How Should FESI Work with DOE? Lessons Learned From Other Agency-Affiliated Foundations

In May, Secretary Granholm took the first official step towards standing up the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) by naming its inaugural board. FESI, authorized in the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 and appropriated in the FY24 budget, holds a unique place in the clean energy ecosystem. It can convene public-private partnerships and accept non-governmental and philanthropic funding to spur important projects. FESI holds tremendous potential for empowering the DOE mission and accelerating the energy transition.

Through the Friends of FESI Initiative at FAS, we’ve identified a few opportunities for FESI to have some big wins early on – including boosting next-generation geothermal development and supporting pilot stage demonstrations for nascent clean energy technologies. We’ve also written about how important it is for the FESI Board to be ambitious and to think big. It’s important that FESI be intentional and thoughtful about the way that it’s structured and connected to the Department of Energy (DOE). The advantage of an entity like FESI is that it’s independent, non-governmental, and flexible. Therefore, its relationship to DOE must be complementary to DOE’s mission, but not tethered too tightly. FESI should not be bound by the same rules as DOE.

While the board has been organizing itself and selecting a leadership team, we’ve been gathering insights from leaders at other Congressionally-chartered foundations to provide best practices and lessons learned for a young FESI. Below, we make a case for the mutually-beneficial agreement that DOE and FESI should pursue, outline the arrangements that three of FESI’s fellow foundations have with their anchor agencies, and highlight which elements FESI would be wise to incorporate based on existing foundation models. Structuring an effective relationship between FESI and DOE from the start is crucial for ensuring that FESI delivers impact for years to come.

Other Transactions Agreements (OTA)

If FESI is going to continue to receive Congressional appropriations through DOE, which we hope it will, it should be structured from the start in a way that allows it to be as effective as possible while it receives both taxpayer dollars and private support. The legal arrangement between FESI and DOE that most lends itself to supporting these conditions is an Other Transactions (OT) agreement. Congress has granted several agencies, including DOE, the authority to use OTs for research, prototype, and production purposes, and these agreements aren’t bound by the same regulations that government contracts or grants are. FESI and DOE wouldn’t have to reinvent the wheel to design a mutually beneficial OT agreement after looking at other shining examples from other agencies.

Effective Use of an Other Transactions Agreement Between FNIH and NIH

Many consider the gold standard of public-private accomplishment – made possible through an Other Transactions Agreement – to be a partnership first ideated in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. Leaders at the National Institute of Health (NIH) and the Foundation for National Institute of Health (FNIH) were faced with an unprecedented need for developing a vaccine on an accelerated timeline. In a matter of weeks, these leaders pulled together a government-industry-academia coalition to coordinate research and clinical testing efforts. The resulting partnership is called ACTIV (Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccines) and includes eight U.S. government agencies, 20 biopharmaceutical companies and several nonprofit organizations.

Like the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change is a global crisis. Expedited energy research, commercialization, and deployment efforts require cohesive collaboration between government and the private sector. Other Transactions consortia like ACTIV pool together the funding to support some of the brightest minds in the field, in alignment with the national agenda, and return discoveries to the public domain. Pursuing an OT agreement allowed the FNIH and NIH to act swiftly and at the scale required to begin to tackle the task of developing a life-saving vaccine.

What We Can Learn from Other Agency-Affiliated Foundations

FESI Needs to Find its Specific Value-Add and then Execute

The allure of an independent, non-governmental foundation like FESI is pretty straightforward. Unencumbered by traditional government processes, agency-affiliated foundations are nimble, fast-moving, and don’t face the same operational barriers as government when working with the private sector. They can raise and pool funds from private and philanthropic donors. For that reason, it’s crucial that FESI differentiates itself from DOE and doesn’t become a shadow agency. Although FESI’s mission aligns with that of the DOE’s, and may focus on programs similar to those of ARPA-E, there is a drastic difference between being a federal agency and being a foundation affiliated with a federal agency.

FESI’s potential relies on its ability to be independent enough to take risks while still maintaining a strong relationship with DOE and the agency’s mission. FESI’s goals should be aligned with DOE’s through frequent communication with the agency – to understand priorities, opportunities, and barriers it might face in achieving those goals. In reality, neither FESI nor DOE can directly instruct the other what to do, but the two entities should be aligned and aware of what the other is doing at all times.

Additionally, a young FESI should figure out what it can do that DOE can’t and then capitalize on that. The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR), for example, was established with a specific purpose of convening public private partnerships. At the time, the USDA struggled to connect with industry. FFAR found its benefit by serving as a more flexible extension of the agency’s aims. FESI could play a similar role – acting in concert with DOE, but playing different instruments.

More important than the agreement are the relationships between FESI and DOE leaders and staff

Pursue a flexible agreement that can be revisited and revised

Whatever relationship structure DOE and FESI decide on needs to be flexible enough so that they can both exercise the relationship required to tackle problems together. The agreement needs to be more than a list of what FESI can and can’t do. Based on other foundations’ experiences, it is best to revisit, revise, and refresh the document every so often. An ancient contract collects dust and doesn’t serve FESI or DOE. Luckily, Other Transactions agreements can be amended at any time.

Select a strategic executive director with a vision

DOE is racing against time to commercialize the clean energy technology needed to solve difficult decarbonization challenges. With FESI’s strength being its agility and ability to act quickly, the foundation is poised to be an invaluable asset to DOE’s mission. Whomever the FESI Board designates to lead this fight must walk in on day one with a clear, focused vision ready to fund projects that earn wins and to work with the board to make good on their promises. One of the first challenges they will face will be educating the ecosystem about FESI’s role and purpose. A clearly articulated answer to, “What does FESI hope to accomplish?” is key for fundraising and program design and execution.

Being FESI’s first ever executive director is no small feat and the board’s selection should be a quick study who has proven experience under their belt for fundraising and managing nine-figure budgets – the scale that we hope FESI is one day able to operate at. A successful leader will have high credibility throughout the energy system and with both political parties. They will bring with them networks that span sectors and add on to those of the board members. With these assets in tow, the Secretary of Energy should be excited about the FESI executive director and eager to work with them.

The agreement is the backstop, but the game is played at the plate

An overarching theme across each agency-affiliated foundation is the importance of agency-foundation relationships that are based on deep trust. One foundation leader even said, “It’s really not about the paper – [the structuring agreement] – at all.” Instead, they said, the success of an agency and its foundation runs on “tacit knowledge and relationships” that will grow over time between foundation and agency. Clearly, an agreement needs to be in place between FESI and DOE, but if the organization “runs exclusively off those pieces of paper, it won’t be its best self.”

As a young FESI grows over time, leaders of each organization – the FESI executive director and the Secretary of Energy – and the board and the executive director should all be in close contact with one another. Any of these folks should be able to pick up the phone, dial their counterpart, and give them good – or bad – news directly. These relationships should be prioritized and fostered, especially early on.

Create and raise the profile of FESI as early as possible

By far the greatest benefit of DOE having an agency-affiliated foundation is that FESI can raise and distribute funding more quickly and more efficiently than DOE will ever be able to. This can be a great driver for DOE success as FESI’s role is to support the agency. The FNIH, for example, can raise funding from biopharma, send it into projects, and then grant it out, all while avoiding cumbersome procedures since that money doesn’t belong to taxpayers.

To successfully fundraise, FESI will need the staff and the infrastructure needed to identify and execute on promising projects. Leaders at other foundations have found that their respective funder ecosystems are drawn to projects that fill a gap and that convene the public and private sectors. Whenever possible, and to the extent possible, FESI should aim to pool funding from different streams by convening consortia – in order to avoid the procedural strings attached to receiving federal dollars. One example, the Biomarkers Consortium, led by the FNIH, pools funding from government, for-profit, and non-profit partners. Members of this consortium pay annual dues to participate and contribute their scientific and technical expertise as advisors.

