Collaborative Action in Massachusetts to Counter Extreme Heat

Through partnership with the Doris Duke Foundation, FAS is building bridges between the environmental community and the health community around extreme heat. Informed by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council’s and Boston University’s symposium on heat-health action and partnerships in Massachusetts, FAS seeks to showcase how local and state governments are working across sectors to address extreme heat. With heat being a rising cause of illness and death, these case studies show how governments are engaging in policy entrepreneurship to protect lives through targeted data collection, research, and policy and program design. Lessons learned from these cases can inform how state and local governments can leverage their existing capabilities to reduce risk and improve health outcomes.

Promising examples of progress are emerging from the Boston metropolitan area that show the power of partnership between researchers, government officials, practitioners, and community-based organizations. These include efforts to (1) assess the risk that heat poses to populations, operations, and ways of life, (2) reduce the potential for harmful exposures, and (3) strengthen the public health response. The following cases draw from examples shared at “Fostering Collaborations: A Symposium to Advance Equitable Heat Health Actions”, hosted by Boston University and the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) in June of 2025, and show what historically cold places can do to adapt to extreme heat. These cases serve as a resource for documenting progress made across the region. The recommendations in this report are informed by the cases and build from the Metro Mayors Climate Taskforce’s “Keeping Metro Boston Cool: A Regional Heat Preparedness and Adaptation Plan” and upon leading practices identified in MAPC’s Climate Resilience Playbook (a guide of resilience actions for Massachusetts municipalities).

Case studies in this brief include:

- Targeting Assistance to the Most Heat-Impacted Homes and Buildings

- Data-Informed Land Use and Urban Planning Solutions to Cool Blocks and Communities

- Leveraging an Ecosystem of Health System Partnerships to Advance Extreme Heat Emergency Management

Many people traditionally associate extreme heat with “hot” places, like the Southwest, Texas, and the Southeast, and their record-breaking heat and humidity. While stark, these places are more likely to have the infrastructure (such as widespread adoption of cooling systems) and policies and practices (such as Chief Heat Officers, heat response plans, and protections like utility shutoff prevention and indoor cooling standards) needed to safeguard populations from excess heat exposure. While there is still a lot to do, many communities in the southern United States have already begun to adapt daily life and routines to extreme heat conditions.

The northern United States is at a frontier of grappling with extreme heat. Places with typically colder climates, like Massachusetts – state motto, “By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty”– are experiencing extreme heat. The populations here are neither acclimatized to extreme heat nor equipped with the necessary adaptations. This is putting significant pressure on people’s health and livelihoods, the built environment, and the local economy. For example, this summer, the City of Boston declared three heat emergencies, including a June heat wave that smashed previous early season records as temperatures soared to 102°F. In total, the Boston metropolitan area experienced 19 days over 90°F in 2025. By 2030, less than five years away, the area could experience nearly 40 days over 90°F.

Health Dangers of Extreme Heat

Extreme heat exposure causes heat-related illnesses such as heat stress and heat stroke and puts significant pressure on the cardiovascular system and the kidneys, and strains the health of populations with pre-existing conditions or on medications that impact sweat production. While extreme heat can impact everyone, certain populations face higher risks, including children, elderly adults, pregnant mothers, those without access to air conditioning, and outdoor workers. Heat related health impacts are on the rise in Boston.

Protecting human health from extreme heat requires a combination of approaches, including preventing exposure, minimizing risk, increasing adaptive capacity, and bolstering health system preparedness:

- To prevent exposure, decision makers need to consider the “settings” where populations spend the most time from day to day, like homes, schools, child and elder care facilities, workplaces, public transportation, and outdoor recreation spaces, and the institutions and policies that can determine the physical design and operations of these spaces.

- To minimize risk, populations that are more vulnerable need to be made aware of and protected by strategies that minimize heat gain, such as wearing optimal clothing and reducing behaviors that increase metabolic rate and generate heat.

- To increase adaptive capacity, populations will need to engage in strategies that help their bodies acclimatize to the hotter temperatures as well as recognizing symptoms of over-exposure and taking steps to seek protection or care.

- To bolster health system preparedness, public safety and health care institutions need to be readied and supported to act quickly and effectively to save lives.

Massachusetts’ Heat Policy Heats Up

Strong policies that support public health response to heat can reduce the risk of systemic failures and protect more lives. To succeed, these policy efforts require public-private partnerships, empowered public health responses, and strong community engagement.

There is a growing ‘community of practice’ on heat in Massachusetts, consisting of local and state government leaders, academic partners, non-profits, health care institutions, and private sector actors seeking to advance solutions to safeguard lives during heat emergencies and build towards a heat resilient future. Effective partnerships help understand the extreme heat problem, realize new heat-health interventions, develop the evidence around effectiveness, and foster shared accountability. At this critical juncture of changes to federal policy and governance on heat, effective state and local preparedness for extreme heat is critical to safeguard human health, prevent critical infrastructure damages, and secure economic livelihoods. These following cases show what’s possible.

Massachusetts’ Heat-Health Actions and Innovations

Innovation 1. Targeting Assistance to the Most Heat-Impacted Homes and Buildings

In Massachusetts, most residential buildings and many public buildings were designed for a climate with cold winters and temperate summers and were not built with air conditioning (AC) and other cooling systems. The cost and difficulty of retrofitting these buildings for increasingly hot summers is a significant barrier to being better prepared for heat. Many homeowners, renters, and public building operators rely on window AC units, which are both less effective and less efficient than central AC. This in turn increases the cost of operation and monthly energy bills.

For housing, the role of public policy is threefold: (1) establishing minimum habitability standards that affirm a right to cooling, such as indoor temperature maximums for rental housing, (2) maintaining access to energy during extreme heat events through utility shut off moratoriums and expanded energy bill assistance, and (3) streamlining available funds to systematically improve the housing stock to make it more adapted to rising temperatures. The Massachusetts state government can play their part in this ecosystem of protections by regulating utility companies to ensure consumer protections during extreme heat events, improving the floor of minimum habitability through the state sanitation code, bringing together state, federal, and private funding resources that can be used to retrofit the housing stock and develop new housing stock more resilient to extreme heat. Municipal governments’ can play their part by setting beyond code measures to ensure safe indoor temperatures, bringing together resources to serve households in need of housing upgrades, coordinating and empowering local partners to serve the most energy insecure populations and upgrading the public housing stock under their management. Given limited public resources, the most important first step is to prioritize where support should be directed.

Data gathering about risk and vulnerability can help communities get started. With investment from the state of Massachusetts’ Municipal Vulnerability Preparedness program, cities and towns in the Boston metropolitan area, like Everett, have been able to identify their community “hot spots”, where residents experience higher ambient temperatures as a result of urban design choices. This is a part of a broader trend in the Boston metro region to map heat vulnerability, such as the Wicked Hot Mystic Campaign and the Framingham-Natick-Ashland-Holliston Heat Watch Campaign. These higher ambient temperatures can also lead to overheating indoors, requiring more mechanical cooling to maintain habitable temperatures and also limiting the use of passive ventilation cooling at night as cities take longer to cool down.

With the hot spots identified, key anchor institutions like Cambridge Health Alliance and community organizations like Everett Community Growers are working together to meet the needs of the most vulnerable residents, which includes improving housing’s resilience to extreme heat. One-stop shops for residential weatherization, such as Philadelphia’s Built to Last program, can bring all sources of funding for home improvements under one roof with technical support, making it easier for low-income residents to access available resources. Further, as places like Everett seek to expand their housing supply, it is critical that new stock is built to withstand rising temperatures, mitigate urban heat island effects, and is affordable to current residents.

