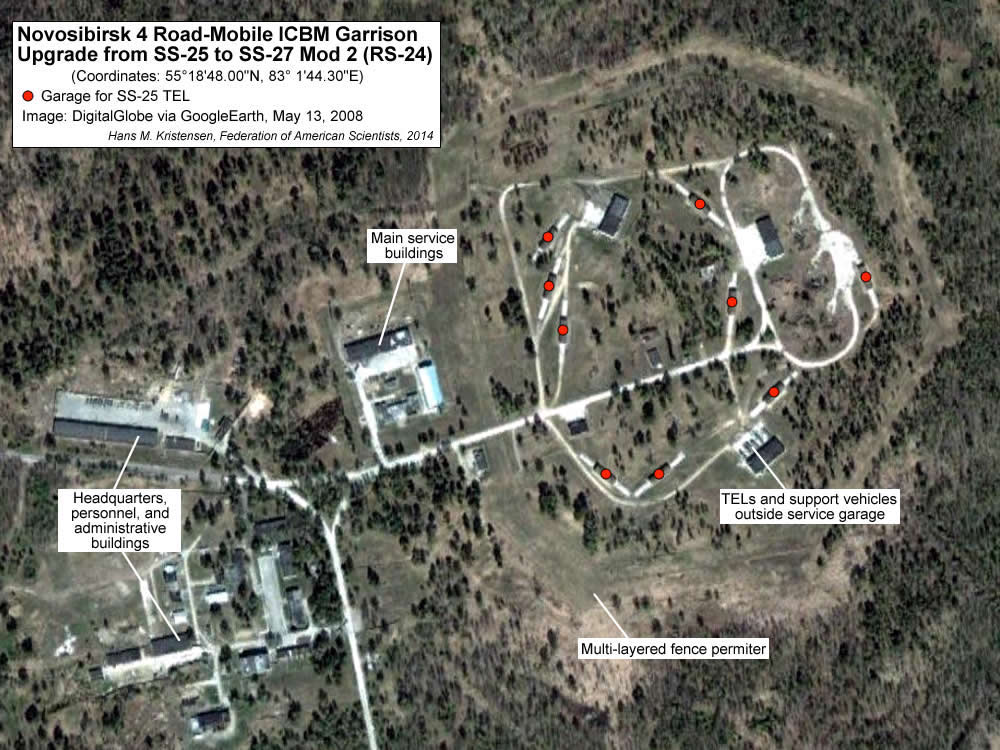

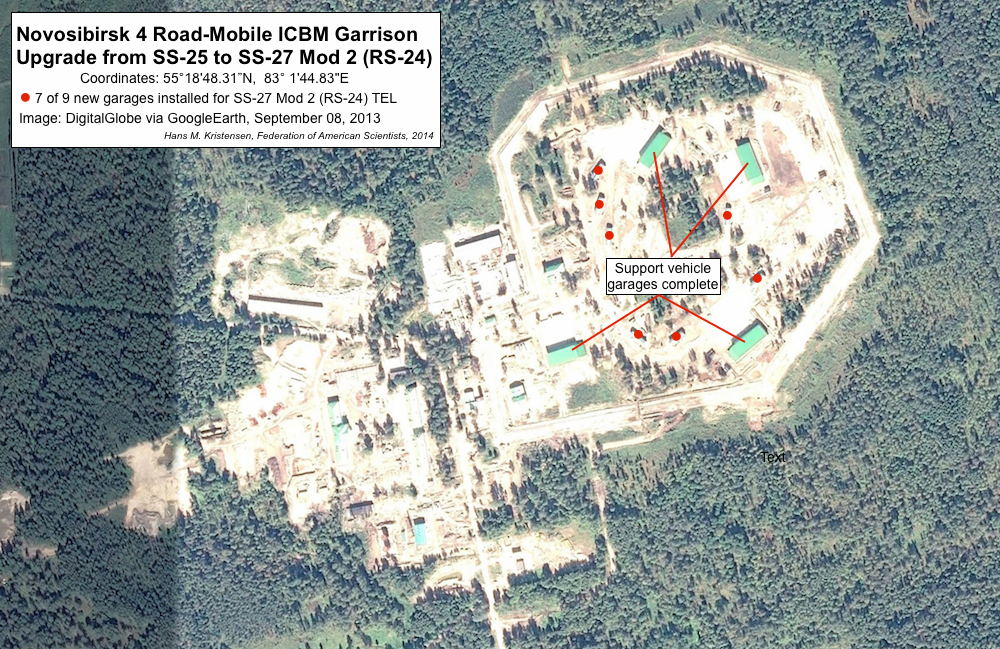

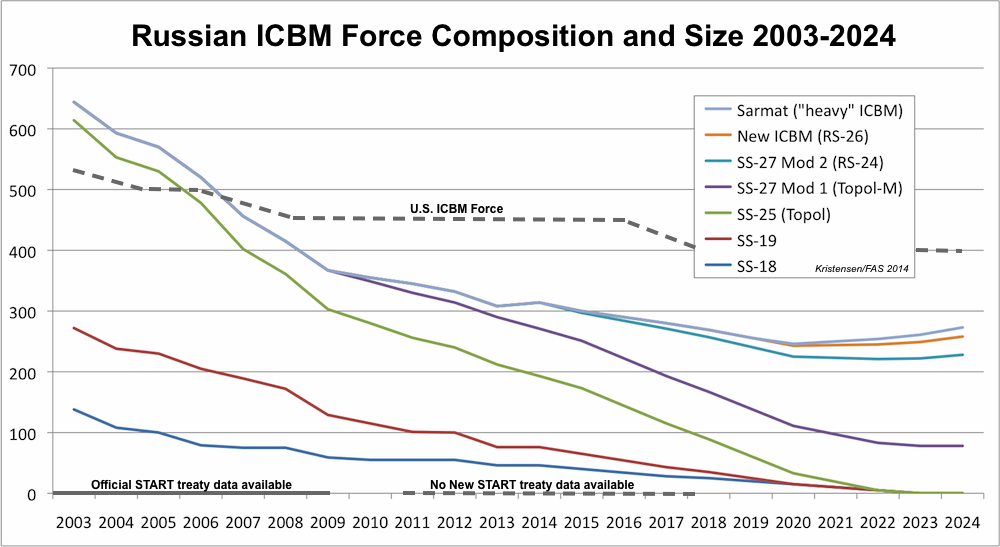

For example, the Compliance Report does not say that any Russia ballistic missiles violate the INF. Some speculated last year that Russia’s development of a new long-range ballistic missile – the RS-26, a modified version of the RS-24 (SS-27 Mod 2) intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) – was a violation because it was test-flown at less than 5,500 km. I challenged that at the time and the 2013 NASIC report clearly listed the “new ICBM” with a range of more than 5,500 km. The Compliance Report indirectly confirms that Russian longer-range ballistic missiles have not been found to be in violation of the INF.

Nor does the Compliance Report declare any shorter-range ballistic missiles – such as the SS-26 Iskander-M – to be in violation of the treaty. This is important because there have been rumors that the Iskander-M might have a range of 310 miles (500 km) or more.

As such, the Compliance Repot helpfully confirms indirectly that the Iskander-M range must be less than 310 miles (500 km). This conclusion matches the 2013 NASIC report, which lists the Iskander-M (SS-26) range as 186 miles (300 km).

The report also indirectly lay to rest rumors that the violation might have involved a sea-launched cruise missile that was test-launched on land.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The alleged Russian violation of the INF treaty is serious stuff that calls into question Russia’s status as a trustworthy country. That status has already taken quite a few hits recently with the annexation of Crimea and the proxy-war in eastern Ukraine. But it’s one thing for a country to withdraw from a treaty because it’s deemed no longer to serve national security interests; it’s quite another to cheat while pretending to abide by it.

That’s why the U.S. accusation is so serious that Russia has violated the terms of the 1987 INF Treaty by producing, flight-testing, and possessing a GLCM with a range of more than 310 miles (500 km). Unfortunately, the lack of details in the unclassified report will leave the public guessing about what the violation is and enable Russian officials to reject the accusation (at least in public) as unsubstantiated.

Shortly after the 2007 flight-test of the GLCM now seen as violating the INF, President Putin warned that it would be difficult for Russia to adhere to the INF Treaty if other countries developed INF weapons. He didn’t mention the countries but Russian defense experts said he meant China, India, and Pakistan.

By that logic, one would have expected Russia’s first deployment of Iskander-K and its GLCM to be in eastern or central Russia. Instead, the first deployment appears to be happening at Luga in the western military district, even though the United States no longer has GLCMs deployed in Europe.

