LRSO: The Nuclear Cruise Missile Mission

By Hans M. Kristensen

[Updated January 26, 2016] In an op-ed in the Washington Post, William Perry and Andy Weber last week called for canceling the Air Force’s new nuclear air-launched cruise missile.

The op-ed challenged what many see as an important component of the modernization of the U.S. nuclear triad of strategic weapons and a central element of U.S. nuclear strategy.

The recommendation to cancel the new cruise missile – known as the LRSO for Long-Range Standoff weapon – is all the more noteworthy because it comes from William Perry, known to some as “ALCM Bill,” who was secretary of defense from 1994 to 1997, and as President Carter’s undersecretary of defense for research and engineering in the late-1970s and early-1980s was in charge of developing the nuclear air-launched cruise missile the LRSO is intended to replace.

And his co-author, Andy Weber, was assistant secretary of defense for nuclear, chemical and biological defense programs from 2009 to 2014, during which he served as director of the Nuclear Weapons Council for five-plus years – the very time period the plans to build the LRSO emerged [note: the need to replace the ALCM was decided by DOD during the Bush administration in 2007].

Obviously, Perry and Weber are not impressed by the arguments presented by the Air Force, STRATCOM, the Office of the Secretary of Defense, the nuclear laboratories, defense hawks in Congress, and an army or former defense officials and contractors for why the United States should spend $15 billion to $20 billion on a new nuclear cruise missile.

Those arguments seem to have evolved very little since the 1970s. A survey of statements made by defense officials over the past few years for why the LRSO is needed reveals a concoction of justifications ranging from good-old warfighting scenarios of using nuclear weapons to blast holes in enemy air defenses to “the old missile is getting old, therefore we need a new one.”

LRSO: What Is It Good For?

When I wrote about the LRSO in 2013, the Air Force had only said a few things in public about why the weapon was needed. Since then, defense officials have piled on justifications in numerous public statements.

Those statements (see table below) describe an LRSO mission heavily influenced by nuclear warfighting scenarios. This involves deploying nuclear bombers “whenever and wherever we want” with large numbers of LRSOs onboard that “multiplies the number of penetrating targets each bomber presents to an adversary” and “imposes an extremely difficult, multi-azimuth air defense problem on our potential adversaries.” By providing “flexible and effective stand-off capabilities in the most challenging area denial environments” to “effectively conduct global strike operations” at will, the LRSO “maximally expands the accessible space of targets that can be held at risk,” including shooting “holes and gaps [in enemy air defenses] to allow a penetrating bomber to get in” to be able to “do direct attacks anywhere on the planet to hold any place at risk” whether it be in “limited or large scale” nuclear strike scenarios.

It seems clear from many of these statements that the LRSO is not merely a retaliatory capability but very much seen as an offensive nuclear strike weapon that is intended for use in the early phases of a conflict even before long-range ballistic missiles are used. In a briefing from 2014, Major General Garrett Harencak, until September this year the assistant chief of staff for Air Force strategic deterrence and nuclear integration, described a “nuclear use” phase before actual nuclear war during which bombers would use nuclear weapons against regional and near-peer adversaries (see image below).

This Air Force slide from 2014 shows “nuclear use” from bombers in a pre-“nuclear war” phase of a conflict. This apparently could include LRSO strikes against air-defense systems.

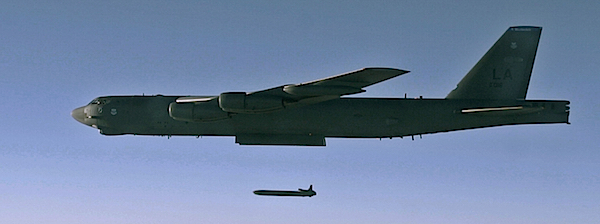

Although the LRSO is normally presented as a strategic weapon, the public descriptions by U.S. officials of limited regional scenarios sound very much like a tactical nuclear weapon to be used in a general military campaign alongside conventional weapons. “I can make holes and gaps” in air defenses, Air Force Global Strike commander Lieutenant General Stephen Wilson explained in 2014, “to allow a penetrating bomber to get in.” Indeed, an Air Force briefing slide from 2011 shows the LRSO launched from a next-generation bomber against air defenses to allow a next-generation penetrator launched from the same bomber to attack an underground target (see image below).

This Air Force briefing slide from 2011 shows the LRSO used against air-defense systems, similar to scenarios described by Air Force officials in 2014.

Use of bombers with LRSO in a pre-nuclear war phase is part of an increasing focus on regional nuclear strike scenarios. “We are increasing DOD’s focus on planning and posture to deter nuclear use in escalating regional conflicts,” according to Robert Scher, US Assistant Secretary of Defense for Strategy, Plans, and Capabilities. “The goal of strengthening regional deterrence cuts across both the strategic stability and extended deterrence and assurance missions to which our nuclear forces contribute.” The efforts include development of “enhanced planning to ensure options for the President in addressing the regional deterrence challenge.” (Emphasis added.)

