State of the Federal Clean Energy Workforce

How Improved Talent Practices Can Help the Department of Energy Meet the Moment

This report aims to provide a snapshot of clean energy talent at the Department of Energy and its surrounding orbit: the challenges, successes, and opportunities that the workforce is experiencing at this once-in-a-generation moment.

To compile the findings in this report, FAS worked with nonprofit and philanthropic organizations, government agencies, advocacy and workforce coalitions, and private companies over the last year. We held events, including information sessions, recruitment events, and convenings; we conducted interviews with more than 25 experts from the public and private sector; we developed recommendations for improving talent acquisition in government, and helped agencies find the right talent for their needs.

Overall, we found that DOE has made significant progress towards its talent and implementation goals, taking advantage of the current momentum to bring in new employees and roll out new programs to accelerate the clean energy transition. The agency has made smart use of flexible hiring mechanisms like the Direct Hire Authority and Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) agreements, ramped up recruitment to meet current capacity needs, and worked with partners to bring in high-quality talent.

But there are also ways to build on DOE’s current approaches. We offer recommendations for expanding the use of flexible hiring mechanisms: through expanding IPA eligibility to organizations vetted by other agencies, holding trainings for program offices through the Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer, and asking Congress to increase funding for human capital resources. Another recommendation encourages DOE to review its use to date of the Clean Energy Corps’ Direct Hire Authority and identify areas for improvement. We also propose ways to build on DOE’s recruitment successes: by partnering with energy sector affinity groups and clean energy membership networks to share opportunities; and by building closer relationships with universities and colleges to engage early career talent.

Some of these findings and recommendations are pulled from previous memos and reports, but many are new recommendations based on our experiences working and interacting with partners within the ecosystem over the past year. The goal of this report is to help federal and non-federal actors in the clean energy ecosystem grow talent and prepare for the challenges in clean energy in the coming decades.

The Moment

The climate crisis is not just a looming threat–it’s already here, affecting the lives of American citizens. The federal government has taken a central role in climate mitigation and adaptation, especially with the recent passage of several pieces of legislation. The bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) all provide levers for federal agencies to address the crisis and reduce emissions.

The Department of Energy (DOE) is leading the charge and is the target of much of the funding from the above bills. The legislation provides DOE over $97 billion dollars of funding aimed at commercializing and deploying new clean energy technologies, expanding energy efficiency in homes and businesses, and decreasing emissions in a range of industries.

These are robust and much-needed investments in federal agencies, and the effects will ripple out across the whole economy. The Energy Futures Initiative, in a recent report, estimated that IRA investments will lead to 1.46 million more jobs over the next ten years than there would have been without the bill. Moreover, these jobs will be focused in key industries, like construction, manufacturing, and electric utilities.

But those jobs won’t magically appear–and the IIJA and IRA funding won’t magically be spent. That amount of money would be overwhelming for any large organization, and initiatives and benefits will take time to manifest.

When it passed these two bills, Congress recognized that the Department of Energy–and the federal government more broadly– would need new tools to use these new resources effectively. That is why it included new funding and expanded hiring authorities to allow the agencies to quickly find and hire expert staff.

Now it is up to DOE to find the subject matter expertise, talent, partnerships, and cross-sector knowledge sharing from the larger clean energy ecosystem it needs to execute on Congress’s incredibly ambitious goals. Perhaps the most critical factor in DOE’s success will be ensuring that the agency has the staff it needs to meet the moment and implement the bold targets established in the recent legislation.

Why Talent?

