The Aftermath: The Expiration of New START and What It Means For Us All

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

On February 5th, Axios reported that following overnight negotiations between the two sides, there remains a possibility for the two countries to continue observing the central limits after the Treaty’s expiry, although it did not state whether such an arrangement would include verification, and also noted that it had not been agreed to by either President.

If the two sides cannot reach an agreement, we face a world of heightened nuclear competition fueled by worst-case planning and nuclear expansion, fewer transparency mechanisms, and deepening mistrust among nations with the world’s most powerful weapons. Addressing these challenges in the new nuclear era will require creative and nontraditional approaches to risk reduction and arms control.

How did we get here?

Even if the two sides manage to negotiate a last-minute band-aid arrangement, the fact that we have no long-term arms control solution ready to take New START’s place is the culmination of years of breakdown in diplomacy and arms control efforts. New START entered into force on February 5th, 2011, with a 10-year duration and the option to extend it for five additional years. Leading up to the treaty’s original expiration date in 2021, there was serious concern that the United States and Russia would not come to an agreement on extension. For the first three years of his first administration, President Donald Trump engaged in few constructive arms control discussions with Russia. Then, in the final months of 2020, he proposed a short-term extension contingent on Russia agreeing to new verification measures and a warhead freeze, which Russia rejected. At the 11th hour, just two weeks after his inauguration, President Joe Biden agreed to a full five-year extension of the treaty with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The shaky status of New START further deteriorated in early 2023 when Putin announced that Russia was “suspending” its participation in the treaty, stipulating that resumption would require the United States to end its support for Ukraine, and that arms control talks would also have to involve France and the United Kingdom. As part of its suspension, Russia halted its exchanges of data, notifications, and telemetry information, and the United States subsequently followed suit with reciprocal countermeasures.

It is important to note that although the United States found Russia’s actions to constitute noncompliance with the treaty’s requirements, successive State Department reports following Russia’s suspension assessed that “Russia did not engage in any large-scale activity above the Treaty limits.” The 2024 compliance report, however, stated that “Russia was probably close to the deployed warhead limit during much of the year and may have exceeded the deployed warhead limit by a small number during portions of 2024.”

Ultimately, over years of growing tensions and mistrust between the two countries, the United States and Russia have barely managed to see New START through to its expiration, much less engage in talks for a new treaty to take its place. In September 2025, the Kremlin stated that “Russia is prepared to continue observing the treaty’s central quantitative restrictions for one year after February 5, 2026,” without verification. President Trump told a reporter that the proposal “sounds like a good idea to me,” but apparently did not respond to the proposal before the treaty’s deadline expired.

In addition to the worsening U.S.-Russia relationship, funding cuts at the U.S. Department of State, the Defense Nuclear Nonproliferation office at the NNSA, and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence mean less investment in and capacity for executing a follow-on agreement, even if the political environment allowed for it.

What could this mean for nuclear forces?

New START placed limits on the number of strategic nuclear weapons that each country could possess and deploy: each side could deploy up to 1,550 warheads and 700 launchers, and could possess up to 800 deployed and non-deployed launchers. Incorporating a limit on non-deployed launchers was intended to prevent either country from “breaking out” or quickly expanding deployed numbers beyond the treaty limits.

Over the past 15 years, the treaty restraints and respective modernization plans resulted in significant force reductions in Russia and the United States. Both countries have meticulously planned their respective nuclear modernization programs based on the assumption that neither will exceed the force levels currently dictated by New START. In the absence of an official agreement following New START’s expiration, however, both countries will likely default to mutual distrust and worst-case thinking about how their arsenals will grow in the future. This is a serious concern, considering both countries possess significant warhead upload capacity that would allow them to increase their deployed nuclear forces relatively quickly.

This kind of thinking has already been displayed by members of the House Armed Services Committee who, in 2023, called Biden’s agreement to extend New START “naive” and argued that Russia “cannot be trusted,” saying “if these agreements cannot be enforced, then they do nothing to enhance U.S. security, and serve only to undermine it.” Defense hawks in Congress and outside argued instead for upgrades and expansions to the U.S. nuclear force; the bipartisan Congressional Commission on the U.S. Strategic Posture in late-2023 recommended a broad range of options to expand the U.S. nuclear arsenal. The Biden administration also appeared to lay the groundwork for potential options to expand its deployed nuclear force following the end of New START: in June 2024, Pranay Vaddi, Special Assistant to the President and Senior Director for Arms Control, Disarmament, and Nonproliferation at the National Security Council, stated that “Absent a change in the trajectory of adversary arsenals, we may reach a point in the coming years where an increase from current deployed numbers is required. And we need to be fully prepared to execute if the President makes that decision—if he makes that decision.” The Biden administration’s Nuclear Employment Strategy published in 2024, however, did not direct an increase of U.S. deployed nuclear forces, effectively leaving that decision to the Trump administration.

If the United States decided to increase its deployed strategic forces, there are measures it could take to rapidly upload reserve warheads, while other options will take more time. For example, all 400 deployed U.S. ICBMs currently only carry a single warhead, but about half of them use the Mk21A reentry vehicle that could be uploaded to carry three warheads each if necessary. An additional 50 “warm” ICBM silos could also be reloaded with missiles, though this process would likely take several years. With these potential additions in mind, the U.S. ICBM force could possibly double from 400 warheads to up to a maximum of 800 warheads. In any case, executing such an upload across the entirety of the ICBM force would require significant resources, manpower, and time—none of which the United States has in excess, given existing constraints on its already-delayed nuclear modernization program.

Increasing the warhead loading on U.S. ballistic missile submarines could be done faster than uploading the ICBM force. Each missile on the submarines currently carries an average of four or five warheads, a number that can be increased to eight. Doing so could theoretically add 800 to 900 warheads to the submarine force, but loading each missiles with the maximum number of warheads onto each missile (and by extension, each submarine) would dramatically limit the submarine force’s targeting flexibility, as war planners will not want to lock themselves into a situation in which submarine crews would be forced to fire the maximum number of warheads, rather than having a range of more limited options at their disposal. As a result, executing an upload across the submarine force could more realistically result in an increase of approximately 400 to 500 additional warheads. Doing so would take many months, given that each ballistic missile submarine would have to return to port on a rotating schedule in order to load the additional warheads. In addition, the United States has the option to reopen the four launch tubes on each ballistic missile submarine that had been converted to non-nuclear status for New START compliance, and the July 2025 “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” provided $62 million for conversion activities to take place after March 1st, 2026; however, doing so would need to overcome significant internal opposition and would likely take several months, if not years, to complete.

The quickest way for the United States to increase deployed nuclear warheads would be to load nuclear cruise missiles and bombs onto its long-range B-2 and B-52 bombers. The bombers were taken off alert and their nuclear weapons placed in storage in 1992, but hundreds of the weapons are stored at the bomber bases and could be loaded within days or weeks; additional weapons could be brought in from central storage depots. Up to 800 nuclear weapons are estimated to be available for the bombers. Yet loading live nuclear weapons onto bombers would significantly increase the vulnerability of the weapons to accidents and terrorist attacks.

Russia also has a significant warhead upload capacity, particularly for its ICBMs, but is subject to similar constraints as the United States. Several of Russia’s existing ICBMs are thought to have been downloaded to a smaller number of warheads than their maximum capacities in order to meet the New START force limits. As a result, without the limits imposed by New START, Russia’s ICBM force could potentially increase by approximately 400 warheads.

Warheads on missiles onboard some of Russia’s SSBNs are also thought to have been reduced to a lower number to meet New START limits. Without treaty limitations, the number of deployed warheads could potentially be increased by 200-300 warheads, perhaps more in the future, although this number could be tempered by a desire for increased targeting flexibility, in a similar manner to the United States.

While also uncertain, Russian bombers could be loaded relatively quickly with hundreds of nuclear weapons, similarly to the United States.

Ultimately, if both countries chose to upload their delivery systems to accommodate the maximum number of possible warheads, both sets of arsenals could nearly double in size. While a maximum upload is highly unlikely, it is possible we will see immediate measures taken to upload certain systems, followed by gradual increases in other areas over the next few years. While defense hawks in Russia and the United States claim that more nuclear weapons are needed for national security, doing so would inevitably result in each country being targeted by hundreds of additional nuclear weapons.

