A Response to Congresswoman Tauscher’s Article in Nonproliferation Review

A recent article, “Achieving Nuclear Balance”, in Nonproliferation Review, by Congresswoman Ellen Tauscher, Chairwoman of the Strategic Forces Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee, includes a sobering summary of the dangerous nuclear policies of the Bush administration, including its desire for new nuclear weapons and an expansion of the roles of nuclear weapons. Congresswoman Tauscher has been an important voice of reason in the nuclear debate and one of the primary forces behind efforts to force a fundamental review of the missions of nuclear weapons, to ask what nuclear weapons are for.

Nevertheless, her arguments in support of exploring the Reliable Replacement Warhead are mistaken and based on deeply rooted but ultimately unsupported assumptions. Her essay highlights the critical importance of carefully defining terms and avoiding being fooled by our own euphemisms.

(more…)

Congressman Markey on the US-India Nuclear Deal

Last week, Congressman Ed Markey (D-Mass) visited FAS to talk about the India-US deal. Markey, who strongly supports closer ties with India, opposes the nuclear deal because it undermines the Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT). A transcript and video of his comments are on the FAS website.

What I found most interesting about his talk was a graphic showing the growth in U.S.-Indian trade over the past few decades. (Our chart is not a reproduction of the chart used my Mr. Markey but created from the same data.) It goes up…and up and up. It has gone up even during politically difficult times, for example, after the 1974 Indian nuclear test. The Congressman’s point is that, when people argue for the nuclear deal because it will allow a blossoming of trade between the two countries, they miss the point entirely. Trade with India has been growing for years, it continues to grow now, and it will grow in the future whether we have a nuclear deal or not. So the trade benefit is simply not there. But the harm done to the NPT definitely remains.

(more…)

Uranium spill hidden from public because of NRC policy

A very disturbing report in yesterday’s Guardian details how the Nuclear Regulatory Commission sealed records for two companies that manufacture and store highly enriched uranium in 2004. This was after some “protected information” regarding the Navy’s nuclear program were found on the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s website. I am not sure what “protected information” is, but it apparently included “papers about the policy itself and more than 1,740 documents from the commission’s public archive.” This in effect hid from the public both information regarding their Navy work and records unrelated to the Navy’s work including the plant’s safety records.

YIKES! One incident hidden from the public was a rather disturbing spill of 9 gallons of uranium in 2006 at privately owned Nuclear Fuel Services Inc located in Erwin, Tennessee. While it is unclear how concentrated the liquid was, it is unlikely that it was enough to spontaneously detonate at the kiloton level, but certainly could have caused a nuclear chain reaction and explosion. It really depends upon how much uranium was in the liquid. To the NRC’s credit they later decided that this was a significant enough of an incident that they overrode the policy to make sure that Congress was made aware of it in their annual report, which included reference to three “abnormal occurrences.” In total there were nine violations or test failures that were hidden from the public since 2005 at the company, which has been supplying nuclear fuel to the Navy since the 1960’s.

From the Guardian:

“While reviewing the commission’s public Web page in 2004, the Department of Energy’s Office of Naval Reactors found what it considered protected information about Nuclear Fuel Service’s work for the Navy. The commission responded by sealing every document related to Nuclear Fuel Services and BWX Technologies in Lynchburg, Va., the only two companies licensed by the agency to manufacture, possess and store highly enriched uranium.”

Not really an open book: What I find astonishing is that even after the cat was out of the bag, neither the NRC nor the Department of Energy posted information relating to the incident or the policy on their websites. I certainly understand the principle of not making bad news a bigger story than it already is, but if history tells us anything we know that it is much better to come clean about these things before you get embarrassed by the press.

History of violations: Nuclear Fuel Services seems to have a history of problems that go back some time. On July 30 of this year a “confirmatory order” was published in the Federal Register that details some of this history and the fact that the Nuclear Regulatory Commission had to go into arbitration with the company over the issues.

From the Federal Register:

“Given the number and repetitive nature of some of the apparent violations, the parties acknowledged that: (1) Past disposition of violations via the enforcement policy had not resulted in NFS’s development of corrective actions capable of preventing recurrence of violations; (2) a deficient safety culture at NFS appeared to be a contributor to the recurrence of violations; and (3) a comprehensive, third party review and assessment of the safety culture at NFS represented the best approach for the identification and development of focused, relevant and lasting corrective actions.”

The order was originally issued in February of this year, but was not released because of the NRC policy. For what it is worth, the company issued a public response to the order on their web page.

Targeting Missile Defense Systems

By Hans M. Kristensen

The now month-long clash between Russia and the West over U.S. plans to build a missile defense system in Europe should warn us that – despite important progress in some areas – Cold War thinking is alive and well.

The missile defense system, Moscow says, is but the latest step in a gradual military encroachment on Russian borders by NATO, and could well be used to shoot down Russian ballistic missiles. The head of Russia’s Strategic Missile Forces and President Putin have suggested that Russia might target the defenses with nuclear weapons. The United States has rejected the complaints insisting that Russia has nothing to fear and that the defenses will only be used against Iranian ballistic missiles. European allies have complained that the Russian threats are unacceptable and have no place in today’s Europe.

That may be true, but the reactions have revealed a frightening degree of naiveté about strategic war planning in the post-Cold War era, a widespread belief that such planning has somehow stopped. It has certainly changed, but all the major nuclear weapon states insist that they must hedge against an uncertain future and continue to adjust their strike plans against potential adversaries that have weapons of mass destruction. Russia continues to plan against the West and the West continues to plan against Russia. The plans are not the same that existed during the Cold War, but they are strike plans nonetheless.

The argument made by some officials that missile defense systems are merely defensive and don’t threaten anyone is disingenuous because it glosses over a fact that all planners know very well: Even limited missile defenses become priority targets if they can disturb other important strike plans. The West concluded that very early on in its military relationship with Russia.

Cold War Targeting of Missile Defense Systems

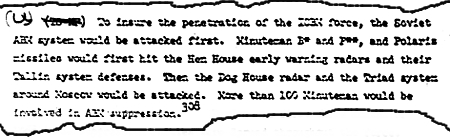

In 2003, I received a declassified Strategic Air Command document that showed how the United States reacted when the Soviet Union built a limited missile defense system back in the late 1960s. The response was overwhelming: A nuclear strike plan that included more than 100 ICBMs plus an unknown number of SLBMs to overwhelm and destroy the Soviet interceptors and radars. Based on the declassified information, two colleagues and I estimated in an article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists that the total strike plan involved approximately 130 nuclear warheads with a total combined yield of some 115 megatons. Here is how the SAC historian described the plan:

|

|

|

|

“To ensure the penetration of the ICBM force, the Soviet ABM system would be attacked first. Minuteman E and F and Polaris missiles would first hit the Hen House early warning radars, and their Tallin system defenses [SA-5 SAM, ed.]. Then the Dog House radar and the Triad system around Moscow would be attacked. More than 100 Minuteman would be involved in the ABM suppression.” |

The Soviet ABM system back then consisted of about fifteen facilities, including eight launch sites around Moscow with a total of 64 nuclear-tipped interceptors, half a dozen SA-5 launch complexes (later found not to have much ABM capability) near Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), and at least three large early warning radars. Each of these surface facilities were highly vulnerable to the blast effect from a single nuclear warhead, so the large number of ICBMs was mainly needed to “suppress” (overwhelm) the interceptors.

