Nuclear Weapons At China’s 2025 Victory Day Parade

On September 3, 2025, China showcased its military power in a parade commemorating the 80th Anniversary of the end of World War II. The parade featured a large number of new military weapons and equipment, including new and modified nuclear systems that had not been previously publicly displayed. This parade was also the first time China had showcased land-, sea-, and air-launched nuclear weapons in the same parade, marking an important milestone in the country’s longtime effort to establish a nuclear triad.

As in some previous parades, the official announcer for the 2025 parade clearly distinguished between the nuclear and conventional weapon systems displayed during the parade. Hypersonic missiles such as the DF-17 and the DF-26D were grouped in conventional formations, whereas the five weapon systems that followed were explicitly referred to as being part of the nuclear formation. This language may be innocuous, but largely fits with Western descriptions of the weapons.

Although only one of the nuclear weapons presented at the parade was entirely new (the DF-61 ICBM), that and the many other systems displayed in this and previous parades – combined with the construction of three large missile silo fields and so far more than a tripling of the nuclear warhead stockpile – vividly illustrate the significant modernization and buildup of nuclear forces that China has undertaken over the past couple of decades. This buildup appears to contradict China’s obligations under the nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty and risks stimulating nuclear buildups in the United States and India – developments that would not be in China’s interest. Instead of building up the nuclear arsenal, the Chinese leadership instead should freeze it and work with the other nuclear-armed states to responsibly limit the numbers and roles of nuclear weapons.

In the sections below we describe the nuclear weapons displayed at the parade and their role in the Chinese nuclear posture.

Ground-based nuclear missiles

Based on new information from the parade footage, it seems China now has nine different versions of land-based ICBMs: DF-5A, DF-5B, DF-5C, DF-27 (not yet displayed in public), DF-31A, DF-31AG, DF-31BJ, DF-41, and DF-61. Interestingly, rather than necessarily representing incremental upgrades, many of the missiles are quite distinct from one another: five are road-mobile, and four are silo-based; three are liquid-fueled, four are solid-fueled, and two are unconfirmed; at least one carries MIRVs, at least one carries an HGV, at least one carries a multi-megaton warhead, and one may even carry a conventional warhead.

The DF-61

The DF-61 is a new missile that was grouped alongside the DF-31BJ, JL-3, and JL-1 nuclear systems during the parade, suggesting it is also nuclear. The display of the DF-61 ICBM launcher was a surprise because the Chinese Rocket Force (PLARF) is still fielding the DF-41, and the two systems are strikingly similar. In fact, the DF-61 launcher displayed at this year’s parade appears to be nearly identical to the DF-41 launcher displayed in the 2019 parade. Other than the paint job, they look the same (see image below; image sizes and angles vary slightly). This raises the question of whether the DF-61 missile is a modified version of the DF-41 missile. Another possibility is that the DF-61 is the conventional ICBM rumored to be under development by China, but that doesn’t fit with the DF-61 being displayed as part of the nuclear group. (Instead, the conventional ICBM could be the DF-27, which was not displayed at the parade.)

The DF-61 ICBM launcher displayed at the 2025 Victory Day Parade looks almost identical to the DF-41 ICBM launcher displayed in 2019.

The DF-31BJ

The vehicle identified in the parade as DF-31BJ looks different than a road-mobile launcher with its stub end of the missile canister and the personnel compartment only including the left side for the driver (see image below). It is possible that this vehicle is a missile loader and the DF-31BJ is the designation of the ICBM assigned to the three large silo fields in northern China. The “J” likely denotes the silo basing, as the Chinese character “井” or “jing” means “well” and is used by the PLA to describe silos.

The DF-31BJ is possibly a missile transport loader for the ICBMs being loaded into China’s three large silo fields.

The DOD reported last year that China probably began loading a DF-31-class solid-fuel ICBM across its three new ICBM silo fields. To do that, a missile transport and loading truck would be needed, which might be the DF-31BJ displayed at the parade. The status of the silo loading is unknown in public, but we estimated early this year that perhaps 30 silos had been loaded. While silo loading at the three silo fields has not been publicly shown, a possible load training operation at the Jilantai training complex in 2021 shows a 20-meter truck that might have been an early version of the DF-31BJ (see image below).

A possible DF-31BJ missile transporter is seen in 2021 practicing loading an ICBM into a silo at the Jilantai training complex in northern China.

The DF-5C

The long-rumored DF-5C was displayed with all three sections: the first stage on a long trailer at the rear, the upper stage on a shorter trailer, and a warhead reentry vehicle shape in the front. This is similar to the first display of the original DF-5 at the parade back in 1984 (see image below).

The DF-5C ICBM lineup in the 2025 parade is similar to the initial DF-5 display in the 1984 parade four decades ago.

The DF-5C is, according to the DOD, intended to carry a multi-megaton warhead. As such, it is probably a replacement for the DF-5A first deployed in the 1980s, which is already equipped with a multi-megaton warhead. Another version, known as the DF-5B, is capable of delivering up to five smaller MIRVs.

Similar to the DF-5 in the 1984 parade, the four DF-5Cs were displayed with four cone-shaped reentry vehicle shapes intended to illustrate the aeroshell designed to protect the multi-megaton warhead during reentry of the atmosphere (see below).

The 2025 parade displayed the reentry vehicle shape for the DF-5C multi-megaton warhead.

Sea-based nuclear missile

The Chinese Navy displayed the JL-3 (Julang-3) sea-launched ballistic missile, which is currently being back-fitted onto modified Jin-class (Type 094A) ballistic missile submarines at their homeport on Hainan Island in the South China Sea.

The JL-3 displayed at this year’s parade (above) looks very similar to the JL-2 displayed in the 2019 parade (below), with no visible external changes to the payload section or fuel stages.

The JL-3 has a longer range than its predecessor, JL-2, probably around 10,000 kilometers, according to the DOD. Although the DOD claims this is “giving the PRC the ability to target [the continental United States] from littoral waters,” that is not the case if the missile is launched from the South China Sea. Launching from the shallow Bohai Sea or the Yellow Sea would probably be less secure.

Air-delivered nuclear missile

For the first time, China displayed a nuclear weapons system for delivery by aircraft. This is the JL-1, or JingLei-1, translating to “sudden thunder” (not to be confused with the JL-3 or Julang-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile, which translates to “massive wave”). The official parade commentator described it as an “air-based long-range missile.”

The JL-1 air-launched ballistic missile for the H-6N bomber was displayed in the 2025 parade for the first time.

This is likely the air-launched ballistic missile (designated CH-AS-X-13 by the DOD) that the Chinese air force has been working on for several years to integrate on the H-6N intermediate-range bomber. The first bomber base to be equipped for the nuclear mission is thought to be Neixiang air base in Henan province.

The JL-1 ALBM seen loaded on the H-6N bomber. Image: @lqy99021608

The H-6N does not have an intercontinental range like Russian and U.S. bombers. To increase its range, the H-6N has been equipped with a refueling boom that enables the bomber to refuel during flight. Several H-6Ns were seen during the parade flying in formation with Y-20U tankers (the quality of images from the parade was hampered by air pollution, so an archive photo is used below), which is a converted Y-20 military transport aircraft that can refuel both bombers and fighter jets. The first known public imagery of an H-6N by a Y-20U tanker is from January 2025.

The nuclear-capable H-6N was displayed with a Y-20U tanker (archive photo).

Other Missile Launchers

The weapons described above were grouped in the nuclear part of the parade. Noticeable weapons in the conventional weapons lineup included the DF-26D (a new conventional variant of the DF-26 that also includes a nuclear version), the DF-17 medium-range hypersonic glide vehicle, and the CJ-1000 (sometimes also described as DF-1000) long-range cruise missile.

Additional Information:

• Chinese nuclear weapons, 2025

• Status of world nuclear forces

• The FAS Nuclear Information Project

This article was researched and written with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

The Next Nuclear Age: What the Washington Post Series Reveals About Our Perilous Present, from Trinity to Tehran

In the eighty years since the first successful test of a nuclear weapon, generations of effort has been spent to limit the spread of these weapons and prevent their use. The Federation of American Scientists, since our founding in 1945, has played a central role in helping understand the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and diligently worked to ensure the policy debate is informed by scientific and technical data. As part of our continuing legacy, the Global Risk program at FAS partnered with the Washington Post to publish a five part opinion series entitled: The Next Nuclear Age.