There is a real risk that Russia will now formally withdraw from the INF Treaty. Doing so would be a serious mistake. First, it is because of the INF Treaty that Russia no longer faces quick-strike INF missiles in Europe. Moreover, continuing the INF treaty is Russia’s best hope of achieving some form of limitations on other countries’ INF weapons. But instead of trying to sell INF limitations to China and India, Putin has been busy selling them advanced weapons, including cruise missiles.

In the meantime, Russia must restore its compliance with the INF Treaty in a transparent a verifiable manner. Doing anything else will seriously undermine Russia’s international status and isolate it at next year’s nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Review Conference.

Some will use Russia’s alleged INF violation to argue that the United States should withdraw from the INF treaty and abandon other arms control initiatives because Russia cannot be trusted. But the treaty has served its purpose well and it is in the U.S. and European interest to maintain and promote its norms to the extent possible. Besides, the United States and NATO have plenty of capability to offset any military challenge a potential widespread Russian GLCM deployment might pose.

Moreover, arms control treaties, such as the New START Treaty or future agreements, can have significant national security benefits by allowing the United Stated and its allies better confidence in monitoring the status and development of Russian strategic nuclear forces. For arms control opponents to use the INF violation to prevent further reductions of nuclear weapons that can otherwise hit American and allied cities seems downright irresponsible.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

What Are Acceptable Nuclear Risks?

When I read Eric Schlosser’s acclaimed 2013 book, Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, I found a tantalizing revelation on pages 170-171, when it asked, “What was the ‘acceptable’ probability of an accidental nuclear explosion?” and then proceeded to describe a 1957 Sandia Report, “Acceptable Premature Probabilities for Nuclear Weapons,” which dealt with that question.

Unable to find the report online, I contacted Schlosser, who was kind enough to share it with me. (We owe him a debt of gratitude for obtaining it through a laborious Freedom of Information Act request.) The full report, Schlosser’s FOIA request, and my analysis of the report are now freely accessible on my Stanford web site. (The 1955 Army report, “Acceptable Military Risks from Accidental Detonation of Atomic Weapons,” on which this 1957 Sandia report builds, appears not to be available. If anyone knows of an existing copy, please post a comment.)

