While Advocating Nuclear Transparency Abroad, Biden Administration Limits It At Home

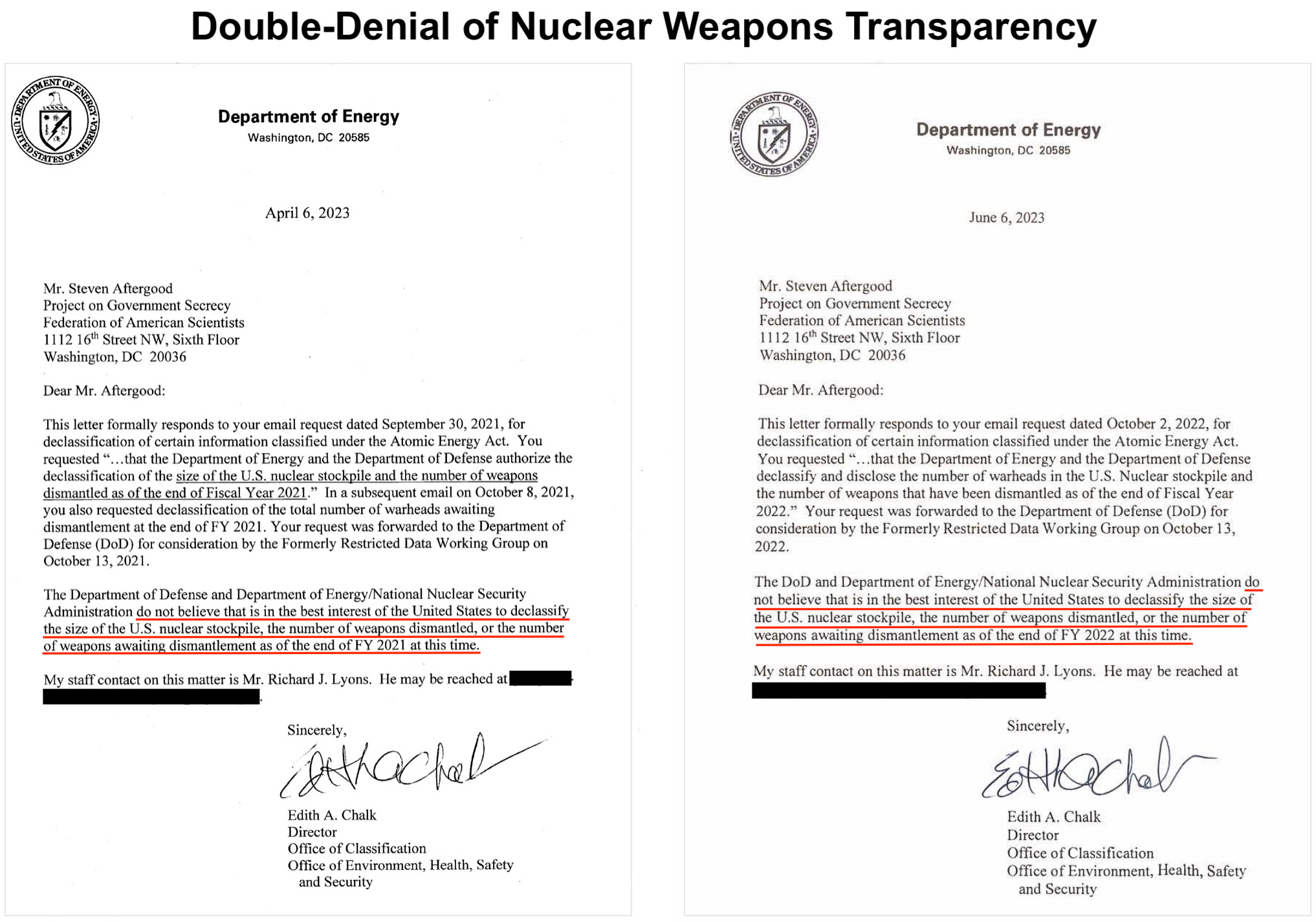

While US diplomats were busy advocating nuclear transparency abroad, the Department of Defense and Department of Energy rejected two requests from the Federation of American Scientists to declassify nuclear weapons stockpile and dismantlement numbers.