Boston University’s C-Heat Study is another example of a community-engaged temperature sampling study to understand the lived experiences of residents during extreme heat events. This study places sensors inside of people’s homes in Chelsea and East Boston to see how hot it gets indoors. Many of the homes sampled exceeded temperatures widely recognized as “comfortable” by international standards bodies like the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) in spite of 100% of households having some form of air conditioning. Factors that impacted household’s ability to cool include whether they could use their AC (e.g. due to cost), AC-type, location of the unit, and roof type. Through this critical participatory research, the research team and the community partners developed a set of policy recommendations to mitigate heat’s impacts indoors. These include updates to the state sanitary code or municipal ordinances that set indoor temperature maximums and require AC, weatherization, and other strategies in rental units to maintain safe indoor temperatures, as well as creating programs that encourage landlords to retrofit rental housing. Looking ahead, it will be essential to ensure that the energy needed to run these AC systems is affordable, especially as energy prices rise. The proposed legislation “Energy Affordability, Independence, and Innovation Bill” seeks to lower the cost of energy while also protecting people from utility shutoffs while “An Act Promoting Resilience Against the Heat-Related Impacts of Climate Change” seeks to create energy assistance programs for cooling-related costs.

Publicly-owned buildings and other infrastructure also need to be retrofitted to be more resilient to temperature extremes through cooling system upgrades and passive cooling designs. These strategies benefit populations that spend a significant amount of time in public buildings, such as school-aged children and their instructors. Understanding the scope and scale of the problem is also essential for these buildings. For example, researchers at Boston University (BU) are partnering with Boston Public Schools (BPS) to understand the conditions inside of classrooms. Dr. Patricia Fabian of BU and BPS have installed temperature sensors in over 3,600 rooms within school buildings and created a one-of-a-kind dataset of the state of heat inside of schools. Their results show that within a single school building, the difference between the coolest and hottest classrooms could be more than 26°F. Understanding which classrooms cannot stay cool on extreme heat days is critical for facilities managers and school leadership to be aware of and capable of responding to. It also helps to identify places to target cooling interventions, and justify infrastructure upgrades. The proposed Mass Ready Act would create sources of funding that could be used to finance these identified improvements.

Opportunity Areas for Further Action:

- Expand community-led and cross-sector partnerships to study indoor temperatures and its impacts on population health, wellbeing, and livelihoods.

- Secure near-term access and affordability to cooling by creating programs that provide financial assistance to households that struggle to pay their energy bills.

- Institutionalize cooling in building and housing policy by crafting and implementing building codes and public health regulations that formally integrate thermal safety.

- Retrofit infrastructure for climate resilience, targeting the most vulnerable buildings and homes first. One stop shops for housing upgrades are especially beneficial to reduce the application burden on the most vulnerable homeowners.

- Ensure new construction is built to keep occupants comfortable in the face of anticipated future extreme temperatures.

Innovation 2. Data-Informed Land Use and Urban Planning Solutions to Cool Blocks and Communities

Community-wide cooling solutions can lower ambient outdoor temperatures, reducing the load on indoor cooling systems and mitigating the health risks of being outside. Public policy is a critical enabling function. For example, zoning policy can be leveraged to require or encourage strategies that cool communities, such as urban forestry, shade infrastructure, cool pavements, walls, and roofs, and green roofs. Outdoor spaces under public ownership can be also outfitted with these heat-mitigation strategies, benefiting populations that use transit or primarily walk or bike as well as populations that spend significant amounts of time outdoors.

Municipal governments in Massachusetts have oversight over land use and zoning as well as own, manage and maintain some public outdoor spaces and right-of-ways. Thus, municipal governments can introduce zoning regulations to drive innovation in heat-resilient design through new construction or upgrades to existing construction. For example, the Massachusetts state government operate the public transportation system, either through the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority or 15 Regional Transportation Authorities, manages land and property, and reviews local zoning ordinances for consistency with state law. Thus, the state is responsible for ensuring transportation users have adequate protection from extreme heat exposure and can also be a partner to local governments implementing heat-resilient zoning. The state also is a source of funds, bringing in revenue and also distributing federal dollars. Data on the current impacts of heat can inform the work of land use and urban planners to design high-impact solutions that minimize future heat exposures while also educating the public on heat’s risks.

Governments in the Boston metropolitan area are developing innovative solutions to understanding urban heat. For example, the Boston Region Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), the transportation planning agency for the region, was awarded a $1 million dollar grant from the State of Massachusetts to assess heat’s risk to pedestrians and bikers. The “Neutralizing Onerous Heat Effects on Active Transportation” (NO-HEAT) study produced a new set of microclimate data focused on human-scale perception of heat and leveraged that alongside mobility data to identify high-volume routes in vulnerable communities with high risk of heat exposure. Following identification of priority corridors in partnership with Dr. Rounaq Basu of the Georgia Institute of Technology, the project leads from the MPO are now working with municipal staff and advocacy organizations to understand the impacts of this heat risk on people who are walking/biking and identifying solutions that minimize exposure. The project will also make its analysis of heat risk along walk/bike routes public on the Boston Region’s MPO’s website. In addition, an app will be piloted that can guide community members on how to choose transportation routes with more shade and greenery. Going forward, this work could be expanded to the impacts of heat on public transportation users and how to mitigate that risk, such as through shaded bus shelters and cooling inside T-stations.

Municipalities are also utilizing their existing resources and policy levers to drive urban transformation. In the City of Cambridge, planners are turning well-known heat islands in the city into gathering spaces with public art installations that reduce heat exposure. The Shade is Social Justice Program partners the City with local and regional artists, such as Massachusetts-based Art for Public Good, on installations around Cambridge that create shaded “third spaces” for public gathering and programming during hotter days. Through art and design, the City of Cambridge is facilitating both public education about extreme heat and its risks, reducing exposure, and creating forums to build community relationships that are key for community resilience. Beyond this work, the City of Cambridge is a leader in resilient land-use policy, creating one of the first performance-based standards for extreme heat mitigation. The “cool score” seeks to drive uptake of infrastructure solutions that mitigate urban heat island effects, and is required for all developments subject to the Green Factor Standard (e.g. new buildings, building enlargements of 50% or more, and surface parking area creation). These efforts underscore the importance of local government programs and policy in both providing and enabling shade and other cooling solutions that lower temperatures community-wide, ultimately benefiting businesses and residents who can stay cooler for less money.

Opportunity Areas for Further Action:

- Identify which stakeholders need to be at the table to create standardized heat vulnerability tools and how they guide decision-making. These tools can be used by city planners, public health departments, and community groups to prioritize high-risk areas and align investments.

- Understand all the actors inside of each government and at different levels of government who are creating plans to reduce the risk of extreme heat in the built environment (e.g. MPOs and city planning offices) and de-silo these efforts.

- Craft best practices for heat land use and urban planning policy, such as effective heat action and resilience plans, standardized zoning and land use codes, and design guidance for reducing the risk of heat to transportation system users.

- Continue working with the state and fellow Regional Planning Agencies to implement and align the priorities of ResilientMass with ongoing regional planning work

- Invest in both temporary (e.g. pop up shade structures) and long-term solutions (e.g. expanded tree canopy) that mitigate heat at the local level.

Innovation 3. Leveraging an Ecosystem of Health System Partnerships to Advance Extreme Heat Emergency Management

Across the nation, extreme heat is a public health emergency, causing increased rates of heat-related illness, emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. These impacts put strain on public safety systems and health care systems. Yet there is no widely agreed upon “playbook” for how to respond to public health emergencies caused by extreme weather events and no agreement on what resources should be made available. Federal law is unclear in its expectations of the roles of state and local governments in heat preparedness and response as well as the federal role in providing assistance. For example, it is unclear if a heat event would qualify for a Major Disaster Declaration under the Stafford Act and/or the Public Health Emergency Declaration under the Public Health Service Act. The costs to human health and wellbeing are not well-captured by the federal disaster declaration processes, which focus on acute and time-bound structural damage.