How Do Other Congressionally-chartered Foundations Work with Their Agencies?

The Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research and the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture

In the first year of the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR), it had $200 million from Congress, one staff member, and no reputation to fundraise off of. By year three, FFAR had established its first public-private consortium – composed of companies and global research organizations working to develop crop varieties to meet global nutritional demands in a changing environment. FFAR provided the Crops of the Future Collaborative with an initial $10 million investment that was matched by participants for a total investment of $20 million. The law requires that the foundation matches every dollar of public funding with at least one dollar from a private source. This partnership marked FFAR’s first big, early win that set the young foundation on a road to success.

FFAR is unique among its fellow foundations as it doesn’t receive any funding from USDA. Instead, FFAR receives appropriations from the Farm Bill about every five years as mandatory funding that doesn’t go through the regular appropriations process. Because of this, this funding is separate from that of the USDA’s so the funding streams remain separate and not in competition with one another. While FFAR doesn’t receive money from USDA, USDA can receive grants from FFAR and the two entities conduct business in close coordination with one another. Whenever FFAR identifies a program for launch, its staff run the possibility past the USDA to ensure that FFAR is filling a USDA gap and that there isn’t any programmatic overlap.

A memorandum of understanding (MOU) is the legal agreement of choice that structures the relationship between USDA and FFAR. This document describes how the two exchange with each other and is updated every other year. In addition, FFAR has USDA representatives sit as ex-officio members of its board. While FFAR remains to this day quite independent of the USDA, according to staff, the agency is a “valued piece” of the work of the foundation.

In addition to having an MOU with USDA, FFAR has MOUs and funding agreements with each of the corporations in their consortia. These funding agreements either give FFAR money or fund the project directly. The foundation’s public private partnerships are generally funded through a competitive grants process or through direct contract; however, the foundation also uses prize competitions to encourage the development of new technologies.

When it comes to fundraising as a science-based organization, FFAR has encountered distinct challenges. Most of its fundraising is done by its Executive Director and scientists who solicit funding for each of its six main research focus areas. Initially, in 2016, these six “Challenge Areas” were selected by the board of directors using stakeholder input to address urgent food and agricultural needs. Recently, FFAR has pivoted to a framework that is based on four overarching priority areas – Agroecosystems, Production Systems, Healthy Food Systems and Scientific Workforce Development. Defining focus areas creates clarity and structure for a foundation working in an overwhelming abyss of opportunity. It would be wise for FESI leadership to define a handful of focus areas to hone in on in its early rounds of projects.

Most of FFAR’s fundraising efforts are on a project and program basis, instead of finding high net-worth individuals that will donate large sums of untethered money. To be a successful fundraiser, FFAR leaders must be able to clearly articulate the vision of the foundation, locate projects that will appeal to donors, and also be able to articulate the benefits to donors (i.e. receiving early access to information or notice of publications). FFAR leaders have found that projects that promise to fill gaps between the public and private sector have proven highly enticing amongst the funder community.

The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health and The National Institutes of Health

The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) is going on its 35th year advancing the mission of the NIH and leading public-private partnerships that advance breakthrough biomedical discoveries. Its authorizing statute has been amended slightly since it was initially passed in 1990, but its language served as a model for FESI’s authorization legislation.

The FNIH statute does not lay down specific rules or regulations for projects or programs that the organization is confined to. Instead, it allows the foundation to do whatever its leaders decide, as long as it relates to NIH and there’s a partner from the NIH involved. Per law, the NIH Director is required to transfer “not less than $1.25 million and not more than $5 million” of the agency’s annual appropriations to FNIH. Between FY2015 and FY2022, NIH transferred between $1 million and $1.25 million annually to FNIH for administrative and operational expenses (less than 0.01% of NIH’s annual budget).The FNIH and the NIH also have a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) signed to facilitate the legal relationship between each organization, though this agreement has aged since it was signed and the relationship in practice is more informal.

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the Fish and Wildlife Service

The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF), chartered by Congress to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), is the nation’s largest non-governmental conservation grant-maker. In fiscal year 2023 alone, the NFWF awarded $1.3 billion to 797 projects that will generate a total conservation impact of $1.7 billion.

NFWF doesn’t have a guiding agreement, like an MOU, with FWS. Instead, it uses the text language in the initial authorizing legislation. Since its inception, NFWF has built cooperative agreements with roughly 15 other agencies and 150 active federal funding sources. These agreements function as mechanisms through which agencies can transfer appropriated funds over to NFWF to administer and deploy to projects on the ground. These cooperative agreements are revisited on a program-specific basis; some are revised annually, while others last over a five-year period.

Congress mandates that each federal dollar NFWF awards is matched with a non-federal dollar or “equivalent goods and services.” NFWF also has its own policy that it aims to achieve at least a 2:1 return on its project portfolio — $2 raised in matching contributions to every federal dollar awarded. This non-federal funding comes from conservation-focused philanthropic foundations, but also project developers needing to fulfill regulatory obligations, or even from legal settlements, such as in the case of NFWF receiving $2.544 billion from BP and Transocean to fund Gulf Coast projects impacted by the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

To distribute this money, NFWF solicits its own requests for proposals (RFP), separate from FWS, and awards roughly 98% of its grants to NGOs or state/local governments. If it wanted, FWS could apply to or be a joint applicant to receive a grant issued by NFWF. Earlier this year, NFWF announced an RFP – the “America the Beautiful Challenge” – that pooled funds $119 million from multiple federal agencies and the private sector to eventually award to project applicants working to address conservation and public access needs across public, Tribal, and private lands. NFWF has review committees composed of NFWF staff and third-party expert consultants or members of other involved agencies. These committees converge to discuss a proposed slate of projects to decide which move forward before the NFWF Board delivers its seal of approval.

While NFWF is regarded as a successful model of a foundation supporting several federal agencies, its accomplishments are slightly distinct from what FESI has been created to do. As a 501(c)3, NFWF is able to channel funds from various sources, both public and private, to support projects that comply with federal conservation and resilience requirements. NFWF works closely with the Department of Defense to fund resilience projects that protect military bases and nearby towns against natural disasters in coastal areas. With just under 200 employees, NFWF is also able to serve as a “release valve” for agencies that do not have the workforce capacity to handle the influx of work generated by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) or Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), for example. While FESI could take on projects that DOE doesn’t have the capacity or agility to handle, it should also operate independently and aim to act on ideas that originate from outside of DOE.

Takeaways for FESI

The foundations that have preceded FESI, each chartered by Congress to support the mission of federal agencies, have proven that these models can be successful. They have supported public-private partnerships to produce life-saving vaccines, breakthrough discoveries in food and agriculture, and to more quickly distribute grants to conservation organizations on the ground. FESI was authorized and appropriated by Congress to accelerate innovation to support the global transition to affordable and reliable low-carbon energy. Its inaugural board is now tasked with choosing leadership and pursuing strategic projects that will put FESI on a path to accomplishing the goals set before it.

In order to deliver on its potential, FESI should initially select focus areas that will guide the foundation’s projects intentionally and methodically, like FFAR has done. Foundation leaders should also pursue a flexible legal arrangement with DOE that allows leaders from both entities to work together freely and flexibly. An Other Transactions Agreement is an ideal choice to structure this agreement, as it can be revisited as often as desired and frees transactions between DOE and FESI from regulations that government contracts or grants are bound by. FESI’s potential contributions to the global energy transition and national security rely on its ability to be independent enough to take risks while simultaneously pursuing projects that complement DOE’s mission. An effective legal agreement that structures the foundation’s relationship with DOE will ensure that FESI delivers impact for years to come.

