What Works in Boston, Won’t Necessarily Work in Birmingham: 4 Pragmatic Principles for Building Commercialization Capacity in Innovation Ecosystems

Just like crop tops, flannel, and some truly unfortunate JNCO jeans that one of these authors wore in junior high, the trends of the 90’s are upon us again. In the innovation world, this means an outsized focus on tech-based economic development, the hottest new idea in economic development, circa 1995. This takes us back in time to fifteen years after the passage of the Bayh Dole Act, the federal legislation that granted ownership of federally funded research to universities. It was a time when the economy was expanding, dot-com growth was a boom, not a bubble, and we spent more time watching Saved by the Bell than thinking about economic impact.

After the creation of tech transfer offices across the country and the benefit of time, universities were just starting to understand how much the changes wrought by Bayh-Dole would impact them (or not). A raft of optimistic investments in venture development organizations and state public-private partnerships swept the country, some of which (like Ben Franklin Technology Partners and BioSTL) are still with us today, and some of which (like the Kansas Technology Enterprise Center) have flamed out in spectacular fashion. All of a sudden, research seemed like a process to be harnessed for economic impact. Out of this era came the focus on “technology commercialization” that has captured the economic development imagination to this day.

Commercialization, in the context of this piece, describes the process through which universities (or national labs) and the private sector collaborate to bring to the market technologies that were developed using federal funding. Unlike sponsored research and development, in which industry engages with universities from the beginning to fund and set a research agenda, commercialization brings in the private sector after the technology has been conceptualized. Successful commercialization efforts have now grown across the country, and we believe they can be described by four practical principles:

- Principle 1: A strong research enterprise is a necessary precondition to building a strong commercialization pipeline.

- Principle 2: Commercialization via established businesses creates different economic impacts than commercialization via startups; each pathway requires fundamentally different support.

- Principle 3: Local context matters; what works in Boston won’t necessarily work in Birmingham.

- Principle 4: Successful commercialization pipelines include interventions at the individual, institutional, and ecosystem level.

Principle 1: A strong research enterprise is a necessary precondition to building a strong commercialization pipeline.

The first condition necessary to developing a commercialization pipeline is a reasonably advanced research enterprise. While not every region in the U.S. has access to a top-tier research university, there are pockets of excellent research at most major U.S. R1 and R2 institutions. However, because there is natural attrition at each stage of the commercialization process (much like the startup process) a critical mass of novel, leading, and relevant research activity must exist in a given University. If that bar is assumed to be the ability to attract $10 million in research funding (the equivalent of winning 20-25 SBIR Phase 1 grants annually), that limits the number of schools that can run a fruitful commercialization pipeline to approximately 350 institutions, based on data from the NSF NCSES. A metro area should have at least one research institution that meets this bar in order to secure federal funding for the development of lab-to-market programs, though given the co-location of many universities, it is possible for some metro areas to have several such research institutions or none at all.

Principle 2: Commercialization via established businesses creates different economic impacts than commercialization via startups; each pathway requires fundamentally different support.

When talking about commercialization, it is also important to differentiate between whether a new technology is brought to market by a large, incumbent company or start-up. The first half of the commercialization process is the same for both: technology is transferred out of universities, national labs, and other research institutions through the process of registering, patenting, and licensing new intellectual property (IP). Once licensed, though, the commercialization pathway branches into two.

With an incumbent company, whether or not it successfully brings new technology to the market is largely dependent on the company’s internal goals and willingness to commit resources to commercializing that IP. Often, incumbent companies will license patents as a defensive strategy in order to prevent competition with their existing product lines. As a result, license of a technology by an incumbent company cannot be assumed to represent a guarantee of commercial use or value creation.

The alternative pathway is for universities to license their IP to start-ups, which may be spun out of university labs. Though success is not guaranteed, licensing to these new companies is where new programs and better policies can actually make an impact. Start-ups are dependent upon successful commercialization and require a lot of support to do so. Policies and programs that help meet their core needs can play a significant role in whether or not a start-up succeeds. These core needs include independent space for demonstrating and scaling their product, capital for that work and commercialization activities (e.g. scouting customers and conducting sales), and support through mentorship programs, accelerators, and in-kind help navigating regulatory processes (especially in deep tech fields).

Principle 3: Local context matters; what works in Boston won’t necessarily work in Birmingham.