The state of Massachusetts has the authority to declare a state of emergency, enabling flexibility to leverage state agency capacity to respond to emerging hazards. There has never been an extreme heat event declared as a state of emergency in Massachusetts. The City of Boston is one of the only municipalities in Massachusetts to have created a local heat emergency pathway and declare heat emergencies. The threshold for declaring a local emergency in Boston is clear, two or more days with a heat index of 95 degrees, which is below the threshold used by the National Weather Service. During these events, the City of Boston opens cooling centers, splash pads, and public pools, as well as creates pathways for shelter for the unhoused. Response is led by the Office of Emergency Management, which relies on federal funding for its operations and staff, and could be impacted by proposed policy changes at the federal level to put the onus of emergency preparedness on state and local governments. Boston’s model is one to learn from, where understanding the successes and challenges can help determine how to replicate across Massachusetts’s municipalities. Effective emergency management relies on public-private partnerships and the health sector is one of the most critical partners in responding to extreme heat.

Safeguarding health during acute extreme heat events is a matter of preparedness. To be sufficiently prepared, residents should have access to basic information and support on how to effectively protect themselves from extreme heat, reducing their exposures, securing access to cool spaces, and ensuring adequate hydration. This needs to be done in languages that impacted populations speak, which has been done in cities like Los Angeles. More vulnerable residents should be supported in securing these protections by members of their community and by health care teams. For example, health care providers should screen patients for pre-existing conditions that make them more vulnerable to extreme heat, and be able to identify social services programs that can help them mitigate potential exposures, such as energy assistance. For example, the Boston Medical Center has created an innovative “Clean Power Prescription” program to provide energy assistance to the most vulnerable patients in their complex care management program. The Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Americares have also created a resource guide for physicians and clinics to prepare for extreme heat events, including a ‘Heat Action Plan’ that can be walked through with patients.

When a heat wave is predicted, it is critical to have early warning systems that allow people to activate their preparedness plans and brace themselves for the heat. The Bureau of Climate and Environmental Health at the Massachusetts Department of Public Health has created an unhealthy heat forecast which uses statewide hospitalization data to determine health-based “heat thresholds” for alerting the public and practitioners about upcoming heat events. The Bureau also sends tailored alerts to local public health officials, health care providers, and community-based organizations (this group must opt-in) to help them identify how to spot heat-related illness during the more extreme heat events, three or more days of 85°F. This communication is critical as these personnel are trusted messengers in their communities. Boston-area health systems are also taking action. Mass General Brigham is piloting artificial intelligence-powered tools that utilize patient records to identify those most at risk (e.g. because of age, health conditions, medications and where they live) and then provide patient-specific alerts based on that risk. Cambridge Health Alliance sends email alerts to patients during heat waves.

Finally, during a heat event, the emergency response workforce and the health care workforce needs to be prepared and able to triage and treat surges in heat-related and heat-exacerbated illnesses. Many health care providers are not trained on how to identify and effectively treat heat-related illness, which can hamper their effectiveness. That is why physician training programs like Harvard Medical School are integrating climate change into the curriculum for medical students and offering new fellowships to train climate-ready care providers. Yet these programs are only reaching a small portion of the health professions workforce each year. Scaling these types of programs is needed to ensure a wider swath of the health care workforce knows how to treat heat-illness and its broader impacts on human health, which will in turn improve data accuracy for heat-related health impacts. Additionally, health care systems are also not required to plan for heat and its impacts on care delivery and operations. There is also no regional coordination between systems to manage surges in care needs. Local governments and regional planning organizations like MAPC should be engaged with health care partners about their readiness for extreme heat.

Opportunity Areas for Further Action:

- Test and compare communication strategies (e.g. messages, channels, and messengers) to understand which strategies (e.g. heat alerts in clinical practice) are best at informing and encouraging action-oriented responses from the public.

- Develop screening questions for clinical settings to assess availability of air conditioning, social isolation, and other housing-related conditions as part of health screening.

- Determine what data is needed by municipalities to guide their response actions (e.g. the health impacts of extreme heat) and plan the acquisition of these data sets, like electronic health record data.

- Train local public safety, emergency medical services, health professionals, and other key partners in response to better capture the health impacts of extreme heat.

- Work regionally to develop a heat relief network, such as Maricopa County’s Heat Relief Network, to build connections and collaboration as well as resourcing and personnel sharing to ensure that the entire Boston Metropolitan area is ready for extreme heat.

Conclusion

Extreme heat governance is rapidly maturing to meet the needs of communities unaccustomed to extreme heat, particularly at the local and state levels. As described above, this work cannot be done alone: partnerships and collaborations are necessary to make even modest progress and most effective use of limited resources. Further, the above examples showcase how collaborative research in partnership with key stakeholders can be a powerful tool in guiding local and state government decision-making and informing the policymaking process. Through collective effort, real progress can be made to safeguard health in the face of extreme heat.

The opportunity areas identified by participants at Fostering Collaborations: A Symposium to Advance Equitable Heat Health Actions provide a roadmap for what can come next in local and state heat action in Massachusetts. Interested in getting involved? Please contact Kat Kobylt at KKobylt@mapc.org and head to our website here to learn more.

Protecting the Health of Americans in the Face of Extreme Weather

→ New Report: STAT Network highlights increasing threats, shows how states are rewriting playbooks in real time to protect American health, safety and economic vitality

→ First-ever survey reveals urgent need for coordinated action: only 5 percent of state health officials feel “very prepared”, 61 percent relied on federal funds now in flux.

PROVIDENCE, R.I. — November 3, 2025 — A new report from the STAT Network reveals that extreme weather events are jeopardizing the health, safety and economic prospects of Americans. Published today in partnership with the Federation of American Scientists and supported by The Rockefeller Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, the report reveals first-of-its-kind data from state public health officials in 45 states and territories on the urgent need for state-led coordination. The report also spotlights innovations that are being adopted and scaled through the STAT Network despite drastic cuts in federal funding to public health.

“States are navigating a new normal of extreme weather crises—heat waves following floods, wildfires overlapping with hurricanes—while the federal support and data tools they’ve relied on are eroding. No state should be left to shoulder this alone. Through our Extreme Weather & Health group and this report, we elevate what’s working on the ground as states are leading the response and offer a practical roadmap for acting at the speed and complexity of today’s hazards” said Stefanie Friedhoff, Professor of the Practice and STAT Network Lead, Brown University School of Public Health.

The STAT Network, which supports state public health officials across a range of pressing public health issues, started a dedicated extreme weather and health group in August 2024, serving as an essential connection point for collective problem solving in a shifting landscape. Of 136 state respondents who participated in the STAT Extreme Weather & Health survey shared with states in summer 2025:

→ only 5% feel “very prepared” to handle the escalating public health impacts of extreme weather

→ 61% prepared for extreme weather using federal funds that are now in flux

→ 39% cited federal partnerships as historically one of the most effective mechanisms to address impacts

→ 94% are concerned that socioeconomic disparities moderately (27%) or significantly (67%) contribute to unequal outcomes during extreme weather events in their state.

The new report, Protecting the Health of Americans in the Face of Extreme Weather: A Roadmap for Coordinated Action was developed to support these leaders at this moment of evolving challenges, needs and opportunities. The report details how states are pivoting their preparedness playbooks, showcases replicable new models, and identifies pressing gaps that funders, policymakers and thought leaders must still fill.

“Extreme weather events are no longer just natural disasters—they’re public health emergencies. From heat waves that overwhelm hospitals to floods that cut off access to care, Americans are feeling the strain in their communities. That’s why The Rockefeller Foundation launched the STAT Network at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic—to strengthen public health infrastructure through interstate collaboration and cross-sector partnerships. That same level of coordination is just as critical today as we face growing threats to health, safety, and economic opportunity” said Derek Kilmer, Senior Vice President for U.S. Program and Policy, The Rockefeller Foundation.