Using the same criterion as this report*, which, of course, is open to question, my analysis shows that nuclear terrorism would have to have a risk of at most 0.5% per year to be considered “acceptable.” In contrast, existing estimates are roughly 20 times higher.**

My analysis also shows, that using the report’s criterion*, the risk of a full-scale nuclear war would have to be on the order of 0.0005% per year, corresponding to a “time horizon” of 200,000 years. In contrast, my preliminary risk analysis of nuclear deterrence indicates that risk to be at least a factor 100 and possibly a factor of 1,000 times higher. Similarly, when I ask people how long they think we can go before nuclear deterrence fails and we destroy ourselves (assuming nothing changes, which hopefully it will), almost all people see 10 years as too short and 1,000 years as too long, leaving 100 years as the only “order of magnitude” estimate left, an estimate which is 2,000 times riskier than the report’s criterion would allow.

In short, the risks of catastrophes involving nuclear weapons currently appear to be far above any acceptable level. Isn’t it time we started paying more attention to those risks, and taking steps to reduce them?

* The report required that the expected number of deaths due to an accidental nuclear detonation should be no greater than the number of American deaths each year due to natural disasters, such as hurricanes, floods, and earthquakes.

** In the Nuclear Tipping Point video documentary Henry Kissinger says, “if nothing fundamental changes, then I would expect the use of nuclear weapons in some 10 year period is very possible” – equivalent to a risk of approximately 10% per year. Similarly, noted national security expert Dr. Richard Garwin testified to Congress that he estimate the risk to be in the range of 10-20 percent per year. A survey of national security expertsby Senator Richard Lugar was also in the 10% per year range.

Italy’s Nuclear Anniversary: Fake Reassurance For a King’s Ransom

A new placard at Ghedi Air Base implies that U.S. nuclear weapons stored at the base have protected “the free nations of the world” after the end of the Cold War. But where is the evidence?

By Hans M. Kristensen

In December 1963, a shipment of U.S. nuclear bombs arrived at Ghedi Torre Air Base in northern Italy. Today, half a century later, the U.S. Air Force still deploys nuclear bombs at the base.

The U.S.-Italian nuclear collaboration was celebrated at the base in January. A placard credited the nuclear “NATO mission” at Ghedi with having “protected the free nations of the world….”

That might have been the case during the Cold War when NATO was faced with an imminent threat from the Soviet Union. But half of the nuclear tenure at Ghedi has been after the end of the Cold War with no imminent threat that requires forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Instead, the nuclear NATO mission now appears to be a financial and political burden to NATO that robs its armed forces of money and time better spent on non-nuclear missions, muddles NATO’s nuclear arms control message, and provides fake reassurance to eastern NATO allies.

Italian Nuclear Anniversary

Neither the U.S. nor Italian government will confirm that there are nuclear weapons at Ghedi Torre Air Base. The anniversary placard doesn’t even include the word “nuclear” but instead vaguely refers to the “NATO mission.”

But there are numerous tell signs. One of the biggest is the presence of the 704th Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS), a U.S. Air Force unit of approximately 134 personnel that is tasked with protecting and maintaining the 20 U.S. B61 nuclear bombs at the base. The MUNSS would not be at the base unless there were nuclear weapons present. There are only four MUNSS units in the U.S. Air Force and they’re all deployed at the four European bases where U.S. nuclear weapons are earmarked for delivery by aircraft of the host nation.

A satellite photo from March this year shows part of the nuclear infrastructure at Ghedi Torre Air Base. Click on image to see full size.

Another tell sign is the presence of NATO Weapons Maintenance Trucks (WMT) at Ghedi. NATO has 12 of these trucks that are specially designed to enable field service of nuclear bombs at the storage bases in Europe. A satellite image provided by Digital Globe via Google Earth shows a WMT parked near the 704th MUNSS quarters at Ghedi on March 12, 2014. An older image from September 28, 2009, shows two WMTs at the same location (see image above).

These trucks will drive out to the 11 individual Protective Aircraft Shelters (PAS) that are equipped with underground Weapons Storage and Security System (WS3) vaults to service the B61 bombs. The WS3 vaults at Ghedi were completed in 1997; before that the weapons were stored in bunkers outside the main base. Once the truck is inside the shelter, the B61 is brought up from the vault, disassembled into its main sections as needed, and brought into the truck for service.

It is during this process of weapon disassembly when the electrical exclusion regions of the nuclear bomb are breached that a U.S. Air Force safety review in 1997 warned that “nuclear detonation may occur” if lightning strikes the shelter.

NATO is in the process of replacing the WMTs with a fleet of new nuclear weapons maintenance trucks known as the Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS). The trailers will have improved lightning protection. NATO provided $14.7 million for the program in 2011, and in July 2012 the U.S. Air Force awarded a $12 million contract to five companies in the United States to build 10 new STMS trailers for delivery by June 2014.

NATO’s new mobile nuclear weapons maintenance system is scheduled for delivery to European nuclear bases in 2014. Click image to see full size.

The new trailers will be able to handle the new B61-12 guided standoff nuclear bomb that is planned for deployment in Europe from 2020. The B61-12 apparently will be approximately 100 lbs pounds (~45 kilograms) heavier than the existing B61s in Europe (see slide below) – even without the internal parachute. This suggests that a fair amount of new or modified components will be added. To better handle the heavier B61-12, each trailer will be equipped with hoist rails.

The new B61-12 bomb will be heavier than the B61s currently deployed in Europe. For pictures of actual B61-12 features, click here.