With 2000 nuclear weapons on alert, far more powerful than the first bomb tested in the Jornada Del Muerto during the Trinity Test 80 years ago, our world has been fundamentally altered. This series resurfaces clear warnings that nuclear policy is not just a relic of days gone past. Past generations had this threat at the forefront of their minds as a clear and present danger to the future civilization. However distant 80 years may feel, the threat still reaches into contemporary times with most recently the nuclear program of Iran becoming the target of strikes by the U.S. Military.

The Iran strikes are the manifestation of a debate mostly relegated to non-proliferation policy circles. We can watch as the preemptive effort to halt progress of Iran’s nuclear weapons program plays out in press conferences and analysis rather than the hypothetical. The strikes on Iran offer a unique pivot to evaluate some of the underlying assumptions about deterrence and what role the U.S. is willing to play in international institutions with our allies. There has been much analysis of the Iran strikes framed using the traditional logic of being able to halt programmatic development through brute force, i.e. bomb enrichment sites. In my assessment, more progress has been made and could continue to be made by supporting the sanctions regime and using more social coercion by partnering with our allies and supporting international institutions. When we choose to use military force, we ultimately trade in our legitimacy in the rules based order, pushing our allies to look at building their own nukes for security.

The real world implications of nuclear policy and diplomacy can be seen in the unfolding story with Iran, which is not quite done yet. The Next Nuclear Age as a five part series surfaces and grapples with the realities of living in the nuclear age and dispels myths surrounding nuclear policy and non-proliferation. Each part paints a vivid picture that reviews the history of nuclear close calls and details how the long-standing norm against proliferation is eroding. The subsequent articles describe how a nuclear war could start, who controls the use of nuclear weapons in the United States, and how a nuclear attack could unfold in the United States.

In the post Cold War Era, nuclear weapons have largely faded from the heat of popular culture however their threat is still a sobering reality. The Next Nuclear Age series serves as a reminder that the durability of the nuclear threat is omnipresent in modern life. Thousands of weapons are aimed and on high alert, one person has sole authority to launch, and a growing number of nations are considering spending billions to secure nuclear options as tensions rise.

After decades of work trying to reduce the threat of nuclear weapons, our days ahead look riskier than in years prior. The multipolar geopolitical landscape exponentially raises risks of accidents and increases excuses to jump into an arms race. Countries are falsely substituting military capability for political credibility therefore increasing risk. Our allies and institutions are being clobbered by disinformation and mistrust and we are left feeling the pinch, having to result in widely unpopular military interventions in potentially protracted conflicts.

This series showcases how the accidents, miscalculations, and escalatory spirals have more room to become trigger points. Compressed decision-making timeframes revealed in the final installment show how quickly rational deliberation can give way to existential pressure. What worries me is that we’ve given up tools in our tool box that monitor and reduce risk. We’ve traded out diplomatic solutions and investment for military build up and an expensive vanity project of Trump’s Golden Dome. Ultimately it is our responsibility as citizens to uphold policymakers to account on these weapons before the unthinkable becomes inevitable.

Part 1: Why we should worry about nuclear weapons again

The Cold War prospect of global annihilation has faded from consciousness, but the warheads remain.

By Jon B. Wolfsthal, Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda

The threat of nuclear weapons since the collapse of the Soviet Union has been largely absent from the public’s consciousness. Stockpiles have been reduced from Cold War highs but the thousands of remaining weapons could still destroy humanity.

“It is as if the lessons of the Cold War — that there is never a finish line to the arms race and that more effective nuclear weapons do not lead to stability and security — have been forgotten by the current generation of defense planners.”

The new frame of great power competition among the US, Russia and China, plus new nuclear dangers make today’s nuclear age more complicated and dangerous than the nuclear standoff between the first two major powers of the late 20th century. Nuclear policy experts refer to the U.S.-Russia-China nuclear triangle as a ‘three body problem’. However the ‘three body problem’ definition neglects the reality that nine countries have nuclear weapons. Any of the nuclear armed states could set off a global nuclear war. The public needs to relearn the language of nuclear risk and a new generation of leaders will be required to manage these dangers.

Part 2: How nuclear war could start

To understand how it could all go wrong, look at how it almost did.

By Hans Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns and Allie Maloney

Roughly 2000 nuclear weapons that are on alert at any time across the globe. These weapons are ready to launch from submarines, dropped from planes and rocketed to targets. Some are mobile, fixed or in transit; all of them are vulnerable to accidents or affected by human or technical error.

“The end of humanity could arrive in minutes — that is what makes nuclear war so different from other wars.”

If there is one thing that can be counted on, it’s that nuclear accidents are bound to happen. It’s a matter of when, not if. One of the most dangerous parts of having nuclear arsenals is that accidents involving nuclear weapons could cause an acute global crisis, involving a web of interlocking states, enemies, and adversaries. The delicate balance of crisis can be spurred towards destruction when non-nuclear conflicts spill over into an escalatory spiral towards nuclear use, spelling destruction for all involved.

Part 3: Only one American can start a nuclear war: The president

The American president has the sole authority to order a nuclear strike, even if every adviser in the room is against it.

The authority to launch nuclear weapons in the United States rests on the shoulders of only one person, the President. Codified in both law and tradition, the President has the sole authority to launch a nuclear strike that once authorized is unstoppable. The established process to order a nuclear strike, using the ‘black book’, is a well choreographed procedure designed to provide the most streamlined options to the President in a time of crisis.

“The start of nuclear war, the probable deaths of millions and the choice of which cities to decimate — the black book distills these realities into a sanitized list of options that a former military aide to President Bill Clinton likened to a “Denny’s breakfast menu.”

The Constitution grants to only Congress in Article One the right to declare war. That said, a President has unilateral legal authority to launch nuclear weapons, even if the United States or its allies have not been attacked, runs counter to the way the US system was designed to operate. Such a weighty and world altering decision ought to be made using a system of checks and balances, not by one individual.

Part 4: What’s making some countries daydream about nukes again?

With or without Iran, the number of nuclear states could double, raising the risk of catastrophe.

By Jon B. Wolfsthal, Hans Kristensen and Matt Korda

The incentives for developing nuclear weapons have changed in a world that has been rising in conflict. Paired simultaneously with reduced confidence among its allies that the United States is a reliable partner, the second largest nuclear armed state, allies and enemies alike are pushed into a new paradigm. Nuclear weapons are hard and expensive to build however with the incentives of security shifting towards development, some countries are willing to front the cost.

“Deterrence and reassurance depend on both military capability and political credibility. The credibility of a promise to protect is the fragile part of the calculus.”

A mass proliferation of nuclear weapons would ultimately cause more opportunities for accidents or misuse. This alone is a major reason why limiting the development of nuclear weapons is such a pressing issue. More weapons of mass destruction is more opportunity for things to go wrong, leading to irreversible consequences.

Part 5: How a nuclear attack on the U.S. might unfold, step by step

The American reaction to an attack is classified, but details made public paint a harrowing picture.

By Mackenzie Knight-Boyle

The process of how the U.S. would react to nuclear attack is classified; however there is a predictable path that it may follow based on public data. This article follows how a response would proceed. The ramifications on U.S. soil and abroad would be devastating.

“The defense secretary interjects, urging the president to make a decision in the next two minutes or risk losing the ability to retaliate.”

In the situation room, or wherever the President is deciding to make a launch, the space and time pushes the decision towards launch. As U.S. assets are targeted, the potential for ability to respond is shortened. Making the decision window in an accident scenario potentially just as lethal as an intentional launch. Some countries in order to amend this pressure have instituted ‘No First Launch’ policies whereby a country needs to be verifiably attacked with nuclear weapons to respond in kind – such a policy could be used in the U.S. to preempt accidental launch.

Poison in our Communities: Impacts of the Nuclear Weapons Industry across America

In 1942, the United States formally began the Manhattan Project, which led to the production, testing, and use of nuclear weapons. In August 1945, the United States dropped two nuclear weapons on Japanese cities, killing around 200,000 people by the end of 1945 and leaving survivors with cancer, leukemia and other illnesses caused by radiation exposure. While this was their only use in wartime, states have detonated nuclear weapons many times since for testing purposes, producing radioactive fallout. Many U.S. nuclear weapons production activities, including the mining of uranium and testing of the weapons themselves, have occurred outside of the continental United States. Notably, explosive testing in the Pacific islands and ocean spread radioactive fallout to Marshallese, Japanese, and Gilbertese people, forcibly displacing entire communities and producing intergenerational illnesses.

