The DOE’s Proactive FY25 Budget Is Another Workforce Win On the Way to Staffing the Energy Transition

The DOE has spent considerable time in the last few years focused on how to strengthen the Department’s workforce and deliver on its mission – including running the largest basic science research engine in the country, and managing a wide range of decarbonization efforts through clean energy technology innovation, demonstration, and deployment. In general, their efforts have been successful – in no small part because they have been creative and have had access to tools like the Intergovernmental Personnel Act and the Direct Hire Authority that supported the Clean Energy Corps.

It’s no surprise then, that the agency’s FY 2025 budget looks to continue investing in the current and future science and energy workforce. The budget suggests DOE offices are thinking proactively about departmental capacity – in both the federal workforce, and beyond it through workforce development programs that actively grow the pool of future scientists.

Current BIL and IRA Talent

As seen below, several DOE offices across the science, innovation and infrastructure domains have requested increases in program direction funding in FY 2025. Program direction funds are an under-valued but critical resource for enabling the energy transition: DOE must be able to recruit and retain expert staff with a high level of technical proficiency who can meet the multi-faceted demands of public service – reviewing proposals, building bridges with industry, maintaining user facilities, and overseeing execution of complex federal technology programs.

These requests also reflect a larger strategy, motivated by the constraints put on federal management funding by IIJA and IRA. First, while those pieces of legislation poured resources into federal energy innovation, they also limited program direction funds to 3% of account spending, which was highly constraining from a talent perspective – even with the creative use of hiring mechanisms like IPAs and various fellowships. In the final energy spending bill for FY 2024, this was raised to 5% and extended the funds connected to IIJA funding from expiring in 2026 to FY 2029 – a much-needed adjustment to the legislation.

Extensions to and increases in program direction funds are vital for DOE. If the levels of appropriated PD funds don’t match the programs and mandate of offices, it jeopardizes their ability to provide oversight, project management, and effective stewardship of taxpayer dollars. New program direction funding is similarly important for offices like the Grid Deployment Office, a new office formed from a combination of programs from IIJA and IRA and the Office of Electricity. The FY 2025 request includes a $40 million increase above FY 2023, including $30 million for a new microgrid initiative intended to strengthen grid reliability and resilience in high risk regions. The Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains is a more extreme example: because of its recent creation, it needs a sharp increase in program direction funds. In FY24 the office received only $1 million in PD funds, while its FY 2025 PD request is $20 million – a much more appropriate number to support the total office budget request of $113 million. These requests are important and necessary for the long-term ability of DOE to continue to fortify U.S. energy independence and innovation.

Future Workforce

Offices are also focused on building pathways for early career scientists to grow their expertise. The Office of Science (SC), DOE’s central hub for basic science research and National Lab oversight, is a prime example. First, SC’s program direction funding is incredibly low for an office of its size and magnitude, and it has steadily declined over the past several years to less than 3% of the SC appropriations as of FY 2023. The FY 2025 request increase of 8% will help remedy this.

SC has also focused on increasing funding for their workforce development programs, and specifically the Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) and its Reaching a New Energy Sciences Workforce (RENEW) programs. Both received an increase of $1-2 million – although one of WDTS’s other programs, the Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI), was reduced by about $1 million. For most of the WDTS programs, high housing and living costs are cited as a reason for the need for increasing support. These high costs have been cited as a barrier to workforce development at many of the National Labs as well. Congress should explore opportunities to be creative with stipends and program accessibility – to ensure that SC can continue to support workforce development at all levels.

Tech-Focused Green Jobs For Innovation

Federal climate initiatives, like the ‘Climate Corps’ and the National Climate Resilience Framework, overlook the integration of technology-focused green jobs, missing opportunities for equity and innovation in technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML). Our objective is to advocate for the integration of technology-focused green jobs within these initiatives to foster equity. Leveraging funding opportunities from recent legislation, notably the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) environmental education fund, we aim to craft novel job descriptions, tailored training programs, and foster strategic public-private partnerships.

Methods and Approach

Our approach was based on comprehensive research and extensive stakeholder engagement, including discussions with key federal agencies and industry experts, identifying challenges and opportunities for integrating technology-focused green jobs. We engaged with officials and experts from various organizations, including the Department of Energy, EPA, USDA, FEMA, New America, the Benton Institute, National Urban League, Kajeet, the Blue Green Alliance, and the Alliance for Rural Innovation.We conducted data research and analysis, reviewed government frameworks and CRS reports, as well as surveyed programs and reports from diverse sources.

Challenge and Opportunity

The integration of technology-focused green jobs within existing federal climate initiatives presents both challenges and opportunities. One primary challenge lies in the predominant focus on traditional green jobs within current initiatives, which may inadvertently overlook the potential for equitable opportunities in technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML). This narrow emphasis risks excluding individuals with expertise in emerging technologies from participating in climate-related efforts, hindering innovation and limiting the scope of solutions. Moreover, the lack of adequate integration of technology within climate strategies creates a gap in inclusive and forward-looking approaches, potentially impeding the effectiveness of initiatives aimed at addressing climate change. Addressing these challenges requires a paradigm shift in how federal climate initiatives are structured and implemented, necessitating a deliberate effort to incorporate technology-driven solutions alongside traditional green job programs.

However, amidst these challenges lie significant opportunities to foster equity and innovation in the climate sector. By advocating for the integration of technology-focused green jobs within federal initiatives, there is an opportunity to broaden the talent pool and harness the potential of emerging technologies to tackle pressing environmental issues. Leveraging funding opportunities from recent legislation, such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) environmental education fund, presents a unique opportunity to invest in novel job descriptions, tailored training programs, and strategic public-private partnerships. Furthermore, initiatives aimed at reconciling concerns about equity in job creation and transitions, particularly in designing roles that require advanced degrees and ensuring consistent labor protections, provide avenues for fostering a more inclusive and equitable workforce in the green technology sector. By seizing these opportunities, federal climate initiatives can not only advance technological innovation but also promote diversity, equity, and inclusion in the emerging green economy.

Plan of Action

Moving the integration of these policy frameworks internally and with an aspiration to reflect market and community needs will require a multi-faceted approach. In response to the identified challenges and opportunities, the following policy recommendations are proposed:

Recommendation 1. Restructuring Federal Climate Initiatives to Embrace Technology-Focused Green Jobs

In light of the evolving landscape of climate challenges and technological advancements, there is a pressing need to review existing federal climate initiatives, such as the ‘Climate Corps’ and the National Climate Resilience Framework, to actively integrate technology-focused green jobs. Doing so creates an opportunity for integrated implementation guidance. This recommendation aims to ensure equitable opportunities in technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) within the climate sector while addressing the intersection between climate and technology. By undertaking this restructuring, federal climate initiatives can better align with the demands of the modern workforce and foster innovation in climate solutions. For example, the two aforementioned initiatives and the Executive Order on Artificial Intelligence all infer or clearly mention the following: green or climate jobs, equity, job training programs and tech and climate literacy. There is room to create programs to research and generate solutions around the ecological impacts of AI development within the auspices of the Climate Resilience Framework, and consider creating roles to implement those solutions as part of the Climate Corps (see Appendix II).

The rationale behind this recommendation lies in the recognition of the imperative to adapt federal climate initiatives to embrace emerging technologies and promote diversity and inclusion in green job opportunities. As the climate crisis intensifies and technological advancements accelerate, there is a growing need for skilled professionals who can leverage technology to address environmental challenges effectively. However, existing initiatives predominantly prioritize traditional green jobs, potentially overlooking the untapped potential of technology-driven solutions. Therefore, restructuring federal climate initiatives to actively integrate technology-focused green jobs is essential to harnessing the full spectrum of talent and expertise needed to confront the complexities of climate change.

