Rumors About Nuclear Weapons in Crimea

The news media and private web sites are full of rumors that Russia has deployed nuclear weapons to Crimea after it invaded the region earlier this year. Many of these rumors are dubious and overly alarmist and ignore that a nuclear-capable weapon is not the same as a nuclear warhead.

Several U.S. lawmakers who oppose nuclear arms control use the Crimean deployment to argue against further reductions of nuclear weapons. NATO’s top commander, U.S. General Philip Breedlove, has confirmed that Russian forces “capable of being nuclear” are being moved to the Crimean Peninsula, but also acknowledged that NATO doesn’t know if nuclear warheads are actually in place.

Recently Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Alexei Meshkov said that NATO was “transferring aircraft capable of carrying nuclear arms to the Baltic states,” and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov reminded that Russia has the right to deploy nuclear weapons anywhere on its territory, including in newly annexed Crimea.

Whether intended or not, non-strategic nuclear weapons are already being drawn into the new East-West crisis.

What’s New?

First a reminder: the presence of Russian dual-capable non-strategic nuclear forces in Crimea is not new; they have been there for decades. They were there before the breakup of the Soviet Union, they have been there for the past two decades, and they are there now.

In Soviet times, this included nuclear-capable warships and submarines, bombers, army weapons, and air-defense systems. Since then, the nuclear warheads for those systems were withdrawn to storage sites inside Russia. Nearly all of the air force, army, and air-defense weapon systems were also withdrawn. Only naval nuclear-capable forces associated with the Black Sea Fleet area of Sevastopol stayed, although at reduced levels.

Yet with the Russian invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea, a military reinforcement of military facilities across the peninsula has begun. This includes deployment of mainly conventional forces but also some systems that are considered nuclear-capable.

Naval Nuclear-Capable Forces

The Russian Black Sea Fleet in Sevastopol includes nuclear-capable cruisers, destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and submarines. They are capable of carrying nuclear cruise missiles and torpedoes. But the warheads for those weapons are thought to be in central storage in Russia.

A nuclear-capable SS-N-12 cruise missile is loaded into one of the 16 launchers on the Slava-class cruiser in Sevastopol (top). In another part of the harbor, a nuclear-capable SS-N-22 cruise missile is loaded into one of eight launchers on a Dergach-class corvette (insert).

There are several munitions storage facilities in the Sevastopol area but none seem to have the security features required for storage of nuclear weapons. The nearest national-level nuclear weapons storage site is Belgorod-22, some 690 kilometers to the north on the other side of Ukraine.

Backfire Bombers

There is a rumor going around that president Putin last summer ordered deployment of intermediate-range Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers to Crimea.

Rumors say that Russia plans to deploy Tu-22M3 intermediate-range bombers (see here with two AS-4 nuclear-capable cruise missiles) to Crimea.

One U.S. lawmaker claimed in September that Putin had made an announcement on August 14, 2014. But even before that, shortly after Russia invaded Ukraine in March and annexed Crimea, Jane’s Defence Weekly quoted a Russian defense spokesperson describing plans to deploy Backfires to Gvardiesky (Gvardeyskoye) along with Tu-142 and Il-38 in 2016 after upgrading the base. Doing so would require major upgrades to the base.

Russia appears to have four operational Backfire bases: Olenegorsk Air Base on the Kola Peninsula (all naval aviation is now under the tactical air force) and Shaykovka Air Base near Kirov in Kaluzhskaya Oblast near Belarus in the Western Military District (many of the Backfires intercepted over the Baltic Sea in recent months have been from Shaykovka); Belaya in Irkutsk Oblast in the Central Military District; and Alekseyevka near Mongokhto in Khabarovsk Oblast in the Eastern Military District. A fifth base – Soltsy Air Base in Novgorod Oblast in the Western Military District – is thought to have been disbanded.

The apparent plan to deploy Backfires in Crimea is kind of strange because the intermediate-range bomber doesn’t need to be deployed in Crimea to be able to reach potential targets in Western Europe. Another potential mission could be for maritime strikes in the Black Sea and Mediterranean Sea, but deployment to Crimea will only give it slightly more reach in the southern and western parts of the Mediterranean Sea (see map below). And the forward deployment would make the aircraft much more vulnerable to attack.

Deployment of Tu-22M3 Backfire bombers to Crimea would increase strike coverage of the southern parts of the Mediterranean Sea some compared with Backfires currently deployed at Shaykovka Air Base, but it would not provide additional reach of Western Europe.

Iskander Missile Launchers

Another nuclear-capable weapon system rumored to be deployed or deploying to Crimea is the Iskander-M short-range ballistic missile. Some of the sources that mention Backfire bomber deployment also mention the Iskander.

One of the popular sources of the Iskander rumor is an amateur video allegedly showing Russian military vehicles rolling through Sevastopol on May 2, 2014. The video caption posted on youtube.com specifically identified “Iskander missiles” as part of the column.

An amateur video posted on youtube reported Iskander ballistic missile launchers rolling through downtown Sevastopol. A closer look reveals that they were not Islander. Click image to view video.

A closer study of the video, however, reveals that the vehicles identified to be launchers for “Iskander missiles” are in fact launchers for the Bastion-P (K300P or SSC-5) costal defense cruise missile system. The Iskander-M and Bastion-P launchers look similar but the cruise missile canisters are longer, so the give-away is that the rear end of the enclosed missile compartments on the vehicles in the video extend further back beyond the fourth axle than is that case on an Iskander-M launcher.

While the video does not appear to show Iskander, Major General Alexander Rozmaznin of the General Staff of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, reportedly stated that a “division” of Iskander had entered Crimea and that “every missile system is capable of carrying nuclear warheads…”

The commander of Russia’s strategic missile forces, Colonel General Sergei Karakayev, recently ruled out rumors about deployment of strategic missiles in Crimea, but future plans for the Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles in Crimea are less clear.

Russia is currently upgrading short-range ballistic missile brigades from the SS-21 (Tochka) to the SS-26 (Iskander-M) missile. Four of ten brigades have been upgraded or are in the process of upgrading (all in the western and southern military districts), and a fifth brigade will receive the Iskander in late-2014. In 2015, deployment will broaden to the Central and Eastern military districts.

The Iskander division closest to Crimea is based near Molkino in the Krasnodar Oblast. So for the reports about deployment of an Iskander division to Crimea to be correct, it would require a significant change in the existing Iskander posture. That makes me a little skeptical about the rumors; perhaps only a few launchers were deployed on an exercise or perhaps people are confusing the Iskander-M and the Bastion-P. We’ll have to wait for more solid information.

Air Defense

As a result of the 1991-1992 Presidential Nuclear Initiatives, roughly 60 percent of the Soviet-era inventory of warheads for air defense forces has been eliminated. The 40 percent that remains, however, indicates that Russian air defense forces such as the S-300 still have an important secondary nuclear mission.

The Ukrainian military operated several S-300 sites on Crimea, but they were all vacated when Russia annexed the region in March 2014. The Russian military has stated that it plans to deploy a complete integrated air defense system in Crimea, so some of the former Ukrainian sites may be re-populated in the future.

Just as quickly as the Ukrainian S-300 sites were vacated, however, two Russian S-300 units moved into the Gvardiesky Air Base. A satellite image taken on March 3, 2014, shows no launchers, but an image taken 20 days later shows two S-300 units deployed.

Two S-300 air defense units were deployed to Gvardiesky Air Base immediately after the Russian annexation of Crimea. The Russian Air Force moved Su-27 Flanker fighters in while retaining Su-24 Fencers (some of which are not operational). Click image to see full size.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Russia has had nuclear-capable forces deployed in Crimea for many decades but rumors are increasing that more are coming.

The Russian Black Sea Fleet already has many types of ships and submarines capable of carrying nuclear cruise missiles and torpedoes. More ships are said to be on their way.

Rumors about future deployment of Backfire bombers to Crimea would, if true, be a significant new development, but it would not provide significant new reach compared with existing Backfire bases. And forward-deploying the intermediate-range bombers to Crimea would increase their vulnerability to potential attack.

Some are saying Iskander-M short-range ballistic missiles have been deployed, but no hard evidence has been presented and at least one amateur video said to show “Iskander missiles” instead appears to show a coastal missile defense system.

New air-defense missile units that may have nuclear capability are visible on satellite images.

It is doubtful that the nuclear-capable forces currently in Crimea are equipped with nuclear warheads. Their dual-capable missiles are thought to serve conventional missions and their nuclear warheads stored in central storage facilities in Russia.

Yet the rumors are creating uncertainty and anxiety in neighboring countries – especially when seen in context with the increasing Russian air-operations over the Baltic Sea and other areas – and fuel threat perceptions and (ironically) opposition to further reductions of nuclear weapons.

The uncertainty about what’s being moved to Crimea and what’s stored there illustrates the special problem with non-strategic nuclear forces: because they tend to be dual-capable and serve both nuclear and conventional roles, a conventional deployment can quickly be misinterpreted as a nuclear signal or escalation whether intended or real or not.