“One in three Americans report being personally affected by extreme weather in just the past two years – illustrating that extreme weather has become extremely common. The good news is that the negative health impacts of extreme weather are largely preventable. FAS is excited to partner with the STAT Network to help states step up as the federal government steps back, putting in place the innovative, evidence-based strategies we need to protect people and communities across the country,” said Dr. Hannah Safford Associate Director of Climate and Environment, Federation of American Scientists.

A changed landscape

Protecting the Health of Americans describes how extreme weather events have become more frequent, severe and widespread. From wildfires that quickly spiraled out of control in Maui and Los Angeles, to illness from extreme heat overloading emergency rooms across the Southwest, to sudden flash flooding from Hurricane Helene catching entire regions off-guard across Appalachia, it is clear that existing playbooks are no longer sufficient to respond to rapidly evolving threats. At the same time, cuts in 2025 at the Centers for Disease Control, the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Weather Service and other federal agencies have removed the backbone of funding, data and technical assistance many states relied on.

States lead the way

Summarizing ongoing preparedness and response efforts across states, Protecting the Health of Americans offers three pillars for action and shares concrete, replicable examples that emerge from the STAT Extreme Weather & Health Network:

Collaboration. States like Minnesota and California are embedding public health voices in climate and infrastructure decisions, while North Carolina and Texas have demonstrated that shared frameworks like FEMA’s Community Lifelines can unite health, energy and emergency systems under one coordinated response. Partnerships break down silos and accelerate action.

Data. In North Carolina, advanced modeling now informs heat alerts based on real-time health and climate data; Illinois is developing predictive tools that warn hospitals before storms hit; and Alaska’s Local Environment Observer Network turns community observations into early-warning intelligence. States are making data more interoperable, localized and actionable.

Communication. Massachusetts amplified risk messaging on Triple E and West Nile via medical providers, community groups and local media. California is co-developing an interactive curriculum with community health workers on responding to poor air quality events. Kansas convenes a cross-sector Extreme Weather Events Work Group with community-based organizations to co-create practical toolkits. States are modernizing their communications capacity, building trusted messenger networks and moving past an over-focus on social media outreach.

The new report also includes case examples from states such as Oregon, Arizona and Texas that illustrate how housing insecurity, energy burden, medical dependence on electricity, and lack of access to timely, trusted information add additional burden for low-income, elderly and rural populations—and how systems-level interventions focused on energy resilience, targeted mitigation and partnerships with community-based organizations can save lives.

Insights from this report can serve as a pathway to building community resilience and protecting health from the impacts of extreme weather. Looking ahead, the STAT Network, the Federation of American Scientists and other collaborators look forward to working with state leaders and their partners to translate this roadmap into sustained progress.

The announcement comes ahead of the STAT Network’s participation in The Rockefeller Foundation and Heartland Forward’s “Big Bets for America” convening in Oklahoma City, where leaders across the public, private, and non-profit sectors will discuss opportunities to help communities flourish.

To learn more, download the full report.

Media Contact:

STAT Network:

Caroline Hoffman

Assistant Director of Content and Strategy

STAT Network at Brown University

caroline_hoffman2@brown.edu

FAS:

Katie McCaskey

Communications Manager, Media and PR

Federation of American Scientists

(202) 933-8857

kmccaskey@fas.org

About the STAT Network

At a time of unprecedented disruption in the U.S. public health system, the STAT Network serves as a strategic, nonpartisan, practice-focused partner to the state public health workforce in all 50 states as well as three territories. Originally created as the State and Territory Alliance for Testing by the Rockefeller Foundation in 2020 to meet the urgent need for more state-to-state collaboration during the COVID-19 pandemic, the network convenes state health leaders across the country on a weekly basis to problem-solve ongoing threats, share best practices, and support one another. Learn more about STAT at https://sites.brown.edu/stat/

About the STAT Extreme Weather & Health sub-network and this report

The STAT Extreme Weather and Health Group was created in August 2024 and meets monthly. Over 480 state officials from public health, preparedness and related departments in 45 states and some countries have attended these sessions over the past year. Between May and July 2025, the Network also fielded a comprehensive Extreme Weather and Health survey, which yielded 136 responses (78% from state officials, 10% from local health officials, and 12% from federal, academic and other partners to state teams). Responses came from 34 states, with near equal participation across the political spectrum. The STAT team also met individually with state- and county-level teams in more than 25 states for in-depth conversations about ongoing response needs and innovations. Protecting the Health of Americans summarizes findings across overall network presentations and discussions, the dedicated state-level survey, and state-level interviews.

About FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver transformative impact, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to bring scientific rigor and analysis to address urgent challenges. More information about our work at the intersection of climate change and health can be found at fas.org/initiative/climate-health.

Summer, Wrapped: The 2025 “State of the Heat”

Earlier this year, FAS sounded the alarm that federal reductions in force, funding pauses and freezes, program elimination, and other actions were stalling or setting back national preparedness for extreme heat – just as summer was kicking into gear. The areas we focused on included:

- Leadership and governance infrastructure

- Key personnel and their expertise

- Data, forecasts, and information availability

- Funding sources and programs for preparedness, risk mitigation and resilience

- Progress towards heat policy goals

With summer 2025 in the rearview mirror, we’re taking a look back to see how federal actions impacted heat preparedness and response on the ground, what’s still changing, and what the road ahead looks like for heat resilience. Consider this your 2025 State of the Heat.

2025 State of the Heat

The State of Summer: How Hot Was It and How Did Communities Cope?