- Developing a Green Tech Job Initiative. This initiative should focus on creating and promoting jobs in the tech, AI, and ML sectors that contribute to climate solutions. This could include roles in developing clean energy technologies, climate modeling, and data analysis for climate research and policy development. Burgeoning industries such as regenerative finance offer opportunities to combine AI and climate resilience goals.

- Ensuring Equitable Opportunities. Policies should be put in place to ensure these job opportunities are accessible to all, regardless of background or location. One example would be to leverage the Justice40 initiative, and use those allocations to underserved communities to create targeted training and education programs in tech-driven environmental solutions for underrepresented groups. Additionally, public-private partnerships could be strategically designed to support community-based projects that utilize technology to address local environmental issues.

- Addressing the Intersection of Climate and Technology. The intersection of climate and technology should be a key focus of federal climate policy. This could involve promoting the use of technology in climate mitigation and adaptation strategies, as well as considering the environmental impact of the tech industry itself. (Strengthening community colleges, accredited online programs and other low-cost alternatives to traditional education and job training)

Recommendation 2. Leveraging Funding for Technology-Driven Solutions in Federal Climate Initiatives

In order to harness the funding avenues provided by recent legislation such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) environmental education fund, strategic policy measures must be implemented to facilitate the development of comprehensive job descriptions, tailored training plans, and robust public-private partnerships aimed at advancing technology-driven solutions within federal climate initiatives. This recommendation underscores the importance of utilizing available resources to cultivate a skilled workforce, foster innovation, and enhance collaboration between government, industry, and academia in addressing climate challenges through technology.

The rationale behind this recommendation is rooted in the recognition of the transformative potential of technology-driven solutions in mitigating climate change and building resilience. With significant funding streams allocated to climate-related initiatives, there is a unique opportunity to invest in the development of job descriptions that reflect the evolving demands of the green technology sector, as well as training programs that equip individuals with the necessary skills to excel in these roles. Moreover, fostering robust public-private partnerships can facilitate knowledge sharing, resource pooling, and joint innovation efforts, thereby maximizing the impact of federal climate initiatives. By strategically leveraging available funding, federal agencies can catalyze the adoption of technology-driven solutions and drive progress towards a more sustainable and resilient future.

- Comprehensive Job Descriptions. Develop comprehensive job descriptions for technology-focused green jobs within federal climate initiatives. These descriptions should clearly outline the roles and responsibilities, required skills and qualifications, and potential career paths. This could be overseen by the Department of Labor (DOL) in collaboration with the Department of Energy (DOE) and the EPA.

- Tailored Training Plans. Establish tailored training plans to equip individuals with the necessary skills for these jobs. This could involve partnerships with educational institutions and industry bodies to develop curriculum and training programs. The National Science Foundation (NSF) could play a key role in this, given its mandate to promote science and engineering education.

- Public-Private Partnerships. Foster robust public-private partnerships to advance technology-driven solutions within federal climate initiatives. This could involve collaborations between government agencies, tech companies, research institutions, and non-profit organizations. The Department of Commerce, through its National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), could facilitate these partnerships, given its role in fostering innovation and industrial competitiveness.

Recommendation 3. Updating Bureau of Labor Statistics Job Categories for Green and Tech Jobs

To address the outdated Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) job categories, particularly in relation to the green and innovation economies, federal agencies and stakeholders must collaborate to support an update of these categories and classifications. This recommendation emphasizes the importance of modernizing job classifications to accurately reflect the evolving nature of the workforce, especially in sectors related to green technology and innovation.

The rationale behind this recommendation is rooted in the recognition of the significant impact that outdated job categories can have on program and policy design, particularly in areas related to green and technology-driven jobs. Currently the green jobs categorization work has been interrupted by sequestration.1 The tech job updates are on differing schedules. By updating BLS job categories to align with current market trends and emerging technologies, federal agencies can ensure that workforce development efforts are targeted and effective. Moreover, fostering collaboration between public and private sector stakeholders, alongside inter-agency work, can provide the necessary support for BLS to undertake this update process. Through coordinated efforts, agencies can contribute valuable insights and expertise to inform the revision of job categories, ultimately facilitating more informed decision-making and resource allocation in the domains of green and tech jobs.

- Inter-Agency Collaboration. Establish an inter-agency task force, including representatives from the BLS, Department of Energy (DOE), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Department of Labor (DOL), to review and update the current job categories and classifications. This task force would be responsible for ensuring that the classifications accurately reflect the evolving nature of jobs in the green and innovation economies.

- Public-Private Partnerships. Engage in public-private partnerships with industry leaders, academic institutions, and non-profit organizations. These partnerships can provide valuable insights into the changing job landscape and help inform the update of job categories and classifications.

- Stakeholder Engagement. Conduct regular consultations with stakeholders, including employers, workers, and unions in the green and innovation economies. Their input can ensure that the updated classifications accurately represent the realities of the job market.

- Regular Updates. Implement a policy for regular reviews and updates of job categories and classifications, particularly in renewing and syncing the green and tech jobs.The Office of Budget and Management can offer guidance about regular reviews and feedback based on government-wide standards. Initiating such a policy may require additional personnel in the short-term, but long-term this will increase agency efficiency. It will also ensure that the classifications remain relevant as the green and innovation economies continue to evolve (see FAQ section and Appendix I).

Conclusion

The integration of technology-focused green jobs within federal climate initiatives is imperative for fostering equity and innovation in addressing climate challenges. By restructuring existing programs and leveraging funding opportunities, the federal government can create inclusive pathways for individuals to contribute to climate solutions while advancing in technology-driven fields. Collaboration between government agencies, private sector partners, educational institutions, and community stakeholders is essential for developing comprehensive job descriptions, tailored training programs, and strategic public-private partnerships. Moreover, updating outdated job categories and classifications through inter-agency collaboration and stakeholder engagement will ensure that policy design accurately reflects the evolving green and innovation economies. Through these concerted efforts, the federal government can drive sustainable economic growth, promote workforce development, and address climate change in an equitable and inclusive manner.

Appendix

The recommendations outlined in this memo represent the culmination of extensive research and collaborative efforts with stakeholders. As of March 2024, while the final project and products are still undergoing refinement through stakeholder collaboration, the values, solutions, and potential implementation strategies detailed here are the outcomes of a thorough research process.

Our research methodology was comprehensive, employing diverse approaches such as stakeholder interviews, data analysis, examination of government frameworks, review of Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports, and surveying of existing programs and reports.

Stakeholder interviews were instrumental in gathering insights and perspectives from officials and experts across various sectors, including the Department of Energy, FEMA, New America, the Benton Institute, National Urban League, Kajeet, and the Alliance for Rural Innovation. Ongoing efforts are also in place to engage with additional key stakeholders such as the EPA, USDA, select Congressional offices, labor representatives, and community-based organizations and alliances.

Furthermore, our research included a thorough analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data to understand industry projections and job classification limitations. We employed text mining techniques to identify common themes and cross-topic programming or guidance within government frameworks. Additionally, we reviewed CRS reports to gain insights into public policy writings on related topics and examined existing programs and reports from various sources, including think tanks, international non-governmental organizations (INGOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and journalism.

The detailed findings of our research, including analyzed data, report summaries, and interview portfolio, are provided as appendices to this report, offering further depth and context to the recommendations outlined in the main text.