The uncertainty about the Crimea situation is similar (although with important differences) to the uncertainty about NATO’s temporary rotational deployments of nuclear-capable fighter-bombers to the Baltic States, Poland, and Romania. Russian officials are now using these deployments to rebuff NATO’s critique of Russian operations.

This shows that non-strategic nuclear weapons are already being drawn into the current tit-for-tat action-reaction posturing, whether intended or not. Both sides of the crisis need to be particularly careful and clear about what they signal when they deploy dual-capable forces. Otherwise the deployment can be misinterpreted and lead to exaggerated threat perceptions. It is not enough to hunker down; someone has to begin to try to resolve this crisis. Increasing transparency of non-strategic nuclear force deployments – especially when they are not intended as a nuclear signal – would be a good way to start.

Additional information: report about U.S. and Russian non-strategic nuclear forces

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Polish F-16s In NATO Nuclear Exercise In Italy

NATO is currently conducting a nuclear strike exercise in northern Italy.

The exercise, known as Steadfast Noon 2014, practices employment of U.S. nuclear bombs deployed in Europe and includes aircraft from seven NATO countries: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Turkey, and United States.

The timing of the exercise, which is held at the Ghedi Torre Air base in northern Italy, coincides with East-West relations having reached the lowest level in two decades and in danger of deteriorating further.

It is believed to be the first time that Poland has participated with F-16s in a NATO nuclear strike exercise.

Coinciding with the Steadfast Noon exercise, NATO is also conducting a Strike Evaluation (STRIKEVAL) nuclear certification inspection at Ghedi.

A nuclear security exercise was conducted at Ghedi Torre AB in January 2014, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of U.S. nuclear weapons deployment at the base.

Steadfast Noon/STRIKEVAL is the second nuclear weapons strike exercise in Italy in two years, following Steadfast Noon held at Aviano AB in 2013.

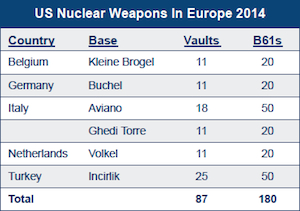

Italy hosts 70 of the 180 U.S. nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

The Role of Polish F-16s

The participation of Polish F-16s in a NATO nuclear strike exercise is noteworthy because Polish F-16s are not thought to be capable of delivery nuclear weapons or assigned nuclear strike missions under NATO or U.S. nuclear planning.

The two Polish F-16s that have been photographed at Ghedi Torre Air Base are from the 10th Tactical Squadron (ELT) of the 32nd Wing (BL) at Lask Air Base in western Poland. (Another source reported three Polish F-16s).

If Polish F-16s were directly involved in NATO nuclear strike planning, it would be a significant new development. NATO officially adheres to its “three no’s” policy, first adopted by the alliance in December 1996, according to which “NATO countries have no intention, no plan, and no reason to deploy nuclear weapons on the territory of new members nor any need to change any aspect of NATO’s nuclear posture or nuclear policy – and we do not foresee any future need to do so.” (Emphasis added).

Since then, NATO has in fact changed the posture several times, although not eastward: In 2001, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from Araxos AB earmarked for use by Greek aircraft; and later also withdrawing Incirlik AB weapons that during the first part of the W Bush administration were intended for use by Turkish aircraft (weapons for U.S. aircraft are still present at Incirlik); in 2002, by reducing the readiness level of nuclear aircraft from weeks to months; in 2003, by Germany closing Memmingen AB; in 2005, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from Ramstein AB in Germany; and in 2007, by withdrawing nuclear weapons from England. Overall, these changes have resulted in a unilateral reduction of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe by 62 percent since the “three no’s” policy was adopted in 1996, from 480 to 180 today.

The Deterrence and Defense Posture Review (DDPR) approved by NATO in 2012 determined that the remaining “nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defence posture.” And when asked in May 2014 if the Ukraine crisis would lead NATO to reconsider its pledge not to place nuclear weapons on the territory of new member states, then-NATO General Secretary Rasmussen said no: “At this stage, I do not foresee any NATO request to change the content of the NATO-Russia founding act.”

The 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act Agreement reference by Rasmussen echoed the 1996 policy but further explained that the three no’s policy “subsumes the fact that NATO has decided that it has no intention, no plan, and no reason to establish nuclear weapon storage sites on the territory of those members, whether through the construction of new nuclear storage facilities or the adaptation of old nuclear storage facilities. Nuclear storage sites are understood to be facilities specifically designed for the stationing of nuclear weapons, and include all types of hardened above or below ground facilities (storage bunkers or vaults) designed for storing nuclear weapons.” (Emphasis added).

The 1997 Founding Act language clearly seems more focused on storage facilities rather than other parts of the posture, such as aircraft or command and control facilities that could support the nuclear mission.

Lask AB As Nuclear Staging Base?

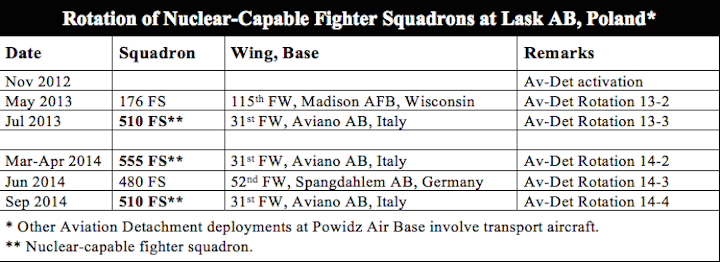

The participation of Polish F-16s from Lask AB in a NATO nuclear exercise is also interesting because the base is the primary base used by NATO aircraft deploying to Poland on temporary rotational deployments under a bilateral U.S. –Polish reinforcement treaty. Some of the U.S. squadrons that have deployed to Lask AB since 2012 are nuclear-capable.

In 2011, Poland and the United States signed an agreement to deploy a permanent U.S. Air Force aviation detachment (AV-DET) to Poland. The detachment organized under the 52nd Operations Group at Spangdahlem AB in Germany, which is also the home of the 52nd Munitions Maintenance Group that oversees the operations of the four MUNSS units deployed in four of the five western NATO countries that host U.S. nuclear weapons on their territory.

The Role of Polish F-16s

Since Polish F-16s are not nuclear-capable or assigned nuclear strike missions under U.S. and NATO strike planning, the aircraft participating in the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL exercise instead are thought to serve other non-nuclear roles.

One role might be air-defense or suppression of ground-based radars. A nuclear strike would not only involve the aircraft carrying the nuclear weapon but also support aircraft to protect the strike package.

It is also potentially possible that participation of Polish F-16s reflects that NATO is working on increasing the role of conventional forces in Article V missions. The Obama administration’s nuclear employment strategy from June 2013 directed the U.S. military to “assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options” to reduce the role of nuclear weapons.

Poland is planning to equip its F-16s with the U.S.-produced Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missiles (JASSM), a new highly accurate standoff missile that was recently approved for sale to Poland.

The U.S. Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCS) claims that Poland’s acquisition of the JASSM “will not alter the basic military balance in the region,” but the sale of the weapon to Poland (and other European countries such as Finland) in fact seems likely to do so anyway.

The only standoff weapon currently on Polish F-16s is the 23-kilometer (13 miles) range Maverick (AGM-65) [update: as several readers have pointed out (see comments below), a number of other weapons are also available]; the JASSM, in contrast, will be able to hold at risk targets at more than ten times that range with greater accuracy. Moreover, while Maverick has an optical guidance, the JASSM has all-weather GPS guidance. The JASSM is “designed to destroy high-value, well-defended, fixed and relocateable targets.” The “significant standoff range” of more than 370 kilometers (230 miles) and jam resistant GPS-guided “pinpoint accuracy,” according to Lockheed Martin, means that JASSM’s “mission effectiveness approaches a single missile required to destroy a target.”

The Pentagon says Poland’s acquisition of the JASSM missile, seen here flying through a target hole in a test, “will not alter the basic military balance” in Eastern Europe.

DSCA anticipates that Poland will use the “enhanced capability [of the JASSM] as a deterrent to regional threats and to strengthen its homeland defense.” The JASSMs and associated aircraft upgrades, according to DSCA, “will allow Poland to strengthen its air-to-ground strike capabilities and increase its contribution to future NATO operations.”

Integration of weapons such as JASSM into NATO’s posture would seem to fit well with the U.S. goal to reduce the role of nuclear weapons by providing increased conventional target destruction capability backed by a strategic nuclear deterrent that “supports our ability to project power by communicating to potential nuclear-armed adversaries that they cannot escalate their way out of failed conventional aggression,” as stated in the 2014 Quadrennial Defense Review. A total of 5,000 JASSMs are planned.

Lask AB is located only 286 kilometers (178 miles) from the Belarusian border and 324 kilometer (201 miles) from the Russian border in Kaliningrad Oblast. At a speed of 1,800 kilometers per hour (1,119 miles/hour, or Mach 1.47), an F-16 launched from Lask AB would be able to reach Kaliningrad in 12 minutes and Moscow in less than an hour.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Although the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL nuclear exercise has been planned for a couple of years, the timing is delicate, to say the least, because of deteriorating East-West relations following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine earlier this year. Russian and NATO exercises have combined to fuel a perception of a crisis that goes well beyond words to increased military posturing on both sides, reminiscent of mindsets we haven’t seen in Europe since the 1980s.