Get Ready, Get Set, FESI!: Putting Pilot-Stage Clean Energy Technologies on a Commercialization Fast Track

It may sound dramatic, but “Valleys of Death” are delaying the United States’ technology development progress needed to achieve the energy security and innovation goals of this decade. As emerging clean energy technologies move along the innovation pipeline from first concept to commercialization, they encounter hurdles that can prove to be a death knell for young startups. These “Valleys of Death” are gaps in funding and support that the Department of Energy (DOE) hasn’t quite figured out how to fill – especially for projects that require less than $25 million.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates that to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, almost 35% of CO2 emissions to avoid require technologies that are not yet past the demonstration stage. It’s important to note that this share is even higher in harder-to-decarbonize sectors like long-haul transportation and heavy industry. To reach this metric, a massive effort within the next ten years is needed for these technologies to reach readiness for deployment in a timely manner.

Although programs exist within DOE to address different barriers to innovation, they are largely constrained to specific types of technologies and limited in the type of support they can provide. This has led to a discontinuous support system with gaps that leave technologies stranded as they wait in the “valleys of death” limbo. A “Fast Track” program at DOE – supported by the CHIPS and Science-authorized Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) – would remove obstacles for rapidly-growing startups that are hindered by traditional government processes. FESI is uniquely positioned to be a valuable tool for DOE and its allies as they seek to fill the gaps in the technology innovation pipeline.

Where does FAS come in?

The Department of Energy follows the lead of other agencies that have established agency-affiliated foundations to help achieve their missions, like the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) and the Foundation for Food & Agriculture Research (FFAR). These models have proven successful at facilitating easier collaboration between agencies and philanthropy, industry, and communities while guarding against conflicts of interest that might arise from such collaboration. Notably, in 2020, the FNIH coordinated a public-private working group, ACTIV, between eight U.S. government agencies and 20 companies and nonprofits to speed up the development of the most promising COVID-19 vaccines.

As part of our efforts to support DOE in standing up its new foundation with the Friends of FESI Initiative, FAS is identifying potential use cases for FESI – structured projects that the foundation could take on as it begins work. The projects must forward DOE’s mission in some way, with a particular focus on accelerating clean energy technology commercialization.

In early April, we convened leaders from DOE, philanthropy, industry, finance, the startup community, and fellow NGOs to workshop a few of the existing ideas for how to implement a Fast Track program at DOE. We kicked things off with some remarks from DOE leaders and then split off into four breakout groups for three discussion sessions.

In these sessions, participants brainstormed potential challenges, refinements, likely supporters, and specific opportunities that each idea could support. Each discussion was focused around what FESI’s unique value-add was for each concept and how best FESI and DOE could complement each other’s work to operationalize the idea. The four main ideas are explored in more detail below.

Support Pilot-scale Technologies on the Path to Commercialization

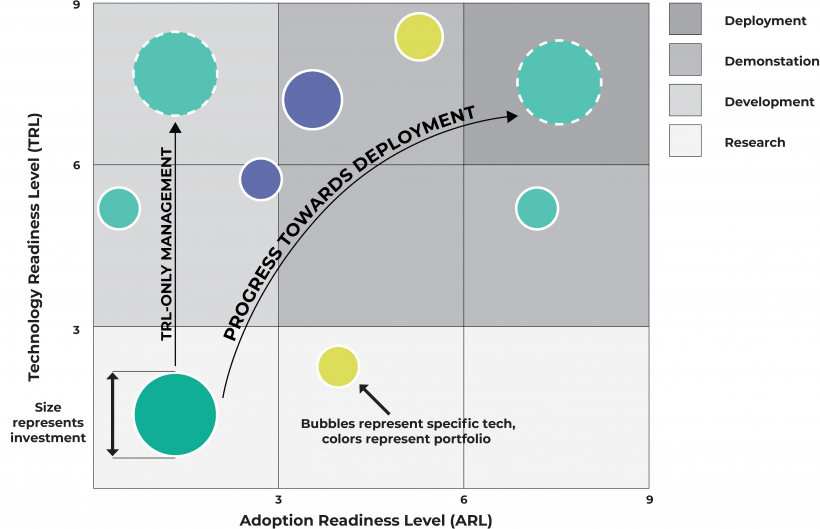

The technology readiness level (TRL) framework has been used to determine an emerging technology’s maturity since NASA first started using it in the 1970s. The TRL scale begins at “1” when a technology is in the basic research phase and ends at “9” when the technology has proven itself in an operating environment and is deemed ready for full commercial deployment.

However, getting to TRL 9 alone is insufficient for a technology to actually get to demonstration and deployment. For an emerging clean technology to be successfully commercialized, it must be completely de-risked for adoption and have an established economic ecosystem that is prepped to welcome it. To better assess true readiness for commercial adoption, the Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) at the Department of Energy (DOE) uses a joint “TRL/Adoption Readiness Level (ARL)” framework. As depicted by the adoption readiness level scale below, a technology’s path to demonstration and deployment is less linear in reality than the TRL scale alone suggests.

Source: The Office of Technology Transitions at the Department of Energy

There remains a significant gap in federal support for technologies trying to progress through the mid-stages of the TRL/ARL scales. Projects that fall within this gap require additional testing and validation of their prototype, and private investment is often inaccessible until questions are answered about the market relevance and competitiveness of the technology.

FESI could contribute to a pilot-scale demonstration program to help small- and medium-scale technologies move from mid-TRLs to high-TRLs and low to medium ARLs by making flexible funding available to innovators that DOE cannot provide within its own authorities and programs. Because of its unique relationship as a public-private convener, FESI could reach the technologies that are not mature enough, or don’t qualify, for DOE support, and those that are not quite to the point where there is interest from private investors. It could use its convening ability to help identify and incubate these projects. As it becomes more capable over time, FESI might also play a role in project management, following the lead of the Foundation for the NIH.

Leverage the National Labs for Tech Maturation

The National Laboratories have long worked to facilitate collaboration with private industry to apply Lab expertise and translate scientific developments to commercial application. However, there remains a need to improve the speed and effectiveness of collaboration with the private sector.

A Laboratory-directed Technology Maturation (LDTM) program, first ideated by the EFI Foundation, would enable the National Labs to allocate funding for technology maturation projects. This program would be modeled after the highly successful DOE Office of Science Laboratory-directed Research and Development (LDRD) program and it would focus on taking ideas at the earliest Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) and translating them to proof of concept—from TRL 1 and 2 to TRL 3. This program would translate scientific discoveries coming out of the Labs into technology applications that have great potential for demonstration and deployment. FESI could assist in increasing the effectiveness of this effort by lowering the transaction costs of working with the private sector. It could also be a clearinghouse for LDTM-funded scientists who need partners for their projects to be successful, or could support an Entrepreneur-in-Residence or entrepreneurial postdoc program that could house such partners.

While FESI would be a practical convener of non-federal funding for this program, the magnitude of the funding needed to establish this program may not be well-suited for an initial project for the foundation to take on. It is estimated that each project would be in the ballpark of $5-20 million, and funding a full portfolio, which private sponsors are more likely to be interested in, is a nine-figure venture. Supporting a LDTM program is a promising idea for further down the line as FESI grows and matures.

Align Later-stage R&D Market Needs with Corporate Interest via a Commercialization Consortium

Industry and investors often struggle to connect with government-sponsored technologies that fit their plans and priorities. At the same time, government-sponsored researchers often struggle to navigate the path to commercialization for new technologies.