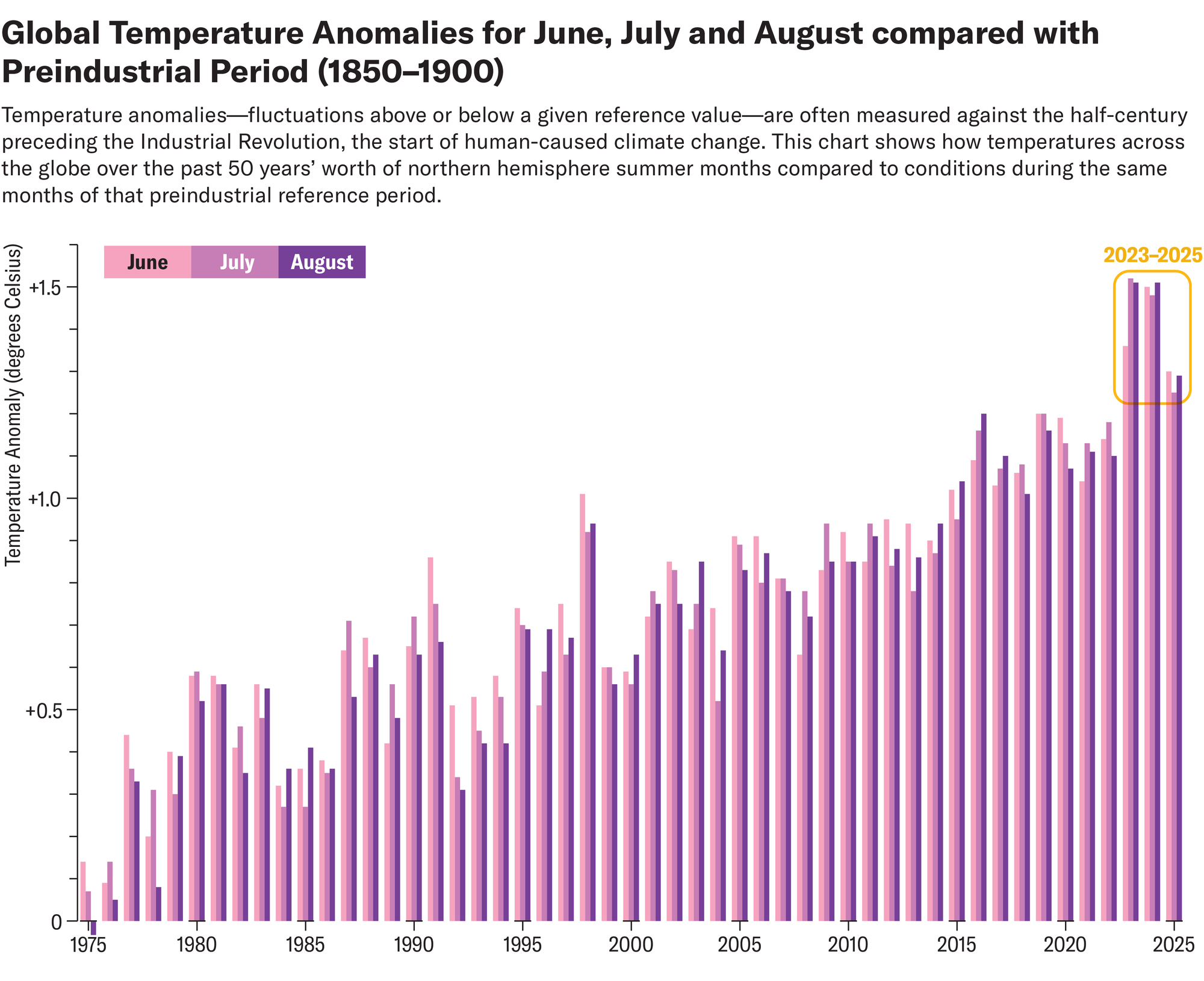

Summer didn’t feel as sweltering this year as it has the past couple of years. That’s objectively true – but only because the summers of 2023 and 2024 were true scorchers.

Summer 2025 was cooler than the past two summers, but still the third-hottest on record. Credit: Amanda Montañez in Scientific American; Source: Copernicus Climate Change Service (data)

Summer 2025 was still the third-hottest on record. High temperature records were shattered across the country. Eight states broke their all-time heat records for June, and in July almost the entire country – including Alaska – saw above-average temperatures. Temperature extremes continued into September. Places like the San Francisco Bay Area experienced their hottest temperatures of the year even as the season turned to autumn. In addition, humidity was a particularly potent threat. One hundred twenty million people experienced near-record humidity this summer alongside temperature extremes. Humidity and heat are a deadly combination because sweating is less effective when humidity is high, raising the risk of overheating and experiencing heat-related illness. This heat led to spikes in heat-related illnesses and hospitalizations, longer droughts, road buckling and damage, and even a federal energy emergency in June 2025.

Since January 2025, and continuing over the course of the summer, FAS’s Climate and Health team has been in regular touch with local and state government officials involved in heat preparedness, response, and resilience. These officials generally shared that heat management activities continued successfully in most places throughout the summer despite disruptions to federal funding and programs. Officials emphasized three specific developments that helped enable that continuity:

- Tools like the National Weather Service’s HeatRisk tool remained functional. HeatRisk is a critical tool for subnational governments to understand risks, inform and coordinate partners, and design thresholds for emergency response alerts and actions. Further, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Heat and Health Tracker, which monitors heat-related visits in emergency departments across the country, was brought back online following reversals in CDC reductions in force.

- Some key sources of federal funds, like American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding, remained available. Many local governments – particularly in places without large emergency management programs and Hazard Mitigation Assistance Program (HMGP) funds – have used ARPA funding to support heat response.

- Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) funding was released after considerable advocacy from the external community and members of Congress. This funding is critical to support home energy assistance for cooling bills.

Yet this continuity is fragile:

- The future of the National Integrated Heat Health Information System (NIHHIS) and the CDC’s Climate and Health program remains uncertain and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and CDC have faced notable staffing cuts and could face more cuts, jeopardizing the maintenance and existence of tools like HeatRisk and the Heat and Health Tracker.

- Officials are also concerned about their ability to keep robust heat response programs going in a more austere funding landscape. For example, ARPA funding must be spent by December 31, 2026, and many officials are expecting a steep funding cliff that could lead to cuts to heat-related programs. We are already seeing evidence of this in Miami-Dade County, which eliminated its Chief Heat Officer position as a part of an effort to close a $400 million funding gap that emerged in part as ARPA funds were exhausted. Additional cuts to, and restrictions on, federal health preparedness programs and emergency management programs will also impact the staffing capacity of state and local governments. For example, one of the state officials FAS was working with on heat lost their job because of state budget shortfalls, and others have worried about their future job security.

- Finally, while the LIHEAP program is currently intact, and has bipartisan support in Congress, it could be undermined by Executive Branch pocket rescissions and reductions in force.

The State of Federal Heat Governance: What Changed?

The federal heat landscape continues to be highly dynamic. While extreme heat is no longer a stated priority of the federal government, both this Administration and Congress have acknowledged heat’s risks. Against this backdrop, federal agencies are advancing a mixed bag of heat-related policies. For example:

- The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) continues to pursue a heat rule. This rule, which was initiated under the Biden Administration and is a top priority for worker advocates, was included on the Trump Administration’s Unified Agenda as a regulation in development. However, given comments made at summer hearings on this rule, recent reporting has hypothesized that OSHA may model the rule after Nevada’s newer and weaker “performance-based” standards. This rule includes no “trigger temperatures” above which certain protections are required. An evaluation of the Nevada rule’s effectiveness will be limited by cuts to the staff at the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), and less funding for NIOSH’s research.

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) recommits to research on extreme heat and health. The NIH’s Climate Change and Health (CCH) Initiative was reintroduced as the Program on Health and Extreme Weather (HEW). The HEW Program’s strategic framework eliminates language directly referencing climate change and greenhouse gases and aligns with the Department of Health and Human Services’ broader MAHA strategy. As both houses of Congress rejected cuts to the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), there could be funding available through NIEHS for studies on the outcomes of heat exposure, long-term health risks, and preventative measures.

- The Government Accountability Office (GAO) says the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) needs to evaluate its role in addressing extreme heat. A recent GAO report recommended that FEMA improve its benefit-cost analysis for heat, identify heat mitigation projects it might fund, and evaluate its role in heat response – all recommendations from FAS’s 2025 Heat Policy Agenda. FEMA agreed to act partially on the recommendations, citing changes made to HMGP to make extreme heat projects ineligible for standalone funding as a barrier to full action.

- The Department of Energy acknowledges heatwaves as a particular risk. In July, the Department of Energy published a report entitled A Critical Review of the Science of Climate Change. This report has been widely discredited for cherry-picking and misrepresenting scientific studies. However, it is notable that even as the report minimizes the risks of greenhouse gas emissions, it emphasizes the importance of taking action on extreme heat, stating that “heatwaves have important effects on society that must be addressed” and that “inability to afford energy leaves low-income households exposed to weather extremes”. While there are partisan disagreements on how to secure that affordable energy, the report demonstrates that heat risk is an area of consensus between the parties that merits further pursuit.

- The ongoing government shutdown could be used by the Trump Administration to continue their mass firing of federal workers. With the status of Appropriations negotiations stalled, the Office of Management and Budget has asked agencies to prepare contingency plans, and has threatened mass layoffs of furloughed employees. Given that most heat-related activities are not statutorily authorized, this could lead to further cuts to the federal heat workforce. On Friday October 10th, hundreds of workers were laid off across Health and Human Services, including at the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics and the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response.