I. BLS Data Analysis: Employment Trends in Tech-Related Industries (2022-2032)

This section provides a detailed analysis of employment statistics extracted from CSV data across various industries, emphasizing green, AI, and tech jobs. The analysis outlines notable growth and potential advancement areas within technology-related sectors.

The robust growth in employment figures across key sectors such as computer and electronic product manufacturing, software publishing, and computer systems design underscores the promising outlook for tech-related job sectors. Similarly, the notable expansion within the information sector, while not explicitly AI-focused due to industry constraints, signals an escalating demand for skill sets closely aligned with technological advancements.

Moreover, the significant growth observed in support activities for agriculture and forestry hints at progressive strides in integrating green technologies within these domains. This holistic analysis not only sheds light on evolving employment trends but also provides valuable insights into market dynamics. Understanding these trends can aid in identifying potential opportunities for workforce development initiatives and strategic investments, ensuring alignment with emerging industry needs and fostering sustainable growth in the broader economic landscape.

Further Analysis

- Search Industry. Projections indicate a robust growth of 5.4% by 2032, signaling a promising trajectory for this sector.

- Self-Employed Workers. There’s a concerning projected decline in employment by 8.6%, indicating potential challenges for individuals in this category, necessitating exploration into the underlying causes.

- Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing, and Hunting. With an anticipated increase of 5.4% in employment, this sector demonstrates resilience and potential opportunities for growth, possibly driven by technological advancements or shifts in consumer demand.

- Utilities. A notable expected decline of 7.4% suggests a need for strategic interventions to address factors contributing to this trend, such as changing energy policies or shifts in market dynamics.

- Construction. While a moderate drop of 4.0% is projected, deeper analysis is warranted to understand whether this decline is indicative of cyclical fluctuations or more systemic challenges facing the industry.

- Manufacturing. Despite an overall slight decrease of 1.9%, it’s essential to dissect this trend further to discern which sub sectors are driving this decline and whether there are opportunities for innovation or retooling to reverse this trajectory.

- Wholesale Trade. A potential decline of 2.6% underscores the need for adaptation within this sector to address evolving market demands and competitive pressures.

- Retail Trade. With a significant expected drop of 10.0%, there’s a pressing need for retailers to explore strategies for reinvention, such as embracing e-commerce, enhancing customer experiences, or diversifying product offerings.

This nuanced analysis illuminates the varied trajectories across different industries, highlighting both areas of growth and challenges. It underscores the importance of proactive strategic planning and adaptation to navigate the evolving employment landscape effectively.

Regarding job classifications, while the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) provides valuable insights, it may not fully capture emerging roles in next-gen fields like AI, Web 3.0, Web 4.0, or climate tech. Exploring analogous roles or interdisciplinary skill sets within existing classifications can offer a starting point for understanding employment trends in these innovative domains. Additionally, leveraging alternative sources of data, such as industry reports or specialized surveys, can complement BLS data to provide a more comprehensive picture of evolving employment dynamics.

Based on the information from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and the search results, here’s what I found:

Market Demand for Tech Jobs. The BLS projects that overall employment in computer and information technology occupations is expected to grow much faster than the average for all occupations from 2022 to 20321. This suggests that these jobs are being filled according to market demand but not quickly enough for market demand.

Green and Tech Jobs. The BLS produces data on jobs related to the production of green goods and services, jobs related to the use of green technologies and practices, and green careers23. Many of the jobs listed on the provided BLS links fall under tech jobs, especially those related to AI, Web 3.0, and Web 4.0. However, specific data on jobs related to regenerative finance or climate tech was not found in the search results.

Education Requirements. Most of the jobs listed on the provided BLS links typically require a Bachelor’s degree for entry14. Some occupations may require a Master’s degree or higher. However, the exact education requirement can vary depending on the specific role and employer expectations.

These industries demonstrate growth potential from 2022 to the projected 2032 data, underscoring the increasing demand for tech-related job sectors, especially in computer and electronic product manufacturing, software publishing, and computer systems design. The information sector also shows significant growth, potentially reflecting the rise in AI and technology advancements.

Appendix I.A. BLS Data and Standard Occupation Codes (Climate Corps Specific)

These job classifications encompass a range of roles pertinent to green initiatives, infrastructure technology, and AI/ML development, reflecting the evolving landscape of employment opportunities.

Intersection of Green Jobs

Here’s a summary based on the jobs that explicitly refer to green jobs and the Federal Job Codes requiring different levels of education:

Green Jobs:

- 47-2230 Solar Photovoltaic Installers

- Description: Assemble, install, or maintain solar photovoltaic (PV) systems on roofs or other structures in compliance with site assessment and schematics. May include measuring, cutting, assembling, and bolting structural framing and solar modules. May perform minor electrical work such as current checks.

- Illustrative examples: Photovoltaic (PV) Installation Technician, Solar PV Installer

Federal Job Codes/Roles Requiring Different Levels of Education:

Bachelor’s Degree

- 11-2020 Marketing Managers

- 15-1250 Web and Digital Interface Designers

- 15-1255 Software Developers, Applications

- 15-1256 Software Developers, Systems Software

- 15-1299 Computer Occupations, All Other

- 17-3020 Electrical and Electronics Engineering Technicians

- 17-3023 Electrical and Electronics Engineering Technologists

- 17-3031 Surveying and Mapping Technicians

- 17-4010 Architectural and Civil Drafters

- 17-4020 Surveyors

- 17-4030 Cartographers and Photogrammetrists

- 17-4040 Hazardous Materials Removal Workers

Associate’s Degree

- 17-3020 Electrical and Electronics Engineering Technicians

- 17-3023 Electrical and Electronics Engineering Technologists

- 17-3031 Surveying and Mapping Technicians

- 17-4010 Architectural and Civil Drafters

High School Diploma

- 17-4050 Highway Maintenance Workers

- 17-4060 Rail-Track Laying and Maintenance Equipment Operators

Please note that while this list includes occupations that explicitly require a bachelor’s degree, associate’s degree, or high school diploma and showed up in an NLP search, it may have missed jobs that require certifications only. Additionally, other green job titles such as environmental engineers, conservationists, social scientists, and environmental scientists may require advanced degrees.

II. Analysis of EOs, Frameworks, TAs and Initiatives

This appendix analyzes executive orders, frameworks, technical assistance guides, and initiatives related to green and climate jobs, equity, job training programs, and tech and climate literacy. It presents findings from documents such as the American Climate Corps initiative, National Climate Resilience Framework, and Executive Order on AI, focusing on their implications for job creation and skills development in the green and tech sectors.

*Note about technologies use, this was text mined (SAS NLP, later bespoke app from team member) and Read (explain creating of text mining browser add on in methods overview/disclosure) using key terms “green”, “climate”, “equity”, “training”, “technology” and “literacy.”

Analysis of Executive Orders, Frameworks, Technical Assistance Guides, and Initiatives

This appendix delves into executive orders, frameworks, technical assistance guides, and initiatives pertaining to green and climate jobs, equity, job training programs, and tech and climate literacy. It scrutinizes documents such as the American Climate Corps initiative, National Climate Resilience Framework, and Executive Order on AI, dissecting their implications for job creation and skills development in the green and tech sectors.

Climate Corps:

- Green or Climate Jobs. The American Climate Corps initiative aims to equip young individuals with high-demand skills for employment in the clean energy economy, emphasizing areas like conservation, community resilience, clean energy deployment, and environmental justice.

- Equity. With a focus on marginalized communities, including energy communities, the initiative underscores equity and environmental justice.

- Job Training Programs. In its inaugural year, the initiative provides skills-based training to over 20,000 individuals and offers comprehensive information about federal technical assistance programs supporting community endeavors.