In the late 1980s, the Soviets upgraded they system by moving 32 remaining interceptors at four sites into underground silos (see Figure 2) and adding 68 shorter-range nuclear-tipped interceptors at five new sites closer to Moscow. This hardened and dispersed the interceptors, requiring U.S. planners to upgrade their strike plan, which probably ballooned to more than 200 warheads (although with less total yield due to more accurate missiles with less powerful warheads).

|

|

|

|

Four long-range Gorgon interceptor site crescent Moscow toward the northwest. The 217-mile (350-kilometer) range Gorgon carries a 1 Megaton warhead. The site shown here is near Poryadino southwest of Moscow. There are unconfirmed rumors that the interceptors have been removed and the system is in the process of decommissioning. |

The 68 shorter-range (50 miles, 80 km) interceptors added to the system in the late 1980s were the nuclear-armed Gazelle. Each missile carried a 10-kiloton warhead. The five launch sites, which are still thought to be operational, are positioned in a circle around Moscow approximately 13 miles (23 kilometers) from the center of the city. The 68 interceptors are deployed in hardened silos, 16 at two sites (Northwest and Southeast), and 12 at each of the other three sites. Public uncertainty about the location of the fifth site was recently resolved by a satellite image showing the site next to the Pill Box radar north of Moscow.

|

|

|

|

Five launch sites with Gazelle interceptors in hardened silos are located in a circle around Moscow as part of the A-135 ABM system. The sites have either 12 silos, like the Southwestern site (top) near Moscow Vnukovo airport, or 16. The fifth site (bottom) next to the Pill Box ABM radar north of Moscow has 12 silos, and is depicted in the Pentagon drawing (insert). |

All of this happened during the Cold War and many things have changed, but the basic motivation for targeting a limited missile defense system then was the same as today: The Soviet ABM system was entirely defensive and couldn’t threaten anyone (to paraphrase a characterization frequently use by U.S. and NATO officials to justify their missile defense plans today), but it could disturb the main ICBM attack on Moscow and military facilities downrange. That made it a top-priority target. And even though U.S. planners suspected that the system was not very efficient, they committed about 10 percent of the entire ICBM force to destroy it. To the extent the Russia ABM is operational, U.S. nuclear strike plans probably still target it today.

|

Figure 4: |

||

|

||

| Type | Designation, Location | Remarks |

| Interceptor | ||

| Gorgon (SH-11/ABM-4)* | – E05, 6 miles (9 km) southwest of Karabanovo, at 56°14’39.51″N, 38°34’41.75″E | |

| – E24, 4 miles (6.5 km) northwest of Poryadino, at 55°20’58.31″N, 36°28’50.28″E | ||

| – E31, 6 miles (9.6 km) north of Nudol Sharino, at 56° 9’0.18″N, 36°30’13.08″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| – E33, east of Klin, at 56°20’30.03″N, 36°47’35.21″E | Operational status uncertain | |

| Gazelle (SH-08/ABM-3) | – South of Ashcherino, at 55°34’40.06″N, 37°46’17.89″E | |

| – 3 miles (4.8 km) southeast of Kaliningrad, at 55°52’41.63″N, 37°53’37.51″E | ||

| – 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Kartmazovo, at 55°37’31.81″N, 37°23’19.99″E | ||

| – Korostovo, at 55°54’6.00″N, 37°18’28.33″E | ||

| – 6 miles (9.6 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’50.69″N, 37°47’12.01″E | ||

| Radar** | ||

| Pill Box (Don-2N) | – 7 miles (11.3 km) west of Sofrino, at 56°10’23.48″N, 37°46’12.51″E | |

| To view satellite images of all these sites, click here. * There are unconfirmed rumors that the Gorgon interceptors have been removed from the system. ** Other forward-based early-warning radars are not included in this overview. Two older radars (Dog House and Cat House) are no longer operational. |

||

Now history repeats itself, but the table has been turned. Today it is the United States building a limited missile defense system (more capable than the Soviet system, but focused on “rogue” state missiles), and it is the Russians who say they need to target it to maintain the effectiveness of their deterrent. The Cold War may be over, but military and policy planners in both countries still think in Cold War terms.

Russia’s Real Concerns Today

Most of the current debate has focused on whether the missile defense system could disrupt Russia’s deterrent against the United States. Although this may be a concern to Russian planners in the long run, their objections probably have more to do with the capability of the system to disrupt limited strikes against France or the United Kingdom. Russian nuclear strike plans against each of those smaller nuclear powers probably include only a few ICBMs, but their flight path would take them right over the planned interceptors (Figure 5).

|

Figure 5: |

|

|

The Russian objections to the proposed US anti-ballistic missile defense system in Poland and the Czech Republic seem more linked to potential Russian strike plans against British and French nuclear forces than to strike plans against the United States. The trajectories for a hypothetical ICBM attack against French and British nuclear submarines bases pass over the proposed U.S. missile defense system in Europe. |

Russian planners are probably also thinking ahead. By 2015, under current plans, Russia’s ICBM force is expected to have declined from about 480 missiles today to approximately 150. Significantly less than the 450 the United States plans to retain. This, of course, will have no real implications for Russia’s security, but for Russian planners it means that a European ballistic missile defense system with 10 interceptors (that could quickly be expanded) and 21 interceptors at Fort Greely in Alaska (and silos already dug for more) suddenly doesn’t seem so limited anymore. Indeed, if Russia’s statements about targeting a future missile defense system in Europe are genuine, then the U.S. interceptors in Alaska are probably already targeted by Russian missiles.

Implications

There’s probably a fair amount of chest beating in the Russian statements, especially because Russia has little to gain from antagonistic relations with the West in the long run. Putin’s recent “offer” to include Russian radars in the Western defense plans suggests he is trying to find a way out of the stalemate, although not necessarily the way out that Western governments would like to see.

It would, of course, be much simpler if the Russians “just got over it” and accepted Western missile defenses as a fact of life. But they haven’t, and there are clear signs that U.S. missile defense plans have already influenced Russian military planning. An eerie feeling is emerging in Washington that the Russian “experiment” may be over and that Russia, instead of becoming a full partner or a full enemy, is entering a new assertive period intent on acting as a counterbalance to current U.S. foreign policy. That may not necessarily be a bad thing, unless of course it plays out in the form of military posturing.

