Geolocating China’s Unprecedented Missile Launch: The Potential What, Where, How, and Why

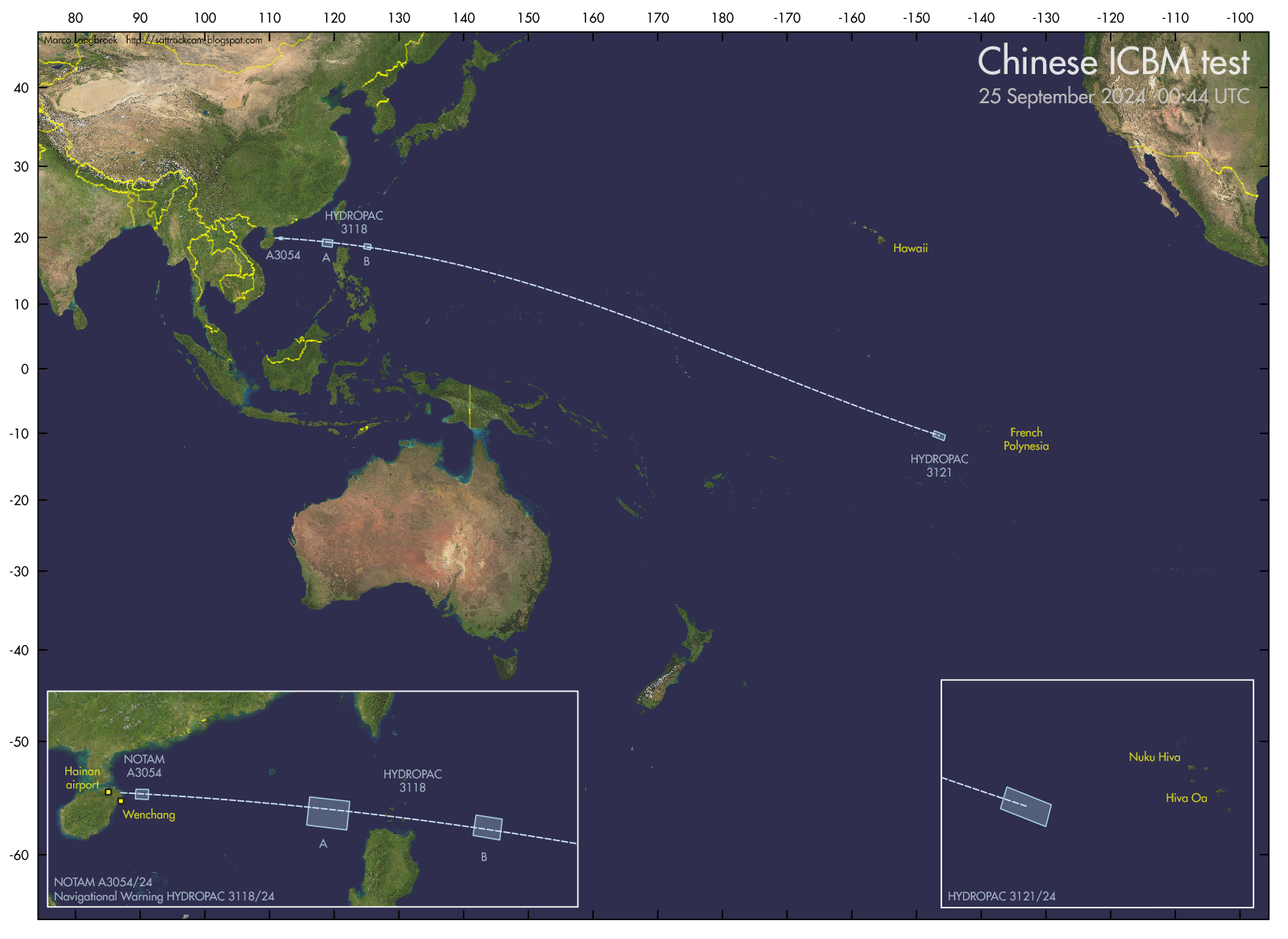

On September 25, 2024, the Chinese Ministry of National Defence announced that the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) had test-launched an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) into the South Pacific. The announcement stated that this was a “routine arrangement in [their] annual training plan.” However, the ICBM was launched from Hainan Island, an unusual location for this kind of missile. In addition, the reentry vehicle impacted in the South Pacific, an estimated 11,700 km away, marking the first time China had targeted the Pacific in a test since 1980 when it tested its first ICBM (the DF-5) at the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center.

This map, created by Dr. Marco Langbroek (@Marco_Langbroek on X), shows hazard areas from Navigational Warnings and a NOTAM with the reconstructed ballistic flight path. (source)

Given the unusual nature of this test launch and the lack of official information about the status of China’s nuclear forces, this event is an opportunity to further examine China’s nuclear posture and activities, including the type of missile, how it fits into China’s nuclear modernization, and where it was launched from.

What missile is it?

When news of the launch broke, navigational warnings and trajectory calculations indicated the missile was launched from northeast Hainan Island, a Chinese province in the South China Sea. This is not where China normally test-launches its ICBMs, and there is no ICBM brigade permanently deployed on the island. The location and the range of the missile indicated that it was a road-mobile missile launcher, either a DF-41 or DF-31A/AG type. In the days after the launch, several images surfaced with clues about the type of missile and its potential launch location.

An image of the missile lauch released by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army on September 25, 2024.

The first image, released by news outlets on September 25, showed features that made it clear that this was, in fact, a DF-31AG missile. The DF-31AG is a modernized version of China’s first solid-fuel road-mobile ICBM, the DF-31, which debuted in 2006. Since 2007, China has been supplementing and now completely replaced the initial DF-31 versions with the longer-range DF-31A. The DF-31A launcher had limited maneuverability, so in 2017, China first displayed the enhanced DF-31AG launcher. The DF-31AG will likely completely replace the DF-31A in the next few years.

The DF-31AG launcher is thought to carry the same missile as the DF-31A, but the 21-meter-long eight-axle HTF5980 transporter erector launcher has improved maneuverability and is thought to require less support. The single erector arm seen in the above image matches other images of the DF-31AG. The image seems to show that the launcher was partially covered by some sort of camouflage during the launch.

The DF-31AG uses a cold-launch method, meaning the missile is ejected from the canister using compressed gas or steam before the first-stage engine ignites. Unfortunately, this also means it is harder to geolocate the site of the launch because there are unlikely to be burn marks that would normally remain visible on the ground after hot-launching a missile.

How did the missile get there?

The nearest deployment of DF-31AG missiles is with the 632 Brigade located in Shaoyang in mainland China, around 800 km away. There is no confirmation that the missile came from this particular brigade, but the distance gives some perspective as to the process and amount of time it takes to bring a DF-31AG to Hainan Island.

To transport the mobile ICBM to Hainan, it was likely placed onto a railcar and brought to a port such as Yuehai Railway Beigang Wharf before being loaded onto a ship and transferred to Haikou port or a similar location at Hainan Island. From there, the missile was likely driven, along with the accompanying support vehicles, to a sheltered and protected area near the final launch location.

It remains unknown whether the missile was launched directly from the launch position itself, remotely from a local command post, or remotely from a centralized authority.

Where was the missile launched from?

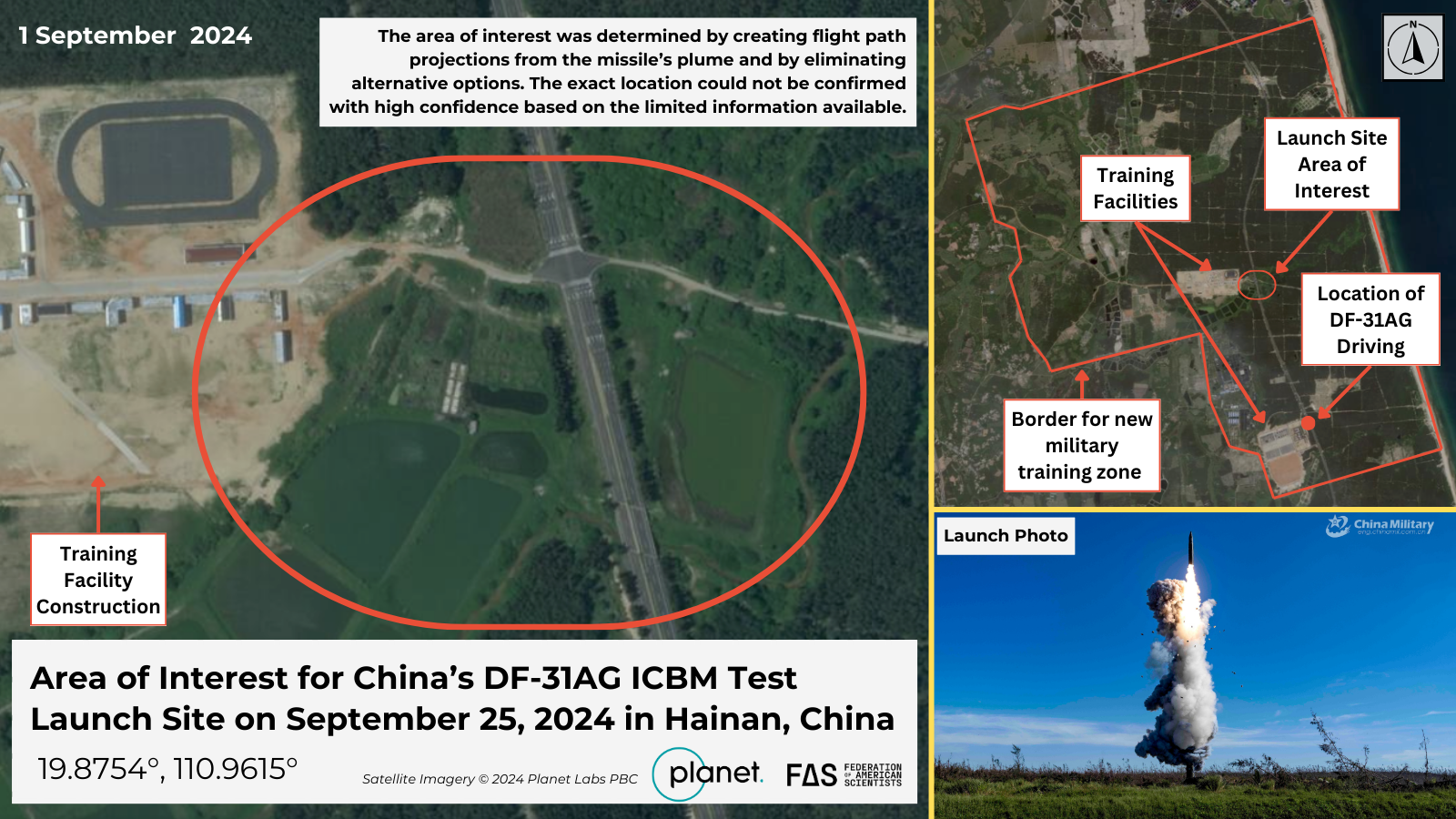

To find the precise location where the DF-31AG was launched on the island, we had to rely on the few photos and videos available to us (mostly captured by locals). To do this, we collaborated with analyst Ise Midori (@isekaimint on X), who carried out a complex analysis of the various launch videos to pinpoint the approximate launch location.

In the above image of the launch, one of the first noticeable features is the devastated vegetation, which matches what we would expect to see after typhoon Yagi impacted northeast Hainan in early September. There is also a small body of water barely visible at the bottom right of the image, which provides a clue when searching for the launch location.

After analyzing the available images, photos, and videos, Midori determined the general area where the launch likely occurred to be in Wenchang, Hainan. While we are unable to determine the exact location with high confidence due to a lack of clearly identifiable signatures, we expect it to be within the area of interest indicated below, potentially at the highway intersection.

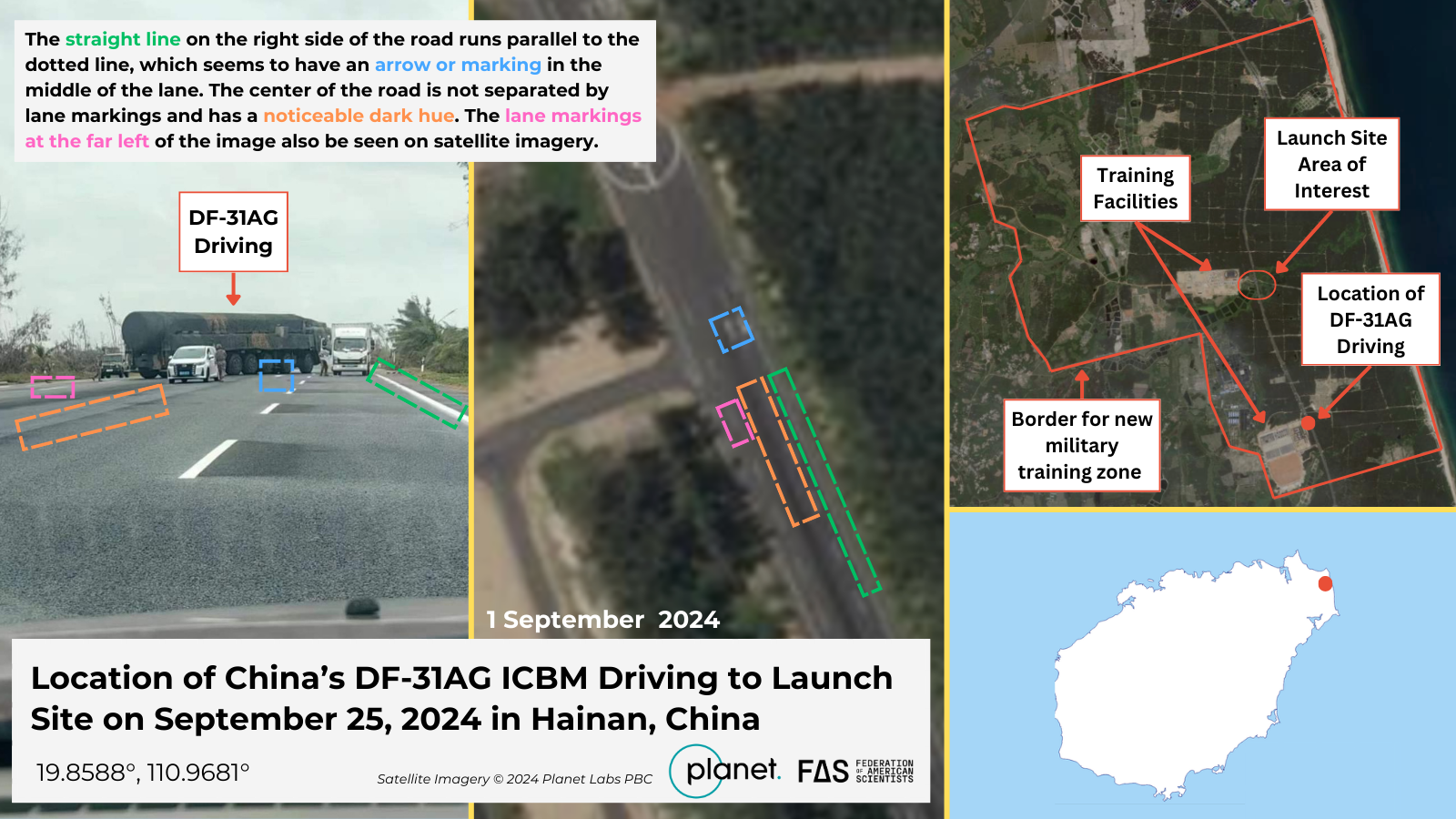

Meanwhile, the image below began circulating on social media shortly after the launch. The image reportedly captures the DF-31AG as it was driving to its launch position, although the cloud coverage does not match that from the photo of the launch and could have been taken hours beforehand.

An image of the DF-31AG missile driving on Hainan Island that circulated on social media shortly after the launch.

After observing the road markings and vegetation in the image, satellite imagery from Planet Labs PBC revealed a unique road that matched these signatures. This road is also only 1.9 km away from the launch location area of interest, increasing confidence that the launch occurred at or near this area.

Notably, both the launch area of interest and the location of the DF-31AG on the road are within the boundaries of what seems to be a new military training zone constructed in recent years. This also helps increase confidence in the launch area of interest and highlights this area as important for future observation.

Why here, and why now?

While China has not test-launched an ICBM into the Pacific in over four decades (it normally test launches the missiles in a very high apogee within its borders), it is not unusual for China – or other countries for that matter – to test-launch their nuclear-capable systems. It is interesting, however, to consider why China may have chosen to launch from Hainan Island instead of somewhere that is operationally representative or perhaps easier to travel to on the mainland coast. Nevertheless, the location allows China to fly the missile at full range without dropping missile stages on the ground or overflying other countries. It is unknown whether China will test-launch more ICBMs from Hainan Island in the future.