Moreover, without the transparency and predictability that resulted from the verification regime and regular data exchanges stipulated under New START, nuclear uncertainty—and potentially confusion and misunderstandings—will increase. Russian and U.S. planners will rely more on worst-case scenarios in their nuclear programs, and both countries are likely to invest more in what they perceive will demonstrate resolve and increase their overall security, including nonstrategic nuclear forces, conventional forces, cyber and AI capabilities, and missile defense. These moves could also trigger reactions in other nuclear-armed states, possibly leading to an increase in their nuclear forces and the role they play in their military strategies. China has already decided to increase its nuclear arsenal to better be able to counter what it perceives is a growing threat from other military powers; Beijing rejects numerical limits on its nuclear arsenal and increasing U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenal will make it harder to change its mind.

Re-imagining the future: The end of fully “compartmentalized” arms control?

The future of arms control is certainly not dead, but it is likely entering a new era. For decades, the United States and Russia pursued arms control negotiations in isolation from other security issues, emphasizing that the unique destructiveness of nuclear weapons requires that the topic be segregated. Although such negotiations were never completely disentangled from politics or other geopolitical events—as demonstrated, for example, by the refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify SALT II after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan—this approach was largely successful as a framework for arms control during and immediately after the Cold War.

This fully compartmentalized approach, however, is likely no longer an option in a post-New START world. Russia has made it clear through both its actions—particularly its suspension of its treaty obligations primarily due to U.S. support for Ukraine—and its rhetoric that it will no longer engage in arms control negotiations absent a broader reboot of U.S.-Russia relations. And officials in the United States increasingly argue that bilateral nuclear limits on U.S. and Russian nuclear arsenals do not take into account the growing Chinese nuclear arsenal.

On February 3rd, Deputy Foreign Minister Ryabkov stated that in order to engage in strategic stability dialogue, “We need far-reaching shifts, changes for the better in the US approach to relations with us as a whole.” On numerous prior occasions, he had critiqued the United States’ approach to arms control: in 2023, he told TASS that Moscow cannot “discuss arms control issues in the mode of so-called compartmentalization, which means singling out from the whole range of issues some pressing ones which are of interest to the United States, and pushing to oblivion or taking off the table other points that are theoretically as important to Russia as those of interest to the Americans.”

It would appear that China thinks about arms control in a similar way. In 2024, China suspended strategic stability talks with the United States in response to U.S. arms sales to Taiwan and increased trade restrictions on China. A spokesperson from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs emphasized that in order to bring China to the table, the United States “must respect China’s core interests and create [the] necessary conditions for dialogue and exchange.” On February 5th, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Lin Jian reiterated that “China’s nuclear strength is by no means at the same level with that of the U.S. or Russia. Thus, China will not take part in nuclear disarmament negotiations for the time-being.” Even if it were possible to change China’s opposition to numerical limits on nuclear forces and join the arms control process, it is not clear what the United States would actually be willing to limit or give up in return for Chinese concessions. One such possibility would be the more ambitious and fantastical elements of Golden Dome, as a multi-layered, space-based missile shield is fundamentally incompatible with the idea of accepted mutual vulnerability.

Re-imagining the future: verification without on-site inspections?

Traditional nuclear arms control, including New START, relies on the availability of on-site inspections to verify compliance. Absent a significant shift in geopolitical relations, however, it is implausible to imagine some combination of American, Russian, or Chinese inspectors roaming around each other’s territories anytime in the near future. As a result, the next generation of arms control agreements faces a clear challenge: how can countries verify that the other remains in compliance when the political reality prohibits on-site inspections?

Traditionally, countries have used “National Technical Means”—a term used to describe classified means of data collection, such as remote sensing and telemetry intelligence—to verify compliance with arms control agreements. NTMs are used as a complement to other sources of verification, including on-site inspections, data exchanges and notifications, and the exchange of telemetric information. Despite on-site inspections and formal data exchange being preferable, NTMs can be very capable; for example, the U.S. assessment that Russia might briefly have exceeded the New START warhead limit was based on NTMs, not on-site verification.

Given the political implausibility of on-site inspections forming part of a future verification regime, one of the authors has recently co-authored a report with Igor Morić from Princeton’s Science & Global Security Program on the possibility of a future arms control arrangement based around “Cooperative Technical Means.” Under such an arrangement, it could be possible for states to use national or commercial remote sensing tools to monitor each other’s nuclear capabilities, verify the numbers of fixed and mobile ICBM and SLBM launchers, as well as track the number and location of their heavy bombers. For a more detailed explanation, the full report can be accessed here.

What Now?

As Axios’ reporting indicates, everything could change in a day, for better or for worse. Countries could take unilateral measures to either exercise restraint or refuse cooperation. Specifically, it is important that each side refrain from significant increases in its nuclear arsenal regardless of whether a new arrangement is concluded; such steps will almost inevitably increase the competition dynamic that would result in an arms race.

It is also imperative that the United States and Russia commit to engaging in arms control as a means of reducing the risk of nuclear use, whether intentional or by accident or misinterpretation. The United States, in particular, should reinvest in and reprioritize diplomacy and nonproliferation to prepare for and signal an intention to re-engage in arms control dialogues.

While new technology and creative approaches offer potential solutions to issues plaguing past arms control arrangements, progress will still require political will and motivation from both sides.

Here at FAS, we will continue to track the nuclear force status and modernization programs across the nine nuclear-armed states, paying close attention to cost and schedule overruns that relentlessly plague many of these efforts. In an era where nuclear transparency and access to reliable, public information are declining, we believe our work is more critical now than ever before.

Additional work from us on this topic:

- After Seven Years of Implementation, New START Treaty Enters Into Effect

- If Arms Control Collapses, US and Russian Strategic Nuclear Arsenals Could Double In Size

- Inspections Without Inspectors: A Path Forward for Nuclear Arms Control Verification with “Cooperative Technical Means”

- The Long View: Strategic Arms Control After the New START Treaty

- 2025 Russia Nuclear Notebook

- 2025 United States Nuclear Notebook

- For all Nuclear Notebooks, see here

The Nuclear Information Project is currently supported with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

The Pentagon’s (Slimmed Down) 2025 China Military Power Report

On Tuesday, December 23rd, the Department of Defense released its annual congressionally-mandated report on China’s military developments, also known as the “China Military Power Report,” or “CMPR.” The report is typically a valuable injection of information into the open source landscape, and represents a useful barometer for how the Pentagon assesses both the intentions and capabilities of its nuclear-armed competitor.

This year’s report, and particularly the nuclear section, is noticeably slimmed down relative to previous years; however, this is because the format of the report has changed to focus on newer information, rather than repeating and reaffirming older assessments. As a result, this year’s report includes no mention of China’s ballistic missile submarines and their associated missiles, and includes only cursory mention of China’s air-based nuclear capabilities. It also excludes analyses of several types of land-based missiles entirely. However, this does not reflect changed assessments on the part of the Pentagon, but rather a lack of new information to report. Going forward, this means that analysts will need to read multiple years of CMPR reports in order to ensure that they are accessing the complete range of available information.

In addition, this year’s CMPR did not include any mention of China’s September 2025 Victory Day parade––which featured multiple new weapon systems––as the parade took place too recently; it will very likely be analyzed in next year’s report. The maps of missile base and brigade locations also appear to be out of date: the information is listed as “current as of 04/01/2024.”

While this year’s report did not include any earth-shattering headlines with regards to China’s nuclear forces, it provides additional context and useful perspectives on various events that took place over the past 12 months.

Stockpile growth

The CMPR states that China’s nuclear stockpile “remained in the low 600s through 2024, reflecting a slower rate of production when compared to previous years.” However, it reaffirmed previous years’ assessments that China “remains on track to have over 1,000 warheads by 2030.” China’s nuclear expansion over the past five years is now making this projection increasingly plausible, although even if it came to pass, China would still maintain several thousand warheads fewer than either the United States or Russia. Previous CMPRs had assessed that if China’s modernization pace continued, it would likely field a stockpile of about 1,500 warheads by 2035; however, this assessment has not been included in the CMPR since the 2022 iteration.

The dramatic expansion of China’s stockpile is primarily being prompted by the large-scale development and modernization of China’s next-generation intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) forces. In 2021, multiple non-governmental organizations (including our team at the Federation of American Scientists) publicly revealed the existence of three new ICBM silo fields capable of hosting up to 320 launchers for solid-propellant DF-31 class ICBMs. China is also more than doubling its number of silos for its liquid-fuel DF-5 class ICBMs, which the Pentagon assessed in its 2024 CMPR will likely yield about 50 modernized silos. Many of these missile types will be capable of carrying multiple warheads.