The Pentagon appears to be using the Obama administration’s nuclear weapons employment policy to enhance strike options and plans in these regional scenarios. “The regional deterrence challenge may be the ‘least unlikely’ of the nuclear scenarios for which the United States must prepare,” Elaine Bunn, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear and Missile Defense Policy, told the Senate last year. And “continuing to enhance our planning and options for addressing it is at the heart of aligning U.S. nuclear employment policy and plans with today’s strategic environment.” (Emphasis added.)

Cruise Missile Dilemma: Nuclear Versus Conventional

The arguments used to justify the LRSO sound like the United States has little else with which to hold targets at risk. But bomber standoff and targeting capabilities today are vastly superior to those of the late-1970s and early-1980s when the ALCM was developed. Not only are non-nuclear cruise missiles proliferating in numbers and deliver platforms, the Air Force itself seems to prefer them over nuclear cruise missiles.

The Air Force plan to buy 1,000-1,100 LRSOs represents a significant increase of more than 40 percent over the current inventory of 575 ALCMs. Armed with the W80-4 warhead, the LRSO will not only be integrated onto the B-52H that currently carries the ALCM, but also onto the B-2A and the next-generation bomber (LRS-B).

Assuming the LRSO force will have the same number of warheads (approximately 528) as the current ALCM force, the roughly 180 missiles that would be lost in flight tests over a 30-year lifespan does not explain what the remaining 300-400 missiles would be used for.

Air Force Global Strike Command appears to hint that the extra missiles might be used for a conventional LRSO. “We fully intend to develop a conventional version of the LRSO as a future spiral to the nuclear variant.” Yet a lot of other conventional cruise missiles and standoff weapons are already in development – some even making their way onto smaller aircraft such as F-16 fighter-bombers – and Congress is unlikely to pay for yet another conventional air-launched cruise missile.

It is a curious dilemma for the Air Force: it needs the LRSO to help justify the long-range bomber program, but it prefers to spend its money on conventional standoff weapons that are much more flexible and – in contras to the LRSO – can actually be used. The trend is that new conventional standoff weapons are gradually pushing the nuclear cruise missiles off the bombers. To reduce the nuclear load-out under the New START Treaty and prioritize conventional weapons, the Air Force is currently converting stripping the B-52H of its excess capability to carry the ALCM internally in the bomb bay. a total of 44 sets of Common Strategic Rotary Launchers (CSRLs) are being modified to Conventional Rotary Launchers (CRLs). This will give the B-52H the capability to deliver the non-nuclear Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) and its 1,100-kilometer (648 miles) extended range variant JASSM-ER (AGM-158B), weapons that are more useful for deterrent missions than a nuclear cruise missile. Once completed in 2018, each remaining nuclear-capable B-52H will only be capable of carrying nuclear cruise missiles externally: 12 missiles under the wings compared with a total of 20 today.

The Air Force is stripping the B-52H of its capability to nuclear air-launched cruise missiles in its bomb bay. By 2018, each B-52H will only be able to carry 12 ALCMs, down from 20 today. Instead it the bomber will equipping it B-52Hs to carry new conventional cruise missiles in its bomb bay.

While the B-52H will lose the capability to carry nuclear cruise missiles internally, The JASSM in contrast will be integrated for both internal and external carriage. As a result, each B-52H will be equipped to carry up to 20 JASSM, of which as many as 16 can be JASSM-ER. Moreover, while only 46 B-52H will be nuclear-capable, all remaining 76 B-52Hs in the inventory will be back fitted for JASSM. An interim JASSM-ER capability is planned for 2017 – nearly a decade before the LRSO is scheduled to be deployed – providing essentially the same standoff capability (although with less range).

The B-2A Spirit stealth-bomber cannot currently carry ALCMs but the Air Force says but will be fitted to carry the LRSO internally in addition to the new B61-12 guided nuclear bomb. The B-2A, which is scheduled to fly until the 2050s, is also scheduled to be back-fitted with the JASSM-ER.

The next-generation long-range bomber (LRS-B) will also be equipped with the LRSO (probably 16 internally) in addition to the B61-12, and probably also the JASSM-ER. Once it begins to enter the force after 2025, the LRS-B will probably replace the B-52H in the nuclear mission on a one-for-one basis.

Approximately 5,000 JASSMs are planned, including more than 2,900 JASSM-ERs. Although the nuclear LRSO has a “significantly” greater range than the JASSM-ER (probably 2,500-3,000 kilometers), the conventional missile will still enable the bomber to attack from well beyond air-defense range against soft, medium, and very hard (not deeply buried) targets.