Congressional actions are also shaping what’s possible for nationwide heat preparedness. To start, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) cut funding necessary to mitigate extreme heat’s impacts as well as respond to the negative health consequences of heat. Impacts include:

Beyond OBBBA, Congressional appropriations proposals for Fiscal Year (FY) 2026 represent a mixed bag for federal heat policy. The House and the Senate proposals diverge in key ways, and will need to be rectified. Some of the things we are tracking include:

State of the Future: What Comes Next for Heat Policy

Looking ahead, it is essential that the federal government maintains its role as a data collector, steward, and analyst, supports heat-related research and development, supports social services for the most vulnerable American households facing extreme heat. and continues to make investments in state, local, territorial, and tribal (SLTT) governments and their heat mitigation infrastructure and preparedness capacity. At the same time, SLTT governments are rapidly innovating in heat policy, and will be sites of innovation to watch this next year. Our team is tracking promising signs in three key areas:

- More places are standing up heat governance infrastructure. A growing number of state, regional, and local plans acknowledge extreme heat as a risk; at the same time, more and more communities are developing standalone heat preparedness, response, or action plans (see heatplans.org to learn more, and read our “Framework for a Heat Ready Nation” to learn about progress in the Sunbelt region). New heat plans that launched in 2025 include Lincoln-Lancaster Heat Response Plan, the Low Country Heat Action Plan Toolkit, Orange County, NC’s Heat Action Plan, and King County’s Extreme Heat Mitigation Strategy. Many more plans are in the development pipeline. Further, more networks of local governments, including the Ten Across Network and Climate Mayors, are making heat technical assistance a priority.

- More places are expanding their extreme heat protections. Policies that protect people from extreme heat exposure inside of their homes, inside of schools, and at the workplace are also starting to see uptake. LA County set an indoor temperature maximum of 82°F for rental units, creating a legal right to cooling for tenants. Meanwhile, the state of California recently enacted a law that all homes should be able to attain and maintain safe indoor temperatures, without specifying that limit. New Jersey now restricts utilities from shutting off the power due to non-payment from June 15 through August 31; New Jersey is also providing direct utility relief to New Jersey ratepayers. New York State became the first state in the country to regulate extreme heat in schools, setting a maximum temperature threshold of 88F for safe school operations. Finally, in Boston and in New Orleans, ordinances passed that require basic protections from heat, like rest breaks, for all city workers and city contractors. Scaling up these policies that minimize heat overexposure will be critical to be ready for hotter heat seasons to come.

- Regional networks are forming to advance evidence-based public health measures. In light of rollbacks to public health infrastructure at the federal level, two regional networks have formed to coordinate across state public health departments, the West Coast Health Alliance and the Northeast Public Health Collaborative. While the initial focus is on developing evidence-based recommendations on vaccines and combining forces on vaccine procurement for their populations, we will be tracking how these networks address other public health efforts under threat, such as the health risks of extreme heat.

Protecting Americans from extreme heat will require a multiplicity of leadership across the levels of government in the United States and the capacity to connect hundreds of diverse organizations and experts around a shared solution set. To meet this moment, FAS will develop the 2026 State & Local Heat Policy Agenda, a blueprint for polycentric action towards a Heat Ready Nation. The 2026 Heat Policy Agenda will align the growing heat community around a shared set of objectives and equip state and local decision makers with the strategies they can deploy for heat season 2026 and beyond. We are focused on strategies that (1) build government capacity to address the threat of extreme heat and (2) ensure every American can be safe from heat in their homes, in their workplaces, and in their communities.

Over the next couple of months, the FAS team will be documenting the policy levers available at the state and local levels to address extreme heat and crafting model guidance, model executive orders, model legislation, and financing models. Want to be a part of this effort? Reach out to Grace Wickerson at gwickerson@fas.org if you want to contribute by:

- Identifying promising extreme heat policies as well as evidence for their effectiveness.

- Offering your expertise on potential heat-related policy interventions.

- Sharing about heat-related advocacy efforts and potential technical assistance needs.

- Raising your hand as an extreme heat champion inside of state or local government.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Children’s Health and Future Success

Extreme heat poses serious and growing risks to children’s health, safety, and education. Yet, schools and childcare facilities are unprepared to handle rising temperatures. To protect the health and well-being of American children, Congress should (1) set policies that guide childcare facilities and schools in preparing for and responding to extreme heat, (2) collect the data required to inform extreme heat readiness and adaptation, and (3) strategically invest in necessary infrastructure upgrades to build heat resilience.

Children are Uniquely Vulnerable to Extreme Heat Exposure and Acute and Chronic Health Impacts

At least five factors drive children’s vulnerability to negative health outcomes from extreme heat, like heat-related illnesses and chronic complications. First, children’s bodies take a longer time to increase sweat production and acclimatize to higher temperatures. Second, young children are more prone to dehydration than adults because a larger percentage of their body weight is water. Third, infants and young children have challenges regulating their body temperatures and often do not recognize when they should act to cool down. Fourth, compared with adults, children spend more time active outdoors, which results in increased exposure to high ambient heat. Fifth, children usually depend on others to provide them with water and protect them from unsafe outdoor environments, but children’s caretakers often underestimate the seriousness of the symptoms of heat stress. Research shows that extreme heat days are linked to increased emergency room (ER) visits for children, especially the 16% of children living at or below the federal poverty line. Extreme heat also exacerbates children’s chronic diseases, like asthma and eczema, increasing health care costs and decreasing children’s overall quality of life.

The Consequences of Chronic Extreme Heat Exposure on Children’s Learning and Well-Being

Studies show that excess temperatures reduce cognitive functioning. Hot weather also impacts children’s behavior, making them more prone to restlessness, irritability, aggression, and mental distress. Finally, nighttime extreme heat exposure can disrupt sleep patterns, making it harder to fall asleep and stay asleep. These factors can all reduce children’s ability to focus, learn and succeed in school. For each 1°F rise in average annual temperature in school districts without air conditioning or proper heat protections, there is a 1% drop in learning. The Environmental Protection Agency found that these learning losses could translate into nearly $7 billion dollars in annual future income losses if warming trends continue.

Extreme Heat’s Threat to Schools and Childcare Facilities

Rising temperatures force school districts and childcare facilities into a dilemma: choosing between staying open in unsafe heat or closing and disrupting learning and care.

Staying open can expose students and young children to extreme indoor and outdoor temperatures. The Government Accountability Office found that 41% of U.S. schools need to upgrade their heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems: upgrades that will cost billions of dollars that schools in low-income areas do not have. Similar infrastructure challenges extend to childcare facilities. Extreme heat also makes outdoor recess more dangerous, as unshaded playgrounds and asphalt surfaces can heat up far above ambient temperatures and pose burn risks.

Yet when schools close for heat, children still suffer. Even five days of closures for inclement weather in a school year can cause measurable learning loss. Additionally, students may lose access to school meals; while food service continuation plans exist, overheated facilities can complicate implementation. Many children, especially in low-income families, also don’t have access to reliable cooling at home, meaning that when schools close for heat, these children receive little respite. Finally, parents are directly impacted as well: school closures also mean parents lose access to childcare, forcing many to miss work or pay for alternative arrangements, straining vulnerable households.

Advancing Solutions that Safeguard American Children from the Impacts of Extreme Heat

To support the capacity of child-serving facilities to adapt to extreme heat, Congress should direct the Department of Education to develop extreme heat guidance, technical assistance programs, and temperature standards, following existing state-level policies as a model for action. Congress should also direct the Administration for Children and Families to develop analogous policies for early childhood facilities and daycare centers receiving federal funding. Finally, Congress should direct the U.S. Department of Agriculture to develop a waiver process for continuing school food service when extreme heat disrupts schedules during the school year.

