The Navy plans to buy 12 SSBNs, more than it needs or can afford.

By Hans M. Kristensen

A new Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report – Options For Reducing the Deficit: 2014-2023 – proposes reducing the Navy’s fleet of Ohio-class ballistic missile submarines from the 14 boats today to 8 in 2020. That would save $11 billion in 2015-2023, and another $30 billion during the 2030s from buying four fewer Ohio replacement submarines.

The Navy has already drawn its line in the sand, insisting that the current force level of 14 SSBNs is needed until 2026 and that the next-generation SSBN class must include 12 boats.

But the Navy can’t afford that, nor can the United States, and the Obama administration’s new nuclear weapons employment guidance – issued with STRATCOM’s blessing – indicates that the United States could, in fact, reduce the SSBN fleet to eight boats. Here is how.

New START Treaty Force Level

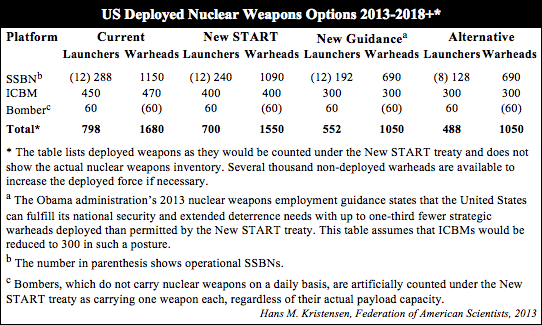

Under the New START treaty the United States plans to deploy 640 ballistic missiles loaded with 1490 warheads (1,550 warheads minus the 60 weapons artificially attributed to bombers that don’t carry nuclear weapons on a daily basis). Of that, the SSBN fleet will account for 240 missiles and 1090 warheads (see table below).

The analysis for the new guidance – formally known as Presidential Policy Decision 24 – determined that the United State could safely reduce its deployed nuclear weapons by up to one-third below the New START level. But even though the current posture therefore is bloated and significantly in excess of what’s needed to ensure the security of the United States and its allies and partners, the military plans to retain the New START force structure until Russia agrees to the reductions in a new treaty.

Yet Russia is already well below the New START treaty force level (-227 launchers and -150 warheads); the United States currently deploys 336 launchers more than Russia (!). Moreover, the Russian missile force is expected to decline even further from 428 to around 400 missiles by the early 2020s – even without a new treaty. Unlike U.S. missiles, however, the Russian missiles don’t have extra warhead spaces; they’re loaded to capacity to keep some degree of treaty parity with the United States.

Making The Cut

The table above includes two future force structure options: a New Guidance option based on the “up to one-third” cut in deployed strategic forces recommended by the Obama administration’s new nuclear weapons employment guidance; and an “Alternative” posture reduced to eight SSBNs as proposed by CBO.

Under the New Guidance posture, the SSBN fleet would carry 690 warheads, a reduction of 400 warheads below what’s planned under the New START treaty. The 192 SLBMs (assuming 16 per next-generation SSBN) would have nearly 850 extra warhead spaces (upload capacity), more than enough to increase the deployed warhead level back to today’s posture if necessary, and more than enough to hedge against a hypothetical failure of the entire ICBM force. In fact, the New Guidance posture would enable the SSBN force to carry almost all the warheads allowed under the New START treaty.

Under the Alternative posture, the SSBN fleet would also carry 690 warheads but there would be 64 fewer SLBMs. Those SLBMs would have “only” 334 extra warhead spaces, but still enough to hedge against a hypothetical failure of the ICBM force. In fact, the SLBMs would have enough capacity to carry almost the entire deployed warhead level recommended by the new employment guidance.