This week, US diplomats will join colleagues in Vienna from 189 other countries for the first session of the Preparatory Committee for the 2026 Review Conference of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

At the meeting, the US diplomats are expected to speak in favor of nuclear transparency and criticize some other nuclear-armed states for not being transparent enough about their nuclear arsenal. They are right in doing so because nuclear transparency is important for international security and democratic values.

Unfortunately, the diplomats’ efforts are undermined by other elements of the US administration that are reducing transparency of the US nuclear arsenal.

Earlier this spring, the Department of Defense and Department of Energy twice rejected requests from the Federation of American Scientists to declassify the number of nuclear weapons in the US stockpile and the number of nuclear weapons awaiting dismantlement. The requests (see copies above) were made by Stephen Aftergood who until 2021 directed the FAS project on government secrecy.

Contradicting Previous Policies

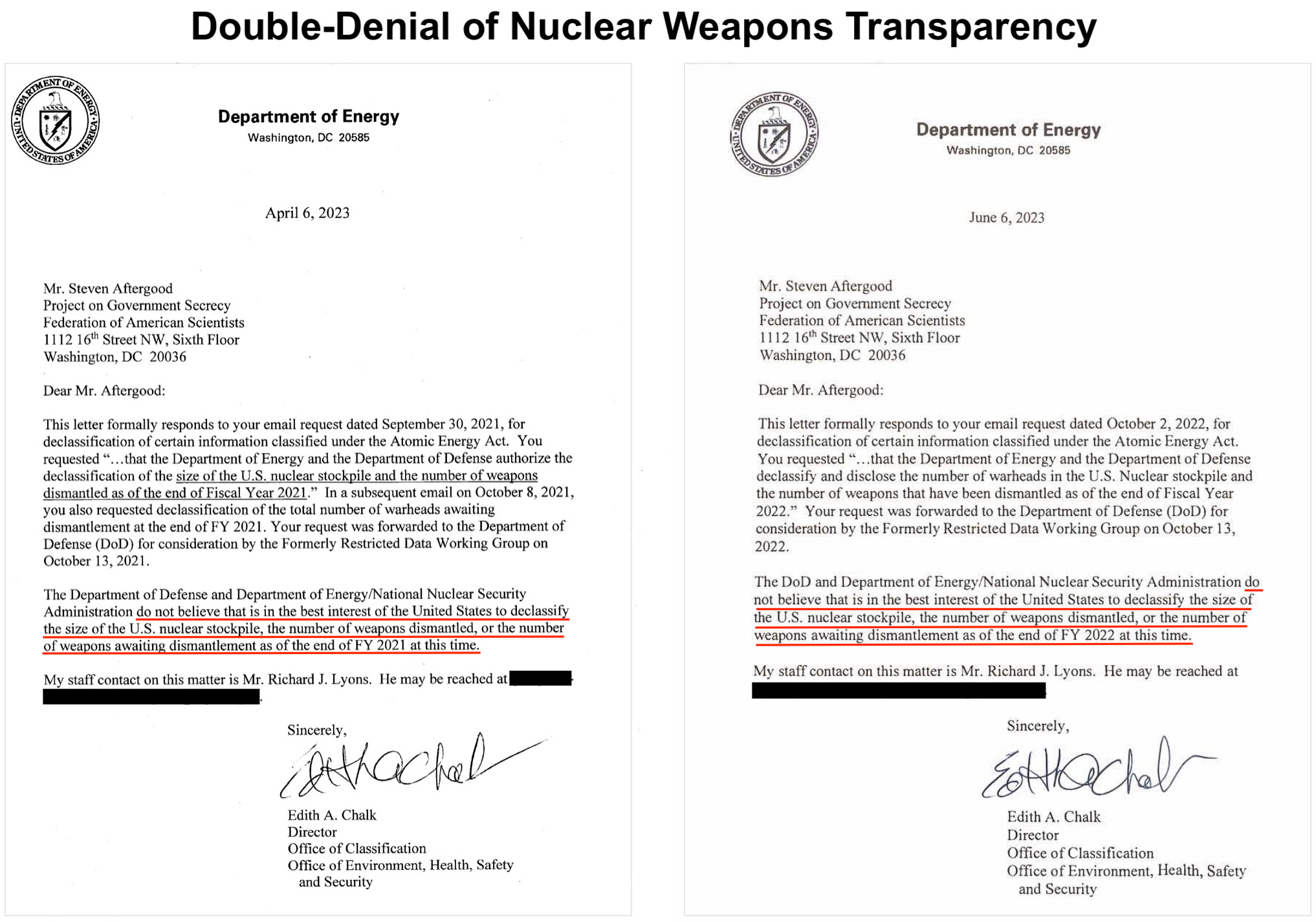

The rejections of FAS’ declassification requests are noteworthy because the US government in previous years repeatedly has declassified and released such information to the public. In 1994, the US Department of Energy declassified the stockpile size and other information between 1945 and 1994. In 2010, the Obama administration declassified the entire remaining history of US nuclear weapons stockpile as well as warheads dismantled since 1994. These disclosures continued in subsequent years and even expanded to include the number of weapons awaiting dismantlement.

When the Trump administration took office, it soon closed the door on transparency and kept it shut for three years. But after Joe Biden won the presidential election, his administration in October 2021 restored stockpile transparency by declassifying the number as of September 2020. An announcement on the National Nuclear Security Administration’s web site states:

“Increasing the transparency of states’ nuclear stockpiles is important to nonproliferation and disarmament efforts, including commitments under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and efforts to address all types of nuclear weapons, including deployed and nondeployed, and strategic and non-strategic.”

Then, in a curious decision in 2022, the Biden administration discontinued its own nuclear transparency policy. It was expected that Secretary of State Antony Blinken would use his speech to the NPT Review Conference in August 2022 to announce the September 2021 stockpile number. Instead, he mentioned a vague percentage reduction since 1967. The political rationale was probably a reaction to Russia’ invasion of Ukraine.

The history of size of the US nuclear weapons stockpile has been declassified and released to the public, except for the two latest years that the Biden administration is keeping secret. We estimate that the stockpile currently includes approximately 3,700 warheads.