Much of the scholarship surrounding the effects of nuclear weapons on environmental and human health is framed within a potential detonation scenario. For example, studies have shown that even a regional nuclear war would cause millions of immediate deaths and trigger a “nuclear winter,” a shift in the climate that would disrupt agricultural production, thus killing hundreds of millions more through starvation. Additionally, in 2024, the United Nations General Assembly voted to create an independent scientific panel to study the health, environmental and economic consequences of nuclear war. While such research is crucial for understanding the consequences of nuclear weapons use, nuclear weapons are built, maintained, and deployed everyday, impacting communities at every stage even before detonation. Studying only the predictive futures of the use of a nuclear weapon in war is insufficient in understanding nuclear weapons’ holistic humanitarian impact. According to former Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III, “The heart of American deterrence is the people who protect us and our allies. Here at STRATCOM, you proudly stand up—day in and day out and around the clock—to defend us from catastrophe and to build a safer and more peaceful future. So let us always ensure that the most dangerous weapons ever produced by human science are managed with the greatest responsibility ever produced by human government.” Nuclear deterrence theory contends that a retaliatory nuclear strike is so threatening that an adversary will not attack in the first place. Thus, nuclear advocates often suggest that these weapons protect American citizens and the U.S. homeland. This report demonstrates, however, that the creation and sustainment of the nuclear deterrent harms members of the American public. As the United States continues nuclear modernization on all legs of its nuclear triad through the creation of new variants of warheads, missiles, and delivery platforms, examining the effects of nuclear weapons production on the public is ever more pressing.

Planning for the Unthinkable: The targeting strategies of nuclear-armed states

This report was produced with generous support from Norwegian People’s Aid.

The quantitative and qualitative enhancements to global nuclear arsenals in the past decade—particularly China’s nuclear buildup, Russia’s nuclear saber-rattling, and NATO’s response—have recently reinvigorated debates about how nuclear-armed states intend to use their nuclear weapons, and against which targets, in what some describe as a new Cold War.

Details about who, what, where, when, why, and how countries target with their nuclear weapons are some of states’ most closely held secrets. Targeting information rarely reaches the public, and discussions almost exclusively take place behind closed doors—either in the depths of military headquarters and command posts, or in the halls of defense contractors and think tanks. The general public is, to a significant extent, excluded from those discussions. This is largely because nuclear weapons create unique expectations and requirements about secrecy and privileged access that, at times, can seem borderline undemocratic. Revealing targeting information could open up a country’s nuclear policies and intentions to intense scrutiny by its adversaries, its allies, and—crucially—its citizens.

This presents a significant democratic challenge for nuclear-armed countries and the international community. Despite the profound implications for national and international security, the intense secrecy means that most individuals—not only including the citizens of nuclear-armed countries and others that would bear the consequences of nuclear use, but also lawmakers in nuclear-armed and nuclear umbrella states that vote on nuclear weapons programs and policies—do not have much understanding of how countries make fateful decisions about what to target during wartime, and how. When lawmakers in nuclear-armed countries approve military spending bills that enhance or increase nuclear and conventional forces, they often do so with little knowledge of how those bills could have implications for nuclear targeting plans. And individuals across the globe do not know whether they live in places that are likely to be nuclear targets, or what the consequences of a nuclear war would be.

While it is reasonable for governments to keep the most sensitive aspects of nuclear policies secret, the rights of their citizens to have access to general knowledge about these issues is equally valid so they may know about the consequences to themselves and their country, and so that they can make informed assessments and decisions about their respective government’s nuclear policies. Under ideal conditions, individuals should reasonably be able to know whether their cities or nearby military bases are nuclear targets and whether their government’s policies make it more or less likely that nuclear weapons will be used.

As an organization that seeks to empower individuals, lawmakers, and journalists with factual information about critical topics that most affect them, the Federation of American Scientists—through this report—aims to help fill some of these significant knowledge gaps. This report illuminates what we know and do not know about each country’s nuclear targeting policies and practices, and considers how they are formulated, how they have changed in recent decades, whether allies play a role in influencing them, and why some countries are more open about their policies than others. The report does not claim to be comprehensive or complete, but rather should be considered as a primer to help inform the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders. This report may be updated as more information becomes available.

Given the secrecy associated with nuclear targeting information, it is important at the outset to acknowledge the limitations of using exclusively open sources to conduct analysis on this topic. Information in and about different nuclear-armed states varies significantly. For countries like the United States—where nuclear targeting policies have been publicly described and are regularly debated inside and outside of government among subject matter experts—official sources can be used to obtain a basic understanding of how nuclear targets are nominated, vetted, and ultimately selected, as well as how targeting fits into the military strategy. However, there is very little publicly available information about the nuclear strike plans themselves or the specific methodology and assumptions that underpin them. For less transparent countries like Russia and China—where targeting strategy and plans are rarely discussed in public—media sources, third-country intelligence estimates, and nuclear force structure analysis can be used, in conjunction with official statements or statements from retired officials, to make educated assumptions about targeting policies and strategies.

It is important to note that a country’s relative level of transparency regarding its nuclear targeting policies does not necessarily echo its level of transparency regarding other aspects of its governance structure. Ironically, some of the most secretive and authoritarian nuclear-armed states are remarkably vocal about what they would target in a nuclear war. This is typically because those same countries use nuclear rhetoric as a means to communicate deterrence signals to their respective adversaries and to demonstrate to their own population that they are standing up to foreign threats. For example, while North Korea keeps many aspects of its nuclear program secret, it has occasionally stated precisely which high-profile targets in South Korea and across the Indo-Pacific region it would strike with nuclear weapons. In contrast, some other countries might consider that frequently issuing nuclear threats or openly discussing targeting policies could potentially undermine their strategic deterrent and even lower the threshold for nuclear use.

The Two-Hundred Billion Dollar Boondoggle

Nearly one year after the Pentagon certified the Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile program to continue after it incurred critical cost and schedule overruns, the new nuclear missile could once again be in trouble.1

An April 16th article from Defense Daily broke the news that the Air Force will have to dig new holes for the Sentinel silos.2 The service had been planning to refurbish the existing 450 Minuteman silos but recently discovered, as noted in a follow-up article from Breaking Defense, that the silos will “largely not be reusable after all.”3 Brig. Gen. William Rogers, the Air Force’s director of the ICBM Systems Directorate, cited asbestos, lead paint, and other issues with the existing silos that make refurbishment difficult.4 Air Force officials also stated that an ongoing study into missileer cancer rates played a role in the decision to build new silos.5

This news comes shortly after reports that the Air Force is planning to extend the life of the currently deployed Minuteman III ICBMs until “at least” 2050—roughly 20 years beyond their intended service lives—due to delays in the Sentinel program.6

For those who have been tracking the Sentinel development since the Air Force first conceptualized a new ICBM in the early 2010s, the reports of Minuteman life-extension likely made them pause and recall the common refrain from Sentinel proponents over the years that life-extending Minuteman III missiles would be too expensive or even impossible. “You cannot life-extend Minuteman III,” then-commander of US Strategic Command Adm. Charles Richard told reporters in 2021.7 In 2016, the Air Force told Congress that the Minuteman III was aging out, therefore the “GBSD solution” was necessary to ensure the future viability of the ICBM force (GBSD is short for Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent, the programmatic name for the ICBM before Sentinel was chosen in 2022). Air Force officials still maintain that a life-extension program for Minuteman is not possible. In their words, Minuteman will be “sustain[ed] to keep it viable until Sentinel is delivered.”8 Regardless of how the Air Force refers to the effort, it appears that Minuteman III will be made to operate well beyond its planned service life.

For some, like our team at the Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project, Sentinel’s newest struggles came as no surprise at all. For years, it has been clear to observers that this program has suffered from chronic unaccountability, overconfidence, poor performance, and mismanagement. Project benchmarks were cherry-picked, viable alternatives were prematurely dismissed, competition was discouraged, and goalposts were continuously moved. Ultimately, it will be U.S. taxpayers who pay the increasingly rising costs, and other—more critical—priorities will suffer as Sentinel continuously sucks money away from other programs.