The deployment to Ghedi 50 years ago was not the earliest or only deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons to Italy. During the Cold War, ten different U.S. nuclear weapon systems were deployed to Italy. The first weapons to arrive were Corporal and Honest John short-range ballistic missiles in August 1956. They were followed by nuclear bombs in April 1957 and nuclear land mines in 1959. All but one – nuclear bombs – of these nuclear weapon systems have since been withdrawn and scrapped.

A decade ago, most B61s in Europe were stored in Germany and the United Kingdom, but today, Italy has the honor of being the NATO country with the most U.S. nuclear weapons deployed on its territory; a total of 70 of all the 180 B61 bombs remaining in Europe (39 percent). Italy is also the only country with two nuclear bases: the Italian base at Ghedi and the American base at Aviano. Aviano Air Base is home to the U.S. 31st Fighter Wing with two squadrons of nuclear-capable F-16 fighter-bombers. One of these, the 555th Fighter Squadron, was temporarily forward deployed to Lask Air Base in Poland in March 2014.

The nuclear “NATO mission” that the 6th Stormo wing at Ghedi Torre Air Base serves means that Italian Tornado aircraft are equipped and Italian Tornado pilots are trained in peacetime to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons in wartime. This arrangement dates back to before the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), but it is increasingly controversial because Italy as a signatory to the NPT has pledged “not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons…or of control over such weapons…directly, or indirectly.”

The United States, also a signatory to the NPT, has committed “not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons…or control over such weapons…directly, or indirectly; and not in any way to assist, encourage, or induce any non-nuclear-weapon State to…acquire nuclear weapons…, or control over such weapons….”

In peacetime, the B61 nuclear bombs at Ghedi are under the custody of the 704th MUNSS, but the whole purpose of the NATO mission is to equip, train and prepare in peacetime for “transfer” and “control” of the U.S. nuclear bombs to the Italian air force in case of war.

The Nuclear Burden

Maintaining the NATO nuclear strike mission in Europe does not come cheap or easy but “steals” scarce resources from non-nuclear military capabilities and operations that – unlike tactical nuclear bombs – are important for NATO.

Italy pays for the basing of the U.S. Air Force 704th MUNSS at Ghedi, for security upgrades needed to protect the weapons at the base, and for training pilots and maintaining Tornado aircraft to meet the stringent certification requirements for nuclear strike weapons. Moreover, the cost of securing the B61 bombs at the European bases is expected to more than double over the next few years (to $154 million) to meet increased U.S. security standards for storage of nuclear weapons.

But these costs are getting harder to justify given the serious financial challenges facing Italy. The air force’s annual flying hours dropped form 150,000 in 1990 to 90,000 in 2010, training reportedly declined by 80 percent from 2005 to 2011, and training for air operations other than Afghanistan apparently has been “pared to the bone.” In addition, the Italian defense posture is in the middle of a 30-percent contraction of the overall operational, logistical and headquarters network spending. The F-35 fighter-bomber program, part of which is scheduled to replace the current fleet of Tornados in the nuclear strike mission, has already been cut by a third and the new government has signaled its intension to cut the program further.

Under such conditions, maintaining a nuclear mission for the Italian air force better be really important.

Most of the costs of the European nuclear mission are carried by the United States. Over the next decade, the United States plans to spend roughly $10 billion to modernize the B61 bomb, over $1 billion more to make the new guided B61-12 compatible with four existing aircraft, another $350 million to make the new stealthy F-35 fighter-bomber nuclear-capable, and another $1 billion to sustain the deployment in Europe.

This adds up to roughly $12.5 billion for sustaining, securing, and modernizing U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe over the next decade. Whether the price tag is worth it obviously must to be weighed against the security benefits it provides to NATO, how well the deployment fits with U.S. and NATO nuclear arms control policy, and whether there are more important defense needs that could benefit from that level of funding.

Fake Versus Real Reassurance

The anniversary placard displayed at Ghedi Air Base claims that the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs have “protected the free nations of the world” even after the end of the Cold War. And during the nuclear safety exercise at Ghedi in January, the commander of the U.S. Air Force 52nd Fighter Wing told the U.S. and Italian security forces that “your mission today is still as relevant as when together our country stared down the Soviet Union alongside a valued member of our enduring alliance.” (Emphasis added).

That is probably an exaggeration, to put it mildly. In fact, it is hard to find any evidence that the deployment of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe after the end of the Cold War has protected anything or that the mission is even remotely as relevant today. The biggest challenge today seems to be to protect the weapons and to find the money to pay for it.

NATO’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, moreover, strongly suggests that NATO itself does not attribute any real role to the non-strategic nuclear weapons in reassuring eastern NATO allies of a U.S. commitment to defend them. Yet this reassurance role is the main justification used by proponents of the deployment. In hindsight, the reassurance effect appears to be largely doctrine talk, while NATO’s actual response has focused on non-nuclear forces and exercises.

To the extent that a potential nuclear card has been played, such as when three B-52 and two B-2 nuclear-capable bombers were temporarily deployed to England earlier this month, it was done with long-range strategic bombers, not tactical dual-capable aircraft. The fact that nuclear fighter-bombers were already in Europe seemed irrelevant. The same was done in March 2013, when the United States deployed long-range bombers over Korea to reassure South Korea and Japan against North Korean threats.

No eastern European ally has said: “Hold the bombers, hold the paratroopers, hold the naval exercises! The B61 nuclear bombs in Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Turkey are here to reassure us against Russia.”

In the real world, the non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe are fake reassurance because they are useless and meaningless for the kind of crises that face NATO allies today or in the foreseeable future. NATO pays a king’s ransom for the deployment with very little to show for it.