- Tech and Climate Literacy. While not explicitly stated, the emphasis on training in clean energy and climate resilience could indirectly enhance tech and climate literacy within both the federal workforce and the broader U.S. populace.

National Climate Resilience Framework:

- Green or Climate Jobs. The framework hints at initiatives such as restoring natural infrastructure and improving forestry practices, suggesting potential job opportunities in green or climate-related sectors.

- Equity. Ensuring inclusivity, the framework demonstrates a commitment to preventing any community from being overlooked, thereby reflecting an equity-oriented approach in climate resilience strategies.

- Job Training Programs. Although not overtly addressed, the comprehensive government approach mobilized by the framework may entail job training programs.

- Tech and Climate Literacy. While not explicitly discussed, the community-driven solutions and investments in clean energy and climate action endorsed by the framework could contribute to increased tech and climate literacy.

Executive Order on AI:

- Green or Climate Jobs. While not expressly mentioned, the acknowledgment of AI’s potential to tackle urgent challenges implies its relevance to environmental and climate-related issues.

- Equity. Emphasizing inclusive AI development, the order stresses diverse stakeholder involvement, suggesting a commitment to equity considerations.

- Job Training Programs. Though not explicitly outlined, the necessity for robust evaluations of AI systems implies a potential demand for training programs to ensure workforce preparedness.

- Tech and Climate Literacy. While not directly addressed, the emphasis on ethical AI development implies a requisite level of literacy within the federal workforce. Additionally, efforts to establish effective labeling mechanisms for AI-generated content could contribute to tech literacy across the general population.

Please note that this analysis is based on provided excerpts, and the full documents may contain additional relevant insights.

Technical Assistance Guidance: Creating Green or Climate Jobs

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are poised to create green or climate jobs, strengthen equity, and bolster job training programs, signaling a concerted effort towards enhancing tech and climate literacy across the workforce and the general U.S. population.

Creating Green or Climate Jobs

Both the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are anticipated to generate green or climate jobs. The BIL aims to enhance the nation’s resilience to extreme weather and climate change, concurrently mitigating greenhouse gas emissions. Similarly, the IRA is forecasted to yield over 9 million quality jobs in the forthcoming decade.

Considering Equity

Both the BIL and the IRA prioritize equity in their provisions. The BIL endeavors to bridge historically disadvantaged and underserved communities to job opportunities and economic empowerment. Similarly, the IRA addresses energy equity through its climate provisions and investment tax credits in renewable energy.

Strengthening Job Training Programs

Both legislations incorporate provisions for enhancing job training programs. The BIL allocates over $800 million in dedicated investments towards workforce development, while the IRA mandates workforce development and apprenticeship requirements.

Increasing Tech and Climate Literacy within the Federal Workforce

Although explicit information on boosting tech and climate literacy within the federal workforce is lacking, both the BIL and the IRA include provisions for workforce development and training. These initiatives could potentially encompass tech and climate literacy training.

Increasing Tech and Climate Literacy in the General U.S. Population

The substantial investments in clean energy and climate mitigation under the BIL and the IRA may indirectly contribute to enhancing tech and climate literacy across the general U.S. populace. However, there is no specific information regarding programs aimed at directly augmenting tech and climate literacy in the general population.

III. Report Summaries

Insights from various reports shed light on the demand for tech and green jobs, digital skills, and challenges in the broadband workforce. Drawing from reputable sources such as Bank of America, BCG, the Federal Reserve of Atlanta, and others, these summaries emphasize the necessity for targeted educational and policy interventions.

- Bank of America NPower. Provides tech training programs for high school graduates lacking necessary skills and connections for tech careers. Offers a blend of classes and practical experience partnering with programs like Year Up, NPower, and Road to Hire.

- BCG Future of Jobs in AI. Highlights discrepancies between labor supply and demand in various sectors, particularly in tech-related occupations. Foresees significant worker deficits in computer-related fields due to automation’s pervasive impact.

- Federal Reserve of Atlanta Digital Skills Report. Reveals that 92% of jobs require digital skills, yet the supply of skilled workers is insufficient. Urges policymakers and educators to collaborate to bridge the digital skills gap through accessible training and education.

- National Skills Coalition Report. Discusses the digital skill divide and advocates for policies supporting skill development. Recommends investing in training programs and ensuring access to education tailored to the digital economy’s demands.

- Benton Broadband Workforce Report. Examines challenges in broadband rollout and underscores the need for training programs and education to meet digital economy demands.

- Forbes Demand Outpacing Supply For Green Jobs Skills. Highlights the mismatch between demand and supply for green skills, urging investment in training programs and education for success in the green economy.

- Global Green Skills Report (LinkedIn). Provides insights into the importance of green skills in transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Emphasizes the necessity of policies supporting green skills development.

- IMF. How the green transition will impact U.S. Jobs: Explores the impact of the green transition on U.S. jobs, predicting both job creation in renewable energy and losses in the fossil fuel sector. Recommends investment in training programs for success in the green economy.

These reports collectively underscore the growing demand for digital and green skills in the U.S. workforce, accompanied by a shortage of skilled workers. Collaboration between policymakers and educators is essential to provide adequate training and education for success in the digital and green economies.

IV. Digital Discrimination Reports

This section delves into findings from reports on digital discrimination, broadband access, and AI literacy, sourced from reputable institutions such as The Markup, Consumer Reports, Pew, and the World Economic Forum. These reports illuminate the inequities present in digital access and knowledge and emphasize the necessity for equitable policies to foster widespread participation in the digital economy.

- The Markup. Highlights how internet service providers often charge different prices for the same service based on geographic location, arguing for government regulation to ensure affordable internet access for all.

- Consumer Reports. Discusses the inadequate state of broadband access in the U.S., emphasizing the necessity of affordable, high-speed internet for full participation in the digital economy. Recommends policy interventions to invest in broadband infrastructure and ensure equitable access for all Americans.

- Pew Report on Americans’ Knowledge Level on AI. Examines Americans’ understanding of AI, cybersecurity, and big tech, revealing significant gaps in knowledge that could impact future work prospects. Recommends investment in education and training programs to equip workers with necessary digital skills for success in the digital economy.

- World Economic Forum Future of Jobs Report. Forecasts technology adoption as a key driver of business transformation, with over 85% of organizations anticipating increased adoption of new technologies and broader digital access. Emphasizes the need for Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) standards and discusses significant job creation and destruction effects driven by environmental, technological, and economic trends.

These reports collectively underscore the urgent need for policies supporting digital skill development and ensuring affordable, high-speed internet access across the U.S. Policymakers are urged to collaborate in providing necessary training and education opportunities to empower workers for success in the digital economy.

V. CRS Report Summaries

This section provides a synopsis of Congressional Research Service (CRS) reports addressing skills gaps, broadband considerations, job training programs, and economic assistance for transitioning communities. These reports offer insights into legislative and policy contexts for bridging digital divides and supporting transitions to green economies, with a focus on workforce development and economic assistance.

- Skills Gaps. A Review of Underlying Concepts and Evidence: Explores the complex nature of skills gaps and their impact, attributing them to various factors such as technological advancements and demographic shifts. Recommends investment in training programs to equip workers for success in digital and green economies.

- Bridging the Digital Divide. Broadband Workforce Considerations for the 118th Congress: Discusses the inadequate access to affordable, high-speed internet in the U.S. and recommends policy interventions to invest in broadband infrastructure and ensure universal access.

- The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (P.L. 117-58). Summary of the Broadband Provisions in Division F: Summarizes broadband provisions in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, emphasizing its role in narrowing the digital divide through infrastructure investment and expanded internet access.