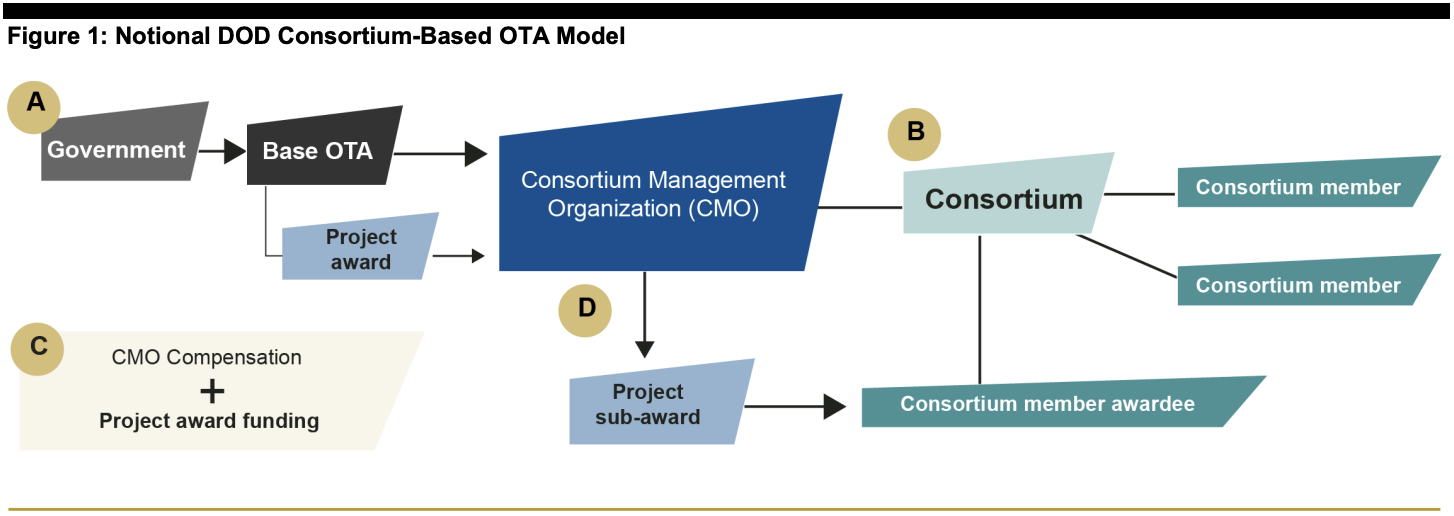

Based on a model widely-used by the Department of Defense (DOD), an open consortium is a mechanism and means to convene industry and highlight relevant opportunities coming out of DOE-funded work. The model creates an accessible and flexible pathway to get U.S.-funded inventions to commercial outcomes.

FESI could function as the Consortium Management Organization (CMO), pictured below, to help structure interactions and facilitate communications between DOE sponsors and award recipients while freeing government staff from “picking winners.” As the CMO, FESI would issue task orders and handle contracting per the consortium agreement, which would be organized under DOE’s other transactions authority (OTA). In this model, FESI could work with DOE staff in applied R&D offices and OCED to identify opportunities and needs in the development pipeline, and in parallel work with consortium members (including holders of DOE subject inventions, industry partners, and investors) to build teams and scope projects to advance targeted technology development efforts.

This consortium could help work out the kinks in the pipeline to ensure that successful technologies in the applied offices have sufficient “runway” to reach TRL 7, and that OCED has a healthy pipeline of candidate technologies for scaled demonstrations. FESI could mitigate the offtake risk that is known to stall first-of-a-kind projects, like financing a lithium extraction project, for example. Partners in industry and the investment community will be aligned, and potentially provide cost share, in order to gain access to technologies emerging from DOE subject inventions.

The Time is Right

This workshop comes at a prime time for FESI. The Secretary of Energy appointed the inaugural FESI board—composed of 13 leaders in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors—in mid-May. In the coming months, the board will formally set up the organization, hire staff, adopt an agenda, and begin to pursue projects that will make a real impact to advance DOE’s mission. As Friends of FESI, we want to see the foundation position itself for the grand impact it is designed to have.

The above proposals are actionable and affordable projects that a young FESI is uniquely-positioned to achieve. That said, supporting pilot-stage demonstrations is only one area where FESI can make an impact. If you have additional ideas for how FESI could leverage its unique flexibility to accelerate the clean energy transition, please reach out to our team at fesifriends@fas.org. You can also keep up with the Friends of FESI Initiative by signing up for our email newsletter. Email us!

Building a Firm Foundation for the DOE Foundation: It All Starts with a Solid Board

The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) has a vital mission: “to ensure America’s security and prosperity by addressing its energy, environmental and nuclear challenges through transformative science and technology solutions.” In 2022’s CHIPS and Science Act, Congress gave DOE a new partner to accelerate its pursuit of this mission: the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI). As ‘Friends of FESI’ we want to see this new foundation set up from day one to successfully fulfill the promise of its large impact.

Once fully established, FESI will be an independent 501(c)3 non-profit organization with a complementary relationship to DOE. It will raise money from non-governmental sources to support activities of joint interest to the Department and its constituents, such as accelerating commercialization of next-generation geothermal power and bridging gaps in the clean energy technology innovation pipeline.

Judging by the success of other agency-affiliated foundations that served as a template for FESI, the potential for the Foundation’s impact is hefty. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, chartered by Congress to work with the Fish and Wildlife Service, for instance, is the nation’s largest non-governmental conservation grant-maker. In fiscal year 2023 alone, the NFWF awarded $1.3 billion to 797 projects that will generate a total conservation impact of $1.7 billion.

FESI’s creation is timely. As the U.S. races to net-zero, the International Energy Agency estimates that at least $90 billion of public funding needs to be raised by 2026 for an efficient portfolio of demonstration projects. For perspective, the most recent yearly budget for the entire DOE is just slightly more than half of that number. Non-DOE funding to support innovation is essential to ensure that energy remains affordable and reliable. DOE’s mission is a vital national interest, and the Department needs all the help it can get. The stronger FESI is, the more it will be able to help.

This week, Secretary of Energy Granholm took the first official step to create FESI by appointing its inaugural board. The board consists of 13 accomplished members whose backgrounds span the nation’s regions and communities and who have deep experience in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors.

A strong founding board is an essential ingredient in FESI’s success, and we are pleased to see that its members reflect the bipartisan support that FESI has had since legislation to form it was first introduced. While non-partisan technical and market expertise is vital to make objective judgments about hiring and investments, bipartisan relationships will ensure that FESI is sustained through changes of partisan control of Congress and the presidency.

Another key to FESI’s success will be stringent conflict of interest rules. Public-private partnerships, like those that FESI will foster, are always at risk of being subverted to pursue only private ends. It is equally important for FESI to also prioritize transparency and oversight of compliance with these rules to avoid the appearance of any conflict of interest that would undermine its progress.

What Happens Next?

In the coming weeks and months, the FESI board will hire a CEO and other leaders. This board will set FESI’s agenda and initial priorities, and later down the line, it will also eventually appoint its own successors. Its imprint will be long-lasting. The organizational culture the board creates will strongly influence whether FESI will make a real difference for energy, climate, science, national security, and the economy. As ‘Friends of FESI’ we are eager to see what the FESI board decides to take on first.

To learn more about the Inaugural FESI Board nominees, check out the DOE press release here.

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) Applauds the Newly Announced Board Selected to Lead the Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI)

FAS eager to see the Board set an ambitious agenda that aligns with the potential scale of FESI’s impact

Washington, D.C. – May 9, 2024 – Earlier today Secretary of Energy Granholm took the first official step to stand up the Department of Energy-affiliated non-profit Foundation for Energy Security and Innovation (FESI) by appointing its inaugural board. Today the “Friends of FESI” Initiative of the nonpartisan, non-profit Federation of American Scientists (FAS) steps forward to applaud the Secretary, congratulate the new board members, and wish FESI well as it officially begins its first year. The Inaugural FESI Board consists of 13 accomplished members whose backgrounds span the nation’s regions and communities and who have deep experience in innovation, national security, philanthropy, business, science, and other sectors. It includes:

- Jason Walsh, BlueGreen Alliance

- Nancy Pfund, DBL Partners

- Rita Baranwal, Westinghouse Electric

- Vicky Bailey, Anderson Stratton

- Mike Boots, Breakthrough Energy

- Miranda Ballentine, Clean Energy

- Stephen Pearse, Yucatan Rock

- Noel Bakhtian, Bezos Earth Fund

- Mung Chiang, President of Purdue University

- Noelle Laing, Builder’s Initiative Foundation

- Katie McGinty, Johnson Controls

- Tomeka McLeod, Hydrogen VP at bp

- Rudy Wynter, National Grid NY

Since the CHIPS and Science Act authorized FESI in 2022, FAS, along with many allies and supporters who collectively comprise the “Friends of FESI,” have been working to enable FESI to achieve its full potential as a major contributor to the achievement of DOE’s vital goals. “Friends of FESI” has been seeking projects and activities that the foundation could take on that would advance the DOE mission through collaboration with private sector and philanthropic partners.