Unfortunately, many universities approach their tech transfer programs with the goal of licensing their technology to large companies almost exclusively. This arises because university technology transfer offices (TTOs) are often understaffed, and it is easier to license multiple technologies to the same large company under an established partnership than to scout new buyers and negotiate new contracts for each patent. The Bayh-Dole Act, which established the current tech transfer system, was never intended to subsidize the R&D expenditures of our nation’s largest and most profitable companies, nor was it intended to allow incumbents to weaponize IP to repel new market entrants. Yet, that is how it is being used today in practical application.

Universities are not necessarily to blame for the lack of resources, though. Universities spend on average 0.6% of their research expenditures on their tech transfer programs. However, there is a large difference in research expenditures between top universities that can attract over a billion in research funding and the average research university, and thus a large difference in the staffing and support of TTOs. State government funding for the majority of public research universities have been declining since 2008, though there has been a slight upswing since the pandemic, while R&D funding at top universities continues to increase. Only a small minority of TTOs bring in enough income from licensing in order to be self-sustaining, often from a single “blockbuster” patent, while the majority operate at a loss to the institution.

To successfully develop innovation capacity in ecosystems around the country through increased commercialization activity, one must recognize that communities have dramatically different levels of resources dedicated to these activities, and thus, “best practices” developed at leading universities are seldom replicable in smaller markets.

Principle 4: Successful commercialization pipelines include interventions at the individual, institutional, and ecosystem level.

As we’ve discussed at length in our FAS “systems-thinking” blog series, which includes a post on innovation ecosystems, a systems lens is fundamental to how we see the world. Thinking in terms of systems helps us understand the structural changes that are needed to change the conditions that we see playing out around us every day. When thinking about the structure of commercialization processes, we believe that intervention at various structural levels of a system is necessary to create progres on challenges that seem insurmountable at first—such as changing the cultural expectations of “success” that are so influential in the academic systems. Below we have identified some good practices and programs for supporting commercialization at the individual, institutional, and ecosystem level, with an emphasis on pathways to start-ups and entrepreneurship.

Practices and Programs Targeted at Individuals

University tech transfer programs are often reliant on individuals taking the initiative to register new IP with their TTOs. This requires individuals to be both interested enough in commercialization and knowledgeable enough about the commercialization potential of their research to pursue registration. Universities can encourage faculty to be proactive in pursuing commercialization through recognizing entrepreneurial activities in their hiring, promotion and tenure guidelines and encouraging faculty to use their sabbaticals to pursue entrepreneurial activities. An analog to the latter at national laboratories are Entrepreneurial Leave Programs that allow staff scientists to take a leave of up to three years to start or join a start-up before returning to their position at the national lab.

Faculty and staff scientists are not the only source of IP though; graduate students and postdoctoral researchers produce much of the actual research behind new intellectual property. Whether or not these early-career researchers pursue commercialization activities is correlated with whether they have had research advisors who were engaged in commercialization. For this reason, in 2007, the National Research Foundation of Singapore established a joint research center with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) such that by working with entrepreneurial MIT faculty members, researchers at major Singaporean universities would also develop a culture of entrepreneurship. Most universities likely can’t establish programs of this scale, but some type of mentorship program for early-career scientists pre-IP generation can help create a broader culture of translational research and technology transfer. Universities should also actively support graduate students and postdoctoral researchers in putting forward IP to their TTO. Some universities have even gone so far as to create funds to buy back the time of graduate students and postdocs from their labs and direct that time to entrepreneurial activities, such as participating in an iCorps program or conducting primary market research.

Some universities have even gone so far as to create funds to buy back the time of graduate students and postdocs from their labs and direct that time to entrepreneurial activities, such as participating in an iCorps program or conducting primary market research.