Western claims that Russia has nothing to fear, although genuine, miss the point: They apparently fear something enough to publicly use it to underscore their own capability. East and West need to figure out what has gone wrong and how to get out of this mess before strategic antagonism becomes a prominent policy feature for the long haul. The fact that we’re even having this debate nearly two decades after the Cold War ended shows that both countries have failed miserably to move beyond Cold War posturing and planning principles.

Background: The Protection Paradox | Russian Nuclear Forces, 2007 | Pavel Podvig’s Analysis

United States Removes Nuclear Weapons From German Base, Documents Indicate

|

|

The United States appears to have quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base. Here a B61 nuclear bomb is loaded unto a C-17 cargo aircraft. |

By Hans M. Kristensen

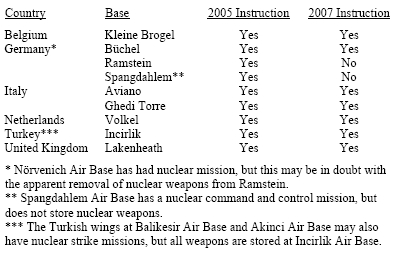

The U.S. Air Force has removed its main base at Ramstein in Germany from a list of installations that receive periodic nuclear weapons inspections, indicating that nuclear weapons previously stored at the base may have been removed and withdrawn to the United States.

If correct, the withdrawal reduces the number of U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe to an estimated 350 B61 bombs, or roughly equivalent to the size of the entire French nuclear weapons inventory.

New Nuclear Inspection List

The new nuclear inspection list is contained in the unclassified instruction Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visit (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visit (FEV) Program Management published by the U.S. Air Forces in Europe (USAFE) on January 29, 2007. The instruction supersedes an earlier version from March 29, 2005, which did include Ramstein Air Base.

The NSSAV team includes 14-31 inspectors with expertise in the different areas of nuclear weapons mission management. The NSSAV normally takes place six months prior to the a Nuclear Surety Inspection (NSI), and the visit is intended to help prepare the unit for the much more rigid NSI, which units with nuclear weapons mission responsibilities must pass at least every 18 months to remain certified to handle and store nuclear weapons. During the visit, which normally lasts a week, the NSSAV team observes and evaluates how the unit conducts day-to-day operations and administers nuclear surety program management. A typical visit includes uploading and downloading of training nuclear weapons on strike aircraft.

|

|

|

|

Sources: U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NSSAV) and Functional Expert Visits (FEV) Program Management, January 29, 2007; U.S. Air Forces in Europe, Instruction 91-125, Nuclear Surety Staff Assistance Visits (NS SAV) and Functional Expert Visits |

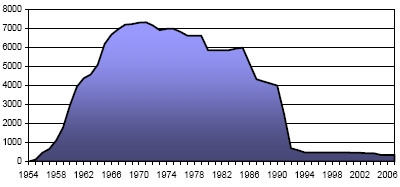

A Brief History of U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe

The current number of approximately 350 nuclear weapons is only a fraction of the force level the United States deployed in Europe during the Cold War. That level reached a peak of 7,300 weapons in 1971. The number dropped to 4,000 by the end of the Cold War in 1990, plunged to 700 in 1992, and leveled off at approximately 480 weapons (all bombs) in 1994. This ended the dramatic period of nuclear disarmament initiatives, which has since been replaced by a period of relative stability with slow and gradual reductions happening mainly due to base closures rather than arms control initiatives.

One of the last acts of the Clinton administration in late 2000 was to authorize deployment of 480 nuclear bombs at nine bases in seven European NATO countries. Twenty of the bombs were withdrawn in 2001 after Greece pulled out of the NATO nuclear strike mission, and another 20 were withdrawn in 2003 when Germany closed Memmingen Air Base.

The Bush administration updated the deployment authorization for Europe in May 2004 to reflect these changes, and it is possible that the authorization may have cleared the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base. But as of late March 2005, Ramstein was still on the updated list of installations receiving nuclear surety staff assistance visits. The report U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe published by the Natural Resources Defense Council in February 2005 estimated 440-480 nuclear bombs deployed in Europe.

|

US Nuclear Weapons in Europe, 1954-2007 |

|

| The U.S. deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe peaked in 1971 at 7,300 weapons, was reduced significantly a decade and a half ago, but has remained comparatively stable since then. |

Then in May 2005, the German magazine Der Spiegel cited unnamed German defense officials saying that the U.S. had quietly removed nuclear weapons from Ramstein Air Base during major construction work at the base. The assumption was that the move was temporary, but the German officials hoped they would never return. Their wish seems to have come through with Ramstein’s removal from the updated Air Force instruction published in January 2007.

Both the U.S. government and NATO have always refused to disclose the number of weapons deployed in Europe but occasionally have provided the approximate range of the force level or the percentage of reduction since the Cold War. In an interview with Italian RAINEWS in April 2007, NATO Vice Secretary General Guy Roberts also refused to disclose the number weapons, but explained: “We do say that we’re down to a few hundred nuclear weapons.”

Seen in Cold War context, 350 bombs may not seem like a lot, but for the post-Cold War era it is a significant force. It is roughly equivalent is size to the entire French nuclear arsenal, larger than the Chinese nuclear arsenal, and it is larger that the nuclear arsenals of all the three non-NPT countries Israel, India and Pakistan combined.

Recent Reaffirmation of Nuclear Mission

Despite the apparent reduction, NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) as recently as June 15, 2007, reaffirmed the importance of deploying U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe. NPG stated that the purpose of the weapons is to “preserve peace and prevent coercion and any kind of war,” and that NATO places “great value” on the U.S. deployment in Europe. The NPG did not identify any particular enemy that the weapons are intended to protect against, but instead said they “provide an essential political and military link between the European and North American members of the Alliance.”

|

|

|

|

The only nuclear weapons storage site in Germany now appears to be Büchel Air Base, where theft – not enemy attack – is the main threat, as practiced by these security forces in February 2007. |

Germany’s Nuclear Decline

The apparent withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base also raises questions about the continued nuclear strike mission of the German Tornado squadron at Nörvenich Air Base. The base previously stored nuclear weapons, but they were moved to Ramstein in 1995 with the intent that they could quickly be returned to Nörvenich if necessary. A withdrawal from Ramstein would indicate that the 31st Wing at Nörvenich probably no longer has a nuclear strike mission, and that Germany’s contribution to NATO nuclear mission now is reduced to Büchel Air Base.

A reduction to a single German nuclear base with “only” 20 nuclear bombs is a dramatic change from the late-1980s, when more than 2,570 nuclear weapons were deployed at dozens of locations across the country. The latest withdrawal follows a political seachange in German voters’ views on nuclear weapons in the country. A poll published by Der Spiegel in 2005 revealed an overwhelming support across the political spectrum for a complete withdrawal of nuclear weapons from Germany.