“FAS enthusiastically celebrates this FESI milestone because, as one of the country’s oldest science and technology-focused public interest organizations, we recognize the scale of the energy transition challenge and the urgency to broker new collaborations and models to move new energy technology from lab to market,” says Dan Correa, CEO of FAS. “As a ‘Friend of FESI’ FAS continues our outreach amongst our diverse network of experts to surface the best ideas for FESI to consider implementing.” The federation is soliciting ideas at fas.org/fesi, underway since FESI’s authorization.

FESI has great potential to foster the public-private partnerships necessary to accelerate the innovation and commercialization of technologies that will power the transition to clean energy. Gathering this diverse group of accomplished board members is the first step. The next is for the FESI Board to pursue projects set to make real impact. Given FESI’s bipartisan support in the CHIPS & Science Act, FAS hopes the board is joined by Congress, industry leaders and others to continue to support FESI in its initial years.

“FESI’s establishment is a vital initial step, but its value will depend on what happens next,” says David M. Hart, a professor at George Mason University’s Schar School of Policy and Government and leader of the “Friends of FESI” initiative at FAS. “FESI’s new Board of Directors should take immediate actions that have immediate impact, but more importantly, put the foundation on a path to expand that impact exponentially in the coming years. That means thinking big from the start, identifying unique high-leverage opportunities, and systematically building the capacity to realize them.”

###

ABOUT FAS

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) works to advance progress on a broad suite of contemporary issues where science, technology, and innovation policy can deliver dramatic progress, and seeks to ensure that scientific and technical expertise have a seat at the policymaking table. Established in 1945 by scientists in response to the atomic bomb, FAS continues to work on behalf of a safer, more equitable, and more peaceful world. More information at fas.org.

Resources

Building a Firm Foundation for the DOE Foundation: It All Starts with a Solid Board

https://fas.org/publication/fesi-board-launch/

FAS use case criteria:

https://fas.org/publication/fesi-priority-use-cases/

FAS open call for FESI ideas:

https://fas.org/publication/share-an-idea-for-what-fesi-can-do-to-advance-does-mission/

DOE announcing FESI board:

https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-appoints-inaugural-board-directors-groundbreaking-new-foundation

DOE release announcing FESI:

https://www.energy.gov/articles/doe-launches-foundation-energy-security-and-innovation

The DOE’s Proactive FY25 Budget Is Another Workforce Win On the Way to Staffing the Energy Transition

The DOE has spent considerable time in the last few years focused on how to strengthen the Department’s workforce and deliver on its mission – including running the largest basic science research engine in the country, and managing a wide range of decarbonization efforts through clean energy technology innovation, demonstration, and deployment. In general, their efforts have been successful – in no small part because they have been creative and have had access to tools like the Intergovernmental Personnel Act and the Direct Hire Authority that supported the Clean Energy Corps.

It’s no surprise then, that the agency’s FY 2025 budget looks to continue investing in the current and future science and energy workforce. The budget suggests DOE offices are thinking proactively about departmental capacity – in both the federal workforce, and beyond it through workforce development programs that actively grow the pool of future scientists.

Current BIL and IRA Talent

As seen below, several DOE offices across the science, innovation and infrastructure domains have requested increases in program direction funding in FY 2025. Program direction funds are an under-valued but critical resource for enabling the energy transition: DOE must be able to recruit and retain expert staff with a high level of technical proficiency who can meet the multi-faceted demands of public service – reviewing proposals, building bridges with industry, maintaining user facilities, and overseeing execution of complex federal technology programs.

These requests also reflect a larger strategy, motivated by the constraints put on federal management funding by IIJA and IRA. First, while those pieces of legislation poured resources into federal energy innovation, they also limited program direction funds to 3% of account spending, which was highly constraining from a talent perspective – even with the creative use of hiring mechanisms like IPAs and various fellowships. In the final energy spending bill for FY 2024, this was raised to 5% and extended the funds connected to IIJA funding from expiring in 2026 to FY 2029 – a much-needed adjustment to the legislation.

Extensions to and increases in program direction funds are vital for DOE. If the levels of appropriated PD funds don’t match the programs and mandate of offices, it jeopardizes their ability to provide oversight, project management, and effective stewardship of taxpayer dollars. New program direction funding is similarly important for offices like the Grid Deployment Office, a new office formed from a combination of programs from IIJA and IRA and the Office of Electricity. The FY 2025 request includes a $40 million increase above FY 2023, including $30 million for a new microgrid initiative intended to strengthen grid reliability and resilience in high risk regions. The Office of Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains is a more extreme example: because of its recent creation, it needs a sharp increase in program direction funds. In FY24 the office received only $1 million in PD funds, while its FY 2025 PD request is $20 million – a much more appropriate number to support the total office budget request of $113 million. These requests are important and necessary for the long-term ability of DOE to continue to fortify U.S. energy independence and innovation.

Future Workforce

Offices are also focused on building pathways for early career scientists to grow their expertise. The Office of Science (SC), DOE’s central hub for basic science research and National Lab oversight, is a prime example. First, SC’s program direction funding is incredibly low for an office of its size and magnitude, and it has steadily declined over the past several years to less than 3% of the SC appropriations as of FY 2023. The FY 2025 request increase of 8% will help remedy this.

SC has also focused on increasing funding for their workforce development programs, and specifically the Workforce Development for Teachers and Scientists (WDTS) and its Reaching a New Energy Sciences Workforce (RENEW) programs. Both received an increase of $1-2 million – although one of WDTS’s other programs, the Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI), was reduced by about $1 million. For most of the WDTS programs, high housing and living costs are cited as a reason for the need for increasing support. These high costs have been cited as a barrier to workforce development at many of the National Labs as well. Congress should explore opportunities to be creative with stipends and program accessibility – to ensure that SC can continue to support workforce development at all levels.

DOE’s FY25 Budget Request Remains Committed to the U.S. Transition to Clean Energy

The Biden Administration has prioritized the clean energy transition as a core element of its governing agenda, via massive legislative victories like the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL), and through its ongoing whole-of-government focus on clean innovation. The Administration has continued to push for further investments, but faces a difficult fiscal environment in Congress – which has meant shortfalls for many priority areas like funding for CHIPS and Science. In March, the Administration released the FY 2025 budget request for the Department of Energy (DOE), and with it seeks to extend the gains of the past few years. This blog post highlights a selection of priority proposals in the FY 2025 request.

Scaling Clean Energy Technologies

BIL and IRA gave DOE a new mandate to support the demonstration, deployment, and commercialization of clean energy technologies, and established the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) to achieve this. OCED is tasked with managing a range of large-scale commercial demonstration programs, which provide cost-share funding on the order of $50 to $500 million. OCED’s $30 billion portfolio of BIL- and IRA-funded programs include the Industrial Demonstrations Program, which recently announced selections for award negotiations; the Regional Clean Hydrogen Hubs; the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Projects; and others.