Declining Transparency

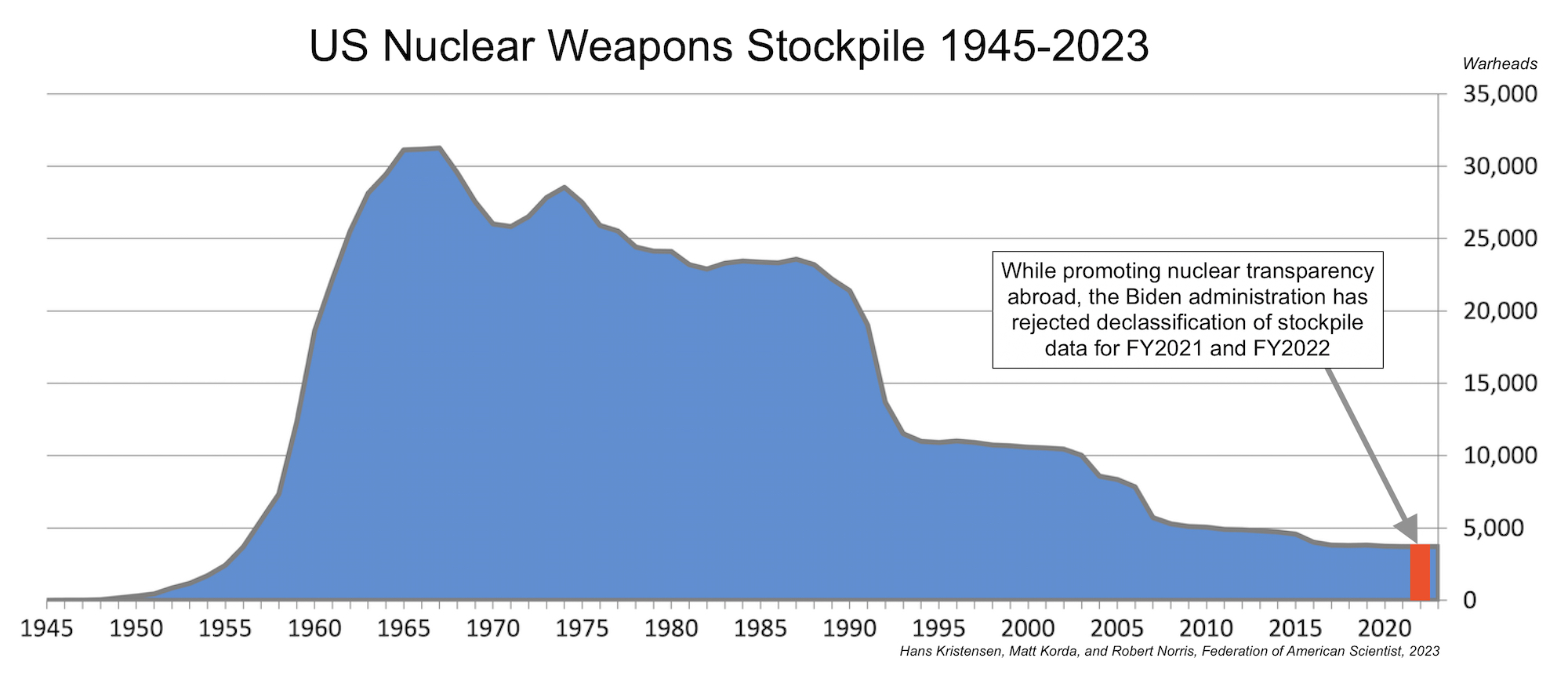

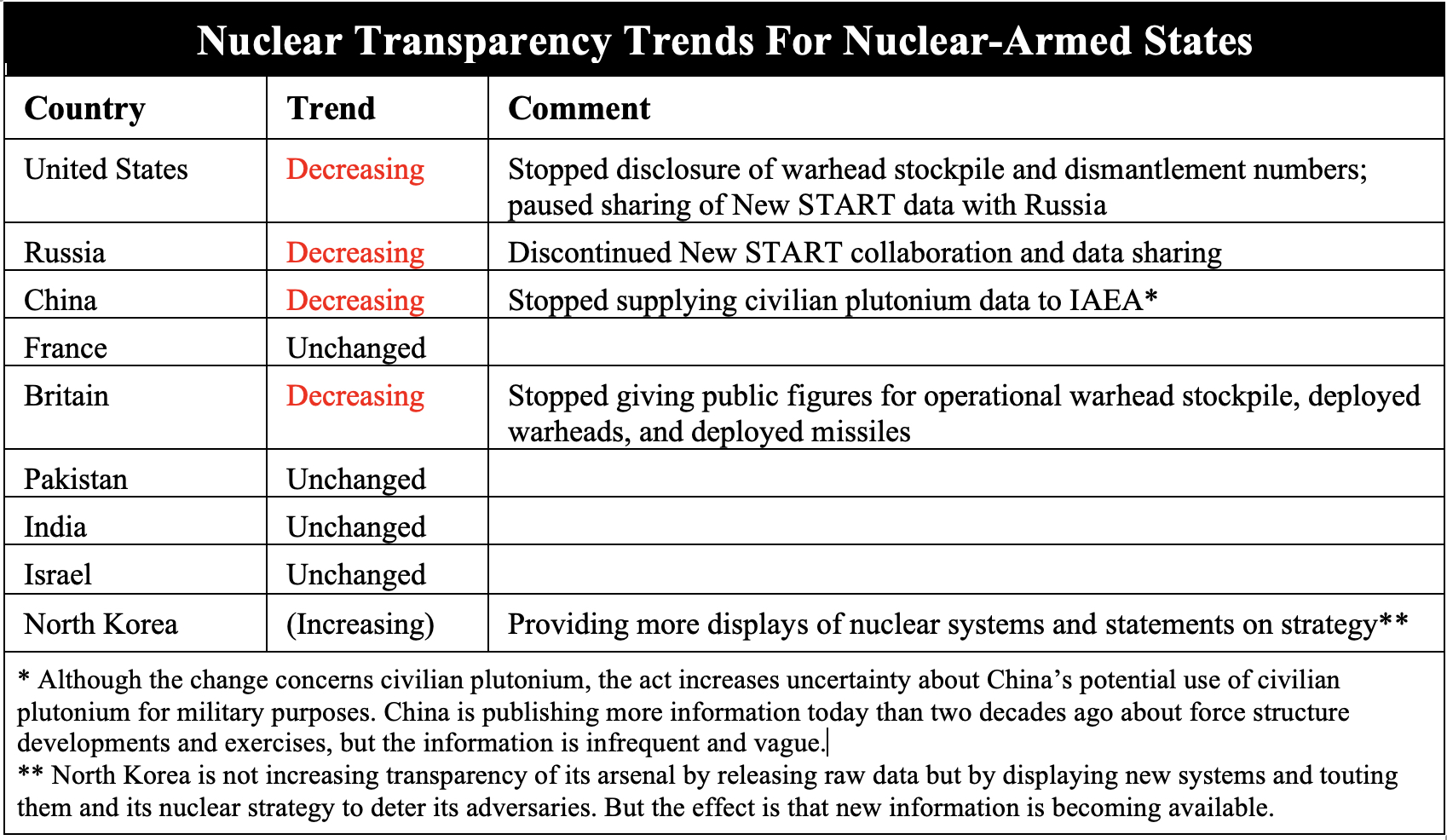

Compared to other nuclear-armed states, the United States is generally more transparent about its nuclear arsenal, strategy, and policies and has been so for a long time. So the Biden administration’s recent backpedaling on warhead stockpile transparency is unusual but only the latest in a series of steps by nuclear-armed states that have reduced transparency of nuclear arsenals and operations. The trend is that four of the world’s nine nuclear-armed states are decreasing nuclear transparency, including the United States and Britain who recently have taken steps to reduce information about their nuclear arsenals (see below).

The global trend is that the nuclear-armed states are decreasing the transparency of their nuclear arsenals, including countries that are otherwise saying transparency is important.

Ironically, North Korea is the only country that can be said in some sense to be increasing transparency, although not by providing raw data but by touting new weapons and strategy that as a result provide some additional information.

Lack of and decreasing nuclear transparency increase uncertainty and suspicion and can cause other countries to increase reliance on worst-case scenarios and even make mistakes about the intensions and plans of other nuclear-armed countries. Moreover, lack of and decreasing transparency leave the public debate open for exaggerations and false rumors.

Secrecy and defense hawks often argue that the United States should not release such information when its adversaries don’t. But nuclear transparency is not a gift to adversaries but a norm that nuclear-armed states should continue to promote and uphold for international and democratic reasons. And if countries say it is important, they should act accordingly.

Undercutting Diplomacy and Democracy

The rejections of FAS’ requests for declassification of nuclear warhead stockpile and dismantlement numbers have direct implications for US diplomacy because they contradict the nuclear transparency values that US diplomats are promoting overseas (including this week in Vienna), undercut US critique of Russian and Chinese nuclear secrecy, and make the United States look hypocritical.

In May this year, right between the two rejections of FAS’ declassification requests, the United States together with the other G7 countries at the Hiroshima Summit publicly emphasized the importance of nuclear transparency, including the size of their nuclear arsenals:

“We emphasize the importance of transparency with regard to nuclear weapons and welcome actions already taken by the United States, France and the United Kingdom to promote effective and responsible transparency measures through providing data on their nuclear forces and the objective size of their nuclear arsenal.”

Instead, and apparently as a direct consequence of the rejections of FAS’ declassification requests, when US Ambassador Bruce Turner spoke at the special nuclear transparency session in the Conference on Disarmament in June 6th (the very same day DOD and DOE rejected FAS’ declassification request for 2022 stockpile data), he was unable to present the delegates with updated information to demonstrate the US continued commitment to transparency but instead had to repeat old data from 2020.

In addition to undercutting US diplomatic efforts and credibility abroad, the declassification rejections also conflict with democratic values at home by depriving the US public official factual information it needs to be able to monitor how the government is managing the nuclear arsenal and warhead dismantlements – not to mention whether what the administration says abroad matches what it does at home. Factual information is essential to ensure voters can make informed decisions about government policy.

The extensive declassifications of stockpile and dismantlement numbers in previous years clearly demonstrate that such information is not secret, and that the government has no legitimate reason to withhold it from the public – other than it doesn’t want to “at this time.”

FAS believes the Biden administration’s decision to deny declassification of the nuclear weapons stockpile data for 2021 and 2022 is wrong, self-contradictory, and counterproductive and urges the White House to review the decision to restore US nuclear transparency so its diplomats can credibly promote this important norm abroad.

Additional information:

• Nuclear Notebook: United States Nuclear Weapons, 2023

• Increased Nuclear Secrecy Makes Us All Less Safe

• Status of World Nuclear Forces

This research was carried out with generous contributions from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the New-Land Foundation, Ploughshares Fund, the Prospect Hill Foundation, Longview Philanthropy, the Stewart R. Mott Foundation, the Future of Life Institute, Open Philanthropy, and individual donors.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.