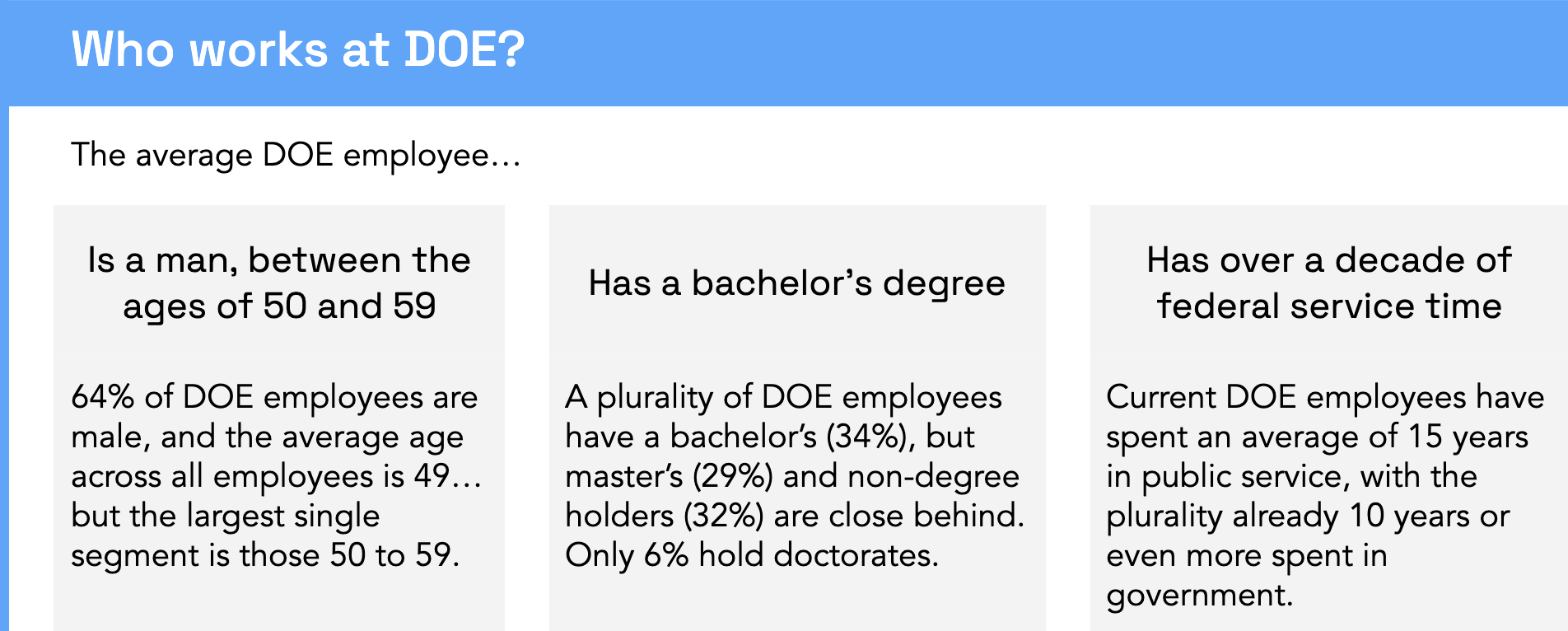

To implement policy effectively and spend taxpayer dollars efficiently, the federal government needs people. Investing in a robust talent pipeline is important for all agencies, especially given that only about 8% of federal employees are under 30, and at DOE only 4% are under 30. Building this pipeline is critical for the clean energy transition that’s already underway–not only for not the federal government, but for the entire ecosystem. In order to meet clean energy deployment estimates across the country, clean energy jobs will need to increase threefold by 2025 and almost sixfold by 2030 from 2020 jobs numbers. This job growth will require cross-sector investment in workforce training and education, innovation ecosystems, and research and development of new technologies. Private firms, venture capital, and the civil sector can all play a role, but as the country’s largest employer, the government will need to lead the way.

To meet its ambitious policy goals, government agencies need to move beyond stale hiring playbooks and think creatively. Strategies like flexible hiring mechanisms can help the Department of Energy–and all federal agencies–meet urgent needs and begin to build a longer-term talent pipeline. Workforce development, recruitment, and hiring can take years to do right – but mechanisms like tour-of-service models (i.e. temporary or termed positions), direct hire authorities, and excepted service hiring allow agencies to retain talent quickly, overcome administrative bottlenecks, and access individuals with technical expertise who may not otherwise consider working in the public sector. See the Appendix for more information on specific hiring authorities.