These types of tests also take months of extensive planning and coordination. Thus, the launch was likely motivated by broader political factors, not in response to particular recent events. Tong Zhao, Senior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, points out that this test was crucial for the PLARF to reestablish its internal and external credibility following corruption scandals and unprecedented leadership shifts. Additionally, reports of issues with the quality of certain missiles likely prompted a desire to reestablish recognition of operational competence.

Further, because the PLARF conducted the test launch as part of a “military drill” rather than a technological development program, it likely aims to convey military prowess and combat readiness. Conducting an ICBM test over the ocean also likely reflects China’s ambition to solidify its international status as a major nuclear power since the United States also regularly tests its ICBMs over the open ocean.

Notably, the Pentagon confirmed they received advanced notice of China’s test launch, which potentially sets a precedent for pre-launch notification and could leave room for further communication on risk reduction measures. Moving forward, it will be interesting to see if China begins to routinely conduct these kinds of tests beyond its borders and if it continues to provide pre-launch notification to relevant states. The new DF-41 has yet to be test-flown at full range in a realistic trajectory.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the Carnegie Corporation of New York, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2024: A “Significant Expansion”

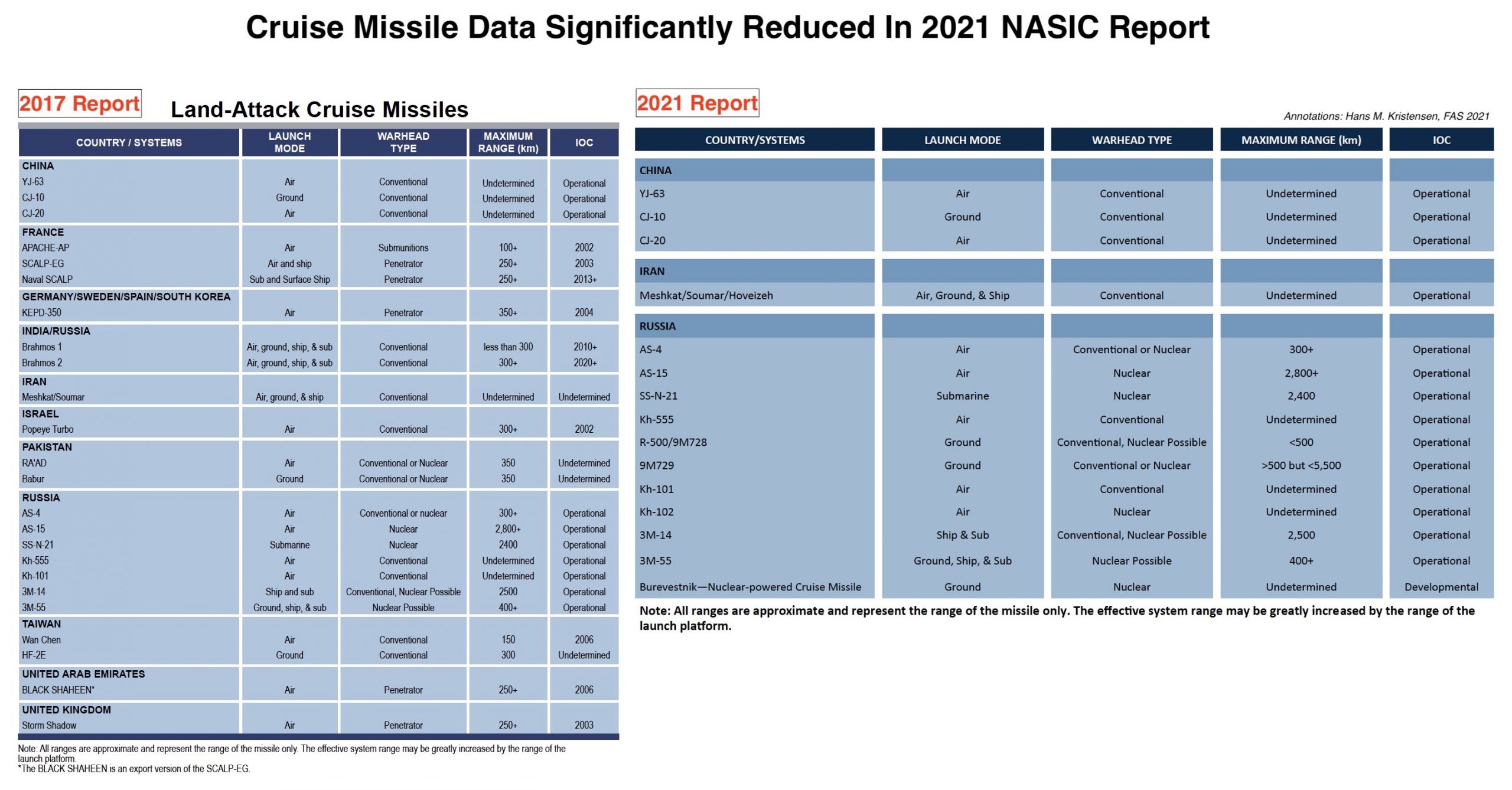

The Federation of American Scientists’ Nuclear Information Project, a component of the Federation’s Global Risk program, today released its latest assessment of China’s growing nuclear arsenal: the 2024 Nuclear Notebook on Chinese Nuclear Forces. The 24-page report, published in the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, includes details on China’s nuclear weapons arsenal, including types of weapons, delivery vehicles, operations, and, importantly, questions that can help determine the reliability and accuracy of projections about the future growth of China’s nuclear capabilities.

The Notebook comes at a critical time for U.S. analysis and policy debates regarding China’s nuclear forces and the appropriate U.S. and allied response. In October 2023, the Pentagon released its annual report to Congress on Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. This report preceded the release of both the Strategic Posture Commission report and the State Department’s International Security Advisory Board report on Nuclear Deterrence in a World of Nuclear Multipolarity. Within the U.S. government, military, and national security community, analysts are evaluating the implications of China’s growing nuclear force for nuclear deterrence, global stability, and U.S. security commitments in East Asia, Europe, and beyond.

What about the DOD’s numbers?

Meanwhile, the 2024 Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces comes on the heels of a news report from Bloomberg that suggest corruption in China’s military procurement program may have resulted in the production or delivery of nuclear-tipped missiles and missile silos that do not operate properly. Reports about China’s corruption are not new, but the potential impact on the unprecedentedly rapid projected growth of China’s nuclear forces has not been previously reported, nor has it been reflected in reports, testimony, or statements by top Administration, defense, or intelligence officials.

Given the potential implications of the Bloomberg report, FAS sent a letter to Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin asking whether the reported intelligence about the reliability of China’s missile force was known to the authors of DOD reports on China’s nuclear program and, if so, why they were not reflected in reports sent to Congress. As one of the most authoritative non-governmental sources on global nuclear forces, FAS has a unique interest in ensuring that its reports are objective and reflect the full extent of government and non-governmental expert understanding of nuclear arsenals worldwide.

2024 Nuclear Notebook: Key findings on China’s nuclear forces

Analyzing and estimating China’s nuclear forces is challenging, particularly given the relative lack of state-originating data and the tight control of messaging surrounding the country’s nuclear arsenal and doctrine. Like most other nuclear-armed states, China has never publicly disclosed the size of its nuclear arsenal or much of the infrastructure that supports it. The analyses and estimates made in the Nuclear Notebook are derived from a combination of open sources, including (1) state-originating data (e.g. government statements, declassified documents, budgetary information, military parades, and treaty disclosure data), (2) non-state-originating data (e.g. media reports, think tank analyses, and industry publications), and (3) commercial satellite imagery. From this information, FAS has tracked the significant expansion of China’s ongoing nuclear modernization program. Key findings from the 2024 FAS assessment on Chinese nuclear forces include:

- China’s nuclear expansion is among the largest and most rapid modernization campaigns of the nine nuclear-armed states.

- FAS estimates that China has produced a stockpile of approximately 500 nuclear warheads, with 440 warheads available for delivery by land-based ballistic missiles, sea-based ballistic missiles, and bombers.

- The latest Pentagon projection appears to apply the same growth rate of new warheads added to the stockpile between 2019 and 2021 to the subsequent years until 2035. FAS assesses that this projected growth trajectory is feasible but depends significantly upon many uncertain factors and assumptions.

- China has continued to develop its three new missile silo fields for solid-fuel intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), expand the construction of new silos for its liquid-fuel DF-5 ICBMs, and has been developing new variants of ICBMs and advanced strategic delivery systems.

- China has further expanded its dual-capable DF-26 intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) force, which appears to have completely replaced the medium-range DF-21 in the nuclear role.

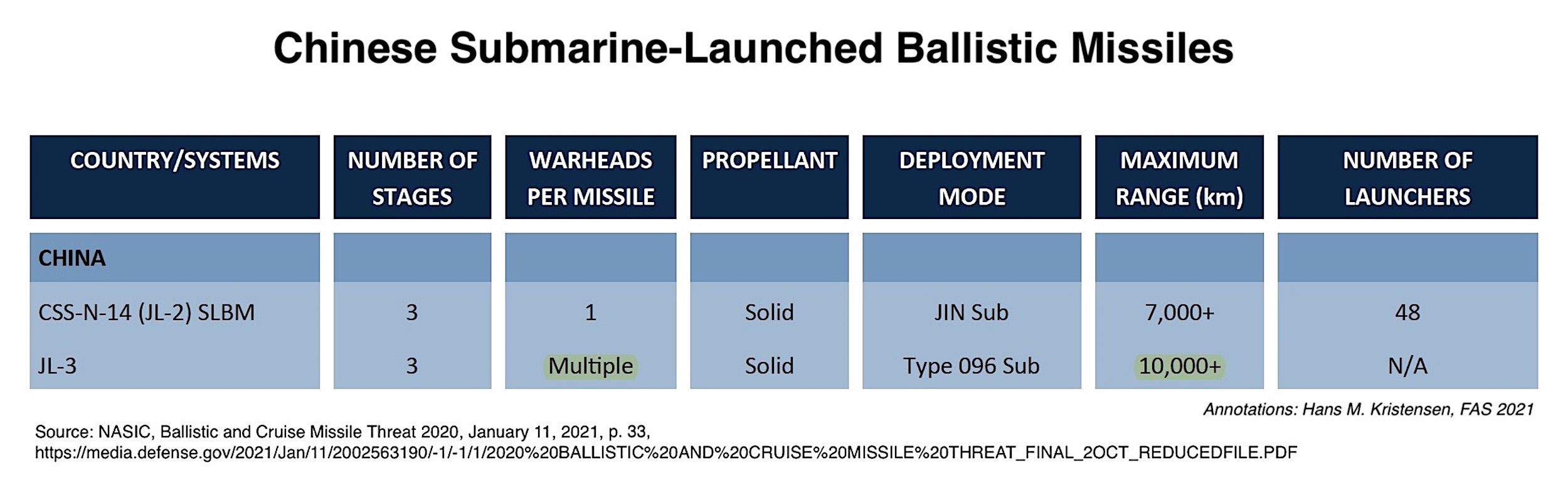

- China has been refitting its Type 094 ballistic missile submarines with the longer-range JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile (SLBM).

- China has recently reassigned an operational nuclear mission to its bombers and is developing an air-launched ballistic missile (ALBM) that might have nuclear capability.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

What Did the DOD Know About Chinese Missiles in the Latest PRC Nuclear Capabilities Report?

The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) sent a letter on January 9, 2024, to Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin regarding the Department of Defense’s recent publications on China’s nuclear arsenal. These publications are a primary source of information for the public and are widely referenced by the U.S. government, military, and national security community when discussing the scope and implications of China’s nuclear modernization.

In early January 2024, Bloomberg published a press report suggesting U.S. intelligence assessments have evidence that the reliability of China’s new nuclear missiles may be undermined by corruption within China’s People’s Liberation Army Rocket Forces. These assessments cited examples of significant flaws in China’s missile program, including missile silo lids that may not be fully operational and missile silo fields – some of which were originally discovered by FAS researchers – that may have stages or components filled with water instead of fuel. If true, these flaws would compromise missile operations, calling into question China’s nuclear force readiness and overall capabilities.

FAS noted that “For over 70 years, FAS has worked to ensure there is a vigorous and informed public debate over nuclear weapons and security. As the world’s leading non-governmental source of information about global nuclear arsenals, ensuring the public has reliable and accurate information about the scale, role and capabilities of nuclear forces in other countries is critical to that debate.”

The letter sent by FAS asks whether these assessments were known to the authors of DOD reports to Congress who expressed concern about the record pace of China’s nuclear deployments and production. If so, the letter asks why such assessments were not included in those DOD reports or in other testimony and statements by DOD officials and military officers.

Finally, the letter notes FAS’ historical interest in ensuring U.S. government assessments about nuclear forces are complete and unbiased.

We have reproduced the text of the letter below. You can also download it as a PDF using the button on the top left of this post.

Secretary Lloyd Austin

The Department of Defense

Dear Mr. Secretary:

On January 6th, 2024, Bloomberg News reported that U.S. intelligence assessments called into question the reliability and functionality of China’s growing arsenal of long-range nuclear-armed missiles. The article mentioned that some silo doors on ICBMs may function properly, and ICBM stages or components may have been filled with water. None of this information has been included or publicly cited in reports or speeches by U.S. Defense Department officials or military officers, even as public concern about the pace of China’s reported nuclear buildup has increasingly influenced U.S. thinking about both deterrence, alliance management, and nuclear weapons procurement.

We would not expect, or want the USG Government to comment on sensitive intelligence. However, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) would like to know if such assessments exist and, if so, whether you and the authors of the U.S. Department of Defense report, “Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China,” published on October 19th, 2023, were aware of these assessments prior to its publication. If such assessments exist, and if the authors of the report were aware of their existence, we would also ask why some reference to these indicators were not included in the report and testimony related to China’s reported nuclear build-up.

The growth of China’s nuclear weapons capabilities has become a serious question and concern for the United States, both within the Government and the public, and among U.S. allies in East Asia and Europe. The growth and reported capabilities of China’s nuclear arsenal are being used increasingly to justify current and potentially additional increases in U.S. nuclear capabilities and spending, and to support expanding military and even nuclear collaboration with U.S. allies in East Asia. The accuracy of Department of Defense documents with regard to China’s nuclear capabilities are central to informing these debates in Congress as well as among security experts and the broader public, and thus, ensuring they are accurate and complete is essential. As you are no doubt aware, the Soviet Military Report series produced by the Department of Defense during the Cold War was found after the fact to have systematically overinflated Soviet capabilities. It would be appropriate for the Defense Department to remember past trends and ensure lessons learned are incorporated into ongoing public documents about countries that threaten U.S. and U.S. allied security.

FAS also has a direct interest in ensuring that U.S. Government reports on nuclear capabilities are as accurate and balanced as possible, given that FAS experts remain a central resource for the global public about nuclear capabilities throughout the world. While the FAS does not take U.S. estimates verbatim, we do use them as source material and believe the statements of the U.S. should be as accurate and reliable as possible. As such, FAS has a particular interest in ensuring that its work is not mistakenly or deliberately biassed by government sources that include worst-case estimates or that fail to provide important assessments about the reliability, pace, and operational status of key systems. Having engaged in key debates on nuclear policy for over 70 years, FAS has a strong institutional basis for wanting to use reliable information from governments, but at the same time, keenly remembers periods between the 1960-1980s when the Department of Defense produced annual assessments of Soviet military capabilities that widely overinflated conventional and nuclear capabilities, which may have ultimately contributed to unnecessary arms investments in the United States.

As such, FAS would kindly request that your department make clear:

- Was the Department of Defense aware of intelligence before the publication of Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China that Chinese procurement flaws may have led to missile silo doors that are not operational, or that missiles that were filled with water and not fuel?

- Does the Department intend to either amend or withdraw the current report to Congress and update it with a broader reliance on information––not only about the growth of China’s nuclear capabilities but also information that may acknowledge the possible unreliability of such systems so that it may be factored into the public debate in Congress and elsewhere?

- Were US Strategic Command or US Indo-Pacific Command aware in 2023 of the information reported on January 6th, 2024 that China’s siloed ICBMs may be less than fully reliable? If so, why was that information not included in speeches and publications?

- Lastly, is the Department considering changes to how its reports are produced, reviewed, and promoted to ensure not only that China’s growing capabilities are included but that they also information that might inform a more complete assessment of the nature, scale, and pace of China’s nuclear capabilities might pose to the U.S. and our allies?

For over 70 years, the Federation of American Scientists has played a key role in supporting public debate over issues related to security, technology, and nuclear weapons. We appreciate your interest in ensuring the public engages in a sustained discourse over appropriate defense investments and strategy to secure American and allied security in the coming decades. Your attention to this matter is greatly appreciated.