Under these conditions, there is a real risk that the tactical nuclear strike exercise at Ghedi AB with participation of Polish F-16s could feed into Russian paranoia about NATO’s military intensions. A comparable operation would be if Russia were to conduct nuclear air-strike exercises to reassure Belarus. That would deepen paranoia in eastern NATO countries and could give tactical nuclear forces in Europe a prominence that is not in anyone’s interest.

Both sides need to calm their military operations and focus on rebuilding normal relations. For Russia, that means pulling back forces from Ukrainian and NATO borders and end provocative aircraft operations near or into NATO (and Swedish and Finnish) airspace.

For NATO, that means explaining Poland’s role in the Steadfast Noon-STRIKEVAL nuclear strike exercise and the rotational deployments of U.S. nuclear-capable fighter-squadrons to Lask AB in the context of the “three no’s” policy. And it requires ensuring that reassurance of Eastern European allies does not result in conventional modernization programs or operations that deepen Russian paranoia.

Credit: Thanks to Roel Stynen of Vredesactie for first alerting me to the NATO exercise.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

President’s Message: The Nuclear Guns of August

“One constant among the elements of 1914—as of any era—was the disposition of everyone on all sides not to prepare for the harder alternative, not to act upon what they suspected to be true,” wrote Barbara Tuchman in The Guns of August.1 Today, the United States and other nuclear-armed states are not addressing the harder alternative of whether nuclear weapons provide for real security. The harder alternative, I argue, is to work toward elimination of these weapons at the same time as the security concerns of all states are being met. If leaders of states feel insecure, those with nuclear arms will insist on maintaining or even modernizing these weapons, and many of those without nuclear arms will insist on having nuclear deterrence commitments from nuclear-armed states. Therefore, security concerns must be addressed as a leading priority if there is to be any hope of nuclear abolition.

Among the many merits of Tuchman’s book is her trenchant analysis of the entangled military and political alliances that avalanched toward the armed clashes at the start of the First World War in August 1914. The German army under the Schlieffen Plan had to mobilize within a couple of weeks and launch its attack through neutral Belgium into France and win swift victory; otherwise, Germany would get bogged down in a two-front war in France and Russia. But this plan did not go like clockwork. As we know from history, years of trench warfare resulted in millions of soldiers killed. The war’s death toll of military and civilians from multiple causes (including pandemic influenza) was more than 16 million.

The danger today is that alliance commitments could drag the United States into an even more costly nuclear war. While the United States must support its allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and in East Asia (including Japan and South Korea), it must be wary of overreliance on nuclear weapons for providing security. This is an extremely difficult balancing act. On the one hand, the United States needs to reassure these allies that they have serious, reliable extended deterrence commitments. “Extended” means that the United States extends deterrence beyond its territory and will commit to retaliating in response to an armed attack on an ally’s territory. Such deterrence involves conventional and nuclear forces as well as diplomatic efforts.

NATO allies have been concerned about the security implications of Russia’s incursion into Crimea and its influence over the continuing political and military crisis in Ukraine. Do nuclear weapons have a role in reassuring these allies? A resolute yes has come from an August 17th op-ed in the Washington Post by Brent Scowcroft, Stephen J. Hadley, and Franklin Miller.2 (The first two gentlemen served as national security advisers in the Ford, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush administrations while the third author was a senior official in charge of developing nuclear policy for Presidents George W. Bush and Bill Clinton.) Not only do these experienced former national security officials give an emphatic affirmation to the United States recommitting to nuclear deterrence in NATO (as if that were seriously in doubt), but they underscore the perceived need for keeping “the modest number of U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe.” The United States is the only nuclear-armed state to deploy nuclear weapons in other states’ territories.

The authors pose three arguments from opponents and then attempt to knock them down. First, the critics allegedly posit that NATO-based nuclear weapons “have no military value.” To rebut, Scowcroft et al. state that because NATO’s supreme allied commander says that these weapons have military value, this is evidence enough. While by definition of his rank he is an authority, he alone cannot determine whether or not these weapons have military value. This is at least a debatable point. Scowcroft et al. instead want to emphasize that the weapons are “fundamentally, political weapons.” That is, these forward deployed arms are “a visible symbol to friend and potential foe of the U.S. commitment to defend NATO with all of the military power it possesses.” But would the United States go so far as to threaten Russia with nuclear use? The authors do not pursue this line of questioning. Perhaps they realize that this threat could lead to a commitment trap in which the United States would risk losing credibility because it would not want to cross the nuclear threshold, but Russian President Vladimir Putin could call the U.S. bluff.3

The United States can still demonstrate resolve and commitment to allies with its strategic nuclear weapons based on U.S. soil and on submarines under the surfaces of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Moreover, the United States can show further support by working with European allies to make them more resilient against disruptions of energy supplies such as oil and natural gas from Russia. By implementing policies to reduce and eventually eliminate dependencies on Russian energy supplies, these countries will strengthen their energy security and have further options to apply economic and diplomatic pressure, if necessary, on Russia. These measures are not explicitly mentioned in the op-ed.

Rather, Scowcroft et al. argue that Russia has been modernizing its nuclear forces because these weapons “clearly matter to Russian leadership, and as a result, our allies insist that the U.S. nuclear commitment to NATO cannot be called into question.” But of course, these weapons are valuable to Russia due to the relative weakness of its conventional military. While Scowcroft et al. raise an important concern about continued modernization of nuclear weapons, this argument does not lead to the necessity of deployment of U.S. nuclear bombs in European states.

Scowcroft et al. then argue that NATO’s overwhelming conventional military superiority in the aggregate of all its allies’ conventional forces is a fallacy because it “masks the reality that on NATO’s eastern borders, on a regular basis, Russian forces are numerically superior to those of the alliance.” Moreover, “Russia’s armed forces have improved significantly since their poor performance in [the Republic of] Georgia in 2008.” The authors then state that looking at conventional war-fighting capabilities alone miss the point that “NATO’s principal goal is deterring aggression rather than having to defeat it. And it is here that NATO’s nuclear capabilities provide their greatest value.” Although I have no argument against deterring aggression, they have not proved the point that forward-deployed U.S. nuclear weapons have done so. Indeed, Russian forces have occupied parts of Ukraine. While Ukraine is not part of NATO, it is still not proven that U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe are essential to block Russia from potentially encroaching on NATO allies in Eastern Europe. Perhaps at best nuclear forces on either side have stalemated each other and that there are still plenty of moves available for less potent, but nonetheless powerful, conventional forces on the geopolitical chessboard.

Finally, they address the opponents’ argument that deep divisions run through NATO allies about the presence of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe. While they acknowledge that in 2007 and 2008 domestic politics in several alliance states fed a debate that resulted in several government officials in some European states expressing interest in removal of U.S. nuclear weapons, they argue that the 2010 NATO Strategic Concept (endorsed by all 28 NATO heads of government), demonstrates unity of policy that “We will maintain an appropriate mix of nuclear and conventional forces [and] ensure the broadest participation of Allies in collective defense planning on nuclear roles, in peacetime basing of nuclear forces, and in command, control, and communications arrangements.” Of course, one can read into this statement that “broadest participation” and “peacetime basing” can suggest forward deployment. On the other hand, the statement can be read as purposively ambiguous to iron over differences and achieve consensus among a large group of states. These governments have yet to seriously question nuclear deterrence, but this does not demand forward basing of U.S. nuclear bombs.

Left unwritten in their op-ed are the steps the United States took at the end of the Cold War to remove its nuclear weapons from forward basing in South Korea and near Japan. Although some scholars and politicians in Japan and South Korea have at times questioned this action, the United States has frequently reassured these allies by flying nuclear-capable B-2 and B-52 strategic bombers from the United States to Northeast Asia and emphasizing the continuous deployment of dozens of nuclear-armed submarine launched ballistic missiles in the Pacific Ocean. Japan and South Korea have not built nuclear weapons, and they have not experienced war in the region since the Korean War ended in 1953 in an armistice. It would be a mistake for the United States to reintroduce forward-deployed nuclear weapons in and near Japan and South Korea. These allies’ security would not be increased and might actually decrease because of the potential for adverse reactions from China and North Korea.

The urgent required action is for the United States to stop being the only country with nuclear weapons deployed in other countries, and instead it should remove its nuclear bombs from European states. The United States should not give other countries such as China, Russia, or Pakistan the green light to forward deploy in others’ territories. For example, there are concerns that Pakistan could deploy nuclear forces in Saudi Arabia if Saudi rulers make such a request because of their fears of a future nuclear-armed Iran.

In conclusion, ideas in books do matter. President John F. Kennedy during the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis drew lessons from The Guns of August. The main lesson he learned was that great powers slipped accidentally into the catastrophic First World War. This sobering lesson in part made him wary of tripping into an accidental war, but he still took risks, for example, by ordering a naval quarantine of Cuba. (He called this action “quarantine” because a blockade is an act of war.) During the quarantine, it was fortunate that a Soviet submarine commander refrained from launching nuclear weapons that were onboard his submarine. This is just one example of how close the United States and Soviet Union came to nuclear war.