This paper outlines insights, strategies, and opportunities for DOE’s talent needs based on the Federation of American Scientists’ (FAS) one-year pilot partnership with the department. Non-federal actors in the clean energy ecosystem can also benefit from this report–by understanding the different avenues into the federal government, civil society and private organizations can work more effectively with DOE to shepherd in the clean energy revolution.

Broadly, we hope that our experience working with DOE can serve as a case study for other federal agencies when considering the challenges and opportunities around talent recruitment, onboarding, and retention.

Where does DOE need talent?

While the IRA and IIJA funded dozens of programs across DOE, there are several offices that received larger amounts of funding and have critical talent needs currently.

A Pilot Partnership: FAS and DOE Talent Efforts

In January 2022, FAS established a partnership with DOE to support the implementation of a broad range of ambitious priorities to stimulate a clean energy transition. Through a partnership with DOE’s Office of Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4), our team discovered unmet talent needs and worked with S4 to develop strategies to address hiring challenges posed by DOE’s rapid growth through the IIJA.

This included expanding FAS’s Impact Fellowship program to DOE. This program supports fellows who bring scientific and technical expertise to bear in the public domain, including within government. To date, through IPA (Intergovernmental Personnel Act) agreements, FAS has placed five fellows in high-impact positions in DOE, with another cohort of 5 fellows in the pipeline.

FAS Impact Fellows placed at DOE have proven that this mechanism can have a positive impact on government operations. Current Fellows work in a number of DOE offices, using their expertise to forward work on emerging clean energy technologies, facilitate the transition of energy communities from fossil fuels to clean energy, and ensure that DOE’s work is communicated strategically and widely, among other projects. In a short time, these fellows have had a large impact–they are bringing expertise from outside government to bear in their roles at the agency.

In addition to placing fellows, FAS has worked to evangelize DOE’s Clean Energy Corps by actively recruiting, holding events, and advertising for specific roles within DOE. To more broadly support hiring and workforce development at the agency, we piloted a series of technical assistance projects in coordination with DOE, including hiring webinars and cross-sector roundtables with leaders in the agency and the larger clean energy ecosystem.

From this work, FAS has learned more about the challenges and opportunities of talent acquisition–from flexible hiring mechanisms to recruitment–and has developed several recommendations for both Congress and DOE to strengthen the federal clean energy workforce.

Flexible Hiring Mechanisms

One key lesson from the past year of work is the importance of flexible hiring mechanisms broadly. This includes special authorities like the Direct Hire Authority, but also includes tour-of-service models of employment. A ‘tour-of-service’ position can take many forms, but generally is a termed or temporary position, often full-time and focused on a specific project or set of projects. In times of urgency, like the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic or following the passage of large pieces of new legislation, hiring managers may need high numbers of staff in a short amount of time to implement policy–a challenge often heightened by stringent federal hiring guidelines.

Traditional federal hiring is frustrating for both sides. For applicants, filling out applications is complicated and jargony and the wait times are long and unpredictable. For offices, resources are scarce, there are seemingly endless legal and administrative hoops to jump through, and the wait times are still long and unpredictable. In general, tour-of-service hiring mechanisms offer a way to hire key staff for specific needs more quickly, while offering many other unique benefits, including, but not limited to, cross-sector knowledge sharing, professional development, recruitment tools, and relationship-building.

These mechanisms can also expand the potential talent pool for a particular position–highly trained technical professionals can prove difficult to recruit on a full-time basis, but temporary positions may be more attractive to them. IPA agreements, for example, can last for 1-2 years and take less time to execute than hiring permanent employees or contractors. More generally, all types of flexible hiring authorities can give agencies quicker ways of hiring highly qualified staff in sometimes niche fields. Flexible hiring mechanisms can also reduce the barrier to entry for professionals not as familiar with federal hiring processes–broadening offices’ reach and increasing the diversity of applicants.