Sincerely,

Jon Wolfsthal

Director, Global Risk

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

Strategic Posture Commission Report Calls for Broad Nuclear Buildup

On October 12th, the Strategic Posture Commission released its long-awaited report on U.S. nuclear policy and strategic stability. The 12-member Commission was hand-picked by Congress in 2022 to conduct a threat assessment, consider alterations to U.S. force posture, and provide recommendations.

In contrast to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, the Congressionally-mandated Strategic Posture Commission report is a full-throated embrace of a U.S. nuclear build-up.

It includes recommendations for the United States to prepare to increase its number of deployed warheads, as well as increasing its production of bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, ballistic missile submarines, non-strategic nuclear forces, and warhead production capacity. It also calls for the United States to deploy multiple warheads on land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and consider adding road-mobile ICBMs to its arsenal.

The only thing that appears to have prevented the Commission from recommending an immediate increase of the U.S. nuclear weapons stockpile is that the weapons production complex currently does not have the capacity to do so.

The Commission’s embrace of a U.S. nuclear buildup ignores the consequences of a likely arms race with Russia and China (in fact, the Commission doesn’t even consider this or suggest other steps than a buildup to try to address the problem). If the United States responds to the Chinese buildup by increasing its own deployed warheads and launchers, Russia would most likely respond by increasing its deployed warheads and launchers. That would increase the nuclear threat against the United States and its allies. China, who has already decided that it needs more nuclear weapons to stand up to the existing U.S. force level (and those of Russia and India), might well respond to the U.S and Russian increases by increasing its own arsenal even further. That would put the United States back to where it started, feeling insufficient and facing increased nuclear threats.

Framing and context

The Commission’s report is generally framed around the prospect of Russian and Chinese strategic military cooperation against the United States. The Commission cautions against “dismissing the possibility of opportunistic or simultaneous two-peer aggression because it may seem improbable,” and notes that “not addressing it in U.S. strategy and strategic posture, could have the perverse effect of making such aggression more likely.” The Commission does not acknowledge, however, that building up new capabilities to address this highly remote possibility would likely kick the arms race into an even higher gear.

The report acknowledges that Russia and China are in the midst of large-scale modernization programs, and in the case of China, significant increases to its nuclear stockpile. This accords with our own assessments of both countries’ nuclear programs. However, the report’s authors suggest that these changes fundamentally call into question the United States’ assured retaliatory capabilities, and state that “the current U.S. strategic posture will be insufficient to achieve the objectives of U.S. defense strategy in the future….”

The Commission appears to base this conclusion, as well as its nuclear strategy and force structure recommendations, squarely on numerically-focused counterforce thinking: if China increases its posture by fielding more weapons, that automatically means the United States needs more weapons to “[a]ddress the larger number of targets….” However, the survivability of the US ballistic missile submarines should insulate the United States against needing to subscribe to this kind of thinking.

In 2012, a joint DOD/DNI report acknowledged that because of the US submarine force, Russia would not achieve any military advantage against the United States by significantly increasing the size of its deployed nuclear forces. In that 2012 study, both departments concluded that the “Russian Federation…would not be able to achieve a militarily significant advantage by any plausible expansion of its strategic nuclear forces, even in a cheating or breakout scenario under the New START Treaty, primarily because of the inherent survivability of the planned U.S. Strategic force structure, particularly the OHIO-class ballistic missile submarines, a number of which are at sea at any given time.” [Emphasis added.] Why would this logic not apply to China as well? Although China’s nuclear arsenal is undoubtedly growing, why would it fundamentally alter the nature of the United States’ assured retaliatory capability while the United States is confident in the survivability of its SSBNs?

In this context, it is worth reiterating the words of Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin at the U.S. Strategic Command Change of Command Ceremony: “We all understand that nuclear deterrence isn’t just a numbers game. In fact, that sort of thinking can spur a dangerous arms race…deterrence has never been just about the numbers, the weapons, or the platforms.”

Force structure

Although the report says the Commission “avoided making specific force structure recommendations” in order to “leave specific material solution decisions to the Executive Branch and Congress,” the list of “identified capabilities beyond the existing program of record (POR) that will be needed” leaves little doubt about what the Commission believes those force structure decisions should be.

Strategic posture alterations

The Commission concludes that the United States “must act now to pursue additional measures and programs…beyond the planned modernization of strategic delivery vehicles and warheads may include either or both qualitative and quantitative adjustments in the U.S. strategic posture.”

Specifically, the Commission recommends that the United States should pursue the following modifications to its strategic nuclear force posture “with urgency:” [our context and commentary added below]

- Prepare to upload some or all of the nation’s hedge warheads; [these warheads are currently in storage; increasing deployed warheads above 1,550 is prohibited by the New START treaty (which expires in early-2026) and would likely cause Russia to also increase its deployed warheads.]

- Plan to deploy the Sentinel ICBM in a MIRVed configuration; [the Sentinel appears to be capable of carrying two MIRV but current plan calls for each missile to be deployed with just a single warhead]

- Increase the planned number of deployed Long-Range Standoff Weapons; [the Air Force currently has just over 500 ALCMs and plans to build 1,087 LRSOs (including test-flight missiles), each of which costs approximately $13 million]

- Increase the planned number of B-21 bombers and the tankers an expanded force would require; [the Air Force has said that it plans to purchase at least 100 B-21s]

- Increase the planned production of Columbia SSBNs and their Trident ballistic missile systems, and accelerate development and deployment of D5LE2; [the Navy currently plans to build 12 Columbia-class SSBNs and an increase would not happen until after the 12th SSBN is completed in the 2040s]

- Pursue the feasibility of fielding some portion of the future ICBM force in a road mobile configuration; [historically, any efforts to deploy road-mobile ICBMs in the United States have been unsuccessful]

- Accelerate efforts to develop advanced countermeasures to adversary IAMD; and

- Initiate planning and preparations for a portion of the future bomber fleet to be on continuous alert status, in time for the B-21 Full Operational Capability (FOC) date.” [Bombers currently regularly practice loading nuclear weapons as part of rapid-takeoff exercises. Returning bombers to alert would revert the decision by President H.W. Bush in 1991 to take bombers off alert. In 2021, the Air Force’s Deputy Chief of Staff for Strategic Deterrence and Nuclear Integration stated that keeping the bomber fleet on continuous alert would exhaust the force and could not be done indefinitely]

Nonstrategic posture alterations

The Commission appears to want the United States to bolster its non-strategic nuclear forces in Europe, and begin to deploy non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific theater: “Additional U.S. theater nuclear capabilities will be necessary in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific regions to deter adversary nuclear use and offset local conventional superiority. These additional theater capabilities will need to be deployable, survivable, and variable in their available yield options.” Although the Commission does not explicitly recommend fielding either ground-launched theater nuclear capabilities or a nuclear sea-launched cruise missile for the Navy, it seems clear that these capabilities would be part of the Commission’s logic.

The United States used to deploy large numbers of non-strategic nuclear weapons in the Indo-Pacific region during the Cold War, but those weapons were withdrawn in the early 1990s and later dismantled as U.S. military planning shifted to rely more on advanced conventional weapons for limited theater options. Despite the removal of certain types of theater nuclear weapons after the Cold War, today the President maintains a wide range of nuclear response options designed to deter Russian and Chinese limited nuclear use in both regions––including capabilities with low or variable yields. In addition to ballistic missile submarines and nuclear-capable bombers operating in both regions, the U.S. Air Force has non-strategic B61 nuclear bombs for dual-capable aircraft that are intended for operations in both regions if it becomes necessary. The Navy now also has a low-yield warhead on its SSBNs––the W76-2––that was fielded specifically to provide the President with more options to deter limited scenarios in those regions. It is unclear why these existing options, as well as several additional capabilities already under development––including the incoming Long-Range Stand-Off Weapon––would be insufficient for maintaining regional deterrence.

The Commission specifically recommends that the United States should “urgently” modify its nuclear posture to “[p]rovide the President a range of militarily effective nuclear response options to deter or counter Russian or Chinese limited nuclear use in theater.” Although current plans already provide the President with such options, the Commission “recommends the following U.S. theater nuclear force posture modifications:

Develop and deploy theater nuclear delivery systems that have some or all of the following attributes: [our context and commentary added below]

- Forward-deployed or deployable in the European and Asia-Pacific theaters [The United States already has dual-capable fighters and B61 bombs earmarked for operations in the Asia-Pacific theaters, backed up by bombers with long-range cruise missiles];

- Survivable against preemptive attack without force generation day-to-day;

- A range of explosive yield options, including low yield [US nuclear forces earmarked for regional options already have a wide range of low-yield options];

- Capable of penetrating advanced IAMD with high confidence [F-35A dual-capable aircraft, the B-21 bomber, and air-launched cruise missiles are already being developed with enhanced penetration capabilities]; and

- Operationally relevant weapon delivery timeline (promptness) [the US recently fielded the W76-2 warhead on SSBNs to provide prompt theater capability in limited scenarios and is developing new prompt conventional missiles].”

Unlike U.S. low-yield theater nuclear weapons, the Commission warns that China’s development of “theater-range low-yield weapons may reduce China’s threshold for using nuclear weapons.” Presumably, the same would be true for the United States threshold if it followed the Commission’s recommendation to increase deployed (or deployable) non-strategic nuclear weapons with low-yield capabilities in the Indo-Pacific theater.

Strategy

Overall, the Commission suggests that current U.S. nuclear strategy is basically sound, but just needs to be backed up with additional weapons and industrial capacity. However, by not including recommendations to modify presidential nuclear employment guidance –– or even considering such an adjustment, which could reshape U.S. force posture to allow for decreased emphasis on counterforce targeting –– the Commission has limited its own flexibility to recommend any options other than simply adding more weapons.

Three scholars recently proposed a revised nuclear strategy that they concluded would reduce weapons requirements yet still be sufficient to adequately deter Russia and China. The central premise of reducing the counterforce focus is similar to a study that we published in 2009. In contrast, the Commission appears to have assumed an unchanged nuclear strategy and instead focused intensely on weapons and numbers.

The Commission report does not explain how it gets to the specific nuclear arms additions it says are needed. It only provides generic descriptions of nuclear strategy and lists of Chinese and Russian increases. The reason this translates into a recommendation to increase the US nuclear arsenal appears to be that the list of target categories that the Commission believes need to be targeted is very broad: “this means holding at risk key elements of their leadership, the security structure maintaining the leadership in power, their nuclear and conventional forces, and their war supporting industry.”

This numerical focus also ignores years of adjustments made to nuclear planning intended to avoid excessive nuclear force levels and increase flexibility. When asked in 2017 whether the US needed new nuclear capabilities for limited scenarios, then STRATCOM commander General John Hyten responded:

“[W]e actually have very flexible options in our plans. So if something bad happens in the world and there’s a response and I’m on the phone with the Secretary of Defense and the President and the entire staff, …I actually have a series of very flexible options from conventional all the way up to large-scale nuke that I can advise the President on to give him options on what he would want to do… So I’m very comfortable today with the flexibility of our response options… And the reason I was surprised when I got to STRATCOM about the flexibility, is because the last time I executed or was involved in the execution of the nuclear plan was about 20 years ago and there was no flexibility in the plan. It was big, it was huge, it was massively destructive, and that’s all there. We now have conventional responses all the way up to the nuclear responses, and I think that’s a very healthy thing.”

While advocating integrated deterrence and a “whole of government” approach, the Commission nonetheless sets up an artificial dichotomy between conventional and nuclear capabilities: “The objectives of U.S. strategy must include effective deterrence and defeat of simultaneous Russian and Chinese aggression in Europe and Asia using conventional forces. If the United States and its Allies and partners do not field sufficient conventional forces to achieve this objective, U.S. strategy would need to be altered to increase reliance on nuclear weapons to deter or counter opportunistic or collaborative aggression in the other theater.”

Arms control

The Commission recommends subjugating nuclear arms control to the nuclear build-up: “The Commission recommends that a strategy to address the two-nuclear-peer threat environment be a prerequisite for developing U.S. nuclear arms control limits for the 2027-2035 timeframe. The Commission recommends that once a strategy and its related force requirements are established, the U.S. government determine whether and how nuclear arms control limits continue to enhance U.S. security.”

Put another way, this constitutes a recommendation to participate in an arms race, and then figure out how to control those same arms later.

The Commission report does acknowledge the importance of arms control, and notes that “[t]he ideal scenario for the United States would be a trilateral agreement that could effectively verify and limit all Russian, Chinese, and U.S. nuclear warheads and delivery systems, while retaining sufficient U.S. nuclear forces to meet security objectives and hedge against potential violations of the agreement.” (p.85) However, the prospect of this “ideal scenario” coming true would become increasingly unlikely if the United States significantly built up its nuclear forces as the Commission recommends.

Capacity and budget

The Commission recommends an overhaul and expansion of the nuclear weapons design and production capacity. That includes full funding of all NNSA recapitalization efforts, including pit production plans, even though the Government Accountability Office has warned that the program faces serious challenges and budget uncertainties. The Commission appears to brush aside concerns about the proposed pit production program.

Overall, the report does not seem to acknowledge any limits to defense spending. Amid all of the Commission’s recommendations to increase the number of strategic and tactical nuclear systems, there is almost no mention of cost in the entire report. Fulfilling all of these recommendations would require a significant amount of money, and that money would have to come from somewhere.

For example, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that developing the SLCM-N alone would cost an estimated $10 billion until 2030, not to mention another $7 billion for other tactical nuclear weapons and delivery systems. The amount of money it would take to field new systems, in addition to addressing other vital concerns such as IAMD, means funding would necessarily be cut from other budget priorities.

The true costs of these systems are not only the significant funds spent to acquire them, but also the fact that prioritizing these systems necessarily means deprioritizing other domestic or foreign policy initiatives that could do more to increase US security.

Implications for U.S. Nuclear Posture

The Strategic Posture Commission report is, in effect, a congressionally-mandated rebuttal to the Biden administration’s Nuclear Posture Review, which many in Congress have critiqued for not being hawkish enough. The report does not describe in detail its methodology for how it arrives at its force buildup recommendations, and includes several claims and assumptions about nuclear strategy that have been critiqued and called into question by recent scholarship. In some respects, it reads more like an industry report than a Congressionally-mandated study.

While the timing of the report means that it is unlikely to have a significant impact on this year’s budget cycle, it will certainly play a critical role in justifying increases to the nuclear budget for years to come.

From our perspective, the recommendations included in the Commission report are likely to exacerbate the arms race, further constrict the window for engaging with Russia and China on arms control, and redirect funding away from more proximate priorities. At the very least, before embarking on this overambitious wish list the United States must address any outstanding recommendations from the Government Accountability Office to fix its planning and budgeting processes, otherwise it risks overloading the assembly line even more.

In addition, the United States could consider how modified presidential employment guidance might enable a posture that relies on fewer nuclear weapons, and adjust accordingly.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, and individual donors.

STRATCOM Says China Has More ICBM Launchers Than The United States – We Have Questions

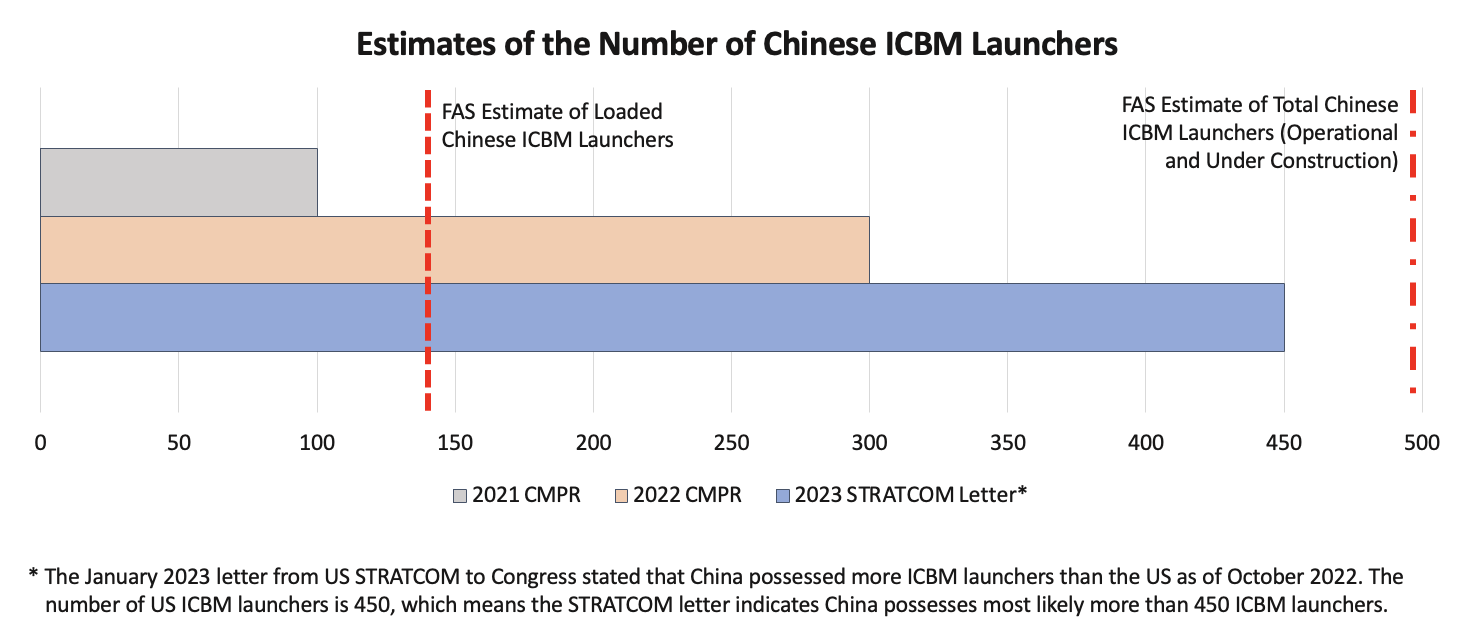

In early-February 2023, the Wall Street Journal reported that U.S. Strategic Command (STRATCOM) had informed Congress that China now has more launchers for Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) than the United States. The report is the latest in a serious of revelations over the past four years about China’s growing nuclear weapons arsenal and the deepening strategic competition between the world’s nuclear weapon states. It is important to monitor China’s developments to understand what it means for Chinese nuclear strategy and intensions, but it is also important to avoid overreactions and exaggerations.