President Obama has asked for $1 billion to reassure Europe against Russia. But he could get a dozen non-nuclear European Reassurance Initiatives for the price of sustaining, modernizing, and deploying the non-strategic nuclear bombs in Europe. Doing so would help “put an end to Cold War thinking” as he promised in Prague five years ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

DOD Report Shows Chinese Nuclear Force Adjustments and US Nuclear Secrecy

The Pentagon’s latest report to Congress on Chinese military developments cost $89.000 to prepare but no longer includes a list of China’s nuclear arsenal.

The Pentagon’s latest annual report to Congress on the Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China describes continued broad modernization and growing reach of Chinese military forces and strategy.

There is little new on the nuclear weapons front in the 2014 update, however, which describes slow development of previously reported weapons programs. This includes construction of a handful of ballistic missile submarines; the first of which the DOD predicts will begin to sail on deterrent patrols later this year.

It also includes the gradual phase-out of the old DF-3A liquid-fuel ballistic missile and the apparent – and surprising – stalling of the new DF-31 ICBM program.

Like all the other nuclear-armed states, China is modernizing its nuclear forces. China earns the dubious medal (although not in the DOD report) of being the only nuclear weapons state party to the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty that is increasing it nuclear arsenal. Far from a build-up, however, the modernization is a modest increase focused on ensuring the survivability of a secure retaliatory strike capability (see here for China’s nuclear arsenal compared with other nuclear powers).

The report continues the Obama administration’s don’t-show-missile-numbers policy. Up until 2010, the annual DOD reports included a table overview of the composition of the Chinese missile force. But the overview gradually became less specific in until it was completed removed from the reports in 2013.

The policy undercuts the administration’s position that China should be more transparent about its military modernization by indirectly assisting Chinese government secrecy.

The main nuclear issues follow below.

Land-Based Nuclear Missile Developments

The DOD report formally identifies the new road-mobile ICBM under development as the DF-41, rumored at least since 1997 to be in development. The missile might “possibly [be] capable of carrying multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRV),” according to DOD. That obviously doesn’t mean that the DF-41 will carry them; the DF-5A has also been assessed for years to be capable of carrying MIRV without ever doing so.

The report lends some support to the assessment – although not explicitly – that deployment of the DF-31 ICBM has ceased after only 5-10 launchers deployed in a single brigade.

Instead, the focus of the road-mobile ICBM modernization appears to have shifted to the DF-31A ICBM, of which the DOD report predicts that more will be deployed by 2015.