To support improved federal data collection efforts on extreme heat’s impacts, Congress should direct the Department of Education and Administration for Children and Families to collect data on how schools and childcare facilities are experiencing and responding to extreme heat. There should be a particular focus on the infrastructure upgrades that these facilities need to make to be more prepared for extreme temperatures — especially in low-income and rural communities.Lastly, to foster much-needed infrastructure improvements in schools and childcare facilities, Congress should consider amending Title I of the Elementary & Secondary Education Act or directing the Department of Education to clarify that funds for Title I schools may be used for school infrastructure upgrades needed to avoid learning losses. These upgrades can include the replacement of HVAC systems or installation of cool roofs, walls, and pavement, solar and other shade canopies, and green roofs, trees, and other green infrastructure, which can keep school buildings at safe temperatures during heat waves. Congress should also direct the Administration for Children and Families to identify funding resources that can be used to upgrade federally-supported childcare facilities.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Federal Healthcare Spending

Public health insurance programs, especially Medicaid, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), are more likely to cover populations at increased risk from extreme heat, including low-income individuals, people with chronic illnesses, older adults, disabled adults, and children. When temperatures rise to extremes, these populations are more likely to need care for their heat-related or heat-exacerbated illnesses. Congress must prioritize addressing the heat-related financial impacts onthese programs. To boost the resilience of these programs to extreme heat, Congress should incentivize prevention by enabling states to facilitate health-related social needs (HRSN) pilots that can reduce heat-related illnesses, continue to support screenings for the social drivers of health, and implement preparedness and resilience requirements into the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) and Conditions for Coverage (CfCs) of relevant programs.

Extreme Heat Increases Fiscal Impacts on Public Insurance Programs

Healthcare costs are a function of utilization, which has been rapidly rising since 2010. Extreme heat is driving up utilization as more Americans seek medical care for heat-related illnesses. Extreme heat events are estimated to be annually responsible for nearly 235,000 emergency department visits and more than 56,000 hospital admissions, adding approximately $1 billion to national healthcare costs.

Heat-driven increases in healthcare utilization are especially notable for public insurance programs. One recent study found that there is a 10% increase in heat-related emergency department visits and a 7% increase in hospitalizations during heat wave days for low-income populations eligible for both Medicaid and Medicare. Further demonstrating the relationship between increased spending and extreme heat, the Congressional Budget Office found that for every 100,000 Medicare beneficiaries, extreme temperatures cause an additional 156 emergency department visits and $388,000 in spending per day on average. These higher utilization rates also drive increases in Medicaid transfer payments from the federal government to help states cover rising costs. For every 10 additional days of extreme heat above 90°F, annual Medicaid transfer payments increase by nearly 1%, equivalent to an $11.78 increase per capita.

Additionally, Medicaid funds services for over 60% of nursing home residents. Yet Medicaid reimbursement rates often fail to cover the actual cost of care, leaving many facilities operating at a financial loss. This can make it difficult for both short-term and long-term care facilities to invest in and maintain the cooling infrastructure necessary to comply with existing requirements to maintain safe indoor temperatures. Further, many short-term and long-term care facilities do not have the emergency power back-ups that can keep the air conditioning on during extreme weather events and power outages, nor do they have emergency plans for occupant evacuation in case of dangerous indoor temperatures. This can and does subject residents to deadly indoor temperatures that can worsen their overall health outcomes.

The Impacts of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (H.R. 1) will have consequential impacts on federally-supported health insurance programs. The Congressional Budget Office projects that an estimated 10 million people could lose their healthcare coverage by 2034. Researchers have estimated that a loss of coverage could result in 50,000 preventable deaths. Further, health care facilities and hospitals will likely see funding losses as a result of Medicaid funding reductions. This will be especially burdensome to low-resourced hospitals, such as those serving rural areas, and result in reductions in available offerings for patients and even closure of facilities. States will need support navigating this new funding landscape while also identifying cost-effective measures and strategies to address the health-related impacts of extreme heat.

Advancing Solutions that Safeguard America’s Health from Extreme Heat

To address these impacts in this additionally challenged context, there are common-sense strategies to help people avoid extreme heat exposure. For example, access to safely cool indoor environments is one of the best preventative strategies for heat-related illness. In particular, Congress should create a demonstration pilot that provides eligible Medicare beneficiaries with cooling assistance and direct CMS to encourage Section 1115 demonstration waivers for HRSN related to extreme heat. Section 1115 waivers have enabled states to finance pilots for life-saving cooling devices and air filter distributions. These HRSN financing pilots have helped several states to work around the challenges of U.S. underinvestment in health and social services by providing a flexible vehicle to test methods of delivering and paying for healthcare services in Medicaid and CHIP. As Congress members explore these policies, they should consider the impact of H.R. 1’s new requirements for 1115 waiver’s proof of cost-neutrality.

To further support these efforts for heat interventions, Congress should direct CMS to continue Social Drivers of Health (SDOH) screenings as a part of Quality Reporting Programs and integrate questions about extreme heat exposure risks into the screening process. These screenings are critical for identifying the most vulnerable patients and directing them to the preventative services they need. This information will also be critical for identifying facilities that are treating high proportions of heat-vulnerable patients, which could then be sites for testing interventions like energy and housing assistance.

Congress should also direct the CMS to integrate heat preparedness and resilience requirements and metrics into the Conditions of Participation (CoPs) and Conditions for Coverage (CfCs), such as through the Emergency Preparedness Rule. This could include assessing the cooling capacity of a health care facility under extreme heat conditions, back-up power that is sufficient to maintain safe indoor temperatures, and policies for resident evacuation in the event of high indoor temperatures. For safety net facilities, such as rural hospitals and federally qualified health centers, Congress should consider allocating resources for technical assistance to assess these risks and the infrastructure upgrades.

Impacts of Extreme Heat on Agriculture

Agriculture, food, and related industries produce nearly 90% of the food consumed in the United States and contribute approximately $1.54 trillion to the national GDP. Given the agricultural sector’s importance to the national economy, food security, and public health, Congress must pay attention to the impacts of extreme heat. To boost the resilience of this sector, Congress should design strategic insurance solutions, enhance research and data, and protect farmworkers through on-farm adaptation measures.

Extreme Heat Reduces Farm Productivity and Profitability

Extreme heat threatens agricultural productivity by increasing crop damage, causing livestock illness and mortality, and worsening water scarcity. Hotter conditions can damage crops through crop sunburn and heat stress, reducing annual yields for farms by as much as 40%. Animals raised for meat, milk, and eggs also experience increased risks of heat stress and heat-related mortality. For dairy production in particular, an estimated 1% of total annual yield is lost to heat stress alone. Further straining agricultural productivity, extreme heat accelerates water scarcity by increasing water evaporation rates. These higher evaporation rates force farmers to use even more water, drawing often from already stressed water sources. The compounding pressures posed by extreme heat can translate into significant economic losses: a study of Kansas commodity farms found that for every 1°C (1.8°F) increase in temperature, net farm incomes drop by 66%. Together, this means reduced revenue for farms and less food available for people.

Insurance solutions can help mitigate these financial impacts from extreme heat if employed responsibly. Multiple permanently authorized federal programs provide insurance or direct payments to help producers recover losses from extreme heat, including the Federal Crop Insurance Program, the Noninsured Crop Disaster Assistance Program, the Livestock Indemnity Program, and the Emergency Assistance for Livestock, Honey Bees, and Farm-Raised Fish Program. These programs need to ensure that producers are adequately covered against heat-related impacts and incentivize practices that reduce the risk of extreme heat related damages. This in turn will reduce the fiscal exposure of federal farm risk management programs. Congress should call on the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) to research the feasibility of incentivizing heat resilience through federal crop insurance rates. Congress should also consider insurance premium subsidies for producers who adopt practices that enhance heat resilience for crops and livestock.

Given the increasing stress of extreme heat on the water systems necessary to sustain agricultural production, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) should build on its Weather, Water, and Climate Strategy and collaborate with USDA on a national water security strategy that accounts for current and future hotter temperatures. To enhance system-wide drought resilience, Congress can also appropriate funds to leverage existing USDA programs to support on-farm adoption of shade systems, effective water management, cover crops, and soil regeneration practices.