First, a reminder about what the STRATCOM letter says and does not say. It does not say that China has more ICBMs or warheads on them than the United States, or that the United States is at an overall disadvantage. The letter has three findings (in that order):

- The number of ICBMs in the active inventory of China has not exceeded the number of ICBMs in the active inventory of the United States.

- The number of nuclear warheads equipped on such missiles of China has not exceeded the number of nuclear warheads equipped on such missiles of the United States.

- The number of land-based fixed and mobile ICBM launchers in China exceeds the number of ICBM launchers in the United States.

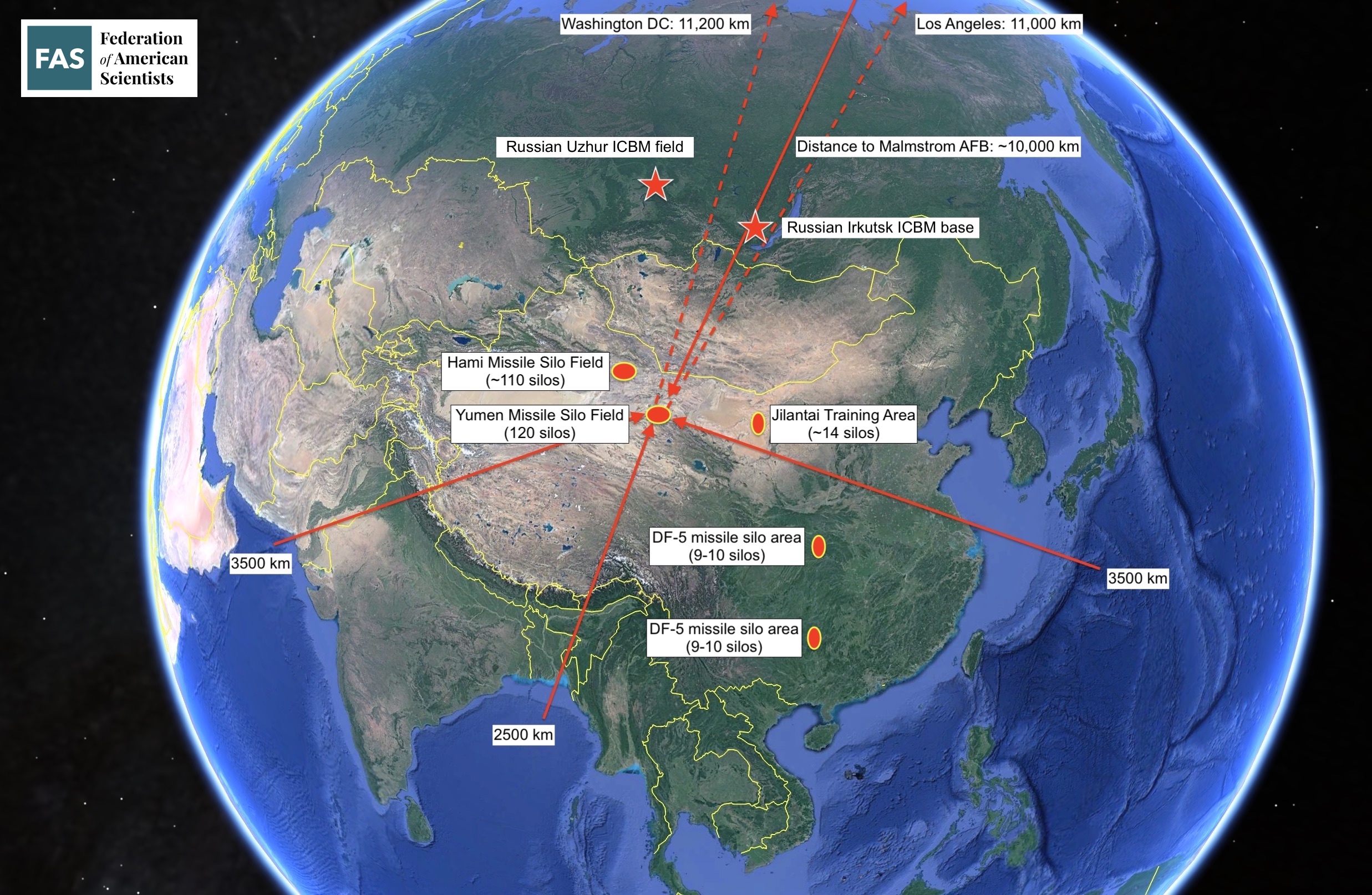

It is already well-known that China is building several hundred new missile silos. We documented many of them (see here, here and here), as did other analysts (here and here). It was expected that sooner or later some of them would be completed and bring China’s total number of ICBM launchers (silo and road-mobile) above the number of US ICBM launchers. That is what STRATCOM says has now happened.

STRATCOM ICBM Counting

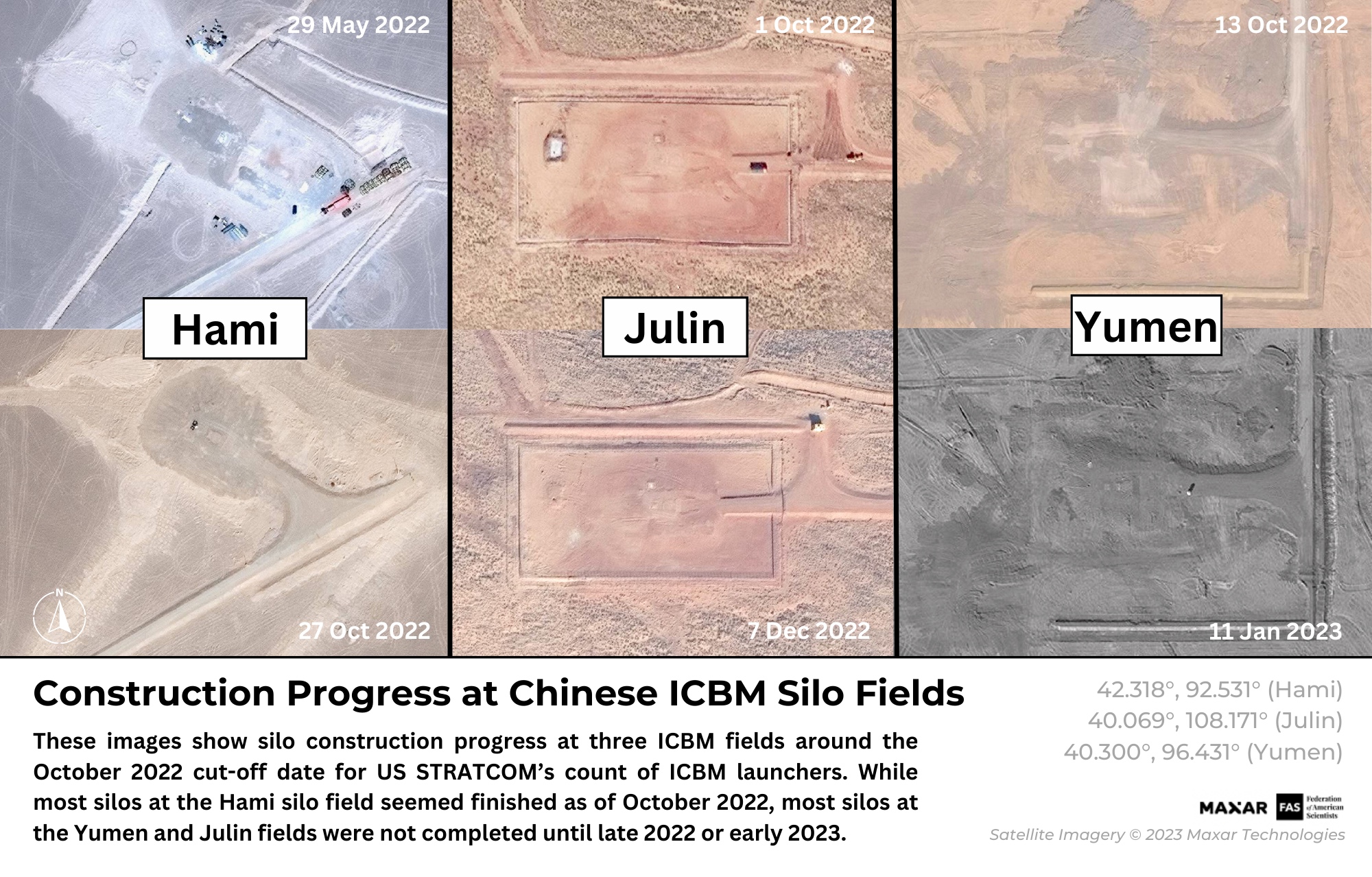

The number of Chinese ICBM launchers included in the STRATCOM report to Congress was counted at a cut-off date of October 2022. It is unclear precisely how STRATCOM counts the Chinese silos, but the number appears to include hundreds of silos that were not yet operational with missiles at the time. So, at what point in its construction process did STRATCOM include a silo as part of the count? Does it have to be completely finished with everything ready except a loaded missile?

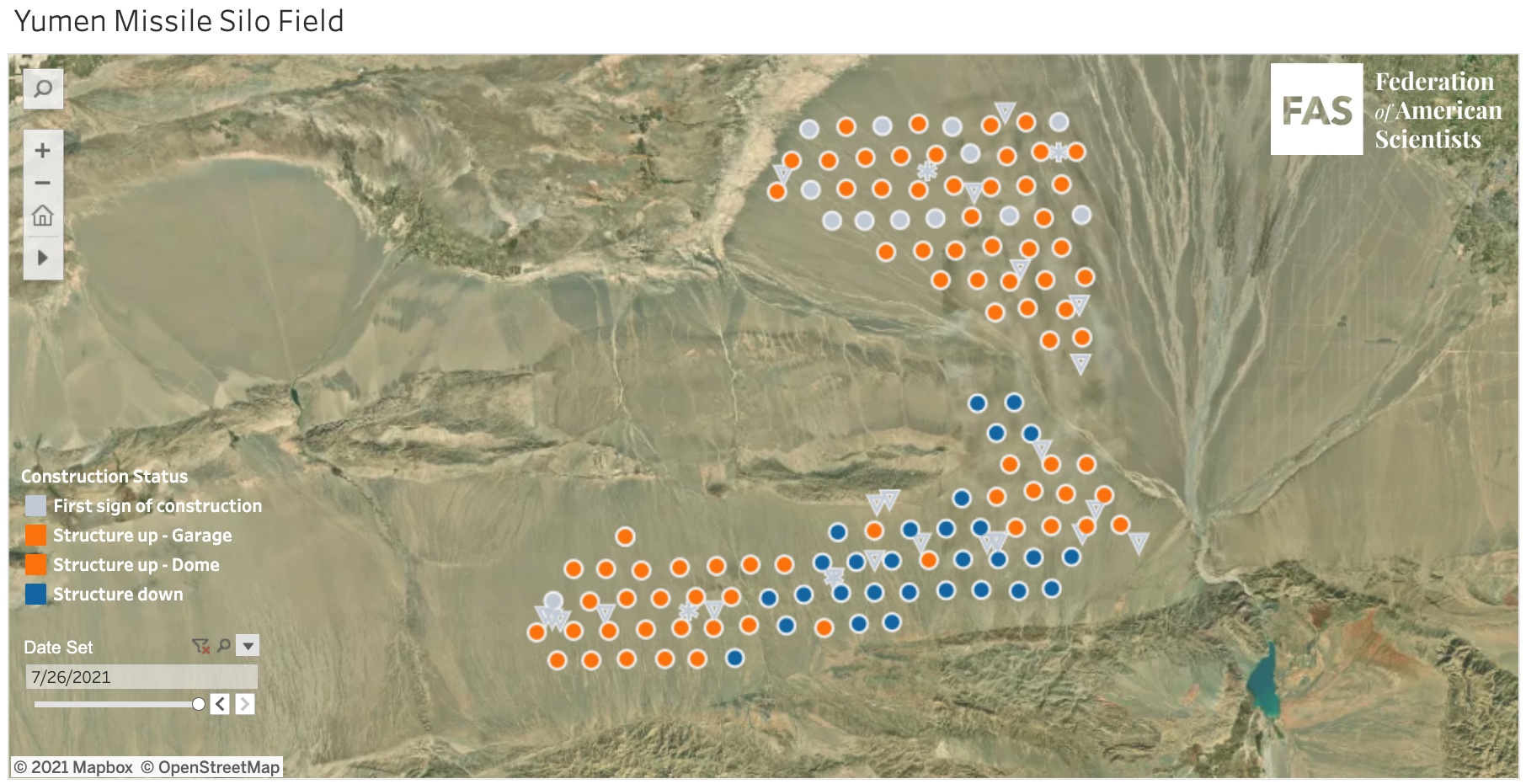

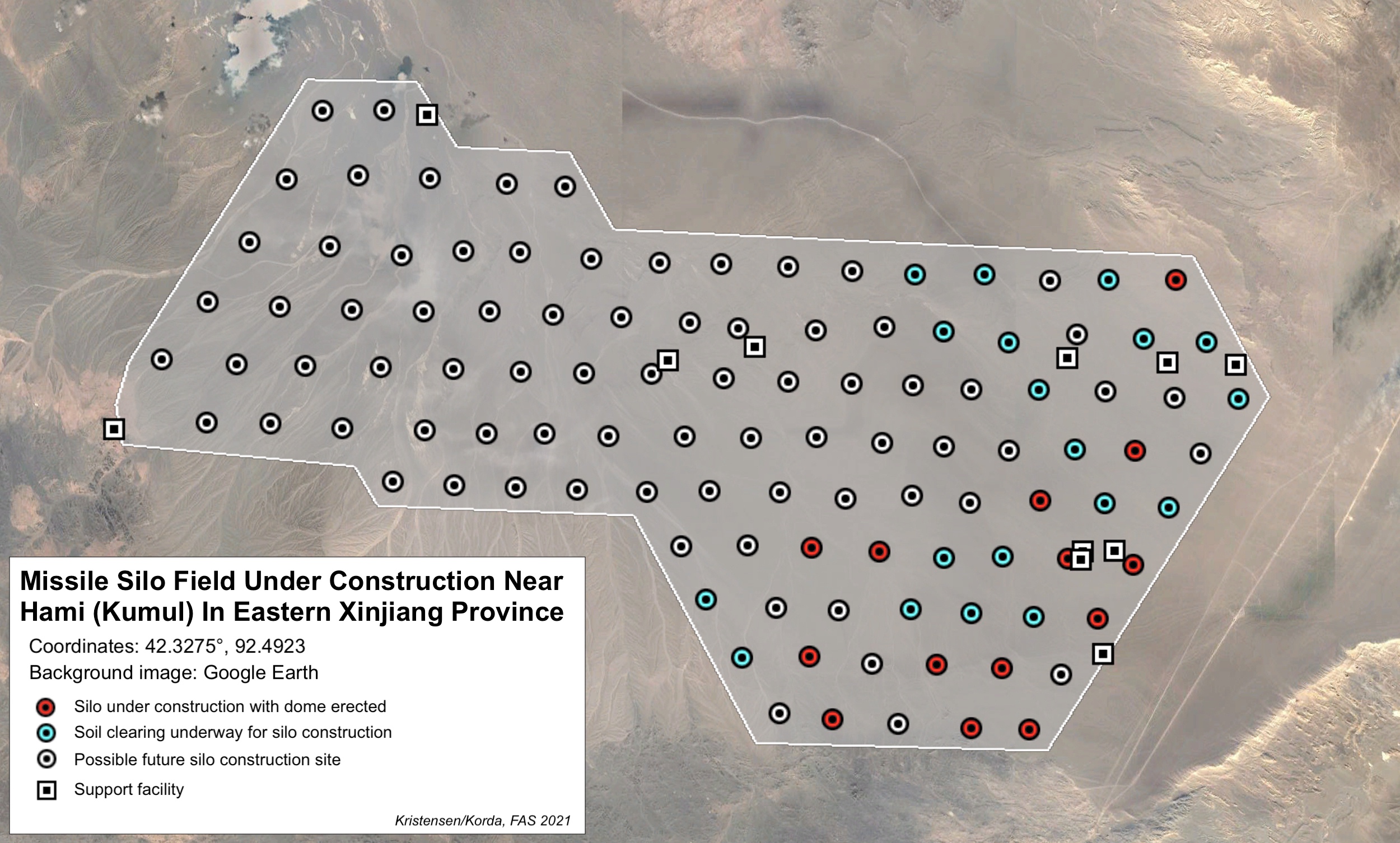

We have examined satellite photos of every single silo under construction in the three new large missile silo fields (Hami, Julin, and Yumen). It is impossible to determine with certainty from a satellite photo if a silo is completely finished, much less whether it is loaded with a missile. However, the available images indicate it is possible that most of the silos at Hami might have been complete by October 2022, that many of the silos at the Yumen field were still under construction, and that none of the silos at the Julin (Ordos) fields had been completed at the time of STRATCOM’s cutoff date (see image below).