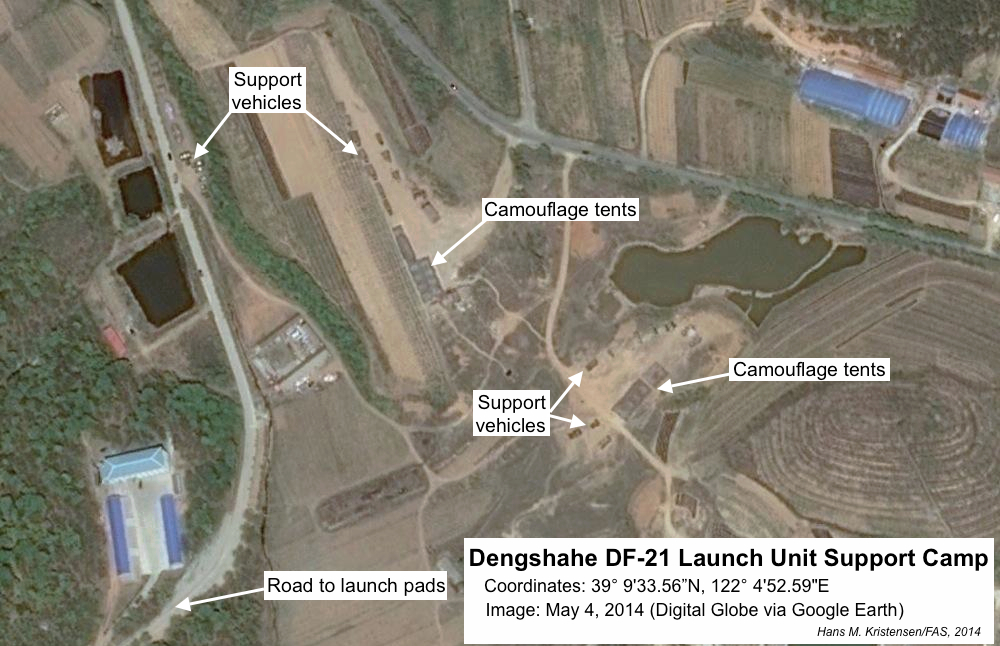

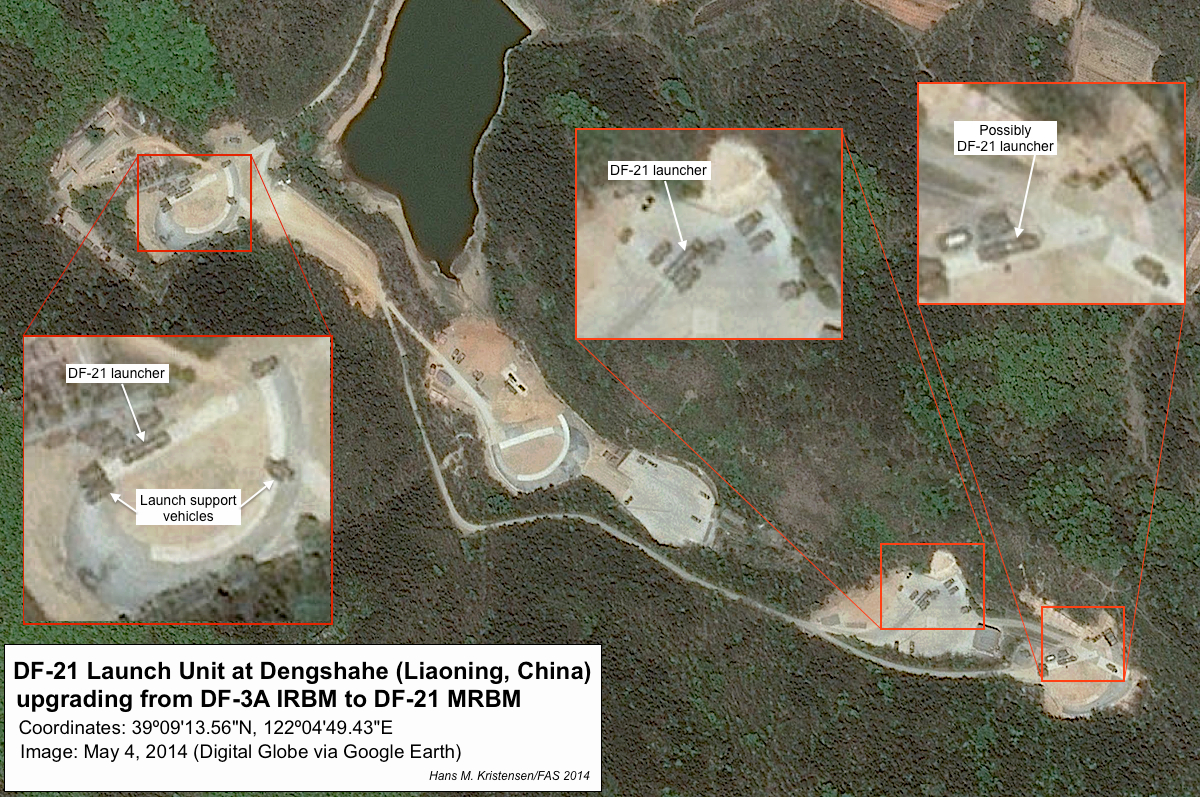

The liquid-fuel DF-3A (CSS-2) IRBM is not mentioned in the 2014 report, an indication that the 3.3-megaton weapon system has finally been retired after 42 years in service. The last DF-3A-equipped Second Artillery brigade – the 810 Brigade north of Dalian in the Liaoning province – was seen in May 2014 to have been converted to the solid-fuel medium-range DF-21 MRBM.

The 2014 DOD report appears to indicate that the 3.3-megaton, liquid-fuel DF-3A IRBM has been retired after 42 years in service.

The only other transportable liquid-fuel ballistic missile, the DF-4 (CSS-3) ICBM, is still operational with 10-15 launchers deployed in one or two brigades. But the missile is expected to be retired soon. When that happens, the only liquid-fuel ballistic missile left in the Chinese arsenals will be the 20 silo-based DF-5As (CSS-4 Mod 1) ICBM, which are still being ungraded.

The report also mentions conventional ballistic missiles under development, including several medium-range versions. That includes that anti-ship version of the DF-21 (CSS-5) – the DF-21D, which the report designates as the CSS-5 Mod 5. That suggests that other conventional MRBMs may also be under development.

Sea-Based Nuclear Missile Developments

The DOD report states that three Jin-class (Type 094) SSBNs have been delivered and that two more are in various stages of construction. One of these was seen at the Bohai shipyard in October 2013. After the Jin-program is completed, DOD expects that China will proceed to its next-generation SSBN (Type 096) over the next decade.

The report makes the prediction that “China is likely to conduct its first nuclear deterrence patrols with the JIN-class SSBN in 2014,” assuming that the JL-2 SLBM will finally become operational.

The DOD report predicts that the Jin-class SSBNs (one seen here at Xiaopingdao) likely will conduct China’s first “nuclear deterrent patrols” in 2014, even though the Chinese Central Military Commission is through to insist on central control of Chinese warheads under normal circumstances.

The prediction of the upcoming nuclear deterrent patrols is controversial given that the Chinese leadership so far has been very reluctant to hand over nuclear weapons to the military under normal circumstances. China has never conducted a SSBN deterrent patrol before and a Jin SSBN deploying with nuclear warheads loaded on its SLBMs would constitute a significant change in Chinese nuclear operational policy. It would also constitute the first-ever deployment of Chinese nuclear weapons outside the land-territory of China.

Nuclear-Capable Cruise Missile Developments

The DOD report does not explicitly attribute nuclear capability to China’s growing inventory of land-attack cruise missiles. Yet the 2013 NASIC report designates the DH-10 ground-launched cruise missile as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation given to the Russian AS-4 and the Pakistani Ra’ad and Babur cruise missiles, weapons widely assumed to be nuclear-capable.

The DH-10 ground-launched land-attack cruise missile is described by NASIC as “conventional or nuclear,” the same designation given to Russian and Pakistani dual-capable nuclear cruise missiles.

There are widespread rumors on Chinese Internet sites that the DH-10 has been modified for delivery by the H-6K intermediate-range bomber. It is unknown if that includes the apparently nuclear-capable version.

In addition, US Air Force Global Strike Command last year attributed the CJ-20 air-launched cruise missile with nuclear capability, but neither NASIC nor the DOD does so.