Let us remember that the crisis was largely about the United States’ refusal to accept the presence of Soviet nuclear weapons in Cuba that was within 100 miles of the continental United States. At that time, the United States had deployed nuclear-capable Jupiter missiles in Turkey, which bordered the Soviet Union. Both sides backed down from the nuclear brink, and both countries removed their forward deployed nuclear weapons from Cuba and Turkey. Thus, it is ironic that we seem to be headed back to the future when senior former U.S. officials argue for U.S. nuclear bombs based in Europe.

Charles D. Ferguson, Ph.D.

President, Federation of American Scientists

Italy’s Nuclear Anniversary: Fake Reassurance For a King’s Ransom

A new placard at Ghedi Air Base implies that U.S. nuclear weapons stored at the base have protected “the free nations of the world” after the end of the Cold War. But where is the evidence?

By Hans M. Kristensen

In December 1963, a shipment of U.S. nuclear bombs arrived at Ghedi Torre Air Base in northern Italy. Today, half a century later, the U.S. Air Force still deploys nuclear bombs at the base.

The U.S.-Italian nuclear collaboration was celebrated at the base in January. A placard credited the nuclear “NATO mission” at Ghedi with having “protected the free nations of the world….”

That might have been the case during the Cold War when NATO was faced with an imminent threat from the Soviet Union. But half of the nuclear tenure at Ghedi has been after the end of the Cold War with no imminent threat that requires forward deployment of nuclear weapons in Europe.

Instead, the nuclear NATO mission now appears to be a financial and political burden to NATO that robs its armed forces of money and time better spent on non-nuclear missions, muddles NATO’s nuclear arms control message, and provides fake reassurance to eastern NATO allies.

Italian Nuclear Anniversary

Neither the U.S. nor Italian government will confirm that there are nuclear weapons at Ghedi Torre Air Base. The anniversary placard doesn’t even include the word “nuclear” but instead vaguely refers to the “NATO mission.”

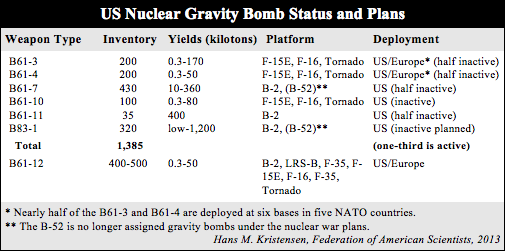

But there are numerous tell signs. One of the biggest is the presence of the 704th Munitions Support Squadron (MUNSS), a U.S. Air Force unit of approximately 134 personnel that is tasked with protecting and maintaining the 20 U.S. B61 nuclear bombs at the base. The MUNSS would not be at the base unless there were nuclear weapons present. There are only four MUNSS units in the U.S. Air Force and they’re all deployed at the four European bases where U.S. nuclear weapons are earmarked for delivery by aircraft of the host nation.

A satellite photo from March this year shows part of the nuclear infrastructure at Ghedi Torre Air Base. Click on image to see full size.

Another tell sign is the presence of NATO Weapons Maintenance Trucks (WMT) at Ghedi. NATO has 12 of these trucks that are specially designed to enable field service of nuclear bombs at the storage bases in Europe. A satellite image provided by Digital Globe via Google Earth shows a WMT parked near the 704th MUNSS quarters at Ghedi on March 12, 2014. An older image from September 28, 2009, shows two WMTs at the same location (see image above).

These trucks will drive out to the 11 individual Protective Aircraft Shelters (PAS) that are equipped with underground Weapons Storage and Security System (WS3) vaults to service the B61 bombs. The WS3 vaults at Ghedi were completed in 1997; before that the weapons were stored in bunkers outside the main base. Once the truck is inside the shelter, the B61 is brought up from the vault, disassembled into its main sections as needed, and brought into the truck for service.

It is during this process of weapon disassembly when the electrical exclusion regions of the nuclear bomb are breached that a U.S. Air Force safety review in 1997 warned that “nuclear detonation may occur” if lightning strikes the shelter.

NATO is in the process of replacing the WMTs with a fleet of new nuclear weapons maintenance trucks known as the Secure Transportable Maintenance System (STMS). The trailers will have improved lightning protection. NATO provided $14.7 million for the program in 2011, and in July 2012 the U.S. Air Force awarded a $12 million contract to five companies in the United States to build 10 new STMS trailers for delivery by June 2014.

NATO’s new mobile nuclear weapons maintenance system is scheduled for delivery to European nuclear bases in 2014. Click image to see full size.

The new trailers will be able to handle the new B61-12 guided standoff nuclear bomb that is planned for deployment in Europe from 2020. The B61-12 apparently will be approximately 100 lbs pounds (~45 kilograms) heavier than the existing B61s in Europe (see slide below) – even without the internal parachute. This suggests that a fair amount of new or modified components will be added. To better handle the heavier B61-12, each trailer will be equipped with hoist rails.

The new B61-12 bomb will be heavier than the B61s currently deployed in Europe. For pictures of actual B61-12 features, click here.

The deployment to Ghedi 50 years ago was not the earliest or only deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons to Italy. During the Cold War, ten different U.S. nuclear weapon systems were deployed to Italy. The first weapons to arrive were Corporal and Honest John short-range ballistic missiles in August 1956. They were followed by nuclear bombs in April 1957 and nuclear land mines in 1959. All but one – nuclear bombs – of these nuclear weapon systems have since been withdrawn and scrapped.

A decade ago, most B61s in Europe were stored in Germany and the United Kingdom, but today, Italy has the honor of being the NATO country with the most U.S. nuclear weapons deployed on its territory; a total of 70 of all the 180 B61 bombs remaining in Europe (39 percent). Italy is also the only country with two nuclear bases: the Italian base at Ghedi and the American base at Aviano. Aviano Air Base is home to the U.S. 31st Fighter Wing with two squadrons of nuclear-capable F-16 fighter-bombers. One of these, the 555th Fighter Squadron, was temporarily forward deployed to Lask Air Base in Poland in March 2014.

The nuclear “NATO mission” that the 6th Stormo wing at Ghedi Torre Air Base serves means that Italian Tornado aircraft are equipped and Italian Tornado pilots are trained in peacetime to deliver U.S. nuclear weapons in wartime. This arrangement dates back to before the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), but it is increasingly controversial because Italy as a signatory to the NPT has pledged “not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons…or of control over such weapons…directly, or indirectly.”

The United States, also a signatory to the NPT, has committed “not to transfer to any recipient whatsoever nuclear weapons…or control over such weapons…directly, or indirectly; and not in any way to assist, encourage, or induce any non-nuclear-weapon State to…acquire nuclear weapons…, or control over such weapons….”

In peacetime, the B61 nuclear bombs at Ghedi are under the custody of the 704th MUNSS, but the whole purpose of the NATO mission is to equip, train and prepare in peacetime for “transfer” and “control” of the U.S. nuclear bombs to the Italian air force in case of war.

The Nuclear Burden

Maintaining the NATO nuclear strike mission in Europe does not come cheap or easy but “steals” scarce resources from non-nuclear military capabilities and operations that – unlike tactical nuclear bombs – are important for NATO.

Italy pays for the basing of the U.S. Air Force 704th MUNSS at Ghedi, for security upgrades needed to protect the weapons at the base, and for training pilots and maintaining Tornado aircraft to meet the stringent certification requirements for nuclear strike weapons. Moreover, the cost of securing the B61 bombs at the European bases is expected to more than double over the next few years (to $154 million) to meet increased U.S. security standards for storage of nuclear weapons.

But these costs are getting harder to justify given the serious financial challenges facing Italy. The air force’s annual flying hours dropped form 150,000 in 1990 to 90,000 in 2010, training reportedly declined by 80 percent from 2005 to 2011, and training for air operations other than Afghanistan apparently has been “pared to the bone.” In addition, the Italian defense posture is in the middle of a 30-percent contraction of the overall operational, logistical and headquarters network spending. The F-35 fighter-bomber program, part of which is scheduled to replace the current fleet of Tornados in the nuclear strike mission, has already been cut by a third and the new government has signaled its intension to cut the program further.

Under such conditions, maintaining a nuclear mission for the Italian air force better be really important.

Most of the costs of the European nuclear mission are carried by the United States. Over the next decade, the United States plans to spend roughly $10 billion to modernize the B61 bomb, over $1 billion more to make the new guided B61-12 compatible with four existing aircraft, another $350 million to make the new stealthy F-35 fighter-bomber nuclear-capable, and another $1 billion to sustain the deployment in Europe.

This adds up to roughly $12.5 billion for sustaining, securing, and modernizing U.S. nuclear bombs in Europe over the next decade. Whether the price tag is worth it obviously must to be weighed against the security benefits it provides to NATO, how well the deployment fits with U.S. and NATO nuclear arms control policy, and whether there are more important defense needs that could benefit from that level of funding.