FAS’s work with DOE has demonstrated these benefits. With FAS and other organizations, DOE has successfully used IPAs to staff high-impact positions. More recommendations on the use of IPAs specifically can be found in a later section. Through its Impact Fellowship, FAS has yielded successful case studies of how cross-sector talent can support impactful policy implementation in the department.

DOE should expand awareness and use of flexible hiring mechanisms.

DOE should work to expand the awareness and use of flexible hiring mechanisms in order to bring in more highly skilled employees with cross-sector knowledge and experience. This could be achieved in a number of ways. The Office of the Chief Human Capital Office (CHCO) should continue to educate hiring managers across DOE about potential hiring authorities available: they could offer additional trainings on different mechanisms and work with OPM to identify opportunities for new authorities. There are existing communities of practice for recruitment and other talent topics at DOE, and hiring officials can use these to discuss best practices and challenges around using hiring authorities effectively.

DOE can also look to other agencies for ideas on innovative hiring. Agencies like the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, and Department of Veterans Affairs run different forms of industry exchange programs that allow private sector experts to bring their skills and knowledge into government and vice versa. Another example is the Joint Statistical Research Program hosted by the Internal Revenue Service’s Statistics of Income Office. This program brings in tax policy experts on term appointments using the IPA mechanism, similar to the National Science Foundation’s Rotator program. Once developed, these programs can allow agencies to benefit from talent and expertise from a larger pool and access specialized skill sets while protecting against conflicts of interest.

DOE should partner with external organizations to champion tour-of-service programs.

There are other ways to expand flexible hiring mechanism use as well. Program offices and the Office of the CHCO can partner with outside organizations like FAS to champion tour-of-service programs in the wider clean energy community, in order to educate non-federal eligible parties on how they can get involved. Federal hiring processes can seem opaque to outside organizations, with additional paperwork, conflict of interest concerns, long timelines, and potential clearance hurdles. If outside organizations better understand the different ways they can partner with agencies and the benefits of doing so, agencies could increase enthusiasm for programs like tour-of-service hiring. At NSF, for example, the Rotator program is well known in the communities it operates within–both academia and government understand the benefits of participating.

Although these mechanisms and authorities have significant medium- and long-term benefits for agencies, they require upfront administrative effort and cost. Even if staff are aware of potential tools they can use, understanding the logistics, funding mechanisms, conflict of interest regulations, and recruitment and placement of staff hired through these mechanisms often requires investment of time and money from the agency side and can overwhelm already stressed hiring managers.

Congress should increase funding for DOE’s Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer.

In order to support DOE in using flexible hiring mechanisms more effectively, Congress should direct more funding to the agency’s Office of the Chief Human Capital Officer. In FY23, the office has not only continued to execute on mandates from the IIJA and the IRA, but has introduced new programs aimed at modernizing the office and improving on hiring. These programs and tools, including standing up talent teams to better assess competency gaps across program offices and developing HR IT platforms to more effectively make data-driven personnel decisions, are vital to the growth of the office and in turn the ability of DOE to follow through on key executive priorities. Congress should increase funding to DOE’s Human Capital office by $10M in FY24 over FY23 levels. As IRA and IIJA priorities continue to be rolled out, the Human Capital office will remain pivotal to the agency’s success.

Congress should increase DOE’s baseline program direction funds.

A related recommendation is for Congress to further support hiring at DOE by increasing the base budget of program direction funds across agency offices. Restrictions on this funding limits the agency’s ability to hire and the number of employees it can bring on. When offices are limited in the number of staff they can hire, they have tended to bring on more senior employees. This helps achieve the agency’s mission but limits the overall growth of the agency – without early career talent, offices are unable to train a new generation of diverse clean energy leaders. Increasing program direction budgets through the annual appropriations process will allow DOE to have more flexibility in who they hire, building a stronger workforce across the agency.