While the previous year’s CMPR indicated that China “has loaded at least some ICBMs into these silos,” the 2025 edition offers a valuable update: that China has now “likely loaded more than 100 solid-propellant ICBM missile silos at its three silo fields with DF-31 class ICBMs.” Our team continues to regularly monitor developments at the three silo fields using commercial satellite imagery and has not yet found sufficient evidence to corroborate this assessment; however, it is possible that the Pentagon’s assessment is primarily derived from other sources of intelligence, including human (HUMINT) and/or signals intelligence (SIGINT).

If China plans to continue its nuclear expansion, it will likely require additional fissile material, as China does not currently have the ability to produce large quantities of plutonium. The Pentagon assesses that China’s ongoing construction and planned commissioning of two new CFR-600 sodium-cooled fast breeder reactors at Xiapu “will reestablish China’s ability to produce weapons-grade plutonium.” However, the 2025 CMPR assesses that the first unit “is probably still undergoing testing,” and that “the second reactor unit is still under construction.” It is possible that this information is now out of date, as recent commercial satellite imagery now suggests that the first reactor unit may be operational.

Low-yield warheads

Previous editions of the CMPR had indicated that China was “probably” seeking low-yield warheads for escalation control during periods of small-scale nuclear crisis and/or conflict; however, the 2025 iteration is the first to offer an estimated yield value for such weapons, of “below 10 kilotons.” A recent technical history by Hui Zhang offers highly valuable data points for historical Chinese nuclear weapons tests, and suggests that China likely has the ability to produce smaller, low-yield warheads. Additionally, recent open-source reporting by Renny Babiarz with Open Nuclear Network (ONN) and researchers from the Verification Research Training and Information Center (VERTIC) found that China has been overhauling and expanding its warhead component manufacturing capabilities. Coupled with the expansion of the Lop Nur test site, this could indicate plans to upgrade China’s existing warheads, improve its ability to build more, or both.

The CMPR notes that the DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) and the air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) carried by the H-6N bomber “are both highly precise theater weapons that would be well suited for delivering a low-yield nuclear weapon.” While the DF-26 had previously been identified as a likely carrier for a low-yield warhead, this is the first time that the H-6N’s ALBM has also been listed as a potential carrier.

Missile designations

It is often a complex endeavor to try and match China’s own missile designations to the names that are given to various systems by the Pentagon. This year’s CMPR, however, provides valuable confirmations for some of these missile designations. In particular, it confirms that both the DF-31A and DF-31AG ICBM are known to the Pentagon as CSS-10 Mod 2, which aligns with our understanding that both systems carry the same missile. It also strongly hints at the alignment between the CSS-18 and the DF-26 IRBM, as well as the CSS-10 Mod 3 and the DF-31B ICBM––a missile that was confirmed in the 2025 CMPR as the same missile that was launched from Hainan Island into the Pacific Ocean in September 2024 for the first time since 1980. This was the first mention of the DF-31B in the CMPR since the 2022 edition, and the first time that the missile’s existence under that designation has been confirmed.

The acknowledgement of the DF-31B’s existence coincides with the recent reveal of a likely silo-based version of the same missile during China’s September 2025 military parade. During that event, China unveiled a vehicle carrying a canister with the designation “DF-31BJ;” it is possible that the vehicle was a missile loader and the “J” likely indicates a silo basing mode, as the Chinese character “井” or “jing” means “well” and is used by the PLA to describe silos. We can therefore assume that the DF-31B ICBM has both a mobile and a silo basing mode, with the latter adding the J suffix to its designation.

Doctrinal shifts, arms control, and early warning

Beyond tweaks to China’s force posture and nuclear stockpile, the CMPR also offers some additional details with regards to its assessment of China’s nuclear doctrine. In particular, it expands on its previous assessments of China’s pursuit of an “early warning counterstrike (EWCS) capability,” which it calls “similar to launch on warning (LOW), where warning of a missile strike enables a counterstrike launch before an enemy first strike can detonate.” For the first time, the CMPR offers details into the capabilities of China’s early warning systems, stating that “China’s early warning infrared satellites [Tongxun Jishu Shiyan (TJS), also known as Huoyan-1] can reportedly detect an incoming ICBM within 90 seconds of launch with an early warning alert sent to a command center within three to four minutes.”

It also notes that China’s ground-based, large phased-array radars “probably can corroborate incoming missile alerts first detected by the TJS/Huoyan-1 and provide additional data, with the flow of early warning information probably enabling a command authority to launch a counterstrike before inbound detonation.” If this is accurate, it would appear that China is developing an early warning capability that functions in a similar manner to those of the United States and Russia, which rely on dual phenomenology to confirm the validity of incoming attacks before authorizing retaliatory launches.

The report also notes that “Beijing continues to demonstrate no appetite for pursuing […] more comprehensive arms control discussions,” including those related to a potential US-China bilateral missile launch notification mechanism.

Corruption

The CMPR focuses quite a bit on China’s ongoing measures to combat corruption, which has led to the removal of dozens of senior officials from their posts across the PLA Air Force, Navy, and Rocket Force. The report notes that “[c]orruption in defense procurement has contributed to observed instances of capability shortfalls, such as malfunctioning lids installed on missile silos”––a story which Bloomberg first reported in January 2024. The report notes that “these investigations very likely risk short term disruptions in the operational effectiveness of the PLA.”

Missiles and delivery systems

The 2025 report included a detail that in December 2024, “the PLA launched several ICBMs in quick succession from a training center into Western China.” Contrary to the launch from Hainan Island, there was very little public reporting about this salvo launch.

The CMPR also indicates an estimated growth in China’s ICBM and IRBM launchers by 50 each, although it is unclear whether these numbers include both finished launchers as well as those still under construction.

The following graph indicates the growth of China’s launchers and missiles, as assessed by the Pentagon, over the past 20 years. It is important to note that many of these missiles, including China’s short- and medium-range ballistic missiles and its ground-launched cruise missiles (GLCMs), are not nuclear-capable.

Our 2025 overview of China’s nuclear arsenal can be freely accessed here.

The Nuclear Information Project is currently supported with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

On the Precipice: Artificial Intelligence and the Climb to Modernize Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications

The United States’ nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) system remains a foundational pillar of national security, ensuring credible nuclear deterrence under the most extreme conditions. Yet as the United States embarks on long-overdue NC3 modernization, this effort has received less scholarly and policy attention than the modernization of nuclear delivery systems. This paper addresses that gap by providing a critical assessment of the U.S. NC3 enterprise and its evolving role in a rapidly transforming strategic environment.

Geopolitically, U.S. NC3 modernization must now contend with issues including China’s rise as a nuclear near peer, Russia’s deployment of increasingly threatening hypersonic and counterspace capabilities, and the erosion of norms restraining limited nuclear use.

Technologically, the shift from legacy analog to digital architectures introduces both great opportunities for enhanced speed and resilience and unprecedented vulnerabilities across cyber, space, and electronic domains.

Bureaucratically, modernization efforts face challenges from fragmented acquisition responsibilities and the need to align with broader initiatives such as Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control (CJADC2) and the deployment of hybrid space architectures.

This paper argues that successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability. The study evaluates the key systems, organizational challenges, and operational dynamics shaping U.S. NC3 and offers policy recommendations to strengthen deterrence credibility in an era of accelerating geopolitical and technological change.

Read the complete publication here.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

What’s New for Nukes in the New NDAA?

At the time of publication, the NDAA had passed both chambers of Congress but had not yet been signed by the president. The Act, S. 1071, was signed into law on December 18.

Congress’ new annual defense spending package, passed on December 17, authorizes $8 billion more than the Trump administration requested, for a total of $901 billion. The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them. Below is an overview of provisions of note in the new NDAA related to nuclear weapons.