The German government said in May 2005 that it would raise the issue of continued deployment within NATO, but officials later told Der Spiegel that the government had changed its mind. Yet the withdrawal from Ramstein indicates that the government has been more proactive than thought or that the Bush administration “got the message” and decided not to return the weapons. The withdrawal reduces Germany from the status of a major nuclear host nation to one on par with Belgium and the Netherlands, both of which also only have one nuclear base. The German government can now safely decide to follow Greece, which in 2001 unilaterally left NATO’s nuclear club. This in turn would open the possibility that Belgium (and likely also the Netherlands) will follow suit, essentially throwing NATO’s long-held principle of nuclear burdensharing into disarray.

A New Southern Focus

For now, the withdrawal from Ramstein Air Base shifts the geographic focus of NATO’s nuclear posture to the south. Before the withdrawal, a clear majority of NATO’s nuclear weapons were deployed in Northern and Central Europe. After the withdrawal, however, more than half (51%) of the weapons are deployed in Southern Europe along the Eastern parts of the Mediterranean Sea in Italy and Turkey.

The geographic shift has implications for international security issues that NATO countries are actively involved in, such as the attempts to create a Mediterranean Nuclear Weapons Free Zone, and the efforts to persuade countries like Iran not to develop nuclear weapons. The new southern focus of NATO’s nuclear posture will make it harder to persuade other countries in the region to show constraint.

Background: Satellite Images of U.S. Nuclear Weapon Bases Europe | U.S. Nuclear Weapons In Europe (report from 2005)

Article: Pakistani Nuclear Forces, 2007

|

|

Shaheen 2 launch |

By Hans M. Kristensen

Pakistan is preparing its next-generation of nuclear-capable ballistic missile for deployment. A satellite image taken on June 5, 2005, shows what appears to be 15 Transporter Erector Launchers (TELs) for the medium-range Shaheen 2 fitting out at the National Defense Complex near Fatehjang approximately 30 kilometers southwest of Islamabad.

The vehicles were discovered as part of preparations for the latest Nuclear Notebook on Pakistani nuclear forces published in the May/June issue of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. The Notebook is written by Hans M. Kristensen of the Federation of American Scientists and Robert S. Norris of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The authors estimate that Pakistan currently has an arsenal of about 60 nuclear weapons. In the last five and a half years, Pakistan has deployed two new nuclear-capable ballistic missiles, entered the final development stages of a potentially nuclear-capable cruise missile, started construction of a new plutonium production reactor, and is close to completing a second chemical separation facility. As Pakistan completes development of two more nuclear-cable ballistic missiles and a cruise missile in the next few years, the nuclear arsenal will increase further.

| Pakistani government responds to blog:The government downplayed a report by an organization of American scientists that Pakistan is preparing its next generation nuclear-capable ballistic missile for deployment. “This is a speculative report which contains part fact and part fiction,” is how the spokesperson characterized the report.”Source: Dawn, “N-Capable Missiles,” May 11, 2007. |

The main driver for Pakistan’s nuclear modernization appears to be India’s nuclear build-up, although national prestige probably also is a factor. The two countries appear to be entering a new phase in their regional nuclear arms race with medium-range ballistic missiles gradually replacing aircraft as the backbone of their nuclear strike forces. In contrast to aircraft, ballistic missiles have a very short flight time and cannot be recalled once launched.

(more…)

New US Navy Report on Chinese Navy

Despite frequent complains about lack of transparency in Chinese military planning, a new report from the Office of Naval Intelligence – recently described in the Washington Times and subsequently released to the Federation of American Scientists in response to a Freedom of Information Act request – boasts a high degree of knowledge about meticulous details of the Chinese navy’s operations, training, personnel and regulations.

The details in the report China’s Navy 2007 are many but unfortunately largely superfluous to the main answers many want to hear from the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) and other intelligence agencies: How are Chinese naval forces and operations evolving, and what do the changes mean?

Questionable Reporting

Unfortunately, some have already (mis)used the ONI report to hype fear that China is rising and out to get us. One example is the Washington Times, which last week described the report findings in a highly selective manner. Despite many unknowns about China’s military modernization and intentions, the paper’s description only included excerpts that indicate a threat or worrisome development. Moreover, the paper appears to have distorted the ONI report’s description of the Chinese submarine force’s importance: “China’s submarine forces are given ‘first priority’ of all branches of the navy, it states.”

But that’s not what the ONI report states. In fact, “first priority” as quoted by the Washington Times does not appear in the report at all. What the report says is very different: “The PLA Navy’s submarine forces…are generally listed as first in protocol order among the PLAN’s five branches.”

Being listed first in the protocol order is not the same as being the “first priority” of all the navy branches. According to the RAND Cooperation’s reference book The People’s Liberation Army as Organization:

| “PROTOCOL ORDER IN THE PLA: The PLA [People’s Liberation Army] is a very protocol oriented institution. When the PLA lists its military regions, services, service branches, administrative organizations, or its key personnel, the lists are almost always in protocol order, what the PLA calls organizational order (zuzhi xulie). The first criterion is generally the date a particular organization was established. For example, the order of the three services (junzhong) is always Army (August 1927), Navy (April 1949), and Air Force (November 1949). Since the Second Artillery Corps (July 1966) is technically a branch/service arm (bingzhong), and is usually not listed with the services….Therefore, the protocol order is more of an administrative tool today rather than a reflection of priority within the hierarchy.” (Emphasis added) |

What the ONI Report Does (and Doesn’t) Say

In contrast with the threat-focused style of the Washington Times reporting, the ONI report purports to have a much broader objective to “better understand the world’s fastest growing maritime power and its means of naval action and thereby foster a better understanding of China’s Navy.” The report observes up front that the enhanced naval power sought by China “is meant to answer global changes in the nature of warfare and domestic concerns about continued economic prosperity.” The drive to build a military component to protect the means of economic development, ONI states, “is one of the most prevalent historical reasons for building a blue water naval capability.”

Part of what has triggered the Chinese modernization is the extraordinary military capabilities that the United States have developed and deployed and demonstrated over the past two decades. The point is not that the United States is to blame and China just an innocent victim, but that all military modernization influences potential adversaries.

To that end the most interesting aspect about the ONI report may not be so much what it says but what it leaves out. Missing are many of the key developments that most concern US military planners and lawmakers, and many of the developments that are ignored by those who hype the Chinese “threat.”

For example, the ONI report does not include new information about the size of the Chinese navy. Instead it reprints a brief overview from the 2006 DOD report Military Power of the People’s Republic of China. Nor does the ONI report describe the construction of several new types of submarines, including the Type 093 nuclear-powered attack submarine and the Type 094 ballistic missile submarine.

Likewise, the ONI report begins with reprinting portions of two Chinese government documents, one of which states that the Chinese navy’s “capability of nuclear counter-attacks has also been enhanced.” This refers to China’s current possession of a single Xia-class ballistic missile submarine, but the ONI leaves out any information about what that enhancement actually is.