It comes as no surprise that Sentinel was specifically named in the White House’s recent memo requiring all Major Defense Acquisition Programs more than 15% over-budget or behind schedule to be “reviewed for cancellation;” Sentinel is the poster-child for inefficiency, which the administration claims to be obsessed with eliminating.9 In order to prevent this type of mismanagement for future programs, we must first understand how Sentinel went so wrong.

How We Got Here

The Federation of American Scientists has been intensively tracking the progress of the Sentinel program for years. Throughout the acquisition process, the Air Force clung to its fundamental and counterintuitive assumption that building an entirely new ICBM from scratch would be cheaper than life-extending the current system. We now know that this assumption was wildly incorrect, but how did it reach this point?

Cherry-picked project benchmarks

When seeking to plug a capability gap, the Pentagon is required to consider a range of procurement options before proceeding with its acquisition. This process takes place over several years and culminates in an “Analysis of Alternatives”—a comparative evaluation of the operational effectiveness, suitability, risk, and life-cycle costs of the various options under consideration. This assessment can have tremendous implications for an acquisition program, as it documents the rationale for recommending a particular course of action.

The Air Force’s Analysis of Alternatives for the program that would eventually become Sentinel was conducted between 2013 and 2014, and concluded that the costs of pursuing a Minuteman III life-extension would be nearly the same as those projected for Sentinel.10 Crucially, this cost comparison was pegged to a predetermined requirement to continue deploying the same number of missiles until the year 2075.11

These benchmarks, despite having no apparent inalterable national security imperative, appear to have played a significant role in shaping perceptions of the two options. While it is now clear that Minuteman III could be—and likely will be—life-extended for several more decades, the Air Force does not have enough airframes to keep at least 400 of them in service through 2075 and maintain the testing campaign needed to ensure reliability. As a result, in order to push the ICBM force beyond 2075, the Air Force would need to life-extend Minuteman III and pursue a follow-on system after that point.

This was reportedly reflected in the Air Force’s cost analysis, which explains why the cost of the Minuteman III life-extension option was estimated by the Air Force to be roughly the same as the cost of building an entirely new ICBM.12 The service was not simply comparing the costs of a life-extension and a brand-new system; it was instead comparing the costs of pursuing Sentinel immediately on the one hand, versus a Minuteman III life-extension and development of a follow-on system on the other hand.

Of course, policymakers require benchmarks in order to make estimates: it would not be reasonable to analyze the feasibility of a particular system without considering how long and at what level that system needs to perform. However, in the case of the Sentinel, selecting those particular benchmarks at the beginning of the process essentially pre-baked the analysis before it even began in earnest.

Let’s say a different evaluation benchmark had been selected—2050, for example, rather than 2075.

In January 2025, Defense Daily reported that the Air Force would likely have to keep portions of the Minuteman III fleet in service until 2050 or later.13 This may require altering certain aspects of the Minuteman III’s deployment—such as reducing the number of deployed ICBMs or annual test launches in order to preserve airframes. While no final decisions have been made, the Air Force is clearly evaluating continued reliance on Minuteman III as a potential option, despite years of high-ranking military and political officials stating that doing so was impossible.14

Benchmarking the cost analysis at 2050 rather than 2075 would have thus yielded wildly different results. In 2012, the Air Force admitted that it cost only $7 billion to modernize its Minuteman III ICBMs into “basically new missiles except for the shell.”15 While getting those same missiles past 2050 would certainly add additional cost and complexity—particularly to replace parts whose manufacturers no longer exist—it is unfathomable that the costs would come anywhere close to those of the Sentinel program, which was estimated by the Pentagon’s Director of Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation (CAPE) in 2020 (before the critical cost overrun) to have a total lifecycle cost of $264 billion in then-year dollars.

It is particularly troubling that very few public or independent government-sponsored analyses were conducted to look into the Sentinel program’s flawed assumptions, nor the realistic possibility of a Minuteman III life-extension. Countless congressional and non-governmental attempts to push for one were stymied at every turn. In 2019, for example, dozens of lobbyists from the Sentinel contract bidders successfully helped to eliminate a proposed amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act calling for an independent study on a Minuteman III life-extension program.16

The most comprehensive public study on this issue was a 2022 report published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace under contract from the Pentagon; however, the study noted that “the iterative process through which we received information, the unclassified nature of our study, and the limited time available for investigating DOD conclusions left us unable to assess the DOD’s position regarding the technical and cost feasibility of an extended Minuteman III alternative to GBSD;” the authors ultimately concluded that a more detailed technical analysis was required in order to answer these questions.17

While the findings of such a study will never be known, it is likely that they would have supported what was clear to government watchdogs at the time and has been validated in spades since then: the assumptions baked into this program were flawed from the start, and the system’s costs would be significantly larger than initially expected. Given that the Pentagon ultimately went in the opposite direction, taxpayers are now on the hook for both a de facto Minuteman III life-extension program as well as the substantial costs associated with acquiring Sentinel—with limited further possibilities for near-term cost mitigation.

Failure to predict the true costs and needs of the program

In addition to the cherry-picked benchmarks that tipped the scales towards a brand-new ICBM, when comparing costs the Air Force made a key error in its assumptions: it assumed that the Sentinel would be able to reuse much of the original Minuteman launch infrastructure.

Some level of infrastructure modernization for the Sentinel was always planned, including building entirely new launch control centers and additional infrastructure for the launch facilities.18 However, the original plans called for reusing existing copper command and control cabling and the refurbishment—not reconstruction—of 450 silos. Both assumptions have proven incorrect, and perhaps more than anything else, now represent the single greatest driver of Sentinel’s skyrocketing costs.

While both the current cabling and launch facilities work fine for the existing Minuteman III and would presumably function similarly following a life-extension, they are apparently incompatible with Sentinel’s increasingly complex design.

The Air Force must now dig up and replace 7,500 miles of cabling with the latest fiber optic cables. Much of these cables are buried underneath private property, meaning that local landowners must lease 100-foot-wide lines on their property to the Pentagon to be dug up for multi-year periods.19

In addition, both the Air Force and Northrop Grumman have now recognized that it will take more than simple refurbishments to make the existing Minuteman III launch facilities compatible with Sentinel. Both the service and the contractor have stated that several of the assumptions regarding the conversion process that went into the 2020 baseline review have now proved to be incorrect.20

As a result, the Air Force is apparently now planning to build entirely new launch facilities to house the Sentinel, most of which will require digging new holes in the ground.21 As one Northrop Grumman official explained, “When you multiply that by 450, if every silo is a little bit bigger or has an extra component, that actually drives a lot of cost because of the sheer number of them that are being updated.”22 It is unclear whether the costs will increase beyond the new estimate released with the Nunn-McCurdy decision, but the program is clearly trending in the wrong direction.

The Air Force had been publicly teasing the prospect of digging new holes for nearly a year. At the Triad Symposium in Washington, D.C., in September 2024, Maj. Gen. Colin Connor, director of ICBM Modernization at Barksdale Air Force Base, responded to an audience question about the new silos rumor by saying, “we’re looking at all of our options.” Despite the noncommittal answer, the decision to dig new silos seems to have already been made by the time of Connor’s statement.