Sentinel / Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles

Every year since fiscal year (FY) 2017, Congress has inserted language into the NDAA prohibiting the Air Force from deploying fewer than 400 ICBMs (an arbitrary requirement put in place by pro-ICBM members of Congress fearful of any reductions in the force). The FY26 NDAA does not break this streak; in fact, it entrenches the requirement deeper into US policy. Rather than repeating the minimum ICBM requirement as a simple provision as previous NDAAs have done, Section 1632 of the new legislation inserts the requirement into Title 10 of the United States Code (the US Code is the official codification by subject matter of the general and permanent federal laws of the United States. Title 10 of the Code is the subset of laws related to the Armed Forces). This change means that Congress will no longer have to agree to and insert the requirement into the NDAA year after year. Instead, the requirement becomes the permanent standard and will require an affirmative change in a future NDAA to undo. Beyond requiring the Air Force to deploy at least 400 ICBMs, the new defense spending act additionally amends Title 10 of US Code to prohibit the Air Force from maintaining fewer than the current number of 450 ICBM launch facilities (essentially meaning that the Air Force cannot decommission any of the 50 extra launch facilities in the US inventory).

This change is indicative of a desire by Congress to bolster its protection of the ICBM program in response to increased scrutiny prompted by the ever-growing budgetary and programmatic failures of the Sentinel ICBM program. Interestingly, a provision in the Senate version of the defense authorization bill that would have established an initial operational capability (IOC) date for the Sentinel program of September 30, 2033, did not make it into the final text, suggesting a lack of confidence in the Air Force’s ability to achieve the milestone. With an original IOC of September 2030, the September 2033 date would have aligned with the Pentagon’s 2024 announcement that the Sentinel program was delayed by at least three years. The omission may thus indicate Congress’ anticipation of potential further delays to Sentinel’s schedule beyond the Air Force’s most recent estimate.

Nuclear Armed Sea-Launched Cruise Missile (SLCM-N)

In addition to protecting the most politically vulnerable nuclear weapons programs, the FY26 NDAA also aims to speed up US nuclear modernization and development, in some cases even beyond the requests of the administration. Despite the fact that the Pentagon’s FY26 budget request requested no discretionary funding for the nuclear-armed, sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N), the NDAA authorized $210 million for the program — on top of the $2 billion to the Department of Defense and $400 million to the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) included in the July 2025 reconciliation package to “accelerate the development, procurement, and integration” of the SLCM-N missile and warhead, respectively.

Most notably, the new defense authorization act speeds up the SLCM-N’s deployment timeline by two years. Section 1633 of the act repeats the IOC date of September 30, 2034, established by the FY24 NDAA, but also requires DOD to deliver a certain number of SLCM-N — a number to be determined by the Nuclear Weapons Council — by September 30, 2032, to achieve “limited operational deployment” prior to IOC.

Future nuclear development

In addition to speeding up the deployment timeline for SLCM-N, the FY26 NDAA initiates and accelerates the development of new nuclear weapons by creating a new NNSA program in addition to the stockpile stewardship and stockpile responsiveness programs: the rapid capabilities program. The new program — established by section 3113 of the NDAA via insertion into Title 50 of the US Code (War and National Defense) — is tasked with developing new and/or modified nuclear weapons on an accelerated, five-year timeline (compared to the traditional 10-15 year timeline for new weapons programs) to meet military and deterrence requirements.

Numerous provisions in the new NDAA reflect a lack of trust by Congress in DOD and DOE’s ability to execute and deliver nuclear modernization programs. The creation of stricter and more detailed reporting requirements and action items for making progress on various nuclear weapons related programs constitute an increased effort by Congress to micromanage nuclear modernization programs.

One example of nuclear micromanagement in the act are Sections 150-151 regarding the B–21 bomber. Section 150 mandates the Air Force to submit to Congress:

- An annual report on the new B–21 nuclear bomber including:

- An estimate for the program’s average procurement unit cost, acquisition unit cost, and life-cycle costs,

- “A matrix that identifies, in six-month increments, plans for and progress in achieving key milestones and events, and specific performance metric goals and actuals for the development, production, and sustainment of the B–21 bomber aircraft program” (with detailed requirements for how the matrix should be subdivided and what information it must include),

- A cost matrix (also in six-month increments and including specified subdivisions),

- A semiannual update on the aforementioned matrices.

In addition, the provision requires the US Comptroller General to “review the sufficiency” of the Air Force’s report and submit an assessment to Congress. The following section of the NDAA additionally requires the Air Force to submit to Congress — within 180 days of the act’s enactment — “a comprehensive roadmap detailing the planned force structure, basing, modernization, and transition strategy for the bomber aircraft fleet of the Air Force through fiscal year 2040” (once again, including detailed requirements for what information the roadmap must include).

In a similar fashion, Sections 1641 and 1652 lay out strict reporting and planning requirements for sustaining the Minuteman III ICBM force and developing the Golden Dome ballistic missile defense program, respectively.

Such efforts by Congress to increase its management of US nuclear weapons programs could be in response to repeated and ongoing delays, cost overruns, and setbacks, or could simply reflect Congress’ desire to seize more control over the nuclear enterprise to get what it wants (or, likely, a bit of both). To be clear, Congressional scrutiny into nuclear programs is welcome amidst a trend of over-budget and behind-schedule procurement of unnecessary weapon systems by the Pentagon. Congress can and should play an important role in ensuring that the Departments of Defense and Energy are not handed blank checks for nuclear modernization.

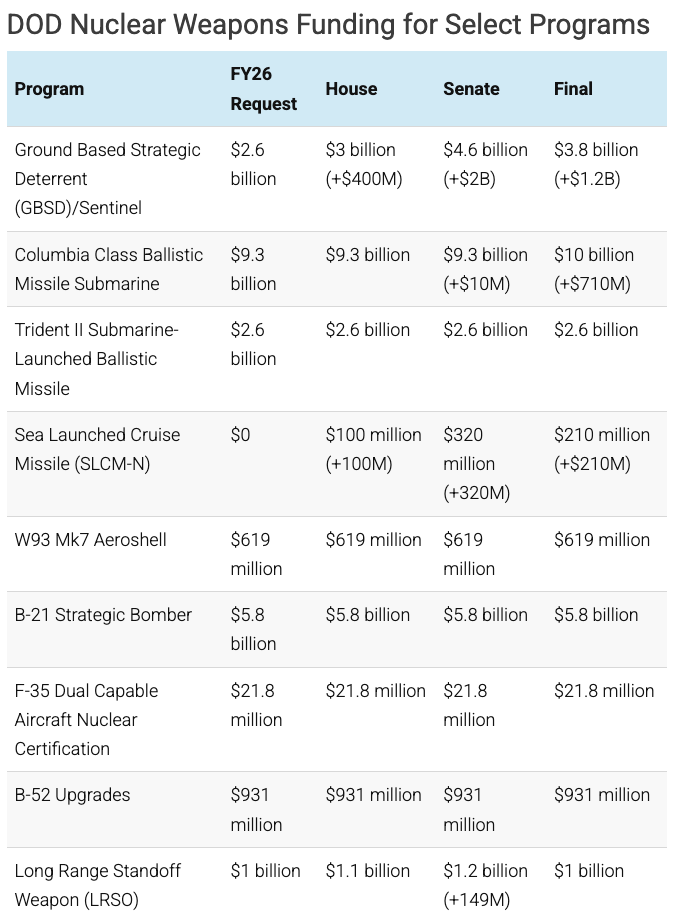

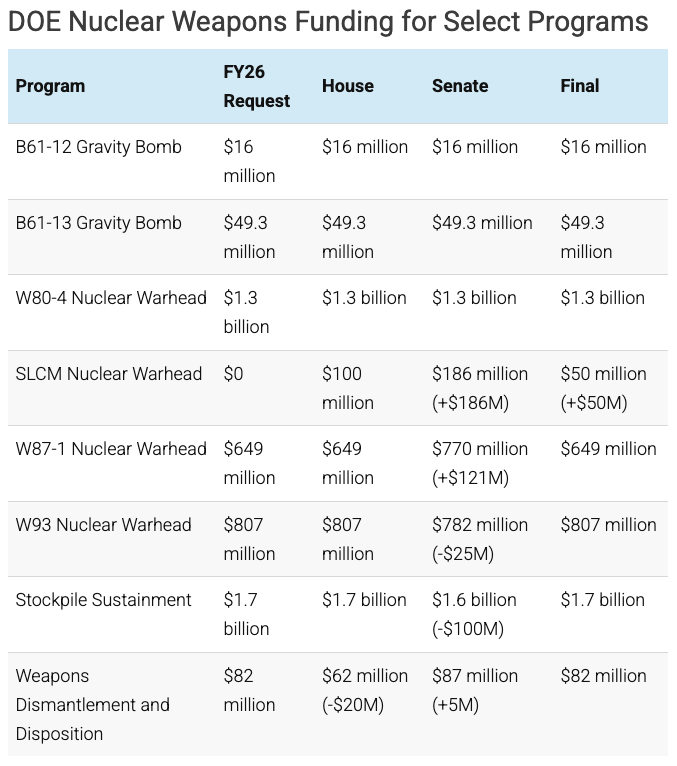

That said, with this legislation, Congress authorized nearly $30 billion in spending for select nuclear weapons programs in FY26 alone. The tables below, developed by the Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation, show a breakdown of Congress’ authorizations for these programs:

This article was researched and written with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, and individual donors.