Commercial satellite images help assess STRATCOM claim about China’s missile silos.

The number of Chinese ICBM launchers reported by the Pentagon over the past three years has increased significantly from 100 launchers at the end of 2020, to 300 launchers at the end of 2021, to now more than 450 launchers as of October 2022. That is an increase of 350 launchers in only three years.

To exceed the number of US ICBM launchers as most recently reported by STRATCOM, China would have to have more than 450 launchers (mobile and silo) – the US Air Force has 400 silos with missiles and another 50 empty silos that could be loaded as well if necessary. Without counting the new silos under construction, we estimate that China has approximately 140 operational ICBM launchers with as many missiles. To get to 300 launchers with as many missiles, as the 2022 China Military Power Report (CMPR) estimated, the Pentagon would have to include about 160 launchers from the new silo fields – half of all the silos – as not only finished but with missiles loaded in them. We have not yet seen a missile loading – training or otherwise – on any of the satellite photos. To reach 450 launchers as of October 2022, STRATCOM would have to count nearly all the silos in the three new missile silo fields (see graph below).

Pentagon estimates of Chinese completed ICBM launchers appear to include hundreds of new silos at three missile silo fields.

The point at which a silo is loaded with a missile depends not only on the silo itself but also on the operational status of support facilities, command and control systems, and security perimeters. Construction of that infrastructure is still ongoing at all the three missile silo fields.

It is also possible that the number of launchers and missiles in the Pentagon estimate is less directly linked. The number could potentially refer to the number of missiles for operational launchers plus missiles produced for launchers that have been more or less completed but not yet loaded with missiles.

All of that to underscore that there is considerable uncertainty about the operational status of the Chinese ICBM force.

However – in time for the Congressional debate on the FY2024 defense budget – some appear to be using the STRATCOM letter to suggest the United States also needs to increase its nuclear arsenal.

Comparing The Full Arsenals

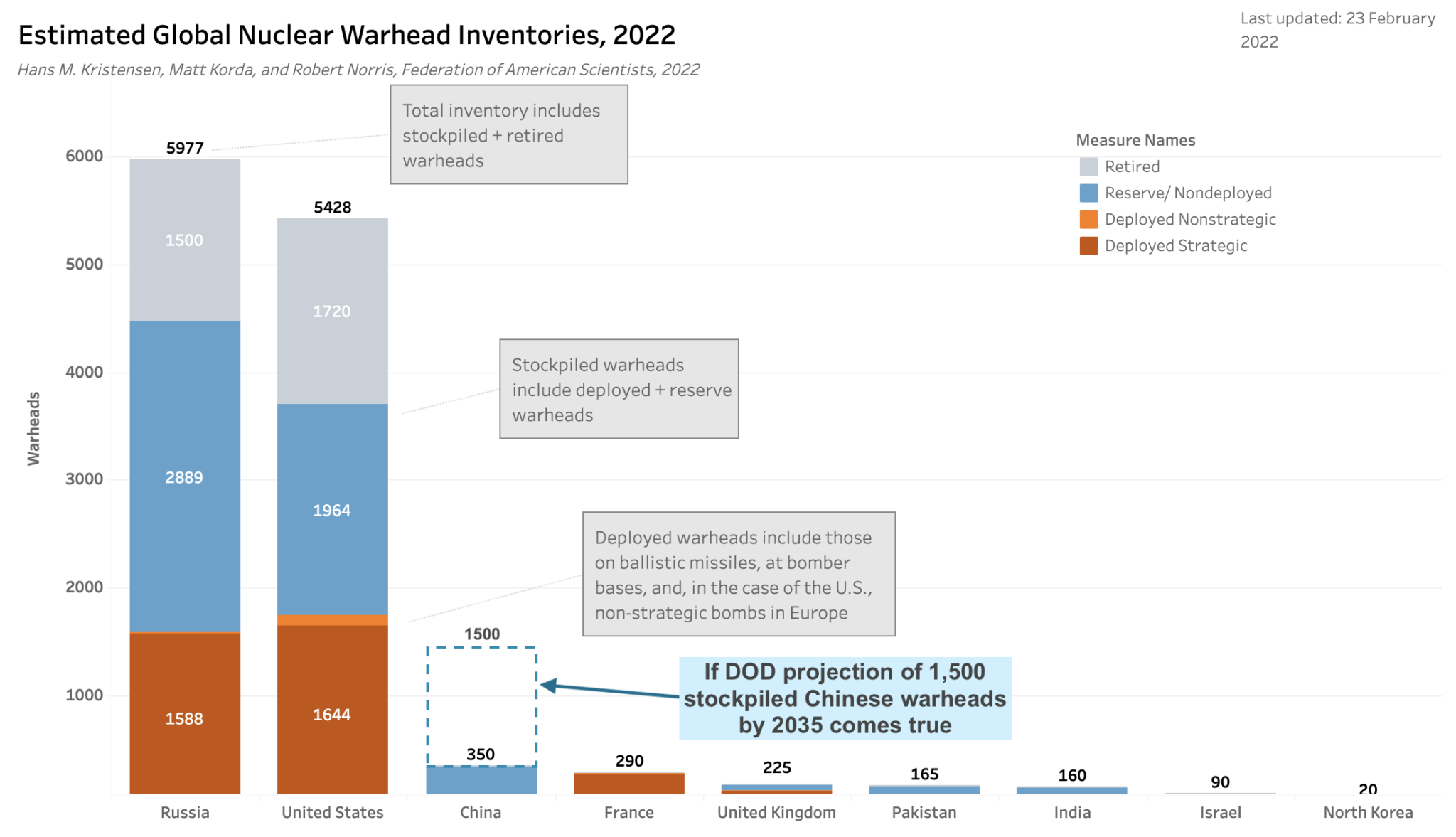

The rapid increase of the Chinese ICBM force is important and unprecedented. Yet, it is also crucial to keep things in perspective. In his response to the STRATCOM letter, Rep. Mike Rogers – the new conservative chairman of the House Armed Services Committee – claimed that China is “rapidly approaching parity with the United States” in nuclear forces. That is not accurate.

Even if China ends up with more ICBMs than the United States and increases its nuclear stockpile to 1,500 warheads by 2035, as projected by the Pentagon, that does not give China parity. The United States has 800 launchers for strategic nuclear weapons and a stockpile of 3,700 warheads (see graph below).

Even if China increases it nuclear weapons stockpile to 1,500 by 2035, it will only make up a fraction of the much larger US and Russian stockpiles.

The worst-case projection about China’s nuclear expansion assumes that it will fill everything with missiles with multiple warheads. In reality, it is unknown how many of the new silos will be filled with missiles, how many warheads each missile will carry, and how many warheads China can actually produce over the next decade.

The nuclear arsenals do not exist in a vacuum but are linked to the overall military capabilities and the policies and strategies of the owners.

The Political Dimension

STRATCOM initially informed Congress about its assessment that the number of Chinese ICBM launchers exceeded that of the United States back in November 2022. But the letter was classified, so four conservative members of the Senate and House armed services committees reminded STRATCOM that it was required to also release an unclassified version. They then used the unclassified letter to argue for more nuclear weapons stating (see screen shot of Committee web page below):

“We have no time to waste in adjusting our nuclear force posture to deter both Russia and China. This will have to mean higher numbers and new capabilities.” (Emphasis added.)

Lawmakers immediately used STRATCOM assessment of Chinese ICBM launchers to call for more US nuclear weapons.

Although defense contractors probably would be happy about that response, it is less clear why ‘higher numbers’ are necessary for US nuclear strategy. Increasing US nuclear weapons could in fact end up worsening the problem by causing China and Russia to increase their arsenals even further. And as we have already seen, that would likely cause a heightened demand for more US nuclear weapons.

We have seen this playbook before during the Cold War nuclear arms race. Only this time, it’s not just between the United States and the Soviet Union, but with Russia and a growing China.

Even before China will reach the force levels projected by the Pentagon, the last remaining arms control treaty with Russia – the New START Treaty – will expire in February 2026. Without a follow-on agreement, Russia could potentially double the number of warheads it deploys on its strategic launchers.

Even if the defense hawks in Congress have their way, the United States does not seem to be in a position to compete in a nuclear arms race with both Russia and China. The modernization program is already overwhelmed with little room for expansion, and the warhead production capacity will not be able to produce large numbers of additional nuclear weapons for the foreseeable future.

What the Chinese nuclear buildup means for Chinese nuclear policy and how the United States should respond to it (as well as to Russia) is much more complicated and important to address than a rush to get more nuclear weapons. It would be more constructive for the United States to focus on engaging with Russia and China on nuclear risk reduction and arms control rather than engage in a build-up of its nuclear forces.

Additional Information:

Status of World Nuclear Forces

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The 2022 Nuclear Posture Review: Arms Control Subdued By Military Rivalry

On 27 October 2022, the Biden administration finally released an unclassified version of its long-delayed Nuclear Posture Review (NPR). The classified NPR was released to Congress in March 2022, but its publication was substantially delayed––likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Compared with previous NPRs, the tone and content come closest to the Obama administration’s NPR from 2010. However, it contains significant adjustments because of the developments in Russia and China. (See also our global overview of nuclear arsenals)

Despite the challenges presented by Russia and China, the NPR correctly resists efforts by defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists to add nuclear weapons to the U.S. arsenal and delay the retirement of older types. Instead, the NPR seeks to respond with adjustments in the existing force posture and increase integration of conventional and nuclear planning.

Although Joe Biden during his presidential election campaign spoke strongly in favor of adopting no-first-use and sole-purpose policies, the NPR explicitly rejects both for now.

From an arms control and risk reduction perspective, the NPR is a disappointment. Previous efforts to reduce nuclear arsenals and the role that nuclear weapons play have been subdued by renewed strategic competition abroad and opposition from defense hawks at home.

Even so, the NPR concludes it may still be possible to reduce the role that nuclear weapons play in scenarios where nuclear use may not be credible.

Unlike previous NPRs, the 2022 version is embedded into the National Defense Strategy document alongside the Missile Defense Review.

Below is our summary and analysis of the major portions of the NPR:

The Nuclear Adversaries

The NPR identifies four potential adversaries for U.S. nuclear weapons planning: Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. Of these, Russia and China are obviously the focus because of Russia’s large arsenal and aggressive behavior and because of China’s rapidly increasing arsenal. The NPR projects that “[b]y the 2030s the United States will, for the first time in its history, face two major nuclear powers as strategic competitors and potential adversaries.” This echoes previous statements from high-ranking US military leaders, including the former and incoming Commanders of US Strategic Command although the NPR appears less “the sky is falling.”

China: Given that the National Defense Strategy is largely focused on China, it is unsurprising that the NPR declares China to be “the overall pacing challenge for U.S. defense planning and a growing factor in evaluating our nuclear deterrent.”

Echoing the findings of the previous year’s China Military Power Report, the NPR suggests that “[t]he PRC likely intends to possess at least 1,000 deliverable warheads by the end of the decade.” According to the NPR, China’s more diverse nuclear arsenal “could provide the PRC with new options before and during a crisis or conflict to leverage nuclear weapons for coercive purposes, including military provocations against U.S. Allies and partners in the region.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on Chinese nuclear forces.

Russia: The NPR presents harsh language about Russia, in particular surrounding its behavior around the invasion of Ukraine. In contrast to the Trump administration’s NPR, the assumptions surrounding a potential low-yield “escalate-to-deescalate” policy have been toned down; instead the NPR simply states that Russia is diversifying its arsenal and that it views its nuclear weapons as “a shield behind which to wage unjustified aggression against [its] neighbors.”

The review’s estimate of Russian non-strategic nuclear weapons –– “up to 2,000 –– matches those of previous military statements. In 2021, the Defense Intelligence Agency concluded that Russia “probably possesses 1,000 to 2,000 nonstrategic nuclear warheads.” The State Department said in April 2022 that the estimate includes retired weapons awaiting dismantlement. The subtle language differences reflect a variance in estimates between the different US military departments and agencies.

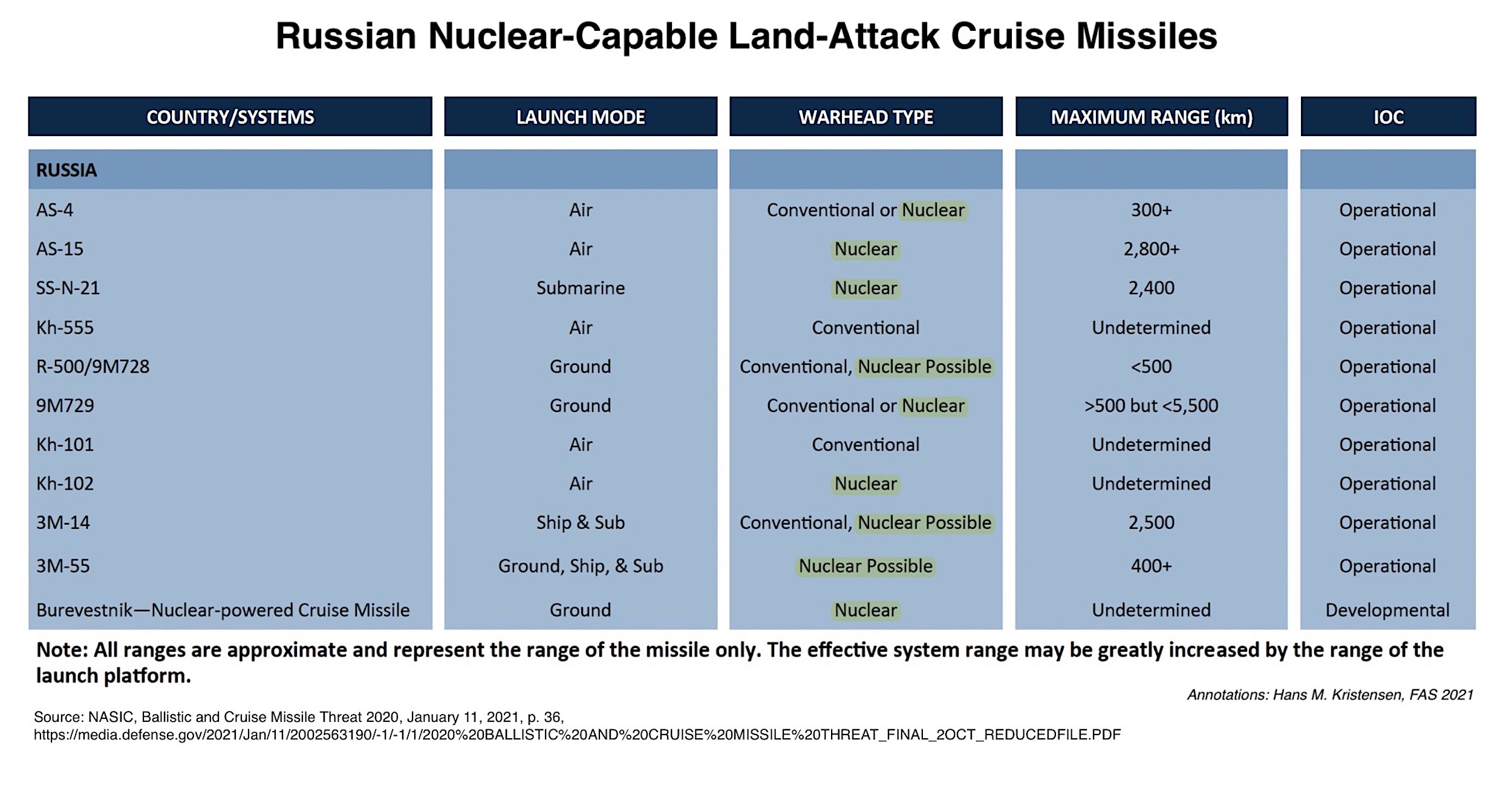

The NPR also suggests that “Russia is pursuing several novel nuclear-capable systems designed to hold the U.S. homeland or Allies and partners at risk, some of which are also not accountable under New START.” Given that both sides appear to agree that Russia’s new Sarmat ICBM and Avangard hypersonic glide vehicle fit smoothly into the treaty, this statement is likely referring to Russia’s development of its Burevestnik nuclear-powered cruise missile, its Kinzhal air-launched ballistic missile, and its Status-6 Poseidon nuclear torpedo.