Now that the majority of its BIL and IRA funding has been awarded, OCED is looking to continue building on this momentum, but annual appropriations have not been easy. OCED last year sought to significantly ramp up its annual appropriations to $215 million, but appropriators ended up providing only $50 million in new funding to OCED – nearly 50% less than FY23. Such an outcome hinders OCED’s ability to launch first-of-a-kind demonstration programs in new areas or expand existing programs, particularly since several OCED programs (like most IIJA and IRA initiatives) are vastly oversubscribed. For instance, OCED’s Industrial Demonstrations program provided awards of $6.3 billion, but received 411 concept papers requesting over $60 billion in federal funding with $100 billion in matching private dollars. Other programs at OCED, including the Energy Improvements in Rural and Remote Areas and the Clean Hydrogen Hubs, were similarly oversubscribed.

For FY 2025, OCED is again proposing a funding ramp-up to $180 million. This includes a new extreme heat demonstration program in collaboration with DOE’s Office of State and Community Energy Programs (SCEP). SCEP has requested $35 million to lead the planning and design phases, while OCED’s request of $70 million will fund the federal cost-share for three to six community-scale demonstration projects. The new program will provide much needed funding for solutions to address extreme heat, which is the top weather-related cause of death for Americans and is only expected to worsen with global temperatures increasing each year.

In addition to OCED’s portfolio, BIL funded a $5 billion Grid Innovation Program (GRIP) managed by the Grid Deployment Office (GDO). GRIP focuses on central grid infrastructure, but GDO also has a portfolio of work on microgrids, which improve resiliency by enabling communities to maintain electricity access even when the larger grid goes down. BIL established some programs that can be used to fund certain components of microgrids or to purchase microgrid capacity, but these programs are unable to fund full scale microgrid demonstration projects. For FY 2025, GDO is requesting $30 million for a new Microgrid Generation and Design Deployment Program that will fill that gap.

Complementary to these large-scale demonstration programs are a suite of small-scale pilot demonstration programs managed by offices under the Under Secretary for Science and Innovation (S4), which provide grants that are typically less than $20 million.

Within the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE), the Geothermal Technologies Office (GTO) has been running a rolling funding opportunity for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) pilot demonstrations, authorized by BIL and funded by annual appropriations. For FY 2025, GTO is requesting continued funding for this program so that they can support additional greenfield demonstration projects.

EGS is important as a future source of clean, firm energy, but it’s not the only promising next-generation geothermal technology, as closed-loop geothermal has also demonstrated the potential to be cost-competitive with EGS. Currently, only EGS projects are eligible in GTO’s program, despite the fact that BIL and prior legislation intended a more inclusive approach. As such, the Federation of American Scientists has joined with the next-generation geothermal community—including organizations representing both EGS and closed-loop geothermal companies—to call on DOE to take a tech agnostic approach and expand the scope of the program to include all next-generation technologies. We also call on Congress to adopt report language directing DOE to include demonstration projects using closed-loop and other next-generation geothermal technologies, and to appropriate at least GTO’s full budget request of $156 million.

Other proposed demonstration activities across the DOE enterprise include:

- Demonstration programs for reservoir thermal energy storage and thermal energy networks within GTO’s low temperature and coproduced resources portfolio ($24 million);

- Demonstration of wind hybrid systems, which use wind energy to produce hydrogen for energy storage or direct industrial usage, by the Wind Energy Technologies Office ($23.5 million);

- Expansion of in-water demonstrations of grid-scale wave energy devices at the Water Power Technologies Office’s testing facility PacWave ($50 million);

- Validation and demonstration of heat pumps and energy efficiency retrofits in commercial and residential buildings by the Building Technologies Office ($27 million and $32.5 million, respectively);

- Demonstration and validation of a new grid technology by the Office of Electricity ($7 million); and

- Support from the Office of Nuclear Energy to help address the technical, operational, and regulatory challenges facing five potential future demonstration projects, as a part of the Advanced Reactor Demonstration Program ($142.5 million).

Tech Transitions and FESI

The Office of Technology Transitions (OTT) was established in 2015 to get the most out of DOE’s RD&D portfolio by better aligning the Department’s science research enterprise with industry and public needs. A core part of OTT’s mission is to expand the commercial impact of DOE’s research investments by developing viable market pathways for technologies coming out of the National Labs. Despite having a relatively small budget, OTT’s mission is crucial for the rapid acceleration of the energy transition.

In FY 2024, however, OTT’s budget was cut by 10% which put a damper on the Office’s ability to carry out its mission. In response, in FY25, OTT is seeking $7.1 million more than its $20 million budget from the previous fiscal year in an attempt to ramp up funding for its programs. This increase also includes a separate funding line item of $3 million for the Foundation of Energy Security and Innovation (FESI), the DOE-affiliated 501(c)3 nonprofit organization established in the CHIPS and Science Act. FESI has significant potential to complement DOE’s mission by being a flexible tool to accelerate clean energy innovation and commercialization. Since the Foundation is a non-federal entity, it can catalyze public-private collaboration and raise private and philanthropic capital to put towards specific projects like funding pilot wells for next-generation geothermal power or filling funding gaps for pilot-scale technologies along the innovation pipeline, for example.

In addition to overseeing the standing up of FESI, OTT facilitates five main programs including the Technology Commercialization Fund, the Energy I-Corps Program, the Lab Partnering Service, the EnergyTech University Prize, and the Technology Commercialization Internship Program. Each of these programs is designed to increase industry and innovator access to the Labs while also bolstering the commercial pathway for emerging energy technologies, and together they’re vital to the success of clean energy technology commercialization.

Opportunities for Support Through Congressional Control Points

The FY 2025 DOE request also looks to support the vital work of several new offices by establishing Congressional control points – meaning they’d be treated as standalone entities in appropriations, rather than subaccounts of other offices. Last year’s request sought new control points for the Office of State and Community Energy Programs, Federal Energy Management Program, and Manufacturing and Energy Supply Chains, but Congress has yet to act.

It’s an incredibly wonky topic, but it’s actually pretty important: establishing control points for these offices can help create a baseline for future funding and maintain institutional consistency. Becoming standalone offices can also help them carry out their missions, by giving them the authority to engage with other partners including federal agencies, creating more pathways for collaboration with energy-intensive agencies like the Defense Department.

Dr. Omer Onar, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Moving the Needle on Wireless Power Transfer

The Office of Technology Transfers is holding a series of webinars on cutting-edge technologies being developed at the DOE National Labs – and the transformative applications they could have globally for clean energy. We sat down with the people behind these technologies – the experts who make that progress possible. These interviews highlight why a strong energy workforce is so important, from the lab into commercial markets. These interviews have been edited for length and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DOE. Be sure to attend DOE’s next National Lab Discovery Series webinar on wireless power transfer technology on Tuesday, April 30.

Dr. Omer Onar was always interested in solving mechanical problems. From his initial engineering degrees in Turkey to his selection as a Weinberg Fellow at the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Dr. Onar has been pushing forward the field of power electronics and electromagnetics for almost two decades. His work today may enable faster, more secure wireless charging for electric vehicle fleets, mobile devices, household appliances, and more.

Beginnings at the Illinois Institute of Technology

After completing both an undergraduate and graduate degree in electrical engineering in his home country of Turkey, Dr. Onar chose to pursue his PhD at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT). Although he received offers from multiple prestigious universities, he chose to attend IIT because of its personalized approach to research and study. “They had a young and energetic team who all loved working together. I was basically told that if I went to one of the larger institutions, I wouldn’t see my advisor for the first few years.”

Because of the standards of the program, its strong pace, and the quality of the professors and advisors, Dr. Onar was able to publish multiple journal articles and receive several citations of his work, all before completing the degree.

Throughout all of his degrees, Dr. Onar cultivated a lifelong passion for understanding the mechanical side of engineering. “In high school, I wasn’t as much interested in electrical engineering, things like magnetics and optics that are more virtual – I liked the mechanics and being able to touch and see the things I was working on.”

A Weinberg Fellow at Oak Ridge

Before he even graduated from IIT, Dr. Onar had an offer from Oak Ridge National Laboratory to become a Weinberg Fellow. The Weinberg Fellowship, named after the former director of the Lab, is targeted at exceptional researchers and is only offered to two or three scientists lab-wide. It not only gave Dr. Onar his start at the Lab, but also allowed him to spend 50% of his time pursuing independent research in his first few years – an invaluable experience for any engineer.