Tracking the DF Express: A Practical Guide to Evaluating Chinese Media and Public Data for Studying Nuclear Forces

Observers of Chinese nuclear politics and force posture are old friends with information challenges. Open-source analysts of China’s nuclear force drew heavily on published Chinese-language writings, footage, and interviews by official Chinese media or private Chinese citizens, as well as commercial satellite imagery. These powerful open-source tools enable scholars to gain insight into some of the Chinese government’s most closely guarded secrets, such as the construction of 119 nuclear missile silos. Reports from well-regarded institutions, such as the PLA Rocket Force Order of Battle report by the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, offer open-source research that provides concrete data on the Chinese nuclear force, using thoroughly analyzed imagery and Chinese-language materials. Other studies, such as several reports by the RAND Corporation and the Air University’s China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), extensively used Chinese military and technical writings to identify patterns in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA)’s strategic thinking in its own words. Combined with the Federation of American Scientists (FAS)’s annual report on nuclear forces, there is a growing and vibrant open-source intellectual community on the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF).

While researchers continue to dissect new information from China, obtaining reliable data has become increasingly difficult for two reasons. First, the Chinese government has curtailed foreign access to sources like academic databases that were previously fair game for scholarly use, complicating the already dense “information fog” over China’s political and military apparatus. Second, unverified, digitally altered, and AI-generated disinformation and misinformation are commonplace on popular social media platforms like X (formerly Twitter). Combined with the multitude of Chinese social media and video websites, weeding out the noise and distraction has become an increasingly challenging task for new researchers in this field.

This essay provides introductory guidance on the usefulness of Chinese social media and video platforms for observers and researchers of China’s nuclear force. This guide may assist researchers in identifying what to look for and on which platform, especially for those who are not advanced or native speakers of Mandarin. In the sections below, I compare a set of popular Chinese social media platforms and discuss the usefulness of each with respect to open-source study of the Chinese nuclear force. I also present a brief glossary of nicknames and vernacular terms related to nuclear matters in Mandarin, along with their translations. I conclude with a brief discussion of the use of AI-enabled translation tools for open-source research on the PLA.

Chinese media and OSINT: What’s good for what?

Sina Weibo (新浪微博)

Weibo is useful for providing timely, authoritative, and chronologically documented information on training exercises, operations, and policy changes that are of propaganda or morale-promoting value. The equivalent of X in China, Weibo is the biggest Chinese-language social media with over 500 million monthly active users as of 2024. It is likely the most influential social media platform in China, as indicated by the vast number of users and a highly agile and effective censorship system. Due to Weibo’s ability to rapidly disseminate information, all major state and military organs, including the PLA Daily, the Ministry of Defense, individual service branches, and all five PLA Theater Commands (战区), maintain official accounts on Weibo (Figure 1). These accounts are directly managed by dedicated propaganda or public affairs teams and authorized to post military content, which sometimes features approved footage and photos of training exercises. Details revealed in the footage or pictures may help researchers identify the unit leadership and the weapon systems used during the exercise. Additionally, Weibo is often the first platform to announce state media PLA news. The People’s Daily, CCTV, and the Xinhua Agency regularly post links to news articles and updates on Weibo to facilitate dissemination.

For researchers, Weibo contains a reasonably reliable search system. Researchers may use the Weibo search bar to look for mentions of “strategic deterrence,” “nuclear force,” or names of nuclear missiles and use the filter function to screen for content released by official accounts. For well-publicized events like a missile exercise, the topic may be included in the trending (热搜) section for real-time updates. However, a significant limitation of Weibo is that scholars must distinguish whether the content posted by the official accounts directly reflects the Party’s policy or simply shows a lower-level interpretation of the policy by individual units. These official accounts are likely managed by young, tech-savvy officers or civilian employees trained in public affairs.

Sometimes, these individuals might improvise and go beyond what they were prescribed. Some more active accounts, such as the Eastern Theater Command official account, have interacted with random Weibo users in the past and have eagerly implied their belligerent stance toward Taiwan. This led many Chinese netizens to interpret the official account’s posts as a sign of imminent military action, which thankfully was not the intention. Additionally, state-run accounts have also taken down content (primarily propaganda material) for reasons other than revealing unapproved or sensitive information. Again, since the accounts are likely managed by younger personnel at the lower level, contents could be removed when it was later found to be too politically sensitive or too unpersuasive. In 2019, the People’s Liberation Army Army (PLAA) official account posted a propaganda article on Weibo aimed at inspiring nationalistic fervor. It quoted a passionate patriotic poem written by Wang Jingwei (汪精卫), whom the Chinese government considered a “traitor (汉奸)” for cooperating with the Imperial Japanese invaders, most likely because the editor had known about the poem but not its authorship. The comment section quickly pointed out this “political mistake (政治错误)”, leading to the content’s prompt removal. As such, researchers should be aware that removed content does not necessarily suggest valuable information worth hiding.

It is also important to note that accessing Weibo sometimes involves more than typing in the URL. Aside from the content available on the front page (e.g., the trending section), the rich content of the platform is only accessible after logging in. One does not need a mainland Chinese phone number to create an account on Weibo. A virtual number from a trusted provider is also sufficient. Even without an account, researchers could still access the Weibo homepage of many accounts by searching the account’s name in a search engine (for instance, here is the direct link to the official PLA Eastern Theater Weibo page). However, Sina Weibo’s search bar will not be available for unregistered users.

CCTV.com (央视网)

CCTV.com is a webpage that gives scholars access to the state media’s TV programs without a registered account. In addition to live-streamed news stories, the webpage also serves as a large but incomplete archive of past TV programs. CCTV.com has high-definition PLA video footage and interviews, which may be particularly useful for open-source analysis. Some of the CASI reports made clever use of video footage released by Chinese state media to identify key information regarding training exercises and unit deployment, particularly the CCTV-7 channel dedicated to military content. Other open-source intelligence analysts were able to map out key personnel, location, and weapon system information from CCTV news broadcasts and military TV programs. The search bar supports keyword searches and includes government-sponsored TV programs from various channels. The search also returns results from CCTV webpages and the Xinhua Agency. This is the most useful for finding information related to specific missile systems. For instance, among the top results for “DF-26” include footage of a DF-26 missile from a documentary (Figure 2). The search result for “dual-capability” also returned a video by a Chinese military commentator who states that China’s hypersonic vehicle is dual-capable (Figure 3). For open-source analysis, having the ability to revisit footage that might contain useful information on the PLARF is a major advantage of this platform. At the same time, the search function is limited to the titles of the program, not necessarily the content. Furthermore, many of the videos available on CCTV.com are commentaries from Chinese military experts. While the commentary from the Chinese experts may be useful, the visual component may not always be the latest developments. Because of the length requirement of the TV program, the visual element may only have looped videos of known weapon testing or parade footage. Researchers may consider comparing the footage from different programs to remove the repeated material.

Bilibili (哔哩哔哩), Douyin (抖音), Kuaishou (快手)

Bilibili, Douyin, and Kuaishou are among the most used entertainment video-sharing and short-video platforms in China. Bilibili is a video service primarily for animation, comics, and games (ACG) content. It has a “bullet comment (弹幕)” function that allows users to inject text over the video content in real time. The platform attracts over 100 million daily users as of 2024. Douyin (the Chinese mainland version of TikTok) and Kuaishou are short-video platforms with a significantly larger user base than Bilibili, with Douyin content reaching over 1 billion active users monthly. Unsurprisingly, the PLA, the individual Theater Commands, and the Chinese government and Party organs maintain an active presence on these platforms for propaganda, news updates, and publicity programs, often repeating the same message sent across other outlets.