Additional background: FAS Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2013

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The Evolution of the Senate Arms Control Observer Group

In March 2013, the Senate voted down an amendment offered by Senator Rand Paul (R-KY) to cut $700,000 from their budget that was set-aside for the National Security Working Group (NSWG). What many did not realize at the time was that this relatively small and obscure proposed cut would have eliminated one of the last traces of the bipartisan Congressional approach to debating arms control.

The NSWG first began as the Arms Control Observer Group, which helped to build support for arms control in the Senate. In recent years, there have been calls from both Democrats and Republicans to revive the Observer Group, but very little analysis of the role it played. Its history illustrates the stark contrast in the Senate’s attitude and approach to arms control issues during the mid- to late 1980s compared with the divide that exists today between the two parties.

The Arms Control Observer Group

The Arms Control Observer Group was first formed in 1985. At the time, the United States was engaged in talks with the Soviet Union on the Intermediate Nuclear Forces Treaty. To generate support for ongoing negotiations, Majority Leader Senator Bob Dole (R-KS), and Minority Leader Senator Robert Byrd (D-WV), with the endorsement of President Ronald Reagan, created the bipartisan Arms Control Observer Group. The Observer Group consisted of twelve senators, with four senators, two from each party, serving as co-chairs and created an official role for senators to join U.S. delegations as they negotiated arms control treaties. As observers, its members had two duties: to consult with and advise U.S. arms control negotiating teams, and “to monitor and report to the Senate on the progress and development of negotiations.”

During meetings with U.S. State Department negotiators, senators were able to present their views, ask questions, and even engage in candid and confidential exchanges of ideas and information. Senators were also allowed to meet with members of the Soviet delegations on an “informal” basis. The Observer Group believed that the “interplay of ideas” would assist negotiators and, if negotiations failed, the members would help their fellow senators explain the reasons why to the American public.

The Observer Group served a number of purposes. First, it was intended to supplement the activities of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. Senator Byrd argued that the process that existed up until that point—where the Foreign Relations Committee became experts on treaties and the full Senate only began to understand the issues after the negotiation—was not functioning properly. Its creators argued, “the full Senate has focused its attention in the past only sporadically on the vital aspects of arms control negotiations, usually developing a knowledge and understanding of the issues being negotiated after the fact…the result of this fitful process has been generally unsatisfactory in recent years.” During the previous decade, the Executive Branch had failed to garner enough Senate support for several arms control initiatives: the Peaceful Nuclear Explosions Treaty of 1976, the Threshold Test Ban Treaty of 1974, and the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty (SALT II) of 1979, none of which were ratified by the United States. Although there had been previous attempts to involve senators in arms control negotiations, the Observer group provided “more regular and systematic involvement” from the full Senate long before a vote took place.

The formation of the Observer Group publicly demonstrated the important role of arms control in national security matters. The resolution that created the group states that senators have the “obligation to become as knowledgeable as possible concerning the salient issues, which are being addressed in the context of the negotiating process. Any accord with the Soviet Union to control or reduce our strategic weapons carries considerable weight for our nation.” According to Senator Sam Nunn (D-GA), a founding member of the Observer Group, “the goal [was] to have the Senate fulfill both halves of its constitutional responsibilities, not only the consent half—that’s what we’ve been looking to primarily in the past—but also the advice half.”

Additionally, the Observer Group helped develop institutional knowledge and expertise on arms control within the Senate. The Group’s founding members stated that they believed it was necessary to become “completely conversant” in issues related to treaty negotiations and that such knowledge was “critical” to the Senate’s understanding of the issues involved. To achieve that goal, they held regular behind closed-door briefings on negotiations for senators and their staff and some staffers were able to review related classified materials. Observer Group members were conversant in issues related to previous arms control treaties, missile defense, the connection between strategic offense and defense, and treaty compliance.

Above all, the Observer Group was intended to help build bipartisan support for President Reagan’s arms control initiatives. The group was seen as a mediating body. When it was formed, Senators Dole and Byrd co-authored a resolution stating that the Observer Group was part of “an ongoing process to reestablish a bipartisan spirit in this body’s consideration of vital national security and foreign policy issues.” Senator Richard Lugar (R-IN), who was one of the original members of the Observer Group, agreed by affirming, “The observer group is tremendously important to forming a consensus on which ratification might occur.” The Group’s 1985 report to Congress endorsed “the broad bipartisan support of the Senate for the Administration’s arms control efforts…determination to be as patient as necessary to achieve a sound agreement…the seriousness with which the Senate, including the Observer group intends to fulfill its constitutionally-mandated role in the treaty-making process.” This opinion was also shared by the Reagan administration. In a letter to Senators Dole and Byrd, Secretary of State George Shultz stated that he thought the Observer Group would help facilitate unity on arms control.

It is difficult to demonstrate the extent of its influence as the years the Observer Group was most active were also the years in which arms control was seen by both parties as a vital part of U.S. policy. The success of these initiatives was clearly not solely due to the Observer Group, but it did play a role. Every one of the original Group’s members voted in favor of the INF Treaty in 1988, which passed 93-5. Similarly, all of the senators within the Group voted in favor of ratifying the 1992 START Treaty, which passed 93-6.