“Since [joining the Lab], I have been so enthusiastic about working here – I’ve never looked at any other opportunities because the Lab offers such a great research environment. We work with academia, industry, and research, so I have the ability to reach out to all flavors of work environments.”

After 14 years of working at the Lab, Dr. Onar has had the opportunity to work on a number of different projects related to electrical engineering and power systems. His research led him to focus primarily on wireless power transfer technologies and especially the wireless charging of electric vehicles.

The Power of Wireless Transfer

Dr. Onar’s research has massive implications for a decarbonized world – not just in how we charge electric vehicles, but also in terms of fuel efficiency, health and safety, human capital planning, critical minerals, and internet access. He’s been working on developing technologies for wireless power transfer – more simply, tech that would allow for wireless charging of electronics.

More advanced wireless power transfer will open up what’s possible for entire industries. It will allow individual consumers to charge their electric vehicles through the surface they drive or park on, without plugging it in – which is a great convenience. But more importantly, the tech could be used to improve employee safety. Drivers for companies with large vehicle fleets are contracted for just that – driving. When companies use electric fleets, it requires an entire additional set of infrastructure for charging that those drivers are not qualified to use safely. This requires additional employees whose sole responsibility is to unplug and plug in vehicles at the beginning and end of the day. Wireless charging automates the whole process and reduces costs while retaining productive and safe jobs.

Wireless charging will also allow for more efficient charging overall. A common concern with electric vehicles is the lack of available charging infrastructure and the long time it takes to fully charge. The technology that Dr. Onar is working on will allow cars to pull off the interstate, into a charging area, charge for 20 minutes without having to plug the vehicle in, and keep driving. This could be extended to commercial heavy-duty vehicles as well – replacing heavy emitting diesel trucks with electric ones and enabling frequent, opportunistic, and ubiquitous wireless charging systems. Wireless charging would allow drivers to load and unload deliveries while continuing to charge, without exposure to harmful pollution.

The Future of Power Systems

Dr. Onar is shaping the technology horizon as well – working with wide bandgap semiconductors and electric motors that no longer require rare earth minerals in their construction. Using materials other than silicon in semiconductors, like silicon carbide or gallium nitride, could enable more applications for wireless power transfer, such as long distance wireless charging, possibly using one transmitter and multiple receivers on each device. For example, imagine walking into a coffee shop and your phone or laptop begins to charge just like the wireless internet connection. In future, this concept could allow for entire homes with refrigerators, washers and dryers, and entertainment systems that are all powered wirelessly.

One barrier to expanding the use of electric vehicles is the lack of reliable access to critical and rare earth minerals used in manufacturing magnets in their motors. The U.S. lacks mining and recycling facilities at the price point and scale needed to increase construction. But Dr. Onar’s team has been researching how to design wound rotor synchronous machines that will eliminate the use of those permanent magnets and help shore up domestic energy security.

“We don’t want to have to rely on another country’s resources in our transportation systems… we’re applying our experience in wireless power transfer systems into the wound rotor synchronous motors, developing and validating enabling technologies to address the challenges in these motors – each one brings us a step closer to commercialization.”

Some of these applications are several years away, but they are a glimpse of what could be possible with the research currently underway in Dr. Onar’s office.

Strengthening the Engineering Community

Dr. Onar has had the opportunity to work with exceptional teams over the course of his career thus far – and some of his proudest accomplishments are the recognition they’ve received on a national level. As a grad student Dr. Onar received two scholarships in addition to his Weinberg Fellowship, and as a Lab employee has received a number of awards for his performance. In 2016, his team received an R&D 100 award – a highly prestigious award recognizing outstanding research and innovation – for their work developing the world’s first 20 – kilowatt wireless charging system for passenger cars. While most systems were designed for 6.6 kW power rating back then, their 20-kW system meant 3 times faster charging with very high efficiency that exceeded 94% – a huge step forward. In addition, his team has received awards from UT-Battelle and the Department of Energy, in addition to several best paper and best presentation awards.

“The R&D 100 awards are the Oscars of research and innovation – it was a once-in-a-lifetime experience to receive one,” he said, with understated pride. Americans should applaud; his work today to improve technologies from our phones to our vehicles will be instrumental to how we live tomorrow.

In addition to his professional recognition, Dr. Onar is actively supporting the next generation of scientists. He contributes his time to the engineering community, serving as the general chair of the Institutes of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC) in 2022 and the general chair of the IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo (ITEC) in 2017. His continuous dedication to advancing technology and his contributions to the field at large have already had an impact far beyond his individual research, and will continue to for decades to come.

Dr. Rebecca Glaser, Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, Energy Storage (for the People) and Policy Expert

This series of interviews spotlights scientists working across the country to implement the Department of Energy’s massive efforts to transition the country to clean energy, and improve equity and address climate injustice along the way. The Federation’s clean energy workforce report discusses the challenges and opportunities associated with ramping up this dynamic, in-demand workforce. These interviews have been edited for length and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DOE. Discover more DOE spotlights here.

Dr. Rebecca Glaser started her career as an engineer in academia. But her interest in the field’s applications for clean energy drove her to take a chance and join the Department of Energy. Now at the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, Dr. Glaser is paving the way for cutting-edge energy storage and battery technologies to scale up. With experience in research, commercialization, and delivering clean energy directly to communities, Dr. Glaser’s background makes her an exceptional example of a clean energy champion.

Discovering the Environmental Application of Materials Science

Dr. Glaser grew up in the Maryland suburbs of Washington, D.C., and was no stranger to the world of public service. Surrounded by an environmentally conscious community, she volunteered throughout high school. She had an early interest in math and science, born of a desire to learn more about the world – but was not sure how to turn it into a career.

In her first year of college, Dr. Glaser ended up in a seminar series focused on the technology of energy that was full of senior undergraduate and graduate students who were all involved in materials science research. Although it was a new field to her, it combined her interest in chemistry and physics with obvious applications – sparking her love for that work. “I realized that all of the people teaching [the seminar] whose research I found interesting were all in materials science, and most of the energy applications I was looking at were being done through that field.”

But even with a field of study in mind, Dr. Glaser was unsure of where to take her passions. She pursued a PhD to dive deeper into batteries and concentrate on one area of technology. “I knew exactly what technology I wanted to work on, but I didn’t know where I wanted to put those skills, whether it was industry or academia. But I didn’t know government was an option.”

Applying the Research

In grad school, however, she explored roads less traveled. While peers were doing internships at Intel and Tesla, Dr. Glaser applied for a position at Resources for the Future, a policy research and analysis organization. As part of the internship, she gained insight into how her work was connected to real-world issues.

“We were writing a case study about coal communities that were working through energy transitions – I focused on one in Ohio, where they were losing or about to lose their coal-fired power plant. We were looking at the effectiveness of government intervention. I was interviewing economic development officials in counties across Ohio about their experiences with federal grants and the communities that benefit from those programs. All in the middle of my very technical battery PhD.”

It was a valuable experience for Dr. Glaser. When she was finishing her PhD and applying for government fellowships, it gave her additional perspectives on how she could use her expertise to make a difference.

Battery Research and Development at the DOE

Dr. Glaser started her work in government as a ORISE Fellow in DOE’s Solar Energy Technologies Office (SETO) – maybe on the surface an unlikely choice for someone interested in batteries, but not to Dr. Glaser. “You can’t really go forward with solar without energy storage – you can only get to a certain point, and I wanted to be that storage expert for them.”

She credits the experience with giving her a lot of learning opportunities, acting as a resource for storage issues, working on program development in topics like recycling, siting, and more. “I learned a lot about how government works – all of its intricacies. It gave me a broader appreciation for the issues behind the science and really helped direct me towards what I wanted to do next.”