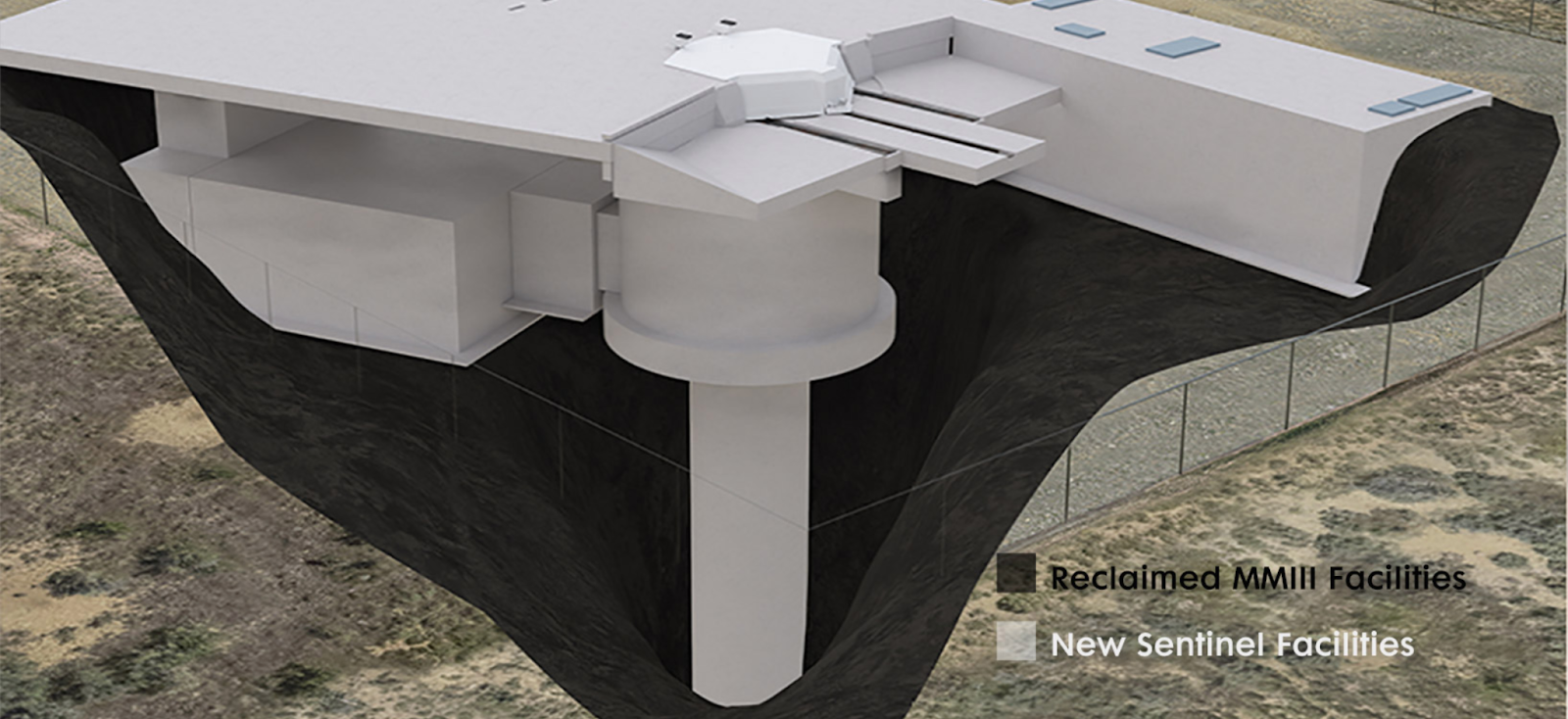

Firstly, it has since been revealed that the estimated costs of the new silos were included in the Nunn-McCurdy review process which concluded in July 2024. Additionally, although the decision was not made public until the April 16 Defense News article, Northrop Grumman may have inadvertently revealed the news much earlier. Included in the gallery of images of the Sentinel program on Northrop’s website is a digital mockup of a Sentinel launch facility. The first version of the image (see Figure A below) illustrates the Air Force’s original plan to refurbish the Minuteman III silos for Sentinel, with a key indicating the silo and silo lid as “Reclaimed MMIII Facilities.” A newer version of the image (see Figure B below) was uploaded to the gallery as early as February 2024 and shows the entire launch facility—including the silo and silo lid—as “New Sentinel Facilities.”

Original rendering of Sentinel launch facility. (Source: Northrop Grumman)

New rendering of Sentinel launch facility. (Source: Northrop Grumman)

Unwarranted overconfidence

Despite the clear concerns outlined above, the Pentagon was remarkably confident in its and Northrop Grumman’s abilities to deliver the Sentinel on-time and on-budget.

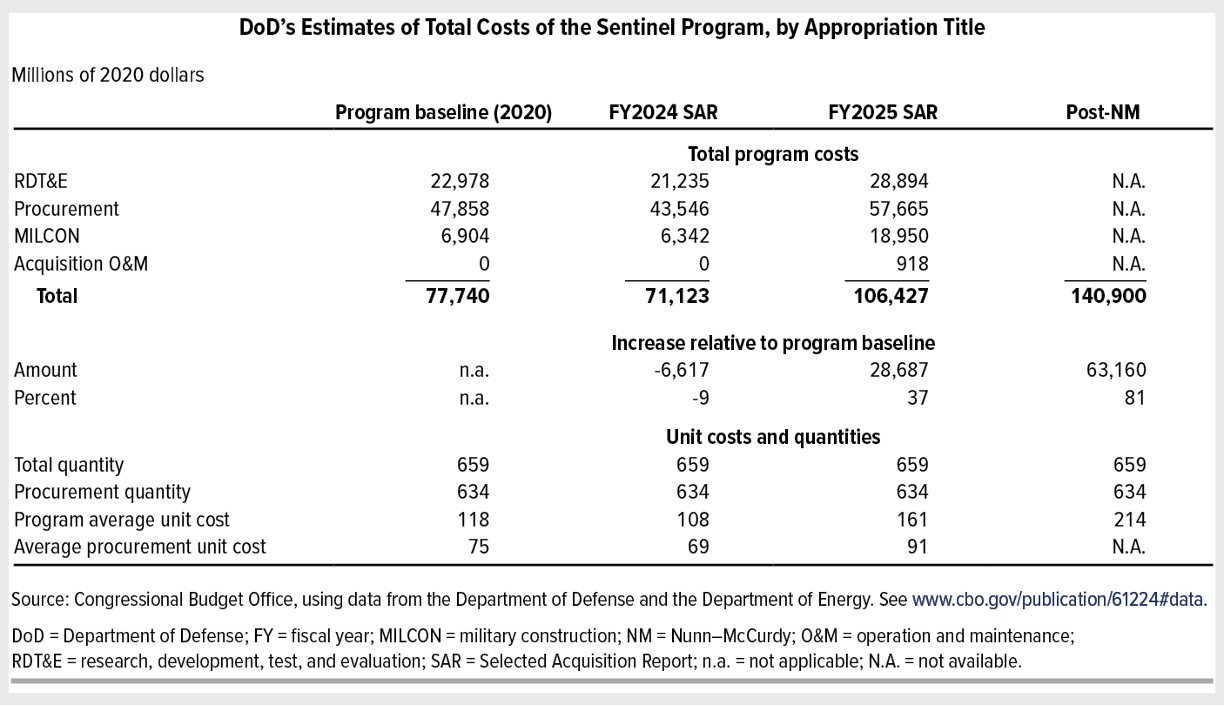

In September 2020, the Pentagon delivered its Milestone B summary report to Congress—a key decision point at which acquisition programs are authorized to enter the Engineering and Manufacturing Development phase, considered to be the official start of a program. The Milestone B report included an estimate of $95.8 billion in then-year dollars to acquire the Sentinel—a significant increase from previous estimates, but not yet the dire situation that we find ourselves in today (Figure C).

The above table from the Congressional Budget Office shows the cost growth for the Sentinel’s acquisition program between the Sentinel’s Milestone B assessment in 2020 and the post-Nunn-McCurdy review process in 2025. All costs are reflected in FY2020 dollars to allow for an accurate comparison between years.

We now know, however, based on recent statements from Pentagon and Air Force officials, that there were “some gaps in maturity” in the Milestone B report.23 Specifically, “in September of 2020, the knowledge of the ground-based segment of this program was insufficient in hindsight to have a high-quality cost estimate.” What this means is that at the most consequential stage of the program to-date, it was approved without a comprehensive understanding of the likely cost growth.

Furthermore, the Air Force was heavily delayed in creating an integrated master schedule for the Sentinel program. An integrated master schedule includes the planned work, the resources necessary to accomplish that work, and the associated budget; from the government’s perspective, it is considered to be the keystone for program management.24 Although the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment testified to Congress that “By the time you’re six months after Milestone B, you should have an integrated master schedule,” the Air Force had not met this mark.25 If the Air Force did manage to create such a schedule, it became obsolete with the Nunn-McCurdy Act’s requirement to restructure the program and rescind its Milestone B approval.

During that same hearing, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration also admitted that at that time, the service had been experiencing poor communication with Northrop Grumman, the primary contractor for the ICBM.