The other Chinese government statement used describes that the Chinese navy is “enhancing its capabilities in…nuclear counterattacks.” This is a hint that China is building a new class (Type 094 or Jin-class) of ballistic missile submarines that will be equipped with the long-range Julang-2 ballistic missile. Yet the ONI report does not give any details about the status of those programs much less what they mean for the Chinese navy or Chinese intentions.

In addition, the ONI report contains a very detailed description of the various categories of training used by the Chinese submarine force, yet it doesn’t mention submarine patrols with one word. The omission is curious because the report describes that Chinese submarines in the late 1970s began conducting independent sustained operations in the Pacific, and that “long-range navigation training is an important overall type of training for submarines.” So why leave out the important fact that the number of patrols have declined since 2000 rather than increased with the acquisition of more capable submarines?

To that end, the ONI report describes how the “basic hands-on and crisis-management training for strategic-missile submarines that cannot be conducted while the submarine is navigating underwater for long periods of time must be conducted on shore.” Yet it leaves out the important piece of information that China’s missile submarine Xia has never conducted a patrol.

Apparently, too little transparency is not only a problem in the Chinese military.

Balanced Reporting

One week before the Washington Times hyped the ONI report, the nominated commander of Pacific Command, Admiral Timothy J. Keating, testified before the Senate Armed Services Committee where he dismissed alarmist reports of recent gains in Chinese submarine development.

“If the reports are fairly accurate, they are well behind us technologically. We enjoy significant advantages across the spectrum of defensive and offensive systems, in particular undersea warfare,” he said according to Taipei Times. In an interview with the paper, Keating added: “Should it become necessary for us to put our forces [in harm’s way], the development of Chinese submarines are [sic] a concern to us, but it is hardly an insurmountable concern.”

Admiral Keating’s testimony was not covered by the Washington Times.

Breaking the cycle of military modernizations that trigger military modernizations is perhaps the biggest challenge in US-Chinese relations. Balanced reporting is another.

Background: China’s Navy 2007 | China Naval Modernization | FAS/NRDC Report

Small Fuze – Big Effect

“It is not true,” British Defence Secretary Des Browne insisted during an interview with BBC radio, that a new fuze planned for British nuclear warheads and reported by the Guardian will increase their military capability. The plan to replace the fuze “was reported to the [Parliament’s] Select Committee in 2005 and is not an upgrading of the system; it is merely making sure that the system works to its maximum efficiency,” Mr. Browne says.

The minister is either being ignorant or economical with the truth. According to numerous statements made by US officials over the past decade, the very purpose of replacing the fuze is – in stark contrast to Mr. Browne’s assurance – to give the weapon improved military capabilities it did not have before.

The matter, which is controversial now because Britain is debating whether to build a new generation of nuclear-armed submarines, concerns the Mk4 reentry vehicle on Trident D5 missiles deployed on British (and US) ballistic missile submarines. The cone-shaped Mk4 contains the nuclear explosive package itself and is designed to protect it from the fierce heat created during reentry of the Earth’s atmosphere toward the target. A small fuze at the tip of the Mk4 measures the altitude and detonates the explosive package at the right “height of burst” to create the maximum pressure to ensure destruction of the target. The new fuze will increase the “maximum efficiency” significantly and give the British Trident submarines hard target kill capability for the first time.

US Statements About Enhanced Capability

Unlike the British government, US officials and agencies have been very clear that the new fuze is not merely a replacement but a significant upgrade that will give the Mk4 significant military capabilities. The Department of Energy’s Stockpile Stewardship and Management Plan from 1997 stated that the whole purpose of developing a new fuze in the first place was to “enable [the] W76 to take advantage of [the] higher accuracy of the D5 missile.”

At about the same time, the head of the US Navy’s Strategic Systems Command, Rear Admiral George P. Nanos, explained in The Submarine Review that the “capability for the [existing] Mk4…is not very impressive by today’s standards, largely because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” But “with the accuracy of D5 and Mk4, just by changing the fuse in the Mk4 re-entry body, you get a significant improvement,” Admiral Nanos stated. In fact, “the Mk4, with a modified fuze and Trident II accuracy, can meet the original D5 hard target requirement.”

| Trident Mk4A Reentry Vehicle |

|

| The US Navy is saying – and the British government is denying – that a new fuze for the Mk4 reentry vehicle will increase the capability against hard targets. |

For US war planners, this improvement was necessary because the main US hard target killer, the MX Peacekeeper ICBMs with high-yield W87 warheads, were being retired as a result of the never-ratified 1992 START II treaty and the 2002 Moscow Treaty (SORT). The last Peacekeeper stood down in 2005. Some of the W87 are now being backfitted unto the Minuteman III ICBMs with a new guidance system to retain ICBM hard target kill capability. The Navy has a dedicated hard target kill W88 warhead on some of its D5 missiles, but with the new fuze on the W76-1/Mk4A the hard target kill capability will increase significantly. The first W76-1/Mk4A is scheduled to be delivered in September 2007.

Implications for British Deterrence

Admiral Nanos’ statement implies that British Trident submarines have never had hard target kill capability “because the Mk4 was never given a fuze that made it capable of placing the burst at the right height to hold other than urban industrial targets at risk.” With the new fuze, however, the British Trident submarines “can meet the original D5 hard target requirement,” and hold at risk the full range of targets.

So why does the British upgrade come now? After all, British nuclear submarines have cruised the oceans for decades with less capable fuzes and still ensured, so it has been said, Britain’s survival and made “significant contributions” to NATO’s deterrence.

There are several possibilities. British nuclear planners may have successfully argued that they need more accurate nuclear weapons to better deter potential adversaries. That is the dynamic the created in the Trident system during the Cold War. Since then, Britain has moved from a Soviet-focused deterrent to a “Goldilocks doctrine” today aimed against three incremental sizes of adversaries: Russia, “rogue” states, and terrorists.

Another possibility is that it may be a result of Britain not having an independent deterrent. Rather than designing and building its nuclear missiles itself, British leases them from the US missile inventory. The warhead installed on the “British” missiles is believed to be a modified – but very similar – version of the American W76. But the reentry vehicle that contains the explosive package appears to be the same: the Mk4. And since the US is upgrading its Mk4 to the Mk4A with the new fuze, Britain may simply have gotten the new capability with its existing lease.

Whatever the reason, the British government’s denial is clearly flawed. If the government believes so strongly that a nuclear deterrent is still necessary, why be so timid about its new capability? After all, what is the new capability good for if the potential adversaries can’t be told about it? And if the British government believes in the nuclear deterrent, then it has to play the deterrence role and be honest about it, and not – as it does now – pretend to be a nuclear disarmer while secretly enhancing its nuclear weapons capabilities.