It appears that Russia and the United States are at odds over whether these three systems are treaty-accountable weapons. In 2019, then-Under Secretary Andrea Thompson noted during congressional testimony that all three “meet the US criteria for what constitutes a “new kind of strategic offensive arms’ for purposes of New START.” However, Russian officials had previously sent a notice to the United States stating that they “find it inappropriate to characterize new weapons being developed by Russia that do not use ballistic trajectories of flight moving to a target as ‘potential new kinds of Russian strategic offensive arms.’ The arms presented by the President of the Russian Federation on March 1, 2018, have nothing to do with the strategic offensive arms categories covered by the Treaty.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on Russian nuclear forces.

North Korea: In recent years, North Korea has been overshadowed by China and Russia in the U.S. defense debate. Nonetheless this NPR describes North Korea as a target for U.S. nuclear weapons planning. The NPR bluntly states: “Any nuclear attack by North Korea against the United States or its Allies and partners is unacceptable and will result in the end of that regime. There is no scenario in which the Kim regime could employ nuclear weapons and survive.”

See also our Nuclear Notebook on North Korean nuclear forces.

Iran: The NPR also describes Iran even though it does not have nuclear weapons. Interestingly, although Iran is not in compliance with its NPT obligations and therefore does not qualify for the U.S. negative security assurances, the NPR declares that the United States “relies on non-nuclear overmatch to deter regional aggression by Iran as long as Iran does not possess nuclear weapons.”

Nuclear Declaratory Policy

The NPR reaffirms long-standing U.S. policy about the role of nuclear weapons but with slightly modified language. The role is: 1) Deter strategic attacks, 2) Assure allies and partners, and 3) Achieve U.S. objectives if deterrence fails.

The NPR reiterates the language from the 2010 NPR that the “fundamental role” of U.S. nuclear weapons “is to deter nuclear attacks” and only in “extreme circumstances.” The strategy seeks to “maintain a very high bar for nuclear employment” and, if employment of nuclear weapons is necessary, “seek to end conflict at the lowest level of damage possible on the best achievable terms for the United States and its Allies and partners.”

Deterring “strategic” attacks is a different formulation than the “deterrence of nuclear and non-nuclear attack” language in the 2018 NPR, but the new NPR makes it clear that “strategic” also accounts for existing and emerging non-nuclear attacks: “nuclear weapons are required to deter not only nuclear attack, but also a narrow range of other high consequence, strategic-level attacks.”

Indeed, the NPR makes clear that U.S. nuclear weapons can be used against the full spectrum of threats: “While the United States maintains a very high bar for the employment of nuclear weapons, our nuclear posture is intended to complicate an adversary’s entire decision calculus, including whether to instigate a crisis, initiate armed conflict, conduct strategic attacks using non-nuclear capabilities, or escalate to the use of nuclear weapons on any scale.”

During his presidential campaign, Joe Biden spoke repeatedly in favor of a no-first-use and sole-purpose policy for U.S. nuclear weapons. But the NPR explicitly rejects both under current conditions. The public version of the NPR doesn’t explain why a no-first-use policy against nuclear attack is not possible, but it appears to trim somewhat the 2018 NPR language about an enhanced role of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear strategic attacks. And the stated goal is still “moving toward a sole purpose declaration” when possible in consultation with Allies and partners.

In that context the NPR reiterates previous “negative security assurances” that the United States “will not use or threaten to use nuclear weapons against non-nuclear weapon states that are party to the NPT [Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty] and in compliance with their nuclear non-proliferation obligations.”

“For all other states” the NPR warns, “there remains a narrow range of contingencies in which U.S. nuclear weapons may still play a role in deterring attacks that have strategic effect against the United States or its Allies and partners.” That potentially includes Iran, North Korea, and Pakistan.

Interestingly, the NPR states that “hedging against an uncertain future” is no longer a stated (formal) role of nuclear weapons. Hedging has been part of a strategy to be able to react to changes in the threat environment, for example by deploying more weapons or modifying capabilities. The change does not mean that the United States is no longer hedging, but that hedging is part of managing the arsenal, rather than acting as a role for nuclear weapons within US military strategy writ large.

The NPR reaffirms, consistent with the 2013 Nuclear Employment Strategy, that U.S. use of nuclear weapons must comply with the Law of Armed Conflict (LOAC) and that it is U.S. policy “not to purposely threaten civilian populations or objects, and the United States will not intentionally target civilian populations or objects in violation of LOAC.” That means that U.S. nuclear forces cannot attack cities per se (unless they contain military targets).

Nuclear Force Structure

The NPR reaffirms a commitment to the modernization of its nuclear forces, nuclear command and control and communication systems (NC3), and production and support infrastructure. This is essentially the same nuclear modernization program that has been supported by the previous two administrations.

But there are some differences. The NPR also identifies “current and planned nuclear capabilities that are no longer required to meet our deterrence needs.” This includes retiring the B83-1 megaton gravity bomb and cancelling the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N). These decisions were expected and survived opposition from defense hawks and nuclear lobbyists.

Although the NPR has decided to move forward with retirement of the B83-1 bomb due to increasing limitations on its capabilities and rising maintenance costs, the NPR appears to hint at a replacement weapon “for improved defeat” of hard and deeply buried targets. The new weapon is not identified.

The NPR concludes that “SLCM-N was no longer necessary given the deterrence contribution of the W76-2, uncertainty regarding whether SLCM-N on its own would provide leverage to negotiate arms control limits on Russia’s NSNW, and the estimated cost of SLCM-N in light of other nuclear modernization programs and defense priorities.” This language is more subtle than the administration’s recent statement rebutting Congress’ attempt to fund the SLCM-N, which states:

“The Administration strongly opposes continued funding for the nuclear sea-launched cruise missile (SLCM-N) and its associated warhead. The President’s Nuclear PostureReview concluded that the SLCM-N, which would not be delivered before the 2030s, is unnecessary and potentially detrimental to other priorities. […] Further investment in developing SLCM-N would divert resources and focus from higher modernization priorities for the U.S. nuclear enterprise and infrastructure, which is already stretched to capacity after decades of deferred investments. It would also impose operational challenges on the Navy.

In justifying the cancelation of the SLCM-N, the NPR spells out the existing and future capabilities that adequately enable regional deterrence of Russia and China. This includes the W76-2 (the low-yield warhead for the Trident II D5 submarine-launched ballistic missile proposed and deployed under the Trump administration), globally-deployed strategic bombers, air-launched cruise missiles, and dual-capable fighter aircraft such as as the F-35A equipped with the new B61-12 nuclear bomb.

The NPR concludes that the W76-2 “currently provides an important means to deter limited nuclear use.” However, the review leaves the door open for its possible removal from the force structure in the future: “Its deterrence value will be re-evaluated as the F-35A and LRSO are fielded, and in light of the security environment and plausible deterrence scenarios we could face in the future.”

The review also notes that “[t]he United States will work with Allies concerned to ensure that the transition to modern DCA [dual-capable aircraft] and the B61-12 bomb is executed efficiently and with minimal disruption to readiness.” The release of the NPR coincides with the surprise revelation that the United States has sped up the deployment of the B61-12 in Europe. Previously scheduled for spring 2023, the first B61-12 gravity bombs will now be delivered in December 2022, likely due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Putin’s nuclear belligerency. Given that the Biden administration has previously taken care to emphasize that its modernization program and nuclear exercises are scheduled years in advance and are not responses to Russia’s actions, it is odd that the administration would choose to rush the new bombs into Europe at this time.

The NPR appears to link the non-strategic nuclear posture in Europe more explicitly to recent Russian aggression. “Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the occupation of Crimea in 2014, NATO has taken steps to ensure a modern, ready, and credible NATO nuclear deterrent.” While that is true, some of those steps were already underway before 2014 and would have happened even if Russia had not invaded Ukraine. This includes extensive modernizations at the bases and of the weapons and adding the United Kingdom to the nuclear storage upgrades. But the NPR also states that “Further steps are needed to fully adapt these forces to current and emerging security conditions,” including to “enhance the readiness, survivability and effectiveness of the DCA mission across the conflict spectrum, including through enhanced exercises…”

In the Pacific region, the NPR continues and enhances extended deterrence with U.S. capabilities and deepened consultation with Allies and partners. The role of Australia appears to be increasing. An overall goal is to “better synchronize the nuclear and non-nuclear elements of deterrence” and to “leverage Ally and partner non-nuclear capabilities that can support the nuclear nuclear deterrence mission.” The last part sounds similar to the so-called SNOWCAT mission in NATO where Allies support the nuclear strike mission with non-nuclear capabilities.

Nuclear-Conventional Integration

Although the integration of nuclear and conventional capabilities into strategic deterrence planning has been underway for years, the NPR seeks to deepen it further. It “underscores the linkage between the conventional and nuclear elements of collective deterrence and defense” and adopts “an integrated deterrence approach that works to leverage nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities to tailor deterrence under specific circumstances.”

This is not only intended to make deterrence more flexible and less nuclear focused when possible, but it also continues the strategy outlined in the 2010 NPR and 2013 Nuclear Employment Guidance to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons by relying more on new conventional capabilities.

According to the NPR, “Non-nuclear capabilities may be able to complement nuclear forces in strategic deterrence plans and operations in ways that are suited to their attributes and consistent with policy on how they are employed.” Although further integration will take time, the NPR describes “how the Joint Force can combine nuclear and non-nuclear capabilities in complementary ways that leverage the unique attributes of a multi-domain set of forces to enable a range of deterrence options backstopped by a credible nuclear deterrent.” An important part of this integration is to “better synchronize nuclear and non-nuclear planning, exercises, and operations.”

Beyond force structure issues, this effort also appears to be a way to “raise the nuclear threshold” by reducing reliance on nuclear weapons but still endure in regional scenarios where an adversary escalates to limited nuclear use. In contrast, the 2018 NPR sought low-yield non-strategic “nuclear supplements” for such a scenario, and specifically named a Russian so-called “escalate-to-deescalate” scenario as a potentially possibility for nuclear use.

Moreover, conventional integration can also serve to reduce reliance on nuclear weapons in response to non-nuclear strategic attacks, and could therefore pave the way for a sole-purpose policy in the future (see also An Integrated Approach to Deterrence Posture by Adam Mount and Pranay Vaddi).

Finally, increasing conventional capabilities in deterrence planning also allows for deeper and better integration of Allies and partners without having to rely on more controversial nuclear arrangements.

A significant challenge of deeper nuclear-conventional integration in strategic deterrence is to ensure that it doesn’t blur the line between nuclear and conventional war and inadvertently increase nuclear signaling during conventional operations.

Arms Control and Non-Proliferation

The NPR correctly concludes that deterrence alone will not reduce nuclear dangers and reaffirms the U.S. commitment to arms control, risk reduction, and nonproliferation. It does so by stating that the United States will pursue “a comprehensive and balanced approach” that places “renewed emphasis on arms control, non-proliferation, and risk reduction to strengthen stability, head off costly arms races, and signal our desire to reduce the salience of nuclear weapons globally.”

The Biden administration’s review contains significantly more positive language on arms control than can be found in the Trump administration’s NPR. The NPR concludes that “mutual, verifiable nuclear arms control offers the most effective, durable and responsible path to achieving a key goal: reducing the role of nuclear weapons in U.S. strategy.”

In that vein, the review states a willingness to “expeditiously negotiate a new arms control framework to replace New START,” as well as an expansive recommitment to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty” (CTBT), and the Fissile Material Cutoff Treaty (FMCT). However, the authors take a negative view of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), stating that the United States does not “consider the TPNW to be an effective tool to resolve the underlying security conflicts that lead states to retain or seek nuclear weapons.”

Although the NPR states that “major changes” in the role of U.S. nuclear weapons against Russia and China will require verifiable reductions and constraints on their nuclear forces, it also concludes that there “is some opportunity to reduce the role of nuclear weapons in our strategies for [China] and Russia in circumstances where the threat of a nuclear response may not be credible and where suitable non-nuclear options may exist or may be developed.” The NPR does not identify what those scenarios are.

Looking Ahead

Many of the activities described in the NPR are already well underway. Now that the NPR has been completed and published, the Pentagon will produce an NPR implementation plan that identifies specific decisions to be carried out.

Flowing from the reviews that were done in preparation of the NPR, the White House will move forward with an update to the nuclear weapons employment guidance. This guidance will potentially include changes to the strike plans and the assumptions and the assumptions and requirements that underpin them.

The Biden administration must use this opportunity to scrutinize more closely the simulations and analysis that U.S. Strategic Command is using to set nuclear force structure requirements.

––

Additional analysis can be found on our FAS Nuclear Posture Review Resource Page.

For an overview of global modernization programs, see our annual contribution to the SIPRI Yearbook and our Status of World Nuclear Forces webpage. Individual country profiles are available in various editions of the FAS Nuclear Notebook, which is published by the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists and is freely available to the public.

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, the Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

A Closer Look at China’s Missile Silo Construction

What’s underneath the shelters over China’s suspected silo construction sites? Image © 2021 Maxar Technologies