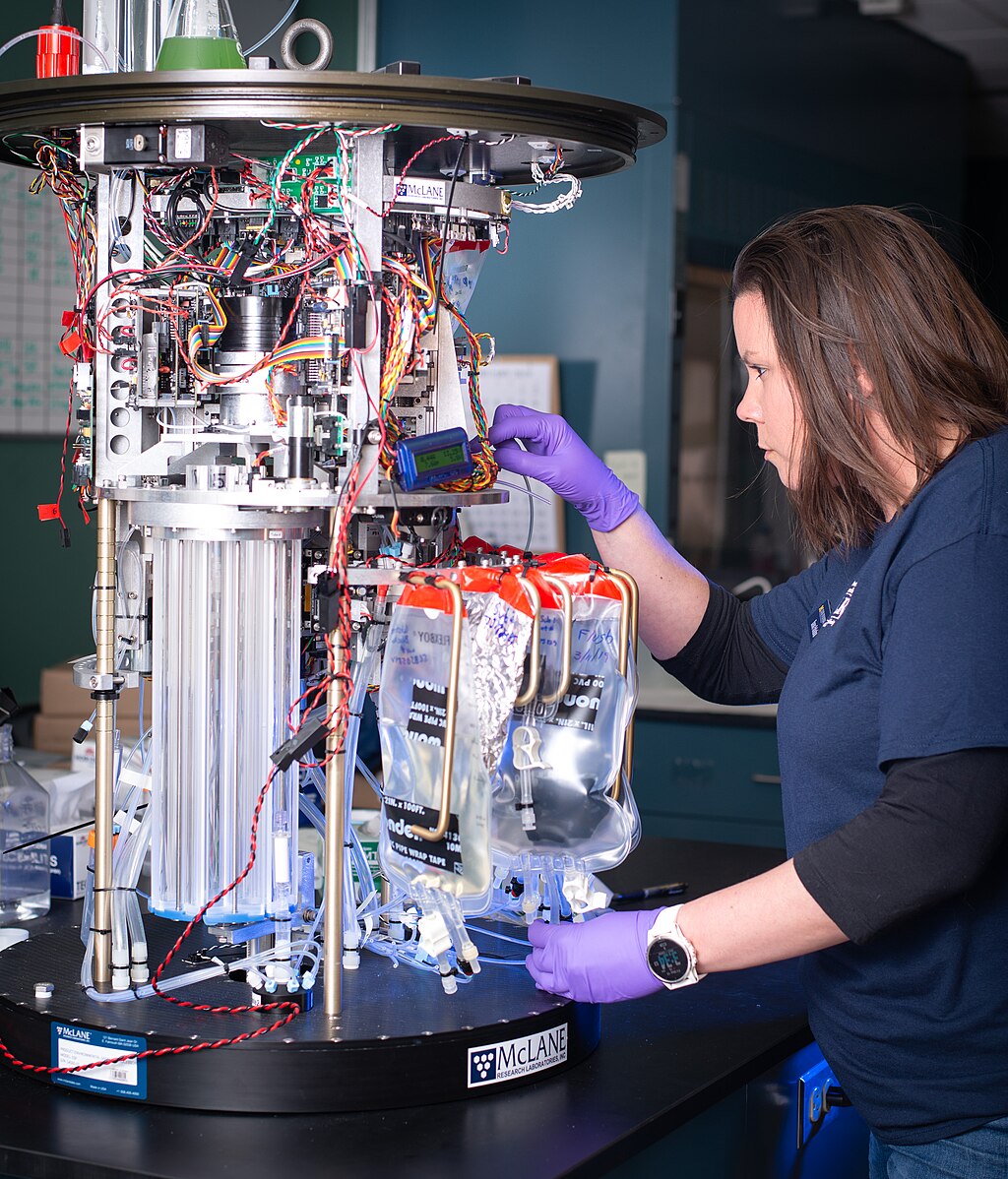

Once IP has been generated and licensed, many universities offer mentorship programs for new entrepreneurs, such as MIT’s Venture Mentorship Services. Outside of universities, incubators and accelerators provide mentorship along with funding and/or co-working spaces for start-ups to grow their operation. Hardware-focused start-ups especially benefit from having a local incubator or accelerator, since hard-tech start-ups attract significantly less venture capital funding and support than digital technology start-ups, but require larger capital expenditures as they scale. Shared research facilities and testbeds are also crucial for providing hard-tech start-ups with the lab space and equipment to refine and scale their technologies.

For internationally-born entrepreneurs, an additional consideration is visa sponsorship. International graduate students and postdocs that launch start-ups need visa sponsors in order to stay in the United States as they transition out of academia. Universities that participate in the Global Entrepreneur in Residence program help provide H-1B visas for international entrepreneurs to work on their start-ups in affiliation with universities. The university benefits in return by attracting start-ups to their local community that then generate economic opportunities and help create an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Practices and Programs Targeted at Institutions

As mentioned in the beginning, one of the biggest challenges for university tech transfer programs is understaffed TTOs and small patent budgets. On average, TTOs have only four people on staff, who can each file a handful of patents a year, and budgets for the legal fees on even fewer patents. Fully staffing TTOs can help universities ensure that new IP doesn’t slip through the cracks due to a lack of capacity for patenting or licensing activities. Developing standard term sheets for licensing agreements can also reduce administrative burden and make it easier for TTOs to establish new partnerships.