- Federal Youth Employment and Job Training Programs. Highlights the importance of federal youth employment and job training programs in preparing young individuals for success in digital and green economies. Recommends increased investment in these programs to support skill development.

- Federal Economic Assistance For Coal Communities. Explores federal economic assistance for coal communities, emphasizing the need to transition workforce skills from coal-related jobs to other industries. Recommends investment in training programs and removal of barriers to labor mobility.

- Economic Development Administration Announces Phase 1 of New Tech Hubs Program. Discusses the Economic Development Administration’s Tech Hubs Program aimed at fostering regional technology ecosystems for economic growth. Recommends policymakers invest in such programs to bolster digital and green economies.

Overall, these reports underscore the necessity for policies supporting the development of digital and green skills, as well as ensuring equitable access to high-speed internet across the U.S. Policymakers are urged to collaborate in providing necessary training and education opportunities to empower workers for success in evolving economic landscapes.

Revitalizing Federal Jobs Data: Unleashing the Potential of Emerging Roles

Emerging technologies and creative innovation are pivotal economic pillars for the future of the United States. These sectors not only promise economic growth but also offer avenues for social inclusion and environmental sustainability. However, the federal government lacks reliable and comprehensive data on these sectors, which hampers its ability to design and implement effective policies and programs. A key reason for this data gap is the outdated and inadequate job categories and classifications used by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

The BLS is the main source of official statistics on employment, wages, and occupations in the U.S. Part of the agency’s role is to categorize different industries, which helps states, researchers and other outside parties measure and understand the size of certain industries or segments of the economy. Another BLS purpose is to use the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) system to categorize and define jobs based on their duties, skills, and education requirements. This is how all federal workers and contracted federal workers are classified. For an agency to create and fill a role, it needs a classification or SOC. State and private employers also use the classifications and data to allocate funding and determine benefits related to different kinds of positions.

Where no classification (SOC) or job exists, it is unclear whether hiring and contracting happen according to programmatic intent and in a timely manner. This is particularly concerning to some employers and federal agencies that need to align numerous jobs with the provisions of Justice 40, the Inflation Reduction Act and the newly created American Climate Corps. Many of the roles imagined by the American Climate Corps do not have classifications. This poses a significant barrier for effective program and policy design related to green and tech jobs.

The SOC system is updated roughly once every 10 years. There is not a set comprehensive review schedule for that or the industry categories. Updates are topical, with the last broad revision taking place in 2018. Unemployment reports and data related to wages are updated annually, and other topics less predictably. Updates and work on the SOC systems and categories for what are broadly defined as “green jobs” stopped in 2013 due to sequestration. This means that the BLS data may not capture the current and future trends and dynamics of the green and innovation economies, which are constantly evolving and growing.Because the BLS does not have a separate category for green jobs, it identifies them based on a variety of industry and occupation codes. The range spans restaurant industry SOCs to construction. Classifying positions this way cannot reflect the cross-cutting and interdisciplinary nature of green jobs. Moreover, the process may not account for the variations and nuances of green jobs, such as their environmental impact, social value, and skill level. For example, if you want to work with solar panels, there is a construction classification, but nothing for community design, specialized finance, nor any complementary typographies needed for projects at scale.

Similarly, the BLS does not have a separate category for tech jobs. It identifies them based on the “Information and Communication Technologies” occupational groups of the SOC system. Again, this approach may not adequately reflect the diversity and complexity of tech jobs, which may involve new and emerging skills and technologies that are not yet recognized by the BLS. There are no classifications for roles associated with machine learning or artificial intelligence. Where the private sector has a much-discussed large language model trainer role, the federal system has no such classification. Appropriate skills matching, resource allocation, and the ability to measure the numbers and impacts of these jobs on the economy will be difficult if not impossible to fully understand. Classifying tech jobs in this manner may not account for the interplay and integration of tech jobs with other sectors, such as health care, education, and manufacturing.

These data limitations have serious implications for policy design and evaluation. Without accurate and timely data on green and tech jobs, the federal government may not be able to assess the demand and supply of these jobs, identify skill gaps and training needs, allocate resources, and measure the outcomes and impacts of its policies and programs. This will result in missed opportunities, wasted resources, and suboptimal outcomes.

There is a need to update the BLS job categories and classifications to better reflect the realities and potentials of the green and innovation economies. This can be achieved by implementing the following strategic policy measures:

- Inter-Agency Collaboration: Establish an inter-agency task force, including representatives from the BLS, Department of Energy (DOE), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Department of Education (ED), and the Department of Commerce (DOC), to review and update the current job categories and classifications. This task force would be responsible for ensuring that the classifications accurately reflect the evolving nature of jobs in the green and innovation economies.

- Public-Private Partnerships: Engage in public-private partnerships with industry leaders, academic institutions, and non-profit organizations. These partnerships can provide valuable insights into the changing job landscape and help inform the update of job categories and classifications. They can also facilitate the dissemination and adoption of the updated classifications among employers and workers, as well as the development and delivery of training and education programs related to green and tech jobs.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Conduct regular consultations with stakeholders, including educational institutions, employers, workers, and unions in the green and innovation economies. Their input can ensure that the updated classifications accurately represent the realities and challenges of the job market. They can also provide feedback and suggestions on how to improve the quality and accessibility of the BLS data.

- Regular Updates: Implement a policy for regular reviews and updates of job categories and classifications. The policy should also specify the frequency and criteria for the updates, as well as the roles and responsibilities of the involved agencies and partners.

By updating the BLS job categories and classifications, the federal government can ensure that its data and statistics accurately reflect the current and future job market, thereby supporting effective policy design and evaluation related to green and tech jobs. Accurate and current data that mirrors the ever-evolving job market will also lay the foundation for effective policy design and evaluation in the realms of green and tech jobs. This commitment can contribute to the development of a workforce that not only meets economic needs but also aligns with the nation’s environmental aspirations.

Moving the Needle on STEM Workforce Development through Fellowships and Mentorship Support in the CHIPS and Science Act

The CHIPS and Science Act ushered in unprecedented opportunities for American manufacturing, science, and innovation – and yet, current underfunding leaves the outcomes at risk.

The legislation directs the federal government to invest $280 billion to bolster U.S. semiconductor capacity, catalyze R&D, create regional high-tech hubs, and develop a larger, more inclusive STEM workforce. The federal investment of $50 billion in semiconductor manufacturing is estimated to add $24.6 billion annually to the American economy and create 185,000 jobs from 2021 to 2026. However, at the current rate of STEM degree completion, the U.S. may not be able to produce enough qualified workers to fill these jobs. Left unaddressed, this labor market gap will have cascading effects on the U.S. economy and compromise the nation’s global competitiveness.

Supporting STEM Workforce Development by Expanding Fellowship and Mentorship Programs

Despite the progress that has been made in recent years to grow the STEM pipeline, STEM graduates continue to lack the opportunity to contribute to the research enterprise and are not equipped to translate their scientific knowledge into actionable policy solutions. The CHIPS and Science Act attempts to address the shortfall in the U.S. STEM workforce and create more career pathways for graduates by authorizing federal agencies to expand their fellowship programs.

For example, the legislation directs the National Science Foundation (NSF) to expand the number of new graduate research fellows supported annually over the next 5 years to no fewer than 3,000 fellows. This provision echoes the recommendations from a 2021 Federation of American Scientists (FAS) policy memo calling for the expansion of the Graduate Research Fellowship Program in order to catalyze and train a new workforce that would maintain America’s leading edge in the industries of the future. Another important provision has led to the launch of NSF’s Entrepreneurial Fellowships in September 2022, with the goal of supporting STEM entrepreneurs from diverse backgrounds in turning breakthroughs from the laboratory into products and services that benefit society.