JASSM-ER has been integrated on the B-1B bomber that recently was incorporated into Air Force Global Strike Command alongside B-2A and B-52H bombers. After it is added to the B-52H and B-2A, the JASSM will also be added to F-15E and F-16 fighter-bombers and possibly also to some navy aircraft. Several European countries have already bought JASSM for their fighter-bombers (Poland and Finland).

Clearly, conventional standoff missiles rather than the LRSO appear to be the priority of the Air Force.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In their op-ed, Perry and Weber describe the justification that was used during the Cold War for developing the existing cruise missile, the ALCM (AGM-86B). “At that time, the United States needed the cruise missile to keep the aging B-52, which is quite vulnerable to enemy air defense systems, in the nuclear mission until the more effective B-2 replaced it. The B-52 could safely launch the long-range cruise missile far from Soviet air defenses. We needed large numbers of air-launched nuclear cruise missiles to be able to overwhelm Soviet air defenses and thus help offset NATO’s conventional-force inferiority in Europe,” they write.

The anti-air defense mission that justified development of a nuclear ALCM during the Cold War is no longer relevant. According to Perry and Weber, “such a posture no longer reflects the reality of today’s U.S. conventional military dominance.”

They are right. All U.S. bombers, as well as many fighter-bombers, are scheduled to be equipped with long-rang conventional cruise missiles that provide sufficient capability against the same air-defense targets that LRSO proponents argue require a standoff nuclear cruise missile on the next-generation bomber.

Canceling the LRSO would be an appropriate way to demonstrate implementation of the Obama administration’s nuclear weapons employment strategy from 2013 that directed the Pentagon to “undertake concrete steps toward reducing the role of nuclear weapons in our national security strategy” and “conduct deliberate planning for non-nuclear strike options to assess what objectives and effects could be achieved through integrated non-nuclear strike options.”

Instead, statements by defense officials reveal a worrisome level of warfighting thinking behind the LRSO mission that risks dragging U.S. nuclear planning back into Cold War thinking about the role of nuclear weapons. Instead of implementing the guidance and use advanced conventional weapons to “make holes and gaps” in air defenses, the LRSO mission appears to entertain ideas about using nuclear weapons against regional and near-peer adversaries in the name of extended deterrence and escalation control before actual nuclear war.

Although bombers armed with nuclear gravity bombs can be used to signal to adversaries in a crisis, loading the aircraft with long-range nuclear cruise missiles that can slip unseen under the radar in a surprise attack is inherently destabilizing. This dilemma is exacerbated by the large upload-capability of the bombers that are not normally on alert with nuclear weapons. Pentagon officials will normally warn that re-alerting nuclear weapons onto launchers in a crisis is dangerous, but in the case of LRSO they seem to relish the option to “provide a rapid and flexible hedge against changes in the strategic environment.”

Perry and Weber’s recommendation to cancel the unnecessary and dangerous LRSO is both wise and bold. The strategic situation has changed fundamentally, conventional capabilities can do most of the mission, and arguments for the LRSO seem to be a mixture of Cold War strategy and general nuclear doctrinal mumbo jumbo. Some people in the Obama administration will certainly listen (as will many that have already left). Others will argue that even if they wanted to cancel LRSO, they have little room to maneuver given a hostile Congress, Russia’s return as an official threat, and China’s military modernization and posturing in the South China Sea.

Moreover, the development of the LRSO and its W80-4 warhead is already well underway and rapidly approaching the point of no return. The decision to replace the ALCM with the LRSO was reaffirmed by the Obama administration’s 2010 Nuclear Posture Review, the Airborne Strategic Deterrence Capability Based Assessment, and the Initial Capability Document. The LRSO Analysis of Alternatives (AoA) study is already complete and has been approved by the Joint Requirements Oversight Council (JROC), and the Chief of Staff of the Air Force signed the Draft Capabilities Development Document in February 2014. LRSO was selected by the assistance secretary of the Air Force for acquisition (SAF/AQ) as a pilot program for “Bending the Cost Curve,” a new acquisition initiative to make weapons programs more affordable (although with a cost of $15 billion to $20 billion that curve seems to point pretty much straight up). The critical Milestone A decision is expected in early 2016, and program spending will ramp up in 2017 as full-scale development begins with $1.8 billion programmed through 2020.

Similarly, development of the W80-4 warhead for the LRSO is well underway with $1.9 billion programmed through 2020. Warhead development is in Phase 6.2 with first production unit scheduled for 2025.

If national security and rational defense planning – not institutional turf and inertia – determined the U.S. nuclear weapons modernization program, then the LRSO would be canceled. At least Perry and Weber had the guts to call for it.

This publication was made possible by a grant from the New Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.