The National Security Working Group

Towards the end of the 1990s, the Senate’s attitude towards arms control changed. Negotiations between the United States and Russia on a legally binding nuclear reduction treaty had stalled. The Senate had voted down the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty. Reflecting this changing point of view, in 1999, Senator Trent Lott (R-MS), wanted to further diminish the Senate’s focus and expertise on arms control issues. He proposed an amendment that expanded the Observer Group’s purview to include observing talks related to missile defense and export controls and renamed it the National Security Working Group. For nearly a decade during the George W. Bush administration, which pursued relatively little in terms of legally binding arms control agreements, the NSWG was relatively dormant.

This changed in 2009 under the Obama administration when the Executive Branch started briefing senators about the ongoing New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START) negotiations. From July 6, 2009, when President Obama and Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed an agreement to reduce American and Russian nuclear arsenals, to April 10, 2010, when they signed the negotiated treaty, the NSWG was revived in order to give senators a role in observing the negotiation process. During this ten-month period, the NSWG began meeting again. The meetings were open to members of the Armed Services and Foreign Relations committees and were well attended, with roughly 50 percent attendance from those who were invited. Senators who participated in the Working Group knew it was a serious matter and paid attention to it. As a result of their attendance, they left meetings better informed on issues related to arms control.

Throughout the course of Senate deliberation of New START, Senator Jon Kyl (R-AZ) served as the Republican Party’s key interlocutor with Democrats. Unlike his predecessors in the Observer Group, Senator Kyl did not see the Working Group as a vehicle for bipartisan cooperation and consensus building. Senator Kyl used his position as the chief negotiator to disrupt the Obama administration’s legislative agenda on arms control.

Senator Kyl used issues peripheral to the treaty, such as missile defense and modernization of the nuclear stockpile, to “slow roll” the legislative process and prevent the administration from pursuing the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty, which he ardently opposed.1 According to one account, Senator Kyl “was not using the Working Group. It was just a tool to stop the policy. There wasn’t a getting to yes option. It wasn’t there to get to yes. If the members of the group aren’t inclined to get to yes, then the mechanism won’t get them there.” Further, he “came prepared to ask tough questions, not just to listen and probe. He was there to look for chinks in the arms and attack in front of his colleagues. He wanted his colleagues to see it.”

In an effort to prevent Senator Kyl from disrupting meetings, Senate staff made the NSWG open to all members of the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services Committees. They also made sure that senior Democratic leadership was present for all of the NSWG meetings. Either Senator John Kerry (D-MA) or Carl Levin (D-MI) served as Chair and were both prepared to answer all questions and concerns.

Despite this impediment, senators still appear to have found the Working Group useful. Senator Levin, Chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee, said the NSWG provided an opportunity to bring senators in at the beginning of the negotiation process, and “through the group” there were “many opportunities to learn of the progress and details of negotiations and to provide our advice and views to the administration throughout the process.” He praised the NSWG’s work, arguing that it was a “key” part of the treaty ratification process because it allowed senators to begin meeting with the administration “early in the process of negotiation” before New START was finalized. He said that during the New START process, “members of the National Security Working Group asked a great number of questions, received answers at a number of meetings, stayed abreast of the negotiation details, and provided advice to the administration.” Finally, he added that, through the NSWG, the administration had the opportunity to respond to senators’ questions and concerns, which helped to avoid problems during the Senate’s consideration of the treaty.

The Senate was less supportive of arms control this time around. Even with senators actively involved in the NSWG, only 13 Republicans ended up supporting the treaty. Of those 13, only four Republicans were members of the Working Group (Senators Lugar, Corker, Voinovich, and Cochran). Among those four, only Senator Lugar was a particularly strong advocate for the treaty.

At best, the Working Group had a mixed track record and certainly did not have the same kind of success as the Observer Group. Only two senators traveled to observe New START negotiations. There was no spirit of cooperation or strong bipartisan support for the treaty. The Working Group essentially became a courtroom where New START could be prosecuted.

The Future of the NSWG

Since the vote on New START, the NSWG has not been any more successful in helping to foster bipartisanship. At the beginning of the 113th session of Congress, Senator Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) and Senator Marco Rubio (R-FL) were appointed co-chairs. Senator Rubio, like Senator Kyl, has attempted to impede the Obama Administration’s work on arms control.

While the cooperative atmosphere that surrounded the Arms Control Observer Group seems like an anachronism in today’s political climate, this is not meant to argue that senators within the Working Group need to agree on everything. There were major disagreements over nuclear policy during the Reagan administration and at times, heated discussions within the Observer Group. The difference was that the Observer Group was effective because the senators who were in it believed that arms control could advance U.S. national interests and wanted the group to succeed.

Today, the NSWG suffers from three broader trends within the United States that inhibit this attitude. The first is that the partisanship that exists in the Working Group is a reflection of the divisions in Congress. Given this dynamic, if there is any chance for the NSWG to serve as a valuable forum, individuals looking for the spotlight cannot be given the opportunity to hijack it. Secondly, since the end of the Cold War, detailed, negotiated arms control agreements are decreasingly seen as important to advancing U.S. national interests. There is diminishing prestige or interest in being a member of the NSWG or in supporting arms control. Thirdly, the Republican Party is far more skeptical about any legally binding international commitments than it once was.

These trends are unfortunate. The fact is that arms control still has a role to play in advancing U.S. interests and promoting international peace and stability. There are numerous issues that the United States and Russia will still need to address together. They continue to cooperate on issues related to Iran and reducing the risk of nuclear terrorism. They will likely still continue to communicate about issues related to U.S. missile defense deployment. Some think that current problems between the United States and Russia are evidence that this is not the case, but it was this kind of tension that led both countries to arms control in the first place. For this reason, diplomacy will remain an important policy tool for preventing catastrophic war between the two countries.