However, despite these platforms’ popularity, they are not great resources for open-source nuclear force research for two reasons. First, there is overwhelming noise from private click-farming content creators who would grossly overstate or fabricate China’s military capabilities to profit from nationalistic sentiments. A researcher may find many videos speculating about the capabilities of the H-20 bomber with no credible source to back up the claims. Private content creators typically have no privileged access to information. In the rare cases where some villagers filmed a rocket booster falling from the sky (some Chinese rocket boosters in the past landed in populated villages), the video is often quickly censored on these closely watched platforms. Second, official government accounts on these platforms almost always repeat information that has been released on Weibo and other traditional news platforms. Some Party organs, such as the Communist Youth League (共青团), which pushes propaganda to the younger generation, would convey the same approved message using CGI videos to boost nationalist sentiment, but the content itself is no more useful than reading the official news release. Overall, there is little added advantage of using the entertainment-based services for potentially useful open-source information.

Combining Sources

While Chinese video and social media platforms could assist OSINT research on China’s nuclear forces, researchers could also combine the visual element of weapon systems with textual data gathered from authoritative Chinese platforms like China Military Online (中国军网), PLA Procurement website (军队采购网), and Qi Cha Cha (企查查). The visual data can help identify many technical aspects of the PLA’s nuclear weapons, but the textual information can greatly inform the acquisition, production, and deployment of the weapon and support systems. Provinces with robust military and heavy industries, such as Heilongjiang, Liaoning, Shandong, and Shaanxi, sometimes release contracting and procurement information locally on provincial and municipal government websites. The information found on local government websites is admittedly sporadic, making broad, systematic collection difficult. Still, such information could serve as valuable first-hand sources for OSINT researchers. For more technical analysis of weapon systems, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (中国国家知识产权局) has a patent database that could be useful to track the development and ownership of certain enabling technologies for nuclear systems. This may be further enhanced by using the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (中国知网CNKI) to locate academic articles on the relevant technology, though access to CNKI articles usually requires an institutional subscription through a university library. Note that many of the Chinese government and military websites do not support a secure HTTPS connection. Some, like Qi Cha Cha, may require the user to access its content from a Chinese mainland IP address. Researchers should deploy cybersecurity tools to take full advantage of these resources.

Nicknames and Vernacular

In addition to the advantages and limitations of different social media platforms, researchers should be aware of the common nicknames and vernacular related to the Chinese nuclear force. Much like how the F-16 is commonly called “viper” instead of the official name “fighting falcon,” there are also nicknames for weapons and systems in the PLA. The table below summarizes several common terms and explains their meaning and primary usage.

A Note on Using AI Translation Services

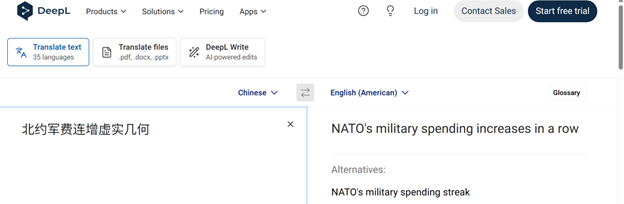

There is little doubt that AI-enabled translation services like DeepL offer convenient and mostly accurate translations of Chinese texts. However, users should exercise caution when asking the AI to translate lengthy or complicated Chinese texts. Since the Chinese written language system is not space-delimited and often contains a mix of recently invented slang words, formal, and classical Chinese (文言文) phrases and quotes, the translation software sometimes cannot adjust properly to the context in which the classical phrases are used. This could easily lead to misinterpretation.For instance, translating and searching for the phrase “nuclear force (核力量)” may return results that contain the phrase “hardcore power (硬核力量)”, which is unrelated to nuclear weapons. In another example, a PLA Daily article uses the phrase “北约军费连增虚实几何” as the title, which mixes the classical grammar with modern Mandarin. DeepL would translate the word “几何” as “geometry” because it is the most used meaning in modern Mandarin, whereas the correct interpretation is “to what extent” or “by how much” in this context (Figure 4).

In a similar instance, DeepL entirely fails to translate the part that contains classical grammar and offers an incorrect translation (Figure 5). This is most likely because the software treats the original Chinese phrase as a statement, whereas the classical grammar indicates a question.

Therefore, it is prudent to cross-reference and look up phrases individually when using AI-enabled translation tools. Inserting complete paragraphs is likely less accurate than looking up difficult phrases or individual vocabulary.

Conclusion

This paper provides a preliminary guide on using Chinese social media and video platforms for nuclear-related open-source research by reviewing the usefulness and credibility of the content released by various official and privately owned platforms (Table 2). In sum, there is no singular most useful platform for information on the Chinese nuclear force, but some may help piece together interesting findings upon cautious review and cross-reference. While advanced Chinese language proficiency and cultural familiarity remain irreplaceable skills that can greatly enhance the accuracy and speed of open-source analysis, they are neither necessary nor sufficient for successful open-source analysis on China’s nuclear forces. Researchers can still make effective and efficient use of publicly available information by applying analytical due diligence and having context-specific awareness of Chinese sources.

This publication was made possible by a generous grant from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

A Guide to Satellite Imagery Analysis for the Nuclear Age – Assessing China’s CFR-600 Reactor Facility

Satellite imagery has long served as a tool for observing on-the-ground activity worldwide, and offers especially valuable insights into the operation, development, and physical features related to nuclear technology. This report serves as a “start-up guide” for emerging analysts interested in assessing satellite imagery in the context of the nuclear field, outlining the steps necessary for developing comprehensive and effective analytical products.

What goes on in the mind of an analyst during satellite imagery analysis? Four broad steps included in this report – establishing context, collecting imagery, analyzing imagery, and drawing conclusions – serve as a simple outline for analysts interested in assessing satellite imagery with a particular focus on the nuclear field. This report uses China’s CFR-600 reactor site as a case study, providing a roadmap to the analytical thought processes behind the analysis of satellite imagery.

This report was adapted into an ArcGIS StoryMap, an interactive multimedia narrative. Click here to view the StoryMap.

Inspections Without Inspectors: A Path Forward for Nuclear Arms Control Verification with “Cooperative Technical Means”

The 2010 New START Treaty, the last bilateral agreement limiting deployments of U.S. and Russian strategic arsenals, will expire in February 2026 with no option for renewal. This will usher in an era of unconstrained nuclear competition for the first time since 1972, allowing the United States and Russia to upload hundreds of additional warheads onto their deployed arsenals if they made a political decision to do so. The removal of both the verifiable limits on nuclear weapons, as well as the agreed and proven mechanisms of information sharing about each country’s nuclear arsenal, will increase mistrust, lead to nuclear military planning based on worst case scenarios, and potentially accelerate a global nuclear arms race amid a worsening geopolitical environment.

Traditional nuclear arms control, including New START, relies on the availability of on-site inspections to verify compliance. However, Russia has suspended its participation in New START and opposes intrusive inspections, while political conditions make negotiating an equally robust successor treaty improbable in the near term.

The proposal: verifiable nuclear arms control without on-site inspections

This report outlines a framework relying on “Cooperative Technical Means” (CTM) for effective arms control verification based on remote sensing, avoiding on-site inspections but maintaining a level of transparency that allows for immediate detection of changes in nuclear posture or a significant build-up above agreed limits. This approach builds on Cold War precedents—particularly SALT II, which relied largely on national technical means (NTM)—while leveraging modern Earth-observation satellites whose capabilities have significantly advanced in recent years.

The proposed interim agreement would:

- Preserve New START’s central limits on launchers and warheads.

- Resume notifications and data exchanges.

- Uphold the principle of non-interference with national technical means of verification.

- Incorporate a set of cooperative measures to expose systems for satellite verification, making possible remote monitoring and counting of nuclear delivery vehicles and nuclear weapons.

Such a regime could either be a formal, legally-binding treaty or an informal political arrangement. A non-binding arrangement may also encourage the participation of other nuclear states willing to freeze the production and deployment of new nuclear weapons, including China, the United Kingdom, France, India, and Pakistan.

How would it work?

Significant increases in both the quality and quantity of state-owned and commercial observation satellites now allow global monitoring of missile silo fields, weapons storage sites, air bases, and ports at high resolutions, in different bands, and at actionable frequencies of observation. These developments make it possible to:

- Count strategic launchers. Missile silos, mobile launchers garrisoned in bases, submarines in ports, and heavy bombers at air bases are all observable by electro-optical and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) sensors. Large-scale silo construction is now nearly impossible to conceal.

- Assess deployment status. Cooperative measures—such as opening silo doors for satellite passes—could verify whether launchers contain missiles. AI-assisted SAR and EO imagery could detect, classify and count nuclear bombers. Unique markings or alphanumeric codes placed on mobile launchers and bombers could facilitate counting and identification from space.