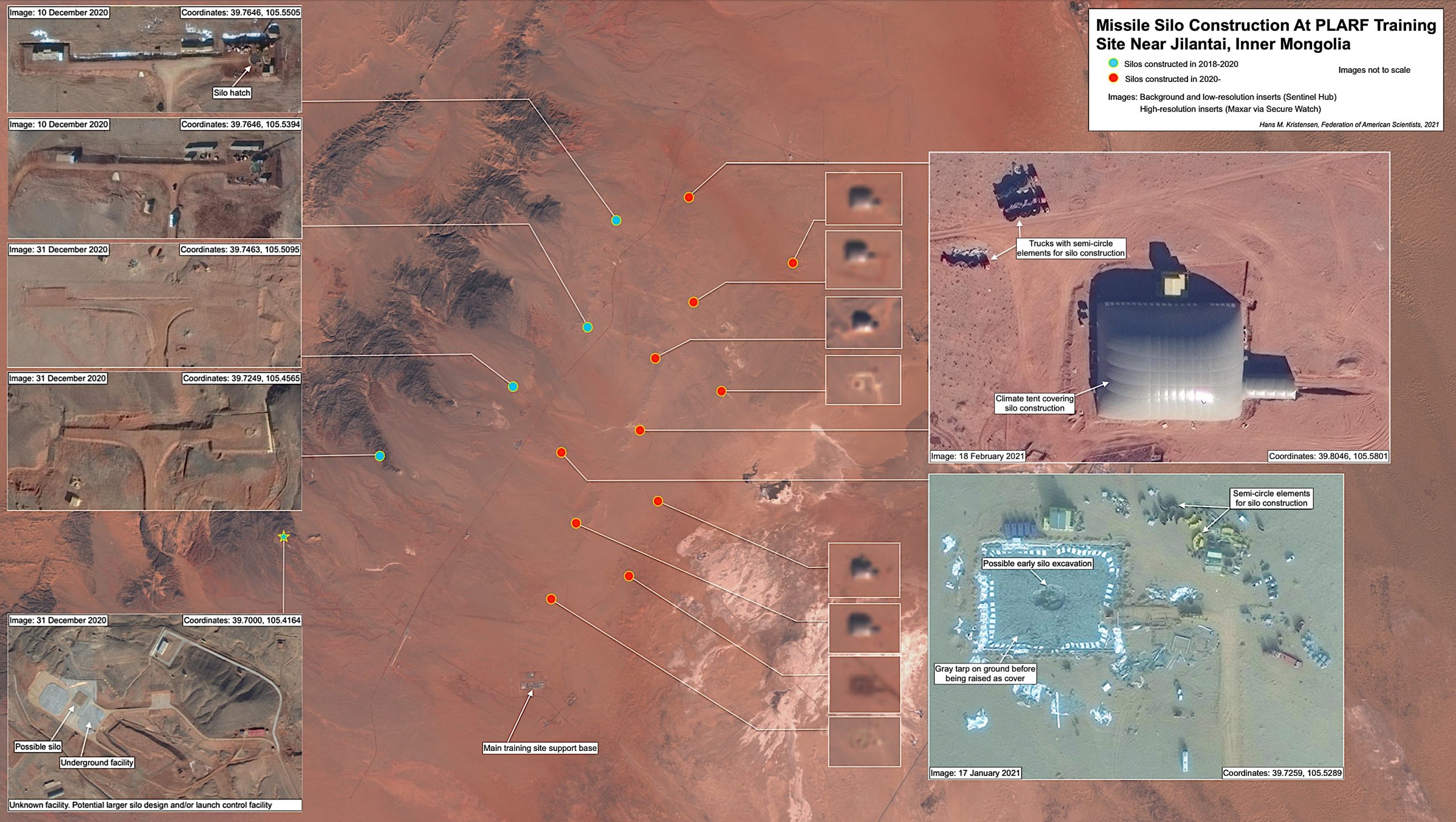

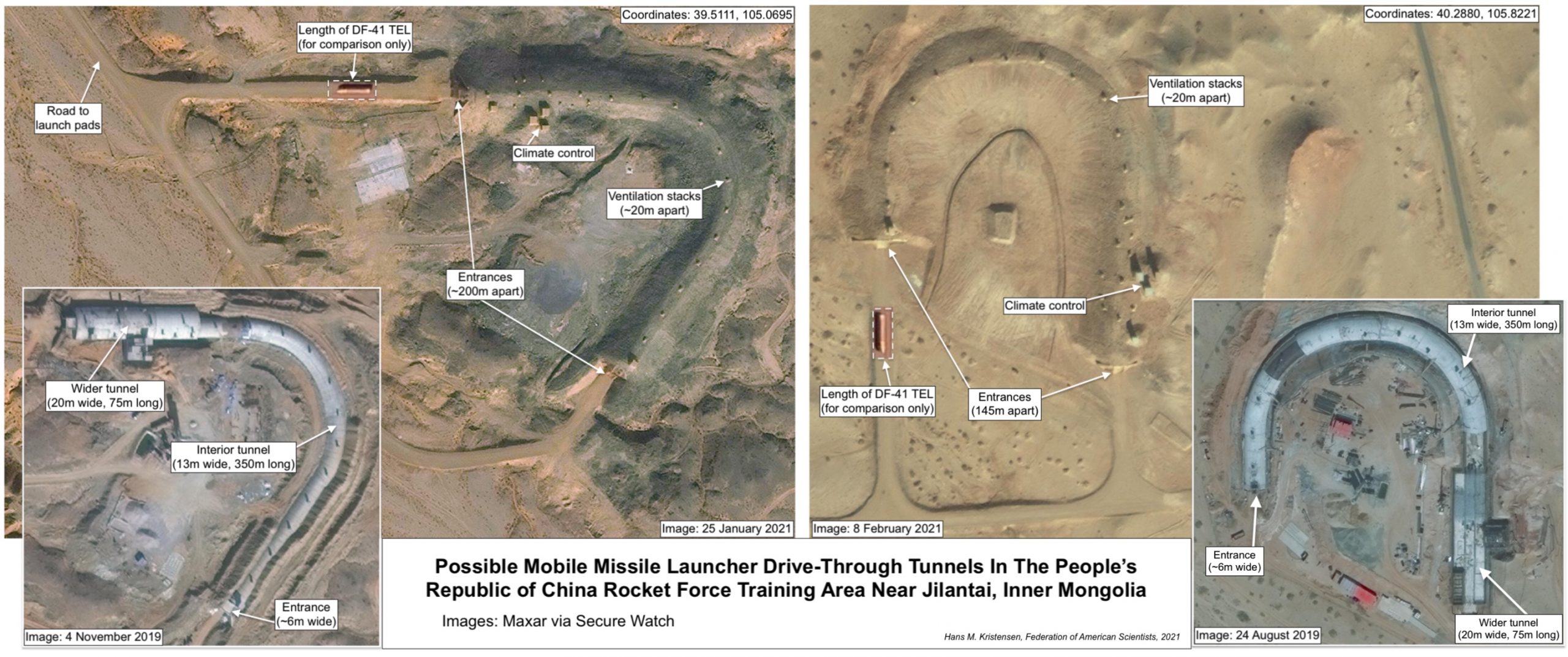

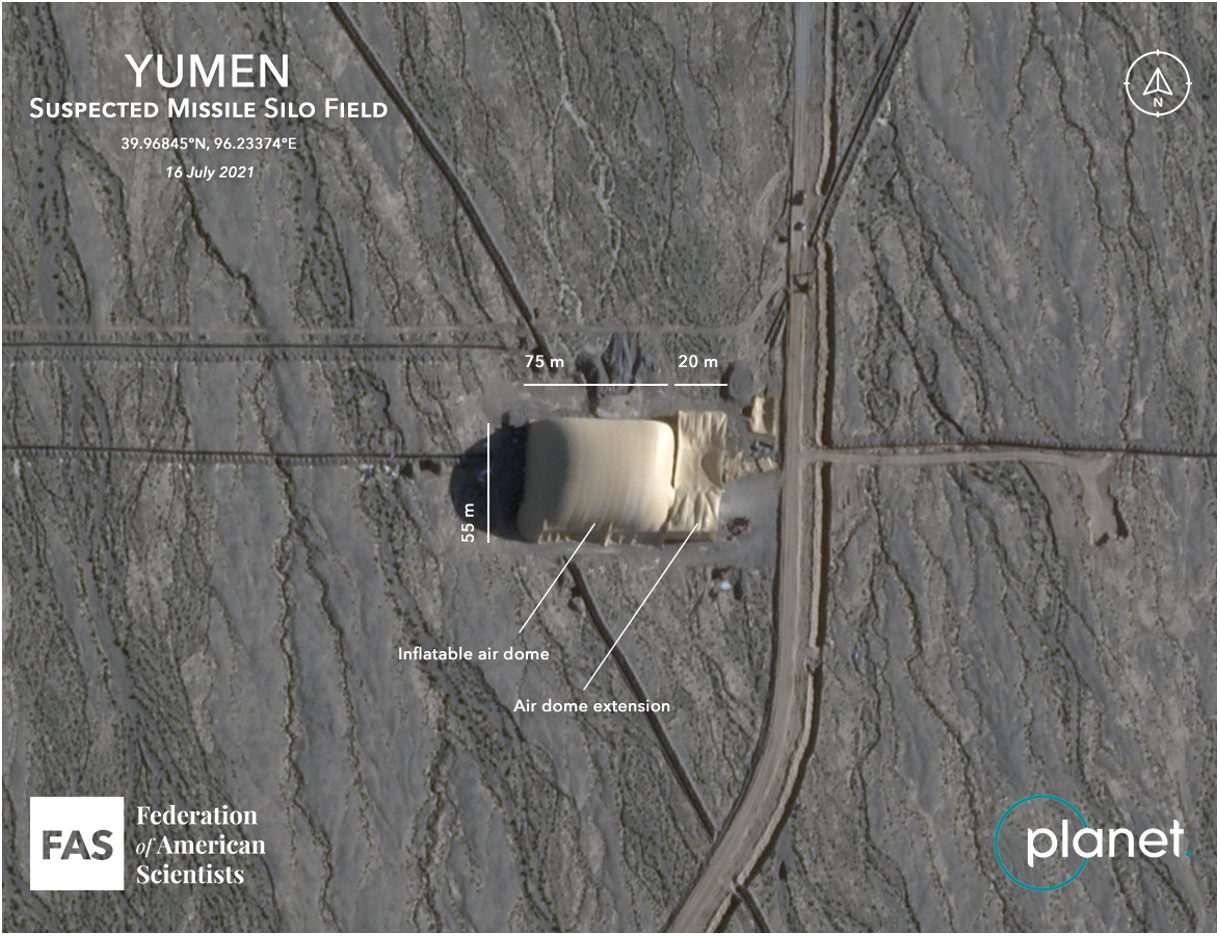

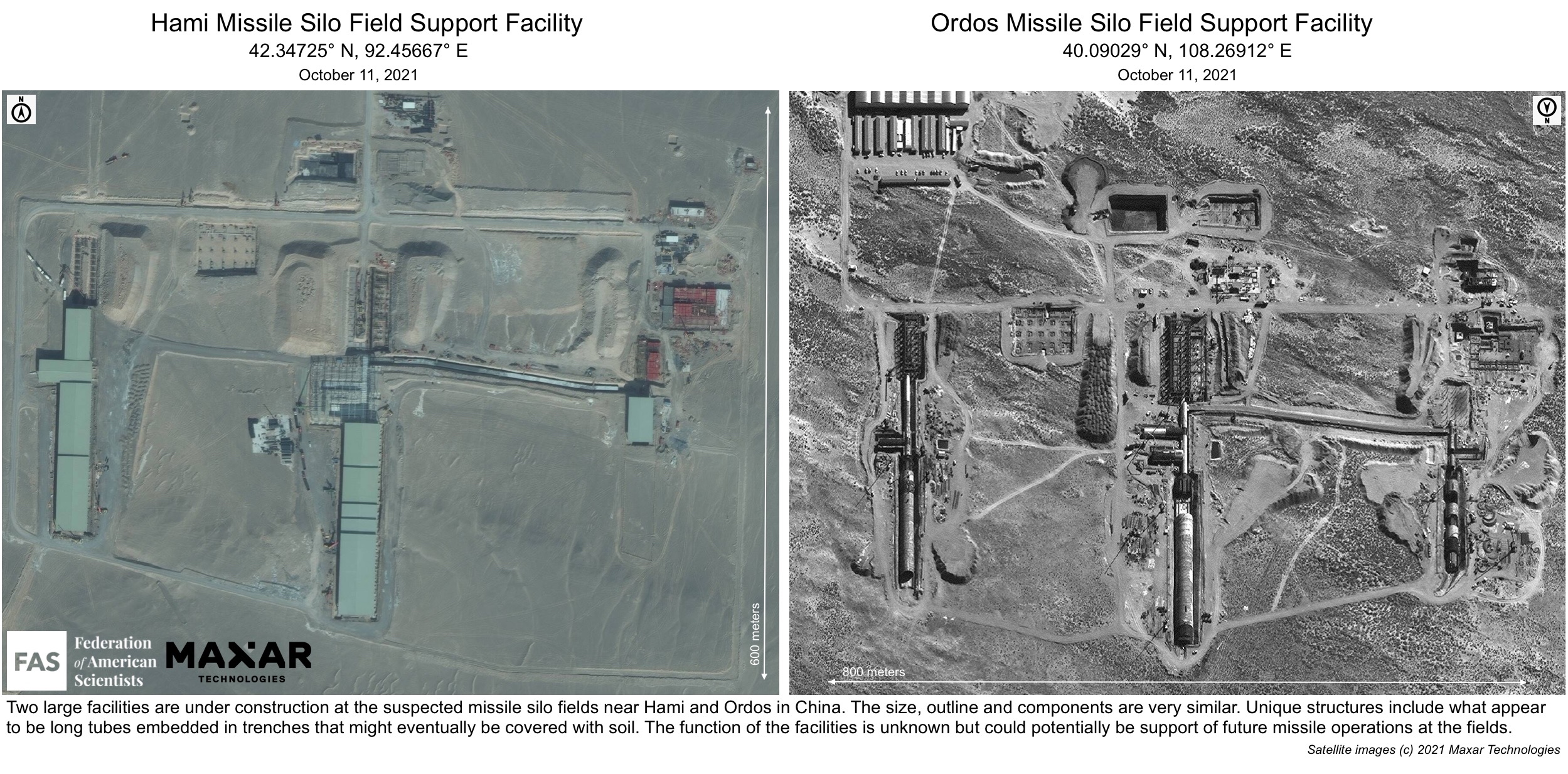

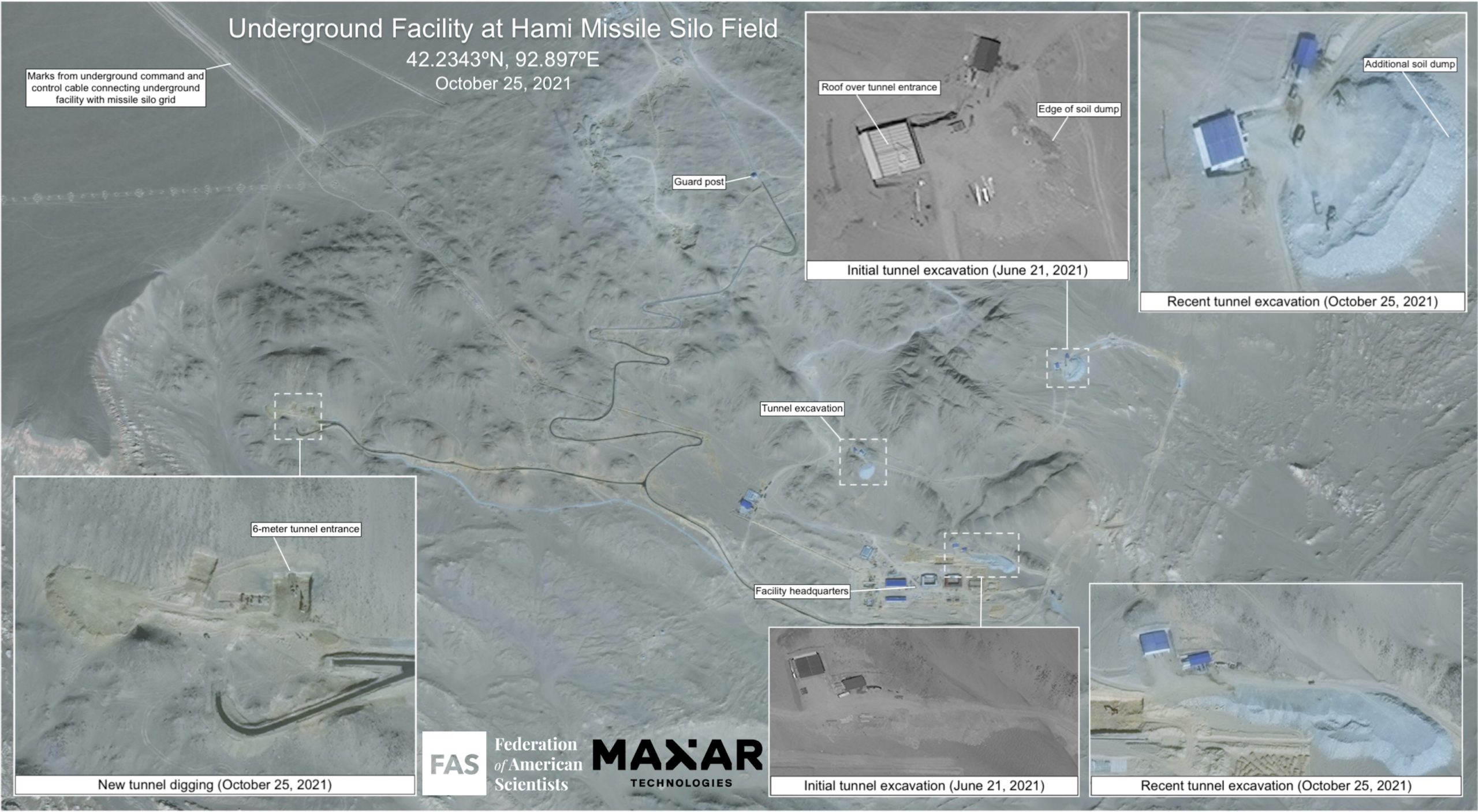

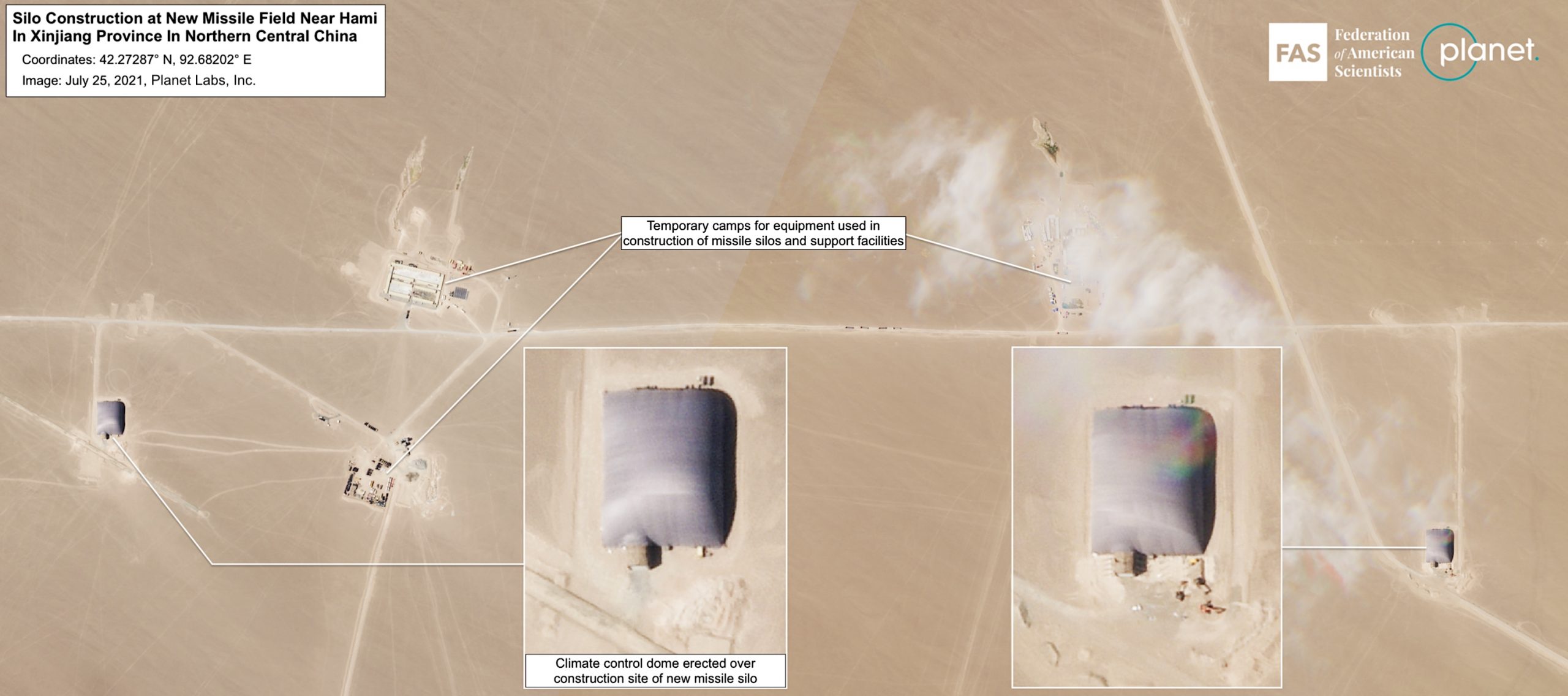

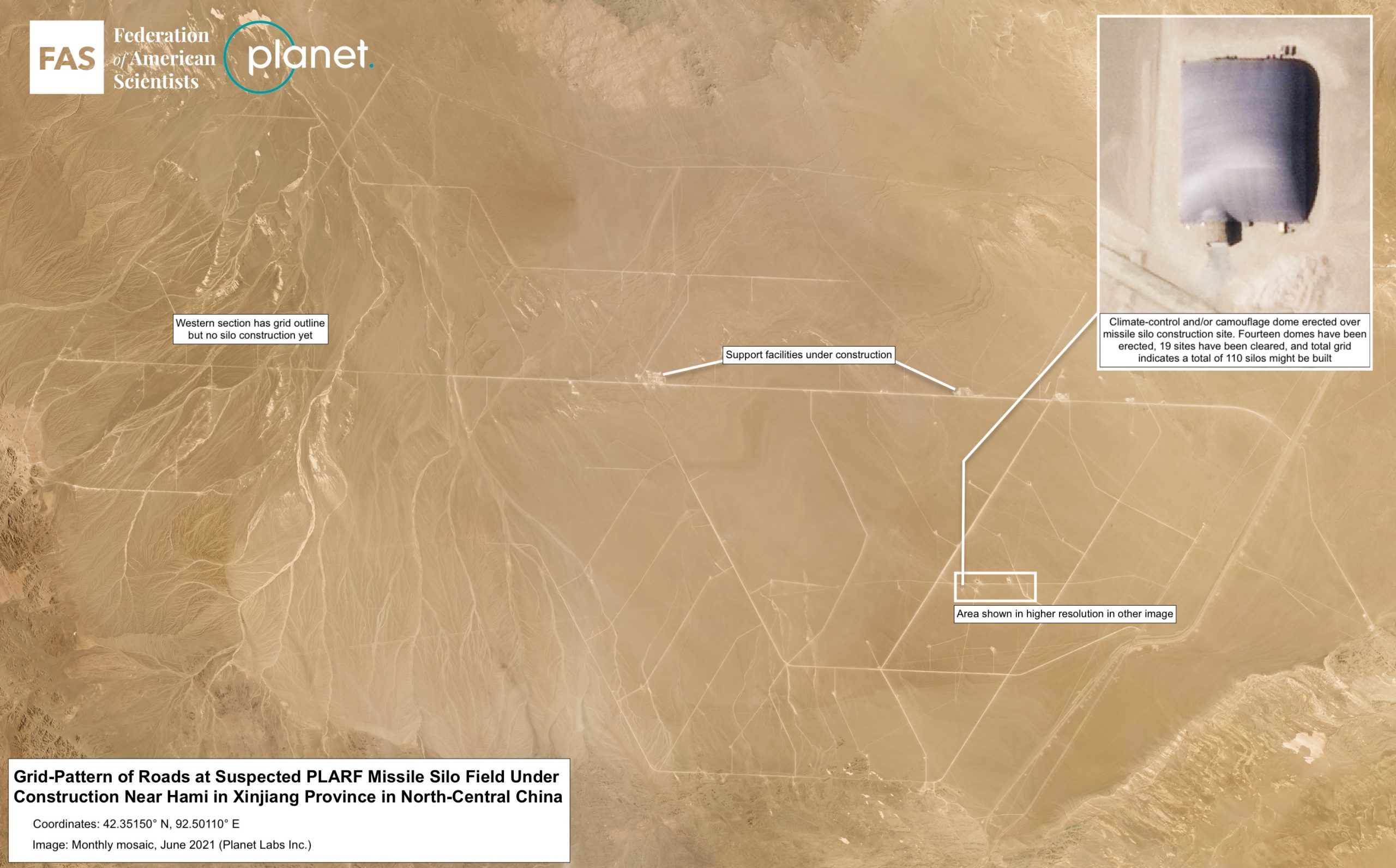

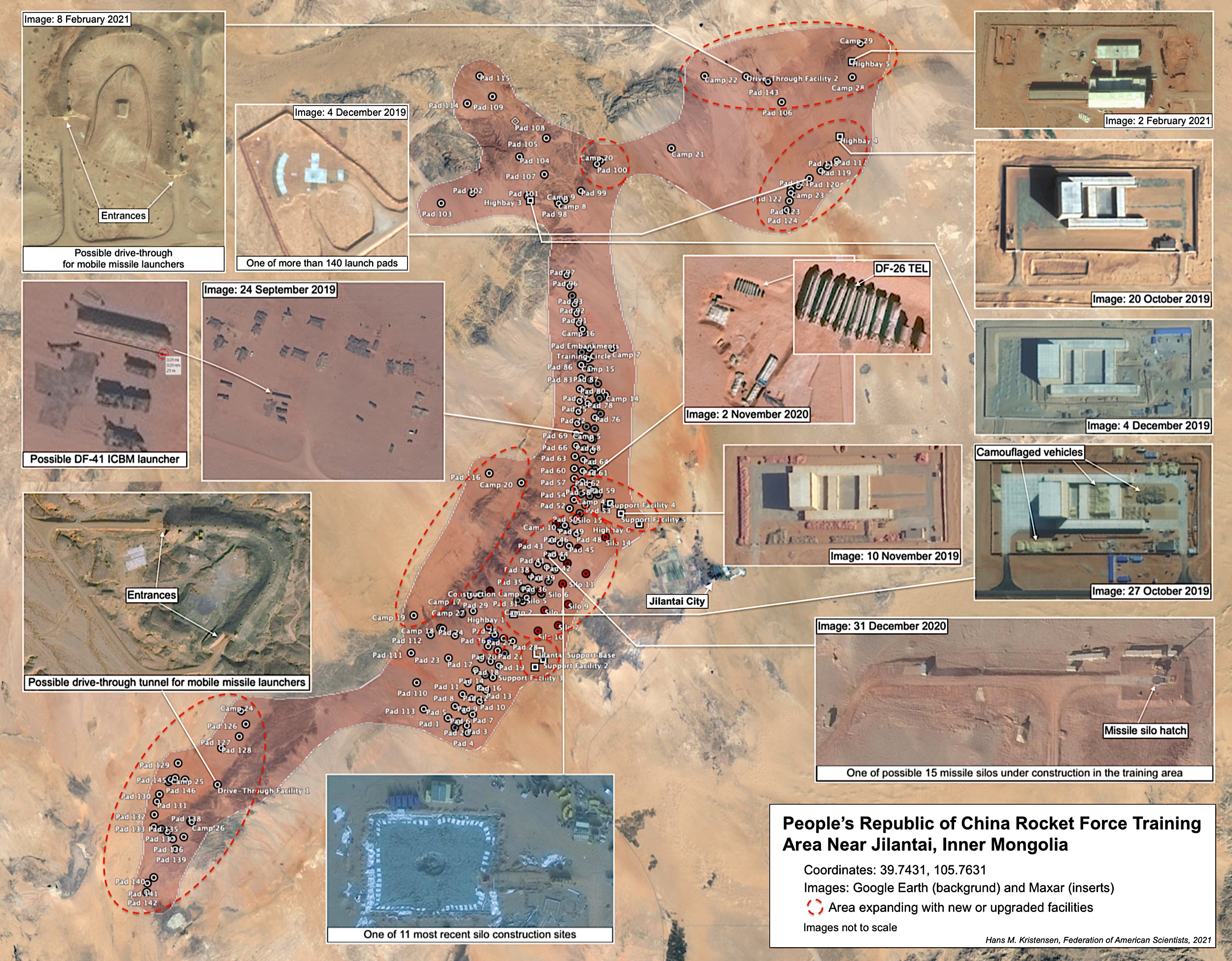

After the discovery during the summer of what appears to be at least three vast missile silo fields under construction near Yumen, Hami, and Ordos in north-central China, new commercial satellite images show significant progress at the three sites as well as at the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF)’s training site near Jilantai.

The images provide a vivid and rare public look into what is otherwise a top-secret and highly sensitive construction program. The Chinese government has still not officially confirmed or denied that the facilities under construction are silos intended for missiles and there are many uncertainties and unknowns about the nature and role of the facilities. In this article we use words like suspected, apparent, and probable to remind the reader of that fact.

Yet our analysis of hundreds of satellite images over the past three years of the suspected missile silo fields and the different facilities that are under construction at each of them have increased our confidence that they are indeed related to the PLARF’s modernization program. In recent analysis of new satellite images obtained from Planet Labs and Maxar Technologies, we have observed almost weekly progress in construction of suspected silos as well as discovered unique facilities that appear intended to support missile operations once the silo fields become operational.

In this article we describe the progress we have observed. We first describe the shelters, then what we see under the shelters, unique support facilities, and end with overall observations.

Shelter Features and Activities

Some of the most visible features at each of China’s newly-discovered probable missile silo fields are the environmental shelters that cover each suspected silo headworks. It was these structures, first seen at Jilantai, that led to the discovery of the three large suspected missile silo fields. Shelters are not new phenomena in Chinese missile construction; declassified reports from the US National Photographic Interpretation Center suggest that in the 1970s and 1980s China used a mixture of “large rectangular covers,” “camouflage nets,” and other types of shelters to protect its silos from the elements, as well as from spy satellites above.

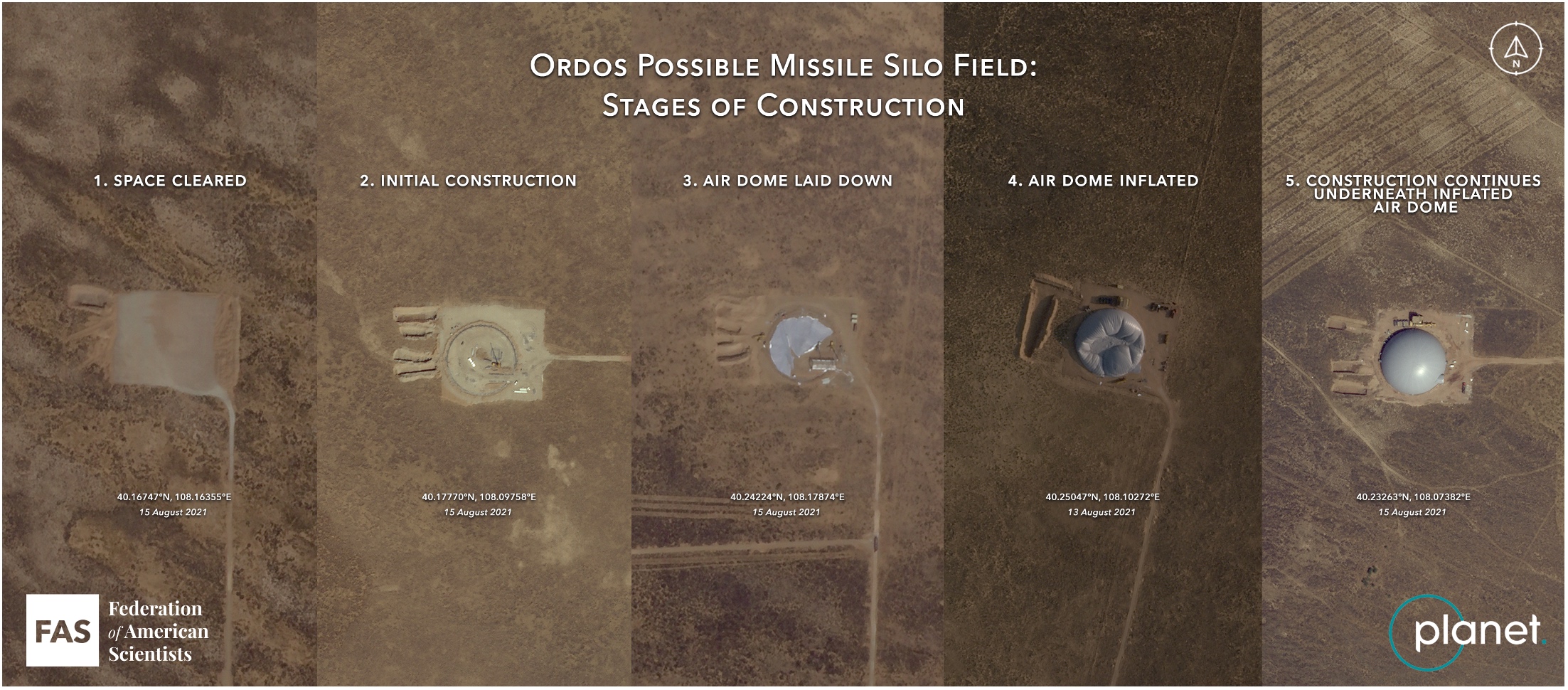