In addition to fellowships, the legislation also includes federal funding for graduate student and postdoctoral research mentorship and professional development, which are critical elements to developing our nation’s research enterprise. Supportive mentors and advisors can guide career planning for future scientists and help them develop the necessary critical thinking and problem solving skills. This is also the case for students from underrepresented minority backgrounds (URMs), where positive research and mentorship experiences contribute to persistence in intention to pursue a STEM career following graduation.

While these provisions are promising, more can be done to ensure better oversight and support of mentorship programs within federal funded research programs. The GRAD Coalition, which was established to support the Congressional Graduate Research and Development Caucus, has called on Congress to expand mentorship oversight and support, specifically to:

- Provide systematic oversight of graduate student mentorship. For example, survey mentorship experiences at the national level or mandate institutional data collection and reporting on graduate student advising;

- Develop incentive structures that support effective mentorship practices. For example, mentorship training programs that grant meaningful certification;

- Expand the mentorship plan mandate for funding proposals to include all federal agencies that fund graduate student research. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 provisions concerning graduate student advising only apply to grants administered under the National Science Foundation (NSF). However, graduate students and their advisors rely on funding from many federal agencies outside the NIH and NSF, which do not currently mandate mentorship plans.

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) has long recognized the need for mentorship at the post-doctoral level. In 2023,the NIH Advisory Committee to the Director (ACD) Working Group on Re-envisioning NIH-Supported Postdoctoral Training held listening sessions resulting in a report detailing many aspects of the postdoctoral experience in biomedical fields: lack of adequate compensation, concerns about postdoctoral quality of life and challenges with diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility. Many of these postdoctoral issues have been known for some time but continue to be insufficiently addressed. The report calls for increasing oversight and accountability of faculty for mentoring, specifically for NIH to:

- Provide more detailed mentorship requirements in requests for applications, expand the Individual Development Plan (IDP), and require that the IDP be regularly updated as part of the project progress report;

- Weigh principal investigator (PI) performance in postdoc mentoring and career development equally with research progress as criteria for continued funding, and require/encourage mentoring contracts and support acquiring and transferring mentoring tools from PI to postdoc;

- Increase transparency of PIs’ postdoc mentorship track records. Institutions should be required to record and report clearly on department websites the names of each postdoc and their next position;

- Require mentoring committees to ensure that postdocs receive all types of mentoring needed.

While boosts for science and education provisions in the legislation have been authorized, funding for the “and science” portion of the act has fallen short in several areas. FAS analysis shows that the FY 2024 appropriations for NSF are approximately $6 billion-short or 39% below the CHIPS and Science authorization levels, which has the potential to set the U.S. back in several areas of science and technology.

Maintaining the U.S. scientific and research enterprise requires a whole-of-government approach. Expanding fellowship programs and better incorporating mentorship in federal-funded programs can have far-reaching consequences for the STEM pipeline and maintaining our nation’s edge in scientific research and innovation. The CHIPS and Science Act provides specific opportunities for federal agencies, Congress, and the executive branch to grow the U.S. STEM workforce pipeline by expanding fellowships and mentorship support for graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. Our nation’s global leadership in science and technology is dependent upon the research and innovation driven by graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, and fully funding the authorized programs and new initiatives in the CHIPS and Science Act will help ensure that this trend continues.

State of the Federal Clean Energy Workforce

How Improved Talent Practices Can Help the Department of Energy Meet the Moment

This report aims to provide a snapshot of clean energy talent at the Department of Energy and its surrounding orbit: the challenges, successes, and opportunities that the workforce is experiencing at this once-in-a-generation moment.

To compile the findings in this report, FAS worked with nonprofit and philanthropic organizations, government agencies, advocacy and workforce coalitions, and private companies over the last year. We held events, including information sessions, recruitment events, and convenings; we conducted interviews with more than 25 experts from the public and private sector; we developed recommendations for improving talent acquisition in government, and helped agencies find the right talent for their needs.

Overall, we found that DOE has made significant progress towards its talent and implementation goals, taking advantage of the current momentum to bring in new employees and roll out new programs to accelerate the clean energy transition. The agency has made smart use of flexible hiring mechanisms like the Direct Hire Authority and Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) agreements, ramped up recruitment to meet current capacity needs, and worked with partners to bring in high-quality talent.

But there are also ways to build on DOE’s current approaches. We offer recommendations for expanding the use of flexible hiring mechanisms: through expanding IPA eligibility to organizations vetted by other agencies, holding trainings for program offices through the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer, and asking Congress to increase funding for human capital resources. Another recommendation encourages DOE to review its use to date of the Clean Energy Corps’ Direct Hire Authority and identify areas for improvement. We also propose ways to build on DOE’s recruitment successes: by partnering with energy sector affinity groups and clean energy membership networks to share opportunities; and by building closer relationships with universities and colleges to engage early career talent.

Some of these findings and recommendations are pulled from previous memos and reports, but many are new recommendations based on our experiences working and interacting with partners within the ecosystem over the past year. The goal of this report is to help federal and non-federal actors in the clean energy ecosystem grow talent and prepare for the challenges in clean energy in the coming decades.

The Moment

The climate crisis is not just a looming threat–it’s already here, affecting the lives of American citizens. The federal government has taken a central role in climate mitigation and adaptation, especially with the recent passage of several pieces of legislation. The bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) all provide levers for federal agencies to address the crisis and reduce emissions.

The Department of Energy (DOE) is leading the charge and is the target of much of the funding from the above bills. The legislation provides DOE over $97 billion dollars of funding aimed at commercializing and deploying new clean energy technologies, expanding energy efficiency in homes and businesses, and decreasing emissions in a range of industries.

These are robust and much-needed investments in federal agencies, and the effects will ripple out across the whole economy. The Energy Futures Initiative, in a recent report, estimated that IRA investments will lead to 1.46 million more jobs over the next ten years than there would have been without the bill. Moreover, these jobs will be focused in key industries, like construction, manufacturing, and electric utilities.

But those jobs won’t magically appear–and the IIJA and IRA funding won’t magically be spent. That amount of money would be overwhelming for any large organization, and initiatives and benefits will take time to manifest.

When it passed these two bills, Congress recognized that the Department of Energy–and the federal government more broadly– would need new tools to use these new resources effectively. That is why it included new funding and expanded hiring authorities to allow the agencies to quickly find and hire expert staff.

Now it is up to DOE to find the subject matter expertise, talent, partnerships, and cross-sector knowledge sharing from the larger clean energy ecosystem it needs to execute on Congress’s incredibly ambitious goals. Perhaps the most critical factor in DOE’s success will be ensuring that the agency has the staff it needs to meet the moment and implement the bold targets established in the recent legislation.