Performance issues also appear to have had an impact on the program. In June 2024, the Air Force removed the colonel in charge of its Sentinel program—reportedly for a “failure to follow operational procedures”—and replaced him with a two-star general, with the rank change indicating a need for greater high-level attention.26

Throughout this time, the Air Force remained overconfident in its abilities to deliver the program; in December 2020, the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics told reporters that the Air Force had “godlike insight into all things GBSD.”27 And in September 2022, the Air Force Major General responsible for Sentinel’s strategic planning and requirements said in a Breaking Defense interview that the program was “on cost, on schedule, and the acquisition program baseline is being met.”28

Given everything we now know about the state of the Sentinel program, these statements were either clear obfuscations or just pure fantasy.

Non-competitive disadvantages

When addressing concerns about the rising projected costs of the Sentinel program, Air Force leaders were confident that a competitive and healthy industrial base would be able to keep the overall price tag down. As Gen. Timothy Ray, then-Commander of Air Force Global Strike Command, told reporters in 2019, “our estimates are in the billions of savings over the lifespan of the weapon.”29

These expected savings clearly never materialized, however, nor did the Pentagon help facilitate the conditions for them to be realized. In March 2018, the Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center submitted a document justifying its intention to restrict competition for the Sentinel contract to just two suppliers—Boeing and Northrop Grumman—stating that this limitation would still constrain costs because the two companies would be in competition with one another.30

However, this specter of competition evaporated when Boeing withdrew from the competition following Northrop Grumman’s acquisition of Orbital ATK—one of two independent producers of large solid rocket motors left in the US market.31 As these motors are necessary to make ICBMs fly, the merger put Northrop Grumman in the driver’s seat: it could restrict access to those motors from Boeing, thus tanking its competitor’s chances at the Sentinel bid.

Doing so would not have been allowed by the terms of the Federal Trade Commission, which permitted the merger in 2018 but subsequently investigated it in 2022 under the Biden administration, and also subsequently blocked a similar attempted merger between Lockheed Martin and Aerojet Rocketdyne that same year.32 However, the Pentagon, which had initially included non-exclusionary and pro-competition language in its requirements for an earlier phase of the Sentinel contract, removed that language from future phases.33 By refusing to wield its own power to preserve competition—initially a key driver for promoting Sentinel over a Minuteman III life-extension—the Air Force essentially left the state of the competition in Northrop Grumman’s hands. According to Boeing’s CEO, Northrop Grumman subsequently slow-walked the process of hammering out a competition arrangement with Boeing—apparently not leaving enough time for Boeing to negotiate a competitive price for solid rocket motors before the Sentinel deadline.34

As a result, Boeing pulled out of the competition altogether, and the Air Force awarded the Sentinel engineering and manufacturing development contract to Northrop Grumman through an unprecedented single-source bidding process. As the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment admitted during 2024 testimony to Congress, what this amounted to was that “effectively there was not, at the end of the day, competition in this program.”35

Reflecting on the Sentinel procurement process, House Armed Services Committee chairman Adam Smith—who has a sizable Boeing presence in his home state of Washington—suggested in October 2019 that the Air Force is “way too close to the contractors they are working with,” and implied that the service was biased towards Northrop Grumman.36

Predictably, the evaporation of competition has coincided with skyrocketing Sentinel acquisition costs. In July 2024, the Air Force’s acquisition chief Andrew Hunter reportedly told reporters that the Air Force was considering reopening parts of the Sentinel contract to bids. “I think there are elements of the ground infrastructure where there may be opportunities for competition that we can add to the acquisition strategy for Sentinel,” Hunter said.37

The Nunn-McCurdy Saga

In January 2024, the Air Force notified Congress that the Sentinel program had incurred a critical breach of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, legislation designed to keep expensive programs in check.38 One week after notifying Congress of the breach, the Air Force fired the head of the Sentinel program, but said the move was “not directly related” to the Nunn-McCurdy breach.39

At the time of the notification, the Air Force stated that the program was 37% over budget and two years behind schedule. Six months later, after conducting the cost reassessment mandated by Nunn-McCurdy, the Pentagon announced that the Sentinel program would cost 81% more than projected and be delayed by several years.40 Nevertheless, the Secretary of Defense certified the program to continue.

Per the requirements of the Nunn-McCurdy Act, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment, who serves as the Milestone Decision Authority for the program, rescinded Sentinel’s Milestone B approval, which is needed for a program to enter the engineering and manufacturing development phase.41 The Air Force must restructure the program to address the root cause of the cost growth before receiving a new milestone approval, a process the service has said will take approximately 18 to 24 months.42

Where Sentinel Stands Now

Work on the Sentinel program has continued while the Air Force carries out the restructuring effort, but the government can’t seem to decide whether things are going well or not.

On February 10, the Air Force told Defense One that parts of the Sentinel program had been “suspended.”43 Due to “evolving” requirements related to Sentinel launch facilities, the Air Force instructed Northrop Grumman to halt “design, testing, and construction work related to the Command & Launch Segment.” There has been no indication of when the stop work order will be lifted. Nevertheless, during an April 10 Air Force town hall on Sentinel in Kimball, Nebraska, Wing Commander of F.E. Warren AFB Col. Johnny Galbert told attendees that Sentinel “is not on hold; it is moving forward.”44

Just under one month after the stop work order was made, the Air Force announced that the Sentinel program had achieved a “modernization milestone” with the successful static fire test of Sentinel’s stage-one solid rocket motor.45 The test marked the successful test firing of each stage of Sentinel’s rocket motor after the second and third stages were tested in 2024.

On March 27, the same day Bloomberg reported that the Air Force was considering a life-extension program for Minuteman III missiles, President Trump’s nominee for Secretary of the Air Force (confirmed by the Senate on May 13), Troy Meinke, committed in his testimony to pushing Sentinel over the finish line, calling the program “foundational to strategic deterrence and defense of the homeland.”46 During the same hearing, Trump’s nominee for undersecretary of Defense for acquisition and sustainment, Michael P. Duffey, also shared his support for the Sentinel program, saying “nuclear modernization is the backbone of our strategic deterrent,” and endorsing Sentinel as “critical.” Yet, two weeks later, on April 9, President Trump signed an executive order to address defense acquisition programs that mandates, “any program more than 15% behind schedule or 15% over cost will be scrutinized for cancellation.”47 This places Sentinel well beyond the threshold for potential cancellation, and the White House fact sheet detailing the order explicitly called out Sentinel’s cost and schedule overruns.

The next day, the Air Force announced that another “key milestone” for the Sentinel program had been met with the stand-up of Detachment 11 at Malmstrom AFB, which will oversee implementation of the Sentinel program at the base.48 But of course, less than thirty days later, Sentinel took a major blow with the Air Force’s admittance that hundreds of new silos would have to be dug up and constructed for the new ICBM.

The Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) latest Weapon Systems Annual Assessment from June 11 reports that Sentinel’s costs “could swell further” as the Air Force “continues to evaluate its options and develop a new schedule as part of restructuring efforts.” The assessment also notes that the Sentinel program alone accounted for over $36 billion of the $49.3 billion increase from 2024 to 2025 in GAO’s combined total estimate of major defense acquisition program costs, and noted that the first flight test now would not take place until March 2028.49 In a sweeping criticism of the program, the GAO report notes that the continued immaturity of the program’s critical technologies more than 4 years into its development phase “calls into question the level of work required to mature these technologies and the validity of the cost estimate used to certify the program.”50

450 Money Pits

We probably will never know how much money could have been saved if the Air Force had elected from the beginning to life-extend the existing ICBMs rather than build an entirely new system from scratch. The opportunity to have a proactive, independent cost comparison and corresponding public debate was eliminated through intense rounds of Pentagon and industry lobbying. But we certainly now know that the Air Force’s assertion—that the Sentinel would be cheaper and easier than a life-extension—was wrong, and that the suppression of an independent review contributed to these rising costs.

The Sentinel saga, with its seemingly unending series of setbacks and continued uncertainties, begs a crucial question: what incentives exist for the Air Force to get it right? That the program, along with numerous other nuclear modernization programs, was green-lighted to continue despite ever-increasing cost and schedule delays exposes a major flaw in U.S. nuclear weapons acquisition programs – they are too big to fail. The government, evidently, will always write a bigger check, will always move the goalposts, because the alternative is either failing to maintain the U.S. strategic deterrent or admitting that U.S. nuclear strategy and force structure is not as immutable and unquestionable as the public has been made to believe. In such a system of blank checks and industry lobbying, what incentivizes the Pentagon to ensure programs are as cost efficient as possible? The only mechanism for oversight and accountability is Congress. Congress must increase oversight of nuclear modernization programs like Sentinel to ensure a limit is placed on how much taxpayer money can be spent on failing programs in the name of national security.