Clean Energy Corps and the Direct Hire Authority

Expanded Direct Hire Authority has been a boon for DOE, despite some implementation challenges. Congress included DHA in the IIJA, in order to help federal agencies quickly add staff to implement the legislation. In response, DOE set an initial goal of hiring over 1,000 new employees in its Clean Energy Corps, which encompasses all DOE staff who work on clean energy and climate. DOE also requested an additional authority for supporting implementation of the IRA through OPM. To date, the program has received almost 100,000 applications and has hired nearly 700 employees. We have heard positive feedback from offices across the agency about how the DHA has helped hire qualified staff more quickly than through traditional hiring. It has allowed DOE offices to take advantage of the momentum in the clean energy movement right now and made it easier for applicants to show their interest and move through the hiring process. To date, among federal agencies with IIJA/IRA direct hire authorities, DOE has been an exemplar in implementation.

The Direct Hire Authority has been successful so far in part because of its advertisement; there was public excitement about the climate impact of the IIJA and IRA, and DOE took advantage of the momentum and shared information about the Clean Energy Corps widely, including through partnerships with non-governmental entities. For example, FAS and Clean Energy for America held hiring webinars, and other organizations and individuals have continued to share the announcement.

Congress should extend the Direct Hire Authority.

Congress should consider extending the authority past its current timeline. The agency’s direct hire authority under the IIJA expires in 2027, while its authority requested through OPM expires at the end of 2025 – and is capped at only 300 positions. With DOE taking on more demonstration and deployment activities as well as increased community and stakeholder engagement with the passage of the IIJA and IRA, the agency needs capacity–and the Direct Hire Authority can help it get the specialized resources it needs. Extending the authority beyond 2025 and requesting that OPM increase the cap on positions is more urgent, but the authority should continue past 2027 as well, to ensure that DOE can continue to hire effectively.

Congress should expand the breadth of DHA.

Additionally, Congress should expand the authority to other offices across DOE. It is currently limited to certain roles and offices, but there are additional opportunities within the department to support the clean energy transition that don’t have access to DHA. This is especially important given that offices with the direct hire authority can pull employees from offices without–leaving the latter to backfill positions on a much longer timeline using conventional merit hiring practices. Expanding the authority would support the development of the agency as a whole.

Beyond just removing the authority’s cap on roles supporting the IRA, expansions or extensions of the authority should increase the number of authorized positions to account for a baseline attrition rate. The authority limits the number of positions that can be filled – once that number of staff is hired, the authority can no longer be used for that office or agency. As with any workplace, federal agencies experience a normal amount of attrition, but the stakes are higher when direct hire employees leave the organization because of the authority’s constraints. Any authorization of the DHA in the future should consider how attrition will impact actual hires over the authorization period.

In order to bolster support for expanding the authority, DOE can take steps to share out successes of the program. The DHA has been a huge win for federal clean energy hiring, and publicizing news about related programs, offices, funding opportunities, and employees that would not exist but for the support of the Clean Energy Corps would help make the connection between flexible hiring and government effectiveness and would generate excitement about DOE’s activities in the general public.

DOE should highlight success stories of the Clean Energy Corps.

As part of a larger external communications strategy, DOE should highlight success stories of current employees hired through the Clean Energy Corps portal. These spotlights could focus on projects, partnerships, or funding opportunities that employees contributed to and put a face to the achievements of the Clean Energy Corps thus far. Not only would this encourage future high-quality applicants and ensure continued interest in the program, but would also advertise to Congress and the general public that the authority is successful and increase support for more flexible hiring authorities and clean energy funding.