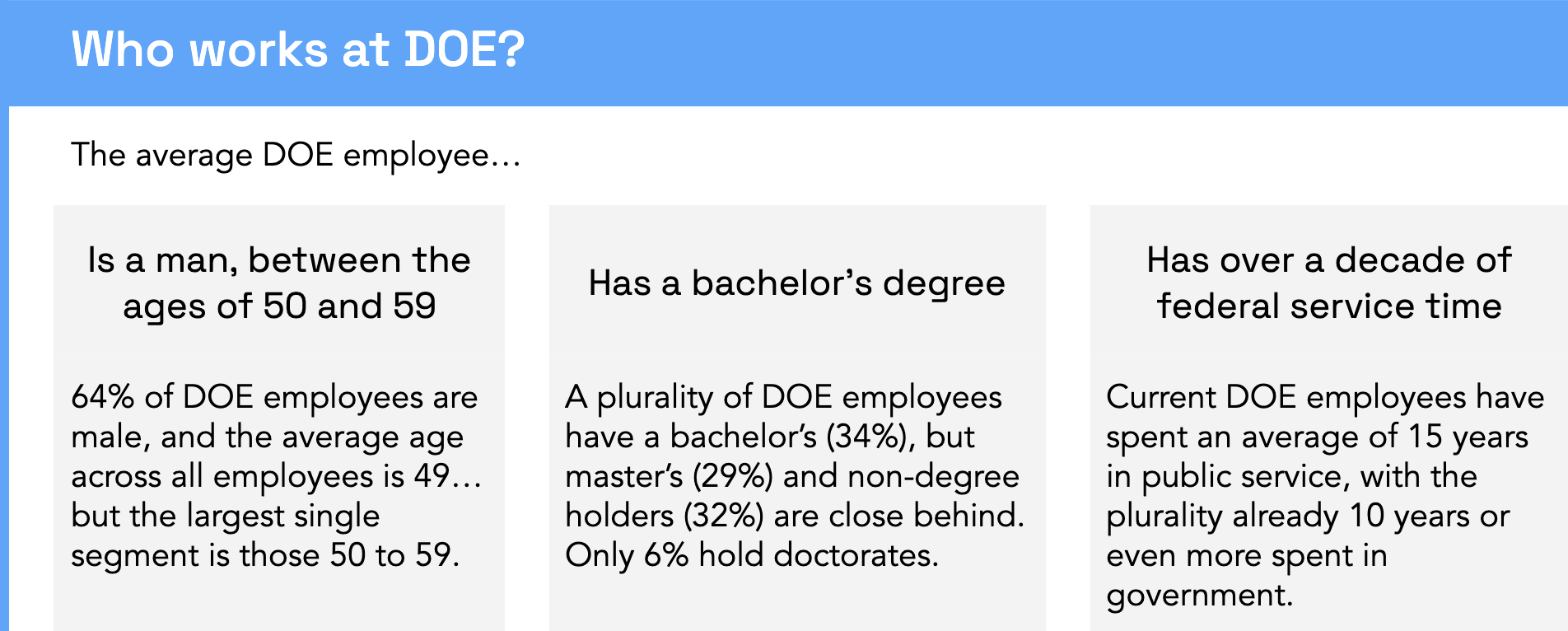

Why Talent?

To implement policy effectively and spend taxpayer dollars efficiently, the federal government needs people. Investing in a robust talent pipeline is important for all agencies, especially given that only about 8% of federal employees are under 30, and at DOE only 4% are under 30. Building this pipeline is critical for the clean energy transition that’s already underway–not only for not the federal government, but for the entire ecosystem. In order to meet clean energy deployment estimates across the country, clean energy jobs will need to increase threefold by 2025 and almost sixfold by 2030 from 2020 jobs numbers. This job growth will require cross-sector investment in workforce training and education, innovation ecosystems, and research and development of new technologies. Private firms, venture capital, and the civil sector can all play a role, but as the country’s largest employer, the government will need to lead the way.

To meet its ambitious policy goals, government agencies need to move beyond stale hiring playbooks and think creatively. Strategies like flexible hiring mechanisms can help the Department of Energy–and all federal agencies–meet urgent needs and begin to build a longer-term talent pipeline. Workforce development, recruitment, and hiring can take years to do right – but mechanisms like tour-of-service models (i.e. temporary or termed positions), direct hire authorities, and excepted service hiring allow agencies to retain talent quickly, overcome administrative bottlenecks, and access individuals with technical expertise who may not otherwise consider working in the public sector. See the Appendix for more information on specific hiring authorities.

This paper outlines insights, strategies, and opportunities for DOE’s talent needs based on the Federation of American Scientists’ (FAS) one-year pilot partnership with the department. Non-federal actors in the clean energy ecosystem can also benefit from this report–by understanding the different avenues into the federal government, civil society and private organizations can work more effectively with DOE to shepherd in the clean energy revolution.

Broadly, we hope that our experience working with DOE can serve as a case study for other federal agencies when considering the challenges and opportunities around talent recruitment, onboarding, and retention.

Where does DOE need talent?

While the IRA and IIJA funded dozens of programs across DOE, there are several offices that received larger amounts of funding and have critical talent needs currently.

A Pilot Partnership: FAS and DOE Talent Efforts

In January 2022, FAS established a partnership with DOE to support the implementation of a broad range of ambitious priorities to stimulate a clean energy transition. Through a partnership with DOE’s Office of Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4), our team discovered unmet talent needs and worked with S4 to develop strategies to address hiring challenges posed by DOE’s rapid growth through the IIJA.

This included expanding FAS’s Impact Fellowship program to DOE. This program supports fellows who bring scientific and technical expertise to bear in the public domain, including within government. To date, through IPA (Intergovernmental Personnel Act) agreements, FAS has placed five fellows in high-impact positions in DOE, with another cohort of 5 fellows in the pipeline.

FAS Impact Fellows placed at DOE have proven that this mechanism can have a positive impact on government operations. Current Fellows work in a number of DOE offices, using their expertise to forward work on emerging clean energy technologies, facilitate the transition of energy communities from fossil fuels to clean energy, and ensure that DOE’s work is communicated strategically and widely, among other projects. In a short time, these fellows have had a large impact–they are bringing expertise from outside government to bear in their roles at the agency.

In addition to placing fellows, FAS has worked to evangelize DOE’s Clean Energy Corps by actively recruiting, holding events, and advertising for specific roles within DOE. To more broadly support hiring and workforce development at the agency, we piloted a series of technical assistance projects in coordination with DOE, including hiring webinars and cross-sector roundtables with leaders in the agency and the larger clean energy ecosystem.

From this work, FAS has learned more about the challenges and opportunities of talent acquisition–from flexible hiring mechanisms to recruitment–and has developed several recommendations for both Congress and DOE to strengthen the federal clean energy workforce.

Flexible Hiring Mechanisms

One key lesson from the past year of work is the importance of flexible hiring mechanisms broadly. This includes special authorities like the Direct Hire Authority, but also includes tour-of-service models of employment. A ‘tour-of-service’ position can take many forms, but generally is a termed or temporary position, often full-time and focused on a specific project or set of projects. In times of urgency, like the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic or following the passage of large pieces of new legislation, hiring managers may need high numbers of staff in a short amount of time to implement policy–a challenge often heightened by stringent federal hiring guidelines.

Traditional federal hiring is frustrating for both sides. For applicants, filling out applications is complicated and jargony and the wait times are long and unpredictable. For offices, resources are scarce, there are seemingly endless legal and administrative hoops to jump through, and the wait times are still long and unpredictable. In general, tour-of-service hiring mechanisms offer a way to hire key staff for specific needs more quickly, while offering many other unique benefits, including, but not limited to, cross-sector knowledge sharing, professional development, recruitment tools, and relationship-building.

These mechanisms can also expand the potential talent pool for a particular position–highly trained technical professionals can prove difficult to recruit on a full-time basis, but temporary positions may be more attractive to them. IPA agreements, for example, can last for 1-2 years and take less time to execute than hiring permanent employees or contractors. More generally, all types of flexible hiring authorities can give agencies quicker ways of hiring highly qualified staff in sometimes niche fields. Flexible hiring mechanisms can also reduce the barrier to entry for professionals not as familiar with federal hiring processes–broadening offices’ reach and increasing the diversity of applicants.