Fake Versus Real Reassurance

The anniversary placard displayed at Ghedi Air Base claims that the U.S. non-strategic nuclear bombs have “protected the free nations of the world” even after the end of the Cold War. And during the nuclear safety exercise at Ghedi in January, the commander of the U.S. Air Force 52nd Fighter Wing told the U.S. and Italian security forces that “your mission today is still as relevant as when together our country stared down the Soviet Union alongside a valued member of our enduring alliance.” (Emphasis added).

That is probably an exaggeration, to put it mildly. In fact, it is hard to find any evidence that the deployment of non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe after the end of the Cold War has protected anything or that the mission is even remotely as relevant today. The biggest challenge today seems to be to protect the weapons and to find the money to pay for it.

NATO’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, moreover, strongly suggests that NATO itself does not attribute any real role to the non-strategic nuclear weapons in reassuring eastern NATO allies of a U.S. commitment to defend them. Yet this reassurance role is the main justification used by proponents of the deployment. In hindsight, the reassurance effect appears to be largely doctrine talk, while NATO’s actual response has focused on non-nuclear forces and exercises.

To the extent that a potential nuclear card has been played, such as when three B-52 and two B-2 nuclear-capable bombers were temporarily deployed to England earlier this month, it was done with long-range strategic bombers, not tactical dual-capable aircraft. The fact that nuclear fighter-bombers were already in Europe seemed irrelevant. The same was done in March 2013, when the United States deployed long-range bombers over Korea to reassure South Korea and Japan against North Korean threats.

No eastern European ally has said: “Hold the bombers, hold the paratroopers, hold the naval exercises! The B61 nuclear bombs in Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Turkey are here to reassure us against Russia.”

In the real world, the non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe are fake reassurance because they are useless and meaningless for the kind of crises that face NATO allies today or in the foreseeable future. NATO pays a king’s ransom for the deployment with very little to show for it.

President Obama has asked for $1 billion to reassure Europe against Russia. But he could get a dozen non-nuclear European Reassurance Initiatives for the price of sustaining, modernizing, and deploying the non-strategic nuclear bombs in Europe. Doing so would help “put an end to Cold War thinking” as he promised in Prague five years ago.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund and New Land Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Exercises Amidst Ukrainian Crisis: Time For Cooler Heads

A Russian Tu-95MS long-range bomber drops an AS-15 Kent nuclear-capable cruise missiles from its bomb bay on May 8th. Six AS-15s were dropped from the bomb bay that day as part of a Russian nuclear strike exercise.

By Hans M. Kristensen

Less than a week after Russia carried out a nuclear strike exercise, the United States has begun its own annual nuclear strike exercise.

The exercises conducted by the world’s two largest nuclear-armed states come in the midst of the Ukraine crisis, as NATO and Russia appear to slide back down into a tit-for-tat posturing not seen since the Cold War.

Military posturing in Russia and NATO threaten to worsen the crisis and return Europe to an “us-and-them” adversarial relationship.

One good thing: the crisis so far has demonstrated the uselessness of the U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in Europe.

Different Styles, Different Messages

Vladimir Putin’s televised commanding of the nuclear strike exercise – flanked by the presidents of Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in the Russian National Defense Command Center – made one thing very clear: Putin wanted to showcase his nuclear might to the world. Russian military news media showed the huge displays in the Command Center with the launch positions and impact areas of long-range nuclear missiles launched from a road-mobile launchers and ballistic missile submarines.

A map in the National Defense Command Center shows the launch points and impact areas of nuclear missiles launched across Russia. Click to see larger version.

Other displays and images on the Russian Internet showed AS-15 Kent (Kh-55) nuclear cruise missiles launched from a Tu-95 “Bear” bomber (six missiles were launched), short-range ballistic missiles, and air-defense and ballistic missile defense interceptors reportedly repelled a “massive rocket nuclear strike” launched against Russia by “a hypothetical opponent.”

Of course everything was said to work just perfectly but there is no way to known how well the Russian forces performed, how realistic the exercise was designed to be, or what was different compared with previous exercises. Russia conducts these exercises each year and Russian military planners love to launch a lot of rockets very quickly with lots of smoke and noise (it looks impressive on television). But the exercise looked more like a one-day snap intended to showcase test launching of offensive and defensive forces rather than a significant new development.

The STRATCOM announcement of the Global Lightning exercise was, in contrast, much more timid, so far limited to a single press release. Mindful of the problematic timing, the press release said the timing was “unrelated to real-world events” and that the exercise has been planned for more than a year. But some new stories nonetheless linked the two events.

The STRATCOM press release didn’t say much about the exercise scenario or what forces would be involved. Only bombers – whose operations are highly visible and would probably be noticed anyway – were mentioned: 10 B-52 and up to six B-2 bombers. But SSBNs and ICBMs also participate in Global Lightning (although not with live test launches as in the Russian exercise) as well as refueling tankers and command and control units.

As its main annual strategic nuclear command post/field training exercise, STRATCOM uses Global Lightning to verify the readiness and effectiveness of U.S. nuclear forces and practice strike scenarios from OPLAN 8010-12 and other war plans against potential adversaries. Last updated in June 2012, OPLAN 8010-12 is being adjusted to incorporate decisions from the Obama administration’s June 2013 nuclear weapons employment strategy.

Although STRATCOM has only mentioned bombers participating in the Global Lightning 14 exercise, SSBNs and ICBMs also participate. This picture shows a V-22 Osprey delivering supplies to USS Louisiana (SSBN-424) during operations in the Pacific in 2012.

The previous Global Lightning exercise was held in 2012 (Global Lightning 2013 was canceled due to budget cuts) and is normally accompanied or followed by other nuclear-related exercises such as Global Thunder, Vigilant Shield, and Terminal Fury. In addition to strategic nuclear planning, STRATCOM supports regional nuclear targeting as well. The 2012 Global Lightning exercise supported Pacific Command’s Terminal Fury exercise in the Pacific and included several crisis and time-sensitive strike scenarios against extremely difficult target sets never seen before in Terminal Fury.

Back to Us and Them

One can read a lot into the exercises, if one really wants to. And some commentators have suggested that the exercises were deliberately intended as reminders to “the other side” of the Ukrainian crisis about the horrific military destructive power each side possesses.

I don’t think the Russian exercise or the U.S. Global Lightning exercise are directly linked to the Ukrainian crisis; they were planned long in advance. Nuclear weapons – and fortunately so – seem completely out of proportion to the circumstances of the situation in Ukraine.

Nonetheless, they do matter in the overall east-west sparing and the fact that the national leadership of Russia and the United States authorized these nuclear exercises at this particular time is a cause for concern. It is the first time nuclear forces have been rattled during the Ukrainian crisis. And because they are nuclear, the exercises add important weight to a pattern of increasingly militaristic behaviors on both sides.

Russia’s invasion of Crimea – bizarrely coinciding with Russia celebrating its defeat of a different invasion of the Soviet Union 73 years ago – to prevent loosing its Black Sea fleet area to an increasingly westerly looking Ukraine, and NATO responding by beefing up its military posture in Eastern Europe far from Ukraine to demonstrate “that NATO is prepared to meet and deter any threat to our alliance” – even though there are no signs of an increased Russian military threat against NATO territory in general – ought to have caused political leaders on both sides to delay the nuclear exercises to avoid fueling crisis sentiments and military posturing any further.

Instead, both sides now seem determined to stick to their guns and overturn the budding partnership and trust that had emerged after the Cold War. In doing so, the danger is, of course, that the military institutions on both sides are allowed to dominate the official responses to the crisis and deepen it rather than de-escalating and resolving it. No doubt, military hawks and defense contractors on both sides see an opportunity to use the Ukrainian crisis to get the defense budgets and weapons they have wanted for years but been unable to get because of budget cuts and the absence of a significant military “threat.”

A French Mirage follows a Russian Tu-22M3 Backfire bomber over the Baltic Sea in June 2013. Three months earlier, two Russian Tu-22M3s escorted by four Su-27 Flanker fighters simulated a nuclear attack on two targets in Sweden.

Russia has already announced plans to add 30 warships to the Black Sea Fleet and widen deployment of navy and air forces to four additional bases in Crimea.

The Russian air force has resumed long-range training flights with nuclear aircraft and often violates the air space of other countries. In March 2013, two Tu-22M3 backfire bombers reportedly simulated a nuclear strike against two targets in Sweden (although the aircraft did not violate Swedish air space at that time).

It is almost inevitable that increased NATO deployments and defense budgets in eastern member countries will trigger Russian military counter-steps closer to NATO borders. One of the first tell signs will be the Zapad exercise later this fall.

For its part, NATO has already deployed ships, aircraft, and troops to Eastern European countries and is considering how to further change its defense planning to respond with “air, land and sea ’reassurances’” to “a different paradigm, a different rule set” (translation: Russia is now an official military threat), according to NATO’s military commander General Philip Breedlove and “position those ‘reassurances’ across the breadth of our exposure: north, center, and south.”

NATO General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen echoed Breedlove’s defense vision during a visit to Estonia on May 1st, saying the Ukrainian crisis had triggered a NATO response where “aircraft and ships from across the Alliance are reinforcing the security from the Baltic to the Black Sea.”