There are also some opportunities to improve DOE’s use of the authority and make it even more effective. With so many applications, hiring managers and program offices are often overwhelmed by sheer volume – leading to long wait times for applicants. Some offices at DOE have tried to address this bottleneck by building informal processes to screen and refer candidates–using their internal system to identify qualified applicants and sharing those applications with other program offices. But there may be additional ways to reduce the backlog of applications.

DOE should conduct a review of DHA’s use thus far.

DOE should conduct an assessment of the use of the Direct Hire Authority in relevant offices. The program has been running for over a year, and there is enough data to review and better understand strengths and areas of growth of the authority. The review could be an opportunity to highlight and build on successful strategies like the informal process above–with program offices who currently use those strategies helping to scale them up. It could also assess attrition rates and compare them to agency-wide and non-DHA attrition rates to understand opportunities to improve or share out successes around retention. Finally, the review could also act as a resource for Congress to help justify the authority’s renewal in the future.

Use of IPA Agreements

One of the most well-known tour-of-service programs is the Intergovernmental Personnel Act. When used effectively, it can allow agencies to share cross-sector knowledge, increase their capacity, and achieve their missions more fully. As noted previously, DOE has made use of IPAs in some capacities, but barriers to expanding the program still exist. First, the DOE maintains a list of ‘IPA-certified’ organizations, including non-profits that must first certify their eligibility to participate in IPA agreements. According to OPM, if an organization has already been certified by an agency, this certification is permanent and may apply throughout the federal government. This is an effective practice that theoretically allows DOE to bring on IPAs from those organizations more quickly – without the additional administrative work necessary to research and vet each organization multiple times.

However, when FAS engaged DOE to expand the Impact Fellowship to the agency, FAS was asked to re-certify its eligibility separately with DOE despite already having conducted IPA agreements with other agencies. As of May 2021, DOE has only approved 22 organizations for IPA eligibility. With the clean energy ecosystem booming, this leaves a large amount of talent potential going untapped.

DOE should amend its IPA directive.

One solution to this issue would be for DOE to amend its IPA directive, which was last updated in 2000, to automatically approve IPA eligibility for organizations that have been certified by other agencies. Agencies such as NSF, USDA, GSA, and others also maintain lists of IPA-eligible organizations, providing DOE a readily available pool of potential IPA talent without certifying those organizations independently. This solution could expand the list of certified organizations and reduce DOE’s internal administrative burden. Organizations that know they will go through an initial vetting process once rather than multiple times could redouble efforts to build that partnership with DOE.

DOE should work with outside organizations to share strategies.

The previous recommendation on educating eligible non-federal organizations on tour-of-service mechanisms applies here as well. Organizations like FAS with a proven track record of setting up IPA agreements with agencies can share best practices, success stories, and champion the program in the broader non-profit ecosystem. However, agencies can also develop externally facing IPA resources, sharing training and ‘how-to’ guides with nonprofits and academic institutions that could be good fits for the program but aren’t aware of their eligibility or requirements to participate.

Recruitment

Recruitment is another area where we learned lessons from our work alongside DOE. FAS and Clean Energy for America held recruitment information sessions for people interested in working for DOE, spotlighting offices who needed more staff. One strategy that helped target specific skill gaps within the agency was developing ‘personas’ based on certain skill sets, like finance and manufacturing. These personas were short descriptions of a specific skill set for an industry, consisting of several highlighted experiences, skills, or certifications that are key to roles in that industry. This enabled our team to develop a more tailored recruitment event, conduct targeted outreach, and execute the event with a more invested group of attendees.

DOE should identify specific skills gaps to target recruitment efforts.

DOE hiring managers and program offices should identify skills gaps in their offices and recruit for those gaps using personas. Personas can help managers more intentionally target outreach and recruit in certain industries by allowing them to advertise to associations, academic programs, or on job boards that include potential applicants with those skills and experiences. This practice could bolster recruitment and reduce the time to hire by attracting more qualified candidates up front. It also helps offices take a more proactive approach to hiring–a difficult ask for hiring managers, who are often overworked.