Instead of TTOs, some universities have established affiliated technology intermediaries, which are organizations that take on the business aspects of technology commercialization. For example, the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation (WARF) was launched as an independent, nonprofit corporation to manage the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s vitamin D patents and invest the resulting revenue into future research at the university. Since its inception 90 years ago, WARF has provided $2.3 billion in grants to the university and helped establish 60 start-up companies.

In general, universities need to be more consistent about collecting and reporting key performance indicators for TTOs outside of the AUTM framework, such as the number of unlicensed patents and the number of products brought to the market using licensed technologies. In particular, universities should disaggregate metrics for licensing and partnerships between companies less than five years old and those greater than five years old so that stakeholders can see whether there is a difference in commercialization outcomes between incumbent and start-up licensees.

Practices and Programs Targeted at Innovation Ecosystems

Innovation ecosystems are made up of researchers, entrepreneurs, corporations, the workforce, government, and sources of capital. Geographic proximity through co-locating universities, corporations, start-ups, government research facilities, and other stakeholder institutions can help foster both formal and informal collaboration and result in significant technology-driven economic growth and benefits. Co-location may arise organically over time or result from the intentional development of research parks, such as the NASA Research Park. When done properly, the work of each stakeholder should advance a shared vision. This can create a virtuous cycle that attracts additional talent and stakeholders to the shared vision and can integrate with more traditional attraction and retention efforts. One such example is the co-location of the National Bio- and Agro-Defense Facility in Manhattan, KS, near the campus of Kansas State University. After securing that national lab, the university made investments in additional BSL-2, 3 and 3+ research facilities including the Biosecurity Research Institute and its Business Development Module. The construction and maintenance of those facilities required the creation of new workforce development programs to train HVAC technicians that manage the independent air handling capabilities of the labs and train biomanufacturing workers, which was then one of the selling points for the successful campaign for the relocation of corporation Scorpius Biologics to the region. At best, all elements of an innovation ecosystem are fueled by a research focus and the commercialization activity that it provides.

For regions that find themselves short of the talent they need, soft-landing initiatives can help attract domestic and international entrepreneurs, start-ups, and early-stage firms to establish part of their business in a new region or to relocate entirely. This process can be daunting for early-stage companies, so soft-landing initiatives aim to provide the support and resources that will help an early-stage company acclimatize and thrive in a new place. These initiatives help to expand the reach of a community, create a talent base, and foster the conditions for future economic growth and benefits.

Alongside the creation of innovation ecosystems should be the establishment of “scale-up ecosystems” focused on developing and scaling new manufacturing processes necessary to mass produce the new technologies being developed. This is often an overlooked aspect of technology development in the United States, and supply chain shocks over the past few years have shone a light on the need to develop more local manufacturing supply chains. Fostering the growth of manufacturing alongside technology innovation can (1) reduce the time cycling between product and process development in the commercialization process, (2) capture the “learning by doing” benefits from scaling the production of new technologies, and (3) replenish the number of middle-income jobs that have been outsourced over the past few decades.

Any way you slice it, commercialization capacity is one clear and critical input to a successful innovation ecosystem. However, it’s not the only element that’s important. A strong startup commercialization effort, standing alone, without the corporate, workforce, or government support that it needs to build a vibrant ecosystem around its entrepreneurs, might wane with time or simply be very successful at shipping spinouts off to a coastal hotspot. Building a commercialization pipeline is not, nor has it ever been, a one-size-fits-all solution for ecosystem building.

It may even be something we’ve over-indexed on, given the widespread adoption of tech-based economic development strategies. One significant reason for this is the fact that entrepreneurship via commercialization is most open to those who already have access to a great deal of privilege–who have attained, or are on the path to, graduate degrees in STEM fields critical to our national competitiveness. If you’ve already earned a Ph.D. in machine learning, chances are your future is looking pretty bright—with or without entrepreneurial opportunity involved. To truly reap the economic benefits of commercialization activity (and the startups it creates), we need to aggressively implement programs, training, and models that change the demographics of who gets to commercialize technology, not just how they do it. To shape this, we’ll need to change the conditions for success for early-career researchers and reconsider the established model of how we mentor and train the next generation of scientists and engineers–you’ll hear more from us on these topics in future posts!

“Permitting reform” may not sound sexy, but it is critical if the federal government wants to meet its clean energy and climate goals.

Tech Hub designation, from the bipartisan CHIPS & Science Act, will play a role in tomorrow’s economic strength and resiliency, says the Federation. Washington, DC – October 23, 2023 – The Federation of American Scientists (FAS) today announced their congratulations to the 31 communities across the United States designated as Tech Hubs by the Biden-Harris […]