- Estimate deployed warheads. New START counts every nuclear bomber as carrying a single warhead. A similar counting rule could be established for other delivery vehicles. Otherwise, exposing missiles’ re-entry vehicles (RV) during coordinated satellite overpasses could allow for the counting of warheads remotely. While this could not confirm if the displayed RVs are nuclear or decoys, it would set verifiable upper limits.

- Address non-strategic and non-deployed weapons. Novel SAR observation techniques can help detect undisclosed activity and traffic around storage facilities, ensuring weapons are not secretly moved in or out.

Why this matters

Arms control is a crucial tool for managing nuclear risks. The proposed remote-sensing verification regime could help maintain transparency, facilitate communication, and provide predictability between the United States and Russia beyond 2026, reducing the danger of nuclear arms racing without needing to tackle the politically sensitive issue of on-site inspections.

No past or present arms control regime is perfect and completely safe against cheating. An agreement fully relying on observation satellites would not fully eliminate uncertainty, but it would be relatively easier to negotiate than one with on-site inspections, and it would increasingly raise the costs of deception, providing visibility into major nuclear developments and leaving a pathway to more comprehensive arms control once it becomes politically viable in the future.

FAS Receives $500k Grant On Emerging Disruptive Technologies and Mobile Nuclear Launch Systems

The Carnegie Corporation of New York grant funds research in partnership with The British American Security Information Council (BASIC) on the destabilizing impacts of emerging and disruptive technologies on mobile nuclear launch platforms.

Washington, D.C. – November 6, 2025 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) has received a $500,000 grant to analyze the capabilities of emerging and disruptive technologies (EDTs) to track and trail mobile nuclear launch platforms—particularly land-based mobile missile forces and sea-based systems. The grant comes from the Carnegie Corporation of New York (CCNY) to investigate, alongside The British American Security Information Council (BASIC), the associated impact on nuclear stability.

The grant funds a two-year project to support FAS’ and BASIC’s joint effort to research current EDT capabilities and potential future applications in order to supply experts and policymakers with data to recommend short- and medium-term risk reduction measures. Additionally, the grant enables FAS and BASIC to bring together an interdisciplinary community of scientific, technical, and open-source intelligence (OSINT) experts.

“We are excited to partner with BASIC on this project and grateful to CCNY for the opportunity,” said Mackenzie Knight-Boyle, Senior Research Associate on the Nuclear Information Project at FAS and co-lead of the project. “As OSINT analysts, it’s important that we are aware of what new tools and capabilities are out there for tracking nuclear forces. It is essential, however, that we are responsible practitioners with a thorough understanding of the implications for nuclear stability if such technologies threaten the traditional survivability of mobile systems.”

The project scope will include desk-based research, workshops with leading experts and practitioners, briefings with stakeholders, and publications. The conclusion of the grant will result in educational events about the findings across nuclear and non-nuclear weapon states, with the objective to reduce nuclear risk.

“BASIC is delighted to be partnering with FAS to investigate the impacts of the cutting-edge emerging and disruptive technologies on the stealth of land- and sea-based mobile nuclear delivery platforms,” writes BASIC Executive Director Sebastian Brixey-Williams. “If such platforms can be detected – whether allied or adversary owned – nuclear stability may be significantly compromised. It is therefore essential that nuclear planners are equipped with robust and clear-eyed assessments of potential risks and recommendations on mitigation measures.”

The impact of “near-term” EDTs (defined as those that are currently in development or expected to develop over the next 5-10 years) is a topic BASIC has reported extensively.

“This work lies at the critical intersection between technology and policy. By strengthening a community of experts who understand these technologies and their associated risks, we can more effectively inform and engage the public and policymakers on nuclear dangers and strategic stability challenges,” said Eliana Johns, Senior Research Associate with the Nuclear Information Project at FAS and co-lead of the project.

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established eighty years ago by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address national challenges. More information about FAS work at fas.org.

Incomplete Upgrades at RAF Lakenheath Raise Questions About Suspected US Nuclear Deployment

Satellite imagery of RAF Lakenheath reveals new construction of a security perimeter around ten protective aircraft shelters in the designated nuclear area, the latest measure in a series of upgrades as the base prepares for the ability to store U.S. nuclear weapons. However, U.S. budget documents indicate that forthcoming upgrades to security and command and control are required before the base can accommodate a nuclear mission. These projects introduce more questions than answers about RAF Lakenheath’s nuclear status and what its role will be in the NATO nuclear strike mission.

In addition to these upgrades, the United Kingdom recently announced plans to expand its nuclear posture by adding a nuclear role for the Royal Air Force through the purchase of 12 F-35As from the United States to join NATO’s nuclear sharing mission; a further reduction in the “independence” of the UK deterrent.

Combined, these changes mark a departure from decades of nuclear policy and underscore a broader shift in NATO nuclear posture in response to tensions with Russia.

Are There New U.S. Nukes in the UK?

In July 2025, a set of two USAF C-17 flights directly from Kirtland AFB to RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk, England, triggered widespread rumors that nuclear weapons had been shipped to the base. While the indicators are strong, other Air Force budget documents raise questions about whether the necessary nuclear upgrades at the base have been completed to allow deployment yet.

Aside from Türkiye, each NATO country that hosts U.S. nuclear weapons has purchased the F-35A Lightning II to replace its legacy aircraft in the nuclear delivery role. In 2022, RAF Lakenheath became the first European base to receive the F-35A, and its 48th Fighter Wing remains the only USAF wing to operate both the F-15E and the F-35A nuclear-capable fighter aircraft. Years of accumulating evidence now point to the preparation of U.S.-operated RAF Lakenheath to receive U.S. B61 nuclear gravity bombs, marking the first time in nearly 20 years that the USAF nuclear mission has returned to the United Kingdom.

Then, on July 17, 2025, analysts tracked the flight of a C-17 nuclear transport plane associated with the Prime Nuclear Airlift Force from Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico to RAF Lakenheath. The direct flight from the USAF nuclear weapons depot at Albuquerque did not overfly other countries on its way to Lakenheath, a strong indicator that the aircraft could have been carrying nuclear materials. A second similar flight took place a few days later on July 23. During these dates, several signs, such as increased security measures at RAF Lakenheath, suggest that these flights could have been the first transfer of nuclear weapons to the base. Despite these strong indicators, several factors regarding additional command and security features raise doubts that a weapons shipment has already occurred.