DOE should continue to utilize remote flexibilities.

Another successful recruitment strategy highlighted in our work with DOE has been the use of remote flexible positions. DOE should continue to widely utilize remote flexibilities in job opportunities and recruitment in order to attract talent from all 50 states, not just those where DOE has a physical presence. As the desire for remote employment remains high across the public and private sector, fully utilizing the remote flexibilities can help federal employers stay competitive with the private sector and attract high-quality talent.

Another area of recruitment where DOE could capitalize further is with more partnerships with non-federal organizations. Outside organizations can leverage their networks–helping expand the talent pool, increase diversity, and support candidates through the federal hiring process, competitive or otherwise. Networks like New York Climate Tech have been tirelessly organizing the climate tech community in New York City, and even plan to start expanding to other cities soon. These types of organizing are invigorating for climate professionals; they can energize existing advocates and evangelize to new ones. Helping connect those networks to government opportunities–whether prize competitions, job opportunities, or grants–can strengthen cross-sector relationships and the clean energy workforce overall.

Such efforts would also support federal recruitment strategies, which are often not as visible as they could be given the sheer amount of work required for proactive outreach. Earth Partners, a climate tech venture capital firm, partnered with the Office of Clean Energy Deployment to hire for high-impact positions by leveraging its own network.

DOE should use partner organizations to broadcast hiring needs.

DOE Office of the Human Capital Officer, hiring managers, or program offices should consider how they can partner with other organizations to broadcast hiring needs. These can be larger clean energy associations and member organizations like Clean Energy for America, New York Climate Tech, FAS, and Climate Power, or they could be energy sector affinity groups like Women In Renewable Industries and Sustainable Energy (WRISE) and the American Association of Blacks in Energy (AABE). Coordinated social media campaigns, partnered recruitment events, or even sending out open positions in those organizations’ regular newsletters could help broaden DOE’s recruitment reach. Because of the momentum in the clean energy community, non-federal organizations have built out substantial recruitment infrastructure for potential applicants and can help publicize positions.

DOE should build a presence at campus hiring events.

Similarly, DOE hiring managers should build and maintain a presence at higher education hiring events. There are a number of ways to bring more early career staff into government, but DOE can focus on recruiting more intentionally from universities and community colleges. The agency should cultivate relationships with university networks–especially those of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Minority Serving Institutions (MSIs)–and develop recruitment messages that appeal to younger populations. DOE could also focus on universities with strong clean energy curricula–in the form of recognized courses and programs or student associations.

DOE should expand partnerships with external recruitment firms.

Some positions, of course, are harder to recruit for. In addition to mid-level employees, government also needs strong senior leaders–candidates for these positions don’t often come in droves to recruitment events. Some DOE offices have found success with using private recruitment firms to identify candidates from the private sector and invite them to apply for Senior Executive Service (SES) level positions in government. This practice, in addition to bringing in specific executive recruitment, also helps career private-sector applicants navigate the government hiring process.

DOE should learn from current strategies and continue to partner with private recruitment firms to identify potential SES candidates and invite them to apply. Using recruitment firms can help simplify position description language and help guide candidates through the process. DOE currently uses this successfully for certain skill set gaps, but should seek to expand the practice for recruitment needs that are more specific.

DOE should develop its own senior talent recruitment strategy.

Longer term, DOE should develop its own senior talent recruitment strategy. This strategy can be developed using lessons learned from private recruitment firms or from meeting with other agencies to understand best practices in the space. SES positions require different candidate management strategies, and if DOE aims to attract more non-federal talent, developing in-house expertise is important.

DOE already has the infrastructure for strategies like this. Offices involved in IIJA implementation are building office-specific recruitment strategies. These strategies consider diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility, as well as skill sets and high-need positions within offices. Incorporating senior talent needs into these strategies could help uncover best practices for attracting quality leaders, and expanding these recruitment strategies beyond just IIJA-oriented offices could support workforce development across the agency more broadly.