The construction progression typically goes like this: a space for each silo headworks is cleared, then the shelter is erected before large-scale excavation begins. Occasionally the silo hole – or part of it – is excavated first and the shelter is erected over it before the silo components are installed. Several satellite images show semi-circle structural forms that may be lowered into the hole and assembled to form the silo walls during this phase. Several months later, the shelter is removed, and construction continues in the open-air with less sensitive auxiliary structures.

Suspected missile silos near Ordos at different stages of construction. Images © 2021 Planet Labs.

Apart from hiding silo details from satellites, these environmental shelters play an important role in the construction process: winter temperatures in areas like the Jilantai training area can reach below -25 degrees Celsius and pouring concrete in cold temperatures can cause it to freeze and crack. Additionally, many of China’s suspected silo sites are located in desert areas with periodic sandstorms. Spring floods are another challenge, so many silo sites and roads are elevated above the ground level and often with barriers or tunnels to prevent water damage. Environmental shelters, therefore, help keep construction running smoothly and on schedule year round, and they can be erected and dismantled in just a couple of days.

Interestingly, China appears to be experimenting with several different types of shelters for each of its suspected silo fields. The reason for this may have to do with practical construction issues rather than what is being constructed under them.

- Short Rectangular Shelters

The most common shelter visible at China’s suspected silo complexes is a rectangular dome-like structure very similar to those used at indoor tennis courts or soccer pitches. Each structure appears to be air-inflated with an estimated area of 4,125 square meters, and must be accessed through a series of airlocks––one for pedestrians and an extended one for vehicles. The external ventilation system provides climate control and a slight continuous overpressure inside the dome, allowing it to retain its rounded shape. See example of inflatable shelter.

Identical rectangular air domes are visible at the Jilantai missile training area, the suspected Yumen silo site, and the suspected Hami silo site. While this does not necessarily prove that identical construction is taking place underneath each dome, it does imply a connection of the activities at the three sites.

Identical shelter domes seen at Hami, Yumen, and Jilantai. Images © Planet Labs.

In July 2021, Capella Space––a satellite company specializing in synthetic aperture radar––imaged one of the domes at the Yumen site. The SAR image allowed analysts to see the outlines of some structures underneath the dome, although it is difficult to discern much from the image except the clearly-visible framework of the external airlock. There appears to be significant activity directly in the center of the dome, which is where the suspected silo hole appears to be located.

- Long Rectangular Shelters