No Need to Replace UK Nuclear Subs Now, FAS Board Member Tells Brits

(Updated January 26, 2007)

(Updated January 26, 2007)

British Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines have at least 15 years more service life in them, and the U.K. government does not have to make a decision now on whether to replace them with a new class of submarines, Richard Garwin told BBC radio Tuesday.

Garwin, who is a member of the Federation of American Scientists Board of Directors and a long-term adviser to the U.S. government on defense matters, is in Britain to testify before the House of Commons Defence Select Committee on the future of Britain’s nuclear deterrent.

The U.K. government announced on December 4, 2006, that it had decided to replace its current Vanguard-class sea-launched ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) with a new class to enter operation in 2024. If approved by the parliament, the plan would extend Britain’s nuclear era into the 2050s.

According to the U.K. government, a decision to build a new new class must be made now because the Vanguard-class SSBNs only have a have a design life of 25 years. But Garwin says that the submarines have a minimum design life of 25 years, which can be extended by at least another 15 years. A decision made now is premature and unwise, Garwin told BBC, because the large Trident missiles may not be necessary 15 years from now.

New additions: Garwin testimony / House of Lords debate

Background: BBC Today | Garwin Archive at FAS | Britain’s Next Nuclear Era

Nuclear Missile Testing Galore

(Updated January 3, 2007)

(Updated January 3, 2007)

North Korea may have gotten all the attention, but all the nuclear weapon states were busy flight-testing ballistic missiles for their nuclear weapons during 2006. According to a preliminary count, eight countries launched more than 28 ballistic missiles of 23 types in 26 different events.

Unlike the failed North Korean Taepo Dong 2 launch, most other ballistic missile tests were successful. Russia and India also experienced missile failures, but the United States demonstrated a very reliable capability including the 117th consecutive successful launch of the Trident II D5 sea-launched ballistic missile.

The busy ballistic missile flight testing represents yet another double standard in international security, and suggests that initiatives are needed to limit not only proliferating countries from developing ballistic missiles but also find ways to curtail the programs of the existing nuclear powers.

The ballistic missile flight tests involved weapons ranging from 10-warhead intercontinental ballistic missiles down to single-warhead short-range ballistic missiles. Most of the flight tests, however, involved long-range ballistic missiles and the United States, Russia and France also launched sea-launched ballistic missiles (see table below).

|

Ballistic Missile Tests |

||

| Date | Missile | Remarks |

| China | ||

| 5 Sep | 1 DF-31 ICBM |

From Wuzhai, impact in Takla Makan Desert. |

| France | ||

| 9 Nov | 1 M51 SLBM | From Biscarosse (CELM facility), impact in South Atlantic. |

| India | ||

| 13 Jun | 1 Prithvi I SRBM |

From Chandipur, impact in Indian Ocean. |

| 9 Jul | 1 Agni III IRBM |

From Chandipur. Failed. |

| 20 Nov | 1 Prithvi I SRBM |

From Chandipur, impact in Indian Ocean. |

| Iran** | ||

| 23 May | 1 Shahab 3D MRBM |

From Emamshahr. |

| 3 Nov | 1 Shahab 3 MRBM, as well as “dozens” of Shahab 2, Scud B and other SRBMs |

Part of the Great Prophet 2 exercise. |

| North Korea*** | ||

| 4 Jul | 1 Taepo Dong 2 ICBM and 6 Scud C and Rodong SRBMs |

From Musudan-ri near Kalmo. ICBM failed. |

| Pakistan | ||

| 16 Nov | 1 Ghauri MRBM |

From Tilla? |

| 29 Nov | 1 Hatf-4 (Shaheen-I) SRBM |

Part of Strategic Missile Group exercise. |

| 9 Dec | 1 Haft-3 (Ghaznavi) SRBM |

Part of Strategic Missile Group exercise. |

| Russia | ||

| 28 Jul | 1 SS-18 ICBM | Attempt to launch satellite, but technically an SS-18 flight test (see comments below). |

| 3 Aug | 1 Topol (SS-25) ICBM |

From Plesetsk, impact on Kura range. |

| 7 Sep | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From Dmitry Donskoy (Typhoon) in White Sea. Failed. |

| 9 Sep | 1 SS-N-23 SLBM |

From K-84 (Delta IV) at North Pole, impact on Kizha range. |

| 10 Sep | 1 SS-N-18 SLBM |

From Delta III in Pacific, impact on Kizha range. |

| 25 Oct | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From Dmitry Donskoy (Typhoon) in White Sea. Failed. |

| 9 Nov | 1 SS-19 ICBM |

From Silo in Baykonur, impact on Kura range. |

| 21 Dec | 1 SS-18 ICBM |

From Orenburg, impact on Kura range. |

| 24 Dec | 1 Bulava SLBM |

From White Sea. Third stage failed. |

| United States | ||

| 16 Feb | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Final W87/Mk-21 SERV test flight. |

| Mar/Apr | 2 Trident II D5 SLBMs |

From SSBN. |

| 4 Apr | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact near Guam. Extended-range, single-warhead flight test. |

| 14 Jun | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Three-warhead payload. |

| 20 Jul | 1 Minuteman III ICBM |

From Vandenberg AFB, impact Kwajalein. Three-warhead flight test. Launched by E-6B TACAMO airborne command post. |

| 21 Nov | 2 Trident II D5 SLBMs |

From USS Maryland (SSBN-738) off Florida, impact in South Atlantic. |

| * Unreported events may add to the list. ** Iran does not have nuclear weapons but is suspected of pursuing nuclear weapons capability. *** It is unknown if North Korea has developed a nuclear reentry vehicle for its ballistic missiles. |

||

The Putin government’s reaffirmation of the importance of strategic nuclear forces to Russian national security was tainted by the failure of three consecutive launches of the new Bulava missile, but tests of five other missile types shows that Russia still has effective missile forces.

Along with China, Russia’s efforts continue to have an important influence on U.S. nuclear planning, and the eight Minuteman III and Trident II missiles launched in 2006 were intended to ensure a nuclear capability second to none. The first ICBM flight-test signaled the start of the deployment of the W87 warhead on the Minuteman III force.

China’s launch of the (very) long-awaited DF-31 ICBM and India’s attempts to test launch the Agni III raised new concerns because of the role the weapons likely will play in the two countries’ targeting of each other. But during a visit to India in June 2006, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Peter Pace, downplayed at least the Indian issue saying other countries in the region also have tested missiles. In a statement that North Korea would probably find useful to use, Gen. Pace explained that “the fact that a country is testing something like a missile is not destabilizing” as long as it is “designed for defense, and then are intended for use for defense, and they have competence in their ability to use those weapons for defense, it is a stabilizing event.”

But since all “defensive” ballistic missiles have very offensive capabilities, and since no nation plans it defense based on intentions and statements anyway but on the offensive capabilities of potential adversaries, Gen. Pace’s explanation seemed disingenuous and out of sync with the warnings about North Korean, Iranian and Chinese ballistic missile developments.