FAS’s work with DOE has demonstrated these benefits. With FAS and other organizations, DOE has successfully used IPAs to staff high-impact positions. More recommendations on the use of IPAs specifically can be found in a later section. Through its Impact Fellowship, FAS has yielded successful case studies of how cross-sector talent can support impactful policy implementation in the department.

DOE should expand awareness and use of flexible hiring mechanisms.

DOE should work to expand the awareness and use of flexible hiring mechanisms in order to bring in more highly skilled employees with cross-sector knowledge and experience. This could be achieved in a number of ways. The Office of the Chief Human Capital Office (CHCO) should continue to educate hiring managers across DOE about potential hiring authorities available: they could offer additional trainings on different mechanisms and work with OPM to identify opportunities for new authorities. There are existing communities of practice for recruitment and other talent topics at DOE, and hiring officials can use these to discuss best practices and challenges around using hiring authorities effectively.

DOE can also look to other agencies for ideas on innovative hiring. Agencies like the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, and Department of Veterans Affairs run different forms of industry exchange programs that allow private sector experts to bring their skills and knowledge into government and vice versa. Another example is the Joint Statistical Research Program hosted by the Internal Revenue Service’s Statistics of Income Office. This program brings in tax policy experts on term appointments using the IPA mechanism, similar to the National Science Foundation’s Rotator program. Once developed, these programs can allow agencies to benefit from talent and expertise from a larger pool and access specialized skill sets while protecting against conflicts of interest.

DOE should partner with external organizations to champion tour-of-service programs.

There are other ways to expand flexible hiring mechanism use as well. Program offices and the Office of the CHCO can partner with outside organizations like FAS to champion tour-of-service programs in the wider clean energy community, in order to educate non-federal eligible parties on how they can get involved. Federal hiring processes can seem opaque to outside organizations, with additional paperwork, conflict of interest concerns, long timelines, and potential clearance hurdles. If outside organizations better understand the different ways they can partner with agencies and the benefits of doing so, agencies could increase enthusiasm for programs like tour-of-service hiring. At NSF, for example, the Rotator program is well known in the communities it operates within–both academia and government understand the benefits of participating.

Although these mechanisms and authorities have significant medium- and long-term benefits for agencies, they require upfront administrative effort and cost. Even if staff are aware of potential tools they can use, understanding the logistics, funding mechanisms, conflict of interest regulations, and recruitment and placement of staff hired through these mechanisms often requires investment of time and money from the agency side and can overwhelm already stressed hiring managers.

Congress should increase funding for DOE’s Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer.

In order to support DOE in using flexible hiring mechanisms more effectively, Congress should direct more funding to the agency’s Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer. In FY23, the office has not only continued to execute on mandates from the IIJA and the IRA, but has introduced new programs aimed at modernizing the office and improving on hiring. These programs and tools, including standing up talent teams to better assess competency gaps across program offices and developing HR IT platforms to more effectively make data-driven personnel decisions, are vital to the growth of the office and in turn the ability of DOE to follow through on key executive priorities. Congress should increase funding to DOE’s Human Capital office by $10M in FY24 over FY23 levels. As IRA and IIJA priorities continue to be rolled out, the Human Capital office will remain pivotal to the agency’s success.

Congress should increase DOE’s baseline program direction funds.

A related recommendation is for Congress to further support hiring at DOE by increasing the base budget of program direction funds across agency offices. Restrictions on this funding limits the agency’s ability to hire and the number of employees it can bring on. When offices are limited in the number of staff they can hire, they have tended to bring on more senior employees. This helps achieve the agency’s mission but limits the overall growth of the agency – without early career talent, offices are unable to train a new generation of diverse clean energy leaders. Increasing program direction budgets through the annual appropriations process will allow DOE to have more flexibility in who they hire, building a stronger workforce across the agency.

Clean Energy Corps and the Direct Hire Authority

Expanded Direct Hire Authority has been a boon for DOE, despite some implementation challenges. Congress included DHA in the IIJA, in order to help federal agencies quickly add staff to implement the legislation. In response, DOE set an initial goal of hiring over 1,000 new employees in its Clean Energy Corps, which encompasses all DOE staff who work on clean energy and climate. DOE also requested an additional authority for supporting implementation of the IRA through OPM. To date, the program has received almost 100,000 applications and has hired nearly 700 employees. We have heard positive feedback from offices across the agency about how the DHA has helped hire qualified staff more quickly than through traditional hiring. It has allowed DOE offices to take advantage of the momentum in the clean energy movement right now and made it easier for applicants to show their interest and move through the hiring process. To date, among federal agencies with IIJA/IRA direct hire authorities, DOE has been an exemplar in implementation.

The Direct Hire Authority has been successful so far in part because of its advertisement; there was public excitement about the climate impact of the IIJA and IRA, and DOE took advantage of the momentum and shared information about the Clean Energy Corps widely, including through partnerships with non-governmental entities. For example, FAS and Clean Energy for America held hiring webinars, and other organizations and individuals have continued to share the announcement.

Congress should extend the Direct Hire Authority.

Congress should consider extending the authority past its current timeline. The agency’s direct hire authority under the IIJA expires in 2027, while its authority requested through OPM expires at the end of 2025 – and is capped at only 300 positions. With DOE taking on more demonstration and deployment activities as well as increased community and stakeholder engagement with the passage of the IIJA and IRA, the agency needs capacity–and the Direct Hire Authority can help it get the specialized resources it needs. Extending the authority beyond 2025 and requesting that OPM increase the cap on positions is more urgent, but the authority should continue past 2027 as well, to ensure that DOE can continue to hire effectively.

Congress should expand the breadth of DHA.

Additionally, Congress should expand the authority to other offices across DOE. It is currently limited to certain roles and offices, but there are additional opportunities within the department to support the clean energy transition that don’t have access to DHA. This is especially important given that offices with the direct hire authority can pull employees from offices without–leaving the latter to backfill positions on a much longer timeline using conventional merit hiring practices. Expanding the authority would support the development of the agency as a whole.

Beyond just removing the authority’s cap on roles supporting the IRA, expansions or extensions of the authority should increase the number of authorized positions to account for a baseline attrition rate. The authority limits the number of positions that can be filled – once that number of staff is hired, the authority can no longer be used for that office or agency. As with any workplace, federal agencies experience a normal amount of attrition, but the stakes are higher when direct hire employees leave the organization because of the authority’s constraints. Any authorization of the DHA in the future should consider how attrition will impact actual hires over the authorization period.

In order to bolster support for expanding the authority, DOE can take steps to share out successes of the program. The DHA has been a huge win for federal clean energy hiring, and publicizing news about related programs, offices, funding opportunities, and employees that would not exist but for the support of the Clean Energy Corps would help make the connection between flexible hiring and government effectiveness and would generate excitement about DOE’s activities in the general public.

DOE should highlight success stories of the Clean Energy Corps.

As part of a larger external communications strategy, DOE should highlight success stories of current employees hired through the Clean Energy Corps portal. These spotlights could focus on projects, partnerships, or funding opportunities that employees contributed to and put a face to the achievements of the Clean Energy Corps thus far. Not only would this encourage future high-quality applicants and ensure continued interest in the program, but would also advertise to Congress and the general public that the authority is successful and increase support for more flexible hiring authorities and clean energy funding.

There are also some opportunities to improve DOE’s use of the authority and make it even more effective. With so many applications, hiring managers and program offices are often overwhelmed by sheer volume – leading to long wait times for applicants. Some offices at DOE have tried to address this bottleneck by building informal processes to screen and refer candidates–using their internal system to identify qualified applicants and sharing those applications with other program offices. But there may be additional ways to reduce the backlog of applications.