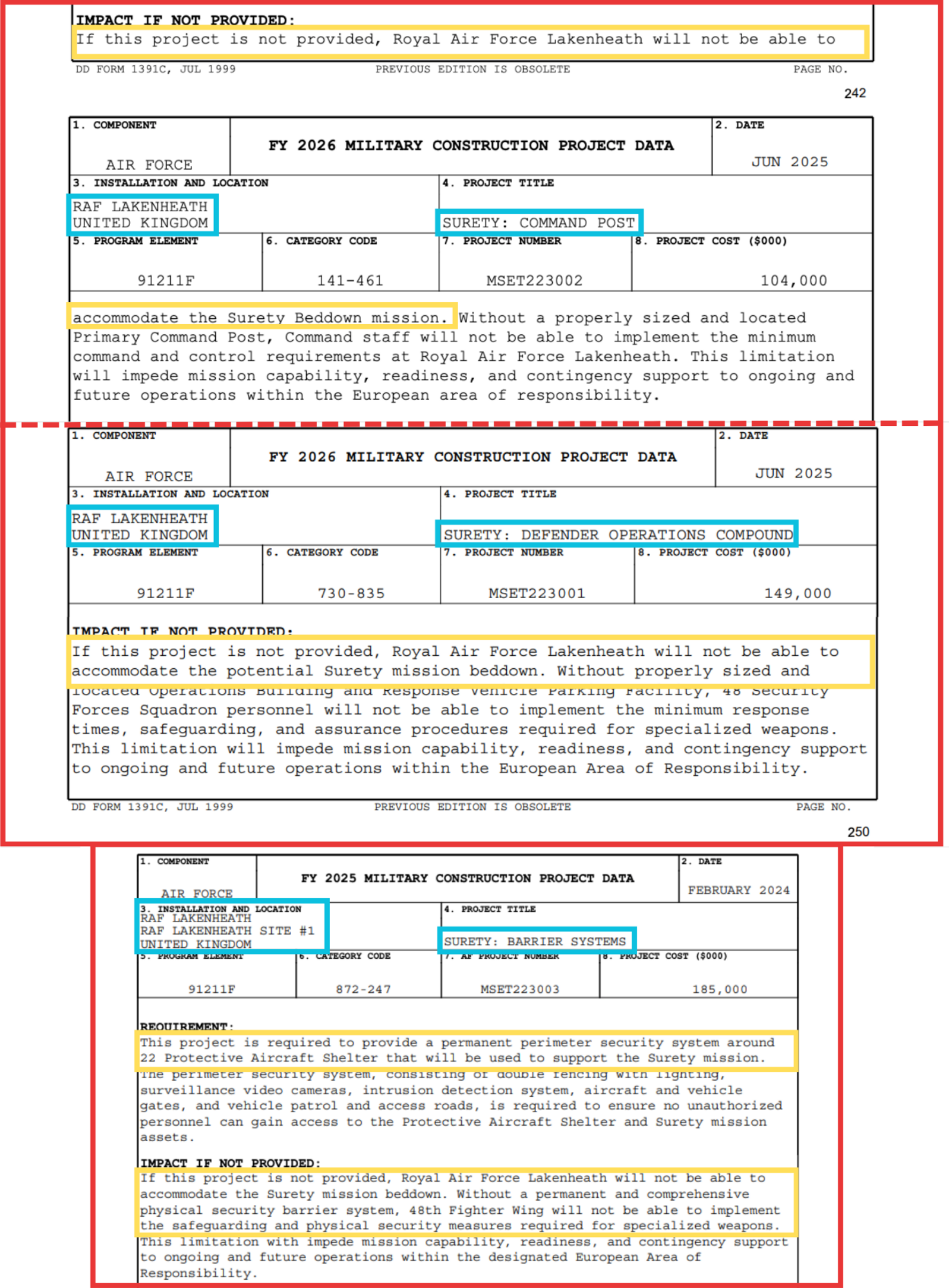

First and foremost, if nuclear weapons were to be deployed, we would expect to see a completed security perimeter around the designated nuclear area at RAF Lakenheath similar to what other nuclear bases across Europe have received (see figure 1). The FY25 USAF Military Construction Budget included a project for establishing a “Surety mission Protective Aircraft Shelter Barrier System,” which will consist of fencing, security gates, access and perimeter control roads, entry control points, and cybersecurity. The Air Force document states that the project is “required to provide a permanent perimeter security system around 22 Protective Aircraft Shelters that will be used to support the Surety mission.” Without these additional features, according to the US Air Force, “Royal Air Force Lakenheath lacks the physical security measures needed to protect Surety assets within the Protective Aircraft Shelters from unauthorized access, theft, damage, sabotage, or unauthorized use.”

Notably, satellite imagery from Planet Laboratories does reveal the initial construction of a secure fencing perimeter in the designated nuclear area that began as early as February 2025. However, the construction is taking place around ten, not 22, of the protective aircraft shelters, as the FY26 budget had indicated. Meanwhile, there is no mention of this fencing project in the FY23 or FY24 budgets, and the FY25 budget states that construction for this project is set to start in May 2026, with completion anticipated for October 2029. There is also no mention of a fencing or “security barrier” project in the FY26 budget estimate. Additionally, the FY25 budget indicates that $185 million was requested and authorized for this project, but only $5 million was appropriated, meaning the project wasn’t cancelled, but Congress only released that number out of the total authorized funds. It is possible that the funding for this project could have been redesignated to come from a different budget, but it is nevertheless an odd discrepancy.

Two other major infrastructure projects outlined in the U.S. Air Force FY26 military construction budget have yet to be completed. The first project is for a “Command Post” at RAF Lakenheath, which will involve replacing and improving security at facilities to meet intelligence security standards, hardening facilities to protect against “collateral effects,” and expanding capacity to accommodate an increase in staff to support the “surety mission” as well as the “Air Force Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications, and Global Aircrew Strategic Network Terminal equipment.” The budget states that “if this project is not provided, Royal Air Force Lakenheath will not be able to accommodate the Surety Beddown mission” (see figure 2). It continues, saying that without this facility, staff “will not be able to implement the minimum command and control requirements at Royal Air Force Lakenheath. This limitation will impede mission capability, readiness, and contingency support to ongoing and future operations within the European area of responsibility.” Construction for the command post is not scheduled to begin until August 2027 and is not expected to be completed until July 2031.

The second project outlined in the FY26 Air Force budget is a “Defender Operations Compound” at RAF Lakenheath, which includes a range of security-related infrastructure, personnel, and operational support, as the existing capacity is deemed “undersized for the current mission.” The purpose of this project is “to provide enhanced security capabilities supporting the potential stationing of specialized weapons at Royal Air Force Lakenheath. Specialized weapons surety includes materiel, personnel, and procedures contributing to the safeguarding and reliability of specialized weapons, and to the assurance that there will be no specialized weapon accidents, incidents, unauthorized weapon detonation, or degradation in performance at the target.” This section of the budget repeated a statement about the importance of this project for Lakenheath to be able to “accommodate the potential Surety mission beddown.” Construction is not scheduled to begin until March 2028 and is not expected to be completed until June 2031. Both of these programs—the Command Post and the Defender Operations Compound—were listed as “future projects” in the FY24 and FY25 budgets.

The ongoing construction of a security perimeter and the pending construction of command and control infrastructure outlined in the budget raise the question of whether the USAF would have deployed gravity bombs to Lakenheath already. Additionally, these uncertainties prompt further questions about whether Lakenheath’s role has shifted from a contingency site to a more permanent or semi-permanent deployment location.

If There Aren’t New U.S. Nukes Now, There Will Be At Some Point

Meanwhile, on June 24, 2025, the United Kingdom announced the purchase of 12 new nuclear-capable F-35As from the United States and its intention to join NATO’s nuclear sharing mission. These aircraft will be based at RAF Marham, an air base near Lakenheath with a similar Cold War nuclear legacy, and the base will also eventually be equipped to host U.S. nuclear gravity bombs in the 2030s.

The United Kingdom retired and destroyed all its nonstrategic gravity bombs in 1998 and has since relied solely on four nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarines for its nuclear deterrent. The submarines carry ballistic missiles leased from the United States, and although the warhead has been developed and manufactured by the United Kingdom, the design is similar to the U.S. Navy’s W76 warhead, and the United States also supplies the reentry body. This decision to join the NATO nuclear-sharing mission with dual-capable aircraft equipped with U.S. nuclear bombs increases the United Kingdom’s reliance on the United States and marks a significant departure from decades of UK nuclear strategy and posture, apparently in reaction to the growing concern about Russia.

This plan was first hinted at in the UK’s latest Strategic Defence Review—published on June 2, 2025—which recommended that the Ministry of Defence “commence discussions with the United States and NATO on the potential benefits and feasibility of enhanced UK participation in NATO’s nuclear mission.” Less than a month later, the UK government formally announced its decision to buy the 12 F-35As from the United States. A parliamentary inquiry to the Minister of Armed Forces by the Defence Committee questioned whether the decision is coherent with the UK’s current nuclear doctrine and raised concerns about retaining British nuclear sovereignty, considering that the 12 F-35As will not be able to use their nuclear weapons unless authorized to do so by the president of the United States. The inquiry Chair also commented on how this change is the “most significant defence expansion since the Cold War” and noted that the UK’s Defence Nuclear Enterprise remains outside of meaningful parliamentary inquiry, despite accounting for around 20% of the total defence budget.

Similar to the upgrades taking place at Lakenheath, the future deployment of U.S. gravity bombs to RAF Marham will require significant upgrades to command and control and infrastructure at the base. From specialized tarmacs for the new F-35As, to updating the protective aircraft shelters and specialized WS3 storage vaults for nuclear gravity bombs (which were deactivated in the late-1990s), to improving security perimeters and installations at the base, RAF Marham has a long way to go before the nuclear mission becomes operational in the early 2030s.

The Bigger Picture in Europe

The nuclear upgrades at RAF Lakenheath and RAF Marham contradict statements made by NATO officials just a few years ago. In 2021, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated, “We have no plans of stationing any nuclear weapons in any other countries than we already have these nuclear weapons as part of our deterrence.” Two years later, in 2023, then-head of NATO nuclear policy Jessica Cox echoed Stoltenberg’s assurance, saying, “There is no need to change where they are placed.”