Breedlove and Rasmussen paint a military response that appears to go beyond the Ukrainian crisis itself and involve a broad reinforcement of NATO’s eastern areas. Breedlove got NATO approval for the initial deployments and exercises seen in recent weeks, but the defense ministers meeting in Brussels in June likely will prepare more fundamental changes to NATO military posture for approval at the NATO Summit in Wales in September.

General Secretary Anders Fogh Rasmussen and other NATO officials describe a broad military reinforcement across NATO in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel says requires NATO countries to increase their defense budgets.

Among other aspects, those changes will probably involve modifying NATO’s General Intelligence Estimate (MC 161) and NATO Ministerial Guidance to explicitly identify Russia, once again, as a potential threat. Doing so will open the door for more specific Article 5 contingency plans for the defense of eastern European NATO countries.

In reality, the military responses to the Ukraine crisis include many efforts that have been underway within NATO since 2008. The Baltic States and Poland have been urging NATO to draw up contingency plans for the defense of Eastern Europe against Russian incursions or military attack. Two obstacles worked against this: declining defense budgets (who’s going to pay for it?) and a reluctance to officially declare Russia to be a military threat to NATO. The latter obstacle is now gone and U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel’s is now publicly using the Ukraine crisis to ask NATO countries to increase their defense budgets.

After a decade of depleting its declining resources on an costly, open-ended war in Afghanistan that it cannot win, the Ukrainian crisis seems to have given NATO a sense of new purpose: a return to its core mission of defending NATO territory. “Russia’s actions in Ukraine have made NATO’s value abundantly clear,” Hagel said earlier this month, “and I know from my frequent conversations with NATO defense ministers that they do not need any convincing on this point.”

But one of the biggest obstacles to increasing defense budgets, Hagel said, “has been a sense that the end of the Cold War ushered in the ‘end of history’ – an end to insecurity, at least in Europe and the end [of] aggression by nation states. But Russia’s action in Ukraine shatter that myth and usher in bracing new realities,” he concluded, and “over the long term, we should expect Russia to test our alliance’s purpose, stamina, and commitment.”

In other words, it’s back to us and them.

It is difficult to dismiss Eastern European jitters about Russia – after all, they were occupied by the Soviet Union and joined NATO specifically to get the security guarantee so never to be occupied again. And Russia’s unlawful annexation of Crimea has completely shattered its former status as a European partner.

But the big question is whether NATO responding to Ukraine by beefing up its military inadvertently plays into the hands of Russian hardliners and will serve to deepen rather than easing military competition in Europe.

Why the Putin regime would respond favorably to NATO increasing its military posture in Eastern Europe is not clear. Yet it seems inconceivable that NATO could chose not to do so; after all, providing military protection is the core purpose of the Alliance.

At the same time, the more they two sides posture to demonstrate their resolve or unity, the harder it will be for them to de-escalate the crisis and rebuild the trust. Remember, we’ve been down that road and it took us six decades to get out.

Rather, it seems more likely that beefing up military forces and operations will reaffirm, in the eyes of Russian policy makers and military planners, what they have already decided; that NATO is a threat that is trying to encroach Russia who therefore must protect its borders and secure a sphere of influence as a buffer. Georgy Bovt’s recent analysis in Moscow Times of the Russian mindset is worthwhile reading.

The Irrelevance of Tactical Nuclear Weapons

So what does all of that mean for nuclear weapon in Europe? Remember, they’re supposed to reassure the NATO allies!

I hear many say that the Ukrainian crisis makes it very difficult to imagine a reduction, much less a withdrawal, of U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons from Europe. Some people have even argued that the Ukrainian crisis could have been avoided if Ukraine had kept the nuclear weapons the Soviet Union left behind when it crumbled in 1991 (the argument ignores that Ukraine didn’t have the keys to use the weapons and would have been isolated as a nuclear rogue if it had not handed them over).

Only two years ago, NATO rejected calls for a withdrawal of U.S. nuclear weapons from Europe based on the argument that the deployment continues to serve an important role as a symbol of the U.S. security commitment to Europe and because eastern European NATO countries wanted the weapons in Europe to be assured about their protection against Russia. The May 2012 Defense and Deterrence Posture Review (DDPR), implementing the Strategic Concept from 2010, reaffirmed status quo by concluding “that the Alliance’s nuclear force posture currently meets the criteria for an effective deterrence and defense posture.”

A B61 nuclear bomb trainer is loaded onto an F-16 somewhere in Europe, probably at Aviano Air Base in Italy. Some Eastern European NATO allies argue that the nuclear weapons provide important reassurance, but request deployment additional non-nuclear assets to deter Russia.

Yet here we are, only two years later, where the nuclear weapons have proven absolutely useless in reassuring the allies in the most serious crisis since the Cold War. Indeed, it is hard to think of a stronger reaffirmation of the impotence and irrelevance of tactical nuclear weapons to Europe’s security challenges than NATO’s decision to deploy conventional forces and beef up conventional contingency planning and defense budgets in response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and annexation of Crimea.

Put in another way, if the U.S. nuclear deployment was adequate for an effective deterrence and defense posture, why is it now inadequate to assure the allies?

In fact, one can argue with some validity that spending hundreds of millions of dollars on maintaining U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe after the end of the Cold War has done very little for NATO security, except wasting resources on a nuclear capability that is useless rather than spending the money on conventional capabilities that can be used. It is about fake versus real assurances.

The deployment of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe seems to be for academic and doctrinal discourses rather than for real security. In the real world they don’t seem to matter much and seem downright useless for the kinds of security challenges facing NATO countries today. But try telling that to current and former officials who have been spending the past five years lobbying and educating Eastern NATO governments on why the weapons should stay.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

Nuclear Modernization Briefings at the NPT Conference in New York

By Hans M. Kristensen

Last week I was in New York to brief two panels at the Third Session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2015 Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (phew).

The first panel was on “Current Status of Rebuilding and Modernizing the United States Warheads and Nuclear Weapons Complex,” an NGO side event organized on May 1st by the Alliance for Nuclear Accountability and the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF). While describing the U.S. programs, I got permission from the organizers to cover the modernization programs of all the nuclear-armed states. Quite a mouthful but it puts the U.S. efforts better in context and shows that nuclear weapon modernization is global challenge for the NPT.

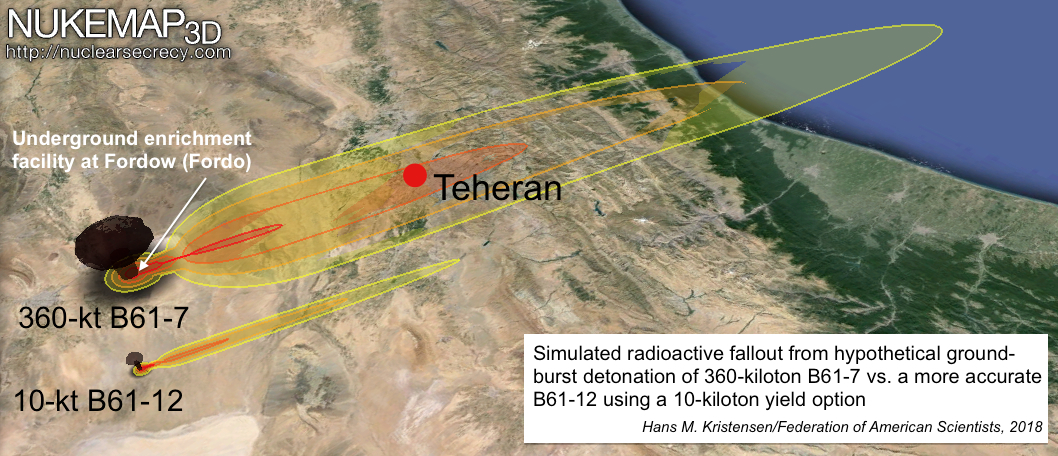

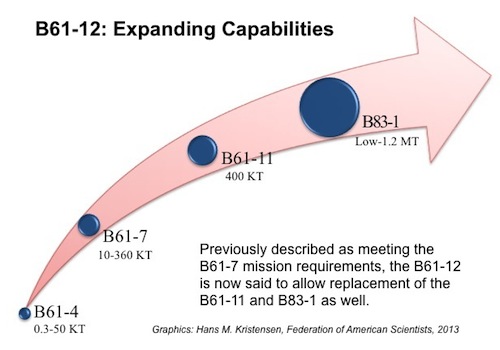

The second panel was on “The Future of the B61: Perspectives From the United States and Europe.” This GNO side event was organized by the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation on May 2nd. In my briefing I focused on providing factual information about the status and details of the B61 life-extension program, which more than a simple life-extension will produce the first guided, standoff nuclear bomb in the U.S. inventory, and significantly enhance NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

The two NGO side events were two of dozens organized by NGOs, in addition to the more official side events organized by governments and international organizations.

The 2014 PREPCOM is also the event where the United States last week disclosed that the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile has only shrunk by 309 warheads since 2009, far less than what many people had anticipated given Barack Obama’s speeches about “dramatic” and “bold” reductions and promises to “put an end to Cold War thinking.”