Federation of American Scientists Researchers Contribute Nuclear Weapons Expertise to International SIPRI Yearbook, Out Today

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) launches its annual assessment of the state of armaments, disarmament and international security

Washington, D.C. – June 16, 2025 – Nuclear weapons researchers at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) contributed to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI)’s annual Yearbook, released today. Key findings of SIPRI Yearbook 2025 are that a dangerous new nuclear arms race is emerging at a time when arms control regimes are severely weakened.

“The era of reductions in the number of nuclear weapons in the world, which had lasted since the end of the cold war, is coming to an end,” said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). “Instead, we see a clear trend of growing nuclear arsenals, sharpened nuclear rhetoric and the abandonment of arms control agreements.”

World’s nuclear arsenals being enlarged and upgraded

Nearly all of the nine nuclear-armed states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and Israel—continued intensive nuclear modernization programmes in 2024, upgrading existing weapons and adding newer versions.

Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,241 warheads in January 2025, about 9614 were in military stockpiles for potential use (see the table below). An estimated 3912 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft and the rest were in central storage. Around 2100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the USA, but China may now keep some warheads on missiles during peacetime.

Since the end of the cold war, the gradual dismantlement of retired warheads by Russia and the USA has normally outstripped the deployment of new warheads, resulting in an overall year-on year decrease in the global inventory of nuclear weapons. This trend is likely to be reversed in the coming years, as the pace of dismantlement is slowing, while the deployment of new nuclear weapons is accelerating.

Russia and the USA together possess around 90 per cent of all nuclear weapons. The sizes of their respective military stockpiles (i.e. useable warheads) seem to have stayed relatively stable in 2024 but both states are implementing extensive modernization programmes that could increase the size and diversity of their arsenals in the future. If no new agreement is reached to cap their stockpiles, the number of warheads they deploy on strategic missiles seems likely to increase after the bilateral 2010 Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START) expires in February 2026.

The USA’s comprehensive nuclear modernization programme is progressing but in 2024 faced planning and funding challenges that could delay and significantly increase the cost of the new strategic arsenal. Moreover, the addition of new non-strategic nuclear weapons to the US arsenal will place further stress on the modernization programme.

Russia’s nuclear modernization programme is also facing challenges that in 2024 included a test failure and the further delay of the new Sarmat intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and slower than expected upgrades of other systems. Furthermore, an increase in Russia’s non-strategic nuclear warheads predicted by the USA in 2020 has so far not materialized.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address contemporary challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Develop a Risk Assessment Framework for AI Integration into Nuclear Weapons Command, Control, and Communications Systems

As the United States overhauls nearly every element of its strategic nuclear forces, artificial intelligence is set to play a larger role—initially in early‑warning sensors and decision‑support tools, and likely in other mission areas. Improved detection could strengthen deterrence, but only if accompanying hazards—automation bias, model hallucinations, exploitable software vulnerabilities, and the risk of eroding assured second‑strike capability—are well managed.

To ensure responsible AI integration, the Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear Deterrence, Chemical, and Biological Defense Policy and Programs (OASD (ND-CBD)), the U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Office of the Undersecretary of Defense for Policy (OUSD(P)), and the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), should jointly develop a standardized AI risk-assessment framework guidance document, with implementation led by the Department of Defense’s Chief Digital and Artificial Intelligence Office (CDAO) and STRATCOM. Furthermore, DARPA and CDAO should join the Nuclear Weapons Council to ensure AI-related risks are systematically evaluated alongside traditional nuclear modernization decisions.

Challenge and Opportunity

The United States is replacing or modernizing nearly every component of its strategic nuclear forces, estimated to cost at least $1.7 trillion over the next 30 years. This includes its:

- Intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs)

- Ballistic missile submarines and their submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs)

- Strategic bombers, cruise missiles, and gravity bombs

- Nuclear warhead production and plutonium pit fabrication facilities

Simultaneously, artificial intelligence (AI) capabilities are rapidly advancing and being applied across the national security enterprise, including nuclear weapons stockpile stewardship and some components of command, control, and communications (NC3) systems, which encompass early warning, decision-making, and force deployment components.

The NNSA, responsible for stockpile stewardship, is increasingly integrating AI into its work. This includes using AI for advanced modeling and simulation of nuclear warheads. For example, by creating a digital twin of existing weapons systems to analyze aging and performance issues, as well as using AI to accelerate the lifecycle of nuclear weapons development. Furthermore, NNSA is leading some aspects of the safety testing and systematic evaluations of frontier AI models on behalf of the U.S. government, with a specific focus on assessing nuclear and radiological risk.

Within the NC3 architecture, a complex “system of systems” with over 200 components, simpler forms of AI are already being used in areas including early‑warning sensors, and may be applied to decision‑support tools and other subsystems as confidence and capability grow. General Anthony J. Cotton—who leads STRATCOM, the combatant command that directs America’s global nuclear forces and their command‑and‑control network—told a 2024 conference that STRATCOM is “exploring all possible technologies, techniques, and methods” to modernize NC3. Advanced AI and data‑analytics tools, he said, can sharpen decision‑making, fuse nuclear and conventional operations, speed data‑sharing with allies, and thus strengthen deterrence. General Cotton added that research must also map the cascading risks, emergent behaviors, and unintended pathways that AI could introduce into nuclear decision processes.

Thus, from stockpile stewardship to NC3 systems, AI is likely to be integrated across multiple nuclear capabilities, some potentially stabilizing, others potentially highly destabilizing. For example, on the stabilizing effects, AI could enhance early warning systems by processing large volumes of satellite, radar, and other signals intelligence, thus providing more time to decision-makers. On the destabilizing side, the ability for AI to detect or track other countries’ nuclear forces could be destabilizing, triggering an expansionary arms race if countries doubt the credibility of their second-strike capability. Furthermore, countries may misinterpret each other’s nuclear deterrence doctrines or have no means of verification of human control of their nuclear weapons.

While several public research reports have been conducted on how AI integration into NC3 could upset the balance of strategic stability, less research has focused on the fundamental challenges with AI systems themselves that must be accounted for in any risk framework. Per the National Institute of Standards and Technology’s (NIST) AI Risk Management Framework, several fundamental AI challenges at a technical level must be accounted for in the integration of AI into stockpile stewardship and NC3.

Not all AI applications within the nuclear enterprise carry the same level of risk. For example, using AI to model warhead aging in stockpile stewardship is largely internal to the Department of Energy (DOE) and involves less operational risk. Despite lower risk, there is still potential for an insufficiently secure model to lead to leaked technical data about nuclear weapons.

However, integrating AI into decision support systems or early warning functions within NC3 introduces significantly higher stakes. These systems require time-sensitive, high-consequence judgments, and AI integration in this context raises serious concerns about issues including confabulations, human-AI interactions, and information security:

- Confabulations: A phenomenon in which generative AI systems (GAI) systems generate and confidently present erroneous or false content in response to user inputs, or

prompts. These phenomena are colloquially also referred to as “hallucinations” or “fabrications”, and could have particularly dangerous consequences in high-stakes settings.

- Human-AI Interactions: Due to the complexity and human-like nature of GAI technology, humans may over-rely on GAI systems or may unjustifiably perceive GAI content to be of higher quality than that produced by other sources. This phenomenon is an example of automation bias or excessive deference to automated systems. This deference can lead to a shift from a human making the final decision (“human in the loop”), to a human merely observing AI generated decisions (“human on the loop”). Automation bias therefore risks exacerbating other risks of GAI systems as it can lead to humans maintaining insufficient oversight.

- Information Security: AI expands the cyberattack surface of NC3. Poisoned AI training data and tampered code can embed backdoors, and, once deployed, prompt‑injection or adversarial examples can hijack AI decision tools, distort early‑warning analytics, or leak secret data. The opacity of large AI models can let these exploits spread unnoticed, and as models become more complex, they will be harder to debug.

This is not an exhaustive list of issues with AI systems, however it highlights several key areas that must be managed. A risk framework must account for these distinctions and apply stricter oversight where system failure could have direct consequences for escalation or deterrence credibility. Without such a framework, it will be challenging to harness the benefits AI has to offer.