The Path Forward

DOE has made significant progress on the road to implementation, hiring hundreds of new employees to support the clean energy transition and carry out programs from IIJA, IRA, and the CHIPS and Science Act. The agency still faces challenges, but also opportunities to grow its workforce, improve its hiring processes, and bring in even more high-quality, skilled talent into the federal government. We hope DOE and Congress will consider these recommendations as they continue to work toward a stronger clean energy ecosystem in the years to come.

Appendix: Overview of hiring authorities

IPAs

The Intergovernmental Personnel Act (IPA) Mobility Program that allows temporary assignment of personnel between the federal government and state/local/tribal governments, colleges/universities, FFRDCs, and approved non-profit organizations. According to a 2022 Government Accountability Office report, IPAs are a high-impact mechanism for bringing talent into the federal government quickly, yet they’re often underutilized. As detailed in the report, agencies’(including DOE) can use the IPA Mobility Program to address agency skills gaps in highly technical or complex mission areas, provide talent with flexibility and opportunities for temporary commitments, and can be administratively light touch and cost effective, when the program is implemented correctly. The report noted that agencies struggled to use the program to its full effectiveness, and that there’s an opportunity for agencies to increase their use of the program, if they can tackle the challenges.

Direct Hire

The Direct Hire Authority allows agencies to directly hire candidates for critical needs or when a severe shortage of candidates exists. This authority circumvents competitive hiring and candidates preferences, allowing agencies to significantly reduce the time involved to hire candidates. It also presents an easier application process for candidates. DHA must be specially granted by OPM unless a governmentwide authority already exists–as it does for Information Technology Management, STEM, and Cybersecurity. For example, DOE was granted a DHA for positions related to implementing the IIJA and IRA.

Excepted Service

EJ and EK

EJ and EK hiring authorities are a form of “excepted service” unique to DOE. According to DOE, the EJ authority is used to enhance the Department’s recruitment and retention of highly qualified scientific, engineering, and professional and administrative personnel. Appointments and corresponding compensation determined under this authority can be made without regard to the civil service laws.” The EK authority is similar, but more specific to personnel whose duties will relate to safety at defense nuclear facilities of the Department. The EK authority is time-limited by law and must be renewed.

Schedule A(r)

Also known as the “fellowship authority,” Schedule A(r) facilitates term appointments for 1 to 4 years. This authority is especially helpful for:

- “Professional/industry exchange programs that provide for a cross-fertilization between the agency and the private sector to foster mutual understanding, an exchange of ideas, or to bring experienced practitioners to the agency.”

- “Positions established in support of fellowship and similar programs that are filled from limited applicant pools and operate under specific criteria developed by the employing agency and/or a non-federal organization.

Experts and Consultants

According to the department’s HR resources, DOE uses Experts and Consultants to, “provide professional or technical expertise that does not exist or is not readily available within DOE or to perform services that are not of a continuing nature and/or could not be performed by DOE employees in competitive or other permanent full-time positions.” Typically, Expert and Consultants can be used for intermittent, part-time, or term-limited, full-time roles.

Understanding and using these flexible hiring authorities can help DOE expand its network of talent and hire the people it needs for this current moment. More details on flexible hiring mechanisms can be found here.

How DOE can emerge from political upheaval achieve the real-world change needed to address the interlocking crises of energy affordability, U.S. competitiveness, and climate change.

As Congress begins the FY27 appropriations process this month, congress members should turn their eyes towards rebuilding DOE’s programs and strengthening U.S. energy innovation and reindustrialization.

Politically motivated award cancellations and the delayed distribution of obligated funds have broken the hard-earned trust of the private sector, state and local governments, and community organizations.

Over the course of 2025, the second Trump administration has overseen a major loss in staff at DOE, but these changes will not deliver the energy and innovation impacts that this administration, or any administration, wants.