Yet in disclosing the size and history of its nuclear weapons stockpile and how many nuclear warheads have been dismantled each year, the United States has done something that no other nuclear-armed state has ever done, but all of them should do. Without such transparency, modernizations create mistrust, rumors, exaggerations, and worst-case planning that fuel larger-than-necessary defense spending and undermine everyone’s security.

For the 185 non-nuclear weapon states that have signed on to the NPT and renounced nuclear weapons in return of the promise made by the five nuclear-weapons states party to the treaty (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, and the United States) “to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to the cessation of the nuclear arms race at early date and to nuclear disarmament,” endless modernization of the nuclear forces by those same five nuclear weapons-states obviously calls into question their intension to fulfill the promise they made 45 years ago. Some of the nuclear modernizations underway are officially described as intended to operate into the 2080s – further into the future than the NPT and the nuclear era have lasted so far.

Download two briefings listed above: briefing 1 | briefing 2

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61-12 Nuclear Bomb Design Features

Click on image to download high-resolution version.

By Hans M. Kristensen

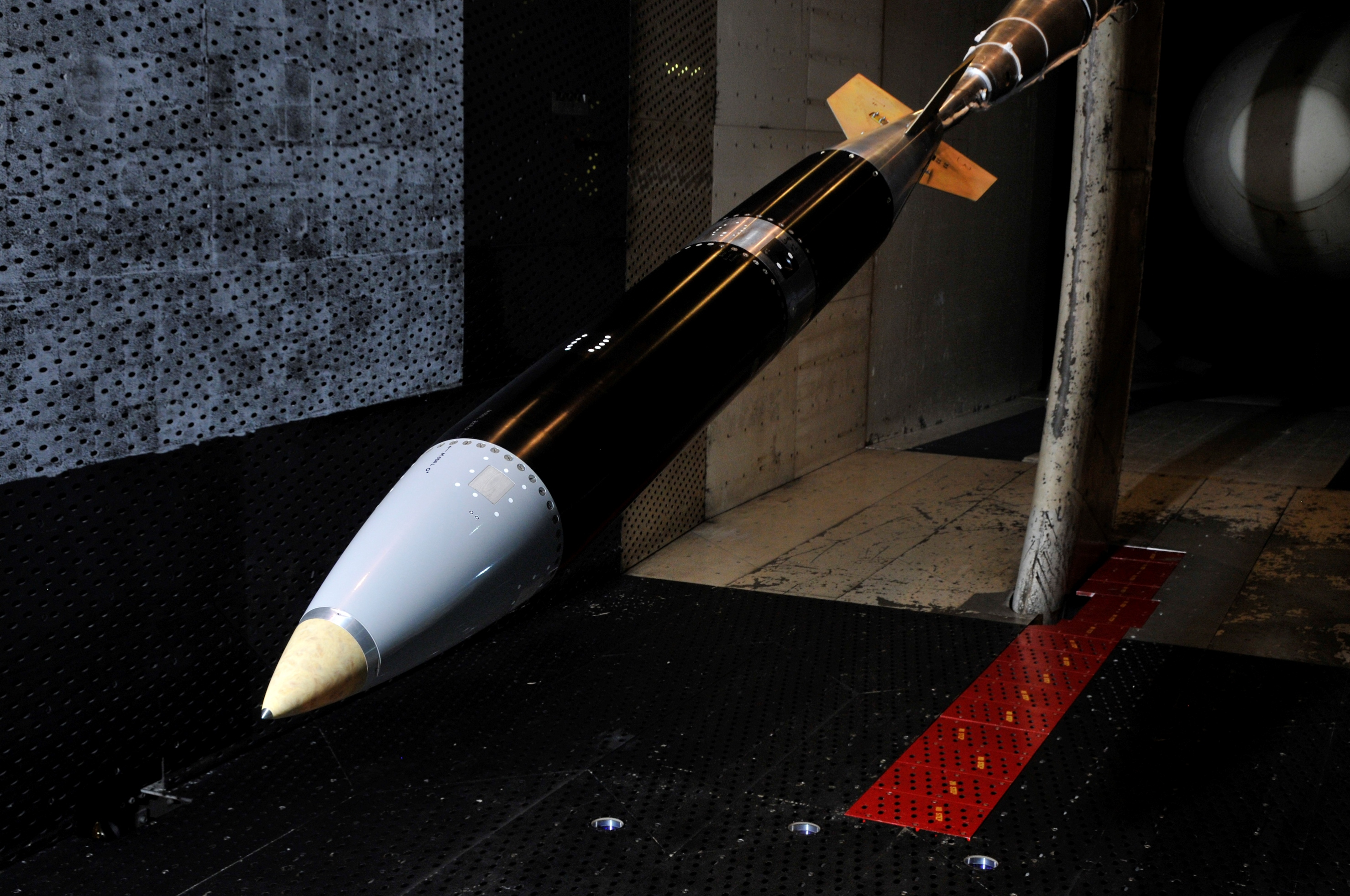

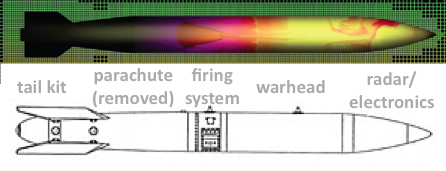

Additional design details of the new B61-12 guided standoff nuclear bomb are emerging with new images. The image above shows a full-scale B61-12 model hanging in a wind tunnel at Arnold Air Force Base.

The test “uncovered a previously uncharacterized physical phenomenon,” according to Sandia National Laboratories, that would affect weapons performance.

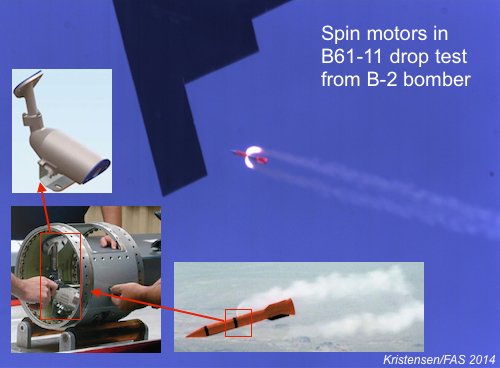

Apparently a reference to the interaction between weapons spin rocket motors and the new guided tail kit assembly. Existing B61 models do not have the guided tail kit and are less accurate than the B61-12.

The spin rocket motors were previously developed to stabilize the aerodynamic behavior of B61 bombs during descent. Previous wind tunnel tests of those weapons had revealed a so-called “counter torque” effect where plumes from the rocket motors worked against the fin performance, counteracting the torque from the motors and reducing the vehicle spin rate.

The B61-12 will use spin rocket motors similar to those on the B61-11, designed to improve stability during descent.

Because the B61-12 will be enhanced with a new guided tail kit to improve its accuracy, the wind tunnel test was necessary to determine how the new tail interacts with the spin rocket motors.

The wind tunnel image also shows the new guided tail kit in greater detail than seen before, including the four maneuverable fins that are controlled by an Internal Navigation System. In addition to improving accuracy, the fins also give the B61-12 a limited standoff capability. Current B61 versions do not have Internal Navigation System or standoff capability.

The new guided tail kit assembly is clearly visible on this image, slightly enhanced to sharpen features. The spike extending from the rear of the bomb is not part of the design but the arm that holds the bomb in place in the wind tunnel.

The NNSA budget request for FY2015 includes $643 million for development of the B61-12, which is expected to cost $8 billion to $10 billion to develop and produce. Two B61 hydrodynamic shots were conducted in 2013. The Air Force budget request includes nearly $200 million for development of the guided tail kit, estimated at more than $1 billion. Several hundred millions more are required to integrate the B61-12 on five different aircraft, including Belgian, Dutch, German, Italian and Turkish fighter-bombers. An estimated 480 B61-12 bombs are planned, with first production unit in 2020.

The B61-12 will also be integrated on the new F-35A Lightning II aircraft by 2025. The combination of the guided standoff B61-12 with the stealthy fifth-generation F-35A fighter-bomber will significantly improve the military capabilities of NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61-12 Nuclear Bomb Integration On NATO Aircraft To Start In 2015

Integration of the new guided B61-12 nuclear bomb will begin in 2015 on NATO Tornado and F-16 aircraft, seen here in 2008 at the Italian nuclear base at Ghedi Torre for the Steadfast Noon nuclear strike exercise. Image: EUCOM.

By Hans M. Kristensen

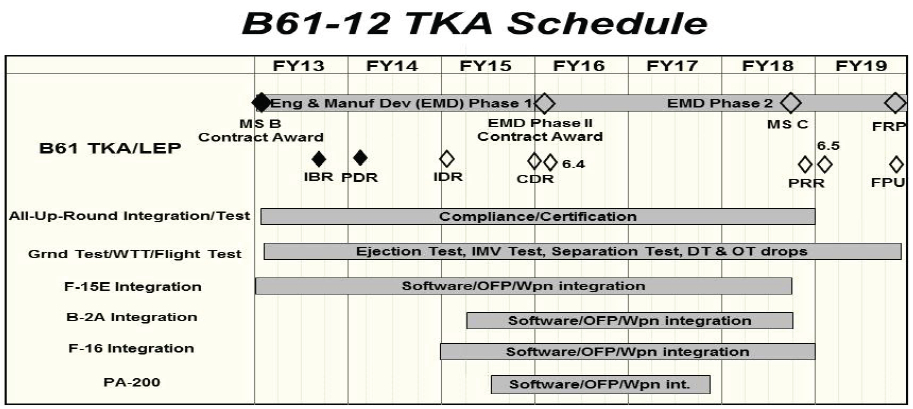

The US Air Force budget request for Fiscal Year 2015 shows that integration of the B61-12 on NATO F-16 and Tornado aircraft will start in 2015 for completion in 2017 and 2018.