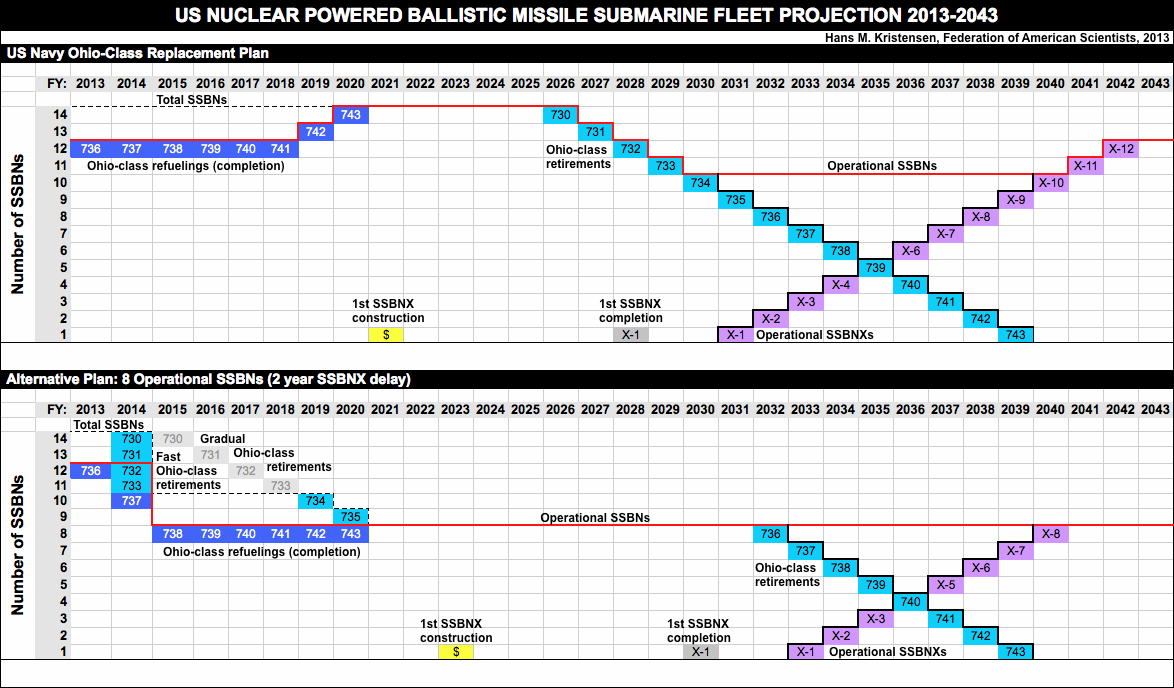

The Navy’s SSBN force structure plan will begin retiring the Ohio-class SSBNs in 2026 at a rate of one per year until the last boat is retired in 2039. The first next-generation ballistic missile submarine (currently known as SSBNX) is scheduled to begin construction in 2021, be completed in 2028, and sail on its first deterrent patrol in 2031. Additional SSBNXs will be added at a rate of one boat per year until the fleet reaches 12 by 2042 (see figure below).

The Navy’s schedule creates three fluctuations in the SSBN fleet. The first occurs in 2019-2020 where the number of operational SSBNs will increase from 12 to 14 as a result of the two newest boats (USS Wyoming (SSBN-742) and USS Louisiana (SSBN-743)) completing their mid-life reactor refueling overhauls. That is in excess of national security needs so at that time the Navy will probably retire the two oldest boats (USS Henry M. Jackson (SSBN-730) and USS Alabama (SSBN-731)) eight years early to keep the fleet at 12 operational SSBNs (this doesn’t show in the Navy’s plan).

The second fluctuation in the Navy’s schedule occurs in 2027-2030 when the number of operational SSBNs will drop to 10 as a result of the retirement of the first four Ohio-class SSBNs and the decision in 2012 to delay the first SSBNX by two years. As it turns out, that doesn’t matter because no more than 10 SSBNs are normally deployed anyway.

The third fluctuation in the Navy’s schedule occurs in 2041-2042 when the number of operational SSBNXs increases from 10 to 12 as the last two boats join the fleet. This is an odd development because there obviously is no reason to increase the fleet to 12 SSBNXs in the 2040s if the Navy has been doing just fine with 10 boats in the 2030s. This also suggests that the fleet could in fact be reduced to 12 boats today of which 10 would be operational. To do that the Navy could retire two SSBNs immediately and two more in 2019-2020 when the last refueling overhauls have are completed.

To reduce the SSBN fleet to eight boats as proposed by CBO, the Navy would retire the six oldest Ohio-class SSBNs at a rate of one per year in 2015-2020. At that point the last Ohio-class reactor refueling will have been completed, making all remaining SSBNs operationally available. A quicker schedule would be to retire four SSBNs in 2014 and the next two in 2019-2020. That would bring the fleet to eight operational boats immediately instead of over seven years and allow procurement of the first SSBNX to be delayed another two years (see figure above).