Finally, there are still notable knowledge gaps around extreme heat and its impacts on agriculture. These gaps include the long-term effects of higher temperatures on yields, farm input costs, and federal program spending. To address these information gaps and guide future research, Congress can direct the USDA Secretary to submit a report to Congress on the impacts of extreme heat on agriculture, farm input costs and losses, consumer prices, and the federal government’s spending (e.g., federal insurance and direct payment programs for losses of agricultural products and the provision of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits).

Extreme Heat Lowers Agricultural Workers’ Productivity and Exposes Them to Health Risks

Higher temperatures and resulting heat stress are endangering farmer and farmworker safety and reducing their overall productivity, impacting bottom lines. Farmworkers are essential to the American food system, yet they are among the most vulnerable to extreme heat, facing a 35 times greater risk of dying from heat-related illnesses than workers in other sectors. This risk is intensifying as the sector increasingly relies on H‑2A farmworkers, who are hired to fill persistent domestic farm labor shortages. In many regions, over 25% of certified H‑2A farmworkers are required to work when local average temperatures exceed 90°F, and counties with the highest concentrations of H‑2A workers often coincide with the hottest parts of the country. After the work day, many of these workers return to substandard employer-provided housing that lacks essential cooling or ventilation, preventing effective recovery from daily heat exposure and exacerbating heat-related health risks. On top of the health risks, these conditions make people less effective on the job, which translates to economy-wide impacts: heat-related labor productivity losses across the U.S. economy currently exceeds $100 billion annually.

To address these risks, Congress should pass legislation requiring the Occupational Safety and Health Administration to finalize a federal heat standard that provides sufficient coverage for farming operations. In tandem with Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) finalizing the standard, USDA should be funded to provide technical assistance to agricultural employers for tailoring heat illness prevention plans and implementing cost-effective interventions that improve working conditions while maintaining productivity. This should include support for agricultural employers to integrate heat awareness into workforce training, resources for safety equipment and education, and support for the addition of shade structures. Doing so would ensure that agricultural workers across both large and small-scale farming operations have access to essential protections, like shade, clean water, and breaks, as well as sufficient capacity to comply. Current funding streams that could have an extreme heat infrastructure “plus-up” include the Environmental Quality Incentives Program and the Farm Service Agency’s microloans program.Lastly, Congress should also direct OSHA to continue implementing its National Emphasis Program on Heat, which enforces employers’ obligation to protect workers against heat illness or injury. OSHA should additionally review employers’ practices to ensure that H2A and other agricultural workers are protected from job or wage loss when extreme heat renders working conditions unsafe.

Turning the Heat Up On Disaster Policy: Involving HUD to Protect the Public

This memo addresses HUD’s learning agenda question, “How do the impacts, costs, and resulting needs of slow-onset disasters compare with those of declared disasters, and what are implications for slow-onset disaster declarations, recovery aid programs, and HUD allocation formulas?” We examine this using heat events as our slow-onset disaster, and hurricanes as declared disaster.

Heat disasters, a classic “slow-onset disaster”, result in significant damages, which can exceed damage caused by more commonly declared disasters like hurricanes due to high loss of life from heat. The Federal Housing and Urban Development agency (HUD) can play an important role in heat disasters because most heat-related deaths occur in the home or among those without homes; therefore, the housing sector is a primary lever for public health and safety during extreme heat events. To enhance HUD’s ability to protect the public from extreme heat, we suggest enhancing interagency data collection/sharing to facilitate the federal disaster declarations needed for HUD engagement, working heat mitigation into HUD’s programs, and modifying allocation formulas, especially if a heat disaster is declared.

Challenge and Opportunity

Slow-Onset Disasters Never Declared As Disasters

Slow-onset disasters are defined as events that gradually develop over extended periods of time. Examples of slow-onset events like drought and extreme heat can evolve over weeks, months, or even years. By contrast, sudden-onset disasters like hurricanes, occur within a short and defined timeframe. This classification is used by international bodies such as the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).

HUD’s main disaster programs typically require a federal disaster declaration , making HUD action reliant on action by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) under the Stafford Act. However, to our knowledge, no slow-onset disaster has ever received a federal disaster declaration, and this category is not specifically addressed through federal policy.

We focus on heat disasters, a classic slow-onset disaster that has received a lot of attention recently. No heat event has been declared a federal disaster, despite several requests. Notable examples include the 1980 Missouri heat and drought events, the 1995 Chicago heat wave, which caused an estimated 700 direct fatalities, as well as the 2022 California heat dome and concurrent wildfires. For each request, FEMA determined that the events lacked sufficient “severity and magnitude” to qualify for federal assistance. FEMA holds a precedent that declared disasters need to have a discrete and time-bound nature, rather than a prolonged or seasonal atmospheric condition.

“How do the impacts, costs, and resulting needs of slow-onset disasters compare with those of declared disasters?”

Heat causes impacts in the same categories as traditional disasters, including mortality, agriculture, and infrastructure, but the impacts can be harder to measure due to the slow-onset nature. For example, heat-related illness and mortality as recorded in medical records are widely known to be significant underestimates of the true health impacts. The same is likely true across categories.

Sample Impacts

We analyze impacts within categories commonly considered by federal agencies–human mortality, agricultural impacts, infrastructure impacts, and costs for heat, and compare them to counterparts for hurricanes, a classic sudden-onset disaster. Other multi-sectoral reports of heat impacts have been compiled by other entities, including SwissRe and The Atlantic Council Climate Resilience Center.

We identified 3,478 deaths with a cause of “cataclysmic storms” (e.g., hurricanes; International Classification of Disease Code X.37) and 14,461 deaths with a cause of heat (X.30) between 1999-2020 using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC). It is important to note that the CDC database only includes death certificates that list heat as a cause of death, while it is widely recognized that this can be a significant underaccount. However, despite these limitations, CDC remains the most comprehensive national dataset for monitoring mortality trends.

HUD can play an important role in reducing heat mortality. In the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Dome, most of the deaths occurred indoors (reportedly 98% in British Columbia) and many in homes without adequate cooling. In hotter Maricopa County, Arizona, in 2024, 49% of all heat deaths were among people experiencing homelessness and 23% occurred in the home. Therefore, across the U.S., HUD programs could be a critical lever in protecting public health and safety by providing housing and ensuring heat-safe housing.

Agricultural Labor

Farmworkers are particularly vulnerable to extreme heat, and housing can be part of a solution to protect them. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), between 1992 to 2022, 986 workers across industry sectors died from exposure to heat, with agricultural workers being disproportionately affected. According to the Environmental Defense Fund, farmworkers in California are about 20 times more likely to die from heat-related stress, compared to the general population, and they estimate that the average U.S agricultural worker is exposed to 21 working days in the summer growing season that are unsafe due to heat. A study found that the number of unsafe working days due to extreme heat will double by midcentury, increasing occupational health risks and reducing labor productivity in critical sectors. Adequate cooling in the home could help protect outdoor workers by facilitating cooling periods during nonwork hours, another way in which HUD could have a positive impact on heat.

Infrastructure and Vulnerability

Rising temperatures significantly increase energy demand, particularly due to the widespread reliance on air conditioning. This surge in demand increases the risk of power outages during heat events, exacerbating public health risks due to potential grid failure. In urban areas, the built environment can add heat, while in rural areas residents are at greater risk due to the lack of infrastructure. This effect contributes to increased cooling costs and worsens air quality, compounding health vulnerabilities in low-income and urban populations. All of these impacts are areas where HUD could improve the situation through facilitating and encouraging energy-efficient homes and cooling infrastructure.

Costs