Plan of Action

Recommendation 1. OASD (ND-CBD), STRATCOM, DARPA, OUSD(P), and NNSA, should develop a standardized risk assessment framework guidance document to evaluate the integration of artificial intelligence into nuclear stockpile stewardship and NC3 systems.

This framework would enable systematic evaluation of risks, including confabulations, human-AI configuration, and information security, across modernization efforts. The framework could assess the extent to which an AI model is prone to confabulations, involving performance evaluations (or “benchmarking”) under a wide range of realistic conditions. While there are public measurements for confabulations, it is essential to evaluate AI systems on data relevant to the deployment circumstances, which could involve highly sensitive military information.

Additionally, the framework could assess human-AI configuration with specific focus on risks from automation bias and the degree of human oversight. For these tests, it is important to put the AI systems in contact with human operators in situations that are as close to real deployment as possible, for example when operators are tired, distracted, or under pressure.

Finally, the framework could include assessments of information security under extreme conditions. This should include simulating comprehensive adversarial attacks (or “red-teaming”) to understand how the AI system and its human operators behave when subject to a range of known attacks on AI systems.

NNSA should be included in this development due to their mission ownership of stockpile stewardship and nuclear safety, and leadership in advanced modeling and simulation capabilities. DARPA should be included due to its role as the cutting edge research and development agency, extensive experience in AI red-teaming, and understanding of the AI vulnerabilities landscape. STRATCOM must be included as the operational commander of NC3 systems, to ensure the framework accounts for real-word needs and escalation risks. OASD (ND-CBD) should be involved given the office’s responsibilities to oversee nuclear modernization and coordinate across the interagency. The OUSD (P) should be included to provide strategic oversight and ensure the risk assessment aligns with broader defense policy objectives and international commitments.

Recommendation 2. CDAO should implement the Risk Assessment Framework with STRATCOM

While NNSA, DARPA, OASD (ND-CBD) and STRATCOM can jointly create the risk assessment framework, CDAO and STRATCOM should serve as the implementation leads for utilizing the framework. Given that the CDAO is already responsible for AI assurance, testing and evaluation, and algorithmic oversight, they would be well-positioned to work with relevant stakeholders to support implementation of the technical assessment. STRATCOM would have the strongest understanding of operational contexts with which to apply the framework. NNSA and DARPA therefore could advise on technical underpinnings with regards to AI of the framework, while the CDAO would prioritize operational governance and compliance, ensuring that there are clear risk assessments completed and understood when considering integration of AI into nuclear-related defense systems.

Recommendation 3. DARPA and CDAO should join the Nuclear Weapons Council

Given their roles in the creation and implementation of the AI risk assessment framework, stakeholders from both DARPA and the CDAO should be incorporated into the Nuclear Weapons Council (NWC), either as full members or attendees to a subcommittee. As the NWC is the interagency body the DOE and the DoD responsible for sustaining and modernizing the U.S. nuclear deterrent, the NWC is responsible for endorsing military requirements, approving trade-offs, and ensuring alignment between DoD delivery systems and NNSA weapons.

As AI capabilities become increasingly embedded in nuclear weapons stewardship, NC3 systems, and broader force modernization, the NWC must be equipped to evaluate associated risks and technological implications. Currently, the NWC is composed of senior officials from the Department of Defense, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Department of Energy, including the NNSA. While these entities bring deep domain expertise in nuclear policy, military operations, and weapons production, the Council lacks additional representation focused on AI.

DARPA’s inclusion would ensure that early-stage technology developments and red-teaming insights are considered upstream in decision-making. Likewise, CDAO’s presence would provide continuity in AI assurance, testing, and digital system governance across operational defense components. Their participation would enhance the Council’s ability to address new categories of risk, such as model confabulation, automation bias, and adversarial manipulation of AI systems, that are not traditionally covered by existing nuclear stakeholders. By incorporating DARPA and CDAO, the NWC would be better positioned to make informed decisions that reflect both traditional nuclear considerations and the rapidly evolving technological landscape that increasingly shapes them.

Conclusion

While AI is likely to be integrated into components of the U.S. nuclear enterprise, without a standardized initial approach to assessing and managing AI-specific risk, including confabulations, automation bias, and novel cybersecurity threats, this integration could undermine an effective deterrent. A risk assessment framework coordinated by OASD (ND-CBD), with STRATCOM, NNSA and DARPA, and implemented with support of the CDAO, could provide a starting point for NWC decisions and assessments of the alignment between DoD delivery system needs, the NNSA stockpile, and NC3 systems.

This memo was written by an AI Safety Policy Entrepreneurship Fellow over the course of a six-month, part-time program that supports individuals in advancing their policy ideas into practice. You can read more policy memos and learn about Policy Entrepreneurship Fellows here.

Yes, NWC subordinate organizations or subcommittees are not codified in Title 10 USC §179, so the NWC has the flexibility to create, merge, or abolish organizations and subcommittees as needed.

Section 1638 of the FY2025 National Defense Authorization Act established a Statement of Policy emphasizing that any use of AI in support of strategic deterrence should not compromise, “the principle of requiring positive human actions in execution of decisions by the President with respect to the employment of nuclear weapons.” However, as this memo describes, AI presents further challenges outside of solely keeping a human in the loop in terms of decision-making.

Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons 2025 Federation of American Scientists Unveils Comprehensive Analysis of Russia’s Nuclear Arsenal

Washington, D.C. – May 6, 2025 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) today released “Nuclear Notebook: Russian Nuclear Weapons 2025,” its authoritative annual survey of Russia’s nuclear weapons arsenal. The FAS Nuclear Notebook is considered the most reliable public source for information on global nuclear arsenals for all nine nuclear-armed states. FAS has played a critical role for almost 80 years to increase transparency and accountability over the world’s nuclear arsenals and to support policies that reduce the numbers and risks of their use.

This year’s report, published in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and by Taylor & Francis and available in full here, discusses the following takeaways:

- Russia currently maintains nearly 5,460 nuclear warheads, with an estimated 1,718 deployed. This represents a slight decrease in total warheads from previous years but still positions Russia as the world’s largest nuclear power alongside the United States.

- Russia continues to modernize its nuclear triad, replacing Soviet-era weapons with newer types, but modernization of ICBMs and strategic bombers has been slow. The country’s efforts to develop the advanced Sarmat (RS-28 or SS-29) ICBM and the next-generation strategic bomber, PAK DA, have faced delays and setbacks.

- The submarine-based nuclear force continues its modernization with Borei-class submarines replacing older types. A portion of Russian ballistic missile submarines are at sea at any given time on strategic deterrent patrols. Significant nuclear warhead and missile storage upgrades are underway at the Pacific and Northern fleet bases.

- Russia continues modernizing and emphasizing its nonstrategic nuclear forces. This includes land- and sea-based dual-capable missiles and tactical aircraft. Despite modernization of launchers, the number of warheads assigned to those launchers has remained relatively stable. Russia held several high-profile exercises with its nonstrategic forces in 2024, and the authors describe upgrades to a suspected nuclear storage depot in Belarus.

- Russia has maintained its policy of nuclear deterrence, emphasizing the strategic importance of its nuclear arsenal in its military doctrine. Updates to public policy documents describe a broader range of scenarios for potential use of nuclear weapons but it is unknown to what extent this is reflected in changes to military plans.

FAS Nuclear Experts and Previous Issues of Nuclear Notebook

The FAS Nuclear Notebook, co-authored by Hans M. Kristensen, Matt Korda, Eliana Johns, and Mackenzie Knight, is published bi-monthly in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The first Nuclear Notebook was published in 1987. FAS, formed in 1945 by the scientists who developed the first U.S. nuclear weapon, has worked since to increase nuclear transparency, reduce nuclear risks, and advocate for responsible reductions of nuclear arsenal and their role.

This latest issue on Russia’s nuclear weapons comes after the release of Nuclear Notebook: Chinese Nuclear Weapons 2025 and will be followed in June by Nuclear Notebook: French Nuclear Weapons 2025. More research available at FAS’s Nuclear Information Project.

The Federation of American Scientists’ work on nuclear transparency would not be possible without generous support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust, the Jubitz Family Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

###

ABOUT FAS