Dr. Glaser moved into a position as a Project Officer at the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations last March and then to a position as a Project Manager, focusing full-time on her passion for energy storage. “It’s an exciting time to be in DOE – it was really cool to graduate in 2021 and then have legislation passed that created the office I now work in.” As a project manager, she helps steward these new programs, select projects for the office to fund, and support award negotiations. There’s a long road ahead, but she is excited for their potential impact.

OCED handles a wide range of burgeoning clean energy technologies – and Dr. Glaser feels privileged to be on the cutting edge of what’s possible in energy storage. “Energy storage is so diverse and interesting – I’m excited to see how the different technologies play out and interact with each other, and what I’m able to learn about them.” The office has a hefty mandate, but its ability to respond to support the energy storage needs of the present as well as the decades to come will make a huge difference in achieving a net-zero future.

Stiff Competition to Apply Skills that Make Impactful Contributions

But an office is only as good as the staff that run it. Too often, the world-class talent that keeps the mission going are not recognized for their high-level expertise. Dr. Glaser emphasized that getting to support this vital work is because of years of hard work on her part – and that’s one of her biggest accomplishments.

“The transition I was able to make [into government] is a really hard thing to do It’s giving up the expected path – to go into industry, into a lab, or into a postdoc.”

It’s important to note that SETO, the office Dr. Glaser did her fellowship in has a competitive application pool. She credits her success making the transition to the work she put in conducting informational interviews, taking on work like her internship at Resources for the Future, attending conferences – what she calls the “slow systematic work of understanding this new path and how to get yourself there.”

DOE employees like Dr. Glaser put in that effort because they know the potential for impact is so great. “I am doing the most I can be doing with my job, with the skill set I have. This is the most impactful thing I can do with my skills.”

Dr. Shawn Chen, Office of Science, Practical Science for the Future of Clean Energy

This series of interviews spotlights scientists working across the country to implement the Department of Energy’s massive efforts to transition the country to clean energy, and improve equity and address climate injustice along the way. The Federation’s clean energy workforce report discusses the challenges and opportunities associated with ramping up this dynamic, in-demand workforce. These interviews have been edited for length and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DOE.

With a PhD in materials science, a postdoc position at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and a stint as a AAAS Fellow, Dr. Shawn Chen has had a range of roles in the research community. Now at DOE as a career civil service member, he seeks to combine his technical skills with his passion for public service – to build the foundation for the next generation of clean energy technologies.

Marrying Public Service and Science

Chen’s interest in engineering and materials science started while he was getting his undergraduate degree at UC San Diego. He was chosen to join Dr. Shirley Meng’s research team and started studying how to build stronger, better, and longer lasting batteries. This experience encouraged him to pursue a PhD, and he went on to study how to produce polymer films and materials – and figure out how to make films that use less energy.

It’s important to him that all his research connects back to energy in some way. Dr. Chen grew up in countries where energy was front of mind for his communities. “I grew up in Taiwan and spent two years in Malawi, and you really understand how important energy is. In Taiwan there was a special focus on conserving energy as much as possible. In Malawi, there would be days you wouldn’t have power. Growing up, that was something that was always on the mind.”

But it wasn’t just science that sparked his interest. With family members who had served in the military and a college degree that was funded in part by grants, Dr. Chen has always felt pulled to give back. “I wouldn’t have my education if it weren’t for the support of the country. What better way to do something to pay it back than to join public service?” As a grad student at Northwestern, Dr. Chen balanced his degree work with service in the graduate student government, negotiating on behalf of graduate student workers for better healthcare and working conditions.

Federal Service

With that outlook, the federal government seemed like a natural fit for him. After finishing his PhD, Dr. Chen took a postdoctoral position at the National Institute for Standards and Technology, where he continued his work on polymer films. His first foray into federal service allowed him to conduct research key to energy issues: studying how polymeric films could be used as membranes for fuel cells – for batteries and other energy technology, as well as for water treatment.

Looking for even more of a policy focus in his work, Dr. Chen applied to the AAAS Fellowship, during which he interviewed at several different agencies. But the office that most spoke to him was the Department of Energy’s Office of Science. “What really resonated with me was this mission to keep America at the forefront of science and discovery and innovation…the fundamentals of science.” He got the fellowship, and recently converted to a permanent employee. Now he helps forward that same mission by overseeing and executing the office’s research funding and supporting fellow scientists in making progress on new technologies.

He credits the AAAS Fellowship for giving him the opportunity. “It opened a door for me…without the fellowship, it would be very challenging for someone early in my career to be where I am now. I got a front row seat to how [policy] works behind the scenes.”

The importance of research and development to fighting climate change is under-appreciated, in Dr. Chen’s opinion. “It’s very important to have that foundation. If we don’t have the scientific know-how, how can we innovate? You can’t just be throwing darts at a wall and hope it sticks.”

Because of that, effective and responsible stewardship of DOE’s research funding is one of the Office of Basic Energy Sciences’s core mandates. Dr. Chen plays a key role: reading applications, assigning reviewers, and making sure that projects align with national clean energy goals. Many of these projects “really address some of the climate challenges that we’re facing,” Dr. Chen says. Overseeing these projects and awards is his proudest accomplishment so far. His office played a major role in funding 29 projects with 264 million dollars that study large scale energy storage centers – directly supporting the Long Duration Storage Earth Shot. “The applications were top notch, the reviewers were excellent – and I think these awards will really make a significant change in the decades to come. I’m proud to say I’m a part of that effort.”

Building a Stronger Science Talent Pipeline

It’s not just funding the research – Dr. Chen is helping to bring younger scientists into the fold. DOE’s RENEW program – or Reaching a New Energy Workforce focuses on providing funding opportunities to minority serving institutions and non-R1 research institutions, places that have historically been unrepresented in the Office of Science portfolios. The program’s focus is on training and mentorship. DOE staff spend weeks with participants to engage them and expose them to the research process at the agency. They can create pathways into careers – not only in federal service, but into basic science research.

“Creating that opportunity for people that might not have even heard about clean energy, engineering, or STEM fields is really important. It’s an important piece of building the next generation – not just the technologies, but the people that will do this research.”

Science in the Community

Dr. Chen sees his role as a public servant as going beyond just his day job. He feels a responsibility, not only to serve, support the development of new technologies, and forward key scientific research – but to engage his community in conversation about the importance of DOE’s work.

“A lot of the people I interact with [outside of my work] don’t have a lot of interactions with government employees or scientists. Just putting a face to the names that they hear can help change their view of those people and educate them – tell them that we’re passionate about climate and energy. It’s important to meet people, make a friend, and talk about these things.”

There can be a lot of misunderstandings and questions about clean energy projects and what their impacts will be on communities. Dr. Chen believes it’s necessary for long-term buy-in, to keep strengthening our science communication and outreach efforts.

In both his personal and professional lives, Dr. Chen continues to be inspired to give back and make the world a better place for those that come after him. “I think it’s important to fight for the people in the next generation. If we can make it better for the people that come after us, then we’ve had some positive impact.”

Dr. Hannah Schlaerth, Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, Clearing the Air with the Clean Energy Corps

This series of interviews spotlights scientists working across the country to implement the Department of Energy’s massive efforts to transition the country to clean energy, and improve equity and address climate injustice along the way. The Federation’s clean energy workforce report discusses the challenges and opportunities associated with ramping up this dynamic, in-demand workforce. These interviews have been edited for length and do not necessarily reflect the views of the DOE.

Dr. Hannah Schlaerth’s passion for applied research on climate change was sparked in university, and after completing a PhD in environmental engineering, she joined the DOE’s Clean Energy Corps. Now Dr. Schlaerth, as a lifecycle emissions analyst for the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations, helps assess the air quality impacts of new clean energy technologies – directly forwarding the mission of industrial decarbonization across the country.

Intro to Environmental Science