The integration marks the beginning of a significant enhancement of the military capability of NATO’s nuclear posture in Europe and comes only three years after NATO in 2012 said its current nuclear posture meets its security requirements and that it was working to create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons.

The integration will take place on Belgian, Dutch, and Turkish F-16A/B and on German and Italian PA-200 Tornado fighter-bombers. It is unknown if US and NATO F-16s happen simultaneously or US aircraft are first, but the process will last four years between 2015 and 2018. Integration of German and Italian Tornados will take a little over two years (see graph below).

The USAF budget request shows the timelines for integration of the B61-12 onto US and NATO legacy aircraft. Later the weapon will also be integrated onto the F-35A and LRS-B next-generation long-range bomber.

The B61-12 will also be integrated on USAF F-15E (integration began last year), F-16C/D, and B-2A aircraft, and later on the F-35A Lightning II. The F-35A will later replace the F-16s. The US Air Force plans to equip all F-35s in Europe with nuclear capability by 2024.

In addition to the US Air Force, the nuclear-capable F-35A will be supplied to the Dutch, Italian, Turkish, and possibly Belgian air forces.

From the mid-2020s, the B61-12 will also be integrated on the next-generation heavy bomber (LRS-B) planned by the US Air Force.

The integration work includes software upgrades on the legacy aircraft, operational flight tests, and full weapon integration. Development of the guided tail kit is well underway in reparations for operational tests. Seven flight tests are planned for 2015. The nuclear warhead and some non-nuclear components won’t be ready until the end of the decade. The first complete B61-12 is scheduled for 2020.

Through 2019, the integration efforts are scheduled to cost more than $1 billion. Another $154 million is needed to improve security at the nuclear bases in Europe.

Integration of US nuclear weapons onto aircraft of non-nuclear weapon states that have signed the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty and promised “not to receive the transfer from any transferor whatsoever of nuclear weapons or other nuclear explosive devices or of control over such weapons or explosive devices directly, or indirectly,” is, to say the least, problematic.

The arrangement of equipping non-nuclear NATO allies with the capability and role to deliver US nuclear weapons was in place before the NPT entered into effect and was accepted by the NPT regime during the Cold War. But for NATO to continue this arrangement contradicts the non-proliferation standards that the member countries are trying to promote in the post-Cold War world.

How scattering enhanced nuclear bombs across Europe in five non-nuclear countries will enable “bold reductions” in US and Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons in Europe and help create the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons is another question.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

NATO Nuclear Weapons Security Costs Expected to Double

Former US Air Force Europe commander General Rodger Brady shakes hands with 703 Munitions Support Squadron personnel at Volkel Air Base in June 2008 during security upgrades to U.S. nuclear weapons storage sites in Europe. More expensive security upgrades are planned.

By Hans M. Kristensen

The cost of securing U.S. non-strategic nuclear weapons deployed in Europe is expected to nearly double to meet increased U.S. security standards, according to the Pentagon’s FY2015 budget request.

According to the Department of Defense NATO Security Investment Program , NATO has invested over $80 Million since 2000 to secure nuclear weapons storage sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey.

But according to the Department of Defense budget request, new U.S. security standards will require another $154 million to further beef up security at six bases in the five countries.

DOD budget document says more expensive security upgrades are needed for nuclear bases in Europe.

After a US Air Force Blue Ribbon Review in 2008 discovered that “most” U.S. nuclear weapons sites in Europe did not meet U.S. security requirements, the Dutch government denied there were security problems.

Yet more than $63 million of the over $80 million spent on improving security since 2000 were spent in 2011-2012 – apparently in response to the Blue Ribbon Review findings and other issues.

The additional $154 million suggests that the upgrades in 2011-2012 did not fix all the security issues at the European nuclear bases.

The budget document – which also comes close to officially confirming the deployment of nuclear weapons in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey – states:

NATO funds infrastructure required to store special weapons within secure sites and facilities. Since 2000, NATO has invested over $80 million in infrastructure improvements in storage sites in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey. Another $154 million will be invested in these sites for security improvements to meet with stringent new U.S. standards.

The US Air Force still deploys about 180 nuclear B61 bombs at six bases in five European countries. Despite tight security, the bases are not secure enough.

In addition to the growing security costs, the United States spends approximately $100 million per year to deploy 184 nuclear B61 bombs in the five NATO countries. And it plans to spend an additional $10 billion on modernizing the B61 bombs and hundreds of millions on integrating the weapons on the new F-35A Lightning fighter-bomber.

No doubt the United States and NATO have more urgent defense needs to spend that money on than non-strategic nuclear weapons.

Additional background: Briefing on B61 bomb and deployment in Europe

This publication was made possible by a grant from the Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

B61-12: First Pictures Show New Military Capability

The guided tail kit of the B61-12 will create the first U.S. guided nuclear bomb.

Image: National Nuclear Security Administration. Annotations added by FAS.

By Hans M. Kristensen

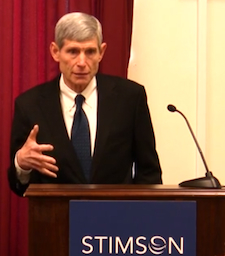

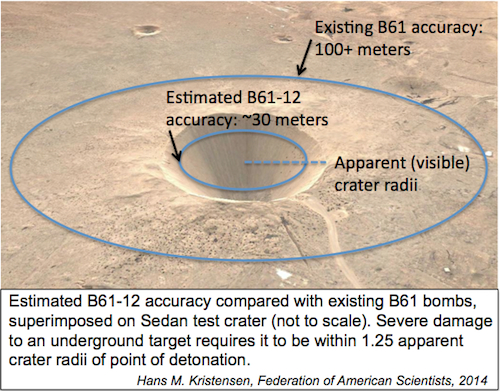

The U.S. government has published the first images of the Air Force’s new B61-12 nuclear bomb. The images for the first time show the new guided tail kit that will provide new military capabilities in violation of the Nuclear Posture Review.

The tail kit will increase the accuracy of the bomb and enable it to be used against targets that today require bombs with higher yields.

The guided tail kit is also capable of supporting new military missions and will, according to the former USAF Chief of Staff, affect the way strike planners think about how to use the weapon in a war.

The new guided weapon will be deployed to Europe, replacing nearly 200 non-guided nuclear B61 bombs currently deployed in Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey.

Military Characteristics

The images show significant changes to the rear end of the bomb where the tail wing section has been completely replaced and the internal parachute removed. The length of the B61-12 appears to be very similar to the existing B61 (except B61-11 which is longer) although possibly a little bit shorter (see below).

The guided tail kit on the B61-12 (top) is replacing the fixed tail section on the existing B61 (bottom) and the parachute inside.

Source: Los Alamos National Laboratory/U.S. Air Force. Annotations added by FAS.

The new guided tail kit will not use GPS (global positioning system) but is thought to use an Internal Guidance System (INS). The precise accuracy is not known, but conventional bombs using INS can achieve an accuracy of 30 meters or less. Even if it were a little less for the B61-12, it is still a significant improvement of the 110-180 meters accuracy that nuclear gravity bombs normally achieve in test drops.

The tail kit will also provide the B61 with a “modest standoff capability” by enabling it to glide toward its target, another military capability the B61 doesn’t have today.

Inside the bomb, non-nuclear components will be refurbished or replaced. In the nuclear explosives package the B61-4 primary (pit) will be reused and the secondary remanufactured. Detonators will be replaced with a design used in the W88 warhead, conventional Insensitive High Explosives will be remanufactured, and a new Gas Transfer System will be installed to increase the performance margin of the primary.

The B61-4 warhead used in the B61-12 has four selectable yields of 0.3, 5, 10, and 50 kilotons. LEPs are not allowed to increase the yield of warheads but GAO disclosed in 2011 that STRATCOM “expressed a requirement for a different yield [and that] U.S. European Command and SHAPE [Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe] agreed to the proposal.” It is unknown if the different yield is a modification of one of the three lower yield options or an increase of the maximum yield. During another upgrade of the B61-7 bomb to the B61-11 earth-penetrator, the yield was increased from 360 kilotons to 400 kilotons.

Although increasing safety and security were prominent justifications for securing Congressional funding for the B61-12, enhancements to the safety and security of the new bomb are apparently modest. More exotic technologies such as multi-point safety and optical detonators were rejected.

The complex upgrades add up to the most expensive U.S. nuclear bomb project ever – currently estimated at approximately $10 billion for 400-500 bombs.

Political Implications