The Missile Technology Control Regime (MTCR) seeks to limit the proliferation of ballistic missiles, but that vision seems undercut by the busy ballistic missile launch schedule demonstrated by the nuclear weapon states in 2006. Some MTCR member countries have launched the International Code of Conduct Against Ballistic Missile Proliferation initiative in an attempt to establish a norm against ballistic missiles, and have called on all countries to show greater restraint in their own development of ballistic missiles capable of delivering weapons of mass destruction and to reduce their existing missile arsenals if possible.

All the nuclear weapons states portray their own nuclear ballistic missile developments as stabalizing and fully in compliance with their pledge under the Non-Proliferation Treaty to pursue nuclear disarmament in good faith. But fast-flying ballistic missiles are inherently destablizing because of their vulnerability to attack may trigger use early on in a conflict. And the busy missile testing in 2006 suggests that the “good faith” is wearing a little thin.

U.S. Nuclear Posture at a Crossroad, Defense Science Board Says

The Defense Science Board concludes in a new report that the United States has lost its “national consensus” on what the nation’s nuclear deterrent should look like and the role it should serve. The consensus has been replaced by an “entrenchment” of “sharp differences” of opinion. Therefore, urgent action is needed by the White House and senior leaders to “engage more directly to articulate the persuasive case” for how modern nuclear weapons serve U.S. national security policy.

U.S. nuclear policy has come to a crossroad because the current formula is no longer sustainable.

Perhaps not coincidently, the DSB report comes as the administration is preparing to persuade Congress to pay for a new nuclear weapons complex (Complex 2030) to resume production of nuclear weapons for the first since since the end of the Cold War. To that end, the report presents a wide range of recommendations for how to revitalize the U.S. nuclear posture.

Recommendations for nuclear weapons policy and forces include:

1. Leaders should declare “unequivocally and frequently” that nukes are still needed.

2. Establish a Red Team to look for nuclear enemies.

3. Establish a Deterrence Team to figure out how to better deter current and future adversaries.

4. The missile defense under construction is inadequate to deal with countermeasures and needs to be upgraded.

5. Accelerate development of “a credible Nuclear Leg of the Strike Triad.”

6. Figure out what to do with nuclear forces beyond the SORT treaty, but hedge (it is now called “remain reversible”) against negative developments in Russian and China.

7. Modernize the command and control system.

8. The Nuclear Weapons Council should establish a policy that no single warhead type makes up more than 20 percent of the deployed stockpile (i.e., the stockpile should consist of at least five different warhead types).

9. RRW-1, as the first Reliable Replacement Warhead prototype is called, should be a full weapons program.

Recommendations for the nuclear weapons production complex include:

1. Produce “a predetermined number of RRW-class warheads” per year by 2012.

2. Create a National Nuclear Weapons Agency to support Complex 2030.

3. Retain all three nuclear weapons labs.

4. The Secretary of Defense should figure out which is easier: sustain the current quantities and diversity of nuclear weapons or build new ones.

5. Create an Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategic Weapons with a Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear Weapons.

6. Get congressional approval to appoint the Deputy Secretary of Defense as the Nuclear Weapons Council and make the commander of STRATCOM a member of the Nuclear Weapons Council.

Yet Another RRW Vision?

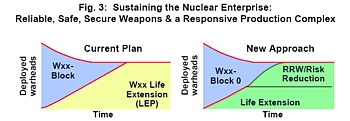

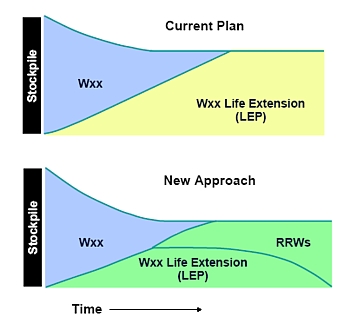

One of the surprises in the report is that the DSB seems to have a different long-term vision for the RRW than the administration. A drawing in the DSB report shows how the composition of nuclear warheads would change with the introduction of RRWs. The drawing a future mix of equal numbers of RRWs and existing life-extended warheads (see figure below).

|

DSB Stockpile Vision |

|

| The Defense Science Board report presents a nuclear stockpile vision that includes roughly equal numbers of the RRW and life-extended warheads. |

That vision is very different from the one presented by the Secretary of Energy, Secretary of Defense, and the Nuclear Weapons Council in their joint interim RRW report to Congress in March 2006. A drawing in that report showed a future mix of warheads where RRWs would replace all life-extended warhead types (see figure below).

|

DOD/DOE Stockpile Vision |

|

| The Department of Energy and Department of Defense vision for the nuclear stockpile includes a phaseout of all life-extended warheads leaving only RRWs. |

Analysis

The DSB report comes across as an attempt to “resell” the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review. It is a report on the defensive that suggests that critics of Cold War nuclear policy and excessive capabilities have had a considerable impact on U.S. nuclear policy and the mood inside the administration and Congress.

A major shortfall of the report is this: Despite lamenting that new thinking is urgently needed, the DSB report offers no new ideas for why it is necessary to revitalize the nuclear posture, except the arguments made in the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review and the 2004 DSB report on the future of strategic forces. Instead of defining the new agenda, the DSB report appears to be defending the current agenda.

This is perhaps not surprising considering that the entire DSB Task Force consisted of people from the nuclear labs, major defense contractors and conservative think tanks. Some were even the architects of the 2001 Nuclear Posture Review. All advisors are from the Pentagon, the nuclear agencies, and the nuclear labs. The DSB report’s primary conclusion is that new thinking is needed, but the list of participants and briefings received strongly suggests that no attempt was made to think “outside the box.”

The failure to involve others and new ideas is perhaps the worst enemy of U.S. nuclear policy, not to mention a disfavor to national and international security.

Background: Defense Science Report | US Nuclear Guidance

Britain’s Next Nuclear Era

After having spent the last several years sending diplomats to Teheran to try to persuade Iran not to develop nuclear weapons, the British government announced Monday that it plans to renew its own nuclear arsenal.

If approved by the parliament, Monday’s decision means that the United Kingdom will extend its nuclear deterrent beyond 2050, essentially doubling the timeline of its own nuclear era.

Doing so is entirely consistent with the United Kingdom’s international obligations under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and with a policy that favors complete elimination of nuclear weapons, the government insisted in a fact sheet, because the British nuclear arsenal today is smaller than during the Cold War, and because the Treaty does not say exactly when nuclear disarmament has to be accomplished. In fact, the new plan has “the right balance,” the government claims, between working for a world free of nuclear weapons and keeping those weapons.

The Reduction

Probably in acknowledgment that it will be a hard sell domestically and internationally, the $40 billion nuclear plan was sweetened with an announcement that Britain will reduce the number of “operationally available warheads” from fewer than 200 today to fewer than 160 at some future date.

The gesture is somewhat hollow, however, because Britain only has enough Trident D5 missiles to arm three of its four SSBNs with a maximum of 144 warheads anyway. The Blair government previously decided in 1998 to purchase only 58 missiles instead of 65. Since then, eight missiles have been used in operational test launches, leaving 50 missiles in the inventory – barely enough to fill the tubes of three SSBNs.

The British government has stated that the single SSBN on patrol at any given time carries “up to 48” warheads, a statement that partly reflects that some of the missiles have been given a “substrategic” mission, probably with only one warhead each. Depending on the number of substrategic mission missiles carried, the actual loading of the patrolling submarine probably is 36-44 warheads. Assuming a similar loading for the other two SSBNs for which there are missiles available, the estimated number of warheads needed for the British SSBN fleet since the substrategic mission first became operational in 1996 is 108-132 warheads.

The announcement to retain “fewer than 160” operationally available warheads seems to reflect this existing reality rather than an additional operational reduction. But it raises the question why the British government for the past eight years has retained 20 percent more warheads than it actually needed.

The Catch

The plan to replace the submarines comes with a catch: Half-way through their service-life, the missiles will expire, necessitating further investment to purchase new missiles and possibly also new warheads. The U.K. government has already received, the White Paper states, assurance from the U.S. government that Britain can be a partner if the United States later decides to build a successor to the D5 missile, and that such a missile will be compatible, or can be made compatible, with Britain’s new SSBNs.

The Warheads

The type of warhead deployed on Britain’s D5 missiles will last at least into the 2020, according to the White Paper. But the U.K. government says it doesn’t yet know whether the warhead can be “refurbished” to last longer, or whether it will be necessary to develop a replacement warhead. The next Parliament will have to make that decision, the government says, an option that of course will be harder to reject if a decision has already been made to build the new submarines.

How British are the warheads on the British SSBN fleet? The Ministry of Defence stated in a fact sheet that the warheads on the D5 missiles were “designed and manufactured in the U.K.” Even so, rumors have persisted for years that the warheads are in fact modified U.S. W76 warheads.

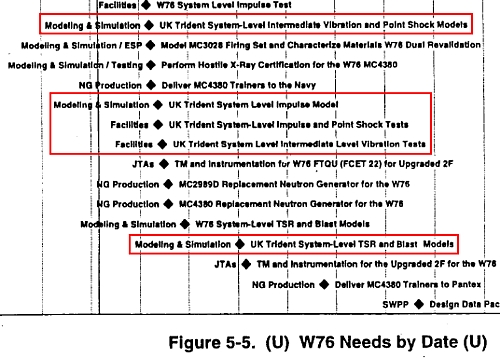

Now a U.S. Department of Energy document – declassified after eight years of processing – directly links the warhead designs on U.S. and U.K. Trident missiles. The document shows that the “U.K. Trident System,” as the British warhead modification is called, is similar enough to the U.S. W76 warhead to make up an integral part of the W76 engineering, design and evaluation schedule (see figure below).

|

How British is Britain’s Nuclear Warhead? |

|

| The British Trident warhead is similar enough to the U.S. W76 to form an integral part of the U.S. Department of Energy’s “W76 Needs” schedule, according to this document declassified and released under the Freedom of Information Act. The document directly links the warhead designs on U.S. and U.K. Trident missiles. To download a PDF-copy of the declassified document, click here. |

Specifically, the document shows that between 1999 and 2001, work on five of 13 “W76 needs” involved the “U.K. Trident System.” These activities included vibration and point shock models, impulse models, impulse and point shock tests, vibration tests, as well as “TSR [thermostructural response] and Blast Models.”

The activities listed in the chronology are contained in a detailed database that “maps the requirements and capabilities for replacement subsystem and component modeling development, test, and production to the specific organizations tasked with meeting these requirements.”

The “U.K. Trident System” is thought to consist of a 100-kiloton thermonuclear warhead encased in a cone-shaped U.S. Mark-4 reentry vehicle. The W76 is the most numerous warhead (approximately 3,200) in the U.S. stockpile. Built between 1978 and 1988, about a third of the W76s are being modified as the W76-1 (see figure below) and equipped with a new fuze with ground-burst capability to “enable the W76 to take advantage of the higher accuracy of the D5” against harder targets. Delivery of the first W76-1 is scheduled for 2007 and the last in 2012. The W76 is also the first warhead scheduled to be modified under the proposed Reliable Replacement Warhead program.

|

The W76 |

|

| This is believed to be the first publicly available picture of the W76. It shows the four First Production Units of the modified W76-1/Mk4A reentry vehicle. The British version of the W76 probably looks similar. Source: Sandia National Laboratories. |

The Nuclear Mission

The U.K. government presents several specific military and political justifications for why it intends to double Britain’s nuclear era.

One is that none of the other nuclear weapon states are even considering getting rid of their nuclear weapons, but instead are modernizing – some even increasing – their nuclear arsenals.

Another justification is that North Korea and Iran are pursuing nuclear weapons too, and that some countries might even “sponsor nuclear terrorism from their soil.”

Finally, the world is an uncertain and risky place, the White Paper concludes, and adds that it is “not possible to accurately predict the global security environment over the next 20 to 50 years.”

Those who question that these justifications are sufficient to retain the nuclear deterrent, Prime Minister Tony Blair writes in the foreword of the White Paper, “need to explain why disarmament by the U.K. would help our security.”

Analysis

The White Paper fails to identify a specific, urgent mission for British nuclear weapons. Instead, the justification to keep them seems like a little of everything: A couple of Cold War leftovers (Russia is still looming on the horizon and China might rise), a little sheep mentality (the other nuclear powers won’t give them up either), a little mission-creep (we might have to use them against proliferators), and a little hype (a role against terrorists). All of this is wrapped in the popular post-Cold War mantra that claims that the world suddenly is very uncertain and impossible to predict. As Prime Minister Tony Blair told the Parliament Monday:

“It is just that, in the final analysis, the risk of giving up something that has been one of the mainstrays of our security since the war [World War II], and moreover doing so when the one certain thing about our world today is its uncertainty, is not a risk I feel we can reasonably take.” The world has changed “beyond recognition,” and “it is precisely because we could not have recognized then, the world we live in now, that it would not be wise to predict the unpredictable in the times to come.”

Of course, it is one thing to argue that Britain needs a nuclear bomb in the basement or a mothballed nuclear production capability just in case. It is quite another to claim that strategic submarines need to continue to hide deep in the oceans much like they did during the Cold War without an urgent threat against the survival of the nation.

That’s for the U.K. Parliament to debate in the next months, followed – presumably – by a decision whether to approve the government’s plan sometime in 2007.

Background: MOD White Paper and Fact Sheets | British Nuclear Forces, 2005