Reducing to eight SSBNs would obviously necessitate changes in the operations of the SSBN force. The Navy’s 12 operational SSBNs conduct 28 deterrent patrols per year, or an average of 2.3 patrols per submarine. The annual number of patrols has decline significantly over the past decade, indicating that the Navy is operating more SSBNs than it needs. Each patrol lasts on average 70 days and occasionally over 100 days. To retain the current patrol level with only eight SSBNs, each boat would have to conduct 3.5 patrols per year. Between 1988 and 2005, each SSBN did conduct that many patrols per year, so it is technically possible.

Moreover, of the 10 or so SSBNs that are at sea at any given time, about half (4-5) are thought to be on “hard alert” in pre-designated patrol areas, within required range of their targets, and ready to launch their missiles 15 minutes after receiving a launch order. A fleet of eight operational SSBNs could probably maintain six boats at sea at any given time, of which perhaps 3-4 boats could be on alert.

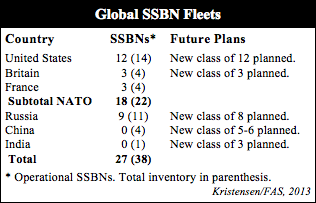

Finally, reducing the SSBN fleet to eight boats seems reasonable because no other country currently plans to operate more than eight SSBNs (see table). The United States today operates more SSBNs than any other country. And NATO’s three nuclear weapon states currently operate a total of 22 SSBNs, twice as many as Russia. China and India are also building SSBNs but they’re far less capable and not yet operational.

Finally, reducing the SSBN fleet to eight boats seems reasonable because no other country currently plans to operate more than eight SSBNs (see table). The United States today operates more SSBNs than any other country. And NATO’s three nuclear weapon states currently operate a total of 22 SSBNs, twice as many as Russia. China and India are also building SSBNs but they’re far less capable and not yet operational.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The Navy could and should reduce its SSBN fleet from 14 to eight boats as proposed by CBO. Doing so would shed excess capacity, help prepare the nuclear force level recommended by the new nuclear weapons employment policy, better match the force levels of other countries, and save billions of dollars. There are several reasons why this is possible:

First, the decision to go to 10 operational SSBNs in the 2030s suggests that the Navy is currently operating too many SSBNs and could immediately retire the two oldest Ohio-class SSBNs.

Second, the decision to build a new SSBN fleet with 144 fewer SLBM launch tubes than the current SSBN fleet is a blatant admission that the current force is significantly in excess of national security needs.

Third, the acknowledgement in November 2011 by former STRATCOM commander Gen. Robert Kehler that the reduction of 144 missile tubes “did not assume any specific changes to targeting or employment guidance” suggests there’s a significant over-capacity in the current SSBN fleet.

Fourth, it is highly unlikely that presidential nuclear guidance three decades from now – when the planned 12-boat SSBNX fleet becomes operational – will not have further reduced the nuclear arsenal and operational requirement significantly.

Fifth, reducing the SSBN fleet now would allow significant additional cost savings: $11 billion in 2015-2023 (and $30 billion more in the 2030s) from reduced ship building according to CBO; completing the W76-1 production earlier with 500 fewer warheads; $7 billion from reducing production of the life-extended Trident missile (D5LE) by 112 missiles; operational savings from retiring six Ohio-class SSBNs early; and by reducing the warhead production capacity requirement for the expensive Uranium Production Facility and Chemistry and Metallurgy Research facilities.

Sixth, reducing the SSBN fleet would help reduce the growing disparity between U.S. and Russian strategic missiles. This destabilizing trend keeps Russia in a worst-case planning mindset suspicious of U.S. intensions, drives large warhead loadings on each Russian missile, and wastes billions of dollars and rubles on maintaining larger-than-needed strategic nuclear force postures.

Change is always hard, but a reduction of the SSBN fleet would be a win for all.

This publication was made possible by grants from the New-Land Foundation and Ploughshares Fund. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the author.

The last remaining agreement limiting U.S. and Russian nuclear weapons has now expired. For the first time since 1972, there is no treaty-bound cap on strategic nuclear weapons.

The Pentagon’s new report provides additional context and useful perspectives on events in China that took place over the past year.

Successful NC3 modernization must do more than update hardware and software: it must integrate emerging technologies in ways that enhance resilience, ensure meaningful human control, and preserve strategic stability.

The FY2026 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) paints a picture of a Congress that is working to both protect and accelerate nuclear modernization programs while simultaneously lacking trust in the Pentagon